Cross-Species Biological Network Analysis: Methods, Applications, and Challenges in Biomedical Research

Cross-species comparative analysis of biological networks has emerged as a powerful approach for understanding evolutionary conservation, predicting protein function, and translating findings from model organisms to human biology.

Cross-Species Biological Network Analysis: Methods, Applications, and Challenges in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Cross-species comparative analysis of biological networks has emerged as a powerful approach for understanding evolutionary conservation, predicting protein function, and translating findings from model organisms to human biology. This article provides a comprehensive overview of foundational concepts, methodological frameworks, practical applications, and current challenges in comparing biological networks across species. We explore how protein-protein interaction networks, regulatory pathways, and gene co-expression networks can be aligned and compared to uncover conserved functional modules and species-specific adaptations. For researchers and drug development professionals, we review established tools like QIAGEN IPA and CroCo framework, discuss network alignment algorithms including Bayesian methods, and address limitations in data integration and interpretation. This synthesis aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively leverage cross-species network comparisons for drug discovery, biomarker identification, and understanding disease mechanisms.

Biological Networks and Evolutionary Conservation: Foundational Principles

Graph theory provides a powerful, flexible mathematical framework for representing and analyzing complex biological systems. By modeling biological entities as nodes (vertices) and their interactions as edges (connections), researchers can abstract and investigate everything from molecular pathways to ecosystem-level relationships [1] [2]. This approach has become fundamental to systems biology, enabling the study of emergent properties that cannot be understood by examining individual components in isolation [3]. The inherent complexity of biological systems—with their multi-scale organizations and dynamic interactions—makes graph theory particularly valuable for capturing these relationships in a computationally tractable form.

In recent years, biological network analysis has evolved beyond simple graph representations to include more sophisticated models like hypergraphs, which can natively capture multi-way relationships among biological entities [4] [5]. This expansion of modeling techniques has opened new possibilities for understanding complex biological phenomena, from cellular signaling pathways to cross-species comparative analyses. As the field progresses, the choice of an appropriate network model—whether simple graph, directed graph, weighted graph, or hypergraph—has become increasingly important for extracting meaningful biological insights [2] [3].

Graph Models: Fundamental Approaches

Basic Graph Types and Their Biological Applications

Biological networks employ several fundamental graph types, each suited to representing different kinds of biological relationships and interactions [1] [2]:

Undirected graphs represent symmetric relationships where the connection between nodes has no inherent directionality. These are commonly used for protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and gene co-expression networks, where interactions are mutual [1] [2].

Directed graphs (digraphs) incorporate directionality, representing asymmetric relationships where one node influences another. These are essential for modeling regulatory networks, signal transduction pathways, and metabolic pathways where the direction of influence or information flow is critical [1] [6].

Weighted graphs assign numerical values to edges, representing the strength, capacity, or reliability of connections. These are widely used for sequence similarity networks and relationships derived from text mining or co-expression analyses [1] [2].

Bipartite graphs divide nodes into two disjoint sets, with edges only connecting nodes from different sets. These effectively model relationships between different classes of biological entities, such as gene-disease associations or drug-target interactions [2].

Table 1: Graph Types and Their Biological Applications

| Graph Type | Key Characteristics | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Undirected Graph | Symmetric connections without direction | Protein-protein interaction networks, gene co-expression networks |

| Directed Graph | Asymmetric connections with direction | Regulatory networks, metabolic pathways, signal transduction |

| Weighted Graph | Edges with assigned numerical values | Sequence similarity networks, confidence-scored interactions |

| Bipartite Graph | Two node sets with cross-connections | Gene-disease networks, drug-target interactions, enzyme-reaction links |

Experimental Workflow for Graph Construction

The construction of biological networks follows systematic experimental and computational workflows. For protein-protein interaction networks, large-scale experimental techniques like yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) systems, tandem affinity purification (TAP), and mass spectrometry approaches generate initial interaction data [1]. For gene regulatory networks, protein-DNA interaction data from databases such as JASPAR and TRANSFAC provide the foundation for network construction [1].

The resulting networks are typically represented using standardized computational formats that enable analysis and sharing. The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) is an XML-like format capable of representing various biological networks for computational analysis [1]. Alternative formats include the Proteomics Standards Initiative Interaction (PSI-MI) format for molecular interactions, Chemical Markup Language (CML) for chemical entities, and BioPAX for pathway data [1].

Once constructed, these networks can be analyzed using various graph-theoretical metrics that reveal biologically significant patterns and properties. Key analysis metrics include degree distribution (showing the probability of a node having a certain number of connections), graph density (measuring how well-connected the network is), and clustering coefficient (quantifying how well a node's neighbors are connected to each other) [7].

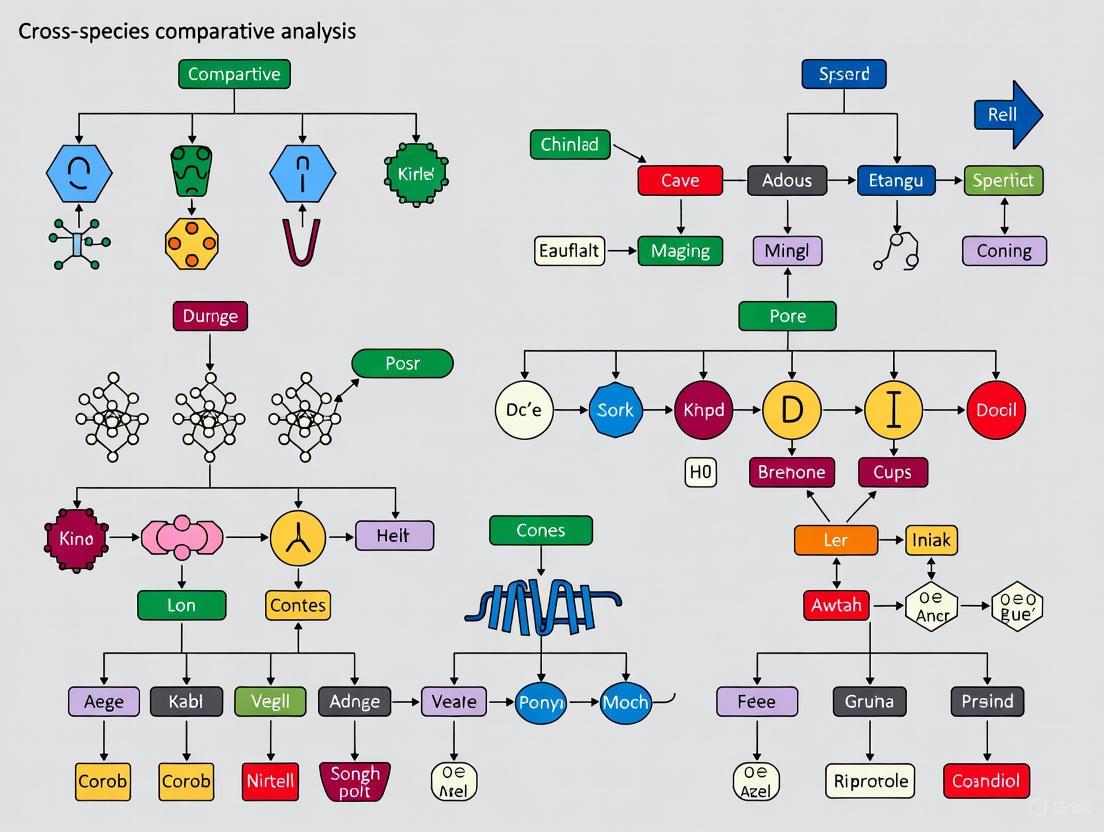

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for biological network construction and analysis

Hypergraph Models: Capturing Complex Multi-way Relationships

Theoretical Foundations of Hypergraphs

Hypergraphs represent a generalization of traditional graph models that can natively capture multi-way relationships among biological entities [4] [5]. While traditional graphs are limited to pairwise connections (edges between two nodes), hypergraphs allow connections (hyperedges) that can link any number of nodes simultaneously. This capability makes them particularly suited for modeling complex biological systems where interactions often involve multiple participants [5].

In mathematical terms, a hypergraph is defined as H = (V, E), where V is a set of vertices and E is a set of hyperedges, with each hyperedge being a subset of V [4]. The connectivity of a hypergraph—whether you can traverse from any node to any other node through a series of connections—is a fundamental property studied in random geometric hypergraph models, with important implications for understanding system robustness and information flow in biological systems [4].

The superiority of hypergraph models emerges from their ability to preserve the inherent multi-way relationship structure present in biological data. When these relationships are forced into pairwise interactions in traditional graph models, significant information is lost, potentially leading to misleading structural conclusions about the biological system being studied [5].

Experimental Evidence: Hypergraph Performance in Identifying Critical Genes

Recent research has demonstrated the practical advantages of hypergraph models for identifying biologically significant elements in complex systems. A 2021 study on host response to viral infection created a novel hypergraph model from transcriptomics data, where hyperedges represented significantly perturbed genes and vertices represented individual biological samples with specific experimental conditions [5].

In this experimental setup, researchers compiled transcriptomic data from cells infected with five different highly pathogenic viruses. They constructed both traditional graph models and hypergraph models from the same dataset, then compared their performance in identifying genes critical to viral response. The hypergraph model represented the data more faithfully by directly capturing which sets of genes were co-perturbed across which experimental conditions, rather than reducing these multi-way relationships to pairwise connections [5].

The results demonstrated that hypergraph betweenness centrality significantly outperformed traditional graph centrality measures for identifying genes important to viral response. Genes ranked highly using hypergraph metrics showed superior enrichment for known immune and infection-related genes compared to those identified through graph-based approaches [5]. This provides compelling evidence that hypergraph models can more effectively capture the true biological significance of elements within complex systems.

Table 2: Hypergraph vs. Graph Performance in Identifying Critical Viral Response Genes

| Metric | Graph Model Performance | Hypergraph Model Performance | Biological Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betweenness Centrality | Moderate identification of critical genes | Superior identification of critical genes | 25/32 genes confirmed as known immune genes |

| Multi-way Relationship Capture | Limited to pairwise connections | Native representation of complex interactions | More faithful representation of co-perturbation patterns |

| Enrichment for Immune Genes | Moderate enrichment | Superior enrichment | Better alignment with established viral response mechanisms |

| Model Fidelity | Information loss from reducing to pairs | Preservation of multi-way relationships | Structural conclusions more biologically plausible |

Comparative Analysis: Graphs vs. Hypergraphs

Structural and Functional Differences

The choice between graph and hypergraph models involves important trade-offs that impact the biological insights that can be derived from network analysis. Traditional graph models excel at representing pairwise relationships and have well-established computational tools for analysis [1] [2]. However, they necessarily simplify multi-way biological relationships into sets of pairwise connections, which can distort the true structure of the system [5].

Hypergraph models preserve the complete multi-way relationship structure but come with increased computational complexity and fewer established analytical tools [4] [5]. The key structural difference lies in how they represent relationships: graphs use edges that connect exactly two vertices, while hypergraphs use hyperedges that can connect any number of vertices [4]. This fundamental distinction makes hypergraphs particularly valuable for modeling biological phenomena like protein complexes, metabolic reactions, and coordinated gene expression patterns where multiple entities interact simultaneously [5].

From a functional perspective, graph models have proven effective for identifying hub proteins in interaction networks and analyzing connectivity patterns in metabolic pathways [1] [7]. Hypergraph models, however, have demonstrated superior performance for tasks like identifying critically important genes based on complex expression patterns across multiple conditions [5]. This suggests that the optimal model choice depends heavily on the specific biological question and the nature of the relationships being studied.

Cross-Species Comparative Analysis Applications

In cross-species comparative analyses of biological networks, both graph and hypergraph approaches offer distinct advantages. Graph-based network alignment algorithms can identify conserved subnetworks across species, revealing evolutionary relationships and potentially inferring ancestral networks [7]. These approaches typically compare topological features, degree distributions, and connectivity patterns to establish similarities between networks from different organisms [7].

Hypergraph models offer promising avenues for cross-species comparison by capturing higher-order organizational principles that may be conserved across evolution. While less established than graph-based approaches for this application, hypergraph methods could potentially identify conserved multi-way interaction patterns that might be missed by pairwise alignment methods [5]. This could be particularly valuable for understanding how complex molecular machines and pathways evolve while maintaining their functional integrity.

Recent methodological advances in comparing directed, weighted graphs using optimal transport distances—including Earth Mover's Distance (Wasserstein Distance) and Gromov-Wasserstein Distance—show promise for enhancing cross-species network comparisons [8]. These approaches can account for both the directionality of interactions and the strength of connections, providing more nuanced comparisons between biological networks from different species [8].

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of graph vs. hypergraph models

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Methodologies for Network Construction and Analysis

The construction of biological networks follows rigorous experimental and computational protocols that vary depending on the network type and data source. For protein-protein interaction networks, high-throughput experimental methods like yeast two-hybrid screening and affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry generate primary interaction data [1]. These experimental results are often supplemented with curated data from specialized databases such as DIP, MINT, BioGRID, and String, which aggregate interaction information from multiple sources [1].

For gene regulatory networks, construction typically begins with protein-DNA interaction data from sources like JASPAR and TRANSFAC, combined with gene expression data that reveals regulatory relationships [1]. The resulting networks are often represented as directed graphs, with edges indicating the direction of regulatory influence [6]. Computational methods for inferring regulatory relationships include correlation analysis, mutual information calculation, and Bayesian network approaches [3].

Hypergraph construction from biological data follows distinct methodologies that preserve multi-way relationships. In the viral response study, researchers created hypergraphs directly from transcriptomic data by thresholding log₂-fold change values, with each gene represented as a hyperedge enclosing those experimental conditions where the gene showed significant perturbation [5]. This approach maintained the inherent multi-way relationships between genes and conditions that would be lost in traditional graph representations.

Analytical Techniques for Network Comparison

Cross-species network comparison employs specialized analytical techniques to identify conserved and divergent features. Network alignment algorithms attempt to find similarities between networks from different organisms, identifying conserved subnetworks that may indicate functional importance or evolutionary relationships [7]. These methods can operate at local levels (identifying small conserved patterns) or global levels (aligning entire networks) [7].

Motif detection algorithms identify small, recurring patterns within biological networks that may perform specific functions [7]. The conservation of network motifs across species can reveal evolutionary constraints on network architecture and identify fundamental functional units within complex biological systems [7].

Recent advances in optimal transport distances for directed, weighted graphs provide new methods for network comparison that account for both directionality and connection strength [8]. The Earth Mover's Distance (Wasserstein Distance) measures the "work" required to transform one network into another, while the Gromov-Wasserstein Distance focuses on comparing overall network structures while preserving relational patterns [8]. These approaches have shown particular promise for analyzing cell-cell communication networks, where directionality of signaling is critical [8].

Key Databases and Software Tools

Successful biological network analysis relies on specialized databases and computational tools that facilitate network construction, analysis, and visualization. The table below summarizes essential resources for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Biological Network Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Interaction Databases | DIP, MINT, BioGRID, String, HPRD | Curated protein-protein interaction data from experimental and computational sources |

| Regulatory Network Resources | JASPAR, TRANSFAC, BCI, Phospho.ELM | Transcription factor binding sites, regulatory interactions, post-translational modifications |

| Metabolic Pathway Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc, BioCyc, metaTIGER | Metabolic pathways, biochemical reactions, enzyme information |

| Data Format Standards | SBML, PSI-MI, BioPAX, CML | Standardized formats for representing biological networks computationally |

| Specialized Analysis Tools | MixNet, DiWANN, Hypergraph centrality metrics | Network connectivity analysis, efficient sequence similarity networks, hypergraph metrics |

Experimental Design Considerations

When designing experiments involving biological network analysis, researchers must consider several key factors that influence model selection and analytical approach. The nature of biological relationships being studied should guide the choice between graph and hypergraph models—pairwise interactions are well-suited to traditional graphs, while multi-way relationships benefit from hypergraph representations [2] [5].

The scale and complexity of the biological system must align with computational resources and analytical goals. Large-scale networks may require sampling approaches or specialized algorithms for efficient analysis [7]. The availability and quality of experimental data significantly impact network reliability, with integration of multiple data sources often improving network accuracy and biological relevance [1] [5].

For cross-species comparisons, researchers should consider evolutionary distance between organisms being compared and select appropriate alignment algorithms based on whether seeking conserved core networks or species-specific adaptations [7]. Validation strategies should include both computational measures (such as enrichment analysis) and experimental verification where possible [5].

Biological networks provide fundamental organizational blueprints that enable the complex functionalities of living organisms. In cross-species comparative analysis, researchers examine these networks across different species to uncover deeply conserved biological modules, identify species-specific adaptations, and translate findings from model organisms to human biology. This systematic comparison reveals that while network architectures can be conserved, their specific components and regulatory fine-tuning often diverge through evolution. The integration of high-throughput data with computational modeling has significantly advanced our ability to map and compare these networks, providing unprecedented insights into the universal and specialized principles of biological organization [9] [10].

This guide objectively compares three fundamental biological networks—Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs), Metabolic Pathways, and Transcriptional Regulatory Networks—by synthesizing experimental data and analytical methodologies. We focus on their defining characteristics, experimental protocols for their determination, and computational frameworks for their cross-species analysis, providing drug development professionals with a structured resource for target identification and validation.

Defining the Network Types

Protein-Protein Interaction Networks (PPIs)

Protein-protein interactions form the physical interactome of the cell, representing transient or stable associations between proteins that govern cellular processes. These interactions are physical contacts of high specificity established between protein molecules, driven by electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic effects [11]. PPIs can be categorized based on several properties:

- Stability: Stable interactions form permanent complexes, such as the hemoglobin tetramer or core RNA polymerase. Transient interactions are temporary, often regulated by conditions like phosphorylation or cellular localization, and are prevalent in signaling cascades [12] [11] [13].

- Obligate vs. Non-Obligate: Obligate interactions are permanent and essential for function, whereas non-obligate interactions are facultative [12].

- Specificity: Homotypic interactions occur between identical or similar protein domains, while heterotypic interactions occur between different domains or molecules [12].

- Composition: Homo-oligomers consist of identical subunits, while hetero-oligomers involve distinct protein subunits [11].

The geometry of PPIs is critical, with binding strength often determined by a subset of residues known as "hot spots." Symmetric PPIs exhibit higher hot spot densities than non-symmetric ones [12].

Metabolic Pathways

Metabolic pathways are linked series of biochemical reactions, catalyzed by enzymes, that convert substrates into products within a cell. These pathways are fundamentally classified by their role in cellular energetics [14]:

- Catabolic Pathways: Break down complex molecules (e.g., carbohydrates, fats) to release energy, which is stored in ATP, GTP, NADH, and FADH2. Examples include glycolysis and the citric acid cycle.

- Anabolic Pathways: Utilize energy to synthesize complex macromolecules (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides, lipids) from simpler precursors. Gluconeogenesis is an example.

- Amphibolic Pathways: Can function both catabolically and anabolically depending on cellular energy conditions. The citric acid cycle is a prime example [14].

These pathways are not isolated; they form an elaborate interconnected network where the flux of metabolites is tightly regulated to maintain homeostasis. The end product of one reaction is the substrate for the next, creating a directed flow of material and energy [14].

Transcriptional Regulatory Networks

Transcriptional regulatory networks represent the directed relationships between transcription factors (TFs) and their target genes. These networks control gene expression, defining cell identity and orchestrating cellular responses. Unlike PPIs, which are physical interactions, regulatory networks represent informational or causal relationships [15] [9].

A key feature of these networks is their condition-specific nature. The active regulatory links and the centrality of genes (a measure of their connectedness) can vary dramatically between different states, such as healthy versus diseased tissues, providing a powerful basis for classifying disease subtypes [9]. These networks are often reconstructed by integrating TF-binding site data (e.g., from TRANSFAC) with gene co-expression networks derived from microarray or RNA-seq studies [9].

Comparative Analysis of Network Properties

The table below provides a systematic, quantitative comparison of the defining features of the three network types, highlighting their distinct roles and properties within the cell.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biological Network Types

| Network Feature | Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks | Metabolic Pathways | Transcriptional Regulatory Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Execution of cellular functions via molecular complexes and signaling | Energy conversion & biomolecule synthesis | Control of gene expression programs |

| Core Components | Proteins | Metabolites, Enzymes | Transcription Factors, Target Genes |

| Interaction Type | Physical, non-covalent (mostly) | Enzyme-Substrate, chemical transformation | Informational, TF-DNA binding |

| Temporal Nature | Transient or Stable | Dynamic, flux-controlled | Condition-specific, dynamic |

| Network Structure | Undirected graph (typically) | Directed, often linear or cyclic | Directed graph |

| Key Databases | BioGRID, STRING | KEGG, MetaCyc | TRANSFAC, RegNetwork |

| Conservation Across Species | Moderate (core complexes) to Low (peripheral) | High (central metabolism) | Variable (core machinery high, targets lower) |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

A diverse toolkit of experimental and computational methods is required to map, quantify, and analyze biological networks. The workflows for studying each network type are distinct, as visualized below.

Protein-Protein Interaction Analysis

Experimental methods for PPIs are designed to capture either stable or transient interactions [12] [13]. The workflow often involves a discovery phase followed by validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols:

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): This is a primary technique for identifying stable interactions in a native cellular context [13].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells using a non-denaturing detergent to preserve protein complexes.

- Antibody Binding: Incubate the lysate with an antibody specific to the "bait" protein.

- Capture: Add Protein A/G-conjugated beads (e.g., magnetic or agarose) to capture the antibody-bait complex.

- Washing: Wash beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution & Analysis: Elute the bound complexes and analyze via SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or mass spectrometry to identify the "prey" partners [12] [13].

Pull-Down Assays: Used when no antibody is available or for recombinant protein studies [13].

- Bait Immobilization: Immobilize a purified, tagged "bait" protein (e.g., GST-, His-, or biotin-tagged) onto a solid support (e.g., glutathione resin for GST).

- Incubation: Incubate the immobilized bait with a cell lysate or purified proteins.

- Washing and Elution: After washing, elute specifically bound "prey" proteins using a competitive analyte (e.g., glutathione for GST-tags) or low-pH buffer [12] [13].

Crosslinking: Stabilizes transient interactions for subsequent analysis.

- Treatment: Treat intact cells or lysates with a homobifunctional, amine-reactive crosslinker.

- Quenching: Quench the crosslinking reaction.

- Analysis: Proceed with cell lysis and analysis by co-IP, pull-down, or direct Western blotting/MS [13].

Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Metabolic studies focus on quantifying the flow of metabolites through pathways, known as flux.

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols:

13C Isotopic Labeling and Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA):

- Tracer Introduction: Feed cells a defined nutrient source where one or more carbon atoms are replaced with the stable isotope 13C (e.g., 13C-glucose).

- Metabolite Extraction: After the isotope reaches isotopic steady state, rapidly extract intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the metabolites using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). The mass distribution of fragments reveals the labeling pattern.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational models to calculate metabolic fluxes that best fit the experimentally measured mass distribution, providing a quantitative map of intracellular reaction rates [14].

Constraint-Based Modeling and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA):

- Network Reconstruction: Build a genome-scale metabolic network from databases like KEGG, specifying all known biochemical reactions and their stoichiometry.

- Define Constraints: Apply constraints, including reaction irreversibility, nutrient uptake rates, and ATP maintenance requirements.

- Optimize Objective: Assume the network reaches a steady state and optimize for a biological objective (e.g., maximize biomass growth or ATP production).

- Predict Fluxes: Solve the linear programming problem to predict the flux through every reaction in the network [10].

Transcriptional Regulatory Network Analysis

Constructing transcriptional networks involves integrating multiple data types to infer functional regulatory relationships.

Detailed Computational Protocol for Condition-Specific Networks:

- Construct a Connectivity Network: Use databases like TRANSFAC to define potential TF-target gene relationships based on transcription factor binding profile predictions (Position Weight Matrices) or literature-curated evidence in the promoter regions of genes [9].

- Build Co-Expression Networks: For each sample (e.g., from microarray or RNA-seq data), construct a network where a TF-gene pair is assigned a co-expression value (e.g., +1 for correlated expression, -1 for anti-correlated) [9].

- Derive Condition-Specific Networks: Intersect the connectivity network with individual co-expression networks. An edge (regulatory link) is considered active in a specific sample only if it exists in the connectivity network and shows significant co-expression in that sample's expression profile [9].

- Classification Based on Network Features:

- Link-Based Classification: Use the activity status of individual TF-gene regulatory links as features to classify samples (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) [9].

- Degree-Based Classification: Use the "centrality" of genes (the in-degree, or number of TFs regulating a gene, and the out-degree, or number of genes a TF regulates) as a feature profile for classification. This can often provide more robust separation than individual links [9].

Successful network biology research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools. The following table catalogs key solutions used in the featured experiments and analyses.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (e.g., Thermo Scientific Pierce) | Immunoprecipitation and co-IP; capture of antibody-protein complexes. | High binding affinity for antibodies; magnetic separation for ease of use and reduced non-specific binding. |

| Glutathione Sepharose Beads | Pull-down assays for GST-tagged fusion proteins. | High affinity for GST tag; suitable for both batch and column purification. |

| Homobifunctional Crosslinkers (e.g., amine-reactive) | Stabilization of transient PPIs for crosslinking analysis. | Covalently links interacting proteins in close proximity; spacer arms of varying lengths. |

| 13C-Labeled Metabolites (e.g., 13C-Glucose) | Tracer substrates for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA). | Chemically defined; high isotopic purity; enables tracking of metabolic fate. |

| TRANSFAC Database | Source of TF-binding site profiles and known regulatory interactions. | Curated data; includes position weight matrices (PWMs); essential for regulatory network reconstruction. |

| KEGG PATHWAY Database | Reference database for metabolic pathway reconstruction and visualization. | Manually drawn pathway maps; links genes, enzymes, and compounds; species-specific data. |

| STRING Database | Resource for known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions. | Integrates data from experiments, databases, and text mining; provides confidence scores. |

| BioGRID Database | Open-access repository of genetic and protein interactions. | Manually curated; extensive coverage for model organisms and humans. |

| RAKEL Algorithm | Multilabel classifier for assigning molecules to multiple pathway types. | Used in classifiers like iMPTCE-Hnetwork; effective for hierarchical classification problems. |

| Mashup Algorithm | Network embedding algorithm for feature extraction from heterogeneous networks. | Generates informative features from complex networks; improves classifier performance. |

The objective comparison of PPIs, metabolic pathways, and regulatory networks reveals a hierarchy of biological organization, from physical interaction and biochemical transformation to informational control. Cross-species analysis demonstrates that metabolic pathways are often highly conserved, while regulatory networks and PPIs exhibit greater evolutionary divergence, reflecting adaptation.

For drug development, this hierarchy offers multiple intervention points. Targeting PPIs allows modulation of specific protein complexes, as seen with Hsp90-Cdc37 or MDM2-p53 inhibitors in cancer [12]. Targeting metabolic pathways is effective in cancers with metabolic dependencies, using inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation or the TCA cycle [14]. The future lies in multi-scale network models that integrate these layers. Classifiers like iMPTCE-Hnetwork, which embed molecules in a heterogeneous network of CCIs, CPIs, and PPIs, showcase the power of this integrated approach for accurate prediction of pathway membership and function [10]. Ultimately, leveraging cross-species conservation principles while accounting for species-specific network adaptations will enhance the predictive power of preclinical models and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies.

The Evolutionary Rationale for Cross-Species Network Comparison

Biological systems, from molecular pathways to neural circuits, are fundamentally structured as complex networks. The comparative analysis of these networks across species is not merely a technical approach but is grounded in a powerful evolutionary rationale. As evolutionary processes act on the components and interactions within these networks, they leave conserved signatures and divergent innovations that can be decoded through systematic comparison [16]. This evolutionary perspective enables researchers to distinguish core biological functions conserved by natural selection from species-specific adaptations, providing a framework for understanding how complex biological systems evolve while maintaining essential functions.

The field has progressed from initial descriptive topological studies to sophisticated models that incorporate biological mechanisms such as gene duplication, neofunctionalization, and developmental system drift [16]. This paradigm shift recognizes that network evolution involves not just changes in connection patterns but also the biological properties and constraints of the underlying components. By placing evolutionary biology at the center of network analysis, researchers can transform static network maps into dynamic models that explain how biological systems have diversified across species and how their functions are maintained despite ongoing genetic changes.

Theoretical Foundations: How Evolution Shapes Biological Networks

Evolutionary Models of Network Architecture

Biological networks evolve through distinct mechanisms that shape their architectural properties. Early research focused heavily on network topology, particularly the discovery of scale-free properties with power-law degree distributions in many biological systems [16]. This topological perspective led to evolutionary models such as preferential attachment, where new nodes connect to well-connected existing nodes, and node duplication with subsequent divergence, where gene duplication provides raw material for network evolution [16]. However, these topology-centric models often failed to capture the biological realities of how networks evolve in living systems.

A more biologically grounded approach incorporates established evolutionary processes including gene deletion, subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization of duplicated genes, and whole-genome duplication events [16]. These processes create characteristic patterns in network structure. For instance, duplicated genes initially share interaction partners but gradually diverge in their connectivity through evolutionary time. Models that incorporate these biological mechanisms can use computational simulation and inference methods to compare model predictions with observed data, fit parameter values, and evaluate alternative evolutionary scenarios [16].

The Dual Dynamics of Nodes and Links

Network evolution operates through two semi-independent dynamics: node dynamics (sequence evolution of network constituents) and link dynamics (evolution of interactions between constituents) [17]. These dynamics evolve at different rates and under different constraints, creating complex evolutionary patterns. The relationship between node homology and link conservation is not straightforward—genes with unrelated sequences may assume similar network positions in different organisms (non-orthologous gene displacement), while genes with high sequence similarity may diverge in their functional interactions [17].

This decoupling of node and link evolution necessitates specialized analytical approaches. Bayesian alignment methods have been developed to jointly model both dynamics, using scoring functions that measure mutual similarities between networks while considering both interaction patterns and sequence similarities between nodes [17]. This approach allows nodes without significant sequence similarity to be aligned if their link patterns are sufficiently similar, and conversely, prevents alignment of nodes with high sequence similarity if their network roles have diverged significantly [17].

Methodological Framework: Approaches for Cross-Species Network Comparison

Network Alignment Techniques

Network alignment establishes mappings between nodes and edges across biological networks from different species, analogous to sequence alignment but operating at the systems level. The fundamental challenge is to identify conserved network modules and divergent connections that reflect functional conservation and evolutionary innovation [17]. Bayesian alignment methods address this by systematically inferring both high-scoring alignments and optimal alignment parameters, balancing the contributions from node similarity (sequence homology) and link similarity (interaction conservation) [17].

Formally, an alignment between two graphs A and B is defined as a mapping π between two subgraphs  ⊂ A and B̂ = π(Â) ⊂ B [17]. For most gene pairs, one-to-one mappings are appropriate, though this simplification neglects multivalued functional relationships induced by gene duplications. The alignment scoring function derives from models of link and node evolution, with the link score for binary networks taking a bilinear form that depends on the evolutionary distance between species [17]. For continuous links, as found in coexpression networks, the joint distribution of link strengths is modeled accounting for evolutionary divergence.

Cross-Species Transcriptional Network Analysis

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) provides a powerful framework for cross-species transcriptional network comparison. This approach constructs correlation networks from gene expression data and identifies modules of highly correlated genes that often correspond to functional units [18]. Cross-species comparison of these modules reveals both conserved and divergent transcriptional programs.

In a landmark study of cyanobacteria responses to metal stress, WGCNA was applied to four species under iron depletion and high copper conditions [18]. The analysis revealed that while 9 genes were commonly regulated across all four species, representing a core metal stress response, the species-specific hub genes showed no overlap, indicating distinct regulatory strategies in each species [18]. This demonstrates how cross-species transcriptional network analysis can identify both universal stress response mechanisms and lineage-specific adaptations that would be invisible in single-species studies.

Cross-Species Connectomics in Neuroscience

In neuroscience, cross-species connectomics compares brain networks across species to understand the evolution of neural circuits supporting cognition and behavior. This approach leverages graph theory metrics to identify topological features conserved across species, from C. elegans to humans, including community structure and small-world properties [19]. Important differences have also been identified, such as scaling principles that account for variations in white matter connectivity across primate species [19].

Network control theory (NCT) and graph neural networks provide additional analytical frameworks for cross-species neural comparison [19]. NCT models how brain structural networks constrain neural dynamics and identifies control points that drive brain state transitions, potentially facilitating translation of therapeutic targets across species. Graph neural networks enable predictions about network behavior and have shown utility for predicting cell types and transcription factor binding sites across species, suggesting applications for translating neural data [19].

Table 1: Cross-Species Network Analysis Methods

| Method | Evolutionary Rationale | Key Applications | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Network Alignment | Models divergent evolution of nodes and links | Protein interaction networks, gene coexpression networks | Paired networks with node homology information |

| WGCNA | Identifies conserved and divergent co-expression modules | Transcriptional response to stress, disease states | Gene expression data across multiple conditions |

| Cross-Species Connectomics | Reveals conserved principles of brain organization | Neural circuit evolution, translational neuroscience | Structural and/or functional brain connectivity data |

| Network Control Theory | Predicts how conserved structure generates function | Translating neuromodulation targets, brain state transitions | Structural connectivity with neural activity data |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Cross-Species Transcriptional Network Analysis

The cross-species analysis of transcriptional networks in response to metal stress in cyanobacteria provides a representative workflow [18]:

Data Compilation: Collect transcriptomic datasets from multiple species under comparable experimental conditions. The cyanobacteria study incorporated 50 samples from 4 species under iron depletion or copper toxicity [18].

Quality Control and Preprocessing: Perform clustering analysis to verify that treatment samples separate from controls, confirming that experimental perturbations cause significant transcriptional changes.

Network Construction: Apply WGCNA separately to each species to identify transcriptional modules—groups of highly correlated genes. The cyanobacteria analysis identified 17-32 distinct modules per species [18].

Module-Phenotype Association: Identify modules significantly correlated with experimental conditions (e.g., metal stress) using correlation coefficients and statistical confidence measures.

Functional Annotation: Perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., KEGG pathways) on phenotype-associated modules to interpret their biological significance.

Cross-Species Comparison: Compare modules across species to identify conserved response networks and species-specific adaptations.

This protocol revealed that iron depletion in marine cyanobacteria downregulates amino acid metabolism and upregulates secondary metabolite production and DNA repair pathways, while copper stress affects ribosome biosynthesis [18].

Protocol: Bayesian Network Alignment

The Bayesian alignment method for cross-species network comparison involves this multi-step process [17]:

Network Representation: Represent each biological network as a graph with nodes (genes/proteins) and edges (interactions). Networks may be binary (interaction present/absent) or weighted (e.g., correlation coefficients).

Similarity Calculation: Compute both node similarities (based on sequence homology) and link similarities (based on interaction conservation).

Scoring Function: Define a scoring function that combines node and link similarities, with relative weights determined systematically through Bayesian parameter inference rather than fixed ad hoc.

Alignment Optimization: Identify high-scoring alignments through efficient heuristics that map network alignment to a generalized quadratic assignment problem, solved by iteration of a linear problem [17].

Significance Assessment: Evaluate the statistical significance of alignments relative to appropriate null models.

Functional Prediction: Use conserved network alignments to predict gene functions and identify functional innovations such as non-orthologous gene displacements.

This approach has been successfully applied to analyze evolution of coexpression networks between humans and mice, revealing significant conservation of gene expression clusters despite substantial sequence divergence [17].

Workflow for Cross-Species Transcriptional Network Analysis

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cross-Species Network Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-species Genomic Data | Provides node homology information and evolutionary context | Orthology mapping, sequence-based node similarity [17] |

| Interaction Datasets | Defines network edges (connections) | Protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions [17] |

| Expression Datasets | Enables construction of co-expression networks | WGCNA module identification, condition-specific responses [18] |

| Pathway Databases | Functional annotation of network modules | KEGG, GO enrichment analysis [18] |

| Cellular Resolution Imaging | Enables construction of neural connectomes | Whole-brain mapping in model organisms [19] |

Computational Tools for Network Analysis and Visualization

Table 3: Computational Tools for Cross-Species Network Analysis

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Alignment | Cross-species network alignment | Joint modeling of node and link evolution [17] |

| WGCNA | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis | Module identification, hub gene detection [18] |

| NetworkX | Network creation, manipulation, and visualization | Graph algorithms, multiple layout options [20] |

| Graph Theory Metrics | Quantitative network characterization | Degree distribution, clustering, path length [19] |

| Network Control Theory | Modeling structure-function relationships | Predicting control points, state transitions [19] |

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting complex network data. When using tools like NetworkX, proper label alignment can be achieved by using consistent layout algorithms (e.g., spring_layout) and passing the same position dictionary to both node-drawing and label-drawing functions [20]. For publication-quality figures, adjusting parameters like node size (scaled by importance), edge width (scaled by weight), and font properties ensures readability and accurate communication of results [20].

Computational Framework for Cross-Species Network Analysis

Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Conservation Patterns

Quantitative Assessment of Network Conservation

Cross-species comparisons consistently reveal varying degrees of conservation across different biological networks and evolutionary distances. In the cyanobacteria metal stress study, cross-species analysis identified 69 shared KEGG pathways responding to iron depletion between two Prochlorococcus species, and 49 shared pathways responding to copper toxicity between two Synechococcus species [18]. However, the hub genes—highly connected central players in the network modules—showed complete divergence between species, indicating that while general functional responses are conserved, the regulatory architecture implementing these responses undergoes substantial rewiring [18].

Studies of protein-protein interaction networks have revealed that interaction interfaces evolve at different rates than the overall protein sequence, creating complex patterns where proteins with high sequence similarity may have divergent interaction partners, while functionally similar proteins with low sequence similarity may occupy equivalent network positions [17]. This phenomenon of non-orthologous gene displacement is particularly common in metabolic networks, where different enzymes may catalyze the same reaction in different species [17].

Developmental System Drift and Network Evolution

The concept of developmental system drift describes how network structures change while ultimate biological functions remain unchanged [16]. This phenomenon has been identified in evolutionary network simulations and analyses across diverse biological contexts. For example, in eye development, deep homology exists at the level of high-level function (photoreception) and key genes like Pax6 across vast evolutionary distances, yet intermediate levels of morphology and gene regulatory networks show substantial divergence [16].

This developmental system drift creates challenges for cross-species comparison but also opportunities to identify core functional units that persist despite architectural changes. Quantitative studies in Caenorhabditis nematodes have revealed cryptic evolution in signaling networks—changes that are only apparent following experimental manipulation despite conserved phenotypic outputs [16]. Such findings highlight that network comparison must extend beyond structural similarity to include functional assessments under perturbation.

Table 4: Evolutionary Patterns in Biological Networks

| Evolutionary Pattern | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conserved Modules | Network substructures preserved across species | Iron stress response in cyanobacteria [18] |

| Hub Divergence | Central nodes show greater evolutionary change | Species-specific hub genes in metal stress response [18] |

| Developmental System Drift | Network structure changes while function is conserved | Signaling networks in Caenorhabditis [16] |

| Non-orthologous Displacement | Different components implement similar functions | Metabolic enzymes across bacterial species [17] |

| Network Rewiring | Changes in interaction patterns between conserved components | Transcription factor-promoter interactions [16] |

The evolutionary rationale for cross-species network comparison continues to develop with emerging technologies and analytical approaches. The integration of population genetics into network evolution models represents a promising frontier, as demographic factors and selection regimes profoundly influence how networks evolve [16]. Similarly, the application of graph neural networks to cross-species prediction tasks may enhance our ability to translate findings from model organisms to humans, particularly in neuroscience where cellular-level insights from animal models must be connected to system-level observations in humans [19].

Advances in single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics are enabling construction of higher-resolution networks with cell-type specificity, opening new opportunities for cross-species comparison at finer biological scales. Meanwhile, the development of more sophisticated evolutionary models that incorporate ecological interactions and multi-species relationships will expand cross-species network analysis beyond pairwise comparisons to ecological community networks. These developments will further establish cross-species network comparison as an essential approach for deciphering the evolutionary design principles of biological systems.

Key Biological Questions Addressable Through Network Alignment

Network alignment (NA) is a powerful computational methodology for comparing biological networks across different species or conditions. By identifying conserved structures, functions, and interactions, NA provides critical insights into evolutionary relationships, shared biological processes, and system-level behaviors, with significant implications for biomedical research areas such as understanding cancer progression and human aging [21] [22] [23].

Core Biological Problems and NA Approaches

Network alignment can be leveraged to address several fundamental biological questions, primarily by transferring functional knowledge across species.

| Key Biological Question | Network Alignment Approach | Biological & Biomedical Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Across-species protein function prediction [21] [24] | Identify a mapping between proteins in two PPI networks (e.g., yeast and human) based on topological relatedness and sequence information. | Enables transfer of functional annotations (e.g., Gene Ontology terms) from well-annotated proteins in one species to poorly characterized proteins in another, filling annotation gaps. |

| Identification of conserved functional modules [23] | Local Network Alignment to find highly conserved, small network regions, or Global Network Alignment to map larger, system-level structures. | Reveals evolutionarily conserved pathways and protein complexes, shedding light on essential cellular machinery and evolutionary constraints. |

| Understanding evolutionary relationships [25] [23] | Bayesian or other alignment methods using a scoring function that integrates network interaction patterns and node sequence similarity. | Uncovers functional relationships between genes that may not be apparent from sequence similarity alone, providing a more nuanced view of molecular evolution. |

Methodological Frameworks for Alignment

Biological network alignment methods can be categorized based on how they process input data, which directly influences their application and outcomes [21] [24].

| Method Type | Core Principle | Typical Data Used | Representative Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Network-Only | Node features calculated using only topological information from within each node's own network. | PPI network topology (e.g., graphlets). | TARA [21] [24] |

| Isolated-within-and-across-network | Topological features and sequence information are processed in isolation and combined afterwards. | PPI topology + protein sequence similarity. | WAVE, SANA [21] |

| Integrated-within-and-across-network | Networks are first integrated into one by adding "anchor" links between highly sequence-similar proteins before feature extraction. | PPI topology + protein sequence similarity. | PrimAlign [21] |

| Data-Driven (Supervised) | Learns the relationship between topological patterns and functional relatedness from training data, rather than assuming topological similarity. | PPI topology + protein functional annotation data. | TARA, TARA++ [21] [24] |

Experimental Performance Comparison

The transition to data-driven methods represents a paradigm shift in NA. Traditional methods assume that topologically similar network nodes are functionally related, but recent evidence shows this assumption often fails [21] [24]. Data-driven methods like TARA and TARA++ use supervised machine learning to learn what topological relatedness patterns correspond to functional relatedness, leading to significant improvements in prediction accuracy.

Experimental data from studies aligning yeast and human protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks demonstrate the performance of different approaches [21] [24].

| Method | Alignment Strategy | Key Input Data | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| TARA [21] [24] | Data-driven (supervised), within-network-only | PPI topology, protein functional annotations | Outperformed WAVE, SANA, and PrimAlign in protein function prediction accuracy. |

| TARA++ [21] [24] | Data-driven (supervised), integrated-within-and-across-network | PPI topology, protein functional annotations, sequence similarity | Achieved higher protein functional prediction accuracy than TARA and other existing methods. |

| WAVE [21] | Unsupervised, within-network-only | PPI topology (graphlet-based) | Lower functional prediction accuracy compared to TARA. |

| SANA [21] | Unsupervised, within-network-only | PPI topology (graphlet-based) | Lower functional prediction accuracy compared to TARA. |

| PrimAlign [21] | Unsupervised, integrated-within-and-across-network | PPI topology, sequence similarity | Outperformed many isolated-within-and-across-network methods but was outperformed by TARA. |

| Bayesian Alignment [25] | Bayesian integration of topology and sequence | Co-expression networks, sequence similarity | Provided network-based predictions of gene function and identified functional relationships not concurring with sequence similarity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Data-Driven Network Alignment (e.g., TARA++)

This protocol outlines the steps for a supervised NA method that integrates both topological and sequence information for across-species protein functional prediction [21] [24].

Input Data Preparation

- Network Data: Obtain PPI networks for the species of interest (e.g., S. cerevisiae and H. sapiens) from databases such as BIOGRID or STRING.

- Functional Annotations: Collect protein functional data, typically Gene Ontology (GO) terms, from the GO Consortium.

- Sequence Information: Gather protein sequence data from resources like UniProt.

Create Training and Testing Data

Feature Extraction

- Topological Features: For each protein in a pair, calculate graphlet-based topological features from its respective PPI network. Graphlets are small, connected non-isomorphic subgraphs that capture the local network structure around a node [21].

- Sequence Feature: Compute a sequence similarity score (e.g., using BLAST) for the protein pair across networks [21] [24].

Model Training

Alignment and Prediction

- Apply the trained model to the testing set of protein pairs. Node pairs predicted to be functionally related are included in the final network alignment.

- This alignment is then used with an established methodology to transfer functional annotations (GO terms) from one species to another [21].

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow of a data-driven network alignment method like TARA++.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Network Alignment |

|---|---|

| PPI Network Data (e.g., from BIOGRID, STRING) | Serves as the fundamental topological structure to be aligned, representing the interactome of an organism [21] [23]. |

| Protein Sequence Databases (e.g., UniProt) | Provides primary sequence data used to compute sequence similarity scores, a key feature for across-network alignment [21] [24]. |

| Functional Annotations (e.g., Gene Ontology) | Provides ground-truth data (GO terms) for training supervised models and for evaluating the functional quality of the resulting alignment [21] [24]. |

| Standardized Gene Nomenclature (e.g., HGNC) | Ensures node name consistency across different network databases, which is critical for accurate matching and integration of data from multiple sources [23]. |

| Graphlet-Based Topological Features | Quantifies the local network neighborhood of a node, providing a powerful descriptor for comparing topological roles across networks [21]. |

| Supervised Classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) | The core engine of data-driven NA; it learns the complex mapping from topological and sequence features to functional relatedness [21] [24]. |

Network Alignment Methodologies and Research Applications

Network alignment provides a powerful framework for comparing biological systems across different species or conditions by identifying similar nodes and connection patterns within their respective networks. In cross-species comparative analysis, this methodology enables researchers to discover evolutionarily conserved functional modules, predict protein functions, and transfer biological knowledge from well-studied organisms to less-characterized species. Similar to how sequence alignment revolutionized genomic comparisons, network alignment offers a systems-level perspective that considers not just individual components but also their complex interaction patterns. The fundamental goal of biological network alignment is to cluster nodes across different networks based on both their biological similarity (e.g., sequence homology) and the topological similarity of their neighboring communities. This dual approach reveals deeper insights into molecular behaviors and evolutionary relationships that would be inaccessible through sequence analysis alone [26].

The applications of network alignment in biological research are manifold. In pharmaceutical development, comparing protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks between humans and model organisms helps validate drug targets and predict potential side effects. In disease research, aligning brain connectomes between healthy individuals and patients can pinpoint altered connectivity patterns associated with neurological disorders. The strength of an aligned interactome lies in both the quality and extent of the available data, though current PPI maps for most species remain incomplete, necessitating computational approaches to expand network coverage [27]. As the field advances, network alignment continues to provide invaluable insights into shared biological processes, evolutionary relationships, and system-level behaviors across species [22].

Classification of Network Alignment Approaches

Network alignment methodologies can be categorized along several dimensions based on their scope, methodology, and mapping objectives. Understanding these classifications is crucial for selecting the appropriate algorithm for specific research applications in cross-species comparative analysis.

Alignment Scope and Methodology

Table 1: Classification of Network Alignment Approaches by Scope and Methodology

| Classification Axis | Category | Key Characteristics | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Scope | Local Network Alignment | Identifies small, conserved subnetworks; Produces potentially inconsistent mappings; Similar to local sequence alignment | Græmlin 2.0 [28] |

| Global Network Alignment | Finds single mapping across entire networks; Reveals evolutionary conservation at systems level | MAGNA++, NETAL, GHOST, GEDEVO, WAVE, Natalie2.0 [29] | |

| Number of Networks | Pairwise Alignment | Compares two networks simultaneously; Computationally challenging but more tractable | IsoRank, FINAL, BigAlign [30] |

| Multiple Alignment | Compares more than two networks simultaneously; Exponential complexity increase | Græmlin 2.0 [28] | |

| Methodological Approach | Spectral Methods | Direct manipulation of adjacency matrices; Matrix-based alignment | REGAL, FINAL, IsoRank, BigAlign [30] |

| Network Representation Learning | Nodes represented as embeddings that capture network structure; Mapping performed in embedding space | PALE, IONE, DeepLink [30] | |

| Probabilistic Approaches | Provides posterior distribution over possible alignments; Model assumptions are explicit and extensible | Method by Lázaro et al. [31] |

Local network alignment aims to identify relatively small similar subnetworks that likely represent conserved functional structures, while global network alignment searches for the optimal superimposition of entire input networks [29] [26]. In practice, local aligners have been widely used for protein interaction networks but face limitations when applied to connectomes, where homology information between nodes (brain regions) is unavailable [29]. Global alignment approaches generally provide more comprehensive insights for evolutionary studies but may overlook small, highly conserved functional units.

The computational complexity of network alignment increases significantly with the number of networks being compared. Pairwise alignment (K=2) remains challenging due to the NP-hard nature of the subgraph isomorphism problem, while multiple network alignment exhibits exponential complexity growth [26]. Recent methodological advances have introduced probabilistic approaches that differ from traditional heuristic methods by providing the complete posterior distribution over possible alignments rather than a single optimal mapping. This transparency allows researchers to understand all model assumptions and extend them by incorporating domain-specific knowledge [31].

Node Mapping Strategies

Table 2: Node Mapping Strategies in Network Alignment

| Mapping Type | Structural Characteristics | Biological Interpretation | Evaluation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-to-One | Maps one node to at most one other node | Appropriate for orthologous proteins with conserved functions | Easier to evaluate using edge correctness and conserved edges |

| One-to-Many | Maps one node to multiple nodes in another network | Accounts for gene duplication events | Better conservation scores but biologically less common |

| Many-to-Many | Maps groups of nodes to other groups | Represents functional complexes/modules; Matches biological reality of protein complexes | Difficult to evaluate topologically; Functionally more meaningful |

The choice of node mapping strategy significantly impacts the biological interpretation of alignment results. One-to-one mapping often yields better edge conservation scores and has been more widely studied, but may not adequately represent biological reality where proteins frequently function in complexes and gene duplication events create paralogous relationships [26]. Many-to-many mappings can align functionally similar complexes or modules between different networks, potentially providing more biologically meaningful results despite being more challenging to evaluate topologically [26].

In cross-species comparisons, many-to-many alignment is particularly valuable as it can identify equivalent functional modules even when the exact topological structures have diverged through evolutionary processes. This approach acknowledges that proteins typically work as complexes or modules represented as communities in biological networks, and that perfect neighborhood topology matches are unlikely between different biological networks due to protein duplication, mutation, and interaction rewiring events throughout evolution [26].

Comparative Analysis of Network Alignment Algorithms

Representative Algorithms and Their Methodologies

Numerous network alignment algorithms have been developed, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations. The performance of these algorithms varies significantly based on network properties, making algorithm selection critical for specific research applications.

Spectral Methods: These approaches directly manipulate adjacency matrices to perform alignment. REGAL (REpresentation learning-based Graph Alignment) utilizes network structure to generate node embeddings and then performs alignment in the embedding space. FINAL employs a unified objective function that combines network topology and node feature information for alignment. IsoRank uses spectral clustering on a matrix that combines sequence similarity and network topology, while BigAlign leverages a probabilistic model based on node degrees and matching neighborhoods [30].

Network Representation Learning Methods: These techniques employ an intermediate step where network nodes are represented as embeddings that capture structural information and potentially node features. PALE (Predicting Adversarial Link Embeddings) learns node embeddings and then maps them across networks. IONE (Input-Output Network Embedding) learns representations that preserve both local and global network structures. DeepLink utilizes deep learning architectures to learn cross-network correspondence functions [30].

Probabilistic Approaches: A more recent development exemplified by the work of Lázaro et al. provides a transparent framework that yields the entire posterior distribution over possible alignments rather than a single mapping. This approach enables correct node matching even in situations where the single most plausible alignment would mismatch them, opening new possibilities for applications where existing methods may be inappropriate [31].

Specialized Biological Aligners: MAGNA++ is a genetic algorithm-based approach that optimizes both edge conservation and node similarity simultaneously. NETAL uses a local optimization approach based on neighboring similarity, while GHOST employs spectral signature representations for robust alignment. GEDEVO formulates alignment as a graph edit distance problem, and WAVE uses a wavelet-based signature for multi-scale alignment [29].

Performance Comparison Across Biological Networks

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Network Alignment Algorithms on Biological Networks

| Algorithm | Alignment Type | Key Methodology | Reported Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAGNA++ | Global | Genetic algorithm optimizing edge conservation and node similarity | Best performer in brain connectome alignment [29] |

| Græmlin 2.0 | Multiple | Automatic parameter learning; Novel scoring function | Higher sensitivity/specificity on PPI networks from IntAct, DIP, SNDB [28] |

| FINAL | Pairwise | Joint matrix factorization combining topology and features | Robust to network noise and sparsity [30] |

| PALE | Pairwise | Network embedding and cross-network mapping | Effective for sparse networks with limited anchor nodes [30] |

| IsoRank | Global | Spectral clustering combining sequence and topology | Good balance between biological and topological alignment [30] |

| Probabilistic (Lázaro et al.) | Multiple | Whole posterior distribution over alignments | Correct node matching in challenging alignment scenarios [31] |

Evaluation studies across different biological networks have revealed distinct performance patterns. In assessments of diffusion MRI-derived brain networks, MAGNA++ emerged as the best global alignment algorithm when comparing six state-of-the-art aligners (MAGNA++, NETAL, GHOST, GEDEVO, WAVE, and Natalie2.0) [29]. For protein-protein interaction networks, Græmlin 2.0 demonstrated higher sensitivity and specificity compared to existing aligners when tested on networks from IntAct, DIP, and the Stanford Network Database [28]. This performance advantage is likely attributable to Græmlin 2.0's automatic parameter learning capability, which adapts its scoring function to any set of networks without requiring manual tuning [28].

The comparative study by Trung et al. revealed that each alignment technique has distinct characteristics, with some achieving high alignment accuracy over sparse networks while others demonstrate robustness to network noise [30]. This underscores the importance of selecting alignment algorithms based on specific network properties and research objectives rather than seeking a universally superior solution.

Scoring Functions and Evaluation Metrics

Biological Evaluation Measures

Evaluating network alignment quality remains challenging due to the absence of a biological gold standard. Consequently, researchers employ multiple complementary approaches to assess alignment quality from different perspectives.

Functional Coherence (FC): Proposed by Singh et al., FC measures the functional consistency of mapped proteins by computing the average pairwise functional similarity of aligned protein pairs. The method involves collecting Gene Ontology terms for each protein, mapping these terms to standardized GO terms (their ancestors within a fixed distance from the root), and computing similarity as the median fractional overlap between corresponding sets of standardized GO terms [26]. The FC value provides a direct measure of whether aligned proteins perform similar biological functions, with higher scores indicating better functional conservation.

Interolog-Based Validation: This approach predicts protein-protein interactions across species based on orthology, under the principle that proteins encoded by orthologous genes maintaining conserved function typically maintain most of their interaction partnerships. The InterologFinder framework assigns an "InteroScore" that accounts for homology, the number of orthologues with evidence of interactions, and the number of unique interaction observations [27]. High-quality predicted interactions validated through co-immunoprecipitation experiments confirm the utility of this scoring approach [27].

Gene Ontology (GO) Similarity: Most biological evaluation measures assess the functional similarity of aligned proteins based on their GO annotations, which provide a hierarchical system for representing gene and gene product attributes across species. While the simplest approach calculates the ratio of common GO terms between proteins, more elaborate methods consider the hierarchical structure of the ontology and information content of specific terms [26].

Topological Evaluation Measures

Topological measures assess how well an alignment preserves the network structure independent of biological considerations. These metrics are particularly valuable when ground truth biological correspondences are unknown or incomplete.

Edge Correctness (EC): This fundamental metric calculates the fraction of edges in one network that are aligned to edges in another network. EC measures how well the connectivity structure is preserved between aligned networks, with higher values indicating better topological conservation [26]. While conceptually straightforward, EC may favor conservative alignments that prioritize highly connected regions over biologically meaningful but less dense correspondences.

Conserved Interaction Metrics: These measures count the absolute number or percentage of protein interactions that are conserved across species following alignment. The approach assumes that evolutionarily conserved interactions are more likely to be functionally important. In cross-species PPI analyses, these metrics have revealed that despite high gene conservation between humans and mice, the actual overlap in known protein interactions remains surprisingly low, highlighting both the incompleteness of current PPI maps and potential evolutionary divergence in interaction networks [27].

Symmetric Substructure Score (S3): This measure evaluates the quality of an alignment by assessing the amount of conserved symmetric substructure between networks. S3 addresses some limitations of edge correctness by considering the alignment quality from both networks' perspectives simultaneously rather than just one.

Combined Scoring Approaches

Modern alignment frameworks often employ integrated scoring systems that combine multiple evaluation dimensions:

PASTA-Score: The Perceptual Assessment System for explainable AI introduces a data-driven metric designed to predict human preferences in explanation quality, though its principles can be extended to network alignment evaluation. This approach aims to automate human-aligned evaluation by training on large-scale human judgment datasets [32].

Græmlin 2.0's Learned Scoring: Unlike heuristic scoring functions that require manual tuning for specific networks, Græmlin 2.0 implements automatic parameter learning that adapts its scoring function to any set of networks based on training data of known alignments. The scoring function can incorporate arbitrary features of multiple network alignments, including protein deletions, duplications, mutations, and interaction losses [28].

Probabilistic Scoring: The probabilistic alignment framework proposed by Lázaro et al. moves beyond single-score metrics by providing complete posterior distributions over possible alignments. This enables more nuanced evaluation that considers uncertainty and alternative biologically plausible alignments that might be overlooked by deterministic scoring approaches [31].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Benchmarking Framework

To ensure fair and reproducible evaluation of network alignment algorithms, researchers have developed standardized benchmarking frameworks. The generic, extensible framework proposed by Trung et al. allows systematic comparison of different alignment techniques using consistent datasets and evaluation metrics [30]. This approach includes:

- Implementation of representative algorithms across different methodological categories (spectral methods and network representation learning techniques)

- A reusable component architecture to reduce development time for new algorithms

- Configurable parameters to simulate different network properties

- Visualization tools to understand algorithm behavior under varying conditions

- Extensive performance analyses across multiple network types and characteristics [30]

This benchmarking methodology enables reliable, reproducible, and extensible comparison of alignment algorithms, addressing the previous challenge of understanding performance implications due to disparate evaluation methodologies across studies.

Network Alignment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for conducting network alignment experiments in cross-species biological research:

Specialized Protocols for Specific Biological Networks

Different biological network types require specialized alignment protocols: