Deconstructing Heterogeneity in Autism: A Roadmap for Biomarker Discovery and Precision Medicine

The profound heterogeneity of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents a central challenge for biomarker discovery and the development of targeted therapies.

Deconstructing Heterogeneity in Autism: A Roadmap for Biomarker Discovery and Precision Medicine

Abstract

The profound heterogeneity of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents a central challenge for biomarker discovery and the development of targeted therapies. This article synthesizes the latest research to provide a comprehensive framework for navigating this complexity. We first explore the foundational genetic, environmental, and neurobiological sources of heterogeneity, highlighting recent breakthroughs in identifying biologically distinct subtypes. We then detail advanced methodological approaches, from multi-omics integration to AI-driven analysis, that are essential for parsing this diversity. The discussion critically addresses persistent troubleshooting challenges, including statistical limitations and biomarker reliability, and provides actionable optimization strategies. Finally, we evaluate validation frameworks and comparative analyses that are translating research findings into clinically relevant tools, paving the way for a new era of precision medicine in autism for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Roots of Diversity: Unpacking the Genetic, Environmental, and Biological Sources of Heterogeneity

FAQs: Core Concepts and Research Frameworks

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of heterogeneity in ASD that impact biomarker discovery? Heterogeneity in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) arises from several interconnected factors that pose significant challenges for identifying universal biomarkers. Key sources include:

- Genetic Heterogeneity: Over 1,200 genes have been associated with ASD, but no single gene accounts for more than 1-2% of cases. Individuals present with diverse genetic variants, including de novo mutations, copy number variants, and single base mutations [1].

- Clinical and Developmental Heterogeneity: Individuals with ASD exhibit a wide range of symptom severity, co-occurring conditions (such as intellectual disability, ADHD, anxiety, and epilepsy), and distinct developmental trajectories [1] [2]. Recent research identifies different socioemotional and behavioural trajectories, with some individuals showing difficulties in early childhood and others developing more pronounced challenges in late childhood or adolescence [2].

- Etiological Heterogeneity: ASD results from the complex interplay of genetic susceptibilities and environmental factors. These include prenatal/perinatal influences like maternal immune activation, inflammation, and exposure to certain medications [3] [1].

FAQ 2: Are there distinct biological subtypes of ASD? Emerging evidence from multi-omics studies and genetic research suggests that biologically distinct subtypes of ASD exist. While clinical subtyping has limited predictive value, research is focusing on identifying homogeneous biological subgroups.

- Genetic Stratification: Recent large-scale genetic studies have demonstrated that the polygenic architecture of ASD can be broken down into at least two genetically correlated factors. One factor is associated with earlier diagnosis and lower social-communication abilities in early childhood, while the other is linked to later diagnosis and increased mental health challenges in adolescence [2].

- Omics-driven Stratification: High-throughput omics methods (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) are being used to deconstruct heterogeneity. These approaches aim to identify molecular subtypes with shared pathological pathways, such as those involving immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, and synaptic function [1].

FAQ 3: What are the most promising experimental approaches to control for heterogeneity in cohort studies? To manage heterogeneity and increase the likelihood of robust biomarker discovery, researchers should consider:

- Stratification by Biological Signature: Instead of grouping by behavioral scores alone, stratify participants based on underlying biological markers identified through omics, EEG, or eye-tracking [4].

- Developmental Trajectory Mapping: Incorporate longitudinal designs to track participants and group them based on their developmental and behavioral trajectories over time, not just cross-sectional data [2].

- Focus on Convergent Mechanisms: Investigate common pathological pathways that may be shared across different genetic backgrounds, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and synaptic pathology [1].

- Multimodal Data Integration: Combine data from multiple sources (genetics, neuroimaging, electrophysiology, behavioral assays) to define more coherent subgroups [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent or Unreplicable Biomarker Signals

- Problem: A biomarker candidate shows promise in an initial cohort but fails to validate in a subsequent study, likely due to undetected heterogeneity within the sample.

- Solution:

- Increase Sample Characterization: Extend phenotyping beyond standard diagnostic criteria to include detailed clinical co-morbidities, family history, and cognitive profiles.

- Apply Pre-Validation Stratification: Before biomarker validation, use unsupervised learning methods (e.g., clustering on multi-omics data) to identify putative subgroups. Validate the biomarker within each subgroup separately [1].

- Utilize Emerging Biomarker Panels: Leverage recently discovered biomarker panels that have demonstrated high accuracy. For instance, one AI-driven platform has identified an mRNA biomarker panel with reported >90% sensitivity and specificity in detecting ASD and its subtypes [5].

Challenge 2: Integrating Multimodal Data from Genetic, Environmental, and Clinical Sources

- Problem: Data from various platforms (e.g., genomics, proteomics, exposome) are siloed, making it difficult to model their complex interactions in relation to ASD outcomes.

- Solution:

- Adopt a Multi-Omics Framework: Use integrative analysis pipelines that can simultaneously model information from different molecular layers (genes, transcripts, proteins) to identify key convergent pathways [1].

- Incorporate Temporal Environmental Data: For environmental factors, utilize novel platforms like temporal exposome sequencing, which can measure over 150 million biochemical data points from a single strand of hair to model how environmental exposures interact with biology over time [6].

- Apply Quantitative AI Platforms: Employ AI platforms designed to agnostically discover and model the non-linear dynamics between biology, behavior, and environmental circumstances [5].

Challenge 3: Differentiating ASD-Specific Pathways from Those Linked to General Neurodevelopmental Delays

- Problem: A identified pathological mechanism (e.g., synaptic dysfunction) may not be specific to ASD but common across multiple neurodevelopmental conditions.

- Solution:

- Include Relevant Control Groups: Ensure study designs include control groups with other neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., ADHD, intellectual disability) to test for specificity.

- Investigate Genetic Correlations: Calculate genetic correlations between your ASD-related findings and other traits. The polygenic factor for later-diagnosed ASD shows higher genetic correlations with ADHD and mental health conditions, suggesting a shared etiology, which is less pronounced for the early-diagnosed factor [2].

- Focus on Core ASD Pathophysiology: Prioritize mechanisms directly linked to the core characteristics of ASD, such as genes enriched in pathways for "social behavior," "cognition," and "synapse organization" as identified in the SFARI gene database analysis [1].

Data Presentation: Performance of Key Diagnostic Tools

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Standardized ASD Diagnostic Instruments. This table summarizes the aggregated sensitivity and specificity of common tools as reported in a recent meta-analysis [7].

| Diagnostic Tool | Full Name | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Primary Use Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADOS | Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule | 87% (79–92%) | 75% (73–78%) | Gold-standard observational assessment |

| ADI-R | Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised | 77% (56–90%) | 68% (52–81%) | Comprehensive parent interview |

| CARS | Childhood Autism Rating Scale | 89% (78–95%) | 79% (65–88%) | Clinician-rated observational and historical tool |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating ASD Etiology. This table outlines essential materials and their applications in contemporary ASD research.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Utility in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated database of ASD-associated genes. | Categorizing genetic risk; pathway and network analysis of ASD susceptibility genes [1]. |

| Multi-Omics Assay Panels | High-throughput measurement of molecular features (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics). | Unbiased profiling for biomarker discovery and stratification of ASD heterogeneity [1]. |

| Temporal Exposome Sequencing | Platform for measuring environmental exposures and biological responses over time from hair samples. | Investigating the dynamic interplay between environmental factors and an individual's biology in ASD etiology [6]. |

| EEG & Eye-Tracking Paradigms | Non-invasive tools for measuring neurocognitive and visual processing. | Providing scalable, objective biomarkers for stratification and predicting intervention outcomes [4]. |

| AI-Driven Biomarker Platforms | Computational platforms for agnostic discovery of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. | Identifying complex, non-linear biomarker patterns from multimodal datasets to diagnose ASD and its subtypes [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Integration for Biomarker Discovery and Stratification

Objective: To identify molecularly defined subtypes of ASD and discover subtype-specific biomarkers by integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Obtain biospecimens (e.g., blood, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons) from a well-characterized ASD cohort and matched controls. Phenotypic data must include DSM-5/ICD-11 criteria, co-occurring conditions, and cognitive scores [8] [7].

- Data Generation:

- Genomics: Perform whole-genome or exome sequencing to identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy number variants (CNVs). Cross-reference findings with the SFARI gene database [1].

- Transcriptomics: Conduct RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on relevant tissues to profile gene expression patterns.

- Proteomics and Metabolomics: Use mass spectrometry-based platforms to quantify protein and metabolite levels.

- Data Integration and Analysis:

- Pathway Convergence Analysis: Use Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis on genetic and transcriptomic data to identify overrepresented biological processes (e.g., synaptic transmission, histone modification, immune response) [1].

- Unsupervised Clustering: Apply computational clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means, hierarchical clustering) to the integrated multi-omics data to identify data-driven subgroups of participants.

- Biomarker Identification: Use machine learning models (e.g., random forest, support vector machines) to identify a minimal panel of molecular features (e.g., mRNA, proteins) that can distinguish ASD subgroups from each other and from controls [1] [5].

Protocol 2: Validating Stratification Biomarkers in an Independent Cohort

Objective: To confirm that the biomarker panel identified in Protocol 1 can reliably stratify a new, independent cohort of individuals with ASD.

Methodology:

- Cohort Recruitment: Recruit a new, independent validation cohort following the same inclusion criteria and sample collection procedures as the discovery cohort.

- Targeted Assay Development: Develop a targeted, cost-effective assay (e.g., qPCR, multiplex immunoassay) to measure only the key biomarkers from the discovered panel.

- Blinded Testing: Apply the targeted assay to the validation cohort in a blinded manner.

- Outcome Correlation: Statistically test whether the predefined biomarker signatures predict the previously established subgroups and, more importantly, correlate with distinct clinical outcomes (e.g., developmental trajectory, treatment response, severity of co-occurring conditions) [4].

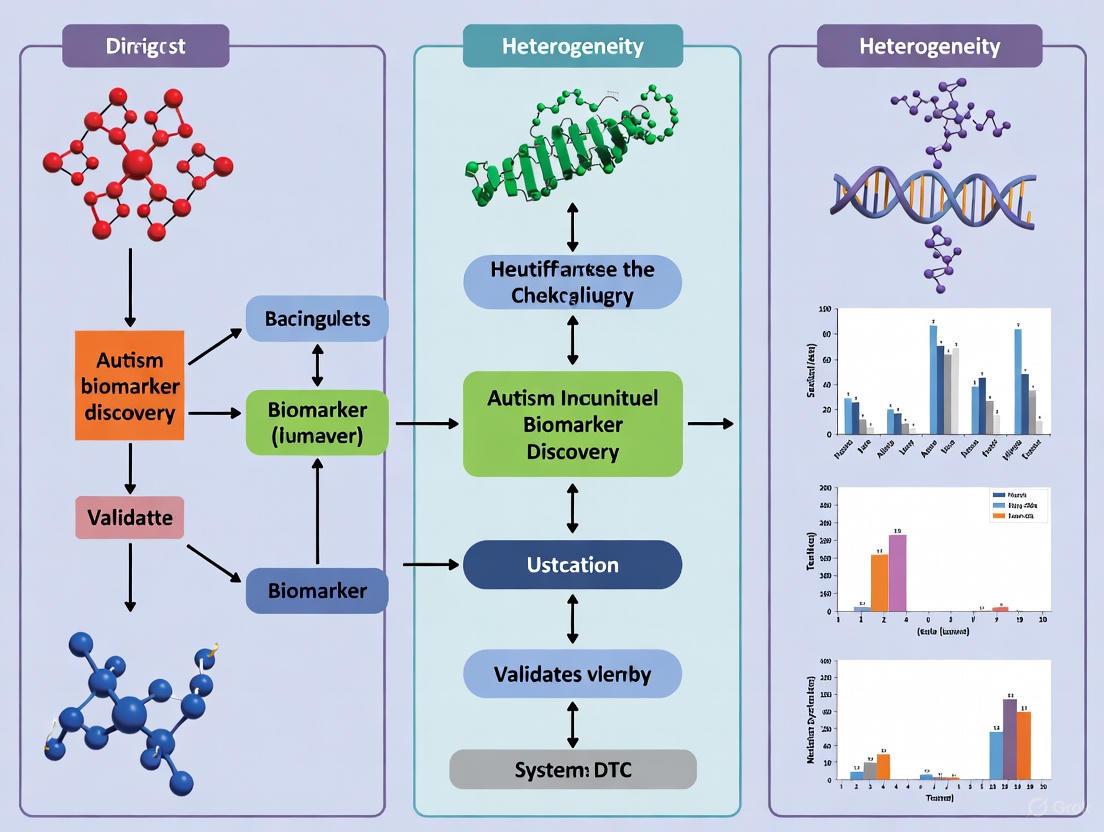

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is not a single condition but a collection of neurodevelopmental conditions with highly heterogeneous manifestations. For researchers, this heterogeneity has been a significant obstacle, making it difficult to identify consistent biomarkers and develop targeted therapies. A groundbreaking study published in Nature Genetics in July 2025 has transformed this challenge into an opportunity by establishing a data-driven framework for decomposing autism into biologically distinct subtypes [9] [10]. This research, analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort, has identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism, each with unique genetic profiles, developmental trajectories, and co-occurring conditions [9] [11]. This article provides a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this new paradigm, offering troubleshooting guidance, methodological protocols, and analytical frameworks for advancing precision medicine in autism.

Subtype Classification & Clinical Profiles

The research team from Princeton University and the Simons Foundation employed a "person-centered" computational approach, analyzing more than 230 traits in each individual to group participants based on their complete phenotypic profiles rather than isolated characteristics [9]. This methodology represents a significant shift from traditional trait-centered approaches and has revealed four distinct autism subtypes with clear clinical presentations.

Table 1: Clinical Profiles of Autism Subtypes

| Subtype Name | Prevalence | Core Clinical Features | Developmental Milestones | Common Co-occurring Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Pronounced social difficulties, repetitive behaviors, communication challenges | Typically reached on time, similar to children without autism | High rates of ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD [9] [11] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Developmental delays, variable social and repetitive behaviors | Significant delays in early milestones (walking, talking) | Typically absence of anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors [9] [12] |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder core autism traits across all domains | Typically reached on time | Generally absence of co-occurring psychiatric conditions [9] [11] |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe challenges across all domains: social, communication, repetitive behaviors | Significant developmental delays | High levels of anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation, often intellectual disability [9] [12] |

The identification of these subtypes provides researchers with a critical framework for stratifying study populations, potentially reducing variance in biomarker studies and increasing statistical power for detecting subtype-specific biological signals.

Distinct Genetic Architectures

Each autism subtype demonstrates a unique genetic signature, revealing distinct biological narratives underlying what was previously considered a single disorder. These genetic differences explain the varied clinical presentations and developmental trajectories observed across subtypes.

Table 2: Genetic Profiles of Autism Subtypes

| Subtype Name | Key Genetic Features | Primary Genetic Pathways Affected | Developmental Timing of Genetic Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | Strong influence of common variants linked to psychiatric traits; polygenic risk for ADHD/depression [11] [13] | Genes active in social/emotional processing; neuronal signaling [9] | Predominantly postnatal gene activity [9] [10] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | Mix of rare inherited variants and some de novo mutations [9] [11] | Chromatin organization, transcriptional regulation [10] | Predominantly prenatal gene activity [9] |

| Moderate Challenges | Less pronounced genetic burden across variants studied | Not specified in available literature | Not specified in available literature |

| Broadly Affected | Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations; genes linked to fragile X syndrome [11] [13] | Brain development, synaptic function [9] | Primarily prenatal with broad developmental impact [9] |

Figure 1: Relationship between genetic profiles and clinical presentations in autism subtypes. DD = Developmental Delay.

