Decoding Autism Heterogeneity: A Multimodal Neuroimaging Comparison of ALFF, fALFF, and GMV Across ASD Subtypes

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF), fractional ALFF (fALFF), and Gray Matter Volume (GMV) as critical biomarkers for differentiating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) subtypes.

Decoding Autism Heterogeneity: A Multimodal Neuroimaging Comparison of ALFF, fALFF, and GMV Across ASD Subtypes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF), fractional ALFF (fALFF), and Gray Matter Volume (GMV) as critical biomarkers for differentiating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) subtypes. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the neurobiological foundations of ASD heterogeneity across traditional diagnostic categories including Autistic Disorder, Asperger's, and PDD-NOS. Through methodological examination of neuroimaging techniques, troubleshooting of analytical approaches, and validation of findings across independent cohorts, we establish a framework for precision medicine in autism research. The evidence synthesized from recent studies demonstrates that distinct neural signatures captured by functional and structural metrics can stratify ASD populations, potentially guiding targeted therapeutic development and biomarker discovery.

The Neurobiological Landscape of Autism Subtypes: Establishing Functional and Structural Foundations

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents one of the most heterogeneous neurodevelopmental conditions, characterized by immense variability in behavioral presentation, underlying genetics, and neural circuitry. This heterogeneity has long posed a significant challenge for researchers seeking to understand its biological mechanisms and for clinicians developing targeted interventions. The integration of neuroimaging techniques with genetic and phenotypic data has emerged as a powerful approach to deconstruct this complexity. Among the most informative neuroimaging measures are Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF), fractional ALFF (fALFF), and Gray Matter Volume (GMV), which provide complementary windows into brain function and structure. This review synthesizes current evidence on how these multimodal biomarkers distinguish ASD subtypes, offering a framework for precision medicine approaches in autism research and therapeutic development.

Neuroimaging Biomarkers in ASD Subtyping: Technical Foundations

ALFF measures the intensity of spontaneous neural activity in the resting brain by quantifying the power of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals within the low-frequency range (0.01-0.08 Hz). It reflects regional spontaneous neuronal activity and has been valuable for identifying atypical brain function in ASD.

fALFF represents the ratio of low-frequency power to the entire frequency range, effectively improving the specificity of ALFF by suppressing nonspecific signal components from non-brain regions. This measure offers enhanced sensitivity for detecting functional abnormalities in ASD.

GMV quantifies the volume of gray matter tissue through structural MRI, providing insights into cortical thickness, surface area, and overall brain morphology. GMV alterations in ASD may reflect disturbances in neurodevelopmental processes such as synaptic pruning, neuronal migration, or cortical organization.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Primary Neuroimaging Biomarkers in ASD Research

| Biomarker | Biological Significance | Analysis Approach | Key Applications in ASD |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALFF | Intensity of spontaneous neural activity | Time-series frequency analysis | Identifying regions of hyper/hypoactivation in resting state |

| fALFF | Specificity of low-frequency fluctuations | Ratio of low-frequency to entire frequency power | Differentiating true neural activity from physiological noise |

| GMV | Regional brain tissue volume | Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) | Mapping structural abnormalities and developmental trajectories |

Experiment 1: Genetic-Phenotypic Stratification of ASD Subtypes

Methodology

A groundbreaking 2025 study analyzed data from 5,392 individuals with ASD from the SPARK cohort, employing a generative finite mixture model (GFMM) to identify subtypes based on 239 phenotypic features [1] [2]. The model incorporated diverse data types (continuous, binary, categorical) from standardized diagnostic instruments including the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R), and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Validation was performed in an independent cohort from the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) with 861 individuals [1].

Results: Four Distinct ASD Subtypes

The analysis revealed four clinically and biologically distinct ASD subtypes:

Social/Behavioral Challenges (37%): Characterized by core autism features plus co-occurring ADHD, anxiety, and mood disorders, without developmental delays. Genetic analysis revealed mutations in genes active predominantly during postnatal development [1] [3].

Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%): Displayed developmental delays and intellectual disability but fewer co-occurring psychiatric conditions. This group showed enrichment of rare inherited genetic variants affecting prenatal neurodevelopmental pathways [1] [4].

Moderate Challenges (34%): Exhibited milder manifestations across all core ASD domains without developmental delays or significant psychiatric comorbidities [2] [3].

Broadly Affected (10%): Demonstrated severe impairments across all domains including developmental delays and psychiatric conditions. This subtype showed the highest burden of damaging de novo mutations [1] [3].

Table 2: Characteristic Profiles of Genetic ASD Subtypes

| Subtype | Core Features | Co-occurring Conditions | Developmental Trajectory | Genetic Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social/Behavioral Challenges | Social deficits, repetitive behaviors | ADHD, anxiety, depression | Typical milestone achievement | Postnatal gene expression |

| Mixed ASD with DD | Social communication deficits, RRB | Intellectual disability, language delay | Delayed milestones | Rare inherited variants |

| Moderate Challenges | Mild core symptoms | Minimal comorbidities | Typical development | Heterogeneous |

| Broadly Affected | Severe core symptoms | Multiple psychiatric conditions | Significant delays | High de novo mutation burden |

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Programs

Each subtype demonstrated distinct biological signatures with minimal pathway overlap [2] [3]. The Social/Behavioral subtype implicated neuronal action potential and synaptic signaling pathways, while the Mixed ASD with DD subtype involved chromatin organization and transcriptional regulation. The Broadly Affected subtype showed disruptions across multiple fundamental cellular processes including metabolic regulation and protein synthesis [3].

Experiment 2: Multimodal Neuroimaging of Traditional ASD Subtypes

Methodology

A 2020 study investigated neurobiological differences among traditional DSM-IV-TR ASD subtypes (Autistic Disorder, Asperger's, and PDD-NOS) using multimodal fusion of fALFF and GMV data [5]. The analysis included 229 males with ASD from ABIDE II as a discovery cohort and 400 from ABIDE I for replication. A key innovation was the use of supervised multimodal fusion incorporating ADOS scores as a reference to identify brain networks associated with symptom severity [5].

Results: Subtype-Specific Neural Signatures

The study revealed both common and distinct neurobiological patterns across traditional subtypes:

Common Neural Substrate: All three subtypes shared abnormalities in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and superior/middle temporal cortex, suggesting a universal neural basis for core ASD social-communication deficits [5].

Subtype-Specific Functional Patterns:

- Asperger's Syndrome: Showed unique negative functional features in the putamen-parahippocampal circuit [5].

- PDD-NOS: Demonstrated distinctive fALFF patterns in the anterior cingulate cortex [5].

- Autistic Disorder: Exhibited unique thalamus-amygdala-caudate functional abnormalities [5].

Table 3: Neuroimaging Differences Across Traditional ASD Subtypes

| Brain Measure | Autistic Disorder | Asperger's Syndrome | PDD-NOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key fALFF Alterations | Thalamus-amygdala-caudate circuit | Putamen-parahippocampal circuit | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| GMV Patterns | Prefrontal and limbic-striatal reductions [5] | Temporal and frontal abnormalities | Parieto-temporal alterations |

| Social Cognition Correlates | Severe social communication deficits | Relatively preserved language | Variable social communication |

| Predictive Value for Symptoms | Predicts communication and RRB severity | Predicts social interaction scores | Predicts overall ADOS severity |

Experiment 3: Normative Modeling of Functional Connectivity Subtypes

Methodology

A 2025 study applied normative modeling to resting-state fMRI data from 1,046 participants (479 ASD, 567 typical development) from ABIDE I and II datasets [6]. The researchers characterized multilevel functional connectivity using both static functional connectivity strength (SFCS) and dynamic functional connectivity (DFCS/DFCV). Normative models based on typical development trajectories were used to quantify individual-level deviations in ASD participants, followed by clustering analyses to identify neural subtypes.

Results: Dichotomous Neural Subtypes

The analysis revealed two distinct neural subtypes despite comparable clinical presentations:

Subtype 1: Characterized by positive deviations in the occipital and cerebellar networks, coupled with negative deviations in the frontoparietal, default mode, and cingulo-opercular networks.

Subtype 2: Exhibited the inverse pattern—negative deviations in occipital and cerebellar networks with positive deviations in frontoparietal, default mode, and cingulo-opercular networks [6].

Remarkably, these neural subtypes demonstrated different gaze patterns in eye-tracking tasks, with Subtype 1 showing reduced attention to social cues and Subtype 2 displaying more typical social attention patterns [6].

Cross-Study Comparative Analysis

Methodological Considerations

The reviewed studies employed substantially different approaches to ASD subtyping. The genetic-phenotypic study [1] utilized a person-centered approach considering the full constellation of traits within individuals, while neuroimaging studies typically employed data-driven clustering of brain features. This methodological diversity enriches the field but complicates direct comparisons.

Concordance and Divergence Across Modalities

A striking finding across studies is the consistent identification of 3-4 primary ASD subtypes regardless of methodological approach. The neuroimaging studies consistently implicated frontotemporal networks, default mode network, and subcortical structures across subtypes, aligning with the social-brain network framework.

The genetic study [3] added a crucial temporal dimension by demonstrating that different subtypes involve genes active at distinct developmental periods—prenatal for developmental delay subtypes and postnatal for social-behavioral subtypes.

Table 4: Key Research Resources for ASD Subtyping Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Application in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort Datasets | SPARK (Simons Foundation) [2] [3] | Large-scale genetic-phenotypic studies with >5,000 participants |

| Cohort Datasets | ABIDE I & II [7] [6] [5] | Multi-site neuroimaging data with >1,000 ASD participants |

| Analysis Tools | Generative Finite Mixture Models [1] | Person-centered phenotypic classification |

| Analysis Tools | Normative Modeling [6] | Quantifying individual deviations from neurotypical trajectories |

| Analysis Tools | Multimodal Fusion (MCCAR + jICA) [8] | Integrating multiple neuroimaging modalities |

| Biomarkers | ALFF/fALFF [7] [9] [5] | Measuring regional spontaneous brain activity |

| Biomarkers | GMV [7] [9] [5] | Assessing structural brain abnormalities |

| Validation Approaches | Leave-One-Site-Out Cross Validation [8] | Addressing multi-site dataset variability |

The integration of ALFF, fALFF, and GMV measures with genetic and phenotypic data has substantially advanced our understanding of ASD heterogeneity. The consistent identification of biologically meaningful subtypes across independent studies and methodologies suggests we are approaching a paradigm shift in autism research—from viewing ASD as a single disorder to recognizing it as a collection of neurobiological conditions with distinct genetic underpinnings, developmental trajectories, and neural signatures.

Future research should prioritize several key areas: (1) longitudinal designs to track subtype stability across development; (2) increased ancestral diversity to ensure generalizability; (3) integration of emerging biomarkers including white matter functional activity [8]; and (4) translation of subtype knowledge into personalized interventions. The continued refinement of ASD subtyping will ultimately enable more precise diagnosis, targeted treatments, and improved outcomes for individuals across the autism spectrum.

The publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) in 2013 marked a transformative moment in the history of autism diagnosis. This revision fundamentally restructured the diagnostic classification for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), moving away from the categorical approach of the DSM-IV toward a unified, dimensional model [10] [11]. The evolution from DSM-IV to DSM-5 was driven by accumulating empirical evidence demonstrating that the previous subcategories—Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Disorder, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS)—lacked consistent validity, reliability, and stability over time [11] [12]. This nosological shift was intended to better reflect the state of scientific research by creating a single diagnostic category that consistently identifies the core features of ASD, while also aiming to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and the consistency of service eligibility [10] [13]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this diagnostic transition is critical, as it has profound implications for subject recruitment, study design, phenotypic characterization, and the interpretation of neurobiological findings, including those from ALFF (Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations), fALFF (fractional ALFF), and GMV (Gray Matter Volume) comparative studies.

Historical Evolution of Diagnostic Criteria

From Kanner to DSM-IV

The diagnostic concept of autism has undergone significant evolution since Leo Kanner's seminal 1943 description of "early infantile autism" [14]. Kanner emphasized two essential features: autism (severe problems in social interaction and connectedness from early life) and resistance to change/insistence on sameness [14]. For decades, autism was misclassified as a form of childhood schizophrenia, a misconception that persisted until the groundbreaking publication of DSM-III in 1980 [14] [12]. DSM-III established "Infantile Autism" as a distinct diagnostic category for the first time, separating it definitively from schizophrenia and requiring six specific diagnostic criteria, including onset before 30 months and specific language deficits [14] [12].

The 1987 DSM-III-R revision replaced "Infantile Autism" with "Autistic Disorder" and expanded the menu of symptoms, organizing core features into three domains of impairment: reciprocal social interaction, communication, and restricted/repetitive behaviors [11] [14]. This tripartite structure laid the groundwork for the subsequent DSM-IV. The 1994 DSM-IV classification represented the most categorical approach to autism diagnosis, introducing five distinct subtypes under the umbrella term "Pervasive Developmental Disorders" (PDDs) [11] [13]. This system included Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Disorder, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, Rett's Disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) [12]. The creation of Asperger's Disorder as a separate category was particularly notable, intended to describe individuals with social deficits and restricted interests but without significant language delays or cognitive impairment [11] [15].

Rationale for Change in DSM-5

Several converging lines of evidence necessitated the diagnostic restructuring in DSM-5. Research conducted in the decades following DSM-IV's publication revealed considerable diagnostic inconsistency across clinics and practitioners when applying the subcategories [11] [15]. The distinction between Autistic Disorder and Asperger's Disorder proved particularly problematic, with studies showing that a child's diagnosis often depended more on the specific clinic or clinician than on core symptomatic differences [11]. Furthermore, longitudinal studies demonstrated that individuals could transition between diagnostic categories over time (e.g., from Autistic Disorder to PDD-NOS), undermining the stability and validity of the discrete subtypes [11].

Advances in genetic research provided particularly compelling evidence for a spectrum approach. Studies consistently found that genetic risk factors (e.g., copy number variants) conferred susceptibility to autism spectrum disorders as a whole, rather than to specific DSM-IV subtypes [11]. For example, research on fragile X syndrome showed that affected individuals might receive diagnoses of Autistic Disorder, PDD-NOS, or other subtypes, with no clear genetic differentiation between the categories [11]. This fluidity of boundaries between categories was more consistent with a spectrum construct than with discrete, independent diagnoses with different etiologies [11].

Table: Historical Timeline of Autism in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

| Manual & Year | Diagnostic Term | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| DSM-III (1980) | Infantile Autism | First official recognition; separated from schizophrenia; onset before 30 months [14] [12] |

| DSM-III-R (1987) | Autistic Disorder | Expanded symptom list; triad of impairments: social, communication, behaviors [11] [14] |

| DSM-IV (1994) | Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) | Five subtypes: Autistic Disorder, Asperger's, CDD, Rett's, PDD-NOS [11] [12] |

| DSM-5 (2013) | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Single spectrum category; two symptom domains; addition of specifiers and severity levels [13] [15] |

Comparative Analysis: DSM-IV vs. DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Structural Changes in Diagnostic Framework

The DSM-5 introduced several fundamental structural changes to the diagnosis of autism. The most significant change was the consolidation of multiple disorders into a single diagnostic entity—Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [16] [13]. This meant the elimination of Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Disorder, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, and PDD-NOS as distinct diagnoses, subsuming them all under the ASD umbrella [12] [15]. A second major change involved the reorganization of core symptom domains from three to two. The DSM-IV domains of social interaction and communication were merged into a single domain of "social communication and social interaction," while restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests formed the second core domain [16] [13].

The DSM-5 also expanded the behavioral manifestations within the restricted/repetitive behaviors domain to include abnormalities in sensory processing, such as hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment [13] [15]. This change officially recognized a clinical feature that had long been observed but was not previously included in diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, the DSM-5 replaced the global severity approach with a dimensional severity rating system (Level 1, 2, or 3) based on the level of support required, and added specific clinical specifiers for associated features such as intellectual impairment, language impairment, known medical or genetic conditions, and catatonia [13].

Quantitative Comparison of Diagnostic Criteria

Table: Detailed Comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Autism

| Feature | DSM-IV (PDD) | DSM-5 (ASD) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Categories | Five distinct categories: Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Disorder, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, Rett's Disorder, PDD-NOS [12] | Single category: Autism Spectrum Disorder [13] [15] |

| Symptom Domains | Three domains: 1) Social interaction, 2) Communication, 3) Restricted, repetitive behaviors [11] [13] | Two domains: 1) Social communication/social interaction, 2) Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior [16] [13] |

| Required Symptoms | Total of 6+ symptoms across domains, with at least 2 from social, 1 from communication, 1 from behaviors [11] | Total of 5 out of 7 criteria: 3/3 in social-communication, 2/4 in restricted/repetitive behaviors [13] |

| Sensory Issues | Not included as a core diagnostic criterion [13] | Explicitly included as a type of restricted/repetitive behavior [13] [15] |

| Onset Criteria | Onset prior to 3 years of age with delays in social, language, or symbolic play [11] | Symptoms must be present in early developmental period (broadened) [13] |

| Severity Assessment | Not specified | Level 1, 2, 3 requiring support, substantial support, or very substantial support [13] |

| Specifiers | Not available | With/without intellectual impairment, with/without language impairment, associated medical/genetic factors [13] |

Impact on Diagnosis, Services, and Research

Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity

Early studies examining the transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5 criteria raised concerns about potential diagnostic exclusion of some individuals who would have qualified under the previous system. Initial research suggested that the DSM-5 criteria might be less sensitive, particularly for individuals previously diagnosed with PDD-NOS or Asperger's Disorder [11] [16]. One study indicated that 71% of those with PDD-NOS and 91% of those with Asperger's under DSM-IV would qualify for an ASD diagnosis under DSM-5, while the remainder might receive a new diagnosis of Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD) or no longer meet criteria for either [16]. However, subsequent analyses and field trials suggested that the final DSM-5 criteria successfully captured the majority of individuals with meaningful impairments, and that the addition of clinical specifiers and severity levels allowed for more nuanced characterization [10] [11].

The introduction of Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD) as a new diagnostic category in DSM-5 created a distinct boundary for individuals with persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication but without the restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities required for an ASD diagnosis [17] [13]. This differentiation aimed to improve diagnostic specificity by creating a more homogeneous ASD population for research and clinical services.

Real-World Implications and Stigma Considerations

The diagnostic changes had tangible implications for service eligibility and clinical practice. Concerns were raised that individuals losing an ASD diagnosis might face challenges accessing previously available services, particularly since SCD lacks established treatment guidelines and may not qualify for the same educational or therapeutic supports [16]. However, the DSM-5 committee explicitly stated that "all individuals with a current diagnosis should not lose diagnosis or services or school placement" [13], and many service systems adapted to the new criteria without discontinuing supports for previously eligible individuals.

Research on public perception found that the diagnostic label change had minimal impact on stigma. A 2015 study examining the impact of changing from "Asperger's" to "Autistic Spectrum Disorder" found that label did not impact stigma perceptions among the general public, and actually found greater help-seeking and perceived treatment effectiveness for both the Asperger's and ASD labels compared to no label [18]. This suggests that concerns about increased stigma with the ASD label may have been overstated.

Diagram: Diagnostic Transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5. The diagram illustrates how previous diagnostic categories were consolidated into Autism Spectrum Disorder, with the addition of new clinical specifiers. Note that some individuals previously diagnosed with PDD-NOS may now receive a diagnosis of Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder.

Implications for Autism Subtype Research

Methodological Considerations for Neuroimaging Studies

The diagnostic consolidation in DSM-5 presents both challenges and opportunities for research comparing autism subtypes using neuroimaging techniques such as ALFF, fALFF, and GMV. The primary challenge involves historical cohort comparison, as studies initiated under DSM-IV criteria must establish clear cross-walk protocols to ensure comparability with cohorts recruited under DSM-5 [11]. Researchers must carefully document which diagnostic criteria were applied and consider potential heterogeneity introduced by including subjects who would have received different subtype diagnoses under the previous system.

A significant opportunity lies in the reduction of diagnostic arbitrariness. The previous system's lack of reliability in distinguishing between subtypes, particularly between high-functioning autism and Asperger's Disorder, meant that neuroimaging findings based on these categories may have reflected diagnostic inconsistency rather than true neurobiological differences [11]. The DSM-5 framework encourages researchers to identify biologically meaningful subgroups based on dimensional measures (e.g., cognitive profiles, language abilities, sensory features) rather than relying on clinically defined categories that lacked validation [11] [14]. This approach aligns better with the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative by focusing on continuous dimensions of functioning across multiple units of analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Protocols

Table: Key Methodological Components for Neuroimaging Research on Autism Subtypes

| Research Component | Function/Application | Considerations for DSM-5 Era |

|---|---|---|

| Gold-Standard Diagnostic Instruments (ADOS-2, ADI-R) [11] | Standardized assessment of autism symptoms and severity | Essential for establishing diagnostic homogeneity across cohorts; requires calibration for DSM-5 criteria |

| Dimensional Measures of Core Features (SRS, RBS-R) | Quantification of social communication abilities and restricted/repetitive behaviors | Enables stratification based on symptom profiles rather than historical categories |

| Cognitive and Language Assessments (IQ tests, language batteries) | Characterization of associated cognitive and language features | Critical for applying DSM-5 specifiers ("with/without intellectual/language impairment") |

| Sensory Processing Measures (SP, SEN) | Assessment of sensory sensitivities and unusual sensory interests | Directly maps onto DSM-5 expanded criteria for restricted/repetitive behaviors |

| Neuroimaging Protocols (ALFF, fALFF, GMV, functional connectivity) | Identification of neural correlates and potential biomarkers | Should be analyzed in relation to dimensional symptom measures and DSM-5 specifiers |

When designing studies to investigate ALFF, fALFF, and GMV differences in autism, researchers should implement comprehensive phenotypic characterization protocols that extend beyond simple diagnostic categorization. This includes detailed assessment of social communication abilities, language profiles, cognitive functioning, sensory processing patterns, and presence of associated medical conditions [13]. These dimensional measures can then be used as covariates or stratification variables in neuroimaging analyses to identify biologically meaningful subgroups within the autism spectrum.

The implementation of standardized experimental workflows is particularly crucial for multi-site studies and drug development trials. Recommended protocols include: 1) Diagnostic confirmation using ADOS-2 and ADI-R calibrated to DSM-5 criteria; 2) Comprehensive phenotyping across cognitive, language, sensory, and adaptive domains; 3) Uniform MRI acquisition parameters across scanning sites; 4) Harmonized preprocessing pipelines for ALFF/fALFF/GMV analysis; and 5) Stratified analytical approaches that examine both categorical (ASD vs. control) and dimensional (symptom severity correlations) relationships [11]. This methodological rigor will enhance the reproducibility and interpretability of neuroimaging findings in the DSM-5 era.

The evolution from DSM-IV to DSM-5 represents a paradigm shift in how autism is conceptualized and diagnosed, moving from discrete categorical subtypes to a unified spectrum disorder with dimensional specifiers. This transition was grounded in empirical evidence demonstrating the limited validity and reliability of the previous subcategories, and aimed to create a more accurate and clinically useful diagnostic system [10] [11]. For the research community, this shift necessitates updated approaches to subject characterization, study design, and data analysis. Rather than relying on historical categories like Asperger's and PDD-NOS, contemporary research should embrace the dimensional framework of DSM-5, using detailed phenotypic measures to identify biologically meaningful subgroups within the autism spectrum [14]. This approach is particularly relevant for neuroimaging studies investigating ALFF, fALFF, and GMV differences, as it encourages the discovery of neural correlates that align with continuous symptom dimensions rather than artificial diagnostic boundaries. As the field continues to evolve, the DSM-5 framework provides a more valid foundation for advancing our understanding of autism's neurobiological underpinnings and developing targeted interventions.

Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF) and its fractional derivative (fALFF) are validated, non-invasive metrics derived from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) that quantify the intensity of spontaneous, low-frequency (typically 0.01-0.1 Hz) neural activity within brain regions [19] [20]. fALFF, calculated as the ratio of power within the low-frequency band to the total power across the entire frequency spectrum, is considered less sensitive to physiological noise than ALFF [21] [22]. In the study of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)—a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition—these measures provide critical insights into local functional alterations that may underlie core social, communicative, and behavioral symptoms [23] [20]. This guide objectively compares the application and performance of ALFF/fALFF as functional biomarkers, with a specific focus on differentiating ASD subtypes, and situates this within the broader context of multimodal research incorporating Gray Matter Volume (GMV).

Comparative Performance: ALFF/fALFF vs. Other Modalities in ASD Classification

A primary application of neuroimaging biomarkers is the automated classification of individuals with ASD from typically developing controls (TDs). Studies utilizing machine learning and deep learning frameworks provide direct comparisons of classification accuracy across different imaging modalities and features.

Classification Accuracy Across Modalities

The table below summarizes key findings from comparative classification studies, highlighting where ALFF/fALFF-based models stand relative to other approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities in ASD vs. TD Classification

| Study Reference | Modality / Feature Set | Model Used | Sample Size (ASD/TD) | Reported Accuracy | Key Comparative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uddin et al., 2014 [24] | rs-fMRI Functional Connectivity | Various ML Classifiers | 59/59 (NIMH), 89/89 (ABIDE) | Peak 76.67% (NIMH) | Behavioral measures (SRS) far outperformed fMRI, achieving 95.19% accuracy. |

| Sci. Rep., 2024 [25] | ALFF maps (from rs-fMRI) | 3D-DenseNet (One-channel) | 351/351 (ABIDE I) | 72.0% ± 3.1% | Single-channel ALFF model showed strong standalone performance. |

| Sci. Rep., 2024 [25] | ALFF + sMRI maps | 3D-DenseNet (Two-channel) | 351/351 (ABIDE I) | 76.9% ± 2.34% | This multimodal fusion achieved the highest accuracy, outperforming single-modality models (ALFF-only, fALFF-only, sMRI-only). |

| Sci. Rep., 2024 [25] | fALFF + sMRI maps | 3D-DenseNet (Two-channel) | 351/351 (ABIDE I) | 73.2% (Approx. from text) | Lower than ALFF-sMRI fusion, suggesting ALFF may carry more discriminative power in this context. |

| Frontiers, 2024 [19] [7] | Multimodal (FC, ALFF, fALFF, GMV) | Tensor Decomposition & Statistical Testing | 152 Autism, 54 Asperger’s, 28 PDD-NOS | N/A (Subtype Comparison) | Demonstrated significant functional/structural differences between subtypes, supporting their biological validity. |

Key Comparative Insights

- Multimodal Superiority: The most consistent finding is that combining functional features (like ALFF) with structural data (sMRI/GMV) yields superior classification performance compared to any single modality [25]. This suggests ALFF/fALFF and structural measures provide complementary information for characterizing ASD.

- ALFF vs. fALFF: In a direct comparison within the same deep learning architecture, the model using ALFF maps outperformed the one using fALFF maps when both were fused with sMRI [25]. This indicates that for whole-brain classification tasks, the raw amplitude measure (ALFF) might be more informative than the fractional measure (fALFF) in this specific context.

- Benchmarking Against Behavior: It is crucial to contextualize neuroimaging biomarker performance. While ALFF-based models can achieve accuracies above 70-75%, well-validated behavioral instruments like the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) can achieve near-perfect separation in high-functioning cohorts [24]. This sets a high bar for the clinical utility of standalone imaging biomarkers.

Discriminating ASD Subtypes: Evidence from ALFF/fALFF and Multimodal Studies

A more nuanced application of biomarkers is in parsing the heterogeneity within ASD, particularly by distinguishing historical DSM-IV subtypes: Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS).

Table 2: ALFF/fALFF and Multimodal Differences Across ASD Subtypes

| Subtype | Key Regional Alterations in ALFF/fALFF | Associated Brain Networks/Regions | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autistic Disorder | • Negative fALFF in thalamus, amygdala, caudate [5].• Significant impairments linked to subcortical network and default mode network (DMN) [19] [7]. | Subcortical Network, DMN (precuneus, mPFC), Occipital Cortex. | [19] [7] [5] |

| Asperger’s Syndrome | • Negative fALFF between putamen and parahippocampus [5]. | Subcortical-Cortical Circuits. | [5] |

| PDD-NOS | • Negative fALFF in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) [5]. | Salience Network/ACC. | [5] |

| Common to All Subtypes | • Shared functional-structural covariation in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and superior/middle temporal cortex [5].• Social interaction deficits correlated with brain patterns across subtypes [5]. | Frontotemporal Networks. | [5] |

- Biological Validity of Subtypes: The distinct spatial patterns of fALFF abnormalities across subtypes provide neurobiological evidence supporting the historical clinical distinctions between Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s, and PDD-NOS [19] [5].

- Core vs. Unique Deficits: Findings suggest a common neural basis centered on frontotemporal regions (like DLPFC) linked to core social-cognitive deficits, co-existing with subtype-unique dysfunction in specific subcortical-limbic circuits [5]. For instance, Autistic Disorder shows prominent thalamic-amygdala-caudate anomalies, while Asperger’s and PDD-NOS involve different striatal and cingulate regions.

- Convergence with DMN Research: The particular distinction of the Autistic subtype based on DMN and subcortical network dysfunction [19] [7] aligns with broader meta-analytic findings implicating the DMN (including mPFC/ACC and precuneus) and insula as hubs of alteration in ASD [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

Protocol 1: Multimodal Subtype Comparison (Frontiers, 2024 [19] [7])

- Data Source: ABIDE I preprocessed dataset.

- Cohort: 152 Autism, 54 Asperger’s, 28 PDD-NOS patients (DSM-IV diagnosed).

- Preprocessing: Connectome Computation System (CCS) pipeline. For fMRI: band-pass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz), global signal regression, registration to MNI152 template.

- Feature Extraction:

- Functional: (a) Brain community patterns via tensor decomposition of functional connectivity matrices. (b) Voxel-wise ALFF and fALFF.

- Structural: Voxel-based Gray Matter Volume (GMV) from structural MRI.

- Analysis: Statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA) to identify significant differences in extracted features among the three subtypes.

Protocol 2: Multimodal Fusion for Subtype Identification (Mol. Autism, 2020 [5])

- Data Source: Discovery cohort from ABIDE II (n=229 ASD, n=126 TDC); Replication cohort from ABIDE I.

- Cohort: Asperger’s (n=79), PDD-NOS (n=58), Autistic (n=92) from ABIDE II.

- Imaging Features: fALFF (functional) and GMV (structural).

- Fusion & Analysis: Used Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) scores as a reference to guide a multiset canonical correlation analysis (mCCA) for fALFF-GMV fusion. Identified multimodal correlation patterns specific to each subtype and correlated them with ADOS subdomains.

Protocol 3: Deep Learning Classification (Sci. Rep., 2024 [25])

- Data Source: ABIDE I, quality-controlled (351 ASD / 351 TD, ages 2-30).

- Preprocessing:

- sMRI: Downsampling to 3mm isotropic, skull-stripping.

- rs-fMRI: Motion correction, despiking, detrending, band-pass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz), ALFF/fALFF calculation.

- Model: 3D-DenseNet architecture.

- Inputs: Trained separate models on: 1) sMRI only, 2) ALFF only, 3) fALFF only, 4) two-channel ALFF+sMRI, 5) two-channel fALFF+sMRI.

- Validation: Ten-fold cross-validation.

