Deep Learning Models for Autism Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Comparison of Architectures, Performance, and Clinical Applicability

This article provides a systematic analysis of deep learning (DL) approaches for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis, addressing the critical need for objective and early screening tools.

Deep Learning Models for Autism Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Comparison of Architectures, Performance, and Clinical Applicability

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of deep learning (DL) approaches for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis, addressing the critical need for objective and early screening tools. Targeting researchers and biomedical professionals, we explore foundational concepts, data modalities—including fMRI, facial images, and eye-tracking—and key DL architectures like CNNs, LSTMs, and hybrid models. The review details methodological implementations, troubleshooting for data and model optimization, and a rigorous comparative validation of reported accuracies, which range from 70% to over 99% across studies. We synthesize empirical evidence to guide model selection and discuss the translational pathway for integrating these computational tools into clinical and pharmaceutical development workflows.

The Foundation of AI in Autism Diagnosis: Core Concepts and Data Modalities

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis represents a significant clinical challenge, relying on the identification of behavioral phenotypes defined by standardized criteria such as persistent deficits in social communication and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior [1]. Traditional "gold standard" diagnostic practices involve a best-estimate clinical consensus (BEC) that integrates detailed developmental history, multidisciplinary professional opinions, results of standardized assessments like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), and direct observation [1] [2]. However, this paradigm is increasingly strained by issues of subjectivity, resource intensity, and accessibility, prompting a critical examination of its limitations within the broader context of research into deep learning (DL) and artificial intelligence (AI) models for autism diagnosis [3] [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison between traditional assessment methodologies and emerging computational approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Methodological Comparison: Traditional vs. AI-Enhanced Paradigms

Traditional Diagnostic Framework: The traditional pathway is clinician-centric, requiring specialized training and manual administration of tools. Diagnosis is based on criteria from the DSM-5 or ICD-11 and should be informed by a range of sources alongside clinical judgment, not by any single instrument [1]. Key tools include the ADOS-2 for direct observation and the ADI-R for caregiver interview. This process is time-consuming, costly, and its accuracy is heavily dependent on clinician experience [3] [2]. Furthermore, studies show suboptimal agreement between community diagnoses and consensus diagnoses using standardized instruments, with one study finding 23% of community-diagnosed participants classified as non-spectrum upon expert reevaluation [2]. The framework also exhibits systemic biases, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses in females and minoritized groups due to phenotypic differences and clinician bias [5].

AI/Deep Learning Enhanced Framework: AI approaches aim to augment or automate aspects of the diagnostic process using data-driven pattern recognition. This includes analyzing structured questionnaire data [6] [7], facial images [8], or functional MRI (fMRI) data [8]. Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks, such as those integrating SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), are developed to provide transparent reasoning behind model predictions, bridging the gap between high accuracy and clinical interpretability [6]. Generative AI (GenAI) is also being explored for screening, assessment, and caregiver support [4]. These models promise scalability, consistency, and the ability to handle high-dimensional data, but require large datasets and rigorous clinical validation [4] [9].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Diagnostic Accuracy of Traditional vs. AI-Based Methods

| Method Category | Specific Tool/Model | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Reported Accuracy | AUC-ROC | Data Source/Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Screening | M-CHAT-R/F (Level 1 Screener) | >90% | >90% | - | - | [10] |

| Traditional Diagnostic | ADOS + ADI-R + Clinical Consensus | Very High (Gold Standard) | Very High (Gold Standard) | - | - | [1] [2] |

| Deep Learning (Meta-Analysis) | Various DL Models (fMRI/Facial) | 0.95 (0.88–0.98) | 0.93 (0.85–0.97) | - | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | [8] |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | TabPFNMix + SHAP Framework | 92.7% (Recall) | - | 91.5% | 94.3% | [6] |

| Ensemble ML Model | RF+ET+CB Stacked with ANN | - | - | 96.96% – 99.89%* | - | [7] |

| Traditional Limitation | Community Dx vs. Expert Consensus | - | - | 77% Agreement | - | [2] |

*Accuracy range across datasets for toddlers, children, adolescents, and adults [7].

Table 2: Key Limitations and Comparative Advantages

| Aspect | Traditional Assessment Methods | AI/Deep Learning Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Core Strength | Expert clinical judgement, holistic patient history, gold-standard reliability when ideally administered. | High-throughput pattern recognition, scalability, data-driven objectivity, potential for early biomarker detection. |

| Primary Limitation | Subjectivity, resource-intensive, lengthy wait times, access disparities, susceptibility to diagnostic bias [3] [2] [5]. | "Black-box" problem (mitigated by XAI), dependence on large/biased datasets, lack of comprehensive clinical validation, hardware demands [6] [9]. |

| Interpretability | High (clinical reasoning). | Low for standard DL; Moderate to High with XAI integration (e.g., SHAP) [6] [9]. |

| Data Dependency | Relies on qualitative observation and interview data. | Requires large, curated quantitative datasets (imaging, behavioral scores) [8] [9]. |

| Scalability & Access | Poor; limited by specialist availability. | Potentially high; can be deployed via digital platforms [4]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Traditional Best-Estimate Clinical Consensus (BEC) Diagnosis

- Objective: To establish a gold-standard ASD diagnosis for research or complex clinical cases.

- Materials: ADOS-2 kit, ADI-R protocol, cognitive/adaptive behavior scales (e.g., DAS-II, VABS-II), detailed developmental history questionnaire.

- Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Enroll participants based on prior community concern or diagnosis.

- Multimodal Assessment: Conduct in-person sessions comprising: a. ADI-R Administration: A trained clinician conducts a semi-structured interview with the caregiver. b. ADOS-2 Administration: A different trained clinician administers the appropriate module via direct, structured social presses. c. Cognitive/Adaptive Testing: A psychologist performs standardized assessments. d. Medical & Developmental History: A physician conducts a review and physical exam.

- Independent Scoring: Clinicians score the ADOS-2 and ADI-R according to standardized algorithms.

- Clinical Consensus Meeting: At least two expert clinicians review all data (scores, historical reports, behavioral observations) against DSM-5/ICD-11 criteria.

- Diagnostic Outcome: A consensus diagnosis (ASD, Non-spectrum) is reached through discussion, integrating all information sources [2].

Protocol 2: Development and Validation of an Explainable AI (XAI) Diagnostic Model

- Objective: To train and validate a machine learning model for ASD classification from behavioral questionnaire data with interpretable outputs.

- Materials: Public ASD behavioral dataset (e.g., UCI Autism Screening Adult), Python/R with scikit-learn/XGBoost/TabPFN libraries, SHAP library.

- Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values, normalize numerical features, and encode categorical variables.

- Feature Selection/Engineering: Use mutual information, correlation analysis, or domain knowledge to select relevant features (e.g., social responsiveness scores, repetitive behavior scales).

- Model Training & Tuning: Split data into training/validation sets. Train a TabPFNMix regressor (or comparable model like XGBoost) using cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters.

- Performance Evaluation: Test the model on a held-out test set. Calculate accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC.

- Interpretability Analysis: Apply SHAP to the trained model. Generate: a. Summary Plot: Displays global feature importance. b. Force/Waterfall Plots: Explains individual predictions.

- Ablation Study: Systematically remove preprocessing steps or key feature groups to quantify their impact on performance [6].

