Taming the Beast: A Comprehensive Guide to Handling Batch Effects in Multi-Omics Data Integration

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for understanding, correcting, and validating batch effects in multi-omics studies.

Taming the Beast: A Comprehensive Guide to Handling Batch Effects in Multi-Omics Data Integration

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for understanding, correcting, and validating batch effects in multi-omics studies. Covering foundational concepts, methodological applications, troubleshooting of common pitfalls, and rigorous validation strategies, it synthesizes current best practices to ensure robust data integration, accelerate biomarker discovery, and advance the development of reliable precision medicine approaches.

Understanding Batch Effects: The Hidden Threat to Multi-Omics Reproducibility

What Are Batch Effects? Defining Technical Variation in Omics Data

Batch effects are technical variations in high-throughput data that are unrelated to the biological factors of interest in a study. They are introduced due to variations in experimental conditions over time, using data from different labs or machines, or employing different analysis pipelines [1] [2]. In multi-omics data integration, where different types of data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) are combined, batch effects are more complex because each data type is measured on different platforms with different distributions and scales [1] [3].

FAQs on Batch Effects

Q1: What are the real-world consequences of uncorrected batch effects? Uncorrected batch effects can lead to severe consequences, including misleading scientific conclusions and significant economic losses. In one clinical trial, a change in RNA-extraction solution caused a shift in gene-based risk calculations, leading to incorrect treatment classifications for 162 patients, 28 of whom received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy [1] [3]. Batch effects are also a paramount factor contributing to the "reproducibility crisis" in science, potentially resulting in retracted articles and invalidated research findings [1] [3].

Q2: At which stages of my experiment can batch effects be introduced? Batch effects can emerge at virtually every step of a high-throughput study [1]:

- Study Design: Flawed or confounded design, such as non-randomized sample collection or selection based on specific characteristics (age, gender), can introduce systematic biases.

- Sample Preparation & Storage: Variations in protocols, storage temperature, duration, and freeze-thaw cycles can cause significant changes in analytes.

- Data Generation: Differences in reagent lots, personnel, laboratory conditions, instruments, and time of day when the experiment is conducted are common sources [2].

Q3: How can I detect batch effects in my dataset? Common techniques to visualize and detect batch effects include:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Scatterplots can reveal if samples cluster more strongly by batch than by biological group [4] [5].

- t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) / UMAP: These clustering plots can show if technical factors, rather than the phenotype under investigation, are driving sample grouping [6] [4].

- k-Nearest Neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET): This method quantitatively measures how well batches are mixed at a local level [7].

Q4: What is the difference between a balanced and a confounded study design? The distinction is critical for choosing a correction strategy [6] [4]:

- Balanced Design: Samples from all biological groups are evenly distributed across all batches. In this ideal scenario, batch effects can often be "averaged out" or corrected by many algorithms.

- Confounded Design: Biological groups are completely or highly correlated with batch groups (e.g., all control samples are processed in Batch 1, and all disease samples in Batch 2). In this case, it is nearly impossible to distinguish true biological differences from technical variations, and most standard correction methods fail.

The diagrams below illustrate these two fundamental study design scenarios.

Q5: What are the main strategies for correcting batch effects? Correction methods can be broadly categorized as follows [6] [5]:

- Ratio-Based Scaling (Reference-Based): This highly effective method scales the absolute feature values of study samples relative to those of concurrently profiled reference material(s) in the same batch [6].

- Statistical Modeling: Algorithms like ComBat (using empirical Bayes frameworks) and limma (using linear models) model and remove batch variances while preserving biological signals [2] [6].

- Matching-Based Methods: Methods like Harmony and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) identify shared biological states across batches to align them [2] [8].

- Advanced/Machine Learning Methods: Newer approaches use deep learning autoencoders, Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forest to model complex, nonlinear batch trends [7] [5].

The table below summarizes some commonly used batch effect correction algorithms (BECAs).

| Algorithm/Method | Primary Strategy | Key Advantage | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based (e.g., Ratio-G) [6] | Scaling relative to a reference material | Highly effective even in confounded designs | Multi-omics (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) |

| ComBat [2] [6] | Empirical Bayes adjustment | Easy to implement, widely used and tested | Bulk transcriptomics, microarray |

| Harmony [6] [8] | PCA-based integration | Effective for single-cell data; removes batch effects while preserving fine-grained structure | Single-cell RNA-seq |

| Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) [2] [8] | Matching cell populations across batches | Identifies overlapping biological states for alignment | Single-cell RNA-seq |

| SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis) [6] | Estimation of hidden factors | Models unknown sources of variation | Bulk transcriptomics |

| SVR (in metaX) [5] | Support Vector Regression on QC samples | Flexible modeling of signal drift over time | Metabolomics |

| BERMUDA [7] | Deep transfer learning | Discovers hidden cellular subtypes during correction | Single-cell RNA-seq |

Q6: How do I choose the right correction method and validate its performance? Selection depends on your data type and experimental design [7]:

- For bulk omics data (microarray, RNA-seq), ComBat, limma, and SVA are standard starting points.

- For single-cell RNA-seq data, use methods designed for its high noise and sparsity, like Harmony, MNN, or deep learning approaches (e.g., scVI).

- For metabolomics/proteomics, where instrumental drift is common, QC-sample-based methods (SVR, RSC) or ratio-based methods are often preferred [5].

- For confounded designs or multi-omics integration, the ratio-based method using reference materials is highly recommended [6].

To validate performance, use the same visualization techniques for detection (PCA, t-SNE) to confirm that batch clustering is reduced and biological groups are preserved. Quantitatively, you can assess [6] [5]:

- Replicate Correlation: Check if technical replicates are more similar after correction.

- Differential Analysis Consistency: See if known true positive findings remain consistent.

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Measure the improvement in biological signal separation.

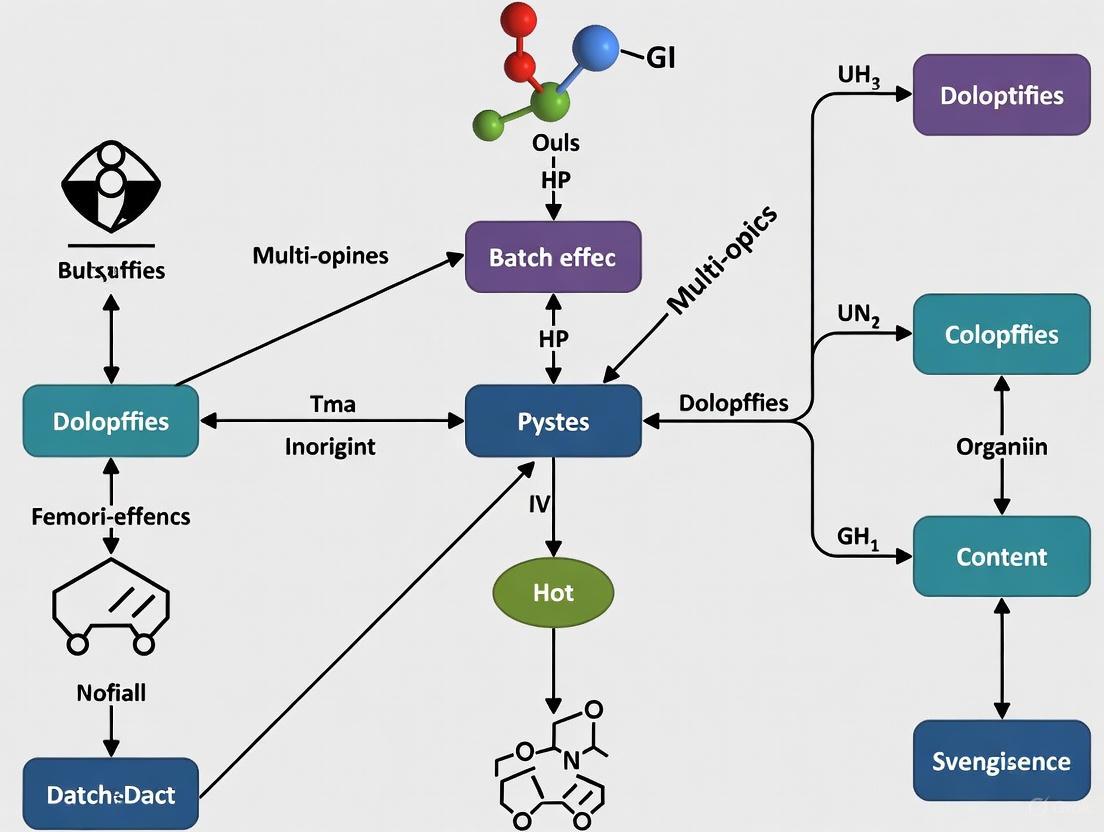

The following diagram outlines a general workflow for diagnosing and correcting batch effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Batch Effect Management

Proactively managing batch effects requires specific materials and strategic planning. The following table lists key reagents and resources used in featured experiments.

| Item/Reagent | Function in Batch Effect Management |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (RMs) [6] | Physically defined materials (e.g., from cell lines) profiled alongside study samples in every batch to enable ratio-based correction. |

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Samples [5] | A mixture of all or a subset of study samples, inserted at regular intervals during a batch run to monitor and correct for instrumental drift. |

| Internal Standards (IS) [5] | Known concentrations of isotopically labeled compounds added to each sample to correct for technical variation per metabolite (common in metabolomics). |

| Multiplexing Reference Samples [8] | Reference samples (e.g., from a defined cell line) included in multiple sequencing runs or batches to serve as an anchor for cross-batch alignment. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Effective Batch Effect Correction

Protocol 1: Implementing Ratio-Based Correction with Reference Materials This protocol is highly effective for large-scale multi-omics studies, especially when batch and biological factors are confounded [6].

- Select and Characterize Reference Material(s): Choose well-characterized, stable reference materials (e.g., the Quartet reference materials derived from B-lymphoblastoid cell lines).

- Concurrent Profiling: In every experimental batch, profile the reference material(s) alongside your study samples using the exact same protocols and reagents.

- Calculate Ratios: For each feature (gene, protein, metabolite) in each study sample, transform the absolute measurement (Istudy) to a ratio relative to the reference material's measurement (Iref): Ratio = Istudy / Iref.

- Data Integration: Use the ratio-scaled data for all downstream integrative analyses, as these values are now normalized against the technical variation captured by the reference material.

Protocol 2: Using Pooled QC Samples for Drift Correction in Metabolomics This protocol uses machine learning to model and remove systematic drift within a batch [5].

- Create Pooled QC Sample: Prepare a QC sample by mixing equal aliquots from all study samples.

- Sequential Injection: Inject the pooled QC sample at regular intervals (e.g., after every 10 experimental samples) throughout the instrumental analysis batch.

- Model Drift: Use algorithms like Support Vector Regression (SVR) or Robust Spline Correction (RSC) (available in R packages like

metaXandstatTarget) to model the trend of each metabolite's signal in the QC samples over time. - Apply Correction: For each experimental sample, correct the feature values based on the drift model fitted from the neighboring QC samples.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

What are batch effects, and what causes them? Batch effects are non-biological variations in data caused by technical differences during the data generation process. These technical variations can arise from multiple sources, including different sequencing platforms, reagent lots, personnel, laboratory conditions, processing times, or equipment calibration [9] [10] [8]. In multi-omics studies, these effects are compounded as each data type (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) has its own unique sources of technical noise [11].

What is the difference between data normalization and batch effect correction? These processes address different technical issues. Normalization operates on the raw count matrix to mitigate variations caused by sequencing depth, library size, amplification bias, and gene length across cells. In contrast, batch effect correction specifically mitigates technical variations arising from different sequencing platforms, timing, reagents, or different conditions and laboratories [9].

FAQ: Detection & Diagnosis

How can I detect batch effects in my data? Several visualization and quantitative methods can help identify batch effects:

- Visualization Techniques:

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis): Plot your data using the top principal components. If samples or cells separate based on their batch group rather than their biological source, it indicates a batch effect [9] [12].

- t-SNE/UMAP Plots: Visualize cell groups and label them by batch number. In the presence of batch effects, cells from different batches tend to form separate clusters instead of mixing based on biological similarities [9] [12].

- Clustering: Construct heatmaps or dendrograms. If your data clusters by batch instead of by the experimental treatment or condition, it signals a batch effect [12] [4].

- Quantitative Metrics: Several metrics can quantify the extent of batch effects and the success of correction, including the k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET), adjusted rand index (ARI), and Principal Variation Component Analysis (PVCA) [9] [10].

What are the key signs that I have over-corrected my data? Over-correction occurs when batch effect removal also removes genuine biological signal. Key signs include:

- Distinct biological cell types are clustered together on a UMAP or t-SNE plot [12].

- A complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions [12].

- A significant portion of cluster-specific markers are genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) rather than canonical cell-type markers [9].

- The notable absence of expected cluster-specific markers or differential expression hits associated with pathways known to be active in your samples [9].

FAQ: Correction & Solutions

What are the most effective methods for batch effect correction? The "best" method can depend on your data type and experimental design. The following table summarizes high-performing methods across different domains based on recent benchmarks.

Table 1: Benchmarking of Batch Effect Correction Methods Across Data Types

| Method | Primary Data Type | Key Principle | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony [9] [13] | scRNA-seq, Image-based Profiling | Uses PCA and iterative clustering to maximize diversity and calculate a per-cell correction factor. | Consistently ranks among top methods; good balance of batch removal and biological conservation [13]. |

| Seurat (RPCA/CCA) [9] [13] | scRNA-seq | Uses Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) or Reciprocal PCA (RPCA) to find mutual nearest neighbors (MNNs) as "anchors" for integration. | Seurat RPCA is highly ranked, especially for heterogeneous datasets [13]. |

| Ratio-Based Method [14] | Bulk Multi-omics (Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics) | Scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to a concurrently profiled reference material in each batch. | Highly effective, especially when batch effects are confounded with biological factors [14]. |

| Scanorama [9] | scRNA-seq | Searches for MNNs in dimensionally reduced spaces, using a similarity-weighted approach for integration. | Performs well on complex, heterogeneous data [9]. |

| LIGER [9] | scRNA-seq | Employs integrative non-negative matrix factorization to factor data into batch-specific and shared factors. | Effective for data integration [9]. |

| ComBat [9] [13] | Bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq | Models batch effects as additive and multiplicative noise using a Bayesian framework. | A classic method; performance can be surpassed by newer algorithms [13]. |

How does my experimental design impact the ability to correct for batch effects? Experimental design is critical. The level of confounding between your biological groups and batch groups dictates the difficulty of correction.

- Balanced Design: Biological groups of interest (e.g., Case vs. Control) are evenly distributed across all batches. In this ideal scenario, many batch-effect correction algorithms (BECAs) can be effective because technical variation can be "averaged out" [14] [4].

- Confounded Design: Biological groups are completely separated by batch (e.g., all Case samples are in Batch 1, all Control in Batch 2). This is a worst-case scenario where it becomes nearly impossible to distinguish true biological differences from technical variations. In such cases, reference-material-based methods like the ratio-based approach are highly recommended [14] [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Detecting Batch Effects with PCA and UMAP

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for the initial qualitative assessment of batch effects in single-cell or bulk omics data.

- Input: A raw, normalized count matrix (cells/genes or samples/features) with associated metadata specifying batch IDs and biological groups.

- Software: R or Python with necessary libraries (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy, scikit-learn).

- Dimensionality Reduction (PCA):

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the normalized count matrix.

- Extract the top N principal components (PCs) that capture the majority of the variance in the dataset.

- Visualization:

- Generate a scatter plot of the data using the top two PCs (PC1 vs. PC2).

- Color the data points by Batch ID. A clear separation of data points based on color (batch) indicates a strong batch effect.

- Color the data points by Biological Condition. Compare this plot to the batch-colored plot. If the primary separation in the data is driven by batch and not biological condition, a batch effect is confirmed [9] [12].

- Non-Linear Visualization (UMAP):

- Using the top PCs as input, compute a UMAP embedding to visualize the data in two dimensions.

- Color the UMAP by Batch ID. The presence of distinct, batch-specific clusters, rather of a single blended cluster, indicates a batch effect [9] [12].

- Color the UMAP by Biological Condition. After successful batch correction, you should see clusters defined by biological condition, with cells from all batches mixed within each biological cluster.

The logical workflow for this diagnostic process is outlined below.

Protocol: Correcting Batch Effects Using a Reference-Material-Based Ratio Method

This protocol is highly effective for bulk multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics), particularly in confounded experimental designs [14].

- Input: Feature-level measurements (e.g., gene expression, protein abundance) from multiple batches. A key requirement is that one or more reference materials (e.g., a control sample or a standard reference) are profiled concurrently with the study samples in each batch.

- Software: Standard statistical software (R, Python).

- Experimental Setup:

- In every batch of your experiment, include aliquots from a common, well-characterized reference material. The Quartet Project reference materials are an example used in multi-omics studies [14].

- Data Calculation:

- For each feature (e.g., a specific gene) in every study sample within a batch, calculate a ratio value.

- Formula:

Ratio_value = Study_sample_feature_abundance / Reference_material_feature_abundance - This transforms the absolute abundance measurements into relative values scaled to the reference material profiled in the same batch.

- Data Integration:

- The resulting ratio values (or log-transformed ratios) form a new, batch-corrected dataset. These values can be integrated across all batches for downstream analysis, as the technical variation manifested in the reference material has been effectively scaled out [14].

The workflow for implementing this ratio-based correction is as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Batch Effect Management

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet Project Suites) | Commercially available, well-characterized materials derived from the same source (e.g., cell lines). They are profiled alongside study samples in each batch to enable ratio-based correction methods, providing a stable technical baseline [14]. |

| Multiplexed Samples (Cell Hashing / Sample Multiplexing) | Allows multiple samples to be labeled with unique barcodes and pooled together to be processed in a single run. This effectively eliminates batch effects between the pooled samples, as they are exposed to identical technical conditions [12] [8]. |

| Validated Reagent Lots | Large, single lots of critical reagents (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, stains) validated for performance. Using a single lot for an entire study prevents introducing batch effects from lot-to-lot reagent variability [8]. |

| Batch Effect Explorer (BEEx) | An open-source platform designed to qualitatively and quantitatively assess batch effects in medical image datasets (e.g., histology, radiology). It provides visualization tools and a Batch Effect Score (BES) to diagnose issues [10]. |

| Pluto Bio / Omics Playground | Commercial, cloud-based bioinformatics platforms. They provide user-friendly, code-free interfaces with built-in pipelines for multiple batch correction methods (e.g., ComBat, Harmony, Limma) and multi-omics data integration, reducing the computational expertise required [11] [4] [15]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Batch Effects in Multi-Omics Research

Context: This guide is framed within a comprehensive thesis on managing technical variability to enable robust multi-omics data integration. It addresses common pitfalls encountered by researchers and provides actionable solutions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our PCA plot shows samples clustering strongly by processing date, not by disease status. What likely went wrong in our study design and how can we fix it in future experiments? A: This is a classic sign of batch effects confounding your biological signal. The likely source is a flawed or confounded study design, where samples were not randomized across batches [1]. For example, all control samples may have been processed in one week and all disease samples in another.

- Troubleshooting & Prevention:

- Randomize: Always randomize the processing order of samples from different biological groups across all batches (e.g., days, technicians, reagent lots) [16].

- Balance: Ensure each batch contains a balanced representation of all experimental conditions and covariates (e.g., age, sex) [17].

- Replicate: Include technical replicates (the same sample processed in different batches) to explicitly measure batch-related variance [18] [17].

- Document (Metadata): Meticulously record all technical variables (date, operator, instrument ID, reagent lot numbers) as metadata. This is essential for post-hoc statistical correction [18] [11].

Q2: We observed a major shift in our proteomics data after switching to a new lot of fetal bovine serum (FBS). How can we prevent reagent batch variability from invalidating our results? A: Reagent batch variability is a paramount source of irreproducibility and has led to the retraction of high-profile studies [1].

- Troubleshooting & Prevention:

- Single Lot Procurement: For long-term studies, purchase a sufficient quantity of critical reagents (e.g., enzymes, serum, antibodies, columns) from a single lot to last the entire project [1].

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: Implement pooled QC samples. Create a large, homogeneous pool from your study samples (or a representative mimic) and include aliquots of this pool in every processing batch. The QC samples should cluster tightly in analysis, providing a direct measure of batch drift [17].

- Cross-Lot Calibration: If a lot change is unavoidable, process a set of overlapping samples (including your QC pool) with both the old and new lots to calibrate the data.

Q3: Our single-cell RNA-seq data from two different sequencing runs won't integrate properly. The batches separate even after using basic normalization. What specific factors in library prep and sequencing cause this, and what advanced correction should we use? A: Single-cell technologies are particularly sensitive to batch effects due to low RNA input, high dropout rates, and complex protocols [1]. Sources include differences in cDNA amplification efficiency, cell viability at the time of processing, ambient RNA contamination, and sequencing platform calibration [19] [17].

- Troubleshooting & Correction:

- Standardize Protocols: Use identical, validated protocols for cell dissociation, library preparation, and sequencing across all batches [19].

- Choose Specialized Tools: Bulk RNA-seq correction tools (e.g., ComBat, limma) are often insufficient for scRNA-seq [7]. Use methods designed for single-cell data:

- Harmony: Integrates datasets in a low-dimensional embedding space, preserving biological variation while removing batch effects [20] [19] [17].

- Seurat Integration: Uses canonical correlation analysis (CCA) and mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) to find shared biological states across batches [20] [19] [21].

- scANVI: A deep generative model that excels at handling complex, non-linear batch effects and can incorporate cell type labels [19].

- Assess Correction Quality: Use metrics like kBET (k-nearest neighbor batch effect test) or LISI (Local Inverse Simpson's Index) to quantitatively evaluate batch mixing after correction [7] [19] [17].

Q4: When integrating multi-omics datasets (e.g., transcriptomics and proteomics), the data matrices have different scales and many missing values. How do we approach batch correction in this complex, incomplete data scenario? A: This represents the cutting-edge challenge in multi-omics integration. Batch effects are more complex because data types have different distributions, scales, and missing value patterns [1] [21].

- Troubleshooting & Methodology:

- Preprocessing & Harmonization: Independently standardize and normalize each omics layer (e.g., log-transformation, library size scaling) before integration [18] [20].

- Use Imputation-Free or Advanced Integration Methods: Traditional correction methods fail with extensive missing data.

- BERT (Batch-Effect Reduction Trees): A high-performance, tree-based method designed for incomplete omic profiles. It leverages ComBat/limma in a hierarchical framework while retaining maximal data [22].

- HarmonizR: An imputation-free framework that uses matrix dissection to integrate incomplete data, though it may incur more data loss than BERT [22].

- MOFA+: A factor analysis model that identifies common sources of variation across multiple omics datasets, effectively handling missing values [21].

- Mosaic Integration: If you have datasets measuring different but overlapping combinations of omics (e.g., Sample A has RNA+protein, Sample B has RNA+ATAC), tools like Cobolt or MultiVI can create a joint representation [21].

Q5: After applying batch correction, our differential expression results seem biologically implausible. Could we have "over-corrected" and removed real signal? How do we validate our correction? A: Yes, over-correction is a significant risk, especially when batch variables are confounded with biological conditions [1] [11]. Validation is critical.

- Troubleshooting & Validation Protocol:

- Positive and Negative Controls:

- Known Biological Signals: Ensure that well-established, strong biological differences (e.g., gender-specific genes, major cell type markers) are preserved after correction [11] [17].

- Housekeeping Genes: The expression of constitutive housekeeping genes should not become differentially expressed across conditions after correction.

- Quantitative Metrics: Combine multiple assessments [19] [17]:

- Visual Inspection: Use PCA or UMAP plots colored by batch and by biological condition. Successful correction shows mixing by batch and separation by biology.

- Average Silhouette Width (ASW): Measures cluster tightness for biological labels (should be high) and for batch labels (should be low) [22] [17].

- kBET Acceptance Rate: A statistical test for batch mixing; a higher rate indicates successful correction [7] [17].

- Downstream Analysis Consistency: Check if downstream conclusions (e.g., pathway enrichment, predicted cell lineages) are robust and consistent with biological knowledge.

- Positive and Negative Controls:

Quantitative Comparison of Common Batch Effect Correction Methods

The choice of correction tool depends on your data type, structure, and the nature of the batch effect.

Diagram 1: Decision Workflow for Selecting a Batch Effect Correction Method

| Method Category | Tool Name | Primary Use Case | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Bayes / Linear Models | ComBat | Bulk data with known batch factors. | Simple, widely used, effective for additive shifts. | Requires known batch info; may not handle non-linear effects. | [1] [17] |

limma removeBatchEffect |

Bulk data integration into differential expression workflows. | Efficient, integrates with linear modeling. | Assumes known, additive batch effect. | [7] [17] | |

| Surrogate Variable Analysis | SVA | Bulk data with unknown or hidden batch factors. | Can capture unobserved sources of variation. | Risk of over-correction and removing biological signal. | [17] |

| Manifold Alignment / NN-based | Harmony | Single-cell or complex dataset integration. | Fast, scalable, preserves biological variation. | Limited native visualization tools. | [20] [19] [17] |

| Seurat Integration | Single-cell multi-batch integration. | High biological fidelity, comprehensive toolkit. | Computationally intensive for large datasets. | [19] [21] | |

| BBKNN | Fast single-cell batch correction. | Computationally efficient, lightweight. | Less effective for highly non-linear effects. | [19] | |

| Deep Generative Models | scANVI | Complex single-cell data, can use cell labels. | Excellent for non-linear effects, leverages annotations. | Requires GPU, more technical expertise. | [19] |

| Matrix Completion / Advanced Frameworks | BERT | Large-scale, incomplete multi-omics data integration. | Minimal data loss, handles covariates, high performance. | Newer method, may require larger memory for huge trees. | [22] |

| HarmonizR | Imputation-free integration of incomplete omics data. | Handles arbitrary missingness. | Can lead to significant data loss via unique removal. | [22] | |

| Factor Analysis | MOFA+ | Multi-omics integration (matched data). | Handles missing data naturally, identifies shared factors. | Better for vertically integrated (matched) data. | [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent & Material Solutions

Critical materials to control for mitigating batch effects in omics studies.

| Item | Function in Mitigating Batch Effects | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Sample | A homogeneous reference sample run in every batch to monitor and correct for technical drift across experiments [17]. | Should be representative of the entire sample set (e.g., pool of all study samples). |

| Internal Standard Spikes (Metabolomics/Proteomics) | Known amounts of non-biological compounds (e.g., stable isotope-labeled standards) added to every sample to quantify and correct for instrument variability and recovery differences [17]. | Must be well-resolved from endogenous analytes and cover a range of chemical properties. |

| Single-Lot Critical Reagents | Purchasing large quantities of enzymes (e.g., reverse transcriptase), serum (e.g., FBS), antibodies, and solid-phase extraction columns from one manufacturing lot to ensure consistency [1]. | Requires upfront planning and budgeting for the entire study duration. |

| ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) Spikes | Synthetic RNA molecules spiked into RNA-seq libraries at known concentrations. Used to assess technical sensitivity, accuracy, and inter-batch differences in transcriptomics [1]. | |

| Barcoded Kits & Multiplexing Reagents | Kits allowing sample multiplexing (e.g., single-cell cellplexing, TMT/iTRAQ for proteomics). Enables processing of samples from multiple conditions within a single reaction vessel, inherently balancing batch effects [20]. | Demultiplexing steps must be carefully optimized to avoid cross-talk. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Highly characterized, homogeneous materials with assigned property values (e.g., NIST SRM 1950 for metabolomics). Used for inter-laboratory calibration and method validation [18]. |

Diagram 2: Common Sources of Batch Effects Across the Omics Workflow

Core Challenges in Multi-Omics Data Integration

1. What are the primary sources of heterogeneity in multi-omics data? Multi-omics data originates from various high-throughput technologies (e.g., RNA-Seq, mass spectrometry for proteomics), each with its own unique:

- Noise profiles and detection limits: A gene might be detectable at the RNA level but absent at the protein level due to technical or biological reasons [15].

- Data structures and statistical distributions: Transcriptomics data may be count-based, while proteomics and metabolomics data are often continuous, requiring different normalization and statistical models [15] [23].

- Measurement scales and units: Aligning these diverse measurements requires careful transformation to a common scale [24].

2. Why is batch effect correction particularly challenging in multi-omics studies? Batch effects are technical variations from differences in library prep, sequencing runs, or operators. In multi-omics studies, these effects are compounded because:

- Each data type has its own sources of noise, and integrating across these layers multiplies the complexity [11].

- Batch factors can be completely confounded with biological factors (e.g., all cases processed in one batch and all controls in another), making it difficult to distinguish technical artifacts from true biology [6].

- Incorrect correction can lead to over-correction (removing true biological variation) or under-correction (leaving residual bias), both of which can mislead conclusions [11].

3. How do discrepancies between omics layers (e.g., mRNA vs. protein) arise? A high transcript level does not always equate to high protein abundance due to biological regulation. When resolving discrepancies, consider:

- Post-transcriptional regulation: mRNA stability, microRNA activity [23].

- Post-translational regulation: Protein modification, turnover, and degradation rates [23].

- Translation efficiency: Variations in the rate at which mRNA is translated into protein [23].

- Feedback mechanisms: Metabolite concentrations can inhibit enzyme activity, disrupting a simple correlation between protein abundance and metabolite levels [23].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Data Preprocessing & Normalization

Q: How should I preprocess my data for robust multi-omics integration? Proper preprocessing is critical. Follow these steps for each omics layer:

- Quality Control: Identify and remove low-quality data points, outliers, and features with low abundance [23] [24].

- Normalization: Account for technical variations like library size or sample concentration. Methods are often data-specific:

- Batch Effect Regressing: If clear technical factors are known (e.g., processing date), regress them out before integration using tools like

limma[25]. - Filtering: Select highly variable features per assay to reduce dimensionality and noise [25].

- Scaling: Transform normalized data to a common scale (e.g., Z-scores) to facilitate comparison across omics layers [23] [24].

Q: What is the best way to handle different data scales across metabolomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics datasets? Apply normalization techniques tailored to each data type's characteristics, as summarized in the table below.

| Omics Data Type | Recommended Normalization & Transformation Methods | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolomics | Log transformation, Total Ion Current (TIC) normalization | Stabilize variance, account for sample concentration differences [23] |

| Proteomics | Quantile normalization | Ensure uniform distribution of protein abundances across samples [23] |

| Transcriptomics | Size factor normalization, Variance stabilization, Quantile normalization | Account for library size effects and make expression levels comparable [23] [25] |

| All Types (for integration) | Z-score normalization, Scaling to a common range | Standardize data to a common scale for joint analysis [23] |

Batch Effect Correction

Q: Which batch effect correction method should I use for my multi-omics data? The choice depends on your experimental design and data structure. Below is a comparison of common methods.

| Method | Principle | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-based (e.g., Ratio-G) | Scales feature values relative to a common reference material profiled in each batch [6] | Confounded designs where biological groups and batches are inseparable [6] | Requires concurrent profiling of reference sample(s); highly effective in challenging scenarios [6] |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects [6] | Balanced designs where samples from biological groups are distributed across batches [6] | Risk of over-correction; may not handle severely confounded designs well [6] [11] |

| Harmony | Iterative PCA-based removal of batch effects [6] | Single-cell RNA-seq data, multi-sample integration [6] | Performance across diverse omics types (e.g., proteomics) is less established [6] |

| BERT (Batch-Effect Reduction Trees) | Tree-based framework using ComBat/limma for high-performance integration of incomplete data [22] | Large-scale studies with missing values and multiple batches; considers covariates [22] | Retains more numeric values and offers faster runtime than other imputation-free methods [22] |

Q: My data has many missing values. How can I correct for batch effects without making the problem worse? Methods like HarmonizR and the newer BERT (Batch-Effect Reduction Trees) are designed for this. They use matrix dissection and tree-based structures, respectively, to perform batch-effect correction on subsets of the data where values are present, avoiding the need for imputation and the potential biases it introduces [22]. BERT, in particular, has been shown to retain significantly more numeric values and achieve faster runtimes on large-scale, incomplete omic profiles [22].

Method Selection & Interpretation

Q: How do I choose between integration methods like MOFA, DIABLO, and SNF? The choice should be guided by your biological question and data structure.

- MOFA (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis): An unsupervised method that infers a set of latent factors that capture the principal sources of variation across all omics datasets. Use it to deconvolve complex data and discover unknown patterns without using outcome labels [15].

- DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent Components): A supervised framework that integrates data in relation to a categorical outcome variable (e.g., disease vs. healthy). It is ideal for biomarker prediction and classification tasks [15].

- SNF (Similarity Network Fusion): A network-based method that constructs and fuses sample-similarity networks from each omics layer. It is powerful for identifying sample clusters (e.g., disease subtypes) based on shared patterns across omics modalities [15].

Q: After integration, how do I biologically interpret the results?

- Relate Factors to Covariates: In MOFA, correlate the inferred factors with known sample metadata (e.g., clinical traits) to give biological meaning to the latent patterns [25].

- Analyze Weights: Examine the feature weights (e.g., genes, proteins) in each factor or component. Features with large absolute weights are the strongest drivers of that pattern [15] [25].

- Pathway & Network Analysis: Map the features with high weights onto known biological pathways using databases like KEGG or Reactome. This helps determine if the identified pattern is associated with a specific biological process or function [15] [23].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

A General Workflow for Multi-Omics Data Integration

The following diagram outlines a robust, end-to-end workflow for integrating multi-omics data, from experimental design to biological interpretation.

Key Steps:

- Experimental Design: Whenever possible, design your study to include common reference materials (e.g., from the Quartet Project) profiled in every batch. This facilitates the use of robust ratio-based correction methods. Aim for a balanced design where biological groups are distributed across batches [6] [24].

- Data Generation & Individual Preprocessing: Generate data for each omics layer. Preprocess each dataset individually, applying technology-specific normalization and filtering (see the normalization table above) [23] [25].

- Quality Control & Batch Effect Assessment: Perform rigorous QC on each omics dataset. Use PCA plots or other visualization techniques to check for the presence of strong batch effects before correction [24].

- Batch Effect Correction: Based on your experimental design (e.g., confounded or balanced) and data completeness, select and apply an appropriate batch effect correction method (see the batch effect method table above) [6] [22].

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Choose an integration algorithm (MOFA, DIABLO, SNF) based on your research goal (see the method selection diagram) [15].

- Biological Interpretation: Interpret the results by linking outputs to sample metadata, analyzing driving features, and conducting pathway analysis to derive biological insight [15] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource / Material | Function & Application in Multi-Omics Research |

|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Matched DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolite reference materials from four cell lines. Used as internal controls across batches and labs to enable ratio-based batch effect correction and assess data quality [6]. |

| Public Data Repositories | Sources of publicly available multi-omics data for validation, augmentation, or meta-analysis. Key examples include:• The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): Multi-omics data for >33 cancer types [15] [26].• Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE): Multi-omics and drug response data from ~1000 cancer cell lines [26]. |

| Pathway Databases (KEGG, Reactome) | Curated databases of biological pathways. Used to map integrated omics results (genes, proteins, metabolites) onto known pathways for functional interpretation and biological context [23]. |

| Integrated Analysis Platforms | Software platforms that provide code-free, streamlined environments for multi-omics integration and visualization, helping to lower the bioinformatics barrier for experimental biologists [15]. |

In multi-omics data integration research, the integrity of your experimental design is the bedrock of reliable, reproducible findings. A well-designed experiment allows you to isolate true biological signals from technical noise, while a flawed design can render your data uninterpretable or, worse, lead to misleading conclusions. Two pivotal concepts in this arena are balanced and confounded designs. Understanding the distinction is not merely academic—it is a critical practical skill that directly impacts the success of drug discovery, biomarker identification, and therapeutic development [27] [14].

This technical support center addresses the specific, high-stakes challenges researchers face when designing experiments for multi-omics studies. Below are targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs framed within the broader thesis of mitigating batch effects.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our multi-omics analysis yielded strong differential signals, but a reviewer pointed out that our biological groups were processed in completely separate batches. Are our findings valid?

- A: This scenario describes a completely confounded design, where the biological factor of interest (e.g., disease vs. control) is perfectly mixed with (or "aliased with") a batch factor [1] [14]. In this case, it is statistically impossible to distinguish whether the observed differences are due to biology or batch-specific technical variation [14]. The findings, as presented, are likely not valid.

- Troubleshooting Action: Re-analysis alone cannot fix this fundamental design flaw. You must:

- Acknowledge the Limitation: Clearly state in your manuscript that the design is confounded and treat conclusions as hypothetical, requiring validation.

- Employ Reference-Based Correction: If you concurrently profiled a reference material (e.g., a pooled sample or a standard like the Quartet reference materials) in each batch, you can apply a ratio-based method [14]. This scales feature values in study samples relative to the reference, which can correct for batch effects even in confounded scenarios [14].

- Plan for Validation: Design a new, balanced validation study where samples from all biological groups are distributed across batches.

Q2: We designed a balanced experiment, but after sample losses, the groups are now unequal. Has this introduced confounding?

- A: Unequal group sizes (unbalanced design) do not automatically equal a confounded design [28]. Confounding specifically means that you cannot estimate the effect of one factor independently of another because they are "mixed up" [29] [30]. An unbalanced design can reduce statistical power and make tests more sensitive to violations of assumptions but doesn't inherently alias variables [28].

- Troubleshooting Action:

- Assess the Damage: Check if the sample losses systematically correlated with both a biological group and a processing batch. If yes, confounding may have been introduced.

- Use Appropriate Analysis: For a simple unbalanced design, use statistical methods robust to unequal replication. For ANOVA, general linear models can handle this, though interpretation may be more complex than with a perfectly balanced design [28].

- Consider Imputation: For minor imbalances, estimating missing data (e.g., using group means) can be considered to restore balance [28].

Q3: What is the most robust experimental design to prevent batch effects from confounding my multi-omics study?

- A: The gold standard is a balanced, randomized block design.

- Balance: Distribute samples from all biological conditions (e.g., treatment, control, time points) equally across every processing batch [31] [32]. This ensures biological factors are orthogonal (independent) from batch factors [29].

- Randomization: Randomly assign samples within a batch to processing order to avoid confounding with other hidden, time-related variables [31].

- Include Reference Materials: In each batch, process one or more technical control samples, such as commercially available reference materials or a pooled sample from your own experiment. This provides a direct measurement of batch-to-batch variation for correction [14].

Q4: In a factorial experiment (e.g., testing two drug combinations), how can I tell if the design is confounded?

- A: A factorial design is confounded if not all possible combinations of factor levels are tested—this is an incomplete factorial design [33]. For example, if you test Drug A alone, Drug B alone, and the combination A+B, but omit the "no drug" control, you cannot separate the main effects from the interaction or the baseline. The effects are aliased [30] [33].

- Troubleshooting Action:

- Map Your Design: Create a matrix of all factors and their levels. Ensure every cell in the matrix has data.

- Check Historical Studies: Critical reading of literature requires this step. Landmark studies, like Harlow's monkey experiments or early split-keyboard research, were incomplete factorials (e.g., comfort and facial features were confounded), limiting their conclusions [33].

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from a large-scale assessment of Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) under different experimental design scenarios, using multi-omics reference materials [14].

Table 1: Performance of BECAs in Balanced vs. Confounded Scenarios

| Scenario | Design Description | Effective BECAs | Ineffective or Risky BECAs | Key Metric Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced | Biological groups evenly distributed across batches. Batch factor is orthogonal to biology. | ComBat [14], Harmony [14], Mean-Centering [14], SVA [14], Ratio-Based [14] | Most algorithms perform adequately. | High signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) after correction. Accurate identification of Differentially Expressed Features (DEFs) [14]. |

| Confounded | Biological group is completely aligned with batch (e.g., all controls in Batch 1, all treated in Batch 2). | Ratio-Based scaling using a reference material profiled in each batch [14]. | ComBat [14], Harmony [14], Mean-Centering [14], SVA [14]. Risk of removing biological signal along with batch effect. | Low SNR without correction. Ratio method restores correlation with reference data and enables donor sample clustering [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing BECAs Using Reference Materials

This detailed methodology is derived from the Quartet Project, which provides a framework for objectively evaluating batch effects [14].

Objective: To compare the efficacy of multiple BECAs under controlled balanced and confounded experimental scenarios.

Materials:

- Reference Material Suite: Matched DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolite extracts from a characterized source (e.g., Quartet family B-lymphoblastoid cell lines: D5, D6, F7, M8) [14].

- Study Samples: Samples from distinct biological groups.

- Multi-omics Platforms: Next-generation sequencers, mass spectrometers, etc.

Procedure:

- Batch Creation: Process multiple "batches" of data over different times, by different operators, or on different instrument platforms. Each batch should include replicates of all reference materials.

- Scenario Construction:

- Balanced Scenario: For each batch, select one replicate from each study biological group (e.g., D5, F7, M8). Include all replicates of the designated reference sample (e.g., D6) [14].

- Confounded Scenario: Randomly assign batches to study groups. For example, assign 5 batches exclusively to group D5, another 5 to F7, etc. Within those batches, take all replicates for the assigned group. Retain all replicates of the reference sample (D6) in every batch [14].

- Data Generation: Generate transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data for all samples according to standard protocols for your platform.

- Algorithm Application: Apply the suite of BECAs (e.g., ComBat, Harmony, per-batch mean-centering, Ratio-G) to the raw data from each scenario.

- Performance Evaluation:

- Clustering: Use PCA or t-SNE to visualize integration. Successful correction clusters samples by biological donor, not by batch [14].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Calculate SNR to quantify separation between biological groups post-integration.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Measure the accuracy and consistency of identifying differentially expressed features between known biological groups.

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Experimental Design Decision & Consequence Tree

Diagram 2: Reference-Based Ratio Correction Workflow

Diagram 3: Logic Flow for Identifying Confounded Designs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials & Tools for Robust Multi-Omics Experimental Design

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to Balance/Confounding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials [14] | Biological Reference | Matched multi-omics (DNA, RNA, protein, metabolite) standards from a single family. Provides a ground truth for cross-batch and cross-platform normalization via ratio-based methods. | Critical for diagnosing and correcting batch effects in confounded scenarios where standard algorithms fail. |

| Commercial Pooled QC Samples | Technical Control | A homogenized pool of sample material run in every batch. Monitors technical precision and can be used for simpler normalization. | Helps identify batch effect magnitude. Less powerful than characterized reference materials for confounded designs. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software | Tracks sample metadata, processing history, and batch associations. Ensures accurate documentation of the experimental design. | Essential for implementing balance (randomization, blocking) and later diagnosing confounding. |

Statistical Software (e.g., R/Python with sva, limma, ComBat) |

Analytical Tool | Executes Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) and performs statistical analysis of complex designs. | Required to analyze balanced designs and attempt correction in unbalanced ones. |

| Pre-Submission Checklist (Peer-Reviewed) | Protocol | A formal list verifying experimental design aspects (randomization, blinding, balance, control for confounders) before study begins. [14] | Proactively prevents flawed, confounded designs by forcing explicit consideration of these factors. |

| Random Number Generator / Labvanced-type Platform [31] [32] | Experimental Setup Tool | Randomly assigns samples to processing order or participants to experimental conditions within blocks. | Foundational for achieving balance and breaking accidental correlations between biological factors and nuisance variables. |

A Practical Toolkit: Batch Effect Correction Algorithms and Integration Strategies

Batch effects are technical variations introduced during different experimental runs, by different operators, or on different platforms that are unrelated to the biological signals of interest. In multi-omics data integration research, these effects can severely skew analysis, introduce false positives or false negatives, and compromise the reproducibility of findings [3] [14]. Effective batch effect correction is therefore a critical prerequisite for robust data integration and meaningful biological interpretation. This guide provides a technical overview of three prominent batch effect correction algorithms (BECAs)—ComBat, Harmony, and RUV—with practical troubleshooting guidance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Algorithm Comparison: ComBat, Harmony, and RUV

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of ComBat, Harmony, and the RUV family of methods.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ComBat, Harmony, and RUV Algorithms

| Algorithm | Underlying Method | Primary Use Cases | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for known batch variables [17]. | Bulk transcriptomics, proteomics; structured data with known batches [34] [17]. | Simple, widely used; effectively adjusts for known batch effects [17]. | Requires known batch information; may introduce sample correlations in two-step workflows [35]. |

| Harmony | Iterative clustering using PCA and centroid-based correction to integrate datasets [12] [14]. | Single-cell RNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics; multi-omics data integration [12] [8]. | Fast runtime; effective for complex cellular data; preserves biological variation [12]. | Performance may vary by dataset; less scalable for very large datasets [12]. |

| RUV (Remove Unwanted Variation) | Linear regression models to estimate and remove unwanted variation using control features or replicates [34] [14]. | Multiple omics types when negative controls or replicate samples are available. | Does not require known batch labels (RUV variants); uses internal controls for robust correction. | Requires negative control genes or replicates, which can be difficult to define [14]. |

Troubleshooting Common BECA Implementation Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my batch correction not working as expected?

Problem: After applying a batch correction method, samples still cluster by batch in a PCA plot, or biological signals appear to have been lost.

Solutions:

- Assess Batch Effect First: Before correction, use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or UMAP plots to visualize if samples cluster by batch rather than biological condition [12]. Quantitative metrics like Average Silhouette Width (ASW) or the k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET) can provide less biased assessment [12] [17].

- Verify Method Assumptions: Ensure your data meets the algorithm's requirements. ComBat requires known batch labels, while RUV requires negative controls or replicates [14] [17]. Using a method outside its intended use case will yield poor results.

- Check for Confounding: If your biological groups are completely confounded with batch (e.g., all controls in one batch and all treatments in another), most correction methods will struggle [14]. In such cases, a reference-material-based ratio method can be more effective [14].

- Try Alternative Methods: Benchmark multiple algorithms if possible. Studies have shown that no single method performs best across all datasets [12]. If Harmony fails, consider testing Seurat, scANVI, or Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) [12] [8].

FAQ 2: How do I properly set up the model matrix for ComBat?

Problem: There is confusion about which variables to include in the mod argument (model matrix) in ComBat, leading to potential over- or under-correction.

Solution:

The batch argument should contain only the batch variable you want to remove. The mod argument should be a design matrix for the variables of interest you wish to preserve (e.g., treatment, sex, age) [36]. This tells ComBat to protect the biological signal associated with these covariates while removing the batch effect.

- Incorrect:

mod = model.matrix(~ batch + treatment, data=pheno) - Correct:

mod = model.matrix(~ treatment, data=pheno) - For no biological covariates: Use a null model,

mod = model.matrix(~1, data=pheno)[36].

FAQ 3: Am I over-correcting my data and removing biological signal?

Problem: After correction, distinct biological groups or cell types that were separate before correction are now incorrectly clustered together.

Solutions:

- Inspect Distinct Cell Types: After correction, color dimensionality reduction plots by known biological labels (e.g., cell type). If previously distinct cell types are now completely overlapped, especially when they originate from very different conditions, over-correction may have occurred [12].

- Check for Widespread Marker Genes: If a significant portion of your cluster-specific markers after correction consists of genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes), this can indicate over-correction and loss of true biological signal [12].

- Use Positive Controls: If available, track known biological markers through the correction process to ensure they are preserved.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking BECAs

Protocol 1: Reference Material-Based Performance Assessment

Leveraging well-characterized reference materials provides an objective ground truth for benchmarking BECA performance.

Key Reagents:

- Quartet Reference Materials: A suite of multi-omics reference materials derived from four related cell lines, enabling controlled, multi-batch studies [14].

- Internal Standard Samples: Commercially available or in-house pooled samples consistently profiled across all batches.

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Concurrently profile the reference materials alongside your study samples across all batches [14].

- Data Generation: Generate multi-omics datasets (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) across multiple batches, labs, or platforms.

- Scenario Testing: Evaluate BECAs under both balanced (biological groups evenly distributed across batches) and confounded (biological groups completely aligned with batches) scenarios [34] [14].

- Performance Metrics:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Quantifies the ability to separate distinct biological groups after integration [34] [14].

- Relative Correlation (RC): Assesses the correlation of fold changes with a gold-standard reference dataset [34].

- Classification Accuracy: Measures the ability to correctly cluster cross-batch samples by their biological origin [14].

Diagram 1: BECA benchmarking workflow with reference materials.

Protocol 2: A Rigorous Workflow for scRNA-Seq Batch Correction

This workflow is critical for single-cell RNA sequencing data where batch effects are particularly complex.

Key Reagents:

- Cell Hashing Oligos: For sample multiplexing, allowing multiple samples to be processed in a single run, inherently reducing batch effects [12].

- Viability Dyes: To ensure consistent cell quality across batches.

- Commercial scRNA-Seq Kits: From consistent lot numbers to minimize reagent-based variation.

Methodology:

- Quality Control (QC): Filter cells based on QC metrics (e.g.,

nFeature_RNA > 500,percent.mt < 10) [37]. - Normalization & Scaling: Normalize data and regress out unwanted sources of variation (e.g., mitochondrial percentage).

- Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform PCA.

- Batch Correction: Apply a BECA like Harmony, specifying the batch variable (

group.by.vars). - Validation:

Diagram 2: Single-cell RNA-seq batch correction workflow.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials crucial for designing robust batch effect correction experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Batch Effect Mitigation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Batch Effect Management | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet) | Provides a ground truth for objective performance assessment of BECAs across multi-omics datasets [14]. | Benchmarking algorithm performance in proteomics and metabolomics studies [34] [14]. |

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Samples | Monitors technical variation across batches and enables signal drift correction. | Placed at beginning, middle, and end of each sequencing run to track and correct for instrumental drift. |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Enables sample multiplexing, reducing batch effects by processing multiple samples in a single run [12]. | Pooling up to 12 samples in a single scRNA-seq reaction using nucleotide-barcoded antibodies. |

| Internal Standard Compounds | Spiked-in controls for normalization in metabolomics and proteomics to account for technical variability. | Adding known quantities of stable isotope-labeled peptides to all samples in a proteomics experiment. |

| Consistent Reagent Lots | Minimizes a major source of technical variation by using the same lot of enzymes and kits for all samples. | Using a single lot number for reverse transcriptase and library preparation kits throughout a study. |

Successfully correcting for batch effects in multi-omics research requires a thoughtful strategy that combines rigorous experimental design with appropriate computational tools. There is no universally best algorithm; the choice depends on your data type, the underlying study design, and the nature of the batch effects. Always validate correction outcomes using both visual and quantitative methods to ensure that technical noise is reduced without sacrificing meaningful biological signal. By leveraging reference materials and following the troubleshooting guides and protocols outlined herein, researchers can enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their integrated multi-omics analyses.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the ratio-based method for multi-omics data integration? The ratio-based method is a technical approach that scales the absolute feature values of a study sample relative to those of a concurrently measured common reference sample on a feature-by-feature basis. This technique produces reproducible and comparable data suitable for integration across batches, laboratories, platforms, and omics types by effectively addressing batch effects—the systematic technical variations that commonly obfuscate biological signals in large-scale multi-omics studies [38] [39].

Why is this method considered superior for batch effect correction? This method outperforms other batch effect correction algorithms because it directly addresses the root cause of irreproducibility in multi-omics measurement: absolute feature quantification [38]. When batch effects are completely confounded with biological factors of interest, the ratio-based approach demonstrates particular effectiveness compared to other methods [39].

What types of reference materials are required? Effective implementation requires well-characterized, publicly accessible multi-omics reference materials derived from the same set of interconnected reference samples. The Quartet Project exemplifies this approach by providing matched DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolite references from immortalized cell lines of a family quartet, offering built-in truth defined by genetic relationships and central dogma information flow [38].

Can this method handle single-cell multi-omics data? While the core ratio-based principle applies broadly, single-cell data presents additional challenges like extreme sparsity and higher rates of missing data. Specialized tools such as BERT (Batch-Effect Reduction Trees) have been developed specifically for handling incomplete omic profiles in large-scale integration tasks [40].

Troubleshooting Guide

Poor Data Integration After Ratio Scaling

Symptoms: Sample clustering does not match expected biological relationships; low discrimination between known biological groups.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Reference material not representative of study samples. Solution: Ensure reference materials cover the biological and technical variability present in your experimental samples. The Quartet reference materials, for example, provide built-in genetic truth through family relationships [38].

Cause: Inconsistent sample processing between reference and study samples. Solution: Process reference materials and study samples simultaneously using identical protocols to minimize technical variation [39].

Cause: High proportion of missing values in datasets. Solution: For severely incomplete data, consider specialized methods like BERT that retain more numeric values during integration [40].

Inconsistent Results Across Omics Layers

Symptoms: Discrepancies between transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data after integration; unexpected relationships between molecular layers.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Variable data quality across omics platforms. Solution: Implement platform-specific quality control metrics before integration. The Quartet Project provides QC metrics for each omics type, including Mendelian concordance rates for genomic variants and signal-to-noise ratios for quantitative profiling [38].

Cause: Improper normalization within individual omics layers. Solution: Apply appropriate normalization methods for each data type (e.g., log transformation for metabolomics, quantile normalization for transcriptomics) before ratio scaling [23].

Cause: Biological discrepancies not technical artifacts. Solution: Remember that not all discrepancies are technical; biological factors like post-transcriptional regulation can cause legitimate differences between omics layers [23].

Technical Implementation Challenges

Symptoms: Computational bottlenecks; difficulty handling large datasets; inconsistent results across computing environments.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Memory limitations with large feature sets. Solution: Implement data processing in chunks or use high-performance computing frameworks. BERT, for example, leverages multi-core and distributed-memory systems for improved runtime [40].

Cause: Missing values affecting ratio calculations. Solution: Use algorithms that handle missing data appropriately. BERT retains up to five orders of magnitude more numeric values compared to other methods [40].

Cause: Incompatible data structures across platforms. Solution: Standardize data formats into sample-by-feature matrices before integration, ensuring consistent sample IDs and feature annotations [18].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Ratio-Based Scaling

Materials and Equipment

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Provides built-in ground truth with defined genetic relationships | Matched DNA, RNA, protein, metabolites from family quartet [38] |

| Platform-Specific QC Metrics | Validates data quality before integration | Mendelian concordance rates, signal-to-noise ratios [38] |

| Batch Effect Correction Software | Implements ratio scaling algorithm | Compatible with ComBat, limma, or BERT frameworks [39] [40] |

| Normalization Tools | Standardizes data within omics layers | Log transformation, quantile normalization utilities [23] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Reference Material Selection and Processing

- Select appropriate multi-omics reference materials with built-in biological truth. The Quartet reference materials are ideal as they provide defined genetic relationships through a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twins) [38].

- Process reference materials using the exact same protocols, reagents, and sequencing platforms as your study samples.

- Include sufficient technical replicates (at least 3 recommended) to account for technical variation [38].

Step 2: Study Sample Processing

- Process study samples concurrently with reference materials to minimize batch effects.

- Maintain consistent sample preparation protocols across all samples.

- Randomize sample processing order to avoid confounding biological factors with processing time.

Step 3: Quality Control Assessment

- Calculate platform-specific QC metrics before proceeding with integration:

- Remove samples or features failing quality thresholds before proceeding.

Step 4: Within-Omics Normalization

- Apply appropriate normalization methods for each omics type:

Step 5: Ratio Calculation

- For each feature, calculate ratio values using the formula:

Ratio = Feature_value_study_sample / Feature_value_reference_sample - Use the same reference sample for all calculations within a batch.

- Handle missing values appropriately—either exclude features with missing reference values or use imputation methods suitable for your data type.

Step 6: Data Integration

- Combine ratio-scaled data from multiple omics layers using integration algorithms.

- For datasets with substantial missing values, use specialized methods like BERT that retain more numeric values during integration [40].

- Preserve biological covariates (e.g., sex, treatment condition) during integration to maintain biological signals.

Step 7: Validation

- Validate integration performance using built-in biological truth:

- Compare integration performance against alternative methods using objective metrics like average silhouette width [40].

Performance Comparison

Table 2: Batch Effect Correction Method Comparison

| Method | Key Principle | Handles Missing Data | Execution Speed | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based Scaling | Scales feature values to common reference | Moderate | Fast | Studies with completely confounded batch effects [39] |

| BERT | Tree-based decomposition of integration tasks | Excellent | Very Fast (11× faster than alternatives) | Large-scale studies with incomplete profiles [40] |

| HarmonizR | Matrix dissection with parallel integration | Good | Moderate | Proteomics data with missing values [40] |

| Combat | Empirical Bayes framework | Poor | Moderate | Complete datasets with balanced designs [39] |

| limma | Linear models with empirical Bayes | Poor | Fast | Complete datasets with simple batch structures [40] |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Handling Severely Imbalanced Designs For studies with uneven distribution of biological conditions across batches, incorporate covariate information during ratio calculation. Advanced implementations like BERT allow specification of categorical covariates (e.g., biological conditions) that are preserved during batch effect correction [40].

Managing Multiple Batch Effect Factors Realistic experimental setups often involve more than one batch effect factor. The ratio-based approach can be extended to handle multiple technical variations by using appropriate experimental designs and statistical models that account for these complexities [41].

Addressing Data Heterogeneity Different omics layers produce data in varying formats, scales, and with different noise structures. Effective integration requires careful harmonization of these disparate data types through standardization protocols before applying ratio-based methods [18].

Multi-omics data integration combines diverse biological datasets—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to provide a comprehensive understanding of complex biological systems [42] [43]. This approach enables researchers to uncover intricate molecular interactions that single-omics analyses might miss, facilitating biomarker discovery, patient stratification, and deeper mechanistic insights into diseases [44] [42].

A significant challenge in multi-omics research is the presence of batch effects—technical variations introduced when data are generated in different batches, at different times, by different labs, or using different platforms [6] [3]. These non-biological variations can obscure true biological signals, lead to false discoveries, and compromise the reproducibility of research findings [6] [3]. In severe cases, batch effects have even led to incorrect clinical interpretations and retracted publications [3]. Addressing batch effects is therefore a critical prerequisite for meaningful multi-omics data integration, particularly in large-scale, longitudinal, or multi-center studies where technical variability is inevitable [6] [3].

Understanding Multi-Omics Integration Methods

MOFA (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis)

MOFA is an unsupervised dimensionality reduction method that identifies the principal sources of variation across multiple omics datasets [44]. It extracts a set of latent factors that capture shared and specific patterns of variation across different data modalities without requiring prior knowledge of sample groups or outcomes.

Key Applications:

- Exploratory analysis of multi-omics data to identify major sources of variation

- Integration of diverse data types including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics

- Discovery of hidden structures and patterns in complex datasets

DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker Discovery using Latent Components)

DIABLO is a supervised integration framework designed to identify multi-omics biomarker panels that maximize separation between pre-defined sample groups [44]. It uses a multivariate approach to find correlated features across multiple omics datasets that are associated with specific phenotypes or clinical outcomes.

Key Applications:

- Multi-omics biomarker discovery for disease classification or prognosis

- Identification of molecular signatures that distinguish clinical subgroups

- Integration of omics data to predict treatment response or disease progression

Similarity Network Fusion (SNF)

Similarity Network Fusion is an unsupervised method that constructs sample similarity networks for each omics data type and then fuses them into a single composite network [42]. This approach effectively captures both shared and complementary information from different omics modalities.

Key Applications:

- Patient stratification and disease subtyping

- Integration of heterogeneous data types

- Identification of consensus patterns across multiple omics layers

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method | Integration Type | Key Features | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA | Unsupervised | Identifies latent factors; Captures shared and specific variation; Handles missing data | Exploratory analysis; Data visualization; Hypothesis generation |

| DIABLO | Supervised | Maximizes separation of known groups; Identifies correlated multi-omics features | Biomarker discovery; Disease classification; Predictive modeling |

| SNF | Unsupervised | Constructs and fuses similarity networks; Preserves complementary information | Patient stratification; Disease subtyping; Consensus clustering |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do I choose between supervised and unsupervised integration methods for my study?

The choice depends on your research question and whether you have predefined sample groups. Use supervised methods like DIABLO when your goal is to find biomarkers that distinguish known clinical groups (e.g., disease vs. control) or predict specific outcomes [44]. Choose unsupervised methods like MOFA or SNF when you want to explore data structure without prior assumptions, discover novel subtypes, or identify major sources of variation in your dataset [44] [42].

Q2: What are the most effective strategies for handling batch effects in multi-omics studies?