Beyond the Gene List: Validating Centrality Measures for Powerful ASD Gene Discovery

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents immense genetic heterogeneity, challenging the identification of true risk genes.

Beyond the Gene List: Validating Centrality Measures for Powerful ASD Gene Discovery

Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents immense genetic heterogeneity, challenging the identification of true risk genes. This article explores the critical role of network centrality measures in cutting-edge ASD gene discovery pipelines. We first establish the foundational principles of network biology in genomics, then detail methodological applications in machine learning models like forecASD and Stacking-SMOTE. The content addresses key challenges including data imbalance and ancestral diversity bias, offering optimization strategies. Finally, we present a rigorous validation framework, comparing centrality-based predictions against biological evidence from recent studies that define ASD subtypes and their distinct genetic profiles. This synthesis provides researchers and drug developers with a validated, computational roadmap to prioritize novel ASD genes and illuminate underlying biological mechanisms for therapeutic intervention.

The Network Blueprint: Foundational Principles of Centrality in ASD Genetics

Core Concepts: Centrality in Biological Networks

Network theory provides a powerful framework for modeling complex biological systems. In this context, molecules like genes or proteins are represented as nodes, and their physical or functional interactions are represented as edges. Centrality measures are quantitative metrics that assign importance to each node based on its position within the network topology. Their application is crucial for prioritizing key elements, such as candidate disease genes in complex disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [1] [2] [3].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why would different centrality measures yield different top gene rankings for my ASD dataset? A: Different centrality measures capture distinct topological properties. A systematic survey of 27 centrality measures in protein-protein interaction networks confirmed that the "best" measure depends heavily on the network's specific topology [2]. For instance, Degree centrality identifies highly connected hubs, while Betweenness centrality highlights nodes that connect otherwise separate parts of the network. It is therefore recommended to use a suite of measures and apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify the most informative ones for your specific biological network [2].

Q: My pathway analysis suggests key genes are "sinks" with no outgoing connections. Why do standard directed centralities rank them as unimportant? A: This is a known limitation of standard directed graph models. In signaling pathways, downstream elements (sinks) are critical receivers of biological signals but may have few or no outgoing edges. The Source/Sink Centrality (SSC) framework addresses this by separately evaluating a node's importance as a sender (Source) and a receiver (Sink) of information, then combining these scores. This method has been shown to more effectively prioritize known cancer and essential genes [3].

Q: How can I validate that my top-ranked centrality genes are biologically relevant to ASD? A: Functional validation is a multi-step process. A common approach is to test for enrichment in known ASD pathways and functions. For example, top genes ranked by game theoretic centrality were enriched for pathways like the immune system, endosomal pathway, and cytokine signaling, all previously implicated in ASD [1]. Furthermore, you can cross-reference your list with high-confidence candidate genes from curated databases like SFARI Gene and check for protein-protein interactions with known ASD genes [1] [4].

Quantitative Comparison of Centrality Measures

The table below summarizes the characteristics of common centrality measures used in biological network analysis, based on a systematic survey in protein-protein interaction networks [2].

Table 1: Key Centrality Measures for Biological Network Analysis

| Centrality Measure | Core Principle | Typical Use Case in Biology | Reported Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Number of direct connections a node has. | Identifying highly connected "hub" proteins; correlates with essentiality [2]. | Simple but effective; performance can be variable across networks [2]. |

| Betweenness | Number of shortest paths that pass through a node. | Finding bottleneck proteins that connect functional modules [2]. | Often outperforms Degree in modular networks [2]. |

| Closeness | Average shortest path distance from a node to all others. | Identifying nodes that can quickly influence the entire network. | High contribution across diverse networks; several variants exist [2]. |

| PageRank | Measures node influence based on the influence of its neighbors. | Ranking genes in pathways; a random walk with restart model [3]. | Standard directed version undervalues sink nodes [3]. |

| Subgraph | Measures node importance based on its participation in all subgraphs. | Identifying structurally central proteins. | Outperformed classic measures in early essentiality studies [2]. |

| Game Theoretic (Shapley Value) | Evaluates a node's marginal contribution to all possible coalitions. | Prioritizing genes based on synergistic influence in a network [1]. | Novel approach that can highlight genes missed by other measures [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Game Theoretic Centrality Analysis for ASD Gene Discovery

This protocol is adapted from studies that used the Shapley value to prioritize disease genes by combining biological networks with coalitional game theory [1].

1. Objective: To rank genes by their synergistic influence in a gene-to-gene interaction network and prioritize candidate genes for ASD.

2. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Game Theoretic Centrality Analysis

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Network | Provides the graph structure for analysis. Represents gene-gene interactions. | STRING database (protein-protein interactions) [1]. |

| Genetic Dataset | The set of genes to be analyzed and ranked. | Whole genome sequence data from multiplex autism families [1]. |

| Gold-Standard ASD Genes | A set of high-confidence genes for validation and model benchmarking. | SFARI Gene database [1]. |

| Pathway Analysis Tool | To biologically validate top-ranking genes by testing for enrichment in known processes. | Reactome Pathway Browser [1]. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Step 1 - Network Construction: Obtain a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network from a database like STRING. This network defines the set of players (genes) for the coalitional game.

- Step 2 - Define the Characteristic Function: For any coalition (subset) of genes

S, the characteristic functionv(S)quantifies the coalition's "worth." This is often defined based on the network's connectivity, for example, the number of nodes outsideSthat are connected to nodes within it. - Step 3 - Calculate Shapley Value: For each gene

i, compute its Shapley value. The Shapley value is the weighted average of the gene's marginal contributionv(S ∪ {i}) - v(S)across all possible coalitionsS. This calculation is computationally intensive and often requires approximation algorithms for large networks. - Step 4 - Rank Genes: Rank all genes in descending order of their Shapley value. Genes with the highest scores are those that, on average, contribute the most to the connectivity of their neighbors.

- Step 5 - Biological Validation:

- Cross-reference: Compare top-ranked genes with known ASD gene sets (e.g., from SFARI Gene).

- Pathway Enrichment: Use a tool like the Reactome Pathway Browser to test if top-ranked genes are significantly enriched for biological pathways previously linked to ASD (e.g., immune system, synaptic signaling) [1].

- Literature Mining: Manually check the association of top novel candidates with ASD or other neurodevelopmental disorders in the literature.

Protocol: Building a Tissue-Specific Network for Omnigenic Analysis

This protocol is based on research that used tissue-specific networks to study the omnigenic model in ASD, which distinguishes core genes from peripheral genes [4].

1. Objective: To construct and analyze a tissue-specific gene interaction network to identify core and peripheral gene clusters relevant to ASD.

2. Research Reagent Solutions

- Tissue-Specific Networks: Genome-scale Integrated Analysis of gene Networks in Tissues (GIANT) database [4].

- Core Gene Set: A curated list of putative core ASD genes (e.g., SFARI Gene database, excluding the lowest confidence scores) [4].

- Clustering Algorithm: Louvain method for community detection [4].

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Step 1 - Network Selection: Download a tissue-specific gene interaction network from the GIANT database. For ASD, the most relevant network is typically derived from brain tissue.

- Step 2 - Extract Core Subgraph: Map your curated set of core ASD genes (e.g., from SFARI) onto the full network. Extract the subgraph that includes only these core genes and the edges between them.

- Step 3 - Calculate Node Strength: For each core gene, calculate its node strength in the full tissue-specific network. Node strength is the sum of the weights of all edges connected to a node, indicating its overall connectedness.

- Step 4 - Cluster Analysis: Apply the Louvain clustering algorithm to the full network to identify communities (clusters) of tightly connected genes.

- Step 5 - Interpret Clusters: Biologically interpret the resulting clusters by performing Gene Ontology enrichment analysis on the genes within each cluster. Clusters in brain tissue are expected to be enriched for functions like synaptic signaling and chromatin remodeling [4].

Visualizations

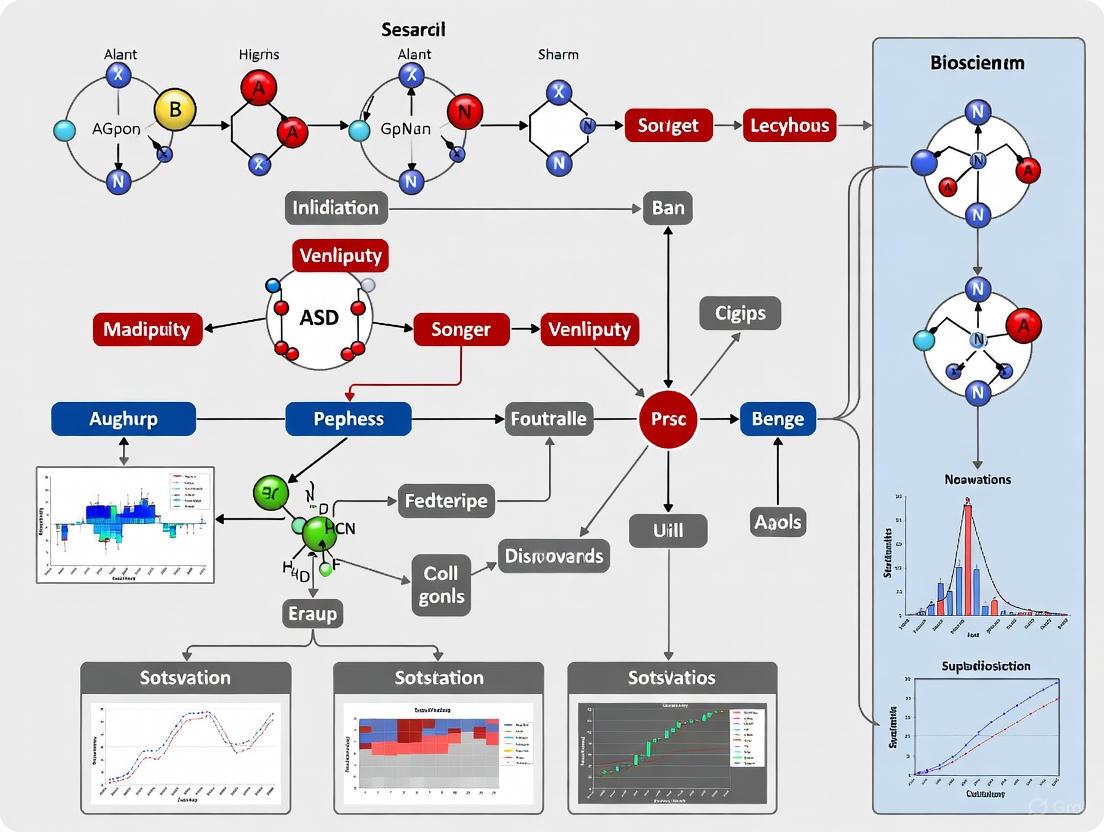

Centrality Analysis Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow for identifying and validating ASD risk genes using network centrality measures, as described in the experimental protocols.

Source/Sink Centrality Framework

This diagram contrasts standard directed centrality with the Source/Sink Centrality (SSC) framework, which is critical for accurately modeling biological pathways.

Omnigenic Model in Tissue Networks

This visualization depicts the core-periphery structure of the omnigenic model within a tissue-specific gene interaction network.

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

FAQ: Why do single-gene approaches have limited success in ASD research? ASD is characterized by extreme genetic heterogeneity, with hundreds of genes implicated and most individual genes accounting for less than 0.5% of cases [5] [6]. The genetic architecture involves both rare variants with strong effects and common variants with weak effects working in combination [7] [6]. Single-gene approaches cannot capture this polygenic complexity or the gene-gene interactions that contribute to ASD pathophysiology.

FAQ: How can researchers account for the clinical heterogeneity in ASD genetic studies? Recent studies have adopted data-driven subtyping approaches that integrate phenotypic and genotypic data. One 2025 study analyzing over 5,000 ASD individuals identified four distinct classes with different biological signatures: Social and Behavioral Challenges (37%), Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%), Moderate Challenges (34%), and Broadly Affected (10%) [8]. These subtypes show minimal overlap in impacted biological pathways, suggesting different underlying mechanisms [8].

FAQ: What biological pathways are consistently implicated across ASD genetic studies? Despite genetic heterogeneity, ASD risk genes converge on several key biological processes as shown in the table below:

Table: Key Biological Pathways Implicated in ASD

| Pathway Category | Specific Pathways | Representative Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Function | Synaptic formation, neurotransmitter signaling, neural connectivity | NLGN3, NLGN4X, NRXN1, SHANK3 [5] [7] |

| Chromatin & Transcription | Chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, epigenetic modification | CHD8, MECP2, ADNP, FMRP [5] [7] |

| Immune System | Immune system, cytokine signaling, HLA complex | HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-G, HLA-DRB1 [1] |

FAQ: How do genetic modifiers influence ASD presentation? Genetic modifiers including copy number variations, single nucleotide polymorphisms, and epigenetic alterations can significantly modulate the phenotypic spectrum of ASD patients with similar pathogenic variants [7]. For example, individuals with similar 15q duplications can present from unaffected to severely disabled [7]. These modifiers likely alter convergent signaling pathways and lead to impaired neural circuitry formation through complex interactions [7].

Experimental Protocols for Advanced ASD Gene Discovery

Hybrid Deep Learning for Key Gene Identification

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Network Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Autism Informatics Portal ASD Gene Set | Provides comprehensive list of ASD-associated genes for network construction | [9] |

| STRING Database | Constructs protein-protein interaction networks restricted to Homo sapiens | [9] |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Extracts node embeddings from PPI networks based on topological features | [9] |

| Centrality Measures (DC, BC, CC, EC) | Quantifies node importance in biological networks for feature matrix | [9] |

Protocol: Hybrid Deep Learning Approach to Identify Key ASD Genes

Sample Preparation & Data Collection:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain the comprehensive list of ASD genes (n=1,215) from the Autism Informatics Portal [9].

- Data Curation: Remove duplicates, isolated, and redundant nodes to yield a final dataset (recommended: 979 genes) [9].

- Network Construction: Use STRING database to construct a protein-protein interaction network restricted to Homo sapiens, typically resulting in ~9,505 interactions among the ASD genes [9].

Feature Processing:

- Network Representation: Create an undirected graph G=(V,E,A) where V represents nodes (genes), E represents edges (interactions), and A is the adjacency matrix [9].

- Feature Matrix Calculation: Compute the feature matrix X based on various topological properties:

- Degree centrality: Measures direct connections [9]

- Betweenness centrality: Identifies nodes on shortest paths [9]

- Closeness centrality: Quantifies information spread efficiency [9]

- Eigenvector centrality: Measures influence based on neighbors' importance [9]

- Clustering coefficient: Assesses interconnectivity of neighbors [9]

Model Implementation:

- Input Layer: Feed the ASD network (nodes and links) into the model [9].

- Feature Processing Layer: Extract neighbors for each node and form adjacency matrix [9].

- GCN Architecture: Apply graph convolutional networks to extract node embeddings [9].

- Logistic Regression Layer: Predict potential key regulator genes using probability scores (0-1 range) [9].

Validation:

- Evaluation: Use susceptible-infected (SI) model to evaluate infection ability of potential key regulator genes [9].

- Comparison: Validate against established databases like SFARI Gene and EAGLE framework [9].

Game Theoretic Centrality for Gene Prioritization

Protocol: Coalitional Game Theory Approach for ASD Gene Ranking

Data Preparation:

- Cohort Selection: Utilize multiplex autism families (recommended: 756 families with 1,965 children) [1].

- Variant Identification: Identify likely gene-disrupting (LGD) variants from whole genome sequence data [1].

Network Integration:

- Biological Network Construction: Incorporate a priori knowledge from biological networks including protein-protein interaction data and pathway information [1].

- Graph Formation: Create computable networks representing various biological systems [1].

Game Theoretic Analysis:

- Coalition Formation: Evaluate coalitions that form among genes and find players that marginally contribute the most on average [1].