Essential Research Reagents & Methodological Toolkit

To implement similar stratification approaches in your research, specific reagents, datasets, and computational tools are required. The following table outlines critical resources for replicating and extending this work.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Application in Subtype Research | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort Data | SPARK dataset (Simons Foundation) [10] | Primary source of phenotypic and genotypic data | >5,000 participants; 230+ phenotypic traits; whole exome/genome sequencing |

| Computational Tools | General Finite Mixture Modeling [10] | Integration of diverse data types and subtype classification | Handles categorical, continuous, and spectrum data simultaneously |

| Genetic Analysis | Whole exome/genome sequencing | Identification of de novo and rare inherited variants | Standard sequencing protocols with family trios when possible |

| Phenotypic Assessment | Standardized autism trait questionnaires | Quantification of core and associated features | Covers social, behavioral, developmental, psychiatric domains |

| Pathway Analysis | Gene set enrichment tools | Linking genetic variants to biological processes | Standard bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., GO, KEGG analysis) |

Experimental Protocols for Subtype Validation

Protocol: Person-Centered Phenotypic Stratification

Purpose: To classify autism research participants into biologically meaningful subtypes using phenotypic data.

Workflow:

- Data Collection: Assemble comprehensive phenotypic data for each participant, including:

- Core autism traits (social communication, restricted/repetitive behaviors)

- Developmental milestones (age at walking, talking)

- Co-occurring conditions (ADHD, anxiety, mood disorders)

- Cognitive and adaptive functioning measures [9]

Data Integration: Apply general finite mixture modeling to handle diverse data types (binary, categorical, continuous) within a unified framework [10].

Subtype Assignment: Calculate probability of subtype membership for each individual based on complete phenotypic profile.

Validation: Confirm subtype stability using cross-validation techniques and replicate findings in independent cohorts [9].

Troubleshooting:

- Missing Data: Implement multiple imputation techniques for incomplete records.

- Model Convergence: Adjust model parameters and increase iterations for complex datasets.

- Cohort Effects: Validate findings across diverse populations to ensure generalizability.

Figure 2: Workflow for phenotypic stratification and biological validation in autism subtyping research.

Protocol: Genetic Validation of Subtypes

Purpose: To identify distinct genetic patterns associated with each autism subtype.

Workflow:

- Genetic Data Processing:

- Process whole exome/genome sequencing data using standard quality control pipelines

- Identify rare inherited variants, de novo mutations, and copy number variations [9]

Variant Burden Analysis:

- Calculate variant burden within each predetermined phenotypic subtype

- Compare burden across subtypes using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., regression models)

Pathway Enrichment Analysis:

- Conduct gene set enrichment analysis for each subtype separately

- Identify biological pathways specifically dysregulated in each subtype [10]

Developmental Timing Analysis:

- Utilize gene expression data across developmental periods (prenatal, postnatal)

- Determine temporal windows of maximal gene expression for subtype-specific genes [9]

Troubleshooting:

- Population Stratification: Include principal components or genetic ancestry measures as covariates.

- Multiple Testing: Apply appropriate correction methods (e.g., Bonferroni, FDR) for genetic analyses.

- Functional Validation: Plan downstream experimental validation of key pathways in model systems.

Integration of Multimodal Biomarkers

Beyond genetics, researchers are exploring multimodal biomarker approaches to refine autism subtyping. A 2025 study demonstrated that integrating neuroimaging and epigenetic data significantly improves ASD classification accuracy compared to either modality alone [14].

Key Biomarker Integration Protocol:

Neuroimaging Data: Acquire structural and functional MRI scans, focusing on thalamocortical connectivity patterns that show hyperconnectivity in ASD [14].

Epigenetic Profiling: Analyze DNA methylation patterns in candidate genes (OXTR, AVPR1A) from saliva or blood samples [14].

Machine Learning Application: Implement eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) or similar algorithms to integrate multimodal data streams for classification [14].

Technical Consideration: When building integrated models, ensure sufficient sample size (N=105+ for medium-large effect sizes) and account for multiple comparisons across data modalities.

Frequently Asked Questions (Researcher Focused)

Q1: How can I apply this subtyping framework to my existing autism research cohort?

A: Begin by collecting comprehensive phenotypic data similar to the SPARK study domains. If genetic data is available, analyze it separately within phenotypic subgroups rather than across the entire cohort. For smaller cohorts, consider collaborative efforts to achieve sufficient sample size for robust subgroup identification [13].

Q2: What are the limitations of current autism subtyping approaches?

A: Key limitations include:

- Limited ancestral diversity in current datasets (primarily European ancestry) [13]

- Potential dynamic nature of traits across development

- Need for validation in independent cohorts

- Integration of environmental factors alongside genetic data [15]

Q3: How does this subtyping approach impact biomarker discovery?

A: Subtyping addresses heterogeneity that has plagued previous biomarker studies. By analyzing biomarkers within more homogeneous subgroups, researchers can achieve:

- Increased statistical power for detecting subtype-specific signals

- More precise correlation between biological measures and clinical presentations

- Development of targeted intervention approaches [14] [16]

Q4: What is the clinical translational potential of these findings?

A: These subtypes show promise for:

- More accurate prognostic predictions

- Tailored intervention planning based on subtype profiles

- Genetic counseling guidance for families

- Stratification for clinical trials [12]

Future Research Directions

The identification of autism subtypes opens numerous avenues for future investigation. Priority areas include:

Expanding Ancestral Diversity: Current findings require validation in ancestrally diverse populations, as genetic variants can differ across ancestral groups [13].

Longitudinal Tracking: Understanding how subtypes evolve across the lifespan will be crucial for developmental trajectory mapping.

Non-Coding Genome Exploration: Investigating the 98% of the genome beyond protein-coding regions may reveal additional regulatory mechanisms [10].

Therapeutic Development: Subtype-specific pathways offer targets for precision medicine approaches in autism treatment.

Environmental Interaction Analysis: Examining how environmental factors interact with genetic profiles within subtypes may reveal modifiable risk factors [15].

This technical resource provides a foundation for researchers to implement subtype-aware approaches in their autism research, potentially accelerating the discovery of biologically meaningful biomarkers and targeted interventions for specific autism subtypes.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

Q1: What is meant by the "genetic architecture" of autism, and why is it important for biomarker discovery?

The genetic architecture of autism refers to the complete spectrum of genetic factors that contribute to the condition, ranging from rare, high-penetrance mutations to common, small-effect genetic variants that collectively form a polygenic liability [17]. Understanding this architecture is fundamental to biomarker discovery because the vast genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity of autism means that no single genetic marker can serve as a universal biomarker [18]. Research must account for this complexity to identify meaningful biological subgroups.

Q2: How do high-penetrance mutations differ from polygenic liability?

- High-Penetrance Mutations: These are rare genetic variants (e.g., copy number variants or protein-disrupting variants in genes like CHD8, SHANK3, or SCN2A) that have a large effect on disease risk, often on their own. They are frequently associated with syndromic forms of autism and other conditions like intellectual disability or epilepsy [17] [19].

- Polygenic Liability: This refers to the combined effect of hundreds or thousands of common genetic variants, each with a very small individual effect on autism risk. Most autism cases are influenced by this type of inherited polygenic background [17] [19]. The additive effect of these variants can push an individual over a diagnostic threshold [20].

Q3: What is a polygenic risk score (PRS), and what are its current limitations in autism research?

A Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) is a single value that summarizes an individual's genetic loading for a trait, calculated as a weighted sum of the number of risk alleles they carry [21]. Key limitations include:

- Incomplete Information: Current PRS capture only a fraction of the known heritability, as they are based on an incomplete list of genetic variants from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [21].

- Ancestry Bias: The predictive accuracy of PRS is currently much higher for individuals of European ancestry because most GWAS data comes from this population. Scores are not directly transferable across diverse ancestral groups, risking health disparities [21].

- Limited Discriminatory Power: For complex disorders like autism, the discriminative ability of PRS at an individual level is still low and not sufficient for standalone diagnostic prediction [21].

Q4: My genetic data shows no known high-penetrance mutations. Does this rule out a genetic cause?

No. The absence of a known high-penetrance mutation does not rule out a genetic cause. Most autistic individuals do not have an identifiable rare causal mutation [20]. Their autism is likely influenced by a combination of:

- A polygenic load of common variants [17] [20].

- Rare variants not captured by current clinical testing.

