Bridging the Genotype-Phenotype Gap in Complex Diseases: From Genomic Architecture to AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the strategies and technologies revolutionizing our ability to link complex genotypes to phenotypes, a central challenge in modern biomedical research.

Bridging the Genotype-Phenotype Gap in Complex Diseases: From Genomic Architecture to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the strategies and technologies revolutionizing our ability to link complex genotypes to phenotypes, a central challenge in modern biomedical research. We examine the fundamental architecture of complex disease genetics, including the interplay between rare and common variants and the role of polygenic liability. The review covers cutting-edge methodological advances from massively parallel genetics to generative AI and machine learning frameworks that integrate multi-omics data for phenotype prediction and drug discovery. We address critical troubleshooting considerations for overcoming species translatability issues, data scarcity in rare diseases, and analytical optimization. Finally, we evaluate validation frameworks and comparative performance of emerging approaches, providing researchers and drug development professionals with actionable insights for advancing personalized medicine and therapeutic development.

The Genomic Architecture of Complex Diseases: Unraveling Variant Spectrums and Polygenic Foundations

Abstract The journey from genotype to phenotype represents a central challenge in human genetics. While Mendelian diseases follow clear inheritance patterns driven by mutations in single genes, complex diseases arise from intricate interactions between numerous genetic variants and environmental factors. This whitepaper delineates the spectrum of genetic architecture, from monogenic to highly polygenic traits, and explores the evolutionary forces and advanced methodologies shaping our understanding of these architectures. We provide a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, complete with standardized data tables, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to navigate this challenging landscape.

1. Introduction: From Mendelian Simplicity to Complex Trait Complexity The past decades have witnessed remarkable success in identifying approximately 1,200 genes associated with Mendelian diseases through positional cloning, fundamentally clarifying the molecular basis of these disorders [1] [2]. However, the genetic architecture of complex diseases—including diabetes, schizophrenia, and autoimmune disorders—presents a far more formidable challenge. The term "genetic architecture" refers to the comprehensive description of how genes and environment interact to produce phenotypes, encompassing the number of contributing loci, their effect sizes, allele frequencies, and patterns of epistasis and pleiotropy [3] [4]. This whitepaper examines this architectural spectrum within the broader context of mapping genotype to phenotype, providing technical guidance for researchers tackling the complexities of polygenic diseases.

2. The Architectural Spectrum of Human Disease Genetic diseases span a continuum from simple Mendelian disorders to highly complex polygenic traits, with considerable architectural diversity even among related phenotypes.

Table 1: Spectrum of Genetic Architecture in Human Diseases

| Architectural Feature | Mendelian Diseases | Complex Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Loci | Typically single gene | Dozens to thousands of loci [3] [5] |

| Variant Effect Size | Large, often necessary and sufficient for disease | Small to moderate (typically odds ratio <1.5) [3] |

| Allele Frequency | Rare to common | Common to rare, with most heritability from common variants [3] [5] |

| Environmental Influence | Often minimal | Substantial |

| Examples | Cystic Fibrosis, Huntington's disease | Height, Crohn's disease, schizophrenia [3] |

Even within "simple" Mendelian traits, striking heterogeneity exists. For instance, nearly 2,000 different mutations in the CFTR gene can cause Cystic Fibrosis, while variation at additional modifier loci influences symptom severity [3] [4]. This demonstrates that even monogenic diseases can exhibit complex phenotypic expression.

3. Evolutionary Forces Shaping Genetic Architecture The mutation-selection-drift balance (MSDB) model provides a framework for understanding how evolutionary forces shape the genetic architecture of complex diseases [6]. According to this model, genetic variation influencing disease susceptibility is introduced by mutation and removed through natural selection and genetic drift. For complex diseases with substantial fitness costs, common variation appears minimally affected by directional selection, instead being shaped primarily by pleiotropic stabilizing selection on other traits [6]. In contrast, directional selection may exert stronger effects on rare, large-effect variants. This evolutionary perspective helps explain why highly polygenic architectures persist for many common diseases.

4. Methodological Framework for Dissecting Complex Architecture 4.1 Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and the Missing Heritability Challenge GWAS has been the workhorse for identifying common variants associated with complex traits. As of 2013, a catalog of published GWAS included 1,659 publications and 10,986 associated SNPs [3]. However, a persistent challenge has been the "missing heritability" problem—the discrepancy between heritability estimates from family studies and the variance explained by significant GWAS hits [3] [4]. For example:

- For human height (heritability ~80%), 54 validated variants accounted for only ~5% of phenotypic variation [3] [4].

- For Crohn's disease, 32 identified loci explained approximately 20% of the disease heritability [3].

This missing heritability arises partly because GWAS, focused on common variants, lacks power to detect the numerous loci with very small effect sizes predicted by the infinitesimal model [3]. Yang et al. demonstrated that 294,000 SNPs collectively explained 45% of height variance, with most failing significance thresholds due to small effects [3].

Table 2: Approaches for Elucidating Genetic Architecture

| Method | Application | Insights Gained |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS with SNP arrays | Identifying common variant associations | Limited by missing heritability; small effect sizes [3] [5] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Accessing rare and structural variants | Identifies rare variants with larger effects; better for understudied populations [5] |

| Genomic SEM | Modeling shared genetic factors across traits | Reveals pleiotropy; increases power for gene discovery [7] |

| Expression QTL (eQTL) mapping | Treating transcript abundance as quantitative traits | Reveals genetic architecture of gene expression [3] |

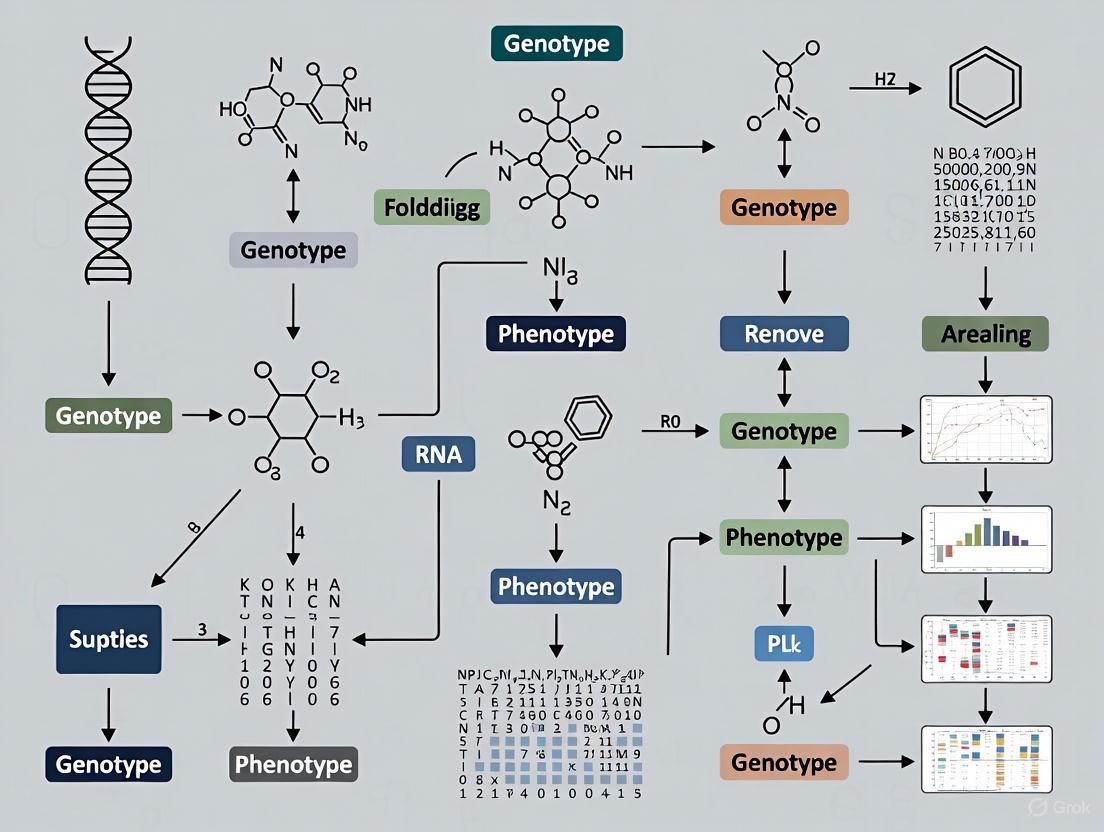

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for analyzing genetic architecture, combining multiple genomic approaches.

