Convergent Mechanisms in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Genetic Heterogeneity to Unified Pathophysiological Pathways

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents extraordinary genetic heterogeneity, with hundreds of risk genes identified.

Convergent Mechanisms in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Genetic Heterogeneity to Unified Pathophysiological Pathways

Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents extraordinary genetic heterogeneity, with hundreds of risk genes identified. This review synthesizes recent evidence demonstrating how this diversity converges onto shared pathophysiological pathways, including synaptic dysfunction, transcriptional regulation, neuronal network imbalance, and neuroimmune interactions. We examine foundational genetic architecture, advanced methodological approaches for uncovering convergence, challenges in modeling this complexity, and comparative validation across disorders. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights promising targets for therapeutic intervention that address core biological mechanisms transcending individual genetic lesions, potentially enabling more effective, personalized treatment strategies for ASD subtypes.

The Genetic Architecture of ASD: From Hundreds of Risk Genes to Core Biological Pathways

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction alongside repetitive and restricted behaviors [1]. With a current prevalence of 1 in 31 children in the United States, ASD presents substantial personal, familial, and societal burdens, with lifetime care costs estimated at USD 2.4 million per individual [2]. The genetic basis of ASD is well-established, with twin studies confirming a heritability component of approximately 80%, higher than any other common condition [2] [3]. However, the rapidly accelerating prevalence suggests interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental factors, creating a paradox that researchers are working to resolve [2]. The spectrum of genetic risk in ASD encompasses three major categories: de novo mutations (DNMs), copy number variations (CNVs), and inherited variants, each contributing differently to disease liability through often convergent biological pathways [4] [5].

Advances in genomic technologies, particularly trio-based whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES), have revolutionized our understanding of ASD genetics by enabling comprehensive detection of these variant classes [2] [5]. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the spectrum of genetic risk in ASD, focusing on the quantitative contributions of different variant types, methodologies for their detection, and the convergent molecular mechanisms they reveal.

Quantitative Contributions of Genetic Variants to ASD Risk

Table 1: Liability and Prevalence of Major Genetic Variant Classes in ASD

| Variant Class | % Liability Explained | % of ASD Probands Harboring | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Variants | 49.4% | N/A | Polygenic; additive small effects [4] |

| De Novo Variants | ~3% | 20-55% [2] | Not present in parents; strong effect sizes [4] |

| De novo CNVs | Included above | 4-7% [4] | Large structural changes; often encompass multiple genes |

| De novo SNVs | Included above | ~7% [4] | Single-base changes; includes LoF and missense |

| Rare Inherited Variants | ~3% | 16-19% (combined) [4] | Transmitted from parents; variable penetrance |

| Rare autosomal LoF | Included above | ~3% [4] | Often show transmission disequilibrium |

| X-linked variants | Included above | ~2% [4] | Primarily affect males; maternal transmission |

Table 2: Recent Findings on De Novo Variant Prevalence in ASD Cohorts

| Study Reference | Cohort Size | DNV Detection Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowers et al., 2025 [2] | 150 trios total | 47-55% | Included silent DNVs as pathogenic; associated with folate metabolism |

| SPARK Consortium, 2022 [5] | 42,607 cases | 60 genes exome-wide significance | Identified 5 new moderate-risk genes (NAV3, ITSN1, MARK2, SCAF1, HNRNPUL2) |

| Troyanskaya et al., 2025 [6] | 5,000+ children | Subtype-dependent | "Broadly Affected" subtype had highest DNV burden; "Mixed ASD" had more inherited variants |

The population attributable risk (PAR) from damaging DNMs is approximately 10%, with known ASD or neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) risk genes explaining about two-thirds of this burden [5]. Recent evidence suggests that silent synonymous DNMs may also contribute to ASD risk, with one study finding that adding silent DNVs as principal diagnostic variants increased subject identification to 55% [2].

De Novo Mutations: Mechanisms and Detection

Biological Origins and Characteristics

De novo mutations (DNMs) are spontaneous genetic changes present in an affected individual but absent from both biological parents' genomes [4]. These mutations arise from several mechanisms, including errors during DNA replication, oxidative damage, or imperfect DNA repair mechanisms. Environmental factors such as insufficient nutrients, toxicant exposures, and disrupted folate metabolism have been proposed as potential contributors to increased DNM rates, potentially explaining the rising prevalence of ASD [2].

DNMs in ASD predominantly occur in LoF-intolerant genes (ExAC pLI ≥ 0.5) within the top 20% of LOEUF (Loss-of-Function Observed/Expected Upper Fraction) scores, indicating strong purifying selection against these variants in the general population [5]. The average DNM rate in whole exome data is approximately 1.2 × 10⁻⁸ per nucleotide per generation, with ASD studies typically observing similar or slightly elevated rates [4].

Experimental Protocols for DNM Detection

Trio Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect peripheral blood or saliva samples from ASD proband and both biological parents [2]

- DNA Extraction: Use standardized kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit) to extract high-molecular-weight DNA [7]

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA and prepare sequencing libraries with platform-specific adapters

- Whole Genome Sequencing: Sequence to minimum 30x coverage on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq

- Variant Calling:

- Align sequences to reference genome (GRCh38)

- Call single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels using tools like GATK

- Perform joint calling across trios to identify de novo events [5]

- Variant Annotation:

- Functional annotation using tools like ANNOVAR or VEP

- Impact prediction using PolyPhen-2, SIFT, CADD, and GERP++ [4]

- Filter against population databases (gnomAD, dbSNP)

- Validation: Confirm putative DNMs using Sanger sequencing or independent sequencing runs [4]

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline:

- Quality Control: FastQC for sequence quality, VerifyBamID for sample authenticity

- Variant Filtering: Remove sequencing artifacts and low-quality variants

- DNM Identification: Compare proband variants to parental sequences, requiring absence in both parents

- Pathogenicity Assessment: Integrate multiple in silico scores using tools like Eigen for meta-scoring [4]

Copy Number Variations: Structural Genetic Variants

Characteristics and Prevalence in ASD

Copy Number Variations (CNVs) are structural genomic variations involving duplications, deletions, inversions, or translocations of DNA segments [7]. These variations contribute significantly to genomic diversity and instability, covering approximately 12-15% of the human genome and encompassing at least 1,000 genes [7]. In ASD, CNVs account for 5-10% of cases, with studies identifying recurrent CNV regions including 1q21.2, 3p26.3, 7q11.1, 15q11.1-q11.2, and 16p11.2 [7].

CNVs contribute to ASD pathogenesis primarily through dosage effects (gene amplification or reduction), gene disruption (breakpoint effects), and position effects on neighboring genes. A comprehensive review identified 1,632 protein-coding genes and long non-coding RNAs within candidate CNVs contributing to ASD, with 552 of these genes showing significant expression in the brain [7].

Experimental Protocols for CNV Detection

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood using standardized kits [7]

- Restriction Digestion: Fragment DNA using restriction enzymes

- Fluorescent Labeling:

- Label test (ASD) samples with Cy5 (red fluorescent dye)

- Label reference (control) samples with Cy3 (green fluorescent dye)

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours followed by 65°C for 10 minutes [7]

- Purification: Remove unincorporated dyes using 30 KDa Amicon filters

- Hybridization: Apply labeled samples to microarray slides containing oligonucleotide probes

- Washing: Remove non-specific binding using wash buffers

- Scanning: Scan slides using microarray scanner with Feature Extraction software

- Data Analysis:

- Convert fluorescence ratios to log2 values

- Identify regions with significant deviation from log2 ratio of 0

- Compare to database of known CNV regions and pathogenicity scores

Bioinformatic Analysis of CNV Data:

- Quality Metrics: Signal-to-noise ratios, background fluorescence levels

- CNV Calling: Circular Binary Segmentation (CBS) or Hidden Markov Model (HMM) approaches

- Annotation: Overlap with gene regions, regulatory elements, and known pathogenic CNVs

- Pathogenicity Prediction: Gene content, constraint metrics (pLI, LOEUF), functional enrichment

Table 3: Most Frequent CNV Regions Identified in Saudi Arabian ASD Cohort

| Genomic Region | Variant Type | Potential Pathogenic Genes | Associated Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1q21.2 | Deletion/duplication | Multiple genes | Developmental delay, intellectual disability |

| 3p26.3 | Deletion | CNTN4, CHL1 | Language impairment, social deficits |

| 7q11.1 | Deletion/duplication | Multiple genes | ASD, speech delays |

| 15q11.1-q11.2 | Duplication | Multiple genes | ASD, epilepsy, cognitive impairment |

| 16p11.2 | Deletion/duplication | Multiple genes | ASD, developmental delay, obesity |

Inherited Rare Variants: Familial Transmission Patterns

Characteristics and Inheritance Models

While DNMs have received significant attention in ASD research, rare inherited variants contribute substantially to disease risk, particularly in multiplex families [5]. These variants include loss-of-function (LoF) alleles, damaging missense variants, and regulatory variants that follow complex inheritance patterns including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked transmission [3] [5].

The latest evidence from the SPARK consortium analysis of 42,607 ASD cases demonstrates that rare inherited LoF variants are enriched in LoF-intolerant genes (ExAC pLI ≥ 0.5), similar to DNMs, but known ASD/NDD genes explain only approximately 20% of the overtransmission signal [5]. This suggests most genes conferring inherited ASD risk remain to be identified.

Experimental Protocols for Inherited Variant Analysis

Transmission Disequilibrium Test (TDT) Protocol:

- Cohort Selection: Identify trios (ASD proband + both parents) or duos (proband + one parent)

- Variant Calling: Perform WES or WGS on all family members

- Variant Filtering:

- Focus on ultra-rare variants (allele frequency < 1 × 10⁻⁵ in population databases)

- Apply high-confidence LoF filters (LOFTEE, pExt) [5]

- Retain variants in constrained genes (ExAC pLI ≥ 0.5 or top 20% LOEUF)

- Transmission Analysis:

- Count transmitted versus non-transmitted alleles from unaffected parents

- For duos, count carrying versus non-carrying parents

- Calculate transmission disequilibrium ratio

- Gene Set Enrichment: Test predefined gene sets for excess transmission

Case-Control Burden Test Protocol:

- Cohort Assembly: Large ASD case cohorts (e.g., SPARK: 35,130 cases) and population controls (e.g., gnomAD: 104,068 subjects) [5]

- Variant Annotation: Uniform variant calling and quality control across cohorts

- Gene-Based Burden Testing:

- Group rare variants by gene

- Compare variant frequency between cases and controls

- Adjust for covariates (ancestry, sequencing platform)

- Meta-Analysis: Combine evidence from multiple studies using fixed or random effects models

Convergent Biological Mechanisms Across Variant Classes

Molecular and Cellular Convergence

Despite the extreme genetic heterogeneity of ASD, evidence points to convergence on specific biological pathways and developmental processes [1] [8]. Functional analyses of ASD-associated genes reveal shared mechanisms at molecular, cellular, circuit, and behavioral levels, with neurogenesis and excitatory-inhibitory neuron development identified as key points of convergence [1].

Transcriptomic studies using postmortem brain tissue demonstrate that ASD risk genes show convergent coexpression patterns in specific brain regions and developmental windows, implicating synaptic pathways and chromatin remodeling processes [8]. This convergence is tissue-specific and correlates with ASD association signals from rare variants, suggesting that disparate genetic lesions disrupt common functional networks.

Developmental and Clinical Subtypes

Recent research has identified clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of ASD that correlate with specific genetic risk profiles [6]. Analysis of over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort revealed four distinct subtypes:

- Social and Behavioral Challenges (37%): Core ASD traits with typical developmental milestones; high rates of comorbid ADHD, anxiety, depression

- Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%): Developmental delays but fewer psychiatric comorbidities; higher burden of rare inherited variants

- Moderate Challenges (34%): Milder ASD symptoms; fewer co-occurring conditions

- Broadly Affected (10%): Severe, wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays and psychiatric conditions; highest burden of damaging DNMs [6]

These subtypes demonstrate different developmental trajectories and genetic architectures, with the "Broadly Affected" group showing the highest proportion of damaging DNMs while the "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay" group carries more rare inherited genetic variants [6].

Additionally, studies have revealed that age at diagnosis has genetic correlates, with earlier- and later-diagnosed autism showing different polygenic architectures [9]. Two modestly genetically correlated (rg = 0.38) autism polygenic factors have been identified: one associated with earlier diagnosis and lower social/communication abilities in childhood, and another associated with later diagnosis and increased socioemotional difficulties in adolescence [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ASD Genetics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore | DNA sequencing for variant discovery | WGS preferred over WES for comprehensive variant detection [2] |

| Variant Callers | GATK, DeepVariant, FreeBayes | Identify genetic variants from sequencing data | Joint calling across trios improves DNM detection [5] |

| Pathogenicity Predictors | PolyPhen-2, SIFT, CADD, REVEL, Eigen | Predict functional impact of genetic variants | Combination of scores outperforms individual tools [4] |

| Constraint Metrics | pLI, LOEUF (gnomAD) | Quantify gene intolerance to functional variation | Essential for prioritizing candidate genes [5] |

| CNV Detection Platforms | aCGH (Agilent), SNP arrays | Identify structural variants | aCGH provides higher resolution for rare CNVs [7] |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR/Cas9, iPSC-derived neurons | Experimental validation of candidate genes | Coexpression patterns correlate with CRISPR perturbations [8] |

| Pathway Analysis | GO, KEGG, Reactome, GWAS catalog | Biological interpretation of gene sets | Reveals convergent biological pathways [1] [8] |

The spectrum of genetic risk in ASD encompasses de novo mutations, copy number variations, and inherited variants that converge on key neurodevelopmental processes. Recent advances have illuminated the quantitative contributions of these variant classes, with DNMs explaining approximately 3% of liability but detectable in 20-55% of ASD cases depending on methodology and variant classification [2] [4]. The integration of massive datasets, such as the SPARK consortium's analysis of 42,607 cases [5], has enabled identification of new moderate-risk genes and refined our understanding of genotype-phenotype correlations.

Future research directions include:

- Expanded sample sizes to identify additional moderate-risk genes through improved statistical power

- Functional characterization of candidate genes using CRISPR-based screens and model systems

- Integration of multi-omic data (genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic) to map regulatory networks

- Longitudinal studies correlating genetic profiles with developmental trajectories and treatment responses

- Elucidation of environmental factors that influence mutation rates or modify genetic effects

The recognition of biologically distinct ASD subtypes [6] and genetically correlated factors associated with age at diagnosis [9] provides a foundation for precision medicine approaches in ASD. This emerging framework promises to transform both clinical management and therapeutic development for this heterogeneous disorder.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition with a heterogeneous genetic architecture. Recent large-scale genomic studies have identified hundreds of susceptibility genes, revealing that a significant proportion of high-confidence ASD genes encode transcription regulators and chromatin modifiers. These findings support a convergent disease mechanism hypothesis, wherein genetically diverse mutations disrupt common biological pathways during critical periods of brain development. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence linking transcriptional and chromatin regulatory machinery to ASD pathogenesis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with technical insights into these convergent molecular pathways, experimental approaches for their investigation, and promising therapeutic targets emerging from this mechanistic understanding.

The genetic landscape of ASD encompasses hundreds of genes identified through genome-wide association studies, whole exome sequencing, and copy number variant analyses [10] [11]. Despite this heterogeneity, systems biology approaches have revealed that these genetically diverse risk factors converge on limited biological processes, particularly transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling [12] [13]. These findings suggest that disruption of fundamental gene regulatory mechanisms represents a common pathophysiological pathway in ASD.

Functional genomic analyses demonstrate that ASD risk genes are not randomly distributed across cellular processes but cluster tightly in co-expression networks representing specific developmental trajectories and biological functions [12]. This convergence is particularly evident during human cortical development, where ASD genes coalesce in modules enriched for transcriptional regulation and synaptic development [12]. The enrichment of chromatin modifiers in ASD risk genes provides compelling evidence for epigenetic dysregulation as a core disease mechanism, positioning these factors at the interface between genetic susceptibility and environmental influences [14] [15].

