Building the Blueprint: How Protein-Protein Interaction Networks Are Revealing Autism's Molecular Mechanisms

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the construction and application of Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) research.

Building the Blueprint: How Protein-Protein Interaction Networks Are Revealing Autism's Molecular Mechanisms

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the construction and application of Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) research. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of mapping the ASD interactome, from the critical importance of cell-type-specific and isoform-resolved networks to the advanced computational methods that prioritize novel risk genes. The article details methodological frameworks for network analysis, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and reviews rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing findings from recent seminal studies, this resource outlines how PPI networks are transforming our understanding of ASD's convergent biology and accelerating the path to therapeutic discovery.

Laying the Groundwork: Exploring the Architecture of the Autism Interactome

The Case for Cell-Type-Specific PPI Mapping in Human Neurons

The genetic architecture of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by daunting polygenicity, with current evidence implicating hundreds of susceptibility genes [1] [2]. This substantial heterogeneity has presented a significant challenge in identifying convergent, actionable biological pathways. Traditional protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks derived from non-neuronal cells or computational predictions have limited utility for understanding neurodevelopmental disorders, as they fail to capture the unique proteome and signaling environment of human neurons [3]. Cell-type-specific PPI mapping in human induced neurons represents a transformative approach that reveals biologically relevant networks distinct from those obtained from non-neuronal cells or model organisms, thereby accelerating the identification of meaningful therapeutic targets for ASD [4] [3].

Key Findings from Neuron-Specific PPI Studies

Recent advances in neuron-specific proteomics have enabled the systematic mapping of PPI networks for ASD risk genes, revealing convergent biological mechanisms and disease-relevant pathologies. These studies demonstrate that interactions observed in human neurons frequently differ from those documented in generic databases or non-neuronal cells, highlighting the critical importance of cellular context [3].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Cell-Type-Specific PPI Mapping

| Aspect | Traditional PPI Approaches | Neuron-Specific PPI Mapping |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Context | Non-neuronal cell lines (HEK293, HeLa) or computational predictions | Human induced excitatory neurons |

| Biological Relevance | Limited neuronal relevance | High relevance to neuronal function |

| Network Features | Static, generic interactions | Dynamic, spatially relevant interactions |

| Disease Insight | Identifies broad biological processes | Reveals convergent pathways in specific neuronal subtypes |

| Experimental Validation | Often requires follow-up in neuronal models | Directly relevant to neuronal biology |

Notably, a protein interaction study for 13 ASD-associated genes in human induced excitatory neurons revealed a network enriched for both genetic and transcriptional perturbations observed in individuals with ASD [3]. This network exhibited significant enrichment for additional ASD risk genes and differentially expressed genes from postmortem ASD brains, validating its disease relevance. Furthermore, clustering of risk genes based on their neuron-specific PPI networks identified gene groups corresponding to clinical behavior score severity, connecting molecular interactions to phenotypic manifestations [4].

Table 2: Convergent Pathways Identified through Neuron-Specific PPI Mapping

| Biological Pathway | ASD Risk Genes Involved | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial/Metabolic Processes | Multiple genes | Cellular energy production, neuronal function |

| Wnt Signaling | Various risk genes | Neurodevelopment, synaptic formation |

| MAPK Signaling | Several network components | Neuronal growth, differentiation |

| Synaptic Transmission | SHANK3, ANK2, others | Synaptic function, neuronal communication |

| IGF2BP1-3 Complex | Convergent point | Transcriptional regulation of ASD genes |

Experimental Protocols for Neuron-Specific PPI Mapping

Proximity-Dependent Biotinylation in Human Induced Neurons

Proximity-dependent biotinylation methods, such as BioID2, enable the mapping of PPIs under near-physiological conditions in human neurons [4]. The following protocol details the implementation for ASD risk gene products:

Workflow:

- Neuronal Differentiation: Generate excitatory neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using established differentiation protocols (typically 4-6 weeks).

- Viral Transduction: Lentivirally transduce neurons with bait proteins (ASD risk genes) C-terminally tagged with BioID2 and a FLAG epitope.

- Biotin Treatment: Incubate neurons with 50μM biotin for 24 hours to enable proximity-dependent biotinylation.

- Cell Lysis and Streptavidin Purification: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer and incubate with streptavidin-conjugated beads for 2 hours at 4°C.

- On-Bead Digestion: Wash beads and digest proteins with trypsin overnight at 37°C.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process data using the SAINTexpress algorithm to identify high-confidence interacting proteins, with false discovery rate (FDR) ≤5% [3].

Validation of Protein Interactions

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting:

- Transfect human induced neurons with plasmids expressing tagged bait and prey proteins.

- After 48 hours, lyse cells in mild lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 150mM NaCl, 50mM Tris pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors.

- Incubate lysates with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Wash beads 3× with lysis buffer, elute proteins with 2× Laemmli buffer at 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with appropriate antibodies.

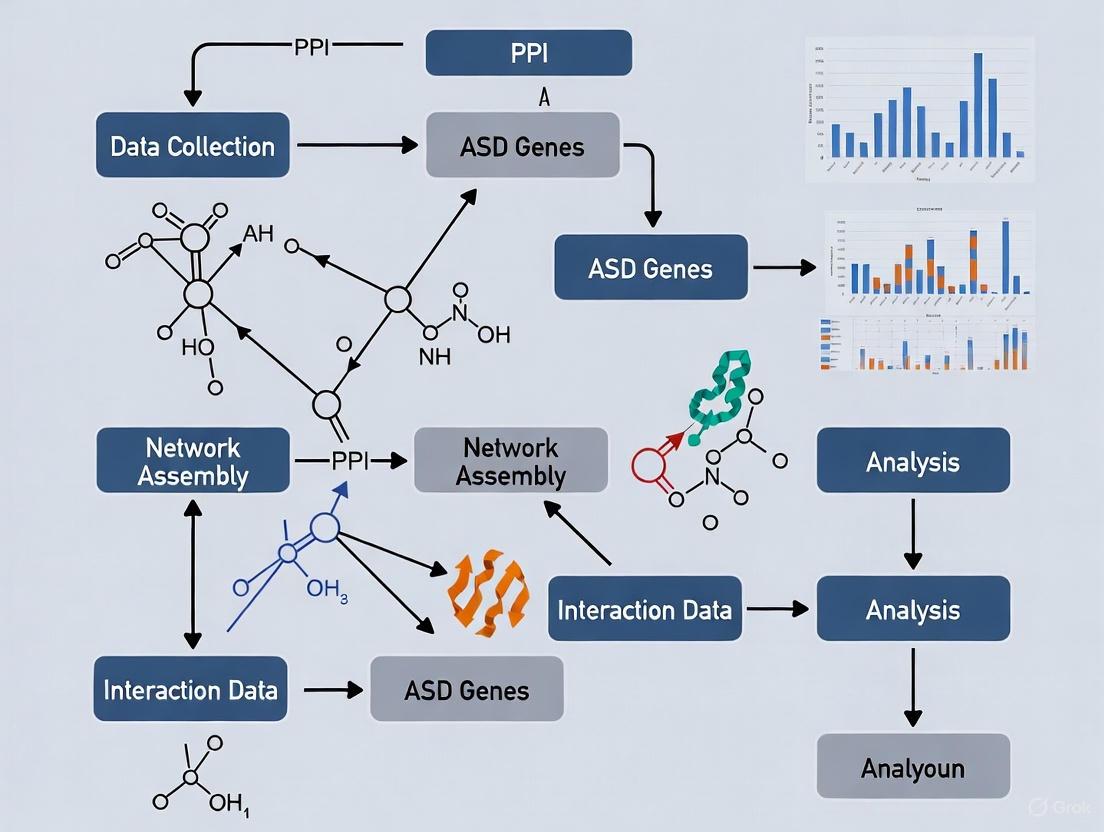

Visualization of Neuron-Specific PPI Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neuron-Specific PPI Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proximity Labeling Enzymes | BioID2, TurboID, APEX2 | Enable proximity-dependent biotinylation in live neurons |

| Cell Culture Systems | Human iPSCs, Neuronal differentiation kits | Source of human excitatory neurons for studies |

| Affinity Purification Materials | Streptavidin beads, FLAG-M2 affinity gel | Isolation of biotinylated proteins or tagged complexes |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems, Trypsin | Protein identification and quantification |

| Bioinformatic Tools | SAINTexpress, Cytoscape, SIGNOR | Statistical analysis of interaction data, network visualization and causal interaction mapping |

| ASD Gene Databases | SFARI Gene database, SIGNOR | Reference datasets for ASD risk genes and causal interactions |

| Validation Reagents | Species-specific antibodies, Plasmid vectors | Confirm protein interactions through orthogonal methods |

Signaling Pathway Convergence in ASD

Cell-type-specific PPI mapping in human neurons represents a crucial methodological advancement for elucidating the molecular pathology of ASD. By moving beyond generic interaction networks to context-specific maps, researchers can identify biologically relevant pathways and interactions that converge across genetically diverse forms of ASD. The experimental protocols outlined here provide a framework for generating neuron-specific interaction data, while the visualization approaches help interpret the complex relationships between ASD risk genes. As these methods become more widely adopted, they will accelerate the identification of therapeutic targets that address the core biology of autism spectrum disorders.

The construction of Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks has become a cornerstone for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying complex diseases such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Traditional PPI networks, however, are predominantly built using single, canonical "reference" isoforms for each gene, overlooking the extensive proteomic diversity generated by alternative splicing. For ASD research, this limitation is particularly critical as the brain exhibits one of the highest frequencies of alternative splicing events among human tissues [5]. Emerging evidence demonstrates that alternative splicing dramatically expands protein interaction capabilities, causing isoforms from the same gene to often behave as functionally distinct entities rather than minor variants within interactome networks [6]. This article details specialized protocols for constructing isoform-resolution PPI networks, enabling researchers to move beyond the single-isoform paradigm and uncover the profound impact of alternative splicing on network topology in the context of ASD.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Evidence

The Functional Divergence of Protein Isoforms

Alternative splicing is not merely a mechanism for transcriptome diversification but a fundamental driver of functional proteome complexity. Systematic interaction profiling of alternatively spliced isoform pairs reveals that the majority share less than 50% of their interaction partners [6]. In the global context of interactome network maps, alternative isoforms tend to behave like distinct proteins encoded by different genes rather than minor variants of each other. These isoform-specific interaction partners are frequently expressed in a highly tissue-specific manner and belong to distinct functional modules, suggesting that a sizable proportion of alternative isoforms in the human proteome constitute "functional alloforms" [6].

Implications for Autism Spectrum Disorder Research

The functional divergence of protein isoforms has profound implications for ASD research. The Autism Spliceform Interaction Network (ASIN) project demonstrated that incorporating brain-expressed alternatively spliced variants of ASD risk factors reveals novel network topology. Remarkably, almost half of the detected interactions and approximately 30% of newly identified interacting partners represented contributions from splicing variants that would be absent in a canonical reference isoform network [5]. Furthermore, these isoform-specific interactions critically contribute to establishing direct physical connections between proteins from de novo autism copy number variations (CNVs), potentially uncovering convergent pathological pathways [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Alternative Splicing on ASD Network Topology

| Metric | Canonical Network | Isoform-Aware Network (ASIN) | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel PPI Detection | Baseline | 91.5% of 506 PPIs were novel [5] | Dramatic expansion of known interactome |

| Isoform-Specific Partners | Not applicable | ~30% of all interacting partners [5] | Reveals previously hidden connections |

| Interaction Profile Similarity | Assumed high | <50% between isoform pairs [6] | Isoforms behave as functionally distinct |

| CNV Gene Connectivity | Limited | Direct physical connections established [5] | Uncovers potential pathological convergence |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction of a Tissue-Specific Isoform ORFeome Library

This protocol describes the creation of a comprehensive open reading frame (ORF) library for splicing isoforms expressed in relevant tissues (e.g., human brain), adapted from the ASIN and ORF-Seq methodologies [5] [6].

Materials and Reagents

- RNA Source: Total RNA from disease-relevant tissue (e.g., pooled fetal and adult human brain) [5]

- Cloning System: Gateway BP and LR Clonase enzyme mix and appropriate vectors [6]

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, gene-specific primers designed to start/stop codons [6]

- Sequencing: Next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina) for deep-well sequencing of cloned ORFs [6]

Procedure

- RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription: Isolve total RNA from pooled tissue samples. Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA.

- Targeted Amplification of ORFs: Amplify full-length ORFs using gene-specific primers targeting the start and stop codons of genes of interest (e.g., ASD risk factors).

- Gateway Cloning: Clone RT-PCR products into a Gateway donor vector using BP recombination. Perform LR recombination to transfer ORFs into expression vectors suitable for downstream interaction assays (e.g., Y2H).

- Sequence Validation: Sequence the cloned ORF library using a deep-well next-generation sequencing approach. Align sequences to genomic and transcriptomic databases to identify novel splicing events and validate full-length isoform sequences.

- Database Comparison: Compare cloned isoform sequences against public databases (CCDS, RefSeq, GenCode, UCSC, MGS, ORFeome) to classify isoforms as known or novel [5].

Protocol 2: Isoform-Specific Protein-Protein Interaction Mapping

This protocol outlines a high-throughput yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) screening approach to map interactions between protein isoforms, based on the ASIN methodology [5].

Materials and Reagents

- Bait and Prey Libraries: The cloned isoform ORFeome library (ASD422) and a human ORFeome collection (e.g., ~15,000 ORFs) [5]

- Yeast Two-Hybrid System: GAL4-based Y2H strain (e.g., AH109), dropout media lacking appropriate amino acids [5]

- Orthogonal Validation System: Mammalian Protein-Protein Interaction Trap (MAPPIT) assay components [5]

Procedure

- Library Transformation: Clone each ORF from the isoform library into both bait (DNA-Binding Domain) and prey (Activation Domain) Y2H vectors.

- High-Throughput Screening: Perform two independent screens:

- Screen A: Test each isoform bait against the entire human ORFeome prey collection.

- Screen B: Test all isoform baits against the entire isoform prey library (all-vs-all).

- Interaction Detection: Plate transformed yeast on selective media and sequence interaction-positive colonies to identify interacting partners.

- Pair-wise Retesting: For each gene, retest all its protein isoforms in pair-wise format against the full series of interactors found for any isoform of that gene. Confirm interactions that score positive in at least three out of four retests to control for sampling sensitivity.

- Orthogonal Validation: Validate a subset of identified interactions (e.g., 62%) using an orthogonal assay such as MAPPIT to ensure high-quality network construction [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Isoform-Aware Network Construction

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Gateway ORF Library | Centralized resource of sequence-validated full-length isoform ORFs | Provides standardized input for interaction screens [6] |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Detects binary protein-protein interactions in high-throughput | Primary screening tool for isoform interactome mapping [5] |

| MAPPIT Assay | Mammalian orthogonal validation of PPIs | Confirms Y2H interactions in a different cellular context [5] |

| SpliceAI | In silico prediction of splicing variants | Prioritizes splice-disrupting variants in patient cohorts [7] |

| Cytoscape | Network visualization and analysis | Visualizes and analyzes isoform-specific networks [8] |

Data Analysis and Visualization

Network Construction and Analysis

Construct an Autism Spliceform Interaction Network (ASIN) by integrating all confirmed isoform-level interactions. At the gene level, this network will appear as a densely connected map of ASD risk factors. However, when deconstructed to the isoform level, the network reveals a more complex topology where different isoforms of the same gene connect to distinct protein complexes and functional modules [5] [6]. Analyze the network to identify:

- Isoform-Specific Network Hubs: Proteins whose isoforms connect otherwise disconnected network components.

- CNV Connectors: Proteins identified as important connectors between genes from ASD-relevant CNV loci [5].

- Functional Modules: Clusters of isoform interactions enriched for specific biological processes (e.g., synaptic transmission, chromatin organization) [9].

Visualization Guidelines for Isoform Networks

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting the complexity of isoform-aware networks. Adhere to the following principles [8]:

- Determine Figure Purpose: Clearly define whether the visualization aims to show network functionality (using directed edges) or structure (using undirected edges).

- Use Intuitive Layouts: Employ force-directed layouts that group conceptually related nodes (e.g., isoforms from the same gene, proteins in the same complex).

- Provide Readable Labels: Ensure all node labels (isoform identifiers) are legible at publication size, using interactive zooming if necessary for dense networks.

- Leverage Color and Shape: Use consistent color schemes (e.g., the provided palette) and shapes to encode attributes like isoform origin (novel vs. known), expression level, or mutation burden.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for constructing an isoform-aware interaction network:

Workflow for Isoform-Aware PPI Network Construction

Application to ASD Research: Case Study

The ASIN methodology was applied to 191 ASD candidate genes, successfully cloning 373 brain-expressed splicing isoforms corresponding to 124 genes. Over 60% of these cloned isoforms were novel—not previously reported in major databases [5]. This isoform-aware approach directly connected genes from a large number of ASD-relevant CNVs into a single connected component, revealing previously hidden connectivity in the autism protein network [5]. Furthermore, a recent study of a Spanish ASD cohort utilizing SpliceAI and SpliceVault identified splicing variants in genes including CACNA1I, CBLB, DLGAP1, and SCN2A, with potential tissue-specific effects in the brain [7]. Gene ontology analysis revealed that ASD genes affected by splicing disruptions are predominantly associated with synaptic organization and transmission, distinguishing them from non-splicing ASD genes which are more implicated in chromatin remodeling processes [7].

The following diagram conceptualizes how alternative splicing diversifies network topology from a single gene product to multiple isoform-specific subnetworks:

Network Topology Shift from Gene to Isoform Level

Incorporating alternative splicing into PPI network construction is not merely a refinement but a fundamental necessity for accurately modeling the molecular underpinnings of complex neurodevelopmental disorders like ASD. The protocols detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers to transition from single-isoform networks to dynamic, isoform-aware interactomes. The demonstrated impact on network topology—including the revelation of novel interactions, establishment of critical CNV connections, and identification of functionally distinct alloforms—underscores that a comprehensive understanding of ASD pathophysiology requires moving beyond the single isoform. Future directions will involve integrating isoform-level networks with multi-omics data and developing splicing-correcting therapeutics that target specific dysfunctional isoforms, ultimately paving the way for more precise diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in ASD.

Identifying Key Network Hubs and Convergent Biological Pathways

The identification of key network hubs and convergent biological pathways is paramount to elucidating the complex etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Research indicates that hundreds of risk genes implicated in ASD converge on a finite set of biological processes, yet the signaling networks at the protein level have remained largely unexplored [10]. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network mapping has emerged as a powerful strategy to bridge this gap, moving beyond genetic associations to reveal functional protein communities and shared pathophysiology. Recent advances in proteomics performed in neuronal contexts have revealed that approximately 90% of neurally relevant PPIs were previously unknown, emphasizing the critical importance of cell-type- and isoform-specific interaction studies [10]. This application note details the experimental protocols, analytical frameworks, and key findings that are defining the next generation of ASD network biology research.

Key Quantitative Findings from Recent ASD PPI Studies

Table 1: Summary of Key Protein Interaction Findings in ASD Research

| Study Focus | Experimental System | Key Quantitative Findings | Identified Convergent Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuronal PPI for 13 high-confidence ASD genes [10] | Human stem-cell-derived neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons (iNs) | - Identified >1,000 interactions- ~90% were novel interactions- 80% replication rate in validation- 3 to 604 interactors per index protein | - Synaptic signaling- Wnt signaling- mTOR pathways- Chromatin remodeling |

| Neuron-specific mapping of 41 ASD risk genes [11] | Primary mouse neurons using BioID2 proximity labeling | - PPI networks disrupted by de novo missense variants- Enrichment of 112 additional ASD risk genes- Networks correlated with clinical behavior scores | - Mitochondrial/metabolic processes- Wnt signaling- MAPK signaling |

| Network pharmacology & machine learning [12] | Human blood sample data (GSE18123) with computational analysis | - Identified 446 DEGs (255 up, 191 down)- Random forest selected 10 key feature genes- MGAT4C showed strong diagnostic power (AUC = 0.730) | - PI3K-Akt signaling- Immune response pathways- Synaptic transmission |

Experimental Protocols for PPI Network Construction

Proximity-Dependent Biotin Identification (BioID2) in Neurons

Principle: This protocol uses a promiscuous biotin ligase fused to ASD risk gene proteins to biotinylate proximal interacting proteins in living neurons, enabling subsequent affinity purification and mass spectrometry identification [11].

Detailed Workflow:

- Construct Generation: Clone full-length coding sequences of ASD risk genes (e.g., SHANK3, NRXN1, CHD8) into mammalian expression vectors containing the BioID2 tag.

- Neuronal Culture and Transfection: Culture primary mouse cortical neurons. Transfect with BioID2-tagged constructs at days in vitro (DIV) 7-10 using calcium phosphate or lipofectamine-based methods.

- Biotin Supplementation: Add 50 µM biotin to the culture medium for 24 hours to allow biotinylation of proteins interacting with the bait protein.

- Cell Lysis and Streptavidin Capture: Lyse neurons in RIPA buffer. Incubate lysates with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads for 2-4 hours to capture biotinylated proteins.

- Stringent Washes: Wash beads sequentially with RIPA buffer, 1M KCl, 0.1M Na₂CO₃, and 2M urea in Tris-HCl to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- On-Bead Digestion: Digest proteins on beads with sequencing-grade trypsin overnight.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Desalt and analyze peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Identify proteins using database search engines (e.g., MaxQuant) against appropriate proteome databases.

Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) in Human Neurons

Principle: This protocol involves immunoprecipitating an index ASD risk protein and its associated complexes from human neuronal models, followed by MS-based identification of co-precipitating proteins [10].

Detailed Workflow:

- Cell Line Generation: Generate human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons (iNs) expressing endogenously or exogenously tagged ASD risk proteins.

- Cross-linking and Cell Lysis: Crosslink cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes (optional, for capturing transient interactions). Quench with 125 mM glycine. Lyse cells in a mild NP-40 or Triton X-100-based lysis buffer.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate cell lysates with antibodies specific to the tag or the endogenous protein, conjugated to magnetic beads. Use isotype control antibodies for control IPs.

- Extensive Washes: Wash beads 3-5 times with lysis buffer to reduce background.

- Elution and Digestion: Elute proteins using low-pH glycine buffer or by boiling in SDS-PAGE buffer. Reduce, alkylate, and digest proteins with trypsin.

- LC-MS/MS and Data Analysis: Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS. Compare protein abundance in experimental versus control IPs using quantitative metrics (e.g., spectral counting, label-free quantification) to identify specific interactors.

Integrative Computational Analysis of PPI Networks

Principle: This protocol details the computational integration of PPI data with other omics datasets to identify hub genes, convergent pathways, and prioritize candidate risk genes [12] [11].

Detailed Workflow:

- PPI Network Construction: Input validated protein interactors into network visualization software (e.g., Cytoscape).

- Hub Gene Identification: Calculate network centrality measures (Degree, Betweenness, Closeness) to identify highly connected nodes. Use CytoHubba plugins for robust analysis.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis on the network proteins using clusterProfiler or similar tools. FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.05 is considered significant.

- Integration with Genetic Data: Overlay the PPI network with genes harboring de novo mutations from large-scale sequencing studies or genes from GWAS. Use "social Manhattan" plots to highlight network-connected genes that may have fallen below genome-wide significance [10].

- Correlation with Clinical Phenotypes: Cluster ASD risk genes based on their PPI network similarity and correlate these clusters with clinical behavior scores (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scores) to link molecular modules to patient outcomes [11].

Visualization of Convergent Pathways in ASD

The following diagram illustrates the key biological pathways and their interconnections identified through PPI network analyses in ASD research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ASD PPI Network Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BioID2 Proximity Labeling System [11] | Enables in vivo biotinylation of protein interactors in live neurons. | - BioID2 plasmid constructs- Biotin (50 µM working solution)- Streptavidin magnetic beads |

| Induced Neuronal Models [10] | Provides human-relevant, neuronal context for PPI studies. | - Neurogenin-2 (Ngn2) induced excitatory neurons (iNs)- iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Proteases | Digests captured protein complexes for LC-MS/MS analysis. | - Sequencing-grade trypsin- Lys-C for complementary digestion |

| Crosslinking Reagents | Stabilizes transient protein interactions. | - Formaldehyde (1%)- Disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG, 3 mM) for enhanced cross-linking [13] |

| Network Analysis Software | Constructs, visualizes, and analyzes PPI networks. | - Cytoscape with CytoHubba plugin [12] |

| Functional Enrichment Tools | Identifies overrepresented biological pathways. | - clusterProfiler R package for GO/KEGG analysis [12] |

Within the broader thesis of constructing Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) research, this application note delineates the critical transition from enumerating candidate genes to understanding their functional convergence within biological systems. ASD's genetic architecture is profoundly heterogeneous, with hundreds of risk genes identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), copy number variant (CNV) analyses, and sequencing efforts [15] [16]. However, individual genetic variants account for a minuscule fraction of cases, underscoring the limitation of list-based approaches [15]. A network view posits that the pathophysiological specificity of ASD arises not from single genes but from the disruption of interconnected protein complexes and biological modules [11] [17]. This paradigm shift is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate genetic discoveries into mechanistic insights and therapeutic targets. Contemporary studies leverage systems biology to map PPI networks, revealing unexpected convergence on pathways such as synaptic function, chromatin remodeling, and mitochondrial metabolism [12] [11]. This document provides a detailed protocol for applying network-based methodologies, summarizing key quantitative findings, and visualizing the integrative workflows that are revolutionizing ASD research.

Key Quantitative Findings from Network-Based ASD Studies

The application of network biology has yielded concrete, quantifiable insights into ASD etiology. The following tables consolidate critical data from recent investigations.

Table 1: Top-Ranked ASD Risk Genes Identified via Network Topology and Machine Learning

| Gene Symbol | SFARI Score [16] | Key Network Property / Role | Associated Biological Process | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHANK3 | 1 (High Confidence) | Key hub in synaptic PPI networks. | Synaptic scaffolding, glutamatergic transmission. | [12] [15] |

| CUL3 | 1 (High Confidence) | High betweenness centrality in SFARI-based PPI network. | Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, regulation of synaptic proteins. | [16] |

| DCAF7 | Not in SFARI (Interactor) | Interacts with 8 ASD-linked proteins; network bottleneck. | Cell division, transcriptional regulation. | [17] |

| ESR1 | N/A | Highest betweenness centrality in network analysis. | Transcriptional regulation, brain development. | [16] |

| MGAT4C | N/A | Top diagnostic biomarker (AUC=0.730) from RF analysis. | Protein glycosylation, immune modulation. | [12] |

| FOXP1 | Syndromic | Missense variants disrupt PPI networks per deep-learning model. | Transcriptional regulation, forebrain development. | [17] |

| TUBB2A | N/A | Key feature gene from random forest analysis. | Microtubule dynamics, neuronal migration. | [12] |

| ARID1B | 1 (High Confidence) | Member of BAF chromatin complex in co-expression module M3. | Chromatin remodeling, neural differentiation. | [15] |

Table 2: Enriched Biological Pathways and Modules in ASD PPI Networks

| Pathway / Module Name | Core Function | Enrichment Source | Key Member Genes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Transmission & Maturation (M13, M16, M17) | Sequential phases of synaptic development and function. | WGCNA of developing human cortex. | GRIN2A, GABRA1, NRXN1, CACNA1C | [15] |

| Chromatin Remodeling & Transcriptional Regulation (M2, M3) | DNA binding, transcriptional regulation, progenitor fate. | WGCNA of developing human cortex. | ARID1B, SMARCA4, BCL11A | [15] |

| Mitochondrial & Metabolic Processes | Mitochondrial activity, metabolic regulation. | Neuron-specific BioID PPI networks. | Multiple ASD risk genes converge | [11] |

| Wnt & MAPK Signaling | Cell signaling, growth, differentiation. | Neuron-specific BioID PPI networks. | Multiple ASD risk genes converge | [11] |

| Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis | Protein degradation and turnover. | Over-representation analysis of CNV-mapped genes. | CUL3, UBE3A | [16] |

| Immune Response Pathways | Immune system modulation, inflammation. | Immune infiltration & cortex-specific PPI from SNPs. | HLA genes, BTN family | [12] [18] |

Table 3: Diagnostic Performance of Key Feature Genes (ROC Analysis)

| Gene Symbol | AUC (Area Under Curve) | Interpretation (AUC > 0.7 = Good) | Analysis Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MGAT4C | 0.730 | Strong discriminatory power | Blood transcriptome, ASD vs. Controls [12] |

| GABRE | 0.720 | Good discriminatory power | Blood transcriptome, ASD vs. Controls [12] |

| TRAK1 | 0.715 | Good discriminatory power | Blood transcriptome, ASD vs. Controls [12] |

| NLRP3 | 0.705 | Good discriminatory power | Blood transcriptome, ASD vs. Controls [12] |

| Combined 10-Gene Panel | Higher than individual | Improved diagnostic potential | Random Forest selected features [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction and Analysis of a Disease-Focused PPI Network

Objective: To build a protein-protein interaction network centered on known ASD risk genes and identify high-priority candidates via topological analysis. Applications: Gene prioritization from large-scale genetic data (e.g., CNVs, WES), identification of novel therapeutic targets. Materials & Software: SFARI Gene database, IMEx or STRING database for interactions, Cytoscape (v3.10.3+), network analysis plugins (e.g., CytoHubba), R/Python for statistics. Procedure:

- Seed Gene Compilation: Download a list of high-confidence ASD risk genes. For example, retrieve all non-syndromic genes with SFARI scores 1 and 2 from the SFARI Gene database [16].

- Interaction Retrieval: Query a consolidated PPI database (e.g., IMEx via the

imexR package, or STRING DB) to obtain the first-order interactors (physical interactions) of the seed genes. Use a high-confidence score threshold (e.g., STRING combined score > 0.7) [12] [16]. - Network Construction: Create an undirected network where nodes represent proteins (seed genes and interactors) and edges represent physical interactions. The resulting network (e.g., Network A in [16]) may contain thousands of nodes.

- Topological Analysis:

- Calculate centrality measures for all nodes: Degree (number of connections), Betweenness Centrality (frequency of a node lying on shortest paths between other nodes), and Closeness Centrality.

- Prioritization: Rank genes based on betweenness centrality, as it identifies bottleneck proteins critical for information flow. Genes like ESR1, CUL3, and MEOX2 emerge as top candidates in such analyses [16].

- Validation and Enrichment:

- Assess the specificity of your network by comparing the enrichment of SFARI genes against randomly selected gene sets of equal size (one-sample t-test) [16].

- Perform functional over-representation analysis (ORA) on the top-ranked genes or network clusters using Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathways to identify convergent biology (e.g., ubiquitination, chromatin remodeling) [16].

Protocol 2: Integrating Transcriptomics with PPI Networks using Random Forest

Objective: To identify robust feature genes for ASD diagnosis by combining differential expression with network-informed machine learning.

Applications: Biomarker discovery, understanding transcriptomic signatures in accessible tissues (e.g., blood).

Materials & Software: R software (v4.2.2+), Bioconductor packages (limma, randomForest, pROC), GEO dataset (e.g., GSE18123), STRING DB.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing & DEG Identification: Download and preprocess relevant transcriptomic data (e.g., blood microarray data GSE18123). Use the

limmapackage to perform differential expression analysis between ASD and control groups. Apply filters (e.g., \|log2FC\| > 1.5, adjusted p-value < 0.05) to identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) [12]. - Network-Enhanced Feature Pool: Intersect the DEG list with known ASD-related genes from GeneCards or SFARI to create a candidate gene list. Optionally, expand this list by adding first interactors from a PPI database to incorporate network context [12].

- Random Forest Training:

- Split the expression data (for the candidate genes) into training (70%) and validation (30%) sets.

- Train a Random Forest model using the

randomForestR package (parameters:ntree=500) on the training set. Use the gene expression values as features and diagnosis as the outcome. - Extract the MeanDecreaseGini importance score for each gene, which measures its contribution to classification accuracy [12].

- Feature Selection & Validation: Select the top N (e.g., 10) genes with the highest importance scores as the feature set. Validate the model's performance on the held-out test set using a confusion matrix and calculate the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) for each key gene using the

pROCpackage [12]. - Downstream Analysis: Subject the final feature genes (e.g., SHANK3, MGAT4C, NLRP3) to immune infiltration correlation analysis and functional enrichment to interpret their biological roles [12].

Protocol 3: Neuron-Specific Protein Interaction Mapping via BioID2

Objective: To define cell-type-specific PPI networks for ASD risk genes in a native neuronal context. Applications: Uncovering cell-type-specific mechanisms, assessing the impact of missense variants on interactions, identifying convergent pathways. Materials & Software: Primary mouse neurons or human iPSC-derived neurons, BioID2 tagging system, lentiviral vectors for gene/isoform-specific expression, Streptavidin beads, Mass Spectrometry, CRISPR-Cas9 for knockout validation. Procedure:

- Construct Generation: Clone cDNA for ASD risk genes (full-length or specific isoforms) into vectors fused at the N- or C-terminus with the promiscuous biotin ligase BioID2. Generate parallel constructs for patient-derived missense variants [11].

- Neuronal Transduction & Biotin Labeling: Transduce primary cortical neurons (e.g., from E16.5 mouse embryos) or human iPSC-derived neurons with lentivirus carrying the BioID2 constructs. Culture neurons for sufficient expression (e.g., 7-10 days in vitro), then treat with biotin (50 µM) for 24 hours to label proximal interactors [11].

- Affinity Purification & Proteomics:

- Lyse neurons in RIPA buffer.

- Incubate lysates with Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to capture biotinylated proteins.

- Wash stringently, on-bead digest with trypsin, and elute peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis.

- Data Analysis & Network Construction:

- Identify high-confidence interacting proteins (HCIPs) using significance analysis (e.g., SAINTexpress) comparing bait samples to controls (e.g., BioID2-only).

- For each bait gene, construct a PPI network. Merge individual networks to create a global ASD risk gene interactome. Use tools like Cytoscape for visualization [11].

- Functional Validation:

- Perform Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) on the combined network to identify convergent pathways (e.g., mitochondrial metabolism, Wnt signaling) [11].

- Validate pathway relevance using CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of selected risk genes in neurons and assay mitochondrial function (e.g., Seahorse Analyzer) [11].

- Correlate network clusters (gene groups) with clinical severity scores from patient databases (e.g., MSSNG) to link biology to phenotype [11].

Protocol 4: Immune Infiltration Analysis Correlated with Key Genes

Objective: To explore the relationship between ASD feature gene expression and the composition of immune cell populations in tissue samples.

Applications: Understanding neuroimmune aspects of ASD, identifying potential immunomodulatory biomarkers.

Materials & Software: R packages GSVA, CIBERSORT or xCell, corrplot, ggplot2. Gene expression matrix from tissue (e.g., blood, post-mortem brain).

Procedure:

- Immune Deconvolution: Use a deconvolution algorithm (e.g., via the

GSVApackage with a signature gene set likeLM22for CIBERSORT) on the normalized gene expression matrix. This estimates the relative abundance or activity of various immune cell types (e.g., T-cells, B-cells, monocytes, neutrophils) in each sample [12]. - Correlation Analysis: Calculate Spearman or Pearson correlation coefficients between the expression levels of your key ASD genes (e.g., the top 10 from Random Forest) and the estimated proportions of each immune cell type.

- Statistical Testing & Visualization: Adjust p-values for multiple testing (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg). Create a correlation heatmap using the

corrplotpackage, where rows are genes, columns are immune cells, and cells are colored by correlation coefficient and significance [12]. - Interpretation: Significant positive or negative correlations suggest pleiotropic associations between specific genes and the immune microenvironment, which may be relevant to ASD pathophysiology and comorbid inflammation [12].

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1 Title: ASD Network Biology Research Workflow

Diagram 2 Title: Convergent Pathways in ASD PPI Networks

Diagram 3 Title: Protocol: Neuron-Specific BioID for ASD Gene Networks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents, Tools, and Databases for ASD PPI Network Research

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape | Software Platform | Visualization, integration, and topological analysis of molecular interaction networks. Essential for visualizing PPI and co-expression networks. | [12] [19] |

| STRING Database | Online Database/Resource | Provides known and predicted PPIs, including physical and functional associations. Used for initial network construction and enrichment. | [12] [9] |

| IMEx Consortium Databases | Curated Database | Source of high-quality, experimentally verified protein-protein interaction data. Critical for building reliable seed networks. | [16] |

| BioID2 System | Molecular Biology Reagent | A promiscuous biotin ligase used for proximity-dependent biotinylation labeling in live cells. Enables mapping of PPIs in native cellular contexts (e.g., neurons). | [11] |

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated Knowledgebase | Manually curated list of ASD-associated genes with confidence scores. The primary source for seed genes in network studies. | [15] [16] [9] |

R randomForest Package |

Software Library | Implements the Random Forest algorithm for classification and regression. Used to identify key feature genes from omics data based on variable importance. | [12] |

| Human iPSC Lines & Neuronal Differentiation Kits | Cell Biology Reagent | Provide a genetically tractable, human-relevant model system to study ASD risk genes in neurons and perform functional validation (e.g., CRISPR, BioID). | [11] [17] |

limma R Package |

Software Library | Performs differential expression analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. Foundational for identifying transcriptomic signatures. | [12] |

| AlphaFold2/3 & ESMFold | AI Prediction Tool | Provides high-accuracy protein structure predictions. Used to model how ASD-linked missense variants might disrupt physical interactions. | [17] [20] |

| GSVA / CIBERSORT R Packages | Software Library | Perform gene set variation analysis and immune cell deconvolution, respectively. Key for linking gene expression to biological processes and immune context. | [12] |

From Data to Discovery: Methodologies for Constructing and Analyzing ASD PPI Networks

Understanding the intricate protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks underlying autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is crucial for elucidating its complex pathophysiology. The functional implications of genes and their variants in autism heterogeneity present significant challenges, requiring sophisticated experimental approaches to map and characterize these biological networks [21]. Two powerful techniques—Immunoprecipitation Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) and Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) systems—have emerged as cornerstone methodologies for constructing comprehensive PPI maps in ASD research. These complementary approaches enable researchers to identify novel protein interactions, validate suspected complexes, and delineate signaling pathways relevant to neurodevelopment and ASD pathogenesis.

IP-MS offers the distinct advantage of characterizing multiprotein complexes under near-physiological conditions, preserving post-translational modifications and native stoichiometries. Meanwhile, Y2H systems provide unparalleled sensitivity for detecting binary interactions, including those that may be transient or weak. When applied to induced neurons modeling ASD, these techniques can reveal disease-specific alterations in interaction networks, offering insights into the molecular mechanisms driving this heterogeneous condition [22]. The integration of data from these approaches is helping researchers build comprehensive interactomes for ASD-associated proteins, moving beyond single-gene analyses to network-level understanding [21].

Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) in Neuronal Systems

Fundamental Principles and Applications

IP-MS combines the specificity of antibody-based immunoprecipitation with the analytical power of mass spectrometry to identify protein complexes in their native state. This approach is particularly valuable for studying ASD-relevant proteins that function in large macromolecular assemblies, such as those found in the postsynaptic density [22]. Recent advances in ultra-low-input MS methodologies have enabled applications in rare cell populations and specific neuronal subtypes, making IP-MS increasingly relevant for studying induced neuron models of ASD [23].

The technique involves several key steps: (1) gentle cell lysis to preserve native protein complexes, (2) antibody-mediated capture of the target protein and its associated partners, (3) rigorous washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins, and (4) identification of co-purifying proteins via high-sensitivity mass spectrometry. Quantitative variations of IP-MS, such as those utilizing stable isotope labeling, can further distinguish specific interactors from background contaminants, providing confidence in identified interactions [23].

IP-MS Protocol for Neuronal Protein Complex Analysis

Cell Lysis and Complex Stabilization

- Harvest induced neurons and lyse in ice-cold IP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors [24].

- Conduct mechanical disruption using a Dounce homogenizer (15-20 strokes) followed by incubation on ice for 30 minutes.

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Retain supernatant for protein quantification.

Optimized Immunoprecipitation

- Pre-clear lysates with protein A/G magnetic beads for 30 minutes at 4°C to reduce non-specific binding.

- Incubate pre-cleared lysates with target-specific antibody (2-5 μg per 500 μg total protein) for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Add protein A/G magnetic beads (50 μL bead slurry per sample) and incubate for an additional 1-2 hours.

- Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer (4 washes, 5 minutes each) under stringent but non-denaturing conditions.

On-Bead Digestion and MS Sample Preparation

- Resuspend beads in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 0.5% SDC and 10 mM DTT. Reduce disulfide bonds at 56°C for 30 minutes [24].

- Alkylate with 25 mM iodoacetamide for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Digest proteins with sequencing-grade trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio) overnight at 37°C.

- Acidify with 1% formic acid to precipitate SDC, followed by centrifugation to recover peptides.

Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- Desalt peptides using C18 stage tips and reconstitute in 0.1% formic acid.

- Separate peptides via reverse-phase nano-liquid chromatography using a 60-minute gradient (5-35% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid).

- Analyze eluting peptides using a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-Exactive HF-X or TimSTOF Pro) operating in data-dependent acquisition mode.

- Acquire MS1 spectra at 60,000 resolution, followed by MS2 fragmentation of the top 20 most intense ions per cycle.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Neuronal IP-MS

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Detergents | IGEPAL CA-630, SDC | SDC at 4% concentration shows superior extraction efficiency for neuronal membrane proteins [24] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Complete Mini EDTA-free | Preserves protein integrity during extraction from neuronal cultures |

| Magnetic Beads | Protein A/G magnetic beads | Enable efficient pull-down and reduced non-specific binding |

| Digestion Enhancers | RapiGest SF, SDC | SDC compatible with trypsin digestion at concentrations up to 10% [24] |

| Mass Spectrometry | C18 nano-columns, Formic acid | Essential for peptide separation and ionization |

Data Analysis and Validation

Process raw MS files using search engines (MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer) against appropriate protein databases. Apply strict false discovery rate thresholds (≤1% at protein and peptide levels) and require at least two unique peptides per protein identification. Implement quantitative scoring using significance analysis of interactome (SAINT) algorithms to distinguish specific interactions from non-specific background. Validate key interactions using orthogonal methods such as Western blotting or proximity ligation assays [23].

Yeast Two-Hybrid Systems for ASD Protein Interaction Mapping

System Selection and Principles

The yeast two-hybrid system has evolved significantly from its original conception, with multiple specialized variants now available for different applications in ASD research. The core principle remains the reconstitution of a functional transcription factor through the interaction between two proteins—one fused to a DNA-binding domain (bait) and another to a transcription activation domain (prey) [25]. This system is particularly valuable for ASD research as it can detect binary interactions with high sensitivity, making it ideal for mapping interactions between proteins encoded by ASD-risk genes [21].

For studying ASD-associated proteins, researchers can select from several Y2H configurations:

- Nuclear Y2H: Suitable for soluble proteins that can localize to the yeast nucleus

- Membrane Y2H (MYTH): Optimized for integral membrane proteins using split-ubiquitin system [26] [27]

- Integrated MYTH (iMYTH): Uses genomic tagging to avoid overexpression artifacts [27]

- DoMY-Seq: Combines Y2H with next-generation sequencing for high-resolution domain mapping [28]

Comprehensive Y2H Protocol for ASD Protein Interaction Screening

Bait Vector Construction and Testing

- Clone cDNA encoding the ASD-related protein into both pMW103 (LexA DNA-binding domain fusion) and pJG4-5 (B42 transcription activation domain fusion) vectors to enable reciprocal testing [29].

- Transform bait constructs into the appropriate yeast reporter strain (SKY48 for LexA fusions).

- Assess bait protein expression and localization via Western blotting of yeast extracts.

- Test for autonomous transcriptional activation by plating transformed yeast on medium lacking histidine (-His) and using X-Gal overlay assays. Baits showing significant self-activation require redesign [29].

Library Transformation and Screening

- Perform large-scale transformation of a human fetal brain cDNA library (or other relevant library) into the bait-containing yeast strain using the lithium acetate method.

- Plate transformation mixtures on appropriate selection media (-His, -Leu, -Ura) and incubate at 30°C for 3-7 days.

- Collect colonies growing on selective medium and assay for β-galactosidase activity using X-Gal filter lifts.

- Isolate plasmid DNA from positive colonies and sequence insert fragments to identify interacting proteins.

Interaction Validation and Specificity Testing

- Retransform isolated prey plasmids into fresh yeast with the original bait to confirm the interaction.

- Test interaction specificity by co-transforming prey plasmids with unrelated baits to exclude false positives.

- For membrane protein interactions, use the split-ubiquitin system where the bait protein is fused to Cub-LexA-VP16 (CLV) and prey proteins are fused to NubG [26] [27].

Advanced Applications: DoMY-Seq for Interaction Domain Mapping

- Generate a random fragmentation library of the open reading frame of interest.

- Clone fragments into both bait and prey vectors to create comprehensive domain libraries.

- Perform Y2H screening to enrich for interacting fragments.

- Sequence interacting fragments using next-generation sequencing to precisely map interaction interfaces at high resolution [28].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Yeast Two-Hybrid Systems

| Reagent Type | Specific Resource | Utility in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Y2H Vectors | pMW103 (LexA DBD), pJG4-5 (B42 AD) | Enables reciprocal bait-prey testing for validation |

| Reporter Strains | SKY48, L40 | Contain HIS3, ADE2, and LacZ reporters for multiplexed selection |

| Split-Ubiquitin System | CLV (Cub-LexA-VP16), NubG tags | Essential for studying membrane proteins, including neurotransmitter receptors and adhesion molecules implicated in ASD [26] |

| cDNA Libraries | Human fetal brain, induced neuron | ASD-relevant tissue sources for interaction discovery |

| Selection Media | -His, -Leu, -Ura dropout mixes | Enable selection for protein interactions and plasmid maintenance |

Integrated Workflows and Data Integration

Complementary Applications in ASD Research

The true power of IP-MS and Y2H emerges when these techniques are applied in an integrated manner to build comprehensive ASD protein interaction networks. Y2H excels at discovering novel binary interactions, while IP-MS provides information about native complex composition under physiological conditions. Recent studies have demonstrated the value of this integrated approach for characterizing ASD-relevant protein complexes, such as those involving SH3RF2, CaMKII, and PPP1CC, which form a critical complex maintaining striatal asymmetry [22].

For ASD research, a typical integrated workflow might include:

- Initial Y2H screening to identify binary interactions between ASD-risk gene products

- IP-MS validation of these interactions in induced neuronal models

- Functional characterization of identified complexes in neuronal development and function

- Assessment of how ASD-associated mutations disrupt these interactions

This approach has revealed biologically distinct subtypes of autism with different underlying genetic programs, highlighting the importance of protein network analysis for understanding ASD heterogeneity [30].

Experimental Design Considerations for ASD Studies

When designing interaction studies for ASD research, several considerations are particularly important:

- Cell type relevance: Use induced neurons rather than non-neuronal cell types to ensure physiological relevance

- Developmental timing: Consider the appropriate developmental stage, as ASD-related genes often function during specific windows of neurodevelopment [21]

- Interaction context: Include both overexpressed and endogenous tagging approaches to balance detection sensitivity and physiological relevance

- Validation strategies: Implement multiple orthogonal methods to confirm interactions, especially for novel findings

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental approaches discussed in this application note:

The combination of IP-MS and yeast two-hybrid methodologies provides a powerful toolkit for deconstructing the complex protein interaction networks underlying autism spectrum disorder. As research moves toward personalized approaches for ASD, these techniques will be essential for identifying biologically distinct subtypes and developing targeted interventions. The continued refinement of these protocols—particularly through enhancements in sensitivity, quantification, and adaptation to human neuronal models—promises to accelerate our understanding of ASD pathophysiology and open new avenues for therapeutic development.

Leveraging Machine Learning and Network Propagation for Gene Prioritization

The identification of causal genes for complex genetic disorders, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), represents a significant challenge in modern genomics. ASD is a highly heritable neurodevelopmental condition affecting approximately 1% of the population, characterized by impairments in social communication and repetitive behaviors [9]. While large-scale genomic studies have generated numerous candidate genes, experimental validation of all potential associations remains prohibitively expensive and time-consuming [31]. This protocol details an integrated computational approach that combines network propagation techniques with machine learning classification to prioritize high-probability ASD risk genes from genomic datasets. This methodology enables researchers to bridge the gap between basic transcriptomic discoveries and clinical applications by systematically identifying and validating the most promising therapeutic targets [32] [9].

Background and Principles

The Gene Prioritization Problem in ASD Research

The genetic architecture of ASD involves considerable heterogeneity, with contributions from both rare and common variants across hundreds of genes [33] [34]. Traditional genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous candidate regions, but these often contain multiple genes, only a few of which are genuinely associated with the phenotype [31]. Gene prioritization strategies address this challenge by ranking candidate genes according to their potential relevance to ASD pathogenesis, enabling researchers to focus validation efforts on the most promising candidates.

Theoretical Foundation

The methodology described in this protocol operates on two fundamental biological principles:

Guilt-by-Association: Genes involved in the same disease phenotype tend to interact within molecular networks or participate in shared biological pathways [33] [34]. Proteins encoded by ASD-associated genes demonstrate significant direct interactions beyond random expectation, forming functionally coherent networks [33].

Multi-Omic Convergence: ASD risk genes exhibit distinctive patterns across genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets, including specific spatiotemporal expression profiles in the developing human brain and characteristic intolerance to functional genetic variation [34].

Materials and Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Resources and Databases

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Purpose in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks | STRING, BioGRID, HPRD, IntAct, MINT [33] | Provides physical and functional interaction data between gene products as the foundation for network propagation |

| ASD-Associated Gene Sets | SFARI Gene Database [9] [34] | Serves as curated training data ("seed genes") and benchmarking standard |

| Gene Expression Data | BrainSpan Atlas [34] | Provides spatiotemporal transcriptome data for feature generation |

| Gene-Level Constraint Metrics | ExAC/gnomAD pLI scores [34] | Quantifies gene intolerance to variation as a predictive feature |

| Functional Enrichment Analysis | g:Profiler, clusterProfiler [9] [35] | Interprets biological relevance of prioritized gene sets |

| Network Analysis & Visualization | Cytoscape (with cytoHubba plugin) [35] [8] | Constructs, analyzes, and visualizes interaction networks |

| Programming Environments | R (limma, igraph), Python (scikit-learn) [9] [35] | Provides statistical analysis, network feature extraction, and machine learning capabilities |

Methodological Workflow

The following integrated protocol for gene prioritization comprises two primary stages: network-based feature generation and machine learning-based classification.

Stage 1: Network Propagation and Feature Generation

This stage transforms initial genetic associations into network-informed features.

Input Data Preparation

- Seed Gene Selection: Compile a set of high-confidence ASD-associated genes. The SFARI Gene database is the standard resource, with "Category 1" (high-confidence) genes typically used as positive training examples [9] [34].

- Candidate Gene Definition: Define the target set of candidate genes for prioritization. This can be the entire genome or a specific set of genes from a GWAS locus or transcriptomic study.

- PPI Network Acquisition: Obtain a comprehensive human PPI network. A consolidated network from multiple sources (e.g., STRING, BioGRID) is recommended for coverage. The network should be represented as a graph ( G = (V, E) ), where ( V ) is the set of proteins (nodes) and ( E ) is the set of interactions (edges) [9] [33].

Network Propagation Process

Network propagation diffuses information from seed genes across the PPI network to identify regions with high proximity to known disease-associated genes.

- Initialization: For a given seed gene list ( S ) of size ( s ), set the initial score ( f_0(i) = 1/s ) for each seed protein ( i \in S ). All other proteins receive an initial score of 0 [9].

- Iterative Propagation: Execute the propagation update until scores stabilize: ( f{t+1} = \alpha \cdot W \cdot ft + (1 - \alpha) \cdot f_0 ) where ( W ) is the column-normalized adjacency matrix of the PPI network, and ( \alpha ) is a damping parameter (typically set to 0.8) that controls the relative influence of network neighbors versus initial seeds [9].

- Score Normalization: Normalize the resulting propagation scores using a method like eigenvector centrality to mitigate biases introduced by node degree [9].

Multi-Omic Feature Integration

Repeat the propagation process using multiple different ASD-related gene lists derived from various genomic and functional datasets to create a rich feature matrix. Potential data sources include:

- Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [9]

- Differential gene expression (DGE) analyses [32] [9]

- Differential methylation studies [9]

- Copy number variation (CNV) analyses [9]

Each propagation result constitutes a distinct network feature for every gene in the network.

Stage 2: Machine Learning Classification

This stage integrates the generated features to produce a final, prioritized gene list.

Training Set Construction

- Positive Labels: Use high-confidence ASD genes from SFARI Category 1 [9] [34].

- Negative Labels: Select genes not associated with ASD or other neurodevelopmental disorders. Genes associated with non-mental health diseases, as annotated in OMIM, can serve as appropriate negatives [34].

Feature Set Compilation

For each gene in the training set, compile a feature vector that includes:

- The ten network propagation scores from Stage 1 [9].

- Additional predictive features such as:

Model Training and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Implement a Random Forest classifier using standard parameters (e.g., 100 trees, no maximum depth) via Python's scikit-learn package [9].

- Cross-Validation: Perform 5-fold cross-validation to assess model performance and generalizability. The model should achieve a mean area under the ROC curve (AUROC) >0.85 and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) >0.85 [9].

- Model Application: Apply the trained model to score and rank all candidate genes. An optimal classification cutoff can be determined to maximize the product of specificity and sensitivity [9].

Stage 3: Validation and Biological Interpretation

Performance Assessment

- Benchmarking: Compare predictions against independent validation sets, such as SFARI Score 2 and 3 genes, which should receive significantly higher scores than random genes [9].

- Specificity Analysis: Test the model on genes associated with unrelated diseases to ensure predictions are specific to ASD biology.

Functional Annotation of Prioritized Genes

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., using g:Profiler) on top-ranked genes to identify overrepresented biological processes (e.g., chromatin organization, neuron cell-cell adhesion) [32] [9].

- Immune Correlation Analysis: For ASD research, conduct immune infiltration correlation analysis using tools like CIBERSORT to explore associations between hub genes and immune cell profiles [32] [35].

Anticipated Results and Outputs

Quantitative Performance Metrics

When implemented correctly, this pipeline yields high predictive accuracy as demonstrated in prior studies:

Table 2: Expected Performance Metrics

| Evaluation Metric | Expected Outcome | Reference Performance |

|---|---|---|

| AUROC (5-fold CV) | > 0.85 | 0.87 [9] |

| AUPRC (5-fold CV) | > 0.85 | 0.89 [9] |

| Validation on SFARI Score 2/3 Genes | Significant enrichment (p < 3.62e-34) | Confirmed [9] |

Biological Insights

Successful application of this protocol will identify both known ASD risk genes and novel candidates. For example, one study identified 10 key feature genes (including SHANK3, NLRP3, and GABRE) with high importance scores for ASD prediction [32]. Functional analysis typically reveals enrichment in biological processes highly relevant to ASD, including:

- Chromatin organization and histone modification [9]

- Neuronal signaling and synaptic function [34]

- Regulation of RNA alternative splicing [34]

- Immune and inflammatory responses [32]

Visual Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational pipeline for gene prioritization:

Integrated Computational Pipeline for ASD Gene Prioritization

Applications in ASD Research

This methodology has demonstrated significant utility in advancing ASD research by:

Identifying Novel ASD Genes: The approach successfully highlights novel candidate genes beyond those identified through association studies alone. For example, one application identified MYCBP2 and CAND1, which are involved in protein ubiquitination—a potentially novel mechanism in ASD pathogenesis [34].

Uncovering Disease Mechanisms: Prioritized genes consistently converge on specific biological pathways, such as chromatin remodeling, synaptic function, and immune dysregulation, providing insights into ASD etiology [32] [34].

Revealing Therapeutic Targets: The identified hub genes and their associated networks provide a foundation for drug discovery. Connectivity Map (CMap) analysis can predict potential drugs that reverse observed gene expression signatures, with some predictions consistent with clinical trial results [32].

Informing Biomarker Development: Specific genes with high discriminatory power (e.g., MGAT4C, AUC=0.730) emerge as potential robust biomarkers for ASD diagnosis and stratification [32].

This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging machine learning and network propagation to prioritize ASD risk genes, enabling researchers to efficiently translate genomic findings into biological insights and therapeutic leads.

In the study of complex biological systems, Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks provide a powerful framework for understanding how cellular components collaborate to perform biological functions. Among various topological measures used to analyze these networks, betweenness centrality has emerged as a crucial metric for identifying influential nodes. Betweenness centrality quantifies the extent to which a node acts as a bridge along the shortest paths between other nodes in the network [36]. In practical terms, proteins with high betweenness centrality often serve as critical information flow regulators and represent potential control points within cellular systems [37].

The theoretical foundation of betweenness centrality lies in its ability to identify nodes that may not necessarily have the most connections but occupy strategically important positions within the network structure. These proteins function as bottlenecks that can control the flow of biological information between different network modules [38]. In disease research, particularly in complex disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), these bottleneck proteins have proven valuable for prioritizing candidate genes from large genomic datasets and identifying potential therapeutic targets [16]. The application of betweenness centrality in biological networks represents a shift from traditional reductionist approaches to a more holistic systems-level understanding of disease mechanisms.

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithmic Principles

Mathematical Definition

Betweenness centrality is formally defined for a node ( N ) in a network as the sum of the fraction of all shortest paths between pairs of nodes that pass through ( N ). The mathematical representation is:

[ BC(N) = \sum{v1 \neq N \neq v2} \frac{\sigma{v1,v2}(N)}{\sigma_{v1,v2}} ]

Where ( \sigma{v1,v2} ) is the total number of shortest paths from node ( v1 ) to node ( v2 ), and ( \sigma{v1,v2}(N) ) is the number of those paths that pass through node ( N ) [36]. This calculation measures the control that a node exerts over the communication between other nodes in the network.

Biological Interpretation

In PPI networks, proteins with high betweenness centrality play roles analogous to major bridges or intersections in road networks. They often connect functional modules and facilitate communication between different cellular processes [38]. While hub proteins (those with many connections) are important, bottleneck proteins with high betweenness may have more strategic control over network dynamics. These proteins are frequently associated with essential biological functions, and their disruption can have disproportionate effects on the entire system [37]. In the context of disease networks, these proteins represent critical points whose dysfunction can lead to significant pathological consequences, making them prime candidates for therapeutic intervention [16].

Computational Implementation

The calculation of betweenness centrality can be computationally intensive for large networks, with the Brandes algorithm representing an efficient approach for its computation [37]. The algorithm leverages a breadth-first search strategy to calculate shortest paths, making it suitable for the large-scale PPI networks commonly encountered in systems biology. Implementation is available through various graph analysis platforms, including Memgraph Advanced Graph Extensions (MAGE) and other bioinformatics toolkits, enabling researchers to apply this metric to biological networks of substantial size [37].

Application Notes: Protocol for ASD Gene Prioritization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for prioritizing ASD candidate genes using betweenness centrality in PPI network analysis:

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Collection and Curation

Initiate the process by compiling a comprehensive set of known ASD-associated genes from authoritative databases. The Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Gene database represents a primary resource, containing genes categorized by confidence levels from high confidence (score 1) to minimal evidence (score 4) [16]. For the network construction, prioritize SFARI score 1 and 2 genes (768 genes total) to ensure high-quality seed proteins. Concurrently, retrieve protein-protein interaction data from the International Molecular Exchange (IMEx) consortium databases, which provide experimentally validated interactions with detailed annotations including host organism, assay methods, and interaction types [16]. Supplement this with tissue-specific expression data, particularly from brain tissues, to enable context-specific network filtering.

Step 2: Network Construction and Contextualization

Construct the initial PPI network using the seed genes and their first interactors from the IMEx database. This typically generates a substantial network; for example, in recent ASD research, this approach yielded a network with 12,598 nodes and 286,266 edges [16]. To enhance biological relevance, contextualize this generic network by integrating tissue-specific expression data. Filter the network to include only proteins expressed in brain tissues, utilizing resources such as the Human Protein Atlas brain expression data. This filtering step typically retains approximately 94.3% of nodes while increasing the network's pathological relevance [39]. For quality control, compare the resulting network against randomly generated gene sets to confirm significant enrichment of ASD-associated genes (p-value < 2.2×10−16) [16].

Step 3: Betweenness Centrality Calculation

Execute the betweenness centrality algorithm on the contextualized PPI network using graph analysis platforms such as Memgraph MAGE or comparable bioinformatics tools. The Brandes algorithm implementation is recommended for its efficiency with large biological networks [37]. Calculate the betweenness centrality value for each node, representing the proportion of shortest paths passing through that node. Normalize these values to enable comparison across networks of different sizes. The algorithm output will generate a ranked list of proteins based on their betweenness centrality scores, with higher scores indicating greater potential importance as network regulators.

Step 4: Results Interpretation and Validation

Identify the top-ranking proteins based on betweenness centrality values for further biological interpretation. In ASD networks, proteins such as ESR1, LRRK2, APP, and JUN have been identified as high-betweenness nodes [16]. Subject these candidate proteins to functional validation through several approaches: perform pathway enrichment analysis using over-representation analysis (ORA) with Fisher's exact test and Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction; examine co-expression patterns with known ASD genes in brain-specific transcriptomic datasets; and assess evidence from copy number variant (CNV) data in ASD patient cohorts [16] [39]. This multi-faceted validation approach strengthens confidence in the prioritization results.

Expected Results and Outputs

Successful implementation of this protocol typically identifies both known and novel candidate genes. For example, in recent ASD research, this approach highlighted known high-confidence ASD genes like CUL3 while also revealing novel candidates such as CDC5L, RYBP, and MEOX2 based on their high betweenness centrality [16]. Pathway analysis of high-betweenness genes often reveals enrichment in biologically relevant processes; in ASD, these have included ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and cannabinoid receptor signaling pathways [16]. The tabular output should include the betweenness centrality scores, relative rankings, and additional annotations for candidate prioritization.

Case Study: ASD Gene Prioritization

Experimental Setup and Network Properties

In a recent comprehensive study, researchers applied betweenness centrality analysis to prioritize ASD candidate genes [16]. The initial PPI network was constructed using 768 SFARI genes (scores 1 and 2) as seeds, retrieving their first interactors from the IMEx database. The resulting network comprised 12,598 nodes connected by 286,266 edges, representing approximately 63% of human protein-coding genes. Statistical validation confirmed significant enrichment of SFARI genes compared to randomly generated networks (p < 2.2×10−16) [16]. Before topological analysis, the network was contextualized using brain expression data from the Human Protein Atlas, retaining 11,879 nodes (94.3%) with confirmed brain expression.

Key Findings and Candidate Genes

The betweenness centrality analysis revealed several high-priority candidate genes, as summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Top High-Betweenness Centrality Genes in ASD PPI Network

| Gene Symbol | SFARI Category | Betweenness Centrality | Relative Betweenness (%) | Known ASD Association | Potential Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR1 | Not in SFARI | 0.0441 | 100.00 | Previously unknown | Hormone signaling in brain development |

| LRRK2 | Not in SFARI | 0.0349 | 79.14 | Parkinson's link | Neuronal function and autophagy |

| APP | Not in SFARI | 0.0240 | 54.42 | Alzheimer's link | Synaptic formation and repair |

| JUN | Not in SFARI | 0.0200 | 45.35 | Previously unknown | Transcriptional regulation |

| CUL3 | Score 1 | 0.0150 | 34.01 | Known ASD gene | Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis |

| YWHAG | Score 3 | 0.0097 | 22.00 | Syndromic | Synaptic signaling |

| MAPT | Score 3 | 0.0096 | 21.77 | Tauopathy link | Microtubule stability |

| MEOX2 | Not in SFARI | 0.0087 | 19.73 | Novel candidate | Brain development |

The analysis successfully identified both known ASD genes and novel candidates. Particularly noteworthy was the identification of CUL3, a known high-confidence ASD gene (SFARI score 1), validating the approach's ability to recapture established biological knowledge [16]. More importantly, the analysis revealed novel candidates not previously strongly associated with ASD, including ESR1, LRRK2, and MEOX2, providing new directions for experimental validation. Pathway enrichment analysis of high-betweenness genes identified significant involvement in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and cannabinoid receptor signaling, pathways not traditionally emphasized in ASD research but providing potential new mechanistic insights [16].

Technical Validation