A Practical Framework for Formulating Parameter Estimation Problems in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for formulating parameter estimation problems, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Practical Framework for Formulating Parameter Estimation Problems in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for formulating parameter estimation problems, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It guides readers from foundational principles—defining parameters, models, and data requirements—through the core formulation of the problem as an optimization task, detailing objective functions and constraints. The content further addresses advanced troubleshooting, optimization techniques for complex models like pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships, and concludes with robust methods for validating and comparing estimation results to ensure reliability for critical biomedical applications.

Core Concepts: Defining Parameters, Models, and Data for Scientific Inference

What is a Parameter? Distinguishing Between Model Parameters and Population Characteristics

In statistical and scientific research, a parameter is a fundamental concept referring to a numerical value that describes a characteristic of a population or a theoretical model. Unlike variables, which can be measured and can vary from one individual to another, parameters are typically fixed constants, though their true values are often unknown and must be estimated through inference from sample data [1] [2]. Parameters serve as the essential inputs for probability distribution functions and mathematical models, generating specific distribution curves or defining the behavior of dynamic systems [1] [3]. The precise understanding of what a parameter represents—whether a population characteristic or a model coefficient—is critical for formulating accurate parameter estimation problems in research, particularly in fields like drug development and systems biology.

This guide delineates the two primary contexts in which the term "parameter" is used: (1) population parameters, which are descriptive measures of an entire population, and (2) model parameters, which are constants within a mathematical model that define its structure and dynamics. While a population parameter is a characteristic of a real, finite (though potentially large) set of units, a model parameter is part of an abstract mathematical representation of a system, which could be based on first principles or semi-empirical relationships [3] [4]. The process of determining the values of these parameters, known as parameter estimation, constitutes a central inverse problem in scientific research.

Population Parameters

Definition and Key Characteristics

A population parameter is a numerical value that describes a specific characteristic of an entire population [2] [5]. A population, in statistics, refers to the complete set of subjects, items, or entities that share a common characteristic and are the focus of a study [5]. Examples include all inhabitants of a country, all students in a university, or all trees in a forest [5]. Population parameters are typically represented by Greek letters to distinguish them from sample statistics, which are denoted by Latin letters [6] [7].

Key features of population parameters include:

- They Represent Entire Populations: Parameters encapsulate the entire population, whether it comprises millions of individuals or just a handful [5].

- They Are Fixed Constants: A population parameter is a fixed value, unlike a sample statistic, which can vary from one sample to another [1] [5]. This value does not change unless the population itself changes [5].

- They Are Often Unknown: For most real-world populations, especially large ones, measuring every unit is infeasible, making the true parameter value unknown [1] [2]. Researchers must then rely on statistical inference from samples to estimate population parameters.

Common Types of Population Parameters

Population parameters are classified based on the type of data they describe and the aspect of the population they summarize [5].

Table 1: Common Types of Population Parameters

| Type | Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Location Parameters | Describe the central point or typical value in a population distribution. | Mean (μ), Median, Mode [2] [5] |

| Dispersion Parameters | Quantify the spread or variability of values around the center. | Variance (σ²), Standard Deviation (σ), Range [5] |

| Proportion Parameters | Represent the fraction of the population possessing a certain characteristic. | Proportion (P) [6] [5] |

| Shape Parameters | Describe the form of the population distribution. | Skewness, Kurtosis [5] |

Population Parameters vs. Sample Statistics

The distinction between a parameter and a statistic is fundamental to statistical inference. A sample statistic (or parameter estimate) is a numerical value describing a characteristic of a sample—a subset of the population—and is used to make inferences about the unknown population parameter [1] [6] [7]. For example, the average income for a sample drawn from the U.S. is a sample statistic, while the average income for the entire United States is a population parameter [6].

Table 2: Parameter vs. Statistic Comparison

| Aspect | Parameter | Statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Describes a population [6] [5] | Describes a sample [6] [5] |

| Scope | Entire population [5] | Subset of the population [5] |

| Calculation | Generally impractical, often unknown [5] | Directly calculated from sample data [5] |

| Variability | Fixed value [1] [5] | Variable, depends on the sample drawn [1] [5] |

| Notation (e.g., Mean) | μ (Greek letters) [6] [7] | x̄ (Latin letters) [6] [7] |

The relationship between a statistic and a parameter is encapsulated in the concept of a sampling distribution, which is the probability distribution of a given statistic (like the sample mean) obtained from a large number of samples drawn from the same population [1]. This distribution enables researchers to draw conclusions about the corresponding population parameter and quantify the uncertainty in their estimates [1].

Model Parameters

Definition and Role in Mathematical Modeling

In the context of mathematical modeling, a model parameter is a constant that defines the structure and dynamics of a system described by a set of equations [3]. These parameters are not merely descriptive statistics of a population but are integral components of a theoretical framework designed to represent the behavior of a physical, biological, or economic system. Model parameters often represent physiological quantities, physical constants, or system gains and time scales [3]. For instance, in a model predicting heart rate regulation, parameters might represent afferent baroreflex gain or sympathetic delay [3].

The process of parameter estimation involves solving the inverse problem: given a model structure and a set of observational data, predict the values of the model parameters that best explain the data [3]. This is a central challenge in many scientific disciplines, as models can become complex with many parameters, while available data are often sparse or noisy [3].

The Parameter Estimation Problem

Formally, a dynamic system model can often be described by a system of differential equations:

dx/dt = f(t, x; θ)

where t is time, x is the state vector, and θ is the parameter vector [3]. The model output y that corresponds to measurable data is given by:

y = g(t, x; θ) [3].

Given a set of observed data Y sampled at specific times, the goal is to find the parameter vector θ that minimizes the difference between the model output y and the observed data Y [3]. This is typically framed as an optimization problem, where an objective function (often a least squares error) is minimized.

A significant challenge in this process is parameter identifiability—determining whether it is possible to uniquely estimate a parameter's value given the model and the available data [3]. A parameter may be non-identifiable due to the model's structure or because the available data are insufficient to inform the parameter. This leads to the need for subset selection, the process of identifying which parameter subsets can be reliably estimated given the model and a specific dataset [3].

Formulating a Parameter Estimation Problem: A Methodological Framework

Foundational Steps

Formulating a robust parameter estimation problem is a critical step in data-driven research. The following workflow outlines the core process, integrating both population and model parameter contexts.

Diagram: Parameter Estimation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages in formulating and solving a parameter estimation problem for research.

Define the Population and Characteristic of Interest

The first step is to unambiguously define the target population—the entire set of units (people, objects, transactions) about which inference is desired [5] [7]. This involves specifying the content, units, extent, and time. For example, a population might be "all patients diagnosed with stage 2 hypertension in the United States during the calendar year 2024." The population parameter of interest (e.g., mean systolic blood pressure, proportion responding to a drug) must also be clearly defined [8].

Select or Formulate a Mathematical Model

Based on the underlying scientific principles, a mathematical model must be selected or developed. This model, often a system of differential or algebraic equations, represents the hypothesized mechanisms governing the system [3] [4]. The model should be complex enough to capture essential dynamics but simple enough to allow for parameter identification given the available data.

Identify Model Parameters for Estimation

Not all parameters in a complex model can be estimated from a given dataset. Methods for practical parameter identification are used to determine a subset of parameters that can be estimated reliably [3]. Three methods compared in recent research include:

- Structured analysis of the correlation matrix: Identifies highly correlated parameters to avoid estimating them simultaneously. This method can provide the "best" subset but is computationally intensive [3].