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Gene Families

Chromatin Modifying Enzymes in Neurodevelopment

Chromatin modifiers regulate gene expression by altering chromatin structure through post-translational modifications of histones or DNA, creating an epigenetic landscape that guides brain development [13]. These enzymes can be categorized by their functional activities:

- Writers: Transfer chemical groups to histone proteins (e.g., histone methyltransferases like EZH2, ASH1L, NSD1)

- Erasers: Remove these modifications (e.g., histone demethylases)

- Readers: Interpret modification patterns (e.g., MeCP2 which binds methylated DNA)

- Chromatin Remodelers: Utilize ATP to reposition nucleosomes (e.g., BAF complex components) [13]

These chromatin regulators play several critical roles in neurodevelopment including cell fate determination, neurogenesis, neuronal plasticity, and response to environmental cues [13]. Their dosage sensitivity makes them particularly vulnerable to heterozygous mutations that cause widespread transcriptional dysregulation.

Table 1: Major Chromatin Modifier Gene Families Implicated in ASD

| Gene Family | Representative Genes | Molecular Function | Neurodevelopmental Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Methyltransferases | EZH2, ASH1L, NSD1 | Catalyze histone methylation | Regulate neuronal differentiation and cortical layer formation |

| Methyl-CpG-Binding Proteins | MeCP2 | Interpret DNA methylation patterns | Synaptic development and maturation |

| BAF Complex Components | ARID1B, SMARCA4, SMARCC2 | ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling | Neural progenitor proliferation and differentiation |

| Histone Demethylases | KDM5 family | Remove histone methylation | Fine-tune gene expression during critical periods |

Transcriptional Regulators in ASD

Transcriptional regulators implicated in ASD include sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors and co-factors that assemble into regulatory complexes. These factors control the spatial and temporal expression of gene networks essential for brain development including:

- Neural specification genes that establish regional identities

- Synaptic genes that control circuit formation and function

- Metabolic genes that support neuronal maturation

Functional genomic evidence demonstrates that ASD risk genes encoding transcriptional regulators are enriched in specific co-expression modules during human cortical development, with distinct temporal expression patterns that correspond to critical neurodevelopmental windows [12]. For example, the M2 and M3 modules show enrichment for transcriptional regulators and are anti-correlated with synaptic modules, suggesting these factors orchestrate early developmental processes that precede synaptic maturation [12].

Bioinformatic analyses suggest that ASD-related transcriptional regulators are frequently co-regulated by common transcription factors and are targets of FMRP (Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein), indicating potential mechanisms for coordinating their expression [12]. This convergence of transcriptional regulation and FMRP targets provides a molecular bridge between syndromic and idiopathic forms of ASD.

Quantitative Genetic Evidence

Recent large-scale sequencing studies have provided compelling statistical evidence for the enrichment of chromatin modifiers and transcriptional regulators among high-confidence ASD genes. Integrated analyses of rare sequence and copy number variants demonstrate these functional categories are significantly mutated in ASD cohorts.

Table 2: Statistical Enrichment of Regulatory Genes in ASD Genomic Studies

| Study Cohort | Regulatory Gene Category | Statistical Enrichment | Key Genes Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| 116 ASD Families [10] | Chromatin Modifiers | 37 rare de novo SNVs, significant burden | BRSK2, multiple chromatin genes |

| SPARK Cohort [16] | Transcriptional Regulators | Class-specific enrichment patterns | MEF2 family, SATB2 |

| BrainSpan Network Analysis [12] | Co-expression Modules | p = 0.0024, OR = 2.9 for M16 module | BAF complex components, MEF2C |

| Functional Genomic Integration [12] | FMRP Targets | Significant co-regulation | Multiple transcriptional regulators |

The convergence of genetic evidence highlights several key mechanistic themes:

- Developmental Timing: Genes affecting early transcriptional regulation are distinct from those influencing later synaptic development [12]

- Cortical Layer Specificity: ASD genes show enrichment in superficial cortical layers and glutamatergic projection neurons [12]

- Phenotypic Specificity: Distinct patterns of ASD and intellectual disability risk genes suggest different biological frameworks [12]

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genomic and Transcriptomic Technologies

Advanced genomic technologies have been instrumental in identifying and validating transcription regulators and chromatin modifiers in ASD:

Whole Genome/Exome Sequencing (WGS/WES)

- Purpose: Identify rare coding and non-coding variants in ASD families

- Methodology: High-throughput sequencing of protein-coding regions (WES) or entire genome (WGS) followed by variant calling and annotation

- Variant Interpretation: Follows ACMG guidelines with functional prediction using LOEUF (Loss-of-Function Observed/Expected Upper Bound Fraction) for PTVs and MPC (Missense Badness) for missense variants [10]

Copy Number Variant (CNV) Analysis

- Platforms: SNP-array, WGS-based structural variant calling

- Analysis: Identify rare deletions/duplications disrupting regulatory genes

- Validation: Orthogonal methods (qPCR, MLPA) to confirm potentially damaging CNVs (pdCNVs) [10]

Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS)

- Purpose: Identify DNA methylation patterns associated with ASD

- Methodology: Array-based (Infinium EPIC) or sequencing-based (WGBS) methylation profiling

- Analysis: Identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and variably methylated regions (VMRs) [15]

Systems Biology and Network Analyses

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

- Purpose: Identify modules of co-expressed genes from transcriptomic data

- Methodology: Construct correlation networks from RNA-seq data, identify modules of highly interconnected genes, calculate module eigengenes

- Application: Map ASD risk genes to developmental co-expression networks from human cortical development [12]

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

- Data Sources: InWeb, BioGRID databases (>250,000 interactions)

- Methodology: Test enrichment of physical interactions within gene sets using hypergeometric tests

- Application: Validate shared function among ASD risk genes at protein level [12]

Integration of Functional Genomic Data

- Data Types: Chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq), histone modifications (ChIP-seq), transcription factor binding

- Methodology: Identify enrichment of ASD genes in specific chromatin states or regulatory elements

- Tools: GREGOR, GARFIELD for functional annotation of genetic variants [15]

Pathway Visualization: Transcriptional and Chromatin Regulation in ASD

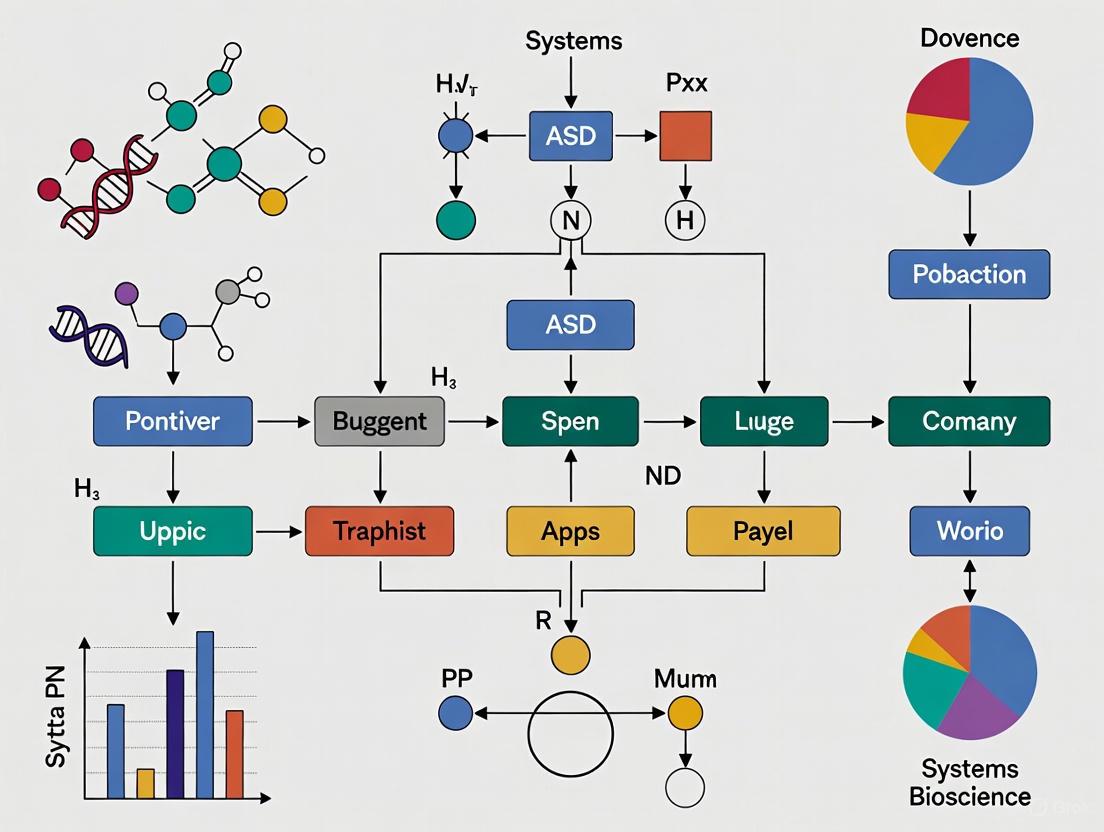

The following diagram illustrates the convergent molecular pathways involving chromatin modifiers and transcriptional regulators in ASD pathogenesis:

ASD Regulatory Pathway: This diagram illustrates how genetic and environmental risk factors converge on chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation pathways, ultimately leading to altered neurodevelopment and core ASD phenotypes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Transcriptional and Chromatin Mechanisms in ASD

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Chromatin Profiling | Anti-H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K27me3, MeCP2 | ChIP-seq for histone modifications and protein-DNA interactions | Validate species cross-reactivity; optimize fixation conditions |

| CRISPR Tools | Cas9 nucleases, base editors, gRNA libraries | Functional validation of ASD variants in model systems | Design multiple gRNAs per target; include proper controls |

| Cell Culture Models | iPSCs from ASD patients, cerebral organoids | Study neurodevelopmental processes in human context | Monitor karyotype stability; include isogenic controls |

| Transcriptomic Profiling | RNA-seq kits, single-cell RNA-seq platforms | Gene expression analysis in development and disease | Consider ribosomal RNA depletion for neural tissues |

| Epigenetic Editing | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1, dCas9-p300 | Targeted manipulation of epigenetic states | Combine with transcriptional readouts for validation |

| Protein Interaction Tools | Co-IP kits, BioID proximity labeling | Characterize regulatory complexes | Include appropriate negative controls |

| Bioinformatic Resources | BrainSpan Atlas, SFARI Gene database, PsychENCODE | Access to human brain development data | Account for batch effects in multi-dataset analyses |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The convergence of ASD genetics on transcriptional and chromatin regulatory pathways reveals promising therapeutic targets. Several strategic approaches are emerging:

Small Molecule Modulators

- Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors already in clinical trials for other neurological disorders

- Bromodomain inhibitors that target histone code readers

- EZH2-specific inhibitors being developed for cancer applications

Precision Medicine Approaches

- Patient stratification based on specific genetic lesions in chromatin pathways

- Biomarker development using epigenomic signatures from accessible tissues [15]

- Targeting compensatory mechanisms in haploinsufficient states

Challenges and Considerations

- Developmental timing of interventions is critical for efficacy

- Cell-type specificity of chromatin regulators complicates therapeutic targeting

- Pleiotropic effects of epigenetic regulators necessitate careful safety profiling

Future research directions should prioritize single-cell multi-omic technologies to resolve cellular heterogeneity, longitudinal studies to understand developmental trajectories, and advanced delivery systems for CNS-targeted therapies. The continued integration of genetic findings with functional genomics will be essential for translating mechanistic insights into targeted interventions for ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [17]. While historically studied from discrete disciplinary perspectives, emerging research reveals convergent biological pathways that unite seemingly disparate mechanistic domains. The intricate interplay between synaptic function, neurodevelopment, and chromatin remodeling represents a paradigm shift in understanding ASD pathophysiology, moving beyond a gene-centric view toward an integrated network model of disease mechanisms [18] [19]. This convergence provides a explanatory framework for ASD's profound heterogeneity while revealing unexpected commonalities at the molecular and cellular levels that transcend genetic diversity.

Advances in genomic technologies and single-cell analytics have illuminated how these convergent pathways operate across different scales of biological organization, from chromatin structure to neural circuits. The PsychENCODE Consortium and other large-scale initiatives have begun mapping the complex relationship between genetic risk and molecular mechanisms in the brain, revealing that diverse genetic alterations frequently funnel into shared biological processes [20]. This whitepaper examines the evidence for this convergence, detailing the molecular players, experimental approaches, and therapeutic implications for researchers and drug development professionals working at the frontier of ASD science.

Molecular Mechanisms of Convergence

Chromatin Remodeling as an Organizing Principle

Chromatin remodeling has emerged as a central node in ASD pathophysiology, with genetic studies consistently implicating genes encoding chromatin modifiers and remodelers among the highest-confidence ASD risk genes [19] [21]. These include ADNP, POGZ, CHD2, CHD8, ASH1L, KMT5B, and KDM6B, which function as epigenetic regulators of gene expression through modification of histone proteins and nucleosome positioning [21]. Rather than operating in isolation, these chromatin regulators establish a molecular framework that guides neurodevelopment and shapes synaptic function.

Recent evidence suggests that chromatin remodeling defects in ASD converge on specific molecular processes. Deficiency of the H3 histone methyltransferase ASH1L leads to synaptic gene dysregulation and excitation/inhibition (E/I) imbalance, while deficiency of KMT5B, a H4 histone methyltransferase, alters DNA repair pathways and activates genes involved in cellular stress [21]. Similarly, deficiency of chromatin regulators ADNP or POGZ prompts immune gene expression, microglia activation, and synaptic defects [21]. These findings position chromatin remodeling as a master regulator that coordinates multiple downstream processes relevant to ASD pathophysiology.

Structural variants (SVs) in non-coding genomic regions further highlight the importance of chromatin organization in ASD. A recent study found ASD-associated SVs significantly enriched in constitutive heterochromatin and in binding sites for transcription factors SATB1, SRSF9, and NUP98-HOXA9 that regulate heterochromatin formation [19]. This suggests that dysregulation of processes maintaining heterochromatin may represent a core mechanism in ASD, potentially explaining the observed high rates of de novo mutations due to loss of protective heterochromatin [19].

Synaptic dysfunction represents a well-replicated convergent pathway in ASD, with evidence from genetics, neurophysiology, and model systems supporting alterations in synaptic development, plasticity, and transmission [18] [22]. Transcriptomic studies of postmortem ASD brains reveal consistent disruption of genes encoding synaptic proteins, particularly those involved in presynaptic function, postsynaptic density, and glutamate signaling [18] [20].

A hallmark concept in ASD pathophysiology is the excitation-inhibition (E/I) imbalance, proposed to result from disruptions in the equilibrium between glutamatergic (excitatory) and GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling [18] [22]. Evidence from multiple lines of research supports this model, including altered levels of GABA and glutamate receptors, impaired differentiation and migration of GABAergic neurons, and changes in the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory synaptic inputs [22]. Genetic studies have identified mutations in genes involved in both glutamatergic and GABAergic signaling, while neuroimaging studies using magnetic resonance spectroscopy have documented alterations in glutamate and GABA levels in individuals with ASD [22].

The relationship between chromatin remodeling and synaptic dysfunction is particularly intriguing. For example, deficiency of the chromatin regulator ADNP results in abnormal synaptic plasticity, dendritic spine morphology, and altered expression of synaptic genes such as activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc) [21]. Similarly, dysfunction of CHD8, one of the most frequently mutated high-confidence ASD risk genes, leads to transcriptional dysregulation of synaptogenesis genes and altered synaptic function [21]. These findings illustrate the mechanistic connection between upstream chromatin regulation and downstream synaptic phenotypes.

Neurodevelopmental Trajectories and Cortical Organization

Convergent evidence from neuroimaging and postmortem studies indicates that ASD involves altered trajectories of brain development, beginning in early prenatal stages and evolving across the lifespan [18] [23]. Structural MRI studies have documented early brain overgrowth in the first years of life, followed by a slowdown in childhood and, in some cases, a decline during adolescence and adulthood [23]. This abnormal growth pattern is thought to reflect underlying disturbances in fundamental neurodevelopmental processes, including neuronal proliferation, migration, and circuit formation.

Postmortem studies have revealed patches of cortical disorganization in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DL-PFC) of children with ASD, characterized by disrupted lamination and aberrant gene expression of layer-specific markers such as CALB1, RORB, and PCP4 [23]. These patches exhibit a significantly reduced glia-to-neuron ratio (GNR) compared to unaffected regions and neurotypical brains, suggesting either a relative reduction in glial cells or an increased number of neurons [23]. These findings point to early developmental disruptions in cortical wiring that may underlie the cognitive and behavioral features of ASD.