- Potential interactions between genetic factors and the environment [17].

Q5: How can the heterogeneity in the genetic architecture of autism be leveraged in research?

Instead of treating autism as a single disorder, researchers can stratify or subgroup study participants based on shared biological pathways. For example, a 2025 study identified two genetically distinct factors within autism's polygenic architecture that are correlated with different developmental trajectories and ages at diagnosis [2]. This "stratification" approach can reduce noise and increase the power to discover biomarkers and elucidate pathophysiology [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Genetic and Biomarker Studies

| Challenge | Potential Root Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low predictive accuracy of Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) | Incomplete GWAS data; effect sizes estimated with error; ancestry mismatch between discovery and target cohorts [21]. | Use the largest available, ancestry-matched GWAS summary statistics for score construction. For non-European cohorts, prioritize methods like XP-BLUP that leverage trans-ethnic information [21]. |

| Failure to replicate a biomarker finding | High clinical heterogeneity in the replication cohort; biomarker not specific to autism but to a co-occurring condition; developmental stage differences [18] [22]. | Apply stringent, biologically informed sub-phenotyping (e.g., by age at diagnosis, cognitive profile) [2] [22]. Use multivariate analysis/machine learning with a panel of biomarkers instead of a single marker [23]. |

| Inability to distinguish causal from correlative epigenetic changes | Epigenetic markers (e.g., DNA methylation) are influenced by genetics, environment, and tissue type, making causality difficult to establish [20]. | Integrate epigenomic data with genomic data (e.g., methylation quantitative trait locus analysis). Use longitudinal designs and multi-omics approaches (proteomics, metabolomics) to triangulate evidence [20]. |

| Unexpected variability in phenotypic expression among carriers of the same rare variant | Incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity, modulated by the individual's polygenic background and environmental factors [17] [19]. | Quantify and adjust for the carrier's background PRS for autism and related neurodevelopmental conditions. Deeply phenotype to identify sub-threshold traits. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Differentiating Autism Subgroups by Polygenic Factors and Developmental Trajectories

This protocol is based on a 2025 study that dissected the heterogeneity of autism by linking polygenic architecture to behavioral trajectories [2].

1. Objective: To identify distinct genetic profiles associated with different developmental pathways and ages at autism diagnosis.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Cohort Data: Longitudinal birth cohort data with repeated measures of socioemotional/behavioral development (e.g., Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SDQ) and recorded age at autism diagnosis [2].

- Genotyping Data: Genome-wide genotyping data for autistic individuals within the cohorts.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Identify Behavioral Trajectories. Use Growth Mixture Modeling (GMM) on longitudinal SDQ scores to identify latent subgroups (e.g., "early childhood emergent" vs. "late childhood emergent" trajectories) among autistic individuals [2].

- Step 2: Test Association with Diagnosis Age. Validate the identified trajectories by testing their association with the recorded age at autism diagnosis using chi-square tests or regression [2].

- Step 3: Calculate Polygenic Risk Scores. Using large-scale autism GWAS summary statistics, compute PRS for all individuals.

- Step 4: Deconstruct Polygenic Architecture. Apply genetic factor analysis to the GWAS data to determine if the autism polygenic architecture can be broken down into independent factors. Test the genetic correlation (

rg) between these factors [2]. - Step 5: Correlate Genetic Factors with Trajectories. Test the association between the identified polygenic factors and the behavioral trajectories. The 2025 study found one factor linked to earlier diagnosis and another to later diagnosis and adolescent socioemotional difficulties [2].

- Step 6: Estimate Genetic Correlations with Co-occurring Conditions. Calculate the genetic correlations (

rg) between the identified autism polygenic factors and other traits like ADHD and mental health conditions using LD Score regression [2].

Protocol 2: Integrating Neuroimaging and Epigenetic Data for Classification

This protocol details a multimodal approach to improve the classification of autism, as demonstrated in a 2025 study [23].

1. Objective: To build a machine learning model that integrates brain imaging and epigenetic data with behavioral measures to classify autism.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Participants: Autistic and typically developing control individuals.

- Behavioral Measure: The Adolescent-Adult Sensory Profile (AASP) questionnaire [23].

- MRI Scanner: 3T MRI scanner for structural and resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) [23].

- Biological Samples: Saliva or blood for DNA extraction and epigenetic analysis.

- Software: FreeSurfer for structural MRI analysis; CONN toolbox or SPM for rs-fMRI preprocessing and seed-to-voxel analysis; a machine learning library (e.g., in R or Python) with the XGBoost algorithm [23].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Acquire Behavioral Baseline. Administer the AASP to all participants to establish a baseline of sensory-related behaviors [23].

- Step 2: Acquire and Preprocess Brain Imaging Data.

- Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted structural images and T2-weighted rs-fMRI scans.

- Process structural data with FreeSurfer's

recon-allpipeline to obtain cortical and subcortical volumes. - Preprocess rs-fMRI data (realignment, slice-timing correction, normalization, smoothing). Perform seed-to-voxel analysis with the bilateral thalamus as the seed to compute thalamo-cortical resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) [23].

- Step 3: Acquire and Process Epigenetic Data.

- Extract DNA from saliva.

- Perform bisulfite conversion and DNA methylation analysis for candidate genes (e.g.,

AVPR1A,OXTR) via pyrosequencing or array-based methods. Calculate methylation values at specific CpG sites [23].

- Step 4: Model Development and Comparison.

- Build three classification models using the XGBoost algorithm:

- Neuroimaging-Epigenetic Model: Input features include AASP scores, thalamo-cortical rs-FC, brain volumes, and DNA methylation values.

- Neuroimaging Model: Input features include AASP scores and brain data.

- Epigenetic Model: Input features include AASP scores and DNA methylation data [23].

- Compare the predictive accuracy of the three models to determine if the integrated model outperforms the others.

- Build three classification models using the XGBoost algorithm:

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Genetic Architecture and Biomarker Discovery Logic

Diagram 2: Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Statistics | Used as a reference to calculate Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) in a study cohort. | Sourced from large consortia like the Autism Sequencing Consortium (ASC) or the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC). Must be ancestry-matched [21]. |

| Genotyping Array | Provides genome-wide data on common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from participant DNA. | Arrays like Illumina Global Screening or Infinium PsychArray. Essential for PRS calculation and imputation [2]. |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Identifies rare, high-penetrance coding and non-coding variants. | Used to find novel or known pathogenic mutations not covered by genotyping arrays [17] [19]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Treats DNA to differentiate methylated from unmethylated cytosine residues for epigenetic studies. | Critical for DNA methylation analysis (methylomics) of candidate genes (e.g., AVPR1A, OXTR) or epigenome-wide studies [23] [20]. |

| Longitudinal Behavioral Measures | Tracks developmental trajectories to link with genetic data. | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to identify latent classes linked to age of diagnosis [2]. The Adolescent-Adult Sensory Profile (AASP) provides a behavioral baseline for multimodal studies [23]. |

| 3T MRI Scanner with rs-fMRI Protocol | Acquires structural and functional brain imaging data to identify neural correlates of genetic risk. | Used to measure thalamo-cortical functional connectivity, a potential intermediate phenotype [23]. |

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by vast etiological and phenotypic heterogeneity, which presents a significant challenge for identifying reliable biomarkers [18]. The integration of environmental risk factors into research models is crucial for dissecting this heterogeneity. Key mechanisms include Maternal Immune Activation (MIA), direct exposure to environmental toxicants, and subsequent immune dysregulation [24]. These factors can converge on shared biological pathways, such as chronic neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, which may represent measurable biomarker signatures for specific ASD subgroups [24] [25]. This guide provides technical support for researchers aiming to incorporate these elements into their biomarker discovery pipelines.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary environmental mechanisms I should focus on for ASD biomarker discovery? The most evidence-supported mechanisms involve prenatal and early-life exposures that disrupt immune and metabolic pathways. Maternal Immune Activation (MIA) is a primary model, where maternal inflammation leads to elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-17A, TNF-α) in the fetal environment, altering brain development [24]. Concurrently, exposure to environmental toxicants (e.g., air pollutants, heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants) can induce oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and exacerbate neuroinflammation [24] [26]. The interaction between these insults and genetic susceptibility is a critical area for stratified biomarker identification.

FAQ 2: How does immune dysregulation manifest in study participants with ASD, and what should I measure? Immune dysregulation in ASD can be systemic and central. In blood samples, studies consistently show upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes (e.g., IL-1β, IFN-γ) and elevated plasma levels of cytokines such as TNF-α, particularly in younger children [27] [25]. Metabolomic analyses often reveal concomitant changes, including alterations in amino acid metabolism (e.g., increased phenylalanine) and lipid metabolism [25]. A multi-omics approach that correlates transcriptomic, metabolomic, and epigenetic data is recommended to capture this complexity.

FAQ 3: My study population is highly heterogeneous. How can I account for this in my experimental design? Heterogeneity is a core feature of ASD. To address this, employ stratification strategies based on potential biological subtypes rather than relying solely on behavioral diagnoses [28]. For instance, you can subgroup participants based on their:

- Immune profile: e.g., high vs. normal TNF-α or IL-6 levels [27].

- Metabolic profile: e.g., specific shifts in amino acid or lipid metabolism [25].

- Sensory phenotypes: which may correlate with thalamo-cortical connectivity and epigenetic markers like AVPR1A methylation [23]. Using machine learning algorithms on multimodal data can help identify these data-driven subgroups [23].

FAQ 4: What are the key signaling pathways involved, and which are the most promising therapeutic targets? Key pathways involve neuroimmune interactions and their impact on synaptic function. Prominent pathways include:

- Cytokine Signaling (IL-6, IL-17A, TNF-α): These cytokines can cross the placenta and activate fetal microglia, leading to chronic neuroinflammation and aberrant synaptic pruning [24].

- AVPR1A and OXTR Epigenetic Regulation: DNA methylation of genes encoding vasopressin and oxytocin receptors is linked to sensory and social behavioral phenotypes [23].

- P2X7 Receptor Signaling: This pathway mediates MIA effects through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [24]. Therapeutic targets emerging from these pathways include cytokine blockers, immunomodulatory interventions, and metabolic supplements [24] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Weak Signal in Immune Biomarker Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Participant Age Variability. Immune profiles, especially cytokine levels, can change dramatically with development. For example, TNF-α is significantly higher in children with ASD under 5 years old compared to older children and controls [27].

- Solution: Implement strict age-based stratification in your analysis. Treat age as a continuous covariate in statistical models.

- Cause: Sample Timing and Handling. Cytokine levels are sensitive to circadian rhythms, recent infections, and sample processing delays.

- Solution: Standardize sample collection time of day. Screen for recent illnesses. Use standardized protocols for serum/plasma separation and freeze samples at -80°C promptly.

- Cause: Low Specificity of a Single Biomarker. No single immune marker is universal for ASD [18].

- Solution: Move towards a panel-based approach. Combine multiple cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) with metabolic markers (e.g., phenylalanine) or epigenetic marks to improve sensitivity and specificity [25].

Issue 2: Modeling the Effects of Environmental Toxicants in Experimental Systems

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unrealistic Dosage. Using a single, high-dose exposure does not mimic the chronic, low-level human exposure scenario.

- Solution: Employ low-dose, chronic exposure paradigms in animal or in vitro models. Refer to epidemiological data to inform environmentally relevant concentrations [26].

- Cause: Ignoring Co-Exposures. Humans are exposed to mixtures of toxicants, which can have synergistic effects.

- Solution: Where feasible, design experiments that test combinations of prevalent toxicants (e.g., air pollution PM2.5 and heavy metals) to better model real-world conditions [24].

- Cause: Lack of Mechanistic Link to Neurodevelopment.

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Immune and Metabolic Biomarkers Reported in ASD Research

| Biomarker Category | Specific Marker | Direction of Change in ASD | Associated Phenotype / Note | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | TNF-α | Significantly Elevated | Particularly in children <5 years; not correlated with symptom severity | [27] |

| IL-6 | Trend of Elevation | More pronounced in males; key mediator in MIA models | [27] [24] | |

| IL-1β, IFN-γ | Upregulated (Gene Expression) | Part of activated immune response signature in blood | [25] | |

| Metabolites | Phenylalanine | Increased | Suggests alterations in amino acid metabolism | [25] |

| Citrulline | Increased | Implicated in immune and metabolic dysregulation | [25] | |

| Epigenetic Marks | AVPR1A DNA Methylation | Hypomethylation | Associated with sensory phenotypes and thalamo-cortical connectivity | [23] |

| Brain Connectivity | Thalamo-Cortical rs-FC | Hyperconnectivity | Correlated with sensory abnormalities; a potential neuroimaging biomarker | [23] |

Table 2: Common Environmental Toxicants and Their Documented Immunotoxic Effects

| Toxicant Class | Examples | Key Immunotoxic Effects Relevant to ASD | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | TCDD (Dioxin), PCBs | Reduced lymphocyte response to mitogens; impaired host response to viral infection (influenza); decreased vaccine antibody potency in children | [29] [26] |

| Heavy Metals | Lead (Pb), Cadmium (Cd) | Decreased NK cell number/function; increased inflammatory indicators; reduced vaccine antibody response | [26] |

| Air Pollutants | PM2.5 | Associated with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-8, TNF-α); may modulate innate immunity and increase infection susceptibility | [26] |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Benzo[a]pyrene | Agonists for the AhR receptor; linked to altered immune function in children exposed during development | [29] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Multi-Omic Profiling for Immune-Metabolic Subtyping

This protocol is adapted from recent studies that integrate transcriptomic and metabolomic data to characterize biological subtypes in ASD [25].

1. Sample Collection:

- Collect peripheral blood from fasting participants. For the transcriptomic cohort, draw blood into PAXgene Blood RNA tubes. For the metabolomic cohort, collect blood in EDTA tubes for plasma separation.

2. Transcriptomic Processing (RNA Sequencing):

- RNA Extraction & QC: Isolate total RNA using a standardized kit. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0 recommended).

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Perform ribosomal RNA depletion, followed by library preparation and sequencing on an Illumina platform to a depth of at least 30 million paired-end reads.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment & Quantification: Align reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using STAR and quantify gene-level counts with featureCounts.

- Differential Expression: Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) using DESeq2 (FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.05).

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): Construct co-expression modules to identify groups of genes with highly correlated expression patterns across samples. Relate key modules to clinical traits.

3. Metabolomic Processing (Mass Spectrometry):

- Metabolite Extraction: Precipitate proteins from plasma with cold methanol, then centrifuge and collect the supernatant.

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze extracts using a high-resolution LC-MS system (e.g., UHPLC-QTOF-MS) in both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Data Analysis: Use software like XCMS for peak picking, alignment, and annotation. Perform statistical analysis in MetaboAnalyst to identify Differentially expressed Metabolites (DMs).

4. Data Integration:

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (KEGG, GO) on both DEG and DM lists to identify convergent biological pathways (e.g., "antigen processing and presentation," "linoleic acid metabolism").

- Use multi-omics factor analysis (MOFA) or similar tools to integrate the two datasets and identify latent factors that drive variation across both molecular layers.

Protocol 2: Assessing Maternal Immune Activation (MIA) in Animal Models

This protocol outlines key steps for establishing and validating a poly(I:C)-induced MIA model, a widely used paradigm to study neurodevelopmental effects [24].

1. Animal Model Setup:

- Use timed-pregnant rodents (e.g., C57BL/6 mice).

- Administer a single dose of poly(I:C) (e.g., 20 mg/kg, i.p.) to the dam at a critical gestational time point (e.g., E12.5) to mimic viral infection. Control dams receive saline.

2. Measuring Maternal Immune Response:

- Collect maternal blood and/or placental tissue 3-6 hours post-injection.

- Assay: Measure key pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17A, TNF-α) using ELISA or a multiplex bead-based assay.

3. Evaluating Offspring Phenotypes:

- Behavior: Test adult offspring for ASD-relevant behaviors (e.g., social interaction in the three-chamber test, repetitive behaviors like marble burying, anxiety in the elevated plus maze).

- Molecular: In postnatal offspring, analyze brain tissue for:

- Microglial Activation: IBA1 immunohistochemistry and morphological analysis.

- Cytokine Levels: Measure in brain homogenates (e.g., prefrontal cortex, amygdala).

- Synaptic Markers: Assess protein levels of pre- and post-synaptic markers (e.g., PSD-95, VGLUT1) via Western blot.

- Neurophysiology: Use ex vivo slice electrophysiology to examine excitatory/inhibitory balance in relevant circuits.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

MIA and Environmental Toxicant Convergence Pathway

Diagram Title: Converging Pathways of MIA and Toxicants on Neurodevelopment

Multi-Omic Biomarker Discovery Workflow

Diagram Title: Multi-Omic Workflow for ASD Biomarker Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Assays for Investigating Immune Dysregulation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Cytokine Assay Kits | Simultaneously quantify multiple cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17A) from serum/plasma or tissue homogenates. | Luminex xMAP technology or MSD electrochemiluminescence assays. Ideal for low-volume samples. |

| ELISA Kits | Quantify a single, specific protein target with high sensitivity. | Used for validating specific findings from multiplex panels (e.g., specific IL-6 or TNF-α ELISA). |

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Stabilize intracellular RNA at the point of collection, ensuring an accurate transcriptomic profile. | Critical for RNA-seq studies from whole blood. |

| DNA Methylation Kits | Extract and bisulfite-convert DNA for epigenetic analysis. | Enables analysis of candidate genes (e.g., OXTR, AVPR1A) or genome-wide profiling (EPIC array). |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for metabolomic sample preparation and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. | Essential for minimizing background noise and ensuring reproducible metabolite identification. |

| Poly(I:C) | A synthetic double-stranded RNA used to simulate viral infection and induce MIA in animal models. | Available in various molecular weights; high-molecular-weight is typically used for robust immune activation. |

| Antibodies for IHC/IF | Visualize and quantify specific cell types and proteins in brain tissue (e.g., IBA1 for microglia, PSD-95 for synapses). | Validate neuroinflammatory and neurodevelopmental findings from molecular data. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can researchers account for heterogeneity in autism when studying epigenetic biomarkers?

The heterogeneity of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) means that a single biomarker is unlikely to apply to all individuals. Recent research has identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism, each with different genetic profiles and developmental trajectories [9]. When designing experiments, it is crucial to stratify participants into these or similar subgroups to ensure meaningful results. The subtypes are:

- Social and Behavioral Challenges (37% of participants): Core autism traits with typical developmental milestones but frequent co-occurring conditions like ADHD and anxiety [9].

- Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19% of participants): Later achievement of developmental milestones (e.g., walking, talking), without signs of anxiety or depression [9].

- Moderate Challenges (34% of participants): Milder core autism behaviors, typical developmental milestones, and generally no co-occurring psychiatric conditions [9].

- Broadly Affected (10% of participants): The most severe and wide-ranging challenges, including developmental delays, social difficulties, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions [9].

These subgroups are associated with distinct genetic patterns. For example, the "Broadly Affected" subgroup showed the highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations, while only the "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay" group was more likely to carry rare inherited genetic variants [9]. Using a stratified, "person-centered" approach that considers over 230 traits, rather than searching for genetic links to single traits, is essential for revealing meaningful biological mechanisms [9].

Q2: What is the relationship between epigenetic age (DNAmAge) and brain age in the context of neurological health?

DNAmPhenoAge, one measure of epigenetic age derived from whole blood, has been identified as a significant mediator between chronological age and global brain age, which is estimated from structural MRI [30]. This means that the effect of a person's chronological age on their brain structure is partially explained by their epigenetic age.

Advanced DNAmPhenoAge is specifically related to accelerated aging in brain regions higher on the sensorimotor-to-association (S-A) axis [30]. This axis describes cortical organization, where higher-order association cortices (involved in complex cognitive functions) are the last to develop, exhibit prolonged plasticity, and are the first to show age-related atrophy [30]. This relationship persists even after controlling for cardiovascular health, holistic health factors, and socioeconomic status [30].

Q3: Can early-life stress or trauma lead to measurable epigenetic changes that affect brain structure?

Yes, childhood trauma can leave lasting biological marks, often referred to as epigenetic "scars." A multi-epigenome-wide analysis identified four DNA methylation sites consistently associated with child maltreatment: ATE1, SERPINB9P1, CHST11, and FOXP1 [31].

Of particular significance is FOXP1, a gene that acts as a "master switch" for genes involved in brain development. Hypermethylation of FOXP1 was linked to changes in gray matter volume in key brain regions [31]:

- Orbitofrontal cortex: Involved in emotional regulation.

- Cingulate gyrus: Involved in memory retrieval and emotional processing.

- Occipital fusiform gyrus: Involved in social cognition.

This provides a direct biological link between early adverse experiences, epigenetic alterations, and subsequent changes in brain development.

Q4: What are some key epigenetic mechanisms regulating brain development and plasticity?

The primary epigenetic mechanisms that choreograph brain development and enable lifelong plasticity are [32]:

- DNA Methylation: The covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, typically at CpG dinucleotides. It is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and can be actively removed by Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes. In the brain, neuronal activity can promote rapid changes in DNA methylation at genes regulating plasticity [32].

- Chromatin Modifications: This involves post-translational modifications to the histone proteins around which DNA is wrapped. These include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. These modifications, such as histone acetylation or H3K4me3, can create more open ("active") or compact ("repressive") chromatin states, thereby fine-tuning gene expression [32].

- Non-Coding RNAs: RNA molecules that do not code for proteins but can regulate gene expression by influencing transcription, splicing, and mRNA degradation [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background or Non-Specific Signal in Immunofluorescence

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate blocking | Perform a blocking step with a 2-5% solution of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or a 5-10% solution of serum from the species in which the secondary antibody was raised [33]. | Using the Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer as a pre-blocking step can further reduce non-specific labeling [33]. |

| Secondary antibody cross-reactivity | Ensure the species of the secondary antibody is not the same as the species of the sample tissue [33]. | Titrate the antibody to the lowest concentration that provides adequate signal [33]. |

| Low abundance target | Use a signal amplification method, such as Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) [33]. | For fluorophores that bleach quickly, use antifade mounting reagents like SlowFade Diamond or ProLong Diamond [33]. |

Issue 2: Loss of Lipophilic Tracer or Dye Signal During Permeabilization

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Use of detergent or alcohol-based permeabilization | Use a dye that covalently attaches to proteins in the membrane, such as CellTracker CM-DiI [33]. | Standard lipophilic dyes (e.g., DiI) reside in lipids, which are stripped away by detergents like Triton X-100 or methanol fixation [33]. |

| Use of non-fixable dextran | Ensure the dextran used is the fixable form (contains a primary amine) [33]. | The concentration of the tracer can be increased up to 10 mg/mL for a stronger signal [33]. |

Issue 3: Challenges in Transducing Neuronal Cells

- Problem: Neurons are more difficult to transduce than many other cell types.

- Solutions:

- Increase viral titer: Use a higher number of viral particles per cell [33].

- Optimize timing: For primary neurons, transduce them at the time of plating rather than on established cultures [33].

- Adjust expectations: The onset of expression is often slower in neurons, with peak expression typically occurring 2-3 days post-transduction rather than 16 hours [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Key DNA Methylation Age (DNAmAge) Clocks and Their Relation to Brain Structure

Table summarizing epigenetic age estimation methods from whole blood and their association with neuroimaging-derived brain age metrics, as used in recent studies [30].

| DNAmAge Clock | Description | Key Finding in Neuroimaging Study |

|---|---|---|

| PhenoAge | Trained on clinical chemistry markers to capture physiological dysregulation. | Mediates the relationship between chronological age and global BrainAge; associated with advanced BrainAge in higher-order association cortices [30]. |

| Hannum | Based on 71 CpG sites in whole blood, highly correlated with chronological age. | Specific findings not highlighted as primary mediator in the cited path analysis [30]. |

| Horvath | Multi-tissue clock, trained on 353 CpG sites across multiple tissues. | Specific findings not highlighted as primary mediator in the cited path analysis [30]. |

| SkinBlood | Optimized for use in blood and skin samples. | Specific findings not highlighted as primary mediator in the cited path analysis [30]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Key Methodologies

Essential materials and their functions for investigating neurobiological and epigenetic correlates.

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling from biological samples (e.g., whole blood, saliva) [30] [23]. | Used for estimating DNAmAge and for epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) in neurological and psychiatric research [30] [23]. |

| Covalently-bound Lipophilic Tracers (e.g., CellTracker CM-DiI) | Neuronal tracing and membrane labeling that is retained after fixation and permeabilization [33]. | Crucial for experiments requiring intracellular antibody labeling, which involves detergents that strip standard lipophilic dyes [33]. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Kits | Enzyme-mediated signal amplification for detecting low-abundance targets in immunoassays [33]. | Increases detection sensitivity by depositing multiple fluorophore-labeled tyramide radicals at the site of antibody binding [33]. |

| Antifade Mounting Reagents (e.g., SlowFade Diamond) | Preserves fluorescence and reduces photobleaching in fixed cell and tissue preparations [33]. | Essential for imaging fluorophores that are prone to rapid bleaching, allowing for longer imaging sessions and better signal-to-noise ratio [33]. |

| NeuroTrace Nissl Stains | Fluorescently labels Nissl substance (ribosomal RNA) in neuronal cell bodies [33]. | While not entirely neuron-specific, it selectively stains neurons based on high protein synthesis; concentration may need optimization (20- to 300-fold dilution) to reduce glial staining [33]. |

Protocol 1: Path Analysis for Mediating Effects of Epigenetic Age on Brain Age

Objective: To formally test whether epigenetic age (DNAmAge) mediates the relationship between chronological age and global brain age (BrainAge), while controlling for confounders.

Methodology [30]:

- Data Collection:

- BrainAge: Estimate global BrainAge from T1-weighted structural MRI using a validated pipeline (e.g., volBrain) [30].

- DNAmAge: Calculate multiple epigenetic age estimates (e.g., PhenoAge, Hannum, Horvath) from whole blood DNA using the Illumina MethylationEPIC array and the online DNA Methylation Age Calculator [30].

- Covariates: Collect data on self-reported sex, race, cardiovascular health (BMI, HbA1c, pulse pressure), holistic health (PROMIS-57 subscores), and socioeconomic status (education level, household income) [30].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use a mediation analysis framework with a statistical package like Pingouin in Python.

- Model Specification:

- Independent Variable (X): Chronological Age.

- Mediator (M): DNAmAge (test each clock separately).

- Dependent Variable (Y): Global BrainAge.

- Include all covariates as nuisance variables.

- Assess the significance of the indirect effect (Path a*b) using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (e.g., 10,000 iterations) [30].

- The indirect effect is significant if the confidence interval does not cross zero.

Protocol 2: Integrating Sensory Behavior, Neuroimaging, and Epigenetics in ASD

Objective: To classify ASD by integrating sensory behavioral profiles, thalamo-cortical connectivity, and epigenetic markers, thereby addressing heterogeneity.

Methodology [23]:

- Participant Characterization:

- Recruit individuals with ASD and typically developing (TD) controls.

- Assess sensory-related behavior using the Adolescent-Adult Sensory Profile (AASP) questionnaire, which characterizes four patterns: Low Registration, Sensitivity, Sensation Seeking, and Avoidance [23].

- Multimodal Data Acquisition:

- Brain Factors: Acquire structural and resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI). Preprocess data using standard pipelines (e.g., FreeSurfer for structure, SPM/CONN for function). Calculate thalamo-cortical resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) using the bilateral thalamus as a seed [23].

- Epigenetic Factors: Collect saliva samples. Extract DNA and perform methylation analysis for candidate genes implicated in social behavior and sensory processing (e.g., OXTR, AVPR1A, AVPR1B) [23].

- Machine Learning Classification:

- Use the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm to build and compare different models:

- Model 1: Neuroimaging-Epigenetic Model (AASP + rs-FC + DNA methylation).

- Model 2: Neuroimaging Model (AASP + rs-FC).

- Model 3: Epigenetic Model (AASP + DNA methylation).

- Use the sensory behavior (AASP) as the default baseline for all models.

- Evaluate model performance to determine which combination of factors provides the most accurate classification of ASD. The study hypothesized that the integrated neuroimaging-epigenetic model would be superior [23].

- Use the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm to build and compare different models:

Methodological Visualizations

Diagram 1: Analytical Workflow for Integrated ASD Biomarker Discovery

Diagram 2: Epigenetic & Neurobiological Pathways of Early-Life Stress

Advanced Tools for Deconstruction: Multi-Omics, AI, and Person-Centered Approaches

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is fundamentally heterogeneous, encompassing diverse etiologies, clinical presentations, and developmental trajectories. This heterogeneity has persistently challenged traditional reductionist approaches that seek single biomarkers or unified explanations. Research now emphasizes integrating multiple levels of analysis—genetic, epigenetic, neural systems, behavior, and environmental factors—to advance toward precision medicine [34] [35]. The field is transitioning from viewing autism as a single disorder to recognizing "autisms," requiring models that accommodate both categorical subtypes and continuous dimensions of difference [34].

This technical support guide provides troubleshooting resources for researchers implementing integrative approaches to ASD biomarker discovery. It addresses methodological challenges in combining disparate data types, offers standardized protocols for cross-domain integration, and provides frameworks for interpreting complex, multi-level results within a person-centered research paradigm.

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Integrative Research

Q1: Our research group is struggling with integrating neuroimaging and epigenetic data. What analytical approaches can handle this multi-modal complexity?

A1: Machine learning frameworks, particularly eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), have demonstrated efficacy for neuroimaging-epigenetic integration. One successful protocol combined thalamo-cortical resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) measures with DNA methylation values of arginine vasopressin receptor (AVPR) genes, using sensory-related behavior as a baseline reference [14]. This approach identified thalamo-cortical hyperconnectivity and AVPR1A epigenetic modification as significant contributing factors. For optimal results:

- Ensure consistent participant characterization across modalities

- Use standardized pre-processing pipelines for each data type before integration

- Implement cross-validation to prevent overfitting in multi-modal models

- Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) for model interpretability [36]

Q2: How can we address the challenge of small sample sizes in subgroup identification within heterogeneous ASD populations?

A2: Small samples severely limit subgroup detection in ASD heterogeneity. Pursue these strategies:

- Leverage existing large-scale datasets (ABIDE, Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research)

- Employ federated learning approaches that analyze data across multiple sites without sharing raw data

- Utilize data augmentation techniques specific to your data types

- Apply unsupervised clustering algorithms (K-means, hierarchical clustering) to identify data-driven subgroups before validation in larger samples [34]

Current research indicates that sample sizes exceeding 100 participants provide more reliable subgroup identification, with ideal studies including 500+ participants for robust stratification [34].

Q3: What are the best practices for validating biomarker panels across different ASD subpopulations?

A3: Effective validation requires a multi-stage approach:

- Internal validation: Use bootstrapping or cross-validation within your discovery sample

- External validation: Test biomarkers in independent cohorts with different demographic characteristics

- Clinical validation: Assess whether biomarkers predict treatment response or developmental trajectories

- Biological validation: Examine whether identified biomarkers converge on coherent biological pathways

For proteomic biomarkers, one study established a 12-protein panel that identified ASD with AUC = 0.879±0.057, specificity of 0.853±0.108, and sensitivity of 0.832±0.114, with four proteins correlating with ADOS severity scores [37]. This demonstrates the potential of multi-analyte panels over single biomarkers.

Q4: How can we effectively incorporate motor and sensory measures into ASD biomarker studies when most diagnostic instruments focus on social-communication symptoms?

