Taming the Multi-Omics Data Deluge: Advanced Strategies for Managing Dimensionality and Diversity in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with the challenges of multi-omics data integration.

Taming the Multi-Omics Data Deluge: Advanced Strategies for Managing Dimensionality and Diversity in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with the challenges of multi-omics data integration. It explores the foundational concepts of data heterogeneity across genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, and details cutting-edge computational methods, including AI and machine learning, for effective data synthesis. The content further offers practical solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization issues, supported by comparative analyses of real-world applications in areas like precision oncology and biomarker discovery. By synthesizing the latest methodologies and validation frameworks, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to transform complex, high-dimensional multi-omics data into actionable biological insights and accelerate therapeutic development.

Understanding the Multi-Omics Landscape: From Data Generation to Core Challenges

The "Four Big Omics" layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—represent a hierarchical flow of biological information that systematically describes the inner workings of a cell [1]. Studying these layers together in a multi-omics approach provides a comprehensive picture of biological systems, enabling researchers to uncover complex mechanisms in health and disease that are not visible when examining a single layer in isolation [2]. This integration is crucial for discovering biomarkers, understanding disease etiology, and identifying novel therapeutic targets [3].

The Four Core Omics Layers

| Omics Layer | Molecule of Study | Key Function | Primary Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA (genes) | Provides the static, hereditary blueprint of an organism; reveals genetic variants and structural changes [4]. | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), Sanger Sequencing, Microarrays [1] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA (transcripts) | Reveals dynamic gene expression; shows which genes are active and their expression levels [4]. | RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq), RT-PCR, qPCR, Microarrays [1] [2] |

| Proteomics | Proteins | Identifies and quantifies the functional effectors of the cell; includes analysis of post-translational modifications (PTMs) [1] [4]. | Mass Spectrometry (e.g., Orbitrap, FT-ICR), Western Blot, ELISA [1] [2] |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites | Captures the real-time biochemical phenotype through small-molecule metabolites, offering a snapshot of cellular activity [4]. | Mass Spectrometry, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [1] [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

In multi-omics study design, what is the recommended hierarchy or order for sampling different omics layers?

A rational approach for disease state phenotyping often follows this hierarchy: Genome -> Epigenome -> Transcriptome -> Proteome -> Metabolome -> Microbiome [3]. This order reflects the flow of biological information. However, the optimal sampling frequency for each layer varies based on its dynamic nature.

- Genomics: Requires a single measurement per individual as it provides a static blueprint of the DNA, which remains largely unchanged [3].

- Transcriptomics: Often necessitates more frequent assessments because gene expression is highly dynamic and sensitive to treatments, environment, and daily behaviors [3].

- Proteomics: Generally requires a lower testing frequency than transcriptomics. Proteins have longer half-lives, making their expression levels and modifications relatively stable over time [3].

- Metabolomics: Can be highly variable and may need to be targeted frequently, as metabolites provide a real-time snapshot of ongoing metabolic activities [3].

Why do my RNA-seq and proteomics data show only weak correlations for the same targets?

This is a common and expected challenge, and a weak correlation does not necessarily indicate an experimental error. Key reasons for this discordance include:

- Biological Regulation: mRNA and protein abundance are regulated independently. Post-transcriptional regulation, differences in translation rates, and widely varying protein half-lives (which can differ significantly from mRNA half-lives) all contribute to a disconnect between transcript and protein levels [5].

- Technical Factors: The technologies used have different inherent biases and limitations. RNA-seq is highly sensitive, while mass spectrometry-based proteomics can be biased towards detecting highly abundant proteins and may suffer from issues with missing values for low-abundance proteins [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Do: Acknowledge and investigate the discordance. Use pathway analysis to see if related genes and proteins show consistent directional changes, even if individual correlations are weak.

- Do: Ensure your samples for both omics layers are matched (from the same individual and time point) to reduce noise from biological variation [5].

- Don't: Overinterpret weak correlations as biologically meaningless or as a failure. The disconnect itself is a rich source of biological insight into post-transcriptional control mechanisms [5].

What are the primary causes of failed multi-omics data integration, and how can I avoid them?

Failed integration often stems from technical and analytical pitfalls rather than wet-lab failure [5].

Pitfall 1: Unmatched Samples Across Layers. Integrating RNA-seq from one set of patients with proteomics from another set leads to confusing and unreliable results [5].

- Solution: Always start with a matching matrix to visualize which samples are available for each modality. Prioritize analysis on the subset of samples that have data across all omics layers [5].

Pitfall 2: Improper Normalization Across Modalities. Each omics technology has its own data distribution (e.g., RNA-seq counts, proteomics spectral counts, methylation β-values). Naively combining them skews the analysis [5] [7].

Pitfall 3: Ignoring Batch Effects. Batch effects can compound when data for different omics layers are generated in different labs or at different times, creating dominant technical patterns that mask true biological signals [5].

- Solution: Apply batch effect correction methods both within and across omics layers. Always verify that biological signals, not batch identities, drive the structure in the integrated data [5].

How do I choose the right integration method for my multi-omics dataset?

The choice of method depends on your biological question and data structure. There is no one-size-fits-all solution [7]. The table below summarizes common approaches.

| Method | Type | Key Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ [7] | Unsupervised | Uses a Bayesian framework to infer latent factors that capture shared and unique sources of variation across omics layers. | Exploring data without pre-defined groups; identifying hidden structures and sources of variation. |

| DIABLO [7] | Supervised | Uses a multi-block generalization of PLS-DA to identify components that maximize separation between known groups/phenotypes. | Classifying known sample groups (e.g., disease vs. healthy) and identifying multi-omics biomarker panels. |

| SNF [7] | Unsupervised | Constructs and fuses sample-similarity networks from each omics layer into a single combined network. | Clustering samples into molecular subtypes based on multiple data types. |

Essential Methodologies & Workflows

Standardized Protocol for Multi-Omics Data Preprocessing

Effective integration hinges on proper data harmonization. Follow this generalized workflow to prepare diverse omics data for integration [8] [6]:

Experimental Workflow for a Multi-Omics Study

A typical integrated multi-omics project follows a sequence of experimental and computational steps, from sample collection to biological insight [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Molecular biology techniques are foundational to nucleic acid-based omics methods (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics) [2]. The following table details essential reagents and their functions in multi-omics workflows.

| Research Reagent | Function in Multi-Omics | Primary Omics Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Enzymes that synthesize new DNA strands; critical for PCR, library amplification for NGS, and cDNA synthesis [2]. | Genomics, Transcriptomics |

| Reverse Transcriptases | Enzymes that convert RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA); essential for gene expression analysis via RT-PCR and RNA-seq library prep [2]. | Transcriptomics |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for DNA synthesis by polymerases [2]. | Genomics, Transcriptomics |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start point for DNA synthesis; required for PCR, qPCR, and targeted sequencing [2]. | Genomics, Transcriptomics |

| Methylation-Sensitive Enzymes | Restriction enzymes or other modifying enzymes used to detect and analyze epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation [2]. | Epigenomics |

| PCR Master Mixes | Optimized, ready-to-use solutions containing buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, and MgCl₂; ensure robust and reproducible PCR amplification [2]. | Genomics, Transcriptomics |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometers | Instruments like Orbitrap and FT-ICR that provide high mass accuracy and resolution for identifying and quantifying proteins and metabolites [1]. | Proteomics, Metabolomics |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the "Curse of Dimensionality" and why is it a problem in multi-omics research?

The "Curse of Dimensionality" refers to a collection of phenomena that arise when analyzing data in high-dimensional spaces, which do not occur in low-dimensional settings like our everyday three-dimensional world [9]. The term was coined by Richard E. Bellman when considering problems in dynamic programming [9].

In multi-omics research, this is problematic because:

- Data Sparsity: As dimensionality increases, the volume of space grows so fast that available data becomes sparse. To obtain reliable results, the amount of data needed often grows exponentially with the dimensionality [9] [10].

- Loss of Discriminative Power: Distance metrics like Euclidean distance lose meaning in high-dimensional spaces. The difference between nearest and farthest neighbors diminishes, making it difficult to distinguish between data points [9] [10].

- Combinatorial Explosion: In problems where variables can take several discrete values, a huge number of combinations of values must be considered. With

dbinary variables, there are2^dpossible combinations [9]. - Decreased Predictive Power: A fixed number of training samples leads to the "peaking phenomenon" or "Hughes phenomenon," where a classifier's predictive power first increases with more features but then starts to deteriorate after a certain optimal dimensionality is surpassed [9] [10].

What are the common symptoms that my analysis is suffering from the curse of dimensionality?

You can identify the curse of dimensionality through these common symptoms [9] [11] [10]:

- Model Overfitting: Your model performs excellently on training data but fails to generalize to new, unseen data.

- High Model Variance: Small changes in the training data lead to significant changes in the model and its results.

- Unstable Feature Selection: The set of "important" features changes drastically when the dataset is slightly perturbed (e.g., during cross-validation).

- Poor Cluster Identification: Clustering algorithms fail to find meaningful, stable groups in your data.

- Spurious Correlations: The analysis identifies false associations between variables due to chance, not true biological relationships.

My multi-omics data comes from different technologies. How does this worsen the curse of dimensionality?

Multi-omics data integration faces specific challenges that intensify the curse of dimensionality [3] [7]:

- Heterogeneous Data Structures: Each omics data type (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) has its own data structure, statistical distribution, measurement error, and noise profile [7].

- Lack of Pre-processing Standards: The absence of standardized preprocessing protocols for each data type introduces additional variability when datasets are harmonized [7].

- Matched vs. Unmatched Data: The problem is compounded in "unmatched multi-omics," where data is generated from different, unpaired samples, requiring complex 'diagonal integration' methods [7].

What are the main strategies to mitigate the curse of dimensionality?

There are several core strategies to combat the curse of dimensionality [10] [12]:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Transforming high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while retaining essential information.

- Feature Selection: Identifying and retaining the most relevant features while discarding irrelevant or redundant ones.

- Regularization: Adding a penalty term to the model's loss function to prevent overfitting and reduce model complexity.

- Ensemble Methods: Combining multiple models to improve overall performance and stability.

The table below compares the two primary feature-focused approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Dimensionality Management Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Key Methods | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality Reduction | Transforms original features into a new, smaller set of features. | PCA (unsupervised), LDA (supervised), t-SNE, autoencoders [10] [12]. | Exploring data structure, visualization, when most features contain some signal. |

| Feature Selection | Selects a subset of the original features without transformation. | Filter (statistical tests), Wrapper (model-based), Embedded (Lasso regression) [10] [12]. | Interpretability is key, when only a few features are biologically relevant. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Remedying High-Dimensionality Problems in Multi-Omics Integration

Problem: Your multi-omics integration model (e.g., for disease subtyping or biomarker discovery) is overfitting, producing unstable, or biologically uninterpretable results.

Symptoms:

- Clusters of samples are not consistent across different algorithms.

- The list of key features (e.g., genes, proteins) driving the model changes dramatically with slight changes in the data.

- Model performance is excellent on training data but poor on validation data or independent cohorts.

Investigation and Solutions:

Step 1: Assess Data Sparsity and Intrinsic Dimensionality

- Action: Perform a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) scree plot. A slow, gradual decline in variance explained by successive components suggests high intrinsic dimensionality and potential sparsity issues [13].

- Toolkit:

prcomp{stats}in R,PCA{FactoMineR}[13].

Step 2: Apply a Robust Dimensionality Reduction or Feature Selection Method Avoid one-at-a-time (OaaT) feature screening, as it is highly unreliable and leads to overestimated effect sizes for "winning" features due to multiple comparison problems [11]. Instead, consider the following advanced methods suitable for multi-omics data:

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods to Combat High-Dimensionality

| Method | Type | Key Principle | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA [7] | Unsupervised Integration | Infers a set of latent factors that capture principal sources of variation across data types in a Bayesian framework. | To explore shared and specific sources of variation across omics layers without using sample labels. |

| DIABLO [7] | Supervised Integration | Uses known phenotype labels to identify latent components and select features that are integrative and discriminative. | For classification or prediction tasks (e.g., disease vs. healthy) and biomarker discovery. |

| MCIA [13] | Unsupervised Integration | A multivariate method that aligns multiple omics features onto a shared dimensional space to capture co-variation. | For a joint exploratory analysis of multiple omics datasets from the same samples. |

| Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) [7] | Unsupervised Integration | Constructs and fuses sample-similarity networks (not raw data) for each omics dataset into a single network. | To identify patient subgroups based on multiple data types, especially when relationships are non-linear. |

Step 3: Validate with Appropriate Statistical Rigor

- Action: When using feature selection, employ bootstrap resampling to compute confidence intervals for the rank of feature importance. This provides an honest assessment of which features are robustly selected and reveals a large middle ground of features that cannot be confidently declared "winners" or "losers" [11].

- Avoid Double Dipping: Ensure your cross-validation procedure repeats all steps, including feature selection, for each resample. Using the same data to select features and validate performance gives optimistically biased results [11].

Guide: Improving Generalizability of a High-Dimensional Predictive Model

Problem: You have built a classifier (e.g., using transcriptomics data to predict drug response), but its real-world performance is much lower than expected.

Solution Pathway: The following workflow outlines a robust process for building a generalizable model with high-dimensional omics data:

Key Actions:

- Use Regularization: Apply embedded methods like Lasso (L1) or Ridge (L2) regression. These techniques penalize model complexity during training, effectively performing feature selection and shrinkage to improve generalizability [11] [12].

- Implement Rigorous Validation: Use a nested cross-validation scheme. An inner loop is used for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and an outer loop is used for performance evaluation. This prevents information from the validation set leaking into the model training process and provides an unbiased estimate of performance on new data [11] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Managing High-Dimensionality

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ [7] | A Bayesian framework for unsupervised integration of multi-omics data. | Discovers latent factors that drive variation across multiple omics assays. |

| mixOmics [13] | An R package providing a suite of multivariate methods for the exploration and integration of omics datasets. | Includes methods like DIABLO for supervised integration and sPLS for sparse modeling. |

| OmicsPlayground [7] | An all-in-one web-based platform for the analysis of multi-omics data without coding. | Provides a user-friendly interface for multiple integration methods (SNF, MOFA, DIABLO) and visualizations. |

| Random Forest [11] | An ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their results. | Handles high-dimensional data well for classification and regression; provides built-in feature importance measures. |

| Penalized Regression (e.g., Glmnet) [11] | Fits generalized linear models while applying L1 (Lasso), L2 (Ridge), or mixed (Elastic Net) penalties. | Performs feature selection and regularization simultaneously to build parsimonious models. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary categories of biologically relevant heterogeneity? Biologically relevant heterogeneity is broadly classified into three main categories [15]:

- Population Heterogeneity: Variation in phenotypes among individuals in a population at a single time point.

- Spatial Heterogeneity: Variation in variables at different spatial locations within a sample, such as a tissue section.

- Temporal Heterogeneity: Variation in variables measured as a function of time.

FAQ 2: Why is data heterogeneity a particular problem in multi-omics studies? Multi-omics studies are especially prone to data heterogeneity challenges because each omics technology produces data in different formats and scales [8] [16]. For example, RNA-seq can yield thousands of transcript features, while proteomics and metabolomics may produce only hundreds to a few thousand features. Inconsistencies in sample IDs, nomenclatures, and the platforms themselves further complicate integration [16].

FAQ 3: What are some common technical sources of variation in data generation? Technical variation, or "system variability," can arise from sample preparation, data acquisition, and data processing steps [15]. Batch effects, introduced when samples are processed in different groups or at different times, are a major technical source of heterogeneity that must be identified and corrected during data preprocessing [8].

FAQ 4: How can I measure and quantify heterogeneity in my data? A range of metrics exists, and the choice depends on the data type and question. Common approaches include [15]:

- Entropy measures: Such as Shannon or Simpson indices, to measure diversity.

- Model functions: Like Gaussian mixture models, to identify distinct subpopulations.

- Spatial methods: Such as Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI), to characterize spatial patterns.

- Heterogeneity indices: A set of three indices has been proposed for high-throughput workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Integrate Multi-Omic Datasets Due to Heterogeneity Symptoms: Failure to align datasets for joint analysis, inconsistent results, or errors during computational integration workflows.

| Diagnosis Step | Check | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Preprocessing | Data from different omics platforms have not been standardized. | Standardize and harmonize data to ensure compatibility. This involves normalizing for differences in sample size/concentration, converting to a common scale, and removing technical biases/batch effects [8]. |

| Metadata Quality | Inconsistent or missing sample IDs and descriptive metadata. | Value your metadata. Ensure rich, consistent metadata is provided for all samples to facilitate accurate mapping and integration across datasets [8]. |

| Semantic Heterogeneity | The same entity (e.g., a gene) has different identifiers across databases. | Use ontology-based approaches to create a common knowledge base that resolves naming and semantic conflicts across data sources [17]. |

| Power and Sample Size | The study is underpowered to detect signals amidst noisy, heterogeneous data. | Use tools like MultiPower to perform sample size estimations during study design to ensure the study is adequately powered [16]. |

Problem: Subpopulation Effects are Masked by Population-Averaged Metrics Symptoms: An assay is statistically robust at the well level, but the biological interpretation is inconsistent or fails to explain observed phenotypes.

| Diagnosis Step | Check | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Distribution | Analysis relies solely on mean and standard deviation, assuming a normal distribution. | Shift from population-average to single-cell resolution analyses. Use high-content imaging or flow cytometry to capture data at the individual cell level [15]. |

| Analytical Method | Clustering methods (e.g., k-means) are used but may fail with overlapping or unimodal data. | Apply dimension reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Multiple Co-Inertia Analysis (MCIA). These methods are better suited for identifying gradients and patterns in complex data and can be applied to multi-assay data [13]. |

| Heterogeneity Metric | There is no standard metric to quantify the degree of heterogeneity. | Adopt standardized heterogeneity indices for high-throughput workflows. For spatial data in tissues, consider using a pairwise mutual information method [15]. |

Quantitative Metrics for Heterogeneity

The table below summarizes key metrics for quantifying different types of heterogeneity, as identified in scientific literature [15].

| Category | Metric / Approach | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| General Univariate | Standard Deviation, Skew, Kurtosis | Assumes a normal distribution; insensitive to underlying subpopulations. |

| Population Diversity | Entropy (e.g., Shannon, Simpson) | Established measures of diversity and information content; typically for univariate data. |

| Subpopulation Identification | Gaussian Mixture Models | Assumes data is composed of multiple normally distributed subpopulations; can be applied to multivariate data. |

| Model-Independent | Population Heterogeneity Index (PHI) | A combined, model-independent metric that is descriptive of heterogeneity. |

| Spatial Analysis | Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI) | No assumption of distribution; leverages spatial interactions; applies to multivariate data. |

| Temporal Analysis | Temporal Distance | Method developed on genomic data; measures the distance between robust centers of mass of feature sets over time. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Content Screening (HCS) | An automated microscope imaging system used to extract multiple phenotypic features from large populations of adherent cells, enabling the analysis of population and spatial heterogeneity [15]. |

| Flow Cytometry | A technology used for the analysis of bacterial and suspension cells, allowing for the quantification of protein expression and other characteristics at the single-cell level to assess population heterogeneity [15]. |

| Reference Standards & Controls | Calibration particles and controls essential for characterizing a system's reproducibility. They minimize "system variability" and are critical for achieving consistent, quantitative measurements, especially in flow cytometry [15]. |

| Single-Cell Genomics/Proteomics | Technologies such as single-cell RNA-sequencing that enable the measurement of molecular profiles from individual cells, directly capturing the transcriptional or proteomic heterogeneity within a sample [15]. |

| Dimension Reduction Tools (e.g., mixOmics, INTEGRATE) | Software packages (available in R and Python) that provide algorithms for the integrative exploratory analysis of multi-omics datasets, helping to unravel patterns and relationships amidst heterogeneous data [8] [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Heterogeneity

Protocol 1: Quantifying Cellular Heterogeneity via High-Content Imaging Objective: To identify and quantify distinct subpopulations of cells based on multivariate phenotypic features. Methodology:

- Cell Culture & Treatment: Plate adherent cells in multi-well plates and apply the experimental treatment (e.g., drug compound, genetic perturbation).

- Staining: Fix and stain cells with fluorescent dyes or antibodies targeting relevant cellular components (e.g., nuclei, cytoskeleton, specific proteins).

- Image Acquisition: Use an automated high-content microscope to capture high-resolution images from multiple sites per well across all experimental conditions.

- Feature Extraction: Employ image analysis software to segment individual cells and extract hundreds of quantitative morphological features (e.g., cell size, shape, texture, intensity) for each cell.

- Data Analysis:

- Dimension Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the single-cell data to reduce dimensionality and visualize the major axes of variation [13].

- Clustering & Quantification: Use Gaussian Mixture Models or other clustering algorithms on the principal components to identify distinct phenotypic subpopulations [15]. Quantify the proportion of cells in each cluster and calculate heterogeneity indices (e.g., entropy) to compare conditions.

Protocol 2: Integrating Multi-Omics Datasets to Uncover Molecular Drivers Objective: To integrate transcriptomic and epigenomic data from the same samples to identify coordinated patterns and sources of heterogeneity. Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Process biological samples (e.g., tumor biopsies) to extract both RNA and DNA.

- Data Generation:

- Perform RNA-seq to generate transcriptomic data (gene expression values).

- Perform DNA methylation analysis (e.g., using bisulfite sequencing) to generate epigenomic data (beta values for CpG sites).

- Data Preprocessing:

- Integrative Analysis:

- Use a multivariate dimension reduction technique such as Multiple Co-Inertia Analysis (MCIA), which is designed to identify the linear relationships that best explain the correlated structure across multiple datasets [13].

- Analyze the resulting components to identify which genes and methylation sites contribute most to the shared structure, revealing potential master regulators of heterogeneity.

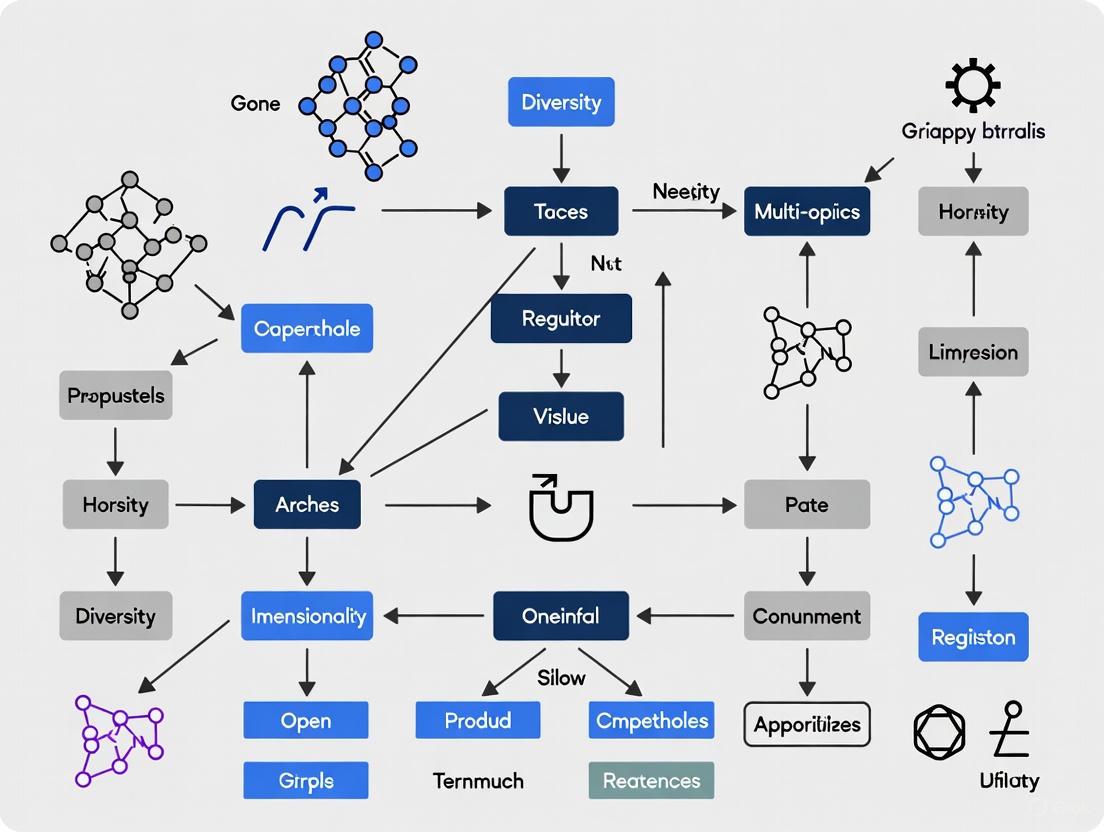

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Data heterogeneity sources and analysis workflow.

Diagram 2: A taxonomy of data heterogeneity sources.

Modern biological research has witnessed an explosion in technologies capable of measuring diverse molecular layers, giving rise to various "omics" platforms. While single-omics approaches have provided valuable insights, they offer only a fragmented view of complex biological systems. The integration of multiple omics layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—is critical to understanding how individual parts of a biological system work together to produce emerging phenotypes. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and solutions for researchers navigating the challenges of multi-omics data integration, with a specific focus on managing data dimensionality and diversity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't I just analyze each omics layer separately and combine the results later? Analyzing omics layers separately and aggregating results in a post-hoc manner fails to capitalize on the statistical power of correlated data, particularly for detecting weak yet consistent signals across multiple molecular levels. True integration uses multivariate probability models that can strengthen statistical power and reveal interactions between different molecular levels that would be missed in separate analyses [18].

2. What is the most significant technical challenge in multi-omics integration? The primary challenge is managing the high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and different statistical distributions of multi-omics datasets. Each omics type has unique noise profiles, batch effects, and measurement errors that complicate harmonization. Additionally, the sheer volume of data makes meaningful interpretation difficult without sophisticated computational approaches [19] [7].

3. How do I handle missing data in multi-omics datasets? Parallel omics datasets can help implement procedures to infer missing data through statistical inference. Since different omics data from the same biological sample are expected to be correlated, observations in one platform can help predict missing values in another. Advanced computational methods, including deep generative models like variational autoencoders (VAEs), have been developed for data imputation and augmentation [19] [18].

4. What is the difference between "vertical" and "diagonal" integration? Vertical integration refers to combining matched multi-omics data generated from the same set of samples, keeping the biological context consistent. Diagonal integration (sometimes called horizontal integration) combines omics data from different, unpaired samples, requiring more complex computational analyses [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Data Generation and Quality Control

Problem: Low cDNA yield in single-cell RNA-seq experiments

- Solution:

- Always include positive control samples with RNA input mass similar to your experimental samples (e.g., 1-10 pg for single cells) [20]

- Ensure cells are suspended in appropriate EDTA-, Mg2+- and Ca2+-free buffers to avoid interference with reverse transcription [20]

- Process samples immediately after collection or snap-freeze at -80°C to minimize RNA degradation [20]

- Practice good RNA-seq techniques: use clean lab coats, sleeve covers, gloves, and separate pre- and post-PCR workspaces [20]

Problem: High background in negative controls

- Solution:

- Use a strong magnetic device during bead cleanup steps and allow beads to fully separate before removing supernatant [20]

- Follow protocol recommendations precisely for drying and hydration times after ethanol washes [20]

- Ensure all plasticware is RNase-, DNase-free and has low RNA- and DNA-binding properties [20]

Computational Integration Challenges

Problem: Choosing the right integration method for my data

- Solution: Select an integration method based on your data characteristics and research question: Table: Multi-Omics Integration Method Selection Guide

| Method | Approach | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA [7] [21] | Unsupervised factorization using Bayesian framework | Identifying latent factors across data types | Captures shared and data-specific variation |

| DIABLO [19] [7] | Supervised integration using multiblock sPLS-DA | Biomarker discovery with known phenotypes | Uses phenotype labels for feature selection |

| SNF [7] [21] | Network fusion of sample similarities | Clustering based on multiple data views | Constructs fused patient similarity networks |

| MCIA [7] [21] | Multiple co-inertia analysis | Joint analysis of high-dimensional data | Effective across multiple contexts |

| intNMF [19] [21] | Non-negative matrix factorization | Sample clustering tasks | Performs well in retrieving ground-truth clusters |

Problem: Managing different sampling frequencies across omics layers

- Solution: Implement a realistic hierarchy of testing that accounts for the different temporal dynamics of omics layers. The genome provides a static foundation, while the transcriptome is highly dynamic and may require more frequent assessment. Proteomics generally requires lower testing frequency due to protein stability, while metabolomics offers real-time perspectives on metabolic activities [3].

Data Interpretation Challenges

Problem: Translating integration results into biological insights

- Solution:

- Use pathway and network analyses to contextualize results [7]

- Apply functional enrichment analysis using gene ontology annotations and pathway databases [22]

- Integrate with existing biological network information (protein-protein interactions, regulatory networks) [18]

- Exercise caution in interpretation and validate findings with independent methods [7]

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Studies

Protocol 1: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Data Analysis Workflow

- Data Understanding: Familiarize yourself with dataset structure, experimental design, and sequencing technology [22]

- Preprocessing and QC:

- Read Alignment and Quantification:

- Normalization and Batch Correction:

- Downstream Analysis:

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Dimensionality Reduction Workflow

- Data Preparation: Ensure samples are matched across omics datasets where required [21]

- Method Selection: Choose jDR method based on data structure and research goals (refer to Table above) [21]

- Joint Decomposition: Decompose omics matrices into shared weight matrices and factor matrices [21]

- Downstream Analysis:

Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

Multi-Omics Integration Concepts

Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Platform [23] | Single-cell partitioning using droplet microfluidics | Widely used for high-throughput scRNA-seq |

| BD Rhapsody System [23] [22] | Single-cell analysis using microwell technology | Suitable for limited clinical samples; enables multimodal capture |

| SMART-Seq Kits [20] | Single-cell RNA-seq with oligo-dT and random priming | Offer both oligo-dT and random priming solutions |

| NanoString CosMx [23] | Imaging-based spatial transcriptomics | Uses smFISH-based method for spatial profiling |

| Vizgen MERSCOPE [23] | Spatial transcriptomics platform | MERFISH-based method for spatial resolution |

| Mass Spectrometry [3] [23] | Proteomic and metabolomic profiling | Techniques include MALDI, SIMS, LAESI for spatial metabolomics |

Advanced Integration Considerations

Handling Data Heterogeneity

Multi-omics datasets present significant heterogeneity in data structures, distributions, and noise profiles. Effective integration requires:

- Tailored preprocessing pipelines for each data type [7]

- Application of batch correction algorithms to address technical variations [22] [19]

- Use of normalization methods appropriate for each data modality [22]

Temporal Dynamics in Multi-Omics Sampling

Different omics layers require different sampling frequencies due to their varying temporal dynamics [3]:

- Genome: Static foundation, single sampling typically sufficient

- Transcriptome: Highly dynamic, may require frequent assessment

- Proteome: Generally stable, lower testing frequency needed

- Metabolome: Rapid changes, may require real-time monitoring

Statistical Power in Multi-Omics Studies

Integrative omics provides opportunities for enhanced statistical analysis [18]:

- Joint hypothesis testing using multivariate statistics

- Improved false discovery rate estimation through correlated testing

- Stronger statistical power for detecting consistent signals across omics layers

- Differentiation of regulation mechanisms across molecular levels

AI and Computational Strategies for Multi-Omics Data Integration

The integration of multi-omics data is a critical step in systems biology, enabling researchers to build a comprehensive molecular profile of health and disease by combining complementary biological layers such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [24] [25]. The core challenge lies in the inherent dimensionality and diversity of these datasets—each omics layer has different statistical distributions, scales, and numbers of features, all generated from the same set of biological samples [25] [7]. To manage this complexity, the field has standardized around three primary computational fusion strategies: Early, Intermediate, and Late Integration [24] [26] [27]. The strategic choice among these paradigms determines how effectively relationships across omics layers are captured and has a direct impact on the success of downstream analyses like biomarker discovery, disease subtyping, and patient stratification [28].

Core Integration Strategies: A Comparative Framework

The following table summarizes the defining characteristics, advantages, and challenges of the three primary integration strategies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenates raw or pre-processed features from all omics into a single matrix before analysis [24] [27]. | Simple to implement; allows models to learn directly from all data sources and capture complex, non-linear interactions between features from different omics [26] [27]. | High risk of overfitting due to the "curse of dimensionality"; requires careful handling of heterogeneous data types and scales; model can be dominated by the largest dataset [25] [27]. |

| Intermediate Integration | Transforms original datasets into a shared latent space or joint representation that captures the underlying common structure [24] [26]. | Effectively reduces data dimensionality; mitigates noise; reveals shared biological factors driving variation across omics; often achieves a balance between flexibility and performance [24] [25]. | The latent space can be mathematically abstract and biologically difficult to interpret; requires sophisticated methods to ensure the learned factors are meaningful [7]. |

| Late Integration | Analyzes each omics dataset independently and combines the results or decisions at the final step (e.g., averaging prediction scores) [24] [27]. | Leverages modality-specific models; avoids issues of data scale mis-match; highly modular and flexible, allowing for the use of best-practice pipelines per omics type [25] [27]. | Fails to model inter-omics interactions; may miss subtle, cross-modal biological signals; final performance is limited by the weakest individual model [24] [26]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for these three primary strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My integrated model is overfitting. Which strategy should I re-evaluate first?

A: Overfitting is most commonly associated with Early Integration due to the extremely high dimensionality of the concatenated feature matrix, where the number of variables (p) vastly exceeds the number of samples (n) [25]. To troubleshoot:

- Immediate Action: Switch to an Intermediate or Late Integration strategy. Intermediate methods like MOFA or autoencoders are specifically designed to reduce dimensionality and learn a lower-dimensional, more robust latent representation [25] [7].

- Alternative Action: If using Early Integration is necessary, implement aggressive feature selection (e.g., using DIABLO for supervised selection) or strong regularization within your model to penalize complexity [7].

- Best Practice: Always use cross-validation to tune hyperparameters and evaluate performance on a held-out test set.

Q2: How do I handle missing an entire omics dataset for some samples?

A: This is a common scenario in real-world studies. The best approach depends on your chosen integration strategy:

- For Late Integration: This is the most robust approach, as it trains models per omic and only requires the available modalities for each sample during prediction [26].

- For Intermediate Integration: Use methods that can handle missingness natively. Some advanced deep learning models, particularly generative approaches like variational autoencoders (VAEs), can impute missing modalities or learn from incomplete samples [26].

- To Avoid: Early Integration typically requires a complete set of data for all samples, so it is the least suitable for this problem. Listwise deletion of samples with missing omics can drastically reduce your sample size and introduce bias [25].

Q3: The results from my integration are biologically uninterpretable. What can I do?

A: Interpretability is a key challenge, especially with complex models.

- If using Intermediate Integration: The latent factors can be abstract. Use tools like MOFA+, which provides output detailing the variance explained by each factor in each omics dataset and identifies the top features loading onto each factor, allowing for biological annotation [7] [29].

- Strategy Switch: Consider a supervised Late Integration approach. Analyzing each omics layer separately can yield more transparent, modality-specific biomarkers, which can then be integrated biologically using pathway analysis [24].

- Leverage Prior Knowledge: Employ Hierarchical Integration strategies that use known regulatory relationships between omics layers (e.g., central dogma) to constrain the model, making the results more grounded in biology [24] [30].

Q4: My omics data are on vastly different scales. How do I pre-process for integration?

A: Data heterogeneity is a fundamental challenge.

- Mandatory Step: Apply omics-specific pre-processing and normalization to each dataset individually before any integration attempt. This includes scaling, transformation, and batch effect correction [25] [7].

- For Early Integration: After individual normalization, apply global scaling (e.g., Z-score normalization) across the entire concatenated dataset to ensure no single omics dominates due to its native scale [25].

- For Intermediate/Late Integration: Dataset-specific normalization is often sufficient, as these methods are designed to handle the distinct nature of each block. For example, MOFA is built to handle different data likelihoods (Gaussian, Bernoulli) for different data types [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Resources for Multi-Omics Data Integration

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Project Reference Materials [30] | Reference Materials | Provides matched DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolite standards from cell lines. Serves as a ground truth for quality control and benchmarking of integration methods. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [31] | Data Repository | A widely used public resource containing matched, clinically annotated multi-omics data for thousands of cancer patients, enabling method development and validation. |

| MOFA+ [7] [29] | Computational Tool | A powerful tool for unsupervised Intermediate Integration. It decomposes multiple omics datasets into a small number of latent factors that capture the major sources of biological and technical variation. |

| DIABLO [7] | Computational Tool | A supervised method for Intermediate Integration. It identifies a set of correlated features across multiple omics datasets that are predictive of a phenotype of interest (e.g., disease state), ideal for biomarker discovery. |

| Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) [7] | Computational Tool | A network-based method that constructs and fuses sample-similarity networks from each omics layer, effectively performing a form of Intermediate Integration for tasks like clustering and subtyping. |

| Seurat v4/v5 [29] | Computational Tool | A comprehensive toolkit, widely used for single-cell multi-omics data. It performs matched (vertical) integration using a weighted nearest-neighbor approach to anchor different modalities from the same cell. |

| GLUE (Graph-Linked Unified Embedding) [29] | Computational Tool | A deep learning-based tool for unmatched (diagonal) integration. It uses a graph-linked variational autoencoder and prior biological knowledge to align cells from different omics modalities. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between PCA, MOFA+, and MCIA in multi-omics integration? A1: PCA, MOFA+, and MCIA are suited for different multi-omics integration scenarios. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a single-omics technique that reduces data dimensionality by finding directions of maximum variance. It is unsupervised and not designed for integrating multiple data types. Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA+) is a generalization of PCA for multiple omics datasets. It uses a factor analysis model to infer latent factors that capture the principal sources of variation across different omics modalities in an unsupervised way [32]. Multiple Co-Inertia Analysis (MCIA) is another multi-omics method that projects different datasets into a common subspace by maximizing the variance explained in each dataset and the covariance between them [21] [33]. Unlike MOFA+, which learns a single set of shared factors, MCIA derives omics-specific factors that are correlated across data types [21].

Q2: When should I choose MOFA+ over MCIA for my multi-omics study? A2: The choice depends on your biological question and data structure. MOFA+ is particularly powerful for disentangling the heterogeneity of a high-dimensional multi-omics data set into a small number of latent factors that capture global sources of variation, both technical and biological [32] [34]. It is also robust to missing data and can handle datasets where not all omics are profiled on all samples [21] [32]. MCIA offers effective behavior across many contexts and is strong in visualizing relationships between samples and variables from multiple omics datasets simultaneously [21]. A comprehensive benchmark study noted that while intNMF performed best in clustering tasks, MCIA was a consistently strong performer [21].

Q3: How do I decide on the number of factors (for MOFA+) or components (for PCA/MCIA) to use? A3: For PCA, the number of components is often chosen based on the proportion of variance explained (e.g., using a scree plot). For MOFA+, the model can automatically learn the number of factors, but this can also be guided by the user. As a general rule, if the goal is to capture major sources of variability, use a small number of factors (K ≤ 10). If the goal is to capture smaller sources of variation for tasks like imputation, use a larger number (K > 25) [32]. The model's convergence and the variance explained per factor are key indicators. For MCIA and other methods, the number of components can be chosen via cross-validation or by evaluating the stability of the results.

Q4: What are the common data preprocessing steps before applying these dimension reduction techniques? A4: Proper preprocessing is critical for successful integration [33] [30].

- Normalization: Remove technical sources of variability before fitting the model. For count-based data (e.g., RNA-seq), this includes size factor normalization and variance stabilization [32].

- Scaling: Different omics layers operate on vastly different scales. Proper normalization ensures no single data type dominates the integrative analysis [35].

- Batch Effect Correction: Use tools like ComBat to remove systematic non-biological variation [35].

- Handling Missing Data: Some methods, like MOFA+, can handle missing values effectively by assuming they are "missing at random" [21] [34]. For others, features with excessive missingness may need to be removed.

Q5: My MOFA+ model identifies a strong Factor 1. How do I interpret what it represents biologically? A5: Interpreting factors is a key step in MOFA+ analysis. Follow this semi-automated pipeline [32]:

- Visualization: Plot samples in the factor space (e.g., Factor 1 vs. Factor 2) and color them using known covariates (e.g., clinical information, batch).

- Correlation: Calculate correlations between the factor values and (clinical) covariates.

- Inspection of Loadings: Examine the loadings, which indicate feature importance. Identify the top-weighted genes, proteins, or other features for the factor.

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on the top-loaded features to see if they correspond to known biological pathways.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Model Fails to Converge or Yields Poor Integration (MOFA+ & MCIA)

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A single dominant factor captures technical noise. | Incorrect data normalization. | Re-normalize data to remove technical variability (e.g., regress out covariates). For RNA-seq, ensure proper variance stabilization [32]. |

| Factors do not separate samples by known biological groups. | Incorrect number of factors. | Increase the number of factors to capture smaller, more specific sources of variation [32]. |

| Model fails to learn from one or more omics assays. | Assay with too few features. | MOFA+ may struggle with assays containing very few features (<15). Consider omitting or combining such assays [34]. |

| Results are unstable or inconsistent. | Presence of strong batch effects. | Check for and correct for batch effects during the data preprocessing step before integration [35] [30]. |

Issue 2: Installation and Dependency Errors (MOFA+)

| Symptom | Error Message Example | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| R package fails to install. | ERROR: dependencies 'pcaMethods', 'MultiAssayExperiment' are not available |

Install the required dependencies from Bioconductor, not CRAN [32]. |

| Python dependencies not found. | ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'mofapy' |

Install the Python package via pip: pip install mofapy. Ensure the R reticulate package is pointing to the correct Python binary [32]. |

| General connectivity issues between R and Python. | AttributeError: 'module' object has no attribute 'core.entry_point' |

Restart R and reconfigure reticulate. Explicitly set the Python path: library(reticulate); use_python("YOUR_PYTHON_PATH", required=TRUE) [32]. |

Issue 3: Interpreting and Validating Results

| Challenge | Question | Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Interpretation | How do I know if my factors are biologically meaningful? | Systematically correlate factors with all available sample metadata. Use the loadings for gene set enrichment analysis to link factors to known pathways [32]. |

| Method Selection | How do I validate that I chose the right method for my data? | Benchmarking studies show that performance is context-dependent. Use built-in truth, if available (e.g., from a project like the Quartet Project), or evaluate based on your analysis goal: use intNMF for clustering, while MCIA is effective across many contexts [21] [30]. |

| Result Stability | Are my identified biomarkers robust? | Use the factors in a supervised model on a held-out test set to predict a clinical outcome. For MOFA+, the AUROC for predicting vaccine response was 0.616, demonstrating a measurable predictive value [34]. |

| Item | Function in Multi-Omics Analysis |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet Project) | Provides multi-omics ground truth with built-in biological relationships (e.g., family pedigree). Essential for quality assessment, benchmarking integration methods, and protocol standardization [30]. |

| Public Data Repositories (e.g., TCGA, GEO, CGGA) | Sources of publicly available multi-omics data for method testing, validation, and comparative analysis [36] [33]. |

| Benchmarking Suites (e.g., momix Jupyter notebook) | The code from the Nature Communications benchmark provides a reproducible framework to evaluate and compare jDR methods on your own data [21]. |

| Horizontal Integration Tools (e.g., ComBat) | Tools for integrating datasets from the same omics type across different batches or platforms, a critical preprocessing step before vertical (cross-omics) integration [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Benchmarking jDR Methods Using a Multi-Omics Dataset

Objective: To evaluate and select the optimal joint dimensionality reduction (jDR) method for a specific multi-omics dataset. Methodology: [21]

- Data Simulation & Ground Truth Retrieval: Generate simulated multi-omics datasets with known sample cluster structures. Apply each jDR method and evaluate its performance in retrieving the ground-truth clustering.

- Performance on Real Cancer Data: Use real multi-omics data (e.g., from TCGA). Assess the strengths of each method in predicting patient survival, associating with clinical annotations, and recapitulating known biological pathways.

- Single-Cell Data Classification: Evaluate the performance of methods in classifying samples from multi-omics single-cell data. Expected Outcome: A performance profile for each method (e.g., intNMF for clustering, MCIA as an all-rounder) to guide selection.

Protocol 2: Standard Workflow for MOFA+ Analysis

Objective: To perform an unsupervised integration of multi-omics data to identify latent factors and their drivers. Methodology: [32] [37]

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize and scale each omics dataset individually. Check and correct for batch effects.

- Model Training: Create a MOFA object and train the model. Monitor the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) for convergence.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Calculate the variance explained by each factor in each view.

- Visualize samples in the factor space.

- Correlate factors with known clinical covariates.

- Inspect the loadings to identify top features per factor.

- Perform gene set enrichment analysis on the loadings. Expected Outcome: A set of latent factors that represent the key sources of variation across the omics datasets, along with biological interpretations for the factors.

Core Concepts and Workflow Visualization

Multi-Omics Dimensionality Reduction Workflow

MOFA+ Model Decomposes Multi-Omics Data into Shared Latent Factors

Graph Neural Networks (GCNs) and Autoencoders

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My graph neural network model for multi-omics integration suffers from over-smoothing. What steps can I take to mitigate this?

Over-smoothing occurs when node features become indistinguishable after too many GNN layers. To address this:

- Use Attention Mechanisms: Integrate Graph Attention Networks (GATv2) to assign varying importance to neighboring nodes, preventing uniform feature averaging [38].

- Employ Residual Connections: Add skip connections between GNN layers to help preserve information from previous layers and improve gradient flow [38].

- Limit Network Depth: Consider using shallow GNN architectures, as many graph structures in bioinformatics can be effectively captured with 2-3 layers [39].

Q2: How can I handle highly sparse and noisy spatial multi-omics data during integration?

Sparsity and noise are common in technologies like spatial transcriptomics.

- Apply Contrastive Learning: Use a strategy that compares the original spatial graph with a corrupted graph (with shuffled features). This helps the model learn robust embeddings by maximizing mutual information between a spot and its local context, making it less sensitive to noise [39].

- Leverage Spatial Dependencies: Explicitly model spatial relationships by constructing graphs where spots are nodes connected based on spatial proximity. This allows information from neighboring spots to help denoise the data [40] [39].

- Utilize Regularization: Incorporate cosine similarity regularization between modality-specific embeddings to ensure they align in the latent space without overfitting to noise [39].

Q3: What strategies can ensure my model effectively integrates data from more than two omics modalities?

Many methods are designed for only two modalities, creating limitations.

- Seek Flexible Frameworks: Choose or develop models with architecture that can natively handle a variable number of input modalities. Methods like MEFISTO (factor analysis-based) are designed for three or more modalities, though performance should be validated [40].

- Avoid Fixed Fusion Designs: Steer clear of models with hard-coded dual-attention mechanisms or fusion blocks that require significant re-engineering for each new modality [40].

Q4: When integrating multi-omics data with a variational autoencoder (VAE), how can I prevent "posterior collapse"?

Posterior collapse happens when the powerful decoder ignores the latent embeddings from the encoder.

- Warm-up Schedule: Gradually increase the weight of the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence term in the loss function during training, forcing the encoder to use the latent space more effectively [41].

- Use Enhanced Architectures: Consider models like the Transformer Graph VAE (TGVAE), which combines the structural strengths of GNNs with the sequence modeling power of Transformers, and includes specific mechanisms to counter posterior collapse [41].

- Adjust Model Capacity: Temporarily reduce the decoder's capacity or use a weaker decoder to encourage the encoder to produce more informative latent variables [42].

Q5: How can I incorporate prior biological knowledge into a GNN to improve interpretability?

Using known biological networks can guide the model and make results more explainable.

- Use Knowledge Graphs as Topology: Instead of building graphs based only on patient similarity, model the relationships between biological features (e.g., genes, proteins) directly. Use established interaction databases (e.g., Pathway Commons) to define the graph's edges. This allows the GNN's message passing to occur over known biological pathways, and explainability methods like integrated gradients can then highlight important features within these networks [43].

Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Multi-Omics Integration

The following table summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of several state-of-the-art models as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Multi-Omics Integration

| Model Name | Model Type | Key Innovation | Reported Accuracy/Metric | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoRE-GNN [38] | Heterogeneous Graph Autoencoder | Dynamically constructs relational graphs from data without predefined biological priors. | Outperformed existing methods on six datasets, especially with strong inter-modality correlations. | Single-cell multi-omics integration; cross-modal prediction. |

| GNNRAI [43] | Supervised Explainable GNN | Integrates multi-omics data with prior knowledge graphs (e.g., biological pathways). | Increased validation accuracy by 2.2% on average over MOGONET in AD classification. | Supervised analysis; biomarker identification with explainable results. |

| optSAE + HSAPSO [44] | Optimized Stacked Autoencoder | Integrates a stacked autoencoder with a hierarchically self-adaptive PSO for hyperparameter tuning. | 95.52% accuracy in drug classification tasks. | Drug classification and target identification. |

| SMOPCA [40] | Spatial Multi-Omics PCA | A factor analysis model that uses multivariate normal priors to explicitly capture spatial dependencies. | Consistently delivered superior or comparable results to best deep learning approaches on multiple datasets. | Spatial multi-omics data integration and dimension reduction. |

| SpaMI [39] | Graph Autoencoder with Contrastive Learning | Uses contrastive learning and an attention mechanism to integrate and denoise spatial multi-omics data. | Demonstrated superior performance in identifying spatial domains and data denoising on real datasets. | Integrating and denoising spatial multi-omics data from the same tissue slice. |

| ScafVAE [42] | Scaffold-Aware Graph VAE | A molecular generation model using bond scaffold-based generation and perplexity-inspired fragmentation. | Outperformed tested graph models on the GuacaMol benchmark; high accuracy in predicting ADMET properties. | De novo multi-objective drug design and molecular property prediction. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Dynamic Graph Construction and Integration with MoRE-GNN

This protocol outlines the process for constructing relational graphs from multi-omics data for integration with a Graph Autoencoder [38].

- Input Data Preparation: For each modality ( m \in M ) (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics), organize the data into a feature matrix ( \mathbf{X}m \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times dm} ), where ( N ) is the number of cells and ( d_m ) is the number of features for that modality. Ensure rows (cells) are aligned across all matrices.

- Similarity Matrix Calculation: For each modality ( m ), compute a cell-to-cell similarity matrix ( Sm ) using cosine similarity: ( Sm = \frac{\mathbf{x}m \cdot \mathbf{x}m}{\|\mathbf{x}m\|{2}^{2}} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N} ).

- Relational Graph Construction: For each similarity matrix ( Sm ), construct a sparse adjacency matrix ( \mathcal{A}m ) by retaining only the top ( K ) connections for each cell (row). This creates a k-nearest neighbor graph for each modality.

- Node Feature Concatenation: Create a unified node feature matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) by concatenating the feature matrices from all modalities: ( \mathbf{X} = \| {m \in M} \mathbf{x}m ).

- Model Training with Mini-Batches: a. Subgraph Sampling: To ensure computational scalability, sample a mini-batch of ( B ) "seed" cells. b. For each seed cell, include its ( N1 ) immediate neighbors from the relational graphs, and then ( N2 ) neighbors for each of those primary neighbors. This creates a local subgraph that approximates the global structure. c. The heterogeneous graph autoencoder (composed of GCN and GATv2 layers) is trained on these subgraphs in a contrastive fashion, where decoders learn to predict positive and negative edge links [38].

Protocol 2: Supervised Integration with Biological Priors using GNNRAI

This protocol describes how to integrate multi-omics data with prior biological knowledge for supervised prediction tasks [43].

- Prior Knowledge Graph Definition: For the disease or biological process of interest (e.g., Alzheimer's), define a set of biological domains (Biodomains). For each domain, build a knowledge graph where nodes are genes/proteins and edges represent known interactions (e.g., from the Pathway Commons database).

- Omics Data Graph Formation: For each patient sample and each available omics modality (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics), create a separate graph for each Biodomain.

- The graph structure (nodes and edges) is defined by the Biodomain's knowledge graph.

- Node features are populated with the patient's normalized expression or abundance measurements for the corresponding genes/proteins in that domain.

- Modality-Specific Embedding: Process each modality's set of graphs through dedicated GNN-based feature extractors. Each GNN performs message passing over the prior knowledge graph, incorporating the patient's specific omics data to produce a low-dimensional graph embedding for each Biodomain and modality.

- Cross-Modal Alignment and Integration: a. Alignment: Apply a regularization loss to align the low-dimensional embeddings from different modalities, enforcing shared patterns. b. Integration: Feed the aligned, modality-specific embeddings into a Set Transformer to learn a unified, integrated representation for the patient.

- Supervised Training and Explainability: a. Use the integrated representation to predict the target phenotype (e.g., disease status). b. After training, apply explainability methods like Integrated Gradients to the model's predictions. This attributes importance to the input nodes (genes/proteins), identifying potential biomarkers within the context of the prior biological knowledge [43].

Model Architecture and Data Flow Visualizations

Diagram 1: MoRE-GNN Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

Multi-Omics Graph Construction and Learning

Diagram 2: GNNRAI Architecture for Supervised Integration

Supervised Integration with Biological Knowledge Graphs

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Data Resources for Multi-Omics AI Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Commons [43] | Biological Database | A repository of publicly available pathway and interaction data from multiple species. | Used to construct prior knowledge graphs that define the topology for GNN models like GNNRAI. |

| DrugBank [44] | Pharmaceutical Database | A comprehensive database containing drug and drug target information. | Serves as a key source of validated data for training and benchmarking drug classification models (e.g., optSAE+HSAPSO). |

| CITE-seq Data [40] [39] | Experimental Technology / Data Type | A single-cell multi-omics technology that simultaneously measures transcriptome and surface protein data. | A common input dataset for developing and testing integration methods like SMOPCA and SpaMI. |

| UMAP [38] [45] | Dimensionality Reduction Tool | A non-linear algorithm for dimension reduction and visualization of high-dimensional data. | Used for projecting final learned latent representations (e.g., from MoRE-GNN) into 2D for visualization and clustering. |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [38] [39] | Neural Network Layer | A fundamental GNN layer that operates by aggregating features from a node's neighbors. | Forms the base embedding block in encoders for many models, including MoRE-GNN and SpaMI. |

| Graph Attention Network (GATv2) [38] | Neural Network Layer | An advanced GNN layer that uses attention mechanisms to assign different weights to neighboring nodes. | Used in models like MoRE-GNN to dynamically capture the importance of different cellular relationships. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [44] | Optimization Algorithm | An evolutionary algorithm that optimizes a problem by iteratively improving a population of candidate solutions. | The core of the HSAPSO algorithm used to efficiently tune the hyperparameters of the stacked autoencoder in optSAE. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I resolve color contrast issues when mapping gene expression data onto pathway nodes?

A1: Implement automated color selection algorithms to ensure readability. Use the prismatic::best_contrast() function in R or similar libraries to automatically select text colors that contrast sufficiently with node background colors [46]. For categorical data, ensure a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio between adjacent colors as per WCAG accessibility guidelines [47]. Test your color mappings against both light and dark backgrounds to ensure universal readability.

Q2: What should I do when my network visualization becomes cluttered with too many overlapping elements?

A2: Apply strategic edge styling and layout techniques. Use curved edges instead of straight lines to reduce overlap in bidirectional connections [48]. Implement edge bundling techniques to group similar connections, and adjust opacity to manage density in highly-connected regions [49]. Consider using compound nodes to hierarchically group related entities, and utilize interactive filtering to focus on specific pathway sections [50].

Q3: How can I maintain consistent visual encoding when switching between different pathway views?

A3: Create standardized style templates with predefined color palettes. Tools like PARTNER CPRM offer 16 professionally designed color palettes that can be applied consistently across multiple network maps [51]. Establish mapping rules that persist when switching views, such as maintaining the same color for specific node types (e.g., enzymes, metabolites, genes) regardless of the current pathway context.

Q4: What is the best approach for coloring edges in mixed interaction networks?

A4: Choose edge coloring strategies based on biological meaning. Options include coloring by source node, target node, or using mixed colors representing both endpoints [48]. For protein-protein interaction networks, use solid edges; for protein-DNA interactions, consider dashed edges as implemented in tools like Cytoscape's sample styles [49]. Ensure edge drawing order is randomized to prevent visual bias when edges overlap.

Q5: How can I ensure my pathway visualizations remain accessible to colorblind users?

A5: Utilize colorblind-friendly palettes and multiple encoding channels. Beyond meeting 3:1 contrast ratios, combine color with shape, pattern, or texture distinctions [47]. Tools like Cytoscape provide bypass options to manually adjust colors for specific nodes when automated mappings prove problematic [52] [49]. Test visualizations using colorblind simulation tools to identify and resolve accessibility issues.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Label Readability Against Colored Node Backgrounds

Solution: Implement dynamic text color selection based on background luminance.

Protocol:

- Calculate background color luminance using the formula:

L = 0.2126 * R + 0.7152 * G + 0.0722 * B - Set text color to white if luminance < 50, otherwise use black [46]

- For critical applications, use the APCA (Advanced Perceptual Contrast Algorithm) for more precise contrast calculations [53]

- Apply these rules consistently across all node types and pathway views

Problem: Inconsistent Visual Representation Across Multi-Omic Data Layers

Solution: Establish a unified visual encoding system across data types.

Protocol:

- Create a central style registry defining color mappings for each data type

- Use Cytoscape's style system to define default values, mappings, and bypass options [49]

- For genomic data, use blue-yellow gradients (e.g.,

viridis::magmain R) [46] - For proteomic data, consider red-green gradients while providing alternative encodings for colorblind users

- Maintain consistent node shapes for entity types (e.g., circles for genes, rectangles for proteins)

Problem: Network Layout Obscures Important Pathway Topology

Solution: Apply pathway-specific layout algorithms rather than general graph layout.

Protocol:

- Use tools like ChiBE that implement specialized pathway layout algorithms [50]

- For biochemical pathways, use directed flows from top to bottom or left to right

- For signal transduction pathways, use emphasis on membrane localization and compartmentalization

- Implement compound graph structures to represent molecular complexes and cellular compartments [50]

- Use nested network visualization for hierarchical pathway data

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Biochemical Pathway Mapping and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape | Network visualization and analysis | Multi-omics data integration, pathway enrichment analysis, network biology |

| ChiBE | BioPAX pathway visualization | Interactive pathway exploration, Pathway Commons querying, compound graph visualization |

| PARTNER CPRM | Community partnership mapping | Collaborative network management, stakeholder engagement tracking, ecosystem mapping |

| PATIKAmad | Microarray data contextualization | Gene expression visualization in pathway context, molecular profile analysis [50] |

| Paxtools | BioPAX data manipulation | Reading, writing, and merging BioPAX format files, pathway data integration [50] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Omic Data Mapping onto Reference Pathways

Objective: Visualize integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data on shared biochemical pathways.

Materials:

- Reference pathways in BioPAX format

- Multi-omics data matrices (genomic variants, expression values, protein abundances)

- ChiBE visualization tool [50]

- Cytoscape with appropriate plugins [49]

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Convert all omics data to standardized format (Z-scores or fold-changes)

- Pathway Loading: Import BioPAX files into ChiBE using Paxtools library [50]

- Data Mapping: Overlay expression data using color coding on pathway nodes

- Visual Encoding:

- Set node color gradients based on expression values (e.g., blue-white-red for downregulated-normal-upregulated)

- Map node size to protein abundance measurements

- Use border colors or patterns to indicate genomic variants

- Layout Optimization: Apply pathway-specific layout to emphasize flow and connectivity

- Export: Save resulting pathway views as high-resolution images or interactive web formats

Protocol 2: Automated Accessibility Testing for Network Visualizations

Objective: Ensure pathway visualizations meet accessibility standards for all users.

Materials:

- Network visualization files (Cytoscape session, SVG, or other formats)

- Color contrast analysis tools (WCAG contrast checkers, APCA implementations)

- prismatic R package or similar contrast calculation libraries [46]

Methodology:

- Contrast Measurement: Calculate contrast ratios between all adjacent visual elements

- Color Vision Deficiency Testing: Simulate visualization appearance for different colorblindness types

- Text Legibility Verification: Ensure text labels maintain ≥3:1 contrast ratio against backgrounds [47]

- Element Distinctness Testing: Verify all node types, edge types, and labels are distinguishable without color

- Interactive Testing: Check focus indicators and interactive elements meet 3:1 contrast requirements [47]

- Remediation: Apply corrections through style modifications or alternative encodings

Visualization Workflows

Pathway Integration and Mapping Workflow

Color Contrast Validation Logic

Real-World Applications in Drug Discovery and Precision Oncology

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary value of Real-World Evidence (RWE) in precision oncology? RWE is particularly valuable for studying rare cancer populations where traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are challenging. It provides clinical, regulatory, and development decision-making support by expanding the evidence base for rare molecular subtypes, assessing real-world adverse events, and evaluating pan-tumor effectiveness. RWE can also serve as a contemporary control arm in single-arm trials [54]. For precision oncology medicines that target rare genomic alterations, RWE is often the most compelling data source available when RCTs are not feasible [55].

Q2: What are the key data quality challenges when working with multi-omics data? The main challenges include data heterogeneity, where each omics layer has different measurement techniques, data types, scales, and noise levels [56]. High dimensionality can lead to overfitting in statistical models, and biological variability among samples introduces additional noise. Furthermore, differences in data preprocessing, normalization requirements, and the potential for batch effects significantly complicate integration [8] [56].