Network-Based Biomarker Evaluation: From Discovery to Clinical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the performance of network-based biomarkers, a transformative approach in precision oncology and drug development.

Network-Based Biomarker Evaluation: From Discovery to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the performance of network-based biomarkers, a transformative approach in precision oncology and drug development. It explores the foundational principles that establish why biological networks are crucial for capturing complex disease mechanisms, moving beyond traditional single-marker analyses. The content details cutting-edge methodological frameworks, including graph neural networks and multi-omics integration, and their practical applications in patient stratification and treatment prediction. Furthermore, it addresses critical challenges in model optimization, data heterogeneity, and computational scalability. Finally, the article synthesizes robust validation strategies and comparative performance metrics, offering researchers and drug development professionals a holistic guide to developing, troubleshooting, and validating robust network-based biomarker signatures for improved clinical outcomes.

The Power of Networks: Why Biology Demands a Connected View of Biomarkers

The field of biomarker discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving beyond the limitations of single-marker approaches toward sophisticated network-based frameworks. Traditional biomarker discovery has primarily focused on identifying individual molecules with statistical correlation to disease states, but this method has faced significant challenges in clinical translation. The remarkably low success rate—with only about 0.1% of potentially clinically relevant cancer biomarkers progressing to routine clinical use—highlights the critical inadequacies of conventional approaches [1]. Similarly, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved fewer than 30 molecular biomarkers in a recent compilation, demonstrating the translational bottleneck in the field [2].

This article examines the systematic limitations of traditional biomarker discovery methods and objectively evaluates the emerging paradigm of network-based approaches. By comparing performance metrics, methodological frameworks, and clinical applicability, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of how network-based biomarker strategies address the critical challenges of sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility that have plagued single-marker approaches. The evolution toward network-based methodologies represents more than a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental reimagining of disease as a systems-level phenomenon requiring correspondingly sophisticated diagnostic and prognostic tools.

The Fundamental Limitations of Single-Marker Approaches

Analytical and Clinical Shortcomings

Traditional single-marker approaches suffer from several interconnected limitations that restrict their clinical utility. Individual biomarkers often lack the sensitivity and specificity required for accurate disease detection and classification, particularly for complex, multifactorial diseases [3]. For instance, while CA125 demonstrates sensitivity for ovarian cancer detection, it lacks sufficient specificity to distinguish malignant from benign conditions, resulting in false positives and unnecessary interventions [2]. This limitation stems from biological reality: diseases rarely involve isolated molecular abnormalities but rather manifest as perturbations across interconnected cellular pathways and networks.

The reductionist perspective of single-marker approaches fails to capture the complex pathophysiology of diseases, especially in oncology where tumors utilize multiple signaling pathways that can bypass targeted interventions [3]. Research indicates that many high-incidence diseases such as cardiac-cerebral vascular disease, cancer, and diabetes have a multifactorial basis that cannot be adequately captured by measuring individual proteins [4]. This fundamental mismatch between biological complexity and analytical simplicity explains why even promising individual biomarkers frequently fail validation in independent cohorts or demonstrate insufficient predictive power for clinical deployment.

Validation and Standardization Challenges

The path from discovery to clinical implementation presents substantial obstacles for traditional biomarkers. Reproducibility issues frequently arise due to variations in sample collection, handling, storage, and profiling techniques that can significantly influence protein profiles obtained by any method [3] [5]. A lack of standardized protocols for measuring and reporting biomarkers makes it difficult to compare data across studies and establish consistent clinical thresholds [5]. Furthermore, analytical validation requires demonstrating accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility—a process that is both time-consuming and costly [5].

The challenge extends to clinical relevance, where a biomarker must not only be measurable and reproducible but also provide meaningful insights into patient care [5]. Many candidates fail at the stage of clinical validation, where researchers must assess the biomarker's ability to predict clinical outcomes consistently [2] [1]. Additionally, the economic considerations of biomarker validation can be prohibitive, particularly when longitudinal studies spanning years are required to establish clinical utility [5]. These multifaceted challenges create a formidable barrier between promising discoveries and clinically implemented tools.

Network-Based Frameworks: A Systems Approach to Biomarker Discovery

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Principles

Network-based biomarker discovery represents a paradigm shift from reductionist to systems-level thinking in diagnostic development. This approach operates on the fundamental premise that diseases arise from perturbations in interconnected molecular networks rather than isolated molecular abnormalities. The theoretical foundation rests on understanding that "therapeutic effect of a drug propagates through a protein-protein interaction network to reverse disease states" [6]. By mapping these complex interactions, network-based methods can identify predictive signatures that reflect the underlying systems pathology.

The core methodological principle involves integrating multi-omics data with protein-protein interaction networks, co-expression patterns, and phenotypic associations to identify robust biomarker signatures [7]. Unlike traditional approaches that evaluate biomarkers in isolation, network-based methods consider functional and statistical dependencies between molecules, leveraging their collective behavior as a more reliable indicator of disease state [7]. This methodology aligns with the understanding that biological systems function through complex, non-linear interactions that cannot be captured by analyzing individual components in isolation.

Key Network-Based Methodologies and Platforms

Several sophisticated computational frameworks have emerged to implement network-based biomarker discovery. The table below compares three prominent platforms and their methodological approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Network-Based Biomarker Discovery Platforms

| Platform Name | Core Methodology | Network Data Sources | Validation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| NetRank | Random surfer model integrating protein connectivity with phenotypic correlation | STRINGdb, co-expression networks (WGCNA) | AUC 90-98% across 19 cancer types [7] |

| PRoBeNet | Prioritizes biomarkers based on therapy-targeted proteins, disease signatures, and human interactome | Protein-protein interaction networks | Significantly outperformed models using all genes or random genes with limited data [6] |

| MarkerPredict | Machine learning (Random Forest, XGBoost) with network motifs and protein disorder | Three signaling networks (CSN, SIGNOR, ReactomeFI) | LOOCV accuracy 0.7-0.96 across 32 models [8] |

These platforms demonstrate how network-based approaches leverage different aspects of biological organization but share the common principle that network topology and interactions provide crucial information beyond individual molecular concentrations.

Performance Comparison: Single Markers Versus Network-Based Signatures

Diagnostic Accuracy and Predictive Performance

Network-based biomarker signatures consistently demonstrate superior performance compared to traditional single-marker approaches across multiple disease contexts. The table below summarizes quantitative performance comparisons drawn from validation studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between Single and Network-Based Biomarkers

| Metric | Single-Marker Approach | Network-Based Approach | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Accuracy | Limited (e.g., CA125 alone insufficient for ovarian cancer) [2] | F1 score of 98% for breast cancer classification [7] | >30% increase in accuracy |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | Moderate (individual biomarkers often <80%) [2] | 90-98% across 19 cancer types [7] | 10-20% absolute improvement |

| Cross-Validation Performance | Often overfitted, fails in independent validation | LOOCV accuracy of 0.7-0.96 for MarkerPredict [8] | Enhanced generalizability |

| Panel Size | Single molecule | Typically 50-100 molecules [7] | Captures pathway complexity |

The performance advantage of network-based approaches is particularly evident in their ability to maintain high accuracy across diverse cancer types. NetRank achieved AUC scores above 90% for 16 of 19 cancer types evaluated from TCGA data, demonstrating remarkable generalizability [7]. This consistent high performance across diverse biological contexts suggests that network-based signatures capture fundamental disease mechanisms rather than tissue-specific epiphenomena.

Clinical Utility and Robustness

Beyond technical performance metrics, network-based biomarkers offer enhanced clinical utility and practical implementation advantages. They demonstrate superior robustness to data limitations, with PRoBeNet significantly outperforming conventional models especially when data were limited [6]. This characteristic is particularly valuable in clinical contexts where sample sizes may be constrained. Additionally, network-based approaches show reduced vulnerability to technical variability, as they focus on relational patterns rather than absolute concentrations of individual molecules.

The biological interpretability of network biomarkers represents another significant advantage. Functional enrichment analysis of NetRank-derived breast cancer signatures revealed 88 enriched terms across 9 relevant biological categories, compared to only nine terms when selecting proteins based solely on statistical associations [7]. This enhanced biological plausibility strengthens confidence in the clinical relevance of discovered signatures and facilitates mechanistic insights that can guide therapeutic development.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Network Biomarker Discovery Workflow

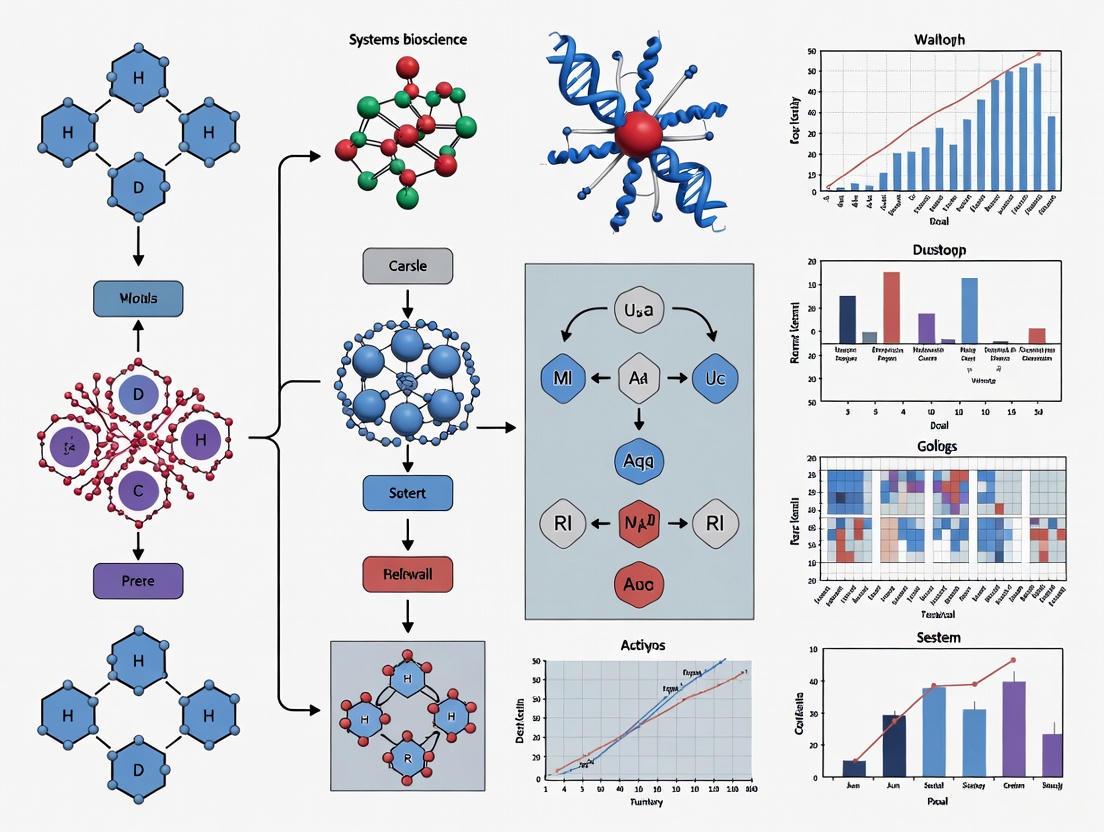

The experimental workflow for network-based biomarker discovery follows a systematic process that integrates multi-modal data sources. The diagram below illustrates the key stages:

Diagram 1: Network Biomarker Discovery Workflow

This workflow begins with multi-omics data integration, combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles to create a comprehensive molecular portrait [9]. The network construction phase utilizes established biological databases such as STRINGdb, HPRD, and KEGG, or computationally derived co-expression networks [7]. Biomarker ranking employs specialized algorithms like NetRank or machine learning approaches that consider both network properties and phenotypic associations [8] [7]. The final validation stage assesses clinical utility using standardized performance metrics and independent sample sets.

Case Study: NetRank Implementation and Validation

The NetRank algorithm provides a concrete example of network-based biomarker discovery in action. The methodology employs a random surfer model inspired by Google's PageRank algorithm, formalized as:

$$\begin{aligned} rj^n= (1-d)sj+d \sum{i=1}^N \frac{m{ij}r_i^{n-1}}{degree^i} \text{,} \quad 1 \le j \le N \end{aligned}$$

Where $r$ represents the ranking score of a node (gene), $d$ is a damping factor defining the relative weights of connectivity and statistical association, $s$ is the Pearson correlation coefficient of the gene with the phenotype, and $m$ represents connectivity between nodes [7].

In a comprehensive validation study encompassing 19 cancer types and 3,388 patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas, NetRank demonstrated exceptional performance. The algorithm achieved area under the curve (AUC) values above 90% for most cancer types using compact signatures of approximately 100 biomarkers [7]. The implementation showed strong correlation between different network sources (STRINGdb versus co-expression networks) with Pearson's R-value of 0.68, indicating methodological robustness [7].

Successful implementation of network-based biomarker discovery requires specialized computational tools and biological resources. The table below details essential components of the network biomarker research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Network Biomarker Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Interaction Databases | STRINGdb, HPRD, KEGG | Provide curated protein-protein interaction data for network construction [4] [7] |

| Omics Data Repositories | TCGA, CIViC, DisProt | Supply genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data for analysis [8] [7] [10] |

| Computational Platforms | NetRank, PRoBeNet, MarkerPredict | Implement specialized algorithms for network-based biomarker discovery [8] [6] [7] |

| Validation Technologies | LC-MS/MS, Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) | Provide advanced sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities for biomarker verification [1] |

| IDP Databases | DisProt, AlphaFold, IUPred | Characterize intrinsically disordered proteins with potential biomarker utility [8] |

The integration of these resources enables a comprehensive pipeline from network construction to experimental validation. Particularly valuable are multiplexed validation technologies like Meso Scale Discovery (MSD), which offer up to 100 times greater sensitivity than traditional ELISA and significantly reduce per-sample costs from approximately $61.53 to $19.20 for a four-biomarker panel [1]. This economic advantage makes large-scale validation studies more feasible within typical research budgets.

The transition from single-marker to network-based approaches represents a fundamental maturation of biomarker science that aligns with our understanding of disease as a systems-level phenomenon. Network-based biomarkers address the critical limitations of traditional approaches by capturing the complex, interconnected nature of biological processes, resulting in substantially improved performance with AUC values frequently exceeding 90% across diverse disease contexts [7]. The enhanced biological interpretability of network-derived signatures, with functional enrichment scores nearly ten times higher than single-marker approaches, provides deeper insights into disease mechanisms and strengthens clinical confidence [7].

Future directions in network biomarker development will likely incorporate dynamic health indicators through longitudinal monitoring, strengthen integrative multi-omics approaches, and leverage edge computing solutions for low-resource settings [9]. Furthermore, the integration of large language models for extracting biomarker information from unstructured clinical text shows promise for enhancing clinical trial matching and accelerating precision medicine implementation [10]. As these methodologies continue to evolve, network-based biomarker discovery will play an increasingly central role in realizing the promise of precision medicine, enabling earlier disease detection, more accurate prognosis, and optimal therapeutic selection for individual patients.

In biology, a network provides a powerful mathematical framework for representing complex systems as sets of binary interactions or relations between various biological entities [11]. This approach allows researchers to model and analyze the intricate organization and dynamics of biological processes, from molecular interactions within a cell to species relationships within an ecosystem. Networks effectively capture the fundamental principle that biological function often emerges not from isolated components, but from their complex patterns of interaction. The core components of any network are nodes (the entities or objects) and edges (the connections between them) [11]. In biological contexts, these components can represent a vast array of elements—proteins, genes, metabolites, neurons, or even entire species—connected by physical binding, regulatory relationships, or ecological interactions. The topology, or the specific arrangement of nodes and edges within a network, determines its structural properties and, consequently, its functional capabilities [12]. Analyzing topological properties helps researchers identify relevant sub-structures, critical elements, and overall network dynamics that would remain hidden if individual components were examined separately [12].

Fundamental Building Blocks: Nodes and Edges

Nodes: The Biological Entities

Nodes represent the fundamental biological entities within a network. Their identity depends entirely on the network type and the biological question under investigation. In protein-protein interaction networks, nodes represent individual proteins [11]. In gene regulatory networks, nodes typically represent genes or their products (mRNAs, proteins) [13] [11]. In metabolic networks, nodes are the small molecules (substrates, intermediates, and products) involved in biochemical reactions [11]. In ecological food webs, nodes represent different species within an ecosystem [11]. The same biological entity can appear as different node types across multiple networks, reflecting its participation in diverse biological processes.

Edges: The Biological Relationships

Edges represent the interactions, relationships, or influences between biological entities. These connections can be directed (indicating a causal or directional relationship, such as gene A regulating gene B) or undirected (indicating association without directionality, such as physical binding between proteins) [13] [11]. In gene regulatory networks, edges are typically directed and can represent either activation or inhibition of gene expression [11]. In protein-protein interaction networks, edges are usually undirected, representing physical binding between proteins [11]. In signaling networks, edges often represent biochemical reactions like phosphorylation that transmit signals [11]. In food webs, directed edges represent predator-prey relationships [11]. Unlike social networks where connections can be directly observed, edges in many biological networks (particularly molecular networks) often must be carefully estimated from experimental data or covariates as a first step in network reconstruction [13].

Key Topological Properties of Biological Networks

Topology—the way nodes and edges are arranged within a network—determines its structural characteristics and functional capabilities. Several key topological properties are essential for analyzing biological networks [12]:

- Degree: The degree of a node is the number of edges that connect to it. It is a fundamental parameter that influences other characteristics, such as the centrality of a node. In directed networks, nodes have two degree values: in-degree (edges coming into the node) and out-degree (edges coming out of the node). The degree distribution of all nodes helps define whether a network has a scale-free property [12].

- Shortest Paths: The shortest path represents the minimal number of edges that must be traversed to travel between any two nodes. This property models how information, signals, or effects might flow through a network and is particularly relevant in biological signaling and neural networks [12].

- Scale-Free Property: Many biological networks are scale-free, meaning most nodes have few connections, while a small number of nodes (called hubs) have a very high degree. These hubs often provide high connectivity to the entire network and can be critical for its stability and function [12].

- Transitivity (Clustering): Transitivity relates to the presence of tightly interconnected node groups called clusters, modules, or communities. These are groups of nodes that are more densely connected to each other than to the rest of the network. In biological contexts, these often correspond to functional units, such as protein complexes or metabolic pathways [12].

- Centralities: Centrality measures estimate the importance of a node or edge for network connectivity or information flow. Degree centrality is directly influenced by a node's degree. Betweenness centrality measures how often a node lies on the shortest paths between other nodes, identifying bottlenecks in the network. A node's degree strongly influences its centrality, with high-degree nodes often being more central [12].

Table 1: Key Topological Properties in Biological Networks

| Property | Biological Interpretation | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Degree | Connectivity or interactivity of a biological entity (e.g., a protein). | Identifying highly connected proteins (hubs) that may be essential for survival [11]. |

| Shortest Path | Potential efficiency of communication or signal propagation between entities. | Modeling information flow in signaling cascades or neuronal networks [12]. |

| Scale-Free Topology | Resilience against random attacks but vulnerability to targeted hub disruption. | Understanding network robustness and identifying potential drug targets [12] [11]. |

| Transitivity/Clustering | Functional modularity; groups of entities working together in a coordinated manner. | Discovering protein complexes, functional modules, or metabolic pathways [12]. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Control over information flow; potential for being a regulatory bottleneck. | Identifying critical nodes whose failure would disrupt network communication [12]. |

Major Types of Biological Networks

Biological systems give rise to diverse network types, each with distinct node and edge definitions and biological interpretations.

Table 2: Types of Biological Networks and Their Components

| Network Type | Nodes Represent | Edges Represent | Network Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PIN) | Proteins [11] | Physical interactions between proteins [11] | Undirected; high-degree "hub" proteins often essential for function [11]. |

| Gene Regulatory (GRN) | Genes, Transcription Factors [11] | Regulatory relationships (activation/inhibition) [11] | Directed; represents causal flow of genetic information. |

| Gene Co-expression | Genes [11] | Statistical association (e.g., correlation) between gene expression profiles [13] [11] | Undirected; identifies functionally related genes or co-regulated modules. |

| Metabolic | Small molecules (metabolites) [11] | Biochemical reactions converting substrates to products [11] | Directed or undirected; edges catalyzed by enzymes (not nodes). |

| Signaling | Proteins, Lipids, Ions [11] | Signaling interactions (e.g., phosphorylation) [11] | Directed; integrates PPIs, GRNs, and metabolic networks. |

| Neuronal | Neurons, Brain Regions [11] | Structural (axonal) or functional connections [11] | Can be directed or undirected; often exhibits small-world properties. |

| Food Webs | Species [11] | Predator-prey relationships [11] | Directed; studies ecological stability and species loss impact. |

Network Topology in Biomarker Research: An Analytical Framework

Network topology provides a powerful analytical framework for biomarker discovery and evaluation. The position and connectivity of a molecule within a biological network can significantly influence its potential as a clinically useful biomarker.

A Framework for Comparing Biomarker Performance

A standardized statistical framework has been developed to objectively compare potential biomarkers based on predefined criteria, including their precision in capturing change over time and their clinical validity (association with clinical outcomes) [14]. This framework allows for inference-based comparisons across different biomarkers and modalities. For instance, in studies of Alzheimer's disease, structural MRI measures like ventricular volume and hippocampal volume showed the best precision in detecting change over time in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and dementia [14]. Such quantitative comparisons are essential for identifying the most promising biomarkers for drug development and clinical trials.

Network-Informed Biomarker Discovery: The MarkerPredict Approach

Cutting-edge research leverages network topology and machine learning for predictive biomarker discovery. The MarkerPredict framework is a prime example, designed to identify predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapies [15]. It integrates several advanced concepts:

- Network Motifs: These are small, overrepresented subnetworks (like three-node triangles) that serve as regulatory hot spots in signaling networks. Proteins connected within these motifs often have stronger regulatory relationships [15].

- Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs): IDPs are proteins lacking a fixed tertiary structure. They are enriched in network motifs and are key players in information flow, interacting with central network nodes [15].

- Machine Learning: MarkerPredict uses Random Forest and XGBoost models trained on topological features and protein disorder data to classify potential biomarker-target pairs, generating a Biomarker Probability Score (BPS) for ranking candidates [15].

The experimental workflow below illustrates the MarkerPredict methodology, from data integration and network analysis to machine learning classification and biomarker validation.

MarkerPredict Workflow for Network-Based Biomarker Discovery

Experimental Protocol for Network-Based Biomarker Identification

The methodology for studies like MarkerPredict involves several key stages [15]:

- Network Construction and Curation: Compile signaling networks from expert-curated databases (e.g., CSN, SIGNOR, ReactomeFI). Define nodes (proteins) and edges (interactions).

- Topological Feature Extraction: Identify and catalog network motifs (e.g., three-node triangles) using tools like FANMOD. Calculate standard topological metrics (degree, betweenness centrality) for all nodes.

- Protein Annotation Integration: Annotate proteins with intrinsic disorder propensity using databases (DisProt) and prediction tools (IUPred, AlphaFold).

- Training Set Establishment: Create positive training sets from literature-curated, known predictive biomarker-target pairs. Establish negative controls from proteins not annotated as biomarkers or through random pairing.

- Machine Learning Model Training and Validation: Train classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) on the integrated feature set. Optimize hyperparameters and validate model performance using Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) and k-fold cross-validation.

- Candidate Ranking and Prioritization: Generate a Biomarker Probability Score (BPS) to rank all potential biomarker-target pairs. Prioritize high-scoring candidates for experimental validation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Biological Network Analysis

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Databases/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Interaction Databases | Catalog experimentally determined protein-protein interactions for network building. | BioGRID [11], MINT [11], IntAct [11], STRING [11] |

| Signaling Network Resources | Provide curated pathways and signaling relationships for directed network construction. | Reactome [11] [15], SIGNOR [15], Human Cancer Signaling Network (CSN) [15] |

| Gene Regulatory Resources | Offer data on gene regulation and transcription factor targets for GRN inference. | KEGG [11] |

| Biomarker Knowledge Bases | Annotate known clinical biomarkers from literature for training and validation. | CIViCmine [15] |

| Intrinsic Disorder Databases | Provide data on protein disorder, a feature used in advanced network analyses. | DisProt [15], IUPred [15], AlphaFold DB [15] |

| Network Motif Detection Tools | Identify statistically overrepresented small subnetworks (motifs) in larger networks. | FANMOD [15] |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Provide algorithms for building classification models that predict new biomarkers from network features. | Scikit-learn (Random Forest), XGBoost [15] |

The concepts of nodes, edges, and network topology provide an indispensable framework for modeling and understanding the staggering complexity of biological systems. By defining biological entities as nodes and their interactions as edges, researchers can abstract diverse processes—from gene regulation to ecological dynamics—into a universal graph representation. The topological properties of these networks, such as degree distribution, centrality, and modularity, are not merely mathematical abstractions; they reveal fundamental organizational principles that govern biological function, robustness, and evolution. Furthermore, as demonstrated by emerging methodologies like the MarkerPredict framework, network topology is rapidly becoming a cornerstone for systematic biomarker discovery and evaluation in translational research. By integrating topological features with molecular characteristics and machine learning, this approach offers a powerful, hypothesis-generating platform to identify and prioritize predictive biomarkers, ultimately accelerating the development of targeted therapies and personalized medicine.

Intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH) represents a fundamental challenge in oncology, referring to the distinct tumor cell populations with different molecular and phenotypical profiles within the same tumor specimen [16]. This heterogeneity arises through complex genetic, epigenetic, and protein modifications that drive phenotypic selection in response to environmental pressures, providing tumors with significant adaptability [16]. Functionally, ITH enables mutual beneficial cooperation between cells that nurture features such as growth and metastasis, and allows clonal cell populations to thrive under specific conditions such as hypoxia or chemotherapy [16]. The dynamic intercellular interplays are guided by a Darwinian selection landscape between clonal tumor cell populations and the tumor microenvironment [16].

Traditional gene-centric approaches have proven insufficient for capturing the full complexity of ITH, as they often focus on individual mutations or pathways without accounting for the interconnected nature of cellular systems [17]. In response to these limitations, network-based frameworks have emerged as powerful tools for contextualizing molecular complexity and identifying robust biomarkers that can predict treatment response despite heterogeneous tumor compositions [15] [6]. These approaches utilize protein-protein interaction networks, integrate multi-omics data, and apply machine learning to model how therapeutic effects propagate through cellular systems, ultimately reversing disease states by addressing their inherent complexity [6].

The Complex Landscape of Intratumoral Heterogeneity

Layers and Clinical Impact of Heterogeneity

ITH manifests across multiple biological layers, each contributing to therapeutic resistance and disease progression. The table below summarizes the key dimensions of heterogeneity and their clinical implications.

Table 1: Dimensions and Clinical Implications of Intratumoral Heterogeneity

| Dimension | Description | Clinical Impact | Example Cancer Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Heterogeneity | Diversity in DNA sequences, mutations, and chromosomal alterations among tumor cells [18] | Enables resistance to targeted therapies; drives tumor evolution [18] | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer (CRC), renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [18] |

| Morphological Heterogeneity | Variation in cellular appearance and organization within tumors [16] | Complicates pathological diagnosis and grading; associated with differential target expression [16] | Lung adenocarcinoma (acinar, solid, lipid, papillary patterns) [16] |

| Transcriptional & Epigenetic Heterogeneity | Differences in gene expression patterns and epigenetic modifications without DNA sequence changes [17] | Influences cell state plasticity and therapeutic vulnerability; enables phenotype switching [17] | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [17] |

| Metabolic Heterogeneity | Variable metabolic dependencies and pathways utilized by different tumor subpopulations [17] | Affects response to metabolic inhibitors; CSCs often show enhanced glutamine metabolism [17] | PDAC (CSCs with ASCT2 glutamine transporter) [17] |

| Spatial Heterogeneity | Distinct molecular profiles between different geographical regions of the same tumor [18] | Single biopsy may not represent entire tumor; sampling bias affects treatment decisions [18] | NSCLC (variable PD-L1 expression across regions) [18] |

| Temporal Heterogeneity | Evolutionary changes in tumor molecular profile over time, especially under treatment pressure [18] | Leads to acquired resistance; necessitates adaptive treatment strategies [18] | Various cancers under targeted therapy [18] |

Mechanisms Driving Heterogeneity

The development and maintenance of ITH stems from several interconnected biological processes. Genomic instability serves as a foundational mechanism, enabling cells to accumulate genetic alterations at accelerated rates [18]. This increased mutation tolerance allows tumor cells to evade cell death following DNA damage and withstand chromosomal changes, with chemotherapy often further exacerbating genomic instability [18]. Epigenetic modifications represent another major contributor, regulating gene expression without altering DNA sequences and enabling transcriptional plasticity that permits rapid adaptation to therapeutic pressures [17] [18]. The tumor microenvironment creates selective pressures through factors such as hypoxia, nutrient availability, and stromal interactions, driving clonal selection and expansion of resistant subpopulations [16] [18]. Additionally, cancer stem cells (CSCs) with self-renewal capacity generate cellular diversity through functional hierarchies, acting as reservoirs for tumor initiation, progression, and relapse [17].

Network-Based Frameworks for Addressing Heterogeneity

Theoretical Foundations of Network Medicine

Network-based approaches operate on the principle that cellular components function through interconnected relationships rather than in isolation. The therapeutic effect of drugs propagates through protein-protein interaction networks to reverse disease states, making network topology crucial for understanding treatment response [6]. Specifically, network motifs—recurring, significant subgraphs—represent functional units of signaling regulation, with certain motifs such as three-nodal triangles serving as hotspots for co-regulation between potential biomarkers and drug targets [15]. The position of proteins within networks also determines their functional importance, with centrally located nodes often playing critical roles in information flow and cellular decision-making [15]. Furthermore, intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) without stable tertiary structures frequently participate in interconnected network motifs and demonstrate strong enrichment as predictive biomarkers due to their signaling flexibility [15].

Key Network Methodologies and Platforms

Several computational frameworks have been specifically developed to address ITH through network-based approaches:

MarkerPredict utilizes network motifs and protein disorder properties to predict clinically relevant biomarkers [15]. The framework integrates three signaling networks with protein disorder data from DisProt, AlphaFold, and IUPred databases, applying Random Forest and XGBoost machine learning models to classify target-neighbor pairs [15]. Its biomarker probability score (BPS) normalizes the summative rank across models, enabling prioritization of biomarker candidates [15].

PRoBeNet prioritizes biomarkers by considering therapy-targeted proteins, disease-specific molecular signatures, and the human interactome [6]. This framework hypothesizes that drug effects propagate through interaction networks to reverse disease states, allowing it to identify biomarkers that predict patient responses to both established and investigational therapies [6].

Standardized Statistical Frameworks provide methods for comparing biomarker performance using criteria such as precision in capturing change and clinical validity [14]. These approaches enable inference-based comparisons across multiple biomarkers simultaneously, incorporating longitudinal modeling to account for disease progression and treatment effects [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Network-Based Biomarker Discovery Platforms

| Platform | Core Methodology | Network Elements | Validation Performance | Applications in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MarkerPredict [15] | Random Forest & XGBoost on target-neighbor pairs; Biomarker Probability Score | Triangle motifs with target proteins; intrinsically disordered proteins | LOOCV accuracy: 0.7-0.96; 426 biomarkers classified by all calculations | Identified LCK and ERK1 as potential predictive biomarkers for targeted therapeutics |

| PRoBeNet [6] | Network propagation of drug effects; integration of multi-omics signatures | Protein-protein interaction network; disease-specific molecular signatures | Significant outperformance vs. gene-based models with limited data; validated in ulcerative colitis and rheumatoid arthritis | Potential for stratifying patient subgroups in clinical trials for complex diseases |

| Standardized Statistical Framework [14] | Precision in capturing change; clinical validity measures | Not explicitly network-based but complementary to network approaches | Ventricular volume showed highest precision in detecting change in MCI and dementia | Provides validation methodology for network-derived biomarkers in neurodegenerative disease |

Network Approach to Heterogeneity: This diagram illustrates how network-based frameworks address various dimensions of intratumoral heterogeneity to identify clinically relevant biomarkers.

Experimental Protocols for Network-Based Biomarker Discovery

MarkerPredict Implementation Protocol

The MarkerPredict methodology follows a structured workflow for biomarker discovery and validation [15]:

Step 1: Network and Data Curation

- Obtain three signed subnetworks with distinct topological characteristics: Human Cancer Signaling Network (CSN), SIGNOR, and ReactomeFI [15]

- Collect intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) data from DisProt database and prediction methods (AlphaFold, IUPred) [15]

- Identify oncotherapeutic targets from clinical trial databases and literature [15]

Step 2: Motif Identification and Analysis

- Detect three-nodal motifs using FANMOD software [15]

- Select fully connected three-nodal motifs (triangles) for analysis [15]

- Statistically evaluate enrichment of IDPs in triangles containing drug targets [15]

Step 3: Machine Learning Model Development

- Establish positive training set from CIViCmine database of clinically validated predictive biomarkers [15]

- Create negative control dataset from proteins not present in CIViCmine and random pairs [15]

- Train Random Forest and XGBoost classifiers using topological features and protein disorder annotations [15]

- Optimize hyperparameters with competitive random halving search [15]

Step 4: Validation and Biomarker Prioritization

- Perform leave-one-out-cross-validation (LOOCV) and k-fold cross-validation [15]

- Calculate Biomarker Probability Score (BPS) as normalized average of ranked probability values [15]

- Manually review high-ranking biomarker candidates for biological plausibility [15]

PRoBeNet Experimental Workflow

The PRoBeNet framework implements a distinct approach focused on network propagation [6]:

Step 1: Network Construction

- Compile comprehensive human interactome from protein-protein interaction databases [6]

- Annotate network nodes with disease-specific molecular signatures from multi-omics data [6]

- Identify therapy-targeted proteins based on drug mechanism of action [6]

Step 2: Response Biomarker Identification

- Model propagation of therapeutic effect through the network from targeted proteins [6]

- Prioritize biomarkers based on proximity to drug targets in the network [6]

- Incorporate directionality of signaling relationships where available [6]

Step 3: Machine Learning Model Building

- Use PRoBeNet-identified biomarkers as features for classifier development [6]

- Compare performance against models using all genes or randomly selected genes [6]

- Evaluate performance particularly under limited data conditions [6]

Step 4: Clinical Validation

- Test predictive power using retrospective gene-expression data from patient cohorts [6]

- Validate with prospective data from clinical samples [6]

- Assess ability to stratify patient subgroups for clinical trial enrichment [6]

Biomarker Discovery Workflow: This diagram outlines the key experimental phases in network-based biomarker discovery, from data collection through clinical validation.

Performance Comparison: Network vs. Traditional Approaches

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Network-based approaches demonstrate distinct advantages over traditional biomarker discovery methods, particularly in their ability to address complex heterogeneity.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Biomarker Discovery Approaches

| Performance Metric | Traditional Gene-Centric Approaches | Network-Based Frameworks | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Accuracy | Limited by single-gene focus; fails with heterogeneous tumors [16] | LOOCV accuracy: 0.7-0.96 for MarkerPredict; robust classification across cancer types [15] | 30-50% improvement in accuracy with limited data [6] |

| Handling Limited Data | Poor performance with small sample sizes; overfitting common [6] | PRoBeNet significantly outperforms with limited data by incorporating network topology [6] | 2-3x better performance with n<50 samples [6] |

| Biomarker Robustness | Vulnerable to sampling bias in heterogeneous tumors [18] | Network propagation accounts for cellular heterogeneity; more consistent performance [6] | Identifies biomarkers stable across tumor subregions [6] |

| Clinical Applicability | Often fails validation in diverse patient populations [16] | Validated in multiple inflammatory and autoimmune conditions; ready for oncology trials [6] | Successful retrospective and prospective validation [6] |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Challenging to integrate genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic data | Naturally incorporates multi-omics through network connections [15] [6] | Unified framework for heterogeneous data types [15] |

Case Study: Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) exemplifies the challenges posed by ITH and the potential of network-based solutions. PDAC exhibits exceptional heterogeneity through multiple mechanisms: cancer stem cells with varying markers (CD133, CXCR4, CD44/CD24/EpCAM, c-MET) maintain tumor-initiating capacity [17]; transcriptional and epigenetic plasticity enables rapid adaptation to therapeutic pressure [17]; metabolic heterogeneity includes subpopulations with enhanced glutamine metabolism through CD9-ASCT2 interactions [17]; and dynamic phenotype switching along the epithelial-to-mesenchymal spectrum promotes metastasis and resistance [17].

Network analysis of PDAC has revealed that intrinsically disordered proteins frequently participate in interconnected network motifs with key therapeutic targets, suggesting their utility as predictive biomarkers [15]. For instance, Msi2-expressing CSCs show distinct epigenetic landscapes and upregulation of lipid/redox metabolic pathways, with RORγ identified as a key transcriptional regulator controlling stemness and oncogenic programs [17]. These network-derived insights provide opportunities for targeting the heterogeneity itself rather than specific mutations.

Computational Tools and Databases

Successful implementation of network-based approaches requires specific computational resources and datasets.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Network-Based Biomarker Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Function | Application in Heterogeneity Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signaling Networks | Human Cancer Signaling Network (CSN) [15], SIGNOR [15], ReactomeFI [15] | Provide curated cellular signaling pathways | Foundation for motif analysis and network propagation models |

| Protein Disorder Databases | DisProt [15], AlphaFold [15], IUPred [15] | Identify intrinsically disordered proteins | IDPs serve as key network hubs in heterogeneous signaling |

| Biomarker Knowledge Bases | CIViCmine [15] | Text-mined database of clinical biomarkers | Training and validation data for machine learning models |

| Motif Analysis Tools | FANMOD [15] | Detect network motifs and triangles | Identify regulatory hotspots containing targets and biomarkers |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Random Forest [15], XGBoost [15] | Binary classification of biomarker potential | Integrate network features to predict clinical utility |

| Validation Datasets | Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) [14] | Longitudinal clinical and biomarker data | Methodology validation for heterogeneity assessment |

Experimental Design Considerations

When implementing network-based approaches for heterogeneous diseases, several methodological considerations optimize success:

Sample Size and Power: Network approaches maintain performance with limited data, but adequate sampling across tumor regions remains essential for capturing spatial heterogeneity [6]. Multi-region sequencing helps address geographical diversity, while longitudinal sampling captures temporal evolution under treatment pressure [18].

Validation Strategies: Employ cross-validation within discovery cohorts (LOOCV, k-fold) followed by external validation in independent patient populations [15]. Prospective validation in clinical trial samples provides the strongest evidence for clinical utility [6].

