Navigating the Maze: Advanced Strategies for Addressing High Dimensionality in Biomedical Network Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with high-dimensional data in network analysis.

Navigating the Maze: Advanced Strategies for Addressing High Dimensionality in Biomedical Network Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with high-dimensional data in network analysis. It explores the foundational challenges posed by the 'curse of dimensionality' in datasets like transcriptomics and proteomics, detailing a suite of feature selection and projection techniques from PCA to autoencoders. The content covers practical methodological applications in predicting drug-target interactions and extracting functional genomics insights, alongside crucial troubleshooting for data sparsity and overfitting. Finally, it presents a rigorous framework for validating and comparing dimensionality reduction methods, using real-world case studies from cancer research and drug repurposing to equip scientists with the tools needed to enhance discovery and decision-making in complex pharmacological systems.

The High-Dimensionality Challenge: Understanding Data Complexity and the Curse of Dimensionality in Biomedical Networks

Defining High-Dimensionality in Pharmacological and Omics Data Contexts

FAQ: Understanding High-Dimensional Data

What constitutes a "high-dimensional" dataset in pharmacological and omics research?

High-dimensional data refers to datasets where each subject or sample has a vast number of measured variables or characteristics associated with it. In practical terms, this occurs when the number of features (p) far exceeds the number of observations or samples (n), creating what statisticians call "the curse of dimensionality" [1] [2].

In omics studies, examples include data from tissue exome sequencing, copy number variation (CNV), DNA methylation, gene expression, and microRNA (miRNA) expression, where each sample may have thousands to millions of measured molecular features [3]. The central challenge with such data is determining how to make sense of this high dimensionality to extract useful biological insights and knowledge [1].

What specific challenges does high-dimensionality create for data analysis?

High-dimensional omics data presents several distinct analytical challenges:

- Data Heterogeneity: Multi-omics studies integrate data that differ in type, scale, and source, with thousands of variables but only a few samples [3]

- Noise and Bias: Biological datasets are complex, noisy, biased, and heterogeneous, with potential errors from measurement mistakes or unknown biological deviations [3]

- Computational Scalability: Many analytical methods struggle with computational efficiency when handling large-scale multi-omics datasets [3]

- Interpretability Challenges: Maintaining biological interpretability while increasing model complexity remains a significant challenge [3]

How do network-based approaches help manage high-dimensional omics data?

Network-based methods transform high-dimensional omics data into biological networks where nodes represent individual molecules (genes, proteins, DNA) and edges reflect relationships between them. This approach aligns with the organizational principles of biological systems and provides several advantages [3]:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Networks provide a framework for reducing thousands of molecular measurements to manageable interaction patterns

- Integration Framework: Biological networks serve as foundational frameworks for integrating diverse omics data types [3]

- Pattern Recognition: Studying network structures across biological systems helps discover universal fundamentals of multi-omics data and reveals global patterns [3]

Table 1: Dimensionality Characteristics Across Data Types

| Data Type | Typical Sample Size | Typical Feature Number | Dimensionality Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data | Dozens-Hundreds | Millions of SNPs | Extreme (p>>n) |

| Transcriptomic Data | Dozens-Hundreds | Thousands of genes | High (p>>n) |

| Proteomic Data | Dozens | Hundreds-Thousands of proteins | High (p>>n) |

| Metabolomic Data | Dozens-Hundreds | Hundreds of metabolites | Moderate-High |

| Conventional Pharmacological Data | Hundreds-Thousands | Dozens of parameters | Low-Moderate |

Troubleshooting Guides for High-Dimensional Data Analysis

Problem: Lack of Assay Window in High-Throughput Screening

Issue: Complete absence of measurable assay window in high-dimensional pharmacological screening.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Instrument Setup: Confirm proper instrument configuration using manufacturer setup guides [4]

- Check Filter Configuration: For TR-FRET assays, ensure exact recommended emission filters are used, as filter choice can determine assay success [4]

- Validate Reagent Performance: Test microplate reader setup using already purchased reagents before beginning experimental work [4]

- Confirm Compound Solubility: Ensure appropriate drug solvents are used at non-toxic concentrations, with attention to compound stability [5]

Problem: Inconsistent Results in High-Dimensional Omics Studies

Issue: Poor reproducibility or inconsistent findings across omics experiments.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Severe Testing Framework (STF): Apply systematic means to trim wild-grown omics studies constructively [2]

- Adopt Cyclic Analysis: Utilize iterative deductive-abductive frameworks where prediction and postdiction cycle continuously [2]

- Validate Cell Lines: Use authenticated cell lines with short tandem repeat profiling to ensure data validity [5]

- Standardize Pre-analytical Conditions: Predetermine and record basic conditions including plating density, proliferative rate, and medium specifications [5]

Problem: Integration Challenges in Multi-Omics Data

Issue: Difficulty integrating diverse omics data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) effectively.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Select Appropriate Network Method: Choose from four primary network-based integration approaches: network propagation/diffusion, similarity-based approaches, graph neural networks, or network inference models [3]

- Establish Biological Relevance: Evaluate contributions of specific network types (gene regulatory networks, protein interaction networks, metabolic reaction networks) to your specific drug discovery application [3]

- Address Data Heterogeneity: Utilize methods specifically designed to handle data differing in type, scale, and source [3]

- Focus on Interpretability: Prioritize biological interpretability alongside computational performance when selecting integration methods [3]

Table 2: Network-Based Integration Methods for High-Dimensional Omics Data

| Method Category | Best Application | Dimensionality Handling | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Propagation/Diffusion | Drug target identification | Excellent for sparse data | May oversmooth signals |

| Similarity-Based Approaches | Drug repurposing | Handers heterogeneous features | Computational intensity |

| Graph Neural Networks | Complex pattern detection | Superior for large networks | "Black box" interpretation |

| Network Inference Models | Mechanistic understanding | Direct biological mapping | Model specification sensitivity |

Experimental Protocols for High-Dimensional Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration

Methodology:

- Literature Search Strategy: Conduct systematic searches across major scientific databases using key terms: ("multi-omics" OR "multiomics" OR "omics fusion") AND ("network analysis" OR "biological network") AND ("drug discovery" OR "drug prediction") [3]

- Data Collection: Collect multi-omics data spanning at least two omics layers (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, DNA methylation, copy number variations) [3]

- Network Construction: Abstract interactions among various omics into network models where nodes represent molecules and edges reflect relationships [3]

- Method Application: Apply appropriate network-based integration method based on specific drug discovery application (target identification, response prediction, or drug repurposing) [3]

- Validation: Evaluate performance using standardized metrics and biological validation [3]

Protocol 2: Severe Testing Framework for Omics Studies

Methodology:

- Hypothesis Formulation: Develop testable hypotheses through abductive reasoning, which is essential for creating new hypotheses [2]

- Cyclic Testing: Implement continuous cycles of prediction (hypothetico-deductive process) and postdiction (abductive process) [2]

- Iterative Corroboration: Conduct multiple testing iterations to slowly increase confidence in hypotheses over time [2]

- Falsification Assessment: Design experiments capable of falsifying hypotheses, recognizing the asymmetry between verification and falsification [2]

- Asymptotic Evaluation: Continue testing iterations to approach asymptotic confidence in hypotheses [2]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-Dimensional Data Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Authenticated Cell Lines | Ensure data validity | Verify with short tandem repeat profiling [5] |

| DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide) | Compound solubilization | Test for non-toxic concentrations; confirm compound stability [5] |

| TR-FRET Compatible Reagents | High-throughput screening | Verify exact emission filter compatibility [4] |

| Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) | Study drug resistance | Characterize with appropriate markers [5] |

| Endothelial Cell Lines | Study metastasis mechanisms | Use transformed human umbilical vein endothelial cells [5] |

| Development Reagents | Signal detection | Titrate according to Certificate of Analysis [4] |