- Singular value decomposition followed by QR factorization: A numerical approach to select a subset of identifiable parameters. This method is computationally easier but may sometimes result in subsets that still contain correlated parameters [3].

- Subspace identification: Identifies the parameter subspace closest to the one spanned by eigenvectors of the model Hessian matrix [3].

Experimental and Sampling Design

Design Sampling Strategy or Experiment

For population parameters, this involves designing a sampling plan to collect data from a representative subset of the population. The key is to minimize sampling error (error due to observing a sample rather than the whole population) and non-sampling errors (e.g., measurement error) [5]. For model parameters, this involves designing experiments that will generate data informative for the parameters of interest, often requiring perturbation of the system to excite the relevant dynamics [3].

Collect Data

Data is collected according to the designed strategy. For sample surveys, this involves measuring the selected sample units. For experimental models, this involves measuring the system outputs (the y vector) in response to controlled inputs [3] [8]. The data collection process must be rigorously documented and controlled to ensure quality.

Estimation and Validation

Choose an Estimation Method

The appropriate estimation method depends on the model's nature (linear/nonlinear), the error structure, and the data available.

- For nonlinear models: Local methods (e.g., gradient-based) can be efficient but may converge to local minima. Global optimization methods (e.g., branch-and-bound frameworks) are designed to find the global solution of nonconvex problems but are computationally more demanding [4].

- Error-in-variables methods: Account for noise in both input and output measurements, leading to a more complex but often more realistic formulation [4].

- Bayesian methods: Incorporate prior knowledge about parameters and provide a posterior distribution rather than a single point estimate.

Solve the Inverse Problem

This is the computational core of the process, where the optimization algorithm is applied to find the parameter values that minimize the difference between the model output and the observed data [3] [4]. For dynamic systems with process and measurement noise, specialized algorithms that reparameterize the unknown noise covariances have been developed to overcome theoretical and practical difficulties [9].

Validate and Interpret Results

The estimated parameters must be validated for reliability and interpreted in the context of the research question. This involves:

- Uncertainty Quantification: Calculating confidence intervals or credible regions for the parameter estimates [1] [5].

- Model Validation: Testing the model's predictive performance with the estimated parameters on a new, unseen dataset.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Determining how changes in parameters affect the model output, which also informs the reliability of the estimates [3].

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Parameter Estimation

Successful parameter estimation, particularly in biological and drug development contexts, relies on a suite of methodological reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Parameter Estimation

| Category / Tool | Function in Parameter Estimation |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity & Identifiability Analysis | Determines which parameters significantly influence model outputs and can be uniquely estimated from available data [3]. |

| Global Optimization Algorithms (e.g., αBB) | Solves nonconvex optimization problems to find the global minimum of the objective function, avoiding local solutions [4]. |

| Structured Correlation Analysis | Identifies and eliminates correlated parameters to ensure a numerically well-posed estimation problem [3]. |

| Error-in-Variables Formulations | Accounts for measurement errors in both independent and dependent variables, leading to less biased parameter estimates [4]. |

| Sampling Design Frameworks | Plans data collection strategies to maximize the information content for the parameters of interest while minimizing cost [5]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | For Bayesian estimation, samples from the posterior distribution of parameters, providing full uncertainty characterization. |

Understanding the dual nature of parameters—as fixed population characteristics and as tuning elements within mathematical models—is foundational to scientific research. Formulating a parameter estimation problem requires a systematic approach that begins with a precise definition of the population or system of interest, proceeds through careful model selection and experimental design, and culminates in the application of robust computational methods to solve the inverse problem. The challenges of practical identifiability, correlation between parameters, and the potential for multiple local optima necessitate a sophisticated toolkit. By rigorously applying the methodologies outlined—from subset selection techniques like structured correlation analysis to global optimization frameworks—researchers and drug development professionals can reliably estimate parameters, thereby transforming models into powerful, patient-specific tools for prediction and insight.

Mathematical models serve as a critical backbone in scientific research and drug development, providing a quantitative framework to describe, predict, and optimize system behaviors. The progression from simple statistical models to complex mechanistic representations marks a significant evolution in how researchers approach problem-solving across diverse fields. In pharmaceutical development particularly, this modeling continuum enables more informed decision-making from early discovery through clinical stages and into post-market monitoring [10].

The formulation of accurate parameter estimation problems stands as a cornerstone of effective modeling, bridging the gap between theoretical constructs and experimental data. This technical guide explores the spectrum of mathematical modeling approaches, with particular emphasis on parameter estimation methodologies that ensure models remain both scientifically rigorous and practically useful within drug development pipelines. As models grow in complexity to encompass physiological detail and biological mechanisms, the challenges of parameter identifiability and estimation become increasingly pronounced, especially when working with limited experimental data [3] [11].

The Modeling Spectrum: From Descriptive to Mechanistic

Simple Regression and Statistical Models

The foundation of mathematical modeling begins with statistical approaches that describe relationships between variables without necessarily invoking biological mechanisms. Simple linear regression models, utilizing techniques such as ordinary least squares, establish quantitative relationships between independent and dependent variables [12]. These models provide valuable initial insights, particularly when the underlying system mechanisms are poorly understood.

In pharmacological contexts, Non-compartmental Analysis (NCA) represents a model-independent approach that estimates key drug exposure parameters directly from concentration-time data [10]. Similarly, Exposure-Response (ER) analysis quantifies relationships between drug exposure levels and their corresponding effectiveness or adverse effects, serving as a crucial bridge between pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [10].

Intermediate Complexity: Semi-Mechanistic Models

Semi-mechanistic models incorporate elements of biological understanding while maintaining empirical components where knowledge remains incomplete. Population Pharmacokinetic (PPK) models characterize drug concentration time courses in diverse patient populations, explaining variability through covariates such as age, weight, or renal function [10]. These models employ mixed-effects statistical approaches to distinguish between population-level trends and individual variations.

Semi-Mechanistic PK/PD models combine mechanistic elements describing drug disposition with empirical components capturing pharmacological effects [10]. This hybrid approach balances biological plausibility with practical estimability, often serving as a workhorse in clinical pharmacology applications.

Complex Mechanistic Models

At the most sophisticated end of the spectrum, mechanistic models attempt to capture the underlying biological processes governing system behavior. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models incorporate anatomical, physiological, and biochemical parameters to predict drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion across different tissues and organs [10] [13]. These models facilitate species translation and prediction of drug-drug interactions.

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models represent the most comprehensive approach, integrating systems biology with pharmacology to simulate drug effects across multiple biological scales [10]. QSP models capture complex network interactions, pathway dynamics, and feedback mechanisms, making them particularly valuable for exploring therapeutic interventions in complex diseases.

