Assessing Predictive Models of Patient Outcomes: From Machine Learning to Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to develop, evaluate, and implement predictive models for patient outcomes.

Assessing Predictive Models of Patient Outcomes: From Machine Learning to Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to develop, evaluate, and implement predictive models for patient outcomes. It explores the foundational principles of predictive modeling, examines cutting-edge methodologies from machine learning to large language models, and addresses critical challenges in data quality, generalizability, and ethical implementation. A strong emphasis is placed on rigorous validation, comparative performance analysis, and the pathway to demonstrating tangible clinical impact, synthesizing recent advancements to guide evidence-based model integration into biomedical research and clinical practice.

The Foundation of Predictive Healthcare: Principles, Promise, and Core Metrics

The healthcare landscape is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a traditional reactive model—treating symptoms of established disease—to a proactive paradigm focused on prevention, early intervention, and personalization [1] [2]. This shift is propelled by molecular insights into disease pathophysiology and enabled by technological advancements in data science and artificial intelligence (AI) [1]. Within this broader transition, the development and assessment of predictive models for patient outcomes have become a cornerstone of modern clinical research and drug development. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of key modeling approaches that underpin proactive and personalized care, providing researchers and scientists with a framework for evaluation.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Modeling Paradigms

The efficacy of a predictive model is contingent on its design, the data it utilizes, and its intended clinical application. The table below summarizes the experimental performance and key characteristics of three dominant modeling paradigms discussed in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance and Characteristics of Patient Outcome Predictive Models

| Model Paradigm | Primary Study / Application | Key Performance Metric (AUC) | Dataset & Sample Size | Core Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global (Population) Model | Diabetes Onset Prediction [3] | 0.745 (Baseline Reference) | 15,038 patients from medical claims data | Captures broad population-level risk factors; simpler to implement. | "One size fits all" may miss individual-specific risk factors [3]. |

| Personalized (KNN-based) Model | Diabetes Onset Prediction [3] | Up to ~0.76 (with LSML metric) | 15,038 patients; models built per patient from similar cohort | Dynamically customized for individual patients; can identify patient-specific risk profiles [3]. | Performance depends on quality of similarity metric and cohort size [3]. |

| Deep Learning (Sequential Data) Model | Systematic Review of Outcome Prediction [4] | Positive correlation with sample size (P=.02) | 84 studies; sample sizes varied widely | Captures temporal dynamics and hierarchical relationships in EHR data; end-to-end learning [4]. | High risk of bias (70% of studies); often lacks generalizability and explainability [4]. |

| Unified Time-Series Framework | Pneumonia Outcome Forecasting [5] | Effective & Robust (Specific metrics N/A) | CAP-AI dataset from University Hospitals of Leicester | Leverages sequential clinical data of varying lengths; models imbalanced and skewed outcome distributions. | Requires sophisticated handling of irregular time-series and admission data integration. |

| Equity-Aware AI Model (BE-FAIR) | Population Health Management [6] | Calibrated to reduce underprediction for minority groups | UC Davis Health patient population | Framework embeds equity assessment to mitigate health disparities in prediction [6]. | Requires custom development and systematic evaluation specific to a health system's population. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Personalized Predictive Modeling for Diabetes Onset

This protocol is derived from the study employing Locally Supervised Metric Learning (LSML) to build personalized logistic regression models [3].

- Cohort Construction: Assemble a longitudinal dataset from Electronic Health Records (EHR) or medical claims. Identify incident cases (e.g., patients with a new diabetes diagnosis in the latter half of the observation window) and match them with controls based on demographics (age, gender) [3].

- Feature Engineering: Define an observation window (e.g., first 24 months). Aggregate patient events (diagnoses, medications, procedures) within the window into feature vectors (e.g., counts for categorical variables). Perform global feature selection (e.g., using information gain) to reduce dimensionality [3].

- Similarity Metric Training: Train the LSML distance metric ((D{LSML}(xi, xj) = (xi - xj)^T W W^T (xi - x_j))) on the training set to maximize local class discriminability for the specific target condition (e.g., diabetes onset) [3].

- Personalized Model Training (per test patient):

- Identify the K most clinically similar patients from the training set for a given test patient using the trained LSML metric.

- Apply feature filtering to the similar cohort, retaining features present in the test patient or in ≥2 similar patients.

- Train a logistic regression model on this filtered, similar-patient cohort.

- Use the model to compute a diabetes onset risk score for the test patient [3].

- Validation: Employ 10-fold cross-validation. Evaluate performance using the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) and compare against a global logistic regression model trained on all data [3].

Protocol 2: Development of an Equity-Aware AI Predictive Model (BE-FAIR Framework)

This protocol outlines the nine-step framework used by UC Davis Health to create a bias-reduced model for predicting hospitalizations and ED visits [6].

- Multidisciplinary Team Assembly: Form a team encompassing population health, information technology, and health equity expertise [6].

- Problem & Outcome Definition: Define the target prediction (e.g., 12-month risk of hospitalization or emergency department visit).

- Data Source Identification: Consolidate relevant patient data from EHR and other health system sources.

- Predictor Variable Selection: Choose candidate variables based on clinical relevance and data availability.

- Model Training & Algorithm Selection: Train initial predictive models (e.g., ensemble ML methods) on historical data.

- Equity-Focused Evaluation: Rigorously evaluate model calibration and performance across different racial, ethnic, and demographic subgroups to identify underprediction or bias [6].

- Threshold Adjustment & Mitigation: Adjust prediction thresholds or implement post-processing techniques to improve equity in risk scoring and patient identification [6].

- Implementation & Workflow Integration: Integrate the model into clinical workflows, providing care managers with risk scores. Establish protocols for proactive patient outreach [6].

- Continuous Monitoring & Re-evaluation: Establish ongoing monitoring of model performance and equity metrics, with plans for periodic retraining [6].

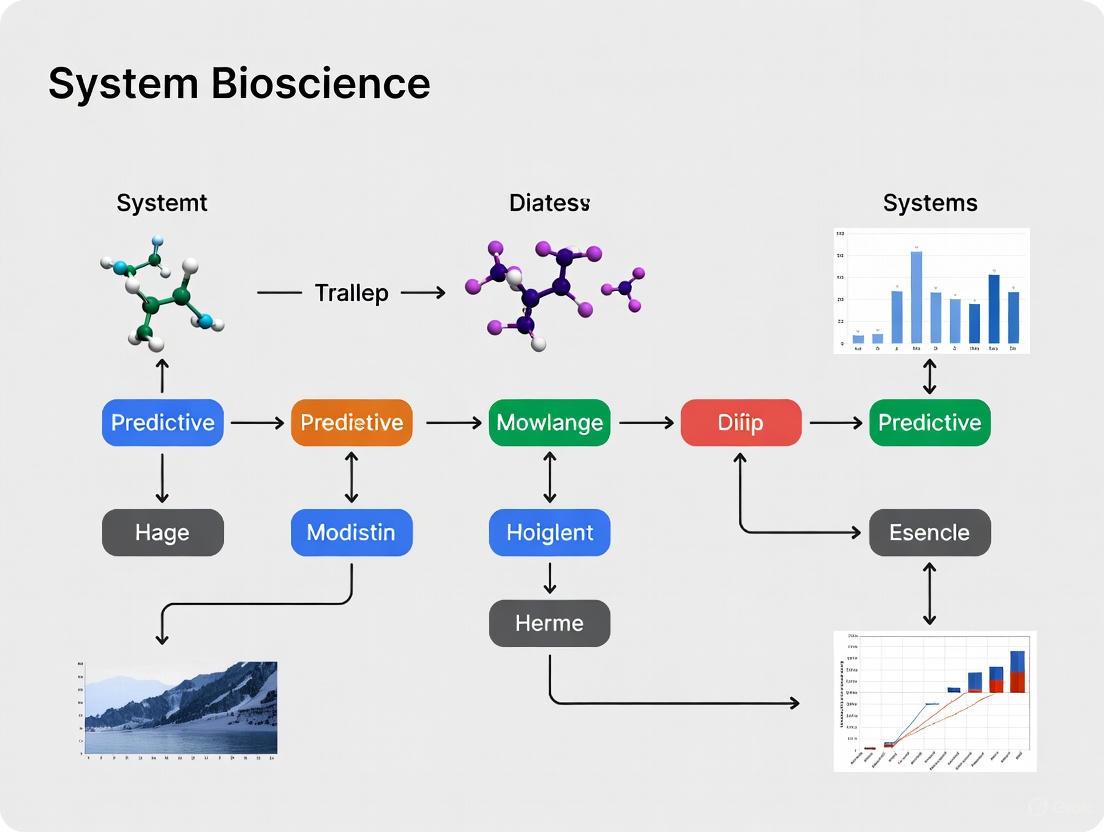

Visualizing the Predictive Modeling Workflow and AI Pipeline

Diagram 1: Workflows for Personalized Prediction and AI-Driven Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Solutions for Predictive Outcomes Research

| Item | Function & Application in Research | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal EHR/Claims Datasets | Provides the raw, time-stamped patient event data (diagnoses, medications, labs) necessary for feature engineering and model training. | 15,038 patient cohort for diabetes prediction [3]; CAP-AI dataset for pneumonia outcomes [5]. |

| Structured Medical Code Vocabularies (ICD-10, SNOMED-CT) | Standardizes diagnosis, procedure, and medication data, enabling consistent feature extraction and model generalizability across systems. | Sequential diagnosis codes used as primary input for deep learning models [4]. |

| Trainable Similarity Metric (e.g., LSML) | A crucial algorithmic component for personalized models that learns a disease-specific distance measure to find clinically similar patients [3]. | LSML used to customize cohort selection for diabetes onset prediction [3]. |

| Deep Learning Architectures (RNN/LSTM, Transformers) | Software frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) implementing these architectures are essential for modeling sequential, temporal relationships in patient journeys. | RNNs/Transformers used in 82% of studies analyzing sequential diagnosis codes [4]. |

| Equity Assessment Toolkit | A set of statistical and visualization tools (e.g., calibration plots by subgroup, fairness metrics) required to evaluate and mitigate bias in predictive models. | Core component of the BE-FAIR framework to identify and correct underprediction for racial/ethnic groups [6]. |

| Model Explainability (XAI) Libraries | Software tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) that help interpret complex model predictions, building trust and facilitating clinical translation. | Needed to address the explainability gap noted in 45% of DL-based studies [4]. |

| Validation Frameworks (PROBAST, TRIPOD) | Methodological guidelines and checklists that provide a standardized protocol for assessing the risk of bias and reporting quality in predictive model studies. | PROBAST used to assess high risk of bias in 70% of reviewed DL studies [4]. |

The paradigm shift toward proactive and personalized care is intrinsically linked to advances in predictive analytics. As evidenced by the comparative data, no single modeling approach is universally superior. Global models offer baseline efficiency, while personalized models promise tailored accuracy at the cost of complexity [3]. Deep learning methods unlock temporal insights but raise concerns regarding bias, generalizability, and explainability that must be actively managed [6] [4]. For researchers and drug developers, the critical task is to align the choice of modeling paradigm—be it for patient risk stratification, clinical trial enrichment, or drug safety prediction [8]—with the specific clinical question, available data quality, and an unwavering commitment to equitable and interpretable outcomes. The future of patient outcomes research lies in the rigorous, context-aware application and continuous refinement of these powerful tools.

In patient outcomes research, the assessment of predictive models extends beyond simple accuracy. For researchers and drug development professionals, a model's value is determined by its discriminative ability, the reliability of its probability estimates, and its overall predictive accuracy. These aspects are quantified by three cornerstone classes of metrics: Discrimination (AUC-ROC, C-statistic), Calibration, and Overall Performance (Brier Score). The machine learning community often focuses on discrimination, but in clinical settings, a model with high discrimination that is poorly calibrated can lead to overconfident or underconfident predictions that misguide clinical decisions and compromise patient safety [9] [10]. For instance, a model predicting a 90% risk of heart disease should mean that 9 out of 10 such patients actually have the disease; calibration measures this agreement. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation integrating all three metric classes is not just best practice—it is a fundamental requirement for deploying trustworthy models in healthcare [11] [12].

Metric Definitions and Theoretical Frameworks

Discrimination: The AUC-ROC and C-Statistic

Discrimination is a model's ability to distinguish between different outcome classes, such as patients who will versus will not experience an adverse event. The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), often equivalent to the C-statistic in binary outcomes, is the primary metric for this purpose [13].

The ROC curve is a plot of a model's True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against its False Positive Rate (1 - Specificity) across all possible classification thresholds. The AUC-ROC summarizes this curve into a single value. Mathematically, the AUC can be interpreted as the probability that a randomly chosen positive instance (e.g., a patient with the disease) will have a higher predicted risk than a randomly chosen negative instance (a patient without the disease) [10]. Its value ranges from 0 to 1, where 0.5 indicates performance no better than random chance, and 1.0 represents perfect discrimination.

Calibration: The Reliability of Probabilities

Calibration refers to the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed event frequencies. A perfectly calibrated model ensures that among all instances assigned a predicted probability of p, the proportion of actual positive outcomes is p [10]. Formally, this is expressed as:

ℙ(Y=1|f(X)=p)=p ∀p ∈[0,1]

where f(X) is the model's predicted probability [10].

Unlike discrimination, calibration is not summarized by a single metric. Instead, it is assessed using a suite of tools:

- Calibration Plots (Reliability Diagrams): A visual tool plotting predicted probabilities (x-axis) against observed event frequencies (y-axis). A well-calibrated model will have points close to the 45-degree diagonal line [10].

- Expected Calibration Error (ECE): A weighted average of the absolute difference between confidence and accuracy within bins of predicted probability [9] [10].

- Spiegelhalter's Z-Test: A statistical test for calibration where a non-significant p-value (e.g., p > 0.05) suggests no major miscalibration [14] [9].

- Hosmer-Lemeshow (HL) Test: Another goodness-of-fit test for calibration, where a non-significant p-value indicates good calibration [14].

The Brier Score is an overall measure of predictive accuracy. It is defined as the mean squared difference between the predicted probability and the actual outcome [12] [10].

BS = 1/n * ∑(f(x_i) - y_i)²

where f(x_i) is the predicted probability and y_i is the actual outcome (0 or 1).

The Brier score ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 representing perfect accuracy. Its key strength is that it incorporates both discrimination and calibration into a single value. A model with good discrimination but poor calibration will be penalized with a higher Brier score [12]. Recent research has proposed a weighted Brier score to align this metric more closely with clinical utility by incorporating cost-benefit trade-offs inherent in clinical decision-making [12].

Comparative Analysis of Performance Metrics

The table below provides a structured comparison of these core metrics, highlighting what they measure, their interpretation, and inherent strengths and weaknesses.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Performance Metrics for Predictive Models

| Metric | What It Measures | Interpretation & Range | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC / C-statistic | Model's ability to rank order patients (e.g., high-risk vs. low-risk). | 0.5 (No Disc.) - 1.0 (Perfect). A value of 0.7-0.8 is considered acceptable, 0.8-0.9 excellent, and >0.9 outstanding. | Threshold-invariant: Provides an overall performance measure across all decision thresholds. Intuitive interpretation as probability. | Does not assess calibration: A model can have high AUC but be severely miscalibrated. Insensitive to class imbalance in some cases. |

| Calibration Metrics | Agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. | Perfect calibration is achieved when the calibration curve aligns with the diagonal. ECE/Spiegelhalter's test should be low/non-significant. | Crucial for risk estimation: Essential for models whose outputs inform treatment decisions based on risk thresholds. | No single summary statistic: Requires multiple metrics and visualizations for a complete picture. Can be dependent on the binning strategy (for ECE). |

| Brier Score | Overall accuracy of probability estimates, combining discrimination and calibration. | 0 (Perfect) - 1 (Worst). A lower score indicates better overall performance. | Composite Measure: Naturally balances discrimination and calibration. A strictly proper scoring rule, meaning it is optimized by predicting the true probability. | Less intuitive: The absolute value can be difficult to interpret without a baseline. Amalgamates different types of errors into one number. |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

Case Study: Calibration Assessment in Heart Disease Prediction

A 2025 study on heart disease prediction provides a robust experimental protocol for a comprehensive model evaluation, benchmarking six classifiers and two post-hoc calibration methods [9].

1. Study Objective: To evaluate and improve the calibration and uncertainty quantification of machine learning models for heart disease classification.

2. Dataset and Preprocessing:

- Dataset: A structured clinical dataset with 1,025 records related to heart disease.

- Train-Test Split: An 85/15 split was used, a common hold-out validation method.

- Models Benchmark: Six classifiers were trained: Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Naive Bayes, Random Forest, and XGBoost.

3. Performance Evaluation Workflow: The experiment followed a structured workflow to assess baseline performance and the impact of post-hoc calibration, as visualized below.

Model Evaluation and Calibration Workflow

4. Key Findings and Quantitative Results: The study demonstrated that models with perfect discrimination could still be poorly calibrated. Post-hoc calibration, particularly Isotonic Regression, consistently improved probability quality without harming discrimination.

Table 2: Experimental Results from Heart Disease Prediction Study [9]

| Model | Baseline Accuracy | Baseline ROC-AUC | Baseline Brier Score | Baseline ECE | Post-Calibration (Isotonic) Brier Score | Post-Calibration (Isotonic) ECE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | ~100% | ~100% | 0.007 | 0.051 | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| SVM | 92.9% | 99.4% | N/R | 0.086 | N/R | 0.044 |

| Naive Bayes | N/R | N/R | 0.162 | 0.145 | 0.132 | 0.118 |

| k-NN (KNN) | N/R | N/R | N/R | 0.035 | N/R | 0.081* |

Note: N/R = Not Explicitly Reported in Source; *Platt scaling worsened ECE for KNN, highlighting the need to evaluate both methods.

Building and evaluating predictive models requires a suite of statistical tools and software resources. The table below details key "research reagents" for a robust evaluation protocol.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Predictive Model Evaluation

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in Evaluation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROBAST Tool [13] | Methodological Guideline | A structured tool to assess Risk Of Bias and applicability in prediction model studies. | Used in systematic reviews to ensure included models are methodologically sound. |

| Platt Scaling [9] [10] | Post-hoc Calibration Algorithm | A parametric method that fits a sigmoid function to map classifier outputs to better-calibrated probabilities. | Improving the probability outputs of an SVM model for clinical use. |

| Isotonic Regression [9] [10] | Post-hoc Calibration Algorithm | A non-parametric method that learns a monotonic mapping to calibrate probabilities, more flexible than Platt scaling. | Calibrating a Random Forest model that showed significant overconfidence. |

| Reliability Diagram [11] [10] | Visual Diagnostic Tool | Plots predicted probabilities against observed frequencies to provide an intuitive visual assessment of calibration. | The primary visual tool used in the heart disease study to show calibration before and after intervention [9]. |

| Brier Score Decomposition [12] | Analytical Framework | Breaks down the Brier score into reliability (calibration), resolution, and uncertainty components for nuanced analysis. | Diagnosing whether a poor Brier score is due to miscalibration or poor discrimination. |

| Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) [13] [12] | Clinical Usefulness Tool | Evaluates the net benefit of using a model for clinical decision-making across a range of risk thresholds. | Justifying the clinical implementation of a model by showing its added value over default strategies. |

For professionals in drug development and patient outcomes research, a singular focus on any one class of performance metrics is a critical oversight. Discrimination (AUC-ROC), Calibration, and Overall Performance (Brier Score) are three pillars of a robust model assessment. The evidence shows that a model with stellar discrimination can produce dangerously miscalibrated probabilities, undermining its clinical utility [9]. Therefore, the routine application of a comprehensive evaluation protocol—incorporating the metrics, experimental frameworks, and tools detailed in this guide—is indispensable. This rigorous approach ensures that predictive models are not only statistically sound but also clinically trustworthy and actionable, ultimately enabling better-informed decisions in healthcare and therapeutic development.

The Role of Predictive Modeling in Modern Drug Development and Clinical Trials

The development of new pharmaceuticals is undergoing a transformative shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to a precision-driven paradigm powered by predictive modeling. Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) has emerged as an essential framework that provides quantitative, data-driven insights throughout the drug development lifecycle, from early discovery to post-market surveillance [15]. This approach leverages mathematical models and simulations to predict drug behavior, therapeutic effects, and potential risks, thereby accelerating hypothesis testing and reducing costly late-stage failures [15]. The fundamental strength of predictive modeling lies in its ability to synthesize complex biological, chemical, and clinical data into actionable insights that support more informed decision-making.

The adoption of predictive modeling represents nothing less than a paradigm shift, replacing labor-intensive, human-driven workflows with AI-powered discovery engines capable of compressing timelines and expanding chemical and biological search spaces [16]. Evidence from drug development and regulatory approval has demonstrated that well-implemented MIDD approaches can significantly shorten development cycle timelines, reduce discovery and trial costs, and improve quantitative risk estimates, particularly when facing development uncertainties [15]. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is further expanding the capabilities and applications of predictive modeling in pharmaceutical research.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Modeling Techniques

Traditional Statistical Approaches

Traditional statistical methods have formed the backbone of clinical research and drug development for decades. These approaches include Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models for time-to-event data such as survival analysis, and logistic regression for binary outcomes [17] [18]. The CPH model, in particular, has been widely used for predicting survival outcomes in oncology studies, while logistic regression has been valued for its interpretability and simplicity in clinical settings [17] [19].

These conventional methods operate on well-established statistical principles and offer high interpretability, making them attractive for regulatory submissions. However, they face significant limitations when dealing with complex, high-dimensional datasets characterized by non-linear relationships and multiple interacting variables [17] [4]. Traditional models typically require manual feature selection, which is both time-consuming and dependent on extensive domain expertise, and they often struggle to effectively capture the temporal chronological sequence of patients' medical history [4].

Modern Machine Learning and AI-Driven Approaches

Modern machine learning techniques have dramatically expanded the toolkit available for predictive modeling in drug development. These include tree-based ensemble methods like Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Trees (GBT), deep learning architectures such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformers, and hybrid approaches that combine multiple methodologies [16] [19] [4].

These advanced techniques offer significant advantages in handling complex, high-dimensional data with minimal need for feature engineering. They can automatically uncover associations between inputs and outputs, generate effective embedding spaces to manage high-dimensional problems, and effectively capture temporal patterns in sequential data [4]. However, they often require substantial computational resources, extensive datasets for training, and present challenges in interpretability – a significant concern in clinical and regulatory contexts [19] [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Predictive Modeling Techniques in Drug Development

| Technique | Primary Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cox Regression [17] [18] | Survival analysis, time-to-event outcomes | Statistical robustness, high interpretability, regulatory familiarity | Limited handling of non-linear relationships, proportional hazards assumption |

| Logistic Regression [19] [20] | Binary classification tasks, diagnostic models | Simplicity, interpretability, clinical transparency | Limited capacity for complex relationships, requires feature engineering |

| Random Survival Forest [17] | Censored data, survival analysis with multiple predictors | Handles non-linearity, robust to outliers, requires less preprocessing | Less interpretable, computationally intensive with large datasets |

| Gradient Boosting Machines [19] [20] | Various prediction tasks including CVD risk and COVID-19 case identification | High predictive accuracy, handles mixed data types | Prone to overfitting without careful tuning, complex interpretation |

| Deep Learning (RNNs/Transformers) [4] | Sequential health data, medical history patterns | Automatic feature learning, captures complex temporal relationships | High computational demands, "black box" nature, requires large datasets |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology [15] | Mechanistic modeling of drug effects | Incorporates physiological knowledge, explores system-level behaviors | Complex model development, requires specialized expertise |

Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Machine Learning Approaches

Comparative studies have yielded nuanced insights into the performance of traditional versus machine learning approaches. A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis of machine learning models for cancer survival outcomes found that ML models showed no superior performance over CPH regression, with a standardized mean difference in AUC or C-index of just 0.01 (95% CI: -0.01 to 0.03) [17]. This suggests that while machine learning approaches offer advantages in handling complex data structures, they do not necessarily outperform well-specified traditional models for all applications.

However, in other domains, machine learning has demonstrated superior performance. A 2024 study comparing AI/ML approaches with classical regression for COVID-19 case prediction found that the Gradient Boosting Trees (GBT) method significantly outperformed multivariate logistic regression (AUC = 0.796 ± 0.017) [20]. Similarly, in predicting cardiovascular disease risk among type 2 diabetes patients, the XGBoost model demonstrated consistent performance (AUC = 0.75 training, 0.72 testing) with better generalization ability compared to other algorithms [19].

These comparative results highlight that the optimal modeling approach depends heavily on the specific application, data characteristics, and clinical context, rather than there being a universally superior technique.

Key Applications in the Drug Development Pipeline

Drug Discovery and Preclinical Development

Predictive modeling has revolutionized early-stage drug discovery through approaches like quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling [15]. AI-driven platforms have demonstrated remarkable efficiency gains, with companies like Exscientia reporting in silico design cycles approximately 70% faster and requiring 10× fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [16]. Insilico Medicine's generative-AI-designed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug progressed from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months, dramatically compressing the typical 5-year timeline for discovery and preclinical work [16].

Leading AI-driven drug discovery platforms have employed diverse approaches, including generative chemistry (Exscientia), phenomics-first systems (Recursion), integrated target-to-design pipelines (Insilico Medicine), knowledge-graph repurposing (BenevolentAI), and physics-plus-ML design (Schrödinger) [16]. These platforms leverage machine learning and generative models to accelerate tasks that were long reliant on cumbersome trial-and-error approaches, representing a fundamental shift in early-stage research and development.

Clinical Trial Optimization

In clinical development, predictive modeling enhances trial design and execution through several critical applications. First-in-Human (FIH) dose algorithms incorporate toxicokinetic PK, allometric scaling, and semi-mechanistic PK/PD approaches to determine starting doses and escalation schemes [15]. Adaptive trial designs enable dynamic modification of clinical trial parameters based on accumulated data, while clinical trial simulations use mathematical and computational models to virtually predict trial outcomes and optimize study designs before conducting actual trials [15].

Population pharmacokinetics and exposure-response (PPK/ER) modeling characterize clinical population pharmacokinetics and exposure-response relationships, supporting dosage optimization and regimen selection [15]. These approaches help explain variability in drug exposure among individuals and establish relationships between drug exposure and effectiveness or adverse effects, ultimately supporting more efficient and informative clinical trials.

Clinical Implementation and Patient Outcome Prediction

In clinical settings, predictive models are increasingly deployed to guide diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. A systematic review of deep learning models using sequential diagnosis codes from electronic health records found these approaches particularly valuable for predicting patient outcomes, with the most frequent applications being next-visit diagnosis (23%), heart failure (14%), and mortality (13%) prediction [4]. The analysis revealed that using multiple types of features, integrating time intervals, and including larger sample sizes were generally related to improved predictive performance [4].

However, challenges remain in clinical implementation. A systematic review of implemented clinical prediction models found that only 13% of models have been updated following implementation, and external validation was performed for just 27% of models [21]. Additionally, 70% of deep learning-based prediction models were found to have a high risk of bias, highlighting the importance of rigorous methodology and validation [4].

Table 2: Applications of Predictive Modeling Across Drug Development Stages

| Development Stage | Modeling Approaches | Key Questions Addressed | Impact Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery [15] [16] | QSAR, Generative AI, Knowledge Graphs | Target identification, lead compound optimization | 70% faster design cycles (Exscientia), 10× fewer compounds synthesized |

| Preclinical Development [15] | PBPK, Semi-mechanistic PK/PD | Preclinical prediction accuracy, FIH dose selection | 18 months from target to Phase I (Insilico Medicine) vs. typical 5 years |

| Clinical Trials [15] | PPK/ER, Clinical Trial Simulation, Adaptive Designs | Dose optimization, trial efficiency, subgroup identification | Reduced trial costs, improved probability of success |

| Regulatory Review [15] [22] | Model-Integrated Evidence, Bayesian Inference | Safety and effectiveness evaluation, label claims | >500 submissions with AI components to CDER (2016-2023) |

| Post-Market Surveillance [15] | Model-Based Meta-Analysis, Virtual Population Simulation | Real-world safety monitoring, label updates | Ongoing benefit-risk assessment |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Protocol Development for Predictive Model Studies

Robust development of predictive models requires rigorous methodological planning. Protocol registration on platforms such as ClinicalTrials.gov is essential for reducing transparency risks and methodological inconsistencies [18]. A comprehensive study protocol should detail all aspects of model development and evaluation, including data sources, preprocessing methods, feature selection approaches, model training procedures, and validation strategies [18].

Engaging end-users including clinicians, patients, and public representatives early in the development process is critical for ensuring model relevance and usability in real-world settings [18]. This collaborative approach helps clarify clinical questions, informs selection of meaningful predictors, and guides how predictions will integrate into clinical workflows – all essential factors for successful implementation and impact.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

High-quality data preprocessing is fundamental to developing reliable predictive models. The Boruta algorithm, a random forest-based wrapper method, has demonstrated effectiveness for feature selection in clinical datasets by iteratively comparing feature importance with randomly permuted "shadow" features [19]. This approach identifies all relevant predictors rather than just a minimal subset, which is particularly advantageous in clinical research where disease risk is typically influenced by multiple interacting factors [19].

For handling missing data, Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) provides a flexible approach that models each variable with missing data conditionally on other variables in an iterative fashion [19]. This method is particularly well-suited for clinical datasets containing different types of variables (continuous, categorical, binary) and complex missing patterns, as it accounts for multivariate relationships among variables and produces multiple imputed datasets that fully incorporate uncertainty caused by missingness.

Model Training and Validation Frameworks

Comprehensive validation is essential for assessing model performance and generalizability. Internal validation using bootstrapping or cross-validation provides initial performance estimates, while external validation in completely independent datasets is crucial for assessing real-world applicability [18]. When possible, internal-external validation approaches, where a prediction model is iteratively developed on data from multiple subsets and validated on remaining excluded subsets, can explore heterogeneity in model performance across different settings [18].

Model evaluation should extend beyond discrimination metrics (e.g., AUC, C-index) to include calibration assessment and clinical utility evaluation [18]. Calibration plots examine how well predicted probabilities align with observed outcomes, while decision curve analysis can assess the net benefit of using the model for clinical decision-making across different threshold probabilities.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Platforms for Predictive Modeling

| Tool/Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Driven Discovery Platforms [16] | Exscientia, Insilico Medicine, Recursion, BenevolentAI, Schrödinger | End-to-end drug candidate identification and optimization | Small-molecule design, target discovery, clinical candidate selection |

| Feature Selection Algorithms [19] | Boruta Algorithm | Identify all relevant predictors in high-dimensional clinical datasets | Preprocessing for clinical prediction models, biomarker identification |

| Machine Learning Frameworks [19] [20] | XGBoost, LightGBM, Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks | Model development for classification and prediction tasks | CVD risk prediction, COVID-19 case identification, survival analysis |

| Model Interpretation Tools [19] | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Visual interpretation of complex model predictions | Explainability for clinical adoption, feature importance analysis |

| Data Imputation Methods [19] | MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations) | Handle missing data in clinical datasets with mixed variable types | Data preprocessing for real-world clinical datasets |

| Deployment Platforms [19] | Shinyapps.io | Web-based deployment of predictive models for clinical use | Clinical decision support tools, risk assessment platforms |

Visualization of Predictive Modeling Workflows

The MIDD Framework Across Drug Development Stages

The following diagram illustrates how predictive modeling integrates throughout the drug development lifecycle, based on the Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) framework:

MIDD Framework in Drug Development - This diagram illustrates how predictive modeling integrates throughout the drug development lifecycle using the Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) framework, emphasizing the "fit-for-purpose" approach where tools are aligned with specific development stage questions.

AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platform Architecture

The following diagram outlines the core architecture and workflow of modern AI-driven drug discovery platforms:

AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platform - This architecture diagram shows the core components and workflow of modern AI-driven drug discovery platforms, highlighting how diverse data sources feed into specialized AI approaches that accelerate the candidate identification and optimization process.

Regulatory Landscape and Implementation Challenges

Regulatory Evolution and Current Framework

The regulatory landscape for predictive modeling in drug development is rapidly evolving to keep pace with technological advancements. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recognized the increased use of AI throughout the drug product lifecycle and has established the CDER AI Council to provide oversight, coordination, and consolidation of AI-related activities [22]. This council serves as a decisional body that coordinates, develops, and supports both internal and external AI-related activities in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

International harmonization efforts are also underway, with the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) expanding its guidance to include MIDD through the M15 general guidance [15]. This global harmonization promises to improve consistency among global sponsors in applying MIDD in drug development and regulatory interactions, potentially promoting more efficient processes worldwide. The FDA has also published a draft guidance in 2025 titled "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Support Regulatory Decision Making for Drug and Biological Products," which provides recommendations on using AI to produce information supporting regulatory decisions regarding drug safety, effectiveness, or quality [22].

Implementation Barriers and Mitigation Strategies

Despite significant advances, substantial barriers impede the widespread implementation of predictive models in clinical practice and drug development. A systematic review of implemented clinical prediction models found that 86% of publications had high risk of bias, and only 32% of models were assessed for calibration during development and internal validation [21]. This highlights critical methodological shortcomings that undermine model reliability and trust.

Additional implementation challenges include limited stakeholder engagement during development, insufficient evidence of clinical utility, and lack of consideration for workflow integration [18]. Furthermore, fewer than half of deep learning-based prediction models address explainability challenges, and only 8% evaluate generalizability across different populations or settings [4]. These limitations significantly hamper clinical adoption and real-world impact.

To address these challenges, researchers should prioritize early and meaningful stakeholder engagement, comprehensive external validation, rigorous fairness assessment across demographic groups, and development of post-deployment monitoring plans [18]. Following established reporting guidelines such as TRIPOD+AI (Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis + Artificial Intelligence) enhances transparency, reproducibility, and critical appraisal of predictive models [18].

Predictive modeling has fundamentally transformed drug development, enabling more efficient, targeted, and evidence-based approaches across the entire pharmaceutical lifecycle. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning has further accelerated this transformation, with AI-designed therapeutics now advancing through human trials across diverse therapeutic areas [16]. However, the field must address critical challenges related to model robustness, fairness, explainability, and generalizability to fully realize the potential of these advanced approaches.

Future progress will depend on developing more transparent and interpretable models, establishing standardized validation frameworks, and fostering collaboration between computational scientists, clinical researchers, and regulatory experts. As predictive modeling continues to evolve, its role in supporting personalized treatment approaches, optimizing clinical trial designs, and improving drug safety monitoring will expand, ultimately enhancing the efficiency of pharmaceutical development and the quality of patient care. The organizations that successfully navigate this complex landscape – balancing innovation with methodological rigor – will lead the next wave of advances in drug development and clinical research.

Understanding Results-Based Management (RBM) for Healthcare Performance

Results-Based Management (RBM) is a strategic framework that shifts the focus of healthcare programs and interventions from activities to measurable outcomes. Within the context of assessing predictive models for patient outcomes research, RBM provides a structured approach to define expected results, monitor progress using performance indicators, and utilize evidence for evaluation and decision-making [23] [24]. This guide compares the application and performance of different predictive models used within the RBM framework to enhance healthcare delivery and patient care.

The RBM Framework in Healthcare

RBM operates on three core principles: goal-orientedness, which involves setting clear targets; causality, which requires mapping the logical links between inputs, activities, and results; and continuous improvement, which uses performance data for learning and adaptation [23]. In healthcare, this translates to a management cycle of planning, monitoring, and evaluation to improve efficiency and effectiveness [25] [24].

The "Results Chain" is a central tool in RBM, providing a visual model of the causal pathway from a program's inputs to its long-term impact [26] [24]. The following diagram illustrates this logic as applied to a healthcare intervention.

Figure 1: RBM Results Chain for Healthcare. This logic model shows the cause-and-effect pathway from program inputs to long-term health impact [23] [26] [24].

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Models for RBM

Predictive models are crucial for analyzing performance indicator results, forecasting trends, and enabling evidence-based decision-making within the RBM framework [25]. The table below compares three established statistical models.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Predictive Models in Healthcare RBM

| Predictive Model | Best-Performing Context (from studies) | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Primary Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression (LR) | Analyzing 9 out of 10 medical performance indicators (e.g., hospital efficiency, bed turnover) [25] | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Lowest MAE for 9 indicators; 7 with p < 0.05 [25] | Powerful, widely applicable statistical tool [25] | Sensitive to outliers; requires checking of assumptions (normality, homoskedasticity) [25] |

| Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) | Forecasting patient attendance at hospital services [25] | Forecast Error | ~3% error in predicting expected annual patients [25] | Effectively captures linear patterns and trends in time series data [25] | Less effective with non-linear data patterns [25] |

| Exponential Smoothing (ES) | Short-term forecasting with limited historical data (e.g., electricity demand) [25] | Error Rate | Highly accurate predictions with minimal errors [25] | Robust, simple formulation, requires few calculations [25] | Best for short-term forecasts; may not capture complex long-term trends [25] |

Advanced and Hybrid Predictive Models

Beyond traditional statistical models, machine learning (ML) and hybrid deep learning approaches offer advanced capabilities for handling complex healthcare data, such as high-dimensional electronic health records (EHRs) and medical images [27].

Table 2: Performance of Hybrid Deep Learning Models in Healthcare Prediction

| Hybrid Model | Reported Accuracy | Reported Precision | Reported Recall | Notable Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest + Neural Network (RF + NN) | 96.81% [27] | 70.08% [27] | 90.48% [27] | Highest overall accuracy [27] |

| XGBoost + Neural Network (XGBoost + NN) | 96.75% [27] | 73.54% [27] | 96.75% [27] | Better at identifying true positives [27] |

| Autoencoder + Random Forest (Autoencoder + RF) | Not Specified | 91.36% [27] | 66.22% [27] | Highest precision, reduces data dimensionality [27] |

These models combine the strengths of different algorithms. For instance, autoencoders perform unsupervised feature extraction from high-dimensional data, which is then used for classification by robust tree-based models like Random Forest or XGBoost [27]. The workflow for such a hybrid approach is illustrated below.

Figure 2: Hybrid Predictive Model Workflow. This workflow shows the process from raw data to prediction, highlighting the feature extraction and optimization stage used in advanced models [28] [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Validating Predictive Models for Performance Indicators

This protocol is based on a retrospective study comparing three models to forecast medical performance indicators in a National Institute of Health [25].

- Objective: To identify the most accurate predictive model (Exponential Smoothing, ARIMA, or Linear Regression) for forecasting results of key performance indicators within an RBM system.

- Data Collection: Performance indicator data arranged in time series. The study analyzed 10 medical performance indicators [25].

- Model Execution:

- Exponential Smoothing (ES): Applied for its robustness with limited historical data.

- ARIMA: Formulated to capture autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) components in the time series data. The level of differentiation (I) was determined to ensure data stationarity [25].

- Linear Regression (LR): Used to model the relationship between the dependent variable (the performance indicator) and time or other independent variables.

- Validation & Analysis:

- The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was the primary metric for comparing model performance and identifying the best one [25].

- For the top-performing Linear Regression model, three key assumptions were checked:

Protocol 2: Implementing a Hybrid Deep Learning Model

This protocol outlines the methodology for developing a hybrid model, such as Autoencoder + Random Forest, for complex healthcare predictions [27].

- Objective: To leverage automated feature extraction and robust classification for predicting healthcare outcomes like disease onset.

- Data Collection: Using large-scale, often high-dimensional datasets from open-source platforms (e.g., Kaggle) or institutional EHRs. Data includes clinical variables, lab results, and demographic information [27].

- Model Execution:

- Feature Extraction: An Autoencoder (an unsupervised neural network) is trained to compress the input data and learn a reduced, meaningful representation (encoded features), effectively performing dimensionality reduction [27].

- Classification: The optimized feature set from the autoencoder is used as input to a Random Forest classifier, which makes the final prediction (e.g., disease presence or absence) [27].

- Validation & Analysis:

- Models are evaluated using standard performance metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score [27].

- The model's performance is compared against other hybrid models and traditional machine learning algorithms to demonstrate its relative strength in handling imbalanced datasets and improving predictive accuracy [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RBM Predictive Analysis

This toolkit details key methodological components and their functions for conducting predictive analytics within a healthcare RBM framework.

Table 3: Essential Analytical Toolkit for RBM Predictive Research

| Tool / Method | Function in RBM Predictive Analysis |

|---|---|

| Performance Indicators | Quantitative or qualitative variables (e.g., rates, proportions, averages) used to measure results in dimensions like effectiveness, quality, economy, and efficiency [25]. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | A key metric to identify the best predictive model by measuring the average magnitude of errors between predicted and actual values of a performance indicator [25]. |

| Time Series Analysis | The foundation for arranging and analyzing performance indicator data to generate accurate predictions for resource planning and optimization [25]. |

| Statistical Assumption Tests (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk, Breusch-Pagan) | Used to validate the core assumptions of statistical models like Linear Regression, ensuring the reliability and interpretability of the results [25]. |

| Autoencoders | A type of neural network used for unsupervised feature extraction and dimensionality reduction from high-dimensional healthcare data (e.g., EHRs), improving subsequent modeling [27]. |

| Tree-Based Models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) | Powerful classifiers that work well on structured data and can detect complex interactions, often used in ensembles or hybrids to improve predictive accuracy and robustness [27]. |

Methodologies in Action: Machine Learning, AI, and Real-World Clinical Applications

Predictive modeling has become a cornerstone of modern patient outcomes research, enabling advancements in personalized medicine and proactive healthcare management. The evolution from traditional statistical methods to sophisticated machine learning (ML) algorithms has expanded the toolkit available to researchers and clinicians. This guide provides a systematic comparison of three prominent modeling techniques—Linear Regression, Random Forest (RF), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—within the context of healthcare research. By examining their theoretical foundations, practical applications, and performance metrics across various clinical scenarios, this analysis aims to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select appropriate methodologies for their specific predictive modeling tasks.

The growing complexity of healthcare data, characterized by high dimensionality, non-linear relationships, and intricate interaction effects, necessitates modeling approaches that can capture these patterns effectively. Whereas linear regression offers simplicity and interpretability, ensemble methods like Random Forest and XGBoost provide powerful alternatives for handling complex data structures. This comparison synthesizes evidence from recent studies to objectively evaluate these techniques' relative strengths and limitations in predicting patient outcomes.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Mechanisms

Linear Regression

Linear regression establishes a linear relationship between a continuous dependent variable (outcome) and one or more independent variables (predictors). The model is represented by the equation Y = a + b × X, where Y is the dependent variable, a is the intercept, b is the regression coefficient, and X represents the independent variable[s]. For multivariable analysis, the equation extends to incorporate multiple predictors. The coefficients indicate the direction and strength of the relationship between each predictor and the outcome, providing straightforward interpretation of each variable's effect. The model's goodness-of-fit is typically assessed using R-squared, which represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables. Linear regression requires certain assumptions including linearity, normality of residuals, and homoscedasticity, which, if violated, can compromise the validity of its results.

Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble, tree-based machine learning algorithm that operates by constructing a multitude of decision trees at training time. As a bagging (bootstrap aggregating) method, it creates multiple subsets of the original data through bootstrapping and builds decision trees for each subset. A critical feature is that when building these trees, instead of considering all available predictors, the algorithm randomly selects a subset of predictors at each split, thereby decorrelating the trees and reducing overfitting. The final prediction is determined by aggregating the predictions of all individual trees, either through majority voting for classification tasks or averaging for regression problems. This ensemble approach typically results in improved accuracy and stability compared to single decision trees. Random Forest can automatically handle non-linear relationships and complex interactions between variables without requiring prior specification, making it particularly suitable for exploring complex healthcare datasets where these patterns are common but not always hypothesized in advance.

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting)

XGBoost is another ensemble tree-based algorithm that employs a gradient boosting framework. Unlike Random Forest's bagging approach, XGBoost builds trees sequentially, with each new tree designed to correct the errors made by the previous ones in the sequence. The algorithm optimizes a differentiable loss function plus a regularization term that penalizes model complexity, which helps control overfitting. XGBoost incorporates several advanced features including handling missing values, supporting parallel processing, and implementing tree pruning. The sequential error-correction approach, combined with regularization, often yields highly accurate predictions. However, this complexity can make XGBoost more computationally intensive and potentially less interpretable than simpler methods. Its performance advantages have made it particularly popular in winning data science competitions and complex prediction tasks where accuracy is paramount.

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Characteristics Comparison

| Feature | Linear Regression | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Type | Parametric | Ensemble (Bagging) | Ensemble (Boosting) |

| Model Structure | Linear equation | Multiple independent decision trees | Sequential dependent decision trees |

| Handling Non-linearity | Poor (requires transformation) | Excellent | Excellent |

| Interpretability | High | Moderate (via feature importance) | Moderate (via feature importance/SHAP) |

| Native Handling of Missing Data | No | No | Yes |

| Primary Hyperparameters | None | nestimators, maxdepth, minsamplesleaf | nestimators, learningrate, max_depth, subsample |

Comparative Performance Analysis in Healthcare Applications

Predictive Accuracy Across Clinical Domains

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of these modeling techniques in predicting patient outcomes, with performance typically measured using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, F-1 scores, and other domain-specific metrics.

In predicting attrition from diabetes self-management programs, researchers found that XGBoost with downsampling achieved the highest performance among tested models with an AUC of 0.64, followed by Random Forest, while both outperformed logistic regression. However, the generally low AUC values (ranging 0.53-0.64 across models) highlighted the challenge of predicting behavioral outcomes like program adherence, with the authors noting that "machine learning models showed poor overall performance" in this specific context despite identifying meaningful predictors of attrition.

Conversely, in predicting neurological improvement after cervical spinal cord injury, all models performed well, with XGBoost and logistic regression demonstrating comparable performance. XGBoost achieved 81.1% accuracy with an AUC of 0.867, slightly outperforming logistic regression (80.6% accuracy, AUC 0.877) and substantially surpassing a single decision tree (78.8% accuracy, AUC 0.753). This suggests that for certain clinical prediction tasks, ensemble methods can provide meaningful improvements in accuracy.

For predicting unplanned readmissions in elderly patients with coronary heart disease, XGBoost demonstrated strong performance with an AUC of 0.704, successfully identifying key clinical predictors including length of stay, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, monocyte count, blood glucose level, and red blood cell count. Similarly, in forecasting hospital outpatient volume, XGBoost outperformed both Random Forest and SARIMAX (a time-series approach) across multiple metrics including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R-squared, effectively capturing relationships between environmental factors, resource availability, and patient volume.

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across Healthcare Applications

| Clinical Application | Linear Regression/Logistic | Random Forest | XGBoost | Key Predictors Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Program Attrition | Lower performance (AUC ~0.53-0.61) | Intermediate performance | Highest performance (AUC 0.64, F-1 0.36) | Quality of life scores, DCI score, race, age, drive time to grocery store |

| Neurological Improvement (SCI) | Accuracy 80.6%, AUC 0.877 | Not reported | Accuracy 81.1%, AUC 0.867 | Demographics, neurological status, MRI findings, treatment strategies |

| Unplanned Readmission (CHD) | Not reported | Not reported | AUC 0.704 | Length of stay, comorbidity index, monocyte count, blood glucose |

| Self-Perceived Health | Not reported | AUC 0.707 | Not reported | Nine exposome factors from different domains |

| Hospital Outpatient Volume | Lower performance (benchmark) | Intermediate performance | Highest performance (lowest MAE/RMSE, highest R²) | Specialist availability, temporal variables, temperature, PM2.5 |

Interpretability and Factor Identification

Beyond pure predictive accuracy, identifying key factors driving outcomes is crucial for clinical research and intervention development. Linear regression provides direct interpretation through coefficients indicating the direction and magnitude of each variable's effect. For ensemble methods, techniques like feature importance and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values enable interpretation despite the models' complexity.

In diabetes self-management attrition prediction, SHAP analysis applied to the XGBoost model identified "health-related measures – specifically the SF-12 quality of life scores, Distressed Communities Index (DCI) score, along with demographic factors (race, age, height, and educational attainment), and spatial variables (drive time to the nearest grocery store)" as influential predictors, providing actionable insights for designing targeted retention strategies despite the model's overall modest predictive power.

Similarly, in a study of patient satisfaction drivers, Random Forest identified 'age' as the most important patient-related determinant across both registration and consultation stages, with 'total time taken for registration' and 'attentiveness and knowledge of the doctor' as the leading provider-related determinants in each respective stage. The radar charts further revealed that 'demographics' questions were most influential in the registration stage, while 'behavior' questions dominated in the consultation stage, demonstrating how ML models can identify varying factor importance across different healthcare process stages.

Methodological Protocols for Healthcare Outcome Prediction

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Robust predictive modeling requires meticulous data preprocessing. For healthcare data, this typically involves handling missing values through imputation methods (e.g., Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations - MICE), addressing class imbalance in outcomes through techniques like downsampling or upweighting, and normalizing or standardizing continuous variables. Categorical variables require appropriate encoding (e.g., one-hot encoding), and domain-specific feature engineering may incorporate temporal trends (e.g., Area-Under-the-Exposure - AUE - and Trend-of-the-Exposure - TOE for longitudinal data) or clinical composite scores.

Model Development and Hyperparameter Tuning

Optimal model performance requires appropriate hyperparameter tuning. For Random Forest, key hyperparameters include nestimators (number of trees), maxdepth (maximum tree depth), minsamplesleaf (minimum samples required at a leaf node), and minsamplessplit (minimum samples required to split an internal node). For XGBoost, essential parameters include nestimators, learningrate (step size shrinkage), maxdepth, subsample (proportion of observations used for each tree), and colsamplebytree (proportion of features used for each tree).

Systematic approaches like grid search with cross-validation (typically 5-fold or 10-fold) are recommended to identify optimal parameter combinations while mitigating overfitting. The dataset should be divided into training (typically 80%), validation (for hyperparameter tuning), and test sets (for final performance evaluation), with temporal validation for time-series healthcare data.

Model Evaluation and Interpretation

Comprehensive evaluation extends beyond single metrics to include discrimination measures (AUC, accuracy), calibration (calibration curves), and clinical utility (decision curve analysis). For healthcare applications, model interpretability is crucial, with Linear Regression providing natural interpretation, while ensemble methods require techniques like feature importance rankings, partial dependence plots, accumulated local effects plots, or SHAP values to understand variable effects and facilitate clinical adoption.

Diagram 1: Predictive Modeling Workflow in Healthcare Research

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Predictive Modeling

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Healthcare Predictive Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | Python 3.7+, R 4.0+ | Primary computational environments for model development | All studies referenced |

| Core ML Libraries | scikit-learn, XGBoost, Caret (R) | Implementation of algorithms and evaluation metrics | All studies referenced |

| Data Handling | pandas, NumPy, dplyr (R) | Data manipulation, cleaning, and preprocessing | All studies referenced |

| Visualization | Matplotlib, Seaborn, ggplot2 (R) | Creation of performance plots and explanatory diagrams | Patient satisfaction analysis, exposome study |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP, ELI5, variable importance | Explain model predictions and identify key drivers | Diabetes attrition study, CHD readmission prediction |

| Hyperparameter Tuning | GridSearchCV, RandomizedSearchCV | Systematic optimization of model parameters | Outpatient volume prediction, self-perceived health study |

Diagram 2: Algorithm Selection Framework for Healthcare Applications

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the choice between Linear Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost for patient outcomes research involves important trade-offs between interpretability, predictive accuracy, and implementation complexity. Linear regression remains valuable when interpretability is paramount and relationships are primarily linear. Random Forest provides a robust approach for exploring complex datasets with interactions and non-linearities while maintaining reasonable interpretability through feature importance metrics. XGBoost frequently achieves the highest predictive accuracy for challenging classification and regression tasks but requires careful tuning and more sophisticated interpretation methods.

The optimal model selection depends on the specific research context, including the primary study objective (explanation versus prediction), data characteristics, and implementation constraints. For clinical applications where model interpretability directly impacts adoption, the highest accuracy algorithm may not always be the most appropriate choice. Rather than seeking a universally superior algorithm, researchers should select methodologies aligned with their specific research questions, data resources, and practical constraints, while employing rigorous development and evaluation practices to ensure reliable, clinically meaningful results.

The Rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Digital Twins for Clinical Forecasting

The field of clinical forecasting is undergoing a paradigm shift with the convergence of large language models (LLMs) and digital twin technology. Digital twins—virtual representations of physical entities—when applied to healthcare, create dynamic patient models that can simulate disease progression and treatment responses [29]. The emergence of LLMs with their remarkable pattern recognition and sequence prediction capabilities has unlocked new potential for these digital replicas, enabling more accurate and personalized health trajectory forecasting [30].

This technological synergy addresses critical challenges in patient outcomes research, including handling real-world data complexities such as missingness, noise, and limited sample sizes [30]. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that require extensive data preprocessing and imputation, LLM-based digital twins can process electronic health records in their raw form, capturing complex temporal relationships across multiple clinical variables [31]. This capability is particularly valuable for drug development professionals who require predictive models that maintain the distributions and cross-correlations of clinical variables throughout forecasting periods [30].

Experimental Benchmarking: DT-GPT Versus State-of-the-Art Models

Performance Comparison Across Clinical Domains

The Digital Twin-Generative Pretrained Transformer (DT-GPT) model has emerged as a pioneering approach in this space, extending LLM-based forecasting solutions to clinical trajectory prediction [30]. In rigorous benchmarking against 14 state-of-the-art machine learning models across multiple clinical domains, DT-GPT demonstrated consistent superiority in predictive accuracy [29].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Forecasting Models Across Clinical Datasets

| Model Category | Model Name | NSCLC Dataset (Scaled MAE) | ICU Dataset (Scaled MAE) | Alzheimer's Dataset (Scaled MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM-Based | DT-GPT | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.03 |

| Gradient Boosting | LightGBM | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| Temporal Transformer | TFT | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.02 |

| Recurrent Networks | LSTM | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.66 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.04 |

| Channel-Independent LLM | Time-LLM | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.51 ± 0.04 |

| Channel-Independent LLM | LLMTime | 0.71 ± 0.07 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.53 ± 0.05 |

| Pre-trained LLM (No Fine-tuning) | Qwen3-32B | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

| Pre-trained LLM (No Fine-tuning) | BioMistral-7B | 1.03 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 1.21 ± 0.15 |

DT-GPT achieved statistically significant improvements over the second-best performing models across all datasets, with relative error reductions of 3.4% for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 1.3% for intensive care unit (ICU) patients, and 1.8% for Alzheimer's disease forecasting tasks [30]. Notably, the scaled mean absolute error (MAE) normalization by standard deviation revealed that DT-GPT's forecasting errors were consistently smaller than the natural variability present in the data, indicating robust predictive performance [30].

Zero-Shot Forecasting Capabilities

A distinctive advantage of the LLM-based approach is its capacity for zero-shot forecasting—predicting clinical variables not explicitly encountered during training [30]. This capability was rigorously tested by asking DT-GPT to predict lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level changes in NSCLC patients 13 weeks post-therapy initiation without specific training on this variable [29].

Table 2: Zero-Shot Forecasting Performance Comparison

| Model Type | LDH Prediction Accuracy | Training Requirement | Variables Handled |

|---|---|---|---|

| DT-GPT (Zero-Shot) | 18% more accurate in specific cases | No specialized training | Any clinical variable |

| Traditional ML Models | Baseline accuracy | Required training on 69 clinical variables | Limited to trained variables |

| Channel-Independent Models | Limited zero-shot capability | Per-variable training needed | Limited extrapolation |

The zero-shot capability demonstrates that LLM-based clinical forecasting models can extract generalized patterns from clinical data that transfer to unpredicted tasks, significantly reducing the need for retraining when new forecasting needs emerge in drug development pipelines [29].

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols and Architectures

DT-GPT Model Architecture and Training Methodology

The DT-GPT framework builds upon a pre-trained LLM foundation, specifically adapting the 7-billion-parameter BioMistral model for clinical forecasting tasks [30]. The methodological approach involves several key components:

Data Encoding and Representation: Electronic Health Records (EHRs) are encoded without requiring data imputation or normalization, preserving the raw clinical context. The model processes multivariate time series data representing patient clinical states over time, maintaining channel dependence to capture inter-variable biological relationships [30].

Training Protocol: The model undergoes supervised fine-tuning on curated clinical datasets. For the NSCLC dataset (16,496 patients), the model learned to predict six laboratory values weekly for up to 13 weeks post-therapy initiation using all pre-treatment data. For ICU forecasting (35,131 patients), the model predicted respiratory rate, magnesium, and oxygen saturation over 24 hours based on the previous 24-hour history. The Alzheimer's dataset (1,140 patients) involved forecasting cognitive scores (MMSE, CDR-SB, ADAS11) over 24 months at 6-month intervals using baseline measurements [30].

Evaluation Framework: Performance was assessed using scaled mean absolute error (MAE) with z-score normalization to enable comparison across variables. All comparisons were performed on unseen patient cohorts to ensure robust generalizability assessment [30].

Comparative Model Architectures

The benchmarking analysis included diverse architectural approaches:

- Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT): Attention-based architecture that efficiently learns temporal relationships while maintaining interpretability [30].

- Channel-Independent Models (Time-LLM, LLMTime, PatchTST): Process each time series separately without modeling interactions, limiting effectiveness for biologically correlated clinical variables [30].

- Traditional Sequential Models (LSTM, RNN): Capture temporal dependencies but struggle with long-range forecasting and heterogeneous clinical data [30].

Diagram 1: DT-GPT Clinical Forecasting Architecture. The architecture demonstrates the flow from raw EHR data through structured representation, LLM processing with cross-attention mechanisms, to final forecasting and interpretability outputs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for LLM-Driven Clinical Digital Twins

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Datasets | MIMIC-IV (ICU), Flatiron Health NSCLC, ADNI | Benchmark validation across clinical domains | Data heterogeneity, missingness, and ethical compliance [30] |

| Base LLM Architectures | BioMistral, ClinicalBERT, GatorTron | Foundation model capabilities | Domain-specific pre-training enhances clinical concept recognition [30] |

| Multimodal Fusion Engines | Transformer Cross-Attention Mechanisms | Integrate imaging, genomics, clinical records | Weighted feature importance (e.g., vascular structures: 0.68 weight) [32] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Scaled MAE, Distribution Maintenance, Cross-Correlation | Assess forecasting accuracy and clinical validity | Error magnitude relative to natural variable variability [30] |

| Privacy-Preserving Training | Federated Learning, Blockchain, Quantum Encryption | Enable multi-institutional collaboration without data sharing | HIPAA/GDPR compliance; resistance to quantum computing threats [32] [33] |

| Interpretability Interfaces | Conversational Chatbots, SHAP Value Visualizations | Model explainability for clinical adoption | Interactive querying of prediction rationale [29] |

Implementation Workflow: From Data to Digital Twin Forecasts

Diagram 2: Digital Twin Clinical Forecasting Workflow. The end-to-end process from multi-modal data acquisition through digital twin initialization, intervention simulation, forecasting, and clinical validation creates a continuous learning cycle.

The implementation of LLM-driven digital twins follows a structured workflow that transforms heterogeneous clinical data into actionable forecasts. The process begins with multi-modal data acquisition from electronic medical records, genomic sequencing, wearable sensors, and medical imaging [32]. This diverse data stream undergoes real-time fusion using transformer-based cross-attention mechanisms that dynamically weight feature importance based on clinical context [33].

Following data fusion, patient-specific digital twins are initialized by encoding individual clinical profiles into the LLM framework [29]. These virtual replicas serve as the foundation for simulating various intervention scenarios, from medication adjustments to surgical procedures, enabling comparative outcome prediction [32] [33]. The forecasting phase leverages the LLM's sequence prediction capabilities to generate multi-variable clinical trajectories across short (24-hour), medium (13-week), and long-term (24-month) horizons [30].

Finally, the continuous validation loop compares predicted trajectories with actual patient outcomes, creating a self-improving system that refines its forecasting capabilities through ongoing learning [30]. This closed-loop approach is particularly valuable for drug development, where predicting patient responses across diverse populations can significantly accelerate clinical trial design and therapeutic optimization [29].

Future Directions and Research Applications

The integration of LLMs with digital twin technology represents a transformative approach to clinical forecasting with profound implications for patient outcomes research. By demonstrating superior performance against state-of-the-art alternatives across multiple clinical domains, while offering unique capabilities such as zero-shot forecasting, LLM-based systems like DT-GPT are poised to reshape how researchers and drug development professionals approach predictive modeling [30] [29].

The technology's ability to maintain variable distributions and cross-correlations while processing raw, incomplete clinical data addresses fundamental challenges in real-world evidence generation [30]. Furthermore, the incorporation of interpretability interfaces and conversational functionality bridges the explainability gap that often impedes clinical adoption of complex AI systems [29].

As these technologies mature, their application across the drug development lifecycle—from target identification and clinical trial simulation to post-market surveillance—promises to enhance the efficiency and personalization of therapeutic development [29]. The emerging capability to generate synthetic yet clinically valid patient trajectories may also address data scarcity issues while maintaining privacy compliance [32]. Through continued refinement and validation, LLM-driven digital twins are establishing a new paradigm for predictive analytics in clinical research and patient outcomes assessment.