4.2 Whole Genome Sequencing for Rare Variant Discovery WGS provides direct access to genetic variation across the entire frequency spectrum without relying on pre-defined variant panels [5]. This technology has enabled:

- Identification of rare variants with large effect sizes, such as a cardioprotective rare variant burden in the APOC3 gene [5].

- Enhanced studies in underrepresented populations where rare or population-enriched variation is poorly characterized [5].

Despite these advances, the proportion of heritability explained by rare variants remains low for most traits. For 22 common traits, rare coding variants explain only 1.3% of phenotypic variance on average [5].

4.3 Integrative Modeling with Genomic SEM Genomic Structural Equation Modeling (Genomic SEM) enables multivariate analysis of shared genetic factors across related traits [7]. This approach integrates GWAS summary statistics from multiple cognitive traits (intelligence, educational attainment, processing speed, etc.) to model latent genetic factors, increasing power for gene discovery and illuminating pleiotropic architecture [7].

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Platforms Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Genetic Architecture Studies

| Resource/Platform | Type | Function | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiologicalNetworks | Visualization & analysis platform | Constructs, visualizes, and analyzes biological networks; integrates heterogeneous data [8] | http://brak.sdsc.edu/pub/BiologicalNetworks [8] |

| PathSys | Data warehouse | Backend for BiologicalNetworks; integrates molecular interactions, ontologies, and expression data from 20+ databases [8] | NLM/NCBI [8] |

| GenomicSEM | R package | Multivariate method for modeling shared genetic factors across traits using GWAS summary statistics [7] | R CRAN [7] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Technology | Comprehensive variant detection across all frequency spectra; identifies structural variants [5] | Illumina, PacBio |

| LD Score Regression | Statistical tool | Estimates heritability and genetic correlation while correcting for confounding [7] | Bulik-Sullivan et al. |

6. Experimental Protocol: Multivariate GWAS for Cognitive Traits 6.1 Protocol: Genomic SEM Analysis for Cognitive Abilities This protocol outlines the multivariate analysis of cognitive traits using Genomic SEM [7].

Objective: To identify shared genetic architecture across cognitive ability-related traits using genomic structural equation modeling.

Input Data Preparation:

- GWAS Summary Statistics Collection: Obtain summary statistics from published GWAS on cognitive traits:

Quality Control:

- Filter to autosomal SNPs with MAF > 0.01

- Exclude SNPs with zero effect estimates

- Resolve allele strand alignment across studies

- Apply standard MHC region exclusion (chr6:25-35Mb) due to complex LD [7]

LD Reference Panel: Use 1000 Genomes Project European population data as the LD reference panel [7].

Genomic SEM Execution:

- Genetic Covariance Matrix Estimation: Calculate the genetic covariance matrix using LD Score regression [7].

- Model Fitting:

- Specify a common factor model with cognitive ability as the latent variable

- Evaluate model fit using CFI (>0.90), SRMR (<0.05), and RMSEA (<0.05) [7]

- GWAS of the Common Factor: Conduct GWAS on the latent cognitive ability factor using the weighted least squares approach in Genomic SEM [7].

Downstream Analysis:

- Gene Mapping: Apply transcriptome-wide association methods to identify candidate causal genes.

- Genetic Correlation: Assess shared genetics with brain imaging phenotypes and neuropsychiatric disorders.

- Pathway Analysis: Conduct functional enrichment analysis of identified loci.

Figure 2: Multi-omics data integration framework for elucidating biological mechanisms from genetic associations.

7. Future Directions and Clinical Translation The future of genetic architecture research lies in integrating WGS with multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to functionally characterize associated variants, particularly in the non-coding genome [5]. Combining association results with functional information will be essential for translating genetic findings into biological mechanisms and therapeutic targets [5]. Additional priorities include:

- Expanding diverse population representation in genetic studies to improve equity and discovery [5]

- Developing improved statistical methods for rare variant association testing [5]

- Leveraging long-read sequencing to comprehensively assess structural variation [5]

For drug development, understanding genetic architecture enables target prioritization through variant effect size, pleiotropy assessment, and functional validation. Genes with supportive functional evidence and favorable pleiotropic profiles make promising therapeutic targets [3].

8. Conclusion The spectrum from Mendelian to complex disease architectures reflects fundamental differences in how genetic variation maps to phenotypic outcomes. While Mendelian diseases follow relatively straightforward genotype-phenotype relationships, complex diseases emerge from intricate networks of small-effect variants, rare larger-effect mutations, and environmental interactions. Advanced methodologies including WGS, multivariate approaches like Genomic SEM, and integrated network analyses are progressively illuminating this complexity. As these tools mature and datasets expand, researchers and drug developers will be increasingly equipped to decode the genetic architecture of complex diseases, ultimately enabling more targeted interventions and personalized therapeutic strategies.

The central challenge in complex disease research lies in deciphering the relationship between genotype and phenotype, a connection characterized by substantial polygenicity. Rather than being governed by single genes, most common disorders—including schizophrenia, coronary artery disease, and type 2 diabetes—arise from the cumulative effect of numerous genetic variants, each contributing modestly to overall risk [9]. This polygenic architecture has necessitated the development of quantitative methods capable of capturing this distributed genetic liability across the genome.

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) have emerged as a primary tool for quantifying this cumulative risk, providing a single metric that reflects an individual's genetic predisposition to a specific disease or trait [10]. Calculated as a weighted sum of an individual's risk alleles based on effect sizes from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), PRS effectively stratifies individuals according to their genetic susceptibility [9]. These scores represent a operationalization of the common variant burden, enabling researchers to move beyond single-variant analyses to a more comprehensive assessment of genetic risk.

The clinical and research applications of PRS are multifaceted. Beyond risk prediction, PRS provide insights into disease prognosis, mechanisms, and subtypes; illuminate shared genetic architecture between distinct disorders; and offer potential for enriching clinical trials by identifying individuals with desired risk profiles [10]. As GWAS sample sizes have expanded, revealing thousands of trait-associated variants, the predictive power of PRS has correspondingly increased, making them increasingly valuable tools for both basic research and translational applications [9].

Technical Foundations of Polygenic Scoring

Core Methodological Approaches

The computational foundation of polygenic scoring rests on integrating genome-wide association data into individualized risk metrics. Several methodological approaches have been developed, each with distinct advantages for handling the statistical challenges inherent in PRS construction.

Clumping and Thresholding methods represent one of the earliest approaches, employing linkage disequilibrium (LD)-based pruning (clumping) to select a subset of relatively independent single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Variants are further filtered based on their association p-values from GWAS (thresholding), with scores calculated by summing allele counts weighted by their effect sizes across all SNPs meeting these criteria [9]. This approach is implemented in tools such as PRSice and PLINK and benefits from computational efficiency and straightforward interpretation.

Bayesian Methods represent a more sophisticated approach that explicitly models the underlying genetic architecture and correlation structure between variants without requiring preliminary SNP selection. LDpred, one of the most widely used Bayesian methods, employs a prior on effect sizes that accounts for LD and assumes a continuous distribution with many small effects across the genome [9]. More recent developments like SBayesR further refine this approach by using more flexible mixture priors, typically improving predictive accuracy, particularly for traits with more complex genetic architectures [9].

Ensemble Methods represent the cutting edge of PRS methodology, recognizing that no single method consistently outperforms all others across diverse traits and populations. These approaches combine PGS derived via multiple methods through meta-algorithms like elastic net models, which perform well because different methods may capture complementary aspects of the genetic architecture [11]. Evaluation across five biobanks and 16 traits demonstrated that ensemble PGS tuned in the UK Biobank provided consistent, high, and cross-biobank transferable performance, increasing PGS effect sizes by a median of 5.0% relative to the best-performing single methods [11].

Advanced Methodological Extensions

Recent methodological innovations have expanded the scope of polygenic scoring beyond common variants. Pharmagenic Enrichment Scores (PES) represent a biologically supervised framework that quantifies an individual's common variant enrichment in clinically actionable systems responsive to existing drugs [12]. Unlike standard PRS that aggregate risk across the genome, PES leverages the joint effect of common variants in pathways that can be putatively modulated by known pharmacological compounds, thus providing a pharmacologically directed annotation of genomic burden [12].

For rare variant integration, novel frameworks have been developed to construct complex trait PGS from rare variants, addressing methodological challenges distinct from common variant scoring. These approaches typically include genes based on their aggregate P-values and functional annotations, with variant weights assigned based on aggregate effect sizes for bioinformatically defined variant masks [13]. This methodology has demonstrated that rare variants can meaningfully contribute to PGS for complex traits, with one study identifying a PGS comprising 21,293 rare variants across 154 genes that significantly improved the identification of undiagnosed type 2 diabetes cases [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Polygenic Scoring Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Advantages | Limitations | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clumping & Thresholding | Selects LD-independent SNPs below p-value threshold | Computationally efficient; straightforward interpretation | Sensitive to p-value threshold choice; may discard informative SNPs | PRSice, PLINK |

| Bayesian Methods | Models SNP effect sizes with priors accounting for LD | Captures more genetic architecture; typically higher prediction accuracy | Computationally intensive; requires LD reference panel | LDpred, SBayesR |

| Ensemble Methods | Combines scores from multiple methods | Robust performance across traits; transferable across biobanks | Increased complexity in implementation and tuning | Elastic net combinations of multiple methods |

| PES Framework | Biologically supervised pathway enrichment | Clinically actionable; targets specific drug-responsive systems | Requires specialized pathway annotation | Custom implementations based on TCRD, DGidb |

Quantitative Performance and Validation Metrics

Measures of Predictive Accuracy

The predictive utility of polygenic scores is quantified through several standardized metrics, each capturing different aspects of performance. For binary traits such as disease status, the most commonly reported metrics include the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC), which measures discriminative accuracy across all possible classification thresholds; odds ratios (OR) or hazard ratios (HR) per standard deviation increase in PGS, which quantify effect size; and variance explained on the liability scale (R²), which estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to the score [9].

For continuous traits, such as biomarker levels or cognitive performance, incremental R² (the increase in variance explained after accounting for covariates) and correlation coefficients between observed and predicted values are standard metrics [14]. The coefficient of determination (R²) is particularly useful for comparing model performance across studies, though it must be interpreted in the context of trait heritability and study design.

Recent large-scale evaluations have quantified PGS performance across diverse diseases. For example, in a multi-biobank analysis of 18 high-burden diseases, PGS hazard ratios per standard deviation ranged from 1.06 (95% CI: 1.05–1.07) for appendicitis to 2.18 (95% CI: 2.13–2.23) for type 1 diabetes [15]. The fraction of phenotypic variance explained by PGS for rare neurodevelopmental conditions was estimated at 11.2% (8.5–13.8%) on the liability scale, assuming a population prevalence of 1% [16].

Stratified Performance and Effect Modification

PGS performance is not uniform across demographic groups or clinical contexts, highlighting the importance of stratified analyses. Age significantly modifies PGS effects for many conditions, with a larger effect typically observed in younger individuals. In a study of 18 diseases, significant heterogeneity across age quartiles was detected in 13 phenotypes, with effects decreasing approximately linearly with age [15]. For type 1 diabetes, the PGS effect per standard deviation was 2.57 (95% CI: 2.47–2.68) in the youngest quartile (age < 12.6) compared to 1.66 (95% CI: 1.58–1.74) in the oldest quartile (age > 33.3) [15].

Sex-specific effects have also been identified for several conditions. Significant interactions between disease-specific PGS and sex were observed for five diseases: coronary heart disease, gout, hip osteoarthritis, and asthma showed larger effects in men, while type 2 diabetes showed a larger effect in women [15]. These stratified effects have important implications for the equitable application of PGS in clinical settings and highlight the potential for genetically informed, demographically tailored risk assessment.

Table 2: Performance of Polygenic Scores Across Selected Diseases

| Disease/Trait | Key Metric | Performance Estimate | Modifiers | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 Diabetes | HR per SD | 2.18 (95% CI: 2.13–2.23) | Strong age effect (younger > older) | Risk stratification from early life |

| Schizophrenia | Variance explained | Pseudo-R²: 1.3–7.7% across psychosis spectrum | Cross-predictive for bipolar disorder | Differential diagnosis in psychosis spectrum |

| Coronary Heart Disease | HR per SD | Range: 1.13–1.41 across biobanks | Larger effect in men; decreases with age | Complementary to clinical risk factors |

| Rare Neurodevelopmental Conditions | SNP heritability | 11.2% (8.5–13.8%) on liability scale | Less polygenic risk in monogenic diagnoses | Elucidation of missing heritability |

| HbA1C (combined rare+common) | Reclassification OR | 2.71 (P = 1.51×10⁻⁶) | Erythrocytic variants affect diagnostic accuracy | Genetically-informed diagnostic thresholds |

Integration of Common and Rare Variant Contributions

Interplay Between Variant Classes

The traditional dichotomy between common and rare variants in complex disease etiology is increasingly being replaced by a more nuanced understanding of their interplay. Evidence suggests that complex phenotypes are influenced by both low-effect common variants and high-effect rare deleterious variants, with both contributions potentially acting additively or interactively to determine disease risk [14].

The liability threshold model provides a useful framework for understanding this relationship, proposing that individuals develop disease when their total burden of genetic and environmental risk factors exceeds a critical threshold [16]. Under this model, patients with highly penetrant rare variants (constituting a monogenic diagnosis) would require, on average, less polygenic load to cross the diagnostic threshold than those without such variants. Supporting this model, patients with rare neurodevelopmental conditions who had a monogenic diagnosis demonstrated significantly less polygenic risk than those without, consistent with the threshold model wherein those carrying highly penetrant variants require fewer common risk variants to reach the diagnostic threshold [16].

This interplay has practical implications for diagnostic yields. Analyses of neurodevelopmental disorders, hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers have shown that individuals carrying rare pathogenic variants tend to cluster in the low PRS range, while those with high PRS are more likely to have symptoms consistent with a complex polygenic architecture rather than a single-gene cause [17]. In one genetic obesity clinic, rare pathogenic variants in obesity genes were more than twice as common among individuals in the low-risk PRS segment [17].

Analytical Frameworks for Combined Risk Modeling

Methodological innovations now enable more integrated analysis of common and rare variant contributions. Gene-based burden scores represent one approach, collapsing information about rare functional variants within a gene into a single genetic burden score that can be used for association analysis [14]. These scores can then be integrated with PRS based on common variants for more comprehensive genetic risk modeling.

For blood biomarkers, this combined approach has revealed important patterns. Association analyses using gene-based scores for rare variants identified significant genes with heterogeneous effect sizes and directionality, highlighting the complexity of biomarker regulation [14]. For example, the ALPL gene showed a strong negative effect on alkaline phosphatase levels (effect size = -49.6), while LDLR showed a positive effect on LDL direct measurement (effect size = 23.4) [14]. However, for prediction, combined models for many biomarkers showed little or no improvement compared to PRS models alone, suggesting that while rare variants play strong roles at an individual level, common variant-based PRS might be more informative for genetic susceptibility prediction at the population level [14].

Diagram 1: Integrated Framework for Combining Common and Rare Variant Information in Polygenic Risk Modeling. This workflow illustrates the parallel processing of common variants from GWAS and rare variants from sequencing data, culminating in integrated risk models with enhanced predictive utility.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard PRS Derivation Workflow

The construction of polygenic scores follows a systematic workflow with defined quality control steps. The foundational requirement is access to genome-wide association study summary statistics from a large discovery sample, preferably from a consortium-level meta-analysis to ensure adequate power. For the target dataset, genotype data must undergo rigorous quality control, including filters for call rate, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, heterozygosity rates, and relatedness [9].

The core analytical steps include:

LD Reference Preparation: Obtain an appropriate reference panel matched to the ancestry of the target sample, such as the 1000 Genomes Project, to account for linkage disequilibrium patterns.

Clumping and Thresholding: For clumping-based methods, perform LD-based pruning (typically using r² < 0.1 within a 250kb window) to select independent SNPs, then apply p-value thresholds to determine which SNPs to include. Multiple thresholds (e.g., PT < 0.001, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1) are often tested, with the optimal threshold selected via validation in an independent sample [12].

Score Calculation: For each individual, calculate the polygenic score as S = Σ(βᵢ × Gᵢ), where βᵢ is the effect size of SNP i from the discovery GWAS and Gᵢ is the genotype dosage (0, 1, or 2) of the effect allele [9].

Normalization: Standardize the resulting scores to have mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1 for easier interpretation and comparison.

For Bayesian methods like LDpred, the process involves:

GWAS Summary Statistics: Ensure summary statistics are properly formatted and aligned to a reference panel.

LD Estimation: Calculate the LD matrix from the reference panel.

Gibbs Sampling: Run the LDpred algorithm with recommended parameters (e.g., fraction of causal variants grid = 1, 0.3, 0.1, 0.03, 0.01, 0.003, 0.001, 0.0003) [9].

Validation: Evaluate the performance of each parameter setting in a validation sample, selecting the optimal model for application in the target dataset.

Pharmagenic Enrichment Score Protocol

The Pharmagenic Enrichment Score (PES) framework represents a specialized extension of polygenic scoring that focuses on clinically actionable pathways. The protocol involves:

Pathway Definition: Identify gene sets representing biological pathways with known drug targets using databases like TCRD (Target Central Resource Database) and DGidb (Drug Gene Interaction Database) [12].

Gene-wise Variant Enrichment: Calculate common variant enrichment for each gene at varying p-value thresholds (PT) to capture different components of the polygenic signal. Typical thresholds include all SNPs, PT < 0.5, PT < 0.05, and PT < 0.005 [12].

Pathway Scoring: Construct PES for each pathway by aggregating the cumulative effect sizes of variants within that pathway for each individual.

Clinical Annotation: Match pathway genes to known drug interactions using the DGidb database, selecting candidate pharmacological agents based on interaction confidence scores [12].

Expression Validation: Where available, validate the biological saliency of PES profiles through their impact on gene expression using matched transcriptomic data [12].

In schizophrenia research, this approach identified eight clinically actionable gene-sets with putative drug interactions, including the HIF-2 pathway (P = 3.12×10⁻⁵), one carbon pool by folate (P = 1.4×10⁻⁴), and pathways related to GABA and acetylcholine neurotransmission [12].

Rare Variant PGS Construction

The integration of rare variants into PGS requires specialized methodologies distinct from common variant approaches:

Variant Annotation: Annotate rare variants (typically MAF < 0.01) for predicted functional impact using tools like ANNOVAR, VEP, or similar pipelines, focusing on predicted high or moderate impact variants [13].

Gene-based Aggregation: Collapse rare variants by gene, considering different variant masks based on functional annotations and frequency thresholds.

Gene Selection: Include genes in the rare variant PGS based on their aggregate association p-values and supporting evidence from functional annotations or prior knowledge (e.g., from knockout mouse models) [13].

Weight Assignment: Assign weights to variants based on aggregate effect sizes for the bioinformatically defined masks that contain the variant, using a "nested" method where each variant receives a weight equal to the aggregate effect size of variants with annotations at least as severe [13].

Score Calculation: Construct the rare variant PGS by summing the weighted burden across all selected genes.

This approach has been successfully applied to hemoglobin A1C, where a rare variant PGS comprising 21,293 variants across 154 genes identified significantly more undiagnosed type 2 diabetes cases than expected by chance (OR = 2.71, P = 1.51×10⁻⁶) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Resources for Polygenic Score Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Statistics | PGC, GWAS Catalog, IEU GWAS Database | Effect size estimates for PRS construction | Ensure ancestry matching; check for overlapping samples |

| Genotyping Platforms | Illumina Global Screening Array, UK Biobank Axiom Array | Generate genotype data for target samples | Consider imputation to reference panels for enhanced coverage |

| PRS Software | PRSice, PLINK, LDpred, LDPred2, SBayesR | Implement polygenic scoring methods | Method choice depends on trait architecture and sample size |

| LD Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes, HRC, TOPMed | Account for linkage disequilibrium | Critical for Bayesian methods; must match target ancestry |

| Functional Annotation | ANNOVAR, VEP, CADD, REVEL | Annotate variant functional impact | Essential for rare variant PGS and pathway enrichment |

| Drug-Gene Interaction | DGidb, TCRD, DrugBank | Identify clinically actionable targets | Core for pharmagenic enrichment score approaches |

| Pathway Databases | GO, KEGG, Reactome | Define biological pathways for enrichment | Enables systems-level interpretation of polygenic risk |

| Biobanks | UK Biobank, FinnGen, All of Us | Validation cohorts for PGS performance | Facilitate cross-population evaluation and method benchmarking |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Ancestry-Related Limitations and Equity Concerns

A significant limitation in current polygenic scoring approaches is their reduced performance in non-European populations, creating potential for health disparities. The transferability of PRS across populations is limited, with scores generated from GWAS in one population typically providing attenuated predictive accuracy in other populations [9]. This limitation stems from multiple factors, including differences in linkage disequilibrium patterns, allele frequency differences, potential differences in causal variants or effect sizes, and the Eurocentric bias in most large GWAS [9].

Currently, only a small proportion of GWAS participants are of non-European ancestry, with less than 3% of study participants in the GWAS Catalog being of African ancestry as of 2020 [9]. This representation imbalance creates a critical methodological challenge: the use of tagging SNPs optimized for European populations, differences in LD patterns between populations, and SNP arrays biased to variants of European descent all contribute to reduced portability [9].

Potential solutions include large-scale GWAS in diverse populations, development of transancestral methods, and creation of ancestry-matched reference panels. Novel methods for 'polyethnic' scores, like XP-BLUP and Multi-ethnic PRS, which improve predictive accuracy by combining transethnic with ethnic-specific information, are under development [9]. Substantial investment will be needed to achieve equivalence of genetic information required for equity of access when polygenic risk scores are applied in the clinic [9].

Integration into Clinical Diagnostics

The potential integration of PRS into clinical diagnostics presents both opportunities and challenges. Several implementation scenarios have been proposed, each with distinct trade-offs:

PRS as First-Tier Screen: Using PRS to stratify patients for subsequent rare variant testing, leveraging the lower cost and faster turnaround time of SNP arrays compared to sequencing. This approach may be cost-effective for increasing the diagnostic yield of whole-exome sequencing, particularly for disorders where both monogenic and polygenic forms exist [17].

Parallel Testing: Performing rare variant detection and common variant analysis simultaneously from whole-genome sequencing data. This comprehensive approach provides both monogenic and polygenic risk information in a single assay but raises challenges related to data storage, interpretation complexity, and potential secondary findings [17].

Selective Testing Based on Clinical Features: Prioritizing either PRS or rare variant testing based on specific clinical characteristics, such as the presence of syndromic features or early disease onset. This patient-centered approach aligns with current clinical practice but requires maintaining multiple diagnostic workflows [17].

PRS in Unexplained Cases: Applying PRS only after negative results from rare variant testing, helping to identify patients in whom a polygenic contribution to disease risk is more likely. This approach reserves costly sequencing for cases with higher pre-test probability of monogenic causes [17].

Key challenges for clinical implementation include defining clinically meaningful risk thresholds, translating relative risks to absolute risks through accurate calibration, developing standards for reporting and interpretation, and ensuring equitable performance across diverse patient populations [17].

Diagram 2: Clinical Decision Framework for Integrating PRS and Rare Variant Testing. This diagnostic workflow illustrates how clinical features can guide test selection, with PRS particularly valuable for cases lacking classic monogenic presentations.