Clinical Implementation: Consider practical constraints of clinical testing, including sample requirements, turnaround time, and cost-effectiveness [19]. Network-derived biomarkers should demonstrate clear clinical validity and actionability to justify implementation [19].

Network-based frameworks represent a paradigm shift in addressing the challenges of intratumoral heterogeneity in cancer. By contextualizing molecular measurements within biological systems rather than viewing them in isolation, these approaches identify robust biomarkers and therapeutic targets that remain effective despite cellular diversity. The integration of network topology, protein interaction data, and machine learning enables researchers to model the complex dynamics of tumor evolution and treatment resistance.

Future developments will likely focus on dynamic network modeling to capture temporal heterogeneity, single-cell network analysis to resolve cellular diversity at higher resolution, and integration of microenvironmental interactions to better model ecosystem-level dynamics. As these methodologies mature and validate in clinical trials, they hold significant promise for transforming oncology practice by enabling more effective targeting of heterogeneous tumors and overcoming the therapeutic resistance that currently limits cancer care.

In biomedical research, network-based biomarkers represent a paradigm shift from single-molecule biomarkers to systems-level understanding of disease mechanisms. By analyzing interactions between biomolecules, researchers can capture the complex functional relationships that underlie health and disease states. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI), co-expression, and signaling networks have emerged as three fundamental network types, each with distinct characteristics, construction methodologies, and applications in biomarker discovery. The evaluation of their performance is crucial for advancing personalized medicine and drug development, as these networks can identify robust signatures that accurately classify disease states, predict treatment response, and reveal novel therapeutic targets [20] [21].

Each network type provides unique insights: PPI networks map physical interactions between proteins, co-expression networks reveal coordinated gene expression patterns, and signaling networks model the flow of cellular information. Understanding their comparative strengths, limitations, and appropriate contexts of use enables researchers to select optimal strategies for specific biomarker discovery challenges. This guide provides an objective comparison of these network types, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies from recent studies.

Network Type Comparisons

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, data requirements, and primary applications of the three key network types in biomarker research.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Key Network Types

| Feature | Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks | Co-expression Networks | Signaling Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Representation | Proteins | Genes/Transcripts | Proteins, complexes, modified species |

| Edge Representation | Physical or functional interactions between proteins | Statistical correlation of expression levels (e.g., PCC, MI) | Directional signaling relationships (e.g., phosphorylation) |

| Primary Data Source | Yeast-two-hybrid, AP-MS, curated databases | Transcriptomics (microarray, RNA-seq) | Literature, curated pathways, phosphoproteomics |

| Network Dynamics | Typically static; represents potential interactions | Context-specific; can be built for different states | Dynamic; can model signal flow and perturbation |

| Key Biomarker Output | Interaction affinity, network hubs, modules | Co-expression modules, hub genes, differential connections | Pathway activity, critical signaling nodes, drug targets |

| Main Advantage | Direct mapping of functional protein complexes | Captures coordinated transcriptional programs | Models causal relationships and drug effects |

Performance in Biomarker Discovery

Different network types exhibit varying performance characteristics depending on the biological question and analytical goal. The table below compares their performance based on key metrics and applications as demonstrated in recent studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Network Types in Biomarker Studies

| Performance Metric | PPI Networks | Co-expression Networks | Signaling Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Accuracy | PPIA + EllipsoidFN achieved high accuracy in classifying breast cancer samples [20] | A 17-gene co-expression module showed high diagnostic performance for ovarian cancer (AUC analysis) [22] | Simulated Cell model predicted drug response (AUC=0.7 for DDR drugs) [23] |

| Stratification Capability | Identifies patient subgroups based on interaction dysregulation | Patient-specific SSNs revealed 6 novel LUAD subtypes with distinct motifs [24] | Identifies context-specific synergy mechanisms and resistance pathways |

| Novelty of Findings | Identifies differential interactions where single proteins show no significant change [20] | Reveals network rewiring not explainable by differential expression alone [24] | Predicts non-trivial regulators and combination-specific biomarkers [23] |

| Mechanistic Insight | Direct functional insight via protein complexes and pathways | Identifies coordinately regulated functional programs | Granular, pathway-level mechanism of action for drugs |

| Validation Approach | Linear programming model for biomarker selection [20] | ROC curves, modular analysis, in vivo validation [22] [25] | Benchmarking against in vitro drug screens (e.g., DREAM Challenge) [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

PPI Network Biomarker Identification

The PPIA (Protein-Protein Interaction Affinity) + EllipsoidFN method provides a robust framework for identifying network biomarkers from PPI networks [20]:

- PPIA Estimation: Apply the law of mass action to gene expression data to approximate the activity of protein complexes. For proteins P1 and P2 with mRNA expression levels

x1andx2, the interaction affinity is estimated asP1P2 = x1 * x2. - Feature Matrix Construction: Create a matrix combining both PPIA values for protein interactions and expression values for individual proteins.

- Optimization Model: Formulate a linear programming model to select a minimal set of protein interactions and individual proteins that maximally discriminate between sample classes (e.g., cancer vs. normal). The objective function minimizes the number of selected features while maximizing separation between classes.

- Validation: Evaluate the selected network biomarkers using cross-validation and independent datasets, assessing classification accuracy and biological relevance through pathway enrichment.

Differential Co-expression Analysis

Differential co-expression network analysis identifies biomarkers by comparing gene-gene correlations across different biological states [22]:

- Data Integration: Meta-analysis of multiple transcriptomics datasets (e.g., from GEO) to identify common differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

- Network Construction: Build separate co-expression networks for diseased and healthy states using Pearson correlation coefficients (PCC). Significantly co-expressed gene pairs are identified using absolute PCC > 0.8 and p < 0.05.

- Modular Analysis: Detect highly connected modules within networks using algorithms like MCODE. Identify topologically important hub genes based on network centrality measures.

- Biomarker Validation: Evaluate diagnostic performance of module genes using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. Further validate through in vivo models and immune infiltration analysis.

Signaling Network Modeling for Drug Response

The Simulated Cell approach uses signaling networks to predict drug response and identify biomarkers [23]:

- Network Customization: Create cell-type-specific signaling networks by integrating multi-omics data (e.g., genomic, proteomic) with a curated protein-protein interaction network.

- Model Calibration: Manually calibrate in silico models to match in vitro monotherapy drug response data (IC50 values), prioritizing correct signaling cascade representation.

- Combination Screening: Simulate drug combinations in a dose-matrix format (e.g., 16x16 dose ranges) across multiple cancer cell lines.

- Synergy Calculation: Compute Bliss synergy scores to identify synergistic drug pairs.

- Biomarker Identification: Systematically perturb nodes in the network to identify critical regulators of combination-specific response through analysis of signal propagation from drug targets to effector nodes.

Figure 1: Generalized Workflow for Network-Based Biomarker Discovery. This diagram outlines the common stages in identifying biomarkers from biological networks, from data input to validation.

Integrated Approaches and Advanced Frameworks

Hybrid Network Methods

Recent advances demonstrate the power of integrating multiple network types to overcome limitations of individual approaches:

PathNetDRP: This framework combines PPI networks with pathway information to predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. It applies the PageRank algorithm to prioritize genes associated with ICI response, maps them to biological pathways, and calculates PathNetGene scores to quantify their contribution to immune response, demonstrating superior performance over methods relying solely on differential expression [26].

WGCNA with Machine Learning: Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies gene modules associated with disease phenotypes, which are then refined using machine learning algorithms like LASSO and SVM-RFE to identify core biomarkers, as demonstrated in ulcerative colitis research [25].

Single-Sample Network Methods

Traditional co-expression networks require multiple samples, averaging heterogeneity. Single-sample networks (SSNs) address this limitation:

- LIONESS Method: The Linear Interpolation to Obtain Network Estimates for Single Samples approach estimates sample-specific networks by contrasting aggregate networks built with and without each sample. This enables patient-specific network analysis and has revealed novel LUAD subtypes based on network topology differences not detectable through gene expression alone [24].

Figure 2: Patient Stratification Using Single-Sample Networks. The LIONESS method enables the construction of individual patient networks, revealing subtypes based on network similarity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Network-Based Biomarker Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIBERSORT | Computational Algorithm | Estimates immune cell infiltration from RNA-seq data | Immune infiltration analysis in ulcerative colitis [25] |

| WGCNA R Package | Computational Tool | Constructs weighted gene co-expression networks | Identifying UC-related gene modules from transcriptome data [25] |

| LIONESS | Computational Method | Estimates single-sample gene co-expression networks | Patient-specific network analysis in LUAD [24] |

| Cytoscape with MCODE | Software with Plugin | Network visualization and module detection | Identifying highly connected modules in co-expression networks [22] |

| PageRank Algorithm | Network Analysis | Prioritizes important nodes in a network | Identifying ICI-response-associated genes in PathNetDRP [26] |

| PARP8 Antibody | Laboratory Reagent | Detects PARP8 protein expression in tissues | Validation of UC biomarker through immunofluorescence [25] |

| Dextran Sulfate Sodium | Chemical Inducer | Induces experimental colitis in mouse models | In vivo validation of UC biomarkers [25] |

The comparative analysis of PPI, co-expression, and signaling networks reveals that each network type offers distinct advantages for biomarker discovery. PPI networks provide direct functional insights into protein complexes, co-expression networks effectively capture transcriptional regulatory programs and patient heterogeneity, while signaling networks enable mechanistic modeling of drug effects and combination therapies. The choice of network type should be guided by the specific research question, available data, and desired biomarker application.

The most significant advances are emerging from integrated approaches that combine multiple network types and leverage single-sample methods to capture patient-specific network features. As network biology continues to evolve, these approaches will play an increasingly important role in developing clinically actionable biomarkers for precision medicine. Future directions will likely focus on dynamic network modeling, multi-omics integration, and the translation of network biomarkers into clinical diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making tools.

The Hallmarks of Cancer as a Blueprint for Network-Based Discovery

The "Hallmarks of Cancer" framework, pioneered by Hanahan and Weinberg, has long provided a conceptual foundation for understanding the functional capabilities that tumors acquire during malignant development. Traditionally encompassing traits such as sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, and enabling characteristics like genome instability, this framework has primarily been used as a taxonomic guide for categorizing oncogenic processes [27] [28]. However, contemporary systems biology reveals that cancer is not merely a collection of independent traits but a systemic pathology characterized by dynamic perturbations of regulatory networks across multiple hierarchical levels [27]. This shift in perspective transforms the hallmarks from a static list into a dynamic, interconnected network where the interactions between hallmark capabilities generate emergent properties critical for tumorigenesis.

Network-based approaches are fundamentally reshaping cancer research by moving beyond reductionist models that focus on individual genetic alterations. By constructing coarse-grained networks where each hallmark represents a functional module composed of numerous genes and proteins, researchers can now capture the system-level properties of cancer evolution [27]. This network perspective is particularly powerful because it reveals that critical transitions in tumor development are often preceded by significant reconfigurations in network topology, serving as early warning signals of malignancy before detectable shifts in hallmark activity levels occur [27]. The integration of this network-based framework with high-throughput genomic data and computational modeling is now yielding unprecedented insights into universal patterns of tumorigenesis while simultaneously identifying novel biomarker signatures and therapeutic targets across diverse cancer types.

Comparative Analysis of Network-Based Methodologies

The application of network-based approaches to the hallmarks of cancer has yielded several distinct methodological frameworks, each with unique strengths, data requirements, and applications for biomarker discovery. The table below provides a systematic comparison of three prominent methodologies developed for hallmark network analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Network-Based Methodologies in Hallmarks of Cancer Research

| Methodology | Core Approach | Data Input Requirements | Key Findings/Outputs | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallmark Network Dynamics [27] | Constructs coarse-grained gene regulatory networks of hallmarks using stochastic differential equations to model transitions from normal to cancerous states. | Genomic data from normal and cancerous tissues across multiple cancer types; Gene Ontology terms; GRAND database of gene regulatory networks. | Network topology reconfiguration precedes hallmark level shifts; "Tissue Invasion and Metastasis" shows greatest normal-cancer difference (JS divergence: 0.692); universal patterns across 15 cancers. | Captures dynamic, system-level properties; identifies early transition signals; pan-cancer validation. | Complex mathematical implementation; requires substantial computational resources. |

| NetRank Universal Biomarker Signature [28] | Network-based random surfer model integrating protein interaction networks (String database) with gene expression and phenotypic data. | Microarray datasets (105 datasets, ~13,000 patients, 13 cancer types); protein-protein interaction networks; phenotypic outcome data. | 50-gene universal biomarker signature performant across cancer types; signature genes strongly linked to hallmarks, particularly proliferation. | Robust, compact, interpretable signature; validated across diverse cancers and phenotypes. | Limited to existing protein interaction knowledge; microarray platform dependency. |

| Conserved Community Mining [29] | Identifies dense, conserved communities (subnetworks) in gene co-expression networks across multiple cancers using permutation tests. | mRNA expression data from TCGA (7 cancer types); clinical survival data; drug target databases. | Conserved communities related to immune response, cell cycle; prognostic for survival risk in multiple cancers; potential drug targets. | Discovers functional modules without prior knowledge; identifies weakly co-expressed but essential gene pairs. | Community detection sensitive to parameter selection; validation needed across more cancer types. |

Experimental Protocols for Hallmark Network Analysis

Protocol 1: Constructing and Analyzing Hallmark Network Dynamics

This protocol outlines the methodology for capturing macroscopic dynamic changes in tumorigenesis through hallmark networks, as described in the pan-cancer study of 15 cancer types [27].

Step 1: Hallmark Network Construction

- Map each of the 10 canonical hallmarks of cancer to corresponding gene sets using Gene Ontology terms

- Extract regulatory interactions between hallmark gene sets from the GRAND database of gene regulatory networks for both normal and malignant cells

- Construct a coarse-grained network where each hallmark represents a node, with edges encoding regulatory interdependencies between hallmark functional modules

Step 2: Dynamical System Modeling

- Implement a set of stochastic differential equations with Ornstein-Uhlenbeck noise to simulate hallmark dynamics

- Parameterize the model using time-dependent regulatory networks that evolve from initial stationary states (defined by normal tissue data) to final stationary states (defined by cancer data)

- Divide simulations into three phases: normal state (t=0-30), intermediate transition phase (t=30-70), and cancerous state (t=70-100), ensuring the system reaches a new stationary state

Step 3: Quantification of Hallmark Dynamics

- Simulate 10,000 trajectories of hallmark network evolution using the stochastic model

- Calculate probability distributions of hallmark levels for normal and cancerous states

- Perform statistical comparisons using Mann-Whitney U tests (significance threshold p<0.001)

- Quantify differences between normal and cancer states using Jensen-Shannon divergence, with values ranging from 0 (identical distributions) to 1 (maximal divergence)

Step 4: Pan-Cancer Validation

- Apply the identical framework across 15 different cancer types

- Identify universal patterns of network reconfiguration and hallmark activation

- Validate that network topology changes consistently precede significant shifts in hallmark activity levels across all cancer types

Protocol 2: NetRank-Based Universal Biomarker Discovery

This protocol details the implementation of the NetRank algorithm for identifying robust, pan-cancer biomarker signatures linked to cancer hallmarks [28].

Step 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Collect microarray datasets from public repositories (e.g., GEO), filtering for high-quality datasets with associated phenotype data

- Apply robust multi-array averaging for background correction and normalization

- Map probes to gene symbols using provided functional annotations

- Remove genes and samples with excessive missing values (>50% missing values excluded)

Step 2: Network Integration and Ranking

- Integrate protein-protein interaction networks from the String database (covering >20,000 proteins and >4 million interactions)

- Implement the NetRank algorithm, adapting Google's PageRank formula to rank genes by network connectivity and statistical relevance to phenotypes

- Apply the algorithm to each dataset individually, using 70% of samples for feature selection and 30% for evaluation

Step 3: Signature Aggregation and Validation

- Aggregate individual dataset signatures into a global signature through majority voting

- Evaluate signature performance using principal component analysis on the held-out evaluation sets

- Assess robustness through cross-validation across different cancer types and phenotypes

- Interpret biological relevance by mapping signature genes to hallmark of cancer processes, particularly proliferation-related pathways

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Hallmark Network Dynamics Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for analyzing hallmark network dynamics, from data integration through to the identification of critical transition signals in tumorigenesis.

Diagram Title: Hallmark Network Analysis Workflow

NetRank Biomarker Discovery Pipeline

The diagram below outlines the specific steps involved in the NetRank approach for universal biomarker signature identification, highlighting the integration of network information with expression data.

Diagram Title: NetRank Biomarker Discovery Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of network-based hallmark discovery requires specific computational tools, data resources, and analytical frameworks. The following table details essential components of the methodological toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Network-Based Hallmark Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Hallmark Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRAND Database [27] | Data Resource | Provides gene regulatory networks for normal and malignant cells | Source for regulatory interactions between hallmark gene sets; enables coarse-grained network construction |

| String Database [28] | Data Resource | Protein-protein interaction network covering >20,000 proteins | Foundation for network-based biomarker discovery; integrates physical and functional interactions |

| NetRank Algorithm [28] | Computational Algorithm | Network-based ranking integrating interaction and expression data | Identifies biologically relevant biomarker signatures linked to hallmarks |

| Cytoscape [30] [29] | Visualization & Analysis Software | Network visualization and analysis platform | Visualizes hallmark networks; community detection via MCODE plugin |

| Gephi [30] [31] | Visualization Software | Graph visualization and exploration software | Creates publication-quality network visualizations; exploratory analysis |

| igraph [30] [31] | Programming Library | Network analysis package for R/Python | Implements custom network analyses; community detection algorithms |

| MCODE [29] | Algorithm/Cytoscape Plugin | Detects dense clusters in biological networks | Identifies hallmark-related communities in co-expression networks |

| TCGA Data [29] | Data Resource | Multi-cancer genomic and clinical dataset | Primary source for mRNA expression data across cancer types; validation |

| Gene Ontology [27] | Data Resource | Functional annotation of genes | Maps hallmarks to specific gene sets; enables functional interpretation |

The integration of cancer hallmarks with network-based analytical frameworks represents a paradigm shift in oncology research, moving from a static, gene-centric view to a dynamic, system-level understanding of tumorigenesis. The methodologies compared in this guide—hallmark network dynamics, NetRank biomarker discovery, and conserved community mining—collectively demonstrate that universal patterns of cancer evolution emerge when analyzed through the lens of interconnected functional modules [27] [28] [29]. The consistent finding that network topology reconfiguration precedes detectable changes in hallmark activity levels offers particularly promising opportunities for early cancer detection and intervention [27].

The development of robust, interpretable biomarker signatures that perform consistently across multiple cancer types represents a significant advancement toward personalized oncology [28]. By anchoring these signatures in the biological context of cancer hallmarks, researchers can ensure both computational performance and biological relevance. Furthermore, the identification of conserved network communities across diverse cancers highlights fundamental evolutionary constraints in tumor development, pointing toward potentially universal therapeutic targets [29].

As network medicine continues to evolve, the hallmarks of cancer framework will likely serve as an increasingly precise blueprint for understanding cancer as a complex adaptive system. Future research directions should focus on refining dynamical models of hallmark interactions, validating network-based biomarkers in prospective clinical studies, and exploring how therapeutic interventions alter not just individual hallmark activities but the entire network topology of cancer systems. Through these efforts, network-based approaches promise to translate the conceptual framework of cancer hallmarks into clinically actionable tools for improving cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection.

Building and Applying Network Biomarkers: Frameworks and Real-World Impact

In the field of network-based biomarker research, the ability to decipher complex biological systems relies on computational frameworks that can model intricate relational data. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), particularly Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and Graph Attention Networks (GATs), have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing structured biological data, from molecular interactions to brain connectivity networks. These frameworks excel at capturing dependencies and interactions within graph-structured data, making them uniquely suited for identifying robust biomarkers from complex networks. Concurrently, random surfer models, rooted in algorithms like PageRank, provide complementary approaches for understanding node importance and influence propagation within networks. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these frameworks, focusing on their architectural principles, performance characteristics, and applications in biomarker discovery and biomedical research.

Architectural Principles and Mechanisms

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs)

GCNs operate on the principle of spectral graph convolution, applying neighborhood aggregation to learn node representations. In a typical GCN layer, each node's representation is updated by computing a weighted average of its own features and those of its immediate neighbors. This operation can be expressed as:

[ H^{(l+1)} = \sigma\left(\hat{D}^{-1/2}\hat{A}\hat{D}^{-1/2}H^{(l)}W^{(l)}\right) ]

where (\hat{A} = A + I) is the adjacency matrix with self-connections, (\hat{D}) is the corresponding degree matrix, (H^{(l)}) contains node embeddings at layer (l), and (W^{(l)}) is a trainable weight matrix [32]. The symmetric normalization term (\hat{D}^{-1/2}\hat{A}\hat{D}^{-1/2}) ensures stable training by preventing exploding or vanishing gradients. GCNs are particularly effective for capturing local neighborhood structures and have been widely applied to biological networks including protein-protein interaction networks and gene regulatory networks.

Graph Attention Networks (GATs)

GATs introduce an attention mechanism that assigns learned importance weights to neighboring nodes during feature aggregation. For a given node (i), the attention coefficient (e_{ij}) for its neighbor (j) is computed as:

[ e{ij} = \text{LeakyReLU}\left(\vec{a}^T[W\vec{h}i \| W\vec{h}_j]\right) ]

where (\vec{h}i) and (\vec{h}j) are node features, (W) is a shared weight matrix, (\vec{a}) is a trainable attention vector, and (\|) denotes concatenation [33]. These coefficients are normalized across all neighbors (j \in \mathcal{N}(i)) using the softmax function to obtain attention weights (\alpha_{ij}). The updated node representation is then computed as a weighted sum:

[ \vec{h}i' = \sigma\left(\sum{j \in \mathcal{N}(i)} \alpha{ij}W\vec{h}j\right) ]

GATs' ability to assign varying importance to different neighbors makes them particularly valuable for biological networks where certain interactions (e.g., specific gene regulations or protein interactions) may be more critical than others for determining phenotypic outcomes.

Random Surfer Models

Random surfer models, most famously exemplified by the PageRank algorithm, simulate the behavior of a random walker traversing a graph. At each step, the walker either follows a random edge from the current node with probability (d) (the damping factor) or jumps to a random node in the graph with probability (1-d). The PageRank score of a node represents the stationary probability that the walker is at that node after many steps, effectively capturing its importance based on the network structure. Variants like Personalized PageRank bias the random jumps toward specific nodes, allowing for context-sensitive importance scoring. In biomarker discovery, these models can identify key nodes (e.g., critical genes or brain regions) within biological networks by leveraging topological importance rather than node features alone.

Performance Comparison in Biomarker Research

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of GNN architectures across biological applications

| Application Domain | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Dataset | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) biomarker identification | Unsupervised GNN with permutation testing | Identified significant regions: cerebellum, temporal lobe, occipital lobe, Vermis3, Vermis4_5 | ABIDE I dataset | [34] |

| Major Depressive Disorder treatment prediction | Multimodal GNN (fMRI + EEG) | R² = 0.24 for sertraline, R² = 0.20 for placebo | EMBARC study (265 patients) | [35] |