Decoding Complex Diseases: A Network Medicine Approach from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Complex diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer's, and diabetes arise from multifaceted interactions between genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, defying explanations by single genes.

Decoding Complex Diseases: A Network Medicine Approach from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Complex diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer's, and diabetes arise from multifaceted interactions between genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, defying explanations by single genes. Network medicine has emerged as a transformative discipline that addresses this complexity by applying systems-level analyses to biological networks. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of disease networks and interactomes. It delves into advanced methodological approaches powered by single-cell omics and AI, offering practical solutions for common computational and data integration challenges. Furthermore, it covers rigorous techniques for validating disease modules and conducting comparative network analyses across species and conditions. By synthesizing knowledge across these four core intents, this review underscores the pivotal role of network-based approaches in elucidating disease mechanisms, predicting novel therapeutic targets, and paving the way for personalized medicine strategies.

Mapping the Cellular Universe: Foundational Concepts of Biological Networks in Disease

In molecular biology, an interactome is defined as the whole set of molecular interactions in a particular cell [1]. The term specifically refers to physical interactions among molecules, such as protein-protein interactions (PPIs), but can also describe sets of indirect interactions among genes, known as genetic interactions [1]. Mathematically, interactomes are displayed as graphs or biological networks, which should not be confused with other network types such as neural networks or food webs [1]. The word "interactome" was originally coined in 1999 by a group of French scientists headed by Bernard Jacq, marking the emergence of a new field focused on systematically mapping cellular interactions [1].

The study of interactomes, known as interactomics, represents a discipline at the intersection of bioinformatics and biology that deals with studying both the interactions and the consequences of those interactions between and among proteins and other molecules within a cell [1]. Interactomics takes a "top-down" systems biology approach, utilizing large sets of genome-wide and proteomic data to infer correlations between different molecules and formulate new hypotheses about feedback mechanisms that can be tested through experiments [1]. The size of an organism's interactome has been suggested to correlate better than genome size with the biological complexity of the organism, highlighting the critical importance of comprehensive interaction mapping for understanding cellular complexity [1].

The Interactome in Complex Disease Research

Complex diseases, including asthma, epilepsy, hypertension, Alzheimer's disease, manic depression, schizophrenia, cancer, diabetes, and heart diseases, are caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors [2]. Fundamental biological questions in complex disease research include how individual cells differentiate into various tissues/cell types, how cellular activities are operated in a coordinated manner, and what gene regulatory mechanisms support these processes [2]. Disorders in regulatory activities typically relate to the occurrence and development of complex diseases, making the elucidation of these networks essential for understanding disease mechanisms [2].

Network medicine applies fundamental principles of complexity science and systems medicine to integrate and analyze complex structured data, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, to characterize the dynamical states of health and disease within biological networks [3]. The incorporation of techniques based on statistical physics and machine learning in network medicine has significantly refined our understanding of disease networks, providing novel insights into complex disease mechanisms [3]. Despite these achievements, the maturation of network medicine presents challenges that must be addressed, including limitations in defining biological units and interactions, interpreting network models, and accounting for experimental uncertainties [3].

Table 1: Types of Biological Networks in Complex Disease Research

| Network Type | Description | Role in Complex Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network | Comprehensive compilation of physical interactions among proteins | Reveals disrupted protein complexes and signaling pathways in disease states |

| Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) | Models regulatory interactions between transcription factors/non-coding RNAs and target genes | Elucidates dysregulated transcriptional programs driving disease progression |

| Genetic Interaction Network | Documents how gene mutations interact to affect cellular function | Identifies synthetic lethal relationships and combinatorial drug targets |

| Metabolic Network | Maps biochemical reactions and metabolite conversions | Uncovers metabolic reprogramming in cancer and other proliferative diseases |

| Signal Transduction Network | Charts information flow through signaling pathways | Reveals aberrant signaling in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases |

Experimental Methods for Interactome Mapping

Core Experimental Techniques

The basic unit of a protein network is the protein-protein interaction (PPI), and several methods have been used on a large scale to map whole interactomes [1]. The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system is suited to explore binary interactions between two proteins at a time, while affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry (AP/MS) is suited to identify protein complexes [1]. Both methods can be used in a high-throughput fashion, though they have distinct advantages and limitations. Yeast two-hybrid screens may detect false positive interactions between proteins that are never expressed in the same time and place, while affinity capture mass spectrometry better indicates functional in vivo protein-protein interactions and is considered the current gold standard [1]. It has been estimated that typical Y2H screens detect only approximately 25% of all interactions in an interactome, highlighting the challenge of achieving comprehensive coverage [1].

Single-Cell Multimodal Omics Technologies

The fast development of single-cell omics technologies has enabled comprehensive profiling of genetic, epigenetic, spatial, proteomic, and lineage information, providing exciting opportunities for systematic investigation of rare cell types, cellular heterogeneity, evolution, and cell-to-cell interactions in a wide range of tissues and cell populations [2]. The generated multimodal information from individual cells has enabled the elucidation of cellular reprogramming, developmental dynamics, communication networks in disease development, and identification of unique malfunctions of individual cells [2].

Single-cell multimodal omics (scMulti-omics) opens up new frontiers by simultaneously measuring multiple modalities, allowing information from one modality to improve the interpretation of another [2]. Currently, at most four types of single-cell omics can be measured simultaneously, leading to 13 combinations, including nine double-modality sequencing techniques, three triple-modality sequencing techniques, and one quad-modality sequencing technique [2]. This technological advancement has brought about new resources for understanding the heterogeneous regulatory landscape (HRL) that characterizes cell-type-specific genetic and epigenetic regulatory relationships in complex diseases [2].

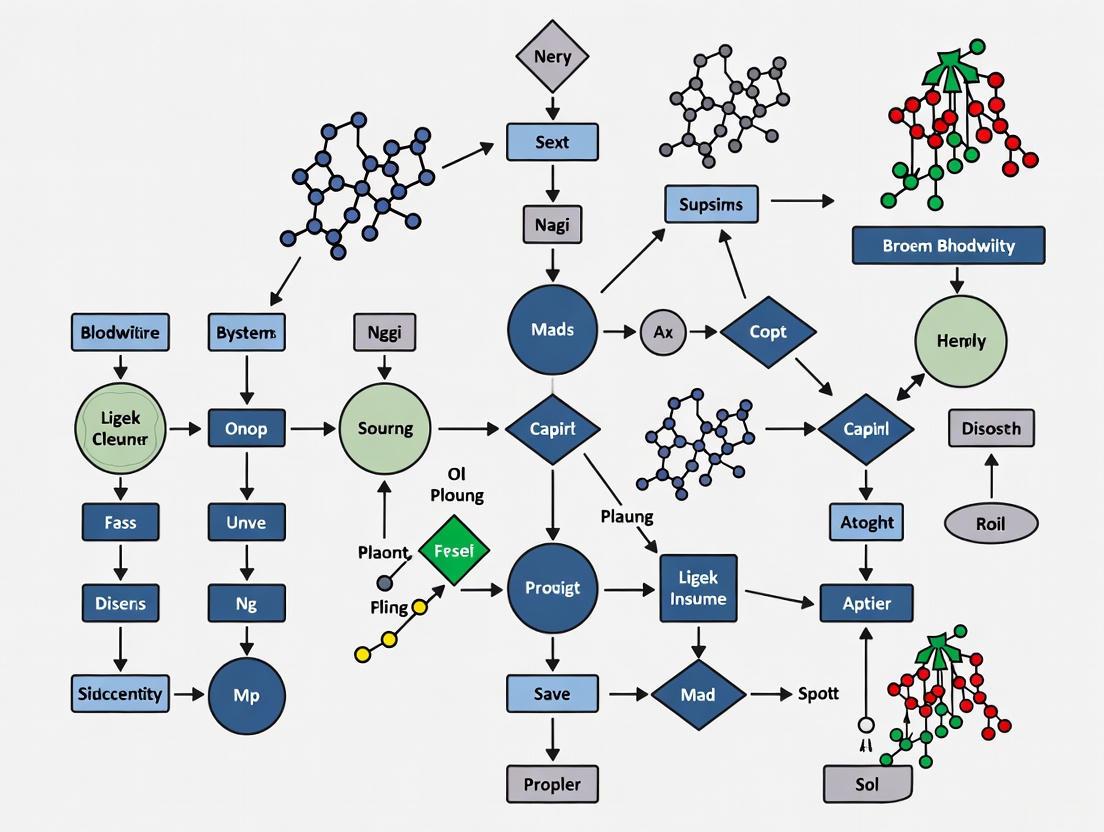

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Workflow. This diagram illustrates the workflow for generating heterogeneous regulatory landscapes from single-cell multimodal omics data.

Table 2: HRL-Associated Networks from Single-Cell Omics Data

| Network Type | Sequencing Method | Inference Tool Examples | Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Network (GCN) | scRNA-Seq | WGCNA | Identifies aberrant co-expression patterns in disease states |

| Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) | scRNA-Seq | SINCERITIES | Models TF-driven differentiation in diseases like leukemia |

| Cis-co-accessibility Network (CCAN) | scATAC-Seq | N/A | Reveals how accessible cis-regulatory elements orchestrate gene regulation |

| Methylation-associated GRN (MGRN) | scMethyl-Seq | N/A | Captures impacts of epigenetic factors on gene regulatory mechanisms |

| Chromatin Interaction Network (CIN) | scHi-C | N/A | Quantifies interplays between chromatin loci in 3D space |

| CRE-Gene Interaction Network (CGN) | scRNA-Seq + scATAC-Seq | N/A | Details how CREs influence gene expression in single cells |

| TF-CRE Interaction Network (TCN) | scRNA-Seq + scATAC-Seq | N/A | Identifies TFs regulating disease-specific genes |

Computational Methods for Interactome Analysis

Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

Computational algorithms offer an efficient alternative to the prediction of PPIs at scale, addressing the limitations of experimental methods which are costly, time-consuming, and often yield sparse datasets [4]. Existing prediction approaches mainly leverage protein properties such as protein structures, sequence composition, and evolutionary information [4]. Recently, protein language models (PLMs) trained on large public protein sequence databases have been used for encoding sequence composition, evolutionary, and structural features, becoming the method of choice for representing proteins in state-of-the-art PPI predictors [4].

The PLM-interact model represents a significant advancement in PPI prediction by extending and fine-tuning a pre-trained PLM, ESM-2, to directly model PPIs through two key extensions: longer permissible sequence lengths in paired masked-language training to accommodate amino acid residues from both proteins, and implementation of "next sentence" prediction to fine-tune all layers of ESM-2 where the model is trained with a binary label indicating whether the protein pair is interacting or not [4]. This architecture enables amino acids in one protein sequence to be associated with specific amino acids from another protein sequence through the transformer's attention mechanism [4]. When trained on human PPI data, PLM-interact achieves significant improvement compared to other predictors when applied to mouse, fly, worm, yeast, and E. coli datasets, demonstrating its cross-species applicability [4].

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning (ML) has recently emerged as a powerful tool that can predict and analyze PPIs, offering complementary insights into traditional experimental approaches [5]. ML-based methods such as Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) have been widely applied as a promising solution for predicting PPI at large scales [5]. These methods utilize different forms of biological data, such as protein sequences, 3D structures, genomic context, and functional annotations, to learn and predict PPIs with great precision [5].

In plant biology specifically, ML-assisted PPI predictions have enabled scientists to model rice proteome interactions, reveal concealed relationships among proteins, and prioritize genes for downstream analysis and breeding [5]. The performance of ML models for PPI predictions is determined largely by the quality of training data, with key resources including general repositories like STRING and BioGRID, though these have limited coverage for non-model organisms [5]. A transformative advancement is the availability of rice-specific structural proteome data through AlphaFold2, enabling the large-scale extraction of structural features for interaction prediction [5].

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Workflow for PPI Prediction. This diagram outlines the workflow for machine learning-based prediction of protein-protein interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Interactome Mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Interactome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | Detects binary protein-protein interactions | Initial large-scale screening of interaction partners |

| Affinity Purification Matrices | Isolates protein complexes from cell lysates | Preparation of samples for mass spectrometry analysis |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Stabilizes transient protein interactions | Capturing ephemeral interactions for structural studies |

| Single-Cell Barcoding Reagents | Enables multiplexing of single-cell samples | Tracking individual cells in multimodal omics experiments |

| Chromatin Accessibility Reagents | Identifies open chromatin regions | Mapping regulatory elements in scATAC-Seq experiments |

| Protein Language Models | Predicts protein structures and interactions | Computational forecasting of PPIs and mutational effects |

| CETSA Reagents | Validates direct target engagement in intact cells | Confirming physiological relevance of drug-target interactions |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The field of drug discovery is undergoing a transformative shift, with artificial intelligence evolving from a disruptive concept to a foundational capability in modern R&D [6]. Machine learning models now routinely inform target prediction, compound prioritization, pharmacokinetic property estimation, and virtual screening strategies [6]. Recent work has demonstrated that integrating pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data can boost hit enrichment rates by more than 50-fold compared to traditional methods, accelerating lead discovery while improving mechanistic interpretability [6].

CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) has emerged as a leading approach for validating direct binding in intact cells and tissues, addressing the need for physiologically relevant confirmation of target engagement as molecular modalities become more diverse [6]. Recent work has applied CETSA in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry to quantify drug-target engagement in rat tissue, confirming dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization ex vivo and in vivo [6]. This exemplifies CETSA's unique ability to offer quantitative, system-level validation, closing the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [6].

The traditionally lengthy hit-to-lead (H2L) phase is being rapidly compressed through the integration of AI-guided retrosynthesis, scaffold enumeration, and high-throughput experimentation (HTE) [6]. These platforms enable rapid design–make–test–analyze (DMTA) cycles, reducing discovery timelines from months to weeks [6]. In a 2025 study, deep graph networks were used to generate over 26,000 virtual analogs, resulting in sub-nanomolar inhibitors with over 4,500-fold potency improvement over initial hits, representing a model for data-driven optimization of pharmacological profiles [6].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances in interactome research, several challenges remain. The maturation of network medicine presents limitations in defining biological units and interactions, interpreting network models, and accounting for experimental uncertainties that hinder the field's progress [3]. The next phase of network medicine must expand the current framework by incorporating more realistic assumptions about biological units and their interactions across multiple relevant scales [3]. This expansion is crucial for advancing our understanding of complex diseases and improving strategies for their diagnosis, treatment, and prevention [3].

In computational prediction, while PLM-interact demonstrates improved performance in cross-species PPI prediction, challenges remain in predicting interactions for evolutionarily divergent species and accounting for the impact of protein modifications on interactions [4]. The fine-tuned version of PLM-interact shows promise in identifying mutation effects on interactions, but further validation is needed to establish its robustness across diverse mutation types and biological contexts [4].

The future of interactome research will likely involve greater integration of multi-omics data, more sophisticated deep learning architectures, and improved experimental validation methods to address current limitations. As these technologies mature, they will progressively enhance our ability to map complete cellular relationship maps and apply this knowledge to understand complex disease mechanisms and develop novel therapeutic interventions.

Biological systems, from molecular interactions within a cell to the organization of neural circuits, are fundamentally interconnected. Representing these systems as networks—where biological entities like proteins, genes, or cells are nodes and their interactions are edges—provides a powerful framework for understanding their structure and function. The topology, or connection pattern, of these networks is not random; it is shaped by evolution and is deeply linked to system robustness, dynamics, and function. Analyzing network topology has become a cornerstone of systems biology, offering crucial insights into the mechanisms that underlie complex diseases. When these intricate networks malfunction, it can lead to a breakdown of normal cellular processes, resulting in pathological states. Consequently, a deep understanding of key network properties—namely, scale-free, small-world, and modularity—is indispensable for deciphering the origin and progression of complex diseases and for identifying potential therapeutic strategies. This guide details these core properties, their biological significance, and their specific relevance to biomedical research.