Single-cell genomic studies have further refined our understanding of cell-type-specific vulnerabilities in ASD. A groundbreaking UCLA Health study analyzing over 800,000 nuclei from postmortem brain tissue identified the major cortical cell types affected in ASD, including both neurons and glial cells [20]. The most profound changes were observed in callosal projection neurons that connect the two hemispheres and somatostatin interneurons important for maturation and refinement of brain circuits [20]. This high-resolution cellular mapping provides unprecedented insight into the neural populations most vulnerable in ASD.

Table 1: Key Chromatin Regulators Implicated in ASD Pathophysiology

| Gene/Protein | Epigenetic Function | Convergent Consequences | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASH1L | H3 histone methyltransferase | Synaptic gene dysregulation, E/I imbalance | [21] |

| KMT5B | H4 histone methyltransferase | Altered DNA repair, cellular stress response | [21] |

| ADNP | Chromatin remodeling complex | Immune activation, microglia changes, synaptic defects | [21] |

| POGZ | Heterochromatin organization | DNA repair dysregulation, synaptic defects | [21] |

| CHD8 | Chromatin remodeling ATPase | Wnt signaling disruption, neuronal proliferation defects | [21] |

Quantitative Evidence for Convergent Pathways

Large-scale genomic and transcriptomic studies have provided quantitative evidence supporting the convergence of synaptic, neurodevelopmental, and chromatin remodeling pathways in ASD. Integrative analyses of multiple data types reveal consistent molecular signatures despite the genetic heterogeneity of ASD.

PsychENCODE consortium studies have identified specific transcription factor networks that drive molecular changes observed in ASD brains, with these regulatory drivers enriched in known high-confidence ASD risk genes [20]. These networks exert large effects on differential gene expression across specific cell subtypes, providing a mechanistic link between genetic risk and observed brain changes [20].

Analyses of structural variants (SVs) in ASD have revealed their enrichment in heterochromatin regions of the genome, which are paradoxically also enriched for developmental genes [19]. This intersection suggests a model wherein heterochromatin dysregulation produces SVs in genes critical to brain development, thereby linking chromatin organization with neurodevelopmental processes [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence for Pathway Convergence in ASD

| Data Type | Key Findings | Implications for Convergence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell genomics | 800,000 nuclei analyzed; specific neuronal populations affected (callosal projection neurons, somatostatin interneurons) | Cell-type-specific vulnerability links genetic risk to neural circuits | [20] |

| Structural variants | ASD-SVs enriched in heterochromatin (p<0.001); overlap with developmental genes | Connects chromatin structure with neurodevelopmental processes | [19] |

| Transcriptomics | Convergent gene expression modules despite genetic heterogeneity; synaptic and immune pathways co-disrupted | Diverse genetic risks funnel into shared molecular pathways | [18] [20] |

| Histone modifications | Specific chromatin regulators (ASH1L, KMT5B) account for ~5-10% of ASD cases individually | Epigenetic mechanisms as central coordinators of pathophysiology | [21] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Single-Cell Genomics and Transcriptomics

The advent of single-cell assays has revolutionized our ability to profile gene expression and chromatin accessibility at unprecedented resolution, enabling researchers to navigate the brain's complex network of different cell types [20]. The standard workflow involves:

Nuclei Isolation: Post-mortem brain tissue is dissociated to isolate intact nuclei, typically using density gradient centrifugation or fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) to preserve RNA integrity.

Single-Cell Partitioning: Nuclei are partitioned into nanoliter-scale droplets using microfluidic devices (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium platform) where each nucleus is uniquely barcoded.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: mRNA from individual nuclei is reverse-transcribed, amplified, and prepared for sequencing using specialized protocols that maintain cell-of-origin information.

Bioinformatic Analysis: Computational pipelines (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy) are used for quality control, normalization, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and differential expression analysis to identify cell-type-specific signatures.

This approach was used in the landmark UCLA Health study that analyzed over 800,000 nuclei from 66 individuals, identifying specific cortical cell types and transcriptional networks affected in ASD [20].

Structural Variant Detection and Analysis

Advanced methods for detecting and characterizing structural variants (SVs) have revealed their importance in ASD pathophysiology. A novel approach leveraging Non-Mendelian Inheritance (NMI) patterns from SNP genotyping arrays has proven particularly powerful:

Family Trio Design: Analysis of SNP microarray data from both parents and affected offspring (family trios) to identify loci displaying NMI patterns.

SV Calling: NMI patterns are interpreted as potential SVs (deletions, duplications) rather than technical artifacts, using specialized algorithms.

Population Validation: Candidate SVs are validated across independent ASD cohorts (e.g., MIAMI and AGPC datasets) to establish association with ASD.

Multi-omic Integration: SVs are intersected with diverse genomic data layers (chromatin states, TF binding, eQTLs) to understand functional impact.

This methodology identified 2,468 high-confidence ASD-associated SVs enriched in heterochromatin and developmental genes [19].

Functional Validation in Model Systems

Animal and cellular models remain essential for validating the functional consequences of genetic variants and testing therapeutic interventions. Key approaches include:

Genetic Engineering: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated introduction of ASD-associated mutations into animal models (typically mice) or human stem cell-derived neuronal cultures.

Circuit Mapping: Advanced neuroanatomical techniques (tracing, clearing/imaging) and electrophysiological recordings to assess neural connectivity and synaptic function.

Behavioral Phenotyping: Comprehensive behavioral batteries assessing social interaction, repetitive behaviors, learning/memory, and anxiety-related behaviors.

Molecular Profiling: Transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic analyses of model systems to identify downstream consequences of genetic perturbations.

These approaches have demonstrated that ASD-associated mutations in chromatin regulators like CHD8 and ADNP produce measurable alterations in synaptic function, brain connectivity, and behavior [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Convergent Pathways in ASD

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq Platforms | 10X Genomics Chromium, SMART-seq2 | Cell-type-specific transcriptomic profiling in post-mortem brain | [20] |

| Epigenetic Profiling Tools | CUT&RUN, ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq | Mapping chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, TF binding | [19] [21] |

| ASD Mouse Models | Chd8+/-, Adnp+/-, Ash1l conditional KO | Functional validation of ASD gene candidates | [21] |

| Neuronal Differentiation Kits | STEMdiff Cerebral Organoid Kit, Neurogenesis Kits | Modeling human neurodevelopment in vitro | [20] |

| Synaptic Function Assays | Microelectrode arrays (MEAs), patch-clamp systems | Functional assessment of E/I balance and network activity | [18] [22] |

| Calcium Imaging Tools | GCaMP sensors, Fluo-4 | Live monitoring of neuronal activity and calcium signaling | [22] |

Pathway Visualization and Molecular Relationships

The convergent pathways linking chromatin remodeling, neurodevelopment, and synaptic function can be visualized as an integrated network of molecular interactions:

The convergence of synaptic, neurodevelopmental, and chromatin remodeling pathways in ASD represents a fundamental advance in our understanding of this complex disorder. Rather than operating in isolation, these processes form an integrated network wherein perturbations at one level propagate through the system, ultimately manifesting as the diverse behavioral phenotypes that define ASD. This integrative framework helps explain both the heterogeneity of ASD (arising from different nodes of disruption within the network) and the shared features (resulting from convergent downstream effects).

For researchers and drug development professionals, this convergent pathway model offers several important implications. First, therapeutic strategies may need to target critical convergence points rather than individual genetic defects, potentially benefiting broader patient populations. Second, biomarker development should consider molecular signatures that reflect the integrated activity of these pathways rather than single genetic or biochemical measures. Finally, preclinical models must be evaluated for their ability to recapitulate these convergent phenomena rather than isolated aspects of ASD pathophysiology.

Future research should prioritize multi-omic integration across larger cohorts with detailed clinical phenotyping, advanced circuit manipulation tools to establish causal relationships between molecular changes and behavioral outcomes, and human cellular models that capture the developmental trajectory of these convergent pathways. As our understanding of these interactive mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to develop targeted interventions that address the core biological processes underlying ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior [24] [23]. The neurobiological underpinnings of ASD involve a complex interplay of genetic, molecular, and structural factors, with cortical thickening and altered neural circuitry representing central features in its pathophysiology. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on structural brain abnormalities in ASD, framing these findings within a convergent disease mechanisms model that links genetic susceptibilities to macroscopic brain phenotypes and clinical manifestations.

