Decoding Autism: Biochemical Pathways, Genetic Subtypes, and Precision Medicine Approaches

This article synthesizes the latest breakthroughs in understanding the biochemical and genetic architecture of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Decoding Autism: Biochemical Pathways, Genetic Subtypes, and Precision Medicine Approaches

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest breakthroughs in understanding the biochemical and genetic architecture of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). We explore the paradigm shift from a unitary condition to one of distinct biologically defined subtypes, each with unique genetic programs, developmental trajectories, and pathophysiological mechanisms. For a research and drug development audience, the review details advanced computational methodologies for subtype stratification, analyzes challenges in therapeutic development—including drug metabolism considerations and target identification—and evaluates emerging preclinical and clinical validation strategies. The integration of multi-omics data, exposomics, and a precision medicine framework is highlighted as the future of ASD research and treatment.

The New Biology of Autism: From a Single Spectrum to Distinct Biochemical Subtypes

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents one of the most complex challenges in modern neuropsychiatry, characterized by astounding phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity that has long confounded research efforts to establish coherent biological models. The prevailing clinical adage, "If you've met one person with autism, you've met one person with autism," underscores the extraordinary diversity of experiences falling under the ASD diagnosis [1]. While the spectrum concept usefully captures this variability, it simultaneously obscures crucial differences that may hold the key to understanding etiology and developing targeted interventions. As noted by Fred Volkmar, a psychiatrist and professor emeritus at Yale University, "The beauty of the autism spectrum is: it speaks to this heterogeneity. And the downside [is that] it covers up the differences" [1].

The current diagnostic framework categorizes individuals based on severity levels of two core criteria: social communication difficulties and restricted, repetitive behaviors. However, these coarse groupings fail to capture the nuanced clinical presentations and varied developmental trajectories observed across the spectrum [1]. For decades, researchers have attempted to delineate meaningful subtypes that connect observable traits to underlying biological mechanisms, with limited success until recently. The critical barrier has been bridging the gap between the hundreds of genes associated with autism and their translation into specific autistic traits and developmental outcomes [1].

A transformative study published in Nature Genetics in July 2025 has successfully addressed this challenge through an innovative computational approach that integrates broad phenotypic data with genetic information from a large cohort of autistic individuals [2]. This research has identified four biologically distinct subtypes of autism, each defined by unique patterns of clinical presentation, developmental trajectory, and genetic architecture. These findings mark a paradigm shift from viewing autism as a single diagnostic entity toward understanding it as a collection of distinct disorders with shared core features but different underlying biological narratives [3].

Experimental Framework and Methodological Innovation

Cohort Characteristics and Data Collection

The research leveraged data from the SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research) cohort, the largest autism research study in the United States, which has enrolled over 150,000 autistic individuals and 200,000 family members since its inception [4]. The analysis focused on 5,392 autistic children aged 4-18 years, for whom both comprehensive phenotypic data and genetic information were available [2]. This sample size provided sufficient statistical power to detect robust patterns amid the inherent heterogeneity of autism.

The phenotypic data encompassed 239 meticulously defined item-level and composite features drawn from standardized diagnostic instruments and developmental assessments [2]. These included:

- Social Communication Questionnaire-Lifetime (SCQ): Assessing core social communication deficits characteristic of autism

- Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R): Measuring restricted and repetitive behaviors

- Child Behavior Checklist 6-18 (CBCL): Evaluating emotional, behavioral, and social problems

- Developmental history forms: Documenting milestone achievement and medical history

Genetic data comprised whole-exome or genome sequencing, enabling analysis of both common and rare variants across the coding regions of the genome [2].

Computational Approach: Person-Centered Mixture Modeling

The research team employed a generative finite mixture model (GFMM), a sophisticated computational approach that fundamentally differed from previous trait-centric analyses [2]. This methodology represented a critical innovation in several respects:

Table 1: Key Features of the Generative Finite Mixture Model

| Feature | Description | Advantage over Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type Handling | Simultaneously accommodated continuous, binary, and categorical data types | Eliminated need for data simplification that loses information |

| Person-Centered Approach | Maintained individual phenotypic profiles intact during analysis | Preserved natural co-occurrence patterns of traits within individuals |

| Probabilistic Classification | Assigned individuals to classes based on probability distributions | Acknowledged potential membership across multiple classes |

| Model Selection | Evaluated 2-10 latent classes using Bayesian information criterion and clinical interpretability | Balanced statistical rigor with clinical relevance |

The person-centered approach proved particularly significant, as it modeled the complex interplay of traits within individuals rather than analyzing isolated traits across populations [4]. As explained by Natalie Sauerwald, a co-lead author of the study, "Our goal with the person-centered approach is to maintain representation of the whole individual so that we can more fully model their complex spectrum of traits together" [4]. This methodology effectively captured the developmental reality that traits influence each other in complex ways, compensating for or exacerbating individual phenotypic measures throughout development [2].

The model's robustness was rigorously tested through multiple validation approaches, including stability analysis under perturbation and replication in an independent cohort (the Simons Simplex Collection), demonstrating consistent class structure across different populations [2].

The Four Autism Subtypes: Clinical and Genetic Profiles

The analysis revealed four distinct subtypes of autism, each demonstrating unique constellations of clinical features, developmental trajectories, and genetic architectures. These subtypes were not merely differentiated by severity but represented qualitatively different presentations with specific biological underpinnings.

Social and Behavioral Challenges Subtype

This group represented the largest subtype, comprising 37% of the study population [1] [3]. Clinically, these individuals exhibited significant difficulties with social communication and restrictive, repetitive behaviors, alongside elevated rates of co-occurring conditions including ADHD, anxiety disorders, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [1] [5]. Despite these challenges, children in this subgroup did not experience significant developmental delays, reaching milestones at ages comparable to non-autistic peers [1].

Genetically, this subtype showed a distinct profile characterized by:

- Enrichment of common genetic variants associated with psychiatric conditions such as ADHD and depression [5]

- Predominance of mutations in genes that become active after birth, particularly during childhood [3]

- Impact on genes expressed in brain cells involved in social and emotional processing [5]

- Lower burden of rare, damaging de novo mutations compared to other subtypes [3]

The postnatally active genetic signature aligns with the clinical presentation of typical early development followed by emerging behavioral and social challenges, and corresponds with later ages at diagnosis [3].

Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay Subtype

This heterogeneous subgroup accounted for 19% of the study population [1] [3]. Their clinical presentation was characterized by developmental delays in motor, language, and cognitive domains, alongside core autism symptoms [6]. Notably, these children showed significantly lower rates of anxiety, depression, and disruptive behaviors compared to other subtypes [3]. The "mixed" designation reflects the variable expression of repetitive behaviors and social challenges within this group [3].

Genetic features distinctive to this subtype included:

- Combination of both de novo and rare inherited variants [3] [5]

- Mutations predominantly affecting genes active during prenatal brain development [3]

- Strong association with language delays, intellectual disability, and motor disorders [3]

- Earlier age at diagnosis consistent with observable developmental concerns [3]

The genetic profile suggests a more complex inheritance pattern compared to other subtypes, with contributions from both spontaneously arising and familial genetic variants [5].

Moderate Challenges Subtype

Representing 34% of the cohort, this group exhibited milder manifestations across all core autism domains [1] [3]. While these individuals demonstrated more difficulties than non-autistic peers, their challenges were less pronounced than other autistic children [1]. They typically achieved developmental milestones on schedule and showed low rates of co-occurring psychiatric conditions [3] [6].

Genetic characteristics included:

- Lower burden of damaging genetic variants overall [3]

- Rare variants in genes less critical for fundamental neurological functioning [7]

- Gene expression patterns primarily active during fetal and neonatal development [7]

- Minimal association with known psychiatric genetic risk factors [5]

This subtype appears to represent a form of autism with less biological disruption, manifesting in milder clinical presentation.

Broadly Affected Subtype

The most severely impacted subgroup comprised 10% of the study population [1] [3]. These individuals presented with widespread challenges including significant developmental delays, severe social communication deficits, pronounced repetitive behaviors, and high rates of co-occurring psychiatric conditions [3] [6]. Medical and cognitive comorbidities included intellectual disability, language impairment, and mood dysregulation [3] [5].