Scale-Free Networks

Definition and Topological Characteristics

A scale-free network is defined by a degree distribution that follows a power law, denoted as ( P(k) \sim k^{-\alpha} ), where ( k ) is the node degree and ( \alpha ) is the power-law exponent. This mathematical structure implies that the probability of a node having a large number of connections is significantly higher than in a random network. The defining feature is heterogeneity: while the vast majority of nodes have few links, a few critical nodes, known as hubs, possess an exceptionally high number of connections. This distribution is "scale-free" because it lacks a characteristic peak or scale for the node degree. Real-world networks often only approximate this ideal, with the power law holding for degrees above a minimum value ( k_{min} ) [7]. It is crucial to distinguish scale-free topology from the generating mechanisms often associated with it, such as preferential attachment, as various mechanisms can produce similar topological patterns [7].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Scale-Free Networks

| Feature | Description | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Distribution | Power-law tail ( P(k) \sim k^{-\alpha} ) | Presence of a few highly connected hubs amidst many low-degree nodes. |

| Hub Prevalence | Existence of nodes with orders of magnitude more connections than the average. | Hubs are often critical for network integrity and function. |

| Robustness | Resilience to random failure but fragility to targeted hub attacks. | Biological systems can withstand random perturbations but are vulnerable to specific genetic mutations or pathogen attacks on hubs. |

| Exponent (α) | Typically reported between 2 and 3 for biological networks [8]. | Governs the relative abundance of hubs; ( 2 < \alpha < 3 ) implies infinite variance in the infinite network limit. |

Biological Significance and Relevance to Disease

Scale-free organization is observed in various biological networks, including protein-protein interactions, metabolic networks, and gene regulatory networks. The presence of hubs is of paramount functional importance. These hubs often represent essential proteins or genes; their disruption is frequently linked to severe phenotypes, including disease and lethality. This creates a biological paradox: the same topological property that confers robustness to random failure also introduces vulnerability to targeted attacks. In complex diseases, the failure of hub nodes can lead to catastrophic network failure. For instance, in cancer, oncogenes and tumor suppressors can act as hubs, and their dysregulation can propagate dysfunction throughout the cellular network. Furthermore, the scale-free property presents a challenge for machine learning models in bioinformatics. These models can develop a prediction bias, learning to predict interactions based primarily on node degree rather than intrinsic molecular features, potentially leading to over-optimistic performance estimates if not properly controlled for with strategies like Degree Distribution Balanced (DDB) sampling [9].

Experimental Analysis Protocol

Objective: To determine if a given biological network (e.g., a protein-protein interaction network) exhibits a scale-free topology.

- Data Acquisition: Obtain a comprehensive dataset of interactions from a reliable database (e.g., STRING, BioGRID, or a specialized resource like the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP) for phytochemical-target networks [10]).

- Network Construction: Represent biological entities as nodes and their physical or functional interactions as undirected edges.

- Degree Distribution Calculation: Compute the degree ( k ) for every node in the network. Generate the degree distribution ( P(k) ), which is the fraction of nodes in the network with degree ( k ).

- Power-Law Fitting and Validation:

- Plot ( P(k) ) against ( k ) on a log-log scale. A straight line is suggestive of a power law.

- Use state-of-the-art statistical methods, such as the maximum likelihood approach detailed by Broido & Clauset, to fit a power-law model ( P(k) \sim k^{-\alpha} ) to the data and estimate the parameter ( \alpha ) and the lower bound ( k_{min} ) [7].

- Perform a goodness-of-fit test (e.g., based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic) to calculate a p-value. A p-value > 0.1 indicates the power law is a plausible fit for the data.

- Compare with Alternative Distributions: Use a normalized likelihood-ratio test to compare the power-law model against alternative heavy-tailed distributions, such as the log-normal or exponential, to determine which model provides the best fit [7].

- Hub Identification: Identify nodes with a degree significantly higher than the network average. These are candidate hubs for further biological validation.

Figure 1: Workflow for analyzing a network for scale-free topology.

Small-World Networks

Definition and Topological Characteristics

A small-world network is characterized by two primary metrics: a high clustering coefficient and a short characteristic path length. The clustering coefficient (( C )) measures the local "cliquishness" or the likelihood that two neighbors of a node are also connected. The characteristic path length (( L )) is the average shortest path distance between all pairs of nodes in the network. Small-world networks exhibit ( C ) significantly higher than that of an equivalent random graph (( C \gg Cr )) while maintaining ( L ) comparable to a random graph (( L \approx Lr )) [11]. This structure emerges from a topology that is mostly regular but includes a few long-range "shortcuts" that dramatically reduce the overall distance between nodes. This property is famously encapsulated in the "six degrees of separation" phenomenon in social networks. The small-world property can be quantified by the small-world index ( \sigma = \frac{C/Cr}{L/Lr} ), where ( \sigma > 1 ) indicates small-worldness [11].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Small-World Networks

| Feature | Description | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| High Clustering | Local neighborhoods are densely interconnected. | Functional modules or complexes can form easily (e.g., protein complexes). |

| Short Path Length | Any two nodes can be connected via a small number of steps. | Enables rapid information/propagation across the entire network (e.g., neural signaling, signal transduction). |

| Emergent Structures | Recent research highlights the role of clusters of nodes linked by shortcuts, not just the number of shortcuts [12]. | The mean degree of clusters linked by shortcuts (( y )) is a key parameter controlling the crossover from large-world to small-world behavior. |

Biological Significance and Relevance to Disease

The small-world architecture offers a compelling model for biological systems, balancing two crucial demands: functional specialization (enabled by local clustering) and integrated function (enabled by short global paths). In neuroscience, brain networks consistently exhibit small-world properties, which are thought to support segregated information processing in localized clusters while allowing for efficient global communication for integrated cognition. In cellular biology, signaling and metabolic networks display small-world topologies, facilitating swift and efficient response to environmental changes. Dysregulation of this delicate balance is implicated in disease. For example, in neurological and psychiatric disorders like Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorder, the brain's network is often found to deviate from the optimal small-world configuration, sometimes exhibiting a pathologically higher or lower clustering coefficient or longer path lengths, which can disrupt the efficient flow of information [8]. The small-world structure is also crucial for synchronization phenomena, such as the coordinated firing of neurons [11].

Experimental Analysis Protocol

Objective: To assess the small-world properties of a biological network (e.g., a functional brain network derived from fMRI).

- Network Construction: Create a functional connectivity matrix from neuroimaging data (e.g., fMRI). Define nodes as brain regions and edges as significant correlations or coherence in neural activity between regions.

- Calculate Metrics:

- Clustering Coefficient (( C )): For each node ( i ), calculate its local clustering coefficient ( Ci = \frac{2Ei}{ki(ki-1)} ), where ( Ei ) is the number of edges between the ( ki ) neighbors of node ( i ). The network's global clustering coefficient ( C ) is the average of all ( C_i ).

- Characteristic Path Length (( L )): Compute the shortest path length between every pair of nodes in the network. ( L ) is the average of all these path lengths.

- Generate Equivalent Random Graphs: Create an ensemble of Erdős–Rényi random graphs with the same number of nodes and edges as the empirical network. Calculate the average clustering coefficient (( Cr )) and average path length (( Lr )) for this ensemble.

- Compute Small-World Index: Calculate ( \sigma = \frac{C/Cr}{L/Lr} ). A value of ( \sigma > 1 ) confirms small-world organization.

- Statistical Testing: Compare the empirical ( C ) and ( L ) to the distributions of ( Cr ) and ( Lr ) from the random graph ensemble to determine statistical significance.