The prevalence of ASD has been steadily increasing, with current estimates indicating approximately 1 in 36 individuals in the United States receives this diagnosis [24]. A significant proportion (approximately 38%) of autistic individuals also have co-occurring intellectual disability (ID), highlighting the considerable heterogeneity in cognitive functioning within the spectrum [24]. Understanding the neuroanatomical correlates of this heterogeneity remains a pivotal challenge for researchers and clinicians alike.

This technical review examines the structural brain abnormalities in ASD through the lens of convergent disease mechanisms, wherein disparate genetic and molecular pathways ultimately manifest in shared neuroanatomical phenotypes. We present a comprehensive analysis of cortical thickness alterations, their developmental trajectories, and associated disruptions in neural circuitry, providing drug development professionals with mechanistic insights for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Cortical Thickness Alterations in ASD

Regional Patterns of Cortical Thickening

Cortical thickness (CTh), measured as the distance between the gray-white matter interface and the pial surface, provides a sensitive metric for evaluating cortical maturation abnormalities in ASD [25]. Multiple studies have consistently identified regional patterns of cortical thickening, particularly in early development.

Table 1: Regional Cortical Thickness Abnormalities in ASD Youth

| Brain Region | Direction of Change | Developmental Period | Clinical Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superior Frontal Gyrus | Increased | Childhood | Executive function deficits |

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | Increased | Childhood | Social cognition challenges |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | Increased | Childhood | Sensory processing issues |

| Temporoparietal Junction | Decreased | Childhood-Adolescence | Social attention deficits |

| Entorhinal Cortex | Negative correlation with IQ | Early Childhood (mean age 5.37) | Intellectual ability |

| Fusiform Gyrus | Negative correlation with IQ | Early Childhood (mean age 5.37) | Face processing |

In young autistic children aged 2-4 years, widespread increased cortical thickness and volume is particularly evident within frontal and parietal regions [26]. This pattern of frontal-parietal thickening appears most prominent in early childhood, with one study of children with a mean age of 5.37 years showing significant negative associations between IQ and cortical thickness in bilateral entorhinal cortex, right fusiform gyrus, and superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri [24]. Notably, autistic children with intellectual disability (IQ ≤ 70) demonstrated significantly thicker cortex in these regions compared to those without ID [24].

A comparative meta-analysis of youth with ASD revealed increased cortical thickness in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus, left middle temporal gyrus, and right superior parietal lobule, alongside decreased thickness in the right temporoparietal junction compared to typically developing controls [25]. This regional pattern suggests that cortical thickening in ASD preferentially affects higher-order associative cortices involved in social cognition, executive function, and sensory integration.

Developmental Trajectories

The developmental course of cortical thickness abnormalities in ASD follows a complex, nonlinear trajectory characterized by early overgrowth followed by altered maturation patterns. Evidence suggests a dynamic developmental shift from gray matter overgrowth to delayed maturation during adolescence [27].

Table 2: Developmental Trajectory of Gray Matter Volume in ASD

| Developmental Stage | Gray Matter Profile | Key Regions Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood (2-4 years) | Significant overgrowth | Frontal and parietal lobes |

| Early Adolescence (8-13 years) | Positive GMV deviations | Superior temporal sulcus, cingulate gyrus, insula |

| Late Adolescence (13-18 years) | Negative GMV deviations | Superior parietal lobule, attention networks |

| Adulthood | Normalization or reduced volume | Widespread cortical regions |

Longitudinal neuroimaging studies indicate that excessive brain growth in ASD predominantly occurs in the first months after birth [23]. Children diagnosed with ASD show a generalized increase in cortical volume at 2 years of age, with significantly larger volumes of both gray and white matter [23]. This early overgrowth pattern is followed by a period of accelerated cortical thinning during adolescence, with one study of individuals aged 8-18 years revealing a shift from positive gray matter volume deviations in early adolescence to negative deviations in late adolescence [27].

The subregion of the temporoparietal junction located in the default mode network shows reduced thickness in both ASD and ADHD, suggesting this may represent a shared neurobiological feature across neurodevelopmental conditions [25]. However, disorder-specific alterations are evident in other regions, with ASD showing greater cortical thickness in the right superior parietal lobule and temporoparietal junction located in the dorsal attention network compared to ADHD [25].

Altered Neural Circuitry in ASD

Synaptic Density and Connectivity

Beyond macroscopic cortical thickness alterations, ASD is characterized by fundamental differences in synaptic organization and neural circuitry. A groundbreaking study using positron emission tomography (PET) with a novel radiotracer (11C‑UCB‑J) revealed that autistic adults have significantly fewer synapses—approximately 17% lower synaptic density across the whole brain—compared to neurotypical individuals [28]. Furthermore, the degree of synaptic deficit correlated with behavioral manifestations, with lower synaptic density associated with greater numbers of social-communication differences [28].

The investigation of synaptic connectivity has revealed crucial insights into ASD pathophysiology. Previous research relied on animal models or post-mortem studies, but the introduction of novel PET scanning protocols now enables direct measurement of synaptic density in living humans [28]. This technological advancement provides unprecedented opportunities for quantifying treatment response and disease progression in clinical trials.

Network-Level Alterations

Network-based analyses reveal that atypical morphological development in ASD is constrained by intrinsic functional network architecture. Using network diffusion modeling, researchers have demonstrated that distribution deviations of gray matter volume at preceding age stages significantly predict subsequent developmental alterations [27]. This suggests that functional networks provide an organizational framework that shapes structural development in ASD.

A multimodal meta-analysis combining 23 functional imaging and 52 structural MRI studies provided large-scale evidence of convergent abnormalities in ASD, reporting decreased resting-state activity in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex/medial prefrontal cortex (ACC/mPFC), alongside increased gray matter volume in the middle temporal gyrus and olfactory cortices [18]. These findings highlight the insula and ACC/mPFC as core regions implicated in both structural and functional pathology of ASD, supporting the notion that default mode network dysfunction and atypical motor/sensory processing contribute fundamentally to ASD neurobiology.

Atypical morphological regions in ASD, particularly those in the superior temporal sulcus, cingulate gyrus, insula, and superior parietal lobule, are predominantly located within salience/ventral attention networks (28.26% of regions) [27]. Meta-analytic decoding indicates these regions are predominantly associated with cognitive control, response inhibition, and inhibitory control functions [27]. When mapped onto the brain's functional gradient space, these atypical regions predominantly situate at the transmodal end of Gradient 1, indicating a topographical bias toward higher-order associative cortices [27].

Methodological Approaches

Neuroimaging Protocols

The characterization of cortical structure and neural circuitry in ASD relies on sophisticated neuroimaging methodologies with specific technical requirements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Research Reagent/Technique | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 3T MRI Scanner | High-resolution structural imaging | Enables cortical thickness measurement |

| FreeSurfer Software Suite | Automated cortical reconstruction | Uses Desikan-Killiany atlas for parcellation |

| 11C‑UCB‑J Radiotracer | Quantifying synaptic density via PET | Yale PET Center development |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) | Behavioral phenotyping | Gold standard for diagnosis |

| HYDRA Algorithm | Semi-supervised clustering | Identifies neuroanatomical subgroups |

| Population Modelling | Individual-level deviation scores | Creates neuroanatomical "growth charts" |

Structural MRI protocols for cortical thickness analysis typically employ T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequences at 3T, providing high-resolution anatomical images. Cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation is performed using automated pipelines such as FreeSurfer, which calculates cortical thickness by measuring the distance between the gray-white matter boundary and the pial surface at each vertex across the cortical mantle [29].

For synaptic density quantification, researchers employ PET imaging with the novel radiotracer 11C‑UCB‑J, which selectively binds to synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A), a protein ubiquitously expressed in synaptic terminals [28]. This technique enables in vivo measurement of synaptic density in specific brain regions, offering a direct marker of synaptic integrity.

Analytical Frameworks

Advanced analytical approaches have been developed to address the substantial heterogeneity in ASD neurobiology. Population modeling, also known as normative modeling, quantifies individual variation in relation to population norms, generating centile or "deviation" scores analogous to conventional pediatric growth charts [29]. This approach allows researchers to examine individual subjects from different sites in a common space relative to a reference group, facilitating the identification of distinct neuroanatomical subtypes.

Novel clustering algorithms such as HYDRA (HeterogeneitY through DiscRiminative Analysis) enable identification of subgroups based explicitly on differences within clinical cohorts relative to controls [29]. This semi-supervised machine learning approach clusters individuals based on structural MRI measurements, revealing subgroups with distinct neuroanatomical profiles that may reflect different underlying biological mechanisms.

Network diffusion modeling provides a framework for simulating the dynamic spread of morphological alterations across brain networks [27]. This approach models how distribution deviations of gray matter volume propagate through structural and functional networks across development, offering insights into how local alterations may lead to system-level reorganization in ASD.

Diagram 1: Convergent Disease Mechanisms in ASD. This framework illustrates how diverse genetic and molecular factors converge on shared structural and circuit-level abnormalities, ultimately manifesting in core clinical features of ASD.

Experimental Workflows

Cortical Thickness Analysis Pipeline

The assessment of cortical thickness abnormalities in ASD follows a standardized workflow with multiple quality control checkpoints.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Cortical Structure Analysis. This workflow outlines the standardized pipeline for assessing cortical thickness in ASD research, from data acquisition through analytical approaches.

The analytical phase incorporates both group-level and individual-level approaches. Population modeling using Generalized Additive Models of Location Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) generates centile scores that represent an individual's neuroanatomical profile relative to same-sex and same-age expectations [29]. These centile scores enable the identification of subgroups within the ASD population that may have distinct neurobiological underpinnings.

For subgroup identification, the HYDRA algorithm clusters individuals based on differences relative to a control sample, using structural MRI measurements as input features [29]. This approach has revealed distinct subgroups within autism and ADHD with often opposite neuroanatomical alterations relative to controls, characterized by different combinations of increased or decreased patterns of morphometrics [29].

Synaptic Density Quantification Protocol

The quantification of synaptic density in living humans represents a methodological breakthrough in ASD research. The experimental protocol involves:

- Participant Screening: Comprehensive clinical characterization using ADOS and exclusion of medical conditions that could influence study findings [28].

- Multimodal Imaging: Combination of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for anatomical reference and positron emission tomography (PET) for synaptic density measurement [28].

- Radiotracer Administration: Intravenous injection of the novel radiotracer 11C‑UCB‑J, developed at the Yale PET Center, which binds to synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) [28].

- Image Acquisition and Reconstruction: PET data acquisition followed by reconstruction and correction for attenuation, scatter, and radioactive decay.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculation of synaptic density metrics through kinetic modeling of radiotracer binding, typically expressed as distribution volume or binding potential.

- Correlation with Phenotype: Statistical analysis relating synaptic density measures to clinical features, such as social communication differences and repetitive behaviors [28].

This protocol has revealed that autistic individuals have significantly lower synaptic density than neurotypical individuals, and that the degree of synaptic deficit correlates with the severity of autistic features [28].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The structural and circuit-level abnormalities in ASD present promising targets for therapeutic intervention. The identification of specific patterns of cortical thickening and synaptic deficits provides biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment response monitoring in clinical trials.

The convergent disease mechanisms framework suggests that targeting fundamental processes like synaptic function or neuroimmune regulation may yield benefits across ASD subtypes with diverse genetic origins [18] [30]. The development of synaptic density as a measurable biomarker enables direct assessment of target engagement for therapies aimed at correcting synaptic deficits.

The temporal trajectory of cortical abnormalities in ASD—with early overgrowth followed by accelerated thinning—suggests the existence of critical windows for intervention. Therapeutics administered during periods of peak cortical development may have enhanced potential to modify disease trajectory. Furthermore, the identification of neuroanatomical subgroups within ASD indicates that personalized approaches targeting specific biological subtypes may yield better outcomes than one-size-fits-all interventions.

Structural brain abnormalities, particularly cortical thickening and altered neural circuitry, represent core pathological features of ASD that emerge from convergent disease mechanisms. The regional specificity of cortical thickness alterations, their dynamic developmental trajectories, and associated synaptic deficits provide a neurobiological framework for understanding the heterogeneous clinical presentation of ASD.

Advanced neuroimaging methodologies and analytical approaches have enabled precise characterization of these abnormalities, revealing distinct subtypes within the autism spectrum. These findings provide a foundation for developing targeted therapeutic strategies and biomarkers for tracking treatment response. For drug development professionals, these insights highlight the importance of considering neuroanatomical heterogeneity in clinical trial design and the potential of targeting fundamental synaptic and network-level processes in ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. The excitation-inhibition (E/I) imbalance hypothesis posits that altered ratios of excitatory glutamatergic signaling to inhibitory GABAergic signaling represent a core pathophysiological mechanism underlying ASD. This whitepaper synthesizes evidence from genetic, molecular, cellular, and systems neuroscience to elucidate how dysregulation of these neurotransmitter systems converges to disrupt neural circuit function. We summarize key quantitative findings, detail essential experimental methodologies, and highlight emerging therapeutic targets for restoring E/I balance, providing a comprehensive technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The excitation-inhibition (E/I) imbalance theory, initially proposed by Rubenstein and Merzenich, suggests that ASD arises from a disruption of neuronal network activity due to perturbation of the synaptic excitation and inhibition balance [31]. This imbalance, characterized by an increased E/I ratio, is thought to lead to hyper-excitability in cortical circuitry and potentially enhanced levels of neuronal noise, which underlies the learning and memory, cognitive, sensory, motor deficits, and seizures occurring in ASD [32]. The E/I balance is crucial for normal brain development and function, regulated through homeostatic processes at both single-cell and large-scale neuronal circuit levels [31]. At the single neuron level, the balance between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs is critical for information processing, while at the network level, E/I balance maintains stable global activity within particular circuits, enabling optimal response to salient inputs [31]. In ASD, this precise regulation is disrupted through multiple convergent mechanisms affecting primarily glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission in key brain regions such as neocortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum [32].

GABAergic System Dysregulation

Molecular and Genetic Mechanisms

The GABAergic system constitutes the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter system in the vertebrate central nervous system. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is synthesized from glutamate by the rate-limiting enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), which exists in two isoforms: GAD65 (encoded by GAD2) and GAD67 (encoded by GAD1) [33]. Genetic evidence has identified variations in genes associated with the GABA system, including those encoding GAD enzymes, GABA receptors, and transporters, implicating abnormal E/I neurotransmission ratio in ASD pathogenesis [34] [35]. Postmortem studies reveal significant alterations in GABA receptor expression, with downregulation of GABAA receptor subunits (GABRA1, GABRA2, GABRA3, GABRB3) in cerebellum and cortical areas, and decreased protein levels of the α2 subunit of GABAA receptors in the prefrontal cortex of autistic individuals [34]. Furthermore, genes such as GABRA3, ARX, and MECP2 located on the X chromosome may contribute to the sex bias observed in ASD prevalence [36].

Neuroimaging and Biochemical Evidence

Table 1: GABAergic Alterations in ASD from Human Studies

| Modality | Brain Region | Findings in ASD | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) | Sensorimotor Cortex | ↓ GABA concentrations [34] | Associated with tactile hypersensitivity [34] |

| MRS | Anterior Cingulate Cortex | ↓ GABA/creatine levels [34] | - |

| MRS | Frontal Lobes | ↓ GABA/glutamate ratio [34] | - |

| MRS | Visual Cortex | ↑ GABA concentration (children) [34] | Related to efficient search and social impairments [34] |

| MRS | Thalamus | GABA levels correlate with AQ in gender-specific way [34] | Negative correlation in males, positive in females [34] |

| Plasma/Serum Analysis | Peripheral Blood | ↑ Plasma GABA levels [34] | Decreases with age [34] |

| Postmortem Analysis | Cerebellum | ↑ GAD67 mRNA [34] | Disturbance of intrinsic cerebellar circuitry [34] |

| Postmortem Analysis | Hippocampus | ↑ Density of CB+, CR+, PV+ interneurons [34] | - |

| Postmortem Analysis | Prefrontal Cortex | ↓ GABAA α2 subunit protein [34] | - |

Interneuron Pathology

GABAergic inhibition is primarily mediated by interneurons, which display significant pathology in ASD. In the mammalian brain, inhibitory GABAergic neurons are primarily interneurons, including parvalbumin (PV)-expressing, somatostatin (SST)-expressing, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)-expressing, and ionotropic serotonin receptor (5HT3a)-expressing subtypes [33]. These interneurons originate from the medial and caudal ganglionic eminences (MGE and CGE) during embryonic development and migrate to various brain regions. Postmortem studies show a selective increase in the density of calbindin (CB)+, calretinin (CR)+, and parvalbumin (PV)+ interneurons in the hippocampus of individuals with ASD [34]. Single-cell transcriptomics indicates downregulation of transcription factors such as AHI1 and synaptic genes like RAB3A in VIP interneurons of ASD patients, with SFARI genes relatively enriched in VIP and SST interneurons [33]. This disruption affects inhibitory regulation between neurons, thereby disrupting the E/I balance in the brain and promoting core ASD symptoms.

Glutamatergic System Dysregulation

Receptor Dysfunction and Signaling Pathways

Glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, acts through ionotropic (iGluRs) and metabotropic (mGluRs) receptors. iGluRs include N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), and kainate receptors, which are non-selective cation channels [37]. mGluRs are G-protein coupled receptors categorized into three groups: Group I (mGluR1, mGluR5), Group II (mGluR2, mGluR3), and Group III (mGluR4, mGluR6-8) [37]. Genetic and molecular studies demonstrate significant alterations in glutamate receptor expression and function in ASD. For instance, higher levels of mGluR5 protein have been found in the cerebellar vermis and superior frontal cortex of children with autism [37]. Group I mGluRs are particularly implicated in ASD pathophysiology through their association with NMDA receptors and regulation of long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) [37].

Figure 1: Glutamatergic Signaling Pathways in ASD. This diagram illustrates key glutamate receptors and their downstream signaling cascades implicated in ASD pathophysiology, including AMPA, NMDA, and mGluR5 receptors and their roles in synaptic plasticity.

Peripheral and Central Glutamate Alterations

Table 2: Glutamatergic Alterations in ASD from Human Studies

| Modality | Brain Region/ Sample | Findings in ASD | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum Analysis | Peripheral Blood | ↑ Serum/plasma glutamate [38] | Higher levels associated with poorer social ability [38] |

| Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) | Right Hippocampus | ↑ Glx levels [38] | - |

| MRS | Anterior Cingulate Gyrus | ↑ Glutamate concentration [38] | - |

| MRS | Auditory Cortex | ↑ Glutamate concentration [38] | - |

| MRS | Frontal Lobe | ↓ GABA/glutamate ratio [34] | - |

| Postmortem Analysis | Anterior Cingulate Cortex | ↑ Glutamate and glutamine [38] | - |

| Postmortem Analysis | Superior Frontal Cortex | ↑ mGluR5 protein [37] | - |

Multiple studies report elevated glutamate levels in blood plasma and serum of individuals with ASD. Shinohe et al. (2006) found significantly higher serum glutamate levels in adult subjects with autism compared to healthy controls, with social subscale scores on the ADI-R correlating with glutamate levels (higher serum glutamate associated with poorer social ability) [38]. Direct measurement from post-mortem brain tissue using high performance liquid chromatography has shown elevations in glutamate and glutamine from the anterior cingulate cortex in individuals with autism [38]. In-vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) studies have reported increased glutamate and Glx (combined glutamate and glutamine measure) in several brain regions including the right hippocampus, anterior cingulate gyrus, and auditory cortex [38].

Genetic Evidence for Glutamatergic Involvement

Genetic studies provide compelling evidence for glutamatergic system involvement in ASD pathogenesis. Genes encoding glutamate transporters (SLC1A1, SLC1A2) show single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with autism, with SNP rs301430 in SLC1A1 linked with repetitive behaviors and anxiety in children with ASD [37]. Two SNPs (rs2056202 and rs2292813) in the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier gene SLC25A12 are also associated with autism [37]. Furthermore, genes regulating synaptic structure and function that are highly mutated in ASD, including neuroligin-3 (NLGN3), neuroligin-4 X-linked (NLGN4X), neurexin1 (NRXN1), and SHANK3, play significant roles in glutamatergic synaptic functioning [37]. Deletions and structural variations in neurexin genes (NRXN1, NRXN2, NRXN3) are associated with autism phenotypes, highlighting the importance of pre-synaptic glutamatergic proteins in ASD pathophysiology [37].

Convergent Mechanisms of E/I Imbalance

Synaptic Dysregulation

The E/I imbalance in ASD arises from convergent disruptions at synaptic levels, affecting both glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission. At excitatory synapses, numerous ASD-risk genes encode proteins involved in synaptic plasticity, including SHANK- and NRXN-family genes, which modulate synaptic strength, cell adhesion, and neuronal connectivity [31]. At inhibitory synapses, impaired GABAergic signaling disrupts the equilibrium necessary for normal brain function. This synaptic dysregulation leads to altered functional connectivity and network activity, as demonstrated by multi-electrode array (MEA) recordings of iPSC-derived neurons from ASD patients, which show marked hyperexcitability in glutamatergic neurons and reduced synaptic activity depending on the specific genetic variant [31].

Sex-Specific Manifestations

E/I imbalance affects autistic males and females differently, providing crucial insights into ASD heterogeneity. Research using fMRI BOLD signal analysis has revealed that the Hurst exponent (H), an index of synaptic E/I ratio, is reduced in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) of autistic males but not females, indicating increased excitation specifically in males [36]. Furthermore, increasingly intact MPFC H is associated with heightened ability to behaviorally camouflage social-communicative difficulties, but only in autistic females [36]. This suggests that E:I imbalance affects key social brain regions more prominently in males, while females may employ compensatory mechanisms that depend on maintained E/I balance in these regions. Many highly penetrant ASD-associated genes are located on the sex chromosomes (e.g., FMR1, MECP2, NLGN3, GABRA3) and are known to lead to pathophysiology implicating E:I dysregulation [36].

Circuit-Level Effects

The convergence of GABAergic and glutamatergic dysregulation leads to altered function in specific neural circuits underlying ASD symptoms. The "social brain" network, including medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), amygdala, and hippocampus, appears particularly vulnerable to E/I imbalance [36]. Optogenetic stimulation to enhance excitation in mouse MPFC results in changes in social behavior, demonstrating the causal relationship between E/I balance in specific circuits and ASD-relevant behaviors [36]. In the amygdala-nucleus accumbens circuit, weakening of GABAergic inhibition results in social avoidance, while abnormal projections from PV-positive GABAergic neurons in the hippocampal-cortical circuit can reversibly improve social deficits in ASD mouse models [33]. These circuit-specific effects illustrate how localized E/I imbalances translate to particular behavioral manifestations of ASD.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Human iPSC-Derived Models

The development of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has enabled modeling of ASD using human neurons, providing unprecedented opportunities to investigate E/I imbalance mechanisms. iPSCs are generated by reprogramming patient-derived somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells) through overexpression of pluripotency-associated transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, cMyc) [31]. These cells can then be differentiated into various neuronal lineages, allowing researchers to study the effects of ASD-risk genes on human neuronal development and function. This approach provides a valuable model for analyzing the consequences of genetic dysfunctions on neuronal networks, serving as a complement to animal models [31].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for iPSC-Based ASD Modeling. This diagram outlines the key steps in generating and analyzing human iPSC-derived neuronal models for studying E/I imbalance in ASD, from somatic cell reprogramming to functional characterization.

Electrophysiological Assessment

Multi-electrode array (MEA) technology enables non-invasive, real-time, multi-point measurement of activity in cultured neuronal networks, allowing investigation of developmental modifications of synaptic connectivity and network activity [31]. This system is particularly valuable for evaluating plasticity of iPSC-derived neuronal networks and investigating molecular bases of E/I imbalance in ASD. Studies utilizing MEA recordings have identified marked hyperexcitability in glutamatergic neurons lacking one copy of CNTN5 or EHMT2, as well as reduced synaptic activity in ATRX-, AFF2-, KCNQ2-, SCN2A-, and ASTN2-null neurons [31]. These findings indicate that ASD-risk genes from different functional categories can produce similar electrophysiological phenotypes, revealing common functional alterations in network activity.

Neuroimaging and Spectroscopy