Network Analysis in Drug Repurposing: From Predictive Models to Clinical Validation

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of network analysis in predicting and validating drug repurposing candidates.

Network Analysis in Drug Repurposing: From Predictive Models to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of network analysis in predicting and validating drug repurposing candidates. By integrating foundational principles of network medicine with cutting-edge computational methodologies, we examine how biological networks reveal novel therapeutic opportunities for existing drugs. The article systematically addresses key approaches including bipartite drug-disease networks, graph embedding techniques, and proximity measures within the human interactome. We further investigate troubleshooting strategies for algorithm optimization and data quality challenges, while providing a rigorous framework for computational and experimental validation. Through case studies across psychiatric disorders, oncology, and infectious diseases, this work provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical insights for implementing network-based repurposing strategies that accelerate therapeutic discovery while reducing development costs and timelines.

Network Medicine Foundations: Principles and Paradigms for Drug Repurposing

Network medicine represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, offering a framework to understand human disease not as a consequence of isolated molecular defects, but as perturbations within a complex, interconnected cellular interactome. This approach acknowledges that most cellular components exert their functions through intricate interactions with other components, creating a network where dysfunction can propagate and manifest as disease [1]. The foundational hypothesis of network medicine posits that disease phenotypes rarely result from abnormalities in a single effector gene product but instead reflect various pathobiological processes interacting within a complex network [2] [1].

This paradigm has emerged in response to the limitations of reductionist approaches, which, while valuable, often overgeneralize disease phenotypes and fail to account for individualized nuances in disease expression and susceptibility [2]. The advancement of high-throughput technologies has enabled the systematic mapping of molecular interactions, making it possible to construct comprehensive networks of human disease and apply computational methods to discern how complexity controls disease manifestations, prognosis, and therapy [2] [3].

Theoretical Foundations of Disease Networks

The Human Interactome: Structure and Properties

The human interactome comprises an extensive network of molecular interactions, including protein-protein interactions, metabolic reactions, regulatory relationships, and RNA networks [1]. With approximately 25,000 protein-encoding genes, about a thousand metabolites, and numerous distinct proteins and functional RNA molecules, the cellular components serving as nodes of the interactome easily exceed one hundred thousand, with the number of functionally relevant interactions being much larger and still largely unknown [1].

Biological networks exhibit distinct organizing principles that differentiate them from randomly linked networks. Two key properties are particularly relevant to understanding disease:

Scale-free topology: Unlike random networks where most nodes have approximately the same number of links, biological networks often follow a power-law degree distribution, resulting in the presence of a few highly connected hubs [1]. These hubs can be classified into "party hubs" that function within specific cellular processes and "date hubs" that link different processes and organize the interactome [1].

Small-world phenomenon: Most biological networks exhibit relatively short paths between any pair of nodes, meaning most proteins or metabolites are only a few interactions away from any other proteins or metabolites [1]. This property has important implications for how perturbations can spread through the network.

Disease Modules and Network Perturbations

In network medicine, diseases are interpreted as localized perturbations within the interactome. The "disease module" hypothesis suggests that cellular components associated with a specific disease are not scattered randomly across the interactome but tend to cluster in distinct neighborhoods [1]. The identification of these disease modules enables researchers to map the molecular relationships between apparently distinct pathophenotypes and uncover shared biological mechanisms [1].

The location of a disease gene within the network topology significantly influences its phenotypic impact. Genes associated with similar diseases often reside in the same network neighborhood, exhibit higher connectivity, and share common regulatory elements [1]. This understanding facilitates the identification of new disease genes and helps uncover the biological significance of disease-associated mutations identified through genome-wide association studies and full genome sequencing [1].

Network-Based Drug Repurposing: A Comparative Analysis

Drug repurposing, the practice of finding new therapeutic uses for existing medications, has emerged as a vital application of network medicine. This approach offers a cost-effective alternative to de novo drug development by leveraging existing pharmacological knowledge and safety profiles [4]. Network-based methods frame drug repurposing as a link prediction problem within bipartite networks connecting drugs to diseases [4].

Performance Comparison of Prediction Algorithms

Different computational approaches have been developed to predict novel drug-disease associations. The table below summarizes the performance of major algorithm classes based on cross-validation tests:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Network-Based Link Prediction Methods for Drug Repurposing

| Algorithm Class | Representative Methods | Key Principle | AUC-ROC | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Embedding | node2vec [4], DeepWalk [4] | Constructs low-dimensional network representations to infer proximity | >0.95 [4] | Captures complex topological patterns; High predictive accuracy | Black box nature; Limited interpretability |

| Network Model Fitting | Degree-corrected stochastic block model [4] | Fits statistical models to network structure to identify missing links | High precision (nearly 1000x better than chance) [4] | Statistical foundation; Identifies meaningful community structure | Computationally intensive for large networks |

| Similarity-Based Methods | Various similarity metrics [4] | Leverages node similarity measures (e.g., common neighbors) | Moderate performance [4] | Computational simplicity; Intuitive interpretation | Lower performance compared to advanced methods |

| Hybrid Approaches | Combined pharmacological and network data [4] | Integrates multiple data types (structure, targets, interactions) | Variable; context-dependent [4] | Leverages complementary information; Holistic perspective | Increased complexity in data integration |

The performance metrics demonstrate that graph embedding and network model fitting approaches achieve impressive prediction capabilities, with area under the ROC curve exceeding 0.95 and average precision almost a thousand times better than chance in cross-validation tests [4]. These methods operate on purely network-based data, suggesting that combined approaches incorporating additional pharmacological insight could potentially yield even better performance [4].

Experimental Validation Frameworks

Robust experimental validation is crucial for verifying computational predictions in network medicine. The standard methodology involves:

Cross-validation tests: Systematically removing a small fraction of known drug-disease edges from the network and testing the algorithm's ability to identify these missing connections [4]. This approach provides quantitative measures of prediction accuracy while controlling for overfitting.

Prospective validation: Implementing predicted drug-disease associations in experimental models, including:

- In vitro cell culture systems measuring disease-relevant phenotypic changes

- Ex vivo tissue models assessing functional recovery

- In vivo animal models evaluating disease modification

- Clinical trials confirming therapeutic efficacy in human populations

Network perturbation experiments: Systematically disrupting predicted network connections using genetic (e.g., CRISPR, RNAi) or pharmacological interventions to validate their functional significance [2] [1].

Methodological Approaches in Network Medicine

Network Construction and Data Integration

The construction of comprehensive biological networks requires the integration of diverse data types. The following workflow illustrates the primary steps in building and analyzing disease networks:

Network Construction and Analysis Workflow

The major data sources for network construction include:

- Molecular data: Protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions, metabolic pathways, gene regulatory networks, and RNA networks [2] [1]

- Clinical data: Disease phenotypes, patient comorbidities, treatment outcomes, and epidemiological information

- Literature data: Manually curated interactions from scientific literature using natural language processing and text mining [4]

Key Experimental Protocols

Link Prediction Methodology for Drug Repurposing

The following protocol details the steps for predicting drug-disease associations using network-based link prediction:

Network Assembly: Compile a bipartite network of drugs and diseases where edges represent known therapeutic indications. This process combines existing databases (e.g., DrugBank, clinical guidelines), natural-language processing tools, and hand curation to ensure data quality [4].

Data Cleaning: Remove duplicates, resolve nomenclature inconsistencies, and verify evidence levels for each drug-disease association. This step is crucial for reducing false positives and improving prediction accuracy [4].

Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate link prediction algorithms based on network size, sparsity, and computational resources. Graph embedding methods and stochastic block models have demonstrated superior performance for drug-disease networks [4].

Cross-Validation: Implement k-fold cross-validation by randomly removing a subset of known edges and measuring the algorithm's ability to recover them using metrics including AUC-ROC, precision-recall curves, and average precision [4].

Candidate Prioritization: Rank predicted drug-disease associations by their prediction scores and filter based on pharmacological plausibility, potential side effects, and clinical feasibility.

Experimental Validation: Design in vitro and in vivo experiments to test top predictions, beginning with disease-relevant cellular models and progressing to animal models of disease [2].

Disease Module Identification Protocol

Identifying disease modules within the interactome involves these key steps:

Seed Gene Selection: Compile a set of known disease-associated genes from genome-wide association studies, sequencing studies, and literature curation [1].

Network Propagation: Use random walk or diffusion-based methods to expand from seed genes to identify network neighborhoods that are statistically significantly enriched for disease associations [1].

Module Validation: Verify the biological coherence of identified modules through:

- Enrichment analysis for specific biological pathways and processes

- Cross-validation with independent disease gene sets

- Experimental perturbation of module components in disease models

Inter-Module Relationship Mapping: Analyze overlaps and connections between different disease modules to identify shared pathobiological mechanisms and potential comorbidity patterns [1].

The implementation of network medicine approaches requires specialized computational tools and data resources. The table below summarizes key solutions for network-based drug repurposing research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Network Medicine

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Drug Repurposing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Interaction Databases | BioGRID [1], HPRD [1], MINT [1] | Catalog experimentally verified protein-protein interactions | Mapping drug targets within interactome; Identifying downstream effects |

| Metabolic Networks | KEGG [1], BIGG [1] | Curate metabolic pathways and biochemical reactions | Understanding metabolic side effects; Identifying metabolic vulnerabilities |

| Regulatory Networks | TRANSFAC [2], JASPAR [2], UniPROBE [2] | Document transcription factor binding sites | Predicting gene expression changes; Understanding regulatory consequences |

| Drug-Target Databases | DrugBank [4] | Annotate drug-target interactions | Building drug-disease networks; Identifying shared target pathways |

| Post-Translational Modification Databases | PhosphoSite [2], PhosphoELM [2], PHOSIDA [2] | Catalog protein phosphorylation sites | Mapping signaling networks; Understanding regulatory mechanisms |

| Network Analysis Software | Cytoscape [2], NetworkX | Visualize and analyze biological networks | Implementing link prediction algorithms; Visualizing disease modules |

These resources provide the foundational data and analytical capabilities necessary for constructing comprehensive networks and implementing predictive algorithms for drug repurposing.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite considerable progress, network medicine faces several conceptual and technical challenges that must be addressed to advance the field:

Network Incompleteness: Current human interactome maps remain substantially incomplete, with many interactions yet to be discovered [1]. This incompleteness can lead to biased predictions and missed associations.

Data Quality and Noise: High-throughput interaction data often contain false positives and false negatives, requiring sophisticated statistical methods to distinguish true biological signals from noise [1].

Temporal and Spatial Dynamics: Most current network models are static, while biological systems are inherently dynamic, with interactions that change across time, cell types, and subcellular locations [5].

Multi-Scale Integration: Effectively integrating molecular-level networks with tissue-level, organ-level, and organism-level pathophysiology remains challenging [5].

Computational Complexity: Analyzing large-scale networks with millions of nodes and edges requires substantial computational resources and efficient algorithms [4].

Future directions in network medicine include incorporating single-cell data to account for cellular heterogeneity, developing dynamic network models that capture temporal changes, integrating multi-omic data across different biological layers, and applying advanced machine learning techniques to improve prediction accuracy [5]. As these challenges are addressed, network medicine promises to reshape our fundamental understanding of disease mechanisms and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Within the broader thesis of evaluating computational drug repurposing, network analysis has emerged as a cornerstone methodology. This guide provides an objective comparison of two pivotal network paradigms: bipartite drug-disease networks and integrated biological interactomes. We evaluate their construction, inherent properties, and experimental performance in predicting novel therapeutic associations, synthesizing data from recent and foundational studies to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Network Constructs: A Comparative Foundation

The architecture of the underlying network fundamentally shapes prediction strategies. The two primary types are distinguished by their node and edge semantics.

Bipartite Drug-Disease Networks are affiliation networks containing two disjoint node sets—drugs and diseases. An edge exists exclusively between a drug and a disease node, representing a known therapeutic indication [4] [6]. This structure directly encodes the repurposing problem, allowing it to be treated as a link prediction task: identifying missing edges in an incomplete network [4] [7]. Recent efforts have created large-scale, curated bipartite networks, such as one comprising 2620 drugs, 1669 diseases, and 8946 confirmed therapeutic associations, built from explicit indications without indirect inference [4] [6] [7].

Integrated Biological Interactomes are large-scale, unified networks of biomolecular interactions. A foundational example is the consolidated human interactome, integrating protein-protein interactions, signaling pathways, and metabolic interactions [8]. For repurposing, disease genes (e.g., 398 proteins for myocardial infarction) and drug targets (e.g., 361 targets for MI-related drugs) are mapped onto this interactome [8]. The analysis then probes the network proximity between drug targets and disease proteins or constructs higher-order drug-target-disease (DTD) modules within the interactome [8]. Another approach constructs heterogeneous networks that layer multiple node types (e.g., drugs, diseases, proteins, pathways) and relationships into a single graph for embedding learning [9] [10].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Network Architectures

| Network Type | Primary Node Types | Edge Semantics | Core Analytical Approach | Exemplary Scale (Nodes/Edges) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipartite Drug-Disease | Drugs, Diseases | Known therapeutic indication | Link prediction on bipartite graph | 2,620 drugs, 1,669 diseases, 8,946 edges [4] [7] |

| Integrated Interactome | Proteins/Genes | Physical/functional interaction (PPI, signaling, etc.) | Proximity analysis; DTD module detection | Human interactome: ~14k proteins, ~170k interactions [8] |

| Multiplex-Heterogeneous | Drugs, Diseases, Proteins, etc. | Multiple (therapeutic, similarity, interaction) | Random Walk with Restart (RWR) on multiplex layers | Integrates 3 disease similarity networks (phenotypic, molecular, ontological) [10] |

Performance Comparison: Prediction Accuracy and Robustness

The efficacy of these network types is ultimately measured by their predictive performance in cross-validation experiments. Performance metrics such as Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC/AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) are standard benchmarks.

Bipartite Network Link Prediction has demonstrated exceptionally high performance using modern algorithms. Applied to the large bipartite drug-disease network [4], methods like graph embedding (node2vec, DeepWalk) and statistical model fitting (degree-corrected stochastic block model) achieved AUROC > 0.95 and average precision nearly a thousand times better than random chance [4] [6] [7]. This shows that the network topology alone harbors strong predictive signals for drug indication.

Interactome-Based Proximity & Module Detection offers mechanistic insight. In the myocardial infarction (MI) study, MI drug targets were shown to be significantly proximate to MI disease proteins in the human interactome (P < 1.0×10⁻¹⁶) [8]. The derived DTD modules provide biological plausibility but are typically validated through functional enrichment rather than large-scale quantitative prediction benchmarks.

Heterogeneous Network Embedding represents a sophisticated synthesis. Models like HNF-DDA, which use transformer-style all-pairs message passing and subgraph contrastive learning on heterogeneous networks (integrating drugs, diseases, proteins), have reported superior performance on benchmark datasets (KEGG, HetioNet), outperforming state-of-the-art methods in AUROC, AUPR, and accuracy [9]. Similarly, MHDR, a method using a Random Walk with Restart (RWR) algorithm on a multiplex-heterogeneous network integrating phenotypic, ontological, and molecular disease similarities, outperformed predecessors like TP-NRWRH and DDAGDL in 10-fold cross-validation [10].

Table 2: Comparative Prediction Performance of Network-Based Methods

| Method (Network Type) | Key Algorithm | Reported Performance | Experimental Validation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipartite Link Prediction | Degree-corrected stochastic block model, Graph embedding | AUROC > 0.95; Avg. Precision ~1000x random | 10-fold cross-validation on network of 2,620 drugs, 1,669 diseases | [4] [7] |

| Interactome Proximity (MI Study) | Shortest path distance, Hypergeometric test | Significant proximity (P < 1.0×10⁻¹⁶); Identification of 12 DTD modules | Statistical significance vs. random gene sets; Functional enrichment of modules | [8] |

| HNF-DDA (Heterogeneous) | Transformer-style embedding, Subgraph contrastive learning | Outperformed baselines (RotatE, DREAMwalk, etc.) in AUROC/AUPR | 10-fold CV on KEGG & HetioNet; Case studies on breast/prostate cancer | [9] |

| MHDR (Multiplex-Heterogeneous) | Adapted Random Walk with Restart (RWR) | Outperformed TP-NRWRH, DDAGDL, RGLDR in 10-fold CV | Leave-one-out & 10-fold CV; Validation via shared genes/pathways | [10] |

| Bipartite Local Models (BLM) | Supervised kernel method | AUC > 0.97 for ion channels; AUPR up to 84% | Cross-validation on 4 drug-target network classes (enzymes, GPCRs, etc.) | [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The robust performance claims above are grounded in specific, reproducible experimental methodologies.

Protocol 1: Bipartite Network Construction & Link Prediction Cross-Validation [4] [7]

- Data Curation: Assemble drug-disease pairs from machine-readable (e.g., DrugBank) and textual databases using natural language processing and manual curation. Include only explicit, known therapeutic indications.

- Network Formation: Construct a bipartite graph G=(Vᵈ ∪ Vˢ, E), where Vᵈ are drug nodes, Vˢ are disease nodes, and edge e(dᵢ, sⱼ) ∈ E signifies drug dᵢ treats disease sⱼ.

- Link Prediction Algorithms:

- Similarity-based: Compute resource allocation or cosine similarity scores between node neighborhoods.

- Graph Embedding: Generate low-dimensional vector representations for nodes using algorithms like node2vec [4] or DeepWalk [7], then predict links based on vector proximity.

- Stochastic Block Model Fitting: Fit a degree-corrected stochastic block model to the observed network. The probability of a missing edge is derived from the inferred block memberships and degree parameters.

- Cross-Validation: Randomly remove a small fraction (e.g., 10%) of edges from E to form a training set E_train and a test set E_test. Train the prediction algorithm on E_train and rank all non-observed edges. Evaluate using AUROC/AUPR by checking the rank of held-out edges in E_test. Repeat over multiple folds.

Protocol 2: Interactome-Based DTD Module Detection [8]

- Data Integration:

- Compile a consolidated human interactome from multiple databases (PPI, complexes, signaling).

- Obtain disease-associated genes from curated resources (e.g., HuGE Navigator Phenopedia).

- Obtain drug targets for relevant drugs (e.g., MI drugs and their interactors) from DrugBank.

- Mapping and Proximity Analysis: Map disease proteins and drug targets onto the interactome. Compute the shortest path distance between drug target sets and disease protein sets. Assess statistical significance against a null model of randomly selected protein sets of equal size.

- Bipartite Network Construction & Community Detection:

- Construct a bipartite network between the MI-related drug targets and MI disease proteins, where an edge represents a physical interaction in the interactome.

- Apply a community detection algorithm (e.g., the Louvain method) to maximize bipartite modularity (Q) and identify densely connected DTD modules.

- Biological Validation: Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., GO, pathway) on proteins within each derived module to assess biological coherence.

Protocol 3: Multiplex-Heterogeneous Network Construction for RWR [10]

- Build Multiple Disease Similarity Networks:

- DiSimNetO (Phenotypic): Compute similarity from OMIM records using text mining (MimMiner), connect each disease to its 5 nearest neighbors.

- DiSimNetH (Ontological): Calculate semantic similarity based on Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) annotations.

- DiSimNetG (Molecular): Compute similarity based on shared disease genes and their interaction profiles in a gene network (e.g., HumanNet).

- Form a Disease Multiplex Network: Layer DiSimNetO, DiSimNetH, and DiSimNetG into a single multiplex network where each layer is a different similarity perspective.

- Construct Multiplex-Heterogeneous Network: Link a drug similarity network (e.g., based on chemical structure, DrSimNetC) to the disease multiplex network using a bipartite layer of known drug-disease associations.

- Adapted RWR Prediction: Perform a Random Walk with Restart that propagates probability across all layers of the multiplex-heterogeneous network. The steady-state probability distribution of the walker landing on disease nodes, when starting from a specific drug node, ranks candidate diseases for repurposing.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Workflow for Multiplex-Heterogeneous Network Prediction

Link Prediction Cross-Validation Protocol

Table 3: Key Resources for Network Construction and Analysis in Drug Repurposing

| Resource Name | Type/Function | Primary Use in Research | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank | Database | Provides comprehensive drug information, including targets, indications, and chemical structures. | Source for drug-target links and therapeutic indications [8] [11]. |

| KEGG BRITE / LIGAND | Database | Curates drug-target interaction data and chemical compound structures. | Used to obtain known interactions and compute chemical similarities via SIMCOMP [11]. |

| APID Interactomes | Meta-database | Provides a unified, quality-controlled compendium of protein-protein interactions. | Source for constructing the human interactome for proximity analysis [12] [13]. |

| OMIM / HuGE Navigator | Database | Catalogues human genes and genetic disorders with curated disease-gene associations. | Source for compiling disease-associated gene sets (e.g., MI disease genes) [8]. |

| Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | Ontology | Provides standardized terms for describing phenotypic abnormalities. | Used to compute semantic disease similarity for network layers [10]. |

| HumanNet | Functional Gene Network | A probabilistic functional gene network integrating diverse data types. | Serves as the basis for calculating molecular disease similarity [10]. |

| SIMCOMP | Computational Tool | Calculates global chemical structure similarity between compounds based on graph alignment. | Generates drug chemical similarity matrices for network construction [11]. |

| NetworkX (Python) | Software Library | A package for the creation, manipulation, and study of complex networks. | Used for implementing network algorithms (shortest path, subgraph induction) [8]. |

| Cytoscape | Software Platform | An open-source platform for complex network visualization and analysis. | Used for visualizing interaction networks and derived modules [8]. |

| Louvain Algorithm | Community Detection Algorithm | A heuristic method for maximizing modularity to detect communities in large networks. | Applied to bipartite drug-target-disease networks to identify functional modules [8] [14]. |

The discovery and development of new therapeutics is a time-consuming and costly process, with traditional models often struggling to address the complexity of multifactorial diseases. Polypharmacology, the design or use of pharmaceutical agents that act on multiple targets, has emerged as a paradigm to overcome these challenges [15]. Rather than adhering to the conventional "one target, one drug" model, polypharmacology embraces the inherent complexity of biological systems by systematically modulating multiple targets within disease-associated networks [15] [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for drug repurposing, which identifies new therapeutic uses for existing drugs, potentially reducing development timelines from the typical 12-15 years and costs ranging from $314 million to $2.8 billion [17].

Network theory provides the fundamental mathematical framework for implementing polypharmacology strategies in drug repurposing. By representing biological systems as interconnected networks of proteins, drugs, and diseases, researchers can apply sophisticated computational analyses to identify non-obvious therapeutic relationships [4] [6]. The core premise is that disease proteins are not randomly distributed within the human interactome but tend to cluster in specific neighborhoods known as disease modules [18]. Similarly, drugs with related therapeutic effects often target proteins that reside in topologically close regions of these networks. This systematic understanding enables the rational prediction of drug-disease associations through network-based link prediction methods, which treat the identification of repurposing candidates as a problem of finding missing connections in a complex bipartite network of drugs and diseases [4] [6].

Methodological Framework: Network-Based Prediction Approaches

Data Network Construction

The foundation of any network pharmacology approach is the construction of comprehensive, high-quality biological networks. The most effective drug-disease networks are compiled through a combination of existing machine-readable databases, textual sources processed with natural language processing tools, and meticulous hand curation to ensure accuracy [4] [6]. A robust network typically includes several key elements: protein-protein interactions (PPI) compiled from sources such as STRING; drug-target interactions from databases like DrugBank and ChEMBL; and disease-gene associations from resources including DisGeNET, GeneCards, and OMIM [19] [16]. The resulting bipartite network structure consists of two distinct node types (drugs and diseases) with connections only between unlike types, representing known therapeutic indications [4]. This network serves as the foundational substrate for all subsequent predictive analyses.

Table 1: Essential Components for Network Construction

| Component Type | Key Resources | Role in Network Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interactions | STRING, BioGRID | Forms the backbone of the human interactome; enables mapping of biological pathways and connectivity. |

| Drug-Target Interactions | DrugBank, ChEMBL, STITCH | Connects pharmaceutical compounds to their molecular targets; establishes drug action mechanisms. |

| Disease-Gene Associations | DisGeNET, GeneCards, OMIM | Links diseases to their associated proteins/genes; defines disease modules within the interactome. |

| Drug-Disease Indications | Clinicaltrials.gov, FDA labels | Provides ground truth data for known therapeutic relationships; enables model training and validation. |

| Natural Compounds | TCMSP, PubChem, ChemSpider | Incorporates phytochemicals and natural products with polypharmacological potential. |

Key Algorithmic Approaches

Link Prediction in Bipartite Drug-Disease Networks

Link prediction methods treat drug repurposing as a network completion problem, where missing connections (edges) between drug and disease nodes represent potential repurposing opportunities [4] [6]. These methods operate on the premise that the existing network structure contains implicit patterns that can be extrapolated to identify plausible missing connections. Cross-validation tests, where a subset of known edges is removed and the algorithm's ability to recover them is measured, have demonstrated impressive performance with area under the ROC curve exceeding 0.95 and average precision almost a thousand times better than chance [4]. The most effective algorithms include graph embedding techniques (node2vec, DeepWalk) that create low-dimensional representations of network topology, and statistical models like the degree-corrected stochastic block model that capture the underlying community structure of drug-disease relationships [4] [6].

Network Proximity and Separation Metrics

For drug combinations, the separation metric (sAB) quantifies the topological relationship between two drug-target modules within the human interactome [18]. This measure compares the mean shortest distance between targets of different drugs to the mean distance within each drug's targets, calculated as sAB ≡ 〈dAB〉 - (〈dAA〉 + 〈dBB〉)/2 [18]. A negative separation value indicates that the drugs target overlapping network neighborhoods, while a positive value suggests topologically distinct targets. This metric has proven particularly valuable for identifying efficacious drug combinations, with research showing that the most therapeutically beneficial combinations often involve drugs whose targets are separated (sAB ≥ 0) but both overlap with the disease module [18].

Literature-Based Similarity and Network Diffusion

Literature-based approaches leverage the vast repository of scientific publications to establish drug-drug relationships through text mining and citation networks [17]. The Jaccard coefficient, which measures the overlap between literature associated with different drugs, has emerged as the most effective similarity metric for identifying drug repurposing opportunities, outperforming other measures in validation studies using the repoDB dataset [17]. This method operates on the principle that drugs with significant literature overlap likely share biological mechanisms and therefore potential therapeutic applications. When combined with network diffusion techniques that propagate information through the network based on connectivity patterns, these approaches can identify novel drug-disease associations that are not immediately obvious from direct connections alone.

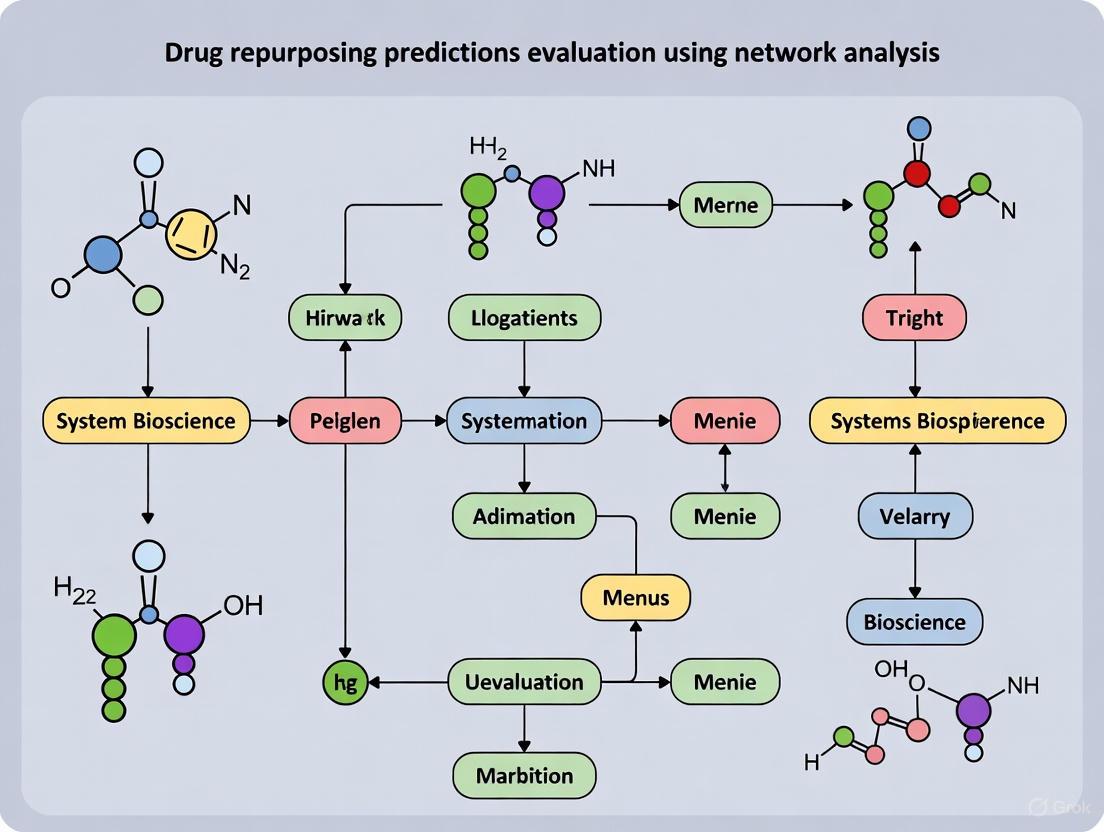

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for network-based drug repurposing, integrating multiple computational approaches.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Method Efficacy and Validation

Quantitative evaluation of network-based repurposing methods reveals distinct performance characteristics across different approaches. In comprehensive cross-validation studies, graph embedding and network model fitting methods have demonstrated exceptional performance in predicting missing drug-disease associations, correctly identifying more than 90% of known therapeutic connections in withheld validation sets [4] [6]. The separation metric (sAB) has proven particularly valuable for predicting effective drug combinations, significantly outperforming traditional chemoinformatics and bioinformatics approaches in identifying FDA-approved drug combinations [18]. Literature-based methods using the Jaccard coefficient have also shown strong performance, with studies reporting high AUC values and F1 scores when validated against standard repoDB datasets [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Network-Based Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Embedding/Link Prediction | Area Under ROC Curve | >0.95 [4] | Predicting single-drug repurposing for diseases with established drug modules |

| Network Proximity (sAB) | Accuracy vs. Random | Significantly outperforms random prediction and alternative measures [18] | Identifying synergistic drug combinations with complementary mechanisms |

| Literature-Based (Jaccard) | AUC, F1 Score | Superior to other similarity metrics based on AUC and F1 score [17] | Leveraging existing knowledge for novel indications, particularly for well-studied drugs |

| Subtype-Specific (NetSDR) | Module-specific Targeting | Effective identification of subtype-specific therapeutic modules [20] | Precision medicine applications in heterogeneous diseases like cancer |

Network Topology of Effective Combinations

Research on drug-drug-disease relationships has revealed six distinct topological configurations that characterize potential combination therapies [18]. These include: (1) Overlapping Exposure, where two overlapping drug-target modules also overlap with the disease module; (2) Complementary Exposure, where two separated drug-target modules both individually overlap with the disease module; (3) Indirect Exposure, where one drug in overlapping drug-target modules overlaps with the disease module; (4) Single Exposure, where only one drug in separated drug-target modules overlaps with the disease; (5) Non-exposure, where overlapping drug-target modules are separated from the disease; and (6) Independent Action, where all modules are topologically separated [18]. Notably, analysis of FDA-approved combinations for hypertension and cancer revealed that only the Complementary Exposure class (where separated drug-target modules both hit the disease module) consistently correlated with therapeutic efficacy, providing a crucial design principle for rational drug combination development [18].

Diagram 2: Complementary exposure configuration, where separated drug-target modules both hit the disease module - the topology most associated with effective combinations.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Subtype-Specific Repurposing for Complex Diseases

Cancer's profound heterogeneity necessitates therapeutic strategies tailored to specific molecular subtypes. The NetSDR (Network-based Subtype-specific Drug Repurposing) framework addresses this challenge by integrating proteomic signatures with network perturbations to identify subtype-specific repurposing opportunities [20]. This methodology involves constructing cancer subtype-specific protein-protein interaction networks by analyzing protein expression profiles across different subtypes, detecting functional modules within these networks, predicting drug response levels by integrating protein expression with drug sensitivity profiles, and employing perturbation response scanning to rank drug-protein interactions [20]. Applied to gastric cancer, NetSDR identified LAMB2 as a potential target and several compounds as repurposable drugs, demonstrating how network approaches can address disease heterogeneity through precision module identification [20].

Polypharmacology for Multi-Target Engagement

Structure-based virtual screening enables the identification of existing drugs with multi-target potential against clinically relevant target combinations. In a study targeting Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), researchers performed structure-based screening of 3,957 FDA-approved molecules against three key targets: LSD1 (epigenetic regulator), BCL-2 (apoptosis regulator), and mutant IDH1 (metabolic enzyme) [21]. This approach identified three compounds—DB16703 (Belumosudil), DB08512, and DB16047 (Elraglusib)—with high binding affinities across all three targets and favorable pharmacokinetic profiles [21]. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the structural stability of these ligand-protein complexes, demonstrating how single molecular scaffolds can simultaneously modulate epigenetic, apoptotic, and metabolic pathways—a hallmark of advanced polypharmacology design [21].

Natural Products and Traditional Medicine

Network pharmacology has proven particularly valuable for elucidating the polypharmacological mechanisms of natural products and traditional medicines, which often exert therapeutic effects through synergistic multi-target actions [19] [16]. Studies on plant secondary metabolites with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties have consistently identified convergence on common molecular mechanisms despite diverse chemical structures [19]. For antioxidant activities, the Nrf2/KEAP1/ARE pathway emerged as the most frequently validated mechanism, while anti-inflammatory mechanisms consistently involved NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT pathways [19]. Key targets including AKT1, TNF-α, COX-2, NFKB1, and RELA were repeatedly identified across studies, demonstrating how network approaches can decode the complex bioactivities of natural compounds that have evolved through millennia of ecological adaptation [19] [16].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Pharmacology

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | DrugBank, TCMSP, PharmGKB, STITCH, ChEMBL | Provide curated drug-target-disease association data for network construction |

| Network Analysis Platforms | Cytoscape, STRING, NeDRex | Enable network visualization, analysis, and module detection |

| Protein-Protein Interaction Databases | BioGRID, IntAct, MINT | Supply experimentally verified protein interaction data for interactome construction |

| Molecular Docking & Simulation | AutoDock Vina, GROMACS, SwissParam | Facilitate structure-based validation of predicted drug-target interactions |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | pkCSM, SwissADME | Enable early assessment of pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles for candidate drugs |

| Literature Mining Resources | OpenAlex, PubMed | Provide access to scientific literature for citation network analysis and knowledge extraction |

Network theory provides a robust conceptual and computational framework for advancing polypharmacology and drug repurposing strategies. The quantitative comparison of methodological approaches reveals that graph embedding techniques, network proximity metrics, and literature-based similarity measures each offer distinct advantages depending on the specific repurposing scenario. The consistent finding that topologically separated drug targets that both hit the disease module (Complementary Exposure) correlate with therapeutic efficacy provides a crucial design principle for rational drug combination development [18]. Similarly, the demonstration that link prediction methods can achieve >0.95 AUC in cross-validation studies underscores the power of network-based approaches for identifying single-drug repurposing opportunities [4].

As the field progresses, the integration of multiple methodologies—combining network topology with pharmacological insight, structural information, and clinical data—promises to further enhance prediction accuracy and clinical translatability. The development of subtype-specific frameworks like NetSDR addresses the critical challenge of disease heterogeneity [20], while structure-based polypharmacology screening enables rational design of multi-target therapies [21]. Together, these network-based approaches represent a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving beyond reductionist single-target models to embrace the complexity of biological systems and their therapeutic modulation.

The identification of disease modules and their spatial relationships within biological networks represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery. Traditional drug development, notorious for its prolonged duration of 10–15 years and costs exceeding $500 million, is increasingly being supplemented by computational approaches that systematically map the complex interactions between biomolecules [22] [23]. Drug repurposing, which identifies new therapeutic uses for existing drugs, has emerged as a particularly efficient alternative, leveraging established medications to reduce risks and accelerate development timelines [22]. At the heart of this transformation is the recognition that cellular function arises not from isolated molecules but from intricate networks of interactions, and that diseases often result from perturbations of these networks rather than single gene defects [24] [25].

Biological networks provide a mathematical framework to represent complex systems, with nodes representing biological entities (genes, proteins, drugs) and edges representing their interactions, associations, or functional relationships [24] [4]. The fundamental premise underlying network medicine is that disease-associated genes or proteins are not randomly distributed within these networks but cluster into functional modules—groups of molecules that work together to perform specific biological processes [24]. Diseases can therefore be conceptualized as localized perturbations within specific network modules, and the identification of these disease modules provides a powerful approach for understanding pathophysiology and identifying therapeutic targets [23].

This guide systematically compares the leading computational methodologies that leverage network-based approaches for drug target identification and drug repurposing, evaluating their underlying principles, performance metrics, and practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Network-based approaches for drug discovery can be broadly categorized into several methodological frameworks, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below provides a comparative overview of four prominent approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Network-Based Methodologies for Drug Target Identification and Repurposing

| Methodology | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Network Models [26] | Integrates multisource data (drugs, proteins, diseases, side effects) into unified network; uses meta-path aggregation | Drug structures, protein sequences, disease associations, side effect data | High accuracy (AUROC: 0.966); captures complex cross-entity relationships | Computationally intensive; requires extensive data integration |

| Topological Perturbation Analysis [27] | Applies persistent Laplacians to identify key network nodes through multiscale topological differentiation | Transcriptomic data, protein-protein interaction networks | Identifies structurally central genes; handles cellular heterogeneity | Complex mathematical framework; limited validation in clinical settings |

| Knowledge Graph Embedding [22] | Represents biomedical knowledge as graph embeddings; uses recommendation systems for prediction | Drug-disease associations, molecular structures, clinical data | Handles cold-start scenarios; integrates semantic similarity | Dependent on knowledge graph completeness; black-box predictions |

| Link Prediction Algorithms [4] | Applies network science to identify missing edges (drug-disease pairs) in bipartite networks | Known drug-disease indications, network topology | High performance (AUC >0.95); purely topology-based | Limited pharmacological insight; depends on network quality |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Quantitative evaluation of these methodologies reveals significant differences in their predictive performance across standard benchmarks:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Network-Based Drug Repurposing Approaches

| Methodology | Model/Implementation | AUROC | AUPR | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiview Path Aggregation (MVPA-DTI) | Heterogeneous network with molecular transformer and Prot-T5 | 0.966 | 0.901 | Drug-target interaction prediction; KCNH2 target screening | [26] |

| Unified Knowledge-Enhanced Framework (UKEDR) | PairRE + Attentional Factorization Machines | 0.950 | 0.960 | Cold-start drug repositioning; clinical trial prediction | [22] |

| Bipartite Link Prediction | Graph embedding + network model fitting | >0.95 | ~1000x random baseline | Drug-disease association prediction; repurposing candidate identification | [4] |

| AI-Enabled Network Analysis | Combined AI + gene regulatory network analysis | Experimental validation in model organisms | - | Rett syndrome; vorinostat repurposing | [25] |

The MVPA-DTI framework demonstrates how integrating 3D molecular structures with protein sequences through specialized transformers can achieve state-of-the-art performance in drug-target interaction prediction [26]. In a case study on the KCNH2 target relevant to cardiovascular diseases, this model successfully identified 38 interacting drugs from 53 candidates, with 10 already validated in clinical use [26].

For cold-start scenarios where predictions are needed for new entities not present in the training data, the UKEDR framework utilizes semantic similarity-driven embedding to map unseen nodes into the knowledge graph embedding space, significantly outperforming traditional approaches [22]. This capability is particularly valuable for predicting interactions for newly discovered targets or novel chemical compounds.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Heterogeneous Network Construction and Meta-Path Aggregation

The construction of biological networks for drug repurposing follows systematic protocols that vary by methodology:

Protocol 1: Heterogeneous Network Construction for DTI Prediction [26]

- Feature Extraction: Utilize molecular attention transformer to extract 3D conformation features from drug chemical structures and Prot-T5 (a protein-specific large language model) to extract biophysically relevant features from protein sequences.

- Network Assembly: Integrate drugs, proteins, diseases, and side effects from multisource heterogeneous data into a unified graph structure.

- Meta-Path Implementation: Design meta-paths that capture meaningful biological relationships (e.g., drug-protein-disease, drug-side effect-protein).

- Message Passing: Implement a meta-path aggregation mechanism that dynamically integrates information from both feature views and biological network relationship views.

- Prediction: Train the model to optimize weight distribution by incorporating both network topology and biological prior knowledge during message passing.

Protocol 2: Multiscale Topological Differentiation for Key Gene Identification [27]

- Meta-analysis: Aggregate multiple transcriptomic datasets from public repositories (e.g., GEO database).

- Differential Expression: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using standardized tools (DESeq2, Seurat).

- Network Construction: Build protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks from DEGs.

- Topological Analysis: Apply persistent Laplacians to extract topological signatures from PPI networks across multiple scales.

- Gene Prioritization: Identify structurally central genes based on multiscale topological importance.

- Target Validation: Cross-reference prioritized genes with DrugBank to compile repurposing candidate lists.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for network-based drug repurposing:

Figure 1: Workflow for Network-Based Drug Repurposing

AI-Enabled Target Identification and Validation

The integration of artificial intelligence with network analysis has produced sophisticated protocols for target identification:

Protocol 3: AI-Enabled Drug Prediction with Experimental Validation [25]

- Computational Prediction: Combine artificial intelligence with human gene regulatory network analysis for target-agnostic drug discovery.

- Animal Model Generation: Create disease models using CRISPR-edited organisms (e.g., Xenopus laevis tadpoles) with specific gene disruptions.

- Phenotypic Screening: Assess whole-body efficacy for clinically relevant metrics in phenotypically diverse in vivo models.

- Therapeutic Validation: Validate therapeutic efficacy in mammalian models (e.g., MeCP2-null mice expressing the target phenotype).

- Mechanism Elucidation: Conduct gene network analysis to reveal putative therapeutic mechanisms based on molecular impacts.

This approach successfully identified vorinostat as a repurposing candidate for Rett syndrome, demonstrating efficacy across both central nervous system and non-CNS abnormalities when dosed after symptom onset [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementation of network-based drug discovery requires specialized computational tools and biological resources. The following table catalogs essential solutions referenced in recent studies:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Network-Based Drug Discovery

| Category | Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Analysis | Cytoscape [28] | Biological network visualization and analysis | PPI network analysis; module identification |

| Graph Embedding | node2vec [4] | Network representation learning | Low-dimensional embedding of biological networks |

| Deep Learning | Molecular Attention Transformer [26] | 3D molecular structure feature extraction | Drug-target interaction prediction |

| Protein Language Models | Prot-T5 [26] | Protein sequence representation | Biophysically relevant feature extraction from sequences |

| Knowledge Graphs | PairRE [22] | Knowledge graph embedding for relations | Cold-start drug repositioning |

| Topological Analysis | Persistent Laplacians [27] | Multiscale topological differentiation | Key gene identification in PPI networks |

| Omics Integration | Multidimensional scaling [28] | Network layout optimization | Cluster detection in biological networks |

| Validation Databases | DrugBank [27] | Drug-target-disease association repository | Cross-referencing repurposing candidates |

Implementation Considerations

When selecting and implementing these tools, researchers should consider several practical aspects. For visualization tasks, Cytoscape provides extensive plugins for biological network analysis but may require complementary tools for very large-scale networks, where adjacency matrix representations might be more suitable [28]. For feature extraction, transformer-based models like Prot-T5 require significant computational resources but provide superior protein representations compared to traditional sequence encoding methods [26]. In validation workflows, integration with established databases like DrugBank is essential for contextualizing predictions within existing biological knowledge [27].

The following diagram illustrates the spatial relationships in a hypothetical disease module and candidate drug targets:

Figure 2: Spatial Relationships in a Disease Module with Drug Targets

Network-based approaches for identifying disease modules and drug targets have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in predicting drug-disease associations, with leading methods achieving AUROC scores exceeding 0.95 [26] [4]. The spatial relationships within biological networks provide critical insights for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying repurposing opportunities that might remain obscure through reductionist approaches.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals that heterogeneous network models excel in integrating diverse data sources for comprehensive predictions, while topological methods offer unique advantages in identifying structurally critical nodes, and knowledge graph embeddings effectively handle cold-start scenarios. Despite these advances, challenges remain in computational scalability, data integration from increasingly diverse omics technologies, and biological interpretation of complex models [24].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on incorporating temporal and spatial dynamics of biological networks, improving model interpretability through attention mechanisms and explainable AI, and establishing standardized evaluation frameworks for direct comparison of approaches [24] [23]. As these computational methods mature, their integration with experimental validation will be essential for translating network-based predictions into clinically actionable repurposing strategies, ultimately accelerating drug development and expanding therapeutic options for complex diseases.

The practice of drug repurposing—finding new therapeutic uses for existing drugs—has evolved dramatically. It has moved from relying on serendipitous discoveries to employing sophisticated, systematic computational approaches. This transformation is largely driven by the recognition that developing new drugs de novo is exceptionally costly and time-consuming, whereas repurposing offers a viable, efficient alternative [4] [6]. Early repurposing successes were often accidental; however, the sheer scale of millions of potential drug-disease combinations makes a systematic method essential for narrowing the search space [29] [6]. This guide evaluates the performance of modern network analysis methodologies against traditional and other computational techniques, providing a comparative analysis grounded in experimental data and specific protocols.

The Rise of Systematic Approaches: Network Analysis

Network science provides a powerful mathematical framework to represent and analyze complex biological and pharmacological systems [4] [6]. In the context of drug repurposing, a drug-disease network is typically constructed as a bipartite graph, consisting of two distinct types of nodes: drugs and diseases [4]. The edges connecting a drug node to a disease node represent a known, approved therapeutic indication for that condition.