Figure 2: Workflow for assessing small-world properties in a network.

Modularity

Definition and Topological Characteristics

Modularity, in the context of networks, refers to the organization of nodes into groups or communities (modules) characterized by dense internal connections and sparser connections between them. A high modularity score indicates a network that is more partitioned than would be expected by random chance. Formally, modularity (( Q )) is defined as ( Q = \frac{1}{2m} \sum{ij} [A{ij} - \frac{ki kj}{2m}] \delta(ci, cj) ), where ( A{ij} ) is the adjacency matrix, ( m ) is the total number of edges, ( ki ) is the degree of node ( i ), ( ci ) is the community of node ( i ), and the Kronecker delta ( \delta(ci, c_j) ) is 1 if nodes ( i ) and ( j ) are in the same community and 0 otherwise [13]. This property is a hallmark of many complex systems, reflecting a semi-decomposable structure where modules can perform specialized functions with some degree of autonomy.

Table 3: Key Characteristics of Modular Networks

| Feature | Description | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Community Structure | Presence of groups of nodes with high internal connectivity. | Corresponds to functional units (e.g., protein complexes, metabolic pathways). |

| Sparsity of Between-Module Connections | Connections between modules are less frequent than within modules. | Allows for functional specialization and limits the spread of perturbations across the entire system. |

| Evolutionary Emergence | Arises from processes like gene duplication and diversification, and is subject to evolutionary pressures [13]. | Provides a framework for evolutionary adaptability, as modules can be modified or repurposed without disrupting the entire system. |

Biological Significance and Relevance to Disease

Modularity is pervasive in biology, observed across scales from protein domains and metabolic pathways to ecological food webs. This organization confers robustness and evolvability. Robustness is achieved because a failure or perturbation within one module is less likely to cascade and cause a complete system failure. Evolvability is enabled because modules can be independently modified, duplicated, or repurposed through evolution. In the context of disease, the breakdown of modular structure or the rewiring of inter-modular connections can be a key driver of pathology. For example, in cancer, the normal modular organization of gene regulatory networks and signaling pathways is often disrupted. This can lead to the hijacking of modules that control cell proliferation or the decoupling of modules that maintain tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, network pharmacology, which aims to discover drugs that can target multiple nodes in a disease-associated module, relies heavily on identifying these key functional modules to develop multi-target therapeutic strategies [10] [14].

Experimental Analysis Protocol

Objective: To identify functional modules within a biological network (e.g., a gene regulatory network).

- Data Preparation: Compile a comprehensive network. For a Gene Regulatory Network (GRN), nodes represent genes or transcriptional factors, and edges represent regulatory interactions (e.g., from ChIP-seq data or inferred from gene expression) [13].

- Community Detection: Apply a community detection algorithm to partition the network into modules. Common algorithms include:

- Girvan-Newman algorithm: An edge-betweenness-based divisive method.

- Louvain method: A greedy, heuristic optimization algorithm that is highly efficient for large networks.

- Clauset-Newman-Moore algorithm: Another modularity-optimization method.

- Calculate Modularity Score: Use the formal definition of modularity (( Q )) to calculate the quality of the partition found by the algorithm. A higher ( Q ) value (theoretically max 1) indicates a stronger community structure.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: To biologically validate the identified modules, perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology (GO) or Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis) on the genes within each module. A statistically significant enrichment of specific biological functions or pathways within a module confirms its functional relevance.

- Perturbation Analysis: Experimentally or computationally perturb key nodes (e.g., hub nodes within a module) and observe the effect on module function and stability.

Figure 3: Workflow for detecting and validating modules in a biological network.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Network Analysis in Biology

| Resource Type | Example(s) | Function in Network Research |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction Databases | STRING, BioGRID, DrugBank, TCMSP, PharmGKB [10] [14] | Provide curated, machine-readable data on molecular interactions (protein-protein, drug-target, etc.) for network construction. |

| Network Analysis & Visualization Software | Cytoscape (with plugins) [10] | A primary platform for visualizing molecular interaction networks and integrating with gene expression and other functional data. |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock [10] | Used to validate predicted interactions within a network (e.g., between a drug compound and a protein target) by simulating the physical binding. |

| Community Detection Algorithms | Girvan-Newman, Louvain, Clauset-Newman-Moore [13] | Computational methods implemented in code (e.g., in Python using NetworkX) to identify modules or communities within a network. |

| Gene Ontology & Pathway Databases | Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG [10] | Provide standardized functional annotations and pathway maps for the biological interpretation of network nodes and modules. |

Integrated View and Future Perspectives in Disease Research

In reality, biological networks are not defined by a single topological property. They often integrate scale-free, small-world, and modular characteristics into a cohesive "hierarchical" architecture. This integrated structure supports both local specialized processing in modules and global efficiency in communication, all while being robust yet vulnerable in a way that has profound implications for health and disease. The field of network medicine is built upon this foundation, using network topology to understand disease mechanisms, identify new drug targets, and repurpose existing drugs. For instance, link prediction algorithms applied to drug-disease networks have shown remarkable success (Area Under the Curve > 0.95 in some studies) in identifying new therapeutic indications for existing drugs, a powerful application of network science in drug repurposing [14]. As we move forward, the key challenges will be to move beyond simple topological descriptions and to truly understand the dynamical processes operating on these networks. Future research will need to integrate multi-omics data into more comprehensive networks, develop more sophisticated dynamical models, and create new computational tools that can fairly assess predictions without being biased by inherent network properties like scale-freeness [9]. This will ultimately accelerate the development of novel, network-based therapeutic strategies for complex diseases.

Complex diseases, including cancer, autism, and Alzheimer's disease, are caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, characterized by significant heterogeneity and the interplay of numerous genetic perturbations. Network medicine has emerged as a powerful paradigm for addressing this complexity, reframing disease not as a consequence of single mutations but as dysfunction in interconnected molecular modules. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core concepts, methods, and experimental protocols for identifying these disease modules. By leveraging physical and functional interaction networks, researchers can disentangle disease heterogeneity, pinpoint key driver proteins, and uncover the pathways that bridge genotypic variation to phenotypic outcomes, thereby laying the groundwork for innovative therapeutic strategies [15] [16] [3].

The central challenge in complex disease research is that different disease cases can be caused by different, and often numerous, genetic perturbations. For instance, autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are highly heritable, yet their underlying genetic causes remain largely elusive, complicated by the role of rare genetic variations and significant phenotypic heterogeneity among patients. This same heterogeneity is present in cancer, diabetes, and coronary artery disease [15].

The network medicine perspective posits that the cellular system is modular. Rather than individual genes, it is the perturbation of groups of related and interconnected genes—functional modules or subnetworks—that leads to disease phenotypes. The observation that different genetic causes can result in similar disease phenotypes suggests that these disparate causes ultimately dys-regulate the same core component of the cellular system. Therefore, the focus of research has shifted from seeking single culprit genes to identifying dysregulated network modules [15]. This approach is crucial for elucidating the pathogenesis of diseases like Alzheimer's, where multiscale proteomic network models have revealed key driver proteins within glia-neuron interaction subnetworks that are strongly associated with disease progression [16].

Fundamentals of Biological Networks

To identify disease modules, one must first construct the interactome—the comprehensive map of molecular interactions within a cell. These networks form the scaffold upon which disease-associated modules are discovered.

Physical Interaction Networks

Physical interaction networks map direct physical contacts between biomolecules, most commonly proteins. The nodes represent molecules, and the edges represent interactions, which are typically undirected for protein-protein binding [15].

- Experimental Methods: High-throughput techniques are the primary source for building these networks.

- Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H): Detects pairwise protein-protein interactions.

- Tandem Affinity Purification coupled to Mass Spectrometry (TAP-MS): Identifies physical interactions among groups of proteins within complexes.