The genetic signature of this subtype was marked by:

- Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations not inherited from parents [3] [5]

- Enrichment for mutations in genes crucial for early brain development [5]

- Association with genes linked to fragile X syndrome and other intellectual disability disorders [8]

- Genetic disruptions affecting both prenatal and postnatal developmental periods [7]

This profile aligns with the profound and multifaceted clinical challenges observed in this subgroup.

Table 2: Comprehensive Profile of the Four Autism Subtypes

| Characteristic | Social/Behavioral (37%) | Mixed ASD with DD (19%) | Moderate (34%) | Broadly Affected (10%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Social Challenges | Severe | Variable | Mild | Severe |

| Repetitive Behaviors | Severe | Variable | Mild | Severe |

| Developmental Milestones | Typical | Delayed | Typical | Delayed |

| Co-occurring ADHD/Anxiety | High | Low | Low | High |

| Intellectual Disability | Rare | Common | Rare | Common |

| Age at Diagnosis | Later | Earlier | Variable | Earliest |

| Genetic Signature | Common psychiatric variants | Rare inherited + de novo | Milder variants | High-impact de novo mutations |

| Key Biological Pathways | Postnatal synaptic signaling | Prenatal neurodevelopment | Diverse, mild impact | Proliferation, differentiation |

| Developmental Timing | Postnatal | Prenatal | Prenatal | Prenatal + Postnatal |

Distinct Genetic Architectures and Biological Pathways

The four autism subtypes demonstrated remarkable biological divergence, with minimal overlap in the specific molecular pathways affected in each subgroup [4]. As senior author Olga Troyanskaya noted, "To me, the biggest surprise was how different the four subtypes turned out to be... The underlying genetics and biology are very different" [1].

Subtype-Specific Genetic Risk Profiles

Comprehensive genetic analysis revealed distinct patterns of common and rare genetic variation across the subtypes:

Common Variant Contributions: The Social/Behavioral Challenges subtype showed the strongest influence of common genetic variants associated with psychiatric conditions like ADHD and depression, suggesting a shared genetic architecture with these disorders [5]. Notably, none of the subtypes demonstrated strong associations with common variants specifically linked to autism core features, highlighting the complexity of autism's genetic architecture [5].

Rare Variant Patterns: The Broadly Affected subtype carried the highest burden of rare, high-impact de novo mutations, particularly in genes critical for early brain development [5]. These mutations often occurred in genes previously associated with intellectual disability and severe developmental disorders [5]. The Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay subtype showed a combination of both de novo and rare inherited variants, indicating more complex inheritance patterns [3].

Temporal Expression Patterns: Critical differences emerged in the developmental timing of gene expression affected by subtype-specific mutations. In the Social/Behavioral subtype, mutated genes were predominantly active after birth, aligning with their clinical presentation of typical early development followed by emerging challenges [3]. Conversely, in subtypes with developmental delays (Mixed ASD with DD and Broadly Affected), mutations affected genes predominantly active during prenatal brain development [3].

Divergent Biological Pathways and Mechanisms

Pathway analysis revealed distinct biological narratives for each subtype, with minimal overlap between the molecular pathways affected:

Social/Behavioral Challenges Subtype: Showed enrichment for pathways involved in neuronal signaling, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter regulation, particularly in systems mature during childhood and adolescence [4] [5].

Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay Subtype: Demonstrated disruption in fundamental neurodevelopmental processes including neuronal migration, axon guidance, and cortical organization [4].

Broadly Affected Subtype: Exhibited the most widespread pathway disruptions, affecting basic cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, chromatin organization, and DNA repair mechanisms [3] [9].

The biological distinctions were so pronounced that Sauerwald analogized the challenge to "trying to put together a puzzle, but actually, you have four different puzzles mixed together, and you can't find any common pieces" [8]. This fundamental insight explains why previous studies seeking unified biological explanations for autism consistently encountered limited success.

Research Implications and Experimental Toolkit

This groundbreaking research was enabled by sophisticated methodological approaches and specialized resources that provide a toolkit for future investigations into autism heterogeneity:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Autism Subtype Investigations

| Resource/Technology | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Database | >150,000 autistic participants; genomic + deep phenotypic data [4] | Large-scale discovery cohort for subtype identification and validation |

| Generative Finite Mixture Models | Multimodal integration of continuous, categorical, and binary data [2] | Person-centered classification accommodating real-world data complexity |

| Simons Simplex Collection | Deeply phenotyped independent cohort with genomic data [2] | Replication cohort for validating subtype generalizability |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Comprehensive variant detection across coding regions [2] | Identification of rare inherited and de novo mutations |

| Polygenic Risk Scoring | Aggregate common variant contributions to psychiatric traits [5] | Quantifying shared genetic architecture with related conditions |

| Developmental Gene Expression Atlas | Brain transcriptome data across developmental timeline [3] | Mapping mutational impact to specific developmental periods |

| Pathway Enrichment Analysis | MSigDB Hallmark pathways and custom gene sets [9] | Identifying biological processes disrupted in each subtype |

Methodological Framework for Subtype Validation

The study established a rigorous methodological framework for identifying and validating biologically meaningful subtypes in heterogeneous neurodevelopmental conditions:

Data Integration Protocol: Standardized collection of 239 phenotypic features across diagnostic, behavioral, developmental, and medical domains, matched with genomic data [2].

Model Selection Criteria: Simultaneous optimization of statistical fit indices (Bayesian information criterion, validation log likelihood) and clinical interpretability when determining the optimal number of subtypes [2].

Biological Validation: Integration of genetic data only after phenotypic class establishment, ensuring unbiased confirmation of biological distinctness [2].

Cross-Cohort Replication: Application of classification models to independent cohorts (Simons Simplex Collection) to demonstrate generalizability beyond the discovery sample [2].

This framework provides a template for deconstructing heterogeneity in other complex neuropsychiatric conditions.

Discussion and Future Research Directions

The identification of four biologically distinct autism subtypes represents a paradigm shift in autism research with far-reaching implications for both basic science and clinical practice. Rather than searching for a unified biological explanation for autism, researchers can now investigate the distinct genetic and biological processes driving each subtype [3]. As noted by Chandra Theesfeld, co-author of the study, "This opens the door to countless new scientific and clinical discoveries" [3].

Research Implications

This refined understanding of autism heterogeneity enables more precisely targeted research approaches:

Gene Discovery: Focused analysis within subtypes increases power to identify subtle genetic effects that may be obscured in heterogeneous samples [4].

Pathway Validation: Subtype-specific biological pathways generate testable hypotheses regarding disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [4].

Developmental Modeling: The temporal alignment between gene expression patterns and clinical features enables more accurate modeling of developmental trajectories [3].

Preclinical Models: Development of animal and cellular models can now be guided by subtype-specific genetic and biological profiles, increasing translational relevance [9].

Clinical Applications and Precision Medicine

The subtyping framework holds significant promise for advancing precision medicine approaches in autism:

Diagnostic Refinement: Incorporating biological subtyping could complement behavioral diagnosis, providing more prognostically meaningful categorizations [1] [5].

Early Identification: Understanding subtype-specific developmental timelines could guide age-appropriate screening and monitoring protocols [3].

Treatment Targeting: Subtype-specific biological pathways offer targets for developing tailored interventions rather than one-size-fits-all approaches [10].

Prognostic Forecasting: Different subtypes demonstrate distinct developmental trajectories and outcomes, enabling more accurate long-term planning [3].

Limitations and Future Directions

While transformative, these findings represent a starting point rather than a complete nosology of autism. Important limitations and future directions include:

Ancestral Diversity: The current findings are based primarily on individuals of European ancestry, necessitating validation in more diverse populations [8]. Research suggests that certain genetic variations may occur at different frequencies across ancestries [8].

Subtype Expansion: As noted by the researchers, "This doesn't mean that there are only four classes" [4]. Larger samples and additional data modalities will likely reveal further subdivisions.

Longitudinal Dynamics: The current study provides a cross-sectional view; longitudinal tracking is needed to understand how subtypes evolve across the lifespan.

Non-Coding Variation: Future work incorporating the 98% of the genome that does not code for proteins may reveal additional regulatory mechanisms [4].

Neurobiological Validation: Integration of neuroimaging, electrophysiological, and postmortem data will strengthen the biological grounding of these subtypes.