Diagnostic Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative ASD Diagnostic Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for ASD Diagnostic Research

| Item | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADOS-2 | Diagnostic Instrument | Gold-standard direct observation tool for eliciting and coding social-communicative behaviors. | Module 1-4, Toddler Module. Requires rigorous training for reliability [1] [2]. |

| ADI-R | Diagnostic Instrument | Comprehensive, structured caregiver interview assessing developmental history and lifetime symptoms. | Used alongside ADOS for a comprehensive diagnostic battery [1]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Software Library (XAI) | Explains output of any ML model by calculating feature contribution to individual predictions, enabling interpretability. | Critical for translating AI model outputs into clinically understandable insights [6]. |

| TabPFN | ML Model | A transformer-based model designed for small-scale tabular data classification with prior-fitted networks, offering strong baseline performance. | Used in state-of-the-art XAI frameworks for structured medical data [6]. |

| ABIDE & Kaggle ASD Datasets | Research Database | Large, publicly available repositories of fMRI preprocessed data (ABIDE) and facial images (Kaggle) for training and validating computational models. | Essential for developing and benchmarking DL models in neuroimaging and computer vision approaches [8]. |

| Safe-Level SMOTE | Data Preprocessing Algorithm | An advanced oversampling technique to address class imbalance in datasets by generating synthetic samples for the minority class. | Improves model generalization when ASD case numbers are lower than controls [7]. |

The application of deep learning (DL) to autism Spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis represents a paradigm shift in neurodevelopmental research, offering the potential to identify objective biomarkers and automate complex diagnostic processes. DL, a subset of machine learning (ML) that uses artificial neural networks with multiple layers, can learn intricate structures from large datasets and perform tasks such as classification and prediction with high accuracy [11]. Traditional ASD diagnosis relies heavily on behavioral observations and clinical interviews, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), which can be time-consuming, subjective, and require specialized training [12] [6]. The integration of quantitative, data-driven approaches using neuroimaging and behavioral data sources addresses critical limitations of traditional methods, enabling earlier, more accurate, and more objective identification of ASD. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the primary data sources powering these advanced DL models, detailing their experimental protocols, performance metrics, and practical research applications to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Deep learning models for ASD diagnosis primarily utilize data from two broad categories: neuroimaging and behavioral phenotyping. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, performance, and considerations for the most prominent data sources.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Data Sources for Deep Learning in ASD Diagnosis

| Data Source | Core Description | Common DL Architectures | Reported Accuracy Range | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) [13] [14] | Functional connectivity matrices derived from low-frequency blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) fluctuations at rest. | SVM, CNN, FCN, AE-FCN, GCN, LSTM, Hybrid LSTM-Attention [15] [16] | 60% - 81.1% [15] [14] [16] | Captures brain network dynamics; extensive public datasets (e.g., ABIDE). | Heterogeneity across sites; high dimensionality; requires complex preprocessing. |

| Structural MRI (sMRI) [11] [13] | Volumetric and geometric measures of brain anatomy (e.g., cortical thickness, grey/white matter volume). | SVM, 3D CNN, Autoencoders [13] [15] | 60% - 96.3% [13] | Provides static anatomical biomarkers; high spatial resolution. | Findings can be heterogeneous; may not reflect functional deficits directly. |

| Facial Image Analysis [12] [17] | RGB images or videos analyzed for atypical facial expressions, gaze, or muscle control. | CNN (VGG16/19, ResNet152), Hybrid ViT-ResNet, Xception [12] [17] | 78% - 99% [12] [18] | Non-invasive, low-cost; potential for high-throughput screening. | Can be influenced by environment/emotion; requires careful ethical consideration. |

| Vocal Analysis [12] | Analysis of speech recordings for atypical patterns, prosody, and acoustics. | Traditional ML & DL techniques [12] | 70% - 98% [12] | Non-invasive; can be collected via simple audio recordings. | Confounded by co-occurring language delays; less researched. |

Performance Metrics and Heterogeneity

Reported performance metrics for these data sources vary significantly. A meta-analysis of DL approaches for ASD found an overall high aggregate sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 93%, with an area under the summary receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.98 [18]. However, this analysis noted substantial heterogeneity among included studies, limiting definitive conclusions about clinical practicality [18]. Another meta-analysis focusing specifically on rs-fMRI and ML reported more modest summary sensitivity (73.8%) and specificity (74.8%) [14]. This performance gap highlights a critical trend: studies using smaller, more homogeneous samples often report higher accuracy, while those using larger, more heterogeneous datasets (better reflecting real-world variability) report more conservative but potentially more generalizable performance [16]. For instance, one study using a standardized evaluation framework on the large, multi-site ABIDE dataset found that five different ML models all achieved a classification accuracy of approximately 70%, suggesting that dataset characteristics may be a more significant factor than the choice of model algorithm itself [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Processing

Neuroimaging-based DL pipelines involve a multi-stage process from data acquisition to model training. The following diagram illustrates a standard workflow for an rs-fMRI analysis pipeline.

Standard rs-fMRI Deep Learning Workflow

- Data Acquisition: Large, publicly available datasets are commonly used. The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) is a cornerstone resource, aggregating rs-fMRI, sMRI, and phenotypic data from over 2000 individuals with ASD and typical controls (TC) across multiple international sites [14]. Data is typically collected using standardized MRI protocols on 3T scanners.

- Preprocessing Pipeline: Raw rs-fMRI data undergoes extensive preprocessing to remove artifacts and standardize the data across subjects. Key steps include slice-timing correction, realignment for head motion correction, spatial normalization to a standard template (e.g., MNI space), spatial smoothing, and regression of nuisance signals (e.g., white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and motion parameters) [13] [14].

- Feature Extraction: Preprocessed data is used to extract features for model input. A common approach involves parcellating the brain into Regions of Interest (ROIs) using a predefined atlas (e.g., AAL, CC200, HO). The average time series for each ROI is extracted, and a functional connectivity (FC) matrix is constructed by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between the time series of every pair of ROIs [15] [16]. This matrix, representing the brain's functional network, serves as the input feature for DL models.

- Model Training and Validation: The dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets. Models are trained to classify individuals as ASD or TC based on the input features. Given the relatively small sample sizes in neuroimaging, cross-validation (e.g., subject-level 5-fold cross-validation) is critical to ensure generalizability and avoid overfitting [15] [16]. Ensemble methods, which combine predictions from multiple models, are often used to improve performance and robustness [16].

Advanced Modeling Techniques

More advanced protocols move beyond static FC matrices. For example, one study used a hybrid LSTM-Attention model to analyze the raw or windowed ROI time series data directly, capturing both long-term and short-term temporal dynamics in brain activity [15]. This approach, validated on ABIDE data, achieved an accuracy of 81.1% on the HO brain atlas, outperforming models that used static correlation matrices [15]. Another protocol used graph convolutional networks (GCNs) to model the brain as a graph, where nodes are ROIs and edges are defined by functional connectivity, directly learning from the graph structure [16].

Behavioral Data Acquisition and Processing

Behavioral data, particularly facial analysis, offers a less invasive and more scalable data source. The protocol for this modality is distinctly different from neuroimaging.

Facial Expression Analysis Deep Learning Workflow

- Data Collection: Video data is collected from participants during social interactions. Studies show that unstructured play environments can lead to higher diagnostic accuracy compared to highly structured diagnostic assessments, as they may elicit more naturalistic behavior [19]. The Kaggle ASD Children Facial Image Dataset is a commonly used public resource for this research [18].

- Preprocessing and Input: Videos are processed to extract individual frames. Faces are then detected and aligned within these frames to ensure consistency. The processed facial images are normalized and resized to serve as input for the DL model.

- Model Architecture and Training: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the standard architecture for image-based data. Studies often use transfer learning, where a pre-trained model (e.g., VGG16, ResNet152) on a large general image dataset (e.g., ImageNet) is fine-tuned on the ASD facial image dataset [17]. A recent advancement involves hybrid models that combine CNNs with Vision Transformers (ViTs). For instance, one study found that a hybrid ViT-ResNet152 model achieved a classification accuracy of 91.33%, outperforming ResNet152 alone (89%) by leveraging the CNN's strength in spatial feature extraction and the ViT's ability to model global contextual relationships [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers embarking on DL projects for ASD diagnosis, a core set of data, tools, and algorithms is essential. The following table details these key "research reagents."