- Shapley Value Calculation: Apply game theoretic centrality measure based on Shapley value to rank genes by their relevance in the gene-to-gene interaction network [1].

- Topological Assessment: Explore topological properties of biological networks to study combinatorial effects [1].

Validation & Pathway Analysis:

- Biological Validation: Cross-reference top ranking genes with established ASD gene databases (SFARI, Root 66 gene list) [1].

- Pathway Enrichment: Use Reactome Pathway Browser to identify significant pathways enriched in top ranking genes [1].

- Protein Interaction Checking: Identify direct protein-protein interactions between game theoretic centrality genes and high-confidence candidate ASD genes [1].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table: Detection Rates of Genetic Abnormalities in ASD Populations

| Genetic Testing Approach | Detection Rate in ASD | Key Findings | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal Microarray (CMA) | ~7-10% [5] | Identifies rare or de novo CNVs; reveals recurrent CNV hotspots (1q21.1, 15q13.3, 16p11.2) [5] | First-tier test for non-specific ASD [5] |

| Whole Exome Sequencing | Varies by study [6] | Hundreds of candidate genes identified; most account for <0.5% of cases individually [6] | Identifies de novo mutations in sporadic cases [6] |

| Hybrid Deep Learning | Superior to centrality methods [9] | Higher infection ability for identified genes; aligns with SFARI database [9] | Pinpoints key genetic factors from complex networks [9] |

Table: ASD Subtypes with Distinct Genetic Profiles Identified in Recent Studies

| ASD Subtype | Prevalence | Developmental Trajectory | Genetic Correlations | Key Biological Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social & Behavioral Challenges | 37% [8] | Few developmental delays; later diagnosis [8] | Moderate correlation with ADHD/mental health conditions [10] | Postnatally active genes; neuronal function [8] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% [8] | Early developmental delays [8] | Lower correlation with ADHD/mental health conditions [10] | Prenatally active genes; chromatin organization [8] |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% [8] | Variable presentation [8] | Intermediate genetic profile [8] | Mixed pathway involvement [8] |

| Broadly Affected | 10% [8] | Widespread challenges across domains [8] | Complex polygenic architecture [8] | Multiple disrupted pathways [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is network centrality and why is it important in biological research? Network centrality is a fundamental concept in network analysis that measures the importance or influence of a node (e.g., a gene or protein) within a network. Importance is defined in different ways, leading to different centrality measures [11]. In biological research, such as ASD gene discovery, centrality helps identify essential nodes. These often correspond to genes that are more likely to be associated with indispensability or disease risk when disrupted [12]. Analyzing centrality allows researchers to move beyond simple gene lists to understanding genes' roles within the complex web of molecular interactions [13] [1].

2. How do I choose the right centrality measure for my gene network analysis? The choice depends on the specific biological question you are investigating. The table below summarizes the core applications of three key measures in a biological context:

| Centrality Measure | Best Used For |

|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Identifying genes with many direct interactions (hubs), which are often critical for network stability and can be essential for survival [12] [14]. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Finding bottleneck genes that control information or flow between different network modules. These are potential key regulators in signaling pathways [12] [15]. |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Pinpointing influential genes that are connected to other highly influential genes, suggesting they are part of a central, tightly-knit core complex or pathway [16] [11]. |

3. A known ASD risk gene has a low centrality score in my analysis. Does this mean it's unimportant? Not necessarily. The network's structure and the specific measure used affect results [11]. A gene might have low degree but be functionally critical. It is recommended to use multiple centrality measures and integrate other biological evidence (e.g., gene expression, functional annotations) to get a comprehensive view [12]. Some methods, like game-theoretic centrality, are specifically designed to identify genes that are influential within their local neighborhood rather than the entire network, which may capture important but less globally central genes [1].

4. My betweenness centrality calculations are computationally expensive. Are there efficient alternatives? Yes, computational cost can be a challenge for large networks. While betweenness centrality relies on calculating all shortest paths [16], other measures can provide valuable insights more efficiently. Degree centrality is the fastest to compute [11]. Alternatively, consider using closeness centrality, which identifies nodes that can efficiently reach all other nodes by calculating the inverse of the sum of the shortest paths to all other nodes [16]. For very large networks, investigate approximate algorithms for betweenness calculation or leverage game-theoretic centrality, which has been successfully applied to large genomic datasets [1].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Calculating Centrality Measures for a Protein-Prointeraction Network (PPI)

This protocol outlines the steps to calculate and interpret centrality measures from a PPI network to prioritize candidate genes.

- Network Acquisition and Construction: Obtain a high-quality, context-specific PPI network. Sources like STRING or BioGRID are common starting points. For ASD research, prioritize networks derived from brain tissue or neurodevelopmental stages [13] [1].

- Data Preprocessing: Filter the network to remove low-confidence interactions and ensure the largest connected component is used for analysis to allow calculation of path-based measures like betweenness and closeness.

- Centrality Calculation: Use network analysis tools (e.g., igraph in R, NetworkX in Python) to compute the three centrality measures for every node.

- Gene Ranking and Integration: Rank genes based on each centrality score. Compare these rankings with known ASD gene sets (e.g., from SFARI database) for validation [1]. Finally, integrate the results with other genomic data, such as gene expression from the BrainSpan atlas or gene-level constraint metrics (e.g., pLI scores), to strengthen predictions [13] [12].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Integrating Centrality with Machine Learning for Gene Prediction

This advanced protocol leverages centrality as a feature in a machine learning model to predict novel ASD risk genes, as demonstrated in contemporary studies [13].

- Define Training Set: Curate a set of known positive genes (e.g., high-confidence ASD genes from SFARI) and true negative genes (genes associated with non-neurological diseases) [13].

- Feature Extraction: For each gene, calculate multiple features. This includes:

- Topological Features: Degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality from a biological network [13].

- Gene Constraint Metrics: pLI, LOEUF scores from sources like gnomAD, which quantify a gene's intolerance to mutations [13].

- Spatiotemporal Expression: Features derived from brain gene expression data across development (e.g., from BrainSpan atlas) [13].

- Model Training and Prediction: Train a supervised machine learning classifier (e.g., Random Forest) on the labeled gene set. Use the trained model to score and rank novel genes.

The logical flow of this machine learning approach is shown below:

Quantitative Data on Centrality in Biology

The table below synthesizes key findings from research on the application of centrality measures in biological networks, highlighting their utility and limitations.

| Centrality Measure | Correlation with Essentiality | Key Findings and Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Variable, often positive | Correlates with lethality in some organisms (e.g., yeast) but not always (e.g., E. coli metabolic networks). High-degree nodes are "hubs" whose disruption can destabilize the network [12]. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Positive in many studies | Identifies "bottleneck" nodes. In drug networks, high-betweenness drugs are better candidates for triggering drug repositioning [15]. In PPI networks, it correlates with essentiality [12]. |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Positive | Highlights nodes connected to other influential nodes. It is part of a family of measures that consider a node's connection to important neighbors, making it effective at finding central nodes in a connected core [11] [12]. |

| Combined Measures | Improved Performance | Combining centralities (e.g., degree and closeness) can yield more reliable predictions of essential genes than any single measure [12]. Game-theoretic centrality also identifies influential genes missed by standard measures [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function in Centrality Analysis |

|---|---|

| STRING Database | A database of known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) used to construct the underlying network for analysis [1]. |

| igraph / NetworkX | Open-source software libraries (in R and Python, respectively) used to calculate centrality measures and perform network analysis [16]. |

| BrainSpan Atlas | A resource of spatiotemporal human brain gene expression data. Used to create co-expression networks or validate that candidate genes are active in relevant brain regions and developmental windows [13]. |

| ExAC/gnomAD | Databases providing gene-level constraint metrics (e.g., pLI scores). These quantify a gene's intolerance to loss-of-function mutations and serve as valuable features to integrate with topological data [13]. |

| SFARI Gene Database | A curated resource of genes associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Used as a benchmark "gold standard" set for validating and prioritizing genes identified through centrality analysis [13] [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does a high "degree centrality" score indicate about a gene or protein? A high degree centrality indicates that a gene or protein is a hub in the network, meaning it has a large number of direct interactions with other molecules [17] [18]. Biologically, this often suggests the molecule plays a fundamental, housekeeping role and is involved in key regulatory functions or serves as a critical connector in cellular processes. In protein interaction networks, such hubs are often essential for survival, and their disruption can be lethal [17].

2. How is "betweenness centrality" biologically interpreted? A high betweenness centrality score identifies nodes that act as critical bottlenecks in the network [17]. These genes or proteins often reside on many of the shortest paths between other pairs of nodes, meaning they control the information flow or communication between different network modules. This can indicate a role in coordinating signals between otherwise separate biological processes. Proteins with high betweenness but low connectivity (HBLC proteins) are particularly interesting as they may support network modularization [17].

3. My analysis shows a gene has high "closeness centrality." What does this mean? A gene with high closeness centrality can, on average, reach all other genes in the network in a relatively small number of steps [17]. This suggests it is a highly influential node, positioned to rapidly affect the state of the entire network or to quickly gather information from across the network. In metabolic networks, for example, metabolites with high closeness are often part of central pathways like glycolysis and the citrate acid cycle [17].

4. Why should I use multiple centrality metrics in my analysis? Different centrality metrics highlight nodes with different functional roles [19]. Relying on a single metric provides a limited view, as a node can be central in one aspect (e.g., a local hub with high degree) but not in another (e.g., a global bottleneck with high betweenness). Using multiple metrics—such as degree, betweenness, and closeness—offers a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of a node's importance from various structural perspectives [20] [19].

5. How are centrality measures applied in the context of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) research? In ASD research, centrality-based pathway enrichment methods help identify significant biological pathways dominated by key genes [20]. This is crucial for parsing the extreme genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of ASD. By applying centrality analysis to gene networks, researchers can pinpoint biologically meaningful subtypes of ASD, linking distinct phenotypic classes (e.g., "Social/Behavioral Challenges," "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay") to specific underlying genetic programs and disrupted biological pathways [21] [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Interpreting Contradictory Centrality Scores

Problem: A gene has a high score for one centrality measure (e.g., high degree) but a low score for another (e.g., low betweenness). It is unclear how to interpret its biological importance.

Solution:

- Interpret the Functional Role: This pattern is common and reveals a specific network role. A high-degree, low-betweenness node is typically a local hub within a dedicated functional module, but it does not control flow between modules. Conversely, a low-degree, high-betweenness node acts as a critical bridge or bottleneck connecting different parts of the network [17] [19].

- Cross-Reference with Biological Knowledge: Integrate the structural findings with existing annotation. Check if the gene is known to be part of a large protein complex (consistent with high degree) or a key signaling intermediary (consistent with high betweenness).

- Consult a Decision Matrix: Use the following table to guide your interpretation.

| Centrality Profile | Structural Role | Proposed Biological Interpretation | Common in ASD-Related Pathways? |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Degree, Low Betweenness | Local hub within a module | Core component of a stable complex or a central enzyme in a metabolic pathway. Essential for a specific, localized function. | Yes, e.g., genes within synaptic scaffolding complexes. |

| Low Degree, High Betweenness | Global bottleneck, bridge | Key regulatory molecule, signaling intermediary, or transcription factor that integrates information from multiple pathways. | Yes, e.g., high-betweenness genes connecting neurodevelopmental pathways [17]. |

| High Closeness | Centrally located influencer | A molecule with broad, rapid influence over the network state, potentially a master regulator. | Seen in genes regulating early brain development. |

| High Degree, High Betweenness | Central hub and bottleneck | A molecule of critical, multi-faceted importance. Its disruption is highly likely to have severe, system-wide consequences. | Often found among high-confidence ASD risk genes. |

Issue 2: Integrating Centrality Analysis with Differential Expression for ASD Gene Discovery

Problem: A list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from an ASD case-control study has been generated, but it is challenging to prioritize them for functional validation.

Solution: Implement a Centrality-Based Pathway Enrichment Workflow. This method moves beyond simple gene counting by incorporating the topological structure of biological pathways [20].

Experimental Protocol: Centrality-Based Pathway Analysis

Objective: To identify pathways not just enriched with DEGs, but dominated by topologically central DEGs, which may have greater functional impact.

Methodology:

- Input Data:

- Gene Expression Matrix: From your RNA-seq or microarray experiment (e.g., ASD vs. control).

- Pathway Database: A curated source with topological information, such as the NCI-Nature PID, KEGG, or Reactome [20].

- Map Genes to Pathway Nodes:

- For each pathway, convert the gene set into a graph

G = (V, E), whereVis a set of nodes (proteins, complexes) andEis a set of edges (interactions, reactions) [17] [20]. - Map your DEGs onto these pathway nodes. If any gene in a multi-gene complex node is differentially expressed, mark that node as "affected" [20].

- For each pathway, convert the gene set into a graph

- Calculate Node Centrality:

- Compute a Weighted Pathway Score:

- Instead of a simple count, calculate a pathway significance score (e.g., a modified Fisher's exact test or a Mann-Whitney U test) that weights each DEG by its centrality score within the pathway. This gives more importance to differentially expressed genes that are central hubs or bottlenecks [20].

- Statistical Significance:

- Determine significance of the weighted pathway score through permutation testing, creating a null distribution by randomly shuffling gene labels.

Workflow for Centrality-Based Pathway Analysis

Issue 3: Validating Centrality Findings in a Neurodevelopmental Context

Problem: After identifying high-centrality genes, you need a biologically relevant way to validate their functional importance in neurodevelopment, particularly for ASD.

Solution: Leverage person-centered phenotypic subclassification and single-cell transcriptomic data. Recent large-scale studies provide a framework for linking network topology to clinical and molecular data [21] [22].

Experimental Protocol: Functional Validation of High-Centrality ASD Genes

Objective: To test whether high-centrality genes from your analysis are enriched in specific ASD subtypes and expressed in relevant neuronal cell types.

Methodology:

- Subtype Association Analysis:

- Obtain the list of high-centrality genes from your network analysis.

- Using a dataset like SPARK (n=5,392 individuals), test for enrichment of damaging mutations (e.g., de novo protein-truncating variants) in your gene set within the defined phenotypic subtypes (e.g., "Broadly Affected," "Social/Behavioral") [21] [22].

- Statistical Test: Use a gene-based burden test (e.g., TADA) comparing the rate of mutations in your gene set between subtypes and controls [23] [21].

- Temporal Expression Analysis:

- Use developmental transcriptome data (e.g., BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain) to analyze the expression trajectory of your high-centrality genes.

- Test if they are enriched in co-expression modules specific to particular developmental periods (e.g., mid-fetal prefrontal cortex) [21].

- Single-Cell Resolution:

Functional Validation Strategy for ASD Genes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment & CePa Package [20] | A software platform and specific package for performing centrality-based pathway enrichment analysis, allowing for the integration of topological information into gene set testing. |

| Pathway Interaction Database (PID) [20] | A curated database of biomolecular interactions and pathways, often used for centrality analysis because it includes information on protein complexes and signaling networks. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Data (e.g., from STRING, BioGRID) [18] | Raw data used to construct the networks on which centrality is calculated. Represents physical or functional associations between proteins. |

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Software [20] | A foundational tool for gene set analysis. Centrality-based methods can be viewed as an extension that adds node-weighting to the GSEA procedure. |

| Transmission and De Novo Association (TADA) Model [23] [21] | A Bayesian statistical framework that integrates de novo and rare inherited variants to identify genes with a significant burden of mutations in disease cohorts like ASD. Used for gene discovery and validation. |

| BrainSpan Atlas Data | A resource of developmental transcriptome data from post-mortem human brains, used to validate the temporal expression patterns of high-centrality genes. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Datasets (e.g., from developing human cortex) [23] [21] | Data used to confirm that high-centrality genes are expressed in specific, disease-relevant neuronal cell types at critical developmental time points. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Specificity in Your PPI Network

Problem: The constructed Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network is too large and non-specific, containing a high fraction of human genes, which dilutes potential ASD-relevant signals [24].

Solution:

- Step 1: Filter interactions based on brain-specific expression data. Incorporate gene expression data from resources like the Human Protein Atlas (HBTB RNA-seq data) to focus on genes expressed in relevant brain tissues [24].

- Step 2: Validate network specificity using a Monte-Carlo approach. Randomly sample genes from the HGNC database (using 1000 random seeds) and compare SFARI gene enrichment in your network against random networks. A statistically significant enrichment (e.g., p < 2.2×10⁻¹⁶) confirms network specificity [25] [24].

- Step 3: Apply spatiotemporal expression filters from brain development datasets to ensure biological relevance to neurodevelopment [24].

Guide 2: Overcoming Hub Gene Bias in Centrality Measures

Problem: Betweenness centrality and other centrality measures tend to highlight highly connected hub genes that may not be specifically relevant to ASD pathophysiology [24].

Solution:

- Step 1: Combine multiple centrality measures. Implement game theoretic centrality (Shapley value) which considers synergistic gene influences and may identify different candidates compared to traditional measures [26] [1].

- Step 2: Integrate functional validation data. Correlate centrality rankings with:

- De novo mutation data from ASD cohorts

- RNA-seq data from ASD brain tissue

- Co-expression patterns with known ASD genes [24]

- Step 3: Perform pathway enrichment analysis on top-ranked genes to verify biological relevance to known ASD mechanisms [25] [1].

Guide 3: Validating Centrality-Based Gene Prioritization

Problem: How to determine if centrality-prioritized genes are genuinely relevant to ASD rather than statistical artifacts.

Solution:

- Step 1: Cross-reference with established ASD gene databases including SFARI Gene, "Root 66" differentially expressed genes, and rare variant genes [26] [1].

- Step 2: Conduct protein-protein interaction checks between prioritized genes and high-confidence ASD genes using STRING database [1].

- Step 3: Perform functional enrichment analysis using Reactome Pathway Browser to identify if prioritized genes converge on pathways previously implicated in ASD (e.g., immune system, synaptic function) [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Which centrality measure performs best for ASD gene discovery? Answer*: Current evidence suggests that different centrality measures identify complementary gene sets:

- Betweenness centrality: Effective for identifying bottleneck proteins in PPI networks; correlated with other topological metrics [25]

- Game theoretic centrality: Identifies influential genes that might be missed by traditional measures; only 10-20% overlap with betweenness centrality rankings [26] [1]

- Graph neural networks: Graph Sage models achieve 85.80% accuracy in binary risk classification [27]

Table: Comparison of Centrality Measures for ASD Gene Prioritization

| Centrality Measure | Key Principle | Performance/Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betweenness Centrality | Identifies nodes that frequently lie on shortest paths between other nodes | Correlated with other topological metrics; effectively prioritizes genes in noisy datasets [25] | Tendency to highlight general hub genes not specific to ASD [24] |

| Game Theoretic Centrality | Based on Shapley value; evaluates marginal contribution of genes in networks | Identifies distinct genes (e.g., HLA complex, ATP6AP1); reveals immune pathways in ASD [26] [1] | Limited to well-annotated protein-coding genes; misses non-coding regions [1] |

| Graph Neural Networks (Graph Sage) | Uses machine learning on gene networks with chromosome location features | 85.80% accuracy for binary risk classification; 81.68% for multi-class risk [27] | Requires substantial computational resources and training data [27] |

FAQ 2: How can I improve my PPI network's relevance to ASD? Answer*: Implement a multi-step filtering approach:

- Start with high-confidence ASD genes from SFARI (scores 1-2) as seed nodes [25]

- Extract first interactors from IMEx database to build initial network [25]

- Filter for brain-expressed genes using Human Protein Atlas data (94.3% of nodes in validated networks maintain brain expression) [24]

- Validate enrichment significance against randomly generated networks [25]

FAQ 3: What are the most common pitfalls when applying centrality measures to ASD networks? Answer*: The main pitfalls include:

- Overly large networks: Including ~63% of human protein-coding genes reduces specificity [24]

- Hub gene bias: Highly connected genes may be biologically essential but not ASD-specific [24]

- Ignoring syndromic genes: Separate analysis of syndromic vs. non-syndromic genes improves accuracy (Graph Sage models achieve 90.22% accuracy on syndromic classification) [27]

- Lacking experimental validation: Always complement computational findings with expression data, mutation evidence, or functional studies [24] [1]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Prioritized ASD Gene Network Using Betweenness Centrality

Purpose: To construct and analyze a protein-protein interaction network for prioritizing ASD-associated genes using betweenness centrality [25].

Materials:

- SFARI Gene database (access via https://gene.sfari.org/) [28]

- IMEx database for protein-protein interactions [25]

- Human Protein Atlas for brain expression data [24]

- Network analysis software (e.g., Cytoscape, NetworkX)

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

Network Construction:

Topological Analysis:

- Calculate betweenness centrality for all nodes using formula:

- BC(v) = Σs≠v≠t σst(v)/σst

- Where σst is total shortest paths from node s to t, and σst(v) is number of those passing through v [25]

- Rank genes by decreasing betweenness centrality score

- Calculate betweenness centrality for all nodes using formula:

Validation:

- Perform Monte-Carlo simulation: randomly select 12,598 protein-coding genes from HGNC database 1000 times

- Compare SFARI gene enrichment in your network vs. random networks using one-sample t-test

- Statistically significant enrichment: p-value < 2.2×10⁻¹⁶ [25]

Troubleshooting:

- If network is too large (>13,000 nodes), apply additional brain-specific expression filters

- If betweenness centrality identifies mostly general hub genes, integrate with spatiotemporal expression data [24]

Protocol 2: Implementing Game Theoretic Centrality for ASD Gene Discovery

Purpose: To apply game theoretic centrality based on Shapley value to prioritize influential ASD genes within biological networks [26] [1].

Materials:

- Whole genome sequence data from multiplex autism families [26]

- STRING database for protein-protein interactions [1]

- Coalitional game theory implementation code [26]

Procedure:

- Network Preparation:

- Build a PPI network using data from STRING database

- Include both well-annotated protein-coding genes and any available pseudogene data [26]

Game Theoretic Analysis:

Biological Validation:

- Cross-reference top-ranking genes with:

- SFARI Gene database

- "Root 66" differentially expressed gene set

- Rare variant genes from recent ASD studies [1]

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis using Reactome Pathway Browser

- Focus on pathways with FDR < 0.05, particularly immune system and neuronal function pathways [1]

- Cross-reference top-ranking genes with:

Expected Results:

- Top-ranked genes should include HLA complex genes (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-G, HLA-DRB1) [1]

- Enrichment in immune system pathways (FDR = 2.15×10⁻¹⁵) and endosomal pathways (FDR = 2.15×10⁻¹⁵) [1]

- Approximately 10-20% overlap with betweenness centrality results [26]

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Centrality Integration Workflow for ASD Gene Discovery

Diagram Title: Centrality Integration Workflow for ASD Gene Discovery

ASD Gene Network Centrality Pathways

Diagram Title: ASD Gene Network Centrality Pathways

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Centrality-Based ASD Research

| Research Reagent/Database | Type | Primary Function in ASD Network Analysis | Key Features/Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated database | Provides validated ASD-associated genes for network seeding | Contains gene scores (1-3 confidence levels); syndromic/non-syndromic classification; regularly updated [28] |

| IMEx Database | Protein-protein interaction database | Source of experimentally validated physical interactions for PPI network construction | International consortium data; curated physical interactions; includes multiple organism data [25] |

| Human Protein Atlas | Tissue expression database | Filtering network nodes based on brain-specific expression | RNA-seq data from brain tissues; allows specificity refinement of PPI networks [24] |

| STRING Database | PPI database | Alternative source for protein interaction data | Includes both experimental and predicted interactions; useful for game theoretic centrality [1] |

| Reactome Pathway Browser | Pathway analysis tool | Functional enrichment analysis of prioritized genes | Identifies significantly enriched pathways; FDR correction; connects genes to biological processes [1] |

| ABIDE Dataset | Neuroimaging database | Validation of network findings against brain connectivity data | Resting-state fMRI data from ASD and control subjects; correlation with structural findings [29] |

From Theory to Tool: Methodological Integration of Centrality in Discovery Pipelines

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core premise of using centrality measures in ASD gene discovery? Centrality measures help identify the most "important" or influential genes within complex biological networks, such as protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. The core premise is that genes causing a complex polygenic disorder like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are not isolated; they often work in concert within key biological pathways. By leveraging network centrality, machine learning models can prioritize genes that occupy crucial positions in these networks, moving beyond simple gene-variant lists to understanding their functional relationships [26] [30].

Q2: How does the forecASD model incorporate network centrality? The forecASD model utilizes a brain-specific gene network that integrates various data types, including gene co-expression and PPI evidence. From this weighted network, it extracts multiple network topology features to characterize each gene. These centrality and importance measures include [30]:

- Node Centrality: Degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centralities.

- Algorithmic Measures: PageRank, which counts the number and quality of links to a node.

- Module Analysis: Features like hub score and coreness to identify key modules within the network. These features are then used as input for prediction, allowing the model to learn which network positions are most associated with known ASD risk genes [30].

Q3: What specific problem does the Stacking-SMOTE model address in this field? The Stacking-SMOTE model directly tackles the critical issue of imbalanced datasets in ASD gene prediction. In resources like the SFARI database, the number of known ASD genes (the minority class) is vastly outnumbered by genes not associated with ASD (the majority class). This imbalance can cause machine learning models to become biased and perform poorly in identifying the very genes researchers want to find. Stacking-SMOTE solves this by generating synthetic data for the minority class to create a balanced dataset for training, thereby reducing model bias and overfitting [31].

Q4: My model's performance is poor. How can I troubleshoot data-related issues? Poor performance often stems from problems with the training data. Focus on these areas:

- Check for Class Imbalance: Evaluate the distribution of your positive (ASD risk genes) and negative (non-ASD genes) classes. If there is a severe imbalance, employ resampling techniques like SMOTE, as used in the Stacking-SMOTE model, to rebalance the dataset [31].

- Validate Feature Quality: Ensure the network centrality features are calculated correctly on a relevant biological network. The predictive power of models like forecASD relies heavily on the quality of the underlying PPI and brain-specific co-expression data [30].

- Verify Data Labels: Use high-confidence gene sets for training. For example, many models use SFARI Gene categories (1, 2, 3, and syndromic) as true positives and genes associated with non-mental health diseases as true negatives to ensure label reliability [30].

Q5: What are the key validation steps for a new ASD gene prediction? Robust validation is essential to build confidence in your predictions. A standard protocol includes:

- Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation on your training set to ensure the model is not overfitting.

- Independent Test Sets: Hold out a portion of known high-confidence ASD genes (e.g., from SFARI) to test the final model's performance.

- Enrichment Analysis: Test if the top-ranked predicted genes are statistically enriched for known ASD genes from independent sources or for genes involved in biological pathways previously linked to ASD (e.g., chromatin remodeling, synaptic function) [30].

- Literature & Database Verification: Check predicted genes against recent publications and databases like SFARI to see if they have been independently implicated after your model was trained [26] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Imbalanced Datasets in ASD Gene Prediction

Problem: Your classifier shows high overall accuracy but fails to identify any novel ASD risk genes because it is biased toward the majority class (non-ASD genes).

Solution: Implement the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE).

Protocol:

- Identify Minority Class: Define your positive class (e.g., known ASD genes from SFARI).

- Apply SMOTE: For each instance in the minority class, SMOTE calculates the k-nearest neighbors. It then creates synthetic examples along the line segments joining the minority class instance and its neighbors [31].

- Generate Synthetic Data: This process creates new, synthetic data points for the minority class rather than simply duplicating existing ones, which helps reduce overfitting.

- Re-train Model: Train your model on the newly balanced dataset. The Stacking-SMOTE model demonstrated that this approach can achieve high accuracy (approximately 95.5%) in predicting ASD genes [31].

Issue 2: Integrating and Validating Centrality Features

Problem: The network centrality features you've computed do not improve your model's predictive power for identifying ASD genes.

Solution: Ensure the biological network and centrality measures are contextually relevant to ASD neurobiology.

Protocol:

- Network Selection:

- Feature Extraction: Calculate a diverse set of network features for each gene, as done in forecASD [30]:

- Centrality Measures: Degree, betweenness, eigenvector centrality.

- Influence Measures: PageRank, hub score.

- Topological Measures: Coreness.

- Feature Imputation: For genes present in the expression data but missing from the PPI network, impute their network features using an algorithm like k-Nearest Neighbors [30].

- Biological Validation: Perform enrichment analysis on the genes ranked highly by your model. Check if they are involved in pathways previously associated with ASD, such as synaptic signaling, chromatin remodeling, or the immune system, to confirm the biological relevance of your features [26] [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Model Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes the performance and key characteristics of the discussed models as reported in the literature.

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Technical Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| forecASD [30] | Network-based ensemble classifier | Brain-specific spatiotemporal co-expression, Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks, PageRank & other centrality measures, Gene-level constraint (pLI) | High predictive power; top-ranked genes enriched for known ASD genes and relevant pathways (e.g., chromatin remodeling). |

| Stacking-SMOTE [31] | Hybrid stacking ensemble with SMOTE | Hybrid Gene Similarity (HGS), Synthetic Minority Oversampling (SMOTE), Gradient Boosting-based Random Forest (GBBRF) classifier | ~95.5% accuracy on SFARI gene database; effective handling of imbalanced data. |

| Game Theoretic Centrality [26] | Coalitional Game Theory (CGT) with biological networks | Shapley value to evaluate gene synergy in networks, Incorporation of prior biological knowledge from PPI networks | Successfully prioritized immune system pathways (e.g., HLA genes) and known ASD genes; offers a novel centrality concept. |

| mantis-ml (NDD) [32] | Semi-supervised machine learning | Integration of single-cell RNA-seq data with 300+ features (intolerance, PPI), Inheritance-specific model training | High predictive power (AUCs: 0.84-0.95); top genes were 45-180x more likely to have literature support. |

Detailed Methodology: Stacking-SMOTE Model Workflow

This protocol outlines the step-by-step process for implementing the Stacking-SMOTE model for ASD gene prediction [31].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing:

- Source: Download all candidate ASD genes from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) database (https://gene.sfari.org/).

- Filtering: Utilize genes from categories 1, 2, 3, and 4 for analysis.

- Annotation: Annotate all candidate genes with Gene Ontology (GO) terms, focusing specifically on the Biological Process (BP) branch for relevant functional information.

Gene Similarity Matrix Construction:

- Function: Apply a Hybrid Gene Similarity (HGS) function. This function combines information gain-based methods with graph-based methods to effectively measure the semantic similarity between genes using their GO annotations.

Handling Data Imbalance:

- Technique: Apply the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to the dataset.

- Action: SMOTE generates synthetic data samples for the minority class (known ASD genes) instead of simply duplicating existing data, which creates a balanced dataset and reduces the risk of overfitting.

Base Model Training:

- Algorithms: Train multiple base machine learning classifiers on the balanced dataset. The Stacking-SMOTE model uses Random Forest (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Logistic Regression (LR).

Stacking Ensemble:

- Meta-Classifier: The predictions from the base classifiers (RF, KNN, SVM, LR) are used as input features to train a meta-classifier.

- Meta-Algorithm: The model uses a novel Gradient Boosting-based Random Forest (GBBRF) as the meta-classifier, which combines the strengths of both boosting and Random Forest to form a robust final prediction model.

Evaluation & Prediction:

- The model is evaluated via cross-validation against the SFARI database and other candidate ASD gene sets.

- The final stacked model is used to output predictions and rank novel ASD risk genes.

Detailed Methodology: forecASD Model Workflow

This protocol describes the process for building a network-based model like forecASD that leverages centrality measures [30].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Curate Labeled Gene Set:

- True Positives (TP): Compile a set of high-confidence ASD genes. This typically includes SFARI Gene categories 1 and 2, along with genes from major sequencing studies.

- True Negatives (TN): Compile a set of genes not associated with ASD, such as those linked to non-mental health diseases from resources like OMIM.

Construct a Weighted Functional Network:

- Data Sources:

- Gene Expression: Obtain spatiotemporal RNA-Seq data from the BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain.

- Protein Interactions: Obtain PPI data from a database like InWeb.

- Network Construction: For gene pairs with PPIs, calculate their connection weight based on their Fischer z-transformed Pearson correlation coefficient derived from their BrainSpan expression profiles across all brain regions and developmental stages.

- Data Sources:

Feature Extraction:

- Network Features: For each gene in the network, calculate a suite of network features using a tool like the

igraphpackage in R. These include:- Centrality Measures: Degree, betweenness, eigenvector centrality.

- Influence Algorithms: PageRank.

- Topological Measures: Coreness, hub score.

- Constraint Features: Incorporate gene-level constraint metrics from large-scale sequencing projects (e.g., gnomAD), such as pLI scores and Z-scores for LoF, missense, and synonymous variants.

- Expression Features: Use the log-transformed gene expression values from BrainSpan directly as features.

- Network Features: For each gene in the network, calculate a suite of network features using a tool like the

Model Training and Prediction:

- Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) using the assembled features to distinguish between TP and TN genes.

- The trained model can then score and rank all other genes in the genome based on their predicted probability of being an ASD risk gene.

Biological Validation:

- Perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the top-ranked genes to identify overrepresented biological processes (e.g., neuronal signaling, chromatin remodeling).

- Check for enrichment in independent sets of ASD risk genes not used in training.

- Examine differential expression evidence of top-ranked genes in ASD brain tissues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Experiment | Key Details / Application |

|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | Provides curated lists of ASD candidate genes for model training and validation. | Categories 1, 2, 3, and syndromic genes are often used as high-confidence positive labels; essential for benchmarking [31] [30]. |

| BrainSpan Atlas | Source of spatiotemporal human brain gene expression data (RNA-Seq). | Used to build brain-specific co-expression networks and as direct input features; captures developmental dynamics critical to ASD [30]. |

| InWeb PPI Network | Provides a catalog of protein-protein interactions. | Integrated with expression data to build a functionally weighted gene-gene interaction network for centrality analysis [30]. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | A hierarchical database of gene functional annotations. | Used to calculate semantic similarity between genes (e.g., HGS function) and for post-prediction enrichment analysis [31]. |

| ExAC/gnomAD | Database of genetic variation from a large population. | Source for gene-level constraint metrics (e.g., pLI, missense Z-score), which are key features for predicting gene intolerance to mutation [30]. |

| SMOTE | An algorithm to generate synthetic samples for the minority class in a dataset. | Critical for resolving class imbalance in ASD gene datasets, improving model ability to identify true risk genes [31]. |

| Coalitional Game Theory (CGT) | A mathematical framework to evaluate the marginal contribution of a player (gene) in a coalition. | Used in Game Theoretic Centrality to rank genes by their synergistic influence within a biological network, incorporating prior knowledge [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my prioritized gene list dominated by general cellular housekeeping genes, and how can I make it more specific to ASD neurobiology?

This is a common issue when the Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network is not sufficiently contextualized. A gene with high betweenness centrality might be a general hub, not necessarily specific to brain function or ASD.

- Solution: Integrate brain-specific expression data directly into your gene prioritization. After calculating centrality measures, filter your gene list based on expression levels in relevant brain regions and developmental periods. For example, you can cross-reference your list with data from the BEST (Brain Expression Spatio-Temporal) web server, which provides comprehensive human brain spatio-temporal expression patterns [33]. Retain only genes expressed above a certain threshold (e.g., TPM > 1) in brain regions implicated in ASD, such as the cortex, during critical prenatal or early postnatal developmental windows [34] [35].

Q2: After integrating spatiotemporal data, my gene list becomes too small. How do I balance specificity with statistical power?

Overly stringent spatiotemporal filters can lead to a drastic reduction in candidate genes.

- Solution: Employ a tiered filtering approach instead of a single hard cutoff.

- Tier 1 (High Confidence): Genes with high centrality AND high expression in key brain regions/periods.

- Tier 2 (Medium Confidence): Genes with high centrality OR high expression, plus supporting evidence from other sources (e.g., SFARI gene score, literature).

- Use the gene set from Tier 1 for pathway enrichment analysis to understand core mechanisms, and use the larger set from Tier 2 for hypothesis generation and further validation.

Q3: What are the best public resources to obtain brain spatiotemporal expression data for my candidate genes?

Several high-quality, publicly available resources can be used.

- Primary Resources:

- BEST (Brain Expression Spatio-Temporal pattern web server): A dedicated tool for comprehensive human brain spatio-temporal expression pattern analysis. It allows you to input a gene list and visualize expression quantifications across brain regions and developmental stages [33].

- BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain: Provides transcriptome data from post-mortem human brains across multiple developmental periods and brain structures [33] [35].

- Allen Brain Atlas: Includes data on gene expression in the adult and developing human brain [33].

Q4: How can I visually communicate the logic of combining centrality with spatiotemporal filtering in my research paper?

A clear workflow diagram is the most effective way. The diagram below illustrates the step-by-step process, from data integration to final candidate prioritization.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Weak or No Enrichment in Biologically Relevant Pathways

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Noisy or Non-Biological Centrality. High-centrality genes might be connecting disparate network regions without forming a coherent biological module.

- Action: Before spatiotemporal filtering, perform an initial pathway enrichment analysis on the top-centrality genes. If results are nonspecific (e.g., enriched for "metabolic processes"), your PPI network may lack context. Consider using a brain-specific PPI network if available.

- Cause 2: Incorrect Spatiotemporal Context. You might be looking at the wrong brain region or developmental period.

- Action: Consult the literature to identify the brain regions (e.g., prefrontal cortex, striatum) and developmental periods (e.g., mid-fetal, early childhood) most strongly implicated in ASD [34] [35]. Use the BEST server to systematically test different spatiotemporal categories for enrichment [33].

- Cause 3: Over-Filtering. The combined filters may be too strict, removing genuine signals.

- Action: Widen the spatiotemporal criteria gradually. Instead of requiring high expression in one specific region, consider expression in any of several cortical regions. Re-run the enrichment analysis at each step to find the optimal balance.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Different PPI Databases or Expression Atlases

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Differences in Database Curation. PPI databases have varying curation standards and experimental sources. Expression atlases may use different sequencing platforms, normalization methods, and sample processing protocols.

- Action: This is a known challenge. The best practice is to perform your analysis on two or three consensus datasets.

- For PPI, use a consolidated source like IMEx, as done in the referenced study [25].

- For expression, use a tool like BEST, which integrates data from multiple sources (BrainSpan, GTEx, Allen Brain Atlas) to provide a more robust view [33].

- Report the results that are consistent across multiple data sources as your most reliable findings.

- Action: This is a known challenge. The best practice is to perform your analysis on two or three consensus datasets.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics from a Systems Biology Study on ASD Genes [25]

This table summarizes the core data from a foundational study that built a PPI network from SFARI genes, which you can use as a benchmark for your own experiments.

| Metric | Description | Value in SFARI-Based Network |

|---|---|---|

| Network Nodes | Total proteins in the PPI network. | 12,598 |

| Network Edges | Total physical interactions between proteins. | 286,266 |

| SFARI Gene Coverage | Percentage of high-confidence (Score 1) SFARI genes included in the network. | 96.5% |

| Brain-Expressed Nodes | Percentage of nodes in the network expressed in at least one brain area. | 94.3% |

| Key Centrality Metric | The primary topological measure used for gene prioritization. | Betweenness Centrality |

Protocol 1: Building a PPI Network and Calculating Centrality for ASD Candidate Genes

This protocol outlines the methodology for the initial centrality analysis [25].

- Gene List Curation: Compile a starting list of genes. This can be from databases like SFARI (e.g., scores 1 and 2) or from your own genetic studies (e.g., genes within CNVs of unknown significance).

- Network Generation: Query a consolidated PPI database like IMEx to retrieve both the initial gene products and their first-order interactors.

- Network Construction: Build an undirected PPI network where nodes represent proteins and edges represent physical interactions. Tools like NetworkX in Python can be used for this [36].

- Topological Analysis: Calculate network centrality measures for each node. Betweenness centrality is highly effective, as it identifies nodes that act as bridges connecting different parts of the network [25] [37].

- Prioritization: Rank all genes in the network by their betweenness centrality score in descending order. This is your initial prioritized list.

Protocol 2: Integrating Brain Spatiotemporal Expression Data

This protocol describes how to add a neurobiological context to your computationally prioritized gene list [33] [35].

- Data Source Selection: Access a spatiotemporal brain expression resource. The BEST web server (http://best.psych.ac.cn) is recommended for its user-friendly interface and integrated data [33].

- Input Preparation: Input your ranked gene list into the BEST server. The server can accept a simple list or a list with p-values.

- Spatiotemporal Analysis:

- Generate expression heatmaps to view the expression levels of your gene set across various brain regions and developmental periods.

- Perform cell-type-specific gene set enrichment to see if your genes are overrepresented in specific neural cell types (e.g., neurons, microglia, oligodendrocytes).

- Co-expression Cluster Analysis:

- Use the BEST server to perform co-expression gene cluster enrichment analysis. This identifies if your candidate genes are part of tightly co-regulated gene modules, which often correspond to functional biological pathways.

- Construct co-expression networks to visualize the relationships between your candidate genes within these modules.

- Filtering and Validation: Filter your initial centrality-ranked list, giving priority to genes that are both central and show high expression in ASD-relevant brain spatiotemporal contexts or belong to relevant co-expression clusters.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key datasets and software tools that form the essential "reagents" for conducting these analyses.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis | Access Link / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMEx Database | Protein-Protein Interaction Data | Provides curated, non-redundant physical protein interactions to build the foundational network. | https://www.imexconsortium.org [25] |

| BEST Web Server | Brain Spatiotemporal Expression Tool | Analyzes and visualizes gene expression patterns across human brain regions and developmental stages. | http://best.psych.ac.cn [33] |

| NetworkX (Python) | Software Library | Performs network construction, calculation of centrality measures, and other graph theory analyses. | https://networkx.org [36] |

| SFARI Gene Database | Gene Annotation Database | Provides a curated list of genes associated with ASD, used for benchmarking and initial gene selection. | https://gene.sfari.org [25] |

| BrainSpan Atlas | Transcriptomics Data | Serves as a key data source within BEST for developmental transcriptome information in the human brain. | http://www.brainspan.org [33] [35] |

Diagram: Conceptual Relationship Between Centrality and Spatiotemporal Expression

The following diagram illustrates the core hypothesis behind this feature engineering approach: that the most robust ASD candidate genes lie at the intersection of high network centrality and high brain-relevant spatiotemporal expression.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind using network centrality for ASD gene prioritization? Network centrality operates on the "guilt-by-association" principle. It posits that genes causing the same disease are more likely to interact with each other or reside in the same network neighborhood. By mapping known and candidate ASD genes onto a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network, centrality measures can identify and rank genes based on their topological importance, prioritizing those that occupy strategically important positions for further experimental validation [25].

Q2: My candidate gene list contains many genes of unknown significance. How can forecASD help prioritize them? forecASD is specifically designed to handle noisy datasets, including those with Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS). By mapping your candidate gene list onto the pre-compiled PPI network (e.g., derived from SFARI and IMEx), the tool ranks them based on their betweenness centrality. Genes with higher scores are more likely to be true positives. One study using this method successfully prioritized genes within copy number variants, revealing significant enrichment in pathways like ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis [25].

Q3: How does the Game Theoretic Centrality used in forecASD differ from traditional centrality measures?

Game Theoretic Centrality, based on Shapley value from coalitional game theory, evaluates a gene's synergistic influence within a network. Unlike traditional measures like degree centrality, it considers the combinatorial effect of groups of variants. It preferentially ranks genes that are connected to a large number of genes that themselves have few neighbors, identifying influential players that might be missed by other methods. Studies show it identifies a distinct set of genes (e.g., ATP6AP1, GUCY2F) with lower overlap (10-20%) with genes ranked by degree or betweenness centrality [26] [1].

Q4: I only want to use high-confidence, experimentally validated physical interactions from STRING. How can I configure forecASD? Within the forecASD data settings, you can select specific evidence channels. To use only direct experimental data, you would deselect all evidence sources except for "Experiments". STRING integrates experimental data from sources like BIND, DIP, GRID, HPRD, IntAct, MINT, and PID [38] [39]. This ensures the PPI network is built from physical interactions documented in these databases.

Q5: A gene highly ranked by forecASD has no prior link to ASD in the literature. How should I interpret this result?

This is a key strength of the predictive method. A high rank indicates that the gene is topologically important in a network strongly enriched for validated ASD genes. This can reveal novel, biologically plausible candidates. For example, systems biology approaches have prioritized genes like CDC5L, RYBP, and MEOX2 as novel ASD candidates, while game theoretic methods identified GUCA1C and PDE4DIP, which are involved in pathways linked to neurodevelopment [25] [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Overlap Between Prioritized Genes and Known ASD Genes

Problem: The list of genes prioritized by forecASD shows a low overlap with known, high-confidence ASD genes from databases like SFARI.

Solution:

- Verify Network Specificity: Ensure your background PPI network is sufficiently enriched for ASD biology. The network should be built from core ASD genes (e.g., SFARI Score 1 and 2) and their first interactors. A well-constructed network should contain >95% of known high-confidence SFARI genes, a significantly higher percentage than expected by randomly selecting an equal number of genes from the genome [25].

- Adjust Centrality Measure: Different centrality measures capture different aspects of network importance. Consider using Game Theoretic Centrality, which has been shown to identify a novel set of ASD-associated genes (including immune-related genes like

HLA-A,HLA-B,HLA-G) that have lower overlap with other methods but are biologically validated [26] [1]. - Check for Expression Relevance: Confirm that the top-ranked genes are expressed in the brain. Cross-reference your results with expression data from resources like the Human Protein Atlas; a valid network should have over 94% of its nodes expressed in at least one brain area [25].

Issue 2: Handling Genes Not Found in the STRING PPI Network

Problem: Some candidate genes, particularly non-coding genes or pseudogenes, are missing from the STRING network and are therefore excluded from the analysis.

Explanation: STRING is a locus-based database that typically stores a single protein-coding transcript per gene locus and relies on available protein product annotations [38] [39]. This means poorly annotated genes or pseudogenes are often absent.

Solution:

- Pre-filter Input Genes: Before analysis, filter your candidate gene list against the list of proteins available in STRING for your organism of interest (e.g., human).

- Leverage Orthology: For a gene not found in human STRING, check if orthologs exist in model organisms. STRING uses precomputed orthology to transfer interaction evidence across species, which might provide a proxy network [40].

- Acknowledge the Limitation: This is a known constraint of PPI-based methods. The forecASD framework using Game Theoretic Centrality is primarily limited to well-annotated protein-coding genes, as noted in the original research [1].

Experimental Protocol: Validating Centrality Measures for ASD Gene Discovery

The following protocol outlines the key methodology for using a systems biology approach to prioritize and validate ASD candidate genes, as implemented in tools like forecASD.

Constructing the Autism-Related Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

Objective: To build a comprehensive, ASD-enriched PPI network that will serve as the scaffold for centrality analysis.

Materials & Reagents:

- Source of ASD Genes: Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Gene database (https://gene.sfari.org/).

- PPI Data: International Molecular Exchange Consortium (IMEx) database or the STRING database (https://string-db.org/).

- Computational Environment: A computing environment with programming capabilities (e.g., R, Python) and access to network analysis libraries (e.g., igraph, NetworkX).

Procedure:

- Query the SFARI database to obtain a high-confidence seed list of ASD-associated genes. A typical query focuses on non-syndromic genes with SFARI Score 1 ("high confidence") and Score 2 ("strong candidate").