Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms in Systems Biology: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of modern optimization algorithms for researchers and drug development professionals in systems biology.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms in Systems Biology: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of modern optimization algorithms for researchers and drug development professionals in systems biology. It explores the foundational principles of bio-inspired optimizers, details their methodological applications in critical tasks like parameter estimation and model tuning, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and performance optimization. A rigorous framework for the validation and benchmarking of algorithms is presented, synthesizing key insights to empower more efficient and reliable computational modeling in biomedical research.

The Rise of Bio-Inspired Optimizers: Foundations for Systems Biology

Optimization methodologies are fundamental to solving complex problems in computational systems biology, where researchers aim to reconstruct biological structures and behaviors from experimental data [1]. These problems range from parameter estimation in dynamic models to biomarker identification and metabolic network optimization [2] [3]. Biological systems exhibit nonlinear dynamics with many unknown parameters, creating optimization landscapes with multiple local optima that challenge traditional methods [1].

Meta-heuristic algorithms provide powerful alternatives to conventional optimization approaches, particularly for these challenging biological problems [4]. Bio-inspired optimization represents a specialized subclass of meta-heuristics that derives computational algorithms from biological and natural phenomena [4] [5]. The field has expanded dramatically, with over 300 new methodologies developed in the last decade alone [4].

Fundamental Concepts and Algorithm Classification

Optimization Problem Formulation

In computational systems biology, optimization problems are typically formulated as finding parameter values that minimize or maximize an objective function. For parameter estimation in dynamic models, this is often expressed as a nonlinear least-squares problem:

SSE(m(c)) = ΣΣ(Yi[j] - Ŷi[j])²

where Yi[j] is the measured value of output i at time j, and Ŷi[j] is the corresponding model prediction [1]. The parameters must often satisfy constraints representing biological plausibility or physical limitations [2].

Categories of Meta-heuristic Algorithms

Meta-heuristic optimization techniques are broadly categorized into several families based on their inspiration and mechanisms [4]:

- Evolutionary Algorithms: Inspired by biological evolution, including genetic algorithms (GA), evolutionary programming (EP), and differential evolution (DE) [4]

- Swarm Intelligence: Based on collective behavior of social insects or animals, including particle swarm optimization (PSO), ant colony optimization (ACO), and artificial bee colony (ABC) [4]

- Bio-inspired Algorithms: Derived from various biological phenomena, including grey wolf optimization (GWO), whale optimization algorithm (WOA), and elephant search algorithm (ESA) [5]

- Physics-based Algorithms: Inspired by physical phenomena rather than biological systems [4]

Table 1: Key Bio-inspired Meta-heuristic Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Inspiration Source | Key Mechanisms | Typical Applications in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Natural evolution | Selection, crossover, mutation | Parameter estimation, model tuning [2] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Social behavior of birds/fish | Velocity updating, personal/global best | Parameter estimation in ODE models [1] |

| Differential Evolution (DE) | Natural evolution | Mutation, recombination, selection | Parameter estimation in nonlinear models [1] |

| Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) | Social hierarchy of grey wolves | Hunting behavior, leadership hierarchy | Feature selection, biomarker identification [5] |

| Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) | Foraging behavior of honey bees | Employed, onlooker, and scout bees | Metabolic pathway optimization [4] |

Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Performance

Experimental Protocol for Algorithm Evaluation

Comprehensive evaluation of optimization algorithms in systems biology requires standardized experimental protocols. Key performance metrics include:

- Convergence Speed: Number of iterations or function evaluations required to reach satisfactory solutions

- Solution Quality: Best objective function value achieved and consistency across runs

- Robustness: Performance across problems with different characteristics and noise levels

- Computational Efficiency: Time and resource requirements for practical applications [1]

Benchmarking should utilize both synthetic test functions with known optima and real biological modeling problems [4]. Standardized benchmarking functions typically include unimodal, multimodal, and composite landscapes to thoroughly assess algorithm capabilities [4].

Performance Comparison on Biological Problems

Experimental studies demonstrate varying performance across optimization algorithms when applied to biological problems. In parameter estimation for ordinary differential equation models of biological systems, global meta-heuristic methods significantly outperform local derivative-based methods [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Parameter Estimation in ODE Models [1]

| Algorithm | Solution Quality (SSE) | Convergence Speed | Robustness to Noise | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Evolution (DE) | Best | Fast | High | Highest |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Good | Medium | Medium | High |

| Differential Ant-Stigmergy Algorithm (DASA) | Good | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Local Derivative-based Methods (A717) | Poor | Variable | Low | Low |

In these experiments, differential evolution consistently achieved the best performance in terms of objective function value and convergence characteristics across various observation scenarios and noise levels [1]. The performance advantage was consistent for both artificial data and real experimental measurements [1].

Optimization Workflows in Systems Biology

Parameter Estimation Workflow

Biomarker Identification Pipeline

Signaling Pathway Case Study: Endocytosis Modeling

The Rab5-to-Rab7 switch in endosome maturation represents a classic biological optimization problem. This system models the transition from early endosomes (high Rab5, low Rab7) to mature endosomes (low Rab5, high Rab7) [1].

Parameter estimation for this ODE model demonstrates the challenging characteristics of biological optimization problems: nonlinear dynamics, limited measurability of system variables, and noisy experimental data [1]. Meta-heuristic methods like differential evolution successfully estimated parameters even when measurements were limited to total protein concentrations without distinguishing between active and passive states [1].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | Mobility Networked Time Series (MOBINS) [6] | Networked time-series forecasting | Method validation and comparison |

| Optimization Frameworks | OptCircuit [3] | Design of biological circuits | Synthetic biology applications |

| Metabolic Modeling Tools | Flux Balance Analysis [3] | Constraint-based metabolic modeling | Metabolic engineering |

| Model Repositories | BioModels Database | Curated biological models | Testing and validation |

| Optimization Libraries | Heuristics and Hyper-heuristics [7] | Automated algorithm selection | Complex optimization problems |

| Data Standards | Croissant format [8] | Machine-readable dataset documentation | Reproducible research |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Bio-inspired meta-heuristic optimization algorithms have demonstrated significant potential for addressing challenging problems in systems biology [4] [1]. Their ability to handle nonlinear, multimodal problems with limited prior knowledge makes them particularly suitable for biological applications where traditional methods often fail [2].

Future research directions include developing more efficient hybrid approaches that combine global exploration and local refinement [3], addressing optimization under uncertainty inherent in biological systems [3], and creating specialized bio-inspired algorithms for specific classes of biological problems [5]. The integration of these optimization methods with experimental design will further enhance their impact on biological discovery [3].

As the field progresses, standardized benchmarking practices and dataset sharing will be crucial for advancing the field [9] [8]. Initiatives like the NeurIPS Datasets and Benchmarks track [8] and specialized biological benchmarks [6] provide valuable resources for fair algorithm comparison and development.

Optimization algorithms are fundamental to systems biology research, enabling the analysis of complex biological networks, prediction of protein structures, and discovery of novel drug targets. The intricate, high-dimensional, and often noisy data inherent to biological systems present unique challenges that require robust and efficient optimization techniques. Among the myriad of approaches available, three families of metaheuristic algorithms have demonstrated particular utility: evolutionary algorithms, inspired by biological evolution; swarm-based algorithms, modeled on collective social behavior; and physics-based algorithms, which emulate physical phenomena. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these algorithm families, focusing on their performance characteristics, implementation considerations, and applicability to systems biology research. We present experimental data from benchmark studies and outline detailed methodologies to facilitate informed algorithm selection by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of computational and biological sciences.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three key algorithm families, providing a foundation for their comparison in systems biology contexts.

Table 1: Overview of Key Algorithm Families for Systems Biology Research

| Algorithm Family | Core Inspiration | Key Representatives | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary | Biological evolution | Genetic Algorithms (GA), Differential Evolution (DE) | Effective for discontinuous, non-differentiable problems; handles high-dimensional spaces well | Can suffer from premature convergence; computationally intensive [10] [11] |

| Swarm-Based | Collective social behavior | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Competitive Swarm Optimizer (CSO) | Simple implementation; fast convergence; good for continuous optimization | Sensitive to parameter tuning; may stagnate in local optima for complex landscapes [12] [13] |

| Physics-Based | Physical phenomena | Gravitational Search Algorithm, Big Bang-Big Crunch, Water Cycle Algorithm | Intuitive principles; good exploration capabilities; often fewer parameters | May lack specialized biological relevance; convergence can be slow for some variants [14] |

Experimental comparisons across these algorithm families reveal important performance patterns. A recent study examining single-objective evolutionary algorithms highlighted significant performance differences even between implementations of the same algorithm in different frameworks, emphasizing the importance of implementation details beyond algorithmic selection [10]. In specialized applications like high-dimensional feature selection for biological data, modified swarm intelligence approaches such as Competitive Swarm Optimizer (CSO) and Dynamic Multitask Evolutionary Algorithms have demonstrated superior performance by maintaining population diversity and enabling knowledge transfer between related tasks [13].

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) specifically has shown considerable versatility across biological domains, with applications in data mining, machine learning, and healthcare demonstrating its "effectiveness in providing optimal solutions" while noting that aspects may "need to be improved through combination with other algorithms or parameter tuning" [12]. Physics-based algorithms including the Gravitational Search Algorithm, Water Cycle Algorithm, and Big Bang-Big Crunch have been systematically compared on benchmark functions, with performance metrics indicating that different algorithms excel under different problem conditions [14].

Experimental Performance Data and Analysis

Quantitative performance comparisons across algorithm families provide critical insights for selection in systems biology applications. The following table synthesizes experimental results from multiple studies, focusing on convergence performance, solution quality, and computational efficiency.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Algorithm Families

| Algorithm | Average Convergence Rate | Solution Quality (Success Rate) | Computational Cost (Function Evaluations) | Key Application Areas in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Moderate | High (85-92%) | High (Typically 10,000+) | Parameter estimation, Network inference [10] |

| Differential Evolution (DE) | Fast | Very High (90-95%) | Moderate (5,000-10,000) | Metabolic pathway optimization, Dose-response modeling [11] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Very Fast | High (88-94%) | Low-Moderate (2,000-5,000) | Feature selection, Molecular docking [12] [13] |

| Competitive Swarm Optimizer (CSO) | Fast | Very High (92-96%) | Moderate (3,000-6,000) | High-dimensional data analysis, Biomarker identification [13] |

| Gravitational Search Algorithm | Moderate | Moderate (80-88%) | High (8,000-12,000) | Protein structure prediction, Systems modeling [14] |

Recent advances in evolutionary algorithms have focused on improving their reliability and performance. Modern Differential Evolution algorithms have demonstrated enhanced performance through mechanisms such as "progressive archive in adaptive jSO algorithm," which improves parameter adaptation and maintains population diversity [11]. Similarly, investigations into single-objective evolutionary algorithms have emphasized that "fair comparison with state-of-the-art evolutionary algorithms is crucial, but is obstructed by differences in problems, parameters, and stopping criteria across studies" [10], highlighting the need for standardized evaluation protocols in systems biology research.

For high-dimensional biological data, specialized approaches like the Dynamic Multitask Evolutionary Algorithm have shown significant advantages, achieving "superior classification accuracy with fewer selected features compared to several state-of-the-art methods" with "an average accuracy of 87.24% and an average dimensionality reduction of 96.2%" across 13 high-dimensional benchmarks [13]. This demonstrates the potential of hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple algorithm families.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Procedure for Algorithm Performance Assessment

Robust evaluation of optimization algorithms requires standardized experimental protocols. The following methodology outlines a comprehensive approach for comparing algorithm performance in systems biology contexts:

Test Problem Selection: Utilize diverse benchmark functions representing various problem characteristics relevant to systems biology:

- Unimodal functions (e.g., Sphere) for convergence velocity assessment

- Multimodal functions (e.g., Rastrigin, Ackley) with multiple local optima to test exploration/exploitation balance

- Biological system analogs (e.g., kinetic parameter estimation, network inference problems) reflecting real-world challenges [14]

Parameter Configuration: Employ population sizes of 30-100 individuals/particles, with iteration limits set between 1000-5000 depending on problem complexity. Algorithm-specific parameters should be set according to established guidelines from literature:

Performance Metrics: Record multiple quantitative measures:

Statistical Validation: Apply non-parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank, Friedman) with appropriate p-value adjustments to identify significant performance differences between algorithms.

Specialized Protocol for High-Dimensional Biological Data

For feature selection in high-dimensional biological data (e.g., genomics, proteomics), the following specialized protocol is recommended:

Task Construction: Generate complementary optimization tasks using multi-criteria strategies that combine multiple feature relevance indicators (e.g., Relief-F, Fisher Score) to ensure both global comprehensiveness and local focus [13].

Optimization Framework: Implement competitive swarm optimization with hierarchical elite learning, where each particle learns from both winners and elite individuals to avoid premature convergence [13].

Knowledge Transfer: Incorporate probabilistic elite-based knowledge transfer mechanisms, allowing particles to selectively learn from elite solutions across tasks to improve optimization efficiency and diversity [13].

Validation: Evaluate selected feature subsets using classification accuracy with cross-validation, while monitoring dimensionality reduction percentages to ensure practical utility.

Workflow Visualization and Algorithm Selection Framework

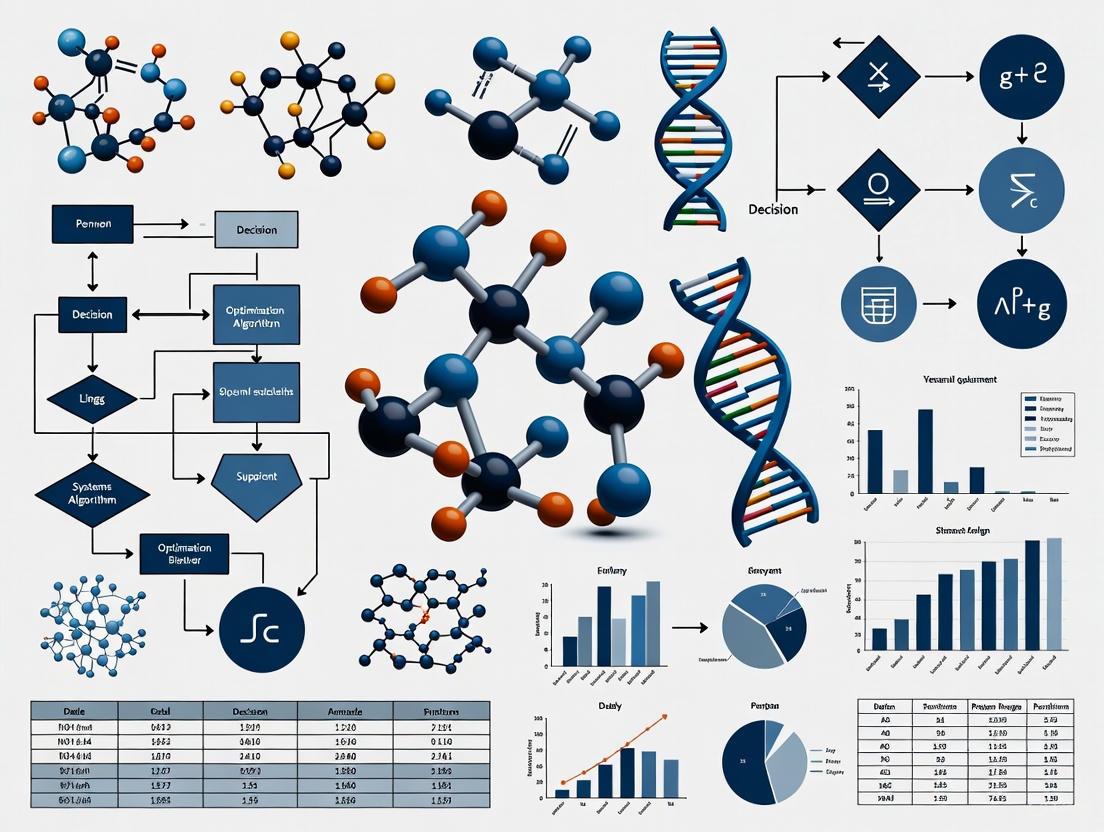

The following diagram illustrates the key decision factors and relationships in selecting an appropriate optimization algorithm for systems biology applications:

