Benchmarking Network Reconstruction Methods: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking network reconstruction methods, essential for interpreting complex biological data in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Benchmarking Network Reconstruction Methods: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking network reconstruction methods, essential for interpreting complex biological data in biomedical research and drug discovery. It covers foundational concepts, explores diverse methodological approaches and tools, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes robust validation and comparative analysis techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the guide synthesizes current best practices to enhance the reliability, stability, and interpretability of inferred biological networks, thereby strengthening subsequent analyses and accelerating translational applications.

The Why and How: Foundational Principles of Network Reconstruction Benchmarking

The Critical Need for Benchmarking in Network Reconstruction

A fundamental challenge in systems biology is the accurate reconstruction of biological networks—the intricate maps of interactions between genes, proteins, and other cellular components. Over the past decade, a great deal of effort has been invested in developing computational methods to automatically infer these networks from high-throughput data, with new algorithms being proposed at a rate that far outpaces our ability to objectively evaluate them [1]. This evaluation crisis stems primarily from a critical lack: the absence of fully understood, real biological networks to serve as gold standards for validation [1]. Without these benchmarks, determining whether one method represents a genuine improvement over another becomes challenging, impeding progress in the field.

The importance of this challenge extends directly into drug discovery, where mapping biological mechanisms is a fundamental step for generating hypotheses about which disease-relevant molecular targets might be effectively modulated by pharmacological interventions [2]. Accurate network reconstruction can illuminate complex cellular systems, potentially leading to new therapeutics and a deeper understanding of human health [2].

Benchmarking Platforms: From Synthetic Networks to Real-World Data

To address the validation gap, researchers have developed various benchmarking strategies, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below summarizes the primary approaches and their characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Network Reconstruction Benchmarking Strategies

| Benchmark Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico Synthetic Networks | Computer-generated networks with simulated expression data [1] | Known ground truth; High statistical power; Flexible and low-cost [1] | May lack biological realism [1] |

| Well-Studied Biological Pathways | Curated pathways from model organisms (e.g., yeast cell cycle) [1] | Real biological interactions | Uncertainties remain in "gold standard" networks [1] |

| Engineered Biological Networks | Small, synthetically constructed biological networks [1] | Known structure in real biological system | Feasible only for small networks [1] |

| Large-Scale Real-World Data (CausalBench) | Uses single-cell perturbation data with biologically-motivated metrics [2] | High biological realism; Distribution-based interventional measures [2] | True causal graph unknown; Uses proxy metrics [2] |

Several sophisticated software platforms have been developed for benchmarking. GRENDEL (Gene REgulatory Network Decoding Evaluations tooL) generates random regulatory networks with topologies that reflect known transcriptional networks and kinetic parameters from genome-wide measurements in S. cerevisiae, offering improved biological realism over earlier systems [1]. Unlike simpler benchmarks that use mRNA as a proxy for protein, GRENDEL models mRNA, proteins, and environmental stimuli as independent molecular species, capturing crucial decorrelation effects observed in real systems [1].

CausalBench represents a more recent evolution, moving away from purely synthetic data toward real-world, large-scale single-cell perturbation data [2]. This benchmark suite incorporates two cell line datasets (RPE1 and K562) with over 200,000 interventional data points from CRISPRi perturbations, using biologically-motivated metrics to evaluate performance where the true causal graph is unknown [2].

Biomodelling.jl addresses the unique challenges of single-cell RNA-sequencing data by using multiscale modeling of stochastic gene regulatory networks in growing and dividing cells, generating synthetic scRNA-seq data with known ground truth topology that accounts for technical artifacts like drop-out events [3].

Performance Comparison of Reconstruction Algorithms

Extensive benchmarking studies have revealed significant differences in the performance of various network reconstruction methods. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of major algorithm classes based on evaluations across multiple benchmarks.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Network Reconstruction Algorithm Classes

| Algorithm Class | Representative Methods | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Causal Discovery | PC, GES, NOTEARS [2] | No interventional data required | Lower accuracy on complex real-world data [2] |

| Interventional Causal Discovery | GIES, DCDI [2] | Theoretically more powerful with intervention data | Poor scalability limits real-world performance [2] |

| Tree-Based GRN Inference | GRNBoost, SCENIC [2] | High recall on biological evaluation [2] | Low precision [2] |

| Network Propagation | PCSF, PRF, HDF [4] | Balanced precision and recall [4] | Performance depends heavily on reference interactome [4] |

| Challenge Methods | Mean Difference, Guanlab [2] | State-of-the-art on CausalBench metrics [2] | Emerging methods with limited independent validation |

A systematic evaluation using CausalBench revealed that contrary to theoretical expectations, methods using interventional information (e.g., GIES) did not consistently outperform those using only observational data (e.g., GES) [2]. This highlights the gap between theoretical potential and practical performance in real-world biological systems. The evaluation also identified significant scalability issues as a major limitation for many methods when applied to large-scale datasets [2].

In assessments of network reconstruction approaches on various protein interactomes, the Prize-Collecting Steiner Forest (PCSF) algorithm demonstrated the most balanced performance in terms of precision and recall scores when reconstructing 28 pathways from NetPath [4]. The study also found that the choice of reference interactome (e.g., PathwayCommons, STRING, OmniPath) significantly impacts reconstruction performance, with variations in coverage of disease-associated proteins and bias toward well-studied proteins affecting results [4].

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Selected Algorithms on CausalBench Evaluation

| Method | Type | Performance on Biological Evaluation | Performance on Statistical Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference | Interventional | High | Slightly better than Guanlab [2] |

| Guanlab | Interventional | Slightly better than Mean Difference [2] | High |

| GRNBoost | Observational | High recall, low precision [2] | Low FOR on K562 [2] |

| Betterboost & SparseRC | Interventional | Lower performance [2] | Good statistical evaluation performance [2] |

| NOTEARS, PC, GES | Observational | Low information extraction [2] | Varying precision [2] |

Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking Studies

GRENDEL Benchmarking Protocol

The GRENDEL workflow follows a structured approach to generate and evaluate networks [1]:

- Topology Generation: Random regulatory networks are generated as directed graphs with power-law out-degree and compact in-degree distributions to mimic biological networks [1]

- Kinetic Parameterization: Parameters for differential equations are chosen based on genome-wide measurements of protein and mRNA half-lives, translation rates, and transcription rates [1]

- Network Simulation: The system is simulated using SBML integration tools (e.g., SOSlib) to produce noiseless expression data [1]

- Noise Introduction: Experimental noise is added according to a log-normal distribution with user-defined variance [1]

- Algorithm Evaluation: Reconstruction algorithms are run on the simulated data, and their predictions are compared against the known network topology [1]

CausalBench Evaluation Methodology

CausalBench employs a different, biologically-grounded evaluation strategy [2]:

- Data Curation: Integration of two large-scale perturbational single-cell RNA sequencing experiments with over 200,000 interventional data points from CRISPRi perturbations [2]

- Metric Calculation: Uses two complementary evaluation approaches:

- Algorithm Training: Methods are trained on the full dataset multiple times with different random seeds to ensure statistical robustness [2]

- Performance Assessment: Evaluation of the trade-off between precision and recall across methods [2]

CausalBench utilizes real single-cell perturbation data for biologically-grounded method evaluation [2].

Impact of Data Preprocessing and Experimental Design

Benchmarking studies have revealed that data preprocessing and experimental design significantly impact reconstruction accuracy. Research using Biomodelling.jl has demonstrated that imputation methods—algorithms that fill in missing data points in scRNA-seq datasets—affect gene-gene correlations and consequently alter network inference results [3]. The optimal choice of imputation method was found to depend on the specific network inference algorithm being used [3].

The design of gene expression experiments also strongly determines reconstruction accuracy [1]. Benchmarks with flexible simulation capabilities allow researchers to guide not only algorithm development but also optimal experimental design for generating data destined for network reconstruction [1].

Furthermore, studies evaluating network reconstruction on protein interactomes have shown that the choice of reference interactome significantly affects performance, with variations in edge weight distributions, bias toward well-studied proteins, and coverage of disease-associated proteins all influencing results [4].

Multiple factors influence the accuracy of network reconstruction methods [1] [4] [3].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Network Reconstruction Benchmarking

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Interactomes | PathwayCommons, HIPPIE, STRING, OmniPath, ConsensusPathDB [4] | Provide prior knowledge networks for validation and reconstruction |

| Benchmarking Suites | GRENDEL [1], CausalBench [2], Biomodelling.jl [3] | Enable standardized evaluation of reconstruction algorithms |

| Perturbation Technologies | CRISPRi [2] | Enable targeted genetic interventions for causal inference |

| Single-cell Technologies | scRNA-seq [2] [3] | Measure gene expression at single-cell resolution |

| Network Reconstruction Algorithms | PC, GES, NOTEARS, GRNBoost, DCDI [2] | Implement various approaches to infer networks from data |

| Simulation Tools | COPASI, CellDesigner, SBML ODE Solver Library [1] | Simulate network dynamics for in silico benchmarks |

| Evaluation Metrics | Mean Wasserstein Distance, False Omission Rate, Precision, Recall [2] | Quantify algorithm performance on benchmark tasks |

The field of network reconstruction benchmarking is evolving toward greater biological realism and practical applicability. While early benchmarks relied heavily on synthetic data, newer approaches like CausalBench leverage real large-scale perturbation data to provide more meaningful evaluations [2]. Community challenges using these benchmarks have already spurred the development of improved methods that better address scalability and utilization of interventional information [2].

Critical gaps remain, however. The performance trade-offs between precision and recall persist across most methods [2]. The inability of many interventional methods to consistently outperform observational approaches suggests significant room for improvement in how perturbation data is utilized [2]. Furthermore, the dependence of algorithm performance on the choice of reference interactome highlights the need for more comprehensive and less biased biological networks [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these benchmarks provide principled and reliable ways to track progress in network inference methods [2]. They enable evidence-based selection of algorithms for specific applications and help focus methodological development on the most pressing challenges. As benchmarks continue to evolve toward greater biological relevance, they will play an increasingly important role in translating computational advances into biological insights and therapeutic breakthroughs.

The integration of benchmarking into the development cycle—exemplified by the CausalBench challenge which led to the discovery of state-of-the-art methods—demonstrates the power of rigorous evaluation to drive scientific progress [2]. By providing standardized frameworks for comparison, these benchmarks help transform network reconstruction from an art into a science, ultimately accelerating our understanding of cellular mechanisms and enabling more effective drug discovery.

In scientific research, an underdetermined problem arises when the available data is insufficient to uniquely determine a solution, a common scenario in fields ranging from genomics to geosciences. These problems are characterized by having fewer knowns than unknowns, creating a significant challenge for method development and validation. Benchmarking the performance of various computational algorithms designed to tackle these problems is a critical yet formidable task. The core challenge lies in the inherent uncertainty of the ground truth; when a problem is underdetermined, multiple solutions can plausibly fit the available data, making objective performance comparisons exceptionally difficult. This is particularly true for network reconstruction methods, which attempt to infer complex system structures from limited observational data. This guide examines the multifaceted challenges of benchmarking in underdetermined environments and provides a structured comparison of contemporary methodologies across diverse scientific domains.

The Fundamental Obstacles in Benchmarking

Data Scarcity and the Curse of Dimensionality

Underdetermined problems frequently occur in high-dimensional settings where the number of features (m) dramatically exceeds the number of samples (n), creating what's known as the "curse of dimensionality" or Hughes phenomenon [5]. This data underdetermination is particularly common in life sciences, where omics technologies can generate millions of measurements per sample while patient cohort sizes remain limited due to experimental costs and population constraints [5]. In such environments, traditional benchmarking approaches struggle because the fundamental relationship between features and outcomes cannot be precisely established from the limited data, casting doubt on any performance evaluation.

Methodological Heterogeneity and Diverse Assumptions

Reconstruction methods employ vastly different mathematical frameworks and underlying assumptions, complicating direct comparisons. For instance, some approaches assume sparsity in the underlying signal [6], while others leverage nonlinear relationships between features [5]. This diversity means that method performance can vary dramatically across different problem structures, making universal benchmarks potentially misleading. As demonstrated in neural network feature selection, even simple synthetic datasets with non-linear relationships can challenge sophisticated deep learning approaches that lack appropriate inductive biases for the problem structure [5].

Evaluation Metric Selection and Its Biases

The choice of evaluation metrics inherently influences benchmarking outcomes. In CO2 emission monitoring, for instance, methods are evaluated on both instant estimation accuracy (from individual images) and annual-average emission estimates (from full image series), with performance rankings shifting based on the chosen metric [7]. Similarly, in network traffic reconstruction, the Reconstruction Ability Index (RAI) was specifically designed to quantify performance independent of particular deep learning-based services [8]. The absence of universally applicable metrics forces researchers to select context-dependent measures that may favor certain methodological approaches over others.

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Domains

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on Non-linear Synthetic Datasets

| Method Category | Method Name | RING Dataset | XOR Dataset | RING+XOR Dataset | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistical | LassoNet | High | Moderate | Moderate | Limited to linear/additive relationships |

| Tree-Based | Random Forests | High | High | High | Performance relies on heuristics |

| TreeShap | High | High | High | Computational intensity | |

| Information Theory | mRMR | High | High | High | Assumes feature independence |

| Deep Learning-Based | CancelOut | Low | Low | Low | Fails with few decoy features |

| DeepPINK | Low | Low | Low | Struggles with non-linear entanglement | |

| Gradient-Based | Saliency Maps | Low | Low | Low | Poor reliability even with simple datasets |

Table 2: Performance of Data-Driven Inversion Methods for CO2 Emission Estimation

| Method | Interquartile Range (IQR) of Deviations | Number of Instant Estimates | Annual Emission RMSE | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Plume (GP) | 20-60% | 274 | 20% | Most accurate for individual images |

| Cross-Sectional Flux (CSF) | 20-60% | 318 | 27% | Reliable uncertainty estimation |

| Integrated Mass Enhancement (IME) | >60% | <200 | 55% | Simple implementation |

| Divergence (Div) | >60% | <150 | 79% | Suitable for annual estimates from averages |

Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking Studies

Protocol 1: Synthetic Dataset Generation for Feature Selection

The benchmark for neural network feature selection methods employed carefully designed synthetic datasets with known ground truth to quantitatively evaluate method performance [5]:

- Dataset Construction: Created five synthetic datasets (RING, XOR, RING+OR, RING+XOR+SUM, DAG) with n=1000 observations and m=p+k features, where p represents predictive features and k represents irrelevant decoy features

- Non-linear Relationship Modeling: Each dataset embodied different non-linear relationships:

- RING: Circular decision boundaries based on two predictive features

- XOR: Archetypal non-linear separable problem requiring feature synergy

- Composite datasets: Combined multiple non-linear relationships

- Feature Dilution: Varied the number of decoy features (k) to test robustness against irrelevant variables

- Evaluation: Measured the ability of methods to correctly identify the truly predictive features among decoys

Protocol 2: Pseudo-Data Experiments for CO2 Inversion Methods

The benchmarking of data-driven inversion methods for local CO2 emission estimation employed a comprehensive pseudo-data approach [7]:

- Domain Definition: Established a 750 km × 650 km domain centered on eastern Germany

- Synthetic True Emissions: Simulated realistic emission patterns for cities and power plants

- Observation Simulation: Generated synthetic CO2M satellite observations of XCO2 and NO2 plumes

- Scenario Testing: Evaluated methods under different conditions:

- Cloud cover data loss

- Wind uncertainty

- Value of collocated NO2 data

- Performance Quantification: Assessed both instant estimates (from individual images) and annual averages (from full image series)

Protocol 3: Network Reconstruction from Nodal Data

The CALMS methodology for latent network reconstruction employed both simulated and experimental data [9]:

- Data Generation: Created network structures with known adjacency matrices

- Dynamic Process Simulation: Implemented evolutionary ultimatum games on known networks

- Method Application: Applied reconstruction algorithms to infer network topology from nodal data only

- Performance Evaluation: Compared reconstructed networks with ground truth using precision-recall metrics

- Experimental Validation: Tested methods on real economic experimental data with known network structures

Visualization of Methodologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Reconstruction Benchmarking

| Tool/Technique | Function | Domain Applications | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data Generators | Creates datasets with known ground truth | Feature selection, Network reconstruction | [5] [9] |

| Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) | Dimension reduction for physical fields | Flow and heat field reconstruction | [10] |

| Masked Autoencoders | Reconstruction of missing data features | Network traffic analysis | [8] |

| Graph Auto-encoder Frameworks | Representation of semantic and propagation patterns | Rumor detection in social networks | [11] |

| Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) | Optimization algorithm for constrained problems | Network reconstruction with constraints | [9] |

| Total Variation Regularization | Penalizes solutions with sharp discontinuities | Tomographic image reconstruction | [6] |

Benchmarking computational methods for underdetermined problems remains fundamentally challenging due to data scarcity, methodological diversity, and the absence of universal evaluation standards. The quantitative comparisons presented in this guide reveal that no single method dominates across all scenarios or domains. Traditional approaches like Random Forests and TreeShap demonstrate remarkable robustness for non-linear feature selection [5], while hybrid methods that combine physical models with data-driven approaches show promise in field reconstruction tasks [10] [6]. For researchers embarking on benchmarking studies, we recommend: (1) employing multiple synthetic datasets with carefully controlled ground truth; (2) evaluating methods across diverse performance metrics; and (3) transparently reporting methodological assumptions and limitations. As the field evolves, the development of standardized benchmarking protocols and shared datasets will be crucial for meaningful comparative assessment of method performance in underdetermined environments.

In the rigorous world of computational biology and network reconstruction, the evaluation of methodological performance is paramount. Researchers and drug development professionals rely on precise, standardized metrics to distinguish truly innovative methods from incremental improvements. This guide provides a structured framework for benchmarking network reconstruction techniques, focusing on the core principles of accuracy, precision, and validation against a gold standard.

At the heart of robust benchmarking lies the gold standard, a reference benchmark representing the best available approximation of the "true" biological network under investigation. It serves as the foundational baseline against which all new methods are measured [12]. Without this fixed point of comparison, quantifying performance gains in method development becomes subjective and unreliable. This article details the key performance metrics, experimental protocols for their assessment, and the essential tools required for conducting definitive comparison studies in network reconstruction.

Core Performance Metrics Explained

Evaluating a network reconstruction method requires a multi-faceted approach, assessing different aspects of its predictive performance. The following metrics, derived from classification accuracy statistics, form the cornerstone of this assessment [12].

- Accuracy: This metric represents the overall proportion of correct predictions made by the model. It is calculated as the sum of true positives and true negatives divided by the total number of predictions [13]. While providing a coarse-grained measure of performance, accuracy can be misleading for imbalanced datasets where one class (e.g., non-existent edges) vastly outnumbers the other (e.g., true edges) [13].

- Precision: Also known as Positive Predictive Value, precision measures the reliability of positive predictions. It answers the question: "Of all the edges the model predicted to exist, what fraction actually exists?" [13]. High precision is critical in scenarios where the cost of false positives (spurious edges) is high, such as when downstream experimental validation is expensive or time-consuming.

- Recall (Sensitivity): Recall measures the model's ability to identify all the actual positives in a network. It answers the question: "Of all the true edges that exist, what fraction did the model successfully recover?" [13]. A high recall is desirable when missing a true interaction (a false negative) could lead to the omission of a critical pathway component.

- Specificity: Specificity measures the model's ability to identify true negatives correctly. It is the proportion of true negatives (correctly predicted non-edges) out of all actual negatives [12].

- F1 Score: The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances the trade-off between the two [13]. It is particularly useful when you need to find a balance between precision and recall and when dealing with an uneven class distribution.

Table 1: Definitions and Formulae of Key Performance Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Formula | Interpretation in Network Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Overall proportion of correct predictions. | (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) [13] | How often is the model correct about an edge's presence or absence? |

| Precision | Proportion of predicted edges that are true edges. | TP / (TP + FP) [13] | How reliable is a positive prediction from the model? |

| Recall / Sensitivity | Proportion of true edges that are successfully recovered. | TP / (TP + FN) [13] | How complete is the model's reconstruction of the true network? |

| Specificity | Proportion of true non-edges that are correctly identified. | TN / (TN + FP) [12] | How well does the model avoid predicting spurious edges? |

| F1 Score | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) [13] | A balanced measure of the model's positive predictive power. |

Abbreviations: TP = True Positive, TN = True Negative, FP = False Positive, FN = False Negative.

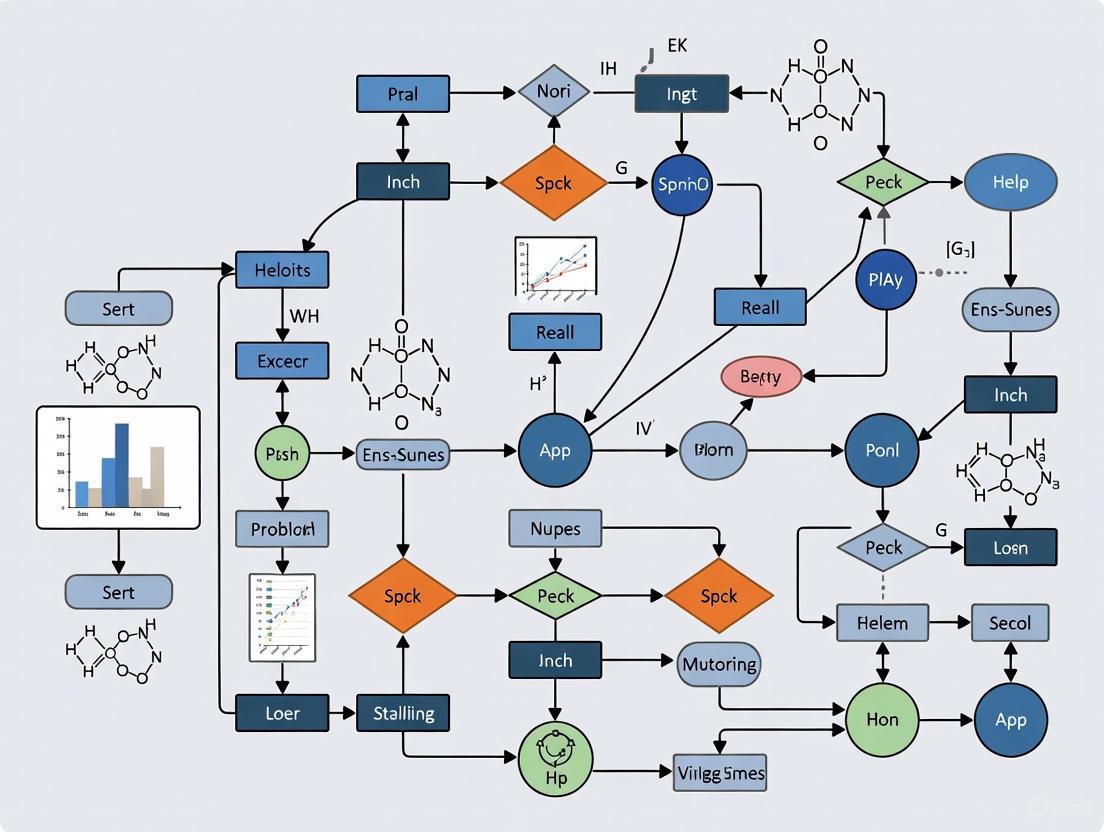

The relationships and trade-offs between these metrics, particularly precision and recall, can be complex. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for calculating these metrics from a confusion matrix and highlights the inherent trade-off between precision and recall.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Calculating Performance Metrics from a Confusion Matrix.

The Role of the Gold Standard

A gold standard is a benchmark that represents the best available approximation of the truth under reasonable conditions [12]. In network reconstruction, this typically refers to a curated, experimentally validated network where interactions are supported by robust, direct evidence (e.g., from siRNA screens, mass spectrometry, or ChIP-seq data). It is not a perfect, omniscient representation of the network, but merely the best available one against which new methods can be fairly compared [12].

The concept of ground truth is closely related but distinct. While a gold standard is a diagnostic method or reference with the best-accepted accuracy, ground truth represents the reference values or known outcomes used as a standard for comparison [12]. For example, a gold-standard protein-protein interaction network from the literature provides the structure, and the specific list of known true edges within it serves as the ground truth for evaluating a new algorithm's recall.

The process of establishing a new gold standard is rigorous. It requires exhaustive evidence and consistent internal validity before it is accepted as the new default method in a field, replacing a former standard [12]. This process is critical for driving progress, as it continuously raises the bar for methodological performance.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison of network reconstruction methods, a standardized experimental protocol is essential. The following workflow outlines the key stages, from data preparation to performance reporting.

Diagram 2: A Standardized Workflow for Benchmarking Network Reconstruction Methods.

Detailed Methodology

Gold Standard and Data Acquisition:

- Select a recognized, curated gold-standard network relevant to the biological context (e.g., a signaling pathway in humans). Sources include dedicated databases like KEGG, Reactome, or organism-specific interaction databases.

- Acquire the input data (e.g., gene expression datasets from GEO or TCGA) that will serve as the input for all methods being benchmarked. Ensure the dataset is independent of the data used to build the gold standard to avoid circularity.

Execution of Methods:

- Run each network reconstruction method (e.g., GENIE3, PANDA, ARACNe) on the identical input dataset.

- Control for technical variability by using the same computational environment (hardware, operating system) for all runs. Document all software versions and parameters used.

Performance Calculation and Comparison:

- For each method, compare its ranked list of predicted edges against the gold standard network.

- By applying a threshold to the ranked list, generate a confusion matrix (counting TP, FP, TN, FN) for that method.

- Vary the prediction threshold across its full range to calculate the metrics at different stringency levels. This allows for the creation of Precision-Recall curves, which are highly informative for evaluating performance over all possible thresholds.

Robustness and Statistical Testing:

- Employ cross-validation or bootstrapping to assess the robustness of each method's performance. This involves repeatedly subsampling the input data, rerunning the methods, and recalculating metrics.

- Perform appropriate statistical tests (e.g., paired t-tests on AUC-PR values from multiple bootstrap iterations) to determine if observed performance differences between the leading method and alternatives are statistically significant.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful benchmarking study relies on more than just algorithms; it requires a suite of high-quality data, software, and computational tools. The following table details the essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Benchmarking Network Reconstruction

| Item Name / Category | Function / Purpose in Benchmarking | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Gold-Standard Network | Serves as the reference "ground truth" for evaluating the accuracy of reconstructed networks. | KEGG Pathways, Reactome, STRING (high-confidence subset). Must be relevant to the organism and network type (e.g., signaling, metabolic). |

| Input Omics Datasets | Provides the raw data from which networks will be inferred. Used as uniform input for all methods. | RNA-Seq gene expression data from GEO or TCGA. Proteomics data from PRIDE. Should be large enough for robust inference and statistical testing. |

| Reference Method Implementations | The software implementations of the network reconstruction algorithms being compared. | GENIE3, PANDA, ARACNe, WGCNA. Use official versions from GitHub or Bioconductor. Parameter settings must be documented and consistent. |

| Benchmarking Framework Software | A computational environment to automate the execution, evaluation, and comparison of multiple methods. | Custom Snakemake or Nextflow workflows; R/Bioconductor packages like evalGS. Essential for ensuring reproducibility. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power needed to run multiple network inference methods, which are often computationally intensive. | Local university clusters or cloud computing services (AWS, GCP). Necessary for handling large datasets and complex algorithms in a reasonable time. |

The rigorous benchmarking of network reconstruction methods is a critical function that enables meaningful scientific progress. By adhering to a framework built on clearly defined metrics like accuracy and precision, and by validating all findings against a carefully chosen gold standard, researchers can provide credible, actionable comparisons. This guide outlines the necessary components—definitions, experimental protocols, and essential tools—to conduct such evaluations. As the field evolves with new data types and algorithmic strategies, these foundational principles of performance assessment will remain essential for evaluating claims of improvement and for building reliable models that can truly accelerate drug development and scientific discovery.

In the field of computational biology, inferring accurate networks—such as gene regulatory networks (GRNs) or functional connectivity (FC) in the brain—from experimental data is fundamental to understanding complex biological systems. The performance of network reconstruction methods is not solely dependent on the algorithms themselves but is profoundly influenced by underlying data characteristics, including sample size, noise, and temporal resolution. This guide objectively compares the performance of various network inference methods by examining how these data pitfalls impact results, providing a structured overview of experimental protocols, benchmarking data, and key reagents used in this critical area of research.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Network Inference

Benchmarking the performance of network inference methods against data pitfalls requires a structured approach using realistic synthetic data where the ground truth is known. The following protocols are commonly employed in the field.

Protocol 1: Assessing Impact of Temporal Sampling Resolution

This protocol evaluates how the time interval between data points affects parameter estimation for dynamic biological transport models, such as the Velocity Jump Process (VJP) used to model bacterial motion or mRNA transport [14].

- Data Generation: Synthetic data is generated via stochastic simulations of the VJP model. This model describes a "run-and-reorientate" motion, characterized by a reorientation rate (λ) and a fixed running speed [14].

- Introduction of Noise and Sampling: The clean trajectory data is corrupted with measurement noise, typically drawn from a wrapped Normal distribution, N(0, σ²). The temporal sampling resolution is varied by sub-sampling the full, high-resolution trajectory at different intervals [14].

- Parameter Inference: For each coarsely-sampled and noisy dataset, Bayesian inference is performed using a Particle Markov Chain Monte Carlo (pMCMC) framework. This method treats the true states of the system as hidden, allowing for exact inference of the reorientation rate (λ) and noise amplitude (σ) despite incomplete observations [14].

- Performance Evaluation: The posterior distributions of λ and σ obtained from the pMCMC analysis are compared against the known true values. The sensitivity of these estimates to different levels of temporal sampling and noise quantifies the impact of these data pitfalls [14].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking with Synthetic scRNA-seq Data

This protocol tests the robustness of GRN inference methods to technical noise and data sparsity (dropouts) inherent in single-cell RNA-sequencing data [3].

- Ground Truth Network Generation: A known ground truth GRN with a specific topology (e.g., scale-free) is defined. Tools like

Biomodelling.jluse multiscale, agent-based modeling to simulate stochastic gene expression within a population of growing and dividing cells, producing realistic synthetic scRNA-seq data [3]. - Data Pre-processing with Imputation: The synthetic data, which contains simulated technical zeros (dropouts), is processed using various imputation methods (e.g.,

MAGIC,scImpute,SAVER). These methods attempt to distinguish biological zeros from technical artifacts and fill in missing values [3]. - Network Inference: Multiple GRN inference algorithms (e.g., correlation-based, mutual information-based, regression-based) are applied to both the raw and imputed datasets [3].

- Performance Evaluation: The inferred networks are compared against the known ground truth. Standard metrics like Precision, Recall, and the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) are calculated to determine which combination of imputation and inference methods performs best under different levels of data sparsity and noise [3].

Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods

The performance of network inference methods varies significantly depending on the data characteristics and the specific application. The tables below summarize key benchmarking findings.

Table 1: Impact of Data Pitfalls on Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) Inference from scRNA-seq Data [3]

| Inference Method Category | Key Data Pitfall | Impact on Performance | Best-Performing Pre-processing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Data sparsity (dropouts) | Significantly reduces gene-gene correlation accuracy | Specific imputation methods (varies) |

| Mutual Information | Data sparsity (dropouts) | Performance decreases with increased sparsity | Specific imputation methods (varies) |

| Regression-based | Data sparsity (dropouts) | Performance decreases with increased sparsity | Specific imputation methods (varies) |

| General Finding | Network Topology | Multiplicative regulation is more challenging to infer than additive regulation | N/A |

| General Finding | Network Complexity | Number of combination reactions (multiple regulators), not network size, is a key performance determinant | N/A |

Table 2: Performance of Functional Connectivity (FC) Methods in Brain Mapping (Benchmarking of 239 pairwise statistics) [15]

| Family of FC Methods | Correspondence with Structural Connectivity (R²) | Relationship with Physical Distance | Individual Fingerprinting Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariance (e.g., Pearson's) | Moderate | Moderate inverse relationship | Varies |

| Precision (e.g., Partial Correlation) | High | Moderate inverse relationship | High |

| Stochastic Interaction | High | Moderate inverse relationship | Varies |

| Imaginary Coherence | High | Moderate inverse relationship | Varies |

| Distance Correlation | Moderate | Moderate inverse relationship | Varies |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources, including software tools and gold-standard datasets, essential for conducting benchmarking studies in network inference.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Benchmarking

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

Biomodelling.jl |

Synthetic scRNA-seq data generator | Julia-based tool; simulates stochastic gene expression in dividing cells with known GRN ground truth [3]. |

pyspi (Python Statistics Package for Imaging) |

Calculation of pairwise interaction statistics | Package used to compute 239 different functional connectivity matrices from time-series data [15]. |

| Gold Standard Biological Networks | Ground truth for benchmarking | Includes databases like RegulonDB for E. coli, and synthetic networks from DREAM challenges [16]. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data | Source of real brain imaging data | Provides resting-state fMRI time series from healthy adults for benchmarking FC methods [15]. |

| Particle MCMC (pMCMC) Framework | Bayesian parameter inference for partially observed processes | Enables estimation of model parameters (e.g., reorientation rates) from noisy, discrete-time data [14]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for the key experimental protocols discussed.

Graph 1: GRN inference benchmarking workflow with synthetic data.

Graph 2: Functional connectivity method benchmarking pipeline.

Biological networks are fundamental computational frameworks for representing and analyzing complex interactions in biological systems. Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) and Relevance Networks represent two critical approaches for modeling these interactions, each with distinct theoretical foundations and applications. GRNs are collections of molecular regulators that interact with each other and with other substances in the cell to govern gene expression levels of mRNA and proteins, which ultimately determine cellular function [17]. In contrast, Relevance Networks represent a statistical approach for inferring associations between biomolecules based on their expression profiles or other quantitative measurements, following a "guilt-by-association" heuristic where similarity in expression profiles suggests shared regulatory regimes [18].

The reconstruction of these networks from experimental data serves different but complementary purposes in systems biology and drug discovery. While GRNs focus specifically on directional regulatory relationships between genes, transcription factors, and other regulatory elements, Relevance Networks identify broader associative relationships that can include co-expression, protein-protein interactions, and other functional associations [18] [19]. Understanding the performance characteristics, appropriate applications, and methodological requirements of each network type is essential for researchers selecting computational approaches for specific biological questions.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs)

GRNs represent causal biological relationships where molecular regulators interact to control gene expression. At their core, GRNs consist of transcription factors that bind to specific cis-regulatory elements (such as promoters, enhancers, and silencers) to activate or repress transcription of target genes [17] [20]. These networks form the basis of complex biological processes including development, cellular differentiation, and response to environmental stimuli.

The nodes in GRNs typically represent genes, proteins, mRNAs, or protein/protein complexes, while edges represent interactions that can be inductive (activating, represented by arrows or + signs) or inhibitory (repressing, represented by blunt arrows or - signs) [17]. A key feature of GRNs is their inclusion of feedback loops and network motifs that create specific dynamic behaviors:

- Positive feedback loops amplify signals and can create bistable switches

- Negative feedback loops stabilize gene expression and maintain homeostasis

- Feed-forward loops process information and generate temporal patterns in gene expression [17] [20]

GRNs naturally exhibit scale-free topology with few highly connected nodes (hubs) and many poorly connected nodes, making them robust to random failure but vulnerable to targeted attacks on critical hubs [17]. This organization evolves through both changes in network topology (addition/removal of nodes) and changes in interaction strengths between existing nodes [17].

Relevance Networks

Relevance Networks represent a statistical approach for inferring associations between biomolecules based on quantitative measurements of their abundance or activity. The generalized relevance network approach reconstructs network links based on the strength of pairwise associations between data in individual network nodes [18]. Unlike GRNs that model specific directional regulatory relationships, Relevance Networks initially generate undirected association networks that can be further refined to causal relevance networks with directed edges.

The methodology involves three key components:

- Association measurement using correlation coefficients, mutual information, or distance metrics

- Marginal control of associations to distinguish direct from indirect influences

- Symmetry breaking to infer directionality in relationships [18]

Relevance Networks are particularly valuable for hypothesis generation when prior knowledge of specific regulatory mechanisms is limited, as they can identify potential relationships for further experimental validation [18] [21].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Framework for Benchmarking

Comprehensive evaluation of network inference methods requires standardized datasets with known ground truth. The performance analysis presented here draws from a large-scale empirical study comparing 114 variants of relevance network approaches on 86 network inference tasks (47 from time-series data and 39 from steady-state data) [18]. Evaluation datasets included:

- Real microarray measurements from Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- Simulated networks with known topology for controlled performance assessment

- In silico networks with varying complexity and connectivity patterns

Performance was evaluated using multiple metrics including precision-recall characteristics, area under the curve (AUC) metrics, and topological accuracy compared to gold standard networks [18].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods

| Method Category | Data Type | Optimal Association Measure | Precision Range | Recall Range | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance Networks | Steady-state | Correlation with asymmetric weighting | 0.25-0.45 | 0.30-0.50 | Large networks (>100 nodes) |

| Causal Relevance Networks | Time-series | Qualitative trend measures | 0.35-0.55 | 0.25-0.40 | Short time-series (<10 points) |

| GRN-Specific Methods | Time-series | Dynamic time wrapping + mutual information | 0.40-0.60 | 0.20-0.35 | Small networks with known regulators |

Table 2: Impact of Data Characteristics on Inference Performance

| Data Characteristic | Effect on Relevance Networks | Effect on GRN Methods | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short time series (<10 points) | Significant performance degradation | Moderate performance decrease | Qualitative trend association measures |

| Large network size (>100 nodes) | Good scalability with correlation measures | Computational challenges | Correlation with asymmetric weighting |

| High noise levels | Information measures outperform correlation | Bayesian approaches more robust | Mutual information with appropriate filtering |

| Sparse connectivity | Improved precision across methods | Significant performance improvement | Multiple association measures with consensus |

The benchmarking data reveals several key insights:

- Correlation-based measures combined with asymmetric weighting schemes generally provide optimal performance for relevance networks across diverse data types [18]

- For short time-series data and large networks, association measures based on identifying qualitative trends in time series outperform traditional correlation approaches [18]

- The performance gap between methods narrows with increasing data quantity, suggesting that methodological choices are most critical in data-limited scenarios [18]

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

GRN Inference Methodologies

GRN inference employs diverse computational approaches, each with specific strengths and data requirements:

Boolean Network Models represent gene states as binary values (on/off) using logical operators (AND, OR, NOT) to define regulatory interactions. These models are computationally efficient for large-scale networks and capture qualitative behavior but lack quantitative and temporal resolution [20].

Differential Equation Models describe continuous changes in gene expression levels over time using ordinary or stochastic differential equations. These provide detailed dynamics and quantitative predictions but require extensive parameter estimation and are computationally intensive [20].

Bayesian Network Models represent probabilistic relationships between genes using directed acyclic graphs to model causal interactions. They effectively incorporate uncertainty and prior knowledge, enabling learning of network structure from data while handling missing information [20].

Information Theory Approaches quantify information flow and dependencies in GRNs using mutual information and transfer entropy to detect directed information transfer. The ARACNE algorithm applies data processing inequality to infer direct interactions [20].

Relevance Network Implementation

The generalized relevance network approach follows a standardized protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize expression data, handle missing values, and apply appropriate transformations

- Association Calculation: Compute pairwise associations using selected measures (correlation, mutual information, or distance-based metrics)

- Statistical Filtering: Apply thresholds to distinguish significant associations from noise

- Directionality Inference (for causal networks): Use time-shifting or conditional independence tests to infer edge direction

Table 3: Association Measures for Relevance Network Construction

| Measure Type | Specific Measures | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Pearson, Spearman | Computational efficiency, intuitive interpretation | Limited to linear or monotonic relationships |

| Information-based | Mutual information, Transfer entropy | Captures non-linear dependencies, flexible | Requires more data, computationally intensive |

| Distance-based | Euclidean, Dynamic time wrapping | Works with various data types, handles time-series | Sensitive to normalization, distance metric choice critical |

Experimental Workflow for Network Inference

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for comparative network inference:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Network Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Profiling | RNA-seq, Microarrays, Single-cell RNA-seq | Genome-wide transcript level measurement | Gene expression data for network inference |

| Regulatory Element Mapping | ChIP-seq, ChIP-chip, CUT&RUN | Identify transcription factor binding sites | GRN construction and validation |

| Perturbation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, RNA interference, Chemical perturbations | Targeted manipulation of network nodes | Experimental validation of inferred networks |

| Computational Platforms | Cytoscape, Gephi, NetworkX, igraph | Network visualization and analysis | Topological analysis and visualization |

| Specialized Software | ARACNE, FANMOD, Boolean network simulators | Network inference and motif discovery | Implementation of specific inference algorithms |

| Data Resources | STRING, GeneMANIA, KEGG, TCMSP | Prior knowledge and reference networks | Integration of existing biological knowledge |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Network-based approaches have demonstrated significant utility in pharmaceutical research, particularly through network pharmacology paradigms that leverage GRNs and relevance networks for target identification and drug repurposing [22] [23] [19].

Target Identification and Validation

GRNs enable systematic target identification by modeling disease states as network perturbations. The "central hit" strategy targets critical network nodes in flexible networks (e.g., cancer), while "network influence" approaches redirect information flow in rigid systems (e.g., metabolic disorders) [22]. For example, network analysis of the Hippo signaling pathway revealed context-dependent network topology that controls both mitotic growth and post-mitotic cellular differentiation [17].

Drug Repurposing and Combination Therapy

Relevance networks facilitate drug repurposing by identifying network-based drug similarities that transcend conventional therapeutic categories. By analyzing how drug perturbations affect network states rather than single targets, researchers can identify novel therapeutic applications for existing compounds [23] [19]. Network-based integration of multi-omics data has been successfully applied to various cancer types, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and colorectal cancer (CRC), leading to identification of combination therapies that target network vulnerabilities [23].

Toxicity Prediction and Safety Assessment

Both GRNs and relevance networks contribute to preclinical safety assessment by modeling off-target effects within integrated biological networks. By simulating drug effects on network stability and identifying critical nodes whose perturbation could lead to adverse effects, these approaches help prioritize candidates with optimal efficacy-toxicity profiles [22] [19].

Signaling Pathways and Network Motifs

Biological networks contain recurrent patterns of interactions called network motifs that perform specific information-processing functions. The following diagram illustrates common network motifs in GRNs:

These motifs represent functional units within larger networks:

- Feed-forward loops process information and generate temporal patterns in gene expression, potentially accelerating metabolic transitions or providing noise resistance [17]

- Feedback loops create bistable switches or homeostatic control mechanisms that maintain cellular stability

- Autoregulatory circuits enable robust maintenance of cellular states and identity

Future Directions and Methodological Challenges

Despite significant advances, network inference methods face several persistent challenges that guide future methodological development:

Multi-omics Integration

The integration of diverse data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) remains computationally challenging due to differences in scale, noise characteristics, and biological interpretation [19]. Future methods must develop standardized integration frameworks that maintain biological interpretability while leveraging complementary information across omics layers [23] [19].

Dynamic Network Modeling

Most current network models represent static interactions, while biological systems are inherently dynamic. Future approaches need to incorporate temporal and spatial dynamics to capture how network topology changes during development, disease progression, and therapeutic intervention [20] [19].

Machine Learning and AI Integration

Graph neural networks and other AI approaches show promise for handling the complexity and scale of modern biological datasets [19]. However, these methods must balance predictive performance with biological interpretability to provide actionable insights for drug discovery [23] [19].

Validation Standards

The field requires standardized evaluation frameworks and benchmark datasets to enable meaningful comparison across methods and applications. Establishing community standards will accelerate methodological advances and facilitate adoption in pharmaceutical development pipelines [18] [19].

Tools of the Trade: A Guide to Reconstruction Algorithms and Benchmarking Frameworks

Network reconstruction algorithms are computational methods designed to infer biological networks from high-throughput data, enabling researchers to elucidate complex interactions within cellular systems. In genomics and transcriptomics, these methods transform gene expression profiles into interaction networks, where nodes represent genes and edges represent statistical dependencies or regulatory relationships. The choice of algorithm significantly impacts the biological insights gained, as each method operates on different mathematical principles and makes distinct assumptions about the underlying data. Correlation networks form the simplest approach, identifying connections based on co-expression patterns, while more advanced methods like CLR, ARACNE, and WGCNA extend this foundation with information-theoretic and network-topological frameworks. Bayesian methods introduce probabilistic modeling to capture directional relationships and manage uncertainty. Understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and performance characteristics of these major algorithm families is essential for their appropriate application in decoding biological systems, particularly in therapeutic target identification and drug development pipelines.

Algorithm Families: Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Correlation Networks

Correlation networks represent the most fundamental approach to network reconstruction, operating on the principle that strongly correlated expression patterns suggest functional relationships or coregulation. These networks are typically constructed by calculating pairwise correlation coefficients between all gene pairs, then applying a threshold to create an adjacency matrix. The Pearson correlation coefficient measures linear relationships, while Spearman rank correlation captures monotonic nonlinear associations. Although simple and computationally efficient, conventional correlation networks face significant limitations, including an inability to distinguish direct from indirect interactions and sensitivity to noise and outliers. The most widespread method—thresholding on the correlation value to create unweighted or weighted networks—suffers from multiple problems, including arbitrary threshold selection and limited biological interpretability [24]. Newer approaches have improved upon basic correlation methods through regularization techniques, dynamic correlation analysis, and integration with null models to identify statistically significant interactions [24].

Context Likelihood of Relatedness (CLR)

The Context Likelihood of Relatedness (CLR) algorithm extends basic correlation methods by incorporating contextual information to eliminate spurious connections. CLR calculates the mutual information between each gene pair but then normalizes these values against the background distribution of interactions for each gene. This approach applies a Z-score transformation to mutual information values, effectively filtering out indirect interactions that arise from highly connected hubs or measurement noise. The mathematical implementation involves calculating the likelihood of a mutual information score given the empirical distribution of scores for both participating genes. For genes i and j with mutual information MI(i,j), the CLR score is derived as:

CLR(i,j) = √[Z(i)^2 + Z(j)^2] where Z(i) = max(0, [MI(i,j) - μ_i] / σ_i)

where μ_i and σ_i represent the mean and standard deviation of the mutual information values between gene i and all other genes in the network. This contextual normalization enables CLR to outperform simple mutual information thresholding, particularly in identifying transcription factor-target relationships with higher specificity [25].

ARACNE (Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks)

ARACNE employs an information-theoretic framework based on mutual information to identify statistical dependencies between gene pairs while eliminating indirect interactions using the Data Processing Inequality (DPI) theorem. Unlike correlation-based methods, ARACNE can detect non-linear relationships, making it particularly suitable for modeling complex regulatory interactions in mammalian cells [26]. The algorithm operates in three key phases: first, it calculates mutual information for all gene pairs using adaptive partitioning estimators; second, it removes non-significant connections based on a statistically determined mutual information threshold; third, it applies the DPI to eliminate the least significant edge in any triplet of connected genes, effectively removing indirect interactions mediated through a third gene [27].

The core innovation of ARACNE lies in its application of the DPI, which states that for any triplet of genes (A, B, C) where A regulates C only through B, the following relationship holds: MI(A,C) ≤ min[MI(A,B), MI(B,C)]. ARACNE examines all gene triplets and removes the edge with the smallest mutual information, preserving only direct interactions. This approach has proven particularly effective in reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks, with experimental validation demonstrating its ability to identify bona-fide transcriptional targets in human B cells [26]. The more recent ARACNe-AP implementation uses adaptive partitioning for mutual information estimation, achieving a 200× improvement in computational efficiency while maintaining network reconstruction accuracy [27].

WGCNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis)

WGCNA takes a systems-level approach to network reconstruction by constructing scale-free networks where genes are grouped into modules based on their co-expression patterns across samples. Unlike methods that focus on pairwise relationships, WGCNA emphasizes the global topology of the interaction network, identifying functionally related gene modules that may correspond to specific biological pathways or processes [25]. The algorithm follows a multi-step process: first, it constructs a similarity matrix using correlation coefficients between all gene pairs; second, it transforms this into an adjacency matrix using a power function to approximate scale-free topology; third, it calculates a topological overlap matrix to measure network interconnectedness; finally, it uses hierarchical clustering to identify modules of highly co-expressed genes [25] [28].

A key innovation in WGCNA is its use of a soft thresholding approach that preserves the continuous nature of co-expression relationships rather than applying a hard threshold. This is achieved through the power transformation a_ij = |cor(x_i, x_j)|^β, where β is chosen to approximate scale-free topology. The topological overlap measure further refines the network structure by quantifying not just direct correlations but also shared neighborhood structures between genes. Recent extensions like WGCHNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Hypernetwork Analysis) have introduced hypergraph theory to capture higher-order interactions beyond pairwise relationships, addressing a key limitation of traditional WGCNA [28]. In this framework, samples are modeled as hyperedges connecting multiple genes, enabling more comprehensive analysis of complex cooperative expression patterns.

Bayesian Networks

Bayesian networks represent a probabilistic approach to network reconstruction, modeling regulatory relationships as directed acyclic graphs where edges represent conditional dependencies. These methods employ statistical inference to determine the most likely network structure given observed expression data, incorporating prior knowledge and handling uncertainty in a principled framework [29]. The mathematical foundation lies in Bayes' theorem: P(G|D) ∝ P(D|G)P(G), where P(G|D) is the posterior probability of the network structure G given data D, P(D|G) is the likelihood of the data given the structure, and P(G) is the prior probability of the structure.

Bayesian networks excel at modeling causal relationships and handling noise through their probabilistic framework. However, they face computational challenges due to the super-exponential growth of possible network structures with increasing numbers of genes. To address this, practical implementations often use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for sampling high-probability networks or employ heuristic search strategies [29]. Advanced Bayesian approaches incorporate interventions (e.g., gene knockouts) as additional constraints and can integrate diverse data types through hierarchical modeling. Comparative studies have shown that Bayesian networks with interventions and inclusion of extra knowledge outperform simple Bayesian networks in both synthetic and real datasets, particularly when considering reconstruction accuracy with respect to edge directions [29]. Recent innovations have combined Bayesian inference with neural networks, using statistical properties to inform network architecture and training procedures [30].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Domains

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Network Reconstruction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Theoretical Basis | Edge Interpretation | Computational Complexity | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Networks | Pearson/Spearman correlation | Co-expression | Low (O(n^2)) | Simple, intuitive, fast computation | Cannot distinguish direct/indirect interactions; limited to linear relationships |

| CLR | Mutual information with Z-score normalization | Statistical dependency with context | Medium (O(n^2)) | Filters spurious correlations; reduces false positives | May miss some non-linear relationships; moderate computational demand |

| ARACNE | Mutual information with Data Processing Inequality | Direct regulatory interaction | High (O(n^3)) | Eliminates indirect edges; detects non-linear relationships | Computationally intensive; assumes negligible loop impact |

| WGCNA | Correlation with scale-free topology | Module co-membership | Medium (O(n^2)) | Identifies functional modules; robust to noise | Primarily for module detection, not direct interactions |

| Bayesian Networks | Conditional probability with Bayesian inference | Causal directional relationship | Very High (O(2^n) worst case) | Models causality; handles uncertainty | Computationally prohibitive for large networks |

Table 2: Empirical Performance on Benchmark Datasets

| Algorithm | Synthetic Dataset Accuracy | Mammalian Network Reconstruction | Noise Tolerance | Experimental Validation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Networks | Moderate (50-60% precision) | Limited for complex mammalian networks | Low | Varies widely (30-50%) |

| CLR | Improved over correlation (60-70%) | Moderate improvement | Medium | 40-60% |

| ARACNE | High (70-80% precision) [26] | Effective for mammalian transcriptional networks [26] | High | 65-80% for transcriptional targets [26] |

| WGCNA | High for module detection | Effective for trait-associated modules | High | 60-75% for functional enrichment |

| Bayesian Networks | High with interventions (75-85%) [29] | Challenging for genome-scale networks | High with proper priors | Limited large-scale validation |

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

ARACNE in Mammalian Transcriptional Networks

ARACNE has demonstrated exceptional performance in reconstructing transcriptional networks in mammalian cells. In a landmark study, the algorithm was applied to microarray data from human B cells, successfully inferring validated transcriptional targets of the cMYC proto-oncogene [26]. The network reconstruction achieved high precision, with experimental validation confirming approximately 70% of predicted interactions. The algorithm's effectiveness stems from its information-theoretic foundation, which enables detection of non-linear relationships that would be missed by correlation-based approaches. For example, ARACNE identified the regulation of CCND1 (Cyclin D1) by E2F1, a relationship characterized by a complex, biphasic pattern that showed no significant correlation in expression but high mutual information [27]. This case illustrates how non-linear dependence measures can capture regulatory relationships that remain hidden to conventional methods.

WGCNA in Disease Biomarker Discovery

WGCNA has proven particularly valuable in identifying disease-associated gene modules and biomarkers. In a comprehensive study of ischemic cardiomyopathy-induced heart failure (ICM-HF), researchers applied WGCNA to gene expression data from myocardial tissues [25]. The analysis identified 35 disease-associated modules, with functional enrichment revealing pathways related to mitochondrial damage and lipid metabolism disorders. By combining WGCNA with machine learning algorithms, the study identified seven potential biomarkers (CHCHD4, TMEM53, ACPP, AASDH, P2RY1, CASP3, and AQP7) with high diagnostic accuracy for ICM-HF [25]. Similarly, in trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC), WGCNA helped identify 35 relevant gene modules, with machine learning integration highlighting nine key feature genes including TFPI, MMP9, and ABCG5 [31]. These studies demonstrate WGCNA's power in distilling complex transcriptomic data into functionally coherent modules with clinical relevance.

Bayesian Methods with Intervention Data

Comparative studies of Bayesian network approaches have revealed the significant advantage of incorporating intervention data and prior knowledge. In a systematic evaluation using synthetic data, real flow cytometry data, and NetBuilder simulations, Bayesian networks modified to account for interventions consistently outperformed simple Bayesian networks [29]. The improvement was particularly pronounced when considering edge direction accuracy, a key metric for causal inference. The hierarchical Bayesian model that allowed inclusion of extra knowledge also showed superior performance, especially when the prior knowledge was reliable. Importantly, the study found that network reconstruction did not deteriorate even when the extra knowledge source was not completely reliable, making Bayesian approaches with informative priors a robust option for network inference [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Framework

To ensure fair comparison across network reconstruction algorithms, researchers should implement a standardized benchmarking protocol incorporating synthetic datasets with known ground truth, biological datasets with partial validation, and quantitative performance metrics. The following workflow represents a comprehensive experimental design for algorithm evaluation:

Network Reconstruction Benchmarking Workflow

Synthetic Data Generation

Synthetic datasets with known network topology provide essential ground truth for quantitative algorithm assessment. For gene regulatory networks, implement dynamic models using Hopf bifurcation dynamics or Hill kinetics to simulate transcription factor-target relationships [26] [32]. Parameters should include varying network sizes (100-10,000 genes), connectivity densities (sparse to dense), and noise levels (signal-to-noise ratios from 0.1 to 10). For the Hopf model, the dynamics for each node can be described by:

dz_j/dt = z_j(α_j + iω_j - |z_j|^2) + Σ_k W_jk z_k + η_j(t)

where z_j represents the complex-valued state of node j, α_j controls the bifurcation parameter, ω_j is the intrinsic frequency, W_jk is the coupling matrix (ground truth connectivity), and η_j(t) is additive noise [32]. This approach generates synthetic expression data with known underlying connectivity for rigorous algorithm testing.

Biological Dataset Curation

Curate biological datasets with partially known validation sets, such as:

- Microarray or RNA-seq data from model organisms with known regulatory interactions (e.g., E. coli, yeast)

- Human cell line data with ChIP-seq validated transcription factor targets

- Tissue-specific expression data with known pathway associations

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and similar repositories provide appropriate datasets. For example, the GSE57345 dataset contains expression profiles from ischemic cardiomyopathy patients and controls, while the GSE42955 dataset serves as a validation set [25]. Preprocessing should include normalization, batch effect correction, and quality control as appropriate for each data type.

Algorithm Implementation Protocols

ARACNE Implementation

The updated ARACNe-AP implementation provides significant computational advantages over the original algorithm. The standard protocol involves:

- Data Preprocessing: Format input data as a matrix with genes as rows and samples as columns. Apply rank transformation to expression values.

- Mutual Information Estimation: Use adaptive partitioning to calculate MI for all transcription factor-target pairs. The adaptive partitioning method recursively divides the expression space into quadrants at means until uniform distribution is achieved or fewer than three data points remain in a quadrant [27].

- Statistical Thresholding: Establish significance threshold for MI values through permutation testing (typically 100 permutations).

- DPI Application: Process all gene triplets to remove the edge with smallest MI when MI(A,C) ≤ min[MI(A,B), MI(B,C)] using a tolerance parameter (typically 0.10-0.15).

- Bootstrap Aggregation: Run multiple bootstraps (typically 100) to build consensus network, retaining edges with significance p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction.

WGCNA Implementation

The standard WGCNA protocol includes:

- Data Preprocessing: Filter genes with low variation, normalize expression data, and detect outliers.

- Soft Thresholding: Select power parameter β that best approximates scale-free topology (R^2 > 0.80-0.90).

- Adjacency Matrix Construction: Compute a_ij = |0.5 + 0.5 × cor(x_i, x_j)|^β for all gene pairs.

- Topological Overlap Matrix: Calculate TOM to measure network interconnectedness: TOM_ij = (Σ_u a_iu a_uj + a_ij) / (min(k_i, k_j) + 1 - a_ij) where k_i = Σ_u a_iu.

- Module Detection: Perform hierarchical clustering with dynamic tree cutting to identify gene modules.

- Module-Trait Association: Correlate module eigengenes with clinical traits or experimental conditions.

For the emerging WGCHNA method, the protocol extends WGCNA by constructing a hypergraph where samples are modeled as hyperedges connecting multiple genes, then calculating a hypergraph Laplacian matrix to generate the topological overlap matrix [28].

Bayesian Network Implementation

For Bayesian network reconstruction, the recommended protocol includes:

- Structure Prior Specification: Incorporate prior knowledge from databases or literature using a confidence-weighted prior.

- Intervention Modeling: Explicitly model experimental interventions (knockdowns, stimulations) as separate conditions.

- Structure Learning: Use constraint-based (PC algorithm) or score-based (BDe score) methods for structure learning.

- Parameter Estimation: Apply Bayesian estimation for conditional probability distributions.

- Model Averaging: Use MCMC methods to sample high-probability networks and average results.

Advanced implementations combine neural networks with Bayesian inference, using the neural network to approximate complex probability distributions while leveraging Bayesian methods for uncertainty quantification [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Data | GEO, ArrayExpress, TCGA | Source of expression profiles | Input data for all network algorithms |

| Algorithm Implementations | ARACNe-AP, WGCNA R package, bnlearn | Algorithm execution | Network reconstruction from data |

| Validation Databases | TRRUST, RegNetwork, STRING | Source of known interactions | Validation of predicted networks |

| Visualization Tools | Cytoscape, Gephi, ggplot2 | Network visualization and exploration | Interpretation of results |

| Enrichment Analysis | clusterProfiler, Enrichr | Functional annotation | Biological interpretation of modules |

| Programming Environments | R, Python, MATLAB | Data analysis environment | Implementation and customization |

Network reconstruction algorithms represent powerful tools for decoding biological complexity from high-dimensional data. Each major algorithm family offers distinct advantages: correlation networks provide simplicity and speed; CLR adds contextual filtering to reduce false positives; ARACNE effectively eliminates indirect interactions using information theory; WGCNA identifies functionally coherent modules; and Bayesian methods model causal relationships with uncertainty quantification. The choice of algorithm depends critically on the biological question, data characteristics, and computational resources. For identifying direct regulatory interactions, ARACNE generally outperforms other methods, while WGCNA excels at module discovery for complex traits. Bayesian approaches offer the strongest theoretical foundation for causal inference but face scalability challenges. Future directions include hybrid approaches that combine strengths from multiple algorithms, methods for single-cell data, and dynamic network modeling for temporal processes. As network biology continues to evolve, these reconstruction algorithms will play an increasingly vital role in translating genomic data into biological insight and therapeutic innovation.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Network Inference Benchmarking

- NetBenchmark: An Overview

- Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking