Optimizing Gene Co-expression Network Analysis: A Practical Guide for Parameter Settings and Best Practices

Gene co-expression network analysis is a powerful systems biology approach for identifying functionally related genes and biomarkers, but its effectiveness heavily depends on appropriate parameter settings and data processing choices.

Optimizing Gene Co-expression Network Analysis: A Practical Guide for Parameter Settings and Best Practices

Abstract

Gene co-expression network analysis is a powerful systems biology approach for identifying functionally related genes and biomarkers, but its effectiveness heavily depends on appropriate parameter settings and data processing choices. This comprehensive guide synthesizes current evidence to help researchers optimize co-expression network construction from both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data. We cover foundational principles, methodological considerations for different data types, troubleshooting for common challenges like data sparsity, and validation strategies using biological gold standards. By providing clear recommendations on normalization methods, network inference algorithms, and analysis strategies, this article serves as an essential resource for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals seeking to maximize biological insights from their transcriptomic data.

Understanding Gene Co-expression Networks: Core Concepts and Biological Significance

Defining Gene Co-expression Networks and Their Applications in Biomedical Research

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a gene co-expression network (GCN)? A gene co-expression network is an undirected graph where each node represents a gene. An edge connects two genes if they exhibit a significant co-expression relationship, meaning their expression levels rise and fall together across multiple samples or experimental conditions. These networks help identify genes that are controlled by the same transcriptional regulatory program, are functionally related, or are members of the same biological pathway or protein complex [1] [2].

What is the key difference between a GCN and a Gene Regulatory Network (GRN)? A GCN depicts correlation or dependency relationships between genes without specifying direction or causality. In contrast, a GRN is a directed network where edges represent specific biochemical processes like activation or inhibition, thereby inferring causal relationships between genes [1].

What are the main steps in constructing a GCN? Constructing a GCN is generally a two-step process [1] [2]:

- Calculate a co-expression measure: A similarity score (e.g., Pearson's correlation) is calculated for each pair of genes based on their expression profiles across samples.

- Select a significance threshold: A threshold is determined, and gene pairs with a similarity score above this threshold are considered significantly co-expressed and connected by an edge in the network.

My co-expression network has too many false positives. What could be the cause? High false positive rates can arise from several factors [3] [4]:

- Insufficient Sample Size: Differential co-expression analysis, in particular, requires large sample sizes to be reliable.

- Technical and Biological Confounding Factors: Unaccounted-for factors in the data can introduce spurious correlations.

- High Data Sparsity: This is a major challenge in single-cell RNA-seq data, where a high proportion of zero counts can lead to inaccurate co-expression estimates.

- Indirect Correlations: Standard correlation measures may capture indirect relationships. Methods using partial correlation (e.g., Graphical Gaussian Models) can help distinguish direct from indirect interactions [2].

How can I improve the biological relevance of my GCN?

- Aggregate Networks: Combining networks built from multiple, smaller down-sampled datasets can improve the recovery of biologically relevant associations compared to using one large dataset [5].

- Use Targeted Approaches: Methods like TGCN (Targeted Gene Co-expression Networks) use a trait of interest to build smaller, more focused networks, leading to more specific biological interpretations [6].

- Focus on Statistically Validated Hubs: Instead of relying solely on connectivity scores, use methods that provide statistical significance (p-values) for hub genes to reduce noise and bias [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Selecting an Appropriate Correlation Measure

Problem: Choosing the wrong co-expression measure can lead to missing biologically important relationships or introducing noise.

Solution: Select a measure based on your data characteristics and the biological relationships you aim to capture. The table below compares the most common measures.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Gene Co-expression Measures

| Measure | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson's Correlation [1] [2] | Linear relationships | Simple, widely used, intuitive interpretation | Sensitive to outliers; assumes normal distribution; cannot capture non-linear relationships. |

| Spearman's Rank Correlation [1] | Monotonic (non-linear) relationships | Robust to outliers | Less sensitive to actual expression values; may have high false positives with small sample sizes. |

| Mutual Information [1] [4] | Linear and complex non-linear relationships | Can detect sophisticated non-linear dependencies | Requires large sample sizes for accurate distribution estimation; may detect biologically meaningless relationships. |

| Biweight Midcorrelation (bicor) [1] | A robust alternative to Pearson | More robust to outliers than Pearson; often more powerful than Spearman | Less commonly implemented in some standard pipelines. |

| Euclidean Distance [1] | Measuring geometric distance between expression profiles | Considers both direction and magnitude of expression vectors | Not ideal when absolute expression levels of related genes are vastly different. |

Recommended Protocol:

- Assess Data Distribution: Test if your data meets the normality assumption for Pearson correlation.

- Check for Outliers: Use visualization techniques (e.g., boxplots) to identify outliers. If significant outliers are present, consider robust measures like Spearman or bicor.

- Define Relationship Type: If you suspect non-linear but monotonic relationships, Spearman is a good choice. For more complex non-linearities, Mutual Information might be necessary, but ensure you have a large sample size.

Issue 2: Determining the Optimal Sample Size and Threshold

Problem: Network quality is highly dependent on sample size and the threshold used to define significant edges.

Solution: There is no universal answer, but the following evidence-based guidance can help.

Table 2: Sample Size and Threshold Selection Guidelines

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| General Network Construction | Use a scale-free topology criterion (e.g., WGCNA's soft thresholding) [1]. | Many biological networks are scale-free, and this method selects a threshold that coerces the network toward this property. |

| Differential Co-expression Analysis | Ensure large sample sizes (n > 100 is often a minimum) [3]. | Differential co-expression requires sufficient power to detect changes in correlation patterns between conditions. |

| Large Available Datasets | Consider down-sampling and network aggregation [5]. | Building networks from multiple, smaller random subsets of your data and then aggregating them can outperform a single network from all samples by reducing noise. |

| p-value Based Thresholding | Use with caution and in combination with other criteria [1]. | A simple p-value cutoff (e.g., 0.05) may not reflect biological relevance and can be influenced by sample size. |

Recommended Protocol (WGCNA Soft-Thresholding):

- Construct Networks: Build networks for a range of soft-thresholding powers (β).

- Calculate Model Fit: For each power, calculate the model fit (R²) to a scale-free topology.

- Plot and Select: Plot R² against the powers. Choose the lowest power where the scale-free topology fit curve flattens out (often above an R² of 0.8 or 0.9). This achieves a balance between network connectivity and scale-free property.

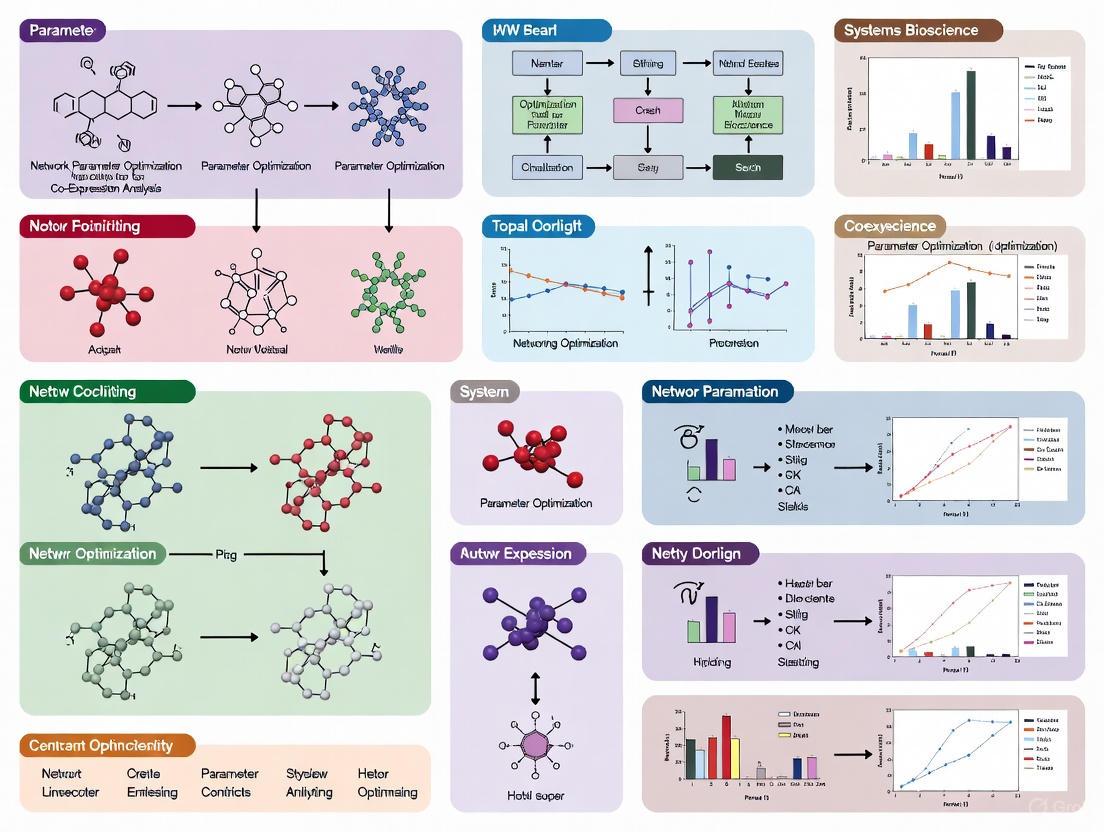

Figure 1: General Workflow for Constructing a Gene Co-expression Network.

Issue 3: Handling Single-Cell RNA-seq Data Sparsity

Problem: Standard co-expression measures perform poorly on single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data due to its high sparsity (excess zero counts) and heterogeneity [4].

Solution:

- Use Specialized Methods: Employ tools specifically designed for scRNA-seq data, such as scLink, which explicitly models the excess zeros using a Gaussian graphical model [4].

- Avoid Standard Pre-processing Pitfalls: Contrary to intuition, common pre-processing steps like normalization and imputation do not consistently improve co-expression estimation and can even introduce artificial correlations and bias [4]. Carefully evaluate the impact of any pre-processing step.

- Consider Pseudo-bulk Analysis: In some cases, aggregating expression counts from groups of similar cells (e.g., by cell type or sample) to create "pseudo-bulk" profiles can reduce sparsity, but this approach also loses single-cell resolution [4].

Figure 2: Troubleshooting Co-expression Analysis for scRNA-seq Data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| WGCNA [8] [9] | R Package | Constructs weighted co-expression networks and identifies gene modules. | Scale-free topology assumption; integrated module-trait association analysis. |

| lmQCM [1] | Algorithm / R Package | Detects co-expression modules. | Identifies smaller, potentially overlapping modules; useful for dense, localized structures. |

| TGCN [6] | R Package | Builds targeted co-expression networks. | Uses bootstrapped LASSO to create smaller, trait-focused networks for hypothesis-driven research. |

| Cytoscape [8] | Desktop Application | Network visualization and analysis. | Open-source platform for customizable visualization of complex networks and modules. |

| clusterProfiler [8] | R/Bioconductor Package | Functional enrichment analysis. | Standard tool for GO and KEGG pathway enrichment of gene modules. |

| GTEx Portal [10] | Data Resource | Public repository of human tissue-specific gene expression. | Provides data for constructing tissue-specific networks (TSNs) and Transcriptome-Wide Networks (TWNs). |

| TCGAbiolinks [8] | R/Bioconductor Package | Data Access | Facilitates programmatic download and preparation of TCGA data for analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental premise of the "guilt-by-association" principle in co-expression analysis?

The guilt-by-association principle states that genes with highly correlated expression patterns across multiple conditions or samples are likely to be involved in the same biological pathway or cellular process [11]. In a co-expression network, this means that if Gene A is of known function and Gene B has an unknown function, but they are consistently co-expressed, one can infer that Gene B likely shares a similar biological function with Gene A [11]. This principle allows researchers to functionally annotate unknown genes based on their co-expression patterns with well-characterized genes.

FAQ 2: How do I determine the appropriate correlation threshold for constructing my co-expression network?

Selecting a correlation threshold involves balancing biological relevance with network complexity. Common approaches include:

- Using an arbitrary fixed cutoff (e.g., |r| ≥ 0.7) [12]

- Selecting the top percentage of correlations (e.g., top 0.5% of positive and negative correlations) [11]

- Choosing a threshold that results in a network following a scale-free topology [11]

- Using random permutations of expression data to determine statistically significant interactions [11] The optimal threshold may vary depending on your dataset size and biological question. Start with a stricter threshold (higher |r|) for a more focused network of high-confidence interactions.

FAQ 3: What are the key differences between co-expression networks and protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks?

Co-expression networks and PPI networks operate at different biological levels and serve complementary purposes [12]:

- Co-expression networks capture transcriptional coordination and regulatory relationships, identifying genes that respond similarly to biological conditions, even if their proteins don't physically interact [12].

- PPI networks focus on physical and functional interactions between proteins, representing downstream mechanistic relationships [12]. A gene co-expression module may reveal genes regulated by a common transcription factor, while a PPI network would show how their protein products physically interact to perform functions [12].

FAQ 4: How can I ensure my co-expression network visualizations are accessible to readers with color vision deficiencies?

Color vision deficiencies affect approximately 8% of males and 0.5% of females, making accessibility crucial [13]. Follow these guidelines:

- Avoid red/green color combinations, the most problematic combination [13]

- Use accessible alternatives like green/magenta, yellow/blue, or red/cyan [13]

- For heatmaps, use a two-color scale with a light color (white) in the middle and two dark colors at the ends [13]

- For multi-color visualizations (e.g., fluorescence images), use magenta/yellow/cyan instead of red/green/blue [13]

- Always include greyscale versions of individual channels alongside merged images [13]

- Use tools like Color Oracle or built-in simulators in ImageJ and Photoshop to proof your visuals [13]

FAQ 5: Should I perform combined or separate co-expression analyses when comparing two experimental conditions?

The choice depends on your research question [12]:

- Combined analysis (all samples in one network) identifies gene modules conserved across conditions, representing core biological processes unaffected by your experimental manipulation [12].

- Separate analyses (each condition independently) reveals condition-specific modules and differences in network topology, highlighting biological pathways disrupted in disease versus normal states [12]. A hybrid approach is often most effective: start with a combined analysis to identify shared modules, then perform group-specific analyses to explore condition-specific differences in network properties [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Weak or Biologically Irrelevant Co-expression Relationships

Problem: Your co-expression network contains many connections that don't correspond to known biological relationships or appear random.

Solutions:

- Preprocess data properly: Ensure gene expression data is log2-transformed to scale values to the same dynamic range before calculating similarity scores [11].

- Choose appropriate correlation measures:

- Filter low-expression genes: Remove genes with near-zero variation across samples, as they can produce NaN values in correlation matrices [12].

- Apply data transformation: Use z-score normalization when comparing expression profiles across different experiments [14].

Issue 2: Network Too Dense or Too Sparse for Meaningful Analysis

Problem: Your network contains either too many connections (making interpretation difficult) or too few connections (missing biological relationships).

Solutions:

- Adjust threshold systematically:

- Start with a higher threshold (e.g., |r| ≥ 0.8) and gradually decrease until biologically meaningful modules emerge

- Use scale-free topology criteria to guide threshold selection [11]

- Consider weighted networks: Instead of hard thresholds, use weighted networks that preserve the continuous nature of co-expression information [11]

- Apply network pruning algorithms: Use methods like ARACNE that eliminate indirect interactions by analyzing gene triplets [11]

- Validate with known pathways: Check if your network recovers established biological pathways at different threshold levels

Issue 3: Poor Module Detection or Unstable Modules

Problem: Detected modules are inconsistent across similar datasets or don't correspond to biological pathways.

Solutions:

- Increase sample size: Co-expression networks generally require larger sample sizes for stable modules; consider combining datasets when appropriate [15]

- Use consensus approaches: Apply consensus module detection across multiple networks to identify robust modules [16]

- Try different clustering algorithms: Experiment with various community detection methods (e.g., hierarchical clustering, dynamic tree cutting, Markov clustering)

- Leverage eigengene analysis: Represent modules by their eigengene (first right-singular vector) to study inter-modular relationships [16]

Issue 4: Technical Artifacts Dominating Biological Signal

Problem: Batch effects or technical variations are creating strong co-expression relationships that don't reflect biology.

Solutions:

- Apply batch correction: Use established methods (ComBat, limma removeBatchEffect) when combining datasets from different sources [15]

- Check module enrichment: Validate that detected modules are enriched for known biological pathways rather than technical factors

- Use permutation testing: Compare your network to ones generated from permuted data to assess significance of observed connections [11]

- Inspect eigengene-trait relationships: Correlate module eigengenes with biological traits rather than technical covariates [16]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Co-expression Network Construction Protocol

Objective: Construct a gene co-expression network from RNA-seq data to identify functionally related gene modules.

Materials Needed:

- Gene expression matrix (rows = genes, columns = samples)

- Computational environment (R/Python with necessary packages)

- Network visualization and analysis tools (Cytoscape [17], WGCNA [11])

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preprocessing

- Filter out genes with low expression (counts < 10 in more than 90% of samples)

- Normalize read counts using appropriate method (e.g., TPM, FPKM)

- Apply log2 transformation to reduce dynamic range [11]

- Consider batch effect correction if combining multiple datasets

Similarity Matrix Calculation

- Choose correlation measure based on data characteristics

- Calculate pairwise similarity for all gene pairs

- Consider using bi-weight mid-correlation for robustness [11]

Network Construction

- Select significance threshold based on research goals

- Apply threshold to create adjacency matrix

- Alternatively, use soft thresholding to create weighted network [11]

Module Detection

- Identify modules of highly interconnected genes using clustering

- Merge similar modules if necessary

- Calculate module eigengenes as representatives [16]

Functional Validation

- Perform enrichment analysis on module genes

- Correlate module eigengenes with sample traits

- Validate hub genes using external data

Table 1: Comparison of Correlation Measures for Co-expression Analysis

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | Simple, interpretable | Assumes linearity, sensitive to outliers | Normally distributed data with linear relationships |

| Spearman Correlation | Robust to outliers, no distribution assumptions | Less powerful for true linear relationships | Data with outliers or non-normal distribution |

| Bi-weight Mid-correlation | Highly robust to outliers | Less commonly implemented | Data with significant noise or outlier concerns |

| Mutual Information | Detects non-linear relationships | Computationally intensive, requires more samples | Complex non-linear dependencies |

Eigengene Network Analysis for Studying Module Relationships

Objective: Analyze relationships between co-expression modules to identify higher-order organization of the transcriptome.

Procedure:

Calculate Module Eigengenes

- For each module, compute the first right-singular vector of the standardized expression matrix [16]

- This eigengene represents the dominant expression pattern in the module

Construct Eigengene Network

- Calculate correlations between all pairs of module eigengenes

- Define adjacency using signed weighted approach: aEigen,IJ = [1 + cor(EI,EJ)]/2 [16]

- This preserves information about the sign of relationships

Analyze Network Properties

- Calculate scaled connectivity for each eigengene [16]

- Identify meta-modules (clusters of related modules)

- Compare eigengene networks across conditions

Integrate with Sample Traits

- Correlate eigengenes with clinical or experimental traits

- Identify modules most associated with phenotypes of interest

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for Co-expression Network Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Analysis Platforms | Cytoscape [17], Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) [11], NetworkX [12] | Network construction, visualization, and analysis | Open source, freely available |

| Expression Databases | Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [18], ArrayExpress [18], Plant-specific databases [11] | Source of public expression data for analysis | Publicly accessible repositories |

| Specialized Algorithms | ARACNE [11], MCL [18], Markov cluster algorithm | Network pruning, module detection | Implemented in various packages |

| Programming Environments | R, Python with libraries (pandas, numpy, scipy) [12] | Data manipulation and correlation calculations | Open source |

| Visualization Tools | Cytoscape [17], LGL [18], BioLayout [18] | Network layout and visualization | Mostly open source |

Workflow Visualization

Core Components of a Network

This section defines the fundamental building blocks of any network, which are essential for understanding and conducting co-expression analysis.

Table: Core Network Components and Their Definitions

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Nodes (Vertices) | The individual entities within the network. In a gene co-expression network, each node represents a gene [19] [20]. |

| Edges (Links, Ties) | The relationships or interactions between nodes. An edge between two genes signifies a co-expression relationship [19] [20]. |

| Degree | The number of connections (edges) a node has. A gene with a high degree may be considered a hub gene [19]. |

| Connected Graph | A graph where there is a path between every pair of vertices [21]. |

| Connected Component | A maximal connected subgraph of an undirected graph. Each vertex and edge belongs to exactly one component [21]. |

Key Network Analysis Metrics

Beyond basic components, several metrics help quantify the importance and position of nodes within the network.

Table: Key Network Centrality and Connectivity Measures

| Metric | Definition and Research Application |

|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Quantifies the number of direct connections a node has. Identifies highly connected "hub" genes that may be functionally critical [19]. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Measures how often a node acts as a bridge along the shortest path between two other nodes. Identifies genes that connect different network modules [19] [20]. |

| Closeness Centrality | Measures how close a node is to all other nodes in the network. Genes with high closeness may facilitate rapid information or regulatory spread [19]. |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Considers a node's influence based on the influence of its neighbors. Identifies genes that are connected to other important genes [19]. |

| Edge-Connectivity (λ(G)) | The minimum number of edges that, if removed, would disconnect the graph. A higher value indicates a more resilient network [21]. |

Troubleshooting Common Network Analysis Issues

FAQ: How do I handle missing values in my gene expression data during network construction?

Missing data is a common challenge that can significantly impact network integrity. GeCoNet-Tool offers built-in options for processing data with missing values [20]. The recommended methodology is:

- Input Data: Prepare a gene co-expression matrix in

.csvformat, where rows represent genes and columns represent experimental conditions [20]. - Data Processing: Within the tool, you can select processing options to handle missing or zero values. Common practices include:

- Paired Element Calculation: The tool automatically determines the number of paired, non-missing conditions for every gene pair. This information is used to weight the reliability of the similarity measure [20].

FAQ: How do I choose the right similarity measure and threshold for inferring my co-expression network?

The choice of similarity measure and cutoff threshold directly controls the density and biological relevance of your network.

Selecting a Similarity Measure:

- Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC): This is the most widely used method for initial network construction. It measures linear relationships between gene expression profiles [20]. GeCoNet-Tool currently uses PCC for its calculations [20].

- Future Alternatives: For non-linear relationships, other measures like Spearman correlation, signed distance correlation, or mutual information may be more appropriate and could be considered in future tool updates [20].

Setting the Edge Threshold: GeCoNet-Tool uses a dynamic, data-driven approach [20]:

- Bin Classification: PCCs are classified into different intervals (bins) based on the number of paired conditions for each gene pair [20].

- Cutoff Value: You must input a cutoff value (e.g., 0.005, 0.01), which represents the top percentage of PCCs selected within each bin [20].

- Sliding Threshold Curve: The tool fits a curve to these binned PCCs to determine a sliding threshold. This curve provides a trade-off, maintaining connections for gene pairs with more supporting data while applying a stricter threshold to pairs with fewer shared conditions [20].

- Optimization Goal: Execute the tool multiple times with different cutoff values. The optimal cutoff retains the majority of nodes in a connected network while minimizing the number of spurious edges [20].

FAQ: My network is too dense and uninterpretable. How can I simplify it to find key genes?

A dense network can be refined using network analysis techniques to isolate structurally and functionally important elements.

Community Detection: Identify clusters of highly interconnected genes that often share biological functions.

Core Gene Identification: Find the most resilient and centrally located genes in your network.

- Method: Apply k-core decomposition.

- Protocol: The network is pruned by repeatedly removing all nodes with a degree less than k, starting with k=1 and incrementing k until no nodes remain [20].

- Output: The genes removed at the highest value of k constitute the core of the network. These core genes are often critical for the network's stability [20].

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Gene Co-Expression Network

The following workflow outlines the key steps for constructing a gene co-expression network from RNA-Seq data, incorporating best practices for parameter optimization [20].

- Data Input and Normalization: Begin with an expression matrix from RNA-Seq data. Normalize the data to account for systematic variations using a method such as CPM (Counts Per Million), RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million), or VST (Variance Stabilizing Transformation) [20].

- Similarity Calculation: Compute the pairwise similarity between all genes. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) is a standard and effective choice for this step [20].

- Network Inference (Thresholding): Apply a sliding threshold to the similarity matrix to determine which connections are strong enough to be included as edges in the final network. This step is critical for optimizing network sparsity and biological relevance [20].

- Network Analysis: With the final network constructed (represented as an edge list), proceed to analyze its properties. This includes identifying communities, calculating centrality measures to find hub genes, and performing k-core decomposition to find the network's core [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools and Resources for Co-expression Network Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| GeCoNet-Tool | An all-in-one software package for constructing and analyzing gene co-expression networks from RNA-Seq data. | Handles data normalization, PCC calculation, and network analysis (community detection, centrality) [20]. |

| RNA-Seq Data | High-throughput data providing genome-wide expression patterns under various conditions. | The primary input for modern co-expression studies. Data is often sourced from public repositories like NCBI SRA [22]. |

| Normalization Method (e.g., VST, CPM) | Corrects for technical variations in RNA-Seq data (e.g., library size, composition) to make samples comparable. | Essential pre-processing step to ensure the accuracy of downstream similarity calculations [20]. |

| Similarity Measure (e.g., PCC) | A mathematical function that quantifies the co-expression relationship between two genes. | Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) is the most common measure for linear relationships [20]. |

| Community Detection Algorithm (e.g., Louvain) | Partitions the network into clusters (modules) of highly interconnected genes. | Useful for identifying groups of genes involved in related biological functions or pathways [20]. |

| Network Visualization Software (e.g., Gephi) | Provides interactive visualization of the network structure, often allowing for exploration based on calculated properties. | Recommended for gaining intuitive insights after initial analysis with GeCoNet-Tool [20]. |

Gene Co-expression Network Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between traditional WGCNA and the newer WGCHNA method?

Traditional WGCNA constructs networks based on pairwise gene relationships, which limits its ability to capture complex higher-order interactions among multiple genes. In contrast, WGCHNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Hypernetwork Analysis) uses hypergraph theory where samples are modeled as hyperedges connecting multiple gene nodes simultaneously. This allows WGCHNA to reveal multi-gene cooperative regulatory patterns that traditional pairwise methods might miss. WGCHNA has demonstrated superior performance in module identification and functional enrichment, particularly for processes like neuronal energy metabolism linked to Alzheimer's disease [23].

Q2: How can I handle missing values in gene co-expression data during network construction?

GeCoNet-Tool provides multiple options for processing gene co-expression data with missing values. You can choose to remove zeros, re-scale expression values by log2, or normalize columns by z-score, particularly when working with RNA-seq data. The tool calculates the number of paired elements between every pair of genes and uses this information to classify Pearson Correlation Coefficients into different intervals based on the number of paired conditions. This approach maintains data integrity even with significant missing values [20].

Q3: What factors should I consider when setting the soft threshold power parameter β?

The soft threshold power β is crucial for achieving scale-free topology. For most applications, a soft threshold of β = 7 (with R² > 0.9) has been shown to be effective. However, you should verify the scale-free fit index for your specific dataset. The choice of β represents a balance between biological meaning and statistical power—too low may not achieve scale-free topology, while too high may lose too many connections. Always check the scale-free topology fit index plot to guide your parameter selection [24].

Q4: How can I integrate multiple types of biological evidence for disease gene prioritization?

The PERCH framework provides a unified approach by quantitatively integrating multiple lines of evidence through Bayes factors. This includes variant deleteriousness (BayesDel), biological relevance assessment (BayesGBA), linkage analysis (BayesSeg), rare-variant association scores (BayesHLR), and variant quality scores (VQSLOD). Similarly, ModulePred integrates disease-gene associations, protein complexes, and augmented protein interactions using graph neural networks. Both approaches demonstrate that integrating heterogeneous information significantly improves prioritization accuracy [25] [26].

Q5: What community detection algorithms are most effective for gene co-expression modules?

Both Louvain and Leiden algorithms have proven effective for community detection in gene co-expression networks. The choice depends on your specific needs: Louvain is computationally efficient for large networks, while Leiden typically provides higher quality partitions by guaranteeing well-connected communities. Several tools including GeCoNet-Tool implement both algorithms, allowing users to compare results. The key is to ensure communities are highly connected internally while having sparse connections to other modules [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Network Construction Issues

Problem: Poor scale-free topology fit

- Symptoms: Low scale-free topology fit index (R² < 0.8), network doesn't follow power law distribution

- Solutions:

- Adjust soft threshold power β incrementally until R² > 0.9 is achieved

- Check data quality and preprocessing steps

- Consider using WGCHNA as an alternative, which uses hypergraph Laplacian matrices instead of traditional adjacency matrices [23]

Problem: Network too dense or too sparse

- Symptoms: Either too many connections (making biological interpretation difficult) or too few connected components

- Solutions:

- Use GeCoNet-Tool's sliding threshold approach with optimized parameters (α, η, λ, β)

- Adjust the cutoff value (typically between 0.005-0.02) to maintain majority of nodes connected while minimizing edges

- Execute the tool multiple times with different cutoff values to find optimal balance [20]

Module Detection Problems

Problem: Unstable module assignments

- Symptoms: Modules change significantly with small parameter changes, poor biological coherence

- Solutions:

Problem: Modules lack biological significance

- Symptoms: Poor functional enrichment results, modules don't correspond to known biological processes

- Solutions:

- Ensure proper data normalization and batch effect correction

- Use differential gene expression-based methods for modeling cell differentiation [15]

- Increase network specificity by using signed networks

- Validate with external datasets or experimental data

Disease Gene Prioritization Challenges

Problem: High false positive rates in candidate genes

- Symptoms: Many prioritized genes don't validate experimentally, poor replication in independent datasets

- Solutions:

- Use DEPICT framework which employs predicted gene functions and reconstituted gene sets to improve specificity [27]

- Implement PERCH's integrated approach combining multiple evidence types [25]

- Apply ModulePred's graph augmentation with L3 link prediction to address data incompleteness [26]

- Use text mining with random forest classification to extract disease-gene associations from literature with reported accuracy of 97.29% [28]

Problem: Incomplete molecular network data affecting predictions

- Symptoms: Missing protein-protein interactions, incomplete pathway annotations

- Solutions:

- Use ModulePred's graph augmentation with L3-based link prediction algorithms

- Integrate multiple data sources including protein complexes and augmented protein interactions

- Employ DEPICT's gene set reconstitution strategy that uses co-regulation patterns from 77,840 expression samples to predict gene functions [27]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Gene Co-expression and Prioritization Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| WGCHNA | Hypernetwork analysis | Captures higher-order gene interactions, uses hypergraph Laplacian matrix | Complex biological systems, multi-gene cooperation patterns [23] |

| GeCoNet-Tool | Network construction & analysis | Handles missing values, sliding threshold, multiple centrality measures | General co-expression analysis, community detection [20] |

| DEPICT | Gene prioritization | Uses reconstituted gene sets, tissue/cell type enrichment | GWAS follow-up, functional annotation [27] |

| PERCH | Variant interpretation | Integrates multiple Bayes factors, unified framework | NGS studies, clinical genetic testing [25] |

| ModulePred | Disease-gene prediction | Graph augmentation, functional modules integration | Network-based association prediction [26] |

| FastQC | Quality control | Per base sequence quality, adapter contamination check | NGS data preprocessing [29] |

| BWA | Sequence alignment | Burrows-Wheeler transform, accurate mapping | Whole-genome/exome sequencing [29] |

| GATK | Variant discovery | Local realignment, base quality recalibration | Variant calling, post-processing [29] |

Workflow Diagrams

Network Analysis and Prioritization Workflow

Gene Co-expression Network Construction Process

Performance Comparison Tables

Table: Comparison of Network Analysis Methods

| Method | Key Strength | Limitations | Optimal Use Case | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGCNA | Established, widely validated | Pairwise relationships only, computational efficiency issues | Standard co-expression analysis | Foundation for many published studies [23] |

| WGCHNA | Captures higher-order interactions | Newer method, less community experience | Complex multi-gene cooperation | Superior module identification and functional enrichment [23] |

| DC-WGCNA | Distance-correlation based | Similar limitations to WGCNA | Non-linear relationships | Improved for specific data types [23] |

| GeCoNet-Tool | Handles missing values well | Limited to Pearson correlation | Data with many missing values | Effective network construction from incomplete data [20] |

Table: Disease Gene Prioritization Tool Performance

| Tool | Approach | Integrated Data Types | Strengths | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEPICT | Reconstituted gene sets | Gene expression (77,840 samples), 14,461 gene sets | Not limited to genes with established functions | Outperformed MAGENTA, identified 2.5x more relevant gene sets [27] |

| PERCH | Bayes factors integration | Variant deleteriousness, biological relevance, linkage, association | Quantitative unification, VUS classification | More accurate than 13 other deleteriousness predictors [25] |

| ModulePred | Graph neural networks | Disease-gene associations, protein complexes, augmented PPIs | Handles data incompleteness, functional modules | Superior prediction performance [26] |

| Text Mining + RF | Random forest classification | Biomedical literature abstracts | Captures nuanced associations (Positive/Negative/Ambiguous) | 97.29% accuracy, identified thousands of disease genes [28] |

FAQ: Fundamental Differences and Applications

Q1: What is the fundamental biological difference between a PPI network and a gene co-expression network?

A PPI network represents physical or functional interactions between proteins within a cell. An edge indicates that two proteins have been experimentally observed or computationally predicted to interact, for instance, by forming a complex [30]. In contrast, a gene co-expression network represents statistical correlations in the expression levels of genes across different samples or conditions. An edge indicates that the expression patterns of two genes are coordinated, suggesting they may be involved in related biological processes or regulated by the same mechanism [31] [12] [30]. While a PPI network reveals the cell's functional machinery, a co-expression network reveals its regulatory state [30].

Q2: When should I use a co-expression network analysis over a PPI network analysis?

The choice depends on your research question and available data.

- Use a co-expression network to investigate transcriptional regulation, identify groups of genes (modules) that respond to a specific condition (e.g., disease, treatment), or to study non-model organisms where PPI data is scarce [31] [12]. It is ideal for generating hypotheses about gene function based on coordinated expression.

- Use a PPI network to study protein complexes, signaling pathways, or the physical mechanisms of cellular processes [12] [30]. It is best used when you have a defined set of proteins and want to understand their direct physical relationships.

Q3: Can a gene co-expression network be used to infer protein-protein interactions?

While co-expression can suggest that two gene products are active in the same context, it does not directly demonstrate a physical interaction [30]. Co-expressed genes may participate in the same pathway without their proteins ever touching. Therefore, co-expression data should be considered supportive, not definitive, evidence for PPIs and requires validation through specific interaction assays [30].

FAQ: Technical Construction and Data Interpretation

Q4: What are the primary data sources used to construct these networks?

The data inputs for these two network types are fundamentally different, as summarized below.

| Network Type | Primary Data Sources |

|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network | Experimental assays (e.g., Yeast Two-Hybrid, affinity purification-mass spectrometry), literature curation from databases, and computational predictions [31] [30]. |

| Gene Co-expression Network | High-throughput gene expression data, such as from microarrays or RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). The expression matrix (genes × samples) is used to calculate correlation coefficients [31] [12] [32]. |

Q5: How are the edges defined and weighted in each network type?

The definition and interpretation of edges is a major differentiator.

| Network Type | Edge Representation | Common Edge Weight / Metric |

|---|---|---|

| PPI Network | An interaction, which may be binary (present/absent) or weighted by interaction confidence [31] [32]. | Often unweighted. If weighted, typically a value from 0 to 1 indicating experimental confidence or a socio-affinity index [31]. |

| Gene Co-expression Network | The strength of co-expression between two genes [31] [12]. | A correlation coefficient (e.g., Pearson, Spearman) ranging from -1 to 1. The sign indicates a positive or negative correlation. Absolute values or signed transformations are also used [31] [32]. |

Q6: I've constructed a co-expression network, but it seems too dense. How do I filter out insignificant connections?

This is a crucial step. To reduce noise and focus on biologically meaningful connections, you must apply a threshold.

- Hard Thresholding: A strict cut-off is applied to the correlation coefficient. For example, you may choose to keep only edges where the absolute value of the correlation is ≥ 0.7 [12]. This creates a simpler, unweighted network.

- Soft Thresholding: This approach preserves the continuous nature of the correlation data but raises the correlation values to a power, which emphasizes stronger correlations and suppresses weaker ones. This is the method used in frameworks like WGCNA [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: My co-expression network from a public dataset has low connectivity and no clear modules.

- Potential Cause: The chosen correlation threshold may be too high, or the dataset itself may be too homogeneous.

- Solution: Systematically test lower correlation thresholds. If the dataset contains multiple conditions (e.g., control vs. treatment), ensure there is sufficient biological variation to drive co-expression patterns. Consider using a signed network approach or soft thresholding to better capture module structure [32].

Issue 2: After aligning co-expression networks from two species, the results show poor conservation.

- Potential Cause: The orthology mapping between species could be incomplete or inaccurate. Biological differences may also be real and significant.

- Solution: Verify the quality of the orthology maps used. Consider using local network alignment methods instead of global alignment, as they are designed to find conserved subnetructures even when the overall network conservation is low [31]. This can identify key conserved functional modules.

Issue 3: The hub genes in my co-expression network do not overlap with key drivers in a PPI network for the same condition.

- Potential Cause: This is an expected finding, not necessarily an error. Co-expression hub genes are often master regulators of transcription, while PPI hubs are proteins with many physical partners. They represent different levels of biological organization [12] [30].

- Solution: Interpret the results in their correct context. A co-expression hub suggests the gene is central to a coordinated transcriptional program. A PPI hub suggests the protein is a central connector in the protein interaction landscape. Their non-overlap can provide complementary biological insights.

Experimental Workflow for Co-expression Network Analysis

The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for constructing and analyzing a gene co-expression network, which can be directly compared to the data sources and goals of PPI network analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and computational tools for conducting co-expression network analysis.

| Item / Reagent | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| RNA-seq Dataset | The primary input data. Provides the gene expression matrix (genes × samples) from which correlations are calculated [12] [32]. |

| WGCNA R Package | A widely-used comprehensive tool for performing weighted correlation network analysis, including module detection and hub gene identification [12]. |

| Orthology Database (e.g., OrthoDB) | Provides ortholog mappings between species, which is essential for cross-species comparative network analyses [31]. |

| NetworkX Library (Python) | A standard Python library for the creation, manipulation, and study of complex networks. Useful for custom network analysis and visualization [12]. |

| Functional Annotation Database (e.g., GO, KEGG) | Used to perform enrichment analysis on co-expression modules, helping to assign biological meaning to groups of co-expressed genes [31] [12]. |

Practical Implementation: Data Processing, Normalization, and Network Construction Methods

Within co-expression analysis research, the integrity and accuracy of the gene expression matrix are paramount. This matrix, which represents the quantitative gene expression levels across all samples, serves as the fundamental input for constructing gene-gene co-expression networks [33]. The process of generating this matrix from raw sequencing data—the RNA-seq data processing pipeline—directly influences all downstream network analyses and biological interpretations. Optimizing this pipeline ensures that the resulting co-expression networks accurately reflect biological truth rather than technical artifacts [34]. This guide addresses specific, common challenges researchers encounter when establishing and troubleshooting their RNA-seq processing workflows to support robust network biology.

The following diagram illustrates the complete RNA-seq data processing pipeline, from raw sequencing reads to the final expression matrix, highlighting key stages where issues commonly occur.

Figure 1: RNA-seq data processing workflow from raw reads to expression matrix, highlighting critical stages and common troubleshooting points for co-expression analysis research.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

What is the impact of sequencing depth and read length on co-expression network reliability?

Problem: Inconsistent gene detection, particularly for lowly-expressed transcripts, leading to sparse or biased co-expression networks.

Solution: Optimize sequencing parameters based on your biological system and co-expression analysis goals.

- Sequencing Depth: For standard differential expression analysis in human or mouse models, 20-30 million reads per sample is generally recommended [35]. For de novo transcriptome assembly, aim for 100 million reads per sample [35].

- Read Length: Longer reads (75-150 bp) improve alignment accuracy, especially for transcript isoform resolution, which is crucial for understanding regulatory networks [36].

- Co-expression Consideration: Deeper sequencing improves detection of low-abundance transcripts that may play important regulatory roles in networks. However, excessive depth provides diminishing returns and increases costs [37].

How do I address high technical variation and batch effects in my expression matrix?

Problem: Technical artifacts from library preparation or sequencing overshadow biological signals, resulting in co-expression networks that reflect technical rather than biological relationships.

Solution: Implement rigorous experimental design and normalization techniques.

Experimental Design:

- Include a minimum of 3-5 biological replicates per condition to accurately estimate biological variance [38] [36].

- Randomize samples during library preparation and sequencing to avoid confounding technical batches with experimental conditions [38].

- Use multiplexing with barcodes to run samples from all experimental groups on each sequencing lane [36].

Technical Validation:

My alignment rates are poor. What steps should I take to improve them?

Problem: Low percentage of reads aligning to reference genome, reducing statistical power for co-expression detection.

Solution: Systematic quality control and appropriate reference selection.

Pre-alignment QC:

Alignment Strategy:

- Select splice-aware aligners (STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2) that can handle reads spanning intron-exon junctions [38] [37].

- Ensure you're using the most recent version of the reference genome and annotation [37].

- For ribosomal RNA contamination, consider whether poly-A selection or rRNA depletion is more appropriate for your study system [35].

How should I handle normalization to ensure comparable expression values across samples?

Problem: Inappropriate normalization introduces systematic biases that distort co-expression relationships.

Solution: Select normalization methods appropriate for your data structure and research question.

Standard Approaches:

- Methods like TPM (Transcripts Per Million) and quantile normalization account for library size differences and distributional variations [39].

- For differential expression analysis, tools like edgeR and DESeq2 implement sophisticated normalization procedures that model raw count data using a negative binomial distribution [39] [38].

Co-expression Specific Considerations:

- Consistency in normalization approach across all samples is critical for network inference.

- Be cautious when merging publicly available datasets, as batch effects between studies can severely impact co-expression networks [33].

What are the best practices for managing PCR artifacts and duplicates in RNA-seq data?

Problem: PCR amplification biases during library preparation distort true expression levels, particularly affecting high-abundance transcripts.

Solution: Strategic use of molecular barcodes and duplicate handling.

UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Integration:

- Incorporate UMIs during library preparation to molecularly tag each original cDNA fragment [35].

- Use bioinformatics tools (fastp, umis tools, umi-tools) for UMI extraction and deduplication [35].

- UMIs are particularly valuable for low-input samples and deep sequencing projects (>50 million reads/sample) [35].

Duplicate Handling:

- Note that not all duplicates are PCR artifacts; some occur naturally from highly expressed transcripts [36].

- Without UMIs, conservative duplicate removal may discard valid biological signals.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and tools for RNA-seq pipeline implementation and troubleshooting

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Mix | External RNA controls with known concentrations to assess technical variation [35] | Added during RNA extraction; useful for evaluating sensitivity, dynamic range, and normalization |

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) | Molecular barcodes to distinguish PCR duplicates from original molecules [35] | Critical for low-input protocols and deep sequencing; reduces amplification biases |

| Poly-A Selection | Enrichment for mRNA by targeting polyadenylated transcripts [35] | Standard for eukaryotic mRNA sequencing; not suitable for non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| rRNA Depletion | Removal of ribosomal RNA to increase sequencing depth of other RNA species [35] | Essential for bacterial transcripts, non-coding RNA studies, and degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) |

| Strand-Specific Kits | Preservation of strand orientation during library preparation [35] | Important for identifying antisense transcription and accurately assigning reads to genes |

RNA-seq Parameter Optimization Table

Table 2: Key experimental parameters and their impact on downstream co-expression analysis

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Impact on Co-expression Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | 20-30M reads (standard); 100M reads (de novo) [35] | Higher depth improves low-abundance transcript detection; affects network connectivity |

| Biological Replicates | Minimum 3-5 per condition [38] [36] | Essential for estimating biological variance; improves network robustness |

| Read Type | Paired-end for novel isoform detection [36] | Better junction resolution improves transcript quantification accuracy |

| Read Length | 75-150 bp, depending on application [36] | Longer reads improve alignment, especially for isoform resolution |

| Alignment Tool | Splice-aware (STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2) [38] [37] | Critical for accurate mapping across exon junctions; affects all downstream analysis |

Workflow Integration for Co-expression Analysis

The relationship between RNA-seq processing and co-expression network construction involves specific considerations for network biology research. The following diagram illustrates how parameter optimization at each RNA-seq stage influences final network characteristics.

Figure 2: Integration of RNA-seq processing parameters with co-expression network analysis, highlighting the optimization feedback cycle essential for robust biological insights.

Recent research indicates that the choice of network analysis strategy has a stronger impact on biological interpretation than the specific network creation method [34]. Furthermore, combined time point modeling often provides more stable results than single time point approaches when studying dynamic processes like cell differentiation [34]. These findings underscore the importance of considering downstream network applications when designing RNA-seq processing pipelines.

In the analysis of RNA-Seq data for gene co-expression networks, normalization is not merely a preprocessing step but a critical analytical decision that directly impacts the network's biological validity. Normalization methods are primarily categorized into within-sample and between-sample techniques, each designed to correct for specific types of technical biases. Within-sample normalization enables the comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample, while between-sample normalization allows for the comparison of the same gene's expression across different samples. The choice between these methods, or their combination, hinges on the specific goals of the co-expression analysis and the nature of the experimental data. Errors in normalization can lead to inflated false positives in downstream analyses, including the construction of co-expression networks that do not accurately reflect true biological relationships [40]. This guide provides a structured framework to help researchers navigate these choices, troubleshoot common issues, and optimize their normalization strategies for robust co-expression network analysis.

Understanding the Normalization Landscape

What is the fundamental difference between within-sample and between-sample normalization?

Within-Sample Normalization adjusts for technical factors that affect the comparison of read counts between different genes within a single sample. The primary factors it accounts for are:

- Transcript Length: Longer genes tend to have more reads mapped to them than shorter genes at the same expression level. Normalization methods like TPM and FPKM/RPKM correct for this bias [41] [22].

- Sequencing Depth: This correction ensures that the total number of reads in a sample does not bias the expression level of a gene within that sample. CPM is a simple method that corrects for this factor alone [41].

- The goal is to produce expression values (e.g., TPM, FPKM) that allow for a meaningful comparison of the relative abundance of different transcripts within the same sample [41].

Between-Sample Normalization adjusts for technical factors that affect the comparison of the same gene across different samples. The key factors it addresses are:

- Sequencing Depth: Differences in the total number of sequenced reads (library size) between samples [40] [42].

- RNA Composition: This is a critical factor that arises when a few genes are highly expressed in one condition, altering the proportion of reads available for all other genes. If not corrected, this can create the false appearance of differential expression for non-differentially expressed genes [40] [43].

- Methods like TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) and DESeq2's median of ratios are specifically designed for between-sample normalization and account for these compositional biases [41] [43].

How do I choose the right unit of expression for my analysis?

The table below summarizes the characteristics of common expression units to guide your selection.

Table 1: Common Expression Units and Their Appropriate Use Cases

| Method | Full Name | Accounts For | Primary Use Case | Not Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Counts Per Million [41] | Sequencing Depth | Comparing gene counts between replicates of the same sample group [43]. | Within-sample comparisons; DE analysis [43]. |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million [41] | Sequencing Depth & Gene Length | Comparing gene expression within a single sample or between samples of the same group [41] [43]. | Direct between-sample DE analysis without additional between-sample normalization [44]. |

| FPKM/ RPKM | Fragments/Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads [41] | Sequencing Depth & Gene Length | Comparing gene expression within a single sample [41] [43]. | Comparing expression of the same gene between samples; DE analysis [44] [43]. |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values [41] | Sequencing Depth & RNA Composition [43] | Gene count comparisons between and within samples; DE analysis [43]. | - |

| DESeq2's Median of Ratios | - | Sequencing Depth & RNA Composition [43] | Gene count comparisons between samples and for DE analysis [43]. | Within-sample comparisons [43]. |

What is the recommended workflow for co-expression network analysis?

For constructing gene co-expression networks (GCNs) from RNA-seq data, comprehensive benchmarking studies suggest that between-sample normalization has the biggest impact on network accuracy. One large-scale study found that using counts adjusted by size factors (a between-sample method) produced networks that most accurately recapitulated known functional relationships between genes [45].

A typical, robust workflow involves multiple stages of processing. The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and common method choices at each stage for building an accurate co-expression network.

Diagram: A recommended multi-stage workflow for constructing co-expression networks from RNA-seq data, showing key normalization and transformation stages.

Troubleshooting Common Normalization Issues

My co-expression network seems biologically unreliable. Could normalization be the cause?

Yes, this is a common issue. The accuracy of normalization is fundamental to a biologically meaningful co-expression network. If your network performance is poor, consider these points:

- Violation of Assumptions: Many between-sample methods, like TMM, assume that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed. If your experiment involves a global shift in expression (e.g., most genes are up-regulated in one condition), this assumption is violated, and the normalization will be incorrect, leading to a faulty network [40].

- Prioritize Between-Sample Normalization: Benchmarking studies specifically for co-expression have shown that the choice of between-sample normalization method has a larger impact on final network accuracy than within-sample normalization [45]. Ensure you are using a robust between-sample method like TMM or CTF (Counts adjusted with TMM factors) [45].

- Check for Compositional Biases: If your experiment has a condition with a few very highly expressed genes, this can skew the library and create false co-expression signals for other genes. Methods like TMM and DESeq2's median of ratios are designed to be robust to such imbalances [40] [43].

Can I use TPM values for between-sample comparison in a co-expression network?

This is a nuanced but critical question. While TPM is a valuable unit, it is not sufficient for between-sample comparison on its own [44]. TPM performs within-sample normalization, correcting for gene length and sequencing depth within each sample. However, it does not account for RNA composition biases between samples [44] [43].

- The Problem: If you calculate TPM for each sample and then directly compare them, differences in the expression of a few highly abundant genes in one sample can make it seem like all other genes are down-regulated, which is a technical artifact [40].

- The Solution: For co-expression analysis, which inherently involves comparing samples, you must apply an additional between-sample normalization method. A recommended practice is to use a between-sample normalization method (e.g., TMM, median of ratios) on the raw or length-adjusted counts before calculating correlation coefficients for the network [45] [44].

When should I consider using spike-in controls for normalization?

Spike-in normalization is a specific technique that uses exogenous RNA transcripts added at known concentrations to each sample.

- Ideal Use Case: It is particularly valuable when you are interested in preserving and studying biological differences in the total RNA content of individual cells or samples [42]. For example, in single-cell RNA-seq studies of T cell activation, where overall RNA content increases with stimulation, spike-in controls can accurately normalize for technical biases without masking this biological change [42].

- Key Assumption: This method assumes that the same amount of spike-in RNA was added to each cell and that it responds to technical biases in the same way as endogenous genes [42].

- When Not to Use: If the above conditions are not met or spike-ins were not included in the experiment, reliance on robust analytical methods like deconvolution (e.g., in

scran) or TMM is recommended.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA-Seq Normalization

| Name | Type | Brief Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Controls | Wet-lab Reagent | Exogenous RNA sequences added at known concentrations to each sample to track technical variability and enable absolute normalization [42]. |

| DESeq2 | R Package / Software | Provides the "median of ratios" method for between-sample normalization, robust to RNA composition biases. Uses raw counts as input [43]. |

| edgeR | R Package / Software | Provides the "Trimmed Mean of M-values" (TMM) method for between-sample normalization, also robust to composition biases [41] [43]. |

| scran | R Package / Software | Uses a deconvolution method for single-cell RNA-seq data, pooling cells to improve size factor estimation and handle composition biases [42]. |

| Gold Standard Gene Sets | Computational Resource | Curated sets of genes (e.g., from Gene Ontology) with known functional relationships. Used to benchmark and evaluate the accuracy of co-expression networks [45]. |

| Recount2 Database | Data Resource | A collection of thousands of uniformly processed RNA-seq datasets, invaluable for large-scale benchmarking studies of normalization methods and network construction [45]. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Your Normalization Strategy

To empirically determine the optimal normalization method for your specific co-expression study, follow this benchmarking protocol.

- Data Preprocessing: Start with a raw count matrix from your RNA-seq experiment. Apply lenient filters to remove lowly expressed genes, keeping as many genes and samples as possible for the analysis [45].

- Define a Gold Standard: Compile a set of known, biologically validated gene-gene relationships. This is often derived from databases like Gene Ontology (GO) for biological processes. This set will be your benchmark for accuracy [45].

- Construct Multiple Workflows: Test various combinations of normalization methods. A comprehensive test should include:

- Within-sample: CPM, TPM, RPKM, or none.

- Between-sample: TMM, CTF (counts adjusted by TMM factors), UQ (Upper Quartile), QNT (Quantile), or DESeq2's median of ratios.

- Network Transformation: WTO (Weighted Topological Overlap) or CLR (Context Likelihood of Relatedness) [45].

- Build and Evaluate Networks: For each workflow combination, construct a co-expression network. Evaluate each network by measuring how well the top-ranked gene pairs in your network recapitulate the pairs in your gold standard. Use metrics like the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (auPRC), which is more informative than auROC for this imbalanced problem [45].

- Select the Best Performer: Choose the normalization workflow that yields the highest auPRC against your gold standard, indicating it most accurately captures true biological relationships.

This structured approach ensures your choice of normalization is data-driven and optimized for your specific research context in co-expression analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Which normalization method should I use for building gene co-expression networks from RNA-seq data?

For constructing gene co-expression networks, workflows that use between-sample normalization methods like TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) or RLE (Relative Log Expression, used in DESeq2) generally produce the most accurate networks. A comprehensive benchmarking study tested 36 different workflows and found that between-sample normalization, particularly methods that adjust counts using size factors (like TMM), had the biggest impact on accurately recapitulating known functional relationships between genes [46]. It is recommended to use these methods rather than within-sample methods like TPM or RPKM for this specific application [46] [47].

2. I have performed a differential expression analysis and now want to visualize my results on a PCA plot. Should I use the raw counts?

No, for visualization purposes like PCA or heatmaps, you should not use raw counts. Raw counts are suitable for differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR, but they are not ideal for visualization because the high variance of lowly expressed genes can dominate the results [48]. Instead, it is recommended to use variance-stabilizing transformations such as VST (Variance Stabilizing Transformation) or RLOG (Regularized Logarithm) [48]. These methods stabilize the variance across the mean, making your visualizations more reliable.

3. Why is my TPM-normalized data from a public database showing high variability between replicate samples?

This is a common issue. Methods like TPM, RPKM, and FPKM are within-sample normalization techniques. They correct for sequencing depth and gene length, but a major limitation is that they do not account for RNA composition bias [47] [41]. This bias occurs when a few highly expressed genes consume a large fraction of the sequencing reads in one sample, making the counts of all other genes appear smaller in comparison. For robust comparisons across samples, especially when using data from different sources or with varying library compositions, a between-sample method like TMM or RLE (from DESeq2) is necessary [47].

4. What is the key practical difference between TPM and RPKM/FPKM?

The key difference lies in the order of operations, which makes TPM more comparable between samples. Both methods correct for sequencing depth and gene length. However:

- RPKM/FPKM: The total mapped reads are scaled to per million, and then divided by gene length in kilobases. The sum of all RPKM/FPKM values in a sample will not be constant.

- TPM: The reads are first normalized per kilobase of gene length (per kilobase). Then, these length-normalized reads are summed, and each value is divided by this total and multiplied by a million [41]. Consequently, the sum of all TPM values in every sample is always 1 million. This makes it easier to compare the relative abundance of a transcript across different samples.

5. How do I know if my chosen normalization method is working well for my specific dataset?

A recommended practice is to evaluate the performance of different normalization methods on your own data. You can follow this workflow [47]:

- Normalize the Data: Apply several relevant normalization methods to your dataset.

- Evaluate Bias and Variance: Calculate the bias and variance of housekeeping genes (genes expected to be stably expressed) after normalization. Methods that result in lower bias and variance for these genes are generally better.

- Check for Common DEGs: Perform differential expression analysis and see how many differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are consistently identified across different normalization methods.

- Assess Classification Power: Use discriminant analysis to see how well the results from each method can classify samples into their known groups.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem Scenario | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability between biological replicates in clustering analysis. | Using a within-sample normalization method (e.g., TPM, FPKM) that does not correct for RNA composition bias [47]. | Re-normalize the raw count data using a between-sample method like TMM or RLE (DESeq2) before performing clustering. |

| Poor performance in cross-study phenotype prediction. | Significant heterogeneity and batch effects between datasets are not accounted for by standard normalization [49]. | Apply batch correction methods such as ComBat or Limma after initial between-sample normalization to remove these technical variations [49]. |

| Co-expression network fails to recapitulate known biological pathways. | Inappropriate normalization choice for network construction. Between-sample effects have the biggest impact on network accuracy [46]. | Use a workflow that employs a between-sample normalization method like TMM or CTF (Counts adjusted with TMM factors) for building the co-expression network [46]. |

| Differential expression analysis using a DGE tool (DESeq2/edgeR) returns an error related to normalization. | Inputting pre-normalized data (e.g., TPM, FPKM) instead of raw counts. These tools perform their own internal normalization [48]. | Always provide raw read counts as input to DESeq2, edgeR, or similar packages. They incorporate sophisticated normalization steps (RLE, TMM) into their statistical models. |

Comparison of Normalization Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of the mentioned normalization methods.

| Method | Corrects for Sequencing Depth | Corrects for Gene Length | Corrects for Library Composition | Primary Use Case & Suitability for Co-expression Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Yes | No | No | Within-sample comparisons. Not recommended for DE or cross-sample co-expression analysis [48]. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | Within-sample gene comparison. Not suitable for cross-sample analysis due to composition bias [41]. Poorer performance in co-expression networks [46]. |

| TPM | Yes | Yes | Partial | An improvement over RPKM/FPKM for cross-sample comparison, but still suffers from composition bias [50]. Not ideal for co-expression networks [46]. |

| TMM | Yes | No | Yes | Between-sample comparison and DE analysis. Highly recommended for co-expression networks; accurately captures functional relationships [46] [51]. |

| UQ (Upper Quartile) | Yes | No | Partial (assumes the upper quartile is non-DE) | Between-sample comparison. Can be outperformed by TMM and RLE, especially when the upper quartile is not stable [52]. |

| RLE (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Between-sample comparison and DE analysis. Similar to TMM in performance and is highly recommended for co-expression network analysis [46] [51]. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Normalization for Co-expression Analysis

This protocol is adapted from comprehensive benchmarking studies to evaluate normalization methods for building gene co-expression networks [46].

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Obtain raw RNA-seq count data from a source like recount2, which includes large consortium data (e.g., GTEx) and smaller, heterogeneous datasets from SRA [46].

- Apply lenient filters to retain as many genes and samples as possible. A common filter is to keep genes with at least a few reads across a minimum number of samples.

2. Application of Normalization Workflows:

- Test a combination of methods. The benchmark should include:

- Within-sample: CPM, TPM.

- Between-sample: TMM, UQ, and their count-adjusted variants (CTF, CUF), and RLE.

- Network Transformation: Weighted Topological Overlap (WTO), Context Likelihood of Relatedness (CLR).

- Construct a co-expression network for each workflow, where nodes are genes and edges represent co-expression similarity.

3. Network Evaluation Using Gold Standards:

- Create a "gold standard" of known gene functional relationships, such as genes co-annotated to the same Biological Process in Gene Ontology [46].

- For a more refined analysis, create tissue-aware gold standards by subsetting to genes known to be expressed in specific tissues.

- Evaluate how well each co-expression network recapitulates these known relationships. Metrics that account for the high imbalance between true and false pairs (like precision-recall curves) are often more informative than simple correlation [46].

4. Analysis and Recommendation:

- Analyze the aggregate performance of all workflows across many datasets.

- Identify which normalization steps (e.g., between-sample normalization) have the largest impact on accuracy.

- Provide a robust recommendation for a normalization workflow based on the empirical results, such as using TMM or RLE normalization for co-expression networks.

Normalization Method Relationships and Workflow

This diagram illustrates the relationship between different normalization methods and a general workflow for analysis.

| Item | Function in Analysis | Example Tools / Packages |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Count Matrix | The fundamental input data for between-sample normalization and differential expression analysis. | HTSeq-count, featureCounts, Salmon, Kallisto [50]. |

| Between-Sample Normalization Algorithms | Corrects for technical variations like sequencing depth and library composition to enable accurate cross-sample comparisons. | TMM (in edgeR), RLE/DESeq2 (in DESeq2), TMMwzp, UQ [48]. |

| Variance Stabilizing Methods | Transform normalized count data to stabilize variance across the dynamic range for reliable visualization (PCA, heatmaps). | VST, RLOG (in DESeq2), VOOM (in Limma) [48]. |

| Batch Correction Tools | Remove unwanted technical variation (batch effects) when integrating datasets from different studies or sequencing runs. | ComBat, Limma's removeBatchEffect [49] [41]. |

| Co-expression Network Construction & Evaluation | Build networks from normalized expression data and evaluate their quality against known biological standards. | WGCNA (for WTO), CLR; Evaluation against Gene Ontology [46]. |