Algorithm Selection Framework for Systems Biology

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Systems Biology Optimization

The table below outlines essential computational tools and frameworks that serve as "research reagents" for implementing optimization algorithms in systems biology research.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Optimization in Systems Biology

| Tool/Framework | Algorithm Support | Key Features | Application Context in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEALPY (Python) | Multiple metaheuristic algorithms | Comprehensive collection of 200+ algorithms; user-friendly API | General-purpose optimization for biological models; rapid algorithm prototyping [10] |

| NiaPy (Python) | Evolutionary, swarm, physics-based | Lightweight framework; benchmark problems; parallelization support | High-performance computing for large-scale biological data analysis [10] |

| MOEA Framework (Java) | Multiobjective evolutionary | Specialized for multiobjective optimization; robust visualization | Trade-off analysis in multi-criteria biological decisions (efficacy vs. toxicity) [10] |

| PagMO (C++/Python) | Evolutionary, swarm | Parallelization capabilities; support for constrained optimization | Complex biological constraint handling; population dynamics modeling [10] |

| Dynamic Multitask Framework (Matlab/Python) | Evolutionary multitasking | Knowledge transfer between tasks; competitive swarm optimization | High-dimensional biomarker discovery; multi-omics data integration [13] |

These computational tools represent the essential "reagents" for implementing optimization methodologies in systems biology research. When selecting appropriate tools, researchers should consider factors including algorithm diversity, scalability for high-dimensional biological data, interoperability with existing bioinformatics pipelines, and support for multiobjective optimization scenarios common in therapeutic development. The integration of these frameworks with specialized biological simulation platforms extends their utility for drug development applications, enabling more efficient exploration of complex biological design spaces.

Why Systems Biology Poses Unique Challenges for Optimization

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, focusing on the complex, nonlinear interactions within biological systems rather than studying components in isolation. This interdisciplinary field integrates biology, medicine, engineering, computer science, chemistry, physics, and mathematics to comprehensively characterize biological entities by quantitatively integrating cellular and molecular information into predictive models [15]. Unlike traditional biological studies, systems biology seeks to understand how biological components—genes, proteins, metabolites—interact dynamically to give rise to cellular functions and behaviors. This systems-level perspective introduces profound challenges for optimization algorithms, which must navigate high-dimensional, noisy, and dynamically constrained spaces that characterize living organisms. The field's reliance on computational modeling to identify plausible mechanisms from numerous candidates [15] demands optimization approaches capable of handling biological complexity in ways that traditional engineering optimizations do not encounter.

Core Challenges in Optimizing Biological Systems

Multiscale System Integration and Dynamics

Biological systems operate across multiple scales, from molecular interactions to cellular networks and organism-level physiology. This multiscale nature creates significant optimization hurdles that are unique to biological contexts:

Multiscale, multirate, nonlinear dynamics: Cellular processes exhibit behaviors across different time and spatial scales, with nonlinear interactions that complicate prediction and optimization [16]. For instance, gene expression changes occur over seconds to minutes while phenotypic changes may manifest over hours or days.

Cross-scale dependency: Optimization at one biological scale (e.g., metabolic engineering) inevitably affects other scales (e.g., cellular growth rates), creating complex trade-offs that must be balanced [16].

Integration of heterogeneous data: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, fluxomic, and metabolomic data presents both conceptual and practical challenges due to the sheer volume and diversity of the data [15]. Each data type has different characteristics, noise profiles, and temporal resolutions.

Uncertainty and Biological Noise

Unlike engineered systems where parameters can be precisely controlled, biological systems exhibit inherent stochasticity that fundamentally limits optimization precision:

Intrinsic stochasticity: Random fluctuations in gene expression and reaction networks create biological noise that can lead to suboptimal and inconsistent bioprocess performance if not effectively addressed [16].

Extrinsic uncertainty: Environmental disturbances, measurement errors, and technological limitations contribute additional layers of uncertainty that optimization approaches must accommodate [16].

Partial observability: Biological systems are often partially observable, with many critical state variables impossible to measure directly in real time, requiring inference and estimation in optimization frameworks [16].

Computational Complexity and Model Specification

The mathematical representations of biological systems present distinctive computational challenges that strain conventional optimization approaches:

High-dimensional parameter spaces: Genome-scale metabolic models can contain thousands of reactions and metabolites, creating optimization landscapes with numerous local optima and complex topology [16].

Multi-objective trade-offs: Biological systems naturally balance competing objectives (e.g., growth vs. production, robustness vs. sensitivity), requiring Pareto optimization rather than single-objective approaches [16].

Model selection uncertainty: The choice between constraint-based (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis) and kinetic modeling approaches involves fundamental trade-offs between computational tractability and biological accuracy [16].

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Approaches

To illustrate the practical challenges of optimization in systems biology, we examine performance comparisons across different algorithmic approaches applied to biological problems. The following table summarizes key methodological considerations derived from benchmarking studies:

Table 1: Methodological Guidelines for Comparing Optimization Algorithms in Biological Contexts

| Guideline Category | Key Considerations | Common Pitfalls in Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Selection | Problem characteristics should represent biological reality; Avoid biases favoring particular algorithms [17] | Over-reliance on synthetic test functions; Benchmarks with optima near search space center [17] |

| Result Validation | Proper statistical analysis beyond raw data tables; Correct statistical test selection [17] | Using parametric tests without verifying assumptions; Insufficient replication for biological variability [17] |

| Algorithm Components | Analysis of individual component contributions; Parameter tuning specific to biological problems [17] | Neglecting to analyze exploration-exploitation balance; Inadequate complexity analysis [17] |

| Performance Measurement | Multiple complementary metrics; Computational resources accounting [18] | Inconsistent stopping criteria; Comparing algorithms run on different hardware [18] |

The challenges highlighted in Table 1 become particularly pronounced when applying bio-inspired optimization algorithms to biological problems. As noted in methodological guidelines for comparing such algorithms, "the chosen benchmarks frequently present some features that might favor algorithms with a particular bias" [17], which is especially problematic in biological contexts where the "true" optimization landscape is unknown and likely contains multiple biologically relevant solutions.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO) Variants on Benchmark Problems

| BBO Variant | Convergence Speed | Solution Quality | Application Context | Key Limitations in Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Migration BBO | Slower | Higher performance on complex problems | Better suited for high-dimensional, complex biological problems [19] | Computational intensity for multiscale models |

| Simplified Partial Migration BBO | Variable (depends on problem size) | Competitive on smaller problems | Effective when population size and problem dimensions are limited [19] | Performance degrades with biological complexity |

| Single Migration BBO | Faster | Reduced performance | Limited utility for biological problems [19] | Oversimplifies biological migration dynamics |

| Simplified Single Migration BBO | Fastest | Lowest performance | Minimal application to biological systems [19] | Insufficient for capturing biological complexity |

The performance trade-offs evident in Table 2 reflect fundamental challenges in applying optimization algorithms to biological systems. No single approach consistently outperforms others across all biological contexts, necessitating careful algorithm selection based on specific problem characteristics.

