Bridging the Validation Gap in Predictive Systems Biology: From Computational Models to Clinical Translation

Predictive systems biology holds immense potential for revolutionizing drug discovery and personalized medicine, yet a significant validation gap often separates computational predictions from biological reality.

Bridging the Validation Gap in Predictive Systems Biology: From Computational Models to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Predictive systems biology holds immense potential for revolutionizing drug discovery and personalized medicine, yet a significant validation gap often separates computational predictions from biological reality. This article explores the critical challenges and solutions in validating predictive models, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We examine the foundational principles defining the validation gap, methodological advances in model construction and gap-filling algorithms, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance, and rigorous frameworks for experimental and clinical validation. By synthesizing insights from recent studies on metabolic model reconstruction, biological age estimation, and multi-omics integration, this comprehensive review provides a roadmap for enhancing the reliability and clinical applicability of systems biology predictions.

Defining the Validation Gap: When Computational Predictions Diverge from Biological Reality

Predictive modeling in systems biology represents a powerful shift from reductionist methods to a holistic framework, integrating diverse data types—genomics, proteomics, metabolomics—into comprehensive mathematical models to simulate the behavior of entire biological systems [1]. These models incorporate parameters representing molecular interactions, reaction kinetics, and regulatory feedback loops, enabling researchers to predict system responses to various stimuli or perturbations. However, the true value of these simulations hinges on their ability to accurately reflect real-world biology, a process achieved through rigorous validation against experimental data [1]. Despite advanced algorithms and increasing computational power, a significant disconnect often persists between model predictions and experimental observations, creating a "validation gap" that undermines the reliability of computational findings in biological research and drug development.

This guide objectively compares different computational approaches by examining their performance against experimental data, detailing the methodologies that yield the most biologically credible results. The disconnect stems from multiple sources: inadequate model parameterization, oversimplified biological representations, and technical inconsistencies between computational and experimental setups. In clinical applications, such as predicting immunotherapy response, this gap has substantial implications; despite the revolution brought by immune checkpoint inhibitors, only 20–30% of patients experience sustained benefit, underscoring the critical need for precise, clinically actionable predictive tools [2]. By dissecting the root causes and presenting comparative validation data, this guide provides a framework for researchers to bridge this gap, enhancing the translational potential of computational systems biology.

Biological Complexity and Model Oversimplification

Biological systems are inherently complex, non-linear, and multi-scale. A primary source of disconnect arises when computational models fail to capture this full complexity.

- Limitations of Single Biomarkers: Traditional biomarkers, such as PD-L1 expression or tumor mutational burden (TMB), have long been used for patient stratification. However, their predictive accuracy is limited; for example, PD-L1 expression is predictive in only about 29% of FDA-approved indications [2]. Relying on single markers ignores the complex interplay within the tumor microenvironment.

- Need for Multi-Modal Integration: Models integrating genomic, spatial, clinical, and metabolic data have achieved AUC values above 0.85 in several cancers, significantly outperforming single-modality biomarkers [2]. This demonstrates that capturing multifaceted biology is essential for accuracy.

Technical and Methodological Inconsistencies

Often, the simulation setup does not perfectly mirror the experimental conditions, leading to unavoidable discrepancies.

- Inadequate Mirroring of Experimental Conditions: A universal rule in validation is that the simulation setup must mirror the experiment. This includes geometry, boundary conditions, and fluid properties. Simplifications in any of these aspects can cause significant errors [3].

- Data Standardization Challenges: Inconsistencies in biomarker assays, imaging platforms, and sequencing pipelines undermine the generalizability of predictive models. The lack of international standardization frameworks hampers reproducibility across different labs and patient cohorts [2].

Computational Limitations and the "Validation Gap" in AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) represent the fastest-growing frontiers in predictive biology, yet they face a specific validation challenge.

- Performance Drop in External Validation: Many AI models, such as the SCORPIO model for predicting overall survival (AUC 0.76), perform well within their development cohort but fail to maintain accuracy when tested on independent patient populations. This problem is identified as the "validation gap" [2].

- Function-Based Screening Needs: With the rise of AI-designed proteins, traditional DNA screening methods based on sequence similarity are becoming inadequate. There is an urgent need for function-based screening standards to predict hazardous functions even from novel sequences, a key step for closing the biosecurity and validation gap [4].

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance Across Data Types

The performance of predictive models is heavily influenced by the type and number of biological data used. A large-scale empirical study on the NCI-60 cancer cell lines provides a robust framework for comparing the ability of different data types to correctly identify the tissue-of-origin for cancer cell lines [5].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Biological Data Types in Cancer Classification [5]

| Data Type | Performance at Low Number of Biomarkers | Performance at High Number of Biomarkers | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression (mRNA) | Differentiates significantly better | High performance, matched or outperformed by SNP data | Captures active state of cells; good for lineage identification |

| Protein Expression | Differentiates significantly better | High performance | Direct measurement of functional effectors |

| SNP Data | Lower performance | Matches or slightly outperforms gene/protein expression | Captures genomic variations; requires more features for high accuracy |

| aCGH (Copy Number) | Lower performance | Continues to perform worst among data types | Measures genomic amplifications/deletions |

| microRNA Data | Lower performance | Continues to perform worst among data types | Regulates gene expression; complex mapping to phenotype |

This analysis reveals that no single model or data type uniformly outperforms all others. The choice of data type and the number of biomarkers selected should be guided by the specific biological question and the constraints of the intended clinical or research application. Furthermore, the study found that certain feature-selection and classifier pairings consistently performed well across data types, suggesting that robust computational methodologies can be identified and leveraged [5].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A rigorous, methodical approach to validation is non-negotiable for transforming a computational exercise into a reliable tool. The following protocols, adapted from best practices in computational fields and systems biology, provide a roadmap for robust validation.

Protocol 1: Sourcing and Preparing Benchmark Experimental Data

Before any comparison, a high-quality, relevant benchmark dataset must be established.

- Leverage Public Databases and Classic Benchmarks: Organizations like NASA and the NIH maintain public databases with high-fidelity experimental data (e.g., the NCI-60 dataset) [5] [3]. Using these well-characterized benchmarks allows for comparison with a massive pool of existing research.

- Ensure Data Completeness and Relevance: The experimental data must be as close as possible to the simulation case. Gather comprehensive data under specific conditions, such as using mass spectrometry to quantify thousands of proteins simultaneously for proteome-level validation [1].

- Document Experimental Error: Acknowledge and document measurement errors from the experimental data. For instance, in the ONERA M6 Wing dataset, pressure tap measurements had an error of ±0.02, which must be accounted for during comparison [6].

Protocol 2: Mirroring the Experimental Setup in-Silico

The most critical step for a fair comparison is to reconstruct the exact experimental conditions within the computational model.

Table 2: Checklist for Mirroring Experimental Conditions in Computational Models [3]

| Parameter | Experimental Context | Computational Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry | Exact dimensions, including fillets or chamfers | Import/create a model with identical dimensions; avoid unjustified simplification. |

| Initial & Boundary Conditions | Inlet velocity profile, temperature, turbulence intensity | Set boundary condition types and values to match precisely. |

| Biological/Physical Properties | Constant or temperature-dependent fluid properties; protein expression levels. | Define material properties or biological parameters accordingly. Use functions for dependencies if necessary. |

| Wall/Interaction Conditions | Wall smoothness/roughness, no-slip condition, fixed temperature or heat flux. | Apply the correct boundary conditions (e.g., No-Slip, Fixed Temperature). |

| Temporal Conditions | Time-scales of the experiment, sampling frequency. | Ensure the numerical solver's time-stepping aligns with experimental dynamics. |

Protocol 3: Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison of Results

The comparison phase should blend hard numbers with a deep understanding of the underlying biology and physics.

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Plot Direct Overlays: Extract simulation data along a line or surface corresponding to the experimental measurement and plot it on the same graph as the experimental data points [6] [3].

