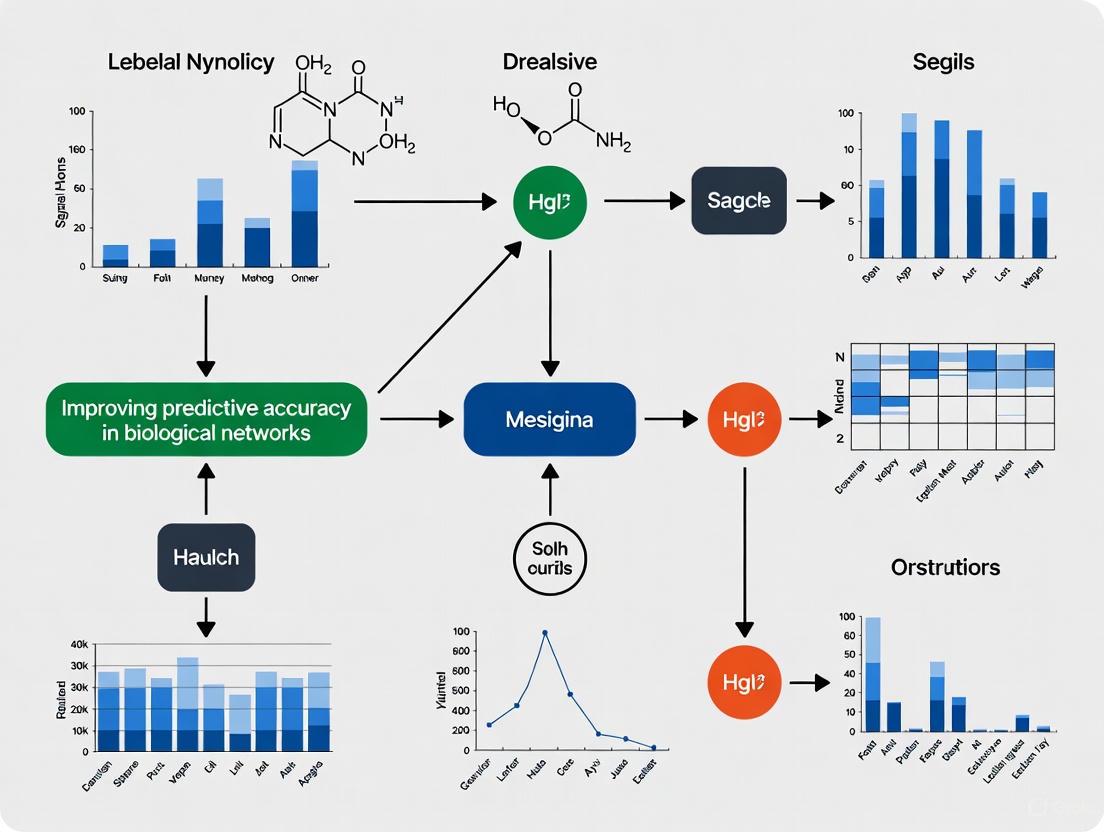

Advancing Predictive Accuracy in Biological Networks: Integrating AI, Multi-Omic Data, and Causal Inference for Biomedical Discovery

Predictive modeling of biological networks is fundamental to understanding complex diseases, accelerating drug discovery, and enabling precision medicine.

Advancing Predictive Accuracy in Biological Networks: Integrating AI, Multi-Omic Data, and Causal Inference for Biomedical Discovery

Abstract

Predictive modeling of biological networks is fundamental to understanding complex diseases, accelerating drug discovery, and enabling precision medicine. This article synthesizes the latest computational advances aimed at improving the accuracy of these models. We explore foundational concepts in gene regulatory and protein interaction networks, then delve into cutting-edge methodologies including graph neural networks, knowledge graph embeddings, and multi-task learning. The review addresses key challenges such as data heterogeneity, model interpretability, and causal inference, while providing comparative analysis of validation frameworks and performance benchmarks. For researchers and drug development professionals, this offers a comprehensive technical guide for selecting, optimizing, and validating network-based predictive models to derive robust biological insights and therapeutic hypotheses.

The Landscape of Biological Networks: From Graph Theory to Functional Genomics

Biological networks are computational models that represent complex biological systems as interconnected components. They are foundational for understanding interactions within cells, tissues, and whole organisms, and are crucial for improving the predictive accuracy of models in disease research and drug development [1]. In these networks, nodes represent biological entities (such as genes, proteins, or metabolites), and edges represent the physical, regulatory, or functional interactions between them [2] [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of a biological network? The core components are nodes and edges [3].

- Nodes represent biological entities like genes, proteins, or metabolites.

- Edges represent interactions or relationships between these entities, which can be directed (e.g., gene regulation) or undirected (e.g., protein-protein interactions), and may be weighted to indicate the strength or confidence of the interaction.

Q2: My network visualization is cluttered and unreadable. What are my options? Clutter often arises from inappropriate layouts for your network's size and purpose [1]. Consider these alternatives:

- For small to medium networks: Use force-directed layouts (e.g., Fruchterman-Reingold), which simulate a physical system to distribute nodes evenly [3].

- For large, dense networks: Use an adjacency matrix, where rows and columns represent nodes and filled cells represent edges. This avoids the edge crossing problem of node-link diagrams [1].

- For hierarchical or directed networks: Use hierarchical layouts that arrange nodes in layers to show directionality and upstream/downstream relationships [3].

Q3: How can I ensure my network figure is accessible to readers with color vision deficiencies?

Always use color-blind friendly palettes and ensure sufficient contrast [3]. For any text within a node, explicitly set the fontcolor to have a high contrast against the node's fillcolor. WCAG guidelines recommend a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for standard text [4] [5].

Q4: I am getting poor results from a network alignment tool. What is a common preprocessing error? A common error is a lack of nomenclature consistency across networks [2]. Different databases use various names (synonyms) for the same gene or protein. Before alignment, normalize all node identifiers using authoritative sources like HGNC for human genes or UniProt for proteins. Tools like BioMart or the MyGene.info API can automate this mapping [2].

Q5: What file formats are best for storing and analyzing network data? The choice depends on your network's size and analysis tools [2].

| Format | Best For | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Edge List | Large, sparse networks (e.g., PPI networks) [2] | Simple, compact, and memory-efficient [2]. |

| Adjacency Matrix | Small, dense networks; Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) [2] | Easy to query connections; comprehensive representation [2]. |

| GraphML | Most biological networks [3] | Flexible XML-based format that can store network structure and attributes [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent node mapping in cross-species network analysis.

- Description: Nodes that are biologically equivalent are not recognized as matches during network alignment due to inconsistent naming conventions [2].

- Solution: Implement a robust identifier mapping workflow.

- Extract all gene/protein identifiers from your input networks.

- Use a programmatic tool like BioMart (Ensembl) or the UniProt ID mapping service to convert all identifiers to a standardized nomenclature (e.g., HGNC-approved symbols) [2].

- Replace the original identifiers in your network files with the standardized names.

- Remove any duplicate nodes or edges that result from the merging of synonyms [2].

Problem: Network figure fails to communicate the intended biological message.

- Description: The final visualization is visually confusing and does not highlight the key findings of the experiment [1].

- Solution: Follow a purpose-driven design process.

- Define the message: Before creating the figure, write down the exact point you want the caption to convey [1].

- Choose an encoding: Select visual channels to reinforce the message.

- Use layering: Annotate key nodes or subnetworks to draw the reader's attention to the most important parts of the network [1].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Standardized Workflow for Constructing a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network This protocol ensures reproducibility in building a network from raw data.

1. Data Acquisition:

- Obtain PPI data from one or more public databases (e.g., STRING, BioGRID).

- Download data in a standard format, preferably a tab-separated edge list.

2. Data Cleaning and Normalization:

- Filter interactions based on a confidence score (e.g., a combined score > 0.7 in STRING) to remove low-quality data [3].

- Normalize all protein identifiers to a single type (e.g., UniProt IDs) using the ID mapping tool provided by the database [2].

3. Network Construction and Visualization:

- Import the processed edge list into a network analysis tool like Cytoscape [3].

- Apply a force-directed layout (e.g., Prefuse Force Directed) for an initial visualization.

- Map experimental data (e.g., gene expression fold-change from RNA-seq) to node color using a diverging color palette (e.g., blue-white-red). Map node degree to node size to highlight hubs [3].

Table 1: Key Reagent Solutions for Network Biology Experiments

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cytoscape | An open-source software platform for visualizing, analyzing, and modeling molecular interaction networks [3]. |

| STRING Database | A database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions, providing a critical data source for network construction [1]. |

| HGNC (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee) | Provides standardized gene symbols for human genes, essential for ensuring node name consistency across datasets [2]. |

| UniProt ID Mapping | A service to map between different protein identifier types, crucial for data integration and preprocessing [2]. |

| BioMart | A data mining tool that allows for batch querying and conversion of gene identifiers across multiple species [2]. |

Network Visualization and Diagramming

The following diagrams were generated using Graphviz DOT language, adhering to the specified color and contrast rules. The palette is limited to: #4285F4 (blue), #EA4335 (red), #FBBC05 (yellow), #34A853 (green), #FFFFFF (white), #F1F3F4 (light gray), #202124 (dark gray), #5F6368 (gray). All text has a high contrast against its node's background color.

Diagram 1: Basic SBGN-Conformant Signaling Pathway

This diagram depicts a fundamental signaling pathway using standardized symbols from the Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) [6]. It shows a macromolecule (e.g., a kinase) catalyzing the transformation of one simple chemical into another, which is then inhibited by a different macromolecule.

Diagram 2: Data Preprocessing for Network Alignment

This workflow outlines the critical data preparation steps required to ensure accurate network alignment, highlighting the importance of identifier normalization [2].

Diagram 3: Common Biological Network Layouts

This diagram visually compares three primary layout algorithms used in network visualization, helping users select the most appropriate one for their data [1] [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective computational methods for identifying key differences between biological networks from different conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased tissue)?

A1: Contrast subgraph identification is a powerful method for this purpose. Unlike global network comparison techniques, contrast subgraphs are "node-identity aware," pinpointing the specific genes or proteins whose connectivity differs most significantly between two networks, such as those from different disease subtypes. These subgraphs consist of sets of nodes that form densely connected modules in one network but are sparsely connected in the other. This method has been successfully applied, for instance, to identify gene modules with distinct co-expression patterns between basal-like and luminal A breast cancer subtypes, revealing differentially connected immune and extracellular matrix processes [7].

Q2: How can I predict novel drug-target interactions (DTIs) when the available dataset has very few known interactions (positive samples)?

A2: This challenge, known as extreme class imbalance (positive/negative ratios can be worse than 1:100), can be addressed with advanced contrastive learning and strategic sampling. We recommend using models that incorporate:

- Collaborative Contrastive Learning (CCL): This learns consistent drug/target representations across multiple biological networks (e.g., similarity networks, interaction networks), ensuring the fused embeddings are robust [8].

- Adaptive Self-Paced Sampling Strategy (ASPS): This dynamically selects the most informative negative samples for the contrastive learning process during training, which improves model generalization and performance on imbalanced data [8].

- Cross-view Contrastive Learning: Frameworks like GHCDTI use this to align node representations from different views (e.g., topological and frequency-domain), enhancing generalization under data imbalance [9].

Q3: My protein-protein interaction (PPIN) network is static, but I need to understand dynamic properties like sensitivity. How can I achieve this?

A3: You can infer dynamic properties like sensitivity (how a change in an input protein's concentration affects an output protein) directly from static PPINs using Deep Graph Networks (DGNs). The workflow involves:

- Training Data Generation: Use Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) simulations on known Biochemical Pathways (BPs) to compute sensitivity values for protein pairs.

- Network Annotation: Map these sensitivity annotations back to the corresponding nodes and subgraphs in a large-scale PPIN (e.g., using resources like BioGRID and UniPROT) to create a dynamic PPIN (DyPPIN) dataset.

- Model Training and Inference: Train a DGN model on the DyPPIN dataset. Once trained, this model can predict sensitivity for any input/output protein pair directly from the PPIN's structure, bypassing the need for costly simulations or detailed kinetic parameters [10].

Q4: Are there supervised learning methods for gene regulatory network (GRN) reconstruction that outperform classic unsupervised approaches?

A4: Yes, supervised learning methods generally outperform unsupervised ones for GRN reconstruction. A state-of-the-art approach is GRADIS (GRaph Distance profiles). Its methodology involves creating feature vectors for Transcription Factor (TF)-gene pairs based on graph distance profiles from a Euclidean-metric graph constructed from clustered gene expression data. These features are then used to train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier to discriminate between regulating and non-regulating pairs. This method has been validated to achieve higher accuracy (measured by AUROC and AUPR) than other supervised and unsupervised approaches on benchmark data from E. coli and S. cerevisiae [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Predictive Accuracy in Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Models

Problem: Your DTI prediction model is underperforming, showing low accuracy and poor generalization on unseen data.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring multi-network relationships. | Implement Collaborative Contrastive Learning (CCL). | Learns fused, consistent representations of drugs/targets from multiple source networks (e.g., similarity, interaction), capturing complementary biological information [8]. |

| Simple negative sampling. | Employ an Adaptive Self-Paced Sampling Strategy (ASPS). | Dynamically selects informative negative samples during contrastive learning, preventing model overfitting and improving robustness to class imbalance [8]. |

| Using only static protein structures. | Integrate a multi-scale wavelet feature extraction module (e.g., Graph Wavelet Transform). | Captures both conserved global patterns and localized dynamic variations in protein structures, providing a richer representation of conformational flexibility [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Collaborative Contrastive Learning with ASPS for DTI [8]

- Input Data: Prepare multiple networks for drugs and targets (e.g., drug-drug similarity, target-target similarity, known DTI network).

- Initial Embedding: Use Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to learn initial embeddings for drugs and targets from their respective graph structures.

- Collaborative Contrastive Learning:

- Input the initial embeddings into a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to learn fused, consistent representations.

- Apply a contrastive loss function to ensure the fused representation is consistent with its view-specific representations.

- Adaptive Self-Paced Sampling:

- Calculate node similarities within individual networks.

- Select challenging negative sample pairs based on these similarities and the fused representations.

- Prediction: Feed the final consistent representations into a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) decoder to predict potential DTIs.

Issue 2: High False Positive Rate in Protein Complex Prediction from PPI Networks

Problem: Your algorithm for detecting protein complexes in a PPI network is identifying many dense subgraphs that are not validated biological complexes.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on density. | Use a supervised method based on Emerging Patterns (EPs) (e.g., ClusterEPs). | Discovers contrast patterns (EPs) that combine multiple topological properties (not just density) to sharply distinguish true complexes from random subgraphs [12]. |

| Lack of interpretability. | Employ Emerging Patterns (EPs). | Provides clear, conjunctive rules (e.g., {meanClusteringCoeff ≤ 0.3, 1.0 < varDegreeCorrelation ≤ 2.80}) explaining why a subgraph is or is not predicted as a complex [12]. |

Experimental Protocol: Protein Complex Prediction with ClusterEPs [12]

- Feature Extraction: For each known true complex (positive) and generated random subgraph (negative) in your training PPI network, calculate a feature vector. Features include topological properties like density, clustering coefficient, degree correlation variance, etc.

- Emerging Pattern (EP) Mining: Apply a data mining algorithm to discover EPs—patterns of feature values that occur frequently in one class (complexes) but rarely in the other (non-complexes).

- Score Definition: Define an EP-based clustering score for any candidate subgraph. This score aggregates the support from all EPs that match the subgraph's features.

- Complex Identification: From a set of seed proteins, grow potential complexes by iteratively adding/removing proteins and updating the EP-based score. Subgraphs with a high score are predicted as complexes.

Performance Comparison of Key Methods

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of DTI Prediction Models

| Model / Method | Key Feature | AUROC | AUPR | Dataset / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL-ASPS [8] | Collaborative Contrastive Learning & Adaptive Sampling | — | — | Established DTI dataset; outperforms state-of-the-art baselines. |

| GHCDTI [9] | Graph Wavelet Transform & Multi-level Contrastive Learning | 0.966 ± 0.016 | 0.888 ± 0.018 | Benchmark datasets; includes 1,512 proteins & 708 drugs. |

Table 2: Performance of Complex Prediction and GRN Reconstruction Methods

| Method / Approach | Network Type | Key Metric & Performance | Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClusterEPs [12] | PPI (Complex Prediction) | Higher max matching ratio vs. 7 unsupervised methods. | Yeast PPI datasets (MIPS, SGD). |

| GRADIS [11] | Gene Regulatory | Higher accuracy (AUROC, AUPR) vs. state-of-the-art supervised/unsupervised methods. | DREAM4 & DREAM5 challenges; E. coli & S. cerevisiae. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Datasets, Tools, and Software for Biological Network Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA & METABRIC [7] | Dataset (Genomics) | Provide large-scale gene expression data for building condition-specific co-expression networks (e.g., cancer subtypes). |

| CPTAC [7] | Dataset (Proteomics) | Provides proteomic data for constructing protein-based co-expression networks and comparing them to transcriptomic data. |

| BioModels Database [10] | Dataset (Pathways) | Source of curated, simulation-ready biochemical pathways for computing dynamical properties like sensitivity. |

| DyPPIN Dataset [10] | Annotated PPIN | A PPIN annotated with sensitivity properties, used for training models to predict dynamics from network structure. |

| ClusterEPs Software [12] | Software Tool | Implements the Emerging Patterns-based method for supervised prediction of protein complexes from PPI networks. |

| Cytoscape [1] | Software Tool | Open-source platform for complex network visualization and analysis, offering a rich selection of layout algorithms. |

Next Steps and Advanced Techniques

For researchers looking to push the boundaries further, consider these advanced integrative approaches:

- Multi-scale Wavelet Analysis for Proteins: The GHCDTI model uses Graph Wavelet Transform (GWT) to decompose protein structure graphs into frequency components. Low-frequency filters capture conserved global patterns (e.g., protein domains), while high-frequency filters highlight localized variations (e.g., dynamic binding sites), providing a more nuanced representation for DTI prediction [9].

- Cross-Species Complex Prediction: The ClusterEPs method demonstrates that a model trained on protein complexes from one species (e.g., yeast) can be effectively applied to predict novel complexes in another species (e.g., human), greatly expanding the potential for discovery [12].

- From Static Networks to Dynamic Predictions: The DyPPIN-DGN pipeline shows that the static structure of a PPIN contains enough information to infer dynamic properties. This allows for large-scale sensitivity analysis that would be computationally prohibitive using traditional simulation methods [10].

Within the framework of Improving Predictive Accuracy in Biological Networks Research, selecting the appropriate transcriptomic tool is paramount. Microarrays, RNA-seq, and single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) each provide distinct layers of insight, from targeted gene expression profiling to whole-transcriptome analysis at population or single-cell resolution. The choice of technology directly influences the granularity of the data and the robustness of the resulting biological network models. This guide addresses common technical challenges and provides troubleshooting advice for researchers navigating these complex methodologies.

Technical Comparison of Transcriptomic Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each major transcriptomic profiling technology.

Table 1: Comparison of Transcriptomic Profiling Technologies

| Feature | Microarrays | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Hybridization-based detection using predefined probes | High-throughput sequencing of cDNA | High-throughput sequencing of cDNA from individual cells |

| Resolution | Population-averaged | Population-averaged | Single-cell |

| Throughput | High (number of samples) | High (number of samples) | High (number of cells per sample) |

| Dynamic Range | Limited | Extremely broad [13] | Broad |

| Prior Knowledge Required | Yes (probe design) | No (can detect novel transcripts) [13] | No (can detect novel features) [14] |

| Primary Challenge | Low sensitivity and small dynamic range [14] | Masks cellular heterogeneity [14] [15] | Perceived higher cost, specialized analysis required [14] |

| Ideal Application | Cost-effective, large-scale studies of known targets [14] | Discovery-driven research, quantifying expression without prior knowledge [13] | Identifying rare cell types, cell states, and cellular heterogeneity [14] [16] [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

General Experimental Design

Q: How do I choose between a microarray, bulk RNA-seq, and single-cell RNA-seq for my study?

The choice hinges on your research question and the biological scale of the phenomenon you are studying.

- Use Microarrays when your goal is to profile the expression of a predefined set of genes (e.g., a pathway-focused panel) across a large number of samples in a cost-effective manner [14].

- Use Bulk RNA-seq when you need a comprehensive, discovery-driven view of the transcriptome for a tissue or population of cells, allowing you to detect novel transcripts, gene fusions, and splicing variants without prior sequence knowledge [13].

- Use Single-Cell RNA-seq when your objective is to deconvolve cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell populations, discover novel cell types or states, or reconstruct developmental trajectories [14] [16] [15]. This is crucial for building accurate cell-level biological networks.

Q: What are the key sample quality considerations for these assays?

RNA integrity is critical for all methods. For RNA-seq and scRNA-seq, extracted RNA must be purified and free of contaminants [13].

- Bulk RNA-seq: Follow the input quantity guidelines of your selected library prep kit. For example, Illumina Stranded mRNA workflows typically require 25 ng to 1 µg of total RNA [13].

- scRNA-seq: The technology has advanced to be compatible with a wider range of sample types, including fresh tissue, frozen tissue, fixed whole blood, and even Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue, though protocol optimization may be required [14].

Technology-Specific Challenges

Q: Our bulk RNA-seq data seems to miss important biological signals. What could be the issue?

This is a classic limitation of bulk sequencing. The population-averaged data can mask the presence of rare but biologically critical cell subtypes [14] [15]. For instance, a treatment-resistant subpopulation of cancer cells may be undetectable in a bulk RNA-seq profile of an entire tumor [14]. If cellular heterogeneity is suspected, supplementing your study with scRNA-seq is the most effective way to uncover these hidden signals.

Q: We are new to single-cell RNA-seq and are concerned about the cost and data analysis complexity. What are our options?

This is a common concern, but the landscape has improved significantly.

- Cost: The perception that scRNA-seq is prohibitively expensive is often outdated. Platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium system offer per-sample costs that can be as low as $415 USD, making it more accessible [14].

- Workflow Complexity: Commercial platforms now provide optimized, semi-automated protocols that minimize hands-on time and improve reproducibility [14].

- Data Analysis: A major hurdle for newcomers has been alleviated by the development of user-friendly, often free, analysis software. For example, 10x Genomics provides cloud-based analysis pipelines and visualization tools that require no bioinformatics expertise to get started [14].

Q: Can we integrate data from older microarray studies with newer RNA-seq datasets?

Yes, data integration is possible and can be powerful. For example, one study identified key histone modification genes in spermatogonial stem cells by integrating microarray and scRNA-seq data [17]. However, this process requires careful bioinformatic normalization and batch correction to account for the fundamental technological differences between hybridization-based and sequencing-based measurements.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Integrating Microarray and scRNA-seq Data to Identify Key Regulatory Genes

This methodology outlines how legacy and modern data types can be combined for a systems biology approach [17].

- Data Collection: Obtain microarray data (e.g., from public repositories like GEO) and generate or source complementary scRNA-seq data from similar sample types.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) between your cell type of interest (e.g., spermatogonial stem cells) and a control (e.g., fibroblasts) from the microarray data.

- Validation with scRNA-seq: Map the expression of the identified DEGs onto the scRNA-seq dataset to confirm their specific expression in the relevant cell subpopulations.

- Network and Enrichment Analysis:

- Construct a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network using the DEGs.

- Perform Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., KEGG) to identify key biological processes.

- Use Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to find modules of co-expressed genes related to a trait like cellular aging.

- Biological Interpretation: Integrate findings to build a coherent model. For example, the integrated analysis revealed genes like KDM5B and SIN3A as key regulators in chromatin remodeling within stem cells [17].

Protocol: A Standard scRNA-seq Workflow for Cellular Heterogeneity Analysis

This is a generalized workflow for a scRNA-seq study [16].

- Single-Cell Isolation: Create a single-cell suspension from your tissue of interest using mechanical and enzymatic digestion (e.g., with collagenase and dispase). The viability and quality of the single-cell suspension are critical [18] [16].

- Single-Cell Partitioning and Library Prep: Use a commercial platform (e.g., droplet-based systems like 10x Genomics Chromium) to isolate single cells, perform cell lysis, reverse transcription, and barcode cDNA from each cell.

- Sequencing: Pool the barcoded libraries and sequence on a high-throughput NGS platform.

- Computational Data Analysis:

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells based on metrics like the number of genes detected per cell and mitochondrial read percentage.

- Normalization and Scaling: Adjust counts for sequencing depth and regress out sources of technical variation.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Use techniques like PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP to visualize cells in 2D/3D and group them into clusters based on transcriptomic similarity.

- Cell Type Annotation: Identify cluster identity using known marker genes.

- Downstream Analysis: Perform differential expression, trajectory inference, or ligand-receptor interaction analysis to extract biological insights.

Essential Visualizations

Diagram: scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a standard single-cell RNA sequencing experiment, from tissue to data analysis.

Diagram: KIT Signaling Pathway in Spermatogonial Stem Cell Differentiation

This diagram summarizes a key signaling pathway identified in spermatogonial stem cell research, which can be investigated using these transcriptomic methods [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Transcriptomic Profiling Experiments

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type IV | Enzymatic digestion of tissues to generate single-cell suspensions. | Digestion of mouse testicular tissue for spermatogonial stem cell isolation [18] [17]. |

| DNase | Degrades genomic DNA during tissue digestion to prevent clumping and ensure a clean single-cell suspension. | Used in conjunction with collagenase and dispase for testicular cell preparation [18] [17]. |

| Oligo(dT) Beads/Magnetic Beads | Selection of polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA for library preparation. | Key for mRNA-seq library prep kits (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep) to enrich for mRNA [13]. |

| Poly[T] Primers | Primers for reverse transcription that specifically target the poly-A tail of mRNA molecules. | Used in scRNA-seq protocols to specifically reverse transcribe mRNA and avoid ribosomal RNA [16]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules before PCR amplification. | Allows for accurate digital counting of transcripts and correction for amplification bias in scRNA-seq [16]. |

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Antibodies | Detection of specific cell surface or intracellular proteins via flow cytometry or immunofluorescence. | Used for immunocytochemical validation of stem cell markers like OCT4 and NANOG [18]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my model perform well on training data but poorly on real-world biological networks?

This is often caused by target link inclusion, a common pitfall where the edges you are trying to predict are accidentally included in the graph used for training your model [19].

- The Problem: This practice creates three main issues: (I1) overfitting, where the model memorizes the training graph rather than learning generalizable patterns; (I2) distribution shift, where the model is trained on a graph that is structurally different from the test graph; and (I3) implicit test leakage, which artificially inflates performance metrics during evaluation and does not reflect real-world deployment scenarios [19].

- The Solution: Implement a rigorous data splitting protocol. Use a framework like SpotTarget, which systematically excludes edges incident to low-degree nodes during training and excludes all test edges from the graph at test time to better mimic real-world prediction tasks [19].

FAQ 2: When analyzing my network, should I always use the most complex machine learning model available?

Not necessarily. In network inference, simpler models can often outperform more complex ones, especially as network size and complexity increase [20].

- The Problem: Complex models like Random Forests can be prone to overfitting on noisy biological data and may have lower generalization capabilities on larger, more complex networks [20].

- The Solution: Benchmark simpler models like Logistic Regression against more complex alternatives. Research has shown that Logistic Regression can achieve perfect accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores on certain synthetic network tasks where Random Forest performance drops to around 80% accuracy [20]. Always select your model based on the specific characteristics of your network and the inference task.

FAQ 3: My prediction values are highly correlated with real data, but they still seem systematically off. How can I improve alignment?

You may be optimizing for the wrong metric. Traditional methods like least squares minimize average error but do not specifically ensure predictions align with the 45-degree line of perfect agreement [21].

- The Problem: A high Pearson correlation coefficient does not guarantee that your predictions match the actual values; it only measures the strength of a linear relationship, which could be at the wrong slope or offset [21].

- The Solution: Consider using the Maximum Agreement Linear Predictor (MALP). This technique maximizes the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC), which specifically measures how closely data points align with the line of perfect agreement (the 45-degree line on a scatter plot) [21]. This is particularly valuable when the goal is a direct match to real-world measurements, such as translating readings between different biomedical instruments [21].

FAQ 4: The graphical representations of my network pathways are difficult to interpret. How can I improve clarity?

Poor visualization can hinder the interpretation of complex biological networks. A key factor is ensuring sufficient visual contrast.

- The Problem: Low contrast between graphical objects (like lines and shapes in a pathway diagram) and their background makes them difficult to distinguish, especially for individuals with low vision or color deficiencies. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) recommend a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 for user interface components and graphical objects [22] [23].

- The Solution: Use a color contrast checker to verify your visualizations. For any node containing text, explicitly set the text color to have high contrast against the node's background color. The following workflow diagram demonstrates these principles.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Models on Network Inference Tasks This table summarizes key findings from a benchmark study evaluating machine learning models on synthetic networks of varying sizes [20].

| Network Size (Nodes) | Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Logistic Regression | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 100 | Random Forest | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| 500 | Logistic Regression | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 500 | Random Forest | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| 1000 | Logistic Regression | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1000 | Random Forest | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

Protocol 1: Rigorous GNN Training for Link Prediction This protocol is designed to avoid the pitfalls of target link inclusion [19].

- Graph Preparation: Construct your graph ( G = (V, E) ), where ( V ) is the set of nodes (e.g., proteins) and ( E ) is the set of known edges (e.g., interactions).

- Data Splitting: Split the set of edges ( E ) into training ( E{train} ) and test ( E{test} ) sets. The test set should represent the future, unknown links you want to predict.

- Create Training Graph: For training, create a graph ( G{train} = (V, E{train}) ). To address low-degree nodes, the SpotTarget framework further excludes a training edge if it is incident to at least one low-degree node [19].

- Create Test Graph: For evaluation, create a graph ( G{test} = (V, E{train}) ). Crucially, the test edges ( E_{test} ) must not be included in this graph to prevent leakage and simulate a real-world scenario [19].

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train your GNN model (e.g., a Graph Convolutional Network) on ( G{train} ) and evaluate its ability to predict the held-out edges in ( E{test} ) using ( G_{test} ).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Predictive Agreement with MALP This methodology uses a novel approach to achieve closer alignment with real-world values [21].

- Data Collection: Gather paired datasets of measured values (e.g., Stratus OCT vs. Cirrus OCT eye scan measurements, or body measurements vs. body fat percentage) [21].

- Model Fitting: Apply the Maximum Agreement Linear Predictor (MALP) to the data. The goal of MALP is to maximize the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC), defined as: ( \rhoc = \frac{2 \sigma{xy}}{\sigmax^2 + \sigmay^2 + (\mux - \muy)^2} ) where ( \mux ) and ( \muy ) are the means, and ( \sigmax^2 ) and ( \sigmay^2 ) are the variances of the predicted and actual values, respectively [21].

- Performance Comparison: Compare the performance of MALP against a traditional least-squares regression model. Evaluate using both CCC (where MALP should excel) and mean squared error (where least squares may have a slight advantage) [21].

- Interpretation: Use MALP when the primary research goal is to achieve the highest possible agreement between predictions and actual values, even if it comes at a slight cost to the average error.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

GNN Link Prediction Workflow

Pitfalls of Target Link Inclusion

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for Network Research

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) | Software Library | Provides efficient tools for building Graph Neural Networks and integrates with deep learning frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow [24]. |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Algorithm | A type of GNN that operates directly on a graph, leveraging neighborhood information to learn powerful node embeddings for tasks like link prediction [24]. |

| Ciao & Epinions Datasets | Benchmark Data | Represent real-world user-item interactions and trust relationships; used for validating social recommendation and link prediction models [24]. |

| Stochastic Block Model (SBM) | Synthetic Network Model | Generates graphs with a planted community structure; useful for benchmarking community detection algorithms and testing model robustness [20]. |

| Barabási-Albert (BA) Model | Synthetic Network Model | Generates scale-free networks with hub-dominated structures, mimicking the properties of many real-world biological and social networks [20]. |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) | Evaluation Metric | Measures the agreement between two variables (e.g., predictions and actual values) by assessing their deviation from the 45-degree line of perfect concordance [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: What is the primary purpose of benchmarks like DREAM or CausalBench?

These benchmark challenges provide a standardized and objective framework to evaluate computational methods on common ground-truth datasets. Their primary purpose is to rigorously assess the performance, strengths, and limitations of different algorithms, which is crucial for advancing the field. For instance, the DREAM challenges are instrumental for harnessing the wisdom of the broader scientific community to develop computational solutions to biomedical problems [25]. Similarly, CausalBench was created to revolutionize network inference evaluation by providing real-world, large-scale single-cell perturbation data, moving beyond synthetic benchmarks that may not reflect real-world performance [26].

FAQ: I obtained a high-performance score on a synthetic benchmark. Will my method perform well on real biological data?

Not necessarily. Performance on synthetic data does not always translate to real-world scenarios. A key finding from the CausalBench evaluation was that methods which performed well on synthetic benchmarks did not necessarily outperform others on real-world data. Moreover, contrary to observations on synthetic benchmarks, methods using interventional information did not consistently outperform those using only observational data in real-world settings [26]. It is essential to validate methods on benchmarks that use real biological data.

FAQ: Why does my network inference method have high precision but low recall?

This is a common trade-off in network inference. Methods often have to balance between being highly specific (high precision) and covering a large portion of the true interactions (high recall). An evaluation of multiple state-of-the-art methods on CausalBench clearly highlighted this inherent trade-off. Some methods achieved high precision while discovering a lower percentage of interactions, whereas others, like GRNBoost, achieved high recall but at the cost of lower precision [26]. The "best" balance depends on the specific goal of your research.

FAQ: How can I improve the generalizability of my predictive model?

Strategies beyond traditional random cross-validation can improve a model's ability to extrapolate. One approach is to use a forward cross-validation strategy, which sequentially expands the training set to mimic the process of exploring unknown data space. In materials science, this strategy has been shown to significantly improve the prediction accuracy for high-performance materials lying outside the range of known data [27]. Ensuring your training data encompasses sufficient biological and technical diversity is also critical.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Prediction Accuracy on Benchmark Data

Problem: Your network inference or predictive model is performing poorly on a gold-standard benchmark dataset.

Solution Steps:

- Verify Data Preprocessing: Ensure all input data, such as gene names or identifiers, are consistent and normalized. Inconsistent nomenclature is a common source of error. Use robust identifier mapping tools like UniProt ID mapping, BioMart, or the MyGene.info API to unify identifiers before network construction [2].

- Benchmark Against Baselines: Compare your model's performance against the baseline methods reported in the benchmark challenge. For example, CausalBench provides a list of implemented state-of-the-art methods for comparison [26]. This will help you understand if your approach is fundamentally lacking or requires tuning.

- Consider an Ensemble Approach: If no single method provides optimal performance, leverage the "wisdom of crowds." The DREAM5 challenge concluded that integrating predictions from multiple inference methods generates robust, high-performance consensus networks that are more accurate than any individual method [28].

- Evaluate Task Difficulty: Understand that some tasks are inherently more challenging. For example, in the DNALONGBENCH suite, contact map prediction proved significantly more difficult for models than other tasks [29]. Adjust your expectations and performance targets accordingly.

Issue: Handling Incomplete or Noisy Biological Networks

Problem: Real-world biological network data is often incomplete and contains false positives, which skews analysis and model predictions.

Solution Steps:

- Acknowledge the Limitation: Be aware that experimental techniques can miss interactions (false negatives) and high-throughput methods can produce false positives. This can affect network properties and lead to incorrect conclusions [30].

- Use Confidence Scores: When available, incorporate interaction confidence scores into your analysis. Databases like STRING provide confidence scores for each protein-protein interaction, allowing you to filter out low-confidence edges [30].

- Leverage Data Integration: Integrate multiple sources of evidence to build a more reliable network. For instance, the STRING database integrates protein-protein interactions from experimental, computational, and other data sources to improve coverage and reliability [30].

Issue: Scaling Network Inference Methods to Large Datasets

Problem: Your network inference method is computationally too slow or consumes too much memory for large-scale data.

Solution Steps:

- Optimize Data Representation: Choose an efficient network representation format. For large, sparse networks, use an adjacency list or edge list instead of a memory-intensive adjacency matrix. For very large, sparse networks, a compressed sparse row (CSR) format can significantly reduce memory consumption [2].

- Check Method Scalability: Select methods designed for scalability. An initial evaluation with CausalBench highlighted that poor scalability of existing methods was a major factor limiting their performance on large-scale single-cell perturbation data [26].

- Implement Dimensional Analysis: In computer experiments, applying dimensional analysis to create dimensionless quantities from original variables can be a strategy to improve the prediction accuracy of surrogate models like Gaussian Stochastic Processes, potentially leading to more efficient modeling [31].

The table below summarizes key features of several contemporary benchmark resources for biological network research.

| Benchmark Name | Focus Area | Key Feature | Noteworthy Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| CausalBench [26] | Causal Network Inference | Uses real-world large-scale single-cell perturbation data. | Poor scalability limits method performance; interventional data use does not guarantee superiority. |

| DNALONGBENCH [29] | Long-range DNA Prediction | Comprehensive suite covering five tasks with dependencies up to 1 million base pairs. | Expert models (e.g., Enformer, Akita) consistently outperform general DNA foundation models. |

| DREAM Challenges [25] [28] | Broad Biomedical Prediction (e.g., EHR, Gene Networks) | Community-driven blind assessment of methods. | No single method is best; consensus from multiple methods is most robust. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking a Network Inference Method

This protocol outlines the key steps for evaluating a network inference method using a benchmark suite like CausalBench.

1. Data Acquisition and Preparation:

- Download the benchmark dataset (e.g., from the CausalBench GitHub repository) which includes curated single-cell RNA-seq data from perturbed and control cells [26].

- Perform necessary preprocessing as specified by the benchmark, which may include normalization and log-transformation of gene expression counts.

2. Model Training and Prediction:

- Configure your network inference model according to its parameters.

- Train the model on the designated training set or the full dataset as per the benchmark's rules. For methods that use both observational and interventional data, ensure the data is integrated correctly.

- Run the trained model to generate a ranked list of predicted gene-gene interactions (e.g., an edge list).

3. Performance Evaluation:

- Use the evaluation metrics and scripts provided by the benchmark to assess your model's output.

- Key Metrics:

- Biology-driven Evaluation: Compares predictions to a curated, high-confidence set of known biological interactions, reporting precision, recall, and F1 score [26].

- Statistical Evaluation (CausalBench):

- Mean Wasserstein Distance: Measures to what extent predicted interactions correspond to strong causal effects.

- False Omission Rate (FOR): Measures the rate at which true causal interactions are omitted by the model [26].

- Compare your results against the provided baseline methods to contextualize your model's performance.

Benchmark Evaluation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the typical workflow for evaluating a method within a benchmark challenge like CausalBench.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CausalBench GitHub Repo [26] | Software/Data | Provides the complete benchmarking suite, datasets, and baseline implementations for evaluating causal network inference methods. |

| GP-DREAM (GenePattern) [28] | Web Platform | Allows researchers to apply top-performing network inference methods from DREAM challenges and construct consensus networks without local installation. |

| STRING Database [30] | Biological Database | Provides a comprehensive resource of known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) for building and validating networks. |

| UniProt ID Mapping / BioMart [2] | Bioinformatics Tool | Critical for normalizing gene and protein identifiers across datasets to ensure node nomenclature consistency during network integration. |

| HyenaDNA / Caduceus [29] | DNA Foundation Model | Pre-trained models that can be fine-tuned for long-range DNA prediction tasks as evaluated in benchmarks like DNALONGBENCH. |

| Adjacency List / Edge List [2] | Data Format | Efficient computational formats for representing large, sparse biological networks, enabling the analysis of massive datasets. |

Cutting-Edge Methods: AI and Machine Learning for Network Inference and Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Correlation Networks

Q: What are the main methods for constructing a biological network from a correlation matrix, and how do I choose? A: Converting correlation matrices into networks is a central step, and several methods exist, each with advantages and drawbacks [32]. The table below summarizes the primary approaches.

| Method | Description | Best Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thresholding | A correlation value threshold is set; connections stronger than the threshold form network edges. | Quick, exploratory analysis on highly correlated data. | Prone to producing misleading networks; sensitive to arbitrary threshold choice [32]. |

| Weighted Networks | The correlation matrix itself is treated as a weighted adjacency matrix, preserving all interaction strengths. | Analyzing the full structure of interactions without losing information. | The resulting network can be dense and computationally heavy for large datasets [32]. |

| Regularization | Statistical techniques (e.g., Bayesian methods) are used to induce sparsity and stability in the network. | High-dimensional data (e.g., genes, metabolites) where the number of variables exceeds samples [33] [32]. | Helps separate direct from indirect correlations, improving biological interpretability. |

| Threshold-Free | Methods that avoid hard thresholds, instead using null models to assess the statistical significance of each correlation. | Robust hypothesis testing to identify connections that are stronger than expected by chance [32]. | Requires careful construction of an appropriate null model for the specific biological data. |

Q: My correlation network is too dense and uninterpretable. How can I resolve this? A: A dense network often indicates a high number of indirect correlations. To address this:

- Use Partial Correlation: Move from simple correlation to partial correlation. This measures the association between two variables after removing the effect of other variables, helping to distinguish direct from indirect interactions [33].

- Apply Regularization: Implement regularization methods like Bayesian Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs). These techniques introduce constraints that force less robust edges to zero, resulting in a sparser, more interpretable network of direct relationships [33] [34].

- Employ Null Models: Use threshold-free approaches with null models to filter out correlations that are not statistically significant, reducing clutter from random noise [32].

Regression Analysis

Q: How can I prevent my regression model from overfitting when predicting node properties? A: Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise in the training data instead of the underlying relationship. To improve generalization:

- Use Regularized Regression: Algorithms like LASSO or Ridge Regression penalize model complexity by adding a constraint on the size of the coefficients, preventing them from becoming too large and fitting the noise [35].

- Apply Cross-Validation: Always use cross-validation (e.g., k-fold) to tune hyperparameters and evaluate model performance. This ensures your performance metric is based on unseen data, giving a true estimate of predictive accuracy [35].

- Ensure Adequate Data: Machine learning models, including regression, require sufficient data to learn generalizable patterns. The model's complexity should be appropriate for the size of your dataset [35].

Q: What are the key regression algorithms used in biological network research? A: Several core algorithms are widely adopted for their balance of predictive accuracy and interpretability [35].

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Common Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) | Finds the line (or hyperplane) that minimizes the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values. | Simple, fast, and highly interpretable; coefficients are easily explained. | Baseline modeling, understanding linear relationships between node attributes and outcomes [35]. |

| Random Forest | An ensemble method that builds many decision trees and averages their predictions. | Reduces overfitting, handles non-linear relationships well, provides feature importance scores. | Predicting gene function, classifying disease states based on network features, host taxonomy prediction [35]. |

| Gradient Boosting | An ensemble method that builds trees sequentially, with each new tree correcting errors made by the previous ones. | Often achieves higher predictive accuracy than Random Forest. | Pathogenicity prediction of genetic variants, complex phenotype prediction from omics data [36] [35]. |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Finds the optimal hyperplane that best separates data points of different classes in a high-dimensional space. | Effective in high-dimensional spaces and with complex, non-linear relationships (using kernels). | Protein classification, disease subtype classification from network data [35]. |

Bayesian Networks

Q: What are the main challenges when implementing Bayesian Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs), and how are they addressed? A: Bayesian GGMs are powerful for estimating partial correlation networks but face specific challenges [33] [34].

| Challenge | Description | Modern Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperparameter Tuning | The choice of prior distribution parameters significantly impacts results and is often difficult to set. | Novel methods like HMFGraph use a condition number constraint on the precision matrix to guide hyperparameter selection, making it more automated and stable [33] [34]. |

| Edge Selection | Determining which edges are statistically non-zero to create the final network adjacency matrix. | Using approximated credible intervals (CI) whose width is controlled by the False Discovery Rate (FDR). The optimal CI is selected by maximizing an estimated F1-score via permutations [33] [34]. |

| Computational Scalability | Traditional Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are computationally demanding for large biological datasets. | New approaches use fast Generalized Expectation-Maximization (GEM) algorithms, which offer significant computational advantages over MCMC [33] [34]. |

| Prior Choice | The inflexibility of standard priors (e.g., Wishart) can limit model performance. | Development of more flexible priors, such as the hierarchical matrix-F prior, which offers competitive network recovery capabilities [33] [34]. |

Q: How is the False Discovery Rate (FDR) controlled in Bayesian network estimation? A: In Bayesian GGMs, FDR control is integrated into the edge selection process. The method involves calculating credible intervals for the partial correlation coefficients in the precision matrix. The width of these intervals is systematically adjusted to control the FDR at a desired level (e.g., 0.2) [33]. This means you can set an a priori expectation that, for instance, 20% of the edges in your final network may be incorrect. This controlled tolerance for false positives can help in recovering meaningful cluster structures that might be lost in an overly sparse network [33] [34].

General Experimental Design

Q: How can I improve the interpretability of my machine learning model for a biological audience? A: Beyond raw accuracy, interpretability is crucial for biological insight [35].

- Use Interpretable Models: Start with models like OLS or Random Forest, which provide clear feature importance scores, before moving to "black box" models [35].

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Integrate existing biological knowledge (e.g., known pathways) as constraints or priors in your model to ground the results in established science.

- Apply Model-Agnostic Tools: Use tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to explain the output of any model, highlighting which features were most important for a given prediction [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Network Recovery in High-Dimensional Data

Scenario: You are working with gene expression data where the number of genes (p) is much larger than the number of samples (n). Your inferred network is unstable or fails to identify known biological pathways.

| Step | Action | Technical Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Switch to a Regularized GGM | Move from a simple correlation network to a Bayesian GGM with a sparsity-inducing prior, such as the hierarchical matrix-F prior. This separates direct from indirect interactions. | A more stable, sparse network that is less prone to overfitting. |

| 2 | Tune the Hyperparameter | Use a method that constrains the condition number of the estimated precision matrix (Ω) to guide hyperparameter selection, ensuring a well-conditioned and numerically stable estimate [33]. | A robust model that is not overly sensitive to small changes in the input data. |

| 3 | Perform Edge Selection with FDR Control | Use approximated credible intervals to select edges, setting a target FDR (e.g., 5-20%). This provides a statistically principled network [33] [34]. | A final network with a known and controlled rate of potential false positive edges. |

| 4 | Validate with Known Pathways | Check if the recovered network enriches for genes in known biological pathways (e.g., using Gene Ontology enrichment analysis). | Confirmation that the network captures biologically meaningful modules. |

Problem: Low Predictive Accuracy for Node-Level Regression

Scenario: You are trying to predict a node property (e.g., essential gene status) using features from a network, but your model's accuracy is low on unseen test data.

| Step | Action | Technical Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check for Data Leakage | Ensure that no information from the test set was used during training (e.g., in feature scaling or imputation). Perform all preprocessing steps within each cross-validation fold. | An honest assessment of model generalizability. |

| 2 | Feature Engineering | Create more informative features from the network, such as centrality measures (degree, betweenness), clustering coefficient, or community membership. | The model has more predictive signals to learn from. |

| 3 | Apply Regularized Regression | Use Random Forest or Gradient Boosting, which are inherently resistant to overfitting, or use LASSO/Ridge regression to penalize complex models. | A model that balances bias and variance, leading to better test performance. |

| 4 | Hyperparameter Tuning | Use cross-validated grid or random search to optimize key parameters (e.g., learning rate for boosting, tree depth for Random Forest). | Maximized model performance based on the validation data. |

| 5 | Test Different Algorithms | Systematically compare multiple algorithms (see FAQ table) to find the best performer for your specific dataset. | Selection of the most accurate model for deployment. |

Problem: Ineffective Biological Network Visualization

Scenario: The network figure you've created for your publication is cluttered, difficult to interpret, and the message is not clear to readers.

| Step | Action | Technical Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Determine Figure Purpose | Write a precise caption first. Decide if the message is about network functionality (e.g., signaling flow) or structure (e.g., clusters) [1]. | A clear goal that guides all subsequent design choices. |

| 2 | Choose an Appropriate Layout | For structure/clusters, use force-directed layouts. For functionality/flow, use hierarchical or circular layouts. For very dense networks, consider an adjacency matrix [1]. | A spatial arrangement that reinforces the intended message. |

| 3 | Use Color and Labels Effectively | Use a highly contrasting color palette (tested for color blindness). Ensure labels are legible at publication size. Use color saturation or node size to encode quantitative data [1] [37] [38]. | Key elements and patterns are immediately visible and understandable. |

| 4 | Apply Layering and Separation | Highlight a subnetwork or pathway of interest by making it fully colored, while graying out other context nodes. Use neutral colors (e.g., gray) for links to avoid interfering with node discriminability [1] [37]. | The reader's attention is directed to the most important part of the story. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HMFGraph R Package | Implements a novel Bayesian GGM with a hierarchical matrix-F prior for network recovery from high-dimensional data [33] [34]. | Inferring gene co-expression networks from RNA-Seq data where the number of genes far exceeds the number of patient samples. |

| Cytoscape | An open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating them with any type of attribute data [1]. | Visualizing a protein-protein interaction network, coloring nodes by fold-change expression, and sizing them by mutation count. |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | A comprehensive library featuring implementations of regression algorithms (Random Forest, SVM, etc.), model evaluation, and hyperparameter tuning tools [35]. | Building a classifier to predict pathogenicity of genetic variants based on integrated multimodal annotations. |

| Viz Palette Tool | An online tool to test color palettes for accessibility, simulating how they appear to users with different types of color vision deficiency (CVD) [38]. | Ensuring the color scheme chosen for a network figure (e.g., to show up/down-regulated genes) is interpretable by all readers. |

| Adjacency Matrix Layout | An alternative to node-link diagrams where rows and columns represent nodes and cells represent edges; excellent for dense networks and showing clusters [1]. | Visualizing a dense microbiome co-occurrence network where node-link diagrams would be too cluttered to interpret. |

Fundamental Concepts & FAQs

What are Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and why are they important for biological research?

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are a powerful class of deep learning models specifically designed to handle graph-structured data. Unlike traditional Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) that operate on grid-like data structures such as images, GCNs are tailored to work with non-Euclidean data, making them suitable for a wide range of biological applications including molecular interaction networks, protein-protein interactions, and gene regulatory networks [39].

A graph consists of nodes (vertices) and edges (connections between nodes). In a GCN, each node represents an entity, and edges represent relationships between these entities. The primary goal of GCNs is to learn node embeddings—vector representations of nodes that capture the graph's structural and feature information [39]. For biological research, this means you can represent proteins as nodes and their interactions as edges, then use GCNs to predict novel interactions or classify protein functions based on network structure and node features.

What's the difference between spectral-based and spatial-based GCNs?

GCNs can be broadly categorized into two main types [39]:

Spectral-based GCNs: Defined in the spectral domain using the graph Laplacian and Fourier transform. The convolution operation is performed by multiplying the graph signal with a filter in the spectral domain. This approach leverages the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the graph Laplacian. Key models include ChebNet (uses Chebyshev polynomials) and GCN by Kipf & Welling (uses first-order approximation).

Spatial-based GCNs: Perform convolution directly in the spatial domain by aggregating features from neighboring nodes. This approach is more intuitive and easier to implement. Key models include GraphSAGE (aggregates features using mean, LSTM, or pooling) and GAT (Graph Attention Network) which assigns different weights to neighbors based on importance.

For biological networks, spatial-based GCNs often prove more practical as they can naturally handle varying network topologies and incorporate domain-specific aggregation functions.

How do Graph Autoencoders (GAEs) differ from standard GCNs?

Graph Autoencoders (GAEs) are unsupervised neural architectures that encode both combinatorial and feature information of graphs into a continuous latent space for reconstruction tasks [40]. While standard GCNs are typically used for supervised tasks like node classification, GAEs learn by reconstructing aspects of the original graph such as node attributes or connectivity patterns.

The canonical GAE framework combines a graph neural network (GNN) encoder with a differentiable decoder. Variants include:

- Variational GAEs (VGAEs): Incorporate probabilistic latent spaces with an evidence lower bound (ELBO) objective

- Masked GAEs: Use masking techniques where subsets of graph components are randomly masked and reconstructed

- Modern GAEs: Employ cross-correlation decoders that handle directed graphs and asymmetric structures better than traditional inner-product decoders [40]

GAEs are particularly valuable for biological network completion, identifying missing interactions, and learning low-dimensional representations of complex biological systems.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

How can I prevent over-smoothing in deep GCN architectures?

Over-smoothing occurs when stacking too many graph convolution layers causes node features to become indistinguishable, significantly limiting model depth and performance [41]. This is particularly problematic in biological networks where capturing hierarchical organization is crucial.

Solutions:

- Non-local Message Passing (NLMP): Implement frameworks that incorporate non-local interactions beyond immediate neighbors [41]

- Residual Connections: Adapt ResNet-style skip connections to maintain gradient flow and feature diversity in deep layers [41]

- Attention Mechanisms: Use Graph Attention Networks (GAT) to dynamically weight neighbor importance rather than uniform aggregation [39]

- Jumping Knowledge Networks: Employ selective combination of representations from different layers to preserve multi-scale information

Why do my GCN models perform poorly with limited labeled biological data?

Biological network data often suffers from limited labeled examples due to experimental costs and validation time [42]. GCNs typically require substantial labeled data for supervised training, but several strategies can address this limitation:

Solutions:

- Self-supervised Learning: Use Graph Autoencoders for pre-training on unlabeled network data before fine-tuning on labeled subsets [40]

- Transfer Learning: Pre-train on larger biological networks (e.g., protein-protein interaction databases) then transfer to specific organisms or conditions

- Data Efficiency Techniques: Controlled sequence diversity in training data can substantially improve data efficiency [42]

- Semi-supervised Approaches: Leverage label propagation combined with GCNs to utilize both labeled and unlabeled nodes

Table: Comparison of Data Efficiency Techniques for Biological Sequence Models [42]

| Method | Data Requirement | Prediction Accuracy (R²) | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ridge Regression | Medium (2,000+ sequences) | 0.65-0.75 | Linear genotype-phenotype relationships |

| Random Forests | Medium (2,000+ sequences) | 0.70-0.80 | Non-linear but shallow relationships |

| Convolutional Neural Networks | High (5,000+ sequences) | 0.80-0.90 | Complex spatial dependencies in sequences |

| Optimized CNN with Diversity Control | Low (500-1,000 sequences) | 0.75-0.85 | Limited budget experimental designs |

How can I ensure my biological interpretations are reliable and not biased by network structure?

Interpretation reliability is crucial in biological applications where conclusions might guide experimental follow-up [43]. Common issues include interpretation variability across training runs and biases introduced by network topology.

Solutions:

- Repeated Training Replicates: Train multiple models with different random seeds to assess interpretation robustness [43]

- Control Experiments: Use deterministic control inputs and label shuffling to identify network structure biases [43]

- Differential Importance Scoring: Compare importance scores from real data versus controls to identify genuinely important nodes

- Bias-Aware Regularization: Implement regularization techniques that explicitly account for network topology biases

Table: Interpretation Robustness Assessment Framework [43]

| Assessment Method | Procedure | Interpretation Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Repeated Training | Train 10-50 models with different random seeds | Nodes with consistent high importance across replicates are reliable |

| Deterministic Control Inputs | Create artificial inputs where all features are equally predictive | Identifies nodes favored by network topology regardless of data |

| Label Shuffling | Train models on randomly shuffled labels | Reveals interpretations that emerge from spurious correlations |

| Differential Scoring | Compare real vs. control importance scores | Highlights biologically meaningful signals beyond structural biases |

What decoder architecture should I choose for Graph Autoencoders in link prediction?

Decoder selection significantly impacts GAE performance, especially for biological networks with complex relationship types [40].

Solutions:

- Inner-product decoders: Efficient but limited to symmetric relationships—use only for undirected biological networks

- Cross-correlation decoders: Essential for directed relationships (e.g., regulatory networks) and asymmetric structures [40]

- L2/RBF decoders: Suitable for metric reconstructions where distance reflects relationship strength

- Task-specific decoders: Custom decoders incorporating biological domain knowledge (e.g., metabolic flux constraints)

Table: GAE Decoder Types and Their Applications in Biological Networks [40]

| Decoder Type | Mathematical Formulation | Biological Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inner-product | σ(zᵢᵀzⱼ) | Protein-protein interaction networks (undirected) | Cannot model directed edges or asymmetric relationships |

| Cross-correlation | σ(pᵢᵀqⱼ) | Gene regulatory networks (directed), metabolic pathways | Requires separate node and context embeddings |

| L2/RBF | σ(C(1-∥zᵢ-zⱼ∥²)) | Spatial organization networks, cellular localization | Assumes metric relationship space |

| Softmax on Distances | Softmax(-∥zᵢ-zⱼ∥²) | Cluster-based network analysis, functional modules | Computationally intensive for large networks |

Advanced Techniques for Biological Network Analysis

How can I model multiple relationship types in biological networks?

Many biological networks contain multiple relationship types (e.g., different interaction types in protein networks). Standard GCNs struggle with this complexity, but several extensions address this challenge [44]:

Solutions:

- Relational GCNs (R-GCNs): Use separate weight matrices for different relation types during neighborhood aggregation

- Multi-task GAEs: Employ separate decoders for different relationship types while sharing encoder parameters

- Edge-type Attention: Extend GAT to consider both node and edge features during aggregation

- Tensor Factorization: Combine GCNs with tensor decomposition methods for multi-relational data

What regularization techniques are most effective for GAEs in biological applications?

Regularization is crucial for robust GAE performance, particularly with noisy biological data [40]:

Effective Techniques:

- Variational Regularization: KL divergence penalty in VGAEs prevents overfitting to training graph structure

- Laplacian/Manifold Regularization: Enforces smoothness over the graph structure—adjacent nodes have similar embeddings

- Feature and Edge Masking: Creates robust pretext tasks that prevent degenerate solutions [40]

- Adaptive Graph Learning: Jointly learns graph structure and node embeddings for noisy or incomplete biological networks

- L2-normalization: Particularly in VGNAE variants, prevents embedding collapse for isolated nodes [40]

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

Standardized Protocol for Biological Network Link Prediction

Objective: Predict missing interactions in biological networks using Graph Autoencoders

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Format network as adjacency matrix A and node feature matrix X

- Randomly remove 15% of edges as test set, use remaining 85% for training

- For biological sequences, use k-mer encoding or biophysical property encoding [42]

Encoder Selection:

- For small networks (<1,000 nodes): 2-layer GCN with 32-64 hidden units

- For large networks: GraphSAGE with mean pooling or GAT with 4 attention heads

Decoder Selection:

- For symmetric networks: Inner-product decoder

- For directed networks: Cross-correlation decoder [40]

- For weighted networks: L2/RBF decoder

Training Configuration:

- Optimizer: Adam with learning rate 0.01

- Early stopping: Patience of 100 epochs based on validation reconstruction loss

- Regularization: Dropout (rate 0.5) and weight decay (5e-4)

Evaluation Metrics:

- Area Under Curve (AUC) and Average Precision (AP) for link prediction

- For node classification: Accuracy, F1-score

- Report mean ± standard deviation across 10 training runs [43]

Table: Benchmark Performance of GAE Variants on Biological Networks [40] [45]

| Model | Cora (AUC) | Citeseer (AUC) | Protein Network (AP) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAE | 0.866 | 0.906 | 0.852 | Simple, efficient for homogeneous networks |

| VGAE | 0.872 | 0.909 | 0.861 | Probabilistic embeddings, better uncertainty |

| VGNAE | 0.890 | 0.941 | 0.883 | No collapse for isolated nodes, more robust |

| GraphMAE | N/A | N/A | 0.896 | Superior feature reconstruction |

| MaskedGAE | 0.901 | 0.932 | 0.904 | Handles noisy biological data effectively |

Protocol for Interpretable Biology-Inspired GCNs

Objective: Identify key biological entities (genes, pathways) important for prediction tasks

Methodology [43]:

- Network Architecture:

- Design biology-inspired architecture where hidden nodes correspond to biological entities

- Create sparse connections based on known biological relationships

- Implement using P-NET or KPNN frameworks

Robust Interpretation Pipeline:

- Train multiple replicates (10-50) with different random seeds

- Calculate node importance scores using DeepLIFT or similar methods

- Train on deterministic control inputs to identify network topology biases

- Compute differential scores (real data importance minus control importance)

Validation:

- Compare top-ranked entities with known biological literature

- Perform enrichment analysis for functional validation

- Experimental validation when possible

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Computational Tools for GCN/GAE Research in Biological Networks

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Geometric | Library | Graph neural network implementation | Rapid prototyping of GCN architectures |

| DGL (Deep Graph Library) | Library | Scalable graph neural networks | Large biological network analysis |

| Graph Autoencoder Frameworks | Software | GAE/VGAE implementation | Link prediction in biological networks |

| BioPython | Library | Biological data processing | Sequence to feature transformation |

| STRING Database | Data Resource | Protein-protein interactions | Biological network construction |

| Reactome | Data Resource | Pathway information | Biology-inspired architecture design |

| Cora/Citeseer | Benchmark Data | Citation networks | Method validation and benchmarking |

| Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) | Algorithm | Dimensionality reduction | Visualization of node embeddings |

Emerging Frontiers & Future Directions

Masked Graph Autoencoding

Masked autoencoding has recently renewed interest in graph self-supervised learning [45]. By randomly masking portions of the graph (nodes, edges, or features) and learning to reconstruct them, models can learn richer representations without labeled data. For biological networks, this approach is particularly valuable when labeled examples are scarce but unlabeled network data is abundant.

Integration with Contrastive Learning