Experimental Framework for Systems Biology Optimization

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

To ensure fair comparison of optimization algorithms in systems biology contexts, researchers should adopt rigorous experimental frameworks:

Problem Formulation: Clearly define biological optimization problems with precise specification of decision variables, constraints, and objective functions derived from biological knowledge [17].

Experimental Design: Implement multiple independent runs with different initial conditions to account for algorithmic stochasticity and biological variability [17].

Performance Assessment: Apply appropriate statistical tests and visualization techniques to compare algorithm performance across biologically relevant metrics [17].

Resource Monitoring: Track computational resources (CPU time, memory usage) consistently, as "comparing optimization algorithms requires the same computational resources to be assigned to each algorithm" [18].

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for evaluating optimization algorithms in systems biology contexts:

Multi-omics Data Integration Workflow

Modern systems biology relies heavily on multi-omics data integration, which introduces specific optimization challenges throughout the analytical pipeline:

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental and computational workflow in systems biology optimization relies on specialized tools and methodologies. The following table outlines key resources mentioned in recent studies:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Optimization Pipeline | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | Multiple imaging platforms compared in [20] | Generate high-dimensional spatial gene expression data for model constraints | Tissue-level organization studies [20] |

| DNA Foundation Models | OmniReg-GPT [20] | Analyze multi-scale regulatory features across long DNA sequences | Genomic sequence understanding [20] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Tools | PB-TRIBE-STAMP, LSM14A-TRIBE-ID [20] | Characterize dynamic RNA composition of processing bodies | RNA metabolism studies [20] |

| Differentiable Simulators | JAXLEY [21] | Enable large-scale biophysical neuron model optimization through automatic differentiation | Neural computation modeling [21] |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Tools | Genome-scale metabolic models [16] | Provide stoichiometric constraints for flux optimization | Metabolic engineering [16] |

Systems biology presents a unique set of challenges for optimization algorithms that stem from the fundamental properties of biological systems—their multiscale organization, inherent stochasticity, nonlinear dynamics, and overwhelming complexity. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that no single optimization approach consistently outperforms others across all biological contexts. Instead, algorithm selection must be carefully matched to specific problem characteristics, considering the trade-offs between computational efficiency, biological accuracy, and practical implementability.

Future advances will likely come from hybrid approaches that combine mechanistic modeling with machine learning, enhanced by improved experimental technologies that generate more comprehensive datasets. As systems biology continues to evolve toward whole-cell modeling and digital twin technology [16], optimization methods must similarly advance to handle the increasing complexity of biological simulations. The field requires ongoing development of specialized optimization frameworks that respect biological principles while delivering computationally tractable solutions to guide biological discovery and engineering.

In the field of systems biology, optimizing complex models is fundamental to understanding cellular signaling pathways, metabolic networks, and drug responses. The effectiveness of this optimization hinges on three core concepts: the structure of fitness landscapes, the challenge of navigating between local and global optima, and the careful definition of objective functions. These concepts are not merely abstract mathematical ideas; they directly influence the reliability and biological relevance of computational models used in drug development and basic research. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different optimization algorithms perform within this framework, supported by experimental data from relevant studies.

Understanding the Evolutionary Metaphor: Fitness Landscapes and Seascapes

The concept of a fitness landscape, introduced by Sewall Wright in 1932, serves as a powerful metaphor for visualizing the relationship between genotypes (or, by extension, model parameters) and reproductive success (or model performance) [22]. In this model, every possible genotype is mapped to a location in a spatial coordinate system, and its fitness is represented as the height at that point [22].

- Landscape Topography: The structure of a fitness landscape is characterized by peaks (local or global optima), valleys (low-fitness regions), and ridges (neutral paths). A "rugged" landscape, with many local peaks surrounded by deep valleys, presents a significant challenge for optimization algorithms, as it is easy for a search to become trapped at a suboptimal point [22].

- The High-Dimensionality Challenge: While it is intuitive to visualize these landscapes as two- or three-dimensional mountain ranges, the genotypic spaces in biology are typically high-dimensional. This high dimensionality means that our low-dimensional intuitions can be misleading, as isolated fitness peaks are less common than a complex network of high-fitness ridges that connect genotypes [23].

- From Landscapes to Seascapes: A critical limitation of the classic fitness landscape is its static nature. In reality, biological environments are dynamic. The concept of a fitness seascape addresses this by allowing the adaptive topography—the heights of peaks and depths of valleys—to shift over time due to factors like environmental change, drug exposure, or immune surveillance [22]. This is crucial for accurately modeling processes like antibiotic resistance or cancer evolution in response to therapy [22].

The Optimization Challenge: Local vs. Global Optima

In optimization, the goal is to find the parameter set that yields the best possible value for an objective function. This search is complicated by the existence of multiple optima.

- Local Optima are points where the objective value is better than at all other nearby points, but potentially worse than a distant point in the parameter space. Gradient-based solvers typically converge to a local minimum [24] [25].

- Global Optima are the best possible solutions across the entire feasible parameter space [24] [25].

The figure below illustrates this relationship and the core workflow for comparing optimization algorithms in a biological context.

Figure 1: The challenge of optimization in a complex fitness landscape. Algorithms must navigate local optima (red) to find the global optimum (green), following a workflow from problem definition to biological insight.

Algorithms can be characterized by their approach to this problem:

- Local Solvers: Gradient-based algorithms (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) efficiently find local optima but are highly sensitive to the starting point and may miss the global solution [24] [25].

- Global Solvers: Techniques like Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), and Bayesian Optimization (BO) incorporate strategies to explore the wider parameter space and are less likely to be trapped by local optima [26].

Defining the Goal: Objective Functions in Systems Biology

The objective function (or fitness function) quantifies how well a model with a given parameter set explains experimental data. Its definition is a critical step that directly impacts parameter identifiability and optimization performance [27].

Two common approaches for aligning model simulations with experimental data are:

- Scaling Factors (SF): This method introduces unknown parameters that scale the model output to the scale of the data. While common, it increases the number of parameters and can aggravate non-identifiability [27].

- Data-Driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS): This approach normalizes both the simulated and experimental data in the same way (e.g., dividing by a reference value like the maximum data point). DNS does not introduce new parameters and has been shown to improve optimization speed and reduce non-identifiability, especially for models with a large number of parameters [27].

Another powerful framework is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), used extensively in metabolic network modeling. FBA relies on defining a biological objective—such as maximizing biomass production—as a linear function of reaction fluxes. Methods like the Biological Objective Solution Search (BOSS) have been developed to infer this objective function directly from experimental data, rather than assuming it a priori [28].

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms

To objectively compare performance, we examine experimental data from studies that benchmarked algorithms on biological and numerical problems.

Performance in Systems Biology Parameter Estimation

A 2017 study compared optimization algorithms and objective functions for parameter estimation in dynamic models of signaling pathways [27]. The tested algorithms were:

- LevMar SE: A gradient-based Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm using Sensitivity Equations for gradient calculation.

- LevMar FD: The same algorithm, but using Finite Differences for gradient calculation.

- GLSDC: A hybrid stochastic-deterministic Genetic Local Search algorithm with Distance independent Diversity Control.

The table below summarizes the key findings.

Table 1: Performance comparison of optimization algorithms on systems biology parameter estimation problems [27].

| Algorithm | Algorithm Type | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Performance on Large Models (74 params) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LevMar SE | Gradient-based (Local) | Fastest for smaller, convex problems [27] | Prone to getting trapped in local optima; performance depends on start point [27] [24] | Outperformed by GLSDC [27] |

| LevMar FD | Gradient-based (Local) | More stable than SE for some problems [27] | Computationally expensive for large models [27] | Not the best performing [27] |

| GLSDC | Hybrid Stochastic-Deterministic (Global) | Best performance for large-scale problems; effective at avoiding local optima [27] | Slower convergence on smaller problems [27] | Best performance and efficiency [27] |

The study concluded that for models with a large number of parameters (e.g., 74), the hybrid GLSDC algorithm performed best. It also found that using DNS instead of SF consistently improved the convergence speed of all algorithms and did not aggravate non-identifiability [27].

Performance in a General Engineering Context

A 2023 benchmark on a Finite Element Model Updating (FEMU) problem provides a useful comparison of global optimizers [26]. This study compared:

- Generalized Pattern Search (GPS): A direct-search method.

- Simulated Annealing (SA): A physics-inspired heuristic.

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): A population-based evolutionary algorithm.

- Bayesian Sampling Optimization (BO): A model-based efficient global optimizer.

Table 2: Results of optimization algorithm benchmarking on a structural engineering problem [26].

| Algorithm | Computational Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Remarks on Algorithm Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Pattern Search (GPS) | Moderate | Moderate | Simple, direct search; less sophisticated [26] |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) | High | Lower | Effective for rugged landscapes; sensitive to cooling schedule [26] |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | High | Lower | Good for complex spaces; can be computationally expensive [26] |

| Bayesian Sampling (BO) | High | High (~50% faster) | Powerful efficiency for "expensive" functions; balances exploration/exploitation [26] |

The study found that Bayesian Optimization achieved high accuracy with a runtime approximately half that of the other strategies, demonstrating a superior balance between exploration and exploitation [26].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table lists key software and methodological "reagents" used in the featured experiments, which are essential for researchers building similar optimization workflows.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization in Systems Biology.

| Research Reagent | Function / Description | Relevance to Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| PEPSSBI [27] | Software platform that fully supports Data-driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS). | Addresses scaling issues in data, improving identifiability and convergence [27]. |

| Sensitivity Equations (SE) [27] | A method for computing the gradient of the objective function with respect to parameters. | Enables efficient gradient-based optimization (e.g., LevMar SE); faster than finite differences [27]. |

| Global Optimization Toolbox [24] | A software library (e.g., in MATLAB) containing global solvers like GlobalSearch and MultiStart. |

Automates the process of running local solvers from multiple start points to find a global solution [24]. |

| Bayesian Sampling Optimization [26] | A model-based global optimization technique that builds a probabilistic model of the objective function. | Highly efficient for computationally expensive problems, offering a good speed/accuracy trade-off [26]. |

| BOSS Framework [28] | Biological Objective Solution Search; infers a system's objective function from flux data. | Discovers de novo objective reactions for metabolic networks, extending biological relevance [28]. |

Integrated Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The diagram below outlines a detailed protocol for a comparative optimization study, integrating the concepts of objective functions, algorithms, and validation.

Figure 2: A detailed workflow for conducting a comparative analysis of optimization algorithms, from initial problem setup to final validation and conclusion.

Key Methodological Details:

- Model Formulation: Use ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to capture the nonlinear dynamics of signaling pathways. The model takes the form ( \frac{d}{dt}x = f(x,\theta) ), where ( x ) is the state vector and ( \theta ) represents the kinetic parameters to be estimated [27].

- Performance Metrics: When comparing algorithms, measure both the final objective value (quality of fit) and the computation time. Relying solely on the number of function evaluations can be misleading when algorithms like LevMar SE use expensive gradient calculations [27].

- Handling Non-Identifiability: If parameters are not uniquely determined by the data (non-identifiability), consider model reduction or collecting additional experimental data measuring different variables [27].

The choice of an optimization algorithm in systems biology is not one-size-fits-all. For smaller, well-behaved problems, gradient-based methods like LevMar SE offer speed. However, for the large, complex, and often non-convex models that are characteristic of modern systems biology, global or hybrid strategies like GLSDC or Bayesian Optimization demonstrate superior performance in escaping local optima and finding a globally satisfactory solution. Furthermore, methodological choices such as employing Data-driven Normalization (DNS) over Scaling Factors can significantly enhance optimization efficiency and robustness. By understanding the structure of fitness landscapes, the pitfalls of local optima, and the impact of the objective function, researchers can make informed decisions to improve the reliability and predictive power of their biological models.

From Theory to Practice: Applying Optimization Algorithms to Biological Models

Parameter Estimation in Complex Kinetic Models of Metabolism

Kinetic models are essential tools in systems biology for quantitatively understanding and predicting the dynamic behavior of metabolic networks. These models typically consist of systems of ordinary differential equations that describe the rates of biochemical reactions as functions of metabolite concentrations and enzyme activities. A fundamental challenge in developing such models is parameter estimation—the process of determining the unknown kinetic parameters (e.g., Michaelis constants, catalytic rates, allosteric regulation coefficients) from experimental data. This process is formally structured as an optimization problem where the goal is to minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental measurements, often using a weighted sum-of-squares objective function [29].

Parameter estimation in kinetic models of metabolism presents several unique challenges. The models are typically nonlinear, highly parameterized, and characterized by complex interactions between parameters. Furthermore, experimental data used for calibration are often noisy and limited in scope, leading to issues with parameter identifiability where multiple parameter combinations can explain the available data equally well [29] [30]. The field has responded by developing and adapting diverse optimization algorithms, each with distinct strengths and limitations for addressing these challenges in biological contexts.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of prominent optimization algorithms used for parameter estimation in kinetic models of metabolism, supported by experimental data and implementation protocols. We focus specifically on approaches relevant to drug development and metabolic engineering applications, where accurate parameter estimation is crucial for predicting cellular behavior under perturbation.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms

Algorithm Classification and Characteristics

Optimization algorithms for parameter estimation in kinetic models can be broadly categorized into three main strategies: deterministic, stochastic, and heuristic methods [31]. Deterministic methods like least-squares approaches use precise mathematical rules to navigate parameter space. Stochastic methods incorporate randomness in the search process, enabling escape from local minima. Heuristic methods, often inspired by natural processes, employ practical strategies that may not guarantee optimality but work well on complex problems.

Table 1: Classification of Optimization Algorithms for Kinetic Modeling

| Algorithm Type | Representative Methods | Key Characteristics | Metabolic Modeling Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic | Multi-start nonlinear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) | Gradient-based; requires smooth objective functions; converges quickly to local minima | Fitting ODE models to metabolite time-course data [31] |

| Stochastic | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Probabilistic sampling; provides uncertainty quantification; computationally intensive | Bayesian parameter estimation; handling stochastic models [31] [30] |

| Heuristic | Genetic Algorithms (GA), Evolutionary Strategies | Population-based; inspired by natural evolution; global search capability | Large-scale model calibration; kinetic flux profiling [31] [32] |

| Hybrid | eSS + NL2SOL | Combines global exploration with local refinement; balances efficiency and robustness | Large-scale kinetic models with many parameters [29] |

Performance Comparison of Key Algorithms

Different optimization algorithms exhibit varying performance characteristics depending on the properties of the kinetic model and available data. The table below summarizes quantitative comparisons based on studies evaluating parameter estimation for metabolic pathways.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms for Metabolic Models

| Algorithm | Convergence Guarantees | Parameter Support | Computational Efficiency | Uncertainty Quantification | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-start nLLSQ | Local convergence only [31] | Continuous parameters only [31] | High for small to medium problems [31] | Limited (frequentist confidence intervals) | Low to moderate [31] |

| MCMC | Global convergence under specific conditions [31] | Continuous and discrete parameters [31] | Low (many function evaluations required) [30] | Excellent (full posterior distributions) [30] | High [30] |

| Genetic Algorithms | No theoretical guarantees for continuous problems [31] | Continuous and discrete parameters [31] | Moderate to low (population-based) [31] | Limited (multiple runs required) | Moderate [31] |

| RENAISSANCE (NES) | Not specified | Continuous parameters primarily | High (machine learning-accelerated) [32] | Built-in parameter distribution estimation [32] | High (specialized framework) [32] |

| ABC Sampling | Asymptotic approximate posterior [30] | Complex parameter constraints supported [30] | Low to moderate (likelihood-free) [30] | Good (approximate posterior distributions) [30] | High [30] |

The multi-start nonlinear least squares approach is particularly effective for problems with continuous parameters and relatively smooth objective functions, with the advantage of faster convergence compared to stochastic methods [31]. However, its tendency to converge to local minima makes it less suitable for problems with multiple feasible parameter regions. In contrast, Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods excel at quantifying parameter uncertainty and handling complex, multi-modal posterior distributions, making them valuable for modeling metabolic pathways where parameters are poorly constrained by data [30]. The computational burden of MCMC can be prohibitive for very large models.

Genetic Algorithms and other evolutionary strategies provide robust global search capabilities without requiring gradient information, making them suitable for problems with discrete parameters or non-smooth objective functions [31]. More recently, machine learning frameworks like RENAISSANCE (using Natural Evolution Strategies) have demonstrated high efficiency in generating large-scale kinetic models for metabolic networks, significantly reducing computation time compared to traditional approaches [32].

Diagram 1: Parameter Estimation Workflow in Kinetic Modeling. The process involves iterative evaluation and convergence checks, with algorithm selection dependent on problem characteristics.

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Bayesian Parameter Estimation for the Methionine Cycle

Background and Objective: The mammalian methionine cycle represents a tightly regulated metabolic pathway linking trans-methylation and trans-sulphuration reactions. Abnormal operation of this cycle is associated with cardiovascular disease, neural tube defects, and cancer [30]. This case study employed Approximate Bayesian Computation to estimate parameters for a detailed kinetic model of this pathway, addressing challenges of parameter identifiability and thermodynamic feasibility.

Experimental Protocol:

- Reference Data Collection: Assembled biochemical data, structural information, reference flux distributions, and Gibbs free energies of reaction for the methionine cycle

- Prior Distribution Specification: Used the General Reaction Assembly and Sampling Platform to generate thermodynamically feasible kinetic parameters as prior distributions

- ABC Sampling: Implemented a rejection sampler that:

- Proposed parameters from the prior distribution

- Simulated data from the model conditional on those parameters

- Accepted parameters that simulated data within tolerance of observed values

- Convergence Assessment: Evaluated posterior distributions after incorporating 12 simulated metabolic perturbations

Key Results: The ABC framework successfully generated thermodynamically feasible parameter samples that converged on true values, with the second perturbation (50% increase in influx rate) providing the most information for parameter estimation [30]. The method demonstrated remarkable prediction accuracy in validation tests and enabled appraisal of system properties and key metabolic regulations.

Kinetic Flux Profiling for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Background and Objective: Kinetic Flux Profiling is a method for estimating metabolic fluxes that utilizes data from isotope tracing experiments [33]. Unlike constraint-based methods that assume steady-state labeling patterns, KFP leverages the dynamics of changing isotope labeling to better determine network fluxes.

Experimental Protocol:

- Isotope Labeling: Cells at metabolic steady state in unlabeled media are switched to stable-isotope-labeled media (e.g., ¹³C-labeled nutrients)

- Time-Course Sampling: Samples are collected at multiple time points without disrupting metabolic steady state

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Proportions of labeled and unlabeled metabolites are quantified using MS or NMR

- ODE Model Construction: Convert metabolic pathway diagram to system of ordinary differential equations describing isotope labeling dynamics

- Parameter Fitting: Use optimization algorithms to estimate metabolic flux parameters that best fit isotope labeling time courses

Key Results: Bayesian parameter estimation on simulated KFP data demonstrated accurate flux estimation for pathways containing both irreversible and reversible reactions [33]. The analysis provided guidelines for experimental design, establishing that relative fluxes can be estimated without metabolite concentration measurements, but absolute flux determination requires concentration data.

Diagram 2: Kinetic Flux Profiling Workflow. This method combines isotope tracing experiments with computational modeling to estimate metabolic fluxes.

RENAISSANCE Framework for Large-Scale Model Generation

Background and Objective: Traditional kinetic modeling approaches face challenges with large-scale applications due to long computing times and extensive data requirements. The RENAISSANCE framework addresses these limitations using generative machine learning to efficiently parameterize large-scale kinetic models [32].

Experimental Protocol:

- Candidate Generation: Create population of candidate model parameterizations

- Fitness Evaluation: Score each candidate based on consistency with experimental observations

- Natural Evolution Strategies: Apply NES to evolve parameter distributions toward improved fitness

- Model Validation: Assess dynamic stability and consistency with known experimental results

- Data Integration: Incorporate available experimental kinetic parameters from databases

Key Results: Application to E. coli metabolism demonstrated high success rates in generating models consistent with experimental growth data [32]. The framework significantly reduced parameter uncertainty and improved estimation accuracy, particularly when integrating sparse experimental data.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Kinetic Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Parameter Estimation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotope Tracers | ¹³C-labeled nutrients (e.g., ¹³C-glucose) | Enable tracking of metabolic fluxes through pathways via mass isotopomer distributions | Kinetic Flux Profiling; MFA [33] |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS, NMR | Quantify metabolite concentrations and isotope labeling patterns | Data generation for model calibration [33] |

| Modeling Environments | MATLAB, Python (SciPy), R | Provide optimization algorithms and ODE solvers for model simulation | General parameter estimation [29] |

| Specialized Software | VisId Toolbox, GRASP Platform | Perform identifiability analysis and sample thermodynamically feasible parameters | Identifiability assessment; Bayesian inference [29] [30] |

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Provide prior information on kinetic parameters from published studies | Bayesian prior specification [32] [30] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | RENAISSANCE | Generate kinetic models using natural evolution strategies | Large-scale model construction [32] |

Parameter estimation in complex kinetic models of metabolism remains a challenging but essential task in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Our comparative analysis demonstrates that algorithm selection must be guided by specific problem characteristics, including model size, parameter identifiability, data quality and quantity, and computational resources. While local optimization methods like multi-start least squares offer efficiency for well-behaved problems, global methods such as MCMC and evolutionary algorithms provide more robust solutions for complex, multi-modal problems.

Future developments in the field are likely to focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple algorithms, such as using global methods for initial exploration followed by local refinement [29]. Machine learning frameworks like RENAISSANCE show promise for accelerating large-scale model generation, potentially making kinetic modeling more accessible for applications in drug development and personalized medicine [32]. Additionally, improved experimental design methodologies that maximize information content for parameter estimation will help address fundamental identifiability challenges [29].

As kinetic models continue to grow in scale and complexity, advancing our capabilities for robust and efficient parameter estimation will be crucial for realizing their potential in predicting metabolic behavior and designing therapeutic interventions.

Model Tuning and Biomarker Identification Applications

In computational systems biology, optimization algorithms are fundamental for extracting meaningful biological insights from complex datasets. These algorithms are primarily applied to two critical tasks: model tuning, which involves estimating unknown parameters in biological models to accurately reflect observed data, and biomarker identification, the process of discovering molecular features that diagnose diseases, predict outcomes, or indicate treatment responses [31]. The overarching goal is to solve global optimization problems, finding the best possible solution according to a defined objective function, rather than settling for locally optimal solutions [31]. The application of these methods is transforming personalized medicine, enabling the development of therapies targeted to patient subgroups based on their individual molecular features [34].

The optimization problem in this field can be formally defined as minimizing a cost function, c(θ), subject to constraints, where θ represents the parameters being estimated [31]. These parameters could be rate constants in a biological model or the selection of genes for a biomarker panel. The challenges are significant: objective functions are often non-linear and non-convex, leading to multiple potential solutions, and the high dimensionality of omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) further complicates the optimization landscape [31]. This comparative analysis examines the performance of prominent optimization algorithms applied to these challenges, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for method selection.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms

Algorithm Performance and Characteristics

Optimization approaches in systems biology can be broadly categorized into deterministic, stochastic, and heuristic methodologies. The table below compares the core characteristics of three widely used algorithms.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Featured Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Optimization Strategy | Core Application Strength | Parameter Type Support | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-start non-linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) [31] | Deterministic | Model tuning for continuous parameters | Continuous | Fast local convergence; proven convergence under specific hypotheses |

| Random Walk Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) [31] | Stochastic | Model tuning involving stochastic equations/simulations | Continuous | Handles non-convex, complex objective functions; global search capability |

| Simple Genetic Algorithm (sGA) [31] | Heuristic | Biomarker identification; high-dimensional feature selection | Continuous & Discrete | Robust global search; less prone to being trapped in local minima |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The following table synthesizes quantitative performance data from recent studies that applied these and other related algorithms to specific biological problems, including biomarker discovery and model tuning.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Biological Applications

| Application Context | Algorithm Used | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicting Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) [35] | Logistic Regression (LR) with feature selection | AUC: 0.92 (with 62 features) | Outperformed SVM, Decision Tree, RF, XGBoost in this study |

| Multi-Cancer Detection [36] | Random Forest (RF) on exosomal RNA | Pan-cancer vs control AUC: 0.915; Tumor origin classification AUC: 0.853-0.980 | Demonstrated high accuracy for a complex multi-class problem |

| Subgroup Identification & Predictive Biomarkers [37] | DeepRAB (Deep Learning) | Superior performance in simulation studies vs. Meta-learning, Q-learning, D-learning | Effectively captured complex biomarker-causal effect relationships |

| Feature Importance Testing [38] | PermFIT (with DNN, RF, SVM) | Valid statistical inference for feature importance; improved prediction accuracy | Outperformed SHAP, LIME, HRT, and SNGM in numerical studies |

| Model Tuning (Prey-Predator Model) [31] | ms-nlLSQ, rw-MCMC, sGA | Accurate parameter estimation for ODEs from noisy data | All methods achieved plausible fits; performance depended on data characteristics |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Protocol for Biomarker Discovery in Disease Prediction

The study predicting Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) exemplifies a robust protocol for biomarker discovery [35]. The workflow began with participant recruitment and plasma sample collection from LAA patients and normal controls, followed by metabolite quantification using the targeted Absolute IDQ p180 kit (Biocrates Life Sciences). This kit quantifies 194 endogenous metabolites. After data pre-processing (missing value imputation, label encoding), the dataset was split, with 80% used for model training and validation (10-fold cross-validation) and 20% held back for external testing. Six machine learning models—Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree, Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Gradient Boosting—were trained on three feature scales: clinical factors alone, metabolites alone, and their combination. Model performance was evaluated using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) on the external validation set. The study further identified a set of 27 shared features that appeared across multiple models, which when used in the top-performing LR model, achieved an AUC of 0.93 [35].

Protocol for Multi-Cancer Detection Biomarker Development

A multi-phase, multi-center study established a protocol for developing a multi-cancer diagnostic test based on blood-derived exosomal RNA (exoRNA) [36]. The discovery phase involved RNA sequencing of exosomes from 818 participants across eight cancer types to identify 33 candidate biomarkers. In the screening phase, these candidates were refined using TaqMan qPCR analysis on samples from 245 participants across nine independent centers, excluding 13 biomarkers with insufficient detection reliability. The validation phase further refined the biomarker panel using an expanded cohort of 1,385 participants, resulting in a final set of 12 exosomal tumor RNA signatures (ETR.sig). In the final model construction phase, a Random Forest algorithm was trained on the ETR.sig data to build two diagnostic models: one for distinguishing cancer from controls and another for classifying the tumor tissue of origin. Model performance was rigorously assessed using AUC values for both binary and multi-class classification tasks [36].

Protocol for Model Tuning with Optimization Algorithms

A reviewed study on optimization algorithms provides a general protocol for model tuning, demonstrated on the classic Lotka-Volterra (prey-predator) model [31]. The process starts by defining the objective function, which is often a least squares function measuring the difference between experimental data (e.g., population counts over time) and model simulations. The next step is to define the search space and constraints for the parameters (e.g., growth and death rates must be positive). The chosen optimization algorithm—ms-nlLSQ, rw-MCMC, or sGA—is then executed. For ms-nlLSQ, this involves running a local least-squares solver from multiple starting points. For rw-MCMC, a Markov chain explores the parameter space by probabilistically accepting or rejecting new parameter sets. For sGA, a population of parameter sets is iteratively evolved through selection, crossover, and mutation. The output is the set of parameter estimates that minimize the objective function, which can then be used to run simulations and validate the model against unseen data [31].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Biomarker Discovery and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the multi-phase, multi-center workflow used for developing and validating a multi-cancer diagnostic test, a protocol that can be adapted for various biomarker discovery projects [36].

Diagram 1: Multi-phase biomarker discovery and validation workflow.

Optimization Algorithm Selection Logic

Choosing the correct optimization algorithm depends on the problem's nature, including the types of parameters and the objective function's characteristics. The following decision diagram guides this selection process for applications in systems biology [31].

Diagram 2: Optimization algorithm selection logic.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Platforms

The experimental protocols and studies referenced rely on a suite of essential reagents, software platforms, and analytical tools. This table details key solutions that form the foundation of modern, computation-driven biomarker discovery and model tuning.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Computational Biology

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute IDQ p180 Kit [35] | Targeted Metabolomics Assay | Quantifies 194 endogenous metabolites from plasma/serum samples for biomarker discovery. | Identifying metabolite biomarkers for Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) [35]. |

| Biocrates MetIDQ Software [35] | Data Analysis Software | Processes raw mass spectrometry data from the p180 kit to output quantified metabolite concentrations. | Data pre-processing for machine learning models predicting LAA [35]. |

| TaqMan qPCR [36] | Molecular Biology Assay | Validates and refines candidate biomarkers from discovery phases with high sensitivity and specificity. | Screening and validating exosomal RNA biomarkers in a multi-center study [36]. |

| exoRbase Database [36] | Public Data Repository | A database of exosomal RNA-seq data from various cancers and healthy controls for discovery analysis. | Sourcing exoRNA-seq data for multiple cancer types during the discovery phase [36]. |

| Omics Playground [39] | Integrated Analysis Platform | Provides a user-friendly interface with multiple built-in machine learning and statistical algorithms for biomarker analysis. | Enabling biomarker discovery from transcriptomic and proteomic data without requiring coding skills [39]. |

| PermFIT [38] | Computational Algorithm | A permutation-based feature importance test that provides valid statistical inference for complex models (DNN, RF, SVM). | Identifying important protein biomarkers in TCGA kidney tumor data [38]. |

| DeepRAB [37] | Deep Learning Framework | A DNN architecture designed for subgroup identification and predictive biomarker discovery by estimating individualized treatment rules. | Identifying patient subgroups with enhanced response to Humira in hidradenitis suppurativa [37]. |

The comparative analysis of optimization algorithms for model tuning and biomarker identification reveals a landscape where no single algorithm universally dominates. Instead, the optimal choice is highly dependent on the specific problem context, data characteristics, and desired outcome. Traditional statistical methods and Logistic Regression continue to demonstrate strong performance, particularly for prognostic tasks where interpretability is key [35] [40]. However, for problems involving complex, non-linear relationships and high-dimensional data, such as identifying predictive biomarkers for treatment response, more advanced machine learning and deep learning approaches like Random Forest, XGBoost, and specialized frameworks (DeepRAB, PermFIT) show superior performance [37] [36] [38]. The integration of multiple methods, combined with rigorous multi-phase validation protocols, emerges as a powerful strategy for developing robust, clinically relevant biomarkers and accurately tuned biological models. Future advancements will likely focus on enhancing the interpretability of complex models, improving methods for data integration from multiple omics layers, and standardizing validation workflows to accelerate the translation of computational discoveries into clinical applications.

