Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis for Large Biological Models: Advanced Methods for Efficient Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Quantification

This article provides a comprehensive guide to adjoint sensitivity analysis (ASA) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with large biological models.

Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis for Large Biological Models: Advanced Methods for Efficient Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Quantification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to adjoint sensitivity analysis (ASA) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with large biological models. We explore the foundational principles of ASA, a powerful mathematical framework that enables the efficient computation of gradients for systems governed by differential equations, with a cost independent of the number of parameters. The article details methodological implementations, including non-intrusive techniques and tools like PEtab.jl, and offers practical guidance on solver selection, troubleshooting, and optimization. Through validation frameworks, benchmarking studies, and real-world applications in areas like Alzheimer's disease research and systems biology, we demonstrate how ASA accelerates parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and optimal control, ultimately enhancing the reliability and predictive power of computational models in biomedical research.

Understanding Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis: Core Principles and Advantages for Biological Systems

The advancement of computational biology hinges on our ability to construct and parameterize accurate mathematical models of complex biological systems. Traditional approaches to model fitting and sensitivity analysis often encounter computational bottlenecks when applied to large-scale biological models with numerous parameters. This application note explores the mathematical foundation that connects the Lagrangian formalism, a cornerstone of theoretical physics, with modern adjoint sensitivity analysis methods, creating a powerful framework for addressing computational challenges in biological research. We demonstrate how this unified mathematical approach enables efficient parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification for large biological models, with direct applications in drug development and systems biology.

The synergy between these mathematical frameworks provides researchers with powerful tools for working with complex biological systems, from population dynamics to neuronal activity and tumor growth modeling. By establishing this mathematical connection and providing practical protocols, we aim to equip biological researchers with methodologies that significantly enhance computational efficiency in model parameterization and analysis.

Theoretical Foundation

Lagrangian Formalism in Biological Modeling

The Lagrangian formalism, with its foundation in the Principle of Stationary Action (PSA), has recently been adapted for biological applications after centuries of successful application in physics [1]. The action integral is defined as:

[ \mathcal{A}(x,ti,tf) = \int{ti}^{t_f} L[\dot{x}(t), x(t), t] dt ]

where (L[\dot{x}(t), x(t), t]) represents the Lagrangian function. The requirement that the action be stationary ((\delta \mathcal{A} = 0)) leads to the Euler-Lagrange equation:

[ \left[\frac{d}{dt}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \dot{x}}\right) - \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\right] L[\dot{x}(t), x(t), t] = 0 ]

which determines the system's evolution [1]. In biological contexts, three families of Lagrangians are particularly relevant:

Table 1: Families of Lagrangians in Biological Modeling

| Lagrangian Type | Mathematical Form | Biological Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Lagrangians (SLs) | (Ls[\dot{x}(t), x(t)] = E{kin}(\dot{x}) - E_{pot}(x)) | Classic population dynamics | Recognizable kinetic and potential energy-like terms |

| Non-standard Lagrangians (NSLs) | Cannot be separated into kinetic/potential terms | Complex biological systems | Originally termed 'non-natural' by Arnold |

| Null Lagrangians (NLs) | Defined as total derivative of gauge functions | Mathematical underpinnings | Identically satisfy Euler-Lagrange equation |

The application of Lagrangian formalism to biology spans several decades, with research demonstrating its utility for population dynamics models and other biological systems [1] [2] [3]. Recent work has extended these approaches to neuroscience, where modifications to neuronal state equations enable Lagrangian formulations through the use of complex variables and Hermitian connectivity matrices [4].

Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis Methodology

Adjoint sensitivity analysis provides a computationally efficient framework for calculating how changes in system parameters affect outputs or performance metrics, particularly for systems governed by differential equations [5]. The mathematical foundation begins with a system of governing equations in operator form:

[ \mathcal{F}(u, p) = 0 ]

where (u) denotes the state vector and (p) represents system parameters. The quantity of interest (J(u, p)) is typically a functional of the solution [5].

The adjoint method constructs a Lagrangian:

[ \mathcal{L}(u, \lambda, p) = J(u, p) - \lambda^T \mathcal{F}(u, p) ]

introducing Lagrange multipliers (\lambda). Through stationarity conditions, one obtains adjoint equations for (\lambda), typically integrated backward in time for unsteady systems [5]. The remarkable efficiency of this approach stems from its ability to compute gradients of (J) with respect to all parameters after just a single adjoint solve, using inner products involving (\lambda), (u), and derivatives of (\mathcal{F}) and (J) with respect to (p) [5].

For biological applications, particularly those involving steady-state measurements, recent advancements have introduced specialized adjoint methods that reformulate backward integration as solving systems of linear algebraic equations, significantly accelerating computations [6].

Mathematical Connections and Unifying Principles

The fundamental connection between Lagrangian formalism and adjoint sensitivity analysis lies in their shared variational foundation. Both approaches leverage calculus of variations and optimization principles to solve challenging problems in biological modeling:

Variational Framework: Both methods employ constrained optimization through Lagrangian multipliers, extending beyond their original physical interpretations to biological applications.

Computational Efficiency: The adjoint method's efficiency ((O(n+p)) complexity versus (O(np)) for forward methods) mirrors the parsimony offered by Lagrangian formulations in physics [7] [5].

Biological Adaptations: Recent research has established modifications necessary for applying these mathematical frameworks to biological systems, such as using complex variables in neuronal state equations [4] and handling steady-state constraints in parameter estimation [6].

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Lagrangian Formulation for Biological Systems

Objective: Derive a Lagrangian formulation for a biological system described by ordinary differential equations.

Table 2: Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Jacobian Matrix | Linearization of system dynamics | Local stability analysis |

| Jacobi Last Multiplier | Finding Lagrangians for systems of first-order ODEs | Population dynamics models |

| Hermitian Connectivity Matrix | Ensuring real Lagrangian for complex systems | Neural field models |

| Euler-Lagrange Equation | Deriving equations of motion from Lagrangians | All biological applications |

Procedure:

System Identification: Begin with a system of first-order ordinary differential equations representing the biological dynamics: [ \dot{z}i = fi(zj, \betak, t) ] where (zi) are state variables, (\betak) are parameters, and (t) is time.

Approach Selection: Choose an appropriate method based on system characteristics:

- For systems of two first-order equations, apply the Jacobi Last Multiplier method to obtain linear Lagrangians [3].

- For single second-order equations derived from biological models, employ standard variational approaches.

Lagrangian Construction:

- For non-oscillatory systems, attempt construction using real variables, noting potential limitations in solution uniqueness [4].

- For oscillatory behavior, utilize complex variables with Hermitian connectivity matrices: [ L = \frac{i}{2} \sumj (zj^* \dot{z}j - zj \dot{z}j^*) - \sum{j,k} (zj^* A{jk} zk + zj^* C{jk} vk + vj C{jk} zk) - \sumj \omegaj^{(z)} (zj + zj^*) ] where (A) and (C) are Hermitian matrices, and (vj) are external inputs [4].

Validation: Verify the Lagrangian by recovering original equations through the Euler-Lagrange equation and comparing simulations with experimental data.

Protocol 2: Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis for Parameter Estimation

Objective: Efficiently estimate parameters in large biological models using adjoint sensitivity analysis.

Materials and Tools:

- ODE/PDE model of biological system

- Experimental data (time-course or steady-state)

- Numerical solver with adjoint capabilities

- Optimization algorithm

Table 3: Adjoint Method Variants for Biological Applications

| Method Type | Computational Approach | Advantages | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete Adjoint | Differentiates numerical scheme residuals | Higher accuracy for nonlinear systems | Models with strong nonlinearities |

| Continuous Adjoint | Differentiates governing equations before discretization | Analytical clarity | Smooth physical systems |

| Steady-State Adjoint | Reformulates backward integration as linear systems | Speedup for equilibrium systems | Models with steady-state data |

| Adjoint Shadowing | Employs shadowing trajectories for chaotic systems | Handles exponential divergence | Ergodic chaotic systems |

Procedure:

Problem Formulation:

- Define the forward model: (\dot{x} = f(x(t), \theta, u)), where (x) represents state variables, (\theta) are unknown parameters, and (u) are inputs [6].

- Specify the objective function (loss function) measuring discrepancy between model output and experimental data.

Adjoint Method Selection: Choose an appropriate adjoint variant based on system characteristics (refer to Table 3).

Gradient Computation:

- Solve the forward system to compute state trajectories.

- Solve the adjoint system backward in time: [ \frac{d\lambda}{dt} = - \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \right)^T \lambda + \frac{\partial J}{\partial x} ] where (\lambda) are adjoint variables [7].

- For steady-state problems, solve the linear system: [ \left( I - \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \right)^T \lambda = \frac{\partial J}{\partial x} ] avoiding backward integration [6].

Parameter Update: Use computed gradients in gradient-based optimization to minimize the objective function.

Iteration: Repeat steps 3-4 until convergence criteria are met.

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Neuronal State Equations and Lagrangian Compatibility

Research has demonstrated that conventional neuronal state equations in computational neuroscience are incompatible with Lagrangian formulations. Through Bayesian model inversion, studies have shown that modified state equations using complex variables and Hermitian connectivity matrices provide higher model evidence for neuroimaging data including EEG, fNIRS, and ECoG [4].

Experimental Workflow:

- Generate synthetic data using both original and modified neuronal state equations.

- Perform Bayesian model inversion to compute variational free energy.

- Compare model evidence across different formulations.

- Validate with empirical neuroimaging data.

Results demonstrate that the modified complex, oscillatory model provides more parsimonious explanations for empirical timeseries while enabling Lagrangian compatibility [4].

Tumor Growth Modeling and Parameter Estimation

The adjoint method has been successfully applied to parameter estimation in avascular tumor growth models, which consist of coupled PDE systems with free boundaries [8].

Key Steps:

- Formulate tumor growth as a PDE-constrained optimization problem.

- Define appropriate functional to compare numerical solutions with experimental data.

- Implement adjoint method for functional minimization.

- Estimate unknown parameters governing nutrient-driven growth.

This approach enables fitting model parameters to real data obtained via in vitro experiments and medical imaging [8].

Performance Comparison of Sensitivity Methods

Recent comparative studies evaluate different differential sensitivity methods for biological models:

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Sensitivity Methods

| Method | Computational Speed | Implementation Complexity | Accuracy | Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Mode Automatic Differentiation | Fastest | Moderate | High | Limited |

| Complex Perturbation | Moderate | Simplest | High | Broad |

| Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis | Moderate for single outputs | Most complex | High | Moderate |

Studies find that forward mode automatic differentiation has the quickest computational time, while complex perturbation methods are simplest to implement and most generalizable [7]. However, adjoint methods provide superior scalability for models with many parameters when sensitivity with respect to few outputs is needed.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Neural Integral Equations

Recent advances extend adjoint sensitivity analysis to Neural Integral Equations (NIEs), which model global spatiotemporal relations and offer stability advantages over ODE/PDE solvers [9]. The First- and Second-Order Features Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis Methodology for Fredholm-Type NIEs (1st/2nd-FASAM-NIE-Fredholm) enables efficient computation of response sensitivities with respect to optimized parameters, requiring only a single "large-scale" computation regardless of the number of weights/parameters in the NIE network [9].

Chaotic and Hybrid Biological Systems

For biological systems exhibiting chaotic dynamics, conventional adjoint sensitivity analysis fails due to exponential trajectory divergence. Emerging approaches employ:

- Least Squares Shadowing (LSS): Solves for bounded "shadowing" adjoint trajectories

- Non-Intrusive Least Squares Adjoint Shadowing (NILSAS): Handles sensitivity computation for ergodic chaotic systems

- Density Adjoint Methods: Differentiate invariant density on attractors rather than individual trajectories [5]

For hybrid systems with discrete-continuous dynamics, adjoint methods incorporate jump sensitivity matrices that relate adjoint variables before and after discrete events [5].

Multi-Scale Biological Modeling

The integration of adjoint methods with multi-scale modeling frameworks enables efficient parameter estimation across biological scales, from molecular interactions to population dynamics. Future directions include coupling adjoint-based gradient computation with machine learning approaches for high-dimensional biological systems.

Parameter estimation is a cornerstone of building accurate mathematical models of complex biological systems, such as intracellular signaling pathways, metabolic networks, and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models. These models are typically described by systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) where many parameters, like reaction rate constants, are unknown and must be inferred from experimental data [6] [10]. The process involves finding the parameter values that minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental observations. For large-scale models with thousands of parameters, gradient-based optimization has proven highly effective, but computing these gradients through conventional methods like finite differences becomes computationally prohibitive [6].

Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis (ASA) provides a computationally efficient framework for calculating the gradients needed for parameter estimation. By solving an additional adjoint system backward in time, ASA enables the computation of the gradient of an objective function with respect to all parameters at a cost that is effectively independent of the number of parameters [5]. This is in stark contrast to forward sensitivity analysis, where the computational cost scales linearly with the number of parameters, making it infeasible for high-dimensional problems common in systems biology and drug development [6].

Quantitative Efficiency Analysis

The computational advantage of adjoint methods becomes critically important as model complexity increases. The table below compares the key characteristics of different sensitivity analysis methods, highlighting why adjoint methods are preferred for large-scale biological models.

Table 1: Comparison of Sensitivity Analysis Methods for Biological Models

| Method | Computational Scaling | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Best-Suited Model Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finite Differences | (O(N_{\text{params}})) | Simple to implement | Numerically unreliable; requires many function evaluations [6] | Small (tens of parameters) |

| Forward Sensitivity | (O(N{\text{states}} \times N{\text{params}})) | Accurate and robust | Cost explodes with parameter count [6] | Medium (hundreds of parameters) |

| Adjoint Sensitivity | (O(1)) with respect to (N_{\text{params}}) [5] | Efficient for high-dimensional parameter spaces | Requires solving a backward problem; more complex implementation [6] [5] | Large (thousands of parameters) |

The efficiency of adjoint methods is not merely theoretical. In real-world applications, such as the parameterization of large-scale dynamical models based on steady-state measurements, the adjoint approach has demonstrated a speedup of total simulation time by a factor of up to 4.4 compared to established methods [6]. This substantial improvement is particularly valuable for large-scale screening and omics data integration, where computational efficiency is critical.

For models involving steady-state constraints—common when working with proteomics or metabolomics data—a novel adjoint method reformulates the backward integration problem into a system of linear algebraic equations. This avoids numerically costly backward integration and provides further computational savings [6].

Protocol for Adjoint-Based Parameter Estimation in Biological Systems

This protocol details the application of adjoint sensitivity analysis for estimating parameters in a biological model, such as a signaling pathway or metabolic network.

Phase 1: Problem Formulation and Model Definition

Define the Biological System Dynamics: Formulate the system as a set of ODEs: ( \frac{dx}{dt} = f(x(t), p, u), \quad x(t0) = x0(p, u) ) where (x) is the vector of state variables (e.g., protein or metabolite concentrations), (p) is the vector of unknown parameters (e.g., kinetic rates), and (u) represents constant inputs (e.g., drug doses or external stimuli) [6].

Specify the Observable Model: Define the model outputs, which correspond to measurable quantities: ( y(t, p, u) = h(x(t, p, u), p, u) ) This function (h) maps states to observables (e.g., fluorescence readings or Western blot intensities) [6].

Establish the Objective Function: Formulate a least-squares objective function quantifying the mismatch between model and data: ( L(p) = \sum{i,j} \frac{(y{ij} - \bar{y}{ij})^2}{\sigma{ij}^2} ) where (\bar{y}{ij}) is the measured data point (j) for observable (i), (y{ij}) is the corresponding model prediction, and (\sigma_{ij}^2) is the noise variance [6] [10].

Phase 2: Adjoint Sensitivity Computation

Forward Solve: Numerically integrate the system ODEs (1) forward in time to compute the state trajectory (x(t)) for the current parameter estimate (p).

Adjoint Solve: Solve the adjoint system backward in time. The adjoint equation is typically of the form: ( \frac{d\lambda}{dt} = -\left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \right)^T \lambda + \left( \frac{\partial h}{\partial x} \right)^T W(y - \bar{y}), \quad \lambda(t_f) = 0 ) where (\lambda) is the adjoint state vector and (W) is a weighting matrix from the objective function [5] [10].

Gradient Assembly: Compute the gradient of the objective function with respect to all parameters using the inner product: ( \frac{dL}{dp} = \int{t0}^{t_f} \lambda^T \frac{\partial f}{\partial p} \, dt + \frac{\partial L}{\partial p} ) This step integrates information from both the forward and adjoint solutions [5].

Phase 3: Parameter Optimization and Validation

Gradient-Based Optimization: Use the computed gradient (\frac{dL}{dp}) in a gradient-based optimization algorithm (e.g., L-BFGS or conjugate gradient) to update the parameter set (p) and minimize the objective function (L(p)).

Iterate to Convergence: Repeat Phases 1-3 until the optimization converges to a local minimum, indicated by a negligible gradient norm or minimal change in the objective function.

Validate the Fitted Model: Test the calibrated model on a validation dataset not used during the fitting process to assess its predictive power and guard against overfitting.

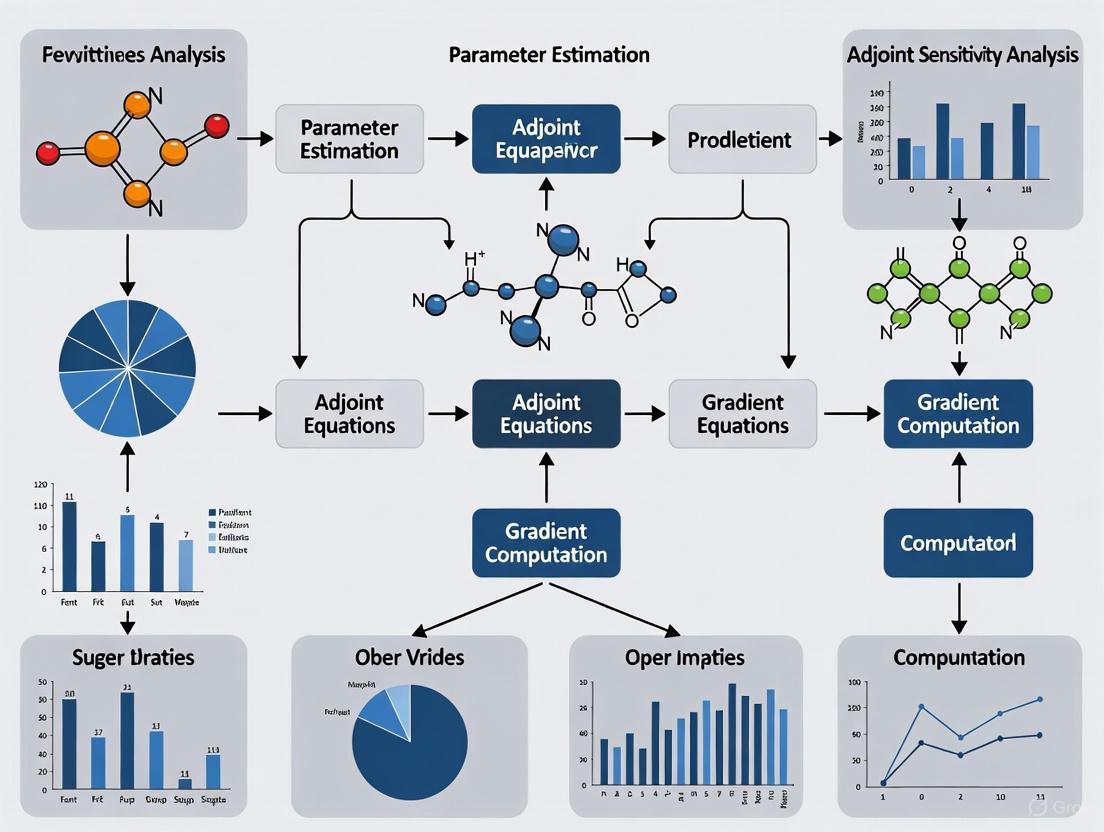

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and data dependencies of the adjoint-based parameter estimation protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Adjoint-Based Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| AMICI | A high-performance simulation and sensitivity analysis tool [6]. | Recommended for efficient forward/adjoint solves of ODE models; features Python and MATLAB interfaces. |

| PEtab | A standardized format for specifying parameter estimation problems [6]. | Use to define model, data, and conditions in a reproducible, tool-agnostic manner. |

| SUNDIALS | A suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers. | Provides robust numerical integrators (e.g., CVODES) suitable for stiff biological systems. |

| Fides | A Python implementation of a trust-region optimization algorithm. | Ideal for minimizing the objective function using adjoint-computed gradients. |

| FEniCS/dolfin-adjoint | A platform for solving PDEs with automated adjoint derivation. | Use for spatial-temporal models (e.g., tissue-scale PK/PD) beyond ODE systems. |

| adjointODE | A simplified implementation for educational use [10]. | A practical starting point for understanding and prototyping adjoint methods. |

Application Note: Signaling Pathway Model Calibration

Background: A research team aims to calibrate a mechanistic ODE model of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, a key target in oncology drug development. The model contains 85 dynamic species and 120 unknown kinetic parameters. The available data consists of time-course measurements of phosphorylated protein levels under 5 different drug perturbation conditions.

Challenge: Using finite differences for gradient calculation would require at least 121 forward simulations per optimization step, which is computationally infeasible. Forward sensitivity analysis would involve solving a system of ( (85 + 1) \times 120 = 10,320 ) ODEs.

Adjoint Solution: The team implements the protocol in Section 3 using the AMICI tool. Each optimization iteration requires only:

- 1 forward solution of 85 ODEs.

- 1 backward solution of 85 adjoint ODEs.

- Gradient assembly via numerical integration.

Outcome: The adjoint approach reduces the computation time per gradient evaluation by a factor of approximately 40 compared to forward sensitivity analysis, making the parameter estimation problem tractable. The calibrated model successfully predicts the efficacy of a novel drug combination, which is subsequently validated experimentally.

Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis provides an unparalleled computational advantage for parameter estimation in high-dimensional biological models. Its ability to compute gradients at a cost independent of the number of parameters enables researchers to tackle complex inference problems in systems biology and drug development that were previously infeasible. By following the detailed protocols and leveraging the tools outlined in this document, scientists can efficiently calibrate large-scale models to omics and pharmacological data, accelerating the discovery of novel biological insights and therapeutic strategies.

Parameter estimation is a foundational challenge in building quantitative dynamical models of biological systems, ranging from intracellular signaling pathways to tumor growth dynamics [10] [8]. These models are frequently described by systems of ordinary or partial differential equations where parameters are unknown and must be inferred from experimental data. The adjoint method provides a computationally efficient framework for calculating gradients needed for optimization, enabling parameter identification in systems with thousands of parameters [10] [11]. This document outlines detailed protocols for implementing the adjoint method workflow, specifically contextualized for large biological models encountered in pharmaceutical research and development.

Theoretical Foundation of the Adjoint Method

Problem Formulation

The parameter estimation problem for biological systems can be formally defined as follows. Consider a dynamical system whose state ( y ) (e.g., protein concentrations) evolves according to an equation of motion ( f ), which depends on parameters ( p ) (e.g., reaction rate constants) [10]:

[ \frac{d}{dt}y(t) = f(y(t), t, p), \quad y(t=0) = y_0. ]

The goal is to find parameters ( p ) that minimize a loss function ( L ), which quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data collected at time points ( \hat{t}0, \hat{t}1, \ldots, \hat{t}_N ) [10]:

[ L\left(y(\hat{t}0), \ldots, y(\hat{t}N)\right). ]

Core Workflow: Forward Solve and Backward Integration

The adjoint method computes the gradient of the loss function with respect to all parameters, ( \nabla_p L ), through a two-stage process that is efficient even for high-dimensional parameter spaces. The fundamental principle involves solving the original system forward in time, followed by solving an "adjoint system" backward in time to compute the required sensitivities [10] [11].

- Forward Solve: The original system of differential equations is numerically integrated from the initial time ( t=0 ) to the final time ( t=T ). The entire state trajectory ( y(t) ) must be stored or recorded for use in the subsequent backward integration.

- Backward Integration: The adjoint system is a linear differential equation in the adjoint variable ( \lambda(t) ), which is integrated backward from ( t=T ) to ( t=0 ). This system incorporates the stored state trajectory ( y(t) ) and encodes how the loss function changes with respect to the state. The final result of this backward integration provides the total gradient ( \nabla_p L ).

The key advantage of this method is its computational efficiency. The cost of computing the full gradient is effectively independent of the number of parameters, requiring only one forward and one backward solve, making it particularly suitable for large-scale biological models [10].

Protocol: Adjoint Workflow Implementation for ODE Models

Experimental Setup and Software Requirements

Research Reagent Solutions:

- PEtab.jl: A Julia-based tool for defining parameter estimation problems, linking models to experimental data, and computing likelihoods or posterior functions [11].

- SBMLImporter.jl: A package for importing Systems Biology Markup Language models into a format usable for sensitivity analysis [11].

- DifferentialEquations.jl Suite: A collection of high-performance ODE solvers in Julia. Stiff solvers (e.g., Rosenbrock methods) are recommended for molecular biological models due to their multi-scale nature [11].

- Automatic Differentiation (AD): A computational technique for evaluating derivatives of functions specified by computer programs. PEtab.jl leverages forward-mode AD for small models and reverse-mode AD for efficient computation in adjoint sensitivity analysis for large models [11].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Model and Data Specification:

- Define the biological model as a system of ODEs, ( \frac{dy}{dt} = f(y(t), t, p) ), with initial conditions ( y_0 ).

- Import the model into the computational environment (e.g., using

SBMLImporter.jlor by direct coding inCatalyst.jl) [11]. - Load experimental measurement data and define the loss function ( L ) (e.g., a least-squares or likelihood function) using

PEtab.jl[11].

Forward Solve Execution:

- Select an appropriate ODE solver from the

DifferentialEquations.jlsuite. For stiff systems common in biology (e.g., signaling pathways), use a stiff solver such asRosenbrock23()orRodas5()[11]. - Numerically integrate the system from ( t=0 ) to ( t=T ) using the current parameter estimate ( p ).

- Configure the solver to save the state trajectory ( y(t) ) at all required time points, including those specified in the loss function and any intermediate time steps needed for accurate backward integration.

- Select an appropriate ODE solver from the

Backward Integration and Gradient Calculation:

- The software infrastructure (e.g.,

PEtab.jlwithDifferentialEquations.jl) automatically formulates and solves the adjoint system. - The adjoint sensitivity algorithm performs the backward integration of the adjoint variable ( \lambda(t) ), utilizing the stored state trajectory ( y(t) ) from the forward solve [11].

- Upon completion of the backward integration, the algorithm returns the computed gradient ( \nabla_p L ).

- The software infrastructure (e.g.,

Parameter Update and Iteration:

- Use the gradient ( \nabla_p L ) within a gradient-based optimization algorithm (e.g., L-BFGS) to update the parameter set ( p ) in a direction that minimizes the loss.

- Iterate steps 2-4 until convergence is achieved (i.e., until the loss function is minimized and parameters stabilize).

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

Application Notes for Biological Systems

Benchmarking and Solver Selection

The performance of the adjoint method is highly dependent on the numerical ODE solver used for the forward and backward passes. Benchmarking across a range of biological models provides the following guidance [11]:

Table 1: ODE Solver Recommendations for Biological Models

| Model Category | Recommended Solver Type | Example Julia Solvers | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecular Models(3-16 species) | Stiff / Rosenbrock Methods | Rosenbrock23(), Rodas5() |

Julia's stiff solvers are fastest for this scale. |

| Medium-Sized Models(20-75 species) | Stiff / BDF Methods | QNDF(), CVODE_BDF() |

Julia and CVODES show comparable performance. |

| SIR / Phenomenological Models | Composite Solvers | AutoVern9(Rodas5()) |

Solvers that switch between stiff/non-stiff perform well. |

| Large Network Models(>75 species) | Stiff / BDF Methods | QNDF(), CVODE_BDF() |

No single best choice; benchmarking is required. |

Case Study: Tumor Growth Model Parameter Estimation

The adjoint method is directly applicable to biomedical problems such as estimating parameters in tumor growth models from imaging data [8].

- Model: A PDE model of avascular tumor growth, where growth is driven by nutrient concentration. The model domain (the tumor) changes over time, constituting a free-boundary problem [8].

- Objective: Estimate unknown model parameters (e.g., rates of cell proliferation and death) by fitting the model solution to experimental data from in vitro experiments or medical imaging.

- Protocol:

- The "forward solve" involves numerically simulating the tumor growth PDEs for a given parameter set.

- A cost functional is defined to quantify the mismatch between the simulated tumor size/shape and the experimental data.

- The "adjoint method" is employed to compute the gradient of this cost functional with respect to the model parameters efficiently.

- A gradient-based optimization algorithm uses this gradient to iteratively adjust the parameters to minimize the cost functional, thus calibrating the model to the data [8].

Diagram 2: Inverse Problem for Tumor Growth

Advanced Considerations: Hybrid Systems

Biological inference problems often have a hybrid, continuous-discrete nature, where a continuous-time model is calibrated against discrete-time measurements [12]. The adjoint method can be extended to such hybrid systems. The workflow involves specific rules for handling ideal Analog-to-Digital (AD) and Digital-to-Analog (DA) samplers at the interface of the continuous and discrete parts of the system, ensuring correct gradient propagation through discrete events [12].

Dynamic modelling serves as a powerful tool for elucidating the behavior of complex biological systems, from intracellular signalling networks to population-level cellular interactions [11]. Traditionally, many such models have been built using ordinary differential equations (ODEs), which provide a deterministic framework for modelling reaction kinetics. However, the inherent randomness in biological systems—arising from factors such as low molecular copy numbers, environmental heterogeneity, and stochastic biochemical interactions—often necessitates a transition to stochastic modelling frameworks for improved biological fidelity [13].

This application note explores the technical foundations, practical implementations, and protocol development for advancing from ODE to stochastic models within biological research. The content is framed within a broader thesis on adjoint sensitivity analysis for large biological models, providing researchers with actionable methodologies for enhancing model accuracy across multiple biological scales.

Theoretical Foundations: ODE and Stochastic Frameworks

Ordinary Differential Equation Models in Biology

ODE models represent biological systems through deterministic rate equations, typically expressed as: $$\frac{d}{dt}y{(t)}=f(y{(t)},t,p),\quad y{(t=0)}=y{0}$$ where $y$ represents the state variables (e.g., molecular concentrations), $t$ is time, and $p$ denotes the model parameters [10]. These models assume continuous and deterministic system evolution, providing a robust framework for systems with large molecular populations where stochastic effects average out.

Stochastic Differential Equation Models and Beyond

When randomness becomes non-negligible, stochastic models offer more biologically realistic representations. Key approaches include:

- Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs): Introduce noise terms to capture random fluctuations, often representing the limit of discrete stochastic processes with many degrees of freedom [14].

- Discrete-State Stochastic Methods: Model individual molecular interactions using frameworks such as the chemical master equation and Gillespie algorithms, which are particularly crucial for systems with low copy numbers [11] [13].

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine deterministic and stochastic elements to balance computational efficiency with biological accuracy [15].

The transition from ODE to stochastic frameworks becomes essential when modelling phenomena such as gene expression noise, cellular differentiation, and emergence of heterogeneous cell populations from genetically identical cells [16] [13].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Modelling Frameworks for Biological Systems

| Framework | Mathematical Foundation | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODE Models | Deterministic rate equations | Metabolic pathways, large-scale signalling networks [11] | Computational efficiency, well-established analysis tools | Fails to capture intrinsic noise in low-copy number systems |

| SDE Models | Stochastic differential equations | Near-deterministic systems with many degrees of freedom [14] | Captures environmental fluctuations, continuous framework | May not accurately represent discrete molecular events |

| Discrete Stochastic | Chemical master equation, Gillespie algorithm | Gene expression, small intracellular networks [11] [13] | Accurate for low copy numbers, discrete event representation | Computationally intensive for large systems |

Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis for Stochastic Biological Models

Adjoint sensitivity analysis provides a computationally efficient framework for parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and model selection in large-scale biological models. This approach enables researchers to compute gradients of objective functions with respect to model parameters through a single backward pass, regardless of parameter dimensionality [10].

For stochastic systems, adjoint methods can be integrated with both SDE frameworks and moment equations derived from discrete stochastic processes. The fundamental adjoint approach solves: $$\frac{d\lambda^T}{dt} = -\lambda^T\frac{\partial f}{\partial y} - \frac{\partial L}{\partial y}$$ where $\lambda$ represents the adjoint variables, $f$ defines the system dynamics, and $L$ is the loss function [10]. This methodology has been successfully applied to problems ranging from parameter estimation in cell signalling pathways to optimization of iPSC culture conditions [12] [16].

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Transitioning an ODE Model to a Stochastic Framework

Purpose: To convert an existing ODE-based biological model to a stochastic formulation while maintaining biological interpretability and computational tractability.

Materials:

- PEtab.jl for parameter estimation problem specification [11]

- SBMLImporter.jl for model import and conversion [11]

- Catalyst.jl for reaction network specification [11]

- DifferentialEquations.jl suite for numerical solution [11]

Procedure:

Model Specification and Import

- Export existing ODE model in SBML format using tools such as Copasi graphical interface [11]

- Import SBML model into Julia using SBMLImporter.jl, which converts the model to a Catalyst reaction network

- Verify model structure conservation through component-wise comparison of reaction networks

Stochastic Formulation Selection

- For chemical reaction systems with discrete molecular species, implement the jump process formulation using the Gillespie algorithm or related stochastic simulation algorithms

- For systems with continuous state variables subject to random fluctuations, implement the Langevin SDE formulation

- For multi-scale systems with both discrete and continuous elements, implement hybrid stochastic-deterministic methods

Parameter Estimation and Validation

- Define parameter estimation problem using PEtab.jl format, incorporating experimental measurements and appropriate noise models [11]

- Implement adjoint sensitivity analysis for efficient gradient computation, selecting forward-mode automatic differentiation for models with fewer than 100 parameters and reverse-mode for larger systems [11]

- Validate stochastic model against experimental data, focusing on both mean behavior and variance properties using metrics such as the Fano factor ($F=\sigma^2/\mu$) [13]

Troubleshooting:

- For numerical instability in SDE simulations, adjust solver tolerance or switch to implicit methods

- For excessive computational demands in discrete stochastic simulations, consider τ-leaping methods for approximate accelerated simulation

- For parameter non-identifiability, implement profile likelihood analysis or Bayesian inference with informative priors

Protocol 2: Multi-Scale Modelling of iPSC Aggregate Cultures

Purpose: To characterize spatial and metabolic heterogeneity in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) aggregate cultures using a Biological System-of-Systems (Bio-SoS) approach.

Materials:

- Stochastic metabolic network (SMN) module for intracellular metabolism [16]

- Population balance model (PBM) for aggregate size distribution [16]

- Reaction-diffusion model (RDM) for metabolite transport [16]

- Variance decomposition analysis framework for heterogeneity quantification [16]

Procedure:

Single-Cell Metabolic Module Development

- Construct stochastic metabolic reaction network from curated biochemical interactions

- Model molecular enzymatic reactions as Poisson processes to capture random enzyme-substrate collisions

- Calibrate expected metabolic reaction rates using 2D monolayer culture experimental data

Aggregate-Level Spatial Heterogeneity Modelling

- Implement population balance equations to describe iPSC proliferation, collision, and aggregation processes

- Apply coarse-grained approach dividing each aggregate into small spherical shells with homogeneous cellular metabolisms

- Solve reaction-diffusion equations to characterize nutrient and metabolite transport through aggregates

System Integration and Analysis

- Connect intracellular regulatory metabolic reaction network to aggregate environment through transport of metabolites across cellular membranes

- Implement variance decomposition analysis to quantify impact of critical factors (e.g., aggregate size) on metabolic heterogeneity

- Identify optimal aggregate size range across different bioreactor conditions to minimize unwanted cell death or heterogeneous cell populations

Troubleshooting:

- For numerical challenges in solving coupled reaction-diffusion equations, employ operator splitting methods

- For parameter uncertainty in metabolic networks, implement Bayesian inference with Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling

- For computational limitations in large-scale simulation, leverage high-performance computing capabilities of Julia programming environment [11]

Computational Tools and Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Stochastic Biological Modelling

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PEtab.jl | Standardized parameter estimation for biological models [11] | ODE and stochastic model calibration to experimental data |

| SBMLImporter.jl | Import SBML models into Julia environment [11] | Model exchange and conversion between frameworks |

| Catalyst.jl | Reaction network specification and analysis [11] | Unified representation of chemical reaction systems |

| DifferentialEquations.jl | Comprehensive suite of ODE, SDE, and jump problem solvers [11] | Numerical solution of dynamic models |

| PetriNuts Platform | Coloured Petri nets for multilevel modelling [15] | Spatial and structural organization in biological systems |

| Bio-SoS Framework | Integrated multi-scale modelling of cell populations [16] | iPSC culture optimization and heterogeneity analysis |

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Workflow for Advancing from ODE to Stochastic Biological Models

Figure 2: Multi-Scale Architecture for iPSC Aggregate Culture Modelling

Case Studies and Biological Applications

Gene Expression Regulation and Noise Control

Gene expression exhibits substantial stochasticity due to low copy numbers of DNA and transcription factors. A two-state stochastic model of gene regulation—with promoter switching between ON and OFF states—quantifies how different regulatory strategies affect expression noise [13].

- Self-repressing genes demonstrate sub-Poissonian noise characteristics (Fano factor F<1), providing inherent noise reduction mechanisms crucial for developmental precision

- Externally regulated genes exhibit super-Poissonian noise (F>1), which can be harnessed for phenotypic diversification under stress conditions

- Applications in developmental biology include understanding stripe formation in Drosophila melanogaster embryos, where external regulation generates precise spatio-temporal expression patterns despite inherent stochasticity [13]

Cell Population Dynamics and Contact Inhibition

Stochastic models quantify cell-cell interactions and proliferation control mechanisms, such as contact inhibition, where cells cease proliferation upon reaching confluence [13].

- Exclusion diameter concept quantifies contact inhibition as a spatial exclusion principle, with cancer cells exhibiting smaller exclusion diameters than normal cells

- Co-culture experiments with melanoma cells and keratinocytes demonstrate how reduced contact inhibition enables tumor cell cluster formation and eventual dominance

- Tissue organization disruption arises from molecular fluctuations affecting proliferation regulation, illustrating how noise contributes to carcinogenesis

Benchmarking and Solver Selection Guidelines

Comprehensive benchmarking of ODE solvers across 29 biological models provides practical guidance for solver selection [11]:

Table 3: ODE Solver Performance Across Biological Model Types

| Model Category | Recommended Solver Class | Performance Notes | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecular Models (<16 species) | Stiff solvers (Rosenbrock methods) | Julia solvers fastest; forward-mode AD optimal for gradients [11] | Signalling pathways, gene circuits |

| Medium Molecular Models (20-75 species) | Stiff solvers (BDF methods) | Comparable performance between Julia and CVODES [11] | Metabolic networks, larger signalling cascades |

| SIR-type Models | Composite solvers (automatic stiff/non-stiff switching) | Handle varying timescales effectively [11] | Epidemiology, population dynamics |

| Phenomenological Models | Problem-dependent selection | Mixed performance across solver types [11] | Cell differentiation, spiking dynamics |

The transition from ODE to stochastic modelling frameworks represents a crucial advancement in biological simulation fidelity, enabling researchers to capture intrinsic noise, spatial heterogeneity, and multi-scale interactions that underlie fundamental biological processes. The integration of adjoint sensitivity analysis with these frameworks provides a powerful methodology for parameter estimation and model identification even in high-dimensional settings.

Future research directions include: (1) enhanced machine learning integration for stochastic model reduction and emulation; (2) development of multi-scale adjoint methods spanning molecular to organism levels; and (3) experimental validation of noise predictions through single-cell measurement technologies. As biological modelling continues to advance, the strategic combination of ODE, stochastic, and hybrid approaches—coupled with efficient sensitivity analysis—will accelerate discovery across therapeutic development, synthetic biology, and fundamental biological research.

Implementing Adjoint Methods: Tools, Techniques, and Real-World Biological Applications

Adjoint sensitivity analysis is a powerful mathematical technique that has become indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with large biological models. For complex dynamical systems in the form of ordinary differential equations (ODEs)—commonly used to describe signaling pathways, metabolic processes, and gene regulatory networks—parameter estimation remains a significant challenge. Many parameters are unknown and must be inferred from experimental data, a process that gradient-based optimization greatly accelerates [6] [10]. Adjoint methods efficiently compute the gradient of an objective function (e.g., a measure of fit between model simulations and experimental data) with respect to model parameters, enabling parameter estimation for large-scale models with hundreds of thousands of parameters [10].

The two principal approaches for implementing adjoint sensitivity analysis are the continuous adjoint and discrete adjoint methods. The fundamental distinction lies in the order of operations: the continuous adjoint method first derives the adjoint equations analytically from the primal (forward) equations and then discretizes them for numerical solution. In contrast, the discrete adjoint method first discretizes the primal equations and then differentiates them to obtain the adjoint system [17]. This Application Note provides a detailed comparison of these approaches, framed within the context of large biological models, to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate method for their work.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Core Methodological Differences

The following table summarizes the fundamental distinctions between the continuous and discrete adjoint methodologies.

Table 1: Fundamental Methodological Differences Between Continuous and Discrete Adjoint Methods

| Feature | Continuous Adjoint | Discrete Adjoint |

|---|---|---|

| Derivation Sequence | First-differentiate-then-discretize [18] | First-discretize-then-differentiate [18] |

| Theoretical Basis | Derived from continuous primal PDEs/ODEs [18] | Derived from discretized primal equations [18] |

| Gradient Consistency | Generally inconsistent with discretized primal problem; accuracy depends on adjoint discretization scheme [18] | Naturally consistent with the discretized primal problem [18] |

| Physical Insight | Provides clear physical interpretation of adjoint equations and boundary conditions on a term-by-term basis [18] [17] | Lack of clear physical understanding of the adjoint equations [18] |

Performance and Practical Implementation

From a practical standpoint, the computational performance and implementation effort of each method are critical considerations for research teams.

Table 2: Performance and Practical Implementation Characteristics

| Characteristic | Continuous Adjoint | Discrete Adjoint |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Footprint | Low memory footprint [18] [17] | Generally high memory footprint [18] |

| Computational Cost | Lower CPU cost and faster solution times [17] | Higher computational cost due to memory overhead [17] |

| Implementation Basis | Re-uses existing primal numerical algorithms [17] | Often relies on automatic differentiation tools [17] |

| Convergence Requirements | Does not require a fully converged primal solution; can use field averaging [17] | Requires duality; sensitive to primal solution convergence [17] |

| Scalability | Scales more easily to complex problems without being heavily constrained by grid size [17] | Scalability can be hampered by high memory demands [18] |

The Think-Discrete Do-Continuous (TDDC) Adjoint Hybrid Approach

A recent innovation, the Think-Discrete Do-Continuous (TDDC) adjoint, aims to bridge the gap between the two classical methods. This approach starts by developing the adjoint partial differential equations, their boundary conditions, and sensitivity derivative expressions in continuous form. The key originality lies in the subsequent discretization, which is designed to match the expressions derived by hand-differentiated discrete adjoint [18]. The outcome is a method that combines the benefits of both approaches: the physical insight and low memory footprint of the continuous adjoint, together with the perfect gradient consistency of the discrete adjoint [18]. This hybrid method has been successfully verified on grids of different sizes, achieving an accuracy of six significant digits irrespective of the grid size [18].

Application Protocols for Biological Systems

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation for ODE Models of Signaling Pathways

Application Objective: Estimate unknown parameters for a system of ODEs modeling a cell signaling pathway using time-course and steady-state experimental data.

Background: The task of parameter estimation for continuous-time models with discrete-time measurements is a classic dual, continuous-discrete problem well-suited to adjoint methods [12]. This protocol is applicable to models of pathways such as those involved in disease mechanisms or drug responses.

Prerequisites: A defined ODE model (\dot{x} = f(x(t), \theta, u)), where (x) are state variables (e.g., protein concentrations), (\theta) are unknown parameters (e.g., kinetic rates), and (u) are inputs (e.g., drug doses). Experimental data must include measurements of observables (y(t) = h(x(t), \theta, u)) at specific time points [6].

Reagents and Solutions:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protocol 1

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| ODE Solver (BDF) | Solves stiff ODE systems common in biochemical reaction networks [6]. |

| Adjoint Solver (e.g., AMICI) | Performs efficient adjoint sensitivity analysis for gradient computation [6]. |

| Gradient-Based Optimizer | Minimizes the loss function (e.g., sum of squared errors) to find optimal parameters [6] [10]. |

| Steady-State Calculator | Computes steady states using Newton's method, required for pre-/post-equilibration [6]. |

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define a loss function (L) (e.g., a least-squares measure) that quantifies the mismatch between model predictions (y(tj, \theta)) and experimental data (\bar{y}{ij}) at time points (t_j) [6] [10].

- Solver Configuration: Configure the numerical ODE solver with appropriate tolerances (e.g.,

rtol,atol). For models requiring pre- or post-equilibration, configure the steady-state calculator [6]. - Gradient Computation: Use the selected adjoint method (Continuous, Discrete, or TDDC) to compute the gradient of the loss function (\nabla_{\theta}L) with respect to all unknown parameters (\theta).

- For problems with steady-state constraints, a novel adjoint method that reformulates the backward integration as a system of linear algebraic equations can be employed for greater efficiency [6].

- Parameter Update: Feed the computed gradient (\nabla_{\theta}L) to a gradient-based optimization algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt, BFGS) to update the parameter set (\theta) [10].

- Iteration: Iterate steps 2-4 until the loss function converges to a minimum and optimal parameters (\theta^*) are found.

- Validation: Validate the calibrated model using a held-out portion of the experimental data not used during the fitting process.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core iterative process of this protocol:

Protocol 2: Handling Steady-State Data with the Novel Adjoint Method

Application Objective: Efficiently compute gradients for objective functions when experimental data includes steady-state measurements, a common scenario in systems biology omics studies [6].

Background: Many biological studies provide data regarding the system's steady state, either as a starting condition (pre-equilibration) or as an endpoint (post-equilibration). Traditional adjoint methods simulate the model until approximate convergence to a steady state, which is computationally costly [6].

Prerequisites: A dynamical model and an objective function that depends on the system's state at steady state. This protocol is particularly valuable for large-scale models where computational efficiency is critical [6].

Procedure:

- Problem Identification: Determine if the simulation requires pre-equilibration (the system starts in a steady state), post-equilibration (the system reaches a steady state after dynamics), or both [6].

- Method Selection: For the steady-state phases, employ the novel adjoint method that exploits the steady-state constraint [6].

- System Reformulation: Instead of performing numerical backward integration for the steady-state phases, reformulate the problem to a system of linear algebraic equations [6].

- Gradient Computation: Solve the system of linear equations to compute the parts of the objective function gradient corresponding to the steady-state constraint. This avoids the need for numerical integration during these phases [6].

- Combination with Dynamic Data: Combine this gradient with those computed via standard adjoint methods (forward or backward integration) for any time-course data portions of the experiment [6].

This approach has been shown to achieve a substantial speedup in total simulation time by a factor of up to 4.4, with benefits increasing with model size [6].

The choice between continuous and discrete adjoint methods is not merely a theoretical preference but has direct implications for the success and efficiency of a research project. The following diagram outlines a decision framework to guide researchers in selecting the most suitable approach.

Summary of Key Selection Criteria:

- Choose the Continuous Adjoint method when physical insight into the adjoint problem is a priority, when computational resources (especially memory) are limited, when working with complex flows (e.g., external aerodynamics) or unsteady simulations like Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) where achieving a fully converged primal solution is difficult, and when development flexibility and code re-use are important [18] [17].

- Choose the Discrete Adjoint method when exact consistency of the computed gradients with the discretized primal problem is the paramount requirement, and when the associated high memory footprint and potential implementation complexity via automatic differentiation are acceptable [18].

- Consider the TDDC Adjoint hybrid method when aiming to combine the benefits of both worlds: the physical insight and low memory footprint of the continuous approach with the perfect gradient accuracy of the discrete approach [18].

In conclusion, both continuous and discrete adjoint methods represent powerful tools for parameter estimation and sensitivity analysis in large biological models. The continuous adjoint offers efficiency and flexibility, while the discrete adjoint provides mathematical consistency. The emerging TDDC adjoint and novel methods for steady-state problems demonstrate the ongoing innovation in this field, enabling researchers to tackle increasingly complex biological questions with greater computational efficacy.

The integration of PEtab.jl, SBMLImporter.jl, and SciMLSensitivity forms a powerful, high-performance computational environment tailored for dynamic modeling and parameter estimation in systems biology. This ecosystem leverages the Julia language's speed and the SciML (Scientific Machine Learning) suite's advanced differential equation solvers and sensitivity analysis capabilities. It is specifically designed to address the computational challenges inherent in working with large-scale biological models, such as those describing signaling pathways, metabolic networks, and gene regulatory systems. Central to its design is the efficient implementation of adjoint sensitivity analysis, a method that enables gradient-based parameter estimation for models with thousands of parameters, a task previously considered computationally intractable [19] [20] [21].

The core problem this ecosystem solves is the calibration of complex ordinary differential equation (ODE) models to experimental data. In systems biology and drug development, many model parameters—such as kinetic rates—are unknown and must be inferred from often noisy and heterogeneous measurements. This process, known as parameter estimation, involves solving a high-dimensional, non-convex optimization problem. The efficiency of this optimization critically depends on the accurate and fast computation of the objective function's gradient with respect to the parameters. The presented software suite provides a streamlined workflow from model import to optimized parameter determination, with a particular strength in handling models requiring steady-state constraints and multi-experiment data [20] [22].

Table 1: Core Components of the Julia SciML Ecosystem for Systems Biology

| Software Package | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| PEtab.jl | Formulates and solves parameter estimation problems | Supports PEtab standard format; Multi-start optimization; Handles pre-equilibration & events [20] [22]. |

| SBMLImporter.jl | Imports SBML models into Julia | Converts SBML to a Catalyst.jl ReactionSystem; Supports dynamic compartments, events, and rules [19]. |

| SciMLSensitivity | Computes sensitivities for ODE models | Provides forward & adjoint sensitivity analysis algorithms; Gradient computation for optimization [21]. |

Ecosystem Components and Their Interactions

SBMLImporter.jl: Model Import and Preprocessing

SBMLImporter.jl serves as the entry point for models defined in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML), a widely used XML-based format for representing biochemical network models. Its primary function is to parse an SBML file and convert it into a Catalyst.jl ReactionSystem, which is a symbolic representation of a chemical reaction network within the Julia ecosystem. This conversion is a critical first step, as the ReactionSystem can be seamlessly used for stochastic simulations (via JumpProcesses.jl), chemical Langevin simulations (SDEProblem), or deterministic simulations (ODEProblem) [19].

A key advantage of SBMLImporter.jl is its extensive support for SBML features that are common in complex biological models. It handles dynamic compartments, events (discrete state changes triggered by conditions), algebraic rules, and piecewise expressions (if-else logic). This ensures that sophisticated model behavior is preserved during the import process. The package has been rigorously tested against the SBML test suite and a large collection of published models, guaranteeing reliability. For users, this means that a model developed in tools like COPASI, CellDesigner, or Virtual Cell can be directly imported into the high-performance Julia environment for parameter estimation without manual rewriting, saving considerable time and reducing the potential for errors [19].

PEtab.jl: Parameter Estimation Problem Management

PEtab.jl is the central package that orchestrates the parameter estimation process. It allows users to define a complete parameter estimation problem, which includes the ODE model (imported via SBMLImporter.jl or defined natively), experimental data, observation functions, and parameters to be estimated. It fully supports the PEtab standard, a format designed to standardize the definition of parameter estimation problems in systems biology, which facilitates reproducibility and model sharing [20] [22].

The power of PEtab.jl lies in its integration with the broader SciML ecosystem. It automatically generates functions for computing initial values, observation functions, and events based on the provided data. Furthermore, it leverages ModelingToolkit.jl for symbolic model pre-processing, which can generate efficient Jacobians and system representations, leading to significant performance gains during simulation. PEtab.jl provides a unified interface to various optimization packages (Optim.jl, Ipopt, Optimization.jl) and Bayesian inference samplers (Turing.jl, AdaptiveMCMC.jl), making it a versatile tool for both frequentist and Bayesian parameter estimation [20] [22].

SciMLSensitivity and Gradient Computation Methods

The SciMLSensitivity package provides the mathematical backbone for efficient gradient computation, which is the most computationally demanding part of gradient-based parameter estimation. It offers a suite of sensitivity analysis algorithms, with a particular emphasis on adjoint sensitivity analysis for large-scale models [21].

For a parameter estimation problem with n_x state variables and n_θ parameters, the computational cost of gradient methods scales differently. While finite differences and forward sensitivity analysis scale poorly with the number of parameters (O(n_θ)), adjoint sensitivity analysis scales independently of n_θ, making it the only feasible method for models with thousands of parameters. SciMLSensitivity implements these adjoint methods, which involve solving a backward-in-time ODE to compute the gradient of the objective function with respect to the parameters. This allows researchers to fit genome-scale models, a task demonstrated in studies of ErbB signaling networks [21].

Table 2: Gradient Computation Methods Supported in the Ecosystem

| Method | Principle | Use Case | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ForwardDiff | Forward-mode automatic differentiation | Small models (few parameters) | Scales with n_θ |

| Forward Sensitivity | Integrates state and sensitivity ODEs together | Medium models | Scales with n_x * n_θ |

| Adjoint Sensitivity | Solves a backward-in-time adjoint ODE | Large-scale models (many parameters) | Independent of n_θ [21] |

| Zygote | Reverse-mode automatic differentiation | Models compatible with automatic differentiation | Varies |

Diagram 1: Parameter estimation workflow showing package roles.

Protocols for Parameter Estimation with Adjoint Sensitivities

Protocol 1: Importing an SBML Model and Defining a PEtab Problem

This protocol details the steps to import a biochemical model and define a parameter estimation problem.

Materials:

- Software Environment: A Julia installation (v1.10 or newer) with the packages

PEtab,SBMLImporter,OrdinaryDiffEq, andSciMLSensitivityinstalled. - Model File: An SBML file (

model.xml) defining the biochemical reaction network. - Data and Configuration Files: A PEtab YAML file (

petab_problem.yaml) specifying the experimental data, observables, parameters to estimate, and simulation conditions [20] [22].

Procedure:

- Import the SBML Model: Use

SBMLImporterto parse the SBML file and convert it into aReactionSystem. ThePEtabModelconstructor automatically handles the SBML import, extracts the observation functions and parameters from the YAML file, and performs symbolic pre-processing of the model using ModelingToolkit [20].

- Create the PEtabODEProblem: This step compiles the problem, specifying the numerical methods for ODE solving and gradient computation.

The

ODESolverargument allows selection from all solvers inDifferentialEquations.jl. Thegradient_method=:Adjointdirective instructs the system to use adjoint methods fromSciMLSensitivityfor gradient calculations [22] [21].

Protocol 2: Computing Cost, Gradient, and Hessian

This protocol describes how to evaluate the objective function and its derivatives at a given parameter value, which is the core computation for optimization.

Procedure:

- Define Parameter Vector: Extract the nominal parameter values or use a user-defined vector.

Compute Objective Function (Cost): Calculate the negative log-likelihood between the model simulation and data.

Compute Gradient: Calculate the gradient of the objective function using the specified adjoint method. Pre-allocate the gradient vector for performance.

Internally, this step involves solving the original ODE system forward in time and then solving the adjoint ODE backward in time. For problems with steady-state constraints, the ecosystem can exploit a reformulation that solves a system of linear equations instead of performing backward integration, yielding a substantial speedup [6] [21].

Compute Hessian (Optional): Calculate an approximation of the Hessian matrix, useful for uncertainty analysis.

Protocol 3: Large-Scale Model Parameter Estimation

This protocol outlines the complete workflow for calibrating a model to data using multi-start optimization to mitigate the issue of local minima.

Procedure:

- Select an Optimizer: Choose an optimizer suitable for large-scale problems. For gradient-based optimization with adjoint sensitivities, a solver like Ipopt is effective.

Run Multi-Start Local Optimization: Run the optimizer from multiple starting points in the parameter space to find the global optimum.

This function performs Latin Hypercube sampling to generate 10 initial parameter guesses. The optimization for each start point uses the efficient adjoint-based gradients [22].

Analyze Results: The results object contains the best-fitting parameters, the optimal objective function value, and convergence information for each run. The parameter estimates with the lowest cost value represent the calibrated model.

Applications in Biological Research and Drug Discovery

Case Study: Signaling Pathway Analysis and Drug Target Identification

Sensitivity analysis, powered by the efficient gradient computation of this ecosystem, is a cornerstone for identifying potential drug targets in signaling pathways. By calculating how sensitive a key model output (e.g., the concentration of a pro-survival protein) is to changes in individual parameters (e.g., kinetic rate constants), researchers can rank parameters by their biological impact.

A study on the p53/Mdm2 regulatory module used sensitivity analysis to identify processes whose perturbation would most effectively elevate levels of nuclear phosphorylated p53, a goal in promoting cancer cell apoptosis. The analysis ranked parameters based on a sensitivity index and suggested that the system response would be most efficiently altered by targeting processes related to PIP3/AKT activation and Mdm2 synthesis. This provides a computational prioritization for which proteins or reactions in the pathway to target therapeutically [23].

Diagram 2: Simplified p53/Mdm2 pathway and sensitivity analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Computational Workflow |

|---|---|

| SBML Model File | A portable, standard format encoding the structure and mathematics of the biochemical network. |

| PEtab YAML File | Defines the parameter estimation problem: links the model to data, specifies observables and noise models. |

| ODE Solver (e.g., Rodas5P) | Numerically integrates the differential equations to simulate the model dynamics. |

| Adjoint Sensitivity Algorithm | The core mathematical method for efficiently computing gradients in models with many parameters. |

| Multi-Start Optimizer | A global optimization strategy that runs local optimizations from multiple starting points to find the best fit. |

Performance and Validation

The computational advantage of adjoint sensitivity analysis has been quantitatively demonstrated. A study on a kinetic model of ErbB signaling showed that parameter estimation using adjoint sensitivity analysis required only a fraction of the computation time of established methods like forward sensitivity analysis. For large-scale models, the speedup can be multiple orders of magnitude, making the analysis feasible on standard computers [21].

Furthermore, a recent advancement focuses on problems involving steady-state data. A novel adjoint method reformulates the backward integration problem for pre- and post-equilibration scenarios into a system of linear algebraic equations. This approach achieved a speedup of the total simulation time by a factor of up to 4.4 in real-world problems, highlighting the continuous performance improvements within the ecosystem's methodological foundation [6].

The integrated software ecosystem of PEtab.jl, SBMLImporter.jl, and SciMLSensitivity provides a state-of-the-art, scalable solution for parameter estimation in systems biology. By leveraging the Julia language's performance and specialized algorithms like adjoint sensitivity analysis, it successfully addresses the computational bottleneck of fitting large-scale and genome-scale models to data. The detailed protocols provided here empower researchers to import models, define complex estimation problems, and efficiently compute gradients and optimize parameters. This capability is directly applicable to critical tasks like identifying key nodes in signaling pathways for drug targeting, accelerating the translation of quantitative models into actionable biological insights and therapeutic strategies.

Adjoint sensitivity analysis provides a powerful computational framework for efficiently evaluating the influence of numerous parameters on model outputs, a challenge pervasive in computational biology and drug development. While adjoint methods can compute gradients for thousands of parameters with a cost independent of parameter count, most implementations are "intrusive," requiring extensive modification of simulation source code. This creates prohibitive development and maintenance burdens, especially for legacy scientific software. This application note examines MF6-ADJ—a non-intrusive adjoint sensitivity capability developed for MODFLOW 6 groundwater modeling—as a paradigm for implementing adjoint analysis in legacy biological systems. We detail its architectural principles, quantitative performance gains, and provide transferable protocols for enabling efficient sensitivity analysis in complex biological models without structural code modification.

Adjoint sensitivity analysis represents a mathematical breakthrough for problems involving numerous parameters, enabling computation of how small changes in system parameters affect specific outputs through dual variables and backward solves. The method computes gradients with a cost independent of parameter count by combining a single forward solve with a backward adjoint solve, offering computational savings of several orders of magnitude compared to traditional perturbation methods [5]. For biological models with large parameter spaces—from pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models to quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) simulations—adjoint analysis enables previously infeasible parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and optimization tasks.

The fundamental challenge in applying adjoint methods to established biological modeling platforms lies in their typical "intrusive" implementation requirement, necessitating deep modification of the forward model's source code to incorporate adjoint equations. This creates significant development, validation, and maintenance burdens, particularly for legacy codes where source modification may introduce instability or break existing functionality. MF6-ADJ addresses this challenge through a non-intrusive paradigm that leverages modern API-based architecture, providing a transferable model for biological simulation platforms.

MF6-ADJ Architectural Framework

Non-Intrusive Implementation Strategy

MF6-ADJ implements a "non-intrusive" adjoint sensitivity capability for the MODFLOW 6 groundwater flow process that leverages the MODFLOW Application Programming Interface (API) to interact with the forward solution without altering its core code [24] [25]. This approach extracts requisite solution components as the simulation advances, enabling adjoint formulation and solution while maintaining compatibility with standard MODFLOW 6 releases [26]. The implementation is Python-based, connecting directly to MODFLOW 6 through the MODFLOW API, which provides flexibility to control the time stepping process and access solution data during simulation execution [25] [27].

This architectural approach ensures three critical advantages for legacy system implementation:

- Version Independence: Compatibility with future MODFLOW 6 versions without requiring adjoint code modification

- Maintenance Efficiency: Elimination of intrusive code changes reduces development and validation overhead

- Computational Preservation: Retention of the original solver's performance and numerical behavior

Mathematical Foundation

The discrete forward model of MODFLOW 6 uses a generalized control-volume finite-difference (CVFD) approach where the flow between cells is computed as the product of hydraulic conductance and head difference [25]. The system of equations is assembled in matrix form as:

Akhk = bk

where Ak is the conductance matrix at time step k, hk is the head vector, and bk contains constant terms and previous time-step dependencies [25]. The adjoint method efficiently computes sensitivities of performance measures with respect to parameters by solving a backward system that leverages the same matrix structure, enabling computational efficiency regardless of parameter count.

System Architecture and Data Flow

The following diagram illustrates the non-intrusive architecture of MF6-ADJ and its interaction with the legacy simulation code:

Performance Characterization and Benchmarking

Experimental Protocol: Validation and Performance Assessment

Objective: To validate MF6-ADJ accuracy and quantify computational performance gains against traditional methods.

Materials:

- MF6-ADJ Python package (GitHub: INTERA-Inc/mf6adj) [27]

- MODFLOW 6 executable with API support

- Test models: Analytical solutions and complex groundwater systems

- Computing environment: Standard workstation with multicore processor

Methodology:

- Accuracy Validation:

- Compare MF6-ADJ sensitivity outputs against analytical solutions for simplified cases

- Perform finite-difference perturbation method comparisons for complex models

- Calculate relative error metrics across parameter space

Performance Benchmarking:

- Execute sensitivity analysis for models with varying discretization (103 to 106 nodes)

- Parameter sets ranging from 102 to 105 variables

- Measure wall-clock time for both perturbation and adjoint methods

- Compute speedup factors as Tperturbation/Tadjoint

Scalability Assessment:

- Execute strong scaling tests (fixed problem size, varying core counts)

- Execute weak scaling tests (problem size proportional to core counts)

- Record memory utilization patterns

Quantitative Performance Results

Table 1: MF6-ADJ Performance Benchmarks for Different Model Discretizations