- Calculate Error Metrics: Compute percent error for key integrated values (e.g., lift coefficient, prediction accuracy). Context matters—a 5% error might be acceptable in complex aerodynamics but not in simple pipe flow [3].

- Qualitative Analysis:

- Match Flow Structures or Biological Pathways: Place simulation contours next to experimental visualizations (e.g., Schlieren photographs, multiplex immunofluorescence images). Correctly capturing the spatial organization of immune cells or the location of a shockwave indicates the model captures the correct underlying physics or biology, even with minor numerical discrepancies [3] [2].

- Dynamic and Mechanistic Validation:

- Use a new generation of mathematical models to simulate tumor-immune interactions in real-time. These mechanistic models can classify responders vs. non-responders with up to 81% accuracy and offer a deeper understanding of dynamic resistance mechanisms [2].

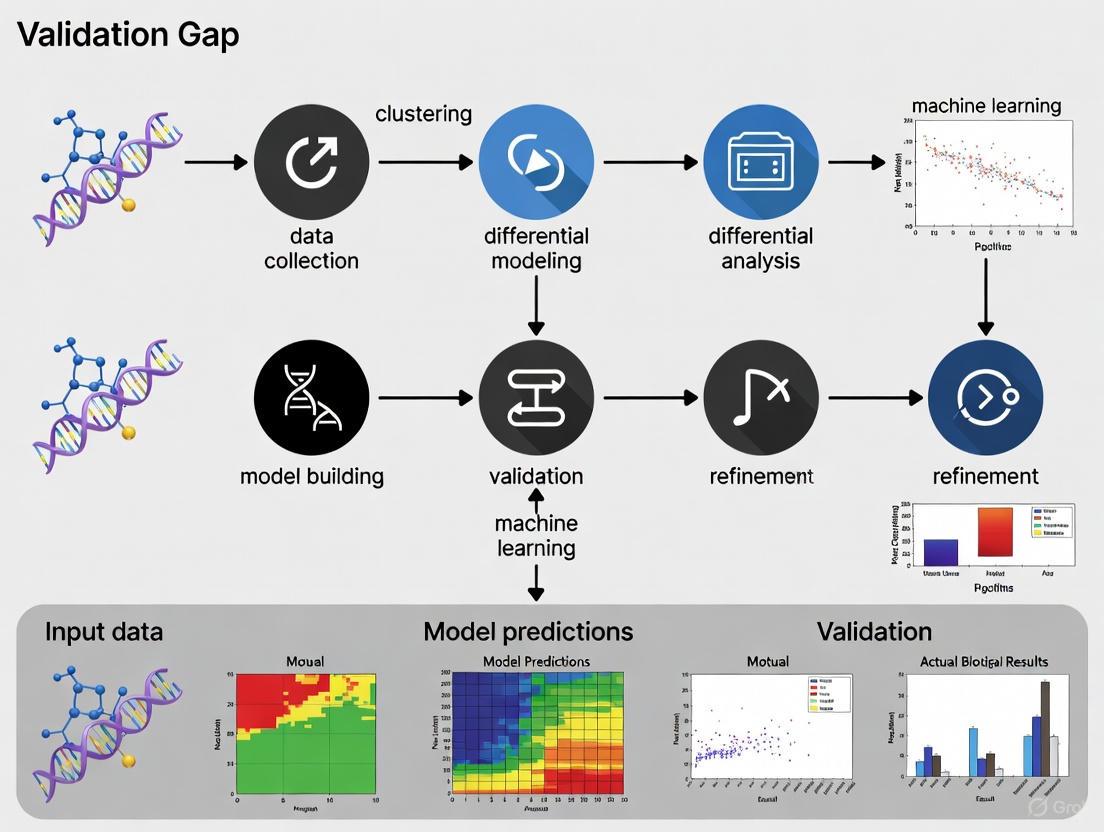

Visualization of the Multi-Modal Data Integration Workflow

Integrating diverse data types is a proven strategy to improve predictive accuracy. The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for multi-modal data integration and validation in systems biology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

Building and validating a predictive model requires a suite of wet-lab and computational tools. The table below details key resources essential for conducting the experiments and analyses described in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Model Development and Validation

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | Enables quantification of thousands of proteins simultaneously, capturing dynamic proteome changes. [1] | Proteome-level validation of predictive models. |

| Multiplex Immunofluorescence | Provides spatial profiling of the tumor microenvironment, revealing cell organization. [2] | Integrating spatial biology to improve immunotherapy response prediction. |

| SCORPIO AI Model | Analyzes multi-modal data to predict overall survival; outperforms traditional biomarkers. [2] | A tool for benchmarking new models against state-of-the-art performance. |

| Python & Scikit-learn | Provides implementations for a wide array of feature selection and classification algorithms. [5] | Building and testing custom predictive models from high-dimensional biological data. |

| PyBaMM (Python Battery MMM) | An open-source environment for simulating and validating physics-based models against experimental data. [7] | A framework for reproducible model testing and comparison, as demonstrated with battery data. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides massive computational resources required for big biological data analytics. [8] | Handling tasks like whole-genome sequence alignment and large-scale molecular dynamics. |

Troubleshooting Guide: When Simulation and Data Diverge

A mismatch between simulation and experiment is not a failure but a diagnostic opportunity. Here is a systematic troubleshooting guide based on expert analysis.

Investigate Data Quality and Model Setup:

- Re-check Input Parameters: This is the most common source of error. Verify that all biological parameters, boundary conditions, and initial states precisely match the experimental protocol. A subtle error in defining a single parameter can render results completely wrong [3].

- Re-evaluate Physical/Biological Assumptions: Did the model assume a linear response when the system is non-linear? Was a critical pathway or interaction omitted? Re-evaluating these fundamental choices is key [3] [9].

Interrogate the Computational Methodology:

- Assess Mesh/Grid Resolution and Numerical Convergence: In particle-based or spatial models, a coarse mesh is a leading cause of inaccuracy. Perform a Grid Convergence Index (GCI) study to ensure results are independent of numerical discretization [3] [9]. For non-spatial models, ensure the numerical solver has truly converged.

- Evaluate Feature Selection and Algorithm Choice: The choice of machine learning algorithm and feature selection method significantly impacts performance. Certain pairings are consistently top performers across biological data types [5]. Ensure the chosen turbulence model or classification algorithm is appropriate for the problem's physics/biology [3].

Address the "Validation Gap" in AI Models:

- Prioritize External Validation: Always test AI models on independent, external patient cohorts or datasets. This is the only way to identify and address the performance drop that characterizes the validation gap [2].

- Incorporate Functional Predictions: Move beyond sequence-based screening to function-based algorithms that can flag hazardous or novel functions, thereby closing biosecurity and performance gaps in AI-designed biologics [4].

Visualization of the Model Validation and Troubleshooting Protocol

A systematic protocol is essential for diagnosing and resolving discrepancies between simulation outputs and experimental data. The following flowchart outlines a step-by-step troubleshooting process.

The disconnect between simulation and experimental data remains a fundamental challenge in predictive systems biology. However, as demonstrated through the comparative data and protocols in this guide, this gap can be systematically addressed. The key lies in a rigorous, methodical approach that prioritizes high-quality data, meticulous setup mirroring, and comprehensive quantitative and qualitative validation. The emergence of multi-modal integration and AI, while presenting new challenges like the "validation gap," offers unprecedented opportunities to capture the complexity of biological systems.

For researchers and drug development professionals, closing this gap is critical for translation. It builds the confidence needed to move predictive models from the realm of computational exploration to reliable tools for patient stratification, drug target identification, and guiding personalized therapeutic strategies. By adopting the standards and checklists outlined here, the community can work towards a future where in-silico predictions consistently and accurately inform in-vitro and in-vivo outcomes, accelerating the pace of biomedical discovery.

The promise of predictive systems biology is to use computational models to accurately forecast complex biological behaviors, thereby accelerating therapeutic discovery and biomedical innovation. However, a significant validation gap often separates a model's performance on training data from its real-world predictive power. This gap primarily stems from three interconnected sources: database inconsistencies, missing biological annotations, and model overfitting. These issues compromise the reliability, reproducibility, and generalizability of models, posing a substantial challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. This guide objectively compares the performance of different computational approaches designed to bridge this validation gap, providing a detailed analysis of their underlying methodologies, experimental data, and practical efficacy.

Database Inconsistencies in Ortholog Prediction

Performance Comparison of Ortholog Database Evaluation Methods

Ortholog prediction is fundamental for transferring functional knowledge across species, yet different databases often yield conflicting results. A novel metric, the Signal Jaccard Index (SJI), provides an unsupervised, network-based approach to evaluate these inconsistencies [10]. The table below compares its performance against the common strategy of computing consensus orthologs.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Evaluating Ortholog Database Inconsistency

| Method Feature | Consensus Orthologs (Common Strategy) | SJI-Based Protein Network [10] |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Computes agreement across multiple databases | Applies unsupervised genome context clustering to assess protein similarity |

| Handling of Inconsistency | Introduces additional arbitrariness | Identifies peripheral proteins in the network as primary sources of inconsistency |

| Reliability Predictor | Not inherent to the method | Uses degree centrality (DC) in the network to predict protein reliability in consensus sets |

| Key Advantage | Simple to compute | Objective, avoids arbitrary parameters; DC is stable and unaffected by species selection |

Experimental Protocol: SJI Metric and Network Construction

The experimental procedure for implementing the SJI-based evaluation is as follows [10]:

- Calculate Signal Jaccard Index (SJI): Compute the SJI for protein pairs based on unsupervised genome context clustering. This metric serves as a robust measure of protein similarity, rooted in genomic data rather than database annotations.

- Construct Protein Network: Build a comprehensive protein network where nodes represent proteins and edges are weighted based on their calculated SJI similarity values.

- Analyze Network Topology: Analyze the topological features of the constructed network. Proteins located at the network's periphery are identified as the primary contributors to prediction inconsistencies.

- Assess Reliability via Degree Centrality: Calculate the degree centrality for each protein node. This metric serves as a strong, stable predictor of a protein's reliability within consensus ortholog sets.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental protocol:

Missing Annotations in Biochemical Network Models

Performance Comparison of Semantic Propagation Techniques

Missing semantic annotations in network models hinder their comparability, alignment, and reuse. Semantic propagation addresses this by inferring information from annotated, surrounding elements in the network [11]. The table below compares two primary technical approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Semantic Propagation Methods for Missing Annotations

| Method Feature | Feature Propagation (FP) | Similarity Propagation (SP) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Associates each model element with a feature vector describing its relation to biological concepts; vectors are propagated across the network. | Directly propagates pairwise similarity scores between elements from different models based on network structure. |

| Computational Load | Lower | Higher |

| Input Requirements | Requires feature vectors derived from annotations. | Can work with any initial similarity measure, not necessarily feature-based. |

| Output | Inferred feature vectors for all elements, providing an enriched description. | An inferred similarity score for element pairs, used for model alignment. |

| Typical Application | Predicting missing annotations for a single model. | Aligning two or more models directly. |

Experimental Protocol: Model Alignment via SemanticSBML

The protocol for using semantic propagation to align models and predict missing annotations with the semanticSBML tool involves the following steps [11]:

- Model Input: Provide the partially annotated Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) model(s) as input.

- Choose Propagation Method:

- For Feature Propagation (FP): Represent each element's annotations as a feature vector. The propagation allows elements to inherit semantic information from their network neighbors.

- For Similarity Propagation (SP): Define an initial direct similarity (e.g., based on existing annotations). The propagation refines this similarity by considering the similarities of connected elements.

- Execute Propagation: Run the chosen algorithm to compute inferred feature vectors (FP) or inferred similarity scores (SP) for all model elements, including non-annotated ones.

- Perform Model Alignment: Use a greedy heuristic to match elements between models based on the inferred similarities (from SP) or inferred feature vectors (from FP). Elements are grouped into tuples believed to be equivalent.

- Predict Annotations (Optional): For a sparsely annotated model, align it to a fully annotated database (e.g., BioModels). Transfer annotations from the best-matching database element to the non-annotated model element as a suggested prediction.

The logical flow of the similarity propagation method, which is particularly effective for aligning models with poor initial annotations, is shown below:

Model Overfitting in Dynamic Modeling and Immunological Applications

Performance Comparison of Robust Parameter Estimation Strategies

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying biological signal, leading to poor generalizability. This is a critical concern in dynamic modeling of biological systems and in immunological applications like vaccine response prediction [12] [13]. The table below compares standard and robustified approaches.

Table 3: Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methods to Combat Overfitting

| Method Feature | Standard Local Optimization (e.g., MultiStart) | Robust & Regularized Global Optimization [13] |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Scope | Local search, prone to getting trapped in local minima. | Efficient global optimization to handle nonconvexity and find better solutions. |

| Handling of Ill-Conditioning | Often exacerbates overfitting by finding complex, non-generalizable solutions. | Uses regularization (e.g., Tikhonov, Lasso) to penalize model complexity, reducing overfitting. |

| Parameter Identifiability | May not adequately address non-identifiable parameters. | Systematically incorporates prior knowledge and handles non-identifiability via regularization. |

| Bias-Variance Trade-off | Can result in high variance and low bias. | Aims for the best trade-off, producing models with better predictive value. |

| Key Outcome | Potentially good fit to calibration data, poor generalization. | Improved model generalizability and more reliable predictions on new data. |

Experimental Protocol: Regularized Parameter Estimation for Dynamic Models

A robust protocol for parameter estimation in dynamic models, designed to fight overfitting, combines global optimization with regularization [13].

- Problem Formulation: Define the parameter estimation as a nonlinear programming problem (NLP) with differential-algebraic constraints. The cost function (e.g., maximum likelihood) measures the mismatch between model predictions and experimental data.

- Apply Global Optimization: Use an efficient global optimization algorithm to explore the parameter space broadly. This step is crucial to avoid convergence to local minima and to find a region near the global optimum.

- Implement Regularization: Incorporate a regularization term into the cost function. This term penalizes the deviation of parameters from prior knowledge (e.g., from literature or preliminary experiments) or encourages desirable properties like parameter sparsity.

- Cross-Validation: Validate the calibrated model using a new, independent dataset that was not used for parameter estimation. This step is essential for testing the model's predictive power and ensuring that overfitting has been mitigated.

The workflow for this robust calibration strategy is as follows:

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Bridging the Validation Gap

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Utility |

|---|---|---|

| semanticSBML [11] | Open-source library and web service for model annotation and alignment. | Performs semantic propagation to predict missing annotations and align partially annotated biochemical network models. |

| BioModels Database [11] | Curated repository of published, annotated mathematical models of biological processes. | Serves as a reference database for transferring annotations via model alignment and for benchmarking. |

| Signal Jaccard Index (SJI) [10] | A metric derived from unsupervised genome context clustering. | Evaluates ortholog database inconsistency and constructs a protein network to identify error-prone predictions. |

| Regularization Algorithms [13] | Computational methods (e.g., Tikhonov, Lasso) that add a penalty to the model's cost function. | Reduces model overfitting by penalizing excessive complexity during parameter estimation, improving generalizability. |

| Global Optimization Solvers [13] | Numerical software designed to find the global optimum of nonconvex problems (e.g., metaheuristics, scatter search). | Essential for robust parameter estimation in dynamic models, helping to avoid non-physical local solutions. |

| BioPreDyn-bench Suite [14] | A suite of benchmark problems for dynamic modelling in systems biology. | Provides ready-to-run, standardized case studies for fairly evaluating and comparing parameter estimation methods. |

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions are fundamental for modeling an organism's molecular physiology, correlating its genome with its biochemical capabilities [15]. The reconstruction process translates annotated genomic data into a structured network of biochemical reactions, which can then be converted into mathematical models for simulation, most commonly using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [16] [15]. While automated reconstruction tools have been developed to accelerate this process, a significant validation gap persists between the models generated by these automated pipelines and biological reality. This case study examines the specific limitations of automated reconstruction methods, quantifying their performance against manually curated benchmarks and outlining methodologies to bridge this accuracy gap. This validation gap presents a critical challenge for researchers in systems biology and drug development who rely on these models for predictive analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Reconstruction Accuracy

Evaluating the output of automated reconstruction tools requires rigorous experimental design that compares their predictions against high-quality, manually curated models and experimental data. The following protocols outline standard methodologies used in the field.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Against Manually Curated Models

This protocol assesses the ability of automated tools to recreate known, high-quality metabolic networks [17] [18].

- Input Preparation: Select a target organism with a high-quality, manually curated genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., Lactobacillus plantarum or Bordetella pertussis) [17].

- Tool Execution: Input the genome sequence of the target organism into multiple automated reconstruction platforms (e.g., CarveMe, ModelSEED, RAVEN, AuReMe) [17].

- Model Comparison: Systematically compare the output draft networks from each tool against the manually curated model. Key comparison metrics include:

- Reaction Recall: The proportion of reactions in the manual model correctly identified by the automated tool.

- Reaction Precision: The proportion of reactions in the automated model that are present in the manual model.

- Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association Accuracy: The correctness of gene assignments to reactions [17].

- Functional Assessment: Use flux balance analysis to test if the automated model can produce all biomass precursors and achieve growth under defined conditions, similar to the manual model [18].

Protocol 2: Validation Against Experimental Phenotype Data

This protocol tests the predictive power of automated models against empirical data [19].

- Data Curation: Compile large-scale phenotypic data for test organisms. This includes:

- Carbon Source Utilization: Data on which carbon sources support microbial growth.

- Enzyme Activity Assays: Results from biochemical tests (e.g., from the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase - BacDive).

- Gene Essentiality Data: Information on genes required for growth under specific conditions [19].

- Model Prediction: Use the automated models to simulate the curated phenotypes (e.g., predict growth on different carbon sources or the outcome of gene knockouts).

- Performance Calculation: Calculate standard performance metrics such as False Negative Rate and True Positive Rate by comparing predictions against experimental results [19].

The diagram below illustrates the workflow for a comparative assessment of reconstruction tools, integrating both benchmarking approaches.

Performance Comparison: Automated Tools vs. Manual Curation

Systematic assessments reveal that while automated tools offer speed, they often trail manual curation in accuracy and biological fidelity.

Quantitative Accuracy Metrics

The following table summarizes key performance indicators from published benchmark studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Automated Reconstruction Tools

| Assessment Metric | Manual Curation (Benchmark) | Automated Tools (Range) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gap-Filling Accuracy (Precision) | Not Applicable (Reference) | 66.6% (GenDev on B. longum) [18] | Automated gap-filling introduced false-positive reactions; manual review is essential. |

| Gap-Filling Accuracy (Recall) | Not Applicable (Reference) | 61.5% (GenDev on B. longum) [18] | Automated methods missed ~40% of reactions identified by human experts. |

| Enzyme Activity Prediction (True Positive Rate) | Not Applicable (Reference) | 27% - 53% (CarveMe: 27%, ModelSEED: 30%, gapseq: 53%) [19] | Performance varies significantly between tools; gapseq showed notably higher accuracy. |

| Reaction Network Completeness | Varies by model (Reference) | Variable and tool-dependent [17] | No single tool outperforms all others in every defined feature. |

Limitations in Pathway and Context Prediction

Beyond quantitative metrics, automated tools struggle with specific qualitative aspects:

- Incorrect Inference of Metabolic Pathways: Automated reconstructions can generate manifold paths that require expert manual verification to accept some and reject most others [20]. This is often due to over-reliance on genomic annotations without sufficient biochemical context.

- Lack of Organism-Specific Context: Parsimony-based gap-fillers may select reactions from a database at random when multiple, equally "costed" options exist, potentially missing the biologically relevant one. A case study on B. longum showed an automated tool selecting one of four possible reactions for L-asparagine synthesis, while manual curation correctly identified the specific reaction based on the presence of other pathway enzymes [18].

- Dependence on Input Database Quality: The accuracy of any tool is constrained by the completeness and quality of the reaction database it uses. Inconsistent atom mapping or energy-generating futile cycles in databases can lead to functionally incorrect models [19] [18].

The diagram below outlines the specific stages where errors are introduced during automated reconstruction and how they are typically addressed in manual curation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Databases

Successful metabolic reconstruction, whether automated or manual, relies on a core set of databases and software tools. The table below catalogs essential resources for the field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Metabolic Reconstruction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Reconstruction | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG [15] | Database | Provides reference information on genes, proteins, reactions, and pathways. | Serves as a primary data source for many automated tools; a standard for pathway analysis. |

| MetaCyc [17] [15] | Database | A curated encyclopedia of experimentally defined metabolic pathways and enzymes. | Used as a high-quality reference database for reconstruction and manual curation. |

| BiGG Models [17] [15] | Database | A knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. | Provides access to existing curated models for use as templates or benchmarks. |

| BRENDA [15] | Database | A comprehensive enzyme information system. | Used to verify enzyme function and organism-specific enzyme activity. |

| Pathway Tools [17] [15] | Software Suite | Assists in building, visualizing, and analyzing pathway/genome databases. | Used for both automated and semi-automated reconstruction and curation. |

| CarveMe [17] [19] | Software Tool | Automated reconstruction using a top-down approach from a universal model. | Known for generating "ready-to-use" models for FBA; often used in performance comparisons. |

| ModelSEED [17] [19] | Software Tool | Web-based resource for automated reconstruction and analysis of metabolic models. | Often benchmarked for phenotype prediction accuracy. |

| gapseq [19] | Software Tool | Automated tool for predicting metabolic pathways and reconstructing models. | Recently developed tool shown to improve prediction accuracy for bacterial phenotypes. |

This case study demonstrates that a significant validation gap exists between automated and manually curated metabolic reconstructions. Quantitative benchmarks reveal that even state-of-the-art automated tools can exhibit low precision and recall in gap-filling and show variable performance in predicting enzymatic capabilities [18] [19]. The core limitations stem from a lack of biological context, inherent database inaccuracies, and the inability of algorithms to incorporate the expert knowledge that guides manual curation [20] [21] [18].

To bridge this gap, the future of metabolic reconstruction lies in hybrid approaches that integrate the scalability of automation with the precision of manual curation. Promising strategies include leveraging manually curated models as templates for related organisms [21], developing improved algorithms that incorporate more biological evidence (e.g., as seen in gapseq [19]), and establishing more robust standardized protocols for model validation. For researchers in drug development and systems biology, these findings underscore the critical importance of critically evaluating and manually refining automatically generated models before using them for critical predictions.

Unanticipated off-target effects represent a critical challenge in drug discovery, directly contributing to high rates of clinical attrition and the failure of promising therapeutic candidates. These effects, defined as a drug's action on gene products other than its intended target, are a principal cause of adverse reactions and toxicity that derail development programs, particularly in Phase II and III trials [22] [23]. The validation gap in predictive systems biology—where computational models fail to generalize outside their development cohort—severely limits our ability to foresee these effects, resulting in costly late-stage failures [2]. This guide compares the primary methodological approaches for predicting off-target effects, evaluates their performance in anticipating clinical attrition, and details the experimental protocols that underpin this critical field. As drug discovery expands into novel modalities like PROTACs, oligonucleotides, and cell/gene therapies, each with unique off-target profiles, robust and predictive preclinical profiling becomes indispensable for improving the dismal likelihood of approval (LOA), which stands at just 5-7% for small molecules [24] [25].

Quantifying the Clinical Attrition Problem

High attrition rates, especially in Phase II, plague drug development across all modalities. The table below summarizes global clinical attrition data, illustrating the stark reality of drug development failure.

Table 1: Global Clinical Attrition Rates by Drug Modality (2005-2025)

| Modality | Phase I → II Success | Phase II → III Success | Phase III → Approval Success | Overall LOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules | 52.6% | 28.0% | ~57.0% | ~6.0% |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | 54.7% | Information Missing | 68.1% | 12.1% |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | 41.0% | 42.0% | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Protein Biologics (non-mAbs) | 51.6% | Information Missing | 89.7% | 9.4% |

| Peptides | 52.3% | Information Missing | Information Missing | 8.0% |

| Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | 61.0% | Information Missing | Information Missing | 5.2% |

| Oligonucleotides (RNAi) | ~70.0% | Information Missing | ~100% | 13.5% |

| Cell & Gene Therapies (CGTs) | 48-52% | Information Missing | Information Missing | 10-17% |

Data compiled from industry analyses (Biomedtracker/PharmaPremia) show that despite differences in modality, Phase II is the most significant hurdle, with the majority of programs failing at this stage due to efficacy and safety concerns, the latter often linked to unanticipated off-target effects [25].

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Methodologies for Off-Target Effects

A range of computational and experimental methods has been developed to predict off-target effects early in the drug discovery process. Their performance and applicability vary significantly.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Off-Target Prediction and Profiling Methods

| Methodology | Key Principle | Reported Performance | Primary Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In silico Bayesian Models [22] | Builds probabilistic models from chemical structure and known pharmacology data to predict binding. | 93% ligand detection (IC₅₀ ≤10µM); 94% correct classification rate. | Early-stage compound screening and triage. | Highly dependent on the quality and breadth of training data. |

| Direct Side-Effect Modeling [22] | Predicts adverse drug reactions directly from chemical structure, bypassing mechanistic knowledge. | 90% of known ADRs detected; 92% correct classification. | Late-stage lead optimization and safety profiling. | Model interpretability and back-projection to structure can be challenging. |

| Comprehensive Experimental Mapping (EvE Bio) [23] | Empirically tests ~1,600 FDA-approved drugs against a vast panel of human cellular receptors. | Provides direct, empirical interaction data, not a prediction. Creates a foundational dataset. | Drug repurposing, polypharmacology, and model validation. | Resource-intensive; limited to existing approved drugs and selected receptors. |

| AI/Machine Learning Models [2] | Integrates high-dimensional clinical, molecular, and imaging data to uncover complex patterns. | AUC of 0.76 for overall survival (SCORPIO model); 81% predictive accuracy (LORIS model). | Personalized therapy prediction, particularly in oncology. | Prone to a "validation gap," with performance dropping on external datasets. |

The convergence of computational and empirical methods is key to closing the validation gap. For instance, the large-scale experimental data generated by efforts like EvE Bio provides the ground-truth data needed to train and validate more robust AI and Bayesian models [22] [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Off-Target Profiling

Protocol 1: In silico Bayesian Model Building for Target Prediction

This protocol outlines the creation of computational models to predict a compound's binding to preclinical safety pharmacology (PSP) targets [22].

- Data Curation: Compile a comprehensive dataset of chemical structures and their associated in vitro binding affinities (e.g., IC₅₀ values) for a panel of 70+ PSP-related targets.

- Descriptor Calculation: For each compound, calculate numerical descriptors that encode its chemical structure and properties.

- Model Training: For each PSP target, train a separate Bayesian machine learning model. The model learns the probabilistic relationship between the chemical descriptors and the likelihood of binding.

- Model Validation: Validate model performance using held-out test data not seen during training. Key metrics include sensitivity (ability to detect true binders) and overall correct classification rate.

- Deployment & Interpretation: Use the trained models to screen virtual or real compound libraries. The features of the model are interpretable and can be back-projected to chemical structure, suggesting which structural motifs contribute to off-target binding [22].

Protocol 2: Large-Scale Empirical Off-Target Mapping

This protocol describes the systematic, experimental approach to mapping drug-target interactions, as employed by organizations like EvE Bio [23].

- Receptor Panel Selection: Curate a diverse panel of hundreds of clinically important human cellular receptors representing a wide range of target classes (e.g., GPCRs, kinases, ion channels).

- Compound Library Curation: Assemble a library of approximately 1,600 FDA-approved drugs.

- High-Throughput Binding Assays: Subject each drug in the library to a standardized, high-throughput binding assay against every receptor in the panel. This measures the strength of interaction (e.g., binding affinity) between the drug and receptor.

- Data Collection and Quality Control: Systematically collect the interaction data, implementing rigorous quality controls to ensure reproducibility.

- Data Integration and Curation: Compile the results into a centralized, searchable database that maps every drug to all its detected receptor interactions, both intended (on-target) and unintended (off-target).

- Data Release: The final dataset is released under a non-commercial, creative commons license (CC-NA) for academic use, and is available for commercial licensing [23].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this large-scale empirical mapping process.

Diagram 1: Empirical off-target mapping workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and resources used in the experimental profiling of off-target effects.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Off-Target Effect Profiling

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Preclinical Safety Pharmacology (PSP) Target Panel [22] | A curated set of 70+ in vitro binding assays (e.g., for GPCRs, kinases) used to screen compounds for potential adverse effects. |

| FDA-Approved Drug Library [23] | A comprehensive collection of ~1,600 approved small molecule drugs, used for large-scale repurposing and off-target screening. |

| Human Cellular Receptor Library [23] | A diverse panel of hundreds of cloned human receptors, enabling systematic profiling of compound interactions. |

| Positional Weight Matrix (PWM) [26] | A de facto standard model for transcription factor (TF) DNA binding specificity, used in benchmarking studies. |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Enables the quantification of thousands of proteins simultaneously for proteome-wide validation of model predictions [1]. |

Analysis of the Validation Gap in Predictive Systems Biology

A persistent "validation gap" undermines the reliability of predictive models in biology. This gap is the failure of models, including those for off-target effects and therapy response, to maintain their performance when applied to independent, external datasets [2]. For example, while AI models for immunotherapy response can achieve AUCs >0.9 in controlled research settings, their performance often drops significantly in real-world clinical cohorts [2].

The causes of this gap are multifaceted and create a logical flow of challenges, from data input to real-world application, as shown below.

Diagram 2: The validation gap challenge in predictive modeling.

Closing this validation gap requires a multi-faceted approach, including the generation of large-scale, high-quality empirical datasets (like those from EvE Bio) for model training and benchmarking [26] [23], the adoption of international data standardization frameworks [2], and rigorous external validation practices before clinical implementation [26] [2].

The integration of multi-omics data represents a transformative frontier in systems biology, promising a comprehensive understanding of how molecular interactions across biological scales govern phenotype manifestation. Despite unprecedented growth in the field—with multi-omics scientific publications more than doubling in just two years (2022–2023)—a significant validation gap persists between computational predictions and physiological reality [27]. Current machine learning methods primarily establish statistical correlations between genotypes and phenotypes but struggle to identify physiologically significant causal factors, limiting their predictive power for unprecedented perturbations [28] [29]. This gap stems from several interconnected challenges: scarcity of labeled data for supervised learning, generalization across biological domains and species, disentangling causation from correlation, and the inherent difficulties in integrating heterogeneous data types with varying dimensions, measurement units, and noise structures [28] [30].

The validation challenge is particularly acute in translational applications such as drug development, where over 90% of approved medications originated from phenotype-based discovery, yet target-based approaches dominated by artificial intelligence (AI) often fail to produce clinically effective treatments [28] [31]. Bridging this gap requires not only advanced computational methods but also robust experimental designs, standardized reference materials, and biological interpretability built into model architectures. This review examines emerging approaches that address these challenges through innovative integration strategies, with particular focus on their validation frameworks and comparative performance in predictive systems biology.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

AI-Driven Multi-Scale Predictive Modeling

Overview and Methodology: AI-powered biology-inspired multi-scale modeling represents a paradigm shift from correlation-based to causation-aware predictive modeling. This framework integrates multi-omics data across three critical dimensions: (1) biological levels (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics), (2) organism hierarchies (cell, tissue, organ, organism), and (3) species (model organisms to humans) [28] [29] [32]. The methodology employs endophenotypes—molecular intermediates such as RNA expression, protein modifications, and metabolite concentrations—as mechanistic bridges connecting genetic determinants to organismal phenotypes [28]. Unlike conventional machine learning that treats biological systems as black boxes, this approach structures AI architectures around known biological hierarchies and prior knowledge, enabling more physiologically realistic predictions.

Experimental Validation and Performance: Validation of this approach utilizes perturbation functional omics profiling from resources like TCGA, LINCS, DepMap, and scPerturb which provide labeled data for supervised learning [28]. These datasets systematically capture molecular responses to genetic and chemical perturbations, creating ground truth benchmarks for model assessment. For example, scPerturb integrates 44 public single-cell perturbation datasets with CRISPR and drug interventions, providing single-cell resolution for quantifying heterogeneous cellular responses [28]. The Table 1 summarizes the experimental data resources available for developing and validating multi-omics integration models.

Table 1: Key Data Resources for Multi-Omics Model Validation

| Resource | Perturbation Types | Molecular Profiling | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA [28] [33] | Drug treatments | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic | Cancer biomarker identification, therapeutic target discovery |

| LINCS [28] | Drug, CRISPR-Cas9, ShRNA | Transcriptomic, proteomic, kinase binding, cell viability | Cellular signature analysis, drug mechanism of action |

| DepMap [28] [33] | CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi, drug | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, drug sensitivity | Cancer dependency mapping, drug response prediction |

| scPerturb [28] | CRISPR, cytokines, drugs | Single-cell RNA-seq, proteomic, epigenomic | Single-cell perturbation response, cellular heterogeneity |

| PharmacoDB [28] | Drug | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic | Drug sensitivity analysis, personalized medicine |

| Quartet Project [34] | Built-in family pedigree | DNA, RNA, protein, metabolites | Multi-omics reference materials, data integration QC |

Advantages and Limitations: The key advantage of AI-driven multi-scale modeling is its ability to generalize predictions across biological contexts and identify causal mechanisms rather than mere correlations [28] [31]. The framework shows particular promise for phenotype-based drug discovery, where perturbation functional omics provides quantitative, mechanistic readouts for compound screening [28]. However, limitations include high computational complexity, dependence on extensive and diverse training data, and challenges in interpreting complex network architectures. Validation remains particularly difficult for human-specific predictions where in vivo data is scarce or ethically constrained.

Reference Material-Based Frameworks for Validation

Overview and Methodology: The Quartet Project addresses a fundamental challenge in multi-omics integration: the lack of ground truth for method validation [34]. This approach provides publicly available suites of multi-omics reference materials derived from immortalized cell lines from a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twin daughters). The methodology employs a ratio-based profiling approach that scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to a concurrently measured common reference sample, enabling reproducible and comparable data across batches, laboratories, and platforms [34]. The family structure provides built-in truth defined by genetic relationships and central dogma information flow from DNA to RNA to protein.

Experimental Validation and Performance: The Quartet reference materials have been comprehensively characterized across multiple platforms: 7 DNA sequencing platforms, 2 RNA-seq platforms, 9 proteomics platforms, and 5 metabolomics platforms [34]. Performance is quantified using two specialized metrics: (1) sample classification accuracy (ability to distinguish the four individuals and three genetic clusters), and (2) central dogma conformity (correct identification of cross-omics feature relationships following DNA→RNA→protein information flow). The ratio-based method demonstrates superior reproducibility compared to absolute quantification, which is identified as the root cause of irreproducibility in multi-omics measurement [34].

Table 2: Quartet Project Reference Materials and Applications

| Reference Material | Source | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Reference | B-lymphoblastoid cell lines | Mendelian inheritance patterns, variant calling validation | Genomic technology proficiency testing |

| RNA Reference | Matched to DNA samples | Expression quantification, splice variant analysis | Transcriptomic platform benchmarking |

| Protein Reference | Same cell lines as nucleic acids | Post-translational modifications, abundance measurements | Proteomic method validation |

| Metabolite Reference | Same cell lines as other omics | Small molecule profiles, pathway analysis | Metabolomic standardization |

Advantages and Limitations: The Quartet framework provides an essential validation tool for closing the verification gap in multi-omics integration, offering objective quality control metrics and reference standards for technology benchmarking [34]. Its ratio-based approach facilitates integration across diverse datasets and platforms. Limitations include potential context-specific performance (e.g., cancer vs. non-cancer applications) and the challenge of extending insights to more complex tissues and clinical samples. Nevertheless, it represents a crucial step toward standardized validation in multi-omics research.

Biologically Interpretable Neural Networks

Overview and Methodology: Visible neural networks represent an emerging approach that embeds prior biological knowledge into network architectures to enhance both prediction accuracy and interpretability [35]. These networks structure layers according to biological hierarchies—connecting input features to genes, genes to pathways, and pathways to phenotypes—making the decision-making process transparent and biologically meaningful [35]. In one implementation, multi-omics data (transcriptomics and methylomics) are integrated at the gene level, with CpG methylation sites annotated to genes based on genomic distance and combined with expression data in the gene layer [35].

Experimental Validation and Performance: This approach has been validated using the BIOS consortium dataset (N=2940) for predicting smoking status, age, and LDL levels [35]. In cohort-wise cross-validation, the method demonstrated consistently high performance for smoking status prediction (mean AUC: 0.95), with interpretation revealing biologically relevant genes such as AHRR, GPR15, and LRRN3 [35]. Age was predicted with a mean error of 5.16 years, with genes COL11A2, AFAP1, and OTUD7A consistently predictive. For both regression tasks, multi-omics networks improved performance, stability, and generalizability compared to single-omic networks [35]. The Table 3 summarizes the performance metrics across different prediction tasks.

Table 3: Performance of Biologically Interpretable Neural Networks on Multi-Omics Data

| Prediction Task | Performance Metric | Key Predictive Features | Generalizability Across Cohorts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking Status | AUC: 0.95 (95% CI: 0.90-1.00) | AHRR, GPR15, LRRN3 methylation | High consistency across 4 cohorts |

| Subject Age | Mean error: 5.16 years (95% CI: 3.97-6.35) | COL11A2, AFAP1, OTUD7A expression | Moderate variability between cohorts |

| LDL Levels | R²: 0.07 (single cohort) | Complex multi-omic interactions | Limited generalizability across cohorts |

Advantages and Limitations: The primary advantage of visible neural networks is their ability to combine predictive power with biological interpretability, generating testable hypotheses about mechanistic relationships [35]. The structured architecture also regularizes the model, reducing overfitting and improving generalization across cohorts. Limitations include dependence on accurate prior knowledge annotations, potentially missing novel biological relationships not captured in existing databases, and sensitivity to weight initializations that can affect interpretation stability [35].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Standardized Workflow for Multi-Omics Study Design

Recent research has identified nine critical factors that fundamentally influence multi-omics integration outcomes, providing an evidence-based framework for experimental design [30]. These factors are categorized into computational aspects (sample size, feature selection, preprocessing strategy, noise characterization, class balance, number of classes) and biological aspects (cancer subtype combinations, omics combinations, clinical feature correlation). Benchmark tests across ten cancer types from TCGA revealed that robust performance requires: ≥26 samples per class, selection of <10% of omics features, sample balance under 3:1 ratio, and noise levels below 30% [30]. Feature selection alone improved clustering performance by 34%, highlighting its critical importance in study design.

Protocol for Cross-Species Multi-Omics Integration

Integrating multi-omics data across species requires specialized methodologies to address evolutionary divergence while leveraging conserved biological mechanisms [28] [31]. The protocol involves: (1) Orthology mapping using standardized gene annotation databases, (2) Conserved pathway identification focusing on evolutionarily stable biological processes, (3) Cross-species normalization to account for technical and biological variations, and (4) Transfer learning where models pre-trained on model organisms are fine-tuned with human data [28]. This approach is particularly valuable for drug discovery, where model organisms provide perturbation response data that can be translated to human contexts through multi-omics alignment [31].

Visualization of Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

Workflow for Reference Material-Based Multi-Omics Integration

Quartet Project Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

Architecture of Biologically Interpretable Neural Networks

Visible Neural Network Architecture

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project references [34] | Method validation, cross-platform standardization | Built-in ground truth from family pedigree |

| Data Repositories | TCGA, ICGC, CCLE, CPTAC [28] [33] | Model training, benchmarking, validation | Clinical annotations, multiple cancer types |

| Perturbation Databases | LINCS, DepMap, scPerturb [28] | Causal inference, mechanism of action studies | Genetic and chemical perturbations |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GenNet, P-net, MOFA [35] | Data integration, visualization, interpretation | Biologically informed architectures |

| Quality Control Metrics | Mendelian concordance, SNR, classification accuracy [34] | Performance assessment, method selection | Objective benchmarking criteria |

The integration of multi-omics data for holistic model building represents one of the most promising avenues for advancing predictive systems biology, yet significant challenges remain in validation and translational application. The emerging approaches discussed—AI-driven multi-scale modeling, reference material frameworks, and biologically interpretable neural networks—each contribute distinct strategies for addressing the validation gap. The AI-driven framework excels in cross-domain generalization and causal inference, reference materials provide essential ground truth for method benchmarking, and visible neural networks offer unprecedented interpretability while maintaining predictive power.

The future of multi-omics integration lies in combining the strengths of these approaches—developing biologically informed AI models validated against standardized reference materials and interpreted through transparent architectures. As these methodologies mature and converge, they hold immense potential for illuminating fundamental principles of biology and accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets, biomarkers, and personalized treatment strategies for presently intractable diseases. Critical to this progress will be continued development of robust validation frameworks that bridge the gap between computational predictions and physiological reality, ultimately fulfilling the promise of multi-omics integration in predictive systems biology.

Advanced Methodologies for Building Biologically Relevant Predictive Models

Predictive modeling in systems biology seeks to translate mathematical abstractions of biological systems into reliable tools for understanding cellular behavior, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development [36] [1]. A persistent challenge, however, is the validation gap – the discrepancy between a model's theoretical predictions and its real-world biological accuracy. This gap often originates during the creation of genome-scale metabolic models, which are typically derived from annotated genomes and are invariably incomplete, lacking fully connected metabolic networks due to undetected enzymatic functions [18]. Gap filling, the computational process of proposing additional reactions to enable production of all essential biomass metabolites, is therefore a critical step in making these models biologically plausible and functionally useful.

Traditionally, automated gap filling has relied on parsimony-based principles, which seek minimal sets of reactions to connect metabolic networks. However, these methods can propose biochemically inaccurate solutions and struggle with numerical instability [18]. Emerging likelihood-based approaches offer a more statistically rigorous framework by directly quantifying parameter and prediction uncertainty, propagating measurement errors through model predictions, and providing confidence intervals for model outputs [37] [38]. This guide compares these methodological paradigms, providing experimental data and protocols to help researchers select appropriate strategies for bridging the validation gap in their predictive systems biology research.

Methodological Comparison: Parsimony vs. Likelihood-Based Approaches

Core Principles and Implementation

Parsony-based gap filling operates on the principle of metabolic frugality, seeking the smallest number of non-native reactions required to enable network functionality, typically using Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) solvers. In practice, tools like the GenDev algorithm within Pathway Tools identify minimum-cost solutions to complete metabolic networks, often using reaction databases like MetaCyc as candidate pools [18].

In contrast, likelihood-based approaches utilize the prediction profile likelihood to quantify how well different model predictions or parameter values agree with experimental data. This method performs constraint optimization of the likelihood function for fixed prediction values, effectively testing the agreement of predicted values with existing measurements. The resulting confidence intervals accurately reflect parameter uncertainty and can identify non-observable model components [37]. This framework is particularly valuable for dynamic models of biochemical networks where parameters are estimated from experimental data and nonlinearity hampers uncertainty propagation [37].

Experimental Performance Comparison

A direct comparison of parsimony-based automated gap filling versus manually curated solutions reveals significant accuracy differences. In a study constructing a metabolic model for Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum JCM 1217, researchers evaluated the performance of the GenDev gap filler against expert manual curation [18].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Gap-Filling Approaches

| Metric | Parsimony-Based (GenDev) | Manually Curated Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reactions Added | 12 (10 minimal after analysis) | 13 |

| True Positives | 8 | 13 |

| False Positives | 4 | 0 |

| False Negatives | 5 | 0 |

| Recall | 61.5% | 100% |

| Precision | 66.6% | 100% |

The analysis revealed several critical limitations of the parsimony approach. The GenDev solution was not minimal – two reactions could be removed while maintaining functionality, indicating numerical precision issues with the MILP solver. Furthermore, several proposed reactions were biochemically implausible for the organism's anaerobic lifestyle, highlighting how purely mathematical solutions may lack biological fidelity [18].

Likelihood-based methods address these limitations by incorporating statistical measures of confidence and compatibility with experimental data. In parameter estimation for dynamic models, maximum likelihood approaches have demonstrated 4x greater accuracy and required 200x less computational time compared to simulation-based methods [39]. This efficiency gain is particularly valuable for large-scale models common in systems biology research.

Table 2: Technical Characteristics of Gap-Filling Approaches

| Characteristic | Parsimony-Based Approach | Likelihood-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function | Minimal reaction count | Maximum likelihood agreement with data |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Limited | Comprehensive (profile likelihood) |

| Biological Context | Often ignored | Incorporates taxonomic range, directionality |

| Numerical Stability | MILP solver precision issues | Robust optimization frameworks |

| Handling Non-identifiable Parameters | Poor | Excellent (interpreted as non-observability) |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate | High (requires statistical expertise) |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Protocol for Parsimony-Based Gap Filling

The following protocol was used in the B. longum gap-filling evaluation [18]:

- Input Preparation: Start with a gapped Pathway/Genome Database (PGDB) containing the predicted reactome and metabolic pathways derived from genome annotation.

- Growth Requirements Definition: Specify the complete set of biomass metabolites (53 in the B. longum study) and nutrient compounds available to the model.

- Gap Analysis: Use flux balance analysis (FBA) to identify which biomass metabolites cannot be produced from the available nutrients.

- Reaction Candidate Pool: Access a biochemical reaction database (e.g., MetaCyc) containing known metabolic reactions with taxonomic range and directionality information.

- Optimization Execution: Run the GenDev algorithm or similar parsimony-based gap filler to identify the minimum-cost set of reactions to enable production of all biomass metabolites.

- Solution Validation: Iteratively test the necessity of each added reaction by removing it and rechecking growth capability using FBA.

Protocol for Likelihood-Based Assessment

For likelihood-based uncertainty quantification in dynamic models, the following methodology is recommended [37]:

- Model Specification: Define the dynamic model structure, typically as a system of ordinary differential equations: ẋ(t) = f(x, p, u), where p represents model parameters and u represents experimental perturbations.

- Observable Definition: Specify the mapping from model states to measurable quantities: y(t) = g(x(t), s_obs) + ε, where ε represents measurement error.

- Likelihood Function Calculation: Compute the log-likelihood for the model parameters given experimental data, typically assuming Gaussian errors: -2LL(y\|θ) = Σi [yi - F(t_i, u, θ)]²/σ² + constant.

- Prediction Profile Likelihood: For a specific prediction z = F(Dpred, θ), optimize the likelihood over parameters satisfying the constraint F(Dpred, θ) = z: PPL(z) = max{θ∈{θ\|F(Dpred, θ)=z}} LL(y\|θ).

- Confidence Interval Calculation: Determine prediction confidence intervals by thresholding the prediction profile likelihood: PCIα(Dpred\|y) = {z \| -2PPL(z) ≤ -2LL*(y) + icdf(χ₁², α)}.

Visualization of Method Workflows

Likelihood-Based Gap Filling and Validation Framework

This workflow illustrates how likelihood-based approaches integrate statistical rigor throughout the gap-filling process, from initial model assessment to experimental validation.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Advanced Gap Filling

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools with MetaFlux | Metabolic modeling and parsimony-based gap filling | Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction [18] |

| Data2Dynamics (Matlab) | Parameter estimation and uncertainty analysis | Likelihood-based assessment and prediction profiles [37] [38] |

| R/Bioconductor | Statistical computing and multi-omics analysis | General statistical analysis for systems biology [40] |

| CellDesigner | Graphical modeling of biological networks | Model creation and visualization [40] |

| BioModels Database | Repository of mathematical models | Model sharing and validation [40] |

| PyTorch/TensorFlow | Automatic differentiation frameworks | Efficient maximum likelihood estimation [39] |

| STRINGS, KEGG, Reactome | Pathway databases and interaction networks | Biological context for candidate reactions [40] [41] |

The transition from parsimony-based to likelihood-based gap filling represents a significant methodological evolution in predictive systems biology. While parsimony approaches provide computationally efficient solutions, their limited statistical foundation and susceptibility to biochemical inaccuracy (evidenced by 61.5% recall and 66.6% precision rates) present substantial limitations for rigorous model validation [18].

Likelihood-based approaches, through the prediction profile likelihood framework, offer comprehensive uncertainty quantification, robust handling of non-identifiable parameters, and statistically accurate confidence intervals for model predictions [37]. The implementation of these methods in open-source toolboxes like Data2Dynamics makes them increasingly accessible to the research community [38].

For researchers and drug development professionals addressing the validation gap in predictive modeling, we recommend a hybrid approach: using parsimony-based methods for initial network completion followed by likelihood-based assessment for rigorous statistical validation. This combined strategy leverages the computational efficiency of parsimony methods while incorporating the statistical rigor needed for robust, biologically faithful models capable of generating reliable predictions for therapeutic development and basic biological discovery.

The accurate assessment of an individual's biological age (BA) is a cornerstone of predictive systems biology, offering profound insights into healthspan, disease risk, and mortality. However, a significant validation gap persists between model development and their proven utility in predicting clinically relevant outcomes. Many existing BA estimation models are anchored to chronological age (CA) and trained on homogeneous cohorts, limiting their generalizability and clinical applicability for risk stratification [42]. The emergence of transformer-based architectures represents a paradigm shift, directly addressing this gap by integrating multifaceted health data, including morbidity and mortality, to produce BA estimates with superior prognostic power and clinical relevance.

Performance Benchmarking: Transformer Models vs. Established Alternatives

Extensive benchmarking studies demonstrate that transformer-based models consistently outperform conventional biological age estimation methods, particularly in predicting adverse health outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Biological Age Estimation Models in Predicting Mortality

| Model Type | Data Modality | Key Performance Metric | Result | Context / Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer BA-CA Gap Model [42] | Routine clinical checkups (41-88 features) | Mortality Risk Stratification | Stronger discrimination in men; clear trend in women | 151,281 adults, 2003-2020 |

| Gradient Boosting Model [43] [44] | 27 clinical factors from checkups | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | 4.219 | 28,417 super-controls |

| LLM-based BA Model [45] | Health examination reports | Concordance Index (C-index) for All-Cause Mortality | 0.757 (95% CI 0.752-0.761) | >10 million participants across 6 cohorts |

| CT-Based Biological Age (CTBA) Model [46] | Automated CT biomarkers | 10-Year AUC for Longevity | 0.880 | 123,281 adults (mean age 53.6) |

| Demographics Model (Age, Sex, Race) [46] | Chronological Age, Sex, Race | 10-Year AUC for Longevity | 0.779 | Same cohort as CTBA model |

| Klemera and Doubal's Method [42] | Limited clinical parameters | Mortality Risk Stratification | Underperformed transformer model | Comparative study on 151,281 adults |

Table 2: Model Performance in Discriminating Health Status

| Model Type | Ability to Distinguish Normal, Pre-disease, Disease | Key Strengths | Interpretability Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer BA-CA Gap Model [42] [47] | Excellent, with a clear BA gap gradient | Integrates morbidity/mortality; superior risk stratification | Model attention mechanisms |

| Gradient Boosting Model [43] [44] | Not explicitly tested for this spectrum | High predictive accuracy (R²=0.967) in healthy cohorts | SHAP analysis identifies key markers (kidney function, HbA1c) |

| LLM-based BA Model [45] | Strongly associated with aging-related phenotypes | Predicts 270 disease risks; organ-specific aging assessment | Interpretability analyses of decision-making process |

| CT-Based Biological Age (CTBA) Model [46] | N/A (focused on longevity) | Phenotypic; opportunistically derived from existing CTs | Explainable AI algorithms; biomarker contribution quantified |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A critical step in validating any predictive model is a rigorous and transparent experimental protocol. The following methodologies from key studies highlight the structured approach required to minimize the validation gap.

- Cohort Design: A retrospective analysis of 151,281 adults aged ≥18 from the Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center (2003-2020). Participants were classified into normal, predisease, and disease groups based on comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia) to test the model across a clinical spectrum.

- Data Preprocessing: Features with ≥50% missing data were excluded. Remaining missing values were imputed using the mean. This pragmatic approach managed a large, complex dataset but may reduce variability.

- Model Architecture & Training: A custom transformer model was designed to simultaneously learn multiple objectives:

- Input Feature Reconstruction

- BA and CA Alignment

- Health Status Discrimination

- Mortality Prediction

- Training leveraged unsupervised and self-supervised strategies, avoiding over-reliance on CA as a primary anchor.

- Validation & Comparison: Model performance was compared against established methods (Klemera and Doubal’s method, CA cluster-based model, deep neural network) by analyzing BA gap distributions, health status stratification, and mortality prediction via Kaplan-Meier analyses.

- Cohort and "Ground Truth" Definition: Models were trained on a "super-control" cohort (n=28,417) from the H-PEACE study, selected for the absence of diseases like diabetes and hypertension, and excluding smokers and drinkers. This defines the assumption that chronological age aligns with biological age in physiologically standard individuals.

- Feature Set: 27 routinely available clinical factors, including demographics, anthropometrics, metabolic panels, liver function tests, and complete blood count.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Eight machine learning models were evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation. Performance was assessed via Adjusted R² and Mean Squared Error (MSE).

- Interpretability: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was conducted to identify significant predictors of biological age, such as kidney function markers, gender, and glycated hemoglobin.

- Scale and Generalizability: The framework was validated across six large, population-based cohorts, encompassing over 10 million participants, to ensure reliability and effectiveness.

- Outputs: The model predicts both overall biological age and organ-specific aging.

- Validation Scope: Predictions were tested for association with all-cause mortality, a wide range of 270 diseases, and aging-related phenotypes.

- Novel Data Source: Utilized abdominal CT scans from 123,281 adults, repurposing routinely collected imaging data for aging assessment.