A4: Motor differences are present in 50-85% of autistic individuals and represent a promising domain for biomarker development [38]. Implementation strategies include:

- Supplement standard diagnostic instruments with standardized motor assessments (Peabody Developmental Motor Scales, Movement Assessment Battery for Children)

- Incorporate technological measures (wearable sensors, motion capture) to quantify subtle motor patterns invisible to naked eye observation

- Assess sensory processing using standardized tools like the Adolescent-Adult Sensory Profile (AASP), which characterizes four patterns: Low Registration, Sensitivity, Sensation Seeking, and Avoidance [14]

- Design studies that collect longitudinal motor data to capture developmental trajectories

Q5: What statistical methods best account for the multiple comorbidities and concomitant medical conditions in ASD research?

A5: The Advanced Integrative Model (AIM) reframes "comorbidities" as Concomitant Medical Problems to Diagnosis (CMPD) that may directly influence ASD symptoms [39]. Analytical approaches include:

- Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test causal pathways between CMPD and core ASD symptoms

- Multivariate pattern analysis to identify clusters of co-occurring medical conditions

- Network analysis to map interactions between different biological systems

- Control for CMPD that may confound biomarker signals rather than treating them as nuisance variables

Research shows that treating medical conditions such as gastrointestinal issues, immune dysfunction, and mitochondrial disorders sometimes improves core ASD symptoms, indicating their potential relevance to underlying mechanisms [39].

Quantitative Data Synthesis: Biomarker Findings Across Modalities

Table 1: Multi-Level Biomarker Findings in Autism Research

| Domain | Specific Biomarker | Finding Direction | Effect Size/Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | Thalamo-cortical rs-FC | Hyperconnectivity in ASD | Key feature in classification model | [14] |

| Epigenetic | AVPR1A methylation | Significant contributor to classification | Improved model accuracy in combined approach | [14] |

| Proteomic | 12-protein serum panel | Differentiated ASD vs. TD | AUC = 0.879±0.057, Specificity = 0.853±0.108 | [37] |

| Genetic | De novo mutations | Associated with lower IQ and higher epilepsy rates | Distinct subtype with more severe presentation | [35] |

| Sensory | AASP scores | Elevated Avoidance, Low Registration, Sensitivity | Significant group differences (p<0.0001) | [14] |

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Integrative Approaches

| Approach | Data Types Integrated | Analytical Method | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging-Epigenetic | rs-fMRI, structural MRI, DNA methylation | XGBoost machine learning | Accounts for brain-epigenetic interactions | Requires large sample sizes |

| Genomic-ML | Gene expression, SNPs | SHAP explainable AI | Identifies key genetic features | Limited to known genetic variants |

| Proteomic-ML | Serum protein levels | SOMAScan assay + ML | High predictive accuracy | Need for independent validation |

| Motor-Digital | Wearable sensor data, clinical assessment | Digital phenotyping | Objective, continuous measurement | Emerging technology, less standardized |

Experimental Protocols for Integrative Biomarker Discovery

Protocol: Multi-Modal Data Collection for Neuroimaging-Epigenetic Integration

This protocol outlines procedures for collecting matched neuroimaging and epigenetic data for integrative biomarker discovery [14].

Materials:

- 3T MRI scanner with phased-array head coil

- DNA collection kits (saliva or blood)

- Sensory and behavioral assessment tools (AASP, ADOS-2, IQ measures)

- Data management system for multi-modal data linkage

Procedure:

- Participant Characterization:

- Confirm ASD diagnosis using DSM-5 criteria and ADOS-2

- Assess full-scale IQ using Wechsler Intelligence Scales

- Administer Adolescent-Adult Sensory Profile (AASP) questionnaire

- Screen for exclusion criteria (brain injury, major physical illness, substance abuse)

DNA Collection and Methylation Analysis:

- Collect saliva samples using standardized kits

- Extract DNA following manufacturer protocols

- Perform bisulfite conversion on extracted DNA

- Analyze methylation of candidate genes (OXTR, AVPR1A, AVPR1B) using targeted approaches or epigenome-wide arrays

- Normalize methylation data using standard bioinformatics pipelines

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition:

- Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted structural images (parameters: TR=6.38ms, TE=1.99ms, FA=11°, FoV=256mm, voxel size=1×1×1mm³)

- Collect resting-state fMRI using T2*-weighted gradient-echo EPI sequence

- Implement quality control procedures during acquisition

Data Integration and Analysis:

- Preprocess structural images (segmentation, normalization)

- Process functional data (slice-time correction, motion correction, normalization, smoothing)

- Extract thalamo-cortical functional connectivity measures

- Combine neuroimaging and epigenetic features in XGBoost model with sensory behavior as baseline

- Validate model performance using cross-validation

Troubleshooting:

- Motion artifacts in fMRI: Implement rigorous motion correction and consider framewise exclusion

- Batch effects in epigenetic data: Include control samples across batches and apply correction methods

- Missing data: Use multiple imputation techniques appropriate for the data type

Protocol: Serum Proteomic Biomarker Panel Identification

This protocol details the process for identifying serum protein biomarkers for ASD using proteomic analysis [37].

Materials:

- Serum collection tubes (SST)

- SomaLogic SOMAScan assay 1.3K platform

- Clinical assessment tools (ADOS-2, ABAS-II)

- Statistical software (R, Python) with machine learning libraries

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment and Characterization:

- Recruit age-matched ASD and typically developing (TD) participants (male-only or include sex as biological variable)

- Establish ASD diagnosis with ADOS-2 and clinical judgment

- Exclude participants with genetic, metabolic, or other concurrent physical/neurological disorders

- Collect demographic and clinical data (age, ethnicity, comorbidities, medication use)

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect blood samples following standard phlebotomy procedures

- Allow blood to clot for 30 minutes at room temperature

- Centrifuge at 1,000-2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Aliquot serum and store at -80°C until analysis

- Avoid freeze-thaw cycles

Proteomic Analysis:

- Process serum samples using SomaLogic SOMAScan platform

- Measure 1,125 proteins simultaneously using aptamer-based technology

- Follow standard hybridization, washing, and elution procedures

- Normalize data using adaptive normalization by maximum likelihood

Statistical Analysis and Biomarker Identification:

- Perform differential expression analysis (ASD vs. TD) with false discovery rate correction

- Apply multiple machine learning algorithms (random forest, support vector machines, logistic regression)

- Identify optimal protein panel through feature selection methods

- Validate panel using cross-validation and calculate AUC, sensitivity, specificity

- Correlate protein levels with ADOS severity scores (ASD group only)

Troubleshooting:

- High background signal: Check reagent quality and washing steps

- Batch effects: Randomize samples across processing batches

- Overfitting: Use appropriate cross-validation and independent test sets

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Multi-Modal Data Integration Workflow for ASD Biomarker Discovery

Diagram 2: Modeling Approaches for ASD Heterogeneity

Research Reagent Solutions for Integrative Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Multi-Modal ASD Biomarker Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Application in ASD Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic/Epigenetic | DNA methylation arrays (Illumina EPIC) | Genome-wide methylation analysis | Coverage of >850,000 CpG sites |

| Targeted bisulfite sequencing kits | Candidate gene methylation analysis | High sensitivity for specific loci | |

| Proteomic | SomaLogic SOMAScan platform | Multiplexed protein biomarker discovery | Simultaneous measurement of 1,100+ proteins |

| Multiplex immunoassays (Luminex) | Cytokine/chemokine profiling | Quantification of immune markers | |

| Neuroimaging | 3T MRI with high-resolution capabilities | Structural and functional brain imaging | Submillimeter resolution for cortical features |

| Resting-state fMRI sequences | Functional connectivity analysis | Identifies network-level alterations | |

| Behavioral | ADOS-2 | Diagnostic confirmation and severity assessment | Gold-standard diagnostic tool |

| Adolescent-Adult Sensory Profile | Sensory processing characterization | Measures four sensory patterns | |

| Data Integration | XGBoost algorithm | Multi-modal data integration | Handles mixed data types, provides feature importance |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretability | Quantifies feature contribution to predictions |

Overcoming reductionism in autism biomarker research requires systematic approaches that embrace rather than control for heterogeneity. By implementing the protocols, troubleshooting guides, and integrative frameworks provided in this technical support resource, researchers can advance toward person-centered biomarker discovery that respects the multifaceted nature of autism. The future of ASD research lies in developing biomarkers that not only improve early detection but also guide personalized intervention strategies matched to individual biological and behavioral profiles.