Table 1: Classification of Mathematical Models in Drug Development

| Model Category | Key Examples | Primary Applications | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Statistical | Linear Regression, Non-compartmental Analysis (NCA), Exposure-Response | Initial data exploration, descriptive analysis, preliminary trend identification | Limited, often aggregate data |

| Semi-Mechanistic | Population PK, Semi-mechanistic PK/PD, Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) | Clinical trial optimization, dose selection, covariate effect quantification | Rich individual-level data, sparse sampling designs |

| Complex Mechanistic | PBPK, QSP, Intact Protein PK/PD (iPK/PD) | First-in-human dose prediction, species translation, target validation, biomarker strategy | Extensive in vitro and in vivo data, system-specific parameters |

Parameter Estimation Fundamentals

The Parameter Estimation Problem

Parameter estimation constitutes the process of determining values for model parameters that best explain observed experimental data. Formally, this involves identifying parameter vector θ that minimizes the difference between model predictions y(t,θ) and experimental observations Y(t) [3]. The problem can be represented as finding θ that minimizes the objective function:

[ \min{\theta} \sum{i=1}^{N} [Y(ti) - y(ti,\theta)]^2 ]

where N represents the number of observations, Y(ti) denotes measured data at time ti, and y(ti,θ) represents model predictions at time ti given parameters θ [3].

Practical Identifiability Challenges

A fundamental challenge in parameter estimation lies in determining whether parameters can be uniquely identified from available data. Structural identifiability addresses whether parameters could theoretically be identified given perfect, noise-free data, while practical identifiability considers whether parameters can be reliably estimated from real, noisy, and limited datasets [3]. As model complexity increases, the risk of non-identifiability grows substantially, particularly when working with sparse data common in clinical and preclinical studies.

The heart of the estimation challenge emerges from the inverse problem nature of parameter estimation: deducing internal system parameters from external observations [3]. This problem frequently lacks unique solutions, especially when models contain numerous parameters or when data fails to adequately capture system dynamics across relevant timescales and conditions.

Methodologies for Parameter Estimation

Subset Selection Methods

Subset selection approaches systematically identify which parameters can be reliably estimated from available data while fixing remaining parameters at prior values. These methods rank parameters from most to least estimable, preventing overfitting by reducing the effective parameter space [3] [11]. Three prominent techniques include:

Structured Correlation Analysis: Examines parameter correlation matrices to identify highly correlated parameter groups that cannot be independently estimated [3]. This method provides comprehensive insights but can be computationally intensive.

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) with QR Factorization: Uses matrix decomposition techniques to identify parameter subsets that maximize independence and estimability [3]. This approach offers computational advantages while providing reasonable subset selections.

Hessian-based Subspace Identification: Analyzes the Hessian matrix (matrix of second-order partial derivatives) to identify parameter directions most informed by available data [3]. This method connects parameter estimability to model sensitivity.

Subset selection proves particularly valuable when working with complex mechanistic models containing more parameters than can be supported by available data [11]. The methodology provides explicit guidance on which parameters should be prioritized during estimation, effectively balancing model complexity with information content.

Bayesian Estimation Methods

Bayesian approaches treat parameters as random variables with probability distributions representing uncertainty. These methods combine prior knowledge (encoded in prior distributions) with experimental data (incorporated through likelihood functions) to generate posterior parameter distributions [11]. This framework naturally handles parameter uncertainty, especially valuable when data is limited.

Bayesian methods introduce regularization through prior distributions, preventing parameter estimates from straying into biologically implausible ranges unless strongly supported by data [11]. This approach proves particularly powerful when incorporating historical data or domain expertise, though it requires careful specification of prior distributions to avoid introducing bias.

Comparison of Estimation Approaches

Table 2: Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methodologies

| Characteristic | Subset Selection | Bayesian Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Identify and estimate only identifiable parameters | Estimate all parameters with uncertainty quantification |

| Prior Knowledge | Used to initialize fixed parameters | Formally encoded in prior distributions |

| Computational Demand | Moderate to high (multiple analyses required) | High (often requires MCMC sampling) |

| Output | Point estimates for subset parameters | Posterior distributions for all parameters |

| Strengths | Prevents overfitting, provides estimability assessment | Naturally handles uncertainty, incorporates prior knowledge |

| Weaknesses | May discard information about non-estimable parameters | Sensitive to prior misspecification, computationally intensive |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Estimation

Protocol for Subset Selection Implementation

Model Definition: Formulate the mathematical model structure, specifying state variables, parameters, and input-output relationships [3].

Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate sensitivity coefficients describing how model outputs change with parameter variations. Numerical approximations can be used for complex models: [ S{ij} = \frac{\partial yi}{\partial \thetaj} \approx \frac{y(ti,\thetaj+\Delta\thetaj) - y(ti,\thetaj)}{\Delta\theta_j} ]

Parameter Ranking: Apply subset selection methods (correlation analysis, SVD, or Hessian-based approaches) to rank parameters from most to least estimable [3].

Subset Determination: Select the parameter subset for estimation by identifying the point where additional parameters provide diminishing returns in model fit improvement.

Estimation and Validation: Estimate selected parameters using optimization algorithms, then validate model performance with test datasets [3].

Protocol for Bayesian Estimation Implementation

Prior Specification: Define prior distributions for all model parameters based on literature values, expert opinion, or preliminary experiments [11].

Likelihood Definition: Formulate the likelihood function describing the probability of observing experimental data given parameter values, typically assuming normally distributed errors.

Posterior Sampling: Implement Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to generate samples from the posterior parameter distribution [11].

Convergence Assessment: Monitor MCMC chains for convergence using diagnostic statistics (Gelman-Rubin statistic, trace plots, autocorrelation).

Posterior Analysis: Summarize posterior distributions through means, medians, credible intervals, and marginal distributions to inform decision-making.

Research Reagent Solutions for PK/PD Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PK/PD Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices | Provides sensitivity and specificity for drug measurement; essential for traditional PK studies [14] |

| Intact Protein Mass Spectrometry | Measurement of drug-target covalent conjugation (% target engagement) | Critical for covalent drugs where concentration-effect relationship is uncoupled; enables direct target engagement quantification [14] |

| Covalent Drug Libraries | Screening and optimization of irreversible inhibitors | Includes diverse electrophiles for target identification; requires careful selectivity assessment [14] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for mass spectrometry quantification | Improves assay precision and accuracy through isotope dilution methods [14] |

| Target Protein Preparations | In vitro assessment of drug-target interactions | Purified proteins for mechanism confirmation and binding affinity determination [14] |

| Biological Matrices | Preclinical and clinical sample analysis | Plasma, blood, tissue homogenates for protein binding and distribution studies [14] |

Visualization of Modeling Workflows

Model-Informed Drug Development Strategy

Parameter Estimation Decision Framework

Covalent Drug Development Workflow

The strategic application of mathematical models across the complexity spectrum provides powerful capabilities for advancing drug development and therapeutic optimization. From simple regression to complex mechanistic PK/PD models, each approach offers distinct advantages tailored to specific research questions and data availability. The critical bridge between model formulation and practical application lies in robust parameter estimation methodologies that respect both mathematical principles and biological realities.

Subset selection and Bayesian estimation approaches offer complementary pathways to address the fundamental challenge of parameter identifiability in limited data environments. Subset selection provides a conservative framework that explicitly acknowledges information limitations, while Bayesian methods fully leverage prior knowledge with formal uncertainty quantification. The choice between these methodologies depends on multiple factors, including data quality, prior knowledge reliability, computational resources, and model purpose.

As Model-Informed Drug Development continues to gain prominence in regulatory decision-making [10], the thoughtful integration of appropriate mathematical models with careful parameter estimation will remain essential for maximizing development efficiency and accelerating patient access to novel therapies. Future advances will likely incorporate emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning to enhance both model development and parameter estimation, particularly for complex biological systems where traditional methods face limitations.

The reliability of any parameter estimation problem in scientific research is fundamentally dependent on the triumvirate of data quality, data quantity, and data types. These three elements form the foundational pillars that determine whether mathematical models and statistical analyses can yield accurate, precise, and biologically or chemically meaningful parameter estimates. In model-informed drug development (MIDD) and chemical process engineering, the systematic approach to data collection has become increasingly critical for reducing costly late-stage failures and accelerating hypothesis testing [10] [15]. The framework for reliable estimation begins with recognizing that data must be fit-for-purpose—a concept emphasizing that data collection strategies must be closely aligned with the specific questions of interest and the context in which the resulting model will be used [10].

Parameter estimation represents the process of determining values for unknown parameters in mathematical models that best explain observed experimental data. The precision and accuracy of these estimates directly impact the predictive capability of models across diverse applications, from pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling in drug development to process optimization in chemical engineering [10] [15]. This technical guide examines the core requirements for experimental data to support reliable parameter estimation, addressing the interconnected dimensions of quality, quantity, and type that researchers must balance throughout experimental design and execution.

Data Quality Dimensions and Metrics

High-quality data serves as the bedrock of reliable parameter estimation. Data quality can be systematically evaluated through multiple dimensions, each representing a specific attribute that contributes to the overall fitness for use of the data in parameter estimation problems. The table below summarizes the six core dimensions of data quality most relevant to experimental research.

Table 1: Core Data Quality Dimensions for Experimental Research

| Dimension | Definition | Impact on Parameter Estimation | Example Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Degree to which data correctly represents the real-world values or events it depicts [16] [17] | Inaccurate data leads to biased parameter estimates and compromised model predictability | Percentage of values matching verified sources [16] |

| Completeness | Extent to which all required data is present and available [16] [18] | Missing data points can introduce uncertainty and reduce estimation precision | Number of empty values in critical fields [18] |

| Consistency | Uniformity of data across different datasets, systems, and time periods [16] [17] | Inconsistent data creates internal contradictions that undermine model identifiability | Percent of matched values across duplicate records [17] |

| Timeliness | Availability of data when needed and with appropriate recency [16] [17] | Outdated data may not represent current system behavior, leading to irrelevant parameters | Time between data collection and availability for analysis [17] |

| Uniqueness | Absence of duplicate or redundant records in datasets [16] [18] | Duplicate records can improperly weight certain observations, skewing parameter estimates | Percentage of duplicate records in a dataset [18] |

| Validity | Conformance of data to required formats, standards, and business rules [16] [17] | Invalid data formats disrupt analytical pipelines and can lead to processing errors | Number of values conforming to predefined syntax rules [17] |

Beyond these core dimensions, additional quality considerations include integrity—which ensures that relationships between data attributes are maintained as data transforms across systems—and freshness, which is particularly critical for time-sensitive processes [17]. For parameter estimation, the relationship between data quality dimensions and their practical measurement can be visualized as a systematic workflow.

The implementation of systematic data quality assessment requires both technical and procedural approaches. Technically, researchers should establish automated validation checks that monitor quality metrics continuously throughout data collection processes [18]. Procedurally, teams should maintain clear documentation of quality standards and assign accountability for data quality management [18]. The cost of poor data quality manifests in multiple dimensions, including wasted resources, unreliable analytics, and compromised decision-making—with one Gartner estimate suggesting poor data quality can result in additional spend of $15M in average annual costs for organizations [17].

Data Types and Their Analytical Implications

Understanding data types is fundamental to selecting appropriate estimation techniques and analytical approaches. Data can be fundamentally categorized as quantitative or categorical, with each category containing specific subtypes that determine permissible mathematical operations and statistical treatments.

Table 2: Data Types in Experimental Research

| Category | Type | Definition | Examples | Permissible Operations | Statistical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Continuous | Measurable quantities representing continuous values [19] [20] | Height, weight, temperature, concentration [19] | Addition, subtraction, multiplication, division | Regression, correlation, t-tests, ANOVA |

| Discrete | Countable numerical values representing distinct items [19] [20] | Number of patients, cell counts, molecules [19] | Counting, summation, subtraction | Poisson regression, chi-square tests | |

| Categorical | Nominal | Groupings without inherent order or ranking [19] [20] | Species, gender, brand, material type [19] | Equality testing, grouping | Mode, chi-square tests, logistic regression |

| Ordinal | Groupings with meaningful sequence or hierarchy [19] [20] | Severity stages, satisfaction ratings, performance levels [19] | Comparison, ranking | Median, percentile, non-parametric tests | |

| Binary | Special case of nominal with only two categories [20] | Success/failure, present/absent, yes/no [20] | Equality testing, grouping | Proportion tests, binomial tests |

The selection of variables for measurement should be guided by their role in the experimental framework. Independent variables (treatment variables) are those manipulated by researchers to affect outcomes, while dependent variables (response variables) represent the outcome measurements [20]. Control variables are held constant throughout experimentation to isolate the effect of independent variables, while confounding variables represent extraneous factors that may obscure the relationship between independent and dependent variables if not properly accounted for [20].

The relationship between these variable types in an experimental context can be visualized as follows:

In parameter estimation, the data type directly influences the choice of estimation algorithm and model structure. Continuous data typically supports regression-based approaches and ordinary least squares estimation, while categorical data often requires generalized linear models or maximum likelihood estimation with appropriate link functions [20]. The transformation of data types during analysis, such as converting continuous measurements to categorical groupings or deriving composite variables from multiple measurements, should be performed with careful consideration of the information loss and analytical implications [20].

Data Quantity and Experimental Design

Determining the appropriate quantity of data represents a critical balance between statistical rigor and practical constraints. Insufficient data leads to underpowered studies incapable of detecting biologically relevant effects, while excessive data collection wastes resources and may expose subjects to unnecessary risk [21] [22].

Fundamental Principles of Experimental Design

Robust experimental design rests on several key principles that maximize information content while controlling for variability:

- Replication: Repeated observations under identical conditions increase reliability and quantify variability [21]. The number of replicates directly impacts the precision of parameter estimates and should be determined through power analysis rather than historical precedent [22].

- Randomization: Random assignment of treatments to experimental units ensures that unspecified disturbances are spread evenly among treatment groups, preventing confounding [21].

- Blocking: Grouping experimental units into homogeneous blocks allows researchers to remove known sources of variability, thereby increasing the precision of parameter estimates [21].

- Multifactorial Design: Simultaneously varying multiple factors rather than using one-factor-at-a-time approaches enables efficient exploration of factor interactions and more comprehensive parameter estimation [21].

Sample Size Determination through Power Analysis

Statistical power analysis provides a formal framework for determining sample sizes needed to detect effects of interest while controlling error rates. The power (1-β) of a statistical test represents the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis—that is, detecting an effect when one truly exists [21] [22]. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between key concepts in hypothesis testing and their interconnections:

The parameters involved in sample size calculation for t-tests include:

- Effect Size: The minimum difference between groups that would be considered biologically relevant [22]. For standardized effect sizes, Cohen's d of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 typically represent small, medium, and large effects in laboratory animal studies [22].

- Variability: The standard deviation of measurements, typically estimated from pilot studies, previous literature, or systematic reviews [22].

- Significance Level (α): The probability of obtaining a false positive, conventionally set at 0.05 [22].

- Power (1-β): The target probability of detecting a true effect, typically set between 80-95% [22].

For model-based design of experiments (MBDoE) in process engineering and drug development, additional considerations include parameter identifiability and model structure [15]. MBDoE techniques explicitly account for the mathematical model form when designing experiments to maximize parameter precision while minimizing experimental effort [15].

Group Allocation and Balanced Designs

In comparative experiments, proper allocation of experimental units to treatment and control groups is essential. Every experiment should include at least one control or comparator group, which may be negative controls (placebo or sham treatment) or positive controls to verify detection capability [22]. Balanced designs with equal group sizes typically maximize sensitivity for most experimental configurations, though unequal allocation may be advantageous when multiple treatment groups are compared to a common control [22].

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) Protocol

MIDD employs quantitative modeling and simulation to enhance decision-making throughout drug development [10]. The protocol involves:

- Question Formulation: Define specific questions of interest and context of use for the modeling exercise [10].

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate modeling methodologies based on development stage and research questions [10].

- Experimental Design: Identify data requirements and design experiments to inform model parameters [10].

- Data Collection: Execute experiments with appropriate quality controls [10].

- Model Calibration: Estimate parameters using collected data [10].

- Model Validation: Assess model performance against independent data [10].

- Decision Support: Use model for simulation and prediction to inform development decisions [10].

Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) Protocol

MBDoE represents a systematic approach for designing experiments specifically for mathematical model calibration [15]:

- Model Structure Definition: Establish mathematical model form with unknown parameters [15].

- Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Identify parameters with greatest influence on model outputs [15].

- Optimal Experimental Design: Determine experimental conditions that maximize information content for parameter estimation [15].

- Experiment Execution: Conduct experiments according to designed conditions [15].

- Parameter Estimation: Fit model parameters to experimental data [15].

- Model Adequacy Assessment: Evaluate model fit and determine if additional experiments are needed [15].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Data Generation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Power Analysis Software | Calculates required sample sizes based on effect size, variability, and power parameters [22] | Determining group sizes for animal studies, clinical trials, in vitro experiments |

| Data Quality Assessment Tools | Automates data validation, completeness checks, and quality monitoring [16] [18] | Continuous data quality assessment during high-throughput screening, clinical data collection |

| Statistical Computing Environments | Implements statistical tests, parameter estimation algorithms, and model fitting procedures [22] | R, Python, SAS for parameter estimation, model calibration, and simulation |

| Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) | Tracks samples, experimental conditions, and results with audit trails [17] | Maintaining data integrity and provenance in chemical and biological experiments |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling Software | Simulates drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [10] | Predicting human pharmacokinetics from preclinical data, drug-drug interaction studies |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Platforms | Integrates systems biology with pharmacology to model drug effects [10] | Mechanism-based prediction of drug efficacy and safety in complex biological systems |

The reliable estimation of parameters in scientific research depends on a systematic approach to data quality, data types, and data quantity. By implementing rigorous data quality dimensions, researchers can ensure that their datasets accurately represent the underlying biological or chemical phenomena under investigation. Through appropriate categorization and handling of different data types, analysts can select estimation methods that respect the mathematical properties of their measurements. Finally, by applying principled experimental design and power analysis, scientists can determine the data quantities necessary to achieve sufficient precision while utilizing resources efficiently.

The integration of these three elements—quality, type, and quantity—creates a foundation for parameter estimation that yields reproducible, biologically relevant, and statistically sound results. As model-informed approaches continue to gain prominence across scientific disciplines, the thoughtful consideration of data requirements at the experimental design stage becomes increasingly critical for generating knowledge that advances both fundamental understanding and applied technologies.

In statistical inference, the estimation of unknown population parameters from sample data is foundational. Two primary paradigms exist: point estimation, which provides a single "best guess" value [23] [24], and interval estimation, which provides a range of plausible values along with a stated level of confidence [23] [25]. This guide frames these concepts within the broader research problem of formulating a parameter estimation study, detailing methodologies, presenting quantitative comparisons, and providing practical tools for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Point Estimation involves using sample data to calculate a single value (a point estimate) that serves as the best guess for an unknown population parameter, such as the population mean (μ) or proportion (p) [23] [24]. Common examples include the sample mean (x̄) estimating the population mean and the sample proportion (p̂) estimating the population proportion [23]. Its primary advantage is simplicity and direct interpretability [26]. However, a significant drawback is that it does not convey any information about its own reliability or the uncertainty associated with the estimation [23] [27].

Interval Estimation, most commonly expressed as a confidence interval, provides a range of values constructed from sample data. This range is likely to contain the true population parameter with a specified degree of confidence (e.g., 95%) [23] [25]. An interval estimate accounts for sampling variability and offers a measure of precision, making it a more robust and informative approach for scientific reporting [26] [27].

The fundamental difference lies in their treatment of uncertainty: a point estimate is a specific value, while an interval estimate explicitly quantifies uncertainty by providing a range [23].

Quantitative Comparison and Data Presentation

The following tables summarize key differences and example calculations for point and interval estimates.

Table 1: Conceptual and Practical Differences

| Aspect | Point Estimate | Interval Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A single value estimate of a population parameter. [23] | A range of values used to estimate a population parameter. [23] |

| Precision & Uncertainty | Provides a specific value but does not reflect uncertainty or sampling variability. [23] | Provides a range that accounts for sampling variability, reflecting uncertainty. [23] |

| Confidence Level | Not applicable. | Accompanied by a confidence level (e.g., 95%) indicating the probability the interval contains the true parameter. [23] |

| Primary Use Case | Simple communication of a "best guess"; input for downstream deterministic calculations. [26] | Conveying the reliability and precision of an estimate; basis for statistical inference. [27] |

| Information Conveyed | Location. | Location and precision. |

Table 2: Common Point Estimate Calculations [23]

| Parameter | Point Estimator | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Population Mean (μ) | Sample Mean (x̄) | x̄ = (1/n) Σ X_i |

| Population Proportion (p) | Sample Proportion (p̂) | p̂ = x / n |

| Population Variance (σ²) | Sample Variance (s²) | s² = [1/(n-1)] Σ (X_i - x̄)² |

Table 3: Common Interval Estimate (Confidence Interval) Calculations [23]

| Parameter (Assumption) | Confidence Interval Formula | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (σ known) | x̄ ± z*(σ/√n) | z: Critical value from standard normal distribution. |

| Mean (σ unknown) | x̄ ± t*(s/√n) | t: Critical value from t-distribution with (n-1) df. |

| Proportion | p̂ ± z*√[p̂(1-p̂)/n] | z: Critical value; n: sample size. |

Table 4: Example from Drug Development Research (Illustrative Parameters) [28]

| Therapeutic Area | Phase 3 Avg. Duration (Months) | Phase 3 Avg. Patients per Trial | Notes on Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Average | 38.0 | 630 | Weighted averages from multiple databases (Medidata, clinicaltrials.gov, FDA DASH). [28] |

| Pain & Anesthesia | Not Specified | 1,209 | High variability in patient enrollment across therapeutic areas. [28] |

| Hematology | Not Specified | 233 | Demonstrates the range of values, underscoring the need for interval estimates. [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Estimation

Formulating a parameter estimation problem requires a structured methodology. Below are detailed protocols for key estimation approaches.

Protocol for Deriving a Point Estimate via Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

Objective: To find the parameter value that maximizes the probability (likelihood) of observing the given sample data. Procedure:

- Model Specification: Define the probability density (or mass) function for the data, f(x; θ), where θ is the unknown parameter(s). [24]

- Likelihood Function Construction: Given a random sample (X₁, X₂, ..., Xₙ), form the likelihood function L(θ) = ∏ f(xᵢ; θ), the joint probability of the sample. [24]

- Log-Likelihood: Compute the log-likelihood function, ℓ(θ) = log L(θ), to simplify differentiation. [24]

- Maximization: Take the derivative of ℓ(θ) with respect to θ, set it equal to zero: dℓ(θ)/dθ = 0. [24]

- Solution: Solve the resulting equation(s) for θ. The solution, denoted θ̂MLE, is the maximum likelihood estimate. [24] [29] Interpretation: θ̂MLE is the parameter value under which the observed data are most probable.

Protocol for Deriving a Point Estimate via Method of Moments (MOM)

Objective: To estimate parameters by equating sample moments to theoretical population moments. Procedure:

- Identify Parameters: Determine the number (k) of unknown parameters to estimate. [24]

- Express Population Moments: Calculate the first 'k' theoretical population moments (e.g., mean μ, variance σ²) as functions of the unknown parameters. [24]

- Calculate Sample Moments: Calculate the corresponding sample moments from the data. For the r-th moment: m_r = (1/n) Σ Xᵢʳ. [24]

- Equate and Solve: Set the population moment equations equal to the sample moments: μr(θ) = mr for r = 1, ..., k. Solve this system of equations for the parameters. [24] [29] Interpretation: The MOM estimate provides a simple, intuitive estimator that may be less efficient than MLE but is often easier to compute.

Protocol for Constructing a Confidence Interval for a Population Mean (σ Unknown)

Objective: To construct a range that has a 95% probability of containing the true population mean μ. Procedure:

- Collect Data: Obtain a random sample of size n, recording values X₁, X₂, ..., Xₙ.

- Calculate Sample Statistics: Compute the sample mean (x̄) and sample standard deviation (s). [23]

- Determine Critical Value: Based on the desired confidence level (e.g., 95%) and degrees of freedom (df = n-1), find the two-tailed critical t-value (t*) from the t-distribution table. [23]

- Compute Standard Error: Calculate the standard error of the mean: SE = s / √n. [23]

- Calculate Margin of Error: ME = t* × SE. [23]

- Construct Interval: The 95% confidence interval is: (x̄ - ME, x̄ + ME). [23] Interpretation: We are 95% confident that this interval captures the true population mean μ. The "95% confidence" refers to the long-run success rate of the procedure. [30]

Visualization of the Parameter Estimation Workflow

Title: Workflow for Statistical Parameter Estimation from Sample Data

Types of Intervals and Their Relationships

It is crucial to distinguish between confidence intervals, prediction intervals, and tolerance intervals, as they address different questions [30].

Title: Comparison of Confidence, Prediction, and Tolerance Intervals

- Confidence Interval (CI): Quantifies uncertainty about a population parameter (e.g., mean). It becomes narrower with increased sample size, theoretically collapsing to the true parameter value [30].

- Prediction Interval (PI): Quantifies uncertainty about a future individual observation. It is wider than a CI as it must account for both parameter uncertainty and individual data point variability. It does not converge to a single value as sample size increases [30].

- Tolerance Interval (TI): Provides a range that, with a specified confidence level (e.g., 95%), contains at least a specified proportion (e.g., 95%) of the population. It is used for quality control and setting specification limits [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Tools for Parameter Estimation Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Estimation Research |

|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | A fundamental algorithm for finding point estimates that maximize the probability of observed data. Critical for fitting complex models (e.g., PBPK). [24] [31] |

| Method of Moments (MOM) | A simpler, sometimes less efficient, alternative to MLE for deriving initial point estimates. [24] [29] |

| Nonlinear Least-Squares Solvers | Core algorithms (e.g., quasi-Newton, Nelder-Mead) for estimating parameters by minimizing the difference between model predictions and observed data, especially in pharmacokinetics. [31] |

| Bootstrapping Software | A resampling technique used to construct non-parametric confidence intervals, especially useful when theoretical distributions are unknown. [23] |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A Bayesian estimation method for sampling from complex posterior distributions to obtain point estimates (e.g., posterior mean) and credible intervals (Bayesian analog of CI). [24] |

| Statistical Software (R, Python SciPy/Statsmodels) | Provides libraries for executing MLE, computing confidence intervals, and performing bootstrapping. [24] |

| PBPK/QSP Modeling Platforms | Specialized software (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) that integrate parameter estimation algorithms to calibrate complex physiological models against experimental data. [31] |

Formulating the Parameter Estimation Problem within Research

A well-formulated parameter estimation problem is the backbone of quantitative research. The process involves:

- Defining the Target Parameter (θ): Clearly state the population quantity of interest (e.g., mean drug development phase duration, efficacy proportion). [28] [29]

- Selecting the Estimation Paradigm: Choose between point or interval estimation based on the research goal. For reporting final results or assessing precision, interval estimates are mandatory. For initial model fitting or inputs to deterministic models, point estimates may suffice. [26]

- Choosing an Estimator and Method: Select an appropriate statistic (e.g., sample mean, MLE) and a method for calculating it (or its interval). Considerations include bias, efficiency, and model assumptions. [24] [27]

- Assessing Estimator Properties: Evaluate the chosen estimator's unbiasedness, consistency, and efficiency within the context of the study. [24]

- Implementing and Validating: Use appropriate algorithms and software to perform the estimation. For complex models, use multiple algorithms and initial values to ensure credible results. [31]

- Contextual Interpretation: Report estimates within the research narrative. A point estimate provides a central value, but an interval estimate formally communicates the uncertainty, which is critical for risk assessment in fields like drug development [28] and for making robust scientific conclusions [26].

The Optimization Blueprint: Translating Your Problem into a Solvable Formulation

In scientific research and industrial development, the formulation of a parameter estimation problem is foundational for building predictive mathematical models. Central to this process is the systematic definition of design variables—the specific parameters and initial states whose values must be determined from experimental data to calibrate a model. In the context of Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE), design variables represent the unknown quantities in a mathematical model that researchers aim to estimate with maximum precision through strategically designed experiments [15]. The careful identification of these variables is a critical first step that directly influences the reliability of the resulting model and the efficiency of the entire experimental process.

In technical domains such as chemical process engineering and pharmaceutical development, models—whether mechanistic, data-driven, or semi-empirical—serve as quantitative representations of system behavior [15]. The parameter precision achieved through estimation dictates a model's predictive power and practical utility. A well-formulated set of design variables enables researchers to focus experimental resources on obtaining the most informative data, thereby accelerating model calibration and reducing resource consumption. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for identifying and classifying these essential elements within a parameter estimation problem, with specific applications in drug development and process engineering.

Theoretical Foundations and Classification

Core Components of Design Variables

In a parameter estimation problem, design variables can be systematically categorized into two primary groups:

- Model Parameters: These are intrinsic properties of the system that remain constant under the defined experimental conditions but are unknown a priori. Examples include kinetic rate constants in a reaction network, thermodynamic coefficients, material properties, and affinity constants in pharmacological models [15] [10].

- Initial States: These variables define the starting conditions of the system at the beginning of an experiment or observational period. Unlike parameters, initial states are often set by the experimenter but may also be unknown and require estimation for model initialization. Examples include initial reactant concentrations in a batch reactor and baseline biomarker levels in a physiological system [15].

The process of identifying these variables requires a deep understanding of the system's underlying mechanisms. The relationship between a model's output and its design variables is typically expressed as:

y = f(t, θ, x₀, u)

Where:

- y is the model output or response variable.

- f is the mathematical representation of the system.

- t is time (or an independent variable).

- θ is the vector of model parameters to be estimated.

- x₀ is the vector of initial states.

- u is the vector of controllable input variables or experimental design factors.

The MBDoE Framework for Parameter Precision

Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) is a structured methodology for designing experiments that maximize the information content of the collected data for the specific purpose of parameter estimation [15]. Within this framework, the quality of parameter estimates is often quantified using the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM). The FIM is inversely related to the variance-covariance matrix of the parameter estimates, and its maximization is a central objective in MBDoE. The FIM (M) for a dynamic system is calculated as:

M = ∑ᵢ (∂y/∂θ)ᵀ Q⁻¹ (∂y/∂θ)

Where:

- The summation is over all experimental samples.

- ∂y/∂θ is the sensitivity matrix of the model outputs with respect to the parameters.

- Q is the variance-covariance matrix of the measurement errors.

The primary goal is to design experiments that maximize a scalar function of the FIM (e.g., its determinant, known as D-optimality), which directly leads to minimized confidence regions for the estimated parameters, θ [15].

Methodologies for Identifying Design Variables

A systematic, multi-stage approach is required to reliably identify the parameters and initial states that constitute the design variables for estimation. The following workflow outlines this process, from initial model conceptualization to the final selection of variables for the experimental design.

A Systematic Workflow for Variable Identification

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and iterative nature of the identification process.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

For each key step in the workflow, a specific methodological approach is required.

Protocol for Preliminary Sensitivity Analysis (Step 2)

- Objective: To rank candidate parameters based on their influence on model outputs.

- Procedure:

- Define a nominal parameter vector (θ₀) and a plausible range for each parameter based on literature or expert knowledge.

- Simulate the model output, y(t, θ₀).

- For each parameter θᵢ, compute the local sensitivity coefficient: Sᵢ(t) = ∂y(t)/∂θᵢ. This is often done via finite differences or by solving associated sensitivity equations.

- Aggregate sensitivity measures (e.g., the L₂-norm of Sᵢ(t) over the time course) to rank parameters.

- Output: A ranked list of parameters, prioritizing those with the highest sensitivity for inclusion as design variables.

Protocol for Assessing Practical Identifiability (Step 5)

- Objective: To determine if the available experimental data is sufficient to uniquely estimate the selected parameters.

- Procedure:

- Using initial experimental data, compute the FIM.

- Check the condition number of the FIM. A very high condition number indicates potential collinearity between parameters (non-identifiability).

- Compute the profile likelihood for each parameter. This involves varying one parameter while re-optimizing all others and plotting the resulting cost function value.

- A uniquely identifiable parameter will show a well-defined, concave minimum in its profile likelihood. A flat profile indicates non-identifiability.

- Output: A diagnosis of which parameters are practically identifiable, guiding model simplification or experimental redesign.

Quantitative Data and Application in Drug Development

Quantitative Analysis of Design Variable Impact

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research, highlighting the performance of advanced methodologies in managing design variables for parameter estimation.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Advanced Frameworks in Parameter Estimation and Variable Optimization

| Framework/Method | Primary Application | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Implication for Design Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE + HSAPSO [32] | Drug classification & target identification | Classification Accuracy | 95.52% | Demonstrates high precision in identifying relevant biological parameters from complex data. |

| Computational Efficiency | 0.010 s/sample | Enables rapid, iterative testing of different variable sets and model structures. | ||

| Stability (Variability) | ± 0.003 | Indifies robust parameter estimates with low sensitivity to noise, confirming good variable selection. | ||

| MBDoE Techniques [15] | Chemical process model calibration | Parameter Precision | Up to 40% improvement vs. OFAT | Systematically designed experiments around key variables drastically reduce confidence intervals of estimates. |

| HSAPSO-SAE [32] | Pharmaceutical informatics | Hyperparameter Optimization | Adaptive tuning of SAE parameters | Validates the role of meta-optimization (optimizing the optimizer's parameters) for handling complex variable spaces. |

| Fit-for-Purpose MIDD [10] | Model-Informed Drug Development | Contextual Alignment | Alignment with QOI/COU | Ensures the selected design variables are directly relevant to the specific drug development question. |

Application in Pharmaceutical Development

In Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), the "fit-for-purpose" principle dictates that the selection of design variables must be closely aligned with the Key Questions of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) at each stage [10]. The following table maps common design variables to specific drug development activities, illustrating this alignment.

Table 2: Design Variables and Their Roles in Stages of Drug Development

| Drug Development Stage | Common MIDD Tool(s) | Typical Design Variables (Parameters & Initial States) for Estimation | Purpose of Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery | QSAR [10] | - IC₅₀- Binding affinity constants- Physicochemical properties (logP, pKa) | Prioritize lead compounds based on predicted activity and properties. |

| Preclinical | PBPK [10] | - Tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients- Clearance rates- Initial organ concentrations | Predict human pharmacokinetics and safe starting dose for First-in-Human (FIH) trials. |

| Clinical (Phase I) | Population PK (PPK) [10] | - Volume of distribution (Vd)- Clearance (CL)- Inter-individual variability (IIV) on parameters | Characterize drug exposure and its variability in a human population. |

| Clinical (Phase II/III) | Exposure-Response (E-R) [10] | - E₀ (Baseline effect)- Eₘₐₓ (Maximal effect)- EC₅₀ (Exposure for 50% effect) | Quantify the relationship between drug exposure and efficacy/safety outcomes to inform dosing. |

The hierarchically self-adaptive particle swarm optimization (HSAPSO) algorithm, cited in Table 1, exemplifies a modern approach to handling complex variable estimation. It dynamically adjusts its own parameters during optimization, leading to more efficient and reliable convergence on the optimal values for the primary model parameters (θ) [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of experiments for parameter estimation relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parameter Estimation Experiments

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function in Variable Identification & Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Simulation Software | MATLAB, SimBiology, R, Python (SciPy, PyMC3), NONMEM, Monolix | Provides the computational environment to implement mathematical models, perform simulations, and execute parameter estimation algorithms. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Sobol' method (for global SA), Morris method, software-integrated solvers | Quantifies the influence of each candidate parameter on model outputs, guiding the selection of design variables for estimation. |

| Optimization Algorithms | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [32], Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), Bayesian Estimation | The core computational engine for finding the parameter values that minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental data. |

| Model-Based DoE Platforms | gPROMS FormulatedProducts, CADRE | Specialized software to design optimal experiments that maximize information gain for the specific set of design variables. |

| Data Management & Curation | Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs), SQL databases, FAIR data principles | Ensures the quality, traceability, and accessibility of experimental data used for parameter estimation, which is critical for reliable results. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Biochemical activity assays, ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) profiling | Generates rich, quantitative datasets from which parameters like IC₅₀, clearance, and permeability can be estimated. |

The precise definition of design variables—the parameters and initial states to be estimated—is the cornerstone of formulating a robust parameter estimation problem. This process is not a one-time event but an iterative cycle of model hypothesizing, variable sensitivity testing, and experimental design refinement. As demonstrated by advanced applications in drug development, a disciplined and "fit-for-purpose" approach to variable selection, supported by methodologies like MBDoE and modern optimization algorithms, is critical for building models with high predictive power. This, in turn, accelerates scientific discovery and de-risks development processes in high-stakes fields like pharmaceuticals and chemical engineering.

In scientific and engineering disciplines, particularly in pharmaceutical development and systems biology, the process of parameter estimation is fundamental for building accurate mathematical models from observed data. This process involves calibrating model parameters so that the model's output closely matches experimental measurements. The core of this calibration lies in the objective function (also known as a cost or loss function), which quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and observed data [33] [34]. The formulation of this function directly influences which parameter values will be identified as optimal, making its selection a critical step in model development.

Parameter estimation is fundamentally framed as an optimization problem where the solution is the set of parameter values that minimizes this discrepancy [33]. This optimization problem consists of several key components: the design variables (parameters to be estimated), the objective function that measures model-data discrepancy, and optional bounds or constraints on parameter values based on prior knowledge [33]. Within this framework, the choice of objective function determines how "goodness-of-fit" is quantified, with different measures having distinct statistical properties, computational characteristics, and sensitivities to various data features.

Fundamental Measures of Fit

Sum of Squared Errors (SSE)

The Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) is one of the most prevalent objective functions in scientific modeling. It is defined as the sum of the squared differences between observed values and model predictions [33] [34]. For a dataset with N observations, the SSE formulation is:

[ \text{SSE} = \sum{i=1}^{N} (y{i} - f(xi, \theta))^2 = \sum{i=1}^{N} e_i^2 ]

where (yi) represents the actual observed value, (f(xi, \theta)) is the model prediction given inputs (xi) and parameters (\theta), and (ei) is the error residual for the (i)-th data point [33] [34].

The SSE loss function has an intuitive geometric interpretation – it represents the total area of squares constructed on the errors between data points and the model curve [34]. In this geometric context, finding the parameter values that minimize the SSE is equivalent to finding the model that minimizes the total area of these squares.

A common variant is the Mean Squared Error (MSE), which divides the SSE by the number of observations [35]. While MSE and SSE share the same minimizer (the same parameter values minimize both functions), MSE offers practical advantages in optimization algorithms like gradient descent by maintaining smaller gradient values, which often leads to more stable and efficient convergence [35].

Sum of Absolute Errors (SAE)

The Sum of Absolute Errors (SAE), also known as the Sum of Absolute Deviations (SAD), provides an alternative approach to quantifying model-data discrepancy [33] [36]. The SAE is defined as:

[ \text{SAE} = \sum{i=1}^{N} |y{i} - f(x_i, \theta)| ]

Unlike SSE, which squares the errors, SAE uses the absolute value of each error term [33] [36]. This fundamental difference in mathematical formulation leads to distinct properties in how the two measures handle variations between predictions and observations.

SAE is particularly valued for its robustness to outliers in the data [37]. Because SAE does not square the errors, it gives less weight to large residuals compared to SSE, making the resulting parameter estimates less sensitive to extreme or anomalous data points [37]. This characteristic makes SAE preferable in situations where the data may contain significant measurement errors or when the underlying error distribution has heavy tails.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) takes a fundamentally different approach by framing parameter estimation as a statistical inference problem [38] [39]. Rather than directly minimizing a measure of distance between predictions and observations, MLE seeks the parameter values that make the observed data most probable under the assumed statistical model [39].

The core concept in MLE is the likelihood function. For a set of observed data points (x1, x2, \ldots, x_n), and parameters (\theta), the likelihood function (L(\theta)) is defined as the joint probability (or probability density) of observing the data given the parameters [38] [39]:

[ L(\theta) = P(X1=x1, X2=x2, \ldots, Xn=xn; \theta) ]

for discrete random variables, or

[ L(\theta) = f(x1, x2, \ldots, x_n; \theta) ]

for continuous random variables, where (f) is the joint probability density function [38].

The maximum likelihood estimate (\hat{\theta}) is the parameter value that maximizes this likelihood function [39]:

[ \hat{\theta} = \underset{\theta}{\operatorname{arg\,max}} \, L(\theta) ]

In practice, it is often convenient to work with the log-likelihood (\ell(\theta) = \ln L(\theta)), as products in the likelihood become sums in the log-likelihood, which simplifies differentiation and computation [39].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Objective Functions

| Measure | Mathematical Formulation | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) | (\sum{i=1}^{N} (yi - f(x_i, \theta))^2) | Differentiable, sensitive to outliers, maximum likelihood for normal errors | Linear regression, nonlinear least squares, model calibration |

| Sum of Absolute Errors (SAE) | (\sum{i=1}^{N} |yi - f(x_i, \theta)|) | Robust to outliers, non-differentiable at zero | Robust regression, applications with outlier contamination |

| Maximum Likelihood (MLE) | (\prod{i=1}^{N} P(yi | xi, \theta)) or (\prod{i=1}^{N} f(yi | xi, \theta)) | Statistically efficient, requires error distribution specification | Statistical modeling, parametric inference, generalized linear models |

Theoretical Foundations and Relationships

Statistical Interpretations

The choice between SSE and SAE objective functions has profound statistical implications that extend beyond mere optimization. When errors are independent and identically distributed according to a normal distribution, minimizing the SSE yields parameter estimates that are also maximum likelihood estimators [39] [37]. This connection provides a solid statistical foundation for the SSE objective function under the assumption of normally distributed errors.

The relationship between SSE and MLE becomes clear when we consider the normal distribution explicitly. For a normal error distribution with constant variance, the log-likelihood function is proportional to the negative SSE, which means maximizing the likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the sum of squares [39]. This important relationship explains why SSE has been so widely adopted in statistical modeling – it represents the optimal estimation method when the Gaussian assumption holds.

For SAE, a similar connection exists to the Laplace distribution. If errors follow a Laplace (double exponential) distribution, then maximizing the likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the sum of absolute errors [37]. This provides a statistical justification for SAE when errors have heavier tails than the normal distribution.

Geometric and Computational Considerations

From a geometric perspective, SSE and SAE objective functions lead to different solution characteristics in optimization problems. The SSE function is differentiable everywhere, which enables the use of efficient gradient-based optimization methods [33] [34]. The resulting optimization landscape is generally smooth, often with a single minimum for well-behaved models.

In contrast, the SAE objective function is not differentiable at points where residuals equal zero, which can present challenges for some optimization algorithms [37]. However, SAE has the advantage of being more robust to outliers because it does not square the errors, thereby giving less weight to extreme deviations compared to SSE [37].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for selecting an appropriate objective function based on data characteristics and modeling goals:

Implementation and Optimization Frameworks

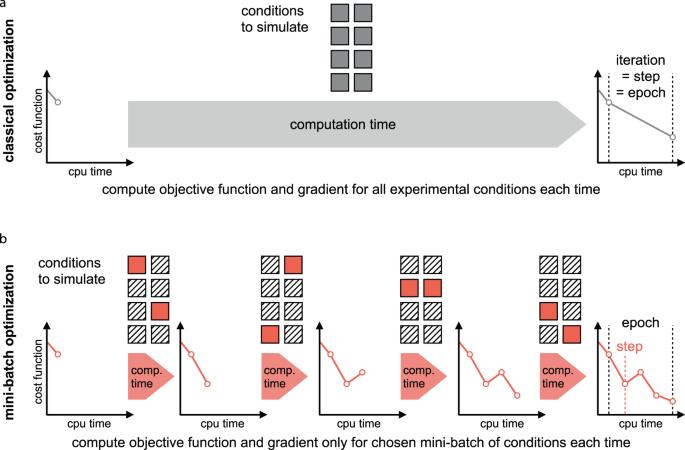

Optimization Methods and Problem Formulation