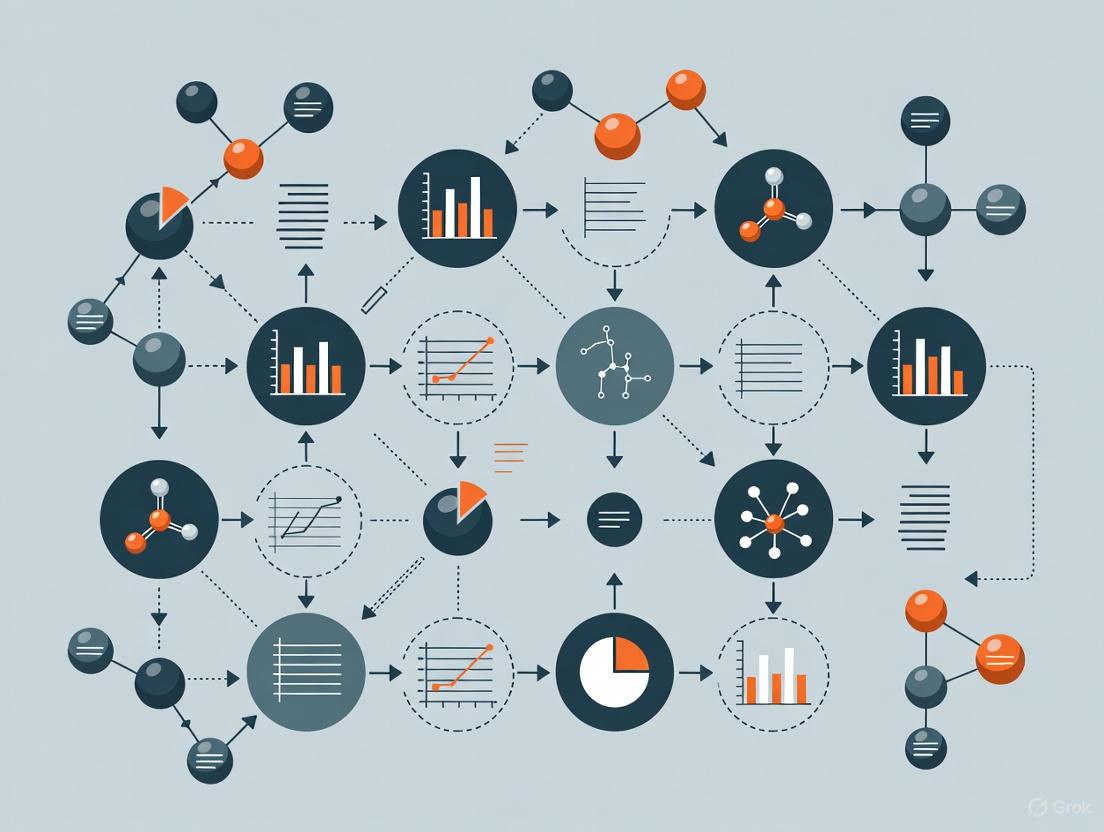

Visualization Diagrams

High-Dimensional Data Analysis Workflow

Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration Methods

Scientific Reasoning Framework for Omics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the core manifestations of the Curse of Dimensionality in network analysis? The Curse of Dimensionality primarily manifests as two interconnected problems in high-dimensional data analysis:

- Data Sparsity: As the number of dimensions increases, data points become increasingly spread out, residing in a vast, mostly empty volume. This makes it difficult to find dense regions or identify meaningful patterns, as the available data becomes insufficient to cover the space adequately [6].

- Distance Concentration: In very high-dimensional spaces, the contrast between the nearest and farthest neighbors from a given query point diminishes. This means that the concept of "proximity" or "similarity," which is fundamental to many clustering and classification algorithms, becomes less meaningful and can severely hinder analysis [6].

FAQ 2: My dataset has thousands of features but only a few hundred samples. Are there specialized methods for this High-Dimension, Low-Sample-Size (HDLSS) scenario? Yes, HDLSS problems require specific non-parametric methods that do not rely on large-sample assumptions. Network-Based Dimensionality Analysis (NDA) is a novel, nonparametric technique designed for this exact challenge. It works by creating a correlation graph of variables and then using community detection algorithms to identify modules (groups of highly correlated variables). The resulting latent variables are linear combinations of the original variables, weighted by their importance within the network (eigenvector centrality), providing a reduced representation of the data without requiring a pre-specified number of dimensions [7].

FAQ 3: Beyond traditional statistics, are there advanced computational techniques for high-dimensional problems? Yes, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) represent a powerful advancement. A key method for scaling PINNs to arbitrarily high dimensions is Stochastic Dimension Gradient Descent (SDGD). This technique decomposes the gradient of the PDE's residual loss function into pieces corresponding to different dimensions. During each training iteration, it randomly samples a subset of these dimensional components. This makes training computationally feasible on a single GPU, even for tens of thousands of dimensions, by significantly reducing the cost per step [8].

FAQ 4: How can I determine the intrinsic dimensionality of my network data? A geometric approach using hyperbolic space can detect intrinsic dimensionality without a prior spatial embedding. This method models network connectivity and uses the density of edge cycles to infer the underlying dimensional structure. It has revealed, for instance, that biomolecular networks are often extremely low-dimensional, while social networks may require more than three dimensions for a faithful representation [9].

FAQ 5: What are the common pitfalls in feature selection for high-dimensional data? The most common and problematic pitfall is One-at-a-Time (OaaT) Feature Screening. This approach tests each variable individually for an association with the outcome and selects the "winners." Its major flaws include [6]:

- High False Negative Rate: Missing important features that only show significance when considered together with others.

- Overestimated Effect Sizes: "Winning" features are often selected precisely because their effect is overestimated in a given sample (regression to the mean).

- Ignoring Variable Interactions: It fails to account for features that "travel in packs" or function in networks, leading to unstable and poorly performing models.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Cluster Separation in High-Dimensional Space

Symptoms: Clustering algorithms (e.g., K-Means, DBSCAN) fail to identify distinct groups; results are sensitive to parameter tuning and appear random.

Diagnosis: The "curse of dimensionality" is causing distance concentration, making clustering algorithms unable to distinguish between meaningful and noise-based separations [10].

Solution: Apply dimensionality reduction as a preprocessing step.

- Standardize your data by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for each feature [10].

- Choose a reduction technique based on your data:

- Cluster on the reduced data. Perform clustering on the new, lower-dimensional representation (e.g., the first few principal components from PCA). This reduces noise and allows the clustering algorithm to work more effectively [10].

Problem 2: Model Overfitting Despite Using Many Features

Symptoms: Your model performs excellently on training data but generalizes poorly to new, unseen test data.

Diagnosis: The model is learning noise and spurious correlations specific to the training set, a classic sign of overfitting in high-dimensional settings where the number of features (p) is large compared to the number of samples (n) [6].

Solution: Use statistical methods that incorporate shrinkage or regularization.

- Avoid OaaT screening and stepwise selection, as these do not adequately account for the randomness in feature selection and lead to overoptimistic performance estimates [6].

- Employ joint modeling with shrinkage:

- Ridge Regression: Applies a penalty on the sum of squares of coefficients, shrinking them but not to zero. It often has high predictive ability [6].

- Lasso Regression: Applies a penalty on the absolute value of coefficients, which can shrink some coefficients exactly to zero, performing feature selection [6].

- Elastic Net: Combines Lasso and Ridge penalties, offering a balance between feature selection and predictive performance [6].

- Validate correctly: When any form of feature selection or data mining is used, the entire process (including selection) must be repeated within each cross-validation fold to obtain an unbiased estimate of model performance [6].

Problem 3: Unstable Feature Selection

Symptoms: The set of "important" features changes dramatically with small changes in the dataset (e.g., when using different bootstrap samples).

Diagnosis: Feature selection is highly unstable due to collinearity among features and the high-dimensional, low-sample-size nature of the data [6].

Solution: Use bootstrap resampling to assess feature importance confidence.

- Bootstrap Resampling: Take multiple bootstrap samples (samples with replacement) from your original dataset.

- Recompute Importance: For each bootstrap sample, recompute your feature importance measure (e.g., p-value, regression coefficient, variable importance score).

- Rank Features: Rank the features by their importance in each bootstrap sample.

- Analyze Rank Stability: Compute confidence intervals for the rank of each feature. This provides a more honest assessment, showing which features are consistently important and which fall into an uncertain middle ground [6].

Experimental Protocol: Network-Based Dimensionality Analysis (NDA)

Objective: To reduce the dimensionality of a high-dimensional, low-sample-size (HDLSS) dataset by treating variables as nodes in a network and identifying tightly connected communities.

Methodology:

- Construct Correlation Graph: Calculate the correlation matrix between all pairs of variables. Define a graph where nodes represent variables, and edges are drawn between pairs with a correlation magnitude above a defined threshold.

- Detect Communities: Apply a modularity-based community detection algorithm (e.g., the Louvain method) to the correlation graph. This partitions the variables into modules (communities) where variables within a module are more densely connected to each other than to variables in other modules [7].

- Define Latent Variables (LVs): For each identified module, create a single latent variable. This LV is calculated as the linear combination of the variables within the module, weighted by their eigenvector centrality—a network measure of a node's influence within its module [7].

- Optional Variable Selection: Prune the network by ignoring variables with very low eigenvector centrality and low communality (the proportion of a variable's variance explained by the LVs), simplifying the final model [7].

Workflow Diagram: NDA Protocol

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Method | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Network-Based Dimensionality Analysis (NDA) | A nonparametric method for HDLSS data that uses community detection on variable correlation graphs to create latent variables [7]. |

| Stochastic Dimension Gradient Descent (SDGD) | A training methodology for Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) that enables solving high-dimensional PDEs by randomly sampling dimensional components of the gradient [8]. |

| Hyperbolic Geometric Models | A framework for determining the intrinsic, low-dimensional structure of complex networks without an initial spatial embedding [9]. |

| Penalized Regression (Ridge, Lasso) | Joint modeling techniques that apply shrinkage to regression coefficients to prevent overfitting and improve generalization in high-dimensional models [6]. |

| Bootstrap Rank Confidence Intervals | A resampling technique to assess the stability and confidence of feature importance rankings, providing an honest account of selection uncertainty [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What defines "high-dimensional data" in biology? High-dimensional data in biology refers to datasets where the number of features or variables (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) is staggeringly high—often vastly exceeding the number of observations. This "curse of dimensionality" makes calculations complex and requires specialized analytical approaches [11] [6].

2. Why is an integrated, multiomics approach better than studying a single molecule? Biology is complex, and molecules act in networks, not in isolation [6]. A multiomics approach integrates data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions and regulatory mechanisms within a biological system, moving beyond the limitations of a reductionist view [12] [13].

3. What is the major pitfall of "one-at-a-time" (OaaT) feature screening? OaaT analysis, which tests each variable individually for association with an outcome, is highly unreliable. It results in multiple comparison problems, high false negative rates, and massively overestimates the effect sizes of "winning" features due to double-dipping (using the same data for hypothesis formulation and testing) [6].

4. My multiomics model is overfitting. How can I improve its real-world performance? Overfitting is a central challenge. To address it:

- Increase Sample Size: Ensure an adequate sample size for the complexity of your task [6].

- Use Shrinkage Methods: Employ penalized maximum likelihood estimation methods like ridge regression or lasso, which discount model coefficients to prevent over-interpretation [6].

- Apply Data Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce a large number of variables to a few summary scores before modeling [6].

- Validate Properly: Always validate predictive models using rigorous methods like bootstrapping, ensuring the data mining process is repeated for each resample to get an unbiased performance estimate [6].

5. What are the best ways to visualize high-dimensional data? Since we cannot easily visualize beyond three dimensions, specific plot types are used to explore multi-dimensional relationships:

- Parallel Coordinates Plot: Shows how each variable contributes to the overall patterns and helps detect trends across many dimensions [11].

- Trellis Chart (Faceting): Displays a grid of smaller plots, allowing for comparison across subsets of the data [11].

- Mosaic Plot: Useful for visualizing data from two or more qualitative variables, where the area of the tiles is proportional to the number of observations [11].

Troubleshooting Experimental Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Biomarker Discovery in Transcriptomic Data

Symptoms: Different subsets of genes are identified as significant each time the analysis is run; findings fail to validate in an independent cohort.

Diagnosis: This indicates instability in feature selection, often caused by high correlation among genes (they "travel in packs") and the use of flawed statistical methods like one-at-a-time screening [6].

Solutions:

- Avoid One-at-a-Time Screening: Move away from individual association tests.

- Implement Shrinkage Methods: Use ridge regression, lasso, or elastic net to model all features simultaneously, which accounts for co-linearities and provides more stable, interpretable models [6].

- Apply Ranking with Bootstrap: For feature discovery, treat it as a ranking problem. Use bootstrap resampling to compute confidence intervals for the rank of each feature's importance. This honestly represents the uncertainty, showing which features are clear "winners," clear "losers," and which are in a middle ground where the data is inconclusive [6].

- Use Data Reduction: Perform PCA on the gene expression data and use the top principal components as variables in your model [6].

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Microarray Kit | Simultaneously measures the expression levels of tens of thousands of genes [11] [6]. |

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) Reagents | For cDNA library preparation and high-throughput sequencing to discover and quantify transcripts. |

| Normalization Controls | Spike-in RNAs or housekeeping genes used to correct for technical variation between samples. |

Problem: Integrating Heterogeneous Data from Multiple Omics Layers

Symptoms: Inability to combine genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets due to differences in scale, format, and biological context; the integrated model performs poorly.

Diagnosis: Data heterogeneity is a central challenge in multiomics research. Successful integration requires advanced computational methods to synthesize and interpret these complex datasets [13].

Solutions:

- Adopt a Systems Biology Framework: Frame your research to understand the inter-relationships of all elements in the system, rather than studying each omics layer independently [12].

- Leverage Advanced Computational Tools: Utilize deep learning, graph neural networks (GNNs), and generative adversarial networks (GANs) to facilitate the effective integration of disparate data types [13].

- Explore Large Language Models (LLMs): Investigate the potential of LLMs to enhance multiomics analysis through automated feature extraction and knowledge integration [13].

Table: Key Analytical Tools for Multiomics Integration

| Tool / Method | Function |

|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Models complex biological networks and interactions between different types of biomolecules [13]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Reduces the dimensionality of the data, simplifying the problem by creating summary scores [6]. |

| Random Forest | A machine learning method that fits multiple regression trees on random feature samples, often competitive in predictive ability though sometimes a "black box" [6]. |

Problem: Low Statistical Power in Metabolomic Profiling

Symptoms: Failure to identify metabolites that are truly associated with a phenotype or disease state.

Diagnosis: Inadequate sample size for the complexity of the analytic task. Mass spectrometry and other platforms generate vast amounts of variables, and a small sample size leads to a high false negative rate (low power) [6].

Solutions:

- Power Calculation: Before the experiment, perform a sample size calculation specific to high-dimensional data to ensure sufficient power.

- Focus on Confidence Intervals for Ranks: Instead of just p-values, report confidence intervals for the rank of metabolite importance. This highlights which metabolites have ranks supported by the data and which do not, properly communicating the uncertainty [6].

- Joint Modeling: Use multivariable models with shrinkage that consider all metabolites at once, which is more reliable than testing each one individually [6].

Table: Experimental Protocol for a Multiomics Workflow

| Step | Protocol Description | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Collection | Collect tissue or biofluid samples (e.g., blood, amniotic fluid) from case and control groups under standardized conditions. | To obtain biological material representing the health or disease state of interest [12]. |

| 2. Multiomics Profiling | Perform simultaneous high-throughput assays: RNA sequencing (transcriptomics), mass spectrometry (proteomics, metabolomics). | To generate comprehensive data on the different molecular layers of the biological system [12] [13]. |

| 3. Data Integration | Use systems biology tools and computational methods (e.g., deep learning) to integrate the genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets. | To uncover the complex interactions and regulatory mechanisms between different types of molecules [12] [13]. |

| 4. Model Building & Validation | Apply shrinkage methods (e.g., ridge regression) or data reduction (e.g., PCA) followed by rigorous validation using bootstrapping. | To build a predictive model that is stable, generalizable, and avoids overfitting [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Dimensional Biology

| Item | Explanation / Function |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Enables simultaneous examination of thousands of genes or transcripts (e.g., for genomics and transcriptomics) [12]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | A core technology for simultaneously identifying and quantifying numerous peptides/proteins (proteomics) or intermediate products of metabolism (metabolomics) [12] [6]. |

| Microarray Technology | Measures gene expression levels for tens of hundreds of samples, with each sample containing tens of thousands of genes [11]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | The analytical tools required to process, normalize, and extract meaningful information from raw high-dimensional data [12]. |

| Cell Culture Models | Provide a controlled environmental system for perturbing biological processes and observing corresponding multiomics changes. |

Experimental Workflows & Signaling Pathways

Multiomics Data Generation and Integration Workflow

Analytical Challenges and Solutions for High-Dimensional Data

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary goal of creating a good biological network figure? The primary goal is to quickly and clearly convey the intended message or "story" about your data, such as the functionality of a pathway or the structural topology of interactions. This requires determining the figure's purpose before creation to decide which data to include and how to visually encode it for clarity [14].

Q2: My network is very dense and the labels are unreadable. What are my options? For dense networks, consider using an adjacency matrix layout instead of a traditional node-link diagram. Matrices list nodes on both axes and represent edges with filled cells, which significantly reduces clutter and makes it easy to display readable node labels [14]. Alternatively, ensure you use a legible font size in your node-link diagram and provide a high-resolution version for zooming [14].

Q3: How many colors should I use to represent different groups in my network? For qualitative data (like different groups), the human brain struggles to differentiate between more than 12 colors and has difficulty recalling what each represents beyond 7 or 8. It is best to limit your palette to this number of hues [15].

Q4: My network looks cluttered and is hard to interpret. What can I do? Clutter often stems from an inappropriate layout. Consider switching from a force-directed layout to one that uses a meaningful similarity measure, such as connectivity strength or node attributes, to position nodes. This can make conceptual relationships and clusters more apparent [14]. Also, explore alternative representations like adjacency matrices for very dense networks [14].

Q5: How can I ensure my network visualization is accessible to colleagues with color vision deficiencies? Avoid conveying information by hue alone. Ensure your color palette has sufficient variation in luminance (perceived brightness) so that colors can be distinguished even if the hue is not perceived. Use online color blindness tools to test your visualizations, and always provide a legend or use other channels like shapes or patterns alongside color [15].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Poor color contrast makes text and symbols hard to see.

- Solution: Ensure all text and graphical objects meet minimum color contrast ratios.

- Small text should have a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 against its background [16] [17] [18].

- Large text (≥18pt or ≥14pt bold) should have a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 [16] [18].

- User interface components and graphical objects (like icons or graph elements) should have a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 [18].

- How to Check: Use color contrast analysis tools like the WebAIM Color Contrast Checker or the accessibility inspector in Firefox Developer Tools [17] [18].

Problem: Colors in the network visualization are confusing or misleading.

- Solution: Follow a structured process for choosing colors:

- Decide what the colors represent (e.g., a node attribute, a data value) [15].

- Understand your data scale to choose the right palette type: sequential (low to high), divergent (two extremes with a midpoint), or qualitative (distinct categories) [15].

- Choose colors based on the scale:

- Use pre-designed, accessible palettes from resources like ColorBrewer to ensure your colors work well together and are colorblind-friendly [15] [19].

Problem: Node labels are too small, overlap, or are unreadable.

- Solution:

- Use a font size that is the same as or larger than the figure caption's font size [14].

- Choose a layout algorithm that provides enough space for labels, or manually adjust the layout to reduce edge crossings and node overlap [14].

- If increasing the label size is impossible, provide a high-resolution version of the figure that users can zoom into [14].

Problem: The network layout suggests relationships that aren't real (e.g., proximity implying similarity).

- Solution: Be aware that viewers will naturally interpret spatial proximity, centrality, and direction as meaningful. Select a layout algorithm that aligns with your network's story. For example, use a force-directed layout that uses a real similarity measure (like connectivity) to position nodes, rather than a purely aesthetic algorithm that might create accidental and misleading groupings [14].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Creating a Static Biological Network Figure for Publication

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a publication-ready biological network visualization, from data preparation to final design adjustments.

1. Determine Figure Purpose and Message [14]

- Write a draft of the figure caption. This clarifies the specific story the figure must tell.

- Identify whether the message relates to the entire network, a subset of nodes, network topology, functionality, or another aspect.

2. Choose an Appropriate Layout [14]

- Node-Link Diagram: Best for showing relationships and for smaller, less dense networks. Use force-directed or multidimensional scaling layouts to emphasize clusters.

- Adjacency Matrix: Superior for dense networks, for displaying edge attributes, and for avoiding label clutter.

- Fixed/Implicit Layouts: Use for spatial data (e.g., on a map) or for tree structures (e.g., icicle plots).

3. Map Data to Visual Channels [15] [14]

- Color: Use to represent node or edge attributes (see color selection guide above).

- Size: Map node size to a quantitative attribute like degree centrality or mutation count.

- Shape: Use different node shapes to represent categorical attributes.

4. Implement Readable Labels and Annotations [14]

- Ensure all labels are legible at publication size.

- Use annotations (e.g., arrows, text boxes) to highlight key parts of the network relevant to your message.

5. Validate and Refine

- Check color contrast for all text and graphical elements [16] [18].

- Test the visualization for clarity with colleagues unfamiliar with the project.

Workflow Diagram: Network Visualization Creation

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: WCAG 2.1 Minimum Color Contrast Requirements for Visualizations

This table summarizes the minimum contrast ratios required to make visual content accessible to users with low vision or color deficiencies [16] [18].

| Content Type | Definition | Minimum Ratio (Level AA) | Enhanced Ratio (Level AAA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Text | Standard-sized text. | 4.5:1 | 7:1 |

| Large Text | Text that is at least 18pt or 14pt bold. | 3:1 | 4.5:1 |

| UI Components & Graphical Objects | Icons, graph elements, and form boundaries. | 3:1 | Not defined |

Table 2: Color Palette Selection Guide for Data Visualization

This table guides the selection of color palettes based on the type of data being represented [15].

| Data Scale | Description | Recommended Palette | Number of Hues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential | Data values range from low to high. | One hue, varying luminance/saturation. | 1 |

| Divergent | Data has two extremes with a critical midpoint. | Two hues, decreasing in saturation towards a neutral midpoint. | 2 |

| Qualitative | Data represents distinct categories with no intrinsic order. | Multiple distinct hues. | Number of categories (≤ 12) |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Network Visualization |

|---|---|

| Cytoscape | An open-source software platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating them with any type of attribute data. It provides a rich selection of layout algorithms and visual style options [14]. |

| ColorBrewer | An online tool designed to help select color palettes for maps and other visualizations, with a focus on sequential, divergent, and qualitative schemes that are colorblind-safe [15]. |

| yEd Graph Editor | A powerful, free diagramming application that can be used to create network layouts manually or automatically using a wide range of built-in algorithms [14]. |

| Adjacency Matrix Layout | An alternative to node-link diagrams that is superior for visualizing dense networks and edge attributes, reducing visual clutter [14]. |

| Accessible Color Palettes | Pre-defined sets of colors, such as the 16 palettes in PARTNER CPRM, that are designed for readability, brand alignment, and colorblind-friendliness [19]. |

Toolkit Workflow Diagram

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Model Overfitting

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise and specific details of the training dataset to the extent that it negatively impacts its performance on new, unseen data. You can identify it by a significant gap between high performance on training data and low performance on validation or test data [20].

Problem: My model has high accuracy on training data but performs poorly on validation data.

- Solution: Apply one or more of the following techniques:

- Implement Regularization: Add a penalty term to the model's loss function to discourage complexity. L1 regularization can lead to sparse models, while L2 regularization helps distribute weight values more evenly [20].

- Use Dropout: Randomly ignore a fraction of neurons during each training epoch. This prevents the network from becoming overly reliant on any specific set of neurons and improves generalization [20].

- Employ Data Augmentation: Increase the size and variability of your training dataset by creating modified versions of the existing data. For image data, this can include rotations, shifts, and flips [20].

- Apply Early Stopping: Monitor the model's performance on a validation set during training and halt the process once the validation loss stops improving and begins to increase [20].

- Solution: Apply one or more of the following techniques:

Problem: My model is overly complex and has memorized the training data.

- Solution:

- Simplify the Model: Use a simpler model architecture, especially when you have limited data [21].

- Apply Dimensionality Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of features, thereby decreasing model complexity [21].

- Use Ensemble Methods: Combine predictions from multiple models (e.g., via bagging or boosting) to improve generalization and robustness [21].

- Solution:

Guide 2: Addressing Computational Intractability in High-Dimensional Networks

Computational intractability arises when the resources required to analyze high-dimensional data become prohibitively large. In network analysis, this often occurs when modeling complex relationships.

Problem: My network model is too computationally expensive to run efficiently.

- Solution:

- Explore Alternative Representations: Traditional latent factor models that reduce social inferences to a few core dimensions (e.g., warmth, competence) may not capture the full complexity. Consider high-dimensional network models that represent the unique correlations between variables, which can better represent complex data with less common variance [22].

- Leverage Advanced Computing Resources: Utilize GPUs or cloud computing for accelerated model training and inference [23].

- Solution:

Problem: My analysis is hindered by the "curse of dimensionality."

- Solution:

- Feature Selection and Engineering: Meticulously select and create meaningful features. Discarding unimportant variables can significantly reduce complexity [21].

- Solution:

Guide 3: Improving Model Generalizability

A model generalizes well when it performs accurately on new, unseen data. Failure to generalize often stems from overfitting or an inability to capture the true underlying patterns of the data.

- Problem: My model fails to make reliable predictions on new data.

- Solution:

- Balance Bias and Variance: A model with high bias (oversimplified) is prone to underfitting, while a model with high variance (overly complex) is prone to overfitting. The goal is to find a complexity level that minimizes total error [21].

- Use a Validation Set: Always validate your model’s performance on a separate, held-out validation set to monitor its ability to generalize [20] [21].

- Design Better Experiments: Ensure your experimental protocol is rich enough to engage the targeted processes and that signatures of these processes are evident in the data. Computational modeling is fundamentally limited by the quality and design of the experiment [24].

- Solution:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the clear indicators of an overfit model? The primary indicator is a significant performance gap between the training data and the validation or test data. You may observe high accuracy or a low loss on the training set, but concurrently see low accuracy or a high loss on the validation set [20] [21].

Q2: How does regularization help prevent overfitting? Regularization adds a penalty to the model's loss function based on the magnitude of the model's coefficients. This discourages the model from becoming overly complex and fitting to the noise in the training data, thereby encouraging simpler, more generalizable patterns [20].

Q3: What is the practical difference between L1 and L2 regularization? L1 regularization (Lasso) adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the coefficients, which can drive some weights to zero, effectively performing feature selection. L2 regularization (Ridge) adds a penalty equal to the square of the coefficients, which leads to small, distributed weights but rarely forces any to be exactly zero [20].

Q4: When should I consider using a high-dimensional network model over a traditional latent factor model? Consider a high-dimensional network model when you suspect that the unique correlations between variables are important and that the common variation captured by a few latent factors is insufficient. Network models are particularly useful for capturing the complex, non-uniform relationships found in naturalistic data [22].

Q5: Why is a validation set crucial, and how is it different from a test set? A validation set is used during the model development and tuning process to provide an unbiased evaluation of a model fit. The test set is held back until the very end to provide a final, unbiased evaluation of the model's generalization ability after all adjustments and training are complete [21].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing Early Stopping

- Objective: Halt training before the model starts to overfit.

- Methodology:

- Split your data into three sets: training, validation, and test.

- Train the model on the training set.

- After each epoch (or a set number of iterations), calculate the loss on the validation set.

- Continue training as long as the validation loss decreases.

- Stop training when the validation loss fails to improve for a pre-defined number of epochs (patience).

- Use the weights from the epoch with the best validation loss for your final model [20].

Protocol 2: Comparing Model Representations for Social Inference Data

- Objective: Evaluate whether a high-dimensional network model provides a better fit for social inference data than a low-dimensional latent factor model.

- Methodology (based on [22]):

- Stimuli & Data Collection: Collect diverse, naturalistic data (e.g., videos). Have participants freely describe the stimuli using their own words.

- Data Processing: Code the responses into a structured dataset of inferences.

- Model Fitting:

- Latent Factor Model: Use cross-validation to identify the optimal number of latent dimensions that explain the variance in the data.

- Network Model: Fit a sparse network model that represents the unique pairwise correlations between inferences.

- Model Comparison: Compare the variance explained by the latent factor model against the fit of the network model to determine which representation better captures the structure of the data [22].

| Technique | Primary Mechanism | Key Parameters | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1/L2 Regularization [20] | Adds penalty to loss function | Regularization strength (λ) | Reduced model complexity, lower variance |

| Dropout [20] | Randomly drops neurons during training | Dropout probability (p) | Prevents co-adaptation of neurons, improves robustness |

| Early Stopping [20] | Halts training when validation performance degrades | Patience (epochs to wait) | Prevents the model from learning noise from training data |

| Data Augmentation [20] | Artificially expands training dataset | Transformation types (rotate, shift, etc.) | Teaches model invariances, improves generalization |

| Ensemble Methods [21] | Combines predictions from multiple models | Number & type of base models | Reduces variance, improves predictive stability |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and conceptual frameworks used in the experiments and techniques cited.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Regularization (L1 & L2) | A mathematical technique used to prevent overfitting by penalizing overly complex models in the loss function [20]. |

| Dropout | A regularization technique for neural networks that prevents overfitting by randomly ignoring a subset of neurons during each training step [20]. |

| Validation Set | A subset of data used to provide an unbiased evaluation of a model fit during training and to tune hyperparameters like the early stopping point [20] [21]. |

| High-Dimensional Network Model | A representation that captures the unique pairwise relationships between variables, offering an alternative to latent factor models for complex data [22]. |

| Cross-Validation | A resampling procedure used to evaluate models on a limited data sample, crucial for reliably estimating model performance and selecting the number of latent factors [22]. |

Workflow and Model Diagrams

Early Stopping Implementation Workflow

Bias-Variance Tradeoff Relationship

Model Representation Comparison

Dimensionality Reduction Arsenal: Feature Selection, Projection, and Network-Based Approaches for Drug Discovery

In network analysis research, high-dimensional data presents a significant challenge, where datasets can contain thousands of features or nodes. This dimensionality curse complicates model training, increases computational costs, and risks overfitting, ultimately obscuring meaningful biological or social patterns [25]. Within the context of a broader thesis on addressing high dimensionality, two primary dimensionality reduction techniques emerge as critical: feature selection, which identifies a subset of the most relevant existing features, and feature extraction, which creates new, more informative features through transformation [26]. The strategic choice between these methods directly impacts the interpretability, efficiency, and success of network-based models in scientific research.

Core Concepts and Key Differences

What is Feature Selection?

Feature selection simplifies your dataset by choosing the most relevant features from the original set while discarding irrelevant or redundant ones. This process preserves the original meaning of the features, which is crucial for interpretability in scientific domains [26] [25]. For instance, in a network analysis of influenza susceptibility, researchers might select specific health checkup items like sleep efficiency and glycoalbumin levels from thousands of parameters, ensuring the model's findings are directly traceable to measurable biological factors [27].

What is Feature Extraction?

Feature extraction transforms the original features into a new, reduced set of features that captures the underlying patterns in the data. This is particularly valuable when raw data is high-dimensional or complex, such as with image, text, or sensor data [26] [28]. For example, in image-based network analyses, techniques like Local Binary Patterns (LBP) or Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) can transform raw pixels into meaningful representations of texture and spatial patterns [28].

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between these two approaches.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Feature Selection and Feature Extraction

| Aspect | Feature Selection | Feature Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Selects a subset of relevant original features [26]. | Transforms original features into a new, more informative set [26]. |

| Output Features | A subset of the original features [25]. | Newly constructed features [25]. |

| Interpretability | High; retains original feature meaning [26]. | Lower; new features may not have direct physical interpretations [26]. |

| Primary Advantage | Enhances model interpretability and reduces overfitting by removing noise [26]. | Can capture complex, nonlinear relationships and underlying structure not visible in raw features [26] [25]. |

| Common Techniques | Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded methods [25]. | PCA, LDA, Autoencoders [26]. |

Decision Framework and Strategic Guidance

When to Use Feature Selection

Choosing feature selection is the appropriate strategy when your research goals prioritize interpretability and direct causal inference. This approach is ideal when the original features have clear, meaningful identities that must be retained for analysis, such as specific biological markers, gene expressions, or patient demographics [26] [25]. It is also computationally efficient and suitable when the dataset is not extremely high-dimensional and your aim is to remove features that are known or suspected to be redundant or irrelevant [26].

When to Use Feature Extraction

Opt for feature extraction when dealing with very high-dimensional data where the sheer number of features is problematic, or when the raw features are correlated, noisy, and the underlying patterns are complex [26]. This strategy is powerful for uncovering latent structures not directly observable in the raw data. It is essential in fields like image analysis (e.g., extracting texture features from medical images) [28] and natural language processing, and is often a prerequisite for deep learning models that require dense, informative input representations [26] [25].

Hybrid and Advanced Approaches

Modern research increasingly leverages hybrid frameworks and advanced deep learning architectures that integrate both principles. For instance, Variational Explainable Neural Networks have been developed to perform both reliable feature selection and extraction, offering a particular competitive advantage in high-dimensional data applications [29]. Furthermore, network analysis itself can be a form of feature extraction, transforming raw data into relational structures, as seen in Bayesian networks used to model causal pathways in health data [27] and high-dimensional network models for social inferences [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can I use both feature selection and feature extraction in the same pipeline? Yes, a hybrid approach is often highly effective. You might first use feature extraction (e.g., PCA) on a very high-dimensional dataset like image pixels to create a manageable set of new features. Then, you could apply feature selection on these new components to select the most critical ones for the final model, streamlining the pipeline further [29].

2. How does the choice of technique affect the interpretability of my network model? Feature selection generally leads to more interpretable models because it retains the original, meaningful features. For example, in a clinical study, knowing that "sleep efficiency" is a key predictor is directly actionable. Feature extraction, while powerful for performance, can create features that are complex combinations of the original inputs (Principal Components in PCA), making them difficult to interpret in the context of the original domain [26].

3. What is a common pitfall when applying feature extraction to biological network data? A major pitfall is assuming the new features will be automatically meaningful for your specific biological question. Feature extraction techniques like PCA are unsupervised and maximize variance, but this variance may not be relevant to your target (e.g., disease onset). Always validate that the extracted features have predictive power and, if possible, biological plausibility in the context of your network [28].

4. My model is overfitting the training data in a high-dimensional network analysis. Which technique should I try first? Feature selection is often the first line of defense against overfitting caused by irrelevant features. By removing non-informative variables, you reduce the model's capacity to learn noise from the training data. Start with embedded methods (like Lasso regularization) or filter methods, which are computationally efficient and can quickly identify a robust subset of features [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Loss of Critical Information After Dimensionality Reduction

Symptoms: Model performance (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) drops significantly post-reduction; model fails to capture known relationships.

Solutions:

- For Feature Selection: Re-evaluate your selection criteria. If using a filter method based on correlation, consider a wrapper method like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) that uses model performance to guide the selection, which can be more sensitive to important features [25].

- For Feature Extraction: Increase the number of components retained. For instance, in PCA, instead of using 2 components, check the cumulative explained variance plot and choose a number that explains a higher percentage (e.g., 95%) of the total variance [30].

- General Check: Ensure the reduction technique is appropriate for your data. If features are non-linearly related, a linear technique like PCA might discard important information. Consider non-linear extraction methods like Kernel PCA or Autoencoders [26].

Problem: Model Results Are Not Interpretable to Domain Experts

Symptoms: Difficulty explaining the model's predictions to colleagues; inability to derive biologically or clinically meaningful insights.

Solutions:

- Primary Solution: Switch from feature extraction to feature selection. Using a subset of the original features allows you to present findings in the domain's native language (e.g., "The model identified age and cytokine level IL-6 as the top predictors") [26] [27].

- If Extraction is Necessary: Employ techniques that allow for some interpretation. For example, after using LDA, you can examine the loadings of the original features on the discriminants to understand which original variables contributed most to the new features. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP can also be applied to explain model outputs, even with extracted features [29].

Problem: High Computational Cost During Model Training

Symptoms: Training times are prohibitively long; experiments are difficult to iterate on.

Solutions:

- Immediate Action: Apply a fast filter-based feature selection method (e.g., based on mutual information or correlation) as a preliminary step to drastically reduce the feature space before applying more complex models or wrapper methods [25].

- Optimize Extraction: For feature extraction, consider using incremental PCA (iPCA) for large datasets, which processes data in mini-batches. Also, ensure you are using optimized libraries (like Scikit-learn) that are built for performance [26].

- Leverage Embedded Methods: Use models with built-in feature selection, such as Lasso (L1 regularization) or Random Forests, which provide feature importance scores as part of the training process. This is often more efficient than running a separate wrapper method [25].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: A Standard Workflow for Filter-Based Feature Selection

This protocol is ideal for initial data exploration and fast dimensionality reduction.

- Preprocessing: Handle missing values and normalize or standardize the data.

- Feature Scoring: Calculate a statistical measure (e.g., correlation coefficient, mutual information, chi-squared) between each feature and the target variable.

- Ranking: Rank all features based on their calculated scores in descending order.

- Subset Selection: Select the top k features from the ranked list, where k can be determined by a pre-defined threshold, by looking for an "elbow" in the score plot, or via cross-validation.

- Model Training & Validation: Train your model using only the selected subset of features and validate its performance on a held-out test set.

Protocol 2: Workflow for Feature Extraction using Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Use this protocol to deal with multicollinearity or to compress data for visualization.

- Standardization: Standardize the data to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This is critical for PCA, as it is sensitive to the scales of the features.

- Covariance Matrix Computation: Compute the covariance matrix of the standardized data to understand how the features vary from the mean with respect to each other.

- Eigendecomposition: Calculate the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix. The eigenvectors represent the principal components (directions of maximum variance), and the eigenvalues represent the magnitude of the variance carried by each component.

- Component Selection: Sort the eigenvectors by their eigenvalues in descending order. Select the first n eigenvectors that capture a sufficient amount of the total variance (e.g., 95%). A scree plot can be used to visualize the explained variance per component and aid in selection.

- Projection: Transform the original dataset by projecting it onto the selected principal components to create a new, lower-dimensional dataset.

Visualizing the Strategic Decision Process

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for choosing between feature selection and feature extraction, incorporating key questions and outcomes.

Decision Workflow for Dimensionality Reduction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key computational tools and techniques that function as the essential "research reagents" for conducting dimensionality reduction in network analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dimensionality Reduction

| Tool / Technique | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to Network Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods [25] | Feature Selection | Ranks features using statistical measures (e.g., correlation, MI). | Fast preprocessing to reduce node/feature count before constructing a network. |

| Wrapper Methods [25] | Feature Selection | Uses model performance to find the optimal feature subset. | Selects features that maximize the predictive power of a network-based model. |

| Lasso (L1) Regression [25] | Feature Selection | Embedded method that performs feature selection during model training. | Identifies the most relevant features in high-dimensional regression problems, enhancing interpretability. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [26] | Feature Extraction | Transforms correlated features into uncorrelated principal components. | Compresses network node data for visualization or as input for downstream analysis. |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [26] | Feature Extraction | Finds feature combinations that best separate classes. | Enhances class separation in network node data for classification tasks. |

| Autoencoders [26] | Feature Extraction | Neural networks that learn compressed data representations. | Learns non-linear, low-dimensional embeddings of complex network structures or node attributes. |

| Bayesian Networks [27] | Network Analysis | Probabilistic model representing variables and their dependencies. | Used for causal discovery and understanding complex relationships between features, a form of structural analysis. |

In the context of network analysis research, managing high-dimensional data is a fundamental challenge. Techniques for dimensionality reduction are essential for extracting meaningful insights from complex datasets. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) are two core linear techniques widely employed for this purpose. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in effectively applying PCA and LDA to their experimental workflows.

Core Concepts at a Glance

The following table summarizes the primary objectives, key characteristics, and common applications of PCA and LDA to help you select the appropriate technique.

| Feature | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Unsupervised dimensionality reduction; maximizes variance of the entire dataset [31]. | Supervised dimensionality reduction; maximizes separation between predefined classes [31] [32]. |

| Key Objective | Find orthogonal directions (principal components) of maximum variance [31]. | Find a feature subspace that optimizes class separability [32] [33]. |

| Label Usage | Does not use class labels [31]. | Requires class labels for training [31] [32]. |

| Output Dimensionality | Up to number of features (or samples-1). | Up to number of classes minus one (C-1) [33]. |

| Typical Application | Exploratory data analysis, data compression, noise reduction. | Feature extraction for classification, enhancing classifier performance. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

General Techniques

Q1: How do I choose between PCA and LDA for my high-dimensional dataset? The choice hinges on the goal of your analysis and the availability of labeled data. Use PCA for unsupervised exploration, visualization, or compression of your data without using class labels. It is ideal for understanding the overall structure and variance in your data. Use LDA when you have a labeled dataset and the explicit goal is to improve a classification model or find features that best separate known classes. For example, in a study on teat number in pigs, PCA was effective for correcting for population structure in genetic data, while LDA would be more suited for building a classifier to predict a specific trait [34].

Q2: What are the critical assumptions for LDA and how do I check them? LDA performance relies on several key assumptions [31] [33]:

- Multivariate Normality: Independent variables should be normally distributed for each class. You can check this using Mardia's test [33].

- Homoscedasticity (Homogeneity of Variances): The covariance matrices across all classes should be approximately equal. This can be tested using Box's M test [33].

If these assumptions are violated, consider using related methods like Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA) or Regularized Discriminant Analysis (RDA), which are more flexible with covariance structures [32].

Data Preprocessing

Q3: What is the best way to handle missing values before performing PCA? Several strategies exist for handling missing values, each with trade-offs [35]:

- Listwise Deletion: Remove any samples (rows) with missing values. This is simple but can lead to significant data loss and biased results if the data is not missing completely at random.

- Mean/Median Imputation: Replace missing values with the mean or median of the available values for that variable. This is a basic approach that works well for small amounts of missing data [36].

- Advanced Imputation: For better accuracy, use sophisticated algorithms designed for PCA, such as the Data Interpolating Empirical Orthogonal Functions (DINEOF) or the methods provided by the

pcaMethodsR package (e.g., NIPALS, iterative PCA/EM-PCA) [35]. These methods iteratively estimate the missing values based on the data structure captured by the principal components.

Q4: Should I center and scale my data before applying PCA or LDA?

Yes, centering (subtracting the mean) is essential for PCA because the technique is sensitive to the origin of the data. Scaling (dividing by the standard deviation to achieve unit variance) is highly recommended, especially if the features are measured on different scales. Without scaling, variables with larger ranges would dominate the principal components. Most implementations, like prcomp in R, allow you to set center = TRUE and scale = TRUE [37].

Implementation and Results

Q5: I am using R, and prcomp() is dropping rows with NA values. How can I avoid this?

The na.action parameter in prcomp() may not work as expected. Instead of relying on it, preprocess your data to handle missing values before passing it to prcomp(). You can use the na.omit() function to remove rows with NAs, or use one of the imputation methods mentioned in Q3 to fill in the missing values first [35].

Q6: Why does my LDA model perform poorly even though the derived trait has high heritability? High heritability of an LDA-derived trait does not guarantee strong performance in downstream analyses like linkage mapping. A study on gene expression traits found that while the first linear discriminant (LD1) consistently had the highest heritability, it often performed the worst in recovering linkage signals (LOD scores) compared to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or simple averaging. This suggests that maximizing heritability alone may not be the optimal strategy for all analytical goals [37].

Q7: In a three-class problem, how do I determine classification thresholds with two discriminant functions (LD1 and LD2)? With two or more discriminant functions, the classification is typically not based on a simple threshold line. Instead, the classification rule is based on which class mean (centroid) a data point is closest to in the multi-dimensional discriminant space. A new sample is assigned to the class whose centroid is nearest, often using measures like Mahalanobis distance. Visualizing the data on an LD1 vs. LD2 scatter plot will show the class centroids and the natural decision boundaries that arise between them [38].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Functional Group-Based Linkage Analysis Using Composite Traits

This protocol outlines a method for combining multiple related traits (e.g., gene expression levels) in linkage analysis to gain more power by borrowing information across functionally related transcripts [37].

1. Selection of Functional Groups:

- Annotate all transcripts (e.g., mRNA) according to a biological ontology like Gene Ontology (GO).

- Group transcripts based on shared biological processes.

- Restrict analysis to groups of a specific size (e.g., 10-20 transcripts) to balance functional specificity and statistical power.

- Calculate the average heritability of traits within each group and select the top groups with the highest average heritability for subsequent analysis.