This research fundamentally reorients our approach to autism heterogeneity, providing a robust framework for understanding its biological diversity and advancing toward personalized approaches to care and treatment. As concluded by the researchers, "The ability to define biologically meaningful autism subtypes is foundational to realizing the vision of precision medicine for neurodevelopmental conditions" [3].

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by significant heterogeneity in its clinical presentation and underlying genetic architecture. Historically, the search for a unified biological explanation has been challenging due to the diverse phenotypic manifestations and multifactorial etiology. The condition's core features encompass persistent deficits in social communication and interaction alongside restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [11]. For decades, researchers have sought to parse this heterogeneity by linking the varying observable traits, or phenotypes, to specific genetic underpinnings [4].

The emerging paradigm in autism research recognizes that what is clinically diagnosed as autism likely comprises multiple biologically distinct conditions, each with unique developmental trajectories and genetic profiles. The integration of large-scale genomic data with deep phenotypic information has enabled a more nuanced understanding of these subtypes. This whitepaper synthesizes recent advances in deconstructing the genetic architecture of autism subtypes, focusing specifically on the distinct roles of de novo versus inherited variants and their interplay with polygenic risk profiles. Furthermore, it frames these findings within the context of biochemical pathways implicated in autism pathogenesis, providing a mechanistic foundation for targeted therapeutic development.

Subtype Classification: Phenotypic and Genetic Heterogeneity

Data-Driven Subtype Identification

Recent large-scale studies have employed person-centered computational approaches to identify robust autism subtypes based on comprehensive phenotypic data. One seminal analysis of the SPARK cohort (n=5,392) utilized a general finite mixture model (GFMM) to analyze 239 phenotypic features, identifying four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes [3] [2]. This person-centered approach maintains the representation of the whole individual, modeling the complex spectrum of traits together rather than fragmenting individuals into separate phenotypic categories [2].

Table 1: Clinically Distinct Subtypes of Autism

| Subtype | Prevalence | Core Phenotypic Features | Developmental Milestones | Common Co-occurring Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | ~37% | Prominent social challenges, repetitive behaviors, communication difficulties | Typically reached at pace similar to children without autism | ADHD, anxiety disorders, depression, OCD, mood dysregulation |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | ~19% | Mixed social/repetitive behavior profiles, strong enrichment of developmental delays | Reached later than peers without autism | Language delay, intellectual disability, motor disorders |

| Moderate Challenges | ~34% | Core autism behaviors present but less pronounced | Typically reached at pace similar to children without autism | Generally absence of co-occurring psychiatric conditions |

| Broadly Affected | ~10% | Widespread challenges across all measured domains | Significant developmental delays | Anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation, multiple co-occurring conditions |

The four-class model demonstrated optimal balance across multiple statistical fit measures, including Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and validation log likelihood, while offering strong clinical interpretability [2]. This classification system has been successfully replicated in the independent Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) cohort, confirming the robustness of these subtypes across different populations [2].

Developmental Trajectories and Age at Diagnosis

Longitudinal analyses across multiple birth cohorts have revealed distinct developmental trajectories associated with age at autism diagnosis. Growth mixture modeling of socioemotional and behavioral development using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) has identified two primary latent trajectories [12]:

- Early Childhood Emergent Trajectory: Characterized by difficulties in early childhood that remain stable or modestly attenuate in adolescence.

- Late Childhood Emergent Trajectory: Characterized by fewer difficulties in early childhood that increase in late childhood and adolescence.

Autistic individuals in the early childhood emergent trajectory are more likely to receive diagnosis in childhood, while those in the late childhood emergent trajectory tend toward later diagnosis [12]. These trajectory differences explain a substantial portion (11.7%-30.3%) of the variance in age of autism diagnosis, surpassing the explanatory power of sociodemographic variables (4.8%-5.5%) [12].

Genetic Architecture of Autism Subtypes

Distinct Variant Profiles Across Subtypes

The identified autism subtypes demonstrate divergent genetic architectures, with varying contributions of de novo and inherited variation across subgroups.

Table 2: Genetic Profiles Across Autism Subtypes

| Subtype | De Novo Mutations | Inherited Variants | Polygenic Architecture | Key Biological Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | Lower proportion | Moderate burden | Later-onset genetic factor (rg=0.38) correlated with ADHD/mental health conditions | Genes active after birth; neuronal function |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | Moderate proportion | Highest burden of rare inherited protein-truncating variants | Earlier-onset genetic factor | Prenatally active genes; chromatin organization |

| Moderate Challenges | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported |

| Broadly Affected | Highest proportion | Moderate burden | Not specifically reported | Multiple pathways; widespread disruption |

The Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype shows a distinct genetic signature characterized by mutations in genes that become active after birth, aligning with their typical developmental milestones and later average age of diagnosis [3]. Conversely, the Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay subtype demonstrates enrichment for rare inherited variants affecting genes predominantly active prenatally [3].

In multiplex families (families with multiple autistic individuals), autistic children show an increased burden of rare inherited protein-truncating variants in known ASD risk genes [13]. Furthermore, ASD polygenic score (PGS) is overtransmitted from nonautistic parents to autistic children who also harbor rare inherited variants, suggesting combinatorial effects that may explain the reduced penetrance of these rare variants in parents [13].

Polygenic Risk Stratification

Common genetic variants account for approximately 11% of the variance in age at autism diagnosis, similar to the contribution of individual sociodemographic and clinical factors [12]. The polygenic architecture of autism can be decomposed into two modestly genetically correlated (rg = 0.38, s.e. = 0.07) polygenic factors [12]:

- Factor 1: Associated with earlier autism diagnosis, lower social and communication abilities in early childhood, and moderate genetic correlations with ADHD and mental health conditions.

- Factor 2: Associated with later autism diagnosis, increased socioemotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence, and moderate to high positive genetic correlations with ADHD and mental-health conditions.

These findings support a developmental model wherein earlier- and later-diagnosed autism have different underlying developmental trajectories and polygenic architectures, rather than a unitary model where the same genetic factors operate across the spectrum [12].

Experimental Methodologies

Cohort Recruitment and Phenotyping

SPARK Cohort Protocol: The SPARK study represents the largest autism cohort to date, engaging over 150,000 autistic individuals and 200,000 family members [4]. Recruitment employs nationwide outreach with online registration and consent procedures. Phenotypic assessment includes:

- Diagnostic Questionnaires: Social Communication Questionnaire-Lifetime (SCQ), Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R), Child Behavior Checklist 6-18 (CBCL) [2].

- Developmental History: Comprehensive background history form focusing on developmental milestones [2].

- Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidity Assessment: Structured reporting of diagnosed co-occurring conditions including ADHD, anxiety, depression, and language delays [2].

Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) Protocol: The SSC comprises approximately 2,600 simplex families (families with one autistic child and unaffected parents and siblings) [2]. Phenotypic characterization includes:

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS): Administered by research-reliable clinicians.

- Cognitive and Adaptive Behavior Assessments: Full-scale IQ, verbal and non-verbal IQ, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales.

- Medical and Genetic History: Detailed medical history and physical examination [2].

Genomic Sequencing and Analysis

Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: High-molecular-weight DNA extracted from saliva or blood samples using standardized kits [13] [11].

- Library Preparation: Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit for 350 bp insert sizes [13].

- Sequencing: Illumina HiSeq X platform at 30x mean coverage [13].

- Variant Calling: GATK Best Practices pipeline for SNP and indel calling; rare variant filtering (<0.1% frequency in gnomAD) [13].

De Novo Mutation Detection:

- Trio-Based Analysis: Sequencing of autistic child and both biological parents [13] [2].

- Denovo Filtering: DenovoGear and custom scripts requiring variants to be absent in both parents, present in child, and satisfying depth and quality thresholds [13].

- Validation: Sanger sequencing or deep resequencing of putative de novo variants [13].

Inherited Variant Analysis:

- Rare Inherited Variant Identification: Segregation analysis in multiplex families; protein-truncating variants (PTVs) prioritized [13].

- Burden Testing: Comparison of variant burden in cases versus controls using optimized sequence kernel association test (SKAT-O) [13].

- Gene-Based Association: Combined analysis with external datasets using meta-analysis approaches [13].

Statistical Modeling and Classification

General Finite Mixture Model (GFMM):

- Model Framework: Generative mixture model accommodating heterogeneous data types (continuous, binary, categorical) without assuming normal distributions [2].