The core hypothesis is that these networks are incomplete, and link prediction algorithms can systematically identify "missing" edges, which represent promising, novel candidates for drug repurposing [4] [6]. This transforms the repurposing problem into a computable task of forecasting new connections within a graph, moving far beyond chance discovery.

Key Network Concepts and Terminology

The following diagram illustrates the core structure of a drug-disease network and the conceptual workflow for predicting new therapeutic uses.

Diagram 1: Bipartite drug-disease network with a predicted link.

Understanding network topology is key to analysis. Key properties include [30]:

- Nodes and Edges: Nodes represent entities (e.g., a specific drug or disease), while edges represent the relationships between them (e.g., a treatment indication).

- Centrality: Metrics that identify the most important or influential nodes within a network. For example, a drug with high degree centrality (connected to many diseases) might be a particularly versatile repurposing candidate.

- Density: The proportion of possible connections that actually exist in the network, which can indicate the network's completeness.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Repurposing Predictions

To objectively compare the performance of different repurposing approaches, a standardized evaluation protocol is essential. The following workflow outlines a robust methodology based on cross-validation, a cornerstone technique for validating predictive models [4] [6].

Diagram 2: Cross-validation workflow for algorithm evaluation.

Detailed Methodology

- Network Assembly: Compile a comprehensive, gold-standard network of known drug-disease therapeutic indications. This serves as the ground-truth dataset. For example, Polanco and Newman (2025) created a network of 2,620 drugs and 1,669 diseases using a combination of machine-readable databases, natural-language processing, and hand curation [4] [6].

- Data Splitting: Randomly select a small fraction (e.g., 10-20%) of the known edges in the network to be removed and set aside as a test set. The remaining network, with these edges missing, is used for training the prediction algorithm.

- Algorithm Execution: Run the link prediction algorithm on the incomplete training network. The algorithm generates a ranked list of potential new drug-disease edges, scored by their likelihood of existing.

- Performance Measurement: The algorithm's predictions are compared against the held-out test set of known edges. Standard metrics like the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) and Average Precision are calculated to quantify how well the algorithm identified the missing links [4].

Performance Comparison of Repurposing Methodologies

This section provides a objective comparison of the performance of various drug repurposing methodologies, from traditional approaches to modern network-based algorithms.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparative performance of drug repurposing prediction methodologies.

| Methodology | Representative Study / Algorithm | Dataset Scale (Drugs/Diseases) | Key Performance Metrics | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Similarity-Based | Gottlieb et al. | 593 / 313 | Moderate performance; lower than advanced ML methods [4] | Limited by the quality and type of similarity data used (e.g., chemical structure, side effects). |

| Indirect Inference & Label Propagation | Huang et al. | Not Specified | Medically relevant predictions; overall low performance measures [4] | Relies on heterogeneous data integration; predictions can be noisy and non-specific. |

| Collaborative Filtering | Wang et al. | 963 / 1263 | Demonstrated promise of network-based techniques [4] | Early study with a small dataset; limited number of predictions made. |

| Hybrid (Multi-data) | Zhang et al. | Smaller dataset | Predicts therapeutic and non-therapeutic associations [4] | Includes side-effects; different focus than pure therapeutic indication prediction. |

| Graph Embedding & Model Fitting | Polanco & Newman | 2620 / 1669 | AUC-ROC > 0.95; Precision ~1000x better than chance [4] [6] | Purely network-based; does not incorporate pharmacological data. |

Comparative Analysis of Experimental Outcomes

The data in Table 1 reveals a clear performance hierarchy. Similarity-based methods and those using indirect inference lay the groundwork but achieve only moderate to low performance, struggling with specificity and data integration [4]. In contrast, modern systematic network approaches, particularly those utilizing graph embedding and statistical network model fitting, demonstrate a significant leap in predictive power [4] [6]. The high AUC-ROC (above 0.95) and exceptional precision (nearly a thousand times better than random chance) reported in the 2025 study by Polanco and Newman highlight the efficacy of treating drug repurposing as a sophisticated link prediction task on a carefully constructed bipartite network. This performance is achieved using the network structure alone, suggesting substantial potential for further improvement by integrating additional pharmacological data layers into a hybrid strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

To implement the network-based repurposing methodologies described, researchers require a specific set of computational and data resources.

Table 2: Essential tools and resources for network-based drug repurposing research.

| Item / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Gold-Standard Drug-Disease Indications | Data | Serves as the ground-truth bipartite network for training and testing prediction algorithms [4] [6]. |

| Link Prediction Algorithms | Software | Core computational methods for identifying missing edges. Includes graph embedding and network model fitting [4]. |

| Network Analysis Tools (e.g., Gephi) | Software | Specialized software for network visualization and analysis of properties like centrality and density [31]. |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Protocol | Standard experimental procedure for objectively evaluating and comparing algorithm performance [4] [6]. |

| Natural Language Processing Tools | Software | Used to parse textual data from scientific literature and databases to assist in building comprehensive networks [4]. |

Computational Methodologies: Network-Based Algorithms and Implementation Frameworks

In the field of network science, link prediction has emerged as a paradigmatic problem with tremendous real-world applications, aiming to infer missing or future links based on currently observed network structures [32] [33]. Within pharmaceutical research, particularly in drug repurposing, these algorithms provide a powerful computational framework for identifying new therapeutic uses for existing drugs by analyzing complex drug-disease networks [4] [34]. Drug repurposing offers a cost-effective alternative to traditional drug development, potentially reducing costs from $2.6 billion to approximately $300 million per drug and cutting development time from 10-15 years to as little as 3-6 years [34].

Link prediction approaches for drug repurposing typically view the problem as identifying missing edges in bipartite networks where nodes represent drugs and diseases, and edges represent known therapeutic treatments [4]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of two dominant algorithmic families—graph embedding and network model fitting—evaluating their performance, experimental protocols, and applicability for network-based drug repurposing predictions.

Algorithmic Approaches and Comparative Performance

Graph Embedding Methods

Graph embedding methods learn low-dimensional vector representations of nodes that preserve structural information, enabling link prediction through geometric operations in the embedded space [35]. These techniques have gained significant traction for knowledge graph completion and biological network analysis.

Translational models like TransE operate on the principle that relationships correspond to translations in the embedding space (if (h, r, t) holds, then h + r ≈ t) [35]. Semantic matching models such as DistMult use multiplicative score functions to capture semantic similarities between entities [35]. Neural network-based encoders leverage deep learning architectures to learn complex relational patterns [35].

For heterogeneous biological networks containing multiple node and relationship types, meta-path-based methods like Metapath2vec and its enhanced variant SW-Metapath2vec have demonstrated particular effectiveness [36]. These algorithms use guided random walks following predefined meta-paths to capture both structural and semantic information, with SW-Metapath2vec incorporating local structural weighting to further improve performance [36].

Recent advancements include dynamic graph embeddings that model temporal evolution in networks. Mamba-based models, with their linear computational complexity, have shown promising results in capturing long-range dependencies in temporal graph data while offering significant efficiency gains over transformer-based approaches [37].

Network Model Fitting Approaches

Network model fitting methods take a fundamentally different approach by constructing probabilistic graphical models that explain the observed network structure, then using these models to predict missing connections.

The degree-corrected stochastic block model is among the most prominent approaches, grouping nodes into blocks with characteristic connection probabilities while preserving degree sequences [4]. This method effectively captures the community structure inherent in biological networks, where drugs and diseases often form functional clusters.

Hierarchical models represent another important category, organizing networks into nested structures that reflect multi-scale relational patterns [4]. These approaches can reveal the hierarchical organization of drug-disease relationships, from broad therapeutic categories to specific indications.

Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Link Prediction Algorithms on Drug-Disease Networks

| Algorithm Category | Specific Methods | AUC-ROC | Average Precision | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Embedding | Graph Embedding (General) | >0.95 [4] | ~1000x better than chance [4] | Captures complex relational patterns; Handles heterogeneous networks | Requires substantial computational resources |

| SW-Metapath2vec | Significantly outperforms benchmarks [36] | High resilience to node removal [36] | Effective for heterogeneous networks; Incorporates local structure | Complex implementation | |

| Mamba-based dynamic embeddings | Comparable/superior to transformers [37] | N/A | Linear complexity; Efficient for long sequences | Emerging technique, less validated | |

| Network Model Fitting | Degree-corrected stochastic block model | >0.95 [4] | ~1000x better than chance [4] | Reveals community structure; Statistical interpretability | May oversimplify complex relationships |

| Similarity-Based | Local similarity metrics | Moderate [4] | Lower than embedding methods [4] | Computational simplicity; Interpretability | Limited performance on complex networks |

The performance comparison reveals that both graph embedding and network model fitting can achieve exceptional performance in drug-disease link prediction, with area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC) exceeding 0.95 and average precision almost a thousand times better than chance in optimal configurations [4]. This impressive performance is achieved using purely network-based methods without incorporating additional pharmacological data, suggesting potential for further improvement through hybrid approaches [4].

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Frameworks

Standard Cross-Validation Protocol

The standard experimental framework for evaluating link prediction algorithms in drug repurposing involves cross-validation on observed drug-disease networks:

This protocol begins with assembling a comprehensive drug-disease network, such as the one described by Polanco and Newman containing 2620 drugs and 1669 diseases [4]. The core validation step involves randomly removing a fraction of edges (typically 10-20%) and treating them as positive test examples, while the remaining network serves as training data [4] [33]. The algorithm's performance is measured by its ability to identify these held-out edges among all possible non-edges.

Advanced Evaluation Considerations

Recent research has highlighted several critical factors that impact link prediction evaluation:

Prediction type differentiation distinguishes between missing link prediction (identifying unobserved connections in existing data) and future link prediction (forecasting new connections over time) [33]. These scenarios require different experimental setups, as randomly removed edges may not accurately represent true future links.

Distance-controlled evaluation addresses the fact that most real-world connections form between nearby nodes in networks [33]. Local methods specifically target node pairs with geodesic distance of 2 (sharing common neighbors), while global methods consider more distant pairs. Proper evaluation should control for this distance factor when comparing algorithms.

Class imbalance awareness recognizes that real missing or future links are vastly outnumbered by non-existent connections [33]. While AUC-ROC has been traditionally popular, skew-sensitive metrics like Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) or Precision@k may provide more realistic performance assessment, particularly for early retrieval performance crucial in recommendation scenarios.

Heterogeneous Network Specific Protocols

For heterogeneous networks containing multiple node types (e.g., drugs, diseases, proteins, genes), specialized evaluation protocols are employed:

The SW-Metapath2vec algorithm exemplifies this approach, beginning with defining semantically meaningful meta-paths that guide random walks through the heterogeneous network [36]. These meta-path traces receive structural weights based on their local network importance before feeding into the embedding learning process. Potential connections are then translated into cosine similarity measurements between the resulting embedded vectors [36].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Link Prediction Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-Disease Network Dataset | Data | Provides known drug-disease indications for training and evaluation | Foundation for drug repurposing predictions [4] |

| Meta-path Definitions | Methodology | Guides random walks in heterogeneous networks | Capturing semantic relationships in complex biological data [36] |

| Graph Embedding Libraries (Node2vec, GraphSAGE) | Software | Implements graph representation learning algorithms | Creating low-dimensional node embeddings for link prediction [32] |

| Stochastic Block Model Implementations | Software | Fits network models to identify community structure | Discovering functional modules in drug-disease networks [4] |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Methodology | Evaluates algorithm performance robustly | Comparing prediction accuracy across different approaches [4] [33] |

| Temporal Graph Processing | Software | Handles time-evolving network data | Modeling dynamic drug-disease relationships over time [37] |

Both graph embedding and network model fitting approaches demonstrate impressive capability for drug repurposing prediction, with top-performing algorithms in both categories achieving AUC-ROC scores above 0.95 and precision nearly a thousand times better than random guessing [4]. The choice between these approaches depends on specific research requirements: graph embedding methods excel at capturing complex relational patterns in heterogeneous networks, while network model fitting offers greater statistical interpretability and insight into the community structure of drug-disease relationships.

Future directions likely involve hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both methodologies, potentially incorporating additional biological data such as drug targets, protein-protein interactions, and disease mechanisms. As noted by Polanco and Newman, network-based methods achieve their impressive performance using purely topological information, suggesting substantial opportunity for enhancement through integration with pharmacological knowledge [4]. The continuing development of more efficient algorithms, particularly for dynamic and heterogeneous networks, promises to further advance the application of link prediction in accelerating drug repurposing and addressing unmet medical needs.

Network proximity measures have emerged as powerful computational tools for predicting new therapeutic uses for existing drugs. By mapping drugs and diseases within a unified network framework—such as the human interactome, a comprehensive map of protein-protein interactions—researchers can quantify the relationship between a drug's targets and a disease's associated genes [38]. The core premise is that drugs whose targets are in close network proximity to disease modules are more likely to exert therapeutic effects on that disease [4] [38]. This approach transforms drug repurposing into a link prediction problem on bipartite networks of drugs and diseases [4].

Different proximity metrics capture distinct aspects of the network relationship, leading to varied predictions and interpretations. This guide provides an objective comparison of four fundamental proximity measures—minimum, maximum, mean, and mode distances—evaluating their performance, optimal use cases, and implementation in drug repurposing pipelines. As the field moves toward addressing complex, multifactorial diseases like aging through network medicine, selecting appropriate proximity metrics becomes increasingly critical for identifying interpretable, biologically plausible repurposing candidates [38].

Theoretical Foundations of Proximity Metrics

Network proximity between a drug ( D ) and a disease ( S ) is calculated based on the shortest path lengths ( d(t,s) ) between each drug target node ( t \in T ) (the set of protein targets of drug ( D )) and each disease gene node ( s \in S ) (the set of genes associated with a disease or hallmark) [38]. Each metric summarizes these path lengths differently:

Minimum Distance: ( P{min} = \min{t \in T, s \in S} d(t,s) ) Captures the closest encounter between drug targets and disease modules.

Maximum Distance: ( P{max} = \max{t \in T, s \in S} d(t,s) ) Reflects the furthest separation between drug targets and disease modules.

Mean Distance: ( P{mean} = \frac{1}{|T||S|} \sum{t \in T} \sum_{s \in S} d(t,s) ) Provides an average overall relationship between targets and disease genes.

Mode Distance: ( P_{mode} = \text{Mode}{d(t,s) \forall t \in T, s \in S} ) Identifies the most frequent shortest path length in the target-disease set.

These measures operate on the fundamental discovery that genes associated with specific diseases or hallmarks of aging form statistically significant, interconnected modules within the human interactome [38]. The existence of these hallmark modules enables the application of network proximity for systematic drug repurposing.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each proximity metric based on network medicine research:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Network Proximity Metrics

| Metric | Theoretical Interpretation | Best Use Cases | Performance Considerations | Computational Complexity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Distance | Measures direct overlap or closest approach between drug targets and disease module | Initial screening for high-potential candidates; diseases with well-defined modules [38] | High sensitivity but may overpredict for highly connected targets [38] | O( | T | × | S | ) for unweighted graphs |

| Maximum Distance | Captures worst-case separation between drug and disease in network | Identifying comprehensively close interventions; excluding remote candidates | Conservative approach; may miss partially effective drugs [38] | O( | T | × | S | ) for unweighted graphs |

| Mean Distance | Provides average closeness across all target-disease pairs | Balanced assessment for multi-target drugs; polypharmacology studies [38] | Robust to outliers but sensitive to extreme values [38] | O( | T | × | S | ) for unweighted graphs |