Advanced Optimization Methods for Parameter Estimation in Systems Biology: From Foundations to AI-Driven Approaches

Parameter estimation is a central challenge in building predictive computational models of biological systems.

Advanced Optimization Methods for Parameter Estimation in Systems Biology: From Foundations to AI-Driven Approaches

Abstract

Parameter estimation is a central challenge in building predictive computational models of biological systems. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles, core methodological classes, and cutting-edge strategies for robust parameter estimation. We explore the landscape of optimization techniques, from global metaheuristics and gradient-based methods to the latest hybrid mechanistic-AI approaches and parallel computing frameworks. A strong emphasis is placed on practical troubleshooting—addressing pervasive issues like non-identifiability and overfitting—and on rigorous validation and uncertainty quantification to ensure models are both accurate and reliable for biomedical insight.

The Parameter Estimation Challenge: Core Concepts and Obstacles in Systems Biology

In systems biology research, the inverse problem refers to the process of determining the unknown parameters of a mathematical model from empirical observational data [1]. This stands in contrast to the forward problem, which involves using a fully parameterized model to simulate predictions of a system's behavior. Solving inverse problems is a fundamental prerequisite for creating predictive, mechanistic models that can offer genuine insight, test hypotheses, and forecast system states under normal or perturbed conditions [1]. The activity of parameterizing a model constitutes the inverse problem, which can range from manageable to nearly impossible depending on the biological system and model complexity [1]. This Application Note frames the inverse problem within the context of optimization methods for parameter estimation, providing researchers with structured protocols and practical tools for addressing this critical challenge in biological research and drug development.

Mathematical Formulation of the Inverse Problem

Biological systems are often represented mathematically using systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) or rule-based interactions. A general formulation is presented below [1]:

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| System Dynamics | $\dot{\underline{X}} = f(\underline{X}, \underline{p}, t) + \underline{U}(\underline{X}, t) + \underline{N}(t)$ | Describes the temporal evolution of biological species concentrations ($\underline{X}$). |

| Observables | $\underline{O} = g(\underline{X})$ | Represents the quantities that can be experimentally measured. |

| State Variables | $\underline{X}$ | A vector of variables representing concentrations of model components (e.g., proteins, metabolites). |

| Parameters | $\underline{p}$ | A vector of unknown model parameters (e.g., rate constants, binding affinities) to be estimated. |

| External Inputs | $\underline{U}(\underline{X}, t)$ | Represents known external perturbations or experimental treatments applied to the system. |

| Intrinsic Noise | $\underline{N}(t)$ | Accounts for stochastic fluctuations or unmodeled dynamics within the biological system. |

The core of the inverse problem is to find the parameter vector $\underline{p}$ that minimizes the difference between model predictions and experimental data, typically quantified by an objective function. A common objective function is the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) [2].

A Framework for Solving Inverse Problems

Key Challenges and Definitions

Successfully solving an inverse problem requires navigating several theoretical and practical challenges, which are summarized in the table below.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Impact on Model |

|---|---|---|

| Model Identifiability | Whether parameters can be uniquely identified from the available data, even assuming perfect, noise-free data [1]. | Unidentifiable models have multiple parameter sets that fit the data equally well, preventing unique biological interpretation. |

| Parameter Uncertainty | The degree of confidence in the estimated parameter values, given noisy and limited experimental data [1]. | High uncertainty reduces the predictive power and reliability of the model for making quantitative forecasts. |

| Practical Identifiability | The ability to identify parameters with acceptable precision from real, noisy, and limited datasets [1]. | Even a structurally identifiable model may yield poor parameter estimates if the data is insufficient. |

| Ill-posedness | The solution may not depend continuously on the data, meaning small errors in data can lead to large errors in parameter estimates [1]. | The model is highly sensitive to experimental noise, making reproducibility and validation difficult. |

Optimization Methods for Parameter Estimation

A variety of optimization methods can be applied to solve the inverse problem by minimizing the chosen objective function. These can be broadly categorized, and recent research explores hybrid approaches.

Hybrid optimization methods combine the strengths of global metaheuristics and local gradient-based optimizers. A case study in preparative liquid chromatography demonstrated that such a hybrid method achieved superior computational efficiency compared to traditional multi-start methods, which rely solely on local optimization from many random starting points [3]. This highlights the potential of hybrid strategies to advance parameter estimation in large-scale, dynamic chemical engineering and biological applications.

Experimental Protocol: Parameter Estimation Workflow

The following protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for estimating model parameters from experimental data, incorporating principles of experimental design [4] and the inverse problem framework [1].

Protocol: Parameter Estimation via Hybrid Optimization

Purpose: To provide a standardized workflow for estimating unknown parameters of a dynamic biological model from experimental data, using a hybrid optimization strategy for robust and efficient results.

I. Pre-experimental Planning and Variable Definition

Define Research Question & Variables:

- Formulate a specific research question (e.g., "How does the kinase concentration affect the phosphorylation rate in this signaling pathway?").

- List and define all variables using the following table as a guide [4]:

Variable Type Definition Example from Signaling Independent The variable you manipulate. Concentration of a ligand or inhibitor. Dependent The variable you measure as the outcome. Level of phosphorylated protein (e.g., pERK). Confounding An extraneous variable that may affect the dependent variable and create spurious results. Cell passage number, slight variations in serum batch. Formulate Hypotheses:

- Write a specific, testable null hypothesis (H₀), e.g., "The rate constant k₁ for the phosphorylation reaction is zero."

- Write a specific, testable alternative hypothesis (H₁), e.g., "The rate constant k₁ for the phosphorylation reaction is greater than zero."

Design Experimental Treatments:

- Decide on the levels (e.g., low, medium, high) and number of your independent variable.

- Ensure the range and resolution of these levels are sufficient to inform the model parameters.

Assign Subjects to Groups:

- Use a randomized block design where subjects (e.g., cell culture plates) are first grouped by a shared characteristic (e.g., incubation day) and then randomly assigned to treatments within these groups to control for batch effects [4].

- Always include a control group that receives no treatment (e.g., vehicle control).

II. Data Collection and Model Preparation

Measure Dependent Variable:

- Collect high-quality, quantitative data for your dependent variable(s) over a relevant time course and under all experimental conditions.

- Use calibrated instruments and replicate measurements (biological and technical replicates) to estimate experimental error.

Formulate the Mathematical Model:

- Develop a system of equations (e.g., ODEs) representing the biological system's dynamics.

- Clearly identify which parameters in the model are known and which are unknown and need to be estimated.

Define the Objective Function:

- Formulate a function that quantifies the discrepancy between model simulations and experimental data. The most common is the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) [2]:

SSE = Σ (y_data - y_model)²where the sum is over all data points, observables, and experimental conditions.

- Formulate a function that quantifies the discrepancy between model simulations and experimental data. The most common is the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) [2]:

III. Optimization and Model Assessment

Select and Run Optimization:

- Initialization: Choose plausible lower and upper bounds for all parameters to be estimated.

- Global Phase: Run a metaheuristic algorithm (e.g., Gray Wolf Optimization [2]) to thoroughly explore the parameter space and locate the region of the global minimum. Run for a predetermined number of iterations or until convergence is observed.

- Local Phase: Use the solution from the global optimizer as the initial guess for a gradient-based local optimizer (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt). This refines the parameter estimates to a high precision [3].

Assess Model Fit and Identifiability:

- Examine the plot of model simulation versus experimental data for a qualitative assessment of goodness-of-fit.

- Calculate the final value of the objective function (e.g., SSE) and the coefficient of determination (R²).

- Perform profile likelihood analysis or bootstrapping to evaluate parameter practical identifiability and uncertainty [1].

Validate the Model:

- Use the estimated parameters to predict the outcome of a new experiment that was not used for parameter estimation. Compare predictions against new data to test the model's external validity and predictive power [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and computational tools used in parameter estimation for systems biology.

| Item / Reagent | Function in Parameter Estimation |

|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Enable quantitative measurement of protein post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation), which are critical dynamic data for inferring kinase/phosphatase activities. |

| LC-MS/MS Instrumentation | Provides highly multiplexed, absolute quantitative data on protein and metabolite abundances, essential for populating state variables (X) in large-scale models. |

| SIERRA (Stochastic Simulation Algorithm) | A computational algorithm used for simulating biochemical systems with low copy numbers, helping to parameterize models where deterministic ODEs are insufficient. |

| DAISY Software | A specialized software tool used to test the global identifiability of biological and physiological systems a priori [1]. |

| Axe DevTools Color Contrast Analyzer | A tool to ensure that all text in generated diagrams and visualizations has sufficient color contrast for accessibility and clarity, as per WCAG guidelines [5]. |

| Young’s Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE) Algorithm | A novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm inspired by wave physics, demonstrated to achieve low Sum of Square Error (SSE) in complex parameter estimation tasks like modeling fuel cells [2]. |

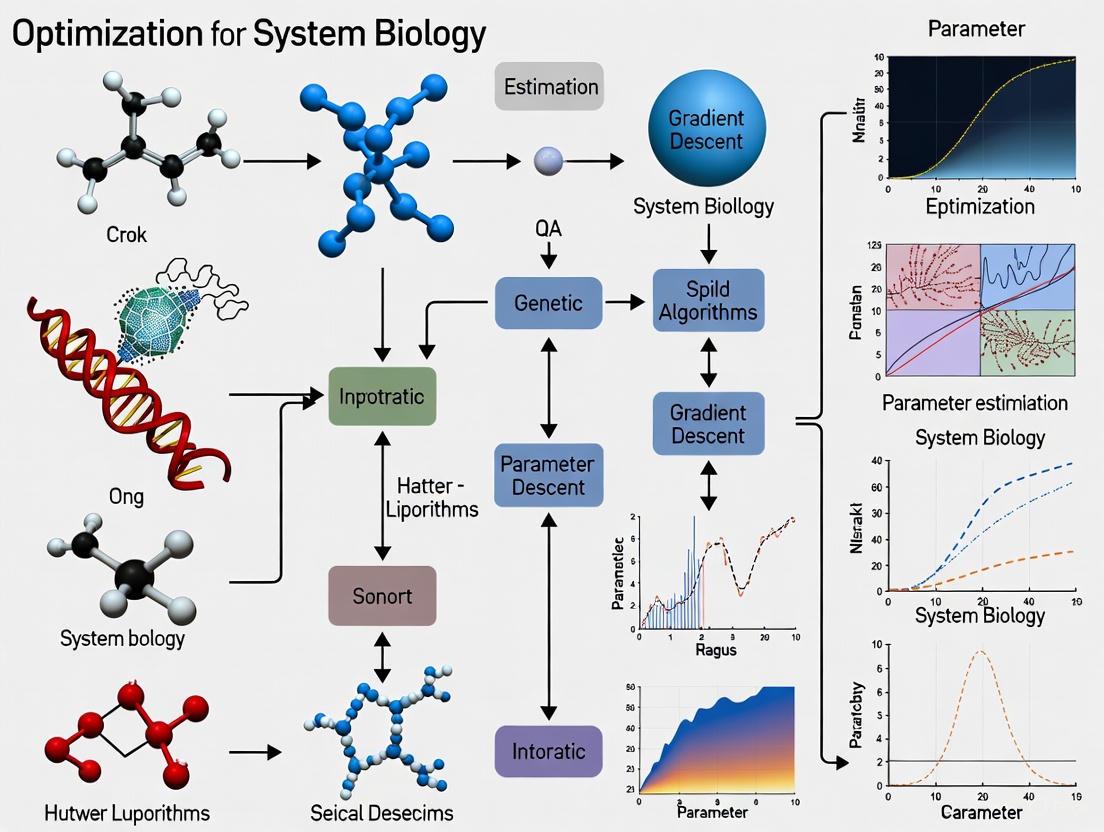

Visualizing the Complete Workflow

The following diagram synthesizes the entire process, from experimental design to a validated model, highlighting the iterative nature of solving the inverse problem.

Parameter estimation turns a conceptual mathematical model into a quantitative, predictive tool in systems biology. This inverse problem, of calibrating model parameters to align with experimental data, is the cornerstone for simulating biological networks, predicting cellular responses, and informing drug development strategies. However, this process is notoriously fraught with pathological challenges that can compromise the reliability and predictive power of the resulting model. Three such fundamental pathologies are nonconvexity, ill-conditioning, and sloppiness. Nonconvexity refers to optimization landscapes that are riddled with numerous local minima, making the search for the best parameters akin to finding the lowest valley in a complex, rugged mountain range. Ill-conditioning arises when the estimation problem is overly sensitive to minute changes in data or parameters, often leading to numerical instability and physical implausibility. Sloppiness describes a universal characteristic of systems biology models where their predictions are exquisitely sensitive to a handful of parameter combinations while being largely insensitive to many others, creating a vast space of equally good but mechanistically different parameter sets. This Application Note details robust computational protocols to diagnose, analyze, and overcome these challenges, ensuring the development of biologically realistic and predictive models.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Characterization

Defining the Pathological Trio

- Nonconvexity: In the context of parameter estimation for nonlinear dynamic models, the objective function (e.g., a sum of squares measuring the difference between model output and data) is often nonconvex. This means the function has multiple local minima, and optimization algorithms can easily become trapped in a suboptimal solution that does not represent the best possible fit. Relying on local optimization methods alone can lead to wrong conclusions about a model's validity [6].

- Ill-conditioning and Overfitting: This pathology occurs when a model has too many parameters relative to the available data, when the data itself is noisy or information-poor, or when the model is overly flexible. An ill-conditioned problem is highly sensitive to small perturbations, causing small measurement errors to result in large, often unrealistic, variations in the estimated parameters. This frequently leads to overfitting, where the model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying biological signal, severely damaging its predictive performance and generalizability [6].

- Sloppiness: A "sloppy" model is one whose behavior is governed by a few "stiff" parameter combinations but is largely unaffected by changes in many "sloppy" directions in parameter space. When the sensitivity eigenvalues of a model are roughly evenly spaced over many decades on a logarithmic scale, the parameter confidence regions form extremely elongated, high-dimensional ellipsoids. This indicates that many different parameter sets can yield virtually identical model behaviors, making individual parameters difficult to identify from collective fits, even with ideal data [7].

Quantitative Manifestations in Systems Biology

Table 1: Quantitative Signatures of Nonconvexity, Ill-conditioning, and Sloppiness

| Pathology | Mathematical Signature | Typical Observation in Systems Biology Models |

|---|---|---|

| Nonconvexity | Multiple local minima in the cost function landscape. | An optimization algorithm converges to vastly different parameter values and objective function values from different starting points [6]. |

| Ill-conditioning | Large condition number of the Hessian (or Fisher Information) matrix; High variance in parameter estimates from slightly different datasets. | Overfitting: Excellent fit to calibration data but poor prediction on validation data. Parameter values can become physically implausible (e.g., negative rate constants) [6]. |

| Sloppiness | Eigenvalue spectrum of the Hessian matrix spans many decades (e.g., >10⁶). A few large (stiff) eigenvalues, many near-zero (sloppy) eigenvalues [7]. | Collective fitting to data leaves many individual parameters poorly constrained (wide confidence intervals), yet can still yield well-constrained predictions for specific model outputs [7]. |

Empirical studies have demonstrated that sloppiness is a universal feature across diverse systems biology models. An analysis of 17 models from the literature, covering circadian rhythms, metabolism, and signaling, found that every model exhibited a sloppy sensitivity spectrum [7].

Computational Methodologies & Protocols

A Robust Parameter Estimation Pipeline

The following workflow integrates specific strategies to combat nonconvexity and ill-conditioning, incorporating regular checks for sloppiness.

Diagram Title: Robust Parameter Estimation Workflow

Protocol 1: Combating Nonconvexity with Global Optimization

Objective: To locate the global minimum (or a high-quality local minimum) of a nonconvex objective function, avoiding convergence to suboptimal solutions.

Materials:

- Software: Global optimization software (e.g.,

MEIGOin MATLAB,scipy.optimize.differential_evolutionin Python,SloppyCell[7]). - Computational Resources: Multi-core workstations or high-performance computing (HPC) clusters for parallel function evaluations.

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define the objective function, typically a weighted sum of squares:

χ²(θ) = Σ (y_data(t_i) - y_model(t_i, θ))² / σ_i², whereθis the parameter vector. - Parameter Bounding: Set physiologically or mathematically plausible lower and upper bounds for all parameters.

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a global optimization algorithm. A multi-start approach of a local optimizer is sometimes effective for simpler problems, but for more complex landscapes, the following are recommended [6] [8]:

- Genetic Algorithms (GA): Population-based, inspired by natural selection.

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): Inspired by social behavior of bird flocking.

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): Particularly efficient for expensive objective functions, as it builds a surrogate model to guide the search [9].

- Execution: Run the global optimizer with a sufficiently large population size/number of iterations to ensure adequate exploration of the parameter space.

- Validation: Run the optimization from multiple, widely spaced initial points to check for consistency in the final objective function value.

Protocol 2: Mitigating Ill-conditioning and Overfitting via Regularization

Objective: To incorporate prior knowledge and constrain parameter values, thereby reducing overfitting and improving model generalizability.

Materials:

- Software: Optimization software that allows for constrained and regularized problem formulation (e.g., MATLAB Optimization Toolbox, Python's

scipy.optimize.minimize). - Information: Prior knowledge on parameter values (e.g., from literature or separate experiments).

Procedure:

- Define Regularization Scheme: Augment the original least-squares objective function with a penalty term.

- Standard Form:

θ* = argmin [ χ²(θ) + λ * Ω(θ) ], whereΩ(θ)is the regularization term andλis the regularization strength.

- Standard Form:

- Select Regularization Method:

- L2-Regularization (Tikhonov):

Ω(θ) = Σ (θ_i - θ_{prior,i})². This pulls parameters towards a prior estimate, smoothing the solution. Ideal when parameters are expected to be near known values [6]. - L1-Regularization (Lasso):

Ω(θ) = Σ |θ_i - θ_{prior,i}|. This promotes sparsity, effectively driving less important parameters to zero, which is useful for feature selection in network inference.

- L2-Regularization (Tikhonov):

- Tune Regularization Strength (λ): Use the validation dataset to tune

λ. A common method is L-curve analysis: plotχ²vs.Ω(θ)for a range ofλvalues and choose aλat the "corner" of the resulting L-shaped curve, balancing fit quality and solution complexity. - Cross-Validation: The final model, calibrated with the chosen

λ, must be tested on a completely independent validation dataset not used during the calibration orλ-tuning process.

Protocol 3: Diagnosing and Interpreting Sloppiness

Objective: To compute the sensitivity spectrum of a model and analyze its parameter identifiability.

Materials:

- Software:

SloppyCell[7] or custom code in MATLAB/Python to compute the Hessian matrix and its eigenvalues/eigenvectors. - Requirement: A locally optimized parameter set

θ*.

Procedure:

- Compute the Hessian: Calculate the Hessian matrix

Hof the objective functionχ²(θ)at the optimized parametersθ*.H_ij = ∂²χ² / ∂θ_i ∂θ_j. Derivatives are typically taken with respect tolog(θ)to account for parameters spanning different scales [7]. - Eigenvalue Decomposition: Perform an eigenvalue decomposition of the Hessian:

H = VΛVᵀ, whereΛis a diagonal matrix of eigenvaluesλ_k, andVcontains the corresponding eigenvectors. - Analyze the Spectrum: Plot the eigenvalues on a logarithmic scale. A sloppy model will show eigenvalues roughly evenly spaced over many orders of magnitude (e.g., from 10⁰ to 10⁻¹²) [7].

- Interpret Eigenvectors: Identify "stiff" (parameters with large eigenvalues) and "sloppy" (parameters with small eigenvalues) combinations. The model's predictions are most sensitive to changes along stiff directions.

- Practical Identifiability Analysis: Generate profile likelihoods for parameters to visually inspect their identifiability. A parameter is practically identifiable if its profile likelihood has a well-defined minimum. Sloppy parameters will have flat profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Their Functions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Experimentation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Global Optimizer (e.g., GA, PSO) | Navigates nonconvex cost function landscapes to find the best-fit parameters, avoiding local minima traps. | Model tuning of a large-scale kinetic model of a signaling pathway [6] [8]. |

| Regularization Algorithm | Introduces constraints based on prior knowledge, reducing overfitting and improving model generalizability. | Preventing overparametrization in a hybrid model combining ODEs and neural networks [6] [9]. |

| Hessian Matrix Calculator | Quantifies the local curvature of the objective function, enabling diagnosis of sloppiness and ill-conditioning. | Identifiability analysis of parameters in a model of yeast glycolytic oscillations [7] [9]. |

| Hybrid Neural ODE (HNODE) Framework | Embeds an incomplete mechanistic model within a neural network to represent unknown dynamics. | Parameter estimation for a partially known biological system, such as a cell apoptosis model [9]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Samples from the posterior distribution of parameters, providing uncertainty quantification. | Estimating confidence intervals for parameters in a stochastic model of gene regulation [8]. |

Advanced Tool: Hybrid Neural ODEs for Incomplete Models

When mechanistic knowledge is incomplete, a powerful emerging approach is to use Hybrid Neural ODEs (HNODEs). The differential equation takes the form:

dy/dt = f_mechanistic(y, t, θ_M) + NN(y, t, θ_NN)

where the neural network NN acts as a universal approximator for the unknown system dynamics [9]. The primary challenge is ensuring the identifiability of the mechanistic parameters θ_M amidst the flexibility of the neural network. The protocol involves treating θ_M as hyperparameters and using Bayesian Optimization for a global search, followed by rigorous a posteriori identifiability analysis [9].

Diagram Title: Hybrid Neural ODE Architecture

Nonconvexity, ill-conditioning, and sloppiness are not mere mathematical curiosities but fundamental properties that define the difficulty of parameter estimation in systems biology. Successfully navigating these challenges requires a disciplined, multi-pronged strategy. As outlined in this note, this strategy must combine efficient global optimization to handle nonconvexity, judicious regularization to combat ill-conditioning and overfitting, and rigorous sloppiness and identifiability analysis to correctly interpret the constraints placed on parameters by data. By adopting these protocols, researchers can build more robust, reliable, and predictive models, thereby accelerating the cycle of discovery and development in biomedical research. The future lies in the tighter integration of these methods, such as embedding identifiability analysis directly within global optimization routines and leveraging hybrid modeling frameworks to progressively refine biological knowledge.

In the field of systems biology, the calibration of dynamic models to experimental data—known as parameter estimation—represents one of the most critical yet challenging inverse problems. This process aims to find the unknown parameters of a biological model that yield the best fit to experimental data, typically by minimizing a cost function that measures the quality of the fit [10]. However, this inverse problem exhibits two key pathological characteristics: ill-conditioning and nonconvexity, which often lead to the phenomenon of overfitting [10].

Overfitting occurs when a model learns not only the underlying system dynamics but also the noise and unusual features present in the training data [11]. In systems biology, this manifests as calibrated models that demonstrate reasonable fits to available calibration data but possess poor generalization capability and low predictive value when applied to new datasets or experimental conditions [10]. The consequences are particularly severe in biological research and drug development, where overfitted models can lead to erroneous conclusions about immunological markers, incorrect predictions of drug binding, and ultimately, costly failures in therapeutic development [11] [12].

Mechanistic dynamic models in systems biology are particularly prone to overfitting due to three primary factors: (1) models with large numbers of parameters (over-parametrization), (2) experimental data scarcity inherent in biological experiments, and (3) significant measurement errors common in laboratory techniques [10]. The flexibility of modern modeling approaches, including hybrid models that combine mechanistic knowledge with machine learning components, further increases susceptibility to overfitting if not properly regulated [9] [13].

Quantifying and Detecting Overfitting

Fundamental Indicators of Overfitting

The primary indicator of overfitting is a significant discrepancy between a model's performance on training data versus its performance on validation or test data. A model that demonstrates excellent fit to training data but poor performance on unseen data has likely overfitted [11] [14]. In classification tasks, this may appear as high accuracy, precision, and recall on training data but substantially lower metrics on validation data [15].

In parameter estimation for dynamic models, overfitting can be detected through predictive validation, where the calibrated model is tested against a completely new dataset that was not used during parameter estimation [10]. Unfortunately, this crucial validation step is often omitted in systems biology literature, making it difficult to assess the true predictive capability of published models.

Advanced Metrics for Overfitting Potential

Recent research has developed specialized metrics to quantify the potential for overfitting in specific biological applications. For drug binding predictions, the Asymmetric Validation Embedding (AVE) bias metric quantifies dataset topology and potential biases that may lead to overoptimistic performance estimates [12]. The AVE bias analyzes the spatial distribution of active and decoy compounds in the training and validation sets, with values near zero indicating a "fair" dataset that doesn't allow for easy classification due to clumping [12].

Table 1: Metrics for Quantifying Overfitting Potential

| Metric | Application Domain | Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training-Validation Performance Gap | General purpose | Difference in performance metrics between training and validation sets | Larger gaps indicate stronger overfitting |

| AVE Bias | Drug binding prediction | Spatial analysis of compound distribution in feature space | Values near zero indicate fair dataset; extreme values suggest bias |

| VE Score | Drug binding prediction | Variation of AVE bias designed for optimization | Never negative; lower values suggest less bias |

| G(t) and F(t) Functions | Virtual screening | Nearest neighbor analysis of active and decoy compounds | High G(t) indicates self-similarity; low F(t) indicates separation |

For machine learning applications in biology, performance metrics such as precision-recall curves and associated area under the curve (AUC) scores must be interpreted with caution, as they can be overly optimistic when models overfit to training data [15] [12]. The nearest neighbor (NN) model serves as a useful benchmark, as it essentially memorizes training data and exhibits poor generalizability; if a complex model performs similarly to NN on challenging validation splits, it may be overfitting [12].

Methodological Strategies to Prevent Overfitting

Regularization Techniques

Regularization is one of the most powerful and widely used techniques for preventing overfitting by reducing effective model complexity [11]. It works by adding a penalty term to the loss function to discourage the model from learning overly complex patterns that may capture noise rather than signal.

The general form of regularized loss function can be represented as:

[ L{\lambda}(\beta) = \frac{1}{2}\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi\beta - yi)^2 + \lambda J(\beta) ]

Where ( \lambda ) controls the strength of regularization and ( J(\beta) ) is the penalty term [11].

Table 2: Regularization Methods for Preventing Overfitting

| Method | Penalty Term ( J(\beta) ) | Application Context | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ridge Regression | ( \sum{j=1}^{p}\betaj^2 ) | General parameter estimation | Stabilizes estimates; handles correlated parameters |

| Lasso Regression | ( \sum{j=1}^{p}|\betaj| ) | Feature selection; high-dimensional data | Encourages sparsity; automatic feature selection |

| Elastic Net | ( \alpha\sum|\betaj| + (1-\alpha)\sum\betaj^2 ) | Biological data with correlated features | Balances sparsity and correlation handling |

| Weight Decay | ( \lambda|\theta{ANN}|2^2 ) | Neural networks in hybrid models | Prevents neural network from dominating mechanistic components |

In hybrid neural ordinary differential equations (HNODEs) and universal differential equations (UDEs), regularization plays a crucial role in maintaining the balance between mechanistic and data-driven components. Applying weight decay regularization to neural network parameters prevents the network from inadvertently capturing dynamics that should be attributed to the mechanistic model, thereby preserving interpretability of mechanistic parameters [9] [13].

Data-Centric Approaches

Data augmentation represents another powerful strategy to combat overfitting, particularly when working with limited biological datasets. In genomics and proteomics, innovative augmentation techniques can artificially expand dataset size and diversity without altering fundamental biological information [15]. For sequence data, this may involve generating overlapping subsequences with controlled overlaps and shared nucleotide features through sliding window techniques [15].

Proper data splitting methodologies are crucial for reliable model evaluation. Rather than simple random splitting, approaches such as the ukySplit-AVE and ukySplit-VE algorithms use genetic optimization to create training/validation splits that minimize spatial biases in the data, resulting in more realistic performance estimates [12].

Cross-validation techniques provide more robust estimates of model performance by repeatedly splitting data into training and validation sets. For dynamic models in systems biology, time-series cross-validation approaches that preserve temporal dependencies are particularly valuable [10].

Model Architecture and Training Strategies

Controlling model complexity through dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or autoencoders can effectively reduce overfitting by limiting the number of free parameters [11] [16].

Early stopping during model training prevents overfitting by terminating the optimization process when performance on a validation set stops improving [11]. This approach is particularly valuable for training complex neural network components in hybrid models [13].

In parameter estimation for dynamic models, global optimization methods help avoid convergence to local solutions that may represent overfitted parameter sets [10]. Multi-start strategies that sample initial parameter values from broad distributions improve exploration of the parameter space and reduce the risk of selecting overfitted local minima [10] [13].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Parameter Estimation

Workflow for Hybrid Model Development

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for parameter estimation in hybrid mechanistic-data-driven models, incorporating multiple strategies to prevent overfitting:

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for robust parameter estimation in hybrid models, incorporating multiple strategies to prevent overfitting.

Protocol: Parameter Estimation with HNODEs

Objective: Estimate mechanistic parameters in partially known biological systems using Hybrid Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (HNODEs) while preventing overfitting.

Background: HNODEs combine mechanistic ODE-based dynamics with neural network components to model systems with incomplete mechanistic knowledge [9]. The general form is:

[ \frac{dy}{dt}(t) = f^M(y,t,\theta^M) + NN(y,t,\theta^{NN}) ]

Where ( f^M ) represents the mechanistic component, ( NN ) is the neural network, ( \theta^M ) are mechanistic parameters, and ( \theta^{NN} ) are neural network parameters [9].

Materials and Reagents:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for HNODE Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| ODE Solver | Numerical integration of differential equations | Tsit5, KenCarp4 for stiff systems [13] |

| Optimization Framework | Parameter estimation and training | SciML, TensorFlow, PyTorch [16] [13] |

| Global Optimizer | Exploration of parameter space | Bayesian Optimization, Genetic Algorithms [9] |

| Regularization Method | Prevent overfitting of neural components | Weight decay (L2 regularization) [13] |

| Parameter Transformation | Handle parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude | Log-transformation, tanh-based bounding [13] |

Procedure:

Model Formulation:

- Define the known mechanistic structure ( f^M(y,t,\theta^M) ) based on biological knowledge

- Identify unknown system components to be represented by the neural network ( NN(y,t,\theta^{NN}) )

- Specify observable variables and measurement error models [9]

Data Preprocessing:

Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Implement Bayesian Optimization to simultaneously tune hyperparameters and explore mechanistic parameter space

- Sample initial values for both mechanistic parameters ( \theta^M ) and neural network parameters ( \theta^{NN} ) from appropriate prior distributions [9]

- Include regularization strength ( \lambda ) as a hyperparameter to be optimized [13]

Model Training:

- Implement a multi-start optimization strategy to mitigate local minima convergence [13]

- Apply weight decay regularization to neural network parameters: ( L{total} = L{data} + \lambda \|\theta{ANN}\|2^2 ) [13]

- Use early stopping based on validation set performance to prevent overfitting [11]

- Employ specialized ODE solvers (e.g., Tsit5 for non-stiff, KenCarp4 for stiff systems) for numerical integration [13]

Identifiability Analysis:

- Conduct a posteriori identifiability analysis using profile likelihood or Fisher Information Matrix approaches [9]

- Classify parameters as identifiable or non-identifiable based on analysis results

- For identifiable parameters, estimate confidence intervals using asymptotic approximations or likelihood-based methods [9]

Model Validation:

- Evaluate model performance on completely independent test data not used during training

- Assess generalization capability under different experimental conditions or perturbations

- Compare model predictions against additional experimental observations [10]

Troubleshooting:

- If mechanistic parameters show poor identifiability, consider increasing regularization strength or incorporating additional prior information

- If training fails to converge, adjust learning rates or implement adaptive optimization algorithms

- For numerically stiff systems, switch to specialized stiff ODE solvers and ensure proper parameter scaling [13]

Case Studies in Systems Biology

Glycolysis Oscillation Model

The glycolysis model by Ruoff et al., consisting of seven ordinary differential equations with twelve free parameters, provides an excellent test case for HNODE approaches [13]. In this application, the ATP usage and degradation terms can be replaced with a neural network component that takes all seven state variables as inputs. To recover the true solution, the neural network must learn a dependency on only ATP, while the mechanistic parameters for the remaining components are estimated [13]. Regularization is crucial to prevent the neural network from compensating for errors in the mechanistic parameter estimates, which would lead to overfitting and loss of biological interpretability.

Drug Binding Prediction

In drug binding prediction, overfitting presents a significant challenge due to the high-dimensional nature of chemical descriptor space and limited experimental data [12]. The application of spatial bias metrics like AVE bias has revealed that standard random splits of training and validation data often produce overly optimistic performance estimates [12]. By implementing optimized splitting algorithms (ukySplit-AVE, ukySplit-VE) that minimize spatial biases, researchers can obtain more realistic estimates of model performance on truly novel compounds, thereby reducing overfitting and improving predictive capability in virtual screening [12].

Predictive Immunology

In immunological applications such as predicting vaccination response, overfitting can lead to identification of spurious biomarkers that fail to generalize to new datasets [11]. For example, when using XGBoost to identify PBMC transcriptomics signatures for predicting antibody responses, models with higher complexity (tree depth of 6) achieved nearly perfect training performance but worse validation performance compared to simpler models (tree depth of 1), demonstrating clear overfitting [11]. Regularization through early stopping or penalty terms, combined with appropriate validation strategies, is essential to ensure identified immunological signatures possess genuine predictive power.

In systems biology and drug development, mathematical models are crucial for understanding complex biological processes. These models, often represented as parametrized ordinary differential equations (ODEs), are calibrated using experimental data to estimate unknown parameters [17]. However, a critical question arises: can these parameters be uniquely determined from the available data? This is the fundamental problem of parameter identifiability.

Identifiability analysis is a group of methods used to determine how well model parameters can be estimated based on the quantity and quality of experimental data [18]. It is essential for ensuring reliable parameter estimation, model validation, and credible predictions [19]. The concept is broadly divided into two main categories: structural identifiability and practical identifiability.

Understanding the distinction between these concepts and knowing how to assess them is vital for researchers aiming to build predictive models that can reliably inform drug development decisions and biological discovery.

Definitions and Core Concepts

Structural Identifiability

Structural identifiability is a theoretical property of a model that examines whether its parameters can be uniquely determined from ideal, noise-free, and continuous input-output data [19] [17]. It is a prerequisite for reliable parameter estimation and depends solely on the model structure itself, independent of any specific dataset [18].

- Globally Identifiable: A parameter is globally identifiable if its value can be uniquely determined from perfect data across the entire parameter space. Formally, for a model mapping parameters

θto outputy(t; θ), ify(t; θ₁) = y(t; θ₂)for alltimpliesθ₁ = θ₂always, the model is globally identifiable [19]. - Locally Identifiable: A parameter is locally identifiable if its value can be determined from perfect data, but only within a neighborhood of its true value, potentially allowing for a finite number of solutions [19] [17].

- Unidentifiable: A parameter is unidentifiable if an infinite number of possible values can yield the same model output, making its true value impossible to determine even with perfect data [17].

A simple example illustrates these concepts [17]:

- For the model

y(t) = a × 2, parameterais globally identifiable (one unique solution). - For

y(t) = a² × 2, parameterais locally identifiable (two solutions: positive and negative). - For

y(t) = a + b, parametersaandbare unidentifiable (infinitely many combinations sum to the samey(t)).

Practical Identifiability

Practical identifiability moves from theory to reality. It assesses whether model parameters can be estimated with reasonable confidence and precision given real-world experimental data, which is finite, noisy, and may be collected at suboptimal time points [20] [18].

A model can be structurally identifiable but practically unidentifiable if the available data are insufficiently informative, too noisy, or poorly designed [19] [20]. Therefore, structural identifiability is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for practical identifiability [19].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Structural and Practical Identifiability

| Feature | Structural Identifiability | Practical Identifiability |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Concern | Model structure and theoretical capability | Sufficiency and quality of actual data |

| Data Assumption | Ideal, noise-free, continuous data | Real, noisy, finite, discrete data |

| Analysis Type | A priori (before data collection) | A posteriori (after or during data collection) |

| Dependence | Independent of specific data quality | Highly dependent on data quality and design |

| Question Answered | "Can parameters be uniquely estimated with perfect data?" | "Can parameters be estimated precisely with my available data?" |

Methodologies for Identifiability Analysis

A range of methods has been developed to assess both structural and practical identifiability, each with different strengths, requirements, and software implementations.

Methods for Structural Identifiability Analysis

- Differential Algebra (Input-Output) Approach: This method eliminates unobserved state variables to produce an input-output relation, a differential equation where the coefficients are functions of the parameters. Structural identifiability is confirmed if the mapping from parameters to these coefficients is injective (one-to-one) [19] [21]. It is implemented in tools like

StructuralIdentifiability.jland DAISY [22] [21]. - Observability-Based (Differential Geometric) Approach: This method treats parameters as constant state variables, recasting identifiability as an observability problem. It constructs a generalized observability-identifiability matrix using Lie derivatives of the output. If this matrix has full rank (equal to the number of states plus parameters), the model is structurally identifiable [19].

- Scaling Method: A simpler analytical method that tests the invariance of the model equations under scaling transformations of its parameters. If a scaling transformation leaves the equations unchanged, the involved parameters are unidentifiable. This method is accessible and can be applied without specialized software for many models [23].

Methods for Practical Identifiability Analysis

- Profile Likelihood: This is a powerful and widely used method for assessing practical identifiability. It profiles a parameter of interest by optimizing the likelihood function over all other parameters while constraining the focal parameter to a range of fixed values. A flat profile indicates that the parameter is practically unidentifiable, as a range of values are equally plausible given the data [20].

- Fisher Information Matrix (FIM): The FIM measures the amount of information that observable data carries about the unknown parameters. A FIM that is singular or has very small eigenvalues indicates unidentifiable parameters. The FIM can be approximated from local sensitivities [22].

- Monte Carlo Simulations: This approach involves repeatedly fitting the model to data simulated with different noise realizations. If the estimated parameters across runs show large variances or biases, it indicates practical unidentifiability [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Identifiability Analysis Methods

| Method | Applies to | Key Principle | Example Tools / Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Algebra | Structural | Eliminates states to get input-output equations; checks injectivity of coefficient map | DAISY, StructuralIdentifiability.jl [19] [22] |

| Observability Matrix | Structural | Treats parameters as states; checks rank of Lie derivative matrix | GenSSI, custom code [19] |

| Scaling Method | Structural | Tests model invariance under parameter scaling transformations | Analytical calculations [23] |

| Profile Likelihood | Practical | Optimizes likelihood while profiling a parameter to check for flat regions | dMod (R), MEIGO (MATLAB), custom scripts [20] |

| Fisher Info. Matrix (FIM) | Both (Primarily Practical) | Analyzes curvature of likelihood surface from local sensitivities | Custom code in R/MATLAB, PottersWheel [22] |

Figure 1: A recommended workflow for identifiability analysis in model development. Structural analysis is a prerequisite before proceeding to practical analysis with real data. Unidentifiable models require redesign before reliable parameter estimation can proceed. Adapted from [17].

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Structural Identifiability of a Phenomenological Growth Model

Background: Phenomenological growth models (e.g., Generalized Growth Model, Richards model) are widely used in epidemiology to forecast disease trajectories. Their reliability depends on the identifiability of their parameters [21].

Objective: To determine the structural identifiability of the Generalized Growth Model (GGM) reformulated for incidence data.

Materials & Methods

- Model: The GGM for cumulative cases

C(t)isdC/dt = rC^α. For incidence data, the observed output isy(t) = dC/dt. To handle the non-integer exponentα, the model is reformulated by introducing a new state variablex(t) = rC^α, leading to the extended ODE system [21]:dC/dt = x(t)dx/dt = αx²(t)/C(t)

- Software:

StructuralIdentifiability.jlpackage in Julia [21]. - Procedure:

- Input the extended ODE system into

StructuralIdentifiability.jl, specifyingy(t) = x(t)as the observation. - The software uses the differential algebra approach to compute the input-output equation.

- Analyze the output, which confirms that the parameters

randαare structurally globally identifiable from the incidence data given this model reformulation [21].

- Input the extended ODE system into

Interpretation: The theoretical assurance of structural identifiability means that with perfect, noise-free incidence data, the parameters r and α can be uniquely estimated. This is a necessary first step before attempting to fit the model to real data.

Protocol 2: Designing a Minimally Sufficient Experiment for Practical Identifiability

Background: During drug development, understanding target occupancy (TO) in the tumor microenvironment (TME) is critical for efficacy. A site-of-action pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PKPD) model can link plasma PK to TME PD, but its parameters must be practically identifiable from feasible experiments [20].

Objective: To identify a minimal set of time points for measuring % TO in the TME that ensures the practical identifiability of key parameters (k_onT, rate of drug-target complex formation; k_synt, rate of target synthesis).

Materials & Methods

- Model: A validated, modified site-of-action PKPD model for pembrolizumab [20].

- Software: Tools for profile likelihood analysis (e.g., custom scripts in R, MATLAB, or Python).

- Procedure [20]:

- Generate Ideal Data: Use the validated model to simulate a dense, high-quality "ideal" dataset for % TO in the TME. Confirm that with this ideal data, the parameters of interest are practically identifiable (e.g., via profile likelihood).

- Subsample Time Points: Systematically test subsets of the ideal time points.

- Profile Likelihood Assessment: For each candidate subset of time points, perform profile likelihood analysis for parameters

k_onTandk_synt. - Identify Minimal Set: Select the smallest subset of time points that results in well-defined, sharp minima in the profile likelihood plots, indicating practical identifiability comparable to the full ideal dataset.

Interpretation: This model-informed approach pinpoints the most informative time points for data collection. It ensures parameter identifiability while minimizing experimental costs and burdens, such as the number of required biopsies [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Software and Reagent Solutions for Identifiability Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

StructuralIdentifiability.jl |

Software Library (Julia) | Structural Identifiability Analysis | Implements differential algebra approach; handles high-dimensional ODE models [19] [21]. |

| DAISY | Software Tool | Structural Identifiability Analysis | Differential Algebra for Identifiability of SYstems; effective for rational ODE models [19] [22]. |

| Profile Likelihood | Algorithm/Method | Practical Identifiability Analysis | Assesses practical identifiability by exploring parameter likelihood profiles; can be implemented in various environments [20]. |

| GrowthPredict Toolbox | Software Toolbox (MATLAB) | Parameter Estimation & Forecasting | Fits and forecasts using phenomenological growth models; useful for validating identifiability in practice [21]. |

| Validated PKPD Model | Research Reagent (In Silico) | Model Template & Validation | A pre-validated model (e.g., the site-of-action model for pembrolizumab) serves as a starting point for simulation and experimental design [20]. |

Rigorous identifiability analysis is not an optional step but a fundamental component of robust mathematical modeling in systems biology and drug development. Structural identifiability provides the theoretical foundation, confirming that a model is well-posed for parameter estimation. Practical identifiability grounds the process in reality, ensuring that the available data are sufficient to yield reliable parameter estimates.

As demonstrated in the application notes, modern software tools and methodologies make this analysis accessible. By integrating these protocols into the modeling workflow—starting with structural analysis, followed by practical assessment and optimal experimental design—researchers can build more credible models. This rigor ultimately leads to more trustworthy predictions, accelerating drug discovery and enhancing our understanding of complex biological systems.

A Toolkit of Optimization Algorithms: From Gradient-Based to Metaheuristic Methods

Parameter estimation is a central challenge in computational biology, essential for transforming conceptual mathematical models into predictive tools that can recapitulate experimental data. In the context of biological systems characterized by nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with many unknown parameters, gradient-based optimization methods provide a powerful framework for identifying parameter values that best fit experimental observations. These methods leverage derivative information to navigate the high-dimensional parameter spaces efficiently, minimizing an objective function that quantifies the discrepancy between model simulations and experimental data. Among the most prominent techniques are the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, L-BFGS-B, and approaches utilizing adjoint sensitivity analysis, each offering distinct advantages for specific problem structures and scales common in biological modeling.

The fundamental parameter estimation problem in systems biology involves determining the vector of parameters θ that minimizes a cost function, typically formulated as a weighted sum of squares: ( C(θ) = \frac{1}{2}∑i ωi(yi - ŷi(θ))^2 ), where ( yi ) are experimental measurements, ( ŷi(θ) ) are corresponding model predictions, and ( ωi ) are weighting constants, often chosen as ( 1/σi^2 ) where ( σ_i^2 ) is the measurement variance [24] [25]. For models of immunoreceptor signaling, gene regulatory networks, or metabolic pathways, this optimization problem becomes particularly challenging due to the nonlinear nature of biological dynamics, often yielding cost functions with multiple local minima and complex topography.

Theoretical Foundations

Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm

The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm represents a hybrid approach that interpolates between gradient descent and Gauss-Newton methods, making it particularly suited for nonlinear least-squares problems prevalent in biological modeling. This algorithm adaptively adjusts its step size and direction based on the local landscape of the parameter space, employing a damping parameter that controls the trust region for quadratic approximations of the cost function. When the damping parameter is large, the method behaves like gradient descent, taking cautious steps in the direction of steepest descent. As the damping parameter decreases, it transitions toward the Gauss-Newton method, leveraging approximate second-order information for faster convergence near minima [24].

The key strength of Levenberg-Marquardt lies in its specialized formulation for least-squares objectives, where the Hessian matrix is approximated using first-order Jacobian information, avoiding the computational expense of calculating exact second derivatives. This makes it particularly effective for problems where the residuals (differences between model predictions and experimental data) are small near the solution, a common scenario in well-posed biological estimation problems. However, its performance depends critically on the accurate computation of Jacobians, which can be challenging for large-scale biological models with many parameters and state variables [24].

L-BFGS-B Algorithm

L-BFGS-B (Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno with Bound constraints) belongs to the family of quasi-Newton optimization methods that build an approximation of the Hessian matrix using gradient information from previous iterations. The "limited-memory" variant is specifically designed for high-dimensional problems where storing the full Hessian approximation would be computationally prohibitive. Instead, L-BFGS-B maintains a compact representation using a history of gradient vectors, making it suitable for biological models with tens to hundreds of parameters [24].

A distinctive advantage of L-BFGS-B is its native support for bound constraints on parameters, which is particularly valuable in biological contexts where parameters often represent physical quantities like reaction rates, Michaelis-Menten constants, or Hill coefficients that must remain within physiologically plausible ranges [24] [26]. Unlike Levenberg-Marquardt, L-BFGS-B is applicable to general optimization problems beyond least-squares formulations, providing flexibility in designing objective functions that might incorporate additional penalty terms or regularization components to enforce parameter bounds or biological constraints [25].

Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis

Adjoint sensitivity analysis provides a computationally efficient method for calculating gradients of objective functions with respect to parameters in ODE-based models, especially when the number of parameters greatly exceeds the number of observable outputs. The method involves solving the original system forward in time, then solving an adjoint system backward in time to compute the necessary sensitivities [24] [27].

The computational advantage of the adjoint method becomes pronounced for large-scale biological models, as its cost is effectively independent of the number of parameters, scaling only with the number of observed states. This contrasts with forward sensitivity analysis, which requires solving a system of sensitivity equations for each parameter, becoming prohibitively expensive for models with many parameters [24]. Recent applications have demonstrated that adjoint sensitivity analysis enables parameterization of large biological models, including those derived from rule-based frameworks that often generate hundreds of ODEs [24].

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Gradient-Based Optimization Methods

| Method | Algorithm Type | Primary Strengths | Optimal Use Cases | Software Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levenberg-Marquardt | Second-order, specialized for least-squares | Fast convergence for medium-scale problems; adaptive trust-region strategy | Models with explicit least-squares formulation; small to medium parameter spaces | AMICI, Data2Dynamics, COPASI |

| L-BFGS-B | Quasi-Newton, general purpose | Memory efficiency for high-dimensional problems; native bound constraints | Large-scale models; parameters with physical bounds; general objective functions | PyBioNetFit, PESTO, COPASI |

| Adjoint Sensitivity | Gradient computation method | Efficiency independent of parameter number; suitable for very large models | Models with many parameters but limited observables; stiff ODE systems | AMICI, SciML (Julia) |

Table 2: Performance Considerations for Biological Applications

| Aspect | Levenberg-Marquardt | L-BFGS-B | Adjoint Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Scaling | O(p²) for Jacobian calculations | O(p·m) for gradient approximation (m: memory size) | Independent of p, scales with state dimension |

| Handling of Local Minima | Prone to convergence to local minima; requires multistart | Better at navigating complex landscapes; benefits from multistart | Similar challenges; multistart recommended |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate (requires Jacobian) | Low to moderate (gradients only) | High (requires adjoint system formulation) |

| Robustness to Noise | Moderate | High | Moderate to high |

The selection of an appropriate optimization method depends critically on the specific characteristics of the biological modeling problem. Levenberg-Marquardt excels in problems with explicit least-squares formulation and moderate parameter dimensions, leveraging its specialized structure for efficient convergence. L-BFGS-B offers greater flexibility for general optimization problems with bound constraints, making it suitable for high-dimensional parameter estimation where parameters represent physical quantities with natural boundaries. Adjoint methods provide unparalleled efficiency for models with very large parameter spaces, particularly when the number of observable outputs is limited, as their computational cost is effectively independent of the number of parameters [24].

For problems with non-convex objective functions featuring multiple local minima—a common scenario in biological parameter estimation—all methods benefit from multistart optimization, where multiple independent replicates are initiated from different starting points in parameter space [24]. This approach increases the probability of locating the global minimum rather than becoming trapped in suboptimal local minima.

Protocols for Implementation

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation Using Levenberg-Marquardt

Application Note: This protocol is optimized for medium-scale ODE models (5-50 parameters) with time-series data where a least-squares objective function is appropriate.

Step 1: Model Formulation and Data Preparation

- Format the biological model in a standardized representation such as SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) or BNGL (BioNetGen Language) to ensure compatibility with analysis tools [24].

- Define the objective function as a weighted sum of squares: ( C(θ) = \frac{1}{2}∑i ωi(yi - ŷi(θ))^2 ), where weights ( ωi ) are typically chosen as ( 1/σi^2 ) based on measurement variances [24] [25].

- For parameters with known physical constraints, add penalty terms to the objective function to guide optimization away from non-physical regions [25].

Step 2: Jacobian Calculation

- Compute the Jacobian matrix using forward sensitivity analysis, which augments the original ODE system with sensitivity equations for each parameter [24].

- For systems with many parameters, consider finite difference approximation as a simpler but less efficient alternative [24].

- Implement in software such as COPASI or Data2Dynamics, which provide built-in sensitivity analysis capabilities [24].

Step 3: Optimization Setup

- Initialize parameters with biologically plausible values, potentially sampling from a log-uniform distribution if parameters span multiple orders of magnitude [25] [28].

- Set the initial damping parameter (λ) to a small value (e.g., 0.001) unless the problem is known to be poorly conditioned [24].

- Define convergence criteria, typically based on relative change in parameter values (e.g., <10⁻⁶) or objective function reduction [25].

Step 4: Iterative Optimization

- At each iteration, compute the Jacobian matrix J and approximate the Hessian as H ≈ JᵀJ [24].

- Solve the linear system (JᵀJ + λI)δ = -Jᵀr for the parameter update δ, where r is the residual vector [24].

- If the step reduces the objective function, accept it and decrease λ by a factor of 10; if not, reject the step and increase λ by a factor of 10 [24].

- Continue until convergence criteria are met.

Step 5: Validation and Uncertainty Quantification

- Perform multistart optimization from different initial parameter values to assess consistency of solutions [24].

- Quantify parameter uncertainties using profile likelihood or bootstrapping methods [24] [9].

- Validate optimized parameters against a withheld validation dataset to assess predictive capability [9].

Protocol 2: Large-Scale Optimization with L-BFGS-B

Application Note: This protocol is designed for high-dimensional problems (50+ parameters) where bound constraints on parameters are essential for biological plausibility.

Step 1: Problem Formulation with Constraints

- Establish lower and upper bounds for each parameter based on biological knowledge (e.g., reaction rates must be positive, Hill coefficients typically between 1-4) [26].

- Formulate the objective function, which can extend beyond least-squares to include regularization terms or other biologically motivated penalties [25].

- For parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude, implement log-transformation to improve numerical conditioning [28].

Step 2: Gradient Computation

- Calculate gradients using the most efficient available method for the specific model structure:

- For hybrid mechanistic/data-driven models (Universal Differential Equations), leverage automatic differentiation through frameworks like SciML [28].

Step 3: L-BFGS-B Configuration

- Set the memory parameter (m), typically between 5-20, representing the number of previous iterations used to approximate the Hessian [24].

- Configure termination criteria, including gradient tolerance (e.g., 10⁻⁵) and parameter change tolerance [24].

- For stochastic models, ensure objective function evaluations are sufficiently averaged to reduce noise [26].

Step 4: Iterative Optimization with Bound Constraints

- At each iteration, L-BFGS-B builds a limited-memory approximation of the Hessian using the history of gradient vectors [24].

- The algorithm computes a search direction that respects the bound constraints on parameters [24].

- A line search procedure ensures sufficient decrease in the objective function while maintaining feasibility [24].

- Update the memory buffer with current gradient and parameter change information.

Step 5: Solution Refinement and Analysis

- Upon convergence, assess parameter identifiability using Fisher Information Matrix or profile likelihood analysis [25] [9].

- For poorly identifiable parameters, consider additional experimental design to collect more informative data [25].

- Perform local sensitivity analysis around the optimal parameter values to understand their influence on model outputs [24].

Protocol 3: Adjoint-Based Gradient Computation for Large Models

Application Note: This protocol is optimized for models with very large parameter spaces (100+ parameters) where traditional sensitivity analysis becomes computationally prohibitive.

Step 1: Problem Formulation

- Define the objective function, typically as ( C(θ) = ∫_0^T L(x(t),θ,t)dt ), where x(t) are state variables and L defines the misfit between model and data [24] [27].

- For time-series data, L typically represents the squared error at discrete time points [24].

- Ensure the ODE system is well-posed and differentiable with respect to both states and parameters [24].

Step 2: Forward Solution

- Numerically integrate the original system forward in time: ( dx/dt = f(x,θ,t) ), with initial conditions x(0) = x₀ [24] [27].

- Store the state trajectory x(t) at discrete time points, required for the subsequent backward integration [24].

- Use a numerical solver appropriate for potentially stiff biological systems, such as those based on Rosenbrock or BDF methods [28].

Step 3: Adjoint System Solution

- Define the adjoint system: ( dλ/dt = -(∂f/∂x)ᵀλ + (∂L/∂x)ᵀ ), with terminal condition λ(T) = 0 [24] [27].

- Integrate the adjoint system backward in time, using the stored state trajectory from the forward solution [24].

- The adjoint variables λ(t) encode the sensitivity of the objective function to perturbations in the state variables [24].

Step 4: Gradient Computation

- Compute the gradient of the objective function with respect to parameters as: ( dC/dθ = ∫_0^T [∂L/∂θ - λᵀ(∂f/∂θ)] dt ) [24] [27].

- This gradient computation is efficient as it does not require solving additional systems for each parameter [24].

- The computed gradient can be used with any gradient-based optimization algorithm, including gradient descent or L-BFGS-B [24].

Step 5: Integration with Optimization

- Use the computed gradient within a preferred optimization framework to update parameters [24].

- Repeat the forward-adjoint cycle until convergence criteria are satisfied [24].

- For hybrid systems with both continuous and discrete elements, extend the adjoint framework to handle interface conditions [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Gradient-Based Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COPASI | General-purpose biochemical modeling with built-in optimization algorithms | Medium-scale ODE models; user-friendly interface for non-specialists |

| AMICI | High-performance sensitivity analysis for ODE models; compatible with SBML | Large-scale parameter estimation; adjoint sensitivity analysis |

| PyBioNetFit | Parameter estimation with support for rule-based modeling in BNGL | Spatial and rule-based biological models; bound-constrained optimization |

| PESTO | Parameter estimation toolbox for MATLAB with uncertainty analysis | Multistart optimization; profile likelihood-based uncertainty quantification |

| SciML (Julia) | Comprehensive differential equation suite with UDE support | Hybrid mechanistic/machine learning models; cutting-edge adjoint methods |

| Data2Dynamics | Modeling environment focusing on quantitative experimental data | Dynamic biological systems; comprehensive uncertainty analysis |

Visualization of Computational Workflows

Diagram 1: Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm workflow showing the iterative process of parameter updates with adaptive damping.

Diagram 2: Adjoint sensitivity analysis workflow illustrating the forward-backward integration approach for efficient gradient computation.

Diagram 3: Method selection guide for choosing the appropriate gradient-based optimization approach based on problem characteristics.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent advances in gradient-based optimization have expanded their application to increasingly complex biological modeling scenarios. The integration of mechanistic models with machine learning components through Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) represents a particularly promising direction, combining interpretable biological mechanisms with flexible data-driven representations of unknown processes [9] [28]. In these hybrid frameworks, gradient-based optimization enables simultaneous estimation of mechanistic parameters and neural network weights, though careful regularization is required to maintain identifiability of biologically meaningful parameters [9] [28].

For stochastic biological systems, recent developments include differentiable variants of the Gillespie algorithm, which approximate discrete stochastic simulations with continuous, differentiable functions [29]. This innovation enables gradient-based parameter estimation for stochastic biochemical systems, opening new possibilities for fitting models to single-cell data where stochasticity plays a crucial role [29]. These differentiable approximations replace discrete operations in the traditional algorithm with smooth functions, allowing gradient computation through backpropagation while maintaining the essential characteristics of stochastic simulation [29].

Optimal experimental design represents another frontier where gradient-based methods are making significant contributions. By leveraging Fisher Information matrices computed through sensitivity analysis, researchers can identify experimental conditions that maximize information gain for parameter estimation [25]. This approach has been shown to dramatically reduce the number of experiments required to accurately estimate parameters in complex biological networks, addressing the fundamental challenge of limited and costly experimental data in systems biology [25].

As biological models continue to increase in scale and complexity, the role of efficient gradient computation through adjoint methods and automatic differentiation will become increasingly important. Integration of these approaches with emerging computational frameworks for scientific machine learning promises to enhance both the efficiency and applicability of gradient-based optimization across all areas of systems biology and drug development.

Parameter estimation represents a fundamental and often computationally prohibitive step in developing predictive, mechanistic models of biological systems. This process involves calibrating the unknown parameters of dynamic models, described typically by sets of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs), to best fit experimental data. The problem is mathematically framed as a nonlinear programming problem with differential-algebraic constraints, where the goal is to find the parameter vector that minimizes the discrepancy between model simulation and experimental measurements [30] [31]. In practice, the objective function is often formulated as a weighted least-squares criterion, though maximum likelihood formulations are also common [30].

The landscapes of these optimization problems are characterized by high-dimensionality, non-convexity, and multimodality, often containing numerous local optima where traditional local search methods can stagnate [32] [33]. Furthermore, parameters in large-scale biological models are frequently correlated, leading to issues of structural and practical non-identifiability, where multiple parameter combinations can explain the experimental data equally well [33] [34]. These challenges have motivated the application of global metaheuristics—probabilistic algorithms designed to explore complex search spaces efficiently—with Scatter Search, Genetic Algorithms, and Evolutionary Computation emerging as particularly prominent strategies in systems biology.

Core Methodologies and Theoretical Foundations

Scatter Search (SS)

Scatter Search is a population-based metaheuristic that operates on a relatively small set of solutions known as the Reference Set (RefSet). Unlike genetic algorithms that emphasize randomization, Scatter Search is characterized by its systematic combination of solutions. The fundamental philosophy of Scatter Search is to create new solutions by combining existing ones in structured ways, followed by improvement methods to refine these combinations [30].

The enhanced Scatter Search (eSS) algorithm, which has demonstrated notable performance in biological applications, follows a structured methodology [30]:

- Diversification Generation: Creates an initial population of diverse solutions within the parameter bounds.

- RefSet Construction: Selects the best and most diverse solutions from the initial population to form the RefSet.

- Subset Generation: Generates subsets of solutions from the RefSet for combination.

- Solution Combination: Creates new solutions through linear or nonlinear combinations of the subset solutions.

- Improvement Method: Applies local search to enhance combined solutions.

- RefSet Update: Maintains diversity and quality in the RefSet by replacing similar or inferior solutions.

A key innovation in recent Scatter Search implementations is the self-adaptive cooperative enhanced Scatter Search (saCeSS), which incorporates parallelization strategies including asynchronous cooperation between processes and hybrid MPI+OpenMP parallelization to significantly accelerate convergence for large-scale problems [30].

Genetic Algorithms (GAs)

Genetic Algorithms are inspired by the process of natural selection and operate on a population of potential solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. The algorithm iteratively evolves the population toward better regions of the search space by favoring the "fittest" individuals [35] [36].

The standard GA workflow comprises:

- Initialization: A population of candidate solutions is randomly generated.

- Evaluation: Each candidate is evaluated using a fitness function (typically the objective function in parameter estimation).

- Selection: Individuals are selected for reproduction based on their fitness.

- Crossover: Pairs of selected individuals combine their features to produce offspring.

- Mutation: Random alterations are introduced to maintain diversity.

- Replacement: The new generation replaces the old one, often with elitism to preserve the best solutions.

In systems biology, GAs have been applied to parameter estimation since the 1990s, demonstrating particular utility for problems where gradient information is unavailable or unreliable [35]. Their population-based nature provides robustness against local optima, though they may require careful parameter tuning and significant computational resources [37] [36].

Evolutionary Strategies (ESs) and Evolutionary Computation

Evolutionary Strategies represent a specialized subclass of Evolutionary Computation (EC) distinguished by their emphasis on self-adaptation of strategy parameters and their design for continuous optimization problems [32]. While GAs were originally developed for discrete optimization, ESs were specifically designed for real-valued parameter spaces common in systems biology applications [32].

Key ES variants include:

- Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES): Adapts the covariance matrix of the mutation distribution to effectively navigate ill-conditioned landscapes.

- Stochastic Ranking Evolution Strategy (SRES): Incorporates constraint handling through a stochastic ranking procedure.

- (μ/μ, λ)-ES: A classical approach where μ parents produce λ offspring, with the best μ individuals selected for the next generation.

Evolutionary Computation more broadly encompasses both GAs and ESs, along with other population-based metaheuristics inspired by natural evolution. These methods have gained prominence in systems biology due to their robustness and ability to handle the complex, multimodal landscapes characteristic of biological models [32] [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Global Metaheuristic Characteristics

| Feature | Scatter Search | Genetic Algorithms | Evolutionary Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Inspiration | Systematic solution combination | Natural selection and genetics | Natural evolution and adaptation |

| Population Size | Small (typically 10-20) | Medium to Large (50-100+) | Medium (15-100) |