- Considerations: Networks derived from different technologies can have distinct topological properties. A known limitation is the presence of both false positives (non-functional interactions) and false negatives (missing true interactions), leading to concerns about noise and incompleteness [15].

Functional Interaction Networks

Functional networks connect genes or proteins that work together to perform a specific biological function, even if they do not physically interact. These networks often represent regulatory or cooperative relationships [15].

- Co-expression Networks: Built by calculating correlation coefficients or mutual information between gene expression profiles across diverse experimental conditions. Genes with similar expression patterns are inferred to be functionally related.

- Regulatory Networks: Reconstruct causal regulatory relationships using algorithms like:

- ARACNE and SPACE: Identify interactions based on the mutual information between a transcription factor and its target genes.

- Bayesian Networks: Model conditional dependencies between expression levels to represent causal relations.

- Integrated Networks: Combine multiple data types (e.g., Gene Ontology annotations, genetic interactions, physical interactions) to create more comprehensive and accurate functional networks for organisms like human, mouse, and fly [15].

Network Topology and Modularity

Biological networks are not random; they possess characteristic topological properties. A key feature is the scale-free property, where the node degree distribution follows a power law. This means a few highly connected nodes (hubs) coexist with many nodes that have few connections. These hubs often play critical roles in biological processes and are related to the network's modularity—the organization of nodes into densely connected subgroups [15].

A functional module is an entity composed of many interacting molecules whose function is separable from other modules. The identification of these densely connected subgraphs or clusters from large-scale interaction networks is a fundamental step in moving from a whole-network view to a tractable, functional understanding of cellular processes [15].

Methodologies for Module Identification

The process of identifying modules, also known as community detection or graph clustering, has been the subject of extensive algorithmic development. A comprehensive assessment was provided by the Disease Module Identification DREAM Challenge, which benchmarked 75 methods on their ability to identify trait-associated modules [17].

Algorithmic Classes and Top Performers

The DREAM Challenge grouped module identification methods into several broad categories. The top-performing methods from the challenge are listed in the table below, demonstrating that no single approach is inherently superior, but performance depends on the specifics of the algorithm and its resolution-setting strategy [17].

Table 1: Top-Performing Module Identification Methods from the DREAM Challenge [17]

| Method ID | Algorithm Category | Key Algorithmic Principle |

|---|---|---|

| K1 | Kernel Clustering | Novel kernel approach using a diffusion-based distance metric and spectral clustering. |

| M1 | Modularity Optimization | Extends modularity optimization methods with a resistance parameter to control granularity. |

| R1 | Random-walk-based | Uses Markov clustering with locally adaptive granularity to balance module sizes. |

Practical Workflow and Benchmarking

The standard workflow involves applying these algorithms to molecular networks to decompose them into non-overlapping modules of genes or proteins. The DREAM Challenge established a robust, biologically interpretable framework for evaluating predicted modules by testing their association with complex traits and diseases using a large collection of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS). Modules that significantly associate with traits are considered biologically relevant [17].

Key findings from the challenge include:

- Complementarity: Different high-performing methods often identify distinct, complementary trait-associated modules, rather than converging on the same set. This suggests that using multiple methods can provide a more comprehensive view.

- Network Relevance: The type of network used significantly impacts the results. Co-expression and protein-protein interaction networks yielded the highest absolute number of trait modules, while signaling networks were the most enriched for trait modules relative to their size.

- Granularity: There is no single optimal module size or number; effective modules can be found at varying levels of granularity [17].

The following diagram illustrates the overall workflow for disease module identification and validation, from data integration to biological insight.

Workflow for Identifying Disease Modules

Experimental Protocols and Validation

The transition from computational prediction to biological validation is critical. The following section outlines a detailed protocol for validating a predicted disease module and its key drivers, drawing from a recent study on Alzheimer's disease [16].

Protocol: Key Driver Protein (KDP) Validation in Alzheimer's Disease

This protocol describes the experimental validation of AHNAK, a top key driver protein identified in a glia-neuron subnetwork associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) [16].

- Objective: To functionally validate the computational prediction that AHNAK is a key regulator of AD-related pathologies, specifically phosphorylated Tau (pTau) and Amyloid-beta (Aβ) levels.

- Experimental System: Human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived models of AD.

Materials:

- Item: Human iPSCs from healthy donors and AD patients.

- Function: Provides a physiologically relevant human neuronal model system.

- Item: Lentiviral vectors encoding shRNAs targeting AHNAK.

- Function: Mediates stable knockdown of the target gene AHNAK in iPSC-derived cells.

- Item: Antibodies for AHNAK, pTau (e.g., AT8), and Aβ.

- Function: Enable detection and quantification of protein levels via Western Blot and Immunocytochemistry.

- Item: ELISA kits for Aβ40/42.

- Function: Allows precise quantification of Aβ peptide levels in cell culture supernatants.

Procedure:

- Differentiation and Culture: Differentiate control and AD iPSCs into cortical neurons or glial cells using established protocols.

- Gene Knockdown: Transduce the iPSC-derived cultures with lentiviral particles containing AHNAK-targeting shRNAs or a non-targeting control shRNA.

- Efficiency Check: Harvest a subset of cells 96 hours post-transduction and perform Western Blot analysis to confirm the downregulation of AHNAK protein.

- Phenotypic Assessment:

- pTau Measurement: Analyze cell lysates by Western Blot using pTau-specific antibodies. Quantify band intensity normalized to total Tau and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH).

- Aβ Measurement: Collect cell culture media. Quantify levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides using specific ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Analysis: Perform statistical comparisons (e.g., unpaired t-test) between the AHNAK-knockdown group and the control group to determine if the reduction in AHNAK leads to a significant decrease in pTau and Aβ levels.

Expected Outcome: Successful validation would show that downregulation of the astrocytic driver AHNAK significantly reduces pTau and Aβ levels, confirming its role as a key regulator in AD pathogenesis and positioning it as a potential therapeutic target [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and resources essential for research in the field of network medicine and disease module validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Disease Module Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction Databases (e.g., STRING, InWeb) | Provide the foundational physical interaction data to construct molecular networks for module identification [17]. |

| Gene Co-expression Networks | Offer functional interaction data derived from large-scale gene expression datasets (e.g., from GEO), linking genes with correlated expression patterns [15] [17]. |

| Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Data | Serves as an independent data source for validating the biological and clinical relevance of predicted modules by testing for trait associations [17]. |

| Human iPSC-derived Disease Models | Provide a physiologically relevant, human-based experimental system for functionally validating key driver genes and proteins identified in disease modules [16]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 / shRNA Knockdown Systems | Enable targeted genetic perturbation (knockout or knockdown) of predicted key driver proteins to assess their functional impact on disease-related phenotypes [16]. |

Advanced Concepts: From Modules to Therapeutics

Refining the initial module identification is a crucial step. Key Driver Analysis (KDA) is used to pinpoint the most influential nodes within a disease module. These key driver proteins (KDPs) are highly connected genes that occupy central positions and are hypothesized to regulate the activity of the entire module. Targeting KDPs, therefore, offers a more effective therapeutic strategy than targeting peripheral components [16].

The field is now moving towards more sophisticated, multiscale network models. Future challenges and opportunities lie in incorporating more realistic assumptions about biological units and their interactions across multiple scales, from molecular to organismal. The integration of machine learning and statistical physics with network medicine is poised to further refine our understanding of disease networks and accelerate the development of targeted therapies [3]. The following diagram illustrates the causal inference process that can lead from a correlated module to a validated key driver.

From Correlation to Causation in a Disease Module

In the intricate map of cellular function, proteins do not act in isolation but rather form complex protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks that orchestrate biological processes. Within these networks, certain proteins emerge as critical players: hubs, characterized by their high number of interactions (degree centrality), and bottlenecks, identified by their strategic positions on many shortest paths (betweenness centrality). These proteins constitute the architectural pillars of cellular organization, and their disruption is frequently implicated in disease mechanisms. The integration of network biology with disease research has revealed that understanding these critical nodes provides unprecedented insights into complex disease mechanisms, from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders, and offers novel avenues for therapeutic intervention [18] [19].

Contemporary research has established that hubs and bottlenecks are not merely topological curiosities but represent functional master regulators within the cell. Analysis of degree centrality in conjunction with betweenness centrality in human PPI networks reveals three distinct categories of centrally important proteins: (1) proteins with high degree and betweenness (hub-bottlenecks, denoted as MX), (2) proteins with high betweenness but low degree (non-hub-bottlenecks/pure bottlenecks, denoted as PB), and (3) proteins with high degree but low betweenness (hub-non-bottlenecks/pure hubs, denoted as PH). This trichotomy forms the foundation for understanding how topological roles correlate with molecular function and disease association [18].

Identification and Characterization Methodologies

Computational Framework for Protein Classification

The systematic identification of hub and bottleneck proteins requires a robust computational pipeline that integrates network data with statistical analysis. The following methodology, adapted from large-scale studies of human interactomes, provides a reproducible framework for classifying critical nodes [20] [18].

Step 1: Network Construction

- Source physical PPIs from curated databases (e.g., HIPPIE, HuRI, BioGRID, DIP, HPRD, IntAct)

- Construct a non-redundant interaction set

- Extract the giant component for analysis (typically encompassing >16,000 proteins and >286,000 interactions)

Step 2: Centrality Calculation

- Calculate degree centrality for each node (number of direct connections)

- Calculate betweenness centrality for each node (fraction of shortest paths passing through the node)

- Normalize centrality measures to enable cross-network comparisons

Step 3: Classification

- Designate hubs as proteins in the top 20th percentile of degree distribution (typically degree ≥ 50)

- Designate bottlenecks as proteins in the top 20th percentile of betweenness distribution

- Categorize proteins into four distinct classes:

- Hub-bottlenecks (MX): High degree, high betweenness

- Pure hubs (PH): High degree, low betweenness

- Pure bottlenecks (PB): Low degree, high betweenness

- Non-hub-non-bottlenecks: Low degree, low betweenness

Step 4: Statistical Validation

- Perform permutation tests to validate classifications

- Assess robustness through network subsampling

- Correlate topological categories with functional annotations

Table 1: Centrality Measures for Protein Classification

| Category | Abbreviation | Degree Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | Prevalence in Human Interactome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hub-bottleneck | MX | High (top 20%) | High (top 20%) | Significant overlap |

| Pure hub | PH | High (top 20%) | Low (bottom 80%) | ~15% of high-centrality proteins |

| Pure bottleneck | PB | Low (bottom 80%) | High (top 20%) | ~20% of high-centrality proteins |

| Non-hub-non-bottleneck | NHNB | Low (bottom 80%) | Low (bottom 80%) | Majority of proteins |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions require experimental validation to confirm biological significance. The following methodologies provide robust mechanisms for verifying the functional importance of candidate hub and bottleneck proteins:

Essentiality Screening

- Implement RNA interference (RNAi) or CRISPR-Cas9 screens

- Measure viability impact following protein disruption

- Validate using gene knockout studies in model organisms

- Compare essentiality rates across topological categories [19]

Expression Correlation Analysis

- Calculate Pearson correlation coefficients of expression profiles with direct interaction partners

- Utilize microarray or RNA-seq data across multiple conditions

- Lower co-expression suggests dynamic, condition-specific interactions [19]

Pathogen Interaction Profiling

- Screen against viral and bacterial protein libraries

- Use yeast two-hybrid systems for interaction discovery

- Validate with co-immunoprecipitation assays [18]

Structural Characterization

- Assess intrinsic disorder content using IUPred or similar tools

- Analyze domain architecture with Pfam/InterPro

- Correlate structural features with topological role [18]

Diagram 1: Workflow for Identifying and Validating Hub/Bottleneck Proteins

Functional Dichotomy and Molecular Properties

The topological classification of proteins into hub-bottlenecks, pure hubs, and pure bottlenecks reflects profound functional differences validated at the molecular level. Statistical analyses reveal that each category possesses distinct "molecular markers" - characteristic properties that define their biological roles and potential disease associations [18].

Distinct Molecular Signatures Across Categories

Table 2: Molecular Properties of Hub and Bottleneck Protein Categories

| Molecular Property | Hub-Bottlenecks (MX) | Pure Bottlenecks (PB) | Pure Hubs (PH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Features | Conformationally versatile, intrinsic disorder | Structured, stable folds | Structurally versatile |

| Essentiality | High essentiality (72%) | Moderate essentiality | High essentiality (68%) |

| Pathogen Targeting | High susceptibility to viral/bacterial interaction | Moderate susceptibility | Low susceptibility |

| Evolutionary Rate | Slow evolution (high constraint) | Intermediate evolution | Slow evolution |

| Disease Association | Enriched with diverse disease genes | Cancer-related, approved drug targets | Limited disease association |

| Cellular Functions | Protein stabilization, phosphorylation, mRNA splicing | Cell-cell signaling, communication | Transcription, replication, housekeeping |

| Expression Correlation | Low co-expression with partners | Variable co-expression | High co-expression with partners |

Biological Implications of Topological Roles

The molecular signatures of each protein category illuminate their specialized biological functions:

Hub-bottlenecks (MX) serve as master integrators within cellular networks. Their conformational versatility, enabled by higher intrinsic disorder, allows them to interact with multiple partners and participate in diverse pathways simultaneously. These proteins function as critical connectors between different functional modules, explaining their essential nature and why pathogens frequently target them to hijack cellular processes. Their involvement in key processes like phosphorylation and mRNA splicing places them at the crossroads of signaling and regulatory pathways [18].

Pure bottlenecks (PB) act as specialized communicators between network modules. Despite having fewer interactions, their strategic positioning on critical paths makes them ideal regulators of information flow. Their enrichment among approved drug targets underscores their pharmacological importance, particularly in diseases like cancer where cell-cell signaling is disrupted. Unlike hubs, pure bottlenecks often exhibit condition-specific importance, functioning as gatekeepers that control access between functional modules [18] [19].

Pure hubs (PH) function as structural organizers within functional modules. Their high co-expression with interaction partners suggests coordinated production and assembly into complexes. These proteins typically serve housekeeping functions related to transcription and replication, forming the stable core of cellular machinery. While essential, their limited connectivity to diverse modules reduces their susceptibility to pathogen exploitation compared to hub-bottlenecks [18].

Role in Disease Mechanisms and Network Medicine

The disruption of hub and bottleneck proteins features prominently in human disease pathogenesis. Network medicine approaches have revealed that these proteins represent vulnerable points whose dysfunction can cascade through cellular systems, leading to pathological states.

Network Topology and Disease Association

Disease-associated genes are not randomly distributed in interactome networks but significantly cluster in specific neighborhoods. Hub-bottlenecks are particularly enriched among disease genes, with studies demonstrating their overexpression in various cancers, neurodegenerative conditions, and metabolic disorders. For instance, in alcohol use disorder (AUD), multi-level biological network analysis of the prefrontal cortex identified key bottleneck proteins like GAPDH and ACTB as central to the pathological rewiring of molecular networks [21].

Pure bottlenecks serve as critical bridges whose disruption can fragment network connectivity. This property explains their strong association with cancer progression, where mutations in bottleneck proteins can disconnect entire functional modules necessary for maintaining cellular homeostasis. Their position as inter-modular connectors makes them susceptible to causing system-wide failures when compromised [18] [19].

Pathogen Exploitation of Network Topology

Pathogens have evolutionarily optimized their invasion strategies to target hub and bottleneck proteins. Comprehensive studies reveal that viral and bacterial pathogens disproportionately target hub-bottlenecks, employing them as entry points to hijack cellular processes. This exploitation strategy efficiently maximizes disruption with minimal pathogen investment, as compromising a single hub-bottleneck can simultaneously affect multiple pathways [18].

Diagram 2: Disease Mechanisms Through Network Disruption

Experimental and Therapeutic Applications

Research Reagent Solutions for Network Pharmacology

The systematic study of hub and bottleneck proteins requires specialized research tools and databases. The following table catalogs essential resources for experimental investigation and therapeutic development.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hub and Bottleneck Protein Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| PPI Databases | HIPPIE, HuRI, BioGRID, DIP, HPRD, IntAct | Source experimentally validated protein interactions for network construction |

| Centrality Analysis Tools | Cytoscape with NetworkAnalyzer, igraph, CentiScaPe | Calculate degree, betweenness, and other centrality measures |

| Functional Annotation | Gene Ontology (GO), Metascape, KEGG | Functional enrichment analysis of hub/bottleneck proteins |

| Essentiality Screening | CRISPR libraries, RNAi collections | Experimentally validate essentiality predictions |

| Drug-Target Databases | DrugBank, ChEMBL, Therapeutic Target Database | Identify existing drugs targeting hub/bottleneck proteins |

| Pathogen Interaction Data | HPIDB, VirHostNet | Study pathogen targeting of network components |

| Structural Biology Tools | IUPred, PDB, AlphaFold | Analyze structural properties and intrinsic disorder |

Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Targeting

Network pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving from single-target approaches to strategies that account for cellular connectivity. The distinct properties of hub and bottleneck proteins offer unique opportunities for therapeutic intervention:

Hub-bottlenecks as Master Switches Hub-bottlenecks represent powerful targets for diseases requiring system-level intervention. Their central positioning allows modulation of multiple pathways simultaneously. However, their essentiality and conformational versatility present challenges for drug development. Successful targeting requires allosteric modulation or partial inhibition to avoid excessive toxicity. For example, in alcohol use disorder, bioinformatic analysis has identified artenimol and quercetin as candidate drugs capable of interacting with key bottleneck proteins in the prefrontal cortex, potentially restoring network homeostasis disrupted by alcohol [21].

Pure Bottlenecks as Precision Targets Pure bottlenecks offer exceptional opportunities for targeted therapies with reduced side effects. Their inter-modular positioning enables specific control over communication between functional modules without disrupting the modules themselves. This property explains their enrichment among approved drug targets. In cancer therapeutics, targeting pure bottlenecks in signaling pathways can achieve pathway-specific effects while sparing related cellular processes [18].

Network-Based Drug Repurposing The analysis of existing drug targets within the context of network topology enables systematic drug repurposing. By mapping approved drugs to hub and bottleneck proteins, researchers can identify new therapeutic applications for existing compounds. This approach leverages known safety profiles while applying network-aware therapeutic strategies [21] [18].

Experimental Protocols for Therapeutic Development

Target Validation Pipeline

- Computational Prioritization: Identify candidate hub/bottleneck proteins associated with disease pathways

- Expression Profiling: Quantify target expression in disease-relevant tissues using qPCR or RNA-seq

- Functional Screening: Implement high-content CRISPR or RNAi screens to assess phenotypic impact

- Interaction Mapping: Validate protein interactions using yeast two-hybrid or co-immunoprecipitation

- Therapeutic Assessment: Test candidate compounds in relevant disease models

Compound Screening Methodology

- Utilize structure-based drug design for targets with known structures

- Implement network-based virtual screening to identify multi-target compounds

- Validate hits in phenotypic assays measuring network-level effects

- Optimize lead compounds for selective modulation rather than complete inhibition

The integration of network topology with molecular pharmacology enables a new generation of therapeutic strategies that acknowledge the inherent connectivity of biological systems. By targeting the critical nodes that underlie network integrity in disease states, researchers can develop more effective treatments for complex disorders that have proven resistant to conventional single-target approaches.

The fundamental challenge in modern genomics is bridging the gap between genetic variants (genotype) and observable clinical traits (phenotype). For complex diseases—such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), coronary artery disease (CAD), or holoprosencephaly (HPE)—this relationship is seldom linear. Instead, phenotypes arise from disruptions within intricate networks of molecular interactions [22]. A genetic mutation acts as a perturbation that propagates through these biological networks, altering the activity of interconnected proteins, RNAs, and metabolites, ultimately shifting cellular and tissue states toward disease [22]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to understanding and investigating how perturbations to biological networks drive disease pathogenesis, framing this within the broader thesis that network medicine is essential for decoding complex disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic strategies.

Core Conceptual Framework: Networks as the Substrate for Perturbation

Defining Network Components and Perturbation Types

Biological networks model relationships between molecular entities. Nodes typically represent genes, proteins, or metabolites, while edges represent physical interactions, regulatory relationships, or functional associations [22]. Disease-causing perturbations can occur at multiple scales, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Scales of Genotypic Perturbations and Their Network Impact

| Perturbation Scale | Example Alteration | Primary Network Impact | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Variant | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP), rare variant [22] | Alters function/stability of a node (protein) | Disrupts all edges (interactions) connected to that node. |

| Structural Variant | Copy Number Variation (CNV), translocation [23] | Alters gene dosage, creates fusion proteins | Adds/removes nodes, creates novel, aberrant edges. |

| Epigenetic Alteration | DNA methylation, histone modification [24] | Modifies expression level of a node | Rewires regulatory edges, changing network activity state. |

| Post-translational Modification | Phosphorylation, acetylation | Changes activity state of a protein node | Alters the strength or specificity of its interaction edges. |

From Perturbed Node to Disease Module

A key principle is that disease-associated genes/proteins are not randomly scattered in the interactome but cluster into interconnected neighborhoods known as disease modules [22] [25]. A genetic perturbation within or near such a module can destabilize the entire functional unit. For example, genes associated with specific hallmarks of aging (e.g., cellular senescence, genomic instability) form distinct, yet interconnected, modules within the human protein-protein interaction (PPI) network [25]. Similarly, in holoprosencephaly, mutations disrupt key nodes in signaling pathways like SHH, NODAL, and WNT/PCP, which form functional networks guiding forebrain development [23].

Methodological Toolkit: Mapping and Analyzing Network Perturbations

Experimental Protocols for Network Construction and Perturbation Analysis

Protocol 1: Identifying Causal Genes via Network-Mediated Inference Objective: To move beyond differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and identify upstream causal drivers within a co-expression network. Input: Transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq) from disease and control tissues. Steps: 1. Network Construction: Perform Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to identify modules of highly correlated genes [26]. 2. Module-Phenotype Correlation: Correlate module eigengenes with the clinical phenotype (e.g., disease status, severity score). 3. Causal Mediation Analysis: For significant modules, apply bidirectional statistical mediation models (e.g., CWGCNA framework) [26]. This tests whether the relationship between the phenotype and individual gene expression is mediated by the module activity, and vice versa, adjusting for confounders like age. 4. Validation: Validate candidate causal genes using independent cohorts and spatial transcriptomics to confirm localization in disease niches [26]. Output: A list of high-confidence causal genes that are potential therapeutic targets, as demonstrated in IPF research where 145 causal mediators were identified [26].

Protocol 2: Network-Based Drug Repurposing via Proximity Analysis Objective: To computationally predict existing drugs that can counteract a disease network state. Input: A defined disease module (set of genes); a PPI network; a drug-target database (e.g., DrugBank). Steps: 1. Define Disease Module: Compile disease-associated genes from GWAS, sequencing studies, or causal analyses (Protocol 1). Map them onto the interactome and extract the largest connected component as the disease module [25]. 2. Calculate Network Proximity: For each drug with known protein targets, compute the network proximity between the drug's target set and the disease module. Common metrics measure the average shortest path distance between the two sets [25]. 3. Assess Significance: Generate a null distribution by randomly selecting gene sets of the same size and degree distribution, calculating a z-score for the observed proximity. 4. Integrate Transcriptomic Directionality: Calculate a metric like pAGE to determine if the drug's gene expression signature reverses or reinforces the disease-associated expression changes [25]. Output: A ranked list of drug repurposing candidates with significant network proximity and a reversing transcriptional signature.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Perturbation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function & Utility in Network Studies | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| LINCS L1000 Database | Provides massive-scale gene expression signatures for chemical and genetic perturbations across cell lines. Used as a reference to connect drug signatures to disease states. [27] [28] | Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures |

| CMap (Connectivity Map) | A foundational resource of drug-induced gene expression profiles. Enables signature-based drug repurposing by searching for inverse correlations with disease signatures. [27] [28] | Broad Institute |

| Human Interactomes (PPI Networks) | Scaffolds for mapping disease genes and calculating network properties. Essential for module detection and proximity analysis. | BioGRID [27], STRING, HIPPIE |

| CRISPR Knockout Libraries | Enable systematic genetic perturbations at scale. Coupled with single-cell RNA-seq (Perturb-seq), they allow mapping of genetic interactions and network rewiring. [29] | Various pooled libraries |

| Pathway Databases | Provide canonical interaction knowledge for building focused network models and interpreting network analysis results. | KEGG [28], Reactome |

| Drug-Target Databases | Catalog known and predicted interactions between drugs/compounds and their protein targets. Critical for network pharmacology. | DrugBank [25], DGIdb |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | Allow validation of network-predicted key genes and their activity within the spatial architecture of diseased tissue. [26] | 10x Genomics Visium, Nanostring GeoMx |

Advanced Computational Models: Predicting and Reversing Perturbations

Quantitative Modeling of Pathway Perturbation Dynamics

The PathPertDrug framework exemplifies a move beyond static network mapping to dynamic perturbation modeling [28]. Method: 1. Integrate disease transcriptomes, drug-induced expression profiles from CMAP, and pathway topology from KEGG. 2. Quantify a Pathway Perturbation Score that integrates the magnitude of gene expression change (fold-change) and the topological importance of the dysregulated genes within the pathway. 3. Calculate a Functional Reverse Score by assessing the antagonism between drug-induced and disease-associated pathway perturbation states (activation vs. inhibition). 4. Rank drugs by their ability to reverse disease-perturbed pathways. Performance: This method showed superior accuracy (median AUROC 0.62 vs. 0.42-0.53 in benchmarks) in predicting cancer drug associations [28].

Inverse Design of Perturbagens with Graph Neural Networks

A major innovation is solving the inverse problem: directly predicting which combinatorial perturbations will shift a diseased network state to a healthy one. The PDGrapher model embodies this approach [27]. Architecture: 1. Input: A diseased cell state (gene expression profile) and a desired healthy state. A proxy causal graph (PPI or Gene Regulatory Network). 2. Model: A causally inspired Graph Neural Network (GNN) learns to represent the structural equations defining gene relationships. 3. Output: A predicted perturbagen—an optimal set of therapeutic targets whose intervention is predicted to drive the state transition. Advantage: Trains up to 25x faster than methods that simulate all possible perturbations, enabling scalable combinatorial target discovery [27].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Diagram: From Genetic Perturbation to Phenotypic Outcome via Network Modules

Title: Network Propagation of a Genetic Variant to a Disease Phenotype

Diagram: PDGrapher Model for Inverse Perturbagen Prediction

Title: Inverse Design of Therapeutic Perturbations with PDGrapher

Diagram: Integrated Protocol for Causal Gene & Drug Discovery

Title: Workflow from Omics Data to Network-Based Drug Repurposing

The thesis that biological networks are central to complex disease mechanisms is fundamentally reshaping translational research. The progression from mapping static disease-associated networks to dynamically modeling perturbations—and now to inversely designing corrective interventions—represents a paradigm shift [27] [28] [25]. This network perturbation-centric approach addresses the polygenic and heterogeneous nature of complex diseases more effectively than the "one gene, one drug" model. By providing the methodologies, tools, and conceptual frameworks detailed in this guide, researchers are equipped to not only understand how genotype leads to phenotype but also to strategically identify points within the network where therapeutic intervention can most effectively restore health.

From Data to Mechanisms: Methodological Approaches and Applications in Network Analysis

Leveraging Single-Cell Multi-omics to Construct Heterogeneous Regulatory Landscapes (HRL)

The Heterogeneous Regulatory Landscape (HRL) represents a comprehensive mapping of the complex molecular interactions that define cellular identity and function within tissues. Single-cell multi-omics technologies have revolutionized our ability to deconstruct these landscapes by simultaneously measuring multiple molecular layers—including the transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome—within individual cells. This approach has revealed unprecedented dimensions of cellular heterogeneity in complex diseases, moving beyond the limitations of bulk sequencing which averages signals across diverse cell populations [30]. The construction of HRLs is fundamentally transforming complex disease research by providing a high-resolution view of the regulatory networks and cellular ecosystems that underlie disease pathogenesis, progression, and therapeutic resistance.

The biological imperative for HRL construction stems from the recognition that complex diseases including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions are driven by intricate interactions between diverse cell types, each possessing distinct molecular profiles. Traditional bulk analyses obscured these critical differences, masking rare but functionally important cellular subpopulations that may drive disease processes or therapeutic resistance [30] [31]. By integrating multi-omic measurements at single-cell resolution, researchers can now reconstruct the complete regulatory architecture of tissues, revealing how genetic variation, epigenetic modifications, transcriptional programs, and protein expression interact to determine cellular states in health and disease. This integrated perspective is particularly valuable for understanding the molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer, where heterogeneous tumor cell populations evolve diverse survival strategies through distinct regulatory pathways [32] [33].

Technological Foundations for HRL Construction

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Profiling Technologies

The construction of high-resolution HRLs relies on advanced experimental technologies capable of capturing multiple molecular modalities from individual cells. These platforms can be broadly categorized into three approaches based on their cell barcoding strategies: plate-based methods, droplet-based systems, and combinatorial indexing techniques [31]. Each offers distinct advantages for specific research applications in HRL development.

Table 1: Single-Cell Multi-Omic Profiling Technologies for HRL Construction

| Technology Type | Example Methods | Throughput | Key Applications in HRL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-based | scDam&T-seq, scCAT-seq | Low | In-depth characterization of specific cell populations |

| Droplet-based | ASTAR-seq, SNARE-seq, 10X Genomics | High | Large-scale atlas construction of heterogeneous tissues |

| Combinatorial Indexing | Paired-seq, sci-CAR, SHARE-seq | Very High | Developmental trajectories and rare cell population analysis |

Droplet-based systems, particularly commercial platforms from 10X Genomics, have become widely adopted for HRL studies due to their ability to profile tens of thousands of cells simultaneously, making them ideal for capturing the full complexity of heterogeneous tissues [30]. Meanwhile, combinatorial indexing approaches like SHARE-seq offer exceptional scalability, enabling the profiling of massive cell numbers while maintaining multi-omic resolution [31]. The strategic selection of appropriate profiling technology represents the critical first step in HRL construction, balancing throughput, resolution, and molecular coverage based on the specific biological question under investigation.

Molecular Modalities in HRL Construction

A comprehensive HRL integrates multiple molecular modalities, each providing unique insights into different layers of regulatory control:

- Genomics: DNA sequencing reveals somatic mutations, copy number variations, and structural variants that form the genetic foundation of cellular heterogeneity, particularly important in cancer HRLs for understanding clonal architecture [30].

- Epigenomics: Assays such as scATAC-seq map chromatin accessibility landscapes, revealing cell-type-specific regulatory elements and transcription factor binding sites that control gene expression programs [32] [34].

- Transcriptomics: scRNA-seq profiles gene expression patterns that define cellular states and functional activities, serving as a central integrator of various regulatory signals within the HRL [32] [33].

- Proteomics: Measurement of protein abundances and post-translational modifications provides critical functional readouts that often correlate poorly with mRNA levels due to complex post-transcriptional regulation [35].