SFARI Gene Database: A Comprehensive Systems Analysis for Autism Research and Drug Discovery

This systems analysis examines SFARI Gene as an integrated resource accelerating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research.

SFARI Gene Database: A Comprehensive Systems Analysis for Autism Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This systems analysis examines SFARI Gene as an integrated resource accelerating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research. We explore the database's foundational architecture, including its curated genetic modules and evidence-based scoring system. The analysis covers methodological applications for researchers and drug development professionals, from data extraction tools to translational research capabilities. We address troubleshooting common challenges in ASD genetic research and validate SFARI Gene's role through comparative assessment with other resources. This review synthesizes how SFARI Gene's evolving infrastructure supports the entire research pipeline from gene discovery to therapeutic development, highlighting current applications and future directions in precision medicine for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Understanding SFARI Gene: Architecture and Core Components for Autism Research

SFARI Gene's Mission and Role in the Autism Research Ecosystem

SFARI Gene is an expertly curated database that serves as a central resource for the autism research community, focused on genes implicated in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) susceptibility. Established in 2008 and supported by the Simons Foundation, this evolving database integrates genetic, neurobiological, and clinical information to advance understanding of autism's complex etiology [1] [2]. The resource has become a trusted source of information for researchers worldwide, providing instant access to the most up-to-date information on human genes associated with ASD through systematic manual curation of peer-reviewed scientific literature [3] [4].

The mission of SFARI Gene is to provide researchers and life science professionals with the most current information in the field of autism research. Through expert curation of available data and development of innovative tools, SFARI Gene aims to foster an engaged, informed research community, advance understanding of autism etiology, and enable development of new treatments [2]. This mission aligns with the broader Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) goal to advance the basic science of autism and related neurodevelopmental disorders [5].

Database Architecture and Modules

Core Structural Components

SFARI Gene is organized into specialized, interconnected modules that collectively provide a comprehensive resource for autism research. The database architecture enables researchers to navigate seamlessly between different data types while maintaining data integrity and relationships.

Table: Core Modules of the SFARI Gene Database

| Module Name | Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Human Gene | Annotated list of genes studied in ASD context | Primary references, support studies, ASD-associated variants, evidence descriptions [4] |

| Gene Scoring | Assessment system for evidence strength | Scores from 1 (high confidence) to 3 (suggestive evidence), regularly updated [1] [4] |

| Animal Models | Genetically modified animal lines for ASD research | Targeting constructs, background strains, phenotypic features relevant to ASD [1] [6] |

| Copy Number Variant (CNV) | Catalog of deletions/duplications linked to autism | Recurrent CNVs, access to Simons Simplex Collection CNV calls [1] |

| Protein Interaction (PIN) | Compilation of molecular interactions | Protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions between ASD gene products [4] |

| Data Visualization | Interactive tools for data exploration | Genome scrubbers, ring browser, interactome visualizations [7] |

Data Curation and Quality Assurance

SFARI Gene employs a rigorous multi-step curation process to ensure data quality and reliability. First, all reports pertaining to a candidate gene are extracted, counted for the number of studies, and compiled into a gene entry. Second, molecular information about the gene is annotated from highly cited and recently published articles and reviewed to assess the gene's relevance to ASD. Third, these annotations are reviewed and the gene is assigned a score reflecting its link to ASD. Finally, the information is added to the database where it becomes publicly available [4]. This meticulous process is performed by expert researchers at MindSpec, who systematically update the contents with additional modules of diverse data, ensuring the database remains current with the rapidly evolving field of autism genetics [2] [3].

Gene Classification and Scoring System

Categorical Classification Framework

SFARI Gene employs a sophisticated classification system that categorizes autism-related genes into four distinct groups based on the nature of their association with ASD:

Rare Genes: This category applies to genes implicated in rare monogenic forms of ASD, such as SHANK3. The types of allelic variants within this class include rare polymorphisms and single gene disruptions/mutations directly linked to ASD. Submicroscopic deletions/duplications encompassing single genes specific for ASD are also included [4].

Syndromic Genes: This category includes genes implicated in syndromic forms of autism, in which a subpopulation of patients with a specific genetic syndrome, such as Angelman syndrome or fragile X syndrome, develops symptoms of autism [4].

Association Genes: This category is for small risk-conferring candidate genes with common polymorphisms identified from genetic association studies in idiopathic ASD (autism of unknown cause), which makes up the majority of autism cases [4].

Functional Genes: This category lists functional candidates relevant for ASD biology not covered by other genetic categories. Examples include genes where knockout mouse models exhibit autistic characteristics, but the gene itself has not been directly tied to known cases of autism [4].

A single gene can belong to multiple categories depending on the mutation type. For instance, a common variant may confer risk for developing idiopathic autism, while an inactivating mutation in the same gene places it in higher risk-conferring categories [4].

Evidence-Based Scoring System

The gene scoring system represents a cornerstone of SFARI Gene's utility to researchers. Each gene receives a score based on the strength of evidence linking it to ASD:

- Score 1: Genes with high confidence of being implicated in ASD

- Score 2: Strong candidate genes

- Score 3: Genes with suggestive but insufficient evidence [8]

Additionally, genes with well-established links to syndromic forms of ASD are categorized as Score S (syndromic) [9]. This scoring system undergoes regular updates based on newly published scientific data and feedback from the research community [4]. The database also tracks a gene's scoring history, allowing researchers to see at a glance whether a gene's link to ASD has become more or less probable over time [4].

Table: SFARI Gene Quantitative Data (2023-2025)

| Data Category | Count | Time Period | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism-associated genes | 1,416 genes | As of 2023 | [3] |

| New genes added | 44 genes | Year 2023 | [3] |

| Variants added | >3,000 variants | Year 2023 | [3] |

| Scored genes | 1,136 genes | Q1 2025 Release | [9] |

| Uncategorized genes | 94 genes | Q1 2025 Release | [9] |

Data Integration and Visualization Capabilities

Advanced Search and Navigation

SFARI Gene 3.0 features enhanced search capabilities that allow researchers to efficiently locate specific genetic information. The Quick Search feature instantly filters rows of results in the main database tables, enabling users to easily locate specific information without scrolling through entire datasets or using their browser's find function [4]. The Advanced Search function provides increased access to all information in the database, including genetic loci, gene scores, associated disorders, and details about supporting scientific studies. Search results can be filtered and sorted to help users find information most pertinent to their research [4].

The database interface has been completely redesigned in version 3.0 to improve functionality and usability. Universal status columns have been added to gene summary pages to indicate recent updates or additions, and blue dots appear on tabs to denote recent changes [4]. The modules are more closely interconnected, allowing researchers to see relevant data contained in different modules and easily navigate between them [4].

Interactive Visualization Tools

SFARI Gene incorporates sophisticated data visualization tools designed to help researchers more effectively navigate and interpret complex genetic information:

The Human Genome Scrubber maps ASD candidate genes by their location along the human genome and provides information including assigned gene scores and the number of reports associated with each gene. Results can be filtered by chromosome and gene score, with an overlay feature showing the ratio of autism-specific versus non-autism-specific reports [7].

The CNV Scrubber provides a quantitative visualization of copy number variants across all chromosomes. This tool shows the number of CNVs found at particular loci, the number of reports curated, and whether a CNV is primarily caused by deletion or duplication [7].

The Ring Browser visualizes all human genetic information contained in the database and illustrates all known protein interactions that occur between gene products associated with ASD [7]. These dynamic tools automatically reflect every update made to SFARI Gene, ensuring researchers always have access to the most current data [7].

Research Applications and Experimental Protocols

SFARI Gene in Diagnostic Panel Development

SFARI Gene serves as a fundamental resource for developing targeted genetic testing approaches for ASD. A 2025 study demonstrated the application of SFARI Gene in creating a customized target genetic panel consisting of 74 genes tested in a cohort of 53 ASD individuals [9]. The research team selected genes based on SFARI scores of 1, 1S, and 2, prioritizing those with the highest number of reported variants for ASD or neurodevelopmental disorders in the HGMD database [9].

The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

Patient Recruitment and Inclusion: 53 unrelated individuals with mean age 12.5 (±4.5) years, diagnosed with ASD according to DSM-5 criteria, encompassing all three severity levels [9].

DNA Extraction and Panel Design: DNA extraction from peripheral blood leukocytes, with panel design based on 74 ASD-associated genes from SFARI Gene database [9].

Next-Generation Sequencing: Conducted using Ion Torrent PGM platform for patients and both parents. Template preparation used Ion Chef System, with sequencing via Ion S5 Sequencing Kit [9].

Variant Filtering and Prioritization: Using VarAft software with filtering criteria including (i) recessive, de novo, or X-linked inheritance patterns; (ii) minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% based on 1000 Genomes, ESP6500, ExAC, and GnomAD databases [9].

Variant Classification: According to ACMG guidelines using Varsome platform, with point-based scoring system for pathogenicity assessment [9].

This study identified 102 rare variants across 53 patients, with nine individuals carrying likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants, achieving a diagnostic yield consistent with contemporary genomic approaches for ASD [9].

Table: SFARI Gene Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Application | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Gene Panels | Diagnostic screening of ASD-associated genes | Clinical genetic testing based on SFARI Gene scores [9] |

| Animal Models | Functional validation of genetic findings | Study molecular, cellular, and behavioral phenotypes [6] |

| CNV Models | Investigation of copy number variations | Model recurrent deletions/duplications observed in ASD [6] |

| Rescue Models | Testing therapeutic interventions | Pharmaceutical, genetic, or cell transplant treatments [6] |

| Protein Interaction Data | Mapping molecular networks | Identify pathways and complexes disrupted in ASD [4] |

Integration with Broader Research Ecosystem

SFARI Gene does not operate in isolation but functions as a hub within an extensive network of complementary research resources. The January 2024 SFARI Gene Workshop brought together developers of various data resources to discuss how SFARI Gene might be reimagined as new data sources and curation technologies emerge [3]. This integration includes several key resources:

The Genotypes and Phenotypes in Families (GPF) platform provides tools for visualizing and analyzing genetic and phenotypic data from SFARI's Simons Simplex Collection, Simons Searchlight, and SPARK cohorts [3]. The SFARI Genome Browser, adapted from open-source code used in gnomAD, offers users a quick way to find variants discovered in genes of interest and assess variant frequency within SFARI cohorts [3].

Additional integrated resources include VariCarta (containing over 300,000 autism-related variant events from 120 published papers), Denovo-db (cataloging de novo variants), and SysNDD (curating gene-disease relationships for neurodevelopmental disorders) [3]. The SynGO consortium has developed an ontology for describing the location and function of synaptic genes and proteins, with more than 1,500 genes now annotated in their database [3].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

SFARI Gene continues to evolve with the field of autism genetics. Looking toward the future, researchers are considering how SFARI Gene might help close the gap between genetic diagnoses for autism and clinical management, with a key need being curation and standardization of genotype/phenotype data [3]. The Simons Foundation has established a 2025 Data Analysis Request for Applications, providing $300,000 awards to support investigators analyzing publicly available datasets, with priority given to applications using SFARI-supported resources [10].

Emerging research approaches include combining gene expression data with clinical genetic findings from SFARI Gene. Studies have found that SFARI genes have statistically significant higher expression levels than other neuronal and non-neuronal genes, with a relationship between SFARI score and expression level—the higher the score (stronger evidence), the higher the expression level [8]. Classification models that incorporate topological information from whole ASD-specific gene co-expression networks can predict novel SFARI candidate genes that share features of existing SFARI genes [8], demonstrating how integrative approaches can extend the utility of the database for discovery research.

As the database continues to grow—with 1,416 autism-associated genes as of 2023, including 44 new genes and more than 3,000 variants added in that year alone [3]—SFARI Gene remains positioned as an indispensable resource for advancing our understanding of autism genetics and accelerating the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Modern biomedical research, particularly in complex genetic disorders like autism spectrum disorder (ASD), relies on sophisticated database systems that integrate multiple genomic data types. The SFARI Gene database exemplifies this integrated approach, serving as a centralized resource that organizes genetic evidence from human genes, copy number variations (CNVs), animal models, and protein interaction networks. Since its debut in 2008 as AutismDB, this resource has evolved into a comprehensive system curated by MindSpec and supported by the Simons Foundation, addressing the pressing need for standardized genetic data in autism research [3]. The core strength of such systems lies in their modular architecture, which enables researchers to navigate the complex landscape of genetic susceptibility by providing instant access to curated evidence across biological domains.

The analytical power of integrated database systems emerges from the interconnectedness of their modules. A query about a specific gene in the Human Gene module can immediately connect researchers to relevant CNV loci in the CNV module, corresponding animal models that recapitulate the gene's function, and protein interaction partners that illuminate potential biological mechanisms. This interconnected structure facilitates the transition from genetic association to biological understanding, ultimately supporting the development of targeted therapeutic strategies. The following sections provide a technical examination of each core module, detailing their constituent data types, curation methodologies, and applications within the context of SFARI Gene database systems.

Human Gene Module

Data Architecture and Curation Standards

The Human Gene module forms the foundational element of genetic databases, providing researchers with structured access to information on human genes associated with specific disorders. In SFARI Gene, this module delivers comprehensive data on all known human genes linked to autism spectrum disorder, incorporating evidence levels that assess the strength of association [1]. The curation process involves systematic manual extraction of data from peer-reviewed scientific literature, followed by significant standardization and data cleaning before export to the database. This meticulous approach ensures that researchers access consistently annotated information regardless of source publication.

The technical implementation of this module relies on a robust data model that captures multiple evidence layers. Each gene entry incorporates primary references, support studies, and ASD-associated variants, with direct links to other database modules. As of 2023, the SFARI Gene database contained 1,416 autism-associated genes, with 44 new genes and more than 3,000 variants added in that year alone [3]. This expanding knowledge base requires continuous refinement of the data architecture to maintain integration integrity while accommodating new data types and evidence classifications.

Gene Scoring Methodologies

A critical innovation in modern gene modules is the implementation of quantitative scoring systems that evaluate the strength of evidence linking genes to disorders. SFARI Gene employs a specialized scoring framework that assigns confidence levels to gene-disease associations, enabling researchers to prioritize investigation targets [1]. The Evaluation of Autism Gene Link Evidence (EAGLE) framework further refines this approach by specifically evaluating evidence for association with ASD rather than neurodevelopmental disorders broadly, using the same rigorous evidence evaluation framework as ClinGen with an additional layer for assessing phenotype quality [3].

The gene scoring algorithm incorporates multiple evidence types:

- Variant evidence: Type and frequency of observed mutations

- Inheritance patterns: De novo, inherited, or mosaic occurrences

- Functional data: Evidence from experimental studies

- Phenotypic specificity: Strength of association with core ASD phenotypes

This multi-parametric approach generates scores that help distinguish genes with definitive ASD associations from those with broader neurodevelopmental links, providing crucial guidance for both research and clinical applications.

Copy Number Variation (CNV) Module

CNV Data Integration Framework

Copy number variations represent a major class of genetic variation significantly implicated in complex disorders, considered one of the leading genetic causes of ASD [1]. The CNV module in integrated database systems specializes in cataloging and interpreting these structural variations, which are DNA segments larger than 1000 base pairs that exhibit duplication or deletion relative to the reference genome [11]. The SFARI Gene CNV module provides data on recurrent CNVs and access to CNV calls from the Simons Simplex Collection, creating a specialized resource for investigating structural variation in autism [1].

Advanced CNV databases like CNVIntegrate exemplify the next evolution of these modules, incorporating both CNVs from healthy populations and copy number alterations (CNAs) from cancer patients across multiple ethnicities [11]. This integrated approach enables direct statistical comparison between copy number frequencies in healthy and affected populations, facilitating the distinction between benign polymorphic variants and pathological mutations. The architecture of such systems typically includes three core functions: (1) gene-query for retrieving CNV information for specific genomic regions, (2) CNV profile generation for specified cancer types, and (3) analytical functions for comparing CNV frequency across populations.

Population Frequency Analysis Protocols

A critical methodological advancement in CNV analysis is the implementation of population-frequency-based filtering to distinguish pathogenic variants from benign polymorphisms. The technical workflow for this analysis involves:

Data aggregation: Compiling CNV calls from multiple population sources, such as the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV) for control populations [12], and disease-specific databases like SFARI Gene for affected cohorts.

Variant normalization: Harmonizing CNV calls across different detection platforms and studies using coordinate conversion tools like LiftOver [13] to ensure consistent genomic positioning.

Frequency calculation: Determining allele frequencies across ethnic populations using statistical methods that account for sample size variations between cohorts.

Association testing: Applying statistical tests (e.g., Fisher's exact test) to identify CNVs with significantly different frequencies between case and control populations.

CNVIntegrate demonstrates this approach by incorporating data from Taiwanese healthy individuals (TWCNV), ExAC database (60,000 healthy individuals across five demographic clusters), Taiwanese breast cancer patients (TWBC), COSMIC, and CCLE [11]. This multi-ethnic framework enables researchers to evaluate whether a cancer-associated variant is population-specific or consistently observed across diverse cohorts.

Table 1: CNV Database Comparative Analysis

| Database | Primary Focus | Sample Size | Population Diversity | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene CNV | ASD-associated CNVs | Simons Simplex Collection | Primarily Western | Recurrent CNVs linked to autism |

| CNVIntegrate | Multi-ethnic CNV/CNA | 1,105,891 total samples [11] | Taiwanese, European, African, South Asian, East Asian, American | Direct healthy/disease population comparison |

| DGV | Healthy population CNVs | Multiple studies | Global | Gold Standard datasets for control frequencies |

| ExAC | Exonic variants in healthy populations | 59,898 individuals [11] | European, African, South Asian, East Asian, Latino | CNV data from exome sequencing |

Animal Models Module

Animal Model Curation and Integration

The Animal Models module provides critical translational bridges between genetic associations and biological mechanisms by cataloging experimentally manipulable systems that recapitulate aspects of human disorders. SFARI Gene includes dedicated animal model data that helps researchers identify underlying mechanisms of ASD and potentially improve treatments [1]. This module typically focuses on mammalian models, particularly mice, which share approximately 95% gene homology with humans and offer opportunities to investigate complex physiological interactions that cannot be recapitulated in vitro [14].

The curation process for animal model data involves extracting detailed experimental information from publications, including:

- Model organism species (mouse, rat, zebrafish, etc.)

- Genetic modification method (knockout, knockin, transgenic, CRISPR)

- Behavioral and physiological phenotypes

- Experimental conditions and assessment methods

- Correspondence to human genetic variants

This structured approach enables researchers to select appropriate models for their experimental questions and compare findings across different model systems. The integration with human gene data allows direct navigation from a human gene associated with ASD to its corresponding animal models, facilitating the design of mechanistic studies based on human genetic findings.

Experimental Validation Workflows

The fundamental rationale for including animal models in genetic databases rests upon their ability to provide experimental validation of gene-disease relationships through controlled manipulation studies. The standard workflow for establishing causal relationships involves:

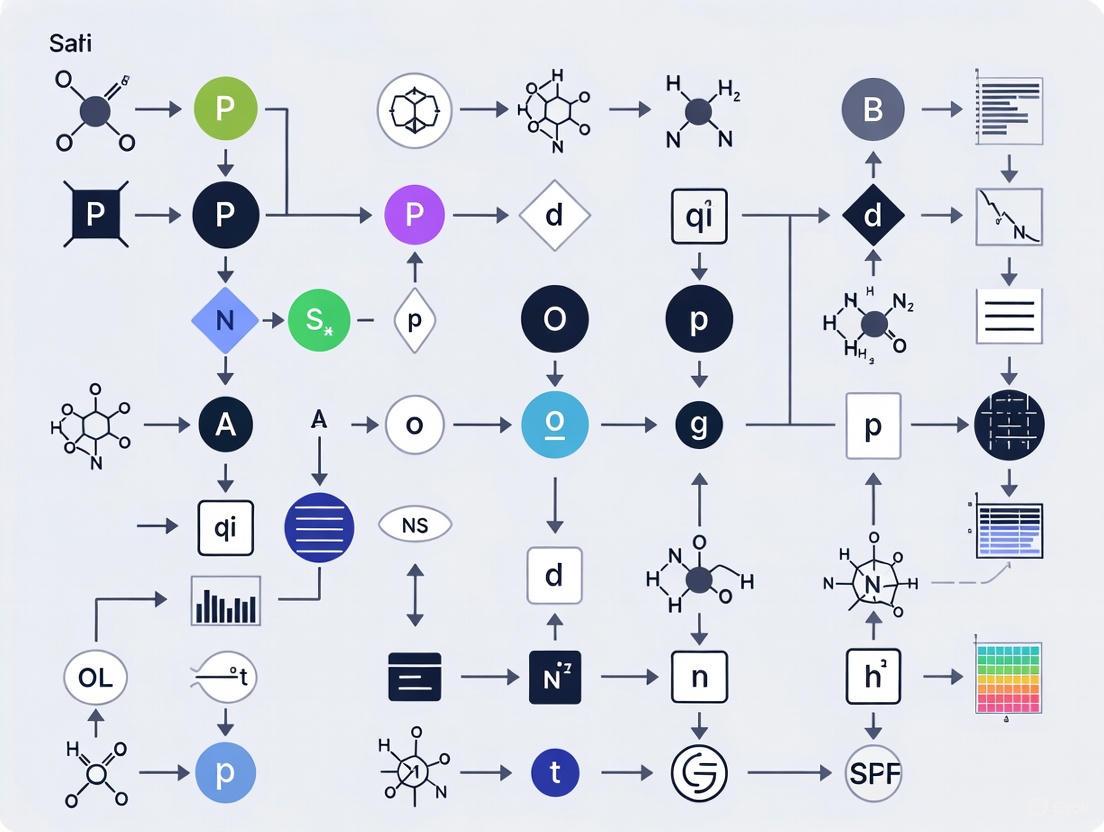

Diagram 1: Animal Model Experimental Validation Workflow

This systematic approach enables researchers to move from genetic correlation in human studies to causal understanding through controlled experimentation in model organisms. The "3Rs" framework (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) guides ethical implementation of these studies, encouraging researchers to minimize animal use while maximizing information yield [14]. Different model organisms offer complementary advantages: mouse models provide mammalian neurobiology similar to humans, zebrafish enable high-throughput screening, and Drosophila offer powerful genetic manipulation tools. Database modules that capture these diverse models significantly enhance the efficiency of translational research by preventing duplication of efforts and facilitating model selection based on specific research questions.

Protein Interaction Module

Protein-Protein Interaction Data Curation

Protein-protein interaction networks provide crucial functional context for genes implicated in disease by mapping their positions within cellular circuitry. The Protein Interaction Module in integrated databases cataloges physical interactions between proteins, offering insights into potential mechanisms underlying genetic associations. Specialized PPI databases like Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID), Molecular INTeraction database (MINT), Biomolecular Interaction Network Database (BIND), Database of Interacting Proteins (DIP), IntAct, and Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) employ distinct curation approaches to extract interaction data from the scientific literature [15].

The technical challenges in PPI data integration are substantial, as different databases may report varying numbers of interactions from the same publication due to differences in curation standards, identifier mapping, or interaction confidence thresholds. For example, comparison studies have found that of 14,899 publications shared by at least two databases, 5,782 (39%) were reported with different numbers of interactions across databases [15]. To address this challenge, the International Molecular Exchange (IMEx) consortium has developed proteomics standards initiative - molecular interaction (PSI-MI) standards to enable data exchange and avoid duplication of curation effort.

Interaction Data Integration and Analysis

Integration of PPI data from multiple sources requires specialized computational approaches to resolve identifier discrepancies and confidence assessment. The technical workflow for PPI data integration involves:

Data retrieval: Downloading complete interaction datasets from individual databases in standardized formats

Identifier mapping: Converting protein identifiers to a common namespace using cross-reference services

Interaction deduplication: Identifying redundant interactions from multiple sources while preserving experimental context

Confidence scoring: Applying quality metrics based on experimental method and publication support

Network analysis: Implementing graph algorithms to identify network properties and functional modules

Table 2: Major Protein-Protein Interaction Databases

| Database | URL | Proteins | Interactions | Organisms | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioGRID | http://thebiogrid.org | 23,341 | 90,972 | 10 | Genetic and chemical interactions [15] |

| IntAct | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact | 37,904 | 129,559 | 131 | Most interactions overall [15] |

| MINT | http://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/mint | 27,306 | 80,039 | 144 | Focus on molecular interactions [15] |

| HPRD | http://www.hprd.org | 9,182 | 36,169 | 1 | Comprehensive human-specific data [15] |

| DIP | http://dip.doe-mbi.ucla.edu | 21,167 | 53,431 | 134 | Quality-controlled dataset [15] |

In the context of SFARI Gene, themed curation projects within BioGRID specifically focus on autism spectrum disorder, compiling interactions relevant to this disorder through expert-guided literature curation [16]. This targeted approach enhances the utility of general PPI resources for autism researchers by pre-filtering interactions based on biological relevance. The integration of these interaction networks with genetic evidence from the Human Gene module enables systems-level analyses that can identify functional modules enriched for autism-associated genes, potentially revealing convergent biological pathways despite genetic heterogeneity.

Integrated Analysis Workflows

Cross-Module Data Integration Protocols

The full analytical power of modular database systems emerges when combining evidence across human genes, CNVs, animal models, and protein interactions. Integrated analysis workflows enable researchers to transition from genetic associations to mechanistic insights through systematic correlation of evidence types. The technical implementation of these workflows requires:

Identifier resolution: Establishing common identifiers across modules (e.g., standard gene symbols) to enable cross-referencing

Evidence weighting: Developing quantitative frameworks that assign appropriate weight to different evidence types

Pathway enrichment: Identifying biological pathways significantly enriched for genetic associations

Network propagation: Using protein interaction networks to connect seemingly disparate genetic associations

SFARI Gene implements this integrated approach through modules that interlink human gene data with associated CNVs, animal models, and through extensions like BioGRID, protein interactions [1] [16]. This enables a researcher investigating a novel ASD-associated gene to immediately access information about structural variants encompassing that gene, animal models that recapitulate its loss or mutation, and protein partners that suggest potential functional roles.

Visualization and Analysis Tools

Effective utilization of integrated database systems requires specialized visualization and analysis tools that present complex multidimensional data in interpretable formats. The SFARI ecosystem includes several such tools:

SFARI Genome Browser: A publicly available tool that adapts the open-source code used in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) to visualize sequencing data from SFARI cohorts, providing variant frequency information and direct links to SFARI Gene [3]

Genotypes and Phenotypes in Families (GPF): An open-source platform for visualizing and analyzing genetic and phenotypic data from SFARI cohorts, enabling browsing by genotype or phenotype and assessment of genotype-phenotype relationships [3]

Variant Annotation Integrator: Part of the UCSC Genome Browser toolkit, this tool annotates genomic variants with functional predictions and database cross-references [13]

These visualization tools work in concert with the core database modules to help researchers identify patterns across data types and generate biologically testable hypotheses from genetic associations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources and Databases

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene | Integrated Database | Centralized ASD genetic evidence | Gene scoring, manual curation, 1,416 ASD genes [3] |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Genome Visualization | Genomic coordinate visualization | Reference genome, custom tracks, data integration [13] |

| BioGRID | Protein Interaction Database | Protein-protein interaction data | 2.25M+ interactions, themed curation projects [16] |

| CNVIntegrate | CNV Database | CNV frequency across populations | Multi-ethnic data, healthy/disease comparison [11] |

| Denovo-db | Variant Database | De novo mutation catalog | 1M+ de novo variants from 72,633 trios [3] |

| VariCarta | Variant Database | ASD-specific variant catalog | 300,000+ ASD variants from 120 papers [3] |

| SynGO | Functional Annotation | Synaptic gene ontology | Expert-curated synaptic gene annotations [3] |

| GPF Platform | Analysis Tool | Family genetic data analysis | Simons cohort data visualization, variant patterns [3] |

Integrated database systems that harmonize human gene, CNV, animal model, and protein interaction data represent essential infrastructure for modern genetic research on complex disorders like autism. The modular architecture of resources like SFARI Gene provides both specialization within data types and integration across biological domains, enabling researchers to navigate the complex landscape from genetic association to biological mechanism. As genetic datasets expand and technologies for data curation advance, these systems will continue to evolve toward more dynamic, interactive platforms that support real-time analysis and hypothesis generation. The ongoing development of standardized frameworks for evidence evaluation, such as the EAGLE system for autism gene links, will further enhance the utility of these resources for both basic research and clinical translation. Through continued refinement of data models, curation standards, and analytical tools, integrated database systems will remain indispensable for extracting meaningful biological insights from the growing volume of genetic data.

The SFARI Gene database serves as a cornerstone resource for the autism research community, providing a systematically curated collection of genes implicated in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) susceptibility. This evolving database utilizes a systems biology approach to integrate diverse genetic data types, linking autism candidate genes to corresponding information from supplementary modules including copy number variants (CNVs) and animal models [17]. Since its inception in 2008, SFARI Gene has grown into a comprehensive knowledgebase, with the latest version containing 1,416 autism-associated genes and more than 3,000 variants added in 2023 alone [3]. The resource is centrally maintained by MindSpec's team of scientists, developers, and analysts who manually curate data from peer-reviewed scientific literature following significant standardization and data cleaning processes before export to the database [3].

At the heart of SFARI Gene's utility is its evidence-based scoring system, which assigns every gene in the database a score reflecting the strength of evidence linking it to ASD development [1]. This scoring framework provides researchers with a standardized method to assess genetic evidence and prioritize genes for further investigation. The system employs a set of annotation rules developed in consultation with an external advisory board, with genes classified into specific categories based on the evidence supporting their link to autism [17]. As of the Q1 2025 Release Notes, the SFARI Gene database includes 1,136 scored genes and 94 uncategorized ones, demonstrating the substantial genetic heterogeneity underlying ASD [9].

SFARI Gene Scoring Categories and Classification Criteria

Core Scoring Categories and Evidence Requirements

The SFARI Gene scoring system employs a multi-tiered classification framework that categorizes genes based on the strength and quality of evidence supporting their association with autism spectrum disorder. The system is dynamically updated as new evidence emerges from the scientific literature, ensuring that the classifications reflect the current state of knowledge [17].

Table 1: SFARI Gene Core Scoring Categories and Evidence Requirements

| Score Category | Evidence Level | Typical Evidence Requirements | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Score 1 | High-confidence | Strong genetic evidence from multiple large-scale studies; well-established association | Strong candidate for diagnostic panels and therapeutic target identification |

| Score S | Syndromic | Association with well-defined genetic syndromes where ASD is a characteristic feature | Important for genetic counseling and syndrome-specific management |

| Score 2 | Strong candidate | Substantial evidence from multiple sources but requiring additional validation | Promising targets for further research and validation studies |

| Score 3 | Suggestive evidence | Preliminary or limited evidence suggesting ASD association | Warrants further investigation but with lower priority |

The scoring system incorporates several specialized designations to provide additional context. The Syndromic (S) category is reserved for genes with well-established links to syndromic forms of ASD, where autism presents as one feature of a broader genetic syndrome [9]. This distinction is clinically valuable as it helps contextualize genetic findings within specific medical frameworks. Genes are regularly re-evaluated as new evidence emerges, with scores updated accordingly based on the publication of new scientific data and feedback from the research community [17].

Complementary Assessment Frameworks

The EAGLE (Evaluation of Autism Gene Link Evidence) framework provides an additional layer of evaluation specifically designed to distinguish genetic findings associated with autism from those linked to other neurodevelopmental disorders [3]. This is particularly valuable for genetic counseling, as it enables a more precise understanding of a gene's specific relationship to ASD rather than neurodevelopmental disorders more broadly. The EAGLE system uses the same evidence evaluation framework as ClinGen but incorporates an additional layer for assessing the quality of phenotypic characterization [3]. SFARI Gene includes EAGLE scores for many of the top-ranked genes in the database, allowing researchers to compare genes with high EAGLE scores with gene lists from SFARI or ClinGen to identify biological distinctions between ASD and intellectual disability without ASD [3].

Methodological Framework for Evidence Curation

Data Curation and Integration Workflow

The SFARI Gene database employs a rigorous, multi-stage curation process to ensure data quality and consistency. The content originates entirely from published, peer-reviewed scientific literature, with expert researchers systematically searching, identifying, and extracting information on genetic studies of ASD in humans and experimental organisms [17]. This manual curation process serves as a convenient point of entry into the vast and growing body of work on the genetic basis of ASD.

The data integration framework encompasses several specialized modules that work in concert to provide a comprehensive resource. The Human Gene module contains thoroughly annotated information about autism candidate genes, relevant references from scholarly articles, and descriptions of the evidence linking each gene to ASD [17]. The Copy Number Variant (CNV) module catalogs recurrent single-gene and multi-gene deletions and duplications in the genome and describes their potential link to autism [17]. The Animal Models module contains information about lines of genetically modified mice that represent potential models of autism, including the nature of the targeting construct, the background strain, and most importantly, a thorough summary of phenotypic features most relevant to autism [17].

Figure 1: SFARI Gene Data Curation and Integration Workflow. This diagram illustrates the multi-stage process from literature identification through manual curation, multi-module data integration, evidence-based scoring, and final data visualization.

Experimental Validation and Technical Approaches

The practical application of SFARI Gene scoring is exemplified in experimental studies that utilize its gene rankings for panel design and variant interpretation. A recent clinical study employed a customized target genetic panel consisting of 74 genes selected from the SFARI Gene database, prioritizing genes with SFARI scores of 1, 1S, and 2 [9]. This approach demonstrates how the scoring system directly influences experimental design in ASD genetic research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SFARI Gene-Based Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Panel | Customized target sequencing | Focused analysis of high-confidence ASD genes |

| Ion Torrent PGM Platform | Next-generation sequencing | Variant detection in candidate genes |

| VarAft Software | Variant filtering and prioritization | Identification of rare pathogenic variants |

| DOMINO Tool | Inheritance pattern prediction | Determining autosomal dominant/recessive patterns |

| BrainRNAseq Database | Gene expression analysis | Assessing neural expression of candidate genes |

The technical methodology for implementing SFARI Gene-informed research involves a coordinated workflow. Gene selection is performed by querying the SFARI Gene database and prioritizing genes based on their scores and the number of reported variants for ASD or neurodevelopmental disorders in complementary databases like HGMD [9]. Sequencing and variant detection utilizes platforms such as the Ion Torrent PGM with template preparation, clonal amplification, and enrichment of template-positive Ion Sphere Particles performed using the Ion Chef System [9]. Variant filtering and prioritization employs specific criteria including recessive, de novo, or X-linked inheritance patterns; minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% based on population databases; and validation through Sanger sequencing [9]. Variant classification follows ACMG guidelines using platforms like Varsome, with a point-based scoring system where variants are classified as benign (≤ -4 points), likely benign (-3 to -1 points), VUS (0-5 points), likely pathogenic (6-9 points), or pathogenic (≥10 points) [9].

Integration with Complementary Databases and Tools

SFARI Gene does not operate in isolation but functions as part of an ecosystem of complementary bioinformatics resources that collectively advance autism research. The Genotypes and Phenotypes in Families (GPF) platform serves as a tool for visualizing and analyzing genetic and phenotypic data from SFARI's Simons Simplex Collection (SSC), Simons Searchlight, and SPARK cohorts [3]. This open-source tool can integrate diverse data from different sources and visualize variants' occurrence in duos and trios as well as complex, multigenerational families [3].

The SFARI Genome Browser, developed by adapting the open-source code used in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), provides a publicly available tool that integrates and visualizes sequencing data from SFARI cohorts [3]. This browser offers researchers a rapid method to find variants discovered in genes of interest or assess the frequency of those variants within SFARI cohorts in individuals both with and without autism diagnoses [3]. Direct links to specific genes in the SFARI Gene database provide additional contextual information, creating a seamless integration between these resources.

Specialized databases like SynGO focus on specific biological domains relevant to autism pathogenesis. This consortium has developed an ontology for describing the location and function of synaptic genes and proteins, with experts in synapse biology annotating synaptic genes and proteins in the SynGO database [3]. With more than 1,500 genes now annotated, SynGO has begun developing interactome networks that can help uncover autism-relevant networks, with the eventual goal of building causality models to inform predictions about how genetic variations impact synaptic function [3].

Cross-Disorder Database Integration

The Developmental Brain Disorder Gene Database employs a cross-disorder approach to curating genes associated with developmental brain disorders, using associations with any of seven conditions—intellectual disability, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, epilepsy, and cerebral palsy—as evidence for a gene's role in developmental brain disorders [3]. This broader perspective helps contextualize ASD risk genes within the wider landscape of neurodevelopmental disorders.

The SysNDD database curates gene-disease relationships specifically for neurodevelopmental disorders, containing more than 3,000 entities, each comprising a gene, an inheritance pattern, and a disease [3]. Expert curators link information describing phenotypes and variant types associated with the disease, a clinical synopsis, and relevant publications, with each assignment receiving a confidence status [3]. The actively maintained database currently includes nearly 1,800 definitive entries, with data accessible through a web browser or API [3].

Figure 2: SFARI Gene Database Ecosystem Integration. This diagram illustrates how SFARI Gene connects with complementary databases and analytical tools to provide a comprehensive resource for autism genetics research.

Clinical Applications and Research Implications

Diagnostic Implementation and Validation

The SFARI Gene scoring system has demonstrated significant utility in clinical diagnostics, particularly in the design of targeted sequencing panels for ASD genetic testing. In one implementation study, researchers developed a customized target genetic panel consisting of 74 genes selected from the SFARI Gene database, focusing on genes with scores of 1, 1S, and 2 [9]. This panel was applied to a cohort of 53 unrelated individuals with ASD, resulting in the identification of 102 rare variants, with nine individuals carrying likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants classified as genetically "positive" [9].

The study identified six de novo variants across five genes (POGZ, NCOR1, CHD2, ADNP, and GRIN2B), including two variants of uncertain significance, one likely pathogenic variant, and three pathogenic variants [9]. These findings not only validated the clinical utility of the SFARI Gene-informed panel but also contributed to expanding the documented mutational spectrum of ASD-associated genes through ClinVar submission of novel de novo variants [9]. The male-to-female ratio in the study cohort was 5.66:1, and the patients encompassed all three DSM-5 severity levels, with 7 individuals diagnosed with ASD Level 1, 15 with ASD Level 2, and 16 with ASD Level 3 [9].

Future Directions and Evolving Frameworks

The SFARI Gene database continues to evolve in response to emerging research needs and technological advancements. A January 2024 workshop convened users and developers to discuss how SFARI Gene might be reimagined in the context of new data sources and curation technologies [3]. Central to these discussions was the question: "Given the state of the field and the range of resources in existence, what would a useful and sustainable autism genetics database look like in 2025 and beyond?" [3].

Future directions may include enhanced genotype-phenotype integration to help close the gap between genetic diagnoses for autism and clinical management, with a key need being curation and standardization of genotype/phenotype data [3]. The integration of functional data from sources like multiplexed assays of variant effects (MAVEs) and computational variant effect predictors (VEPs) represents another frontier, with emerging methods like the acmgscaler algorithm designed to convert functional scores into ACMG/AMP evidence strengths [18]. There is also growing recognition of the need to move beyond binary autism diagnoses to deepen understanding of autism-associated genes' effects on functioning, potentially incorporating frameworks like the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning to comprehensively assess individuals' body function and structure, activities, and participation [3].

The evidence-based gene scoring system employed by SFARI Gene represents a dynamic and robust framework for organizing the complex genetic architecture of autism spectrum disorder. By continuously integrating new evidence from multiple sources and adapting to technological advancements, this resource provides an indispensable foundation for both basic research and clinical applications in ASD genetics.

Manual data extraction from peer-reviewed literature represents a foundational methodology for creating high-quality, specialized biological databases. This meticulous process ensures that complex scientific findings are accurately captured, standardized, and integrated into accessible knowledge resources. Within the context of autism research, manual curation enables researchers to navigate the rapidly expanding genetic evidence linking genes to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with high precision. The SFARI Gene database exemplifies how expert manual extraction transforms dispersed scientific literature into structured, actionable knowledge for the research community [1] [17].

This technical guide examines the comprehensive manual curation methodology implemented by SFARI Gene, detailing the protocols, quality control measures, and data integration strategies that support this critical resource. The database's commitment to manual expert curation distinguishes it from automated approaches, prioritizing accuracy and depth of information through systematic human evaluation of primary research literature [19] [4]. By centering on genes implicated in autism susceptibility, SFARI Gene provides researchers with a trusted platform that integrates genetic, molecular, and biological data through rigorous extraction methodologies.

SFARI Gene represents an evolving knowledge system that seamlessly integrates diverse genetic data types through structured modular architecture. The database employs a systems biology approach that links autism candidate genes within its core "Human Gene" module to corresponding data from supplementary specialized modules [17] [4]. This integrative design encourages hypothesis generation by revealing connections across different data types and evidence streams.

The organizational structure of SFARI Gene centers on several interconnected data modules, each focusing on a specific data type while maintaining interoperability with other modules:

Table: SFARI Gene Database Modules

| Module Name | Primary Content | Curation Scope |

|---|---|---|

| Human Gene | ASD-associated genes, variants, and supporting evidence | Comprehensive annotation of human genetic studies from literature |

| Gene Scoring | Evidence-based scores reflecting gene-ASD association strength | Standardized assessment using defined annotation rules |

| Animal Models | Genetically modified mouse models and phenotypic data | Extraction of targeting constructs, strain background, and phenotypes |

| Copy Number Variant (CNV) | Recurrent deletions/duplications linked to ASD | Cataloging of single-gene and multi-gene CNVs |

| Protein Interaction (PIN) | Protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions | Manual verification of molecular interactions from primary references |

The database's content originates entirely from published, peer-reviewed scientific literature, excluding data presented solely in abstracts or conference proceedings [4]. This selective sourcing ensures that all incorporated information has undergone scientific peer review prior to curation. As of 2023, the database contained 1,416 autism-associated genes, with 44 new genes and more than 3,000 variants added in that year alone, demonstrating the continuous expansion facilitated by systematic curation [3].

Manual Curation Workflow: Principles and Protocols

The manual curation methodology employed by SFARI Gene follows a rigorous multi-stage protocol designed to maximize accuracy, consistency, and comprehensiveness. The process begins with exhaustive literature identification through systematic searching of PubMed, followed by iterative searches to maintain current content [19]. This foundational step ensures that the curation team operates from a complete corpus of relevant scientific literature.

Human Gene Module Curation Protocol

The Human Gene module implements a four-stage annotation process that transforms primary research findings into structured database entries:

- Data Extraction and Enumeration: All human genetic studies pertaining to a candidate gene are extracted and counted, creating a comprehensive inventory of supporting evidence [19].

- Molecular Annotation: A multi-step annotation strategy incorporates diverse molecular information about each candidate gene to assess its relevance to ASD [19].

- Functional Enhancement: The annotation model incorporates highly cited articles and recent publications to extend functional knowledge beyond basic gene information [19].

- Genetic Categorization: Candidate genes are classified into distinct genetic categories based on supporting evidence, including rare monogenic forms, syndromic associations, common variants, and functional candidates [4].

A critical differentiator of SFARI Gene's methodology is that curators review the entirety of information presented in scientific publications, not solely considering conclusions emphasized by authors [19]. This approach captures significant data appearing in supplementary information that authors may not have highlighted in the main text, ensuring a more comprehensive representation of findings.

Gene Scoring Curation Framework

The Gene Scoring initiative implements a standardized assessment protocol to evaluate the strength of evidence linking genes to ASD. This system addresses the growing need to prioritize among hundreds of candidate genes based on empirical support [20]. The scoring framework operates through:

- Standardized Annotation Rules: Evidence evaluation follows predefined criteria developed in consultation with an external advisory board [17] [20].

- Expert Panel Assessment: An external panel of six advisors defines annotation criteria and conducts gene assessments, bringing specialized domain expertise to the evaluation process [20].

- Score Card Generation: Assessment results are compiled into Gene Score Cards that display both assigned scores and supporting evidence [20].

- Continuous Re-evaluation: Gene scores are regularly updated based on new scientific data and community feedback, maintaining currency with evolving evidence [4].

The gene classification system categorizes autism-related genes into four distinct classes: (1) Rare genes implicated in monogenic ASD forms; (2) Syndromic genes associated with syndromic autism forms; (3) Association genes with common polymorphisms identified in genetic association studies; and (4) Functional candidates relevant to ASD biology but not directly tied to known autism cases [4].

Protein Interaction Module Curation

The Protein Interaction Module (PIN) employs a multi-tiered curation strategy to identify and verify molecular interactions:

- Database Consultation: Initial consultation with publicly available molecular interaction databases (HPRD, BioGRID) [21].

- Software Extraction: Data extraction from commercial molecular interaction software (Pathway Studio 7.1) [21].

- Targeted Literature Searching: Manual PubMed searches using structured queries: (Gene Symbol OR Aliases) AND (interact* OR bind* OR regulat* OR function) [21].

- Primary Reference Verification: Every interaction undergoes manual verification through direct consultation with primary reference articles [21].

This combination of computational extraction and manual verification ensures comprehensive coverage while maintaining accuracy through expert review.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive manual curation workflow implemented by SFARI Gene, integrating processes across multiple database modules:

SFARI Gene Manual Curation Workflow

The workflow demonstrates the parallel processing of different data types while maintaining interconnection points that enable data integration across modules. This systematic approach ensures consistent quality while accommodating the specific requirements of each data type.

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

SFARI Gene's manual curation methodology has enabled the systematic organization of extensive genetic information relevant to autism research. The database's growth and composition reflect the cumulative output of this rigorous curation process:

Table: SFARI Gene Database Composition and Growth

| Metric Category | Specific Measure | Value or Status |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Coverage | Total autism-associated genes | 1,416 genes |

| Recent Expansion | New genes added in 2023 | 44 genes |

| Variant Data | Variants added in 2023 | >3,000 variants |

| Data Sources | Primary data origin | Peer-reviewed literature only |

| Evidence Classification | Gene categories | Rare, Syndromic, Association, Functional |

| Expert Involvement | External advisory panel | 6 expert advisors |

The substantial and growing content within SFARI Gene demonstrates the scalability of manual curation methodologies when supported by dedicated expert teams and systematic protocols. The exclusion of data from abstracts and conference proceedings ensures that all incorporated evidence has undergone rigorous peer review [4].

Manual data curation requires access to comprehensive biological data resources and specialized software tools. The following table details key resources employed in SFARI Gene's curation workflow:

Table: Essential Resources for Genetic Data Curation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Curation |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed/NCBI | Literature Database | Comprehensive identification of peer-reviewed studies |

| HPRD | Protein Database | Reference for human protein interactions |

| BioGRID | Interaction Repository | Source of molecular interaction data |

| Pathway Studio | Commercial Software | Extraction and analysis of molecular pathways |

| Simons Foundation Resources | Research Platforms | Access to SFARI-specific datasets and tools |

These resources provide the foundational data that curators evaluate, verify, and integrate through the manual curation process. The combination of public databases and commercial tools ensures both comprehensive coverage and analytical depth.

Manual data extraction from peer-reviewed literature remains an indispensable methodology for creating high-quality specialized biological databases. The SFARI Gene database demonstrates how systematic manual curation protocols can transform dispersed research findings into integrated knowledge resources that support hypothesis generation and scientific discovery. The database's multi-module architecture, supported by rigorous gene scoring and classification systems, provides researchers with a comprehensive platform for exploring the genetic underpinnings of autism.

Future developments in autism genetics databases will likely focus on enhancing genotype-phenotype integration to bridge the gap between genetic diagnoses and clinical management [3]. Emerging resources like the EAGLE framework (Evaluation of Autism Gene Link Evidence) further refine the assessment of gene-ASD associations by specifically evaluating evidence for autism rather than broader neurodevelopmental disorders [3]. As manual curation methodologies evolve, they will continue to incorporate new data sources while maintaining the rigorous standards necessary for scientific reliability. Through continued refinement of these methodologies, resources like SFARI Gene will remain essential tools for advancing our understanding of complex genetic disorders.

The integration of genomic discoveries into biological understanding and clinical practice represents a fundamental challenge in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research. The complex genetic architecture of ASD, involving contributions from rare monogenic forms to common polygenic risk factors, necessitates a structured framework for gene categorization and evaluation. Within the context of SFARI Gene database systems analysis, this whitepaper establishes a comprehensive technical guide for classifying genes across rare, syndromic, association, and functional categories. The SFARI Gene database serves as an evolving resource centered on genes implicated in autism susceptibility, providing researchers with instant access to the most up-to-date information on all known human genes associated with ASD [1]. This framework aims to standardize the interpretation of genetic evidence, facilitating gene prioritization for research and potential therapeutic development.

Recent analyses of ASD genetic databases reveal substantial challenges in the field. A 2025 systematic review identified 13 specialized ASD genetic databases, with only 1.5% consistency observed across four major databases (AutDB, SFARI Gene, GeisingerDBD, and SysNDD) in their classification of high-confidence ASD candidate genes [22]. These inconsistencies stem from differences in scoring criteria and the scientific evidence considered, highlighting the critical need for a unified framework. Such discrepancies have profound implications for both clinical users and researchers, as conclusions may vary significantly depending on the database utilized. The framework presented herein addresses these challenges by integrating multiple evidence dimensions into a coherent classification system aligned with the SFARI Gene ecosystem.

Theoretical Foundations: Genetic Architecture Models Informing Classification

Gene classification frameworks must be grounded in established models of genetic architecture that explain the relationship between genetic variants and disease risk. Four predominant models provide the theoretical foundation for categorizing genes associated with complex disorders like ASD [23].

Table 1: Genetic Architecture Models Informing Gene Classification

| Model Name | Genetic Basis | Variant Effects | Contribution to Heritability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Disease-Common Variant (CDCV) | Common variants (MAF >5%) with small effect sizes | Each variant contributes minimally to risk; cumulative effects | Explains only a portion of heritability ("missing heritability") |

| Rare Alleles of Major Effect (RAME) | Rare variants (MAF <1%) with large effect sizes | High penetrance; often disruptive mutations (e.g., LoF) | Explains moderate percentage of heritability (single-digit percentages) |

| Infinitesimal Model | Numerous variants with very small effects | Weak individual effects (relative risk <1.2); collectively significant | Hidden in numerous sub-threshold variants; requires very large sample sizes |

| Broad-sense Heritability | Complex interactions (G×G, G×E) and epigenetic effects | Non-additive effects; context-dependent manifestations | Explains variance through interaction effects and epigenetic inheritance |

The Common Disease-Common Variant (CDCV) model posits that common diseases like ASD are influenced predominantly by common genetic variants with modest effect sizes. This model formed the basis for early genome-wide association studies (GWAS) but could not fully account for the observed heritability of complex traits, leading to the "missing heritability" problem [23].

The Rare Alleles of Major Effect (RAME) model suggests that rare variants with substantial functional impact contribute significantly to disease risk, particularly in sporadic cases. These variants often involve loss-of-function mutations through mechanisms such as haploinsufficiency or dominant-negative effects, potentially increasing risk by two-fold or more. The RAME model is particularly relevant for classifying genes associated with syndromic forms of ASD [23].

The Infinitesimal Model has gained prominence with modern GWAS, proposing that complex diseases are influenced by thousands of genetic variants, each with minimal individual effect (relative risk below 1.2). This model explains that "missing heritability" is not actually missing but rather distributed across numerous variants that fail to reach significance thresholds in conventional association studies [23].

Finally, the Broad-sense Heritability Model incorporates non-additive genetic effects, including gene-gene interactions (epistasis), gene-environment interactions, and epigenetic mechanisms. This model accounts for heritability patterns that cannot be explained by purely additive genetic effects [23].

Figure 1: Theoretical Models of Genetic Architecture Informing Gene Classification Frameworks. The four predominant models (CDCV, RAME, Infinitesimal, and Broad-sense Heritability) collectively explain the complex genetic basis of ASD and related disorders.

Gene-Disease Clinical Validity Classification Framework

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Gene-Disease Validity Classification Framework provides a standardized approach for evaluating the strength of evidence supporting a gene-disease relationship. This framework employs a qualitative classification system based on genetic and experimental evidence, enabling transparent and systematic evaluation of gene-disease associations [24].

Supportive Evidence Classifications

Definitive classification represents the highest level of evidence, where the gene's role in a specific disease has been repeatedly demonstrated in both research and clinical diagnostic settings and upheld over time. This classification typically requires at least two independent publications documenting human genetic evidence over at least three years. Variants with compelling characteristics such as de novo occurrence, absence in controls, or strong linkage data are considered convincing of disease causality. No contradictory evidence should exist for definitive classifications [24].

Strong classification requires independent demonstration of the gene-disease relationship in at least two separate studies with substantial genetic evidence (numerous unrelated probands harboring variants with sufficient evidence for disease causality). The evidence should total ≥12 points according to the ClinGen standard operating procedure, with no convincing contradictory evidence [24].

Moderate classification indicates moderate evidence supporting a causal role, typically with some convincing genetic evidence (probands harboring variants with sufficient evidence for disease causality), possibly accompanied by moderate experimental data. The evidence scores between 7-11 points according to ClinGen criteria, and while the role may not have been independently reported, no convincing contradictory evidence exists [24].

Limited classification applies when experts consider a gene-disease relationship plausible but evidence remains insufficient for moderate classification. Example scenarios include a moderate number of cases with consistent but non-specific phenotypes, a small number of cases with well-defined consistent presentations, or a single case with a rare distinct phenotype and de novo occurrence in a highly constrained gene [24].

Contradictory Evidence Classifications

Disputed classification applies when initial evidence for a gene-disease relationship is not compelling by current standards and/or conflicting evidence has emerged. This may occur with only a few cases with non-specific phenotypes and missense variants, absence of convincing experimental data, or when initially reported variants have population frequencies too high to be consistent with disease [24].

Refuted classification represents the strongest level of contradictory evidence, where evidence refuting the initial reported evidence significantly outweighs any supporting evidence. This may occur when all existing genetic evidence has been ruled out, initially reported probands were found to have alternative causes of disease, or statistically rigorous case-control data demonstrate no enrichment in cases versus controls [24].

SFARI Gene Scoring System for ASD Association

The SFARI Gene database employs a specialized scoring system that reflects the strength of evidence linking genes to ASD susceptibility. This system provides a practical implementation of gene classification specifically tailored to autism research [1].

Table 2: SFARI Gene Evidence Categories for ASD Association

| Category | Evidence Strength | Genetic Evidence | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Category 1 | Strongest evidence | Rare variants with definitive association | Functional support from multiple models |

| SFARI Category 2 | Strong evidence | Multiple rare variants with strong association | Strong functional evidence |

| SFARI Category 3 | Suggestive evidence | Limited number of rare variants | Emerging functional evidence |

| SFARI Category 4 | Minimal evidence | Preliminary association signals | Limited functional data |

SFARI Gene's scoring system evolves continuously to incorporate new genetic findings, with the database providing ongoing curation for recurrent copy number variants and access to CNV calls from the Simons Simplex Collection [1]. The framework includes not only human gene modules but also incorporates data from animal models, particularly mouse models, which provide valuable information for identifying underlying mechanisms of ASD [1].

Experimental Methodologies for Gene-Disease Association Discovery

Rare Variant Burden Testing Framework

Rare variant association testing presents unique methodological challenges due to the limited statistical power for individual rare variants. Burden testing methods address this by combining information across multiple variant sites within a gene, enriching association signals and reducing multiple testing penalties [25].

The general framework for rare variant burden testing involves relating phenotype values (Yi) to genetic data (Xji) and covariates (Z_ji) through appropriate regression models. For binary phenotypes, the logistic regression model takes the form:

Where β and γ are vectors of unknown regression coefficients for genetic variants and covariates, respectively [25].

The score statistic for testing the null hypothesis (H₀: τ=0) is derived as:

With variance estimated by:

Where vi = e^(γ̂ᵀZi) / (1 + e^(γ̂ᵀZ_i))² [25].

This framework accommodates various study designs (case-control, cross-sectional, cohort, family studies) and phenotype types (binary, quantitative, age at onset), while allowing inclusion of covariates such as environmental factors and ancestry variables [25].

Gene Burden Analytical Framework for Mendelian Diseases

The geneBurdenRD framework represents an open-source R analytical framework specifically designed for rare variant burden testing in Mendelian diseases. This framework was applied successfully to the 100,000 Genomes Project, analyzing protein-coding variants from whole-genome sequencing of 34,851 cases and family members [26].

The minimal input requirements for geneBurdenRD include:

- A file of rare, putative disease-causing variants from Exomiser output files

- A file containing labels for case-control association analyses

- User-defined sample identifiers and case-control assignments [26]

The framework implements rigorous variant quality control, filtering to remove possible false positive variant calls, and employs statistical models tailored to unbalanced case-control studies with rare events. Application of this approach to the 100,000 Genomes Project led to the identification of 141 new gene-disease associations, with 69 prioritized after in silico triaging and clinical expert review [26].

Figure 2: Rare Variant Burden Testing Workflow. The analytical pipeline progresses from raw sequencing data through quality control, annotation, statistical testing, and independent validation to establish gene-disease associations.

Functional Validation and Pathogenicity Assessment

ACMG/AMP Variant Pathogenicity Guidelines

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) have established standardized guidelines for assessing variant pathogenicity, which play a crucial role in gene classification frameworks [27]. These guidelines incorporate evidence from multiple domains:

- Population data: Variant frequency in reference populations (gnomAD, 1000 Genomes)

- Computational and predictive data: In silico prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster)

- Functional data: Experimental evidence from biochemical or cell-based assays

- Segregation data: Co-segregation with disease in families

- De novo data: Absence in parents and confirmed paternity/maternity

- Allelic data: Presence of previously established pathogenic variants

- Database evidence: Curated entries in clinical databases (ClinVar, HGMD) [27]

The ACMG/AMP guidelines employ a weighted evidence classification system with very strong (PVS1), strong (PS1-4), moderate (PM1-6), and supporting (PP1-5) levels for pathogenic evidence, alongside corresponding evidence levels for benign variants [27].

Machine Learning Approaches for Pathogenicity Prediction

Advanced machine learning methods have emerged to address the challenge of variant pathogenicity prediction. The MAGPIE (Multimodal Annotation Generated Pathogenic Impact Evaluator) framework represents a state-of-the-art approach that integrates multiple data modalities for accurate pathogenic prediction across variant types [28].

MAGPIE incorporates six feature modalities:

- Epigenomics: Chromatin accessibility, histone modifications

- Functional effect: Predicted impact on protein function

- Splicing effect: Impact on RNA splicing

- Population-based features: Allele frequencies across populations

- Biochemical properties: Amino acid physicochemical properties

- Conservation: Evolutionary constraint metrics [28]

The framework employs a sophisticated feature engineering pipeline, expanding features to over 3,000 dimensions, then applying rigorous feature selection to reduce dimensionality and prevent overfitting. MAGPIE demonstrates robust performance across multiple validation datasets, achieving AUC values exceeding 0.95, AUPRC above 0.88, and accuracy over 0.9 across balanced and imbalanced datasets [28].

Graph Convolutional Networks for Gene-Disease Association Prediction

Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) offer a powerful approach for predicting novel gene-disease associations by leveraging network topology and node features. The PGCN (Prioritizing Genes with Graph Convolutional Networks) framework implements a GCN-based method that integrates heterogeneous networks including molecular interaction networks, disease similarity networks, and known disease-gene associations [29].

The GCN architecture follows a layer-wise propagation rule:

Where à represents the normalized adjacency matrix, H^(l) contains node embeddings at layer l, W^(l) are trainable weight matrices, and σ denotes the activation function [29].

For association prediction, PGCN uses a bilinear decoder:

Where zi and zj are learned embeddings for diseases and genes, respectively, W is a trainable parameter matrix, and σ is the sigmoid activation function [29].

This approach enables end-to-end learning of gene and disease embeddings that capture both network topology and node features, outperforming traditional methods based on manual feature engineering or predefined data fusion rules [29].

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene-Disease Validation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Annotation Databases | gnomAD, ClinVar, HGMD | Population frequency and pathogenicity assessment | Ensure build compatibility (GRCh37/38); assess data currency and quality metrics |

| In Silico Prediction Tools | SIFT, PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster, VEST4, MAGPIE | Computational impact prediction | Use multiple tools concordance; beware of over-interpretation without experimental validation |

| Functional Assay Systems | Luciferase reporter assays, CRISPR-Cas9 editing, Minigene splicing assays | Experimental validation of variant impact | Select biologically relevant cell types; include proper controls; consider protein isoform complexity |

| Animal Models | Mouse knockouts, Patient-derived xenografts | In vivo functional validation | Consider species-specific differences; validate construct and face validity; assess multiple phenotypic domains |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, Base editors, Prime editors | Isogenic model generation | Optimize delivery efficiency; control for off-target effects; include proper rescue experiments |

| Multi-omics Platforms | RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, Proteomics | Molecular mechanism elucidation | Implement appropriate batch correction; ensure sufficient replication; integrate across data types |

The research reagents and platforms listed in Table 3 represent essential tools for progressing from genetic association to functional validation. These resources enable researchers to establish causal relationships between genetic variants and disease phenotypes through orthogonal experimental approaches [27] [28].