Optimization algorithms have become indispensable in computational systems biology, enabling researchers to decipher the complex design principles of metabolic-genetic networks [3] [31]. These mathematical frameworks allow for in-silico simulation of biological phenomena, providing mechanistic insights into cellular processes by estimating unknown model parameters, classifying biological samples, and identifying key regulatory patterns [31]. The fundamental challenge in biological optimization lies in navigating high-dimensional, non-linear solution spaces with multiple local optima, where traditional analytical approaches often fail [3] [31]. This case study examines the application of diverse optimization methodologies to two critical biological problems: enhancing hydrogen production in cyanobacterial metabolic networks and understanding evolutionary tradeoffs in glycolytic pathway strategies. By comparing algorithm performance across these distinct biological contexts, we aim to establish guidelines for selecting appropriate optimization techniques based on problem characteristics, data availability, and computational constraints within systems biology research.

Optimization Algorithms in Systems Biology: A Comparative Framework

Algorithm Classification and Selection Criteria

Optimization problems in computational systems biology can be formulated as minimizing or maximizing an objective function subject to constraints, where θ represents parameter estimates, c(θ) is the cost function, and g(θ), h(θ) represent inequality and equality constraints respectively [31]. Biological optimization problems frequently exhibit multimodality, non-linearity, and parameter uncertainty, necessitating sophisticated global optimization approaches [3].

Table 1: Classification of Optimization Algorithms in Systems Biology

| Algorithm Type | Mathematical Foundation | Biological Applications | Convergence Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-start Nonlinear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) | Deterministic, Gauss-Newton method | Parameter estimation in ODE models, continuous variables | Proven local convergence under specific conditions |

| Random Walk Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) | Stochastic sampling, Bayesian inference | Stochastic model tuning, uncertainty quantification | Proven global convergence, probabilistic guarantees |

| Simple Genetic Algorithm (sGA) | Heuristic, evolutionary computation | Biomarker identification, mixed continuous-discrete problems | Convergence proven only for discrete parameters |

Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

The three prominent optimization methodologies exhibit distinct computational characteristics and performance profiles. ms-nlLSQ is suitable only for continuous parameters and objective functions, while rw-MCMC supports both continuous and non-continuous objective functions. sGA provides the greatest flexibility, supporting both continuous and discrete parameters [31]. Computational requirements also vary significantly, with ms-nlLSQ and sGA requiring multiple function evaluations per iteration compared to just one evaluation for rw-MCMC. Implementation complexity ranges from moderate for ms-nlLSQ to high for rw-MCMC due to its statistical foundations [31].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Parameter Support | Function Evaluations per Iteration | Implementation Complexity | Best-Suited Biological Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms-nlLSQ | Continuous only | Multiple | Moderate | Model tuning with ODE/PDE systems |

| rw-MCMC | Continuous parameters, continuous/non-continuous functions | Single | High | Stochastic models, uncertainty analysis |

| sGA | Continuous and discrete parameters | Multiple | Low to Moderate | Feature selection, biomarker identification |

Case Study 1: Metabolic Engineering of Cyanobacterial Hydrogen Production

Experimental Protocol and Optimization Framework

Recent research has demonstrated the potential of cyanobacteria as biological platforms for sustainable hydrogen production through metabolic and genetic optimization [41]. The experimental protocol evaluated four cyanobacterial species under varying conditions, partially inhibiting photosynthesis using chemical inhibitors including 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU), and introducing exogenous glycerol as a supplementary carbon source [41]. Hydrogen production was monitored over time, with rates normalized to chlorophyll a content, while genomic analysis identified transporter proteins with putative roles in carbon uptake and hydrogen metabolism.

The optimization objective was to maximize hydrogen yield through strategic manipulation of metabolic pathways. Cyanobacteria employ two principal pathways for H₂ production: the Hox hydrogenase pathway, where the Hox enzyme complex catalyzes hydrogen evolution by accepting electrons from reduced NADPH, and the nitrogenase-dependent pathway in nitrogen-fixing species, where nitrogenase facilitates H₂ evolution under anaerobic conditions within specialized heterocysts [41]. The optimization challenge involved balancing electron flow between competing pathways, including the respiratory electron transport chain and carbon fixation via the Calvin cycle [41].

Optimization Results and Performance Metrics

The metabolic optimization yielded substantial improvements in hydrogen production. Nitrogen-fixing Dolichospermum sp. exhibited significantly higher hydrogen production compared to other tested species, with glycerol supplementation notably increasing both the rate and duration of hydrogen evolution [41]. The maximum hydrogen production rate for Dolichospermum sp. reached 132.3 μmol H₂/mg Chl a/h, representing a 30-fold enhancement over rates observed with DCMU alone. The hydrogen release process was extended to 46 days, with up to 67% H₂ in the gas phase obtained for Dolichospermum sp. IPPAS B-1213 [41].

Table 3: Hydrogen Production Optimization Results

| Cyanobacterial Species | Baseline H₂ Production (μmol/mg Chl a/h) | Optimized H₂ Production (μmol/mg Chl a/h) | Fold Improvement | Key Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolichospermum sp. | 4.41 | 132.3 | 30.0 | Glycerol supplementation + metabolic engineering |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Data not specified | Data not specified | Significant | DCMU inhibition + genetic modifications |

| Other Tested Species | Data not specified | Data not specified | Moderate | Various pathway optimizations |

The experimental results underscore the potential of combined metabolic engineering and optimization algorithms for enhancing biohydrogen production. Genomic screening revealed key transporter proteins with putative roles in carbon uptake and hydrogen metabolism, providing targets for future genetic optimization efforts [41].

Case Study 2: Glycolytic Pathway Optimization and Evolutionary Tradeoffs

Experimental Framework for Glycolytic Strategy Analysis

Contrary to textbook portrayals of glycolysis as a single conserved pathway, prokaryotic glucose metabolism demonstrates significant diversity, with the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway representing a common alternative to the canonical Embden-Meyerhoff-Parnass (EMP) pathway [42]. This case study applied optimization methods to analyze why organisms would employ the ED pathway despite its lower ATP yield (1 ATP per glucose versus 2 ATP in the EMP pathway).

The research introduced innovative methods for analyzing pathways in terms of thermodynamics and kinetics, evaluating the tradeoff between a pathway's energy (ATP) yield and the amount of enzymatic protein required to catalyze pathway flux [42]. Optimization algorithms were employed to identify Pareto-optimal solutions that balance these competing objectives across different environmental conditions.

Optimization Results and Biological Significance

The application of optimization algorithms revealed that the ED pathway requires several-fold less enzymatic protein to achieve the same glucose conversion rate as the EMP pathway [42]. This fundamental tradeoff between efficiency and resource investment explains the diversity of glycolytic strategies across prokaryotes. Genomic analysis confirmed that energy-deprived anaerobes overwhelmingly rely on the higher ATP yield of the EMP pathway, while the ED pathway is common among facultative anaerobes and even more common among aerobes [42].

Table 4: Glycolytic Pathway Optimization Tradeoffs

| Organism Type | Preferred Pathway | ATP Yield (per glucose) | Relative Protein Cost | Environmental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|