Decoding Disease Endotypes: A Systems Biology Approach to Precision Medicine

The paradigm of 'one-size-fits-all' medicine is rapidly giving way to precision medicine, necessitating a deeper understanding of disease heterogeneity.

Decoding Disease Endotypes: A Systems Biology Approach to Precision Medicine

Abstract

The paradigm of 'one-size-fits-all' medicine is rapidly giving way to precision medicine, necessitating a deeper understanding of disease heterogeneity. This article explores how systems biology, through the integration of multi-omics data, computational modeling, and machine learning, enables the identification of disease endotypes—subtypes defined by distinct biological mechanisms. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational concepts distinguishing phenotypes from endotypes, detail methodological workflows from data generation to analytical pipelines, address key challenges in data integration and biomarker validation, and evaluate the clinical impact of this approach through comparative studies. The synthesis of these elements provides a comprehensive framework for developing targeted, effective therapies and advancing personalized patient care.

From Phenotypes to Precision: Unraveling the Core Concepts of Disease Endotypes

In the era of precision medicine, the historical approach of classifying complex diseases based solely on collective symptoms is proving insufficient. Diseases such as asthma, COPD, and atopic dermatitis are now recognized as heterogeneous disorders encompassing multiple distinct biological entities beneath a common clinical facade [1] [2]. This paradigm shift necessitates a new taxonomic framework that moves beyond descriptive symptomatology to embrace mechanistic underpinnings. The evolving landscape of disease classification now integrates phenotypes (observable characteristics) with endotypes (distinct biological mechanisms), facilitated by advances in systems biology and multi-omics technologies [1]. This whitepaper delineates the critical distinctions between phenotypes and endotypes, establishes methodologies for endotype discovery, and frames this classification within a systems biology research context essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to develop targeted therapeutic strategies.

Conceptual Foundations: Phenotype, Endotype, and the Bridging Biomarker

Phenotype: The Observable Clinical Presentation

A phenotype refers to the collection of observable clinical characteristics, including symptoms, exacerbation frequency, physiological parameters, and imaging patterns that can be identified through routine clinical assessment [1]. Phenotypes are defined by their direct correlation with clinically relevant outcomes such as treatment responses, disease progression rates, and mortality. For example, in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), well-established clinical phenotypes include the "frequent-exacerbator" and "emphysema-dominant" subtypes [1]. These classifications are valuable for prognostic stratification and initial therapeutic guidance but do not inherently reveal the underlying biological pathways responsible for the clinical presentation.

Endotype: The Underlying Biological Mechanism

An endotype represents a distinct disease subcategory defined by a unique functional or pathobiological mechanism [1]. Unlike phenotypes, endotypes are characterized by specific biochemical pathways, molecular mechanisms, or genetic underpinnings that are conceptually independent of the observable clinical features. The identification of an endotype typically requires specialized molecular profiling and is validated by its ability to predict response to a targeted therapy. Key examples include:

- Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma and COPD [1]

- α1-antitrypsin deficiency in COPD [1]

- Neutrophilic airway inflammation in severe respiratory disease

Critically, a single phenotype can arise from multiple distinct endotypes [1]. For instance, the "frequent-exacerbator" phenotype in COPD may result from an eosinophilic inflammation-driven endotype, which would respond well to corticosteroids, or from an infection-dominated endotype, which might require different therapeutic management [1]. This distinction explains why patients with similar clinical presentations may demonstrate markedly different responses to the same treatment.

Biomarkers: The Operational Bridge

Biomarkers serve as the crucial operational link between phenotypes and endotypes, providing measurable indicators of biological processes [1] [2]. They enable the translation of mechanistic understanding into clinically applicable tools for patient stratification and treatment selection. Promising biomarkers in respiratory disease and dermatology include:

- Blood eosinophil counts for identifying Th2-high inflammation [1]

- Sputum transcriptomics for airway inflammation profiling [1]

- Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) for systemic inflammation assessment [1]

- Specific IgE and other molecular signatures in atopic dermatitis [2]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Phenotypes and Endotypes

| Feature | Phenotype | Endotype |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Observable clinical characteristics and disease manifestations | Subtype defined by distinct biological mechanisms |

| Basis | Clinical features, imaging, physiological tests | Molecular pathways, genetic factors, specific biomarkers |

| Identification Method | Clinical observation, standard diagnostics | Molecular profiling, multi-omics technologies |

| Primary Utility | Prognostication, initial treatment grouping | Predicting response to targeted therapies |

| Example in COPD | "Frequent-exacerbator," "Emphysema-dominant" | Eosinophilic inflammation, α1-antitrypsin deficiency |

| Relationship | One phenotype can map to multiple endotypes | One endotype may manifest as different phenotypes |

The Systems Biology Framework for Endotype Discovery

From Reductionism to Integration: The Systems Approach

Systems biology represents a fundamental paradigm shift from reductionist approaches to an integrative framework that examines complex interactions within biological systems [3]. This approach is particularly suited for endotype discovery because it acknowledges that complex diseases emerge from dynamic networks of molecular and environmental interactions rather than single pathway disruptions. The emerging field of "systems quantitative genetics" exemplifies this transition, extending beyond DNA sequence variations to integrate contributions from multiple biological layers including epigenetics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [3].

This integrative framework enables researchers to address the fundamental challenge in complex disease taxonomy: the lack of complete congruence between genetic polymorphisms and phenotypic manifestations [3]. By capturing the interplay between various molecular layers, systems biology provides the methodological foundation for delineating mechanistically distinct endotypes that transcend superficial phenotypic classification.

Methodological Framework: A Decision Tree Approach for Endotype Identification

A robust data-driven methodology for endotype discovery has been demonstrated through a multi-step decision tree-based approach that integrates gene expression data with clinical and demographic covariates [4] [5]. This method was developed specifically to identify novel, mechanistically distinct disease subtypes from large, multi-dimensional datasets and has been successfully applied to childhood asthma as a case study [5].

The decision tree method outperformed alternative approaches including Student's t-test, single-data domain clustering, and the Modk-prototypes algorithm in its ability to segregate asthmatics from non-asthmatics while providing accessible biological interpretation of the distinguishing features [5]. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to handle the complexity of multi-factorial diseases without relying exclusively on pre-established clinical criteria, thereby enabling discovery of previously unrecognized disease mechanisms [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Endotype Discovery

| Research Reagent | Function in Endotyping | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Microarrays | Genome-wide transcriptional profiling | Identifying expression signatures in blood or target tissues [5] |

| Peripheral Blood Samples | Surrogate for target tissue analysis | Evaluating gene expression relevant to disease mechanisms [5] |

| Protein Assays (CRP, IgE) | Quantifying inflammatory biomarkers | Stratifying patients by inflammatory endotypes [1] [5] |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | Immune cell population analysis | Differentiating inflammatory cell patterns (e.g., eosinophil vs. neutrophil) [1] |

| Multi-omics Platforms | Integrated molecular profiling | Revealing interactions across genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic layers [3] |

Experimental Workflow for Endotype Discovery

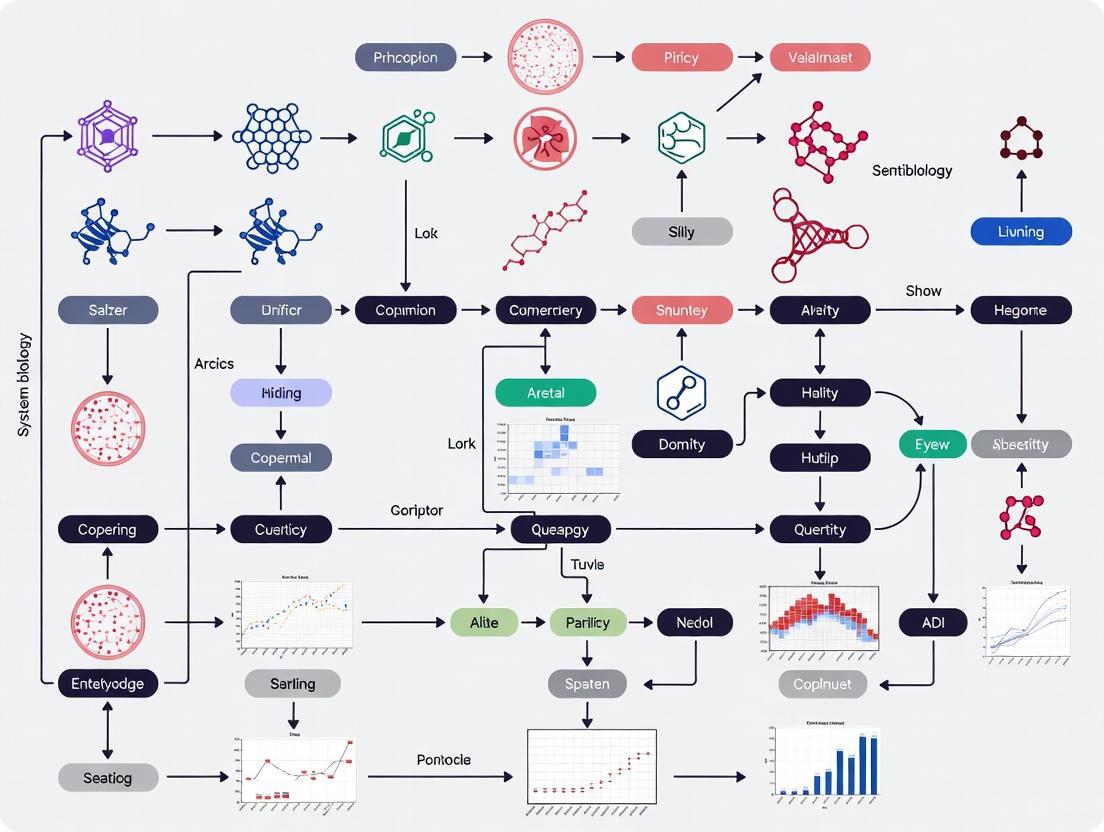

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for identifying disease endotypes through integrated data analysis:

Systematic Workflow for Endotype Discovery

Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Data in Parameter Identification

Systems biology models for endotype characterization benefit from incorporating both qualitative and quantitative data in parameter identification [6]. This approach formalizes qualitative biological observations as inequality constraints on model outputs, which are combined with quantitative measurements through constrained optimization techniques [6]. The objective function in such analyses typically takes the form:

f_tot(x) = f_quant(x) + f_qual(x)

where f_quant(x) represents the sum of squares distance from quantitative data points, and f_qual(x) represents penalty terms for violation of qualitative constraints derived from biological observations [6]. This methodology has been successfully applied to models of Raf inhibition and yeast cell cycle regulation, demonstrating that combining both data types leads to higher confidence in parameter estimates than either dataset could provide individually [6].

Case Studies in Disease Endotyping

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD exemplifies disease heterogeneity with distinct phenotypic classifications including "emphysema-dominant" (Type A, "pink puffer") and "chronic bronchitis" (Type B, "blue bloater") presentations [1]. The 2023 GOLD guidelines further recognize etiologic heterogeneity by introducing "etiotypes" - causal subtypes including genetically determined COPD (COPD-G), biomass exposure COPD (COPD-P), and COPD with asthma (COPD-A) [1].

Emerging endotypic classifications focus on biological mechanisms rather than clinical presentations:

- Eosinophilic endotype: Characterized by elevated blood or sputum eosinophils, associated with better response to corticosteroids [1]

- Neutrophilic endotype: Dominated by neutrophil-mediated inflammation, often less responsive to standard therapies [1]

- α1-antitrypsin deficiency endotype: Defined by specific genetic abnormality with distinct pathogenesis [1]

These endotypes demonstrate superior predictive value for therapeutic responses compared to phenotypic classification alone, underscoring their clinical utility [1].

Asthma and Atopic Dermatitis

In childhood asthma, the decision tree approach to endotype discovery successfully segregated asthmatics from non-asthmatics by integrating gene expression data from peripheral blood with clinical covariates including allergen sensitivity tests, total serum IgE, and white blood cell differential counts [5]. This methodology provided not only effective classification but also biological interpretation of the distinguishing mechanisms.

Similarly, in atopic dermatitis, research focuses on identifying biomarkers that define endophenotypes to move beyond the historical approach of grouping diverse clinical variants without considering their heterogeneity [2]. These efforts aim to develop phenotype- and endotype-adapted therapeutic strategies tailored to the specific biological mechanisms driving disease in individual patients [2].

Methodological Protocols for Endotype Research

Protocol 1: Decision Tree Analysis for Endotype Identification

This protocol outlines the multi-step decision tree method for identifying endotypes from integrated genomic and clinical data [5]:

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect gene expression data from appropriate tissue (e.g., peripheral blood, target tissue)

- Assemble clinical covariates including demographic, physiological, and biochemical measurements

- Include disease status indicators for supervised analysis

- Normalize and standardize all data domains

Integrated Analysis

- Apply decision tree classification using all available data domains

- Identify key splitting variables that best segregate disease subgroups

- Validate tree structure through cross-validation techniques

- Compare performance against alternative methods (e.g., clustering, t-tests)

Biological Interpretation

- Extract genes and clinical covariates that distinguish the groups

- Perform pathway analysis on distinguishing genes

- Relate findings to known biological mechanisms

- Generate hypotheses for novel disease mechanisms

Protocol 2: Quantitative Morphological Cell Phenotyping

Quantitative morphological phenotyping (QMP) provides a method for capturing morphological features at cellular and population levels [7]. The systematic workflow includes:

Image Acquisition and Processing

- High-content imaging of cellular populations

- Image preprocessing and quality control

- Cell segmentation and feature extraction

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Multivariate analysis of morphological features

- Identification of morphological signatures associated with disease states

- Integration with molecular data for multi-scale profiling

This approach enables leveraging subtle cellular morphological changes for precise disease subclassification and has been applied to yeast mutant collections among other model systems [7].

The distinction between phenotypes and endotypes represents a fundamental advancement in disease taxonomy that aligns with the core principles of precision medicine. This approach acknowledges that complex diseases are often umbrella terms encompassing multiple mechanistically distinct disorders [1]. The integration of systems biology methodologies, multi-omics technologies, and data-driven classification approaches enables researchers to move beyond descriptive symptomatology to mechanistic disease understanding.

For drug development professionals, this paradigm offers the potential to design more targeted therapies with higher likelihood of success in specific patient subpopulations. The "treatable traits" framework operationalizes this approach by addressing modifiable factors beyond conventional disease classifications [1]. Future directions in the field include early detection of pre-disease states, integration of dynamic phenotyping through machine learning, and pragmatic clinical trials evaluating precision-guided interventions [1].

As systems biology continues to evolve, the integration of multi-scale data from genomics to clinical manifestations will further refine our ability to identify clinically meaningful endotypes. This progression from reactive, symptom-based medicine to proactive, mechanism-targeted therapeutic paradigms holds promise for transforming the management of complex diseases across medical specialties.

In the pursuit of precision medicine, the clinical classification of diseases based solely on observable symptoms—the phenotype—has proven insufficient for predicting treatment outcomes and understanding underlying disease mechanisms. Systems biology research has introduced the crucial concept of the endotype, defined as a distinct biological subtype of a disease characterized by a specific functional or pathophysiological mechanism [8]. Unlike phenotypes, which describe what a disease looks like, endotypes explain why the disease manifests and progresses in a particular way, driven by distinct molecular pathways that can be targeted therapeutically [9] [8]. This paradigm shift is transforming drug development by enabling patient stratification based on molecular mechanisms rather than clinical presentation alone, thereby addressing the critical challenge of heterogeneity in treatment response across patient populations.

Defining the Endotype Concept: Molecular Drivers of Disease Heterogeneity

The endotype concept represents a fundamental advancement in disease classification. Endotypes are characterized by specific immunological, inflammatory, metabolic, and remodeling pathways that explain the mechanisms underlying a disease's clinical presentation [8]. This mechanistic understanding enables researchers to move beyond descriptive categorizations toward biologically meaningful disease subdivisions.

Several key features distinguish endotypes from traditional disease classifications:

- Mechanistic Basis: Endotypes are defined by specific molecular pathways and pathological processes [8] [10]

- Stability: Unlike fluctuating clinical symptoms, endotypes typically represent stable biological traits

- Predictive Value: Endotype classification can forecast disease progression, complication risks, and treatment responses [11]

- Therapeutic Relevance: Endotypes often align with specific therapeutic targets, enabling personalized treatment approaches [10]

The relationship between phenotypes and endotypes is complex and multidimensional. A single clinical phenotype may encompass multiple distinct endotypes, while a single endotype might manifest through varied phenotypic expressions across different patients [12]. This complexity underscores the necessity of molecular profiling for accurate endotype identification.

Disease Case Studies: Endotype Identification and Clinical Impact

Sepsis: Molecular Endotypes Predict Mortality

A comprehensive multi-cohort study analyzing host gene expression profiles from 494 sepsis patients across global populations identified four distinct molecular endotypes with significant mortality implications [13].

Table 1: Sepsis Endotypes Identified by Host Gene Expression Profiling

| Endotype | 28-Day Mortality | Defining Molecular Features | Clinical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompetent | Low | Adaptive immune system activation; robust T-cell and B-cell signaling | Favorable prognosis; minimal organ dysfunction |

| Immunosuppressed | High | Dysfunctional immune response; impaired host defense pathways | High susceptibility to secondary infections |

| Acute-Inflammation | High | Innate immune system hyperactivation; pronounced inflammatory signaling | Severe multiple organ dysfunction; systemic inflammation |

| Immunometabolic | High | Metabolic pathway dysregulation (e.g., heme biosynthesis) | Significant metabolic disturbances alongside organ failure |

This endotypic classification provides a framework for developing tailored immunotherapeutic interventions and biomarkers for predicting outcomes in specific sepsis subgroups [13].

Atopic Dermatitis: Proteomic Profiling Reveals Inflammatory Subtypes

Research on moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) has identified distinct molecular endotypes through comprehensive serum proteomic analysis. Using k-means clustering of 1,248 serum protein analytes, researchers consistently identified two stable patient clusters characterized by high (ADHI) and low (ADLO) inflammatory profiles [11].

The AD_HI endotype demonstrated upregulation of both canonical AD inflammatory mediators (including IL-13, IL-19, TARC, and CCL27) and proteins not typically associated with AD, suggesting novel axes of dysregulation. These proteomic signatures were correlated with skin-based disease severity scores, confirming their clinical relevance [11]. The stability of these clusters was validated through rigorous reproducibility testing, including analyses with and without healthy control data.

Neutrophilic Asthma: Distinct Mechanism and Therapeutic Target

Neutrophilic asthma constitutes a distinct endotype characterized by neutrophil-dominated airway inflammation and resistance to corticosteroids [10]. Research has identified Milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 (MFGE8) as a key regulator in this endotype. MFGE8 protein levels are significantly reduced in the sputum supernatant of patients with neutrophilic asthma, and mechanistic studies reveal that MFGE8 inhibits the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETosis) through interaction with integrin β3 [10].

This endotype-specific mechanism presents a promising therapeutic target. Experimental models demonstrate that recombinant MFGE8 protein effectively mitigates neutrophilic airway inflammation, suggesting potential for targeted therapy in this treatment-resistant asthma population [10].

Sjögren's Disease: Heterogeneity in Autoimmunity

Sjögren's disease exemplifies the challenges posed by patient heterogeneity in autoimmune conditions. Molecular stratification studies have identified three to four distinct patient subgroups, potentially representing different disease endotypes or stages [12]. The most consistently identified molecular signature across Sjögren's patients is interferon pathway activation, observed in more than half of patients [12].

Table 2: Stratification Approaches in Sjögren's Disease

| Stratification Method | Basis of Classification | Identified Subgroups | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Symptom-Based | Patient-reported symptoms followed by biomarker analysis | 3-4 clinical clusters (e.g., low symptom burden, high systemic activity) | Tailored symptomatic management |

| Molecular Pattern-Driven | Multi-omics profiling of whole blood samples | Inflammatory, lymphoid, interferon, and undefined molecular subgroups | Targeted immunomodulatory approaches |

| Serological Profile-Based | Autoantibody patterns and inflammatory markers | Subgroups with distinct autoantibody specificities | Predictors of extraglandular manifestations and lymphoma risk |

The ongoing debate about whether these subgroups represent true endotypes or disease stages highlights the dynamic nature of endotype discovery and validation [12].

Experimental Methodologies for Endotype Identification

Proteomic Profiling Workflow

The identification of atopic dermatitis endotypes exemplifies a rigorous proteomic approach [11]:

This workflow yielded 1,248 protein analytes for cluster analysis, with stability assessed through multiple validation approaches including bootstrapping methods and comparison of clustering outcomes with and without healthy control data [11].

Transcriptomic Analysis in Sepsis

The sepsis endotype study employed sophisticated transcriptomic methodologies [13]:

- RNA Sequencing: Peripheral blood RNA was collected in PAXgene RNA tubes, with ribosomal and globin RNA depletion to enhance sensitivity.

- Bioinformatic Processing: Sequencing reads were aligned to the human genome (GRCh38) using Hisat2, and transcripts were assembled using Stringtie.

- Data Normalization: Raw read counts were normalized using Median Ratio Normalization with Variance Stabilizing Transformation, yielding 3,061 genes for analysis.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Multiple approaches including Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), and Topological Data Analysis (TDA) identified patient subgroups with similar gene expression profiles.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Welch two-sample t-test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction identified significantly differentially expressed genes between endotypes.

- Pathway Analysis: Gene set enrichment analysis against Hallmark pathways revealed the biological processes distinguishing each endotype.

Systems Immunology Approaches

For recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB), systems immunology approaches using single-cell high-dimensional techniques captured the signature of peripheral immune cells and metabolic profile diversity [8]. Artificial intelligence prediction models and principal component analysis characterized the complex systemic endotypes marked by immune dysregulation and hyperinflammation, laying the groundwork for translational interventions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Endotype Discovery

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Endotype Identification

| Research Tool | Specific Application | Function in Endotype Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Olink Explore 1536 Assay [11] | High-throughput proteomics | Simultaneously measures 1,248 protein biomarkers in serum samples |

| PAXgene Blood RNA System [13] | RNA stabilization from blood | Preserves transcriptomic profiles for gene expression analysis |

| Single-cell RNA Sequencing [8] | High-dimensional immune profiling | Captures diversity of immune cell populations and states |

| Globin-Zero Gold rRNA Removal Kit [13] | RNA library preparation | Depletes ribosomal and globin RNA to enhance sensitivity |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis [11] | Bioinformatics analysis | Identifies modules of highly correlated genes and their associations |

| Topological Data Analysis [13] | Dimensionality reduction | Groups participants with similar gene expression profiles unbiasedly |

Discussion: Implications for Drug Development and Clinical Trial Design

The integration of endotype-based classification into drug development represents a paradigm shift with far-reaching implications. By enabling patient stratification according to underlying molecular mechanisms rather than symptomatic manifestations, endotype discovery directly addresses the challenge of treatment response heterogeneity that has plagued many clinical trials [12] [11].

The practical applications of endotyping in pharmaceutical development include:

- Enrichment Strategies: Selecting patient populations most likely to respond to targeted therapies

- Biomarker Development: Identifying companion diagnostics for treatment selection

- Clinical Trial Design: Structuring trials based on molecular subgroups rather than broad diagnostic categories

- Combination Therapies: Rational pairing of treatments targeting different mechanisms in complex diseases

- Clinical Practice: Ultimately enabling treatment decisions based on molecular profiling rather than trial-and-error approaches

As integrative omics technologies continue to advance, together with computational methods for analyzing high-dimensional data, the framework for identifying and validating disease endotypes will become increasingly sophisticated [14]. This progress promises to accelerate the development of personalized therapeutic strategies tailored to the specific molecular drivers of disease in individual patients, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine.

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from a reductionist study of individual components to a holistic, integrative analysis of complex systems. This approach is paramount for deciphering the intricate mechanisms of human disease, particularly through the lens of endotypes—subclassifications of disease defined by distinct functional or pathobiological mechanisms [15]. Unlike phenotypes, which are observable characteristics tied to clinical outcomes, endotypes delineate the underlying biological drivers that explain why a particular phenotype manifests [15]. The identification of endotypes is crucial for advancing precision medicine, as it enables the move from symptomatic treatments to therapies targeted at specific pathological mechanisms. Systems biology serves as the primary engine for endotype discovery by integrating multi-omics data, computational modeling, and high-throughput experiments to unravel the complex, dynamic interactions within biological systems [16] [17].

The Core Methodologies of Systems Biology

Systems biology employs a diverse toolkit of computational and experimental methods to generate and validate hypotheses about biological function. These methodologies are interdependent, forming an iterative cycle of prediction and experimentation.

Mathematical Modeling and Simulation

Mathematical modeling is a key tool in systems biology used to determine the mechanisms by which elements of biological systems interact to produce complex dynamic behavior [18]. By conducting computational experiments that simulate these systems, researchers can gain valuable insights into the mechanisms governing dynamic behavior that are difficult to understand by intuitive reasoning alone [18] [19].

- Model Types and Applications: The field utilizes various model frameworks, including:

- Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs): Used to model the dynamics of biological systems over time, such as signaling pathways and metabolic networks. For instance, ODEs can model the cGAS-STING signaling pathway to understand its dual role in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) promotion and inhibition [19].

- Stochastic Models: Account for random fluctuations in biological processes, such as radiation-induced DNA damage kinetics, where outcomes can deviate from deterministic predictions due to clustering of damage events [18].

- Constraint-Based Models: Leverage genomic information to predict metabolic fluxes in genome-scale metabolic networks.

- Parameter Estimation and Identifiability: A critical step in model development is parameter estimation, ensuring models are calibrated to real-world data. Practical identifiability analysis assesses whether model parameters can be uniquely determined from noisy, experimental data [20]. Advanced computational frameworks, such as the VeVaPy Python library, aid in model verification and validation by running parameter optimization algorithms and ranking models based on their fit to experimental data [18].

Data Integration and Multi-Omic Analysis

The rise of high-throughput technologies has enabled the comprehensive profiling of biological systems across multiple layers, from genomics and transcriptomics to proteomics and metabolomics. Systems biology provides the analytical framework to integrate these disparate data types.

- Tools for Discovery: Computational tools are essential for extracting meaningful biological signals from complex omics datasets. For example, ProstaMine is a systems biology tool designed to systematically identify co-alterations of genes associated with aggressiveness in prostate cancer. It integrates multi-omics and clinical data to prioritize co-alterations enriched in metastatic disease, uncovering subtype-specific mechanisms of progression [16].

- Single-Cell Technologies: Advanced techniques like mass cytometry (CyTOF) and imaging mass cytometry (IMC) allow for deep, high-dimensional immunophenotyping at the single-cell level. These methods can capture the diversity of immune cell populations and their functional states in patient samples, revealing endotype-specific immune signatures [17].

Table 1: Key Analytical Techniques in Systems Biology

| Technique | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Reduces data dimensionality to reveal underlying patterns. | Used in cGAS-STING model analysis and to stress systemic immune dysregulation in RDEB [17] [19]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Quantifies how model output is affected by variations in parameters. | Identifies key regulatory parameters in mathematical models of signaling pathways [20] [19]. |

| Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) | Non-linear dimensionality reduction for visualization of high-dimensional data. | Mapping single-cell CyTOF data to identify distinct immune cell clusters in RDEB patients [17]. |

| PhenoGraph | Algorithm for clustering high-dimensional single-cell data. | Automated annotation of immune cell populations from CyTOF and IMC data [17]. |

Case Study: Uncovering Endotypes in Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa (RDEB)

Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa (RDEB), a severe blistering disease caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, serves as a powerful example of how systems immunology can reveal complex systemic endotypes.

Experimental Workflow and Findings

A systems immunology approach was applied to RDEB adults, using single-cell high-dimensional techniques to capture the signature of peripheral immune cells and the diversity of metabolic profiles [17]. The workflow involved:

- Comprehensive Immune Profiling: Peripheral blood leukocytes were analyzed using CyTOF with a large panel of lineage-specific metal-tagged antibodies. Dimensionality reduction with UMAP and clustering with PhenoGraph revealed substantial differences in major innate and adaptive immune cell populations in RDEB adults compared to healthy controls [17].

- Tissue Validation: Imaging mass cytometry (IMC) was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded skin biopsies from RDEB patients, confirming elevated infiltrates of various CD45+ immune cell populations in skin lesions [17].

- In-Depth PBMC Analysis: Further profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) identified increased frequencies of effector and central memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets, as well as CD14+CD16+ intermediate monocytes in RDEB adults [17].

- Metabolic Profiling: Large-scale profiling of energy and lipid metabolism was conducted, revealing a pro-inflammatory lipid signature concomitant with the immune findings [17].

Identified Endotype and Implications

The study demonstrated that RDEB is not solely a skin disorder but has complex systemic endotypes marked by immune dysregulation and hyperinflammation. The specific endotype was characterized by activated/effector T cell signatures, dysfunctional natural killer (NK) cell signatures, and an overall pro-inflammatory lipid signature [17]. Artificial intelligence prediction models and principal component analysis confirmed these findings, laying the groundwork for translational interventions aimed at lessening inflammation to alleviate patient suffering [17].

Systems Immunology Workflow for RDEB Endotype Discovery

Experimental Protocols for Model-Informed Discovery

Protocol: Minimally Sufficient Experimental Design Using Identifiability Analysis

A critical challenge in model-informed discovery is designing experiments that yield the most informative data for model parametrization without being prohibitively costly or time-consuming. The following protocol uses practical identifiability analysis to determine a minimally sufficient experimental design [20].

- Variable and Model Selection: Identify the experiment that measures the variable of interest (e.g., percent target occupancy in a tumor). Develop, parameterize, and validate a mathematical model describing the system [20].

- Parameter Selection: Select parameters of interest for analysis by first removing those that are easily measurable experimentally. Then, perform a local sensitivity analysis to identify the most sensitive parameters for fitting the data of interest [20].

- Profile Likelihood Analysis: Use the profile likelihood method to assess the practical identifiability of parameters given different hypothetical experimental datasets. This involves determining if parameters can be uniquely estimated from noisy data [20].

- Design Optimization: Iteratively test different experimental sampling schedules (e.g., time points for measurement) to find the minimal set that ensures all parameters of interest are practically identifiable. The goal is to find the protocol that robustly ensures identifiability while minimizing experimental burden [20].

Protocol: Reconstructing a Signaling Pathway Model with MATLAB

To understand complex pathways like cGAS-STING in NSCLC, a mathematical model can be reconstructed and analyzed using computational tools [19].

- Model Reconstruction:

- Launch MATLAB and open the SimBiology toolbox.

- In the diagram editor, create compartments representing cellular structures (e.g., plasma membrane, cytoplasm, nucleus).

- Drag and drop "Species" into the compartments to represent signaling intermediates, receptors, and transcription factors.

- Connect species via "Reactions" to form the network. Define reaction kinetics:

- For association, dissociation, and translocation, use the law of mass action (define rate constant

kf). - For enzyme kinetics (e.g., phosphorylation), use Michaelis-Menten kinetics (define

VmaxandKm). - For gene expression, use Hill's kinetics (define

Vmax,Km, and Hill coefficientn).

- For association, dissociation, and translocation, use the law of mass action (define rate constant

- Set initial concentrations of species in the range of 10³–10⁶ molecules [19].

- Model Simulation and Analysis:

- Simulate the model to observe system dynamics over time.

- Perform a local sensitivity analysis to determine which parameters most influence model outputs.

- Conduct principal component analysis to understand parameter interdependence.

- Apply model reduction techniques to simplify the model while retaining critical dynamics [19].

Iterative Cycle of Model Development and Validation

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Studies

| Item / Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-tagged Antibody Panels | Enable high-dimensional, single-cell protein analysis via mass cytometry (CyTOF). | Comprehensive immunophenotyping of peripheral blood leukocytes in RDEB studies [17]. |

| Illumina Global Screening Array (GSA) | A cost-effective, array-based platform for large-scale genotyping. | Used in pharmacogenomics testing workflows to identify clinically actionable genetic variants [16]. |

| MATLAB with SimBiology Toolbox | Provides a platform for modeling, simulating, and analyzing dynamic systems; supports SBML format. | Reconstruction and simulation of ODE-based models, such as the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in NSCLC [19]. |

| VeVaPy Python Library | A computational framework for the verification and validation of systems biology models. | Used to optimize parameters and rank competing models of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis against novel datasets [18]. |

| COPASI | Software application for simulation and analysis of biochemical networks and their dynamics. | An alternative platform for model simulation and analysis [19]. |

Systems biology, through its integrative and hypothesis-driven approach, is the indispensable engine for discovery in modern biomedical research. By leveraging mathematical modeling, multi-omics data integration, and advanced computational tools, it provides the methodological foundation to move beyond superficial phenotypes and uncover the mechanistic endotypes that drive disease. This high-level overview has detailed the core methodologies, showcased a practical application in disease endotyping, and provided actionable experimental protocols. As these approaches continue to mature, they will profoundly accelerate the development of targeted, effective therapeutics, ultimately realizing the promise of precision medicine.

The field of clinical medicine is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a syndrome-based classification of disease toward a mechanism-driven framework centered on the concept of endotypes. An endotype represents a distinct biological subtype of a disease, defined by specific molecular mechanisms, genetic underpinnings, and pathophysiological pathways that differ from other subtypes within the same clinical syndrome [21]. This precision medicine approach is particularly crucial for complex, heterogeneous conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and allergic diseases, where significant variability in clinical presentation, disease progression, and treatment response has long complicated management and drug development [1].

The identification of disease endotypes represents a cornerstone of modern systems biology research, which seeks to integrate multi-dimensional data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to define coherent biological networks underlying disease manifestations [21]. This approach recognizes that different pathological mechanisms can converge on similar clinical presentations, while the same treatment may yield dramatically different outcomes across patient subgroups. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and targeting specific endotypes offers the promise of more effective therapies with improved safety profiles, moving beyond the traditional one-size-fits-all approach that has dominated respiratory and allergy therapeutics [1].

Asthma Endotypes: From T2 Inflammation to Epithelial Dysfunction

Molecular Classification of Asthma Heterogeneity

Asthma has been traditionally classified using observable characteristics or phenotypes, such as allergic asthma, nonallergic asthma, adult-onset asthma, and obesity-associated asthma [21]. However, these clinical categories often mask substantial underlying biological diversity. The application of omics technologies to sputum, bronchial epithelium, and blood has revealed that asthma consists of multiple molecular endotypes, broadly categorized as T2-high and non-T2 asthma, each with distinct mechanistic pathways [21].

Research has progressively refined this classification. Early work focused on T-helper (Th) cell pathways, but the discovery that innate immune cells like innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) can produce Th2-associated cytokines prompted a shift in terminology from "Th2" to "T2" inflammation [21]. Transcriptomic analyses of sputum cells have further delineated these endotypes. One pivotal study measuring cytokine expressions identified that 67% of asthmatics exhibited a T2-high pattern, characterized by significantly elevated levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which was associated with increased eosinophils and more severe, treatment-resistant disease requiring biologics [21].

Beyond the T2/non-T2 dichotomy, more sophisticated clustering approaches have revealed additional complexity. One analysis of sputum cytokine patterns identified five distinct clusters: (1) high IL-5, IL-10, IL-25, IL-17A, IL-17F; (2) high IL-5/IL-10 with normal IL-17F; (3) high IL-6; (4) high IL-22; and (5) normal cytokine levels [21]. These clusters demonstrated different inflammatory cell profiles, with clusters 1 and 5 showing higher sputum eosinophil percentages, while clusters 1 and 4 had more neutrophils.

The Emerging Role of Airway Epithelium in Asthma Pathogenesis

A paradigm shift in asthma research is the growing recognition that airway epithelial dysfunction may represent the primary driver of inflammatory cascades, marking the beginning of what researchers term the "epithelium era" in asthma investigation [21]. The airway epithelium consists of multiple cell types—including basal cells, club cells, ciliated cells, goblet cells, pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, tuft cells, and pulmonary ionocytes—connected by junctional complexes [21]. In health, this epithelium maintains homeostasis, defends against threats, and regulates immunity, but chronic barrier dysfunction can instigate and propagate excessive immune responses in asthma.

This epithelial paradigm suggests a potentially more straightforward therapeutic approach: targeting the initial epithelial defect rather than the multitude of downstream inflammatory genes affected by the disturbed airway epithelium [21]. Understanding the cellular composition and differentiation of the airway epithelium is now considered vital for developing treatments to restore airway integrity in established asthma.

Early-Life Determinants of Asthma Endotypes

Recent research has illuminated how early-life respiratory patterns influence the development of specific asthma endotypes later in life. A multi-cohort study analyzing data from 961 participants identified four distinct wheeze trajectories: Infrequent, Transient, Late-onset, and Persistent [22]. Each trajectory was associated with unique molecular signatures in upper airway transcriptomes during adolescence and early adulthood:

- Persistent wheezers exhibited elevated gene expression related to mast cell activation and T2 inflammation, but those who developed asthma showed upregulation of neuronal signaling and ciliary function genes rather than traditional T2 inflammation [22].

- Late-onset wheezers demonstrated decreased expression in pathways associated with insulin signaling and carbohydrate metabolism, suggesting a link between airway metabolic dysfunction and later-onset wheeze risk [22].

- Both late-onset and persistent wheeze displayed reduced expression of modules related to innate immune defense and interferon signaling, indicating potentially impaired antiviral and immune responses [22].

These findings suggest that asthma endotypes are shaped by early wheezing patterns, and that neuronal dysregulation and epithelial dysfunction—rather than allergic inflammation alone—may be central to sustained disease pathogenesis in high-risk children [22].

Table 1: Key Asthma Endotypes and Their Characteristics

| Endotype Category | Key Defining Features | Biomarkers | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2-high | Elevated type 2 inflammation | High IL-4, IL-5, IL-13; sputum/bood eosinophilia; elevated FeNO | Responsive to corticosteroids; anti-IL-4/IL-13, anti-IL-5 biologics |

| Non-T2 | Absence of T2 inflammation | Normal eosinophils; may show neutrophilic or paucigranulocytic inflammation | Poor response to corticosteroids; requires alternative approaches |

| Early-life persistent wheeze | Mast cell activation, neuronal signaling, epithelial dysfunction | T2 inflammation initially; later neuronal and ciliary genes | May benefit from non-T2 targeted interventions |

| Late-onset wheeze | Metabolic dysfunction, impaired innate immunity | Decreased insulin signaling and interferon pathways | Metabolic modulators? |

COPD Endotypes: Beyond the Smoker's Lung

Etiological Diversity in COPD

COPD has traditionally been conceptualized as a single disease entity primarily caused by smoking, but this perspective fails to capture the condition's substantial heterogeneity. The 2023 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report formally acknowledges this diversity by introducing a novel "etiotype" classification system that categorizes COPD based on predominant risk factors [1]. The seven identified etiotypes include:

- Genetically determined COPD (COPD-G) - including alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- COPD due to abnormal lung development (COPD-D) - resulting from early-life events

- Cigarette smoking COPD (COPD-C) - the traditional phenotype

- Biomass and pollution exposure COPD (COPD-P) - common in non-smokers, particularly women in developing countries

- COPD due to infections (COPD-I) - such as post-tuberculosis

- COPD with asthma (COPD-A) - the overlap syndrome

- COPD of unknown cause (COPD-U) [1]

This classification underscores that multiple pathogenic pathways can lead to the final common pathway of irreversible airflow limitation. For instance, biomass-associated COPD frequently manifests greater airway fibrosis with less emphysematous destruction compared to tobacco-related disease [1]. This etiological diversity has profound implications for both prevention strategies and targeted therapeutics.

Inflammatory Endotypes and Treatable Traits

Beyond etiology, COPD heterogeneity is evident at the biological level, particularly in the inflammatory patterns observed across patients. Emerging research emphasizes endotypes defined by distinct biological mechanisms, including neutrophilic inflammation, eosinophilic airway involvement, or specific genetic deficiencies like α1-antitrypsin deficiency [1]. These endotypes demonstrate superior predictive value for therapeutic responses compared to clinical phenotypes alone.

The eosinophilic endotype in COPD, characterized by elevated blood or sputum eosinophil counts, has gained particular attention due to its implications for inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) responsiveness. Similarly, biomarkers encompassing blood eosinophil counts, serum C-reactive protein, and sputum transcriptomics are progressively being implemented for patient stratification and guidance of targeted therapies, including inhaled corticosteroids or biologics [1].

The "treatable traits" framework represents a practical approach to implementing precision medicine in COPD by addressing modifiable factors beyond airflow limitation, such as comorbidities, psychosocial determinants, and exacerbation triggers [1]. This strategy moves beyond the traditional one-dimensional focus on FEV1 improvement to embrace a multidimensional approach to patient management.

Table 2: Major COPD Endotypes and Their Biomarkers

| COPD Endotype | Defining Biological Mechanism | Key Biomarkers | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eosinophilic | Type 2 inflammation | Blood/sputum eosinophilia | ICS responsiveness |

| Neutrophilic | Neutrophil-dominated inflammation, often with infection | Sputum neutrophils, IL-8, NLRP3 inflammasome activation | Macrolides, potentially phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors |

| Paucigranulocytic | Minimal inflammatory cell infiltration | Normal inflammatory cell counts | Limited anti-inflammatory benefit |

| α1-antitrypsin deficiency | Protease-antiprotease imbalance | Low AAT levels, specific genetic variants | AAT augmentation therapy |

Allergic Disease Endotypes: From Skin to Systemic Inflammation

Atopic Dermatitis Endotypes

Atopic dermatitis (AD) exemplifies the heterogeneity within allergic conditions, with emerging research revealing distinct molecular endotypes beneath the common clinical presentation. A comprehensive proteomic profiling study of Japanese adults with moderate-to-severe AD analyzed 1,248 serum proteins and identified two stable and reproducible patient clusters characterized by high (ADHI) and low (ADLO) inflammatory profiles [11].

Both clusters showed upregulation of canonical AD inflammatory mediators—including IL-13, IL-19, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine (PARC), thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC), CCL22, CCL26, and CCL27—but with significantly greater upregulation in the ADHI cluster [11]. Additionally, the ADHI cluster exhibited upregulation of proteins not typically associated with AD-related inflammation and was associated with protein networks representing a range of immune and non-immune pathways. These dysregulated protein signatures correlated with skin-based disease severity scores, providing a molecular basis for the clinical variability observed in AD [11].

Genetic and Epigenetic Foundations of Allergic Endotypes

Research into the genetic contributions to allergic endotypes has revealed that epigenetic mechanisms mediate the interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures in shaping disease expression. A study of 284 children from the Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) birth cohort identified three DNA methylation (DNAm) signatures associated with allergic phenotypes [23]. These signatures reflected three cardinal endotypes of asthma:

- Inhibited immune response to microbes

- Impaired epithelial barrier integrity

- Activated type 2 immune pathways [23]

The joint SNP heritability of each signature was significant (0.21, 0.26, and 0.17 respectively), indicating that genetic variation contributes substantially to these epigenetic signatures of allergic phenotypes [23]. This suggests that susceptibility to developing specific asthma endotypes is present at birth and poised to mediate individual epigenetic responses to early-life environments.

Methodologies for Endotype Discovery: A Technical Guide

Omics Technologies and Bioinformatics Approaches

The discovery and validation of disease endotypes rely heavily on advanced omics technologies and sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines. Transcriptomic analyses typically utilize RT-qPCR, DNA microarrays, and increasingly, RNA-Seq to profile gene expression patterns in relevant tissues [21]. Proteomic platforms like the Olink Explore 1536 assay enable comprehensive profiling of circulating proteins, providing insights into the systemic inflammatory state associated with different endotypes [11].

The analytical workflow for endotype discovery generally involves multiple steps:

- Unsupervised clustering (k-means, hierarchical clustering) to identify patient subgroups based on molecular data

- Differential expression analysis to define molecular signatures distinguishing clusters

- Network analysis (weighted gene co-expression network analysis) to identify coordinated protein or gene modules

- Validation in independent cohorts to ensure reproducibility [11]

For clustering analysis, determining the optimal number of clusters is critical. Researchers typically use methods like the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) elbow plot and cluster stability assessment across different parameters to establish the most biologically plausible and reproducible clustering scheme [11].

Integration of Real-World Data and Knowledge Graphs

A emerging methodology in endotype research involves linking electronic health records (EHRs) to biomedical knowledge graphs (BKGs) to create comprehensive patient representations that integrate clinical and molecular data [24]. This approach was applied to atopic dermatitis, mapping EHR data from over 107 million U.S. patients to the integrative Biomedical Knowledge Hub (iBKH), which contains 2,384,501 entities from 18 publicly available biomedical databases [24].

This integration enabled the identification of seven distinct AD subgroups each characterized by clinical and genomic features, demonstrating how computational approaches can uncover disease heterogeneity from real-world data [24]. Graph machine learning applied to these connected data sources facilitates the interpretation and extension of findings, particularly in disease subtype identification with molecular data contained in the BKG.

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Sputum Transcriptomic Endotyping in Asthma

Objective: To identify asthma endotypes based on gene expression profiles in induced sputum.

Sample Collection:

- Collect induced sputum using hypertonic saline (3-5%) inhalation

- Process samples within 2 hours of collection using dithiothreitol (DTT) to dissolve mucus

- Separate supernatant and cell pellet by centrifugation

- Count differential cell counts to determine inflammatory cell profile

RNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extract total RNA from cell pellet using commercial kits with DNase treatment

- Assess RNA quality using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation (RIN >7.0 required)

- Quantify RNA concentration by fluorometry

Transcriptomic Profiling:

- Perform whole-genome gene expression profiling using RNA-Seq or microarrays

- For RNA-Seq: Library preparation using poly-A selection, sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 30 million reads per sample)

- Alternatively, use RT-qPCR for targeted gene expression analysis of key cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, etc.)

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Preprocess raw data: quality trimming, adapter removal, alignment to reference genome

- Perform normalization (TPM for RNA-Seq, RMA for microarrays)

- Conduct differential expression analysis (DESeq2, limma)

- Apply unsupervised clustering (k-means, hierarchical) to identify transcriptional phenotypes

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, Gene Set Variation Analysis) [21]

Protocol 2: Serum Proteomic Endotyping in Atopic Dermatitis

Objective: To identify molecular endotypes in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis based on circulating protein profiles.

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect blood serum samples after appropriate washout periods for systemic and topical therapies (4-week systemic, 2-week topical)

- Use serum separator tubes, allow to clot for 30 minutes, centrifuge at 1,500 × g for 15 minutes

- Aliquot supernatant and store at -70°C until analysis

- Include healthy control samples matched for age and sex

Proteomic Profiling:

- Use Olink Explore 1536 panel following manufacturer's specifications

- Platform combines antibody-based immunoassay with proximity extension assay technology

- Signal detection via next-generation sequencing (Illumina NovaSeq6000)

- Include appropriate controls and calibrators across runs

Data Processing and Normalization:

- Normalize protein expression values relative to plate controls to generate Normalized Protein Expression (NPX) values

- Perform quality control filtering: exclude proteins with coefficient of variation <20%

- Typically, ~1,200 protein analytes remain for downstream analysis after QC

Cluster Analysis and Validation:

- Apply k-means clustering to proteomic data

- Determine optimal cluster number using within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) elbow method

- Assess cluster stability by including/excluding healthy controls and comparing assignments

- Validate clusters through differential expression analysis and correlation with clinical parameters [11]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Endotyping Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application in Endotyping |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics Platforms | RNA-Seq (Illumina), RT-qPCR, Microarrays | Gene expression profiling for molecular classification |

| Proteomic Assays | Olink Explore 1536, SOMAscan, Mass Spectrometry | Comprehensive protein profiling for endotype identification |

| Single-Cell Technologies | 10X Genomics, Parse Biosciences | Cell-type specific expression analysis at single-cell resolution |

| Epigenetic Tools | Illumina MethylationEPIC array, ATAC-Seq | DNA methylation profiling and chromatin accessibility mapping |

| Bioinformatics Tools | DESeq2, Seurat, Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis | Differential expression, clustering, and network analysis |

| Cell Sorting Technologies | FACS, MACS | Immune cell isolation and characterization |

| Biomarker Assays | ELISA, Luminex, Meso Scale Discovery | Validation of key protein biomarkers in patient samples |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Networks

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and molecular networks implicated in respiratory and allergic disease endotypes.

Diagram 1: T2-High Inflammation Pathway in Asthma

Diagram 2: Endotype Discovery Workflow

The study of endotypes in asthma, COPD, and allergic diseases represents a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize, classify, and treat these complex conditions. Moving beyond superficial clinical phenotypes to underlying biological mechanisms holds the promise of truly personalized medicine in respiratory and allergic diseases. The integration of multi-omics data, together with advanced computational approaches, is progressively revealing the intricate molecular architecture of disease heterogeneity.

For drug development professionals, the endotype framework offers opportunities to design more targeted clinical trials with enriched patient populations likely to respond to specific mechanism-based therapies. The ongoing development of accessible biomarkers for endotype identification will be crucial for translating these research insights into clinical practice.

Future directions in the field include the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to dynamic phenotyping, the integration of real-world evidence with molecular data through biomedical knowledge graphs, and a focus on early disease pathogenesis to enable preventive strategies [1] [24]. As these efforts mature, the vision of delivering the right treatment to the right patient at the right time moves closer to reality, potentially transforming outcomes for millions of patients with respiratory and allergic diseases worldwide.

The Systems Biology Toolkit: Methodologies for Endotype Discovery and Characterization

The pursuit of disease endotypes—distinct subtypes of conditions defined by unique functional or pathobiological mechanisms—represents a core challenge in modern precision medicine. Traditional single-omics approaches have provided valuable but fragmented insights into disease mechanisms. Multi-omics integration combines data from genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic layers to create a holistic model of biological systems, enabling the identification of these clinically meaningful endotypes [25] [26]. Systems biology provides the foundational framework for this integration, treating diseases not as isolated defects in single components but as emergent properties of perturbed molecular networks [27] [28].

The clinical imperative is clear: complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune disorders, and metabolic conditions exhibit profound heterogeneity in their clinical presentation and therapeutic response. Multi-omics profiling moves beyond superficial symptom-based classifications to reveal the molecular architecture underlying this heterogeneity [26] [29]. For example, integrating clinical parameters with multi-omic profiles has successfully identified molecularly distinct asthma endotypes with divergent therapeutic responses [30]. This approach facilitates a transition from reactive medicine to predictive, personalized healthcare by uncovering the fundamental biological processes that drive disease progression in specific patient subsets.

Multi-Omics Technologies and Data Characteristics

Core Omics Technologies and Their Measurements

Each omics layer captures a distinct aspect of biological organization, together forming a comprehensive picture of the flow of genetic information to functional phenotype.

Genomics identifies alterations at the DNA level, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), copy number variations (CNVs), and mutations through whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS). Landmark projects like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have mapped the genomic landscape of numerous cancers, revealing actionable alterations in approximately 37% of tumors [26].

Transcriptomics examines RNA expression patterns using microarray or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies, capturing mRNA, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and miRNAs. Clinically validated gene-expression signatures such as Oncotype DX (21-gene) and MammaPrint (70-gene) demonstrate the utility of transcriptomic biomarkers in guiding adjuvant chemotherapy decisions in breast cancer [26].

Proteomics investigates protein abundance, post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation), and interactions using mass spectrometry (MS) and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Proteomic data can reveal functional subtypes and druggable vulnerabilities missed by genomics alone [26].

Metabolomics focuses on the dynamic complement of small molecule metabolites, including carbohydrates, lipids, peptides, and nucleosides, typically analyzed via MS, LC-MS, or gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Metabolites represent the most downstream products of cellular processes, providing a direct readout of physiological state and metabolic pathway activity [25] [26].

Experimental Design for Multi-Omics Studies

Robust multi-omics integration begins with careful experimental design to minimize technical artifacts and enable valid biological inference. Key considerations include:

- Sample Selection and Handling: The ideal biological matrices (e.g., blood, plasma, tissues) allow for concurrent generation of multiple omics data types from the same sample set. Sample collection, processing, and storage protocols must be optimized to preserve the integrity of labile molecules like RNA and metabolites [25].

- Replication Strategy: The experimental design must account for biological, technical, analytical, and environmental replication to ensure statistical rigor and reproducibility.

- Meta-data Collection: Comprehensive meta-information about samples, experimental conditions, and processing protocols is essential for contextualizing multi-omics findings and ensuring their reinterpretation [25].

Computational Methods and Integration Strategies

Data Processing and Horizontal Integration

Before cross-omics integration, each individual omics dataset requires extensive preprocessing and quality control. This "horizontal integration" ensures data quality within each molecular layer [26]. Key steps include:

- Quality Control and Normalization: Removal of technical artifacts, batch effect correction, and normalization to account for varying library sizes or signal intensities.

- Feature Selection: Identification of biologically relevant features (e.g., differentially expressed genes, abundant proteins) to reduce dimensionality and computational complexity while retaining meaningful biological signal.

- Intra-Omics Analysis: Initial analysis within each omics layer to identify patterns, clusters, or associations with phenotypes of interest.

Vertical Integration Approaches

"Vertical integration" combines processed data from different omics layers to uncover interactions and relationships across molecular levels [26]. Several computational approaches exist:

- Network-Based Integration: This approach maps multiple omics datasets onto shared biochemical networks (e.g., metabolic pathways, protein-protein interaction networks) to improve mechanistic understanding. Analytes are connected based on known interactions, such as transcription factors mapped to their target transcripts or enzymes mapped to their metabolic substrates and products [29] [28].

- Concatenation-Based Methods: These methods merge diverse omics datasets into a single combined matrix for subsequent multivariate analysis. While straightforward, this approach requires careful handling of scale and distribution differences between data types.

- Model-Based Approaches: Methods like Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA+) use statistical models to decompose multi-omics data into a set of latent factors that represent shared sources of variation across data modalities [31].

- Machine Learning and AI: Advanced computational methods, including supervised and unsupervised machine learning, are increasingly used to detect intricate patterns and dependencies within multi-omics datasets [26] [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method Type | Representative Tools | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network-Based | Pathway Tools [33], Cytoscape | Maps omics data onto known biological networks | Provides mechanistic context, intuitive visualization | Limited to known interactions, less discovery potential |

| Concatenation-Based | MANAclust [30] | Merges datasets into a combined matrix | Simple implementation, preserves all information | Sensitive to data scaling, high dimensionality |

| Factorization-Based | MOFA+ [31], intNMF | Decomposes data into latent factors | Identifies co-varying features, handles missing data | Linear assumptions may not capture complex interactions |

| Non-Linear Dimensionality Reduction | GAUDI [31] | Uses UMAP embeddings to capture non-linear relationships | Handles complex data structures, powerful clustering | Parameter sensitivity, computational intensity |

Advanced Integration Tools and Visualization

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting complex multi-omics data. Tools like the Pathway Tools Cellular Overview enable simultaneous visualization of up to four omics data types on organism-scale metabolic network diagrams, using different visual channels (e.g., reaction arrow color and thickness, metabolite node color and thickness) to represent different data types [33]. Emerging methods like GAUDI (Group Aggregation via UMAP Data Integration) leverage independent UMAP embeddings for concurrent analysis of multiple data types, effectively uncovering non-linear relationships among different omics layers and facilitating intuitive cluster identification [31].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

A Protocol for Predictive Biomarker Identification

The following protocol outlines a machine learning pipeline for identifying predictive protein biomarkers for complex diseases, based on methodology successfully applied to UK Biobank data [34]:

- Cohort Selection and Matching: Identify patient cohorts with the disease of interest and select age/sex-matched controls. Divide patients into incident (diagnosed after assessment) and prevalent (already diagnosed at assessment) cases.

- Multi-Omics Data Collection: Acquire genomic (e.g., 90 million genetic variants), proteomic (e.g., 1,453 proteins), and metabolomic (e.g., 325 metabolites) data for all subjects.

- Data Preprocessing: Clean data by removing outliers and technical artifacts. Impute missing values using appropriate methods (e.g., k-nearest neighbors). Normalize data to account for technical variance.

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection algorithms to identify the most discriminative molecules for separating cases from controls. For genomics, use established polygenic risk scores where available.

- Model Training and Validation: Train classification models (e.g., logistic regression, random forests) using tenfold cross-validation on training datasets. Compare results on holdout test sets to evaluate performance.

- Performance Evaluation: Generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculate areas under the curve (AUCs) to assess predictive performance. Determine the minimal number of biomarkers needed for clinically significant prediction (AUC ≥0.8).

- Biological Interpretation: Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology analysis) on the top protein biomarkers to identify significantly enriched pathways and biological processes.

Protocol for Clinical Endotype Discovery Using MANAclust

MANAclust (Merged Affinity Network Association Clustering) provides an automated pipeline for integrating clinical and multi-omics profiles to identify disease endotypes [30]:

- Data Collection: Assemble comprehensive datasets including clinical parameters (e.g., age, symptom scores, treatment response) and multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics).

- Feature Selection: Apply MANAclust's inter-variable relative information algorithm to select meaningful categorical and numerical features from both clinical and molecular data.

- Affinity Network Construction: Build affinity networks for each data type based on similarity metrics between samples.

- Network Merging: Merge affinity networks into a single combined network that incorporates information from all data modalities.

- Unsupervised Clustering: Perform clustering on the merged network to identify patient subgroups with distinct clinical and molecular profiles.

- Cluster Validation: Validate clusters by assessing their association with clinical outcomes, survival differences, or treatment responses.

- Molecular Characterization: Identify the key molecular features (e.g., specific genetic variants, protein abundances, metabolite levels) that distinguish each cluster, defining the endotype.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Stabilizes intracellular RNA for transcriptomics |

| EDTA or Citrate Plasma Tubes | Preserves proteins and metabolites for proteomics/metabolomics | |

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissue | Preserves tissue architecture for spatial omics (with limitations for some assays) [25] | |

| Sequencing & Analysis | Next-Generation Sequencer (Illumina, PacBio) | Whole genome, exome, and transcriptome sequencing [26] |

| SWATH-MS Kit | Data-independent acquisition proteomics for comprehensive protein quantification [25] | |

| UPLC-MS/MS System | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for metabolomics [25] | |

| Computational Tools | Pathway Tools | Metabolic network visualization and multi-omics painting [33] |

| MANAclust | Joint clustering of clinical and multi-omics data [30] | |

| GAUDI | Non-linear integration using UMAP embeddings [31] | |

| DriverDBv4, HCCDBv2 | Multi-omics databases for specific cancer types [26] |

Applications in Disease Endotype Identification and Clinical Translation

Biomarker Performance Across Omics Layers

Comparative analyses of different omics layers have yielded insights into their relative strengths for predictive applications. A comprehensive assessment of genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data from the UK Biobank revealed that proteins demonstrated superior predictive performance for both incident and prevalent cases of nine complex diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, type 2 diabetes, and atherosclerotic vascular disease [34]. The median AUC for incidence prediction using just five proteins was 0.79, compared to 0.70 for metabolites and 0.57 for genetic variants. This suggests that a limited panel of proteins may suffice for both predicting incident disease and diagnosing prevalent conditions, though the optimal biomarker combination is context-dependent.

Table 3: Predictive Performance of Different Omics Layers for Complex Diseases

| Omics Layer | Median AUC (Incidence) | Median AUC (Prevalence) | Number of Features for AUC ≥0.8 | Representative Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteomics | 0.79 (0.65-0.86) | 0.84 (0.70-0.91) | 5 or fewer for most diseases | MMP12, TNFRSF10B, HAVCR1 for ASVD [34] |

| Metabolomics | 0.70 (0.62-0.80) | 0.86 (0.65-0.90) | Variable by disease | 2-hydroxyglutarate for IDH1/2-mutant gliomas [26] |

| Genomics | 0.57 (0.53-0.67) | 0.60 (0.49-0.70) | Often cannot reach 0.8 with PRS alone | Tumor Mutational Burden for immunotherapy response [26] |

Case Studies in Endotype Discovery

Asthma Endotyping: Application of MANAclust to a clinically and multi-omically phenotyped asthma cohort revealed clinically and molecularly distinct clusters, including heterogeneous groups of "healthy controls" and viral and allergy-driven subsets of asthmatic subjects. Importantly, subjects with similar clinical presentations showed disparate molecular profiles, highlighting the need for additional molecular testing to uncover true asthma endotypes [30].

Cancer Subtyping and Survival Prediction: GAUDI has demonstrated exceptional performance in identifying clinically relevant cancer subtypes from TCGA multi-omics data. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), GAUDI identified a small high-risk group with a median survival of only 89 days—a threshold not reached by other integration methods. This precision in identifying extreme survival groups enables more targeted therapeutic approaches for high-risk patients [31].

The Cancer Biomarker Atlas: The creation of an interactive atlas of genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic biomarkers enables systematic prioritization of biomarker types and numbers for different complex diseases. This resource facilitates the selection of optimal biomarker panels based on the specific clinical context and required sensitivity/specificity trade-offs [34].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

As multi-omics integration continues to evolve, several key trends and challenges are shaping its trajectory:

- Single-Cell and Spatial Multi-Omics: The field is rapidly advancing toward single-cell resolution, enabling the characterization of cellular heterogeneity within tissues. Spatial multi-omics technologies further add geographical context, preserving the architectural relationships between cells that are critical for understanding tissue function and disease pathology [26] [32].

- Data Harmonization and Standardization: The integration of multiple discrepant data sources remains a significant challenge. Advances in computational methods, particularly data harmonization techniques, are essential for unifying disparate datasets with varying formats, scales, and biological contexts [32].

- AI and Machine Learning: Artificial intelligence and machine learning are becoming increasingly sophisticated at detecting intricate patterns and dependencies within multi-omics datasets. The development of purpose-built analysis tools specifically designed for multi-omics data will be crucial for extracting meaningful biological insights [26] [32].

- Clinical Implementation: The translation of multi-omics discoveries to clinical practice requires addressing issues of reproducibility, validation in diverse patient populations, and the development of clinically feasible assay platforms. Liquid biopsies exemplify the clinical impact of multi-omics, analyzing biomarkers like cell-free DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites non-invasively for early disease detection and treatment monitoring [32].

The ongoing integration of multi-omics data with clinical measurements promises to revolutionize patient stratification, disease prognosis, and treatment optimization. By embracing collaborative efforts across academia, industry, and regulatory bodies, the field will continue to advance personalized medicine, offering deeper insights into human health and disease [29] [32].

Leveraging Single-Cell Technologies to Map Cellular Heterogeneity and Immune Profiles