Visualization of Research Workflows

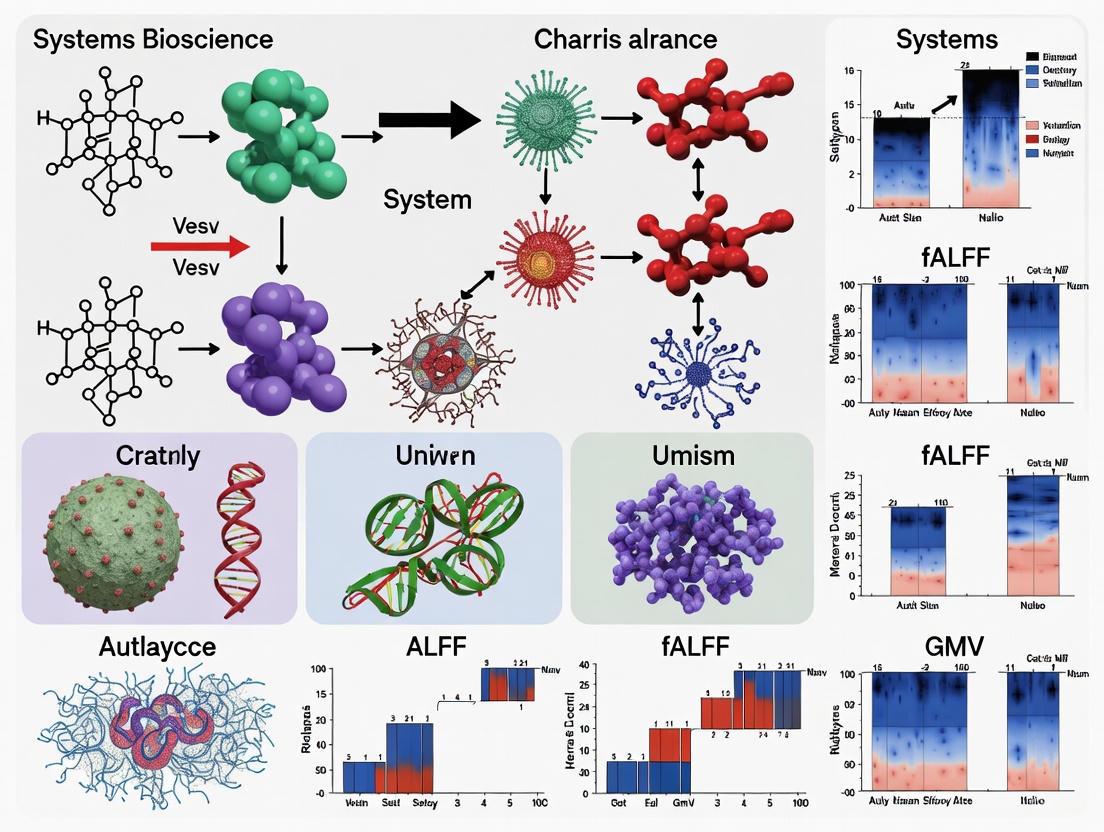

Figure 1: Multimodal Research Workflow for ASD Biomarker Discovery. This diagram outlines the standard pipeline from public data acquisition to the primary analytical applications of ALFF/fALFF and GMV data in autism research.

Figure 2: Essential Research Toolkit for ALFF/fALFF-GMV Studies. This diagram categorizes key resources and methodologies required to execute the research described in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Multimodal ASD Biomarker Research

| Category | Item | Primary Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repository | Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I & II) | Publicly shared, aggregated dataset of rs-fMRI, sMRI, and phenotypic data from individuals with ASD and typical controls across multiple international sites. The foundational resource for most large-scale analyses [19] [24] [7]. |

| Data Repository | SPINS & SPIN-ASD Datasets | Harmonized, transdiagnostic datasets including individuals with ASD, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and controls, designed for studying social processes [21] [26]. |

| Processing Pipeline | Connectome Computation System (CCS) | A standardized preprocessing pipeline for resting-state fMRI data, ensuring reproducibility and reducing site-related variability in studies using ABIDE data [19] [7]. |

| Analysis Toolbox | DPABI / DPARSF | A MATLAB toolbox for rs-fMRI data analysis. Includes utilities for calculating ALFF/fALFF/ReHo, and crucially, the ComBat harmonization tool to remove scanner-site effects in multi-site data [22]. |

| Analysis Software | Seed-based d Mapping (SDM) | Software specifically designed for performing voxel-based meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies, used to identify the most robust regions of functional or structural alteration across the literature [20]. |

| Fusion Algorithm | Multiset Canonical Correlation Analysis (mCCA) | A multivariate technique used to identify correlated patterns across multiple datasets (e.g., fALFF and GMV), guided by a reference variable like clinical scores [5]. |

| Classification Model | 3D-DenseNet | A deep convolutional neural network architecture well-suited for classifying 3D neuroimaging maps (e.g., ALFF, sMRI). Its dense connectivity pattern facilitates feature reuse and has shown high performance in ASD classification [25]. |

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by heterogeneous deficits in social communication and the presence of restricted, repetitive behaviors [9]. The neurobiological underpinnings of ASD are multifaceted, involving alterations in both brain structure and function. Within this framework, Gray Matter Volume (GMV) has emerged as a crucial structural indicator for investigating brain morphology in ASD [7] [5]. The diagnostic criteria and conceptualization of ASD have evolved, historically encompassing subtypes such as Autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) based on the DSM-IV [7]. This review objectively examines the role of GMV alterations within a broader multimodal research context, comparing it with functional indicators like the Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF) and fractional ALFF (fALFF), and highlighting its specific value in differentiating ASD subtypes for researchers and drug development professionals [7] [5].

Comparative Alterations of GMV, fALFF, and ALFF in ASD Subtypes

Research utilizing multimodal neuroimaging has revealed distinct and shared neural patterns across traditional ASD subtypes. These findings are critical for parsing the heterogeneity of ASD and moving toward precision medicine.

Common Neural Deficits Across Subtypes

Studies consistently identify a common neural basis for core ASD symptoms, particularly social interaction deficits. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and superior/middle temporal cortex are the primary common functional–structural covarying cortical brain areas shared among Asperger’s, PDD-NOS and Autistic subgroups [5]. The salience network and limbic system have also been consistently associated with multiple social impairments in ASD across both GMV and functional modalities [8]. Furthermore, a 2024 meta-analysis established that individuals with ASD exhibit decreased GMV in the anterior cingulate cortex/medial prefrontal cortex (ACC/mPFC) and left cerebellum [9]. These common alterations likely represent the foundational neuroanatomical architecture underlying the core social and communicative deficits that define ASD.

Unique Alterations Defining ASD Subtypes

A seminal study guided by Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) scores revealed key functional differences among subtypes localized within subcortical brain areas [5]. The investigation identified negative functional features, including negative putamen–parahippocampus fALFF unique to the Asperger’s subtype, negative fALFF in the anterior cingulate cortex unique to PDD-NOS, and negative thalamus–amygdala–caudate fALFF unique to the Autistic subtype [5]. This suggests that while a common neural core exists, each subtype is characterized by a unique pattern of functional disruption in specific subcortical circuits.

Table 1: Summary of Subtype-Specific Neural Alterations in ASD

| ASD Subtype | Specific fALFF Alterations | Associated Social Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Asperger's | Negative putamen-parahippocampus fALFF [5] | Social Interaction [5] |

| PDD-NOS | Negative fALFF in anterior cingulate cortex [5] | Social Interaction [5] |

| Autistic | Negative thalamus–amygdala–caudate fALFF [5] | Social Interaction [5] |

Multimodal Convergence and Divergence

The integration of GMV with functional measures like fALFF provides a more comprehensive picture of the ASD brain. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that ASD involves similar alterations in both function and structure, particularly in the insula and ACC/mPFC [9]. Notably, this review also identified a key divergence: the left insula showed decreased resting-state functional activity but increased GMV [9]. This discordance between structure and function highlights the complexity of ASD's neuropathology and underscores the necessity of a multimodal approach to avoid oversimplified conclusions. Another study affirmed that brain regions related to social impairment are potentially interconnected across modalities, suggesting a tightly coupled relationship between anatomical and functional deficits [8].

Table 2: Multimodal Meta-Analysis Findings in ASD (2024)

| Brain Region | Functional Alteration (vs. TDs) | GMV Alteration (vs. TDs) | Modality Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left Insula | Decreased activity [9] | Increased GMV [9] | Discordant |

| ACC/mPFC | Decreased activity [9] | Decreased GMV [9] | Concordant |

| Cerebellum | Not Specified | Decreased GMV [9] | - |

| Default Mode Network | Aberrant activity [9] | Aberrant volume [9] | Concordant |

Experimental Protocols for GMV, ALFF, and fALFF Analysis

Robust and reproducible findings in neuroimaging rely on standardized experimental protocols. The following methodologies are commonly employed in the field for extracting GMV, ALFF, and fALFF metrics.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The foundational data for this research often comes from large, publicly available datasets such as the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I/II), which aggregates resting-state functional MRI (fMRI), structural MRI (sMRI), and phenotypic data from multiple international sites [7] [5] [8]. A typical preprocessing pipeline for this data, as implemented by the Connectome Computation System (CCS), includes several key steps [7]:

- Slice Timing Correction: Accounts for acquisition time differences between slices.

- Realignment: Corrects for head motion.

- Spatial Normalization: Registration of individual brains to a standard template (e.g., MNI152).

- Spatial Smoothing: Application of a Gaussian kernel to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Band-Pass Filtering: For functional data, typically between 0.01-0.1 Hz to focus on low-frequency fluctuations [7] [27].

Additional preprocessing for structural images involves segmenting the brain into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid to isolate GMV [9].

Computational Methods for Feature Extraction

GMV Analysis: GMV is typically analyzed using Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM), an automated whole-brain technique for characterizing regional differences in tissue volume [28] [9]. The process involves segmenting the T1-weighted structural images, normalizing the gray matter segments to a standard space, and modulating the images to preserve the total amount of gray matter from the original image. The resulting modulated GMV maps are then smoothed and subjected to statistical analysis [9].

ALFF/fALFF Analysis:

- ALFF is computed by transforming the preprocessed fMRI time series for each voxel into the frequency domain using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The square root of the power spectrum is calculated, and ALFF is defined as the average of this amplitude across the low-frequency range (0.01-0.1 Hz) [29] [27]. It represents the absolute strength or intensity of low-frequency oscillations.

- fALFF is calculated as the ratio of the power in the low-frequency range (0.01-0.1 Hz) to the power across the entire detectable frequency range. This normalization makes fALFF more specific to gray matter signal by reducing sensitivity to physiological noise from areas like ventricles and blood vessels [29] [27].

For both ALFF and fALFF, subject-level maps are often converted to Z-scores to create standardized maps for group-level analysis [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources and computational tools essential for conducting research on GMV and low-frequency oscillations in ASD.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ASD Neuroimaging Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to GMV/fALFF/ALFF |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE Database [7] [5] [8] | Data Repository | Provides large-scale, shared datasets of fMRI, sMRI, and phenotypic data from ASD individuals and typical controls. | Serves as the foundational source of raw imaging and clinical data for large-scale analyses. |

| Connectome Computation System (CCS) [7] | Software Pipeline | Standardized preprocessing pipeline for neuroimaging data. | Ensures consistent data quality and comparability across studies by handling initial processing steps. |

| Data Processing & Analysis for Brain Imaging (DPABI) [28] | Software Toolkit | A comprehensive toolbox for analyzing brain imaging data. | Used for computing VBM, ALFF, fALFF, and performing statistical analyses. |

| Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) [28] | Software Package | A widely used software for voxel-based statistical analysis of brain imaging data. | Employed for image segmentation, normalization, and statistical modeling of GMV and functional maps. |

| Seed-based d Mapping (SDM) [9] | Software Package | A specialized software for voxel-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. | Enables researchers to synthesize findings across multiple studies to identify the most robust effects. |

GMV stands as a robust and reliable structural indicator for elucidating the neuroanatomy of ASD, particularly when integrated with functional metrics like fALFF and ALFF in a multimodal framework. Evidence consistently points to common GMV alterations in social brain regions such as the ACC/mPFC across the autism spectrum, which may underlie core social deficits [5] [9]. Simultaneously, unique patterns of functional alteration in subcortical structures help to define the historical ASD subtypes, offering a potential neurobiological explanation for their clinical heterogeneity [5]. The observed discordance in regions like the insula, where GMV and functional activity can change in opposite directions, underscores the complex, non-linear relationship between brain structure and function in ASD [9]. For future research and therapeutic development, this body of work argues strongly for a stratified, biomarker-informed approach. Parsing ASD based on distinct multimodal neuroimaging signatures, rather than treating it as a single entity, will be crucial for developing targeted interventions and advancing precision medicine in autism.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a complex array of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by significant heterogeneity in clinical presentation, underlying biology, and developmental trajectories. This diversity presents a substantial challenge for pinpointing consistent neural correlates that span across traditional diagnostic boundaries. Within this context, neuroimaging research has increasingly focused on identifying common neural substrates that persist across ASD subtypes, while also delineating subtype-specific variations that may inform more targeted interventions. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and superior/middle temporal cortex have emerged as key regions of interest, forming a potential common neural basis for ASD despite its heterogeneous presentation. Advanced analytical approaches incorporating multimodal fusion of functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data have begun to reveal both shared and distinct neural patterns across historically recognized ASD subtypes, including Autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) [30] [5].

The integration of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF), fractional ALFF (fALFF), and gray matter volume (GMV) measures provides a comprehensive framework for examining both functional and structural neural correlates of ASD. ALFF and fALFF metrics capture regional spontaneous brain activity by measuring the amplitude of low-frequency oscillations in blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals, offering insights into local neural functionality, while GMV analyses reveal structural differences in brain morphology [7] [19]. Together, these measures enable researchers to map both the functional and architectural aspects of neural systems implicated across ASD subtypes, facilitating a more nuanced understanding of the disorder's neurobiological underpinnings.

Comparative Neuroimaging Data Across ASD Subtypes

Table 1: Common and Unique Neural Patterns Across ASD Subtypes Based on Multimodal Neuroimaging

| ASD Subtype | Common Neural substrates (DLPFC & Temporal Cortex) | Unique Functional Features (fALFF) | Associated Clinical Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asperger's | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and superior/middle temporal cortex (shared across subtypes) [30] | Negative putamen-parahippocampus fALFF [30] [5] | Correlated with distinct ADOS subdomains, with social interaction as common deficit [30] |

| PDD-NOS | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and superior/middle temporal cortex (shared across subtypes) [30] | Negative fALFF in anterior cingulate cortex [30] [5] | Correlated with distinct ADOS subdomains, with social interaction as common deficit [30] |

| Autistic | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and superior/middle temporal cortex (shared across subtypes) [30] | Negative thalamus-amygdala-caudate fALFF [30] [5] | Correlated with distinct ADOS subdomains, with social interaction as common deficit [30] |

Table 2: Methodological Approaches in Key ASD Subtype Studies

| Study Reference | Primary Imaging Modalities | Analytical Approach | Sample Characteristics | Key Findings Related to Common Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qi et al. (2020) [30] [5] | resting-state fMRI, sMRI | Multimodal fusion (MCCAR + jICA); ADOS-guided fusion of fALFF and GMV | ABIDE II: 79 Asperger's, 58 PDD-NOS, 92 Autistic; ABIDE I: 400 replication [30] | Identified DLPFC and superior/middle temporal cortex as primary common functional-structural covarying areas across subtypes |

| Frontiers Study (2024) [7] [19] | resting-state fMRI, structural MRI | Tensor decomposition, ALFF/fALFF, GMV, functional connectivity | ABIDE I: 152 Autistic, 54 Asperger's, 28 PDD-NOS [7] | Impairments in subcortical network and default mode network differentiated Autistic subtype from others |

| Abnormal Social Impairments Study (2024) [8] | resting-state fMRI, structural MRI | Supervised multimodal fusion (MCCAR + jICA) using SRS scores | ABIDE I/II: 343 ASD males, 356 healthy controls [8] | Salience network and limbic system associated with social impairments across ASD |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multimodal Fusion Analysis Protocol

The identification of common neural substrates across ASD subtypes has relied heavily on advanced multimodal fusion techniques. One prominent methodology comes from Qi et al. (2020), which implemented a comprehensive protocol for fusing functional and structural neuroimaging data [30] [5]. The experimental workflow began with data acquisition from the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) I and II datasets, utilizing both resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) and structural MRI (sMRI) scans. Participants included individuals with DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of Asperger's disorder (n=79), PDD-NOS (n=58), and Autistic disorder (n=92) from ABIDE II as a discovery cohort, with ABIDE I (n=400) serving as a replication cohort. All participants were male and under 35 years of age, with ASD diagnoses confirmed using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) at each collection site [5].

Image preprocessing followed standardized pipelines including motion correction, spatial normalization to MNI152 standard space, and segmentation of structural images. For functional data, processing included band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) and nuisance signal regression. The core analysis employed a two-way fusion model (MCCAR + jICA) that integrated fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) from fMRI with gray matter volume (GMV) from sMRI, using ADOS scores as a reference to guide the fusion process [30] [5]. This supervised fusion approach allowed researchers to identify covarying components that represented both common and unique multimodal patterns across the three ASD subtypes, with statistical validation through bootstrapping and cross-validation techniques.

Tensor Decomposition and Feature Extraction Protocol

A separate methodological approach was implemented in the 2024 Frontiers study, which focused on comparing ASD subtypes through tensor decomposition and multiple feature extraction methods [7] [19]. This protocol utilized exclusively the ABIDE I dataset, with carefully selected participants including 152 with autism, 54 with Asperger's, and 28 with PDD-NOS. The preprocessing leveraged the Connectome Computation System (CCS) pipeline, incorporating filt_global preprocessing with band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) and global signal regression [7].

The analytical framework extracted four primary classes of features: (1) brain patterns via tensor decomposition of functional connectivity matrices; (2) amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF); (3) fractional ALFF (fALFF); and (4) gray matter volume (GMV). Tensor decomposition specifically addressed the high-dimensional nature of resting-state fMRI data (brain regions × time × patients) by extracting compressed feature sets that represented different brain communities. Statistical testing between subtypes was then performed on these feature sets, with particular focus on identifying significantly dissimilar patterns between subtypes [7] [19]. This multi-feature approach allowed for a systematic comparison of functional and structural differences between the three common ASD subtypes, with emphasis on differentiating patterns in subcortical and default mode networks.

Diagram 1: Multimodal Neuroimaging Analysis Workflow for ASD Subtype Comparison. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive analytical pipeline used to identify common and distinct neural patterns across autism spectrum disorder subtypes, integrating multiple feature extraction methods and validation approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for ASD Neuroimaging Studies

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in ASD Research | Example Implementation in Reviewed Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE I & II Datasets | Data Resource | Publicly shared neuroimaging data providing resting-state fMRI, structural MRI, and phenotypic data from multiple international sites [7] [5] | Served as primary data source for all major studies; ABIDE II for discovery (n=229 ASD) and ABIDE I for replication (n=400 ASD) [30] |

| Automated Diagnostic Instruments (ADOS, ADI-R, SRS) | Clinical Assessment | Standardized behavioral measures for ASD diagnosis and symptom severity quantification [5] [8] | ADOS used as reference to guide multimodal fusion; SRS scores used to correlate brain patterns with social impairment severity [30] [8] |

| Connectome Computation System (CCS) | Computational Pipeline | Standardized preprocessing and analysis of functional and structural neuroimaging data [7] | Used for filt_global preprocessing with band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) and global signal regression [7] |

| MCCAR + jICA Model | Analytical Algorithm | Multimodal fusion method for identifying covarying patterns across imaging modalities [30] [8] | Implemented for fALFF-GMV fusion using clinical scores as reference [30] |

| Tensor Decomposition Methods | Analytical Algorithm | Feature extraction technique for high-dimensional fMRI data (brain regions × time × patients) [7] | Applied to identify different brain communities and patterns across ASD subtypes [7] |

Integration with Contemporary Subtyping Frameworks

While the neuroimaging findings discussed primarily address historical DSM-IV subtypes, recent research has revealed more nuanced biological subdivisions within autism. A groundbreaking 2025 study analyzing over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort identified four biologically and clinically distinct ASD subtypes using a person-centered computational approach [3] [31]. These subtypes—Social and Behavioral Challenges, Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay, Moderate Challenges, and Broadly Affected—each demonstrated distinct genetic profiles and developmental trajectories [3]. This refined subtyping framework aligns with the neuroimaging findings, particularly in revealing differential biological processes and developmental timing across subgroups.

Notably, the identification of these data-driven subtypes reinforces the concept of both shared and unique neural substrates across the autism spectrum. Children in the Broadly Affected subtype showed the highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations and more widespread clinical challenges, while the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype exhibited genetic mutations affecting genes that become active predominantly after birth, aligning with their later diagnosis and absence of developmental delays [3] [31]. These genetic findings complement the neuroimaging results, suggesting that differential genetic underpinnings may drive the varied patterns of neural structure and function observed across ASD subtypes.

Diagram 2: Evolution of ASD Subtype Frameworks and Their Neural Correlates. This diagram illustrates the relationship between historical and contemporary approaches to autism subtyping and their connection to both common and distinct neural patterns identified through neuroimaging research.

The convergence of evidence from multimodal neuroimaging studies strongly supports the existence of common neural substrates, particularly in dorsolateral prefrontal and temporal cortical regions, across historically defined ASD subtypes. These shared neural patterns, identified through integrated analyses of fALFF, ALFF, and GMV metrics, likely underlie core social interaction deficits that transcend diagnostic subdivisions. Simultaneously, the distinct subtype-specific patterns in subcortical structures and specific cortical regions highlight the biological validity of subgroup distinctions and point toward potentially different underlying mechanisms.

These findings have significant implications for both research and clinical practice. The identification of robust neuroimaging signatures across subtypes provides valuable biomarkers for diagnostic refinement and offers targets for future therapeutic development. Furthermore, the alignment between neuroimaging patterns and newly identified data-driven subtypes suggests a path toward truly precision medicine in autism, where individuals can receive interventions tailored to their specific neurobiological profile. As research continues to integrate genetic, neuroimaging, and deep phenotypic data, our understanding of both common and unique neural substrates in autism will continue to refine, ultimately leading to more effective, personalized approaches to support individuals across the autism spectrum.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is not a single unified neurodevelopmental condition but rather encompasses a spectrum of subtypes with distinct clinical presentations and neurobiological underpinnings [7] [19]. Historically, ASD has been categorized into several subtypes including autism, Asperger's syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) based on diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [7]. While the diagnostic landscape has evolved with DSM-5, which eliminated these distinct subtypes, research continues to demonstrate significant neurobiological heterogeneity across these clinical categories that warrants detailed investigation [7] [19].

The identification of subtype-specific neural signatures has emerged as a critical endeavor in autism research, with particular interest in patterns of local functional activity and structural brain organization [7] [9]. Key metrics including the Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF), fractional ALFF (fALFF), and Gray Matter Volume (GMV) have enabled researchers to quantify differences in intrinsic brain function and structure across ASD subtypes [7] [19] [9]. Converging evidence suggests that alterations in two specific neural systems—the subcortical network and the default mode network (DMN)—may represent crucial divergence points between ASD subtypes [7] [32] [33]. This review systematically compares functional and structural patterns across ASD subtypes, with emphasis on subcortical and DMN alterations, to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals working to advance personalized interventions in autism.

Neurobiological Foundations of ASD Subtypes

Historical Context and Diagnostic Evolution

The conceptualization of autism subtypes has undergone significant evolution. Under DSM-IV criteria, ASD encompassed several distinct diagnoses including autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder, and PDD-NOS [7]. Each subtype presented with unique clinical features; Asperger's syndrome, for instance, was characterized by preserved linguistic and cognitive abilities despite social communication challenges [7]. The subsequent DSM-5 consolidation into a single autism spectrum disorder category reflected growing recognition of the fluid boundaries between subtypes, though neurobiological research continues to validate meaningful distinctions at the neural systems level [7] [19].

The heterogeneity in ASD presentation poses substantial challenges for treatment development and clinical management. Individuals with ASD display remarkable variability in social communication deficits, restricted/repetitive behaviors, sensory processing patterns, and cognitive functioning [34] [35]. This diversity likely stems from distinct underlying neurobiological mechanisms that may be obscured when ASD is studied as a unitary condition [7] [19] [35]. Neuroimaging-based subtyping approaches have consequently gained traction as a means to identify biologically meaningful subgroups that could inform targeted interventions [34] [35].

Key Neural Networks Implicated in ASD

Research has consistently highlighted several large-scale brain networks that show alterations in ASD, with two networks particularly relevant for subtype differentiation:

Subcortical Networks: Encompassing structures such as the thalamus and basal ganglia, these regions play crucial roles in sensory processing, behavioral flexibility, and the regulation of cortical activity [32] [36]. Multiple studies have reported atypical subcortico-cortical connectivity in ASD, characterized by increased functional coupling between subcortical structures and primary sensory cortices [32] [36] [37]. This hyperconnectivity may contribute to sensory hypersensitivity and difficulties with top-down regulation of behavior [32] [36].

Default Mode Network (DMN): Comprising the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and temporoparietal junction (TPJ), the DMN supports self-referential processing, mentalizing, and social cognition [33]. DMN dysfunction has been consistently linked to social and communication deficits in ASD, with atypical functional connectivity and network organization observed across multiple studies [7] [33]. The DMN's role in processing information about the "self" in relation to "others" positions it as a key network for understanding core social challenges in autism [33].

Other relevant networks include the frontoparietal network (involved in cognitive control), salience network (involved in detecting behaviorally relevant stimuli), and sensory networks (visual, auditory, somatosensory) that frequently show atypical connectivity patterns in ASD [34] [9].

Methodological Approaches for Subtype Differentiation

Neuroimaging Metrics and Analytical Frameworks

The comparison of ASD subtypes relies on advanced neuroimaging techniques and analytical approaches that quantify differences in brain function and structure. The following methodologies have proven particularly valuable for delineating subtype-specific neural patterns:

Table 1: Key Methodological Approaches in ASD Subtype Research

| Method | Description | Application in ASD Subtypes |

|---|---|---|

| ALFF/fALFF | Measures the amplitude of spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations in BOLD signal; reflects intensity of regional neural activity [9] | Identifies localized functional alterations across subtypes; useful for detecting regional hyperactivation or hypoactivation [7] [19] |

| Gray Matter Volume (GMV) | Quantifies volume of gray matter tissue using structural MRI; derived through VBM [7] [9] | Reveals structural differences in specific brain regions across subtypes; can indicate atypical neurodevelopment [7] [19] |

| Functional Connectivity (FC) | Measures temporal correlations between brain regions; identifies functionally connected networks [34] [32] | Maps integration and segregation of brain networks; identifies atypical network organization in subtypes [7] [34] [32] |

| Tensor Decomposition | Multivariate approach for extracting features from high-dimensional fMRI data [7] [19] | Captures complex brain community patterns and functional organization differences between subtypes [7] [19] |

| Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) | Computational method for estimating directional influences between brain regions [36] | Models effective connectivity and tests hypotheses about directional relationships in neural systems [36] |

| Normative Modeling | Individual-level approach quantifying deviations from typical neurodevelopmental trajectories [35] | Identifies personalized patterns of neural atypicality; enables transdiagnostic subtyping [35] |

Research in this field predominantly utilizes resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), which captures spontaneous brain activity while participants lie at rest in the scanner. This approach provides insights into the brain's intrinsic functional architecture without requiring task performance, which can be challenging for individuals with ASD [7] [32] [33].

The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) has been instrumental in advancing subtype research by aggregating large-scale neuroimaging datasets across multiple international sites [7] [32]. The ABIDE I dataset, for instance, includes data from 539 individuals with ASD and 573 typically developing controls across 17 sites, with substantial numbers of each subtype (152 autism, 54 Asperger's, 28 PDD-NOS in one analysis) [7] [19]. This collaborative initiative has enabled sufficiently powered studies to detect subtype differences despite the challenges of recruitment and data collection in ASD populations.

Standardized preprocessing pipelines are critical for ensuring reproducible results. Common steps include slice timing correction, head motion realignment, normalization to standard stereotactic space (e.g., MNI152), spatial smoothing, and band-pass filtering (typically 0.01-0.1 Hz) to reduce physiological noise [7] [19]. For functional connectivity analyses, additional processing often includes global signal regression and nuisance regressor removal to minimize non-neural contributions to the BOLD signal [7] [32].

The following diagram illustrates a typical analytical workflow for identifying subtype-specific neural patterns:

Comparative Analysis of ASD Subtypes

Subcortical Network Divergence Across Subtypes

Subcortical structures and their connections with cortical regions show distinctive patterns across ASD subtypes, with particular relevance to sensory processing and behavioral regulation:

Table 2: Subcortical Network Characteristics Across ASD Subtypes

| Subtype | Subcortical-Cortical Connectivity | Key Regional Findings | Clinical Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism | Significantly increased connectivity between subcortical regions (thalamus, basal ganglia) and primary sensory networks [7] [32] | Atypical functional integration in subcortical network; impaired segregation from sensory cortices [7] [36] | Associated with sensory hypersensitivity and behavioral inflexibility [32] [36] |

| Asperger's | Moderate subcortical-cortical connectivity; less pronounced than in autism subtype [7] | Intermediate pattern between autism and PDD-NOS; less aberrant subcortical network organization [7] | Fewer sensory processing challenges compared to autism [7] |

| PDD-NOS | Least pronounced subcortical-cortical connectivity alterations among subtypes [7] | More typical subcortical-sensory network segregation [7] | Potentially milder sensory symptoms [7] |

The autism subtype demonstrates the most prominent subcortical-cortical hyperconnectivity, particularly affecting thalamocortical and striatocortical pathways [32] [36]. This neural signature represents a potential biomarker for distinguishing autism from other ASD subtypes. Computational modeling suggests that these macroscale connectivity patterns may reflect atypical increases in recurrent excitation/inhibition within cortical microcircuits, as well as excessive subcortical inputs into sensory regions [37].

Notably, the typical developmental process involves gradual segregation of subcortical and cortical sensory systems, which appears delayed or arrested in ASD, particularly in the autism subtype [36]. This aberrant developmental trajectory may result in an excessive flow of unprocessed sensory information to cortical areas, potentially overwhelming higher-order cognitive processes and contributing to symptoms such as sensory overload and attention difficulties [32] [36].

Default Mode Network Alterations

The DMN shows subtype-specific functional and structural alterations that correspond with social cognitive profiles:

Table 3: Default Mode Network Characteristics Across ASD Subtypes

| Subtype | DMN Functional Connectivity | Structural GMV Alterations | Social Cognitive Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism | Significant functional impairments in DMN; reduced connectivity within core nodes (PCC, mPFC) and with other networks [7] [33] | GMV alterations in key DMN regions including PCC and mPFC [7] [9] | Substantial difficulties with self-referential processing and mentalizing [7] [33] |

| Asperger's | Less pronounced DMN dysfunction compared to autism; intermediate connectivity patterns [7] | Milder GMV alterations in DMN regions compared to autism [7] | Social challenges but potentially stronger self-referential abilities than autism [7] |

| PDD-NOS | Least affected DMN connectivity among the three subtypes [7] | Minimal GMV differences in DMN compared to typical development [7] | Possibly less impaired social cognition relative to other subtypes [7] |

The autism subtype demonstrates the most substantial DMN alterations, characterized by functional hypoactivation and disrupted connectivity during social cognitive tasks [33]. Specifically, the ventral mPFC shows blunted responses during self-referential judgments, while the TPJ and dorsal mPFC exhibit reduced engagement during mentalizing tasks [33]. These functional differences are complemented by structural GMV alterations in key DMN nodes, particularly the ACC/mPFC and insular regions [9].

The DMN's role in integrating information about the self in relation to others positions it as a crucial network for understanding the social core deficits in ASD [33]. The graded severity of DMN alterations across subtypes—with autism most affected, followed by Asperger's and then PDD-NOS—parallels the clinical social communication challenges observed in these groups [7] [33].

ALFF/fALFF and GMV Profiles

Local functional activity and gray matter structure show distinct patterns across subtypes:

Table 4: ALFF/fALFF and GMV Profiles Across ASD Subtypes

| Metric | Autism | Asperger's | PDD-NOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALFF/fALFF | Marked alterations in subcortical regions and DMN nodes; atypical low-frequency oscillations [7] [19] | Intermediate ALFF/fALFF patterns; less aberrant than autism [7] | Closest to typical ALFF/fALFF profiles [7] |

| GMV | Significant GMV differences in subcortical structures and DMN regions; atypical neurodevelopment [7] [9] | Milder GMV alterations; less structural impact than autism [7] | Minimal GMV deviations from typical development [7] |

The autism subtype demonstrates the most prominent ALFF/fALFF and GMV alterations, suggesting widespread atypicalities in both local functional activity and brain structure [7] [19] [9]. These multimodal differences reinforce the distinct neurobiological signature of this subtype and may reflect more pronounced early neurodevelopmental alterations.

Notably, a multimodal meta-analysis of functional and structural studies found consistent alterations in both function and structure of the insula and ACC/mPFC across ASD, with these regions showing decreased resting-state functional activity but increased GMV in individuals with ASD [9]. This pattern suggests potential disturbances in synaptic pruning or neuroinflammation that could impact both functional and structural properties of these socially relevant brain regions.

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit