Autism as a Complex Systems Disorder: Decoding Biological Heterogeneity for Precision Therapeutics

This article synthesizes the latest research reconceptualizing Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as a complex systems disorder, moving beyond a monolithic condition to a convergence of distinct biological subtypes.

Autism as a Complex Systems Disorder: Decoding Biological Heterogeneity for Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest research reconceptualizing Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as a complex systems disorder, moving beyond a monolithic condition to a convergence of distinct biological subtypes. For researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational shift towards data-driven subtyping, methodological advances in computational genomics and neuroscience, the challenges in translating these findings into targeted therapies, and the comparative validation of this new framework against traditional models. The analysis integrates recent breakthroughs, including the identification of four biologically distinct ASD subtypes, novel genetic mechanisms like tandem repeat expansions, and emerging therapeutic targets, providing a roadmap for a new era of precision medicine in autism.

Deconstructing the Monolith: The Biological Subtypes and Genetic Architecture of Autism

The nosology of autism is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a behaviorally-defined unitary spectrum towards a data-driven framework of biologically distinct subtypes. This paradigm shift is propelled by accumulating evidence that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a heterogeneous collection of conditions with diverse genetic underpinnings, developmental trajectories, and neurobiological mechanisms. This whitepaper examines the evolution of autism diagnostic criteria, synthesizes recent breakthroughs in subtype identification, and details the methodological innovations enabling this transition. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances provide a critical foundation for precision medicine approaches in autism research and therapeutic development.

The diagnostic conceptualization of autism has evolved substantially since Leo Kanner's initial description in 1943 [1]. Originally characterized as a form of childhood schizophrenia resulting from psychological factors, autism was first officially recognized as a distinct diagnostic category in the DSM-III (1980) [1] [2]. This edition established autism as a "pervasive developmental disorder" with specific diagnostic criteria, marking a significant departure from previous psychoanalytic interpretations.

The subsequent revision in DSM-IV (1994) further complexified the diagnostic landscape by introducing categorical diagnoses including Asperger's disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, Rett's disorder, and PDD-NOS (Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified) [3]. This proliferation of categories reflected the growing recognition of autism's heterogeneity while maintaining a primarily behavior-based classification system.

A substantial reorganization occurred with DSM-5 (2013), which collapsed previous categorical distinctions into a single umbrella diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [2] [3]. This shift to a spectrum model acknowledged the continuous nature of autistic traits while aiming to improve diagnostic consistency. However, this framework has faced increasing scrutiny due to the extreme heterogeneity within the spectrum and the failure to identify unified biological mechanisms that transcend behavioral observations [4].

The Case for a Paradigm Shift: Limitations of Current Nosology

Scientific and Clinical Limitations

The current spectrum model of autism faces significant challenges that necessitate a paradigm shift in nosology:

Biological Incoherence: Neurobiological research has failed to identify consistent patterns unique to ASD as defined by DSM-5. Genetic studies reveal polygenic, pleiotropic risk factors on a continuum with typical behavior rather than discrete categories [4]. Neuroimaging findings present mixed results with few unique patterns definitively attributable to the diagnosis [4].

Diagnostic Heterogeneity: The DSM-5 ASD diagnosis allows extreme within-category heterogeneity without validated sub-groupings [4]. Attempts to define meaningful subgroups within the spectrum have historically failed, complicating both research and clinical practice.

Lack of Predictive Power: Current diagnostic criteria show limited predictive power regarding developmental trajectories and intervention outcomes [4]. This limitation significantly impacts clinical management and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Frameworks in Psychiatric Nosology

The debate surrounding autism nosology reflects broader philosophical tensions in psychiatric classification:

- Realism posits that psychiatric disorders represent natural kinds with objective existence independent of human observation [4].

- Pragmatism views diagnostic categories as practical tools for organizing interventions and support systems regardless of their correspondence to natural divisions [4].

- Constructivism acknowledges the role of social and cultural factors in shaping diagnostic concepts while not entirely abandoning biological realism [4].

Kendler's "limited realism" suggests that a diagnosis is "real to the degree that it coheres well with what we know empirically and feel comfortable about" [4]. By this standard, ASD as currently defined falls short, as genetic, neurobiological, and behavioral findings fail to present a coherent picture of a unified entity [4].

Breakthrough Research: Data-Driven Subtype Identification

The Princeton-Simons Foundation Study

A landmark 2025 study from Princeton University and the Simons Foundation has marked a transformative step in autism nosology by identifying four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism through analysis of data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK autism cohort [5]. The research employed a person-centered computational approach that analyzed over 230 traits per individual across social interactions, repetitive behaviors, and developmental milestones [5].

Table 1: Clinically Distinct Subtypes of Autism Identified in Recent Research

| Subtype Name | Prevalence | Clinical Presentation | Developmental Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Core autism traits with co-occurring conditions (ADHD, anxiety, depression) | Typical developmental milestone attainment |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Developmental delays in walking/talking, variable repetitive behaviors and social challenges | Later achievement of developmental milestones |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder expression of core autism behaviors, fewer co-occurring conditions | Typical developmental milestone attainment |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe, wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays, social-communication difficulties, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions | Significant developmental delays across multiple domains |

Genetic Architecture of Autism Subtypes

Critically, each identified subtype demonstrates distinct genetic profiles:

- The Broadly Affected subgroup shows the highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations (those not inherited from parents) [5].

- The Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay group is more likely to carry rare inherited genetic variants [5].

- The Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype exhibits mutations in genes that become active later in childhood, suggesting post-natal biological mechanisms [5].

These findings indicate that superficially similar clinical presentations (e.g., developmental delays across subtypes) may have distinct genetic underpinnings, explaining why previous genetic studies searching for unified "autism genes" have largely fallen short [5].

Methodological Innovations: Enabling the Subtype Revolution

Person-Centered Computational Approach

The identification of biologically meaningful subtypes required moving beyond traditional analysis methods that examined single traits in isolation. Key methodological advances include:

- High-Dimensional Phenotyping: Comprehensive assessment of 230+ clinical and behavioral traits across multiple domains [5].

- Computational Modeling: Advanced machine learning algorithms to identify natural groupings across multidimensional data [5].

- Data Integration: Simultaneous analysis of genetic and clinical data to establish biologically-grounded classifications [5].

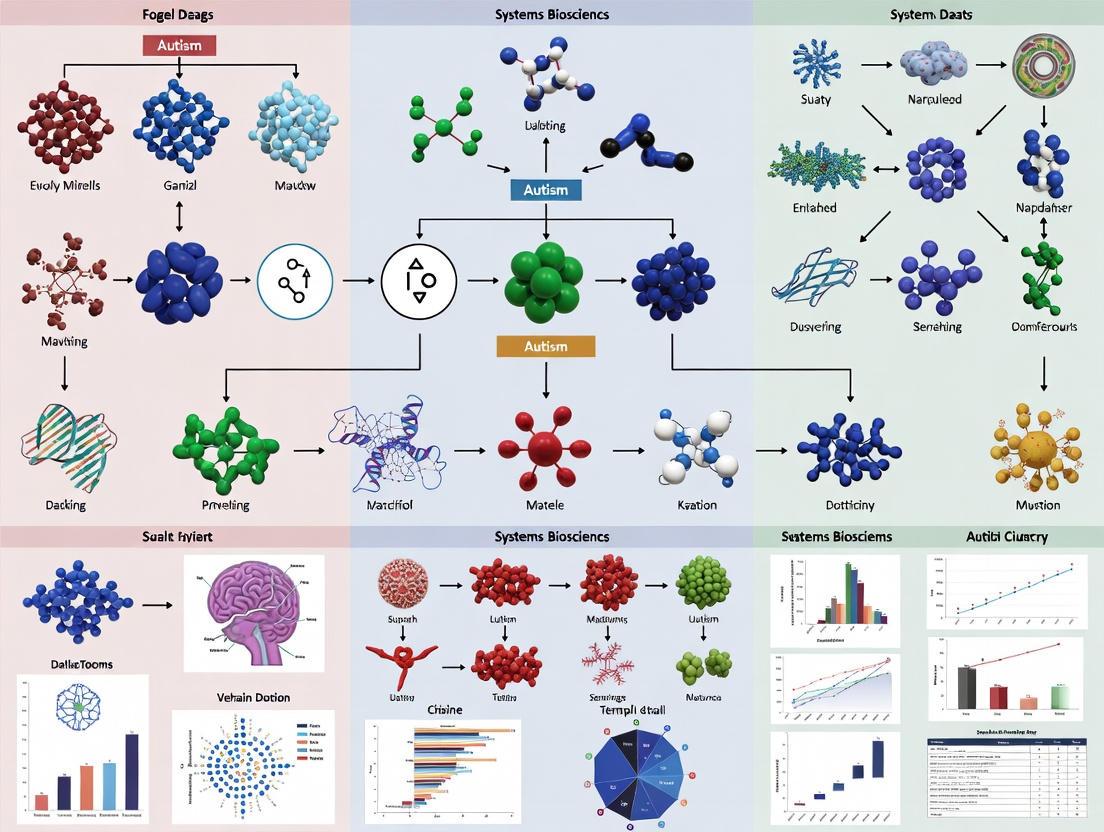

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive analytical process:

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Autism Subtype Investigation

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort Resources | SPARK cohort, Simons Simplex Collection | Large-scale participant data with deep phenotyping and genetic information |

| Genomic Tools | Whole exome sequencing, polygenic risk score analysis, gene expression profiling | Identification of genetic variants, inheritance patterns, and functional pathways |

| Computational Methods | Machine learning clustering algorithms, multidimensional scaling, factor analysis | Data-driven subtype identification from high-dimensional datasets |

| Clinical Assessment | ADOS-2, ADI-R, developmental history, psychiatric comorbidity measures | Standardized phenotyping across behavioral and clinical domains |

| Neurobiological Tools | fMRI (including sleeping-state fMRI), EEG, brain complexity measures (Sample Entropy, Transfer Entropy) | Investigation of neural structure, function, and connectivity differences |

Experimental Protocol: Subtype Identification Workflow

For researchers seeking to replicate or extend subtype identification, the following detailed methodology provides a framework:

Step 1: Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

- Recruit a minimum of 2,000 participants to ensure sufficient power for subtype detection

- Collect comprehensive phenotypic data across 200+ traits including social communication, repetitive behaviors, developmental milestones, medical history, and psychiatric comorbidities

- Obtain genetic material for whole genome or exome sequencing

- Secure informed consent following institutional review board protocols

Step 2: Data Integration and Cleaning

- Harmonize data across collection sites using standardized scoring procedures

- Implement quality control measures for genetic data including variant calling standardization

- Address missing data using appropriate imputation methods

- Create unified database linking phenotypic and genetic information

Step 3: Computational Modeling and Subtype Identification

- Apply multiple clustering algorithms (k-means, hierarchical clustering, Gaussian mixture models) to identify robust subgroups

- Validate cluster stability through bootstrapping and cross-validation techniques

- Determine optimal number of clusters using statistical indices (e.g., silhouette score, Bayesian information criterion)

- Characterize resulting subtypes based on distinctive feature profiles

Step 4: Genetic Validation

- Compare genetic variant burden across identified subtypes

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis to identify distinct biological processes

- Examine differences in inherited versus de novo variation patterns

- Assess polygenic risk scores for psychiatric conditions across subtypes

Step 5: Clinical Validation

- Examine developmental trajectories across subtypes using longitudinal data

- Compare treatment responses and outcomes across subgroups

- Assess comorbidity patterns and medical correlates

- Validate subtypes in independent cohorts to ensure generalizability

Neurobiological Underpinnings of Autism Subtypes

Brain Complexity and Connectivity

Emerging research reveals distinct neurobiological differences associated with autism presentations. A 2025 sleeping-state functional MRI study investigated brain complexity in children with ASD compared to typically developing children, employing sample entropy (SampEn) and transfer entropy (TE) analyses [6]. Findings indicated that children with ASD showed significantly increased SampEn in the right inferior frontal gyrus, suggesting aberrant randomness in local brain activity [6].

Furthermore, investigation of information flow between brain regions revealed that the typically developing group exhibited 13 pairs of brain regions with higher TE compared to the ASD group, while the ASD group showed 5 pairs of brain regions with higher TE than controls [6]. These findings demonstrate anomalous information transmission between brain regions in ASD, providing potential biomarkers for distinguishing neurobiological subtypes.

Differential Genetic Pathways and Timing Effects

The identification of autism subtypes has revealed distinct biological narratives rather than a single unified story [5]. Crucially, genetic impacts appear to operate on different developmental timelines across subtypes:

- For the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype, mutations occur in genes that become active later in childhood, suggesting post-natal biological mechanisms [5].

- The Broadly Affected subgroup shows strongest genetic signals in genes active during early neurodevelopment [5].

- Distinct biological pathways are affected in each subtype, explaining differential clinical presentations and outcomes [5].

The following diagram illustrates the distinct genetic and biological pathways underlying autism subtypes:

Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

Impact on Clinical Trials and Drug Development

The recognition of biologically distinct autism subtypes has profound implications for therapeutic development:

- Stratified Clinical Trials: Future clinical trials must recruit based on biological subtypes rather than behavioral diagnoses alone to detect meaningful treatment effects.

- Targeted Interventions: Therapies can be developed to address specific pathway disruptions in each subtype rather than employing one-size-fits-all approaches.

- Biomarker Development: Subtype-specific biomarkers will enable earlier identification and intervention matching.

- Outcome Measurement: Clinical trials must incorporate subtype-appropriate outcome measures that reflect the distinct challenges of each subgroup.

Future Research Directions

This paradigm shift opens several critical research avenues:

- Expanding Subtype Classification: Current findings of four subtypes represent a starting point rather than a final taxonomy [5]. Further refinement is expected as sample sizes increase and analytical methods improve.

- Longitudinal Validation: Tracking subtype trajectories across the lifespan will provide crucial insights into developmental courses and intervention timing.

- Mechanistic Studies: Detailed investigation of subtype-specific biological pathways will identify novel therapeutic targets.

- Global Representation: Ensuring diverse population representation in subtype research to avoid biases inherent in current predominantly Western cohorts [4].

The identification of biologically distinct autism subtypes represents a fundamental paradigm shift from behaviorally-defined spectra to data-driven nosology. This transformation, enabled by advanced computational approaches integrating multidimensional data, provides a framework for realizing precision medicine in autism research and clinical care. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances offer the potential to develop targeted interventions based on underlying biological mechanisms rather than surface-level behavioral similarities. As this field rapidly evolves, embracing this new nosological framework will be essential for advancing both scientific understanding and clinical outcomes for autistic individuals.

Recent large-scale, person-centered computational analyses have revolutionized the understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) by decomposing its profound phenotypic heterogeneity into biologically meaningful subtypes [5] [7]. This whitepaper synthesizes a landmark study that integrated deep phenotypic and genotypic data from over 5,000 individuals within the SPARK cohort to define four clinically and biologically distinct ASD subtypes [5]. Framed within the context of autism as a complex systems disorder, this work demonstrates that the spectrum is composed of multiple discrete "puzzles," each with unique genetic architectures, developmental trajectories, and altered neurobiological pathways [5] [8]. The identification of these subtypes—Social and Behavioral Challenges, Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay, Moderate Challenges, and Broadly Affected—provides a foundational data-driven framework for precision medicine, offering new avenues for targeted diagnostics, mechanistic research, and therapeutic development [5] [7].

Autism Spectrum Disorder is a quintessential complex systems disorder, characterized by emergent properties arising from dynamic interactions across genetic, neural circuit, and behavioral levels [8]. Traditional diagnostic approaches, focusing on a unitary set of core social and repetitive behaviors, have failed to capture this systemic complexity, leading to inconsistent genetic associations and limited progress in targeted interventions [5]. The inherent heterogeneity suggests not a single continuum but a multiplicity of distinct neurodevelopmental pathways converging on a similar phenotypic landscape [7]. This perspective necessitates a shift from a trait-centered to a person-centered analytical paradigm, which considers the full spectrum of over 230 clinical traits per individual to model the system as a whole [5]. The following sections detail a transformative study that applied this complex systems lens, leveraging large-scale data integration and machine learning to identify robust subtypes, thereby mapping distinct biological narratives onto the clinical heterogeneity of ASD [5] [7].

Experimental Protocols & Computational Methodology

Cohort and Data Acquisition

The research utilized data from the SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research) cohort, the largest study of autism to date, which includes genetic and deep phenotypic data from over 150,000 individuals with autism and family members [7]. For this analysis, phenotypic and genotypic data from more than 5,000 participants with autism, aged 4–18, were analyzed [7]. The phenotypic data encompassed a broad range of over 230 traits, including social interaction challenges, repetitive behaviors, developmental milestones (e.g., age of walking, talking), co-occurring psychiatric conditions (ADHD, anxiety, depression), and medical histories [5]. Genetic data included whole-exome or genome sequencing to identify inherited and de novo variants [5].

Computational Subtyping Algorithm

The core methodology employed a person-centered, data-driven approach using general finite mixture modeling [7].

- Model Selection: Instead of examining single traits in isolation (trait-centered), the model considered the complete phenotypic profile of each individual. Finite mixture modeling was chosen for its unique ability to handle heterogeneous data types (binary yes/no, categorical, continuous) within a single probabilistic framework [7].

- Integration and Clustering: The model integrated the diverse phenotypic measures to calculate a probability for each individual belonging to a latent class or subtype. This allowed individuals to be grouped based on shared multidimensional phenotypic profiles [5] [7].

- Validation and Genetic Correlation: The subtypes derived purely from phenotypic data were subsequently analyzed for enrichment of specific genetic variants (e.g., damaging de novo mutations, rare inherited variants) and distinct biological pathways using gene set enrichment and functional genomics analyses [5].

Supplementary Neuroimaging Protocol (Example of Complexity Analysis)

Complementary to genetic discovery, investigating the systems-level neurobiology of ASD involves protocols like sleep-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (ss-fMRI) to assess brain complexity, as exemplified in related research [9].

- Participant Preparation: Children (e.g., aged 12-36 months) undergo adaptive training to acclimate to the MRI environment. Scanning is performed during natural sleep without sedation, a sensitive state for detecting neurodevelopmental anomalies [9].

- Data Acquisition: MRI datasets are acquired using a 3.0T scanner with a multi-channel head coil. High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images and resting-state (sleep-state) fMRI sequences (e.g., TR/TE=2000/30 ms, voxel size=3x3x3 mm³) are collected [9].

- Complexity Analysis: Brain complexity is quantified using metrics like Sample Entropy (SampEn) to assess local signal randomness and Transfer Entropy (TE) to measure directed information flow between brain regions, capturing both aberrant local activity and anomalous network communication [9].

Diagram Title: Data-Driven ASD Subtyping Workflow

Results: The Four Subtypes and Their Quantitative Profiles

The finite mixture model robustly identified four subtypes, each with a distinct clinical profile and genetic signature. The quantitative characteristics are summarized below.

Table 1: Clinical and Demographic Profiles of ASD Subtypes

| Subtype | Approximate Prevalence | Core Clinical Presentation | Developmental Milestones | Common Co-occurring Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social & Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Pronounced social challenges and repetitive behaviors. | Typically on pace with children without autism. | High rates of ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, mood dysregulation [5] [7]. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Mixed presentation of social/repetitive behaviors with developmental delay. | Delays in milestones (e.g., walking, talking). | Generally absent of anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors [5] [7]. |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Core autism behaviors present but less severe. | Typically on pace. | Generally absent of co-occurring psychiatric conditions [5] [7]. |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe and wide-ranging challenges across all domains. | Significant developmental delays. | High rates of anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation, intellectual disability [5] [7]. |

Table 2: Distinct Genetic and Biological Characteristics

| Subtype | Key Genetic Findings | Implicated Biological Pathways (Examples) | Timing of Genetic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social & Behavioral Challenges | Not specified as having highest burden of de novo mutations. | Neuronal action potential, synaptic signaling. | Genes active postnatally, aligning with later diagnosis [5] [7]. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | Enriched for rare inherited genetic variants [5]. | Chromatin organization, transcriptional regulation. | Genes active prenatally [5] [7]. |

| Moderate Challenges | Genetic profile less extreme than other groups. | Pathways distinct from other classes (specifics not detailed). | Not specified. |

| Broadly Affected | Highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations [5]. | Multiple pathways involved in severe neurodevelopmental disruption. | Likely prenatal and early postnatal. |

Biological Mechanisms: Signaling Pathways and Systems Dysregulation

The subtypes are driven by divergent biological narratives. Pathway analysis revealed minimal overlap between subtypes, with each linked to specific, previously implicated but now subclass-distinct mechanisms [7].

- Neuronal Signaling & Synaptic Function: Particularly relevant to the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype, pathways involving neuronal excitability, action potentials, and synaptic transmission are disrupted [7] [8]. This aligns with postnatally active genes and may relate to findings of altered brain complexity, such as increased local entropy in frontal regions [9].

- Chromatin Remodeling & Transcriptional Regulation: This mechanism is prominently associated with the Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay subtype, enriched for inherited variants affecting genes active during prenatal development [5] [7]. Dysregulation here impacts broad neurodevelopmental programs.

- Integrated Systems View: ASD pathophysiology can be visualized as the convergence of multiple risk pathways onto final common circuits, such as the mTOR signaling pathway (integrating genetic, synaptic, and metabolic inputs) or immune-inflammatory responses, which may modulate severity across subtypes [8].

Diagram Title: Biological Pathways Converge on ASD Subtypes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for ASD Subtype & Mechanisms Research

| Item | Function / Application | Relevance to Featured Research |

|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Data | Large-scale, integrated repository of genotypic and deep phenotypic data from individuals with ASD. | Foundational resource for person-centered computational subtyping and genetic correlation studies [5] [7]. |

| General Finite Mixture Modeling Software | Computational framework for clustering heterogeneous data types (R packages, Python libraries). | Core algorithm for identifying latent subtypes from multidimensional phenotypic vectors [7]. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Reagents for high-throughput sequencing of coding and non-coding genomic regions. | Essential for identifying de novo and rare inherited variants associated with specific subtypes [5]. |

| Sleep-state fMRI Protocol | Tailored MRI sequences and participant acclimation procedures for scanning sleeping infants/children. | Enables study of early brain development and complexity (SampEn, TE) in naturalistic states, critical for understanding neural systems pathology [9]. |

| Pathway Enrichment Analysis Tools | Software (e.g., GSEA, Ingenuity) and curated gene-set databases. | For translating genetic hit lists from each subtype into distinct biological pathways and processes [5] [7]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Differentiation Kits | Reagents to derive neuron/glia from patient fibroblasts, specific to a subtype's genetic background. | Enables in vitro modeling of subtype-specific cellular and molecular pathophysiology [8]. |

| Animal Models with Subtype-Relevant Mutations | Genetically engineered mice or organoids carrying human variant homologs. | For testing causal mechanisms and potential therapeutics within a defined biological narrative [8]. |

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) presents a profound genetic paradox. Despite high heritability estimates, no single genetic locus accounts for more than a fraction of cases, pointing to a complex architecture involving multiple genetic factors operating across different biological scales. The emerging "multi-hit" model resolves this paradox by proposing that ASD risk emerges from combinatorial effects of rare and common genetic variants that collectively disrupt neurodevelopmental processes. This framework represents a fundamental shift from single-gene determinism to a systems-level understanding where autism manifests through interactions between various genetic "hits" that converge on critical biological pathways and networks.

Groundbreaking research published in 2023 analyzing the largest whole-genome sequencing cohort of multiplex families to date provides compelling evidence for this model, demonstrating that autistic children from these families "demonstrate an increased burden of rare inherited protein-truncating variants in known ASD risk genes" and that "ASD polygenic score (PGS) is overtransmitted from nonautistic parents to autistic children who also harbor rare inherited variants, consistent with combinatorial effects in the offspring" [10]. These findings establish a concrete genetic foundation for understanding autism as a complex systems disorder wherein the total mutational burden and its interaction with polygenic background determine phenotypic outcomes.

Genetic Architecture of Autism: Deconstructing the Multi-Hit Framework

Variant Classes in Autism Risk

The multi-hit model integrates three principal classes of genetic variation that contribute to ASD susceptibility through distinct mechanisms and effect sizes [11]:

Table 1: Genetic Variant Classes in Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Variant Class | Population Frequency | Effect Size | Heritability Contribution | Transmission Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare De Novo | <1% | Large (OR > 10) | 15-20% | Not inherited; spontaneous |

| Rare Inherited | 1-5% | Moderate (OR 2-5) | ~10-15% | Familial transmission |

| Common Variants | >5% | Small (OR <1.2) | ~50% | Polygenic inheritance |

This integrated model explains key aspects of autism inheritance that were previously puzzling, particularly why "autism tends to run in families" despite the strong association with de novo mutations [11]. The multi-hit framework posits that in multiplex families, inherited rare variants combine with a favorable polygenic background to reach the threshold for autism manifestation, whereas in simplex families, large-effect de novo mutations may be sufficient to cross this threshold independently.

Evidence for Combinatorial Effects

The 2023 whole-genome sequencing study of 4,551 individuals from 1,004 multiplex families provides robust evidence for interactive effects between different variant classes. The research identified "seven previously unrecognized ASD risk genes supported by a majority of rare inherited variants," finding support for a total of 74 genes in their cohort and 152 genes after combined analysis with other studies [10]. Crucially, the study demonstrated that common ASD genetic risk is "overtransmitted from nonautistic parents to autistic children with rare inherited variants," explaining the "reduced penetrance of these rare variants in parents" [10]. This combinatorial risk architecture follows an additive threshold model where the total genetic burden determines phenotypic expression.

Further supporting this model, researchers have found that "people who have both a large spontaneous mutation linked to autism as well as a rare, inherited harmful mutation are more affected than those who carry only the former" [11]. This gene-gene interaction (epistasis) exemplifies the multi-hit principle where the combined effect of multiple variants exceeds the sum of their individual effects, creating emergent properties through nonlinear dynamics characteristic of complex systems.

Diagram 1: Multi-Hit Threshold Model of Autism Genetic Risk. This diagram illustrates how different classes of genetic variants combine additively and interactively to exceed the threshold for ASD diagnosis. Rare de novo variants (red), rare inherited variants (yellow), and common polygenic risk (blue) collectively contribute to total genetic liability, with combinatorial effects (dashed lines) potentially creating non-additive impacts that push total risk above the diagnostic threshold.

Methodological Framework: Experimental Approaches for Elucidating Multi-Hit Architecture

Whole-Genome Sequencing in Multiplex Families

The 2023 PNAS study established a comprehensive methodological pipeline for investigating multi-hit genetics in ASD [10]. The research utilized the largest whole-genome sequencing cohort of multiplex families to date, consisting of 1,004 families with two or more autistic children, amplifying the signal of inherited risk factors often obscured in simplex families. The experimental workflow encompassed:

Sample Collection and Processing: The study sequenced 4,551 individuals from the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange (AGRE) at mean coverage >30× with 80.6% of bases covered at ≥30×, ensuring high-quality variant detection. Participants included 1,836 autistic children and 418 nonautistic children with both biological parents sequenced (fully-phaseable trios) to enable transmission pattern analysis [10].

Variant Calling and Annotation: The pipeline employed an Artifact Removal by Classifier (ARC) to distinguish true rare de novo variants from sequencing errors or artifacts from lymphoblastoid culture. This quality control step was crucial for reducing false positives in variant detection. Variants were categorized as:

- Rare de novo variants (RDNVs)

- Rare inherited protein-truncating variants (PTVs)

- Rare inherited missense variants

- Common variants for polygenic risk scoring

Burden Analysis: The researchers compared variant rates between autistic and nonautistic children using logistic regression, examining different functional classes (PTVs, missense variants) and genomic contexts (highly constrained genes with pLI ≥ 0.9 or LOEUF < 0.35) [10].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Multi-Hit Genetic Analysis. This diagram outlines the comprehensive pipeline used in recent large-scale studies to identify and integrate different classes of genetic risk variants for ASD, from sample collection through multi-hit integration analysis.

Polygenic Risk Scoring Methodologies

The calculation of polygenic risk scores (PGS) represents a critical methodological component for quantifying common variant contribution. The 2023 study computed ASD PGS for participants of European ancestry, representing "the weighted sum of their common variants tied to autism" [12]. The technical approach involved:

Reference GWAS Data: Utilizing the largest available genome-wide association study summary statistics for ASD to define effect sizes (beta coefficients) for common variants across the genome.

PGS Calculation: Implementing standardized PGS software such as PRSice-2 or PRS-CS to calculate individual risk scores based on genotype data [13]. These tools apply clumping and thresholding or Bayesian shrinkage methods to optimize predictive accuracy.

Overtransmission Analysis: Testing whether PGS was significantly overtransmitted from parents to autistic children using linear mixed models that account for familial relatedness, with specific focus on children carrying rare inherited variants [10].

Recent methodological advances enable more sophisticated rare variant polygenic risk scores (rvPRS). A 2025 study in Communications Biology established that "single-SNP-based rvPRS outperform gene-burden models, and imputed genotype-derived rvPRS generally surpass WES-derived models," providing an optimized protocol for rare variant risk quantification [13]. For six of twelve validated traits, "combined tPRS (cvPRS + rvPRS) improves prediction over cvPRS alone," demonstrating the value of integrated risk models [13].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Hit Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application in ASD Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina Whole-Genome Sequencing | High-coverage variant discovery | Identifies rare de novo and inherited variants [10] |

| Variant Callers | GATK, Platypus | SNP/indel detection | Standardized variant calling across cohorts |

| Quality Control | Artifact Removal by Classifier (ARC) | Filters technical artifacts | Distinguishes true RDNVs from sequencing errors [10] |

| Gene Constraint Metrics | pLI, LOEUF | Quantifies gene tolerance to variation | Prioritizes variants in constrained genes [10] |

| PGS Software | PRSice-2, PRS-CS | Polygenic risk score calculation | Quantifies common variant burden [13] |

| Statistical Packages | R, PLINK, GCTA | Genetic association testing | Burden analysis, heritability estimation [10] [13] |

| Functional Annotation | ANNOVAR, VEP | Variant functional prediction | Prioritizes deleterious missense/PTV variants |

Key Findings: Empirical Support for the Multi-Hit Model

Genetic Evidence from Multiplex Families

The analysis of multiplex families has yielded particularly compelling evidence for the multi-hit model. The 2023 study revealed that:

Table 3: Key Genetic Findings from Multiplex Family Studies

| Finding Category | Specific Result | Statistical Evidence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Gene Discovery | 7 previously unrecognized ASD risk genes | FDR < 0.1 | Genes primarily supported by rare inherited variants [10] |

| Rare Inherited Burden | Increased PTV burden in ASD risk genes | P < 0.05 (specific values not reported) | Confirms contribution of inherited rare variation [10] |

| PGS Overtransmission | Higher PGS in autistic children with rare inherited variants | Significant overtransmission (P < 0.05) | Common variants compound rare variant effects [10] [12] |

| Language Association | PGS associated with social dysfunction and language delay | Significant association (P < 0.05) | Suggests language as core biological feature [10] |

| De Novo Depletion | Reduced RDNV burden in multiplex vs simplex families | Significant depletion (P < 0.05) | Different genetic architecture in multiplex families [10] |

These findings collectively demonstrate that "autism's heritability in families stems from a combination of both common and rare inherited variants that team up to hit a threshold in some people" [12]. The evidence supports an "additive complex genetic risk architecture of ASD involving rare and common variation" [10] that operates differently across family types.

Phenotypic Correlations and Clinical Implications

Beyond genetic risk quantification, the multi-hit model provides explanatory power for understanding phenotypic heterogeneity in ASD. The 2023 study made the crucial observation that "in addition to social dysfunction, language delay is associated with ASD PGS overtransmission" [10]. This finding has significant clinical implications as it suggests that "language is a core biological feature of ASD," despite not being a core clinical criterion in current diagnostic frameworks [10].

The multi-hit model also explains variability in expressivity among carriers of the same rare variant. For example, "only about 20 percent of people with a mutation in 16p11.2 — among the strongest risk factors for autism — have the condition; all have some combination of other traits, such as developmental delay, obesity and language problems" [11]. This variability likely depends on "the rest of a person's genetic background," [11] consistent with modifier effects from common polygenic risk.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, key challenges remain in fully elucidating autism's multi-hit architecture. Current studies are limited by:

Ancestral Diversity: Most large-scale genetic studies have focused primarily on European ancestry populations, limiting generalizability of polygenic risk scores across ancestries.

Non-Coding Variation: The role of regulatory variants in multi-hit models remains underexplored, though the 2023 study began investigating "noncoding regions of the genome" [10].

Functional Validation: While statistical genetic evidence is accumulating, functional validation of multi-hit interactions in model systems represents a critical next step.

Future research directions should include:

- Expanded whole-genome sequencing in diverse ancestral populations

- Development of multi-ancestry polygenic risk scores

- Functional studies of gene-gene interactions in neurodevelopment

- Integration of epigenetic and transcriptomic data to understand mechanistic pathways

- Prospective studies of genetic risk accumulation across development

The multi-hit model continues to evolve as empirical evidence accumulates, offering an increasingly sophisticated framework for understanding autism's complex etiology and guiding therapeutic development toward pathway-based interventions rather than gene-specific approaches.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a paradigm of neurodevelopmental complexity, where clinical heterogeneity reflects multifaceted biological underpinnings. Framing autism as a complex systems disorder necessitates understanding how distinct genetic perturbations converge onto shared molecular pathways. Emerging evidence positions tandem repeat expansions (TREs) and their disruption of RNA splicing as a critical mechanism contributing to this complexity [14] [15]. These repetitive DNA sequences, comprising 2-20 base pair motifs repeated in tandem, demonstrate extensive polymorphism in the human genome, with over 37,000 motifs identified across nearly 32,000 distinct genomic regions [14]. Their expansion beyond normal thresholds introduces system-wide perturbations, particularly through disrupting the precise regulation of alternative splicing essential for neurodevelopment. This whitepaper examines how TREs constitute a previously underappreciated source of genetic variation in ASD, operating through mechanisms that align with complex systems principles—where small, recurrent genetic variations at multiple loci produce emergent effects on neural circuitry and clinical presentation.

Quantitative Evidence: Tandem Repeat Expansions in Autism

Genome-Wide Burden and Prevalence

Large-scale genomic studies have quantified the significant contribution of tandem repeat expansions to autism etiology. A landmark study analyzing 17,231 genomes revealed that rare tandem repeat expansions in gene-associated regions demonstrate a statistically significant increased prevalence in individuals with autism (23.3%) compared to unaffected siblings (20.7%), suggesting a collective contribution to autism risk of approximately 2.6% [14]. The research identified 2,588 loci where rare TREs were significantly more prevalent in autism-affected individuals than population controls, with these expansions particularly enriched in exonic regions, near splice junctions, and in genes related to nervous system development [14].

Table 1: Prevalence of Tandem Repeat Expansions in Autism Studies

| Study Population | Sample Size | TRE Prevalence in ASD | TRE Prevalence in Controls | Contribution to ASD Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSSNG/SSC Cohorts | 17,231 genomes | 23.3% (affected children) | 20.7% (unaffected siblings) | ~2.6% [14] |

| Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1) | N/A | ~14% (in DM1 population) | ~1% (general population) | 14-fold increased risk [15] |

Genomic Distribution and Characteristics

Tandem repeats demonstrate non-random distribution throughout the genome, with distinctive patterns relevant to their functional impact:

- Motif Size Distribution: The majority (72.2%) of repeat tracts have motifs <7 bp, with 2 bp motifs being most common (27.7%) [14]. Even-numbered motif sizes (2, 4, 6 bp) significantly outnumber odd-numbered sizes (3, 5 bp) in smaller size ranges [14].

- Sequence Composition: Motifs are predominantly (>40%) AC- or AG-rich, with only 0.4% composed exclusively of C or G nucleotides [14].

- Genomic Location: TREs are enriched in GC-rich regions and fragile sites but depleted within conserved DNA sequences and 3' untranslated regions [14]. They correlate strongly with cytogenetic fragile sites, co-localizing with 9 of 11 (81.8%) molecularly mapped rare folate-sensitive fragile sites [14].

Table 2: Characteristics of Tandem Repeats in the Human Genome

| Characteristic | Pattern/Observation | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Motif Size | 72.2% <7 bp; 2 bp most common (27.7%) | Influences detectability and expansion potential |

| Sequence Bias | >40% AC- or AG-rich; only 0.4% C- or G-only | Affects DNA structure and protein binding properties |

| Genomic Distribution | Enriched in fragile sites (OR=1.12; p=1.2×10⁻⁴) | Links to genome instability regions |

| Gene Region Enrichment | Upstream (OR=1.33) and 5' UTR (OR=1.2) regions | Potential impact on gene regulation |

| Exonic Depletion | Reduced in exons (OR=0.61) and 3' UTR (OR=0.43) | Suggests selective pressure against coding expansions |

Molecular Mechanisms: From Genetic Expansion to Splicing Disruption

RNA Toxicity and Protein Sequestration

The molecular pathway linking TREs to autism pathogenesis involves a toxic RNA mechanism that disrupts normal splicing regulation. Research connecting myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) and autism has revealed that expanded repeats in the DMPK gene produce "toxic RNA" that binds to and sequesters RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), particularly muscleblind-like (MBNL) proteins [15]. This sequestration creates a functional protein deficiency, preventing these splicing regulators from performing their normal functions in processing other RNA transcripts. The resulting imbalance affects multiple genes involved in brain development and function, ultimately contributing to autistic symptoms [15]. This mechanism represents a systems-level disruption where a single genetic variation produces cascading effects across the transcriptome.

Splicing Regulation in Neurodevelopment

Alternative splicing is particularly critical in the nervous system, where it generates exceptional proteomic diversity necessary for proper neural development and function. RNA-binding proteins including PTBP, RBFOX, and FMRP (fragile X mental retardation protein) are essential for neurogenesis, axon guidance, synapse formation, and synaptic plasticity [16]. The regulation of splicing involves a complex network of RBP interactions, where proteins such as serine-/arginine-rich (SR) proteins generally promote exon inclusion, while heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) typically inhibit exon inclusion [16]. When TREs disrupt this finely balanced system, the consequences are particularly severe in neural tissue, where splicing diversity is highest.

Figure 1: Molecular Pathway from Tandem Repeat Expansions to ASD Symptoms

Autism Subtypes and Genetic Heterogeneity

Biologically Distinct Subtypes

Recent research has identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism, each with different genetic profiles and developmental trajectories [5] [17]. This stratification helps explain the heterogeneous relationship between TREs and clinical presentation:

- Social and Behavioral Challenges Subtype (37% of participants): Characterized by core autism traits without developmental delays, and frequent co-occurring conditions like ADHD, anxiety, and depression [5].

- Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%): Features developmental delays but generally absence of anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors [5].

- Moderate Challenges (34%): Milder core autism behaviors with typical developmental milestone achievement [5].

- Broadly Affected (10%): Severe, wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays, social-communication difficulties, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions [5].

Genetic Correlates of Subtypes

These subtypes demonstrate distinct genetic patterns relevant to TRE mechanisms. The Broadly Affected subtype shows the highest burden of damaging de novo mutations, while the Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay group is more likely to carry rare inherited variants [5]. Importantly, the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype—which typically has substantial social and psychiatric challenges but no developmental delays—involves mutations in genes that become active later in childhood, suggesting the biological mechanisms may emerge postnatally [5]. This temporal dimension aligns with how TRE effects might manifest at different developmental timepoints.

Experimental and Diagnostic Approaches

Detection Methodologies

Advancements in detecting tandem repeat expansions have been crucial to understanding their role in autism. The following table summarizes key methodological approaches:

Table 3: Diagnostic and Research Methods for Tandem Repeat Expansion Detection

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ExpansionHunter Denovo (EHdn) [14] | Computational algorithm detecting repeats from short-read sequencing | Works irrespective of prior knowledge; detects 2-20 bp motifs | Limited by read length for very large expansions |

| Repeat-Primed PCR (RP-PCR) [18] | PCR with primers binding repetitive sequences | Highly sensitive for detecting expansions | Does not provide precise sizing |

| Southern Blotting [18] | DNA fragment hybridization | Gold standard for large expansions; provides sizing | Time-consuming; requires large DNA samples |

| Long-Read Sequencing [18] | Sequencing long DNA fragments | Accurate for large, complex repeats; can detect methylation | Higher cost; limited accessibility |

| Nanopore Cas9-Targeted Sequencing [18] | Cas9-assisted targeted sequencing | Precise, targeted analysis; cost-effective for specific regions | Complex setup; specialized equipment |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Tandem Repeat and Splicing Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ExpansionHunter Denovo [14] | Genome-wide TRE detection from short-read data | Detects motifs of 2-20 bp without prior knowledge |

| SPARK Cohort Data [5] [17] | Large-scale genetic and phenotypic data | 50,000+ families; genetic data with detailed trait information |

| RNA-Binding Protein Databases [16] | Cataloguing RBP-binding sites | Identifies potential protein targets of toxic RNA |

| Repeat-Primed PCR Assays [18] | Screening for specific repeat expansions | Sensitive detection of expanded alleles |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) [18] [19] | Experimental therapeutic approach | Target specific RNA sequences to modulate splicing |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for TRE Detection and Validation

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

RNA-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

The mechanistic understanding of TRE-mediated splicing disruption has enabled development of targeted therapeutic approaches:

- Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): These synthetic nucleic acid strands can bind to expanded repeat RNAs, blocking their toxic interactions with RBPs or triggering degradation pathways [18] [19]. ASOs have demonstrated success through mechanisms like allele-specific knockdown and splice modulation [18].

- Small Molecule Interventions: Research has identified small molecules that selectively bind structured RNA repeats, potentially stimulating their decay via endogenous pathways like the exosome complex [20]. In Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy, one such molecule facilitates intron excision and degradation of the toxic repeat-containing RNA [20].

- Gene Editing Technologies: Emerging CRISPR-Cas systems offer potential for directly correcting repeat expansions at the DNA level, though this approach remains primarily investigational [18].

Precision Medicine Approaches

The identification of autism subtypes with distinct genetic profiles enables more targeted therapeutic development [5] [17]. For instance, individuals in the Broadly Affected subtype, with their high burden of de novo mutations, might benefit from different intervention strategies than those in the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype, where mutations affect genes active later in childhood [5]. This stratification moves the field toward personalized approaches based on an individual's specific genetic and biological subtype.

Tandem repeat expansions and their disruption of RNA splicing represent a significant genetic mechanism in autism spectrum disorder, accounting for approximately 2.6% of autism risk and providing a mechanistic link between genetic variation and neurodevelopmental pathology. The complex systems perspective reveals how these expansions introduce cascading perturbations throughout the RNA processing network, particularly through toxic RNA sequestration of splicing regulators. The recent identification of biologically distinct autism subtypes further refines our understanding of how different genetic profiles, including TREs, manifest in particular clinical presentations. Ongoing advances in detection methodologies, particularly long-read sequencing and specialized computational tools, continue to uncover the full scope of TRE contributions to autism. Most promisingly, the elucidation of these mechanisms has enabled development of targeted therapeutic strategies, including antisense oligonucleotides and small molecule approaches, that may eventually allow precision interventions for specific genetic subtypes of autism.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These features are associated with atypical early brain development and connectivity [21]. While ASD has been traditionally associated with molecular genetic alterations, recent research highlights that the timing of genetic disruptions during neurodevelopment plays a crucial role in determining clinical heterogeneity and phenotypic expression [5] [22]. The emerging paradigm recognizes autism not as a single disorder but as a collection of neurodevelopmental conditions with varying underlying biological narratives that unfold across different developmental timelines [5].

The human brain develops through a series of carefully orchestrated, sequential processes beginning in fetal life and continuing into adolescence. These include neural induction and patterning, neurogenesis, neuronal migration, neuronal morphogenesis (axonal and dendritic outgrowth), synaptogenesis, and synaptic pruning [22]. While earlier developmental processes such as neurogenesis are largely experience-independent, later processes including synaptic refinement are highly experience-dependent and influenced by environmental factors [22]. Genetic disruptions occurring at distinct points along this developmental continuum appear to produce different subtypes of autism with characteristic clinical presentations, trajectories, and comorbidities.

Genetic Architecture of ASD and Temporal Dynamics

The genetic architecture of autism is highly heterogeneous, involving hundreds of genetic loci that contribute to disease risk through varied mechanisms. These include single gene mutations, monogenic disorders, copy number variants (CNVs), and chromosomal abnormalities [23]. ASD is highly familial, with studies reporting a heritability of 70-90%, confirmed by twin studies showing concordance rates of 70-90% in monozygotic twins compared to 30-40% in dizygotic twins [23]. However, the specific clinical manifestations and developmental trajectories associated with these genetic risks are increasingly recognized as being determined by when during neurodevelopment these genetic programs are disrupted.

Polygenic Factors and Developmental Timing

Recent evidence reveals that the polygenic architecture of autism can be decomposed into genetically distinct factors associated with different developmental trajectories and ages at diagnosis [24]. Research demonstrates the existence of two modestly genetically correlated (rg = 0.38) autism polygenic factors:

- Factor 1: Associated with earlier autism diagnosis and lower social and communication abilities in early childhood, with only moderate genetic correlations with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mental-health conditions

- Factor 2: Associated with later autism diagnosis and increased socioemotional and behavioural difficulties in adolescence, with moderate to high positive genetic correlations with ADHD and mental-health conditions [24]

These findings indicate that earlier- and later-diagnosed autism have different developmental trajectories and genetic profiles, supporting a developmental model of autism heterogeneity rather than a unitary model [24].

Table 1: Characteristics of Autism Polygenic Factors and Their Relationship to Developmental Timing

| Polygenic Factor | Age at Diagnosis | Developmental Trajectory | Genetic Correlations with Comorbidities | Early Childhood Social-Communication Abilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Earlier diagnosis | Difficulties emerge in early childhood and remain stable | Moderate correlations with ADHD and mental health conditions | Lower abilities |

| Factor 2 | Later diagnosis | Difficulties increase in late childhood/adolescence | High positive correlations with ADHD and mental health conditions | Increased difficulties emerge in adolescence |

Data-Driven Autism Subtypes and Genetic Programs

A groundbreaking 2025 study analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK autism cohort identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism, each with distinct developmental trajectories and genetic programs [5] [17]. This person-centered approach considered over 230 traits in each individual rather than searching for genetic links to single traits, enabling the discovery of subtypes with distinct genetic profiles [5].

Table 2: Characteristics of Autism Subtypes and Their Associated Genetic Programs

| Autism Subtype | Prevalence | Developmental Milestones | Co-occurring Conditions | Genetic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Typically reached on time | ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD | Mutations in genes active later in childhood; highest genetic signals for ADHD and depression |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Delayed walking and talking | Generally absent anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors | Highest proportion of rare inherited genetic variants |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Typically reached on time | Generally absent co-occurring psychiatric conditions | Milder genetic risk profile |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Developmental delays present | Anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation | Highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations |

Critically, these subtypes differ in when genetic disruptions affect brain development. While much genetic impact was thought to occur prenatally, the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype (typically with later diagnosis) shows mutations in genes that become active later in childhood, suggesting biological mechanisms may emerge postnatally [5]. This temporal dimension of genetic action provides a model for understanding autism diversity.

Experimental Approaches for Mapping Temporal Dynamics

Single-Cell Genomics and Brain Mapping

A groundbreaking UCLA Health study as part of the PsychENCODE consortium has provided unprecedented resolution in connecting genetic risk for autism to changes observed in the brain across development [25]. The researchers employed advanced single-cell assays to isolate and analyze genetic information from over 800,000 nuclei from post-mortem brain tissue of 66 individuals (ages 2 to 60, including 33 with ASD) [25]. This approach enabled identification of:

- Major cortical cell types affected in ASD (both neurons and glial cells)

- Specific vulnerability in neurons connecting brain hemispheres and somatostatin interneurons

- Transcription factor networks that drive observed changes

- Direct links between changes in ASD brains and underlying genetic causes [25]

Figure 1: Single-Cell Genomics Workflow for Mapping Temporal Dynamics in ASD

Longitudinal Phenotyping and Developmental Trajectories

Research using longitudinal data from birth cohorts has identified distinct socioemotional and behavioural trajectories associated with age at autism diagnosis [24]. Growth mixture modeling of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) data across multiple cohorts revealed:

- Early childhood emergent latent trajectory: Difficulties in early childhood that remain stable or modestly attenuate in adolescence

- Late childhood emergent latent trajectory: Fewer difficulties in early childhood that increase in late childhood and adolescence [24]

These trajectories are strongly associated with age at diagnosis, with the early childhood trajectory linked to earlier diagnosis and the late childhood trajectory associated with later diagnosis [24]. These associations remain robust after controlling for sociodemographic variables and in sensitivity analyses including individuals with co-occurring ADHD.

Artificial Intelligence and Gene Discovery

Researchers have developed artificial intelligence approaches that accelerate the identification of genes contributing to neurodevelopmental conditions [26]. This powerful computational tool analyzes patterns among genes already linked to neurodevelopmental diseases to predict additional genes that might also be involved. The approach incorporates:

- Gene expression data from developing human brain at single-cell resolution

- More than 300 biological features including mutation intolerance measures

- Protein interaction networks with known disease-associated genes

- Functional roles in biological pathways [26]

These models show exceptionally high predictive value, with top-ranked genes up to six-fold more enriched for high-confidence neurodevelopmental disorder risk genes compared to traditional genic intolerance metrics alone [26]. This approach helps validate genes emerging from sequencing studies that lack sufficient statistical proof of involvement in neurodevelopmental conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Investigating Temporal Dynamics in ASD

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Insights Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Technologies | Single-cell RNA sequencing, Array comparative genomic hybridization (a-CGH), Next-generation sequencing (NGS) | Identification of genetic variants, gene expression patterns, and cellular heterogeneity | Cell-type specific expression changes in ASD; identification of de novo and inherited variants |

| Computational Tools | AI-based prediction models, Growth mixture models, Statistical genetic packages | Pattern recognition in large genomic and phenotypic datasets, trajectory analysis | Identification of autism subtypes; gene discovery; developmental trajectory mapping |

| Biological Samples | Post-mortem brain tissue banks, Saliva samples for DNA analysis, Longitudinal birth cohorts | Genetic and molecular profiling, developmental tracking | Brain region-specific changes; large-scale genetic studies; developmental course documentation |

| Model Systems | Mouse models (e.g., Pten-mutant, Mecp2-null), Human cell cultures, Cerebral organoids | Functional validation of genetic findings, mechanistic studies | Neuronal arborization abnormalities; synaptic function defects; circuit-level consequences |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms Across Development

Genetic studies have pinpointed several critical molecular processes in autism that operate across different developmental timelines [22]. These include: (1) regulation of gene expression; (2) pre-mRNA splicing; (3) protein localization, translation, and turnover; (4) synaptic transmission; (5) cell signaling; (6) cytoskeletal and scaffolding proteins; and (7) neuronal cell adhesion molecules [22]. While these molecular mechanisms appear broad, they may converge on specific steps during neurodevelopment that perturb neuronal circuitry structure, function, and plasticity.

Figure 2: Neurodevelopmental Processes and Associated ASD Subtypes Across Time

The timing of these molecular disruptions maps onto specific neurodevelopmental processes. For example, genes associated with the Broadly Affected autism subtype often impact early developmental processes, while those associated with the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype typically affect later developmental processes such as synaptic refinement and circuit maturation [5] [22]. This temporal mapping provides a framework for understanding how genetic programs disrupt neurodevelopment at specific timepoints to produce distinct autism phenotypes.

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Precision Medicine

The recognition of temporally distinct genetic programs in autism has profound implications for therapeutic development. Rather than seeking a unified treatment for autism, this perspective suggests interventions should be timed and targeted to specific biological pathways active during different developmental windows [5] [22]. For individuals with genetic disruptions affecting early brain development, interventions might focus on promoting neuronal connectivity and circuit formation during critical periods. For those with later-onset genetic mechanisms, treatments might target synaptic function, refinement, and maintenance during childhood and adolescence.

The identification of biologically distinct subtypes enables a precision medicine approach to autism treatment [5] [17]. Understanding which genetic program and developmental trajectory an individual has could help clinicians anticipate challenges, select appropriate interventions, and predict long-term outcomes. Furthermore, this framework emphasizes that therapeutic windows may be specific to biological subtypes rather than applying uniformly across the autism spectrum.

The complex systems perspective on autism recognizes that genetic risks interact with environmental factors and developmental timing to produce diverse outcomes. This conceptualization moves beyond linear cause-effect models toward dynamic, developmental models that account for the emergence of autism phenotypes across time. Future research mapping the precise temporal sequences of genetic expression, brain development, and behavioral manifestation will be essential for developing targeted, effective interventions for different forms of autism.

The New Toolbox: Computational Biology, Multi-Omics, and Novel Therapeutic Targets

Harnessing AI and Machine Learning for Subtype Identification and Trajectory Prediction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a quintessential example of a complex systems disorder, characterized by emergent phenotypes arising from dynamic, multi-scale interactions between genetic, molecular, neural circuit, and environmental factors [5] [27] [28]. The profound heterogeneity in clinical presentation, developmental trajectory, and treatment response has long hindered the development of targeted therapies and precise prognostic tools [29] [30]. Traditional categorical diagnostics fail to capture this multidimensional complexity, necessitating a paradigm shift towards data-driven, quantitative frameworks [28].

This whitepaper outlines how artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing ASD research by deconvoluting this heterogeneity. We detail computational methodologies for identifying biologically distinct subtypes and predicting individual developmental trajectories, thereby providing a roadmap for precision medicine in neurodevelopmental disorders [5] [31] [32].

AI/ML Methodological Framework for Deconstructing Heterogeneity

The core challenge is integrating high-dimensional, multimodal data—spanning genomics, phenomics, neuroimaging, and longitudinal behavioral assessments—to extract clinically and biologically meaningful patterns. The following AI/ML approaches are foundational.

2.1 Person-Centered Subtyping via Finite Mixture Modeling A transformative alternative to trait-centered analyses, this approach models the complete phenotypic profile of an individual to identify latent subgroups [5] [7].

- Experimental Protocol: As employed in the landmark SPARK cohort study (n>5,000), researchers utilized general finite mixture modeling to cluster individuals based on over 230 phenotypic traits [5] [7].

- Data Integration: Diverse data types (binary, categorical, continuous) are handled separately within the model and integrated into a single probability of class membership for each participant.

- Model Training: The algorithm estimates parameters that define latent classes, maximizing the likelihood that individuals within a class share a similar multivariate trait profile.

- Validation & Biological Correlation: Derived subtypes are validated for clinical coherence and then correlated with distinct genetic profiles (e.g., damaging de novo mutations, rare inherited variants) and divergent biological pathways [5].

2.2 Trajectory Prediction via Supervised Machine Learning Predicting longitudinal outcomes requires modeling the relationship between baseline features and future state.

- Experimental Protocol: A clinical cohort study (n=1,225) used latent class growth mixture modeling (LCGMM) to first identify distinct adaptive behavior trajectories, then applied supervised ML to predict trajectory membership from intake data [29].

- Outcome Definition (LCGMM): Repeated measures of Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS-3) scores are modeled to identify clusters of individuals following similar growth curves (e.g., "Improving" vs. "Stable" trajectories) [29].

- Feature Engineering: Comprehensive intake data (socioeconomic status, developmental history, baseline symptom severity, co-occurring conditions, paternal age) is compiled [29].

- Model Training & Comparison: Algorithms like Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Elastic Net GLM are trained on a subset (n=729) to predict trajectory class. Performance is compared using accuracy, with Random Forest achieving ~77% accuracy in the cited study [29].

- Predictor Importance: The model is interrogated to identify the strongest baseline predictors of outcome (e.g., socioeconomic status, history of regression, baseline severity) [29].

AI/ML Workflow for Autism Research

Data Integration & Quantitative Trait Paradigm

A systems-level understanding requires moving beyond binary diagnosis to a spectrum of quantitative traits (QTs) that more closely reflect underlying biology [28].

- Key Data Sources: Large-scale cohorts like SPARK provide matched phenotypic and genetic data at an unprecedented scale [5] [7]. Longitudinal networks like the ADDM provide community-level prevalence and trend data [33] [34].

- Quantitative Traits: Measures like the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) and Broader Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAP-Q) capture continuous distributions of social communication and other core traits across clinical and general populations, offering greater statistical power and biological relevance [28].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data from Featured Studies

| Study Focus | Cohort / Sample Size | Key Quantitative Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype Prevalence | SPARK (N > 5,000) | Social & Behavioral Challenges: ~37%; Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay: ~19%; Moderate Challenges: ~34%; Broadly Affected: ~10% | [5] |

| Trajectory Prediction Accuracy | Clinical Cohort (N = 729) | Random Forest model predicted adaptive behavior trajectory membership with ~77% accuracy. | [29] |

| Current ASD Prevalence (US) | ADDM Network (2022) | Approximately 1 in 31 (3.2%) 8-year-old children identified with ASD. | [34] [32] |

| Genetic Diagnostic Yield | Standard Care | Genetic testing explains etiology for ~20% of ASD patients. | [5] |

Core Findings: Subtypes, Trajectories & Biology

4.1 Four Biologically Distinct Subtypes The 2025 Nature Genetics study identified four subtypes with distinct clinical and genetic profiles [5] [7] [32]:

- Social & Behavioral Challenges (37%): Core ASD traits, typical developmental milestones, high co-occurring psychiatric conditions (ADHD, anxiety). Genetics involve genes active postnatally.

- Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%): Significant developmental delays, fewer psychiatric conditions. Linked to rare inherited variants and genes active prenatally.

- Moderate Challenges (34%): Milder core traits, typical milestones, low psychiatric co-occurrence.

- Broadly Affected (10%): Severe, wide-ranging challenges including delay, core traits, and psychiatric conditions. Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations.

4.2 Predictors of Developmental Trajectory The trajectory prediction study highlighted that socioeconomic status, history of developmental regression, baseline symptom severity, and paternal age were stronger predictors of adaptive behavior outcome than cumulative hours of standard therapies like ABA [29].

Subtype-Linked Genetic & Pathway Differences

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven ASD Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Data | Provides large-scale, matched genotypic and deep phenotypic data essential for training robust AI models for subtyping. | Simons Foundation initiative; >150,000 individuals [5] [7]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Enable whole exome/genome sequencing to identify genetic variants (de novo, inherited) for correlation with subtypes. | Critical for linking subtypes to distinct genetic architectures [5] [32]. |

| Quantitative Trait Assessment Batteries | Measure continuous distributions of core ASD traits (social communication, RRB) and co-occurring conditions. | SRS, BAP-Q, VABS-3 [29] [28]. |

| Cloud-Based Computational Infrastructure | Provides scalable resources (CPU/GPU) for running intensive mixture models, deep learning, and large-scale simulations. | Essential for analyzing multimodal "big data" [5] [31]. |

| FDA-Cleared Digital Phenotyping Tools | Provide objective, scalable measures of behavior (e.g., eye gaze, motor patterns) for model input. | EarliPoint (eye-tracking), tablet-based motor analysis apps [31]. |

| Biobank & Integrated 'Omics Data | Tissue/DNA samples linked to clinical data for exploring transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic correlates of subtypes. | Enables mapping of biological pathways downstream of genetics [5] [27]. |

The integration of AI and ML represents a paradigm shift in autism research, transforming it from a search for a unified explanation to the dissection of a complex system into tractable, biologically coherent components [5] [32]. The identification of data-driven subtypes linked to distinct genetic mechanisms and developmental timelines provides a foundational framework for precision medicine. Future directions include:

- Incorporating non-coding genomic data and additional 'omics layers (transcriptomics, proteomics) [7].

- Validating subtypes and predictive models in prospective, independent cohorts.

- Using these frameworks to stratify patients for targeted clinical trials, moving beyond symptom-based to mechanism-based interventions [32]. This approach finally offers a path to align the complexity of autism's clinical presentation with the precision required for effective scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) exemplifies a complex systems disorder where perturbations across multiple biological scales—from molecular splicing to neural circuitry—interact to produce behavioral outcomes. The integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is indispensable for mapping these cascading effects. This technical review delineates how initial genetic risks, mediated through mechanisms like alternative splicing and gut-brain axis communication, propagate through proteomic and metabolic networks to disrupt synaptic homeostasis, autophagy, and ultimately, neural circuit function. We synthesize findings from recent large-scale omics studies, provide detailed experimental workflows for key methodologies, and visualize critical signaling pathways. The synthesis underscores that therapeutic innovation in ASD necessitates a systems-level approach capable of interrogating these dynamic, cross-scale interactions.

The etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by profound heterogeneity and polygenicity, with heritability estimates ranging from 64% to 91% [35] [36]. Traditional single-omics approaches have identified hundreds of risk loci but have struggled to explain the mechanistic pathways from genetic variation to circuit-level dysfunction and behavioral symptoms. The conceptualization of ASD as a complex systems disorder posits that its pathogenesis arises from the dynamic interplay of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and dysregulated biological networks across multiple organ systems, including the brain, immune system, and gastrointestinal tract [37] [8] [35].

Multi-omics integration provides the analytical framework to dissect this complexity. By concurrently analyzing data from genomes, transcriptomes, proteomes, and metabolomes, researchers can construct predictive models of how a mutation in a non-coding region influences RNA splicing, how the resulting aberrant protein disrupts synaptic phospho-signaling, and how gut microbiome-derived metabolites may modulate this process through peripheral immune activation [38] [39] [35]. This whitepaper details the core technical pathways and methodologies for mapping this cascade, providing a guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to identify coherent therapeutic targets within this entangled network.

Core Pathway: From Splicing to Circuit Dysfunction

Genetic Variation and Aberrant Splicing

The pathway to neural circuit dysfunction often originates with genetic variation that disrupts the precise regulation of alternative splicing (AS). AS is a critical RNA regulatory mechanism that allows a single gene to generate multiple mRNA and protein isoforms, and its dysregulation is a key contributor to ASD pathogenesis [19]. Splicing defects are particularly consequential for genes encoding synaptic cellular adhesion molecules (CAMs) and scaffold proteins, such as neurexins (NRXN), neuroligins (NLGN), and SHANK proteins [19] [40].