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Deep Learning in ASD Diagnosis

| Reagent Category | Specific Tool / Resource | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Datasets | ABIDE I & II [11] [14] | The primary public repository for rs-fMRI and sMRI data, enabling large-scale neuroimaging-based DL studies. |

| ADHD-200 Consortium Data [11] | Provides neuroimaging data for comparative studies between ASD and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). | |

| Kaggle ASD Children Facial Image Dataset [18] | A key public dataset of facial images for training and validating DL models for behavioral phenotyping. | |

| Core Algorithms | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [13] [14] [16] | A robust, traditional ML classifier often used as a baseline for comparison with more complex DL models. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [11] [15] [17] | The standard architecture for analyzing image-based data, including sMRI and facial images. | |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [15] [16] | Specifically designed to operate on graph-structured data, making it ideal for analyzing brain functional connectivity networks. | |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) & Hybrid Models [11] [15] | Used to model temporal sequences, such as ROI time series from fMRI; often combined with attention mechanisms. | |

| Technical Frameworks | Transfer Learning & Fine-Tuning [17] | A technique where a model pre-trained on a large dataset is adapted to the specific task of ASD classification, improving performance with limited data. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) - SHAP [6] | Methods like Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) provide interpretable insights into model decisions, building trust and identifying key predictive features. | |

| Cross-Validation & Ensemble Methods [18] [16] | Critical evaluation techniques to ensure model generalizability and improve performance by combining multiple models. |

The pursuit of deep learning-assisted ASD diagnosis leverages a diverse ecosystem of neuroimaging and behavioral data sources, each with distinct strengths and methodological considerations. Neuroimaging modalities like rs-fMRI provide a direct window into the brain's functional architecture, offering biologically grounded biomarkers, though they require complex acquisition and processing pipelines. In contrast, behavioral data sources, particularly facial expression analysis, provide a more scalable and cost-effective approach, with emerging hybrid models demonstrating impressive classification performance.

A critical insight from recent research is that no single data source or model architecture universally dominates. Performance is highly dependent on data quality, sample heterogeneity, and rigorous validation protocols. The future of this field lies not only in refining individual models but also in the thoughtful integration of multimodal data—combining neuroimaging, behavioral, and genetic information—to build more comprehensive and robust diagnostic tools. Furthermore, the adoption of Explainable AI (XAI) will be paramount for translating these "black-box" models into clinically trusted and actionable systems. For researchers and drug developers, this comparative guide underscores the importance of selecting data sources and experimental protocols that align with their specific research goals, whether for discovering novel biological mechanisms or developing scalable screening tools.

Within the ongoing research thesis focused on comparing deep learning models for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis, this guide provides a structured, objective comparison of the major architectural paradigms [20]. The shift from traditional, subjective diagnostic methods towards data-driven, AI-assisted tools represents a significant advancement in the field [12]. This analysis synthesizes experimental data from recent studies to evaluate the performance, applicability, and methodological nuances of convolutional, recurrent, graph-based, transformer, and hybrid deep learning models applied to neuroimaging and behavioral data.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Deep Learning Architectures

The following tables summarize the quantitative performance metrics of various deep learning architectures as reported in recent studies utilizing different data modalities.

Table 1: Performance of Architectures on Neuroimaging Data (fMRI/sMRI)

| Deep Learning Architecture | Data Modality | Reported Accuracy (%) | Key Dataset | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Convolutional-Recurrent Neural Network | s-MRI + rs-fMRI (Multimodal Fusion) | 96.0 | ABIDE | [21] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | rs-fMRI (Functional Connectivity) | 70.22 | ABIDE I | [22] |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) | rs-fMRI (Functional Brain Network) | 72.40 | ABIDE I | [23] |

| Semi-Supervised Autoencoder (SSAE) | rs-fMRI (Functional Connectivity) | ~74.1* | ABIDE I | [24] |

| Multi-task Transformer Framework | rs-fMRI | State-of-the-art (Specific metrics not provided in snippet) | ABIDE (NYU, UM sites) | [25] |

| Autoencoder-based Classifier | s-MRI (Generated/Reconstructed images) | Effective results (Specific metrics not provided in snippet) | ABIDE | [26] |

*Derived from experimental results comparing SSAE to previous two-stage autoencoder models [24].

Table 2: Performance of Architectures on Behavioral & Visual Data

| Deep Learning Architecture | Data Modality | Reported Accuracy (%) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-LSTM) | Eye-Tracking (Scanpaths) | 99.78 | [27] |

| Xception (Deep CNN) | Facial Image Analysis | 98 | [12] |

| Hybrid (Random Forest + VGG16-MobileNet) | Facial Image Analysis | 99 | [12] |

| LSTM | Voice/Acoustic Analysis | 70 - 98 (Range) | [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multimodal Neuroimaging Fusion with Hybrid CNN-RNN

Objective: To classify ASD by fusing structural (s-MRI) and resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) data for enhanced accuracy [21]. Protocol:

- Data Source: T1-weighted s-MRI and T2-weighted rs-fMRI data were obtained from the multi-site Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) repository [21].

- Preprocessing: Data were preprocessed using the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) atlas within the SPM12 and CONN toolboxes. Steps included functional realignment, slice-timing correction, normalization to MNI space, and smoothing [21].

- Network Construction & Fusion: A hybrid deep learning model combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) was implemented. Three fusion strategies (early, late, cross) were evaluated to integrate features from s-MRI (structural properties) and rs-fMRI (time-series BOLD signals) [21].

- Validation: A five-fold cross-validation strategy was employed on the ABIDE dataset to evaluate classification performance (ASD vs. Healthy Control) [21].

Multi-task Learning with Transformer Framework

Objective: To improve ASD identification by leveraging information from multiple related rs-fMRI datasets (tasks) using a transformer-based model [25]. Protocol:

- Data & Preprocessing: rs-fMRI data from two selected sites (NYU, UM) in the ABIDE dataset were preprocessed using four different pipelines (CCS, C-PAC, DPARSF, NIAK). Strategies varied in band-pass filtering and global signal regression [25].

- Model Architecture: A multi-task transformer framework was proposed. It included a temporal encoding module to capture sequential information from rs-fMRI time-series data and an attention mechanism to extract ASD-related features from each dataset [25].

- Feature Sharing: A dedicated module was designed to share the learned ASD features across the different task-specific datasets, exploiting correlations to improve generalization [25].

- Evaluation: The model's performance was evaluated on the two-site ABIDE data in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity against state-of-the-art methods [25].

Semi-Supervised Learning with Autoencoders

Objective: To diagnose ASD using functional connectivity patterns from rs-fMRI by jointly learning latent features and classification in a semi-supervised manner [24]. Protocol:

- Feature Extraction: Functional connectivity matrices were constructed from the preprocessed rs-fMRI time-series data from the ABIDE I dataset.

- Model Design: A semi-supervised autoencoder (SSAE) was constructed, combining an unsupervised autoencoder for learning hidden representations with a supervised neural network classifier. The model was trained to simultaneously minimize the reconstruction error of the autoencoder and the classification loss [24].

- Training Advantage: This joint optimization allows the latent features learned by the autoencoder to be tuned specifically for the classification task. The framework can also incorporate unlabeled data to improve feature learning [24].

- Validation: The model was evaluated using cross-validation on the ABIDE I database and compared to two-stage autoencoder-classifier models [24].

Eye-Tracking Analysis with CNN-LSTM

Objective: To diagnose ASD by analyzing spatial and temporal patterns in eye-tracking scanpath data [27]. Protocol:

- Data Collection: Eye-tracking data was gathered from children (ASD and Typically Developing) as they viewed images and videos.

- Preprocessing & Feature Selection: Data preprocessing handled missing values and categorical features. Mutual information-based feature selection was used to identify and retain the most relevant features for ASD diagnosis [27].

- Hybrid Model Architecture: A CNN-LSTM model was employed. The CNN component was designed to extract spatial features from the visual representation of gaze patterns (e.g., fixation maps or encoded scanpaths), while the LSTM component processed the sequential/temporal dynamics of the eye movement series [27].

- Evaluation: The model's performance was assessed using stratified cross-validation, achieving high accuracy on the clinical eye-tracking dataset [27].

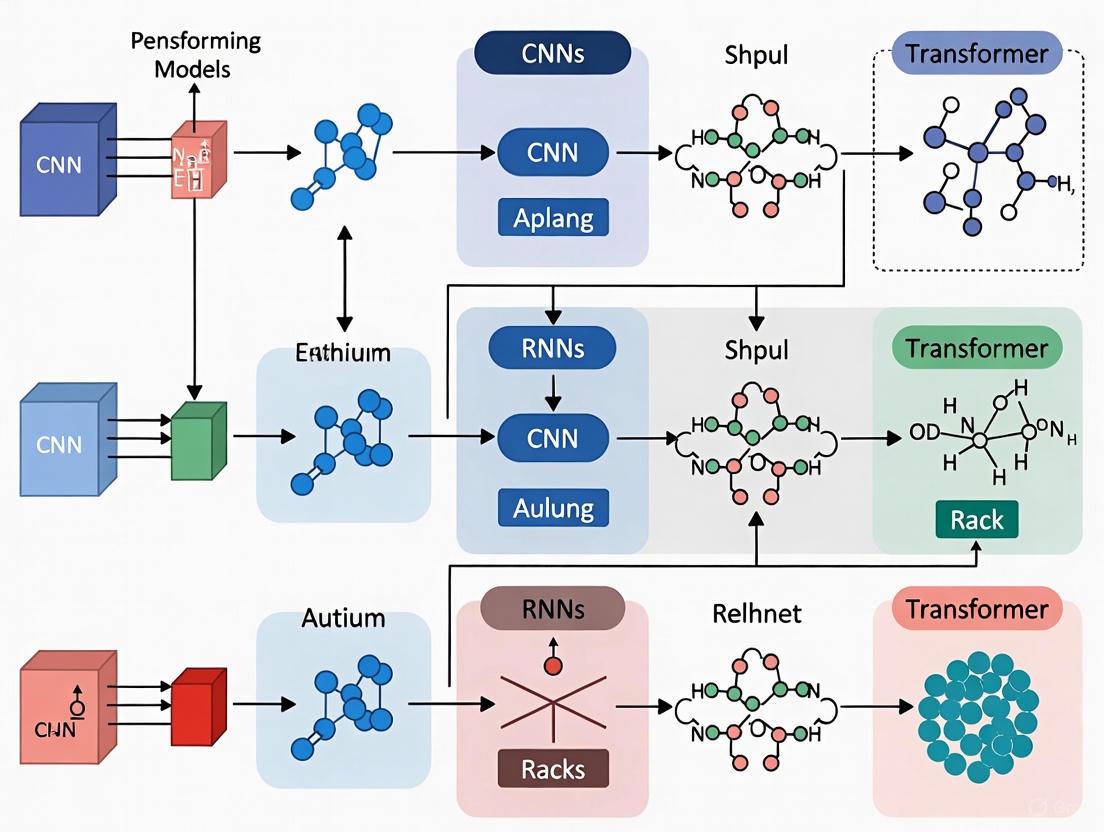

Architectural and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for Multimodal MRI Fusion

Diagram 2: Generic Hybrid CNN-RNN/LSTM Architecture

Diagram 3: Graph Attention Network for Functional Brain Networks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function in ASD DL Research | Example Source/Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE (I & II) Dataset | Neuroimaging Data Repository | Primary source of resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) and structural MRI (s-MRI) data for training and validating models for ASD vs. control classification. | [21] [23] [22] |

| MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) Atlas | Brain Atlas | Standard template for spatial normalization and registration of neuroimaging data across subjects, enabling group-level analysis and feature extraction. | [21] |

| AAL (Automated Anatomical Labeling) Atlas | Brain Atlas | Provides a predefined parcellation of the brain into Regions of Interest (ROIs), used for constructing functional connectivity matrices or networks. | [23] |

| SPM (Statistical Parametric Mapping) Software | Analysis Toolbox | A suite of MATLAB-based tools for preprocessing, statistical analysis, and visualization of brain imaging data (e.g., realignment, normalization, smoothing). | [21] |

| CONN Toolbox | Functional Connectivity Toolbox | A MATLAB/SPM-based toolbox specialized for the computation, analysis, and denoising of functional connectivity metrics from rs-fMRI data. | [21] |

| Preprocessed Connectomes Project (PCP) Pipelines | Data Preprocessing | Provides standardized, openly available preprocessing pipelines for ABIDE data, ensuring consistency and reproducibility across different studies. | [22] |

| Eye-Tracking Datasets (Clinical) | Behavioral Data | Provides raw gaze coordinates, fixation durations, and scanpaths during social stimuli viewing, used as input for models like CNN-LSTM to identify atypical attention patterns. | [27] |

| Python Deep Learning Libraries (TensorFlow/PyTorch) | Software Framework | Essential programming environments for implementing, training, and evaluating complex deep learning architectures (CNNs, GNNs, Transformers, Autoencoders). | Implied in all model development. |

The selection of appropriate benchmark datasets is a fundamental step in developing and validating deep learning models for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis. These datasets provide the foundational data upon which models are trained, tested, and compared, directly impacting the reliability, generalizability, and clinical applicability of research findings. The landscape of available resources is diverse, encompassing large-scale neuroimaging repositories, curated platform datasets, and specialized clinical collections, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations. Understanding these nuances is critical for researchers aiming to make informed choices that align with their specific research objectives and methodological approaches.

The emergence of open data-sharing initiatives has dramatically transformed autism research, enabling investigations at a scale previously impossible for single research groups. We are now in an era where brain imaging data is readily accessible, with researchers more willing than ever to share data, and large-scale data collection projects are underway with the vision of enabling secondary analysis by numerous researchers in the future [28]. These datasets help address the statistical power problems that have long plagued the field [28]. However, combining data from multiple sites or datasets requires careful consideration of site effects, and data harmonization techniques are an active area of methodological development [28].

Comprehensive Dataset Comparison

The following table provides a detailed comparison of the primary dataset types used in deep learning for autism diagnosis, summarizing their core characteristics, data modalities, and primary research applications.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Autism Research Datasets

| Feature | ABIDE | Kaggle | Clinical Repositories | Move4AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Large-scale brain connectivity & structure [29] | Various, often focused on specific challenges | Targeted clinical populations & biomarkers | Multimodal motor function [30] |

| Data Modalities | rs-fMRI, sMRI, phenotypic [29] | Varies by competition; can include behavioral, genetic, video | EEG, biomarkers, detailed clinical histories | EEG, 3D motion capture, neuropsychological [30] |

| Sample Size | 1,000+ participants (ASD & controls) across sites [29] | Typically smaller, competition-dependent | Generally smaller, focused cohorts | 34 participants (14 ASD, 20 controls) [30] |

| Accessibility | Data use agreement required [28] | Public, immediate download | Often restricted, requires ethics approval | Likely requires data use agreement [30] |

| Key Strengths | Large sample, multi-site design, preprocessed data available | Immediate access, specific problem formulation | Rich clinical phenotyping, specialized assessments | Unique multimodal pairing of neural and motor data [30] |

| Limitations | Site effects, heterogeneous acquisition protocols | Potentially limited clinical depth, variable quality | Smaller samples, limited generalizability | Small sample size, specialized paradigm [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ABIDE: Deep Learning Classification Protocol

Research utilizing the ABIDE dataset for deep learning-based ASD classification typically follows a structured pipeline. A representative study used a deep learning approach to classify 505 individuals with ASD and 530 matched controls from the ABIDE I repository, achieving approximately 70% accuracy [29]. The methodology typically involves:

Data Preprocessing: This includes standard steps like slice timing correction, motion correction, normalization to a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI), and spatial smoothing. A key step involves extracting the BOLD time series from defined Regions of Interest (ROIs). One common approach calculates pairwise correlations between time series from non-overlapping grey matter ROIs (e.g., 7,266 ROIs), resulting in a large 7266×7266 functional connectivity matrix for each subject [29].

Feature Engineering: The functional connectivity matrices serve as the input features. These matrices represent the correlation between the BOLD signals of different brain regions, quantifying their functional connectivity. Studies may address site effects using a General Linear Model (GLM) that correlates the connectivity matrix with subject variables like age, sex, and handedness, and then adjusts the values [29].

Model Architecture and Training: The referenced study employed a combination of supervised and unsupervised deep learning methods to classify these connectivity patterns. This approach aims to reduce the subjectivity of manual feature selection, allowing for a more data-driven exploration of neural patterns associated with ASD. The model is then trained and validated, often using cross-validation techniques to ensure robustness [29].

Kaggle-Style Competitions: Model Benchmarking

Kaggle and similar platforms host competitions that provide standardized datasets and evaluation metrics, enabling direct comparison of different algorithms and approaches. The experimental protocol generally follows these steps:

Data Partitioning: The competition organizers provide pre-defined training and test sets. The training set is used for model development, while the test set is used to evaluate the final model's performance and rank participants on a public leaderboard.

Model Development: Participants experiment with various machine learning and deep learning architectures. For example, a review of ASD detection models found that Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) applied to neuroimaging data from the ABIDE repository achieved an accuracy of 99.39%, while traditional models like Logistic Regression (LR) offered high efficiency with minimal processing time [31].

Performance Evaluation: Models are evaluated on a fixed set of metrics (e.g., accuracy, AUC-ROC, F1-score) on the hold-out test set. This standardized evaluation allows for an objective comparison of diverse methodologies.

Multimodal Data Integration: The Move4AS Workflow

The Move4AS dataset exemplifies a specialized protocol for collecting and integrating multimodal data to study motor functions in autism. The experimental workflow can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Multimodal Data Collection Workflow

This workflow yields a rich dataset where neural activity (EEG) and detailed movement kinematics (3D motion) are temporally synchronized, enabling investigations into the brain-behavior relationship during socially and emotionally contextualized motor tasks like walking and dancing [30].

Performance Analysis and Research Findings

The performance of machine learning models in autism diagnosis varies significantly based on the dataset, features, and algorithm used. The following table synthesizes findings from multiple studies, highlighting the interplay between these factors.

Table 2: Model Performance Across Datasets and Methodologies

| Model Category | Example Algorithm | Reported Performance | Dataset & Key Features | Notable Strengths & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | CNN | 99.39% Accuracy [31] | ABIDE (fMRI) | High accuracy with neuroimaging data; faces challenges in interpretability and multi-modal integration [31]. |

| Deep Learning | Deep Belief Network (DBN) | 70% Accuracy [29] | ABIDE (rs-fMRI functional connectivity) | Applied to large, multi-site sample; demonstrates potential of deep learning on complex connectivity patterns [29]. |

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forest (RF) | Up to 100% Accuracy [31] | Behavioral & Adult datasets | High accuracy in some studies; can be susceptible to overfitting [31]. |

| Traditional ML | Logistic Regression (LR) | 100% Accuracy (efficiency-driven) [31] | Behavioral data (toddler) | Efficient with minimal processing time; suitable for rapid screening applications [31]. |

| Traditional ML | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | ~68% Accuracy (vs. 90% with DBN features) [29] | Multi-site Schizophrenia data (T1-weighted MRI) | Performance can be significantly improved by using features extracted from deep learning models [29]. |

Key findings from the literature indicate that while complex models like CNNs and ensemble methods can achieve very high accuracy on specific tasks and datasets, the choice of model often involves a trade-off between performance and practical considerations like computational efficiency and interpretability [31]. Furthermore, the modality of the data is a critical factor; for instance, CNN models have shown particular strength when applied to neuroimaging data [31].

Successful deep learning research in autism diagnosis relies on a suite of data, software, and methodological tools. The table below details key resources mentioned across the surveyed literature.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Autism Deep Learning Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE | Data Repository | Provides pre-existing aggregated fMRI and phenotypic data for ASD and controls [28] [29]. | Serves as a primary benchmark dataset for developing and testing neuroimaging-based classification models. |

| OpenNeuro | Data Platform | Hosts multiple public MRI, MEG, EEG, and iEEG datasets, facilitating data sharing and reuse [28] [32]. | An alternative source for finding neuroimaging data, including over 500 public datasets. |

| BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure) | Standard | Defines a consistent folder structure and file naming convention for organizing brain imaging data [28]. | Critical for ensuring data interoperability, simplifying data sharing, and enabling use with standardized processing pipelines. |

| g.Nautilus EEG System | Hardware | A wireless EEG headset used for recording neural activity in naturalistic settings [30]. | Enabled the collection of the Move4AS dataset during movement tasks, which is not feasible in a traditional fMRI scanner. |

| OptiTrack Flex 3 | Hardware | A marker-based optical motion capture system for precise 3D movement tracking [30]. | Used in the Move4AS dataset to capture detailed kinematics during motor imitation paradigms. |

| Psychtoolbox-3 | Software | A Matlab and GNU Octave toolbox for generating visual and auditory stimuli [30]. | Used to program the experimental paradigm and present instructions and stimuli in controlled laboratory studies. |

| FAIR Guiding Principles | Framework | Promotes that digital assets are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [28]. | A foundational concept in the modern neuroinformatics landscape that underpins the ethos of data sharing. |

The comparative analysis of ABIDE, Kaggle, and clinical repositories reveals a trade-off between scale, depth, and specificity. ABIDE offers unparalleled scale for neuroimaging studies but introduces heterogeneity, while clinical repositories provide deep phenotyping at the cost of smaller sample sizes. Kaggle-style datasets facilitate rapid model benchmarking but may lack the clinical richness needed for translational impact.

Future progress in the field will likely be driven by several key developments. First, the integration of multi-modal data—combining neuroimaging with behavioral, genetic, and electrophysiological data—is a promising avenue for creating more robust and accurate models [31] [30]. Second, addressing challenges of data harmonization across different sites and scanners is crucial for improving the generalizability of findings [28]. Finally, a growing emphasis on model interpretability, often termed Explainable AI (XAI), will be essential for building clinical trust and uncovering the underlying biological mechanisms of autism [31]. As these trends converge, deep learning models are poised to become more accurate, reliable, and ultimately, more useful in clinical practice.

Deep Learning Architectures in Action: Methodologies for fMRI, Facial, and Eye-Tracking Analysis

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has emerged as a dominant, non-invasive tool for studying brain function by capturing neural activity through blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast [33]. In autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, analyzing resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) data presents significant challenges due to its high dimensionality, complex spatiotemporal dynamics, and subtle, distributed patterns of neural alteration [34] [33]. Deep learning models, particularly those combining Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with attention mechanisms, have demonstrated considerable promise in addressing these challenges by extracting meaningful temporal dependencies and spatial features from fMRI time-series data [34] [15]. These models offer the potential to identify objective biomarkers for ASD, potentially supplementing current subjective diagnostic methods that rely on behavioral observations and clinical interviews [34] [15].

The integration of LSTM networks, capable of learning long-term dependencies in sequential data, with attention mechanisms, which selectively weight the importance of different input features, creates a powerful architecture for capturing the complex dynamics of brain functional connectivity [35] [15]. This comparative guide examines the performance of LSTM-Attention models against other methodological approaches for fMRI time-series classification in ASD, providing researchers and clinicians with an evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate analytical tools.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Deep Learning Models for ASD Classification

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures on fMRI Data for ASD Classification

| Model Architecture | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | AUC | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM-Attention (HO Atlas) | ABIDE | 81.1 | - | Residual channel attention, sliding windows | [15] |

| LSTM-Attention (DOS Atlas) | ABIDE | 73.1 | - | Multi-head attention, feature fusion | [15] |

| Attention-based LSTM | ABIDE | 74.9 | - | Dynamic functional connectivity, sliding window | [34] |

| Simple MLP Baseline | Multiple fMRI | Competitive | - | Applied across time, averaged results | [36] |

| Transformer (with pre-training) | ABIDE & ADNI | - | 0.98* | Self-supervised pre-training, masking strategies | [37] |

| 3D CNN | ABIDE | ~70.0 | - | Spatial feature extraction | [15] |

| SVM (Traditional ML) | ABIDE | ~72.0 | - | Static functional connectivity | [15] |

Note: AUC values approximated from performance descriptions in source materials. Exact values not provided in all sources.

