Beyond the Spectrum: Decoding Autism Heterogeneity Through Structural and Functional MRI Subtypes

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by significant clinical and biological heterogeneity, which has been a major obstacle in understanding its neurobiology and developing effective, targeted treatments.

Beyond the Spectrum: Decoding Autism Heterogeneity Through Structural and Functional MRI Subtypes

Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by significant clinical and biological heterogeneity, which has been a major obstacle in understanding its neurobiology and developing effective, targeted treatments. This article synthesizes recent advances in neuroimaging that leverage both structural (sMRI) and functional MRI (fMRI) to identify biologically distinct subtypes of ASD. We explore the foundational evidence for brain-based subtypes, detail methodological approaches for their identification—including multimodal data fusion and machine learning—and address the historical challenges in drug development linked to patient heterogeneity. Furthermore, we examine how these neurosubtypes are validated through their correlation with unique genetic profiles, clinical symptom presentations, and behavioral outcomes. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive framework for moving towards a precision medicine approach in autism, paving the way for biologically informed diagnostics and personalized interventions.

The Neurobiological Imperative: Why ASD Subtyping is Essential for Progress

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents one of the most complex challenges in neurodevelopmental psychiatry due to its profound heterogeneity in clinical presentation, underlying biology, and developmental trajectories. This diversity has long hampered efforts to establish reliable biomarkers, develop targeted interventions, and understand the fundamental mechanisms driving the condition. Historically, the diagnosis of ASD has relied exclusively on behavioral observation and clinical assessment, with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) categorizing ASD as a single broad spectrum despite recognizing significant variations in symptom profiles, cognitive abilities, and co-occurring conditions [1]. The clinical heterogeneity of autism manifests across multiple dimensions, including differences in social communication challenges, restricted and repetitive behaviors, sensory processing profiles, cognitive functioning, and the presence of comorbid conditions such as anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The emerging paradigm in autism research recognizes that this clinical diversity reflects distinct biological subtypes with different genetic architectures, neural circuitry profiles, and developmental pathways. Advances in neuroimaging and genetics have begun to deconstruct this heterogeneity by identifying biologically meaningful subgroups that transcend behavioral observations alone. The integration of structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), functional MRI (fMRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and genomic data has enabled researchers to move beyond descriptive phenomenology toward a mechanistic understanding of autism's varied manifestations [2] [1] [3]. This review systematically compares how structural and functional neuroimaging approaches have contributed to identifying ASD subtypes, examining their respective methodologies, findings, limitations, and implications for personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Neuroimaging Approaches to Deconstructing Heterogeneity

Structural MRI: Mapping Brain Anatomy in ASD

Structural MRI provides detailed information about brain anatomy, including cortical thickness, gray matter volume, and overall brain structure. This approach has identified several structural biomarkers associated with ASD, though findings have often been inconsistent due to the disorder's heterogeneity [3]. Early structural studies focused on single anatomical features such as enlarged amygdalae, increased cerebellar size with decreased vermal size, larger caudate nuclei, atypical gyrification, and changes in hippocampal volume and shape [3]. However, these individual biomarkers demonstrated limited classificatory power on their own, prompting a shift toward multivariate approaches that integrate multiple structural parameters.

A novel multivariate classification method using structural MRI data developed a summed total index (TI) that indicates whether an individual's gross morphological pattern aligns more closely with ASD or neurotypical controls [3]. This approach achieved 78.9% classification accuracy in a pilot study, performing comparably to more complex machine learning methods while offering greater transparency and simplicity [3]. Significant structural differences were particularly noted in subcortical gray matter structures and limbic areas, with no significant difference in total brain volume between ASD and control groups [3]. The TI correlated well with the autism quotient (AQ) across groups (R = 0.51), suggesting a relationship between brain structure and behavioral manifestations of autism [3].

Functional MRI: Examining Brain Network Dynamics

Functional MRI, particularly resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI), measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow and oxygenation, providing insights into functional connectivity between different brain regions. This approach has revealed that individuals with ASD often exhibit atypical connectivity patterns, characterized by both local hyperconnectivity and global hypoconnectivity [4]. These functional alterations appear more pronounced in networks critical for social cognition and information integration, including the default mode network (DMN), salience-executive network, and fronto-parietal network [5] [6].

Recent large-scale studies using semi-supervised clustering methods have identified two primary functional connectivity subtypes in ASD: a hyper-connectivity subtype and a hypo-connectivity subtype [4]. These subtypes exhibit distinct connectivity patterns both within and between major brain networks, with the hyper-connectivity subtype showing increased connectivity within major large networks and mixed (both hyper and hypo) connectivity between networks, while the hypo-connectivity subtype displays the opposite pattern [4]. Furthermore, these functional subtypes demonstrate different correlations between connectivity patterns and core ASD symptoms, suggesting they may represent distinct pathophysiological mechanisms with implications for personalized treatment approaches [4].

Multimodal Integration: Combining Structural and Functional Insights

The most recent advances in ASD subtyping have come from approaches that integrate multiple neuroimaging modalities to capture the complex interplay between brain structure and function. One innovative study combined structural and functional MRI data through a skeleton-based white matter functional analysis, enabling voxel-wise function-structure coupling by projecting fMRI signals onto a white matter skeleton [2]. Using white matter low-frequency oscillations (LFOs) as input features for clustering algorithms, this approach identified two distinct neurosubtypes of ASD with unique biomarkers [2].

Subtype 1 displayed significantly lower fractional anisotropy (FA) in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) compared to neurotypical controls, while Subtype 2 exhibited reduced FA in the anterior cingulate cortex, middle temporal gyrus, parahippocampus, and thalamus [2]. Additionally, Subtype 2 had markedly higher mean diffusivity in the middle temporal gyrus, parahippocampus, and thalamus than controls, a pattern not seen in Subtype 1 [2]. The full-scale intelligence quotient (FIQ) and performance IQ (PIQ) scores were also lower for Subtype 2 compared to Subtype 1, demonstrating how neuroimaging-based subtypes can capture meaningful clinical differences [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Structural and Functional MRI Approaches in ASD Subtyping

| Feature | Structural MRI | Functional MRI | Multimodal Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Measures | Cortical thickness, gray matter volume, brain structure | Functional connectivity, network dynamics, brain activity | Both structural and functional coupling |

| Identified Subtypes | Limited consensus on specific subtypes | Hyper-connectivity vs. hypo-connectivity subtypes [4] | Two neurosubtypes with distinct white matter profiles [2] |

| Key Biomarkers | Subcortical gray matter, limbic areas [3] | DMN, frontoparietal, sensory networks [5] [6] | White matter integrity, structure-function coupling [2] |

| Classification Accuracy | 78.9% with multivariate approach [3] | Varies; enhanced with semi-supervised methods [4] | Improved diagnostic prediction compared to general ASD classification [2] |

| Clinical Correlations | Correlates with AQ (R=0.51) [3] | Distinct brain-behavior relationships across subtypes [4] | IQ differences between subtypes [2] |

| Main Advantages | Clear anatomical references, established analysis methods | Direct assessment of brain network function | Comprehensive view of brain organization |

| Limitations | Limited explanatory power for symptoms | Variable reliability, influenced by state factors | Computational complexity, data requirements |

Methodological Approaches in ASD Subtyping Research

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The quality and consistency of neuroimaging data are fundamental to reliable subtype identification. Most recent studies utilize data from large, multi-site datasets such as the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I and II), which collectively provide structural and functional MRI data from thousands of participants across multiple international sites [6] [4]. Standardized preprocessing pipelines are critical for minimizing site-specific variations and ensuring data comparability. Common preprocessing steps typically include motion correction, spatial normalization to standard templates (e.g., MNI152), band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz for fMRI), and regression of confounding signals [5].

For functional connectivity analyses, regions of interest (ROIs) are typically defined using established atlases. For instance, one study utilized the Dosenbach 160 ROIs, which are derived from meta-analyses covering multiple cognitive domains including error processing, default mode, memory, language, and sensorimotor functions [6]. Both static and dynamic functional connectivity features are often extracted, with static functional connectivity strength (SFCS) calculated using Pearson correlation and dynamic functional connectivity assessed through measures such as dynamic conditional correlation (DCC) for capturing instant dynamic FC strength (DFCS) and variance (DFCV) [6].

Feature Extraction and Dimension Reduction

The high dimensionality of neuroimaging data necessitates effective feature reduction strategies to avoid overfitting and enhance interpretability. Different studies have employed various approaches for this purpose. Tensor decomposition methods have been used to extract compressed feature sets from resting-state fMRI data, capturing different brain communities across ASD subtypes [5]. Other common functional features include the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) and fractional ALFF (fALFF), which measure the intensity of spontaneous brain activity [5]. For structural analyses, gray matter volume (GMV) derived from MRI serves as a key feature for evaluating structural variations among subtypes [5].

More advanced dimension reduction techniques include orthonormal projective non-negative matrix factorization (OPNNMF), which has been applied to high-dimensional functional connectivity data to create lower-dimensional representations suitable for clustering [4]. This approach has demonstrated superiority over traditional feature reduction methods when combined with semi-supervised clustering algorithms, yielding more robust and reproducible subtypes [4].

Clustering Algorithms and Validation

The choice of clustering algorithm significantly impacts subtype identification. While traditional unsupervised methods like K-means clustering have been widely used, recent studies have demonstrated the advantages of semi-supervised approaches. The HeterogeneitY through Discriminative Analysis (HYDRA) method incorporates diagnostic labels (ASD vs. controls) to guide the clustering process, resulting in more clinically meaningful and neurobiologically distinct subtypes [4].

Cluster validity is typically assessed through multiple measures, including reliability indices, silhouette scores, and clinical correlation analyses. The optimal number of clusters is determined through systematic evaluation rather than a priori assumptions. For instance, one comprehensive analysis of 1046 participants identified two distinct neural ASD subtypes based on normative modeling of functional connectivity [6], while another study of 5,392 individuals revealed four clinically and genetically distinct subtypes using a person-centered approach [7]. These differences in optimal cluster number highlight how methodological choices and sample characteristics influence subtype identification.

Table 2: Key Clustering Methods in ASD Neuroimaging Research

| Method | Approach | Key Features | Identified Subtypes | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-means Clustering | Unsupervised | Partitions data into K clusters based on distance metrics | Varies by study; typically 2-4 subtypes | Simple implementation, computationally efficient |

| HYDRA [4] | Semi-supervised | Incorporates diagnostic labels to guide clustering | Two subtypes: hyper-connectivity and hypo-connectivity | Enhanced clinical relevance, improved separation |

| Normative Modeling [6] | Individual-level deviation | Quantifies deviations from typical neurodevelopmental trajectories | Two subtypes with opposite deviation patterns | Accounts for developmental effects, personalized |

| Growth Mixture Modeling [8] | Latent trajectory | Identifies subgroups based on longitudinal patterns | Early childhood emergent vs. late childhood emergent trajectories | Captures developmental heterogeneity, temporal dynamics |

| Tensor Decomposition [5] | Multivariate pattern analysis | Extracts compressed feature sets from high-dimensional data | Three subtypes (autism, Asperger's, PDD-NOS) | Captures complex interactions, multimodal integration |

Significantly Identified ASD Subtypes and Their Characteristics

Clinically-Defined Subtypes from Large Cohort Studies

A landmark study analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism using a "person-centered" approach that considered over 230 traits [7]. These subtypes exhibit distinct developmental trajectories, medical, behavioral, and psychiatric traits, and different patterns of genetic variation:

Social and Behavioral Challenges Subtype (37% of participants): Individuals in this group show core autism traits, including social challenges and repetitive behaviors, but generally reach developmental milestones at a pace similar to children without autism. They frequently experience co-occurring conditions like ADHD, anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder alongside autism [7].

Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay Subtype (19% of participants): This group tends to reach developmental milestones, such as walking and talking, later than children without autism, but usually does not show signs of anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors. "Mixed" refers to differences within this group regarding repetitive behaviors and social challenges [7].

Moderate Challenges Subtype (34% of participants): Individuals in this category show core autism-related behaviors but less strongly than those in other groups, and typically reach developmental milestones on a similar track to those without autism. They generally do not experience co-occurring psychiatric conditions [7].

Broadly Affected Subtype (10% of participants): This group faces more extreme and wide-ranging challenges, including developmental delays, social and communication difficulties, repetitive behaviors, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions like anxiety, depression, and mood dysregulation [7].

Neuroimaging-Defined Subtypes

Neuroimaging studies have revealed subtypes that cut across clinical classifications, suggesting distinct neural substrates underlying ASD heterogeneity. One comprehensive analysis of 1046 participants identified two neural ASD subtypes with unique functional brain network profiles despite comparable clinical presentations [6]. One subtype was characterized by positive deviations in the occipital network and cerebellar network, coupled with negative deviations in the frontoparietal network, default mode network, and cingulo-opercular network. The other subtype exhibited an inverse pattern of functional deviations across these networks [6]. These neural subtypes were also associated with distinct gaze patterns assessed by autism-sensitive eye-tracking tasks, demonstrating their behavioral relevance [6].

Another study utilizing semi-supervised clustering on functional connectivity data from approximately 1800 individuals similarly identified two robust subtypes: a hyper-connectivity subtype showing hyper-connectivity within major large networks and mixed connectivity between networks, and a hypo-connectivity subtype displaying the opposite pattern [4]. These subtypes demonstrated distinct neuro-behavioral correlations, suggesting they may require different intervention approaches despite similar clinical presentations [4].

Genetic Subtypes and Developmental Trajectories

Recent genetic studies have provided crucial insights into the biological underpinnings of ASD heterogeneity. Analysis of polygenic architectures revealed that autism's genetic architecture can be decomposed into two modestly genetically correlated (rg = 0.38) polygenic factors [8]. One factor is associated with earlier autism diagnosis and lower social and communication abilities in early childhood, with only moderate genetic correlations with ADHD and mental-health conditions. The second factor is associated with later autism diagnosis and increased socioemotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence, with moderate to high positive genetic correlations with ADHD and mental-health conditions [8].

Longitudinal data from birth cohorts demonstrate that these genetic profiles align with different developmental trajectories. The "early childhood emergent latent trajectory" is characterized by difficulties in early childhood that remain stable or modestly attenuate in adolescence, while the "late childhood emergent latent trajectory" shows fewer difficulties in early childhood that increase in late childhood and adolescence [8]. Autistic individuals in the early childhood emergent trajectory are more likely to be diagnosed in childhood than those in the late childhood emergent trajectory [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Multimodal Neuroimaging Subtyping Protocol

The following experimental workflow outlines the comprehensive approach used in recent studies integrating structural and functional neuroimaging data for ASD subtyping:

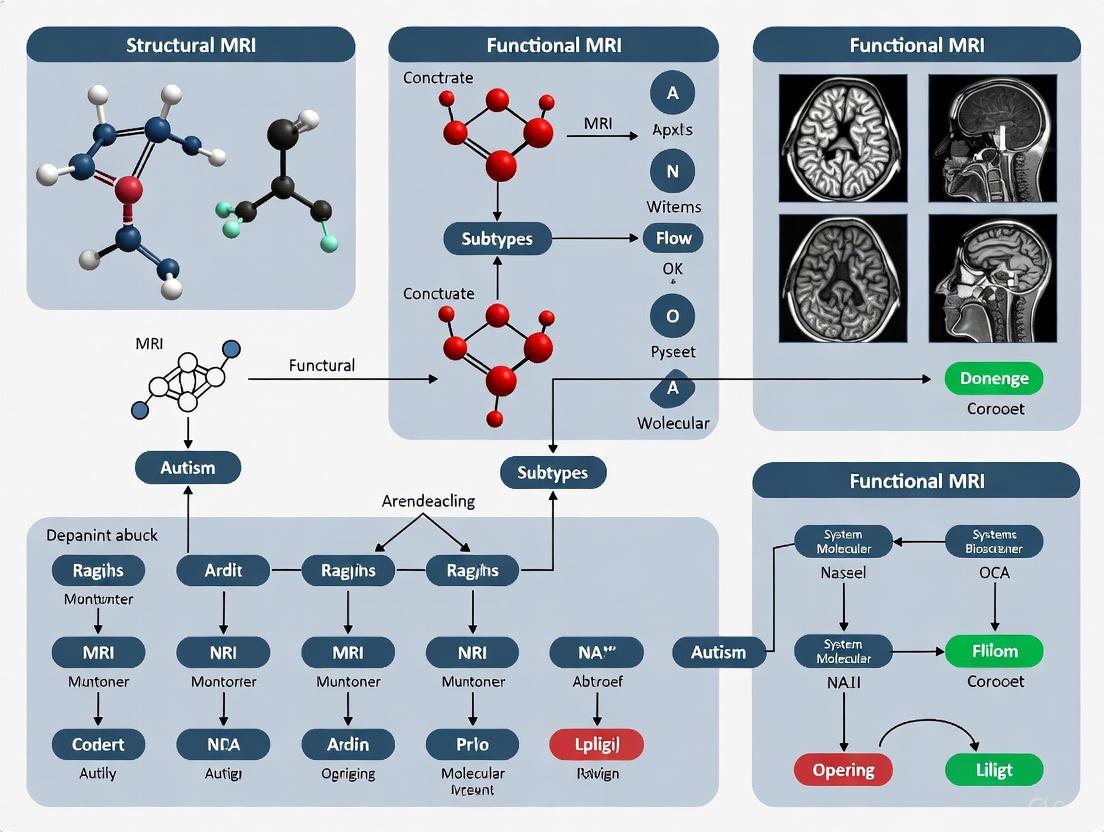

Diagram 1: Multimodal neuroimaging subtyping protocol. This workflow illustrates the comprehensive pipeline for identifying ASD subtypes through integrated analysis of structural and functional neuroimaging data, from initial data collection through final validation [2] [6] [4].

Genetic Analysis Protocol

Genetic studies of ASD subtypes employ sophisticated polygenic analysis methods to identify distinct genetic architectures underlying different phenotypic presentations:

Diagram 2: Genetic analysis protocol for ASD subtypes. This workflow outlines the process for identifying genetically distinct ASD subtypes through integrated analysis of deep phenotypic data and genetic information from large cohorts [7] [8] [9].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ASD Subtyping Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Measures | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Databases | ABIDE I & II [6] [4] | Large-scale, multi-site neuroimaging data | Standardized preprocessing, phenotypic data, >2000 participants |

| Genetic Cohorts | SPARK [7] [9] | Genetic analysis of ASD subtypes | 50,000+ families, deep phenotyping, genomic data |

| Clinical Assessments | ADOS, ADI-R, SRS [6] | Standardized behavioral assessment | Gold-standard diagnostic measures, quantitative traits |

| Eye-Tracking Paradigms | Face emotion processing, Joint attention tasks [6] | Social attention measurement | Objective behavioral metrics, autism-sensitive tasks |

| Processing Software | fMRIPrep, FreeSurfer [6] [3] | Automated image processing | Standardized pipelines, reproducibility, quality control |

| Analysis Frameworks | HYDRA [4], Normative modeling [6] | Advanced clustering algorithms | Semi-supervised approach, individual deviation quantification |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Growth mixture models [8], Polygenic risk scoring | Genetic architecture decomposition | Latent trajectory identification, genetic correlation analysis |

The decomposition of autism heterogeneity into biologically meaningful subtypes represents a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize, diagnose, and treat this complex condition. The integration of structural and functional neuroimaging with genetic and deep phenotypic data has revealed distinct subtypes with different developmental trajectories, neural circuitry profiles, and genetic architectures. While structural MRI provides valuable information about brain anatomy and has demonstrated respectable classification accuracy in multivariate approaches, functional MRI offers unique insights into brain network dynamics that may more directly relate to clinical symptoms. The most promising approaches, however, combine multiple modalities to capture the complex interplay between brain structure and function.

These advances have important implications for both research and clinical practice. From a research perspective, they provide a framework for deconstructing autism heterogeneity, enabling more homogeneous grouping for mechanistic studies and clinical trials. For clinical practice, they pave the way for precision medicine approaches that move beyond one-size-fits-all interventions toward personalized strategies tailored to an individual's specific neurobiological subtype. As these methods continue to refine and validate ASD subtypes, we anticipate a transformation in how autism is diagnosed and treated, ultimately leading to more effective, individualized interventions that improve quality of life for autistic individuals across the lifespan.

The understanding and classification of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have undergone a profound transformation, shifting from behaviorally defined subgroups to categories grounded in measurable neurobiological variation. Historically, diagnostic manuals categorized autism into distinct behavioral subtypes such as autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) [5]. While clinically useful, these categories often masked underlying biological heterogeneity. The advent of advanced neuroimaging techniques, particularly structural (sMRI) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), has revolutionized this paradigm. This guide objectively compares how sMRI and fMRI approaches are used to identify autism subtypes, detailing their experimental protocols, findings, and applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Structural MRI (sMRI) Approaches to Subtyping

Structural MRI investigates the neuroanatomy of the brain, providing static measures of volume, thickness, and shape of various brain structures. Its application has been pivotal in demonstrating that autism is not a single, monolithic entity but comprises subgroups with distinct neuroanatomical profiles.

Core Experimental Protocols

A common modern protocol for sMRI subtyping involves population modeling and machine learning:

- Data Acquisition and Processing: T1-weighted MRI scans are processed using software like FreeSurfer to extract morphometric features such as cortical thickness, surface area, and grey matter volume from parcellated brain regions (e.g., using the Desikan-Killiany atlas) [10].

- Population Modeling (Normative Modeling): Generalized Additive Models of Location Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) are used to generate population-level "growth charts" for brain features based on thousands of typically developing individuals. Each autistic individual is then assigned a centile score representing their deviation from this normative trajectory, accounting for age and sex [10].

- Clustering Analysis: Semi-supervised machine learning algorithms, such as HYDRA (HeterogeneitY through DiscRiminative Analysis), cluster individuals based on their patterns of neuroanatomical deviation relative to controls. This method is designed to identify subgroups that may exhibit opposite neuroanatomical patterns (e.g., one subgroup with increased volume and another with decreased volume) [10].

Key Subtyping Findings from sMRI

Research using these protocols has successfully parsed heterogeneity, though the number and nature of subgroups can vary based on the methods and features used [10]. A pivotal finding has been the identification of subgroups with opposing neuroanatomical alterations. For instance, some autistic individuals show patterns of increased total brain volume and cortical surface area, while others show decreased values, patterns that would cancel each other out in traditional case-control analyses [10]. These subgroups, however, have not yet shown consistent correlations with distinct clinical profiles, highlighting a challenge in linking sMRI-based subtypes to behavior [10].

Table 1: Key sMRI Studies on Autism Subtyping

| Study Focus | Dataset | Key Method | Identified Subtypes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transdiagnostic Subgrouping [10] | 4,115 participants (1,305 ASD, 987 ADHD, 1,823 controls) | HYDRA clustering on cortical centile scores | Subgroups with opposing neuroanatomical patterns (number varies by method) | Confirms neuroanatomical heterogeneity within ASD/ADHD; subgroups often lack clear clinical differentiation. |

| Traditional Subtype Comparison [5] | 234 participants (152 Autism, 54 Asperger's, 28 PDD-NOS) | Tensor decomposition of fMRI; Gray Matter Volume (GMV) analysis | Autism, Asperger's, PDD-NOS (DSM-IV) | Found significant GMV differences in subcortical and default mode networks between the autism subtype and the other two. |

Functional MRI (fMRI) Approaches to Subtyping

Functional MRI measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow, providing insights into the dynamics of neural circuitry. Subtyping efforts using fMRI focus on how different brain regions communicate, both at rest and during tasks.

Core Experimental Protocols

fMRI subtyping often employs a multi-level analysis of functional connectivity:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) data is preprocessed using standardized pipelines like fMRIPrep, which includes steps for motion correction, normalization to a standard brain template (e.g., MNI152), and band-pass filtering [6].

- Multilevel Functional Connectivity Features:

- Static Functional Connectivity (SFCS): Calculated using Pearson correlation between the average blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals from different brain regions (e.g., the Dosenbach 160 ROIs) to create a correlation matrix representing the strength of connections at rest [6].

- Dynamic Functional Connectivity (DFCS/DFCV): Assessed using Dynamic Conditional Correlation (DCC) to measure the strength and variability of connections between regions over time, capturing the instant dynamics of brain networks [6].

- Normative Modeling and Clustering: Similar to the sMRI approach, normative models of multilevel FC are built from a typically developing (TD) group. Individual deviations from this norm are calculated for the ASD group, which are then used in clustering analyses (e.g., k-means) to identify subtypes [6].

Key Subtyping Findings from fMRI

This approach has successfully identified clinically relevant neural subtypes. A 2025 study of 1,046 participants identified two distinct ASD subtypes with unique functional brain network profiles despite comparable clinical symptom scores [6]. One subtype showed positive deviations (hyperconnectivity) in the occipital and cerebellar networks, coupled with negative deviations (hypoconnectivity) in frontoparietal, default mode, and cingulo-opercular networks. The other subtype exhibited the inverse pattern [6]. Crucially, these neural subtypes were validated with an independent measure, showing different gaze patterns in social eye-tracking tasks, confirming a link between neural subtypes and behavioral function [6].

Table 2: Key fMRI Studies on Autism Subtyping

| Study Focus | Dataset | Key Method | Identified Subtypes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Subtypes [6] | 1,046 participants (479 ASD, 567 TD) | Normative modeling of static/dynamic functional connectivity | 2 neural subtypes with opposite connectivity patterns | Subtypes showed distinct eye-gaze patterns, confirming a neurobehavioral link beyond clinical symptoms. |

| Underconnectivity & Default Mode [11] | Literature Review | Task-based and resting-state fMRI | Not Applicable (Review Article) | Provided early evidence of underconnectivity in distributed cortical networks and abnormalities in the default-mode network in ASD. |

Integrated Analysis: Bridging Genetics, Biology, and Subtypes

Beyond imaging, large-scale datasets are now integrating genotypic and deep phenotypic data to define subtypes holistically. A landmark 2025 study used generative mixture modeling on over 230 traits in 5,392 individuals from the SPARK cohort, identifying four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes [7] [12].

- Social and Behavioral Challenges (37%): Core ASD traits with co-occurring conditions (ADHD, anxiety) but no developmental delays; linked to genetic mutations in genes active after birth [7] [13].

- Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%): Prominent developmental delays but fewer co-occurring psychiatric conditions; linked to rare inherited variants and genes active prenatally [7] [13].

- Moderate Challenges (34%): Milder core ASD traits and fewer co-occurring conditions [12].

- Broadly Affected (10%): Severe, wide-ranging challenges including core symptoms, delays, and psychiatric conditions; showed the highest rate of damaging de novo mutations [7] [13].

This work demonstrates that biologically defined subtypes have distinct genetic underpinnings and developmental trajectories, offering a powerful framework for future research and targeted therapeutic development.

Table 3: Key Resources for Autism Subtyping Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ABIDE I & II [6] | Data Repository | Publicly shared repository of brain imaging and phenotypic data from ASD individuals and controls, enabling large-scale analyses. |

| SPARK Cohort [7] [12] | Research Cohort | Largest US study of autism, providing genetic and deep phenotypic data for identifying biologically distinct subgroups. |

| FreeSurfer [10] | Software Toolbox | Processes structural MRI data to extract morphometric features like cortical thickness and surface area. |

| fMRIPrep [6] | Software Toolbox | Standardizes and automates the preprocessing of fMRI data, ensuring reproducibility and reducing pipeline variability. |

| HYDRA [10] | Algorithm | A semi-supervised clustering algorithm that groups individuals based on their differences from a control sample. |

| Normative Modeling [6] [10] | Statistical Framework | Quantifies individual-level deviation from a normative population benchmark, embracing heterogeneity. |

| Dosenbach 160 ROIs [6] | Brain Atlas | A predefined set of brain regions used to extract signals for functional connectivity analysis. |

Visualizing Research Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental protocols for sMRI and fMRI subtyping, highlighting the logical flow from data acquisition to subtype identification.

Figure 1: fMRI Subtyping Workflow. This diagram outlines the process for identifying autism subtypes using functional MRI data, from acquisition to validation.

Figure 2: sMRI Subtyping Workflow. This diagram illustrates the structural MRI subtyping process, which uses population modeling and machine learning to find subgroups based on anatomical differences.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by substantial neurobiological heterogeneity, driving research efforts to identify meaningful subtypes that can inform diagnosis and treatment. Central to this investigation is the consistent observation of early brain overgrowth followed by atypical developmental trajectories in a significant subset of autistic individuals. This article synthesizes key neuroanatomical findings within the context of structural versus functional MRI research, providing a comparative analysis of methodological approaches and empirical data shaping current understanding. The examination of brain development patterns not only offers insights into potential biological mechanisms but also facilitates the stratification of ASD into more homogeneous subgroups based on neuroanatomical profiles rather than solely behavioral manifestations.

Quantitative Synthesis of Key Neuroanatomical Findings

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Early Brain Overgrowth Findings

| Study Reference | Sample Characteristics | Key Metric | Developmental Pattern | Magnitude of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courchesne (2004) [14] | Retrospective analysis | Brain volume | Early overgrowth followed by premature arrest | Most deviant overgrowth in cerebral, cerebellar, and limbic structures by 2-4 years |

| Nature (2017) [15] | 106 high-risk infants, 42 low-risk | Cortical surface area | Hyperexpansion 6-12 months, precedes volume overgrowth (12-24 months) | Predicted ASD diagnosis with 81% PPV, 88% sensitivity |

| Yale PET Study (2025) [16] | 12 autistic adults, 20 neurotypical | Synaptic density | Reduced synaptic density in adulthood | 17% lower synaptic density across whole brain |

| Feng et al. [17] | 46 FXS, 90 idiopathic ASD, 54 TD | Gray matter volume | Faster GMV growth rates in ASD vs FXS and TD | Distinct spatial patterns: FXS increased subcortical GMV, ASD varied |

Table 2: Neuroanatomical Profiles Across ASD Subtypes and Related Conditions

| Condition/Subtype | Structural Findings | Functional Connectivity Patterns | Developmental Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASD Functional Subtype 1 [6] | N/A | Positive deviations: occipital and cerebellar networks; Negative deviations: frontoparietal, DMN, cingulo-opercular networks | Associated with distinct gaze patterns in social cue tasks |

| ASD Functional Subtype 2 [6] | N/A | Inverse pattern of Subtype 1 | Different functional developmental pattern despite similar clinical presentation |

| Fragile X Syndrome [17] | Increased GMV in caudate, Crus I cerebellum; Decreased GMV in frontal insular regions, cerebellar vermis | N/A | Divergent trajectory from idiopathic ASD, despite behavioral overlap |

| High-Functioning Autism [18] | N/A | Generalized visuoperceptual processing deficit | Atypical configural processing across development |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Approaches

Prospective Infant Neuroimaging

The landmark 2017 Nature study established a protocol for identifying early biomarkers in infants at high familial risk for ASD [15]. This longitudinal approach involved:

- Participant Recruitment: 106 infants at high familial risk and 42 low-risk infants

- Imaging Timepoints: 6, 12, and 24 months of age

- Key Analytical Method: Deep learning algorithm applied to cortical surface area measurements from 6-12 months to predict ASD diagnosis at 24 months

- Primary Findings: Cortical surface area hyperexpansion between 6-12 months preceded brain volume overgrowth observed between 12-24 months

- Validation: Algorithm achieved positive predictive value of 81% and sensitivity of 88% in individual predictions

This protocol demonstrated that early brain changes occur during the emergence of autistic behaviors, providing a potential window for very early intervention.

Functional Subtyping in Heterogeneous ASD

The 2025 Molecular Psychiatry study addressed ASD heterogeneity through functional subtyping [6]:

- Sample: 1,046 participants (479 ASD, 567 typical development) from ABIDE I and II datasets

- Analytical Framework: Normative modeling of multilevel functional connectivity features

- Connectivity Measures: Static functional connectivity strength (SFCS), dynamic functional connectivity strength (DFCS), and dynamic functional connectivity variance (DFCV)

- Validation Cohort: Independent cohort of 21 ASD individuals with resting-state fMRI and eye-tracking data

- Clustering Approach: Identification of subtypes based on deviations from normative functional connectivity trajectories

This approach revealed two distinct neural subtypes with unique functional network profiles despite comparable clinical presentations, underscoring the value of data-driven subtyping approaches.

Synaptic Density Measurement in Living Brains

The Yale study pioneered direct measurement of synaptic density in living autistic individuals [16]:

- Participants: 12 autistic adults and 20 neurotypical controls

- Imaging Technique: PET scanning with novel radiotracer 11C-UCB-J

- Complementary Imaging: MRI for anatomical reference

- Clinical Correlation: ADOS assessment and self-report measures of autistic features

- Key Finding: 17% lower synaptic density across whole brain correlated with social-communication differences

This protocol provided the first direct evidence of reduced synaptic density in living autistic people, with potential implications for understanding connectivity abnormalities.

Diagram 1: Developmental Trajectory of Brain Changes in Autism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Critical Research Resources for Autism Neurodevelopment Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Databases | ABIDE I & II [19] [6] | Large-scale, multi-site datasets for normative modeling and subtyping |

| Radiotracers | 11C-UCB-J [16] | In vivo synaptic density measurement via PET imaging |

| Eye-Tracking Paradigms | Face emotion processing, Joint attention tasks [6] | Quantifying social attention patterns linked to neural subtypes |

| Analytical Pipelines | Normative modeling [6], Tensor decomposition [19], Deep learning algorithms [15] | Identifying deviations from typical development and predictive patterns |

| Behavioral Assessment Tools | ADOS, ADI-R, SRS [6] [18] | Standardized clinical phenotyping and correlation with neural measures |

Structural versus Functional Subtyping: Convergent and Divergent Patterns

The distinction between structural and functional approaches to ASD subtyping reveals complementary insights into neurobiological mechanisms. Structural approaches have identified early overgrowth trajectories [14] [15] and volumetric differences across subtypes [17], while functional approaches have revealed distinct connectivity profiles that cross-cut traditional diagnostic boundaries [6].

Diagram 2: Structural versus Functional Subtyping Approaches in Autism Research

Implications for Targeted Interventions

The identification of neuroanatomical and functional subtypes holds significant promise for developing targeted interventions. The finding that cortical overgrowth begins between 6-12 months [15] suggests a critical window for early intervention. Similarly, the discovery of reduced synaptic density in autistic adults [16] points to potential targets for pharmacological interventions. Furthermore, the correlation between functional connectivity subtypes and differential response to oxytocin treatment [6] underscores the clinical utility of neurobiological stratification.

The integration of structural and functional neuroimaging has substantially advanced our understanding of atypical development in autism. The consistent observation of early brain overgrowth in a subset of autistic children, followed by divergent developmental trajectories, provides a neurobiological framework for parsing heterogeneity. Contemporary research approaches that leverage large-scale datasets, normative modeling, and multimodal imaging are increasingly capable of identifying biologically meaningful subtypes that transcend behavioral phenomenology. These advances promise more personalized approaches to intervention aligned with an individual's specific neurodevelopmental profile, ultimately improving outcomes across the autism spectrum.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social communication, interaction, and the presence of restricted, repetitive behaviors. The quest to identify its neurobiological underpinnings has increasingly focused on the concept of large-scale brain network dysconnectivity. Among the most studied networks are the default mode network (DMN), crucial for self-referential thought and social cognition, and the salience network (SN), responsible for detecting and orienting attention toward relevant stimuli. This guide objectively compares the roles of these two networks in ASD, synthesizing current experimental data to provide a clear resource for researchers and drug development professionals working within the context of structural versus functional MRI research on autism subtypes.

Converging evidence from multimodal neuroimaging indicates that altered functional and structural organization of both the DMN and SN are prominent neurobiological features of ASD [20]. The DMN, comprising key nodes such as the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and temporoparietal junction (TPJ), is fundamentally involved in processes like theory of mind and self-referential thinking—functions known to be impaired in ASD [20]. Conversely, the SN, anchored in the anterior insula (AI) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), acts as a switch between the DMN and task-positive networks like the central executive network, guiding attention to the most salient internal and external events [21] [22]. Dysfunction in this switching mechanism is theorized to underlie the atypical sensory processing and social attention observed in ASD.

Default Mode Network (DMN) in ASD

Functional Neuroanatomy and Social Cognition

The DMN is a strongly interconnected system that is most active during rest and engages during social cognitive processes. Its core nodes support distinct aspects of social cognition:

- Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC): Acts as a central functional hub with a high baseline metabolic rate. It is implicated in autobiographical memory, imagining one's future, and evaluating the mental states of others [20].

- Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC): This region is involved in monitoring both one's own mental states and the mental states of others. The ventral mPFC is more associated with self-referential processing, while the dorsal mPFC is engaged during mentalizing about others [20].

- Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ): Preferentially encodes 'other-relevant' information, including the beliefs and intentions of others. It is critical for distinguishing self-relevant from other-relevant information and predicting others' behavior during social interaction [20].

Evidence of DMN Dysconnectivity in ASD

Research across multiple modalities consistently reveals DMN alterations in ASD, which are linked to core social cognitive deficits.

Table 1: Task-Based fMRI Findings of DMN Dysfunction in ASD

| Social Cognitive Domain | Task Examples | Key DMN Findings in ASD | Associated Brain Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Referential Processing | Judgments about self vs. other | Reduced activation; Atypical self-representation; Reduced functional connectivity | Ventral mPFC, PCC [20] |

| Theory of Mind/Mentalizing | Viewing images or stories to infer mental states | Decreased recruitment; Hypoactivation; Mixed findings in developmental studies | Dorsal mPFC, TPJ, PCC [20] |

Table 2: Intrinsic Functional Connectivity and Structural Findings of the DMN in ASD

| Modality | Experimental Measure | Key Findings in ASD | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-State fMRI | Functional Integration & Segregation | Reduced long-range within-network connectivity; Increased between-network connectivity [23] | Functional underconnectivity within the DMN and reduced network segregation |

| Graph Theory Analysis | Modularity, Local Efficiency | Reduced modularity and local efficiency (clustering) [23] | Less optimized, less segregated functional network organization |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging | White Matter Integrity | Lower white matter integrity despite higher numbers of streamlines [23] | Structural underconnectivity supporting functional findings |

A recent meta-analysis of adults with ASD found consistent hypo-activation in the left amygdala, a region with strong functional connections to DMN nodes. This cluster was found to co-activate with the cerebellum and fusiform gyrus, regions implicated in social cognition, suggesting a broader disrupted network [24]. Furthermore, studies investigating ASD subtypes have found that impairments within the DMN are a major factor that differentiates the autism subtype from Asperger's and PDD-NOS [5].

Salience Network (SN) in ASD

Functional Neuroanatomy and Its Role in Attention

The SN is an early-emerging network critical for identifying the most subjectively relevant stimuli from among multiple internal and external inputs. Its core function is to guide behavior by dynamically switching attention between the internally-focused DMN and the externally-focused, goal-oriented central executive network (CEN) [21] [25]. The key nodes of the SN include:

- Anterior Insula (AI): Considered the hub of the SN, it is involved in interoceptive awareness and perception of emotionally salient information.

- Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): Works with the AI to integrate sensory, emotional, and cognitive information to guide attentional resources.

In typical development, robust SN connectivity with prefrontal regions supports attention to socially relevant information, such as faces [22].

Evidence of SN Dysconnectivity in ASD

Altered SN connectivity, particularly hyperconnectivity with primary sensory regions, is a robust finding in ASD and is strongly linked to sensory symptoms.

Table 3: Key Findings on Salience Network Dysconnectivity in ASD

| Study Demographic | Experimental Method | Key SN Findings in ASD | Correlation with Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children & Adolescents | Resting-state fMRI | SN hyperconnectivity with sensorimotor and attention regions [21] | Associated with sensory over-responsivity (SOR) symptoms |

| 6-Week-Old Infants (High-Likelihood for ASD) | Resting-state fMRI | Stronger SN connectivity with sensorimotor regions; Weaker SN connectivity with prefrontal regions [22] | Predicted subsequent sensory hypersensitivity and attenuated social attention |

| Adolescents | Resting-state fMRI (ICA) | Atypical within-network and between-network connectivity as part of a triple-network model [25] | Associated with core social impairments |

The hyperconnectivity between the SN and sensorimotor/limbic regions (e.g., amygdala) creates a neural substrate where basic sensory information is assigned excessive salience, leading to sensory over-responsivity (SOR) [21]. This is further supported by findings that this hyperconnectivity is directly correlated with the extent of brain activation in response to mildly aversive auditory and tactile stimuli [21]. A trade-off has been observed in infancy, whereby stronger SN-sensorimotor connectivity is inversely correlated with weaker SN-prefrontal connectivity, providing a mechanistic account for the co-emergence of sensory and social symptoms in ASD [22].

Direct Comparison of DMN and SN Alterations

The DMN and SN exhibit distinct, yet potentially interrelated, patterns of dysconnectivity in ASD. The table below provides a structured, direct comparison based on the synthesized research findings.

Table 4: Comparative Overview of DMN and SN Dysconnectivity in ASD

| Aspect | Default Mode Network (DMN) | Salience Network (SN) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functional Role | Self-referential thought, mentalizing, autobiographical memory [20] | Detecting salient stimuli, switching between internal (DMN) and external (CEN) attention [21] [25] |

| Key Altered Nodes | Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC), Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC), Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ) [20] | Anterior Insula (AI), Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) [21] |

| Predominant Connectivity Pattern in ASD | Functional Underconnectivity within the network and with other social brain regions [20] [23] | Hyperconnectivity with sensorimotor and limbic regions (e.g., amygdala) [21] [22] |

| Associated Clinical Symptoms | Deficits in theory of mind, self-other processing, social communication [20] [26] | Sensory over-responsivity, atypical social attention, anxiety, restrictive/repetitive behaviors [21] [22] |

| Developmental Trajectory | Atypical developmental trajectory; mixed patterns of hypo-/hyper-connectivity in children vs. adolescents [20] | Alterations present as early as 6 weeks of age in high-likelihood infants; predicts later symptoms [22] |

| Relationship with Other Networks | Reduced segregation from other functional systems [23] | Failed deactivation of the DMN during tasks due to impaired SN switching [25] |

The Triple-Network Model and Inter-Network Dynamics

The DMN and SN do not operate in isolation. They are core components of the triple-network model, which also includes the central executive network (CEN) [25]. In this model, the SN is hypothesized to regulate the dynamic interplay between the DMN and CEN. Dysfunction of the SN in ASD can therefore lead to a failure to suppress the DMN during externally demanding tasks, and/or a failure to engage the CEN appropriately. This provides a parsimonious framework for understanding how distinct alterations in both the DMN (social cognition) and SN (sensory salience) might arise from a common source of dysregulation in network switching [25].

The following diagram illustrates the typical and hypothesized ASD-specific interactions within this triple-network model:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section details the standard experimental protocols used to generate the key findings cited in this guide, providing a reference for researchers seeking to replicate or build upon this work.

Resting-State Functional MRI (rs-fMRI) Protocol

Resting-state fMRI is the primary method for investigating intrinsic functional connectivity within and between large-scale networks like the DMN and SN.

Table 5: Standard rs-fMRI Acquisition and Analysis Protocol

| Protocol Phase | Key Parameters & Procedures | Considerations for ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition | • Scanner: 3T MRI scanner• Sequence: Gradient-echo EPI• Parameters: TR/TE = 2000/30 ms, voxel size = 3-4 mm³• Duration: 5-10 minutes of rest (eyes open/closed) [23] [21] | • Participant comfort and acclimatization are critical.• Use of mock scanners.• For infants, data is acquired during natural sleep [22]. |

| Preprocessing | • Software: DPARSF, FSL, SPM• Steps: Discard initial volumes, slice-time correction, realignment, normalization to MNI space, spatial smoothing (FWHM 5-8 mm) [27] [25] | • Rigorous motion correction is essential (e.g., scrubbing, regression).• Global signal regression is debated but often used. |

| Functional Connectivity Analysis | • Seed-Based Correlation: Placing a seed region (e.g., rAI for SN, PCC for DMN) and correlating its time-course with all other brain voxels [21] [22].• Independent Component Analysis (ICA): Data-driven approach to identify networks without a priori seeds [25].• Graph Theory: Models the brain as a network of nodes and edges to compute metrics like efficiency and modularity [23]. | • Seed selection must be justified.• ICA requires estimation of component numbers.• Graph theory necessitates defining network nodes (e.g., using a brain atlas). |

Task-Based fMRI Protocol for Social Cognition

Task-based fMRI is used to probe network function during specific cognitive processes.

Table 6: Key Elements of Social Cognitive Task-fMRI Protocols

| Component | Description | Examples for DMN/SN Engagement |

|---|---|---|

| Task Paradigm | Block or event-related design presenting stimuli. | • Theory of Mind: Animations or stories requiring mental state inference [20].• Self-Referential Processing: Judging whether adjectives describe oneself or a familiar other [20].• Sensory Processing: Exposure to mildly aversive tactile or auditory stimuli to probe SN [21]. |

| Analysis | General Linear Model (GLM) to identify brain regions with BOLD signal changes correlated with task conditions. | Contrasts are created (e.g., "Self" > "Other" or "Social" > "Non-social") to identify regions differentially active in ASD vs. control groups [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers investigating DMN and SN connectivity in ASD, the following table details key resources and analytical tools.

Table 7: Essential Reagents and Resources for Network Dysconnectivity Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ABIDE Database | Publicly shared repository of preprocessed neuroimaging data from ASD individuals and controls. | Primary data source for large-scale analyses; includes anatomical and resting-state fMRI data [5] [28]. |

| Preprocessing Pipelines | Software for standardizing the initial steps of MRI data analysis. | • DPARSF: Integrated pipeline for rs-fMRI data preprocessing [25].• CCS (Connectome Computation System): Provides a standardized preprocessing protocol for ABIDE data [5]. |

| Analysis Toolboxes | Specialized software for functional connectivity and network analysis. | • GIFT: Toolbox for performing Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [25].• FNC & BrainGraph: Tools for functional network connectivity and graph theory analysis [23] [25]. |

| Statistical & Meta-Analytic Tools | For synthesizing findings across studies and performing robust statistical inference. | • ES-SDM: Software for voxel-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies [27].• GingerALE: Tool for Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) meta-analysis [24]. |

| Contrast Subgraph Algorithms | Advanced network comparison technique to identify maximally different connectivity patterns between groups. | Used to identify mesoscopic-scale structures that are hyper- or hypo-connected in ASD vs. controls, reconciling conflicting connectivity reports [28]. |

The quest to identify robust neurobiological subtypes of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has been significantly hampered by the condition's profound heterogeneity. For decades, neuroimaging research has vacillated between structural (sMRI) and functional (fMRI) magnetic resonance imaging approaches, often with conflicting results. This guide objectively compares the performance of these unimodal methodologies against emerging multimodal fusion techniques, which integrate sMRI and fMRI data to capture complementary aspects of brain organization. By synthesizing experimental data from recent studies, we demonstrate that multimodal integration consistently outperforms single-modality analyses in classifying ASD subtypes, predicting symptom severity, and identifying biologically coherent subgroups. The comparative data presented herein provide researchers and drug development professionals with a evidence-based framework for selecting neuroimaging approaches that maximize sensitivity to the complex, system-level brain alterations characteristic of ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) encompasses a range of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by deficits in social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors [29]. Its remarkable heterogeneity across biological etiologies, neural systems, and clinical presentations presents a substantial challenge for diagnosis and precision treatment [29] [30]. Historically, neuroimaging studies have attempted to parse this heterogeneity using either structural or functional modalities in isolation, yielding inconsistent and often non-reproducible findings [31].

The theoretical rationale for multimodal integration stems from the understanding that pathophysiological processes in ASD manifest across multiple aspects of neurobiology [32]. Structural modalities (e.g., sMRI, DTI) reveal static anatomical properties like gray matter volume (GMV) and white matter integrity, while functional modalities (e.g., resting-state fMRI) capture dynamic patterns of neural activity and connectivity [33] [31]. Neither perspective alone sufficiently characterizes the complex brain-behavior relationships in ASD, necessitating combined approaches that leverage their complementary strengths [32].

Comparative Performance: Unimodal vs. Multimodal Approaches

Diagnostic Classification Accuracy

Table 1: Classification Performance of Neuroimaging Modalities in ASD

| Modality Approach | Features Used | Sample Size (ASD/Controls) | Classification Accuracy | Study/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal (sMRI + rs-fMRI) | ALFF + sMRI maps | 702 (351/351) | 76.9% ± 2.34 | 3D-DenseNet (Two-channel) [34] |

| Functional (rs-fMRI) | ALFF maps only | 702 (351/351) | 72.0% ± 3.1 | 3D-DenseNet (One-channel) [34] |

| Multimodal (rs-fMRI + sMRI) | Functional connectivity + Gray matter | Not specified | 65.6% | Traditional ML Fusion [34] |

| Structural (sMRI) | Gray matter only | Not specified | 63.9% | Traditional ML [34] |

| Functional (rs-fMRI) | Functional connectivity only | Not specified | 60.6% | Traditional ML [34] |

| Structural (sMRI) | White matter only | Not specified | 59.7% | Traditional ML [34] |

Deep learning models leveraging combined ALFF-sMRI inputs achieve superior classification accuracy compared to unimodal approaches, demonstrating the value of integrating functional and structural information [34]. The two-channel model's performance highlights how structural and functional data provide non-redundant information that collectively enhances ASD identification.

Subtype Identification and Behavioral Correlation

Table 2: Subtype Identification Across Methodological Approaches

| Imaging Approach | Subtypes Identified | Key Neural Correlates | Behavioral Correlations | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Fusion (SNF) | 2 male ASD subtypes | Opposite GMV changes; distinct ALFF patterns | ALFF alterations predicted social communication severity in Subtype 1 | Gao et al. 2025 [35] |

| DSM-IV Subtype Comparison | Asperger's, PDD-NOS, Autistic | Common: DLPFC, temporal cortex; Unique: subcortical fALFF patterns | Each pattern correlated with different ADOS subdomains | [29] |

| rTMS Intervention | Pre-post changes | Increased GMV: Cerebellar Vermis, Caudate; Enhanced FC: Frontal-Temporal | Neuroimaging changes correlated with behavioral improvements | [36] |

Multimodal approaches successfully parse heterogeneity by revealing distinct neurobiological subtypes with differential clinical profiles. Unlike unimodal classifications, multimodal fusion can identify subgroups with opposite structural patterns (e.g., increased vs. decreased GMV) coupled with unique functional alterations that directly predict specific symptom domains [35] [29].

Experimental Protocols in Multimodal Research

Multimodal Fusion Using Similarity Network Fusion (SNF)

Protocol Overview: This unsupervised learning method identifies data-driven subtypes by fusing structural and functional distance networks [35].

- Sample Characteristics: 207 male children (105 ASD, 102 healthy controls) from ABIDE database

- Feature Extraction:

- Structural: Gray matter volume (GMV) from sMRI

- Functional: Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) from resting-state fMRI

- Fusion Process: Structural and functional distance networks are constructed separately then integrated using SNF algorithm

- Clustering: Spectral clustering applied to the fused network to identify subtypes

- Validation: Multivariate support vector regression analyzes relationship between multimodal alterations and symptom severity

Linked Independent Component Analysis (LICA)

Protocol Overview: This data-driven technique decomposes multimodal data to identify coherent patterns of variation across modalities [32].

- Sample Characteristics: 206 autistic and 196 non-autistic participants from EU-AIMS LEAP project

- Feature Extraction:

- Structural: Grey matter density maps from T1-weighted MRI; probabilistic tractography from DWI

- Functional: Connectopic maps from resting-state fMRI

- Integration: LICA decomposes multimodal data into independent components representing shared variance across modalities

- Analysis: Linear mixed-effects models evaluate component relationships with diagnosis and behavioral measures

Deep Learning with Twinned Neuroimaging Inputs

Protocol Overview: Two-channel 3D-DenseNet architecture processes structural and functional inputs simultaneously [34].

- Sample Characteristics: 702 participants (351 ASD, 351 controls) from ABIDE I

- Input Preparation:

- Channel 1: sMRI maps (T1-weighted, downsampled to 3mm isotropic)

- Channel 2: ALFF/fALFF maps from resting-state fMRI

- Preprocessing: Minimal preprocessing with intentional data diversity retention

- Data Augmentation: Random rotation (±30° z-axis) and zoom (0.7-1.3×) during training

- Architecture: Two-channel 3D-DenseNet with adaptive average pooling to handle varying matrix sizes

Multimodal Integration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Analytical Tools for Multimodal ASD Research

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE Database | Data Resource | Preprocessed neuroimaging data from multiple sites | Provides standardized datasets for method development [35] [29] |

| 11C-UCB-J Radiotracer | PET Tracer | Quantifies synaptic density in living humans | First direct measurement of reduced synapses in ASD [16] |

| Yiruide YRDCCY-1 rTMS | Intervention Device | Non-invasive neuromodulation | Investigates causal structure-function relationships [36] |

| Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) | Algorithm | Unsupervised multimodal fusion | Identifies data-driven ASD subtypes [35] |

| Linked ICA (LICA) | Algorithm | Multimodal data decomposition | Identifies cross-modal biomarkers [32] |

| 3D-DenseNet | Deep Learning Architecture | Classification from neuroimaging inputs | Twinned networks for sMRI-fMRI integration [34] |

The cumulative evidence from comparative studies strongly supports multimodal integration as a superior approach for delineating the neurobiological architecture of ASD. By simultaneously capturing structural and functional aspects of brain organization, multimodal protocols achieve enhanced classification accuracy, reveal clinically meaningful subtypes, and identify robust brain-behavior relationships that elude unimodal methods.

For drug development professionals, these advances offer promising pathways toward target validation and patient stratification. The identification of biologically coherent subgroups through multimodal imaging may enable more targeted clinical trials and personalized intervention approaches [30] [37]. Furthermore, the demonstration that intervention-induced structural changes correlate with functional and behavioral improvements provides a crucial framework for evaluating treatment efficacy [36].

As the field progresses, future research should prioritize the standardization of multimodal protocols, development of normative references, and integration of genetic and molecular data with neuroimaging phenotypes. Such efforts will ultimately realize the promise of precision medicine for individuals with ASD, moving beyond behavioral symptomatology to target underlying neurobiological mechanisms.

Multimodal Neuroimaging in Action: Techniques for Identifying ASD Subtypes

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication and repetitive behaviors, affecting approximately 1% of the population worldwide [38]. The profound heterogeneity in its presentation has posed significant challenges for identifying consistent neural biomarkers, with studies often reporting contradictory findings regarding brain structure and function [39]. This variability stems from multiple factors, including biological heterogeneity, differences in imaging protocols, and small sample sizes typical of single-site studies [38]. To address these challenges, the field has increasingly turned to large-scale, multi-site datasets that provide the statistical power needed to detect robust signals amidst noise and variability. Two pivotal resources have emerged in this landscape: the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I and II) and the SPARK (SParsity-based Analysis of Reliable k-hubness) analytical framework. ABIDE provides the foundational data infrastructure by aggregating neuroimaging data across international sites, while SPARK offers a novel methodological approach for extracting meaningful patterns from this complex data. Together, these resources represent complementary forces advancing the search for reliable neurosubtypes in ASD, potentially differentiating between structural and functional manifestations of the condition.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Autism Neuroimaging Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Data Modalities | Sample Size | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE I | Data Repository | rs-fMRI, sMRI | 1,112 participants (17 sites) | First large-scale autism neuroimaging data sharing initiative |

| ABIDE II | Data Repository | rs-fMRI, sMRI | Over 1,000 participants (19 sites) | Extension with more detailed phenotypic data |

| SPARK | Analytical Method | rs-fMRI | Variable application across datasets | Identifies connector hubs and overlapping networks |

Dataset Deep Dive: ABIDE I and II

Architecture and Composition

The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) represents a landmark achievement in open neuroscience, created through the aggregation of datasets independently collected across more than 24 international brain imaging laboratories [40]. The initiative was founded to accelerate the understanding of neural bases of autism by providing large-scale samples essential for revealing brain mechanisms underlying ASD heterogeneity [40]. ABIDE I, the initial collection, included functional and structural brain imaging data from 1,112 participants across 17 international sites, comprising 539 individuals with ASD and 573 age-matched typical controls [41]. ABIDE II expanded this resource further with additional datasets and more detailed phenotypic information. This unprecedented data-sharing initiative has consistently adhered to open science principles, making data freely available to researchers worldwide and fundamentally transforming the scale at which autism neuroimaging research can be conducted.

Impact on Research Practices

The availability of ABIDE data has democratized autism neuroimaging research, enabling investigations into brain connectivity patterns across larger and more demographically heterogeneous samples that better reflect clinical reality [41]. Prior to ABIDE, most classification studies achieved high accuracy (often above 90%) but were constrained to dozens of participants from single sites [41]. The scale of ABIDE has revealed a crucial inverse relationship between sample size and classification accuracy—studies using the full dataset typically achieve more modest accuracy (60-70%) but likely produce more generalizable and robust findings [38] [39]. This resource has facilitated the application of diverse machine learning approaches, from support vector machines to deep learning networks, while highlighting the critical importance of standardized evaluation frameworks and the challenges of multi-site data harmonization.

Analytical Innovation: The SPARK Framework

Methodological Foundations

SPARK (SParsity-based Analysis of Reliable k-hubness) represents a significant methodological advancement specifically designed to identify connector hubs and overlapping network structures from resting-state fMRI data [42]. Traditional approaches to hub identification in functional connectivity often rely on thresholded correlation matrices, which are particularly vulnerable to the multicollinearity between temporal dynamics within functional networks [42]. SPARK addresses this fundamental limitation through a unified framework that combines a data-driven sparse General Linear Model (GLM) with bootstrap resampling strategies. The method's novelty lies in its ability to not only count the number of networks involved in each voxel but also identify which specific networks are actually involved, providing a more nuanced view of functional brain organization in autism.

Technical Implementation and Advantages

The SPARK framework introduces the concept of "k-hubness," which denotes the number of networks overlapping in each voxel [42]. This approach bypasses multicollinearity issues by avoiding dependence on simple connection counting from thresholded matrices. The integration of bootstrap resampling provides statistical assessment of reproducibility at the single-subject level, addressing the critical need for reliability in neuroimaging biomarkers [42]. Validation studies using both dimensional box simulations and realistic simulations with artificial hubs generated on real data have demonstrated SPARK's accuracy and robustness [42]. Furthermore, test-retest reliability assessments using the 1000 Functional Connectome Project database, which includes data from 25 healthy subjects at three different occasions, have shown that SPARK provides accurate and reliable estimation of k-hubness, suggesting its utility for understanding hub organization in resting-state fMRI studies of autism [42].

Comparative Performance: Experimental Data and Protocols

Machine Learning Classification Performance

The availability of ABIDE data has enabled systematic comparisons of different machine learning approaches applied to autism classification. Under standardized evaluation frameworks, multiple models demonstrate remarkably similar performance, suggesting that variations in reported accuracy across literature may stem more from differences in inclusion criteria, data modalities, and evaluation pipelines rather than fundamental algorithmic advantages [38] [39].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models on ABIDE Data

| Model | Accuracy | AUC | Modality | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 70.1% | 0.77 | fMRI | Classic approach, strong performance |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | 72.2% | 0.78 | fMRI + sMRI | Ensemble method, highest accuracy |

| Autoencoder + Fully Connected Network | 70.0% | - | fMRI | Feature learning + classification |

| Edge-Variational GCN (EV-GCN) | 81.0%* | - | fMRI | *Reported in literature with different framework |

| Deep Learning Model (University of Plymouth) | 98.0% | - | fMRI | Explainable AI, probability scores |

Recent research leveraging ABIDE data has pushed accuracy boundaries while emphasizing explainability. A deep learning model developed by the University of Plymouth achieved 98% cross-validated accuracy for ASD classification using resting-state fMRI data, coupled with explainable AI techniques that produce maps of brain regions most influential to its decisions [43]. This approach not only provides classification but also model-estimated probability scores and interpretable visualizations, potentially offering clinicians both accurate results and clear, explainable insights to inform assessment decisions [43].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized experimental protocols have emerged as critical factors for robust classification performance. The most reliable frameworks typically involve nested cross-validation, where models are fitted to training sets, parameters tuned on validation sets, and performance evaluated on completely held-out test sets [39]. This process is performed multiple times with rotating test sets to ensure robust performance independent of specific data partitions. For functional connectivity analysis, common preprocessing pipelines include motion correction, spatial normalization, and band-pass filtering, followed by construction of connectivity matrices using Pearson's correlation between region-wise time series [38]. Structural analyses typically involve cortical thickness measurements, subcortical volumetry, and voxel-based morphometry [39].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Autism Subtype Identification

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Application in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE I/II | Data Repository | Provides standardized neuroimaging data | Large-scale classification studies; method validation |

| SPARK Code | Analytical Tool | Identifies connector hubs and overlapping networks | Functional hub analysis; network connectivity studies |

| SmoothGrad | Interpretation Method | Improves stability of feature identification | Model interpretability; biomarker discovery |

| MSDL Atlas | Parcellation Atlas | Defines regions of interest for connectivity | Functional connectivity matrix construction |

| FreeSurfer | Software Tool | Extracts structural features (cortical thickness, volume) | Structural MRI analysis; volumetric studies |

| Bootstrap Resampling | Statistical Method | Assesses reproducibility of findings | Reliability assessment; validation of results |

Integration with Autism Subtyping Research

Structural vs. Functional Insights

The combined application of ABIDE data and advanced analytical methods like SPARK has accelerated progress in differentiating structural and functional autism subtypes. Structural MRI studies have consistently reported differences in total brain volume, brain asymmetry, cortical thickness, and subcortical volume in participants with autism [39]. Functional investigations, particularly using resting-state fMRI, have revealed widespread reductions in connectivity spanning unimodal, heteromodal, primary somatosensory, and limbic regions, with increased connectivity in some subcortical nodes [39]. More recently, a reproducible pattern of hyperconnectivity in prefrontal and parietal cortices with hypoconnectivity in sensory-motor regions has emerged across cohorts [39]. The anterior-posterior disruption in brain connectivity, particularly the anticorrelation between anterior and posterior areas, has been consistently identified as a key functional signature of ASD [41].

Converging Evidence for Subtypes

Machine learning approaches applied to ABIDE data have begun to identify neurobiological subtypes that may correspond to clinically meaningful subgroups. Structural features from ventricles and temporal cortex regions have demonstrated consistent predictive value for autism identification across multiple models [38]. Functional analyses have highlighted the importance of regions including the Paracingulate Gyrus, Supramarginal Gyrus, and Middle Temporal Gyrus in differentiating ASD from controls [41]. The combination of structural and functional modalities has consistently exhibited higher predictive ability compared to single-modality approaches, with ensemble methods further improving performance [39]. These converging lines of evidence suggest distinct neural subtypes that may eventually inform targeted interventions and personalized treatment approaches.

Diagram 2: Structural and Functional Autism Subtypes Hypothesis

The synergy between large-scale datasets like ABIDE and advanced analytical frameworks like SPARK has fundamentally transformed autism neuroimaging research. ABIDE has provided the essential infrastructure for robust, generalizable findings through its multi-site, large-sample design, while SPARK has addressed specific methodological challenges in identifying reliable functional connectivity patterns. Together, they have enabled significant progress in delineating structural and functional subtypes of autism, moving the field closer to biologically-based diagnostic and stratification approaches. Future research directions include further validation of proposed subtypes in independent cohorts, integration of genetic data to explore biological mechanisms, and translation of these findings into clinical applications that can reduce diagnostic delays and personalize interventions. As these resources continue to evolve and be supplemented with new data types, they hold the promise of unraveling the complexity of autism and improving outcomes for autistic individuals worldwide.