2. Derivation of Composite Traits: Standardize all individual traits to have a sample mean of 0 and a sample variance of 1. Then, derive a univariate composite trait using one of the following methods:

- Sample Average: Simply average the standardized values.

- Principal Components Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on the group of traits and use the first principal component (PC1), which explains the largest proportion of sample variance [37].

- Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): Use LDA with family ID as the class label to find a linear combination that maximizes the ratio of inter-family to intra-family variance.

3. Linkage Analysis:

- Calculate multipoint variance-component LOD scores for each individual transcript and for the new composite traits using linkage analysis software like Merlin [37].

4. Combining Linkage Results:

- To identify clustering of linkage peaks from multiple traits, use a sliding window approach (e.g., 10 cM).

- Define a "cluster" as a genomic window where more than one gene has a LOD score peak above a set threshold.

- Employ a heuristic method to calculate a p-value to assess the statistical significance of the observed clustering.

Flowchart of Functional Group Linkage Analysis

Protocol 2: Integrating Random Projections with PCA for High-Dimensional Classification

This protocol is designed for the "small n, large p" problem, where the number of features far exceeds the number of samples. It combines Random Projections (RP) and PCA for data augmentation and dimensionality reduction to boost neural network classification performance [39].

1. Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize the high-dimensional dataset (e.g., scRNA-seq data) so that each feature has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

2. Generation of Multiple Random Projections:

- Generate multiple (e.g., k) independent random projection matrices based on the Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma.

- Project the original high-dimensional dataset into k different lower-dimensional subspaces using these matrices. This step simultaneously reduces dimensionality and augments the number of training samples by k-fold.

3. Refinement with PCA:

- Apply PCA to each of the k randomly projected datasets.

- Retain a fixed number of top principal components from each to further reduce dimensionality and capture the most important covariance structure.

4. Model Training and Inference:

- Train a separate neural network classifier on each of the k augmented and reduced training sets.

- During inference, for a new test sample, generate k corresponding representations using the same RP and PCA transformation steps.

- Obtain predictions from all k neural networks and use a majority voting strategy to determine the final class label for the test sample.

Flowchart of RP-PCA-NN Classification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The table below lists key software and methodological "reagents" essential for implementing PCA and LDA in a research environment.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

R prcomp |

Software Function | Performs PCA with options for centering and scaling. | General-purpose PCA for data exploration and dimensionality reduction [37]. |

R lda (MASS) |

Software Function | Fits an LDA model for classification and dimensionality reduction. | Supervised feature extraction and classification based on class labels [33]. |

| SOLAR | Software Suite | Estimates heritability of quantitative traits. | Used in genetic studies to select traits/groups with high heritability for linkage analysis [37]. |

| Merlin | Software Suite | Performs linkage analysis to calculate LOD scores. | Mapping disease or trait loci in family-based genetic studies [37]. |

| NIPALS Algorithm | Computational Method | Performs PCA on datasets with missing values. | Handling missing data in PCA without requiring listwise deletion [35]. |

| Iterative PCA (EM-PCA) | Computational Method | A multi-step method for imputing missing values and performing PCA. | Robust handling of missing values; often outperforms simple imputation methods [35]. |

| Random Projections (RP) | Computational Method | A computationally efficient dimensionality reduction technique. | Rapidly reducing data dimensionality while preserving structure, often used in ensembles [39]. |

The table below summarizes quantitative results from a study comparing composite trait methods in linkage analysis, providing a benchmark for expected outcomes [37].

| Functional Group | No. of Transcripts | LOD Threshold | Total Peaks (Ind. Traits) | 2-Peak Clusters (p-value) | 3-Peak Clusters (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 2 | 11 | 2 | 18 | 3 (0.002) | 1 (3x10⁻⁵) |

| Group 2 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 1 (10⁻⁴) | 0 (N/A) |

| Group 5 | 21 | 2 | 49 | 5 (0.01) | 2 (7x10⁻⁴) |

| Group 5 | 21 | 3 | 14 | 1 (10⁻³) | 0 (N/A) |

Troubleshooting Guides

Interpreting Results Accurately

Problem: Distances between clusters in a t-SNE plot are being misinterpreted as meaningful.

Solution: t-SNE primarily preserves local neighborhood structure rather than global distances. Do not interpret large distances between clusters as indicating strong dissimilarity in the original high-dimensional space [40] [41]. To verify relationships, correlate your findings with:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) projections, which better preserve global variance [41].

- Domain knowledge about your data categories [41].

- Multiple DR techniques such as UMAP or PaCMAP to see if cluster relationships are consistent [42].

Problem: A t-SNE visualization shows apparent clusters, but it's unclear if they represent true biological groups or are artifacts of the algorithm.

Solution: t-SNE can create the illusion of clusters even in data without distinct groupings [41]. To validate:

- Run dedicated clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means, HDBSCAN) directly on the high-dimensional data or latent representations [42] [41].

- Check if the cluster labels match known metadata (e.g., cell type, drug MOA) using external validation metrics like Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) or Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [42].

- Use color-coding in your DR plot to highlight known categories and see if they align with the visual clusters [41].

Optimizing Algorithm Parameters

Problem: A t-SNE projection looks unstable or fails to reveal expected structure.

Solution: t-SNE is sensitive to its perplexity hyperparameter and random initialization [41].

- Perplexity: Effectively balances attention between local and global data structure. Treat the default value of 30 as a starting point [41].

- Stability: Always run t-SNE multiple times with different random seeds (

random_state). If the same patterns persist, they are more likely to be real [41].

Problem: A UMAP projection looks overly compressed or too spread out, losing meaningful structure.

Solution: Tune two key parameters [43]:

n_neighbors: Controls the scale of the local structure UMAP considers.- Lower values (e.g., 2-15) focus on fine-grained, local patterns.

- Higher values (e.g., 50-200) emphasize the broader, global structure.

min_dist: Controls how tightly points are packed together in the embedding.- Lower values (~0.0) allow points to cluster tightly, useful for clustering tasks.

- Higher values (~0.1-0.5) create a more spread-out layout, making it easier to see topological connections.

Handling Performance and Scalability

Problem: The t-SNE algorithm is too slow or runs out of memory with a large dataset.

Solution: Standard t-SNE has high computational complexity, making it unsuitable for very large datasets [43] [41].

- Use UMAP as a faster alternative with linear time complexity, ideal for datasets with over 10,000 samples [43] [41].

- If you must use t-SNE, employ its optimized variants:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

When should I use t-SNE over UMAP, and vice versa?

The choice depends on your data size and analytical goal. The following table summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | t-SNE | UMAP |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Excellent for visualizing local structure and tight clusters [43] | Better at preserving global structure and relationships between clusters [43] |

| Typical Use Case | Identifying fine-grained subpopulations (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq) [43] [41] | Understanding the overall layout and connectivity of data [43] |

| Speed | Slower, struggles with large datasets [43] [41] | Significantly faster, scalable to millions of points [43] [41] |

| Stability | Results can vary with different random initializations [41] | Generally more stable and deterministic across runs [41] |

| Parameter Sensitivity | Highly sensitive to perplexity [41] | Less sensitive; parameters are often more intuitive [43] |

Can I use the output of t-SNE or UMAP for quantitative analysis or clustering?

No. The 2D/3D embeddings from t-SNE and UMAP should not be used directly for downstream clustering or quantitative analysis [41]. These visualizations are for exploration and hypothesis generation only. Distances in the low-dimensional space are distorted and do not faithfully represent original high-dimensional distances [40] [41]. For clustering, apply algorithms directly to the original high-dimensional data or a more faithful latent representation (e.g., from PCA or an autoencoder) [42] [41].

How do I track the effectiveness of an Autoencoder?

Evaluating an autoencoder involves assessing both the quality of its reconstructions and the structure of its latent space.