Table 2: Deep Learning Model Performance Based on Meta-Analysis (2024)

| Model Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning (Overall) | 0.95 (0.88-0.98) | 0.93 (0.85-0.97) | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | Multiple |

| Deep Learning (ABIDE) | 0.97 (0.92-1.00) | 0.97 (0.92-1.00) | - | ABIDE |

| Deep Learning (Kaggle) | 0.94 (0.82-1.00) | 0.91 (0.76-1.00) | - | Kaggle |

Data synthesized from meta-analysis of 11 predictive trials based on DL models involving 9495 ASD patients [8]

The performance data reveals that LSTM-Attention hybrid models consistently achieve competitive accuracy ranging from 73.1% to 81.1% on the challenging ABIDE dataset, which aggregates heterogeneous rs-fMRI data across multiple sites [15]. Notably, these models demonstrate particular effectiveness when incorporating specialized preprocessing techniques such as sliding window segmentation and advanced feature fusion mechanisms [15]. The residual channel attention module described in recent research helps enhance feature fusion and mitigate network degradation issues, contributing to improved performance [15].

Surprisingly, a simple multi-layer perceptron (MLP) baseline applied to feature-engineered fMRI data has been shown to compete with or even outperform more complex models in some cases, suggesting that temporal order information in fMRI may contain less discriminative information than commonly assumed [36]. This finding challenges the automatic preference for parameter-rich models and emphasizes the importance of validating performance gains against simpler baselines.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Standards

The methodologies employed across studies share common foundational elements, particularly the use of the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) database, which aggregates neuroimaging data from multiple independent sites [34] [15]. Standard preprocessing pipelines typically include slice time correction, motion correction, skull-stripping, global mean intensity normalization, nuisance regression (to remove motion parameters and physiological signals), and band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) [34].

To address the significant challenge of site-related variability in multi-site studies, researchers commonly employ data harmonization methods such as ComBat, which adjusts for systematic biases arising from different MRI scanners and protocols while preserving biological signals of interest [34]. The use of standardized brain atlases for region of interest (ROI) parcellation, particularly the Craddock 200 (CC200) and Harvard-Oxford (HO) atlases, enables consistent feature extraction across studies [34] [15].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Atlases | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | ABIDE Database | Multi-site repository of rs-fMRI data from ASD and TC participants |

| CC200, AAL, HO Atlases | Standardized brain parcellation for ROI-based analysis | |

| Preprocessing Tools | CPAC Pipeline | Automated preprocessing of rs-fMRI data |

| ComBat Harmonization | Removes site-specific effects in multi-site studies | |

| Computational Frameworks | TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning model implementation |

| REST, AFNI, SPM | Neuroimaging data analysis and visualization |

Temporal Feature Extraction Approaches

A critical methodological variation concerns how temporal dynamics are captured from fMRI time-series. The sliding window approach represents the most common strategy, dividing the preprocessed rs-fMRI data into sequential segments using a window size of 30 seconds and step size of 1 second to capture dynamic changes in functional connectivity [34]. Alternatively, some studies utilize the entire ROI time series, often transforming them into Pearson correlation matrices to represent functional connectivity patterns [15].

Recent innovative approaches have incorporated self-supervised pre-training tasks, such as reconstructing randomly masked fMRI time-series data, to address over-fitting challenges in small datasets [37]. Experiments comparing masking strategies have demonstrated that randomly masking entire ROIs during pre-training yields better model performance than randomly masking time points, resulting in an average improvement of 10.8% for AUC and 9.3% for subject accuracy [37].

LSTM-Attention Architecture Specifications

The core architectural elements of high-performing LSTM-Attention models typically include multiple key components. The LSTM module processes sequential ROI data, capturing long-range temporal dependencies in fMRI time-series through its gating mechanisms that regulate information flow [15]. The attention mechanism, particularly multi-head attention, enables the model to dynamically weight the importance of different brain regions or time points, enhancing interpretability by highlighting potentially clinically relevant features [34] [15].

Many recent implementations incorporate specialized fusion modules, such as residual blocks with channel attention, to effectively combine features extracted by both LSTM and attention pathways while mitigating gradient degradation issues [15]. The final classification is typically performed using fully connected layers that integrate the processed temporal and spatial features for binary ASD vs. control classification [15].

Interpretation of Model Performance and Clinical Relevance

The performance advantages of LSTM-Attention models appear to stem from their capacity to capture dynamic temporal dependencies in functional connectivity patterns, which static approaches may miss [34]. Studies examining atypical temporal dependencies in the brain functional connectivity of individuals with ASD have found that these dynamic patterns can serve as potential biomarkers, potentially offering greater discriminative power than static connectivity measures [34].

Beyond raw classification accuracy, the attention weights generated by these models provide valuable interpretability, potentially highlighting neurophysiologically meaningful patterns that align with established understanding of ASD pathophysiology [38] [15]. For instance, the visualization of top functional connectivity features has revealed differences between ASD patients and healthy controls in specific brain networks [15]. This interpretability is crucial for clinical translation, as it helps build trust in model predictions and may generate novel neuroscientific insights.

The robustness of LSTM-Attention models across different data conditions, including their maintained performance under noise interference as demonstrated in similar applications to Parkinson's disease diagnosis, suggests potential for real-world clinical implementation where data quality is often variable [38].

LSTM-Attention models represent a powerful approach for fMRI time-series analysis in ASD diagnosis, demonstrating competitive performance against alternative deep learning architectures and traditional machine learning methods. Their ability to capture dynamic temporal patterns in functional connectivity, combined with inherent interpretability through attention mechanisms, positions them as promising tools for developing objective neuroimaging-based biomarkers.

Future research directions should focus on developing more standardized evaluation protocols across diverse datasets, enhancing model interpretability for clinical translation, and exploring semi-supervised or self-supervised approaches to reduce dependence on large labeled datasets [37]. As the field progresses toward brain foundation models pre-trained on large-scale neuroimaging datasets [33], LSTM-Attention architectures will likely play a significant role in balancing performance with interpretability for clinical ASD diagnosis.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for Facial Image Classification

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social interaction, communication, and repetitive behaviors. Traditional diagnostic methods rely heavily on clinical observation and standardized assessments like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), which are time-consuming, subjective, and require specialized expertise [39] [12]. The global prevalence of ASD has been steadily increasing, with recent estimates suggesting approximately 1 in 44 children are affected, creating an urgent need for scalable, objective screening tools [6] [40] [41].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as powerful deep learning architectures for automating ASD detection through facial image analysis. These models can identify subtle facial patterns and biomarkers associated with ASD that may be imperceptible to human observers [39] [12]. Research indicates that children with ASD often exhibit distinct facial characteristics including differences in eye contact, facial expression production and recognition, and visual attention patterns [12] [42]. By leveraging transfer learning from models pre-trained on large face datasets, researchers can develop accurate classification systems even with limited medical imaging data [39].

The application of CNN-based facial image classification for ASD detection represents a paradigm shift from traditional diagnostic approaches, offering numerous advantages including non-invasiveness, scalability, reduced subjectivity, and the potential for earlier intervention. This comparison guide systematically evaluates the performance, methodologies, and implementation considerations of prominent CNN architectures applied to ASD classification from facial images.

Comparative Performance Analysis of CNN Architectures

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Multiple studies have investigated the efficacy of various CNN architectures for ASD detection through facial image analysis. The table below summarizes the performance metrics of prominent models reported in recent literature:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CNN Architectures for ASD Classification

| Model Architecture | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Dataset | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG19 | 98.2 | - | - | - | Kaggle | [39] |

| CoreFace (EfficientNet-B4) | 98.2 | 98.0 | 98.7 | 98.3 | Not specified | [43] |

| VGG16 (5-fold cross-validation) | 99.0 (validation), 87.0 (testing) | 85.0 | 90.0 | 88.0 | Pakistani autism centers | [44] |

| CNN-LSTM (Eye Tracking) | 99.78 | - | - | - | Eye tracking dataset | [42] |

| Hybrid (RF + VGG16-MobileNet) | 99.0 | - | - | - | Multiple | [12] |

| Xception | 98.0 | - | - | - | Multiple | [12] |

| MobileNet | 95.0 | - | - | - | Kaggle | [39] |

| ResNet50 V2 | 92.0 | - | - | - | Multiple | [39] [43] |

A meta-analysis of AI-based ASD diagnostics confirmed high accuracy across models, reporting pooled sensitivity of 91.8% and specificity of 90.7%. Hybrid models (deep feature extractors with classical classifiers) demonstrated the highest performance (sensitivity 95.2%, specificity 96.0%), followed by conventional machine learning (sensitivity 91.6%, specificity 90.3%), with deep learning alone showing slightly lower metrics (sensitivity 87.3%, specificity 86.0%) [45].