- Feature Selection: 239 item-level and composite phenotype features representing responses on standard diagnostic questionnaires [2].

- Class Determination: Model selection based on Bayesian information criterion (BIC), validation log likelihood, and clinical interpretability for 2-10 latent classes [2].

- Validation: Internal stability testing via bootstrap resampling and external replication in independent cohort [2].

Growth Mixture Modeling for Developmental Trajectories:

- Data Source: Longitudinal Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scores from birth cohorts (Millennium Cohort Study, Longitudinal Study of Australian Children) [12].

- Model Fitting: Maximum likelihood estimation with full-information maximum likelihood to handle missing data [12].

- Class Assignment: Posterior probabilities for trajectory class membership; association with age at diagnosis via chi-square tests [12].

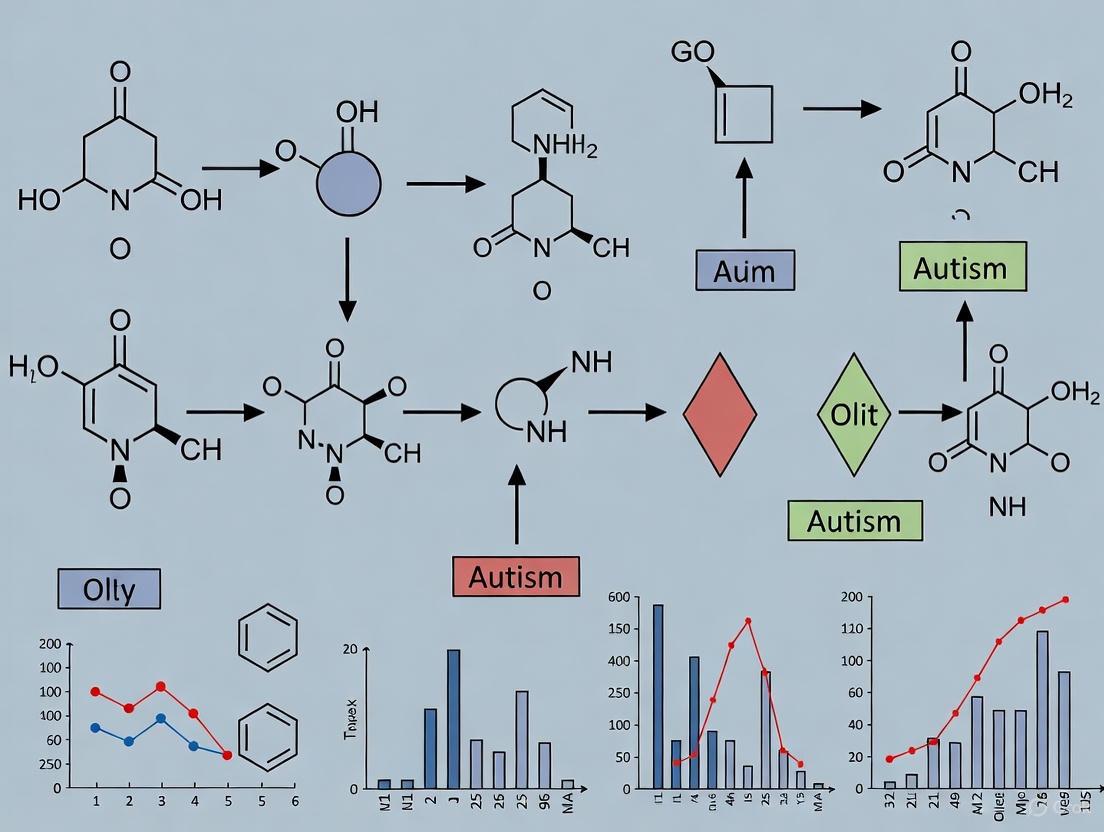

Pathway Visualization and Biochemical Mechanisms

Genetic Subtype Pathway Diagram

Experimental Workflow for Genetic Subtyping

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Product/Assay | Application in Autism Genetics Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Collection | Oragene DNA Self-Collection Kit | Non-invasive saliva collection for large-scale cohort genomic DNA extraction |

| Sequencing Library Prep | Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Preparation of WGS libraries with minimal bias for variant detection |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq X Ten System | High-throughput sequencing at 30x coverage for comprehensive variant discovery |

| Variant Calling | GATK Best Practices Pipeline | Identification of SNVs, indels, and structural variants from WGS data |

| De Novo Detection | DenovoGear Software Package | Statistical framework for identifying de novo mutations from trio sequencing data |

| Phenotypic Assessment | Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) | Standardized measure of autism symptoms and social communication deficits |

| Behavioral Phenotyping | Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) | Quantification of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities |

| Psychiatric Comorbidity | Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) | Assessment of emotional, behavioral, and social problems across developmental periods |

| Statistical Modeling | R mclust Package | Implementation of general finite mixture models for subtype identification |

| Pathway Analysis | Enrichr Web Tool | Functional enrichment analysis of gene sets against multiple biological databases |

The decomposition of autism heterogeneity into biologically meaningful subtypes represents a transformative advance in neurodevelopmental disorder research. The distinct genetic architectures underlying these subtypes—varying in their balance of de novo versus inherited variants and their polygenic risk profiles—provide a new framework for understanding autism pathogenesis. Critically, the identification of subtype-specific biochemical pathways and developmental timelines enables a precision medicine approach to autism research and therapeutic development.

Future directions should focus on expanding diverse cohort representation, integrating non-coding genomic variation, and developing subtype-specific cellular models for functional validation. The continued convergence of deep phenotyping, advanced genomics, and computational biology promises to accelerate the translation of these genetic findings into targeted interventions that address the specific biological mechanisms underlying each autism subtype.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [14]. The pathological framework of ASD is increasingly understood through the lens of specific biochemical pathway disruptions that converge during critical neurodevelopmental windows. Current research reveals that heterogeneous genetic risk factors funnel into convergent biological pathways, primarily affecting neuronal signaling, chromatin remodeling, and cellular metabolism [15] [16]. This whitepaper synthesizes recent advances in understanding these core pathway disruptions, providing a technical resource for researchers and therapeutic developers. We examine the specific mechanisms within each pathway category, present quantitative multi-omics findings, detail experimental methodologies for pathway analysis, and discuss the implications for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Neuronal Signaling Pathway Disruptions

Core Signaling Systems Implicated in ASD

The intricate balance of neuronal communication is frequently disrupted in ASD, with particular impact on synaptic organization, excitatory-inhibitory balance, and neuromodulatory systems. Large-scale genomic studies have identified enrichment of risk genes in two primary functional categories: neuronal communication (NC) and gene expression regulation (GER) [15].

Synaptic Gene Networks: Early genomic investigations identified recurrent de novo copy number variants (CNVs) affecting pivotal synaptic scaffolding and adhesion molecules, including NRXN1, NLGN3, NLGN4X, SHANK2, SHANK3, and SYNGAP1 [15]. These genes encode proteins critical for organizing the postsynaptic density and maintaining proper synaptic adhesion. SHANK3 in particular functions as a master scaffolding protein at excitatory synapses, anchoring glutamate receptors and associated signaling complexes. Haploinsufficiency of SHANK3 disrupts this molecular architecture, leading to aberrant synaptic transmission and plasticity, which manifests as core ASD phenotypes in model systems [15].

Excitatory/Inhibitory Imbalance: A fundamental pathophysiological hypothesis in ASD suggests altered balance between excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) signaling. This imbalance stems from disruptions in genes controlling the development, maintenance, and function of these systems [17]. The proper maturation of GABAergic circuits is especially vulnerable, potentially leading to network hyperexcitability.

Purinergic Signaling: Emerging evidence positions purinergic signaling as a central regulator of ASD-associated network dysfunction. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate (eATP) functions as a potent signaling molecule that binds purinergic receptors on virtually every cell type, initiating a cascade known as the Cell Danger Response (CDR) [18]. Chronic disruption of this system has far-reaching consequences:

- Metabolic Dysregulation: eATP release triggers mitochondrial reprogramming, increasing oxidative stress and altering energy metabolism [18].

- Immune Activation: eATP is a powerful activator of microglia and innate immune responses, contributing to neuroinflammation [18].

- Synaptic Plasticity: Purinergic receptors directly modulate synaptic strength and plasticity mechanisms [18].

Developmental studies reveal that the purine metabolic network shows profoundly altered regulation in ASD. Hub analysis of the purine network shows a characteristic 17-fold reversal during typical development that fails to occur in ASD, indicating a fundamental disruption in purinergic signaling maturation [18].

Table 1: Key Neuronal Signaling Genes and Their Functional Roles in ASD

| Gene | Protein Function | Biological Process | Impact of Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHANK3 | Postsynaptic scaffold protein | Synaptic organization & glutamate receptor anchoring | Haploinsufficiency disrupts excitatory synaptic transmission and plasticity [15] |

| NRXN1 | Presynaptic cell adhesion | Synapse formation & maintenance | Disrupted trans-synaptic signaling, impairing circuit assembly [15] |

| SYNGAP1 | RAS/RAP GTPase activator | Synaptic plasticity & dendritic spine maturation | Haploinsufficiency alters spine dynamics, causing E/I imbalance [15] |

| SCN2A | Voltage-gated sodium channel | Neuronal action potential generation | Altered neuronal excitability and network synchronization [3] |

Experimental Analysis of Neuronal Signaling Defects

Electrophysiological Protocols:

- Brain Slice Patch-Clamp Recording: Acute hippocampal or cortical slices (300-400 µm) prepared from ASD model mice (e.g.,

Chd8+/- orShank3+/-) at relevant developmental stages (e.g., P14-P21, P56-P70). Recordings target principal neurons in specific layers (e.g., L5 PFC pyramidal neurons) or cerebellar Purkinje cells. Measure miniature excitatory/inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs/mIPSCs) in voltage-clamp mode (Vhold = -70 mV for mEPSCs, +10 mV for mIPSCs) with tetrodotoxin (1 µM) in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) to isolate action-potential-independent release. Analyze amplitude, frequency, and kinetics of events to assess synaptic strength, presynaptic release probability, and receptor composition [16]. - Field Potential Recording: Assess long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse. Deliver test stimuli to establish baseline fEPSP slope, then apply conditioning protocols (e.g., 100 Hz tetanus for LTP, 1 Hz for LTD). Compare the magnitude and persistence of plasticity between genotypes.

Figure 1: Neuronal Signaling Disruptions in ASD. This diagram illustrates key presynaptic (NRXN1) and postsynaptic (NLGN3/4X, SHANK3, SYNGAP1) protein interactions crucial for synaptic adhesion, scaffolding, and glutamate receptor anchoring. Disruption leads to altered excitatory synaptic potential. Extracellular ATP (eATP) signaling via P2R purinergic receptors triggers the Cell Danger Response (CDR) and microglial activation, contributing to neuroinflammation [18] [15].

Chromatin Remodeling and Transcriptional Dysregulation

Epigenetic Mechanisms in ASD Pathogenesis

Chromatin remodeling complexes, which dynamically regulate DNA accessibility and gene expression, are central players in ASD etiology. Mutations in genes encoding components of these complexes, particularly the SWI/SNF (BAF) complex, are among the most significant genetic risk factors for ASD [14] [15].

Master Regulator: CHD8 The gene encoding CHD8 is one of the most prominent ASD-associated genes, functioning as an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler [16]. CHD8 haploinsufficiency produces a recognizable ASD subtype often accompanied by macrocephaly, establishing it as a high-penetrance risk factor.

- Network-Level Influence: CHD8 acts as a master transcriptional regulator during early cortical development, controlling the proliferation of neural progenitors, cell fate specification, and synaptic maturation [16]. Its broad regulatory scope means that disruption cascades across multiple developmental stages and cell types.

- Cerebellar Impact: Single-nucleus transcriptomic and chromatin accessibility profiling in

Chd8+/- models reveal significant vulnerabilities in specific cerebellar cell populations, including Purkinje neurons, oligodendrocytes, and interneurons. These changes are accompanied by transcriptional signatures linked to synaptic regulation, RNA processing, and mitochondrial function, extending the pathology beyond the cerebral cortex [16].

Convergent Transcriptional Networks: Multiple high-confidence ASD genes converge on co-expression networks active during mid-fetal development in deep-layer cortical projection neurons [15]. These include:

ARID1B: A component of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex that modulates accessibility in excitatory neurons and interneurons.FOXP1: A transcription factor that regulates neuronal gene expression and converges withARID1Bat shared genomic targets.TBR1: A key transcription factor participating in the same midgestational transcriptional network.

These factors collectively regulate a critical period of transcriptional programming that, when disrupted, alters cortical lamination, neuronal migration, and circuit formation [15]. Post-mortem studies have identified patches of cortical disorganization in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of children with ASD, supporting the notion of early developmental disruption [14].

Table 2: Chromatin Remodeling Genes and Their Functional Consequences in ASD

| Gene/Complex | Molecular Function | Neurodevelopmental Role | Consequence of Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHD8 | ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler | Master regulator of neurodevelopmental gene expression; controls progenitor proliferation | Haploinsufficiency alters cerebellar development & cortical circuits; linked to macrocephaly [16] |

| SWI/SNF (BAF) Complex (e.g., ARID1B) | Nucleosome positioning & chromatin accessibility | Neural fate specification, neuronal migration | Altered chromatin accessibility in cortical neurons, disrupted cortical lamination & E/I balance [15] |

| FOXP1 | Transcription factor | Neuronal gene expression regulation | Disrupts shared genomic targets with ARID1B and TBR1 in fetal cortex [15] |

Methodologies for Profiling Chromatin Landscapes

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Protocols:

- snRNA-seq + snATAC-seq Co-assay: Isolate nuclei from fresh-frozen post-mortem brain tissue (e.g., dorsolateral PFC or cerebellum) from ASD and control donors. Using a commercial platform (e.g., 10x Multiome), perform simultaneous snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq on the same nuclei. For snATAC-seq: tagment nuclei with Tn5 transposase, amplify libraries, and sequence. For snRNA-seq: capture and reverse-transcribe polyA+ RNA, then amplify and sequence. Bioinformatically map accessible chromatin regions (peaks) and gene expression to specific cell types (excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, oligodendrocytes, microglia) [16].

- Data Integration & Analysis: Cluster cells based on gene expression and chromatin accessibility. Identify differentially accessible regions (DARs) and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in ASD versus control within each cell type. Link putative regulatory elements (enhancers) to target genes based on correlation between accessibility and expression. Overlap DARs with known ASD-associated genetic variants from GWAS and WGS studies to prioritize functional non-coding disruptions [15] [16].

Figure 2: Chromatin Remodeling Disruption Cascade. This workflow depicts the sequence by which mutations in high-penetrance ASD risk genes (e.g., CHD8, ARID1B) dysregulate chromatin remodeling complexes, leading to altered chromatin accessibility and aberrant transcriptional programs during critical neurodevelopmental windows. This disruption impacts both cortical and cerebellar development, ultimately contributing to ASD phenotypes [15] [16].

Metabolic Pathway Dysregulation

Systemic Metabolic Impairments in ASD

Metabolic dysfunction in ASD extends beyond the brain, exhibiting characteristic signatures in peripheral biofluids that reflect systemic alterations in energy metabolism, antioxidant defense, and lipid handling.

Purine Metabolism and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A core metabolic disruption in ASD involves the purine metabolic network, which is intrinsically linked to mitochondrial function [18].

- Developmental Dysregulation: In typically developing children, the purine network undergoes a characteristic 17-fold reversal during early childhood. This developmental switch fails to occur in children with ASD, indicating a arrested maturational program in one of the most fundamental metabolic pathways [18].

- Mitochondrial Involvement: Mitochondria produce over 90% of cellular ATP and contain approximately half of all metabolic enzymes, many regulated by ATP and related nucleotides. Chronic mitochondrial dysfunction is a well-established feature of ASD that can remodel the entire metabolic network, influence gene expression, and shift neurodevelopmental trajectories [18].

Altered Lipid Metabolism and Antioxidant Defenses: Cross-sectional studies of newborns who later develop ASD (pre-ASD) and 5-year-old children with ASD reveal consistent alterations in lipid metabolism and redox homeostasis.

- Shared Pathway Impact: Fourteen core biochemical pathways account for approximately 80% of the metabolic impact in both pre-ASD newborns and 5-year-olds with ASD [18].

- Lipid Metabolism Dominance: Altered lipid metabolism accounts for 63-71% of the total metabolic impact, with sphingolipids (ceramides, sphingomyelins) and phospholipids being particularly affected [18].

- Redox Imbalance: There is a consistent decrease in anti-inflammatory and antioxidant defenses, coupled with increased levels of physiological stress molecules including lactate, glycerol, glycerol-3-phosphate, cholesterol, and ceramides [18].

Table 3: Key Metabolic Pathway Disruptions in ASD Development

| Metabolic Pathway | Change in Pre-ASD Newborns | Change in 5-Year-Olds with ASD | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purine Metabolism | Altered network regulation | Failed developmental reversal (17-fold) | Dysregulated purinergic signaling & CDR; arrested maturation [18] |

| Sphingolipid Metabolism | ↑ Ceramides, ↑ Sphingomyelins (25% of impact) | ↑ Ceramides, ↑ Sphingomyelins (25% of impact) | Increased cellular stress, altered membrane integrity, & signaling [18] |

| Phospholipid Metabolism | ↑ Key phospholipids (20% of impact) | ↑ Key phospholipids (26% of impact) | Membrane remodeling, inflammation, and signaling defects [18] |

| Antioxidant Defenses | ↓ Glutathione-related metabolites | ↓ Glutathione-related metabolites | Increased oxidative stress & vulnerability to inflammation [18] |

| Lactate & Alanine | ↑ Levels | ↑ Levels (54% greater than newborns) | Increased glycolytic flux & physiologic stress [18] |

Metabolomic Profiling and Network Analysis

Protocol: LC-MS/MS Based Metabolomics:

- Sample Preparation: Collect EDTA plasma from cohort participants (e.g., pre-ASD newborns, 5-year-old children with ASD, and matched typically developing controls). Deproteinize samples using cold methanol (1:3 sample:methanol ratio), vortex, and centrifuge (14,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C). Transfer supernatant and dry under nitrogen. Derivatize if analyzing certain lipid classes [18].

- Liquid Chromatography Separation: Use a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm) with a binary gradient. Mobile phase A: 10 mM ammonium acetate in water with 0.1% formic acid. Mobile phase B: 10 mM ammonium acetate in 90% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Use a gradient from 5% B to 100% B over 15-20 minutes. Maintain column temperature at 40°C [18].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Operate a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF) in both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes. Set source temperature to 150°C, desolvation temperature to 500°C, and capillary voltage to 3.0 kV. Use data-independent acquisition (MSE) to fragment all ions for MS/MS spectral matching [18].

- Data Processing & Network Analysis: Process raw data using vendor software for peak picking, alignment, and compound identification against commercial databases (e.g., HMDB, LipidMaps). Perform multivariate statistical analysis (PLS-DA) to identify discriminating metabolites (VIP ≥ 1.5). Calculate z-scores for significantly altered metabolites. Construct metabolic networks and calculate novel parameters like ( \dot{V}_{\text{net}} ) to quantify differences in network connectivity and hub structure between ASD and control groups [18].

Figure 3: Integrated Metabolic Dysregulation in ASD. Genetic and environmental stressors trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, which disrupts purine metabolism and increases extracellular ATP (eATP) release. This initiates a chronic Cell Danger Response (CDR), driving lipid metabolism dysregulation (increased ceramides, phospholipids) and oxidative stress (reduced antioxidant defenses). These interconnected metabolic disturbances collectively contribute to altered neurodevelopment and neural function [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Investigating ASD Pathways

| Reagent / Resource | Specific Example (Catalog # if possible) | Research Application | Key Function in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Data | SPARK (Simons Foundation) [3] [2] | Genotype-Phenotype Correlation | Largest U.S. ASD cohort; provides integrated WGS & deep phenotypic data for >5, 000 individuals for subtype discovery [3] [2] [4] |

| General Finite Mixture Model (GFMM) | Custom R/Python implementation [2] | Phenotypic Decomposition | Person-centered computational approach to identify clinically relevant ASD subtypes based on >230 trait combinations [2] |

| snRNA-seq + snATAC-seq Kits | 10x Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression | Single-Cell Multi-Omics | Simultaneously profiles chromatin accessibility & gene expression in same nucleus; identifies cell-type-specific regulatory disruptions in post-mortem brain [16] |

| LC-MS/MS Metabolomics Platform | Agilent 6495C QQQ or Thermo Q Exactive HF-X | Metabolic Phenotyping | Quantifies ~450 polar & lipid metabolites; identifies dysregulated pathways (e.g., purine, lipid metabolism) in plasma/serum [18] |

| CHD8 Haploinsufficiency Mouse Model | Chd8+/- (JAX Stock #) |

In Vivo Functional Validation | Models a high-penetrance monogenic ASD form; used for electrophysiology, behavior, and multi-omics studies, especially cerebellar [16] |

| Transmission and De Novo Association (TADA) | TADA R package | Statistical Genetics | Bayesian framework for identifying ASD-risk genes by integrating de novo and rare inherited variant burden from WES/WGS data [15] |

The pathogenesis of Autism Spectrum Disorder is increasingly understood through discrete yet interconnected biochemical pathway disruptions. Research now demonstrates that heterogeneous genetic risks funnel into convergent biological narratives affecting chromatin remodeling, neuronal signaling, and metabolic regulation [14] [15] [16]. The recent decomposition of ASD into biologically distinct subtypes represents a paradigm shift, moving the field beyond a "one-size-fits-all" model toward a precision medicine framework [3] [2] [4].

Future research must prioritize several key areas:

- Non-Coding Genome Integration: Expanding analyses to include the 98% of the genome that does not code for proteins will likely reveal additional regulatory disruptions contributing to ASD heterogeneity [15] [4].

- Developmental Timeline Mapping: Precise temporal mapping of when and where specific pathway disruptions exert their effects will be crucial for identifying critical intervention windows [3] [2].

- Therapeutic Translation: The identification of subtype-specific biological narratives, such as distinct pathway disruptions in the "Social and Behavioral Challenges" versus "Broadly Affected" subgroups, provides a rational foundation for developing targeted, mechanism-based therapies [3] [2] [4].

By leveraging large-scale multi-omics datasets, advanced computational models, and precise experimental systems, researchers are now equipped to dissect the complex architecture of ASD pathogenesis and develop interventions that target its root biological causes.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [19]. Research from the past decade has revolutionized our understanding of ASD's origins, revealing it to be a multistage prenatal disorder that impacts a child's ability to perceive and react to social information [20]. Rather than beginning in early childhood, ASD is now understood as a highly heritable, brain-wide disorder of prenatal and early postnatal development, with most ASD risk genes expressing prenatally and falling into two functional categories: broadly expressed regulatory genes and brain-specific genes [20]. The developmental timeline of these genetic risk programs is not uniform; instead, it follows specific epochs of vulnerability that profoundly influence brain development and clinical outcomes.

The prenatal origin of ASD is supported by multiple lines of evidence. Postmortem studies of young ASD cases reveal an overabundance of cortical neurons—on average, 67% more prefrontal neurons than controls—which must originate during prenatal neurogenesis since cortical neuron proliferation occurs primarily between 10 and 20 weeks of gestation [20]. Furthermore, in utero brain overgrowth is a recognized phenomenon in ASD, and focal disorganization of cortical layers provides evidence of disrupted second and third-trimester development [20]. This review examines the precise developmental timing of genetic risk program activation within the context of biochemical pathway dysregulation, providing a technical framework for researchers investigating ASD pathogenesis and therapeutic development.

Genetic Risk Programs: Prenatal vs. Postnatal Expression Patterns

Temporal Expression of ASD Risk Genes

The majority of high-confidence ASD (hcASD) risk genes exhibit predominant prenatal expression, with their peak influence aligning with specific developmental processes [20]. Analysis of gene expression patterns reveals two primary epochs of vulnerability during neurodevelopment:

- Epoch-1 (68% of ASD genes): Spanning trimesters 1-3, involving broadly expressed regulatory genes (the majority) and brain-specific genes that disrupt cell proliferation, neurogenesis, migration, and cell fate [20].

- Epoch-2 (32% of ASD genes): Spanning trimester 3 and early postnatal periods, involving primarily brain-specific genes that disrupt neurite outgrowth, synaptogenesis, and cortical "wiring" [20].

Recent genetic studies of 102 putative ASD risk genes found that 98 had their highest expression in prenatal cortex compared with postnatal development [20]. This prenatal predominance is consistently observed across multiple brain regions implicated in ASD, including cortex, cerebellum, amygdala, hippocampus, and striatum [20].

Table 1: Developmental Timeline of ASD Risk Gene Expression and Primary Functions

| Developmental Period | % of hcASD Genes | Primary Gene Categories | Key Disrupted Processes | Associated Brain Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoch-1 (Trimesters 1-3) | 68% | Broadly-expressed regulatory (majority), Brain-specific | Cell proliferation, Neurogenesis, Migration, Cell fate | Cortex, Cerebellum, Amygdala, Hippocampus, Striatum |

| Epoch-2 (Trimester 3-Early Postnatal) | 32% | Brain-specific (majority) | Neurite outgrowth, Synaptogenesis, "Wiring" of cortex | Cortex, Hippocampus |

Functional Classification of ASD Risk Genes

ASD risk genes demonstrate significant functional pleiotropy, with approximately two-thirds influencing two or more neurodevelopmental processes [20]. A recent literature survey of 58 functionally characterized hcASD genes revealed their involvement across multiple prenatal stages:

- 57% are involved in proliferation

- 26% in migration and cell fate specification

- 52% in neurite outgrowth

- 59% in synaptogenesis and synapse functioning [20]

This pleiotropy adds a genetic explanation to the developmental pathobiology revealed by postmortem, neuroimaging, and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) studies, showing that ASD risk genes collectively impact excess cell proliferation, disrupted neurogenesis and maturation, mis-migration, disrupted synaptic development and function, and deviant neurofunctional activity and connectivity [20].

Table 2: Functional Roles of Characterized ASD Risk Genes in Neurodevelopmental Processes

| Neurodevelopmental Process | % of Characterized hcASD Genes Involved | Specific Functions Disrupted | Consequence of Dysregulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | 57% | Cell cycle regulation, G1/S transition, Apoptosis | Excess neurons, Brain overgrowth, Early overgrowth |

| Migration & Cell Fate | 26% | Neuronal positioning, Cortical layer formation | Focal cortical dyslamination, Mis-migrated neurons |

| Neurite Outgrowth | 52% | Axon guidance, Dendritic arborization | Reduced neuron size, Altered connectivity |

| Synaptogenesis & Function | 59% | Spine formation, Synapse maturation, Neural activity | Excitation/inhibition imbalance, Network dysfunction |

Biochemical Pathways in ASD Pathogenesis

Key Signaling Pathways Disrupted in ASD

The mechanistic basis of ASD involves dysregulation of core signaling pathways that coordinate neurodevelopment. Upstream highly interconnected regulatory ASD gene mutations disrupt transcriptional programs or signaling pathways, resulting in dysregulation of downstream processes such as proliferation, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and neural activity [20]. Pathway analysis has identified several key pathways consistently implicated in ASD pathogenesis:

- Chromatin remodeling pathways: Involving changes in DNA and histone structure that regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself, significantly impacting neuronal differentiation and synapse formation [14].

- Wnt and Notch signaling pathways: Critical for brain development and neuroplasticity, with dysregulation leading to altered cell fate determination and circuit formation [14].

- Redox system dysfunction: A progressive maladaptation where reactive oxidant species, molecular targets, and reducing/antioxidant counterparts function as dynamic circuitry whose disruption undermines cellular homeostasis [21].

- ARP2/3 mediated actin dynamics: Regulated by genes such as CYFIP1, which interacts with WAVE1 to modulate actin branching, affecting cell survival and migration of newborn neurons [22].

These pathways do not operate in isolation but form an interconnected network that guides proper brain development. Dysregulation at specific developmental timepoints can create cascading effects that manifest as ASD symptomatology.

Diagram: Signaling Pathways in ASD Neurodevelopment

Experimental Models and Methodologies

iPSC Models of Idiopathic ASD

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) studies have provided direct insights into prenatal origins in idiopathic ASD, revealing disruptions across multiple developmental stages [20].

Experimental Protocol: iPSC to Neuron Differentiation

Primary Research Objective: To model early neurodevelopmental processes disrupted in ASD using patient-derived iPSCs.

Methodology Details:

- iPSC Generation: Dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells from ASD individuals and healthy controls are reprogrammed using non-integrating Sendai virus vectors containing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC.

- Neural Induction: iPSCs are differentiated into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) using dual SMAD inhibition (LDN-193189 and SB431542) in neural induction medium for 10-14 days.

- Neuronal Differentiation: NPCs are dissociated and plated on poly-ornithine/laminin-coated surfaces in neuronal differentiation medium containing BDNF, GDNF, cAMP, and ascorbic acid for 4-8 weeks.

- Functional Analysis: Neurons are analyzed at multiple timepoints for morphological, molecular, and functional properties.

Key Parameters Assessed:

- Cell proliferation: Measured via EdU incorporation assays and Ki67 immunostaining at NPC stage

- Cell cycle analysis: Flow cytometry for G1/S phase duration

- Neuronal differentiation: Quantified by Tuj1/TBR1/CTIP2 immunostaining

- Synaptic maturation: Analyzed via synapsin/PSD95 staining and electrophysiology

- Neural activity: Measured using calcium imaging or multi-electrode arrays

Representative Findings: In the largest iPSC study to date (n=8 ASD, n=5 controls), every ASD child showed disruptions in multiple prenatal stages including proliferation, maturation, synaptogenesis, and neural activity [20]. Specifically, ASD cells displayed high rates of cell proliferation, G1/S shortening, reduced differentiation and neuronal maturation, abnormal inhibitory and excitatory synaptic maturation, and reduced neural activity [20].

Animal Models of Genetic Risk Factors

Animal models, particularly rodents, provide critical platforms for investigating the temporal requirements of ASD gene function and testing therapeutic interventions.

Experimental Protocol: Cyfip1 Haploinsufficiency Model

Primary Research Objective: To investigate how haploinsufficiency of Cyfip1, a candidate risk gene in the 15q11.2(BP1-BP2) deletion, impacts postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis.

Methodology Details:

- Animal Model: Cyfip1tm2a(EUCOMM)Wtsi animals maintained heterozygously on C57/BL6J background, with wild-type littermates as controls.

- Tissue Preparation: Paraformaldehyde fixed brains from 8-12-week-old animals sectioned at 40μm using cryostat.

- Immunohistochemistry: Free-floating sections incubated with primary antibodies (BrdU, Ki67, DCX, NeuN, cleaved-caspase 3) followed by appropriate secondary antibodies.

- Cell Culture: Primary hippocampal progenitors isolated from P7-P8 animals, cultured on poly-L-lysine/laminin with EGF and FGF2.

- Microglial Culture: Primary microglia isolated from P7-P8 whole brain mixed glia via shake-off method.

- Time-lapse Imaging: Primary hippocampal progenitors imaged at 5 DIV for 2 hours with image acquisition every 5 minutes.

- Actin Analysis: Cells stained with Alexafluor 488-conjugated DNAseI and Alexafluor 647-conjugated phalloidin.

- Arp2/3 Inhibition: Cells treated with 50μM CK-548 or 250μM CK-666 in DMSO prior to imaging.

Key Findings: Cyfip1 haploinsufficiency led to increased numbers of adult-born hippocampal neurons due to reduced apoptosis, without altering proliferation [22]. This resulted from a cell autonomous failure of microglia to induce apoptosis through secretion of appropriate factors [22]. Additionally, abnormal migration of adult-born neurons was observed due to altered Arp2/3 mediated actin dynamics [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating ASD Developmental Timeline

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC Differentiation | LDN-193189, SB431542 | Neural induction from iPSCs | Dual SMAD inhibition to direct neural fate |

| Neuronal Markers | Tuj1 (β-III-tubulin), MAP2, NeuN | Identifying neuronal identity | Cytoskeletal and nuclear markers for neurons |

| Synaptic Markers | Synapsin, PSD95, VGLUT1, GAD67 | Assessing synaptic development | Pre- and post-synaptic protein localization |

| Proliferation Assays | EdU, BrdU, Ki67 antibody | Measuring cell division | Nucleotide analogs for DNA labeling, cell cycle marker |

| Apoptosis Assays | Cleaved-caspase 3, TUNEL | Quantifying programmed cell death | Marker of apoptotic activation, DNA fragmentation |

| Cytoskeletal Probes | Phalloidin (F-actin), DNAseI (G-actin) | Visualizing actin dynamics | Selective binding to filamentous/globular actin |

| Arp2/3 Inhibitors | CK-548, CK-666 | Disrupting actin branching | Specific inhibition of Arp2/3 complex formation |

Environmental Influences on Genetic Risk Programs

Maternal Immune Activation and Fetal Brain Development

Environmental challenges during the prenatal period can significantly modulate genetic risk programs, with maternal immune activation (MIA) representing a well-characterized pathway [23]. MIA triggered by infection or inflammation during pregnancy has been associated with developmental difficulties in children, including increased risk of speech, language, and motor delays, behavioral and emotional problems, and altered connectivity in brain regions supporting working memory [23].

The mechanistic pathway involves:

- Cytokine elevation: MIA elevates circulating and central proinflammatory cytokines in animal models, potentially impacting fetal immunity and neurodevelopment [23].

- Placental signaling: The placenta expresses toll-like receptors that can directly recognize microbial products, leading to increased placental inflammation and inflammatory cytokine release that affects fetal brain development [23].

- Specific cytokine effects: IL-6 plays a critical role in promoting MIA-induced ASD-like deficits in inhibition control and social interaction in mice [23]. Blocking placental IL-6 signaling prevents MIA-induced immune activation in the fetal brain and subsequent behavioral abnormalities [23].

Diagram: Maternal Immune Activation Experimental Workflow

Teratogenic Exposures and Gene Expression Modulation

Prenatal exposure to specific teratogens has been associated with increased incidence of ASD, providing insights into critical developmental windows [24]. Valproic acid, ethanol, thalidomide, and misoprostol have all been documented to increase ASD risk, with exposure timing particularly critical during early pregnancy (estimated between the 18th and 42nd day) [24].

These teratogens share common mechanisms of action:

- Gene expression modulation: Each drug can modulate the expression of numerous genes involved in proliferation, apoptosis, neuronal differentiation, migration, synaptogenesis, and synaptic activity [24].

- Early neurodevelopment disruption: These compounds affect development at very early stages, potentially inducing not only autism but also malformations of ears, eyes, and limbs, along with language delay and mental retardation [24].

- Biological process deregulation: Common processes affected include proliferation/apoptosis balance, neuronal differentiation, connectivity, and circulatory system development [24].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Targeting Developmental Windows

The precise temporal mapping of ASD risk gene activation provides critical insights for therapeutic intervention strategies. The recognition that most ASD risk genes express prenatally suggests that optimal intervention timeframes may be earlier than previously recognized [20]. Two key strategic approaches emerge:

- Epoch-specific interventions: Targeting mechanisms specific to each developmental epoch, such as proliferation modulation during Epoch-1 versus synaptic stabilization during Epoch-2.

- Pathway-based approaches: Focusing on downstream convergent pathways rather than individual genetic mutations, given the pleiotropic nature of ASD genes and their convergence on common biological processes.

The recognition that the majority of ASD risk genes are broadly expressed, not limited to the brain, suggests that many ASD individuals may benefit from being treated as having a broader medical disorder rather than exclusively a brain disorder [20]. This has significant implications for both therapeutic development and clinical management approaches.

Biomarker Discovery and Early Identification

Understanding the developmental timeline of genetic risk programs enables a more targeted approach to biomarker discovery. Several promising biomarker candidates have emerged:

- Maternal autoantibodies: Specific maternal autoantibody patterns reactive against fetal brain proteins (MAR ASD) are observed in approximately 20% of ASD cases, with mothers exhibiting these antibodies being 31 times more likely to have a child with ASD [25].

- Immune markers: Altered cytokine and chemokine profiles in mothers during pregnancy and in newborns at birth show associations with subsequent ASD diagnosis [25].

- Redox system markers: Evidence of redox system dysfunction provides potential biomarkers of altered metabolic and signaling pathways in ASD [21].

These biomarkers not only offer potential for early identification but also begin to define biologically distinct subtypes of ASD, which may respond differentially to targeted interventions.

The developmental timeline of genetic risk program activation in ASD reveals a predominantly prenatal disorder with two main epochs of vulnerability: Epoch-1 (trimesters 1-3) involving broadly expressed regulatory genes disrupting proliferation, neurogenesis, migration and cell fate; and Epoch-2 (trimester 3 and early postnatal) involving primarily brain-specific genes disrupting neurite outgrowth, synaptogenesis and cortical wiring [20]. This temporal mapping, framed within the context of biochemical pathway dysregulation, provides a critical framework for understanding ASD pathogenesis and developing targeted interventions.

Future research directions should prioritize the non-invasive study of ASD cell biology, further refinement of developmental timelines for specific genetic risk programs, and the development of epoch-specific therapeutic approaches that account for the temporal dynamics of ASD pathogenesis. The integration of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors across developmental time will be essential for advancing our understanding of ASD and developing effective, biologically-based interventions.

The Gut-Brain Axis and Neuroimmune Dysregulation in ASD Pathophysiology

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a group of complex neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by two primary symptom domains: persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [26]. These core symptoms typically emerge in early childhood and often lead to clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. The diagnostic criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) require that symptoms be present in the early developmental period, though they may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities [26].

The epidemiological landscape of ASD has undergone significant changes over recent decades, with steadily increasing prevalence rates observed worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, the identified prevalence has risen from 1 in 150 children in 2000 to approximately 1 in 31 children (3.2%) as of 2022 surveillance data [27]. This increasing trend reflects both improved awareness and diagnostic practices as well as potential changes in risk factors. ASD is reported to occur across all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, though a striking gender disparity persists with males being diagnosed approximately 3 times more frequently than females [27] [26].

Beyond the core behavioral symptoms, ASD is frequently accompanied by numerous comorbidities and associated features. These include neurological conditions such as epilepsy, sleep disorders, and motor abnormalities; psychiatric comorbidities including anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; and various medical conditions including gastrointestinal disorders, immune dysregulation, and metabolic abnormalities [26] [28]. The substantial clinical heterogeneity of ASD is reflected not only in the variability of core symptom severity but also in the pattern and prevalence of these associated conditions, presenting significant challenges for diagnosis, treatment, and research.

Table 1: Epidemiological Trends in ASD Prevalence Based on CDC ADDM Network Data

| Surveillance Year | Birth Year | Combined Prevalence per 1,000 Children | Approximate Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1992 | 6.7 | 1 in 150 |

| 2006 | 1998 | 9.0 | 1 in 110 |

| 2008 | 2000 | 11.3 | 1 in 88 |

| 2012 | 2004 | 14.5 | 1 in 69 |

| 2016 | 2008 | 18.5 | 1 in 54 |

| 2020 | 2012 | 27.6 | 1 in 36 |

| 2022 | 2014 | 32.2 | 1 in 31 |

The Gut-Brain Axis: Fundamental Mechanisms and Pathways

The microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) represents a complex, bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract with the central nervous system. This system integrates neural, endocrine, and immune signaling pathways to facilitate continuous cross-talk between the brain and the gut microbiota, which comprises the trillions of microorganisms residing in the intestinal tract [29] [30]. In ASD pathophysiology, this axis has emerged as a crucial area of investigation, with mounting evidence suggesting its significant contribution to the disorder's development and manifestation.

The MGBA consists of several integrated components: the gut microbiota with its diverse microbial communities; the intestinal mucosal barrier and epithelium; the enteric nervous system (often described as the "second brain"); the autonomic nervous system, particularly the vagus nerve; and various neuroendocrine and neuroimmune pathways [30]. These elements work in concert to monitor and regulate gastrointestinal function while simultaneously influencing brain development, neural activity, and behavior. In individuals with ASD, multiple aspects of this complex system appear to be dysregulated, potentially contributing to both the core behavioral symptoms and frequent gastrointestinal comorbidities.

The primary communication pathways of the MGBA include:

- Neural pathways: The vagus nerve serves as a direct neural connection between the gut and brain, transmitting sensory information from the periphery to central nervous system nuclei and relaying efferent signals back to the gastrointestinal tract. Studies have demonstrated that children with ASD frequently exhibit parasympathetic dysregulation and reduced vagal tone, which correlates with the severity of core symptoms including social interaction deficits and language impairments [30].