Brain Size Dichotomy in Autism: A Comparative Analysis of Overgrowth and Undergrowth in Preclinical ASD Models

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the divergent brain growth phenotypes—overgrowth and undergrowth—observed in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Brain Size Dichotomy in Autism: A Comparative Analysis of Overgrowth and Undergrowth in Preclinical ASD Models

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the divergent brain growth phenotypes—overgrowth and undergrowth—observed in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational neuropathological evidence, explores the methodological landscape of animal and cellular models, addresses key challenges in model optimization, and offers a comparative validation of findings across different model systems. The article highlights how specific genetic mutations dysregulate fundamental neurodevelopmental processes, leading to distinct anatomical and behavioral outcomes. By integrating the latest research, including studies on PTEN, DYRK1A, and FXS, this analysis aims to inform the development of targeted, phenotype-specific therapeutic strategies and refine preclinical research paradigms.

The Prenatal Origins of ASD: Defining the Spectrum of Brain Growth Pathologies

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [1] [2]. Despite extensive research, the underlying neuropathological mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Postmortem brain studies and advanced neuroimaging have revealed consistent patterns of early brain overgrowth and cortical disorganization that appear fundamental to ASD pathogenesis [1] [3]. This comprehensive analysis synthesizes current evidence regarding the core neuropathological hallmarks of ASD, focusing on neuron overabundance and laminar disorganization, and provides detailed methodological frameworks for their investigation.

The neurobiological basis of ASD involves atypical early brain development and connectivity, with pathological processes beginning during prenatal development [4]. Evidence indicates that the peak period for detecting the early biological basis of autism spans from prenatal life to the first three years postnatally [4]. The disorder exhibits enormous phenotypic heterogeneity, which is reflected in diverse neuroanatomical variations across individuals [4]. This review systematically compares key neuropathological findings across different methodological approaches and brain regions to establish a coherent framework for understanding ASD pathogenesis.

Core Neuropathological Hallmarks in ASD

Neuron Overabundance and Brain Overgrowth

Table 1: Regional Neuron Overabundance and Brain Overgrowth Patterns in ASD

| Brain Region | Specific Findings | Developmental Timing | Functional Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex | 67% increase in neuron number [5]; Increased cortical surface area [3] | Prenatal origin; evident by age 2 years [3] [5] | Executive dysfunction; impaired social cognition |

| Amygdala | Rapid early increases in size; greater spine density in youth [4] | Early postnatal enlargement; persists through childhood [4] | Deficits in social interaction and communication [4] |

| Temporal Lobe | Disproportionate white matter enlargement [3]; Patches of disorganization [5] | Present by age 2 years [3] | Language processing; social cognition |

| Whole Brain | Generalized cerebral cortical enlargement [3]; Increased head circumference [6] | Accelerated growth prior to age 2 [3] | Overall ASD symptom severity |

One of the most consistent neuropathological findings in ASD is early brain overgrowth (EBO), characterized by an abnormal acceleration of brain growth within the first two years of life [6]. Children with ASD show early increases in brain volume and cortical thickness during infancy and toddler years (2-4 years), followed by an accelerated rate of decline in size from adolescence to late middle age [4]. This aberrant growth pattern does not typically occur at birth but develops throughout the first 2 years of life [4].

The sites of regional overgrowth in ASD include frontal and temporal cortices and the amygdala [4]. A seminal study found that young autistic males present a very significant excess of neuron number in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC)—approximately 67% more neurons compared to typically developing controls [5]. Since no known neurobiological mechanism in humans can generate large excesses of frontal cortical neurons during postnatal life, this magnitude of excess most probably results from dysregulation of layer formation and layer-specific neuronal differentiation at prenatal developmental stages [4].

The brain overgrowth in ASD follows a distinct gradient in the cerebrum: greatest in frontal and temporal cortices (which are most abnormally enlarged) and least in the occipital cortex [4]. Longitudinal MRI studies have demonstrated generalized cerebral cortical enlargement in individuals with ASD at both 2 and 4-5 years of age, with no increased rate of cerebral cortical growth during this interval, indicating that brain enlargement in ASD results from an increased rate of brain growth prior to age 2 [3].

Cortical Laminar Disorganization

Table 2: Characteristics of Cortical Laminar Disorganization in ASD

| Feature | Findings | Detection Method | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Patches | Abnormal laminar cytoarchitecture and cortical disorganization [5] | RNA in situ hybridization with layer-specific markers [5] | 10 of 11 children with ASD [5] |

| Affected Layers | Most evident in layers 4 and 5; no layer uniformly spared [5] | Molecular markers (CALB1, RORB, PCP4, etc.) [5] | Heterogeneous across cases |

| Affected Cell Types | Abnormalities primarily in neurons, not glia [5] | Cell-type specific markers [5] | Varies by case |

| Regional Distribution | Prefrontal and temporal cortices; spared occipital cortex [5] | Multi-region comparison [5] | Consistent across studies |

A groundbreaking discovery in ASD neuropathology is the finding of focal patches of abnormal laminar cytoarchitecture and cortical disorganization in young children with autism [5]. These patches represent localized disruptions in the precise layered organization of the cerebral cortex and are most frequently observed in prefrontal and temporal cortical regions [5].

In a detailed analysis of postmortem samples from children with ASD ages 2-15 years, researchers observed these patches in 10 of 11 children with autism compared to only 1 of 11 unaffected children [5]. The patches exhibit heterogeneity between cases with respect to the cell types that are most abnormal and the layers that are most affected, though the clearest signs of abnormal expression typically occur in layers 4 and 5 [5]. No cortical layer is uniformly spared from these disruptions [5].

Three-dimensional reconstruction of layer markers confirmed the focal geometry and size of these patches, which reflect a probable dysregulation of layer formation and layer-specific neuronal differentiation at prenatal developmental stages [5]. This disruption in the normal cytoarchitecture of the cortex likely underlies the functional impairments in information processing observed in ASD.

Figure 1: Developmental Pathway of ASD Neuropathology. This diagram illustrates the proposed sequence of events leading from initial prenatal disruptions to the manifestation of ASD behavioral symptoms, highlighting the critical developmental window and core pathological hallmarks.

Regional Specificity of Neuropathological Alterations

Prefrontal Cortex Abnormalities

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) emerges as a consistently affected region in ASD neuropathology. Beyond the marked neuron overabundance, the PFC exhibits disorganized gray and white matter with thickening in the subependymal layer and various forms of cortical dyslamination [1]. Minicolumns, representing functional structures where afferent, efferent and local connections of pyramidal projection neurons converge in the neocortex, show significant alterations in ASD [1].

Patients with ASD have been found to have smaller and more numerous minicolumns with more dispersed neurons in Brodmann's areas 9, 21, and 22 [1]. These minicolumnar abnormalities may be related to macroencephaly, abnormal connectivity, and early age of onset of ASD [1]. Differences in frontal minicolumnar growth trajectory show narrower minicolumns in the dorsal and orbital frontal cortex in ASD, changes that appear to be regionally specific as they are not present in the primary visual cortex [1].

Amygdala and Limbic System Pathology

The amygdala displays distinctive pathological changes in ASD. In typical fetal brain development, the amygdala displays structural connectivity across the cortex, particularly toward frontal and temporal lobes, by gestational week GW13 and achieves a mature structure by 8 months [4]. In ASD, the most consistent findings include:

- Rapid and early increases in the size of the right and left amygdala, which correlate positively with the extent of deficits in social interaction and communication at age 5 [4]

- Greater amygdala spine density in youths with ASD than in age-matched typically developing controls (<18 years), which decreases as they grow older—a pattern not found in typical development [4]

- Initial overabundance of amygdala neurons in young ASD subjects, followed by a reduction in all nuclei during adult years [4]

The paralaminar nucleus (PL), a unique subregion of the amygdala densely innervated by serotonergic fibers, appears particularly relevant to ASD pathology due to its role in neuronal plasticity [4].

Cerebellar and Brainstem Involvement

While less emphasized than cortical abnormalities, consistent neuropathological alterations have been reported in the cerebellum and brainstem in ASD [1]. Global brain developmental abnormalities manifest in the archicortex, cerebellum, brainstem, and other subcortical structures, with region-specific severity of neuropathology in young children with ASD [1].

The consistent presence of changes in the cerebellum revealed by neuropathologic investigations in ASD has been identified as one of the successful examples of this research approach [1]. These findings highlight that ASD neuropathology extends beyond cerebral cortex to include subcortical structures that contribute to the diverse behavioral manifestations of the condition.

Methodological Approaches for Neuropathological Investigation

Experimental Protocol: Marker-Based Phenotyping of Cortical Organization

Objective: To systematically examine neocortical architecture and identify patches of disorganization in postmortem brain tissue from individuals with ASD.

Materials and Methods:

Tissue Acquisition: Obtain fresh-frozen postmortem cortical tissue blocks (1-2 cm³) from dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, posterior superior temporal cortex, and occipital cortex (Brodmann's area 17) [5].

Marker Selection: Select cortical layer-specific molecular markers through initial screening of genes with robust, consistent, and specific expression patterns. Final markers should include:

- Layer-specific excitatory neuron markers

- Inhibitory neuron markers (GABAergic)

- Glial cell markers

- Autism candidate risk genes [5]

Tissue Processing:

- Serially cryosection tissue at 20μm thickness in a plane containing all cortical layers

- Group sections into series of 30 sections per series

- Allocate sections for in situ hybridization, Nissl staining, and future use [5]

RNA In Situ Hybridization:

- Implement automated high-throughput in situ hybridization protocols

- Process postmortem samples of young human postnatal fresh-frozen brain tissue

- Acquire whole-slide digital imaging for analysis [5]

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction:

- Use sequential section analysis to reconstruct patch geometry

- Confirm focal nature and size of disrupted areas

- Correlate with layer-specific marker expression [5]

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Cortical Patch Analysis. This diagram outlines the key methodological steps for identifying and characterizing patches of cortical disorganization in postmortem brain tissue, from initial tissue preparation to final statistical analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASD Neuropathology Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer-Specific Markers | CALB1, RORB, PCP4, PDE1A, NEFL [5] | Identify cortical layers and laminar organization | RNA in situ hybridization |

| Cell-Type Markers | GAD1 (GABAergic neurons), GFAP (astrocytes), IBA1 (microglia) [5] | Distinguish neuronal and glial populations | Cell-type specific analysis |

| Autism Risk Gene Probes | Genes from genetic studies (e.g., SHANK3, NLGN3) [1] [5] | Assess expression of ASD-associated genes | Candidate gene analysis |

| Nissl Stain | Cresyl violet, Thionin [5] | Visualize overall cytoarchitecture | General histology |

| RNA Quality Assessment | RIN (RNA Integrity Number) measurement [5] | Ensure sample quality | Quality control |

Comparative Analysis of ASD Models

Animal Models Recapitulating Neuropathological Hallmarks

Table 4: Animal Models of ASD Neuropathology

| Model Category | Specific Models | Neuropathological Features | Correlation with Human Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monogenic ASD Models | NLGN3, NLGN4, NRXN1, SHANK3, MECP2, FMR1 mutants [1] | Altered dendritic spine density; synaptic defects | High for specific genetic syndromes |

| CNV Models | 15q11-13 deletion/duplication, 16p11.2 deletion/duplication [1] | Brain overgrowth/undergrowth; connectivity changes | Variable based on genetic alteration |

| Idiopathic ASD Models | BTBR inbred strain; prenatal valproate exposure [1] | Cortical disorganization; social behavior deficits | Recapitulates broader ASD phenotype |

| Environmental Models | Maternal immune activation; maternal autoantibodies [1] | Neuron overabundance; inflammatory changes | Relevant for idiopathic ASD cases |

Animal models have been instrumental in exploring the impact of genetic and non-genetic factors clinically relevant for the ASD phenotype [1]. Genetically modified models include those based on well-studied monogenic ASD genes (NLGN3, NLGN4, NRXN1, CNTNAP2, SHANK3, MECP2, FMR1, TSC1/2), emerging risk genes (CHD8, SCN2A, SYNGAP1, ARID1B, GRIN2B, DSCAM, TBR1), and copy number variants (15q11-q13 deletion, 15q13.3 microdeletion, 15q11-13 duplication, 16p11.2 deletion and duplication, 22q11.2 deletion) [1].

A common finding in several animal models of ASD is altered density of dendritic spines, with the direction of the change depending on the specific genetic modification, age and brain region [1]. This aligns with findings in human postmortem studies showing abnormalities in dendritic spine density and morphology [1].

Models of idiopathic ASD include inbred rodent strains that mimic ASD behaviors as well as models developed by environmental interventions such as prenatal exposure to sodium valproate, maternal autoantibodies, and maternal immune activation [1]. In addition to replicating some of the neuropathologic features seen in postmortem studies, these models have been particularly valuable for exploring developmental trajectories and testing potential therapeutic interventions.

Limitations and Translational Challenges

While animal models provide invaluable insights into ASD pathophysiology, important limitations must be considered:

Species differences in cortical development and organization may limit direct translation to human neuropathology [1]

Genetic heterogeneity of human ASD is difficult to fully recapitulate in animal models [1]

Behavioral manifestations in animals may not fully capture the complexity of human ASD phenotypes [1]

Developmental timelines differ significantly between humans and model organisms [1]

Postmortem neuropathologic studies with larger sample sizes representative of the various ASD risk genes and diverse clinical phenotypes are warranted to clarify putative etiopathogenic pathways further and to promote the emergence of clinically relevant diagnostic and therapeutic tools [1].

The neuropathological hallmarks of ASD—from neuron overabundance to laminar disorganization—paint a complex picture of altered brain development that begins prenatally and evolves throughout the lifespan. The consistent findings of early brain overgrowth followed by abnormal developmental trajectories, focal patches of cortical disorganization, and region-specific alterations in neuronal populations provide critical insights into the biological underpinnings of ASD.

Future research should prioritize:

Larger-scale postmortem studies with better representation of the genetic and phenotypic diversity within ASD [1]

Advanced computational approaches for integrating multi-dimensional data from molecular, cellular, and systems levels [2]

Longitudinal designs that can track neuropathological changes across development [3]

Standardized methodological frameworks to enable direct comparison across studies [5]

Understanding the neuropathological hallmarks of ASD not only advances fundamental knowledge of the condition but also creates opportunities for developing targeted interventions that address the underlying biological processes rather than merely managing symptoms. As research progresses, the integration of neuropathological findings with genetic, epigenetic, and clinical data will be essential for unraveling the complexity of autism spectrum disorder.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a highly heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition characterized by atypical social communication and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [7] [8]. Its complex genetic architecture involves contributions from rare monogenic variants with large effect sizes and polygenic factors comprising numerous common variants with small individual effects [9] [10]. Despite this heterogeneity, high-confidence ASD risk genes frequently converge onto shared biological pathways and cellular processes, notably chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and synaptic signaling [11] [12] [13]. Among the hundreds of genes implicated in ASD, PTEN, DYRK1A, and SHANK3 represent paradigmatic examples of pleiotropic risk genes whose haploinsufficiency impacts multiple neurodevelopmental processes. These genes illustrate the principle that distinct genetic lesions can disrupt common functional modules, thereby contributing to overlapping behavioral phenotypes associated with ASD [13] [14]. This comparative analysis examines the molecular functions, pathogenic mechanisms, and experimental approaches for studying these three high-confidence ASD risk genes, providing a framework for understanding convergent pathways in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Gene-Specific Profiles and Functional Roles

Table 1: Comparative Profile of High-Confidence ASD Risk Genes

| Feature | PTEN | DYRK1A | SHANK3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Location | 10q23.31 | 21q22.13 | 22q13.33 |

| Protein Function | Phosphatase; PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway regulator | Dual-specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase | Postsynaptic scaffolding protein |

| Primary Domain | Tensin-like phosphatase domain | Kinase domain | Multiple domains including SH3, PDZ, and SAM |

| Biological Process | Growth suppression, synaptic plasticity, neuronal size | Transcriptional regulation, cell cycle control, neuronal differentiation | Synaptic organization, glutamate receptor anchoring, signal transduction |

| ASD Association Evidence | High confidence (SFARI Score 1) | High confidence (SFARI Score 1) | High confidence (SFARI Score 1) |

| Associated Syndromes | PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome, macrocephaly | Mental retardation, autosomal dominant 7, microcephaly | Phelan-McDermid syndrome, 22q13.3 deletion syndrome |

| Neuronal Expression Pattern | Developing and mature neurons | High in fetal brain, regulates neurogenesis | Predominantly postsynaptic density of excitatory synapses |

| Common Variant Types | Loss-of-function, missense mutations | De novo truncating mutations | De novo and inherited truncating mutations, CNV deletions |

PTEN (Phosphatase and TENsin homolog) encodes a lipid phosphatase that primarily antagonizes the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, serving as a critical regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and metabolic homeostasis [14] [8]. In neurons, PTEN controls soma size, dendritic arborization, and synaptic plasticity, with its haploinsufficiency leading to macrocephaly and altered neural connectivity frequently observed in ASD [8].

DYRK1A (Dual-specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A) belongs to the DYRK kinase family and plays multifunctional roles in neuronal development, including cell cycle control, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic function [9]. DYRK1A haploinsufficiency is strongly associated with microcephaly and intellectual disability, with the kinase functioning as a regulatory hub that phosphorylates transcription factors, splicing factors, and synaptic proteins [9].

SHANK3 (SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3) encodes a master scaffolding protein located in the postsynaptic density of excitatory synapses, where it organizes glutamate receptors, cytoskeletal elements, and signaling molecules into functional complexes [11] [14]. As a central organizer of synaptic architecture, SHANK3 deficiency disrupts the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission and impairs synaptic plasticity, leading to the core behavioral deficits observed in ASD and Phelan-McDermid syndrome [11] [13].

Pleiotropic Pathways and Convergent Mechanisms

Despite their distinct molecular functions, PTEN, DYRK1A, and SHANK3 converge on shared neurodevelopmental pathways. Research reveals that ASD risk genes primarily cluster into two functional categories: gene expression regulation (GER) and neuronal communication (NC) [11]. DYRK1A falls squarely within the GER group, influencing transcriptional networks and chromatin remodeling, while SHANK3 functions predominantly in the NC group, directly mediating synaptic signaling. PTEN exhibits pleiotropic influences across both categories through its regulation of the mTOR pathway, which coordinates protein synthesis with synaptic growth and function [11] [8].

A molecular network analysis examining multiple high-confidence ASD risk genes, including ADNP, KDM6B, CHD2, and MED13, revealed extensive cross-regulatory relationships and convergent targets [13]. This study demonstrated that deficiency in any of these genes impacts the expression of others, creating an interconnected regulatory network. Furthermore, these ASD risk genes commonly regulate synaptic genes such as SNAP25 and NRXN1, either through direct promoter binding or indirect mechanisms via intermediate regulators like CTNNB1 and SMARCA4 [13]. This convergence on shared downstream targets helps explain why genetically heterogeneous forms of ASD manifest similar behavioral phenotypes.

Table 2: Convergent Pathways and Cross-Regulatory Mechanisms

| Convergent Pathway | PTEN Role | DYRK1A Role | SHANK3 Role | Functional Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Signaling | Regulates mTOR-dependent protein synthesis at synapses | Phosphorylates synaptic proteins; modulates NMDA receptor function | Scaffolds glutamate receptors and signaling complexes | All three genes ultimately regulate synaptic plasticity and excitation/inhibition balance |

| Chromatin Remodeling | Indirect regulation via mTOR-EP300 axis | Direct phosphorylation of chromatin modifiers | Limited direct role; downstream effects on activity-dependent transcription | Convergence on transcriptional networks controlling neuronal differentiation |

| Neuronal Morphogenesis | Controls soma size, dendritic arborization via mTOR | Regulates neuronal differentiation and migration | Shapes dendritic spine structure and stability | Coordinated regulation of neuronal cytoarchitecture and connectivity |

| Cross-Regulatory Interactions | Expression modulated by DYRK1A activity | Phosphorylates transcription factors regulating PTEN expression | Transcriptional regulation by PTEN and DYRK1A targets | Forms an interconnected regulatory network with feedback loops |

The pleiotropic nature of these ASD risk genes extends to their influences on brain development trajectories. Recent evidence indicates that the polygenic architecture of ASD can be decomposed into genetically correlated factors associated with different developmental profiles [10]. One genetic factor is linked to early childhood diagnosis and lower social-communication abilities, while another factor associates with later diagnosis and increased mental health challenges in adolescence [10]. This developmental stratification of genetic risk may reflect the differential impacts of genes within neurodevelopmental networks, with some influencing early circuit formation (like SHANK3) and others affecting later maturation processes (like DYRK1A-mediated transcriptional regulation).

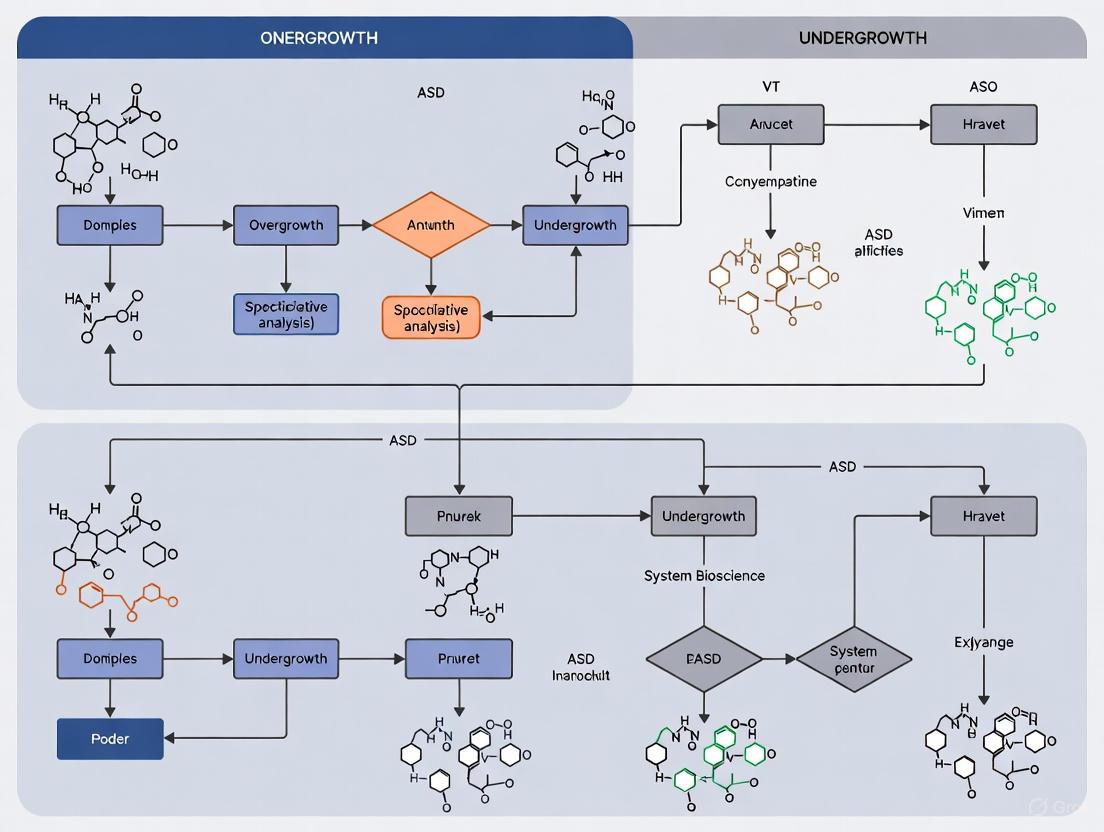

Figure 1: Pleiotropic Pathways Converging on Core ASD Phenotypes. PTEN (yellow), DYRK1A (red), and SHANK3 (green) influence overlapping neurodevelopmental processes through distinct molecular mechanisms. PTEN regulates processes via mTOR signaling; DYRK1A acts through transcription factor (TF) phosphorylation and NMDA receptor modulation; SHANK3 serves as a synaptic organizer. These convergent pathways ultimately contribute to ASD-related phenotypes (blue).

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Model Systems for Functional Validation

The functional characterization of PTEN, DYRK1A, and SHANK3 has employed diverse model systems, each offering distinct advantages for probing ASD pathogenesis. Traditional animal models, particularly rodents, have been indispensable for elucidating the roles of these genes in brain development and behavior. PTEN knockout mice exhibit macrocephaly, neuronal hypertrophy, and social deficits, replicating key features of human PTEN-associated ASD [12]. Similarly, DYRK1A haploinsufficient mice show impaired cognitive function and reduced brain size, while SHANK3-deficient models display repetitive behaviors and social interaction deficits, alongside specific synaptic impairments [12].

While invaluable, animal models cannot fully recapitulate human-specific aspects of neurodevelopment, such as protracted neuronal maturation and human-specific transcriptional programs [12]. To address these limitations, human stem cell-based models have emerged as powerful complementary systems. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from patients with PTEN, DYRK1A, or SHANK3 mutations can be differentiated into 2D neuronal cultures or 3D brain organoids, providing human-specific platforms for investigating disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions [12]. These systems allow researchers to study the impact of genetic variants during critical developmental windows and test patient-specific pharmacological responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating ASD Risk Genes

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Pten conditional knockout mice; Dyrk1a haploinsufficient mice; Shank3 mutant mice | Behavioral phenotyping, circuit analysis, electrophysiology | Social deficits, repetitive behaviors, synaptic physiology, brain connectivity alterations |

| iPSC-Derived Models | Patient-derived iPSCs; CRISPR-corrected isogenic controls; cortical organoids | Human neuronal development, transcriptomic profiling, drug screening | Altered neuronal differentiation, transcriptional dysregulation, patient-specific therapeutic responses |

| Antibodies | Anti-PTEN phosphospecific antibodies; Anti-DYRK1A monoclonal antibodies; Anti-SHANK3 postsynaptic density markers | Protein localization, expression quantification, post-translational modifications | Subcellular distribution, expression changes in mutant models, protein-protein interactions |

| Molecular Reporters | mTOR activity biosensors; Calcium indicators (GCaMP); Synaptic markers (GFP-tagged PSD95) | Live imaging of signaling dynamics, synaptic activity, neuronal morphology | Pathway hyperactivity, altered calcium signaling, dendritic spine abnormalities |

| Gene Manipulation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 kits; shRNA knockdown vectors; Conditional Cre-lox systems | Gene editing, functional validation, cell-type specific deletion | Causality establishment, rescue experiments, cell-autonomous versus non-autonomous effects |

Experimental Workflow for Mechanistic Studies

A standardized experimental approach for validating ASD gene function typically begins with comprehensive genetic characterization using whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing to identify pathogenic variants [11] [8]. Following variant identification, functional validation employs a multi-tiered strategy including in vitro assays in neuronal cell lines, electrophysiological assessments in primary neurons or brain slices, and behavioral characterization in animal models. For synaptic proteins like SHANK3, critical experiments include immunocytochemistry to visualize dendritic spine morphology, electrophysiology to measure miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs), and analysis of protein complexes through co-immunoprecipitation [11] [13]. For regulatory proteins like DYRK1A and PTEN, transcriptomic profiling (RNA-seq) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq) help identify downstream target genes and affected pathways [13].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for ASD Gene Validation. A multi-stage approach for characterizing ASD risk genes begins with Gene Discovery through sequencing, progresses through In Vitro and Cellular models for mechanistic studies, utilizes In Vivo systems for functional assessment, and culminates in Therapeutic development. WES: whole-exome sequencing; WGS: whole-genome sequencing.

Comparative Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

The pathogenic mechanisms of PTEN, DYRK1A, and SHANK3 highlight both shared and distinct approaches to therapeutic intervention. PTEN loss-of-function leads to constitutive activation of the mTOR pathway, suggesting potential utility for mTOR inhibitors like rapamycin in normalizing synaptic function and neuronal growth [8]. DYRK1A haploinsufficiency may be amenable to pharmacological approaches that enhance its kinase activity or modulate downstream pathways, although this strategy remains exploratory. SHANK3 deficiency represents a particular challenge, as it involves structural synaptic defects that may require early developmental intervention or gene therapy approaches [12].

Notably, these genes illustrate the complex relationship between genetic lesions and brain size in ASD. PTEN mutations typically cause macrocephaly through mTOR-mediated cellular hypertrophy, while DYRK1A mutations lead to microcephaly via impaired neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation [9] [8]. SHANK3 mutations generally do not cause dramatic changes in brain volume but specifically disrupt synaptic connectivity and function [11]. These divergent effects on neuroanatomy underscore the precision required in therapeutic targeting, as interventions must address pathway-specific perturbations.

Recent evidence also indicates that the effects of these risk genes extend beyond the formal ASD diagnosis. Carriers of pathogenic variants in high-confidence ASD genes show modest but significant decreases in fluid intelligence, educational attainment, and socioeconomic outcomes, even in the absence of diagnosis [9]. These findings emphasize the importance of studying variant effects across the entire phenotypic spectrum rather than focusing solely on categorical diagnoses, and highlight the need for supportive interventions that address broader functional impacts.

The comparative analysis of PTEN, DYRK1A, and SHANK3 reveals both the complexity and convergence of pathogenic mechanisms in ASD. While each gene has distinct molecular functions, they ultimately disrupt overlapping neurodevelopmental processes involving synaptic regulation, neuronal growth, and network formation. Understanding these convergent pathways provides a strategic framework for developing targeted interventions that may benefit multiple genetic forms of ASD. Future research directions should include comprehensive analysis of gene-gene interactions within regulatory networks, developmental stage-specific investigations of pathogenic mechanisms, and personalized therapeutic approaches based on genetic profiling and human cellular models. As our knowledge of the genetic landscape of ASD expands, comparative analyses of high-confidence risk genes will continue to illuminate shared pathogenic hubs that represent promising targets for therapeutic development.

The trajectory of brain growth in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a central focus in neurodevelopmental research, with profound implications for understanding underlying mechanisms and developing targeted interventions. The scientific community is divided between two principal models: one proposing a transient phase of early brain overgrowth followed by normalization, and another suggesting persistent overgrowth that continues into later life stages. This debate is complicated by ASD's exceptional heterogeneity, with research increasingly indicating that distinct subgroups may follow unique neurodevelopmental paths. Resolving this dichotomy is critical, as each trajectory suggests different biological mechanisms, windows for intervention, and relationships with clinical outcomes.

A key stratifying factor is the presence of macrocephaly (head circumference above the 97th percentile), which affects approximately 20% of individuals with ASD and often coincides with more severe clinical symptoms [15]. This review systematically compares the evidence for transient versus persistent brain overgrowth models, synthesizing quantitative data from longitudinal neuroimaging studies, detailing the experimental methodologies that underpin this research, and exploring the molecular pathways potentially driving atypical brain growth in ASD.

Comparative Analysis of Brain Growth Trajectories

Evidence for Transient Brain Overgrowth

The transient overgrowth hypothesis posits that brain volume in ASD is near-typical at birth, undergoes a period of accelerated growth during early childhood, and then normalizes or shows reduced volume relative to typically developing peers by adolescence or adulthood. This model draws substantial support from cross-sectional and some longitudinal MRI studies.

A seminal 2025 study analyzing the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) dataset provided compelling evidence for a dynamic developmental shift. The research, which included 301 individuals with ASD and 375 typically developing controls (TDCs) aged 8-18 years, revealed that during early adolescence, ASD participants showed positive gray matter volume (GMV) deviations relative to TDCs. This pattern reversed in late adolescence, shifting to negative GMV deviations, suggesting a trajectory from overgrowth to delayed maturation [16]. The brain regions most affected by this shift included the superior temporal sulcus, cingulate gyrus, insula, and superior parietal lobule—areas critically involved in social cognition and attention [16].

This trajectory is thought to reflect an underlying disruption in typical neurodevelopmental programming, potentially involving early overproduction of neurons and synapses followed by atypical pruning processes. Network diffusion modeling from the same study demonstrated that functional brain networks constrain how these atypical morphological patterns develop and spread across the brain over time [16].

Evidence for Persistent Brain Overgrowth

In contrast, the persistent overgrowth model contends that brain enlargement remains evident beyond early childhood into adolescence and adulthood, particularly in a subset of individuals with ASD. The Autism Phenome Project, a major longitudinal study, found that boys with ASD and disproportionate macrocephaly continued to have enlarged brains until at least 13 years of age [15]. This pattern of persistent enlargement has been documented in other studies as well, with some research showing increased brain volume in adolescents and adults with ASD [15].

A meta-analysis of 44 MRI and 27 head circumference studies concluded that while brain overgrowth and macrocephaly in ASD are most pronounced at early ages, they remain detectable across all age groups [15]. This suggests that for a significant subgroup of individuals with ASD, brain overgrowth is not a transient phenomenon but an enduring neuroanatomical feature. Neuroanatomical studies further indicate that this persistent overgrowth may affect the brain globally or may show regional specificity, with some reports highlighting disproportionate enlargement in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, or specific structures like the amygdala and hippocampus [15].

Table 1: Key Evidence Supporting Transient versus Persistent Overgrowth Models

| Aspect of Evidence | Transient Overgrowth Model | Persistent Overgrowth Model |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Trajectory | Early overgrowth followed by normalization or volume reduction | Sustained overgrowth continuing into adolescence/adulthood |

| Primary Supporting Studies | ABIDE dataset analysis (2025) [16]; Courchesne et al. studies [15] | Autism Phenome Project [15]; Hazlett et al. studies [15] |

| Age of Peak Deviation | Early childhood (before age 5) | Variable: childhood, adolescence, or persistent across lifespan |

| Macrocephaly Association | Often present in early childhood only | Typically persistent, affecting ~20% of ASD cases [15] |

| Regional Specificity | Superior temporal sulcus, cingulate gyrus, insula, superior parietal lobule [16] | Frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes; amygdala; hippocampus [15] |

Confounding Factors and Methodological Considerations

The interpretation of brain growth trajectories in ASD is complicated by several methodological factors. Cross-sectional studies, which compare different individuals at different ages, are vulnerable to sampling biases and may yield different patterns than longitudinal studies that track the same individuals over time [15]. Additionally, variations in image acquisition protocols, segmentation algorithms, and statistical controls for intracranial volume can significantly influence results [17].

Normal brain development follows complex, nonlinear trajectories characterized by early increases in cortical gray matter volume followed by post-childhood decreases, while cerebral white matter volume increases more monotonically into mid-to-late adolescence [17]. These typical patterns must be accounted for when identifying atypical trajectories in ASD.

Table 2: Longitudinal Studies of Brain Development in ASD and Typical Development

| Study / Cohort | Sample Characteristics | Key Findings on Brain Volume Trajectory |

|---|---|---|

| ABIDE Dataset Analysis [16] | 301 ASD vs. 375 TDC, aged 8-18 years | Shift from positive GMV deviations in early adolescence to negative deviations in late adolescence |

| Autism Phenome Project [15] | Longitudinal study of boys with ASD | 15% of boys with ASD had megalencephaly that persisted until at least age 13 |

| dHCP and CHILD Cohorts [18] | Infant brain MRI with follow-up at 18 months | Reduced TBV in first months associated with higher autistic traits at 18 months |

| Four Longitudinal Samples [17] | 391 participants (8-30 years), 852 scans | Typical development: CGMV peaks in childhood, decreases thereafter; CWMV increases until adolescence |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Neuroimaging Acquisition and Processing Protocols

Research on brain growth trajectories in ASD relies heavily on advanced neuroimaging techniques, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The standard experimental workflow involves meticulous image acquisition, processing, and statistical analysis tailored to account for the challenges of neurodevelopmental data.

For studies including infant participants, T1-weighted and T2-weighted MR images are typically acquired on 3.0-T scanners while infants sleep without sedation [19]. In the dHCP and CHILD cohort studies, scans were performed during the perinatal period (late fetal and early infancy) to associate brain structure with later autistic traits measured by the Quantitative Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (Q-CHAT) at 18 months [18]. Participant exclusion criteria often address potential confounds, excluding infants from multiplex pregnancies, those born very preterm, or cases with radiological scores indicating atypical patterns like white matter injury or ventricular dilatation [18].

Image processing employs specialized tools such as the Melbourne Children's Regional Infant Brain (M-CRIB) atlas, which enables accurate segmentation of infant brains in an age-appropriate way that matches parcellations used for older children and adults [20]. Processing pipelines typically involve tissue segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, followed by parcellation into regions of interest. For volumetric analyses, total brain volume (TBV), cortical gray matter volume (CGMV), and cerebral white matter volume (CWMV) are common primary outcomes [17].

Analytical Approaches for Developmental Trajectories

Analyzing brain development requires specialized statistical approaches that can model nonlinear changes over time. Sliding-window approaches stratify participants by age to identify stage-specific patterns [16]. To quantify morphological differences between ASD and control groups, researchers have employed Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to measure distribution deviations (DEV) in gray matter volume, providing a robust metric of morphological connectivity [16].

More advanced analytical frameworks include network diffusion modeling (NDM), which simulates how morphological deviations might spread through functional networks over time. This approach has demonstrated that DEV values of atypical brain regions at preceding age stages can significantly predict subsequent ones, suggesting that intrinsic functional networks constrain anatomical development in ASD [16].

Longitudinal analyses must also carefully account for typical developmental patterns. Studies of typical development have established that intracranial volume (ICV) and whole brain volume (WBV) continue developing through adolescence, following distinct trajectories, with CGMV peaking in childhood then decreasing, while CWMV increases until mid-to-late adolescence before decelerating [17]. These normative trajectories provide essential reference points for identifying atypical development in ASD.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The macrocephalic subgroup of ASD provides a valuable model for investigating the molecular drivers of brain overgrowth. Several overlapping biological processes and signaling pathways have been implicated, affecting fundamental developmental mechanisms.

Biological Processes in Brain Overgrowth

Multiple cellular mechanisms may contribute to brain overgrowth in ASD, including:

- Excess neurogenesis: Increased production of neurons, potentially due to prolonged proliferation or symmetric division of neural progenitor cells [15]

- Decreased apoptosis: Reduced programmed cell death during development, leading to more neurons surviving than typical [15]

- Neuronal hypertrophy: Enlargement of individual neurons rather than increased cell numbers [15]

- Elevated gliogenesis: Increased production or proliferation of glial cells [15]

- Enhanced myelination: Excessive formation of myelin sheaths around neuronal axons [15]

These processes are not mutually exclusive and may occur in combination in different ASD subgroups. For example, studies of prenatal valproate (VPA) exposure models have shown reduced natural apoptosis of neural progenitor cells alongside increased neurogenesis [21].

Key Signaling Pathways

Genetic and epigenetic studies have identified several signaling pathways frequently dysregulated in macrocephalic ASD:

- PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway: A critical regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and survival frequently hyperactivated in ASD with macrocephaly [15]

- PTEN signaling: Tumor suppressor pathway whose loss leads to mTOR activation and increased cell proliferation [15]

- WNT/β-catenin pathway: Essential for neural patterning and progenitor cell proliferation; often dysregulated in ASD [15]

- SHH signaling: Controls cerebellar development and neural tube patterning; implicated in some ASD forms [15]

These pathways form a complex regulatory network that coordinates brain growth during development, with mutations in any node potentially disrupting typical scaling mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ASD Brain Growth Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Application | Function/Utility | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0-T MRI Scanner | Neuroimaging acquisition | High-resolution structural imaging of brain volume | Volumetric analysis across development [19] [18] |

| M-CRIB Atlas [20] | Infant brain segmentation | Age-appropriate parcellation of infant brain regions | Longitudinal studies from infancy to adolescence |

| Doublecortin (DCX) Antibodies | Histological analysis | Marker of newly generated and immature neurons | Assessing neurogenesis in postmortem tissue [22] |

| ABIDE Dataset [16] | Large-scale analysis | Pre-existing multi-site neuroimaging data | Testing developmental trajectory models |

| Network Diffusion Modeling [16] | Computational framework | Predicts spread of morphological changes | Modeling how functional networks constrain development |

The debate between transient and persistent brain overgrowth in ASD reflects the condition's inherent heterogeneity rather than contradictory findings. Current evidence suggests that both trajectories exist in different ASD subgroups, with the macrocephalic subgroup more likely to show persistent overgrowth while other subgroups may exhibit transient enlargement or even typical brain volume throughout development.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs that track the same individuals from infancy through adulthood, combined with advanced genetic stratification to identify distinct biological subtypes. This approach will ultimately enable more precise mapping of brain growth trajectories to underlying molecular mechanisms and clinical outcomes, moving the field beyond one-size-fits-all models toward personalized understanding of neurodevelopment in ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by significant heterogeneity in both its biological underpinnings and clinical presentation. Within this heterogeneity, patterns of early physical and brain growth have emerged as potentially crucial biomarkers for identifying distinct ASD subtypes. The concept of Early Generalized Overgrowth (EGO) has gained substantial empirical support, describing a phenomenon of accelerated growth in head circumference, height, and weight within the first years of life [23] [24]. Concurrently, emerging evidence reveals a contrasting pattern of early undergrowth in a different ASD subgroup [18] [25]. This comparative analysis examines the evidence for both overgrowth and undergrowth models, their relationship to clinical severity, and the underlying molecular mechanisms. Understanding these divergent growth trajectories is fundamental for advancing precision medicine in autism research and therapeutic development.

Defining Early Generalized Overgrowth: Core Concepts and Trajectory

Early Generalized Overgrowth (EGO) in ASD is characterized by a synchronized acceleration in the development of multiple somatic measures rather than an isolated enlargement of head circumference. The trajectory follows a specific sequence: increased length/height typically emerges around 4 months of age, followed by accelerated head circumference growth between 8-10 months, and increased weight by approximately 11 months [23] [24]. This pattern suggests a generalized dysregulation of growth mechanisms affecting both neural and non-neural tissues during critical early developmental windows.

The prevalence of extreme EGO is significantly higher in boys with ASD (18.0%) compared to typically developing community controls (3.4%) [23]. This growth pattern appears specific to ASD, as other clinical comparison groups (e.g., global developmental delay) do not exhibit the same consistent overgrowth profile [26]. The phenomenon highlights the importance of investigating factors responsible for coordinated development of neural and skeletal systems in ASD, moving beyond isolated focus on brain development.

Comparative Analysis: EGO versus Early Undergrowth Models

Recent large-scale neuroimaging studies utilizing normative modeling approaches have identified at least two distinct ASD subgroups with opposing brain morphology profiles, herein referred to as the "H" (high-growth) and "L" (low-growth) subtypes [25]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these contrasting biological subtypes.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of ASD Growth Subtypes

| Feature | EGO/"H" Subtype (Overgrowth) | "L" Subtype (Undergrowth) |

|---|---|---|

| Brain Volume | Larger regional brain volumes [25] | Smaller regional brain volumes [25] |

| Postnatal Total Brain Volume | Increased [27] | Reduced [18] |

| Head Circumference | Enlarged after 9.5 months [23] [26] | Not enlarged [18] |

| Body Growth | Generalized overgrowth (height/weight) [23] | Less pronounced physical differences |

| Prevalence of Extreme Phenotype | ~18% in boys with ASD [23] | Higher abnormality rates across brain regions [25] |

| Associated Autistic Traits | More severe social deficits [23] [26] | Higher Q-CHAT scores [18] |

| Functional Outcomes | Lower adaptive functioning [23] [26] | Correlated with family history of ASD [18] |

This dichotomous presentation suggests different underlying biological mechanisms and developmental trajectories. The "L" subtype demonstrates that reduced brain volume in the first months of life associates with higher autistic trait scores on the Q-CHAT at 18 months, particularly in cohorts enriched for familial autism history [18]. This undergrowth pattern appears independent of the overgrowth trajectory, supporting the existence of multiple biological pathways to ASD.

Linking Growth Patterns to Clinical Severity and Functional Outcomes

The relationship between growth patterns and clinical outcomes represents a critical dimension for understanding the prognostic significance of these biomarkers. Children exhibiting the EGO phenotype show distinct clinical profiles, with larger body size at birth and postnatal overgrowth independently associating with poorer social, verbal, and nonverbal skills at age 4 years [23]. Those in the top 10% for physical size during infancy exhibit greater severity of social deficits and lower adaptive functioning [26].

Brain overgrowth shows particularly strong correlations with symptom severity. Children with the most severe ASD social symptoms demonstrate brains up to 41% larger than controls, with the degree of embryonic brain cortical organoid enlargement directly correlating with later social symptom severity (r = 0.719-0.873) [27]. This relationship follows a dose-response pattern where "the larger the embryonic BCO size in ASD, the more severe the toddler's social symptoms" and the more reduced the language ability and IQ [27].

Regional brain analyses further refine these associations. In the "H" subtype, the volume of the isthmus cingulate cortex directly correlates with autistic mannerisms, potentially reflecting its slower post-peak volumetric decline during typical development [25]. These findings position growth biomarkers as potentially valuable tools for predicting clinical trajectories and identifying individuals at risk for more significant support needs.

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Longitudinal Growth Studies

Retrospective cohort designs using medical record data have been instrumental in establishing EGO trajectories. The typical protocol involves:

- Data Collection: Head circumference, height, and weight measurements extracted from medical records spanning birth to 24 months [23] [24]

- Participant Groups: Children with ASD compared with typically developing community controls and other developmental delay groups [26]

- Assessment Points: Longitudinal measurements at birth, 4-6 months, 8-10 months, 12 months, and 24 months [23]

- Outcome Measures: Standardized assessments of social functioning (ADOS), cognitive skills (Mullen Scales), and adaptive behavior (Vineland) at age 2-4 years [23] [26]

This approach demonstrates that boys with autism become significantly longer by age 4.8 months, develop larger head circumference by 9.5 months, and weigh more by 11.4 months compared to typically developing controls [26].

Brain Organoid Models

Human brain cortical organoids (BCOs) derived from induced pluripotent stem cells provide unprecedented insight into embryonic origins of growth abnormalities:

- Organoid Generation: BCOs created from iPSCs derived from blood samples of children with ASD and controls [27]

- Size Measurement: Analysis of 4,910 individual BCOs with approximately 196 organoids measured per subject [27]

- Growth Tracking: Size changes monitored between 1- and 2-months of organoid development [27]

- Molecular Analysis: Assessment of neurogenesis markers and Ndel1 enzyme activity [27]

This experimental system revealed that ASD organoids were 39-41% larger than controls and grew at nearly 3 times faster rates, with accelerated neurogenesis and altered Ndel1 activity [27].

Normative Modeling of Neuroimaging Data

Large-scale cross-cultural neuroimaging approaches address heterogeneity through normative modeling:

- Datasets: Combining ABIDE and China Autism Brain Imaging Consortium (CABIC) datasets [25]

- Normative References: Using Lifespan Brain Chart Consortium data for percentile-based comparisons [25]

- Statistical Clustering: Spectral clustering of Out-of-Sample centile scores to identify biological subtypes [25]

- Feature Selection: Support Vector Machines with Recursive Feature Elimination to identify key differentiating regions [25]

This method identified the two distinct neurostructural subtypes ("H" and "L") with specific regional vulnerability patterns [25].

Molecular Mechanisms: Signaling Pathways and Biomarkers

The molecular underpinnings of aberrant growth patterns in ASD involve dysregulated cellular processes during critical developmental windows. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway implicated in brain overgrowth:

Diagram 1: Ndel1 Signaling Pathway in Brain Overgrowth

The enzyme Ndel1 emerges as a crucial regulator, with its activity highly correlated with brain organoid growth rate and size (r > 0.7) [27]. Altered Ndel1 function disrupts typical cell cycle regulation, leading to increased neural progenitor proliferation and accelerated neurogenesis during embryogenesis. This results in excessive neuron production and disrupted migration patterns, ultimately manifesting as macroscopic brain overgrowth and more severe clinical symptoms [27].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for ASD Growth Studies

| Resource | Application | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Brain Cortical Organoids | Modeling embryonic brain development [27] | Reveals prenatal origins of overgrowth; enables drug screening |

| Ndel1 Activity Assays | Quantifying enzyme function [27] | Biomarker for overgrowth risk; mechanistic studies |

| Lifespan Brain Charts | Normative neuroimaging reference [25] | Identifies deviations from typical growth trajectories |

| ddPCR/NGS Platforms | CSF ctDNA analysis [28] | Detects brain tumor-derived mutations; monitors treatment response |

| Quiet Ego Scale (QES) | Assessing psychological traits [29] | Measures coping strategies in parents of children with ASD |

| SAETBQ Questionnaire | Evaluating bias awareness [30] | Studies metacognitive aspects in ASD caregivers |

These resources enable multidimensional investigation of growth mechanisms from molecular to systems levels. The integration of biological and psychological measures is particularly valuable for understanding gene-environment interactions and family dynamics in ASD.

The compelling evidence for both EGO and undergrowth models in ASD underscores the biological heterogeneity of the condition and necessitates a precision medicine approach. Growth patterns represent quantifiable, early biomarkers that can stratify individuals into more biologically homogeneous subgroups with distinct clinical trajectories and treatment needs. Future research should prioritize:

- Prospective longitudinal studies integrating molecular, neuroimaging, and behavioral measures from infancy

- Drug development targeting specific growth pathways, particularly the Ndel1 signaling cascade

- Refined normative models incorporating genetic, environmental, and developmental factors

- Clinical translation of growth biomarkers for early identification and intervention planning

The recognition of multiple growth subtypes in ASD moves the field beyond one-size-fits-all approaches and provides a roadmap for developing targeted interventions based on individual biological profiles.

From Bench to Biomarker: Animal, Cellular, and Imaging Models in ASD Research

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a group of complex neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by challenges in social communication, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors. With a global prevalence of approximately 1-3% and a pronounced male-to-female ratio of 4.2:1, ASD has emerged as a significant public health concern [15] [31] [32]. The disorder exhibits extensive clinical and genetic heterogeneity, with hundreds of identified risk genes and diverse pathological mechanisms [15] [33]. Genetically engineered mouse models have become indispensable tools for dissecting the causal relationships between genetic risk factors and the development of ASD-related behaviors and neuropathology [33] [34].

These models are particularly valuable for studying both monogenic forms of ASD, where mutations in a single gene (such as SHANK3, MECP2, or FMR1) are sufficient to cause the disorder, and syndromic forms of ASD, which occur as part of broader genetic syndromes like Fragile X syndrome or tuberous sclerosis complex [33] [34] [32]. The complex interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental influences during critical developmental windows underscores the importance of animal models in elucidating ASD pathophysiology [35]. By providing opportunities for direct manipulation of brain regions and circuits, these models enable researchers to test precise functional hypotheses that cannot be addressed in human studies [33].

Model Validation Criteria and Genetic Landscape

Validation Frameworks for ASD Mouse Models

Animal models of psychiatric disorders are traditionally evaluated using three core validity criteria, which have been adapted for ASD research [33] [35]:

Construct Validity: Refers to how well the model recapitulates the known etiology of the disorder. For ASD models, this typically involves mimicking genetic mutations observed in human patients (e.g., mutations in SHANK3, MECP2, or TSC1/2) and their molecular consequences [33].

Face Validity: Describes the model's resemblance to clinical features of ASD, particularly core behavioral symptoms such as social interaction deficits, communication impairments, and repetitive behaviors. This may also include physiological biomarkers when available [33] [35].

Predictive Validity: Indicates the model's ability to accurately predict responses to therapeutic interventions that are effective in humans. This aspect remains challenging due to the limited number of evidence-based pharmacological treatments for core ASD symptoms [33].

Additional considerations include ethological validity (behavioral resemblance), biomarker validity (physiological resemblance), and pathogenic validity (shared disease mechanisms) [33].

Genetic Complexity of ASD

The genetic architecture of ASD encompasses several types of variations, each contributing differently to disease risk:

Table 1: Types of Genetic Variations in ASD

| Variant Type | Prevalence in ASD | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monogenic | ~50-60% of cases have genetic etiology [34] | SHANK3, MECP2, FMR1, TSC1/2 [34] [32] | Single gene mutations with large effect sizes; often associated with syndromic forms |

| Copy Number Variants (CNVs) | ~10% of non-syndromic ASD [33] | 15q13.3 deletion, 16p11.2 duplication [36] | Deletions or duplications of genomic regions containing multiple genes |

| De Novo Variants | Account for substantial fraction of sporadic cases [32] | CHD8, DYRK1A [32] | New mutations absent in parents; more common in paternal age effect |

| Common Variants | Contribute to 17-52% of ASD risk [15] [32] | Polygenic risk scores [32] | Individual small effects that cumulatively increase susceptibility |

According to the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) database, over 1,400 genes have been implicated in ASD to varying degrees of confidence, categorized as "syndromic," "high confidence," "strong candidate," or "suggestive evidence" [15] [35]. This genetic diversity is mirrored by the heterogeneity of clinical presentations, ranging from individuals with low support needs to those requiring constant care [32].

Monogenic ASD Mouse Models: Key Examples and Characteristics

Mouse models targeting specific high-confidence ASD genes have provided crucial insights into molecular and circuit mechanisms underlying autistic behaviors.

Table 2: Key Monogenic Mouse Models of ASD

| Gene Model | Molecular Function | Core Behavioral Phenotypes | Neurobiological Findings | Model Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmr1 KO [33] [35] | RNA-binding protein regulating synaptic protein translation | Social deficits, repetitive behaviors, anxiety [35] | Enhanced mGluR-dependent LTD, dendritic spine abnormalities | High construct and face validity [35] |

| Mecp2 KO [33] [35] | Epigenetic regulator of gene expression | Social deficits, repetitive behaviors, motor abnormalities [35] | Altered synaptic transmission, impaired cortical plasticity | High construct and face validity [35] |

| Shank3 KO [33] [35] [34] | Postsynaptic scaffolding protein | Social deficits, repetitive behaviors, anxiety [35] | Deficits in glutamate receptor function, altered spine morphology | High construct and face validity; responsive to oxytocin [35] |

| Ube3a [33] [34] | Ubiquitin ligase involved in synaptic protein degradation | ASD-like behaviors, seizures | Defects in experience-dependent synaptic plasticity | Strong construct validity |

| Pten KO [33] [34] | Phosphatase regulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway | Macrocephaly, social deficits, anxiety | Neuronal hypertrophy, disrupted connectivity | High construct validity |

| Tsc1/2 KO [35] | GTPase-activating proteins regulating mTOR pathway | Social deficits, abnormal sensory responses [35] | Neuronal overgrowth, synaptic dysfunction | High predictive validity - responsive to mTOR inhibitors [35] |

| Cntnap2 KO [35] | Neuronal adhesion molecule | Hyperactivity, epileptic seizures, social deficits [35] | Cortical migration defects, reduced interneurons | High construct validity [35] |

| Nlgn3 R451C [35] | Postsynaptic cell adhesion protein | Repetitive behavior, impaired social interactions [35] | Altered inhibitory transmission, increased excitatory transmission | High construct validity [35] |

Emerging Insights from Monogenic Models

Recent studies comparing multiple monogenic models have revealed both shared and distinct circuit abnormalities. A 2025 study examining three different ASD mouse models (Tbr1+/–, Nf1+/–, and Vcp+/R95G) found that while each mutation caused unique connectivity alterations, sensory regions—particularly the piriform cortex—were consistently impaired across all models [37]. All three mutants exhibited common olfactory discrimination impairments, and manipulation of piriform cortex activity altered social behavior patterns, highlighting this region's potential role in ASD-linked circuit dysfunction [37].

Another significant advancement is the development of a comprehensive library of 63 genetically engineered mouse embryonic stem cell lines, each carrying a specific ASD-linked copy number variation (CNV) [36]. This resource enables systematic comparison of how different mutations affect neuronal development and function, revealing that diverse CNVs disrupt protein production and quality control mechanisms in neurons, particularly through mTOR and EIF4E pathways [36].

Syndromic ASD Models: Recapitulating Complex Genetic Disorders

Syndromic forms of ASD occur in the context of broader genetic syndromes where autism is one component of the clinical presentation.

Fragile X Syndrome (FMR1)

Fragile X syndrome represents the most common monogenic cause of ASD, resulting from a trinucleotide repeat expansion in the FMR1 gene that silences expression of its protein product, FMRP [33] [34]. Fmr1 knockout mice recapitulate several core features of the human syndrome, including social deficits, repetitive behaviors, and cognitive impairments [35]. At the neurobiological level, these mice exhibit enhanced metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)-dependent long-term depression (LTD), dendritic spine abnormalities, and synaptic plasticity deficits [33] [35]. The strong construct and face validity of this model has facilitated preclinical testing of therapeutic strategies targeting mGluR signaling pathways [33].

Rett Syndrome (MECP2)

Rett syndrome, primarily affecting females, is caused by mutations in the X-linked MECP2 gene encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2, an epigenetic regulator of gene expression [33] [34]. Mecp2 knockout mice develop normally for the first few weeks of life before exhibiting progressive neurological symptoms including social withdrawal, repetitive movements, motor impairments, and breathing abnormalities reminiscent of the human disorder [33] [35]. Neuropathological findings include reduced dendritic complexity, altered synaptic transmission, and impaired cortical plasticity [33]. This model has been instrumental in establishing the critical role of MeCP2 in maintaining neuronal function after the initial period of normal development.

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC1/TSC2)

Tuberous sclerosis complex results from mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2 genes, which encode proteins that form a complex inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway [35]. Mouse models with mutations in these genes exhibit several ASD-relevant behaviors including social deficits and abnormal responses to sensory stimuli [35]. At the cellular level, these models demonstrate neuronal overgrowth and synaptic dysfunction attributable to dysregulated mTOR signaling [35]. Importantly, these models show strong predictive validity, as treatment with mTOR inhibitors like rapamycin or everolimus ameliorates social deficits in these animals [35].

Brain Phenotypes: Overgrowth and Undergrowth in ASD Models

A notable feature of ASD is the heterogeneity in brain growth patterns, with some individuals exhibiting macrocephaly (enlarged head circumference) and others microcephaly (reduced head circumference).

Macrocephaly Models

Approximately 20% of children with ASD have macrocephaly, often corresponding with megalencephaly (brain enlargement) [15]. This subgroup typically presents with more severe symptoms, including lower IQ, delayed language onset, and increased social deficits [15]. The PTEN knockout mouse model exemplifies this phenotype, exhibiting pronounced macrocephaly due to neuronal hypertrophy and disrupted connectivity resulting from dysregulated PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [33] [34]. These models demonstrate that brain overgrowth can originate from various cellular mechanisms, including excess neurogenesis, decreased cell death, neuronal hypertrophy, and elevated myelination [15].

The developmental trajectory of brain overgrowth in ASD remains controversial. While some studies suggest precocious growth during early childhood followed by normalization during adolescence, longitudinal research indicates that boys with ASD and disproportionate macrocephaly may maintain enlarged brains until at least 13 years of age [15]. Neuroanatomical studies reveal both generalized overgrowth of frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and regional specificity affecting structures like the amygdala and hippocampus [15].

Microcephaly Models

In contrast to macrocephaly models, some ASD mouse models exhibit reduced brain size. For example, certain models involving impaired synaptic function or neuronal migration demonstrate microcephaly alongside ASD-like behaviors [15]. Interestingly, a 2025 study examining perinatal brain growth and autistic traits found that reduced total brain volume in the first two months of life was associated with higher numbers of autistic traits at 18 months [38]. This suggests that early brain undergrowth, rather than overgrowth, may predict later emergence of ASD symptoms in some cases, highlighting the complex relationship between brain size and ASD phenotypes.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Gene Editing Technologies

The creation of genetically engineered mouse models has been revolutionized by advances in gene editing technologies:

Gene Editing Technologies Evolution

Table 3: Gene Editing Technologies for ASD Mouse Models

| Technology | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) [34] | Fusion of zinc finger DNA-binding domains with DNA cleavage domain | First targeted nuclease approach | High cost, complex design, off-target effects |

| Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) [34] | Fusion of TALE DNA-binding domains with DNA cleavage domain | Improved specificity over ZFNs | Still complex and costly to design |

| CRISPR/Cas9 [34] | RNA-guided DNA endonuclease system using Cas9 protein and guide RNA | Easy design, high efficiency, cost-effective | Potential off-target effects requiring careful validation |

| Cre-loxP System [34] | Cre recombinase mediates site-specific recombination between loxP sites | Precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression | Requires generation of complex mouse lines |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ASD Model Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Engineered Cell Lines | Library of 63 mouse embryonic stem cell lines with ASD-linked CNVs [36] | Standardized models for comparing effects of different mutations |

| Reporter Lines | Thy1-YFP transgenic mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFP)HJrs/J) [37] | Visualization of neuronal morphology and connectivity |

| Behavioral Assessment Tools | Three-chamber social test, ultrasonic vocalization recording, repetitive behavior assays | Quantification of ASD-relevant behaviors |

| Connectivity Mapping Platforms | BM-auto (Brain Mapping with Auto-ROI correction) [37] | AI-powered analysis of whole-brain connectivity using deep learning |

| Single-Cell Transcriptomics | Single-cell RNA sequencing (37,000+ cells in CNV study) [36] | Identification of cell-type-specific molecular alterations |

| Neural Circuit Manipulation | Chemogenetics (DREADDs), optogenetics | Testing causal relationship between circuit activity and behavior |

Signaling Pathways in Monogenic ASD Models

Multiple signaling pathways have been implicated across different monogenic ASD models, revealing potential convergent mechanisms:

Signaling Pathways in Monogenic ASD

Comparative Analysis: Strengths and Limitations Across Model Systems

While genetically engineered mouse models have significantly advanced our understanding of ASD pathophysiology, each model system presents unique advantages and limitations.

Model Organism Considerations

Mouse models offer several key advantages for ASD research, including well-established genetic manipulation techniques, relatively low maintenance costs, and rapid reproduction cycles that facilitate studies across developmental stages [33] [32]. Their mammalian brain organization shares fundamental similarities with humans, particularly in basic circuit organization and neurotransmitter systems [32]. However, significant limitations include species-specific differences in brain complexity, particularly in cortical expansion and organization, and the challenge of fully recapitulating human-specific social and cognitive behaviors [32].

Emerging Complementary Approaches

Human stem cell-based models, including 2D cultures and 3D organoids, have emerged as valuable complements to animal models by addressing some of these limitations [32]. These systems enable study of human-specific features of neuronal development and function, including protracted maturation timelines and species-specific transcriptional programs [32]. The ability to generate patient-specific cells also supports personalized therapeutic approaches [32]. However, these in vitro systems currently lack the complex circuit-level organization and sensory-motor integration present in intact organisms [32].

Genetically engineered mouse models have proven indispensable for elucidating the neurobiological mechanisms underlying monogenic and syndromic forms of ASD. The continuing refinement of these models, coupled with advanced genetic tools and analytical approaches, promises to further enhance their utility in both basic research and therapeutic development.

Future directions in the field include developing more sophisticated models that incorporate multiple genetic risk factors to better reflect the polygenic nature of most ASD cases, creating humanized models that better recapitulate human-specific aspects of brain development and function, and implementing high-throughput screening approaches to identify novel therapeutic targets across different genetic subtypes [32]. The integration of data from multiple model systems—including mouse models, stem cell-based platforms, and human clinical studies—will be essential for advancing our understanding of ASD and developing effective interventions for affected individuals.

As research progresses, the comparative analysis of overgrowth and undergrowth phenotypes across different ASD models will continue to provide valuable insights into the diverse biological pathways that can lead to similar behavioral manifestations, ultimately supporting the development of more targeted, personalized treatment approaches for this complex spectrum of disorders.

The pursuit of accurate human models for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has led to the pivotal adoption of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived brain organoids. These three-dimensional structures recapitulate early human brain development, providing an unprecedented window into the embryonic pathogenesis of complex neurodevelopmental disorders [39] [40]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of brain organoid models, particularly in the context of a broader thesis on comparative analysis of overgrowth and undergrowth in ASD research. We synthesize experimental data, protocols, and reagent toolkits to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of ASD Brain Organoid Models: Overgrowth vs. Undergrowth Phenotypes

Modeling ASD requires capturing its profound heterogeneity, including extremes in early brain development such as macrocephaly (overgrowth) and microcephaly (undergrowth). Brain organoids derived from patient iPSCs have successfully replicated key aspects of these phenotypes, offering a platform for comparative mechanistic studies [39] [41].

Modeling Early Brain Overgrowth (Macrocephaly): A seminal study using iPSCs from ASD individuals with early brain overgrowth revealed a consistent cellular phenotype: neural progenitor cells (NPCs) displayed increased proliferation [42]. This was linked to the dysregulation of a β-catenin/BRN2 transcriptional cascade. Consequently, neurons derived from these iPSCs showed abnormal neurogenesis and reduced synaptogenesis, leading to functional defects in neuronal networks. This model directly connects a prenatal cellular mechanism (excessive proliferation) to a known in vivo pathological trait (early brain overgrowth) [42] [41].

Modeling Brain Undergrowth (Microcephaly): Cerebral organoids have been effectively used to study disorders of small brain size. The protocol detailed by Lancaster et al. was applied to study microcephaly, revealing premature neuronal differentiation at the expense of the progenitor pool, effectively modeling the disease phenotype in a dish [39]. This contrasts with the overgrowth model, highlighting how organoids can capture opposing pathogenic trajectories stemming from distinct genetic disruptions.