Architecture-Specific Strengths and Limitations

Table 2: Architecture Comparison for ASD Facial Image Classification

| Model Architecture | Strengths | Limitations | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16/VGG19 | High accuracy with transfer learning, well-established architecture | Parameter-heavy, slower inference time | High (138M/144M parameters) |

| CoreFace (EfficientNet-B4) | State-of-the-art performance, integrated attention mechanisms | Complex implementation, requires significant tuning | Moderate |

| MobileNet | Efficient for real-time applications, suitable for mobile deployment | Lower accuracy compared to larger models | Low (4.3M parameters) |

| InceptionV3 | Multi-scale feature extraction, efficient grid reduction | Complex architecture, requires careful hyperparameter tuning | Moderate (23.9M parameters) |

| Xception | Depthwise separable convolutions, strong feature extraction | Computationally intensive, longer training times | High |

| ResNet50 | Residual connections prevent vanishing gradient, reliable performance | Lower accuracy compared to newer architectures | Moderate (25.6M parameters) |

Beyond standard architectural comparisons, several studies have proposed novel frameworks specifically designed for ASD detection. The CoreFace model incorporates a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) as the neck and Mask R-CNN as the head, with integrated attention mechanisms including Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks and Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to improve feature learning from facial images [43]. Another approach combines fuzzy set theory with graph-based machine learning, constructing population graphs where nodes represent individuals and edges are weighted by phenotypic similarities calculated through fuzzy inference systems [46].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Experimental Framework

Research in CNN-based ASD classification from facial images typically follows a structured experimental pipeline with several key phases:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Studies utilize diverse datasets including the Kaggle ASD dataset, ABIDE dataset, and locally collected samples from autism centers [39] [44]. Standard preprocessing techniques include face detection and alignment, histogram equalization (such as Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization - CLAHE), Laplacian Gaussian filtering for feature enhancement, and normalization [43]. Data augmentation strategies commonly applied include horizontal flipping, random rotation, scaling, brightness adjustment, and noise addition to improve model generalization [39] [43].

Model Development and Training: The experimental protocols typically involve transfer learning from CNN models pre-trained on ImageNet or VGGFace datasets, followed by domain-specific fine-tuning on ASD facial image data [39]. Optimization approaches vary across studies, with popular choices including Adam, AdaBelief, and stochastic gradient descent with momentum [44] [43]. A critical consideration is addressing class imbalance in ASD datasets through techniques such as weighted loss functions, oversampling, or modified sampling strategies [39].

Validation and Interpretation: Robust evaluation typically employs k-fold cross-validation (commonly 5-fold) to mitigate overfitting and provide reliable performance estimates [44]. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques including Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) are increasingly integrated to visualize discriminative facial regions and provide interpretable insights for clinicians [39] [6] [43].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for CNN-based ASD classification from facial images

Hyperparameter Optimization Strategies

Optimal performance of CNN models for ASD classification requires careful hyperparameter tuning. Studies have systematically evaluated various configurations:

- Batch Size: Research indicates smaller batch sizes (2-8) often yield superior performance for ASD classification tasks, with VGG16 achieving optimal validation accuracy (99%) with a batch size of 2 [44].

- Learning Rate Schedulers: Adaptive learning rate methods like Adam and cyclical learning rates have demonstrated improved convergence and final performance compared to fixed learning rates [44].

- Regularization Techniques: Combining multiple regularization approaches including dropout (typically 0.2-0.5), L2 weight decay (1e-4 to 5e-4), and early stopping prevents overfitting on limited ASD datasets [39].

- Optimizer Selection: Comparative studies show Adam optimizer generally outperforms SGD with momentum for ASD classification, though AdaBelief has shown promise in specialized architectures like CoreFace [44] [43].

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing CNN-based ASD classification requires specific computational frameworks and datasets. The following table details essential research reagents for this domain:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CNN-based ASD Classification

| Reagent/Framework | Type | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VGGFace Pre-trained Weights | Model Weights | Transfer learning initialization for facial feature extraction | Initialization for VGG16/VGG19 models before fine-tuning on ASD datasets [39] |

| Kaggle ASD Dataset | Dataset | Benchmark dataset for comparative analysis of ASD classification models | Primary training and evaluation dataset used in multiple studies [39] [44] |

| ABIDE Dataset | Dataset | Multi-site neuroimaging dataset including structural and functional scans | Graph-based ASD detection using phenotypic and fMRI data [46] |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Framework | Deep learning libraries for model implementation and training | Core implementation frameworks for custom CNN architectures [39] [43] |

| Grad-CAM | Visualization Tool | Generation of visual explanations for CNN predictions | Identifying discriminative facial regions in CoreFace model [43] |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | XAI Library | Model-agnostic explanation of classifier outputs | Interpreting VGG19 predictions for ASD classification [39] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | XAI Library | Unified framework for interpreting model predictions | Explaining TabPFNMix model decisions for ASD diagnosis [6] |

| OpenCV | Library | Image processing and computer vision operations | Face detection, alignment, and preprocessing in CoreFace pipeline [43] |

Integration with Clinical Practice

Explainable AI for Clinical Translation

The "black-box" nature of deep learning models presents a significant barrier to clinical adoption of CNN-based ASD diagnostic tools. Explainable AI (XAI) methods have become essential components of modern ASD classification frameworks, providing transparent reasoning behind model decisions and building trust with clinicians [39] [6].

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) generates visual explanations by highlighting important regions in facial images that influence the model's classification decision. In the CoreFace framework, Grad-CAM visualizations identified heightened attention to periocular regions and specific facial landmarks, potentially corresponding to known ASD-related characteristics such as reduced eye contact and atypical facial expressivity [43].

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) provides both local and global interpretability, quantifying the contribution of individual features to model predictions. In ASD diagnostic frameworks, SHAP analysis has identified social responsiveness scores, repetitive behavior scales, and parental age at birth as the most influential factors in model decisions, aligning with known clinical biomarkers and reinforcing clinical validity [6].

Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) creates locally faithful explanations by perturbing input samples and observing changes in predictions. Studies integrating LIME with VGG19 models for ASD classification have enhanced transparency by identifying facial regions that influence classification decisions, helping bridge the gap between deep learning predictions and clinical relevance [39].

Diagram 2: Explainable AI workflow for interpretable ASD classification

Multi-Modal Integration and Future Directions

While facial image analysis provides a non-invasive and scalable approach to ASD screening, integration with complementary data modalities enhances diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility. Studies have demonstrated that combining facial image analysis with behavioral assessments, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), improves classification performance compared to unimodal approaches [39]. A multimodal concatenation model incorporating both facial images and ADOS test results achieved 97.05% accuracy, significantly outperforming models using either modality alone [39].

Emerging research directions include:

- Hybrid Architectures: Combining deep feature extractors with classical machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) has demonstrated superior performance compared to standalone deep learning models, with hybrid approaches achieving sensitivity of 95.2% and specificity of 96.0% [45].

- Cross-Population Validation: Developing models robust to demographic variations including ethnicity, age, and gender remains challenging. Studies highlight that datasets are often biased toward specific demographics, restricting generalizability [40].

- Real-World Implementation: Translation to clinical practice requires addressing computational efficiency constraints. Lightweight architectures like MobileNet (95% accuracy) offer potential for deployment in resource-limited settings [39].

Future research should focus on standardized benchmarking across diverse populations, integration of temporal dynamics in facial behavior, and development of culturally adaptive models to ensure equitable access to AI-enhanced ASD diagnostics across global healthcare systems.