Polygenic scores represent a powerful approach for quantifying the cumulative impact of common genetic variants on complex disease risk, providing a crucial bridge between genotype and phenotype in complex diseases research. As methodological refinements continue and GWAS sample sizes expand, the accuracy and utility of these scores will further improve. The integration of PRS with rare variant information, clinical biomarkers, and environmental factors will enable more comprehensive risk prediction models. However, realizing the full potential of polygenic scoring will require addressing critical challenges related to ancestry-based performance disparities, clinical implementation pathways, and ethical considerations. As these challenges are met, polygenic scores are poised to become increasingly integral to both basic research and clinical application in complex disease genetics.

The central challenge in modern genetics lies in elucidating the pathway from genetic blueprint to observable trait or disease manifestation—the genotype to phenotype problem. Complex human diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and asthma are rarely governed by single-gene mutations but rather emerge from intricate networks of multiple genes working in concert [18]. The sheer number of possible gene combinations creates a formidable analytical challenge for researchers attempting to pinpoint specific causal factors. Systems biology approaches that map gene regulatory networks and protein-protein interactions provide the foundational framework for understanding how genetic information flows through biological systems to produce phenotypic outcomes. These networks represent the functional architecture through which cellular states are established, maintained, and disrupted in disease pathology. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, single-cell technologies, and network reconstruction algorithms are now enabling unprecedented resolution in modeling these complex relationships, offering new pathways for therapeutic intervention in complex diseases [18] [19].

Computational Methodologies for Network Reconstruction

AI-Driven Identification of Causal Gene Sets

The Transcriptome-Wide conditional Variational auto-Encoder represents a breakthrough in generative artificial intelligence for identifying gene combinations underlying complex traits. Unlike traditional methods that examine individual gene effects in isolation, TWAVE employs a sophisticated approach combining machine learning with optimization to identify groups of genes that collectively cause complex traits to emerge. The model amplifies limited gene expression data, enabling researchers to resolve patterns of gene activity that cause complex traits by emulating diseased and healthy states so that changes in gene expression can be matched with changes in phenotype [18].

A key innovation of this approach is its focus on gene expression rather than gene sequence, providing dynamic snapshots of cellular activity that implicitly account for environmental factors which can turn genes "up" or "down" to perform various functions. The method uses an optimization framework to pinpoint specific gene changes most likely to shift a cell's state from healthy to diseased or vice versa. When tested across several complex diseases, TWAVE successfully identified disease-causing genes—some missed by existing methods—and revealed that different sets of genes can cause the same complex disease in different people, suggesting personalized treatments could be tailored to a patient's specific genetic drivers of disease [18].

Population-Level Gene Regulatory Network Inference

SCORPION represents another significant advancement for reconstructing comparable gene regulatory networks from single-cell/nuclei RNA-sequencing data suitable for population-level studies. The algorithm addresses critical challenges in single-cell data analysis, including high sparsity and cellular heterogeneity, which have previously limited robust network comparisons across samples [19] [20].

The SCORPION algorithm implements a five-step iterative process:

- Coarse-graining: Highly sparse single-cell data are processed by collapsing a k number of the most similar cells identified at the low-dimensional representation of the multidimensional RNA-seq data, reducing sample size while decreasing data sparsity.

- Initial network construction: Three distinct initial unrefined networks are built as described in the PANDA algorithm: the co-regulatory network (representing co-expression patterns between genes), the cooperativity network (accounting for known protein-protein interactions between transcription factors from STRING database), and the regulatory network (describing relationships between transcription factors and their target genes through transcription factor footprint motifs).

- Availability and responsibility calculation: A modified version of Tanimoto similarity designed for continuous values generates the availability network (representing information flow from a gene to a transcription factor) and the responsibility network (representing information flow from a transcription factor to a gene).

- Network updating: The average of the availability and responsibility networks is computed, and the regulatory network is updated to include a user-defined proportion (α = 0.1 by default) of information from the other two original unrefined networks.

- Iterative refinement: Steps three to five are repeated until the Hamming distance between networks reaches a user-defined threshold (0.001 by default) [19].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Network Reconstruction Methods

| Method | Precision | Recall | Transcriptome-Wide Capability | Prior Information Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCORPION | 18.75% higher than other methods | 18.75% higher than other methods | Excellent | Yes (multiple sources) |

| PPCOR | Similar to SCORPION | Similar to SCORPION | Limited | Limited |

| PIDC | Similar to SCORPION | Similar to SCORPION | Limited | Limited |

| WGCNA | Lower than SCORPION | Lower than SCORPION | Moderate | No |

When systematically evaluated against 12 other network construction techniques using BEELINE, SCORPION generated 18.75% more precise and sensitive gene regulatory networks than other methods and consistently ranked first across seven evaluation metrics [19]. The method has demonstrated particular utility in identifying differences in regulatory networks between wild-type and transcription factor-perturbed cells, and has shown scalability to population-level analyses using a single-cell RNA-sequencing atlas containing 200,436 cells from colorectal cancer and adjacent healthy tissues [20].

Deep Learning Architectures for Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

Deep learning has revolutionized protein-protein interaction prediction through several core architectural paradigms. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) based on graph structures and message passing adeptly capture local patterns and global relationships in protein structures by aggregating information from neighboring nodes to generate representations that reveal complex interactions and spatial dependencies [21].

Key GNN variants include:

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) employ convolutional operations to aggregate information from neighboring nodes, making them highly effective for node classification and graph embedding tasks.

- Graph Attention Networks (GATs) introduce an attention mechanism that adaptively weights neighboring nodes based on their relevance, enhancing flexibility for graphs with diverse interaction patterns.

- GraphSAGE is designed for large-scale graph processing, utilizing neighbor sampling and feature aggregation to reduce computational complexity.

- Graph Autoencoders (GAEs) utilize an autoencoder-based approach with GCN layers to generate compact low-dimensional node embeddings for graph reconstruction or predictive tasks [21].

Innovative frameworks like AG-GATCN integrate GAT and temporal convolutional networks to provide robust solutions against noise interference in PPI analysis, while RGCNPPIS integrates GCN and GraphSAGE to simultaneously extract macro-scale topological patterns and micro-scale structural motifs. The Deep Graph Auto-Encoder innovatively combines canonical auto-encoders with graph auto-encoding mechanisms for hierarchical representation learning [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TWAVE Implementation Protocol

The TWAVE framework requires specific computational and data processing steps for proper implementation:

Data Requirements and Preparation:

- Collect gene expression data from clinical samples with known disease status (healthy vs. diseased)

- Ensure data privacy by using expression data rather than genetic sequence data

- Normalize expression data to account for technical variability across samples

- Partition data into training and validation sets

Model Training Procedure:

- Initialize the conditional variational autoencoder with appropriate architecture dimensions

- Train the model to learn latent representations that capture the joint distribution of gene expression profiles and phenotypic states

- Implement optimization to identify minimal gene changes that shift cellular states

- Validate model predictions against experimental perturbation data where available

- Perform cross-validation to ensure robustness of identified gene sets

Validation and Interpretation:

- Compare identified gene sets with known disease-associated pathways

- Test robustness across different patient subgroups

- Validate predictions in independent cohorts where possible

- Interpret results in context of potential multi-target therapeutic strategies [18]

SCORPION Experimental Workflow

Input Data Preparation:

- Obtain single-cell or single-nuclei RNA-sequencing count data

- Perform quality control to remove low-quality cells and genes

- Normalize data using standard single-cell processing pipelines

- Identify and remove technical artifacts using appropriate batch correction methods

Network Reconstruction:

- Construct SuperCells or MetaCells by grouping similar cells to reduce sparsity

- Download protein-protein interaction data from STRING database

- Obtain transcription factor binding motif data from relevant databases (JASPAR, TRANSFAC)

- Set algorithm parameters (convergence threshold = 0.001, α = 0.1)

- Execute iterative message-passing algorithm until convergence

- Extract final regulatory network as matrix with transcription factors in rows and target genes in columns [19]

Differential Network Analysis:

- Reconstruct networks for different experimental conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased)

- Compare edge weights between conditions to identify significant changes

- Perform enrichment analysis on differentially regulated targets

- Validate findings using orthogonal methods or perturbation data [20]

SCORPION Algorithm Workflow: From single-cell data to gene regulatory networks.

Enhanced Genetic Discovery Using Predicted Phenotypes

Recent methodological advances demonstrate how machine learning-derived continuous disease representations can enhance genetic discovery beyond traditional case-control genome-wide association studies. This approach involves:

Continuous Phenotype Generation:

- Train machine learning models using comprehensive electronic health record data to generate continuous predicted representations of eight complex diseases

- Ensure model calibration using Brier scores and validate discriminant ability using AUROC and AUPRC metrics

- Generate right-skewed probability distributions representing disease probabilities

Genetic Association Analysis:

- Test common variant associations with both case-control and predicted phenotypes

- Assess genetic correlations between predicted and case-control phenotypes

- Perform multi-trait analysis of GWAS to integrate information from both phenotype types

- Calculate LD-independent variants and heritability estimates for each approach [22]

Validation and Interpretation:

- Replicate findings in independent cohorts

- Assess enrichment in known biological pathways

- Evaluate potential spurious associations

- Compare drug target identification capabilities between methods [22]

Table 2: Performance of Predicted vs. Case-Control Phenotypes in Genetic Discovery

| Metric | Case-Control Phenotypes | Predicted Phenotypes | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median LD-independent variants | 125 | 306 | 160% increase |

| Median genes identified | 91 | 252 | 180% increase |

| Median genetic correlation | 0.66 (with case-control) | 0.66 (with case-control) | - |

| Replication rate at nominal significance | - | 79-90% (AFib, CAD, T2D) | - |

| Drug targets identified | Baseline | +14 additional genes | Enhanced target prioritization |

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Network Reconstruction Algorithms | TWAVE, SCORPION, PANDA | Identify multi-gene determinants of disease and reconstruct regulatory networks from single-cell data |

| PPI Databases | STRING, BioGRID, IntAct, MINT, HPRD | Source of known and predicted protein-protein interaction data |

| Gene Expression Data | Single-cell RNA-seq, Bulk RNA-seq | Input data for network inference and expression quantification |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE, Graph Autoencoders | Predict PPIs and model complex network relationships |

| Evaluation Tools | BEELINE | Systematic benchmarking of network reconstruction algorithms |

| Motif Databases | JASPAR, TRANSFAC | Source of transcription factor binding site information |

| Pathway Databases | Reactome, KEGG | Contextualize findings within known biological pathways |

Analytical Frameworks for Network Interpretation

Comparative Analysis of Network Modeling Approaches

Research comparing gene-gene co-expression network approaches for analyzing cell differentiation and specification on single-cell RNA sequencing data reveals that network modeling choice has less impact on downstream results than the network analysis strategy selected. The largest differences in biological interpretation were observed between node-based and community-based network analysis methods, with additional distinctions between single time point and combined time point modeling [23].

Differential gene expression-based methods have demonstrated superior performance in modeling cell differentiation processes, while combined time point modeling approaches generally yield more stable results than single time point modeling. These findings highlight the importance of selecting analytical strategies matched to specific biological questions rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all approach to network analysis [23].

Visualization and Interpretation of Network Relationships

Information Flow from Genotype to Phenotype: How genetic variation propagates through molecular networks.

Applications in Complex Disease Research and Therapeutic Development

The application of systems biology approaches to gene networks and protein interactions has yielded significant insights into complex disease mechanisms. In colorectal cancer, SCORPION analysis of single-cell RNA-sequencing data from 200,436 cells derived from 47 patients revealed differences between intra- and intertumoral regions consistent with established understanding of disease progression through the chromosomal instability pathway. These findings were confirmed in an independent cohort of patient-derived xenografts from left- and right-sided tumors and provided insight into phenotypic regulators that may impact patient survival [20].

Similarly, the TWAVE framework has demonstrated that different sets of genes can cause the same complex disease in different people, suggesting personalized treatments could be tailored to a patient's specific genetic drivers of disease. This finding has profound implications for precision medicine approaches to complex diseases, moving beyond one-size-fits-all therapeutic strategies toward targeted interventions based on individual network pathology [18].

The integration of predicted continuous phenotypes with traditional genetic association approaches has identified 14 genes targeted by phase I–IV drugs that were not identified by case-control phenotypes alone. Combined polygenic risk scores using both phenotype types demonstrated improved prediction performance with a median 37% increase in Nagelkerke's R2, highlighting the utility of these approaches for enhancing drug target prioritization and risk prediction across diverse populations [22].

These advances collectively represent a paradigm shift in our approach to complex disease, transforming the conceptual framework from one focused on individual molecular components to one embracing the complex network interactions that ultimately determine phenotypic outcomes.

The relationship between genetic variation and phenotypic manifestation represents a central challenge in modern biomedical research. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of how mutations—from nearly neutral to strongly deleterious—distribute across populations and influence complex disease etiology. We examine the population genetic principles governing mutation-selection-balance, explore advanced computational and experimental methodologies for quantifying mutational effects, and demonstrate how integrating diverse data modalities enhances gene discovery and therapeutic target identification. Framed within the context of linking genotype to phenotype, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a technical framework for interpreting mutational impact across the effect-size spectrum.

The comprehensive mapping of genetic variation to phenotypic outcomes requires understanding the full distribution of fitness effects (DFE). The DFE describes the spectrum of selection coefficients for new mutations, ranging from strongly deleterious variants removed by purifying selection to nearly neutral variants whose dynamics are shaped by genetic drift, and rare beneficial mutations that drive adaptation [24] [25]. The shape of the DFE is not static; it is influenced by genetic background, environment, effective population size, and mutation bias—the non-random occurrence of certain mutation types over others [24].

In complex disease research, this framework is paramount. While strongly deleterious, rare variants often underlie Mendelian disorders, nearly neutral variants with subtle effects contribute significantly to complex disease architecture through polygenic mechanisms. Recent technological advances, including large-scale biobanks, machine learning, and high-throughput experimental assays, are now enabling unprecedented resolution in characterizing this mutational spectrum and its consequences for human health.

Theoretical Framework and Population Genetic Principles

Mutation-Selection-Drift Balance

The population frequency of deleterious alleles reflects a balance between the rate at which new mutations arise, their selective cost, and random fluctuations due to genetic drift. For semidominant mutations with heterozygous fitness cost hs, the expected equilibrium frequency is approximately u/(hs), where u is the mutation rate [26]. This model predicts that highly deleterious alleles will be maintained at similarly low frequencies across all ancestry groups due to recurrent mutation, a prediction supported by empirical data from gnomAD showing that protein-coding disruptions (e.g., loss-of-function alleles in constrained genes) occur at comparably low frequencies across diverse populations [26].

Table 1: Key Population Genetic Parameters Governing Mutation Distributions

| Parameter | Symbol | Biological Meaning | Impact on DFE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Population Size | Ne | Number of individuals contributing genes to next generation | Determines efficacy of selection vs. drift on nearly neutral mutations |

| Selection Coefficient | s | Relative fitness reduction of genotype | Directly determines strength of selection against a variant |

| Mutation Rate | u | Probability of a mutation per generation per site | Governs input of new genetic variation |

| Dominance Coefficient | h | Proportion of selection effect expressed in heterozygotes | Affects visibility of recessive alleles to selection |

Demographic History and Ancestry

Demographic processes profoundly influence the distribution of deleterious variation. Population bottlenecks, such as those experienced by non-African populations, reduce the efficacy of purifying selection against nearly neutral variants, allowing mildly deleterious alleles to drift to higher frequencies [25]. Consequently, non-African populations often harbor a higher proportion of rare, deleterious variants and a greater number of homozygous derived deleterious genotypes per individual compared to African populations [25]. However, despite these distributional differences, the overall genetic load—the cumulative fitness reduction from deleterious alleles—is remarkably similar across human populations [26] [25]. This apparent paradox is resolved by considering that while non-African populations may carry more deleterious alleles at intermediate frequencies, African populations harbor a greater number of very rare deleterious variants due to their larger effective population size and greater genetic diversity [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Mutation Effects

Empirical Characterization of the DFE

Experimental studies in model organisms provide direct measurements of how mutation bias influences the DFE. Research in Escherichia coli demonstrates that reversing the ancestral transition mutation bias (97% transitions) to a transversion bias (98% transversions) shifts the DFE, increasing the proportion of beneficial mutations by providing access to previously under-sampped mutational space [24]. Conversely, reinforcing the ancestral bias depletes beneficial mutations. This demonstrates that the DFE is not a fixed property but is dynamically shaped by the interplay between a population's mutational history and its current mutation spectrum.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Distribution of Fitness Effects in E. coli Mutator Strains

| E. coli Strain | Mutation Bias | Key Finding on DFE | Experimental Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | ~54% Transitions (Ts) | Baseline DFE | Lysogeny Broth (LB) and M9 Glucose |

| Strong Ts Bias (e.g., ΔmutT) | Up to 97% Ts | Up to 10-fold fewer beneficial mutations | Lysogeny Broth (LB) and M9 Glucose |

| Strong Tv Bias (e.g., ΔmutY) | Up to 98% Transversions (Tv) | Highest proportion of beneficial mutations (~6% increase) | Lysogeny Broth (LB) and M9 Glucose |

Mutation Rate and Adaptive Evolution

The relationship between mutation rate and adaptation speed is complex and non-linear. Evolution experiments using E. coli mutator strains with varying mutation rates exposed to five different antibiotics revealed that adaptation speed generally increases with mutation rate [27]. However, an optimum exists; the strain with the very highest mutation rate showed a significant decline in evolutionary speed, likely due to the accumulation of deleterious mutations that overwhelm any beneficial effects [27]. This relationship further depends on the selective environment, varying between bacteriostatic and bactericidal antibiotics.

Methodological Approaches for Assessing Mutational Impact

Computational Protein Mutation Effect Predictors

Accurately predicting the functional consequences of missense mutations is crucial for interpreting genetic variation. Computational predictors are broadly categorized into sequence-based, structure-informed, and evolutionary approaches. The VenusMutHub benchmark, which evaluated 23 models on 905 small-scale experimental datasets spanning 527 proteins, provides practical guidance for method selection based on the target property (e.g., stability, activity, binding affinity) [28].

Physics-based methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) simulations offer a rigorous, first-principles approach. The QresFEP-2 protocol, a hybrid-topology FEP method, demonstrates excellent accuracy in predicting mutation-induced changes in protein stability, protein-ligand binding, and protein-protein interactions, serving as a powerful tool for protein engineering and drug design [29].

Diagram 1: QresFEP-2 Workflow for Predicting Mutation Effects on Protein Stability.

AI and Knowledge-Guided Deep Learning for Complex Disease

For complex, polygenic diseases, new computational approaches move beyond single-variant analysis. The TWAVE model uses a generative AI framework to identify groups of genes that collectively cause complex traits by analyzing gene expression data, thereby bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype while implicitly accounting for environmental factors [18].

In the challenging domain of rare genetic diseases, where labeled data is scarce, the SHEPHERD framework employs few-shot learning. It trains a graph neural network on a knowledge graph enriched with rare disease information and simulated patient data to perform causal gene discovery and patient similarity matching, demonstrating effectiveness in diagnosing patients with novel disease presentations [30].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD Database | Data Resource | Catalog of genetic variation from diverse populations | Population-level frequency analysis of variants [26] |

| E. coli Keio Collection | Biological Strain | Library of single-gene knockouts in E. coli | Study of gene function and mutational effects [24] |

| QresFEP-2 Software | Computational Tool | Hybrid-topology Free Energy Perturbation | Predict ΔΔG of point mutations on stability/binding [29] |

| SHEPHERD Framework | AI Model | Knowledge-grounded graph neural network | Few-shot learning for rare disease diagnosis [30] |

| Exomiser | Bioinformatics Pipeline | Variant prioritization tool | Filters candidate genes from WES/WGS data [30] |

| VenusMutHub | Benchmark Platform | Systematic evaluation of predictors | Compare performance of 23 mutation effect models [28] |

Applications in Complex Disease Gene Discovery and Drug Target Prioritization

Linking the DFE to complex disease requires sophisticated phenotyping strategies. Traditional case-control definitions in GWAS often inadequately capture disease heterogeneity. Using machine learning to generate continuous predicted phenotypes from electronic health records (EHRs) significantly enhances genetic discovery. For eight complex diseases, this approach increased the number of identified independent associations by a median of 160% and uncovered 14 genes targeted by phase I–IV drugs that were missed by case-control analyses [22].

Furthermore, integrating these continuous phenotypes into polygenic risk scores (PRS) improved prediction performance, with a median 37% increase in Nagelkerke's R², and enhanced portability across diverse ancestry populations [22]. This demonstrates that refining phenotypic definitions to better reflect the continuous spectrum of disease can powerfully accelerate the mapping from genetic variation to clinical outcome.

Diagram 2: Enhancing Gene Discovery with Continuous Phenotypes and MTAG.

The journey from genetic variant to organismal phenotype is governed by the complex interplay of evolutionary forces encapsulated in the distribution of mutation effects. Key insights emerge: first, strongly deleterious variants are universally rare, but the spectrum of nearly neutral variation is shaped by demographic history and mutation bias. Second, accurately mapping these effects requires a multi-faceted methodological arsenal, from physics-based simulations and AI-driven knowledge graphs to advanced phenotyping from EHRs. Finally, embracing the full complexity of the DFE—and moving beyond simplistic binary models of mutation effect—is essential for unraveling the genetic architecture of complex diseases and translating these insights into novel therapeutic strategies. The continued integration of population genetic theory, large-scale biobank data, and sophisticated computational tools promises to further refine our understanding and accelerate personalized medicine.

The Mutation-Selection Balance and Evolutionary Forces Shaping Disease Genes

Understanding the genetic architecture of complex diseases requires a framework that links static genetic blueprints (genotype) to dynamic, observable outcomes (phenotype). This relationship is not linear but is shaped and filtered by evolutionary forces over generations. The core thesis of modern complex disease research posits that the prevalence and genetic architecture of common, polygenic diseases are a direct consequence of an evolutionary equilibrium between the introduction of new genetic variation by mutation and its removal by natural selection and genetic drift—the mutation-selection-drift balance (MSDB) [31]. This guide explores the technical foundations of this balance, its quantitative modeling, and the experimental paradigms used to decipher how evolutionary forces shape the disease-associated genes we study today.

The Mutation-Selection-Drift Balance (MSDB) Model: A Quantitative Framework

The MSDB model provides a population genetics framework to predict the distribution of genetic effects and allele frequencies for variants influencing disease risk. For complex, polygenic diseases with substantial fitness costs, the model moves beyond classic Mendelian assumptions [31].

Core Assumptions of the Complex Disease MSDB Model:

- Genetic Architecture: Disease risk is influenced by many loci of small effect, consistent with the liability threshold model.

- Selection Source: Selection against disease-risk variants stems primarily from the fitness cost of the disease itself.

- Evolutionary Forces: The population frequency of a risk variant is determined by the equilibrium between its mutation rate (introduction), the selection coefficient against it (removal), and random genetic drift.

A key prediction from recent modeling is that for common diseases, common genetic variation (e.g., GWAS hits) appears to be largely unaffected by strong directional selection related to the disease. Instead, its frequency is likely shaped by pleiotropic stabilizing selection on other traits. Stronger directional selection is predicted to act more efficiently on rare, large-effect variants [31]. This has profound implications for interpreting GWAS results and estimating true disease heritability, which current methods may systematically bias [31].

Evolutionary Driving Forces and Their Impact on Disease Gene Architecture

The MSDB operates through the interplay of four fundamental evolutionary forces, each leaving a distinct signature on the genetic landscape of disease [32].

- Mutation: The ultimate source of new genetic variation, including deleterious alleles that increase disease risk. The rate and effect size spectrum of mutations are critical parameters in MSDB models [33].

- Natural Selection:

- Negative/Purifying Selection: Removes deleterious, high-penetrance disease alleles from the population. This is a primary force in the MSDB for diseases with high fitness costs [32].

- Positive Selection: Can increase the frequency of an allele that is advantageous in a specific environment, potentially carrying linked disease-risk alleles to higher frequency via genetic hitchhiking (e.g., the IBD5 risk haplotype and Crohn's disease) [32].

- Balancing Selection: Maintains multiple alleles at a locus, often when heterozygotes have a fitness advantage. This can preserve ancient disease-risk alleles in populations, as hypothesized for some autoimmune disorders under the "hygiene hypothesis" [32].

- Genetic Drift: Random fluctuations in allele frequencies, particularly powerful in small or founder populations. Drift can allow deleterious alleles to rise in frequency, contributing to population-specific disease risk [33].

- Gene Flow: The transfer of genetic variation between populations through migration. It can introduce new disease alleles or dilute existing ones, altering local MSDB dynamics [32].

Data Synthesis: Quantitative Parameters from Evolutionary Genetics Studies

The following tables summarize key quantitative data and genetic parameters relevant to modeling the evolution of complex diseases.

Table 1: Estimated Parameters for Mutation-Selection-Drift Balance Models in Complex Diseases

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Estimated Range/Value | Biological Interpretation | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Coefficient (against risk allele) | s | ~0.001 - 0.05 for moderately deleterious variants | Strength of natural selection acting to remove the allele from the population. | Inferred from MSDB models [31] |

| Mutation Rate (per locus per generation) | μ | ~1.2 x 10⁻⁸ per base pair (human genome average) | Rate at which new risk alleles are introduced. | Standard population genetic parameter |

| Heritability (in the wild) | h² | Often lower than GWAS estimates | Proportion of phenotypic variance due to genetic factors under real-world selection. MSDB suggests GWAS estimates are biased upward [31]. | Prediction from MSDB theory [31] |

| Population-Scaled Selection Coefficient | γ = 2Nₑs | Determines whether selection (γ >> 1) or drift (γ << 1) dominates an allele's fate. | Core parameter in population genetics |

Table 2: Evolutionary Signatures in Human Complex Disease Genetics

| Evolutionary Force | Genetic Signature | Example Disease Association | Method of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Selection | Long-range haplotype homozygosity, extreme allele frequency differentiation (FST) | Lactase persistence (LCT), Malaria resistance (HbS, G6PD) | iHS, XP-EHH, FST scans [32] |

| Balancing Selection | High genetic diversity, intermediate allele frequency, trans-species polymorphism | Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) loci, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IL23R pathway) | Tajima's D, Hudson-Kreitman-Aguadé test [32] |

| Purifying Selection | Depletion of common variants, enrichment of rare, functional variants in coding regions | Severe developmental disorders, highly penetrant cancer genes (BRCA1) | Comparison of rare vs. common variant burden [32] |

| Genetic Drift / Founder Effect | High frequency of specific rare variant in an isolated population | Finnish disease heritage (e.g., Northern Epilepsy), Ashkenazi Jewish disorders (e.g., Gaucher) | Population-specific allele frequency analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Evolutionary Forces on Disease Genes

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Scans for Natural Selection

- Objective: Identify genomic regions that have undergone recent positive or balancing selection by analyzing patterns of genetic variation.

- Workflow:

- Data Generation: Obtain high-coverage whole-genome sequencing or dense genotype data from multiple individuals across populations (e.g., 1000 Genomes Project).

- Variant Calling & Phasing: Use tools like GATK and SHAPEIT to identify variants and reconstruct haplotype phases.

- Selection Statistic Calculation: Compute statistics per SNP or region:

- iHS (Integrated Haplotype Score): Detects recent positive selection by measuring the length of shared haplotypes around a core allele.

- Tajima's D: Identifies deviations from neutral evolution (negative D suggests positive/balancing selection; positive D suggests balancing selection/population contraction).

- FST: Measures genetic differentiation between populations; high FST can indicate local adaptation.

- Significance Testing: Compare observed statistics to a null distribution generated from coalescent simulations under a neutral model.

- Functional Annotation: Overlap significant regions with GWAS loci, coding exons, and regulatory elements to link selection signals to disease phenotypes [32].

Protocol 2: Estimating Selection Coefficients (s) from Population Genetic Data

- Objective: Quantify the strength of natural selection acting on a specific disease-associated variant.

- Workflow:

- Allele Frequency Spectrum (AFS) Modeling: Fit the observed distribution of allele frequencies for putatively deleterious variants (e.g., loss-of-function mutations) to a population genetic model that includes parameters for mutation rate (μ), effective population size (Nₑ), and selection coefficient (s).

- Use the Site Frequency Spectrum (SFS): Tools like

dadiorfastsimcoal2can infer demographic history and selection parameters by comparing the observed SFS to simulated ones. - Leverage Allele Age and Trajectory: For a known pathogenic allele, estimate its age using linkage disequilibrium decay or phylogenetic methods. Its current frequency and estimated age can be used to infer the selective pressure it has experienced, often using forward simulations.

- Constraint Metrics: Use metrics like pLI (probability of being loss-of-function intolerant) from gnomAD, which indirectly reflect the strength of purifying selection on a gene over evolutionary time.

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Title: Evolutionary Forces Influencing Disease Allele Frequencies

Title: MSDB Model Simulation and Inference Workflow

Table 3: Essential Resources for Evolutionary Analysis of Disease Genes

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Population Genomic Datasets | Provide the raw allele frequency and haplotype data needed to compute selection statistics and fit models. | 1000 Genomes Project, gnomAD, UK Biobank, TOPMed. |

| GWAS Catalog & Summary Statistics | Source of published disease-variant associations for cross-referencing with signals of selection. | NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog, GWAS ATLAS. |

| Selection Scan Software | Tools to compute statistics (Tajima's D, iHS, XP-EHH) and identify genomic regions under selection. | PLINK, SELSCAN, PopGenome (R). |

| Population Genetic Simulators | Generate expected genetic data under complex models of demography and selection for hypothesis testing. | SLiM (forward-time), msms/COAL (coalescent), dadi. |

| Functional Annotation Databases | Annotate significant variants/regions with gene context, regulatory element maps, and disease ontology terms. | ENSEMBL, ANNOVAR, GeneHancer, DISEASES [34]. |

| Curated Gene-Disease Evidence | Provides manually curated scores for gene-disease associations, crucial for prioritizing candidates from selection scans. | DISEASES Curated Gene-Disease Association Evidence Scores [34]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for running large-scale genomic analyses, simulations, and data processing. | Local university cluster, cloud computing (AWS, GCP). |

Next-Generation Mapping Technologies: From Deep Mutational Scanning to Generative AI

Understanding the relationship between genetic variation (genotype) and observable traits or disease states (phenotype) remains a fundamental challenge in biomedical research. This is particularly true for complex diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and many cancers, where phenotypic outcomes are shaped by the interplay of numerous genetic variants, environmental factors, and complex biological networks rather than single-gene defects [35] [36]. For decades, genetic mapping studies were limited by throughput, cost, and resolution. The advent of massively parallel genetics—high-throughput methodologies that enable the simultaneous functional assessment of thousands to millions of genetic variants—has revolutionized our ability to decipher these complex relationships.

Two cornerstone methodologies in this field are Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) and related EMPIRIC approaches. DMS combines comprehensive mutagenesis with high-throughput functional selection and deep sequencing to quantify the effects of thousands of mutations in a single, highly multiplexed experiment [37] [38]. These technologies provide an unprecedented, high-resolution view of how sequence changes affect protein function, protein-protein interactions, and cellular fitness. By systematically probing the genotype-phenotype map, DMS and EMPIRIC empower researchers to interpret human genetic variation, identify pathogenic mutations, understand drug resistance, and reveal fundamental principles of protein structure and function, thereby directly informing drug discovery and development efforts [39] [40].

Core Principles and Methodologies of Deep Mutational Scanning

A typical DMS experiment follows a structured, three-stage pipeline designed to link genotype to phenotype on a massive scale [37] [38]. The core concept is to measure the change in frequency of each variant in a mutant library before and after a functional selection, thereby inferring its effect on fitness or activity.

The Deep Mutational Scanning Workflow

The workflow can be broken down into three main stages, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Key Methodological Components