The application of deep learning for the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a paradigm shift from subjective behavioral assessments to objective, data-driven approaches. Among various physiological markers, eye-tracking scanpath analysis has emerged as a particularly promising biomarker, as individuals with ASD exhibit characteristic differences in visual attention, especially toward social stimuli [47]. Hybrid deep learning architectures that integrate convolutional neural networks (CNN) with long short-term memory (LSTM) networks have demonstrated exceptional capability in capturing both spatial and temporal patterns in eye-tovement data, achieving diagnostic accuracies exceeding 99% in controlled experiments [27]. This review provides a comprehensive performance comparison of these hybrid models against alternative deep learning and traditional machine learning approaches, detailing experimental protocols, architectural implementations, and clinical applicability for researchers and drug development professionals working in computational psychiatry.

Performance Comparison of Scanpath Analysis Models

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Eye-Tracking Analysis Models for ASD Diagnosis

| Model Type | Specific Model | Accuracy (%) | AUC (%) | Sensitivity/Specificity | Dataset Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid CNN-LSTM | CNN-LSTM with feature selection | 99.78 | - | - | Social attention tasks [27] |

| Hybrid CNN-LSTM | CNN-LSTM on clinical data | 98.33 | - | - | Clinical eye-tracking data [27] |

| Deep Learning | MobileNet | 100.00 | - | - | 547 scanpaths (328 TD, 219 ASD) [48] |

| Deep Learning | VGG19 | 92.00 | - | - | 547 scanpaths (328 TD, 219 ASD) [48] |

| Deep Learning | DenseNet169 | - | - | - | 547 scanpaths (328 TD, 219 ASD) [48] |

| Deep Learning | DNN | - | 97.00 | 93.28% Sens, 91.38% Spec | 547 scanpaths (328 TD, 219 ASD) [49] |

| Traditional ML | SVM | 92.31 | - | - | Eye-tracking from conversations [27] |

| Traditional ML | MLP | 87.00 | - | - | Eye-tracking clinical data [27] |

| Traditional ML | Feature engineering + ML/DL | 81.00 | - | - | Saliency4ASD [50] |

| VR-Enhanced | Bayesian Decision Model | 85.88 | - | - | WebVR emotion recognition [51] |

Table 2: Model Advantages and Limitations for Research Applications

| Model Type | Strengths | Limitations | Clinical Implementation Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-LSTM Hybrid | Superior spatiotemporal feature learning; Handles sequential dependencies; High accuracy | Complex architecture; Computationally intensive; Requires large datasets | High for controlled environments |

| CNN Architectures | Excellent visual feature extraction; Pre-trained models available | Limited temporal modeling; May miss scanpath sequence patterns | Moderate to High |

| Traditional ML | Computationally efficient; Interpretable models | Requires manual feature engineering; Lower performance | Moderate |

| VR-Enhanced Systems | Ecologically valid testing environments; Rich multimodal data | Specialized equipment needed; Complex data integration | Low to Moderate |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CNN-LSTM Implementation for Scanpath Classification

The superior performance of CNN-LSTM hybrid models stems from their sophisticated architecture that simultaneously processes spatial and temporal dimensions of eye-tracking data. The typical implementation involves a multi-stage pipeline:

Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection: Raw eye-tracking data undergoes meticulous preprocessing to address missing values and noise artifacts. Categorical features are converted to numerical representations, followed by mutual information-based feature selection to identify the most discriminative features for ASD detection [27]. This step typically reduces the feature set by 20-30% while improving model performance by eliminating redundant variables.

Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction: The preprocessed data flows through parallel feature extraction pathways. The CNN component, typically comprising 2-3 convolutional layers with ReLU activation, processes fixation maps and scanpath images to extract hierarchical spatial features [49]. Simultaneously, the LSTM component processes sequential gaze points, saccades, and fixations to model temporal dependencies in visual attention patterns [27]. The fusion of these pathways occurs in fully connected layers that integrate both spatial and temporal features for final classification.

Model Training and Validation: Implementations typically employ stratified k-fold cross-validation (k=5 or k=10) to ensure robust performance estimation and mitigate overfitting [27]. Class imbalance techniques, including synthetic data generation through image augmentation, are commonly applied to improve model generalization [49]. Optimization uses Adam or RMSprop optimizers with categorical cross-entropy loss functions.

Performance Validation Protocols

Rigorous experimental validation is essential for assessing model efficacy:

Dataset Specifications: Studies utilize standardized datasets with eye-tracking recordings from both ASD and typically developing (TD) participants. Sample sizes range from approximately 60 participants [27] to larger cohorts of 547 scanpaths [48]. Data collection typically involves participants viewing social stimuli (images/videos) while eye movements are recorded using Tobii or SMI eye trackers.

Evaluation Metrics: Comprehensive assessment extends beyond accuracy to include sensitivity, specificity, area under the ROC curve (AUC), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) [49]. These multiple metrics provide a nuanced view of model performance, particularly important for clinical applications where false negatives and false positives carry significant consequences.

Benchmarking: Models are compared against traditional machine learning approaches (SVM, Random Forest) and other deep learning architectures (DNN, CNN, MLP) to establish performance superiority [27] [48]. Statistical significance testing validates that performance improvements are not due to random variation.

Architectural Framework and Signaling Pathways

CNN-LSTM Hybrid Model Architecture for ASD Diagnosis

The architectural workflow begins with raw eye-tracking data containing fixation coordinates, saccadic paths, and pupil metrics. The preprocessing stage addresses data quality issues and extracts fundamental eye movement events (fixations, saccades, smooth pursuits) using velocity-threshold algorithms [52]. The mutual information-based feature selection identifies the most discriminative features for ASD detection, typically finding that velocity, acceleration, and direction parameters provide optimal classification performance [52].

The CNN component processes spatial features from fixation heatmaps and scanpath visualizations, leveraging convolutional layers to identify characteristic ASD gaze patterns such as reduced attention to eyes and increased focus on non-social stimuli [48]. Simultaneously, the LSTM network models temporal sequences of gaze points, capturing dynamic attention shifts that differentiate ASD individuals, including atypical scanpaths and impaired joint attention patterns [27]. The feature fusion layer integrates these spatial and temporal representations, with the classification layer ultimately generating diagnostic predictions.

Experimental Workflow for Model Validation

Experimental Validation Workflow

The standard experimental protocol for validating CNN-LSTM models in ASD diagnosis follows a systematic workflow. Participant recruitment involves carefully characterized ASD and typically developing control groups, with sample sizes typically ranging from 50-500 participants depending on study scope [27] [48]. Stimulus presentation employs social scenes, facial expressions, or interactive virtual environments designed to elicit characteristic gaze patterns in ASD individuals [51].

Eye-tracking recording utilizes high-precision equipment (Tobii, SMI, or Eye Tribe systems) capturing gaze coordinates, pupil diameter, and fixation metrics at sampling rates typically between 60-300Hz [47]. Data preprocessing applies filtering algorithms to remove artifacts and extracts fundamental eye movement events using velocity-threshold identification [52]. Feature engineering calculates kinematic parameters (velocity, acceleration, jerk) and constructs scanpath visualizations for spatial analysis.

Model training implements the CNN-LSTM architecture with stratified k-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance estimation [27]. The final performance evaluation comprehensively assesses accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC metrics, comparing results against traditional diagnostic approaches and other machine learning models to establish clinical utility [49].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Eye-Tracking Based ASD Research

| Research Tool | Specifications | Primary Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Eye-Tracking Hardware | Tobii Pro series, SMI RED, Eye Tribe | High-precision gaze data acquisition with 60-300Hz sampling rate [47] |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Presentation, E-Prime, Custom WebVR | Controlled display of social and non-social visual stimuli [51] |

| Data Preprocessing Tools | MATLAB, Python (PyGaze) | Artifact removal, fixation detection, saccade identification [52] |

| Feature Extraction Libraries | OpenCV, Scikit-learn | Calculation of kinematic features and scanpath visualization [27] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, Keras, PyTorch | Implementation of CNN, LSTM, and hybrid architectures [27] [48] |

| Validation Suites | Custom cross-validation scripts | Performance evaluation using AUC, sensitivity, specificity [49] |

| Virtual Reality Platforms | WebVR, A-Frame | Ecologically valid testing environments [51] |