Navigating Missing Data in Omics: A Comprehensive Guide to Imputation Methods for Robust Biomedical Research

Missing data is a pervasive challenge in omics studies, threatening the validity of downstream analyses and biological discoveries.

Navigating Missing Data in Omics: A Comprehensive Guide to Imputation Methods for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

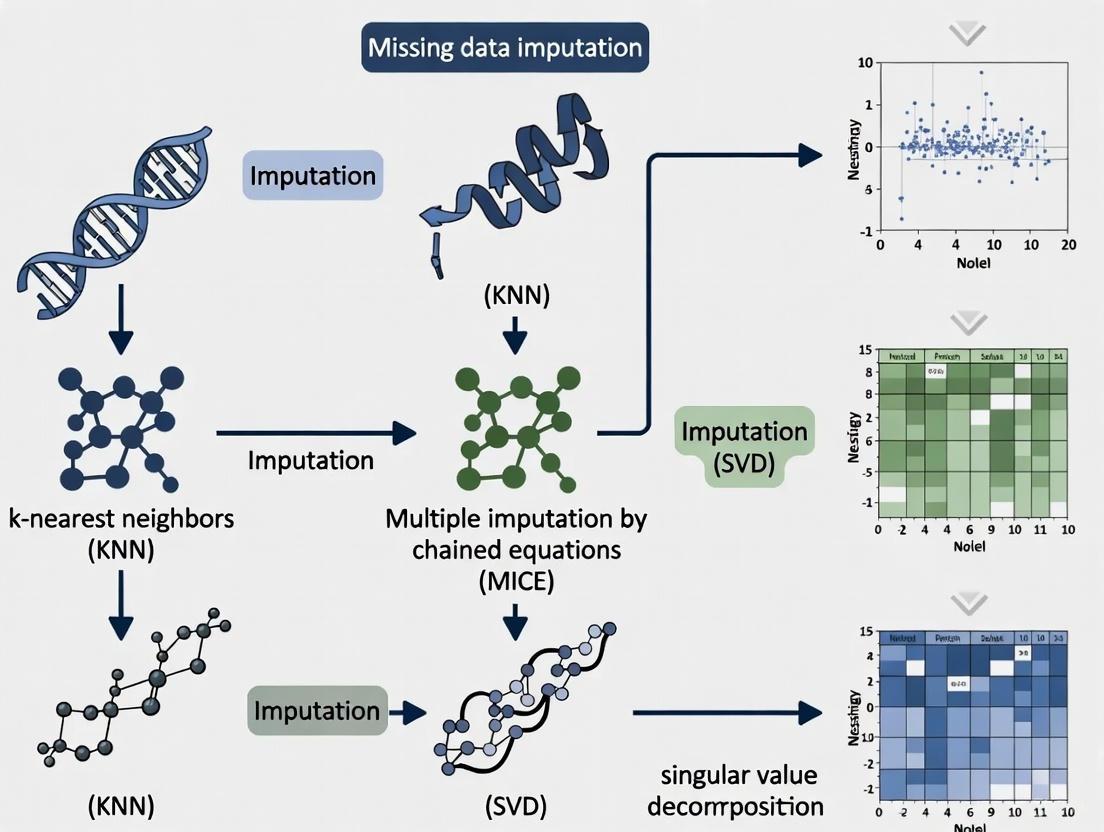

Missing data is a pervasive challenge in omics studies, threatening the validity of downstream analyses and biological discoveries. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on handling missing values in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics datasets. We explore the foundational concepts of missing data mechanisms—MCAR, MAR, and MNAR—and their implications for multi-omics integration. The guide systematically reviews traditional and AI-driven imputation methods, from k-nearest neighbors and MissForest to deep learning approaches like variational autoencoders. We offer practical strategies for method selection, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and validating imputation performance using downstream-centric criteria. Finally, we discuss emerging trends, including data multiple imputation (DMI) and privacy-preserving federated learning, providing a roadmap for implementing robust, reproducible missing data solutions in precision medicine and oncology research.

The Missing Data Challenge: Understanding the Why and How in Omics Research

The Prevalence and Impact of Missing Values in Multi-Omics Studies

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Nature of Missing Data in Your Multi-Omics Dataset

A critical first step in handling missing data is diagnosing its nature and extent. Incorrect diagnosis can lead to the application of unsuitable imputation methods, biasing downstream analysis and compromising the validity of your biological conclusions.

Prerequisites: Your complete, untrimmed multi-omics dataset (e.g., as a data matrix or a SummarizedExperiment object in R).

Required Tools: Standard statistical software (e.g., R, Python) and functions for data summary.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quantify Missingness Per Sample and Per Feature | Outcome: A table or plot showing the percentage of missing values for each sample (row) and each molecular feature (column, e.g., a gene or protein).Interpretation: Identifies if missingness is concentrated in a few problematic samples/features, which might be candidates for removal, or if it is widespread. |

| 2 | Identify the Missingness Pattern | Outcome: Determination of whether data is missing sporadically (random cells in the matrix) or in a block-wise pattern (entire omics assays missing for a subset of samples).Interpretation: Block-wise missingness is common in multi-omics studies where not all assays were performed on all samples [1]. This requires specialized methods and cannot be handled by simple imputation. |

| 3 | Investigate the Missingness Mechanism | Outcome: A hypothesis on whether data is Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Missing Not at Random (MNAR) [2] [3].Interpretation: MNAR is suspected when missingness is linked to the unobserved value itself (e.g., low-abundance proteins falling below a mass spectrometer's detection limit). This is the most challenging scenario to impute. |

Guide 2: Selecting an Appropriate Imputation Method

Choosing the right imputation method is paramount. The choice depends on your data's missingness pattern, the omics data types, and the sample size. The table below summarizes available methods.

Prerequisites: Completion of Troubleshooting Guide 1.

Required Tools: Imputation software packages (e.g., scikit-learn in Python, missForest, mice in R, or specialized tools like bwm [1]).

| Method Category | Example Methods | Best For / Use Case | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional & Statistical | missForest, PMM, KNNimpute [4] [5] | Cross-sectional data with sporadic, low-level missingness; MCAR/MAR mechanisms. | Often fail to capture complex biological patterns; unsuitable for block-wise missingness or longitudinal data [4]. |

| Deep Learning (Generative) | Autoencoders (AE), Variational Autoencoders (VAE), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [6] [7] | Large, high-dimensional datasets; capturing non-linear relationships and complex patterns within and between omics layers. | Require large sample sizes; can be computationally intensive and complex to train; risk of overfitting [7]. |

| Longitudinal & Multi-timepoint | LEOPARD [4] [8] | Multi-timepoint omics data where a full omics view is missing at one or more timepoints. Uses representation disentanglement to transfer temporal knowledge. | A novel method, requires validation for specific data types beyond the proteomics and metabolomics it was tested on. |

| Block-Wise Missing | bwm R package [1] | Datasets where entire omics blocks are missing for groups of samples. Uses a regularization and profile-based approach. | Performance may slightly decline as the percentage of missing data increases [1]. |

Guide 3: Validating Your Imputation Results

Imputation is an inference, and its accuracy must be assessed. Relying solely on quantitative metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE) is insufficient, as low MSE does not guarantee the preservation of biologically meaningful variation [4].

Prerequisites: A dataset with a ground truth (e.g., a subset of originally observed data) and the imputed dataset.

Required Tools: Downstream analysis tools (e.g., for differential analysis, clustering, classification).

| Validation Approach | Procedure | Interpretation of Success |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Agreement | Artificially mask some known values, impute them, and compare imputed vs. actual values using metrics like MSE or Percent Bias (PB). | A lower MSE/PB indicates better statistical accuracy. This is a basic sanity check. |

| Preservation of Biological Structure | Perform downstream analyses (e.g., differential expression, pathway enrichment, clustering) on both the original (with missingness) and imputed datasets. | The imputed data should recover known biological groups or pathways. For example, LEOPARD-imputed data achieved high agreement in detecting age-associated metabolites and predicting chronic kidney disease [4]. |

| Stability Analysis | Introduce small perturbations to the dataset or use multiple imputation to create several imputed datasets. | Robust biological findings should be consistent across the different imputed versions, indicating the imputation is not introducing spurious noise. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I just remove samples or features with missing data?

While simple, this "complete-case analysis" is strongly discouraged. It drastically reduces sample size, wasting costly collected data and reducing statistical power [2] [1]. More critically, if data is not Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), removing samples can introduce severe bias into your analysis, leading to incorrect conclusions [2].

FAQ 2: What is the difference between "missing values" and "block-wise missing data"?

Missing values typically refer to sporadic, individual data points that are absent within an otherwise populated data matrix (e.g., a specific protein's measurement is missing for one sample). In contrast, block-wise missing data describes a scenario where entire subsets of data are absent. For example, in a study with genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data, a group of samples might have completely missing proteomics data because that assay was not performed on them [1]. This is a common and major challenge in multi-omics integration.

FAQ 3: Are deep learning methods always superior for imputing multi-omics data?

Not always. Deep learning models (like VAEs and GANs) excel at capturing complex, non-linear relationships in large, high-dimensional datasets [6] [7]. However, they often require large sample sizes to train effectively without overfitting. For smaller studies, well-established statistical methods may be more stable and reliable. The choice should be guided by your data's scale and complexity.

FAQ 4: How do I handle missing data in a longitudinal multi-omics study?

Longitudinal data adds a temporal dimension, making the problem more complex. Generic imputation methods that learn direct mappings between views are suboptimal because they cannot capture temporal variation and may overfit to specific timepoints [4]. You need methods specifically designed for this context, such as LEOPARD, which disentangles omics data into time-invariant (content) and time-specific (temporal) representations, allowing it to transfer knowledge across timepoints to complete missing views [4] [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Missing View Completion Using the LEOPARD Framework

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing LEOPARD (missing view completion for multi-timepoint omics data via representation disentanglement and temporal knowledge transfer), a state-of-the-art method for handling block-wise missingness in longitudinal studies [4].

Principle: LEOPARD factorizes multi-timepoint omics data into two latent representations: an omics-specific content (the intrinsic biological signal) and a timepoint-specific temporal knowledge. It then completes a missing view at a target timepoint by transferring the appropriate temporal knowledge to the available omics content.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the LEOPARD Protocol |

|---|---|

| Longitudinal Multi-omics Dataset | The input data containing multiple "views" (e.g., proteomics and metabolomics) measured at multiple timepoints. Some views are completely missing at some timepoints. |

| Content Encoder (Neural Network) | Learns to extract a view-invariant, fundamental biological representation from the input omics data. |

| Temporal Encoder (Neural Network) | Learns to extract a time-specific representation that captures the dynamics and changes across timepoints. |

| Generator with AdaIN | Reconstructs or completes omics views by applying the temporal representation (via Adaptive Instance Normalization) to the content representation. |

| Multi-task Discriminator | Guides the generator to produce imputed data that is indistinguishable from real, observed data. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation and Partitioning:

- Format your data into matrices for each view (e.g., V1, V2) and each timepoint (e.g., T1, T2).

- Partition the samples into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 64%, 16%, 20% as in the original study [4]).

- Artificially mask the view-timepoint block intended for imputation in the test set (e.g., mask view V2 at time T2 for all test samples, denoted as ({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{v={{\rm{v}}}2,t={{\rm{t}}}2}^{{{\rm{test}}}})).

Model Architecture Setup:

- Initialize Networks: Set up the content encoder, temporal encoder, generator, and discriminator neural networks.

- Define Loss Functions: Configure the composite loss function used for training LEOPARD, which includes:

- Contrastive Loss (NT-Xent): Ensures that representations from the same sample are similar and from different samples are distinct.

- Representation Loss: Encourages the disentanglement of content and temporal representations.

- Reconstruction Loss: Measures how well the generator can reconstruct the input from its representations.

- Adversarial Loss: From the discriminator, ensuring generated data is realistic.

Model Training:

- Train the model on the training set by iteratively minimizing the total loss.

- Use the validation set for early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- The model learns to factorize the data and transfer knowledge without directly seeing the missing view-timepoint combination in the training data.

Inference and Imputation:

- Feed the test samples with the missing view into the trained LEOPARD model.

- The model uses the content from an available view and the temporal knowledge from the target timepoint to generate the missing view.

Validation:

- Compare the imputed data against the held-out true values (if available) using quantitative metrics (MSE, PB).

- Perform downstream biological analysis (e.g., association studies, classification) to confirm that the imputed data retains biologically plausible signals [4].

Workflow Diagram: LEOPARD Architecture

Protocol: Handling Block-Wise Missing Data with a Profile-Based Framework

This protocol is based on the bwm R package, which provides a unified feature selection model for datasets with block-wise missingness without relying on imputation [1].

Principle: Instead of imputing missing blocks, the method groups samples into "profiles" based on which omics sources are available. It then learns a unified model across all profiles, integrating information from all available data without discarding samples.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Organize your multi-omics data into matrices, one for each omics source (e.g., Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics).

Profile Identification:

- For each sample, create a binary indicator vector showing the presence (1) or absence (0) of each omics source.

- Convert this binary vector into a decimal number, called the "profile." For example, in a 3-omics study, a sample with only Transcriptomics and Proteomics data would have a vector

[1, 1, 0], which corresponds to a specific profile ID. - Group all samples sharing the same profile.

Model Formulation:

- The framework learns a linear model that integrates the different omics sources. The model is defined as: ( y = \sum{i=1}^{S} \alphai Xi \betai + \epsilon ) where (Xi) is the data matrix for the (i)-th omics source, (\betai) are the feature coefficients for that source, and (\alpha_i) are profile-specific parameters that integrate the sources [1].

- The model is trained using all profiles simultaneously, allowing it to learn from all available data.

Model Fitting and Prediction:

- Use the

bwmR package to fit the model to your data for either regression or classification tasks. - The fitted model can then be used to make predictions on new data, even if the new data has a block-wise missing pattern seen in the training profiles.

- Use the

Workflow Diagram: Profile-Based Handling of Block-Missing Data

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What are the core types of missing data mechanisms? According to Rubin's (1976) framework, missing data mechanisms are classified into three primary types: Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), and Missing Not at Random (MNAR). The key difference lies in whether the probability of a value being missing depends on the observed data, the unobserved data, or neither [9] [10].

Q2: How does the missing data mechanism affect my analysis? The mechanism dictates which statistical methods will provide valid, unbiased results. Simple methods like complete-case analysis often only work under the restrictive MCAR assumption. In contrast, modern methods like multiple imputation are valid under the broader MAR condition. Using a method inappropriate for your data's mechanism can lead to biased estimates and misleading conclusions [9] [11].

Q3: Can I statistically test to determine the missing data mechanism in my dataset? There is no definitive statistical test to distinguish between all mechanisms, particularly between MAR and MNAR [11] [12]. Determining the mechanism is not a purely statistical exercise; it requires careful consideration of the data collection process, subject-matter expertise, and reasoning about the potential causes for missingness [10] [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosis and Handling

Problem: I need a clear, actionable workflow to classify missing data in my omics experiment. This diagnostic flowchart outlines the key questions to ask about your dataset to determine the most likely missing data mechanism.

Problem: I have identified the mechanism and need to select an appropriate imputation method. The suitable method depends on your identified missing data mechanism. The table below summarizes standard and advanced options.

| Mechanism | Recommended Methods | Key Considerations for Omics Data |

|---|---|---|

| MCAR | Complete-case analysis, Mean/Median imputation, Single imputation [9] [11] | While unbiased, complete-case analysis discards data, which can be costly if omics measurements are expensive. Simple imputation may reduce variance artificially. |

| MAR | Multiple Imputation (MICE) [11], Iterative Imputer [13], KNNImputer [14] | These multivariate methods preserve relationships between variables. Ensure your imputation model includes variables that predict missingness to satisfy the MAR assumption. |

| MNAR | Pattern-mixture models, Selection models, Sensitivity analysis [9] | These are complex and require explicit assumptions about the missingness process. Sensitivity analysis is highly recommended to test how results vary under different MNAR scenarios [9]. |

Problem: How do I implement and evaluate these methods in a robust experimental protocol? Below is a generalized workflow for evaluating imputation methods, adaptable for omics datasets.

Protocol: Evaluating Imputation Methods with Simulated Missing Data [15]

- Baseline Dataset: Begin with a high-quality, complete omics dataset. This allows you to know the true values for comparison.

- Simulate Missingness: Artificially introduce missing values under a specific mechanism (e.g., MCAR, MAR). For MAR, you can define a rule where the probability of a value being missing depends on another fully observed variable (e.g., higher missingness in protein abundance for samples with low total ion current).

- Apply Imputation: Run the selected imputation methods (from the table above) on the dataset with simulated missing values.

- Evaluate Performance: Compare the imputed values to the known true values. Common metrics include:

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): Measures the magnitude of imputation errors.

- Preservation of Correlation/Covariance: Assesses if the multivariate structure of the data is maintained.

- Downstream Analysis Impact: For clinical omics, evaluate how imputation affects the sensitivity, AUC, or Kappa values of a final predictive model [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Missing Data Imputation |

|---|---|

Scikit-learn's SimpleImputer |

A univariate imputer for basic strategies (mean, median, most_frequent) under MCAR assumptions [13]. |

Scikit-learn's IterativeImputer |

A multivariate imputer that models each feature with missing values as a function of other features, ideal for MAR data [13]. |

Scikit-learn's KNNImputer |

A multivariate imputer that estimates missing values using the mean value from the 'k'-nearest neighbors in the dataset [13] [14]. |

| Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) | A state-of-the-art framework for creating multiple imputed datasets, accounting for uncertainty and valid under MAR [11]. |

missingno Library (Python) |

A visualization tool for understanding the patterns and extent of missingness in a data matrix prior to imputation. |

| Random Forest Imputation | A machine learning-based approach that can capture complex, non-linear relationships for imputation, often implemented within IterativeImputer [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of missing data in proteomics experiments? Missing data in proteomics frequently arises from the limitations of mass spectrometry technology. Low-abundance proteins may fall below the detection threshold, leading to missing not at random (MNAR) values. Sample handling issues, such as incomplete protein digestion or precipitation, and technical variations between instrument runs (batch effects) are also major contributors [16] [17].

FAQ 2: How does missingness in transcriptomics data differ from metabolomics? In transcriptomics, missing data is often less severe due to the high sensitivity of RNA-seq but can still occur from low RNA quality, low expression levels, or library preparation artifacts. In metabolomics, missingness is more pervasive and typically MNAR, as many metabolites are present at concentrations below the detection limit of the mass spectrometer. The chemical diversity of metabolites also makes it difficult to extract and detect all compounds equally [16] [18].

FAQ 3: What is the impact of batch effects on data missingness? Batch effects themselves may not cause missing data directly, but they complicate data integration. When combining datasets from different batches, the pattern of missing values can become more complex, leading to block-wise missingness where entire omics layers are absent for some sample groups. This severely hampers the ability to apply standard batch-effect correction methods [16] [18].

FAQ 4: Are there imputation-free methods for analyzing incomplete multi-omics datasets? Yes, some advanced methods do not require imputation. The BERT (Batch-Effect Reduction Trees) framework uses a tree-based approach to integrate batches of data, propagating features with missing values through the correction steps without imputation. Other approaches use available-case analysis, creating distinct models for different data availability "profiles" to leverage all available data without filling in gaps [16] [19].

FAQ 5: What are the best practices for handling missing data in multi-omics integration? Best practices include:

- Thorough QC: Implement quality control at every stage, from sample collection to data generation, to minimize preventable missingness [17].

- Understand the Mechanism: Diagnose whether data is Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) or Missing Not at Random (MNAR), as this guides the choice of handling method [20].

- Choose Appropriate Methods: For MNAR data, consider methods like BERT that are robust to non-random missingness. For data integration with block-wise missingness, profile-based or tree-based algorithms can be more effective than simple imputation [16] [19].

- Document and Report: Keep detailed records of all processing steps, including how missing data was handled, to ensure reproducibility [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Widespread Missing Data in a Single Omics Layer

- Symptoms: A high percentage of missing values for a specific data type (e.g., proteomics) across many samples.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Audit Sample Preparation: Review protocols for sample collection, storage, and extraction specific to that omics layer. Degraded samples or improper handling are common culprits [17].

- Check Instrument Logs: Look for technical failures or calibration issues in the instrumentation (e.g., mass spectrometer) during the runs in question [17].

- Analyze Abundance: Plot the distribution of detected values. If missingness is correlated with low signal intensity, the data is likely MNAR, and you should use methods designed for this, such as a left-censored imputation model or BERT [16] [20].

Problem 2: Inability to Integrate Datasets Due to Block-Wise Missingness

- Symptoms: Failure to run integration algorithms because entire blocks of data are missing (e.g., some patient cohorts lack metabolomics data entirely).

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Profile Your Data: Map your samples to "profiles" based on which omics layers are available. This helps visualize the pattern of block-wise missingness [19].

- Use Profile-Aware Algorithms: Employ methods like the two-step algorithm for block-wise missing data, which builds models using all available data within each profile and then combines them, rather than deleting samples with incomplete data [19].

- Leverage Tree-Based Integration: Implement a framework like BERT, which is explicitly designed to handle arbitrarily incomplete omic profiles by correcting pairs of batches and propagating missing features [16].

Problem 3: Poor Model Performance After Imputation

- Symptoms: Predictive models or clustering analyses perform poorly or yield biologically implausible results after imputing missing values.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Revisit Missingness Mechanism: Confirm your imputation method aligns with the nature of your missing data (MCAR vs. MNAR). Using a method for MCAR on MNAR data can introduce severe bias [20].

- Validate with QC Metrics: Use metrics like the Average Silhouette Width (ASW) to compare data integration quality before and after imputation. A good method should improve ASW for biological labels while reducing it for batch labels [16].

- Consider Imputation-Free Models: If imputation continues to fail, switch to models that can handle missing data natively, such as the one described in [19], or use late-integration approaches that build models on individual complete layers before combining results [18].

Quantitative Data on Data Integration Methods

The table below summarizes a performance comparison between two data integration methods, BERT and HarmonizR, as evaluated on simulated datasets with varying levels of missing values [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Data Integration Methods on Simulated Data

| Metric | BERT | HarmonizR (Full Dissection) | HarmonizR (Blocking of 4 Batches) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Retention (with 50% missing values) | Retains all numeric values | Up to 27% data loss | Up to 88% data loss |

| Runtime | Up to 11x faster than HarmonizR | Baseline (slowest) | Faster than full dissection, but slower than BERT |

| Consideration of Covariates | Yes, accounts for severely imbalanced conditions | Not addressed in available results | Not addressed in available results |

Experimental Workflow for Handling Missing Data

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for diagnosing and handling missing data in omics studies, from problem identification to solution implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Omics Data Analysis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Detailed, validated protocols for every stage of data handling (tissue sampling, DNA/RNA extraction, sequencing) to reduce variability and improve reproducibility [17]. |

| Quality Control Software (e.g., FastQC) | Tools that generate quality metrics (Phred scores, read length distributions, GC content) to identify issues in sequencing runs or sample preparation before downstream analysis [17]. |

| Batch-Effect Correction Algorithms (e.g., BERT, ComBat) | Statistical methods to remove non-biological technical biases introduced by processing samples in different batches, times, or on different platforms [16] [18]. |

| Imputation & Integration Software (e.g., bwm R package) | Specialized packages that handle block-wise missing data and multi-class classification tasks without discarding valuable samples, crucial for incomplete multi-omics datasets [19]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Automated systems for proper sample tracking and metadata recording, which reduce human error and prevent sample mislabeling [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary consequences of missing data on my statistical analysis? Missing data can lead to two major problems: a loss of statistical power due to effectively reducing your sample size, and the introduction of systematic bias in your parameter estimates if the data is not Missing Completely at Random (MCAR). This can distort effect estimates, lead to invalid conclusions, and reduce the generalizability of your findings [21] [22] [23]. The extent of the impact depends on the missing data mechanism (MCAR, MAR, or MNAR) and the proportion of data missing.

2. How does the type of missing data (MCAR, MAR, MNAR) affect my downstream biological interpretation? The mechanism of missingness directly influences how much your biological interpretation might be skewed.

- MCAR: Has the least impact on bias, though it can reduce statistical power. Biological conclusions are less likely to be systematically distorted [21] [22].

- MAR: Can introduce bias if not handled properly. However, this bias can often be accounted for using other observed variables in your dataset, allowing for valid biological inference with appropriate methods [22].

- MNAR: This is the most problematic scenario for biological interpretation. Here, the missingness is related to the unobserved value itself (e.g., low-abundance proteins missing in proteomics). This can severely bias biological conclusions, as the missing data is directly informative about the biological state. Specialized imputation methods designed for MNAR (e.g., left-censored methods) are often required [24] [25].

3. I work with multi-omics data where different samples are missing for different omics layers. Is imputation still possible? Yes, this is a common challenge in multi-omics integration. Recent advances in artificial intelligence and statistical learning have led to integration methods that can handle this specific issue. A subset of these models incorporates mechanisms for handling partially observed samples, either by using information from other omics layers to inform the imputation or by employing algorithms that can function with blocks of missing data [5] [3].

4. Which downstream analyses are most sensitive to missing value imputation? Research has shown that differential expression (DE) analysis is the most sensitive to the choice of imputation method. Gene clustering analysis shows intermediate sensitivity, while classification analysis appears to be the least sensitive. Therefore, particular care must be taken when selecting an imputation method for studies focused on identifying differentially expressed biomarkers [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: A cluster analysis after imputation reveals unexpected sample groupings.

Diagnosis: The imputation method may have introduced artificial patterns or obscured true biological signals. Some methods can distort the covariance structure of the data.

Solution:

- Verify the missing data mechanism using visualizations (e.g., heatmaps) and statistical tests like Little's MCAR test [27] [23].

- Re-impute using a method known to better preserve data structures, such as Random Forest or least squares-based methods (LLS, LSA), which were top performers in empirical evaluations [26] [28].

- Compare the cluster stability and biological coherence of the results from different imputation methods. Use the PCA stability metrics to evaluate if the overall sample structure remains consistent after imputation [25].

Problem: The list of statistically significant differentially expressed genes/ proteins changes drastically after imputation.

Diagnosis: This is a common sign that your imputation method is influencing the variance and effect size estimates in your data. This is critical because DE analysis is highly sensitive to imputation choice [26].

Solution:

- Assess the Rate of MNAR: In proteomics and metabolomics, a high rate of MNAR can cause this issue. Evaluate whether methods designed for left-censored data (e.g., QRILC, MinProb) are more appropriate [24] [25].

- Benchmark Performance: If a ground-truth dataset is available, evaluate methods based on the Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) for protein abundance and, more importantly, the accuracy of recovering true positive differential expressions and controlling the false discovery rate [24].

- Select a Robust Method: Studies have shown that Random Forest imputation can consistently achieve a high number of true positives while maintaining a low false altered-protein discovery rate (FADR < 5%) [24].

Performance Comparison of Common Imputation Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of various imputation methods based on large-scale benchmarking studies in omics. NRMSE (Normalized Root Mean Square Error) is a common metric, where a lower value indicates better accuracy.

Table 1: Evaluation of Imputation Method Performance Across Omics Data Types

| Imputation Method | Category | Reported Performance (NRMSE & Biological Impact) | Best Suited For Data Type | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Machine Learning | Consistently low NRMSE; high true positives with low FADR [24] [28] | Genomics, Proteomics [28] [24] | Handles complex interactions; robust to non-linearity |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Local Similarity | Good performance, often second to RF; preserves data structure [28] [25] | Gene Expression, Proteomics [26] [25] | Simple; good for MCAR/MAR; works for numerical/categorical data |

| Bayesian PCA (BPCA) | Global Structure | Top performer in downstream empirical evaluation [26] | Microarray Gene Expression [26] | Effective for low-complexity data; handles global correlations |

| Least Squares Adaptive (LSA) | Local Similarity | Top performer in downstream empirical evaluation [26] | Microarray Gene Expression [26] | Adapts to local data structure; performs well in high-complexity data |

| Local Least Squares (LLS) | Local Similarity | Ranked high in proteomics workflow evaluation [25] | Gene Expression, Proteomics [26] [25] | Combines KNN with regression for improved accuracy |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) | Global Structure | Performance varies; generally outperformed by BPCA and RF [26] [24] | Gene Expression [26] | Captures global trends in the data |

| Quantile Regression Imputation (QRILC) | Left-Censored | Effective for left-censored data (MNAR) [25] | Proteomics, Metabolomics [25] | Specifically designed for MNAR; preserves tail distributions |

| Mean/Median Imputation | Single Value | Poor performance; underestimates variance; not recommended for >5-10% missingness [25] [21] | Any (as a basic baseline only) | Extreme simplicity |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Imputation Method Performance

This protocol is adapted from a comparative study on label-free quantitative proteomics [24] and can be adapted for other omics data types.

Objective: To systematically evaluate the performance of different missing value imputation methods on a dataset where the true values are known.

Required Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Imputation Benchmarking

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Dataset | A complete, high-quality dataset with known values (e.g., spike-in proteins in a complex background) [24]. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Platform for implementing and testing different imputation algorithms. |

| NAguideR Tool | An online/web tool that automates the evaluation of 23 imputation methods for proteomics data [25]. |

| NAsImpute R Package | A dedicated R package to test multiple imputation methods on a user's own genomic dataset [28]. |

Methodology:

- Start with a Complete Dataset: Begin with a high-quality dataset that has no missing values (CD). This serves as your ground truth [26] [24].

- Introduce Simulated Missing Values: Artificially generate missing values into the complete dataset under controlled conditions.

- Vary the overall missing rate (e.g., 10%, 20%, 30%).

- Vary the proportion of MNAR (e.g., 20%, 50%, 80%) to simulate different missingness mechanisms. For MNAR, typically remove low abundance values [24].

- Apply Imputation Methods: Run a suite of imputation methods (e.g., RF, KNN, BPCA, LLS, QRILC) on the datasets with simulated missing values.

- Quantitative Accuracy Assessment:

- Downstream Biological Impact Assessment:

- Perform a key downstream analysis (e.g., differential expression analysis) on both the original complete data and the imputed data.

- Compare the results by calculating:

- The number of True Positives (TPs) correctly identified.

- The False Altered-discovery Rate (FADR), which is the proportion of false positives [24].

- For pathways analysis, check if biologically relevant pathways are consistently detected after imputation [24].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Imputation Evaluation Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical flow for a rigorous experimental evaluation of imputation methods.

Missing Data Impacts on Analysis

This diagram illustrates the causal relationship between the type of missing data and its consequences for statistical analysis.

The Critical Role of Imputation in Multi-Omics Data Integration

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: After integrating multiple omics datasets, your analysis reveals unexpected biological patterns that may be artifacts of missing data rather than true biology.

Solution: Diagnose the missing data mechanism before selecting an integration method [3] [2].

- Check Missing Value Patterns: Create a missingness heatmap to visualize whether missing values cluster by sample group, omics type, or experimental batch. MNAR often shows distinct patterns where low-abundance molecules are systematically missing [25] [29].

- Mechanism-Specific Imputation: Apply methods designed for your specific missing data type. For MNAR data (common in proteomics and metabolomics), use QRILC or MinProb. For MCAR/MAR data, consider KNN, RF, or Bayesian approaches [30] [25] [29].

- Post-Imputation Validation: Use NRMSE (Normalized Root Mean Square Error) and PCA stability metrics to evaluate whether imputation preserves the original data structure without introducing artifacts [25].

Prevention: Implement study designs that minimize missing data through sufficient sample quality controls, standardized protocols, and appropriate sequencing depths or MS detection limits [17].

How to Handle Unmatched Samples Across Omics Layers?

Problem: Your dataset contains samples with complete data for some omics types but missing entire omics profiles for others, creating integration challenges.

Solution: Utilize integration methods specifically designed for unmatched samples or apply advanced imputation strategies.

- Generative Models: Implement deep learning approaches like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) that can learn latent representations from incomplete samples and generate plausible imputations [31] [5].

- Multi-Omics Imputation: Apply methods like MOFA+ or Bayesian networks that can handle missingness at the sample level by leveraging patterns across all available omics data [32].

- Strategic Subsetting: For method validation, create a complete subset of samples to establish baseline patterns, then compare results from your imputed dataset to ensure consistency [3].

Which Imputation Method Should I Choose for My Specific Multi-Omics Study?

Problem: The overwhelming number of available imputation methods makes selecting the optimal approach challenging for your specific data type and research question.

Solution: Match imputation methods to your data characteristics and analytical goals using the decision framework below.

- Data Type Considerations: Proteomics data with abundant MNAR requires different methods (QRILC, MinProb) than transcriptomics data with mostly MCAR (KNN, RF) [25] [29].

- Sample Size Constraints: For small sample sizes (<50), prefer simpler methods like median or quantile regression. For larger datasets (>100), machine learning approaches like RF or deep learning methods become more viable [30].

- Downstream Analysis Alignment: If your goal is differential analysis, choose methods that preserve variance structure (RF, QRILC). For clustering applications, prioritize methods that maintain sample relationships (KNN, VAE) [30] [29].

Validation Protocol: Always implement multiple imputation methods and compare their impact on your downstream analyses using the evaluation metrics in Section 3.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What Are the Main Types of Missing Data in Multi-Omics Studies?

Missing data in multi-omics studies fall into three categories based on the underlying mechanism [3] [2]:

- Missing Completely at Random (MCAR): Missingness occurs randomly with no relationship to observed or unobserved data. Example: technical failures during sequencing [2].

- Missing at Random (MAR): Missingness relates to observed variables but not the missing values themselves. Example: samples with lower overall RNA quality having more missing transcriptomic values [2].

- Missing Not at Random (MNAR): Missingness depends on the actual missing values. Example: protein abundances below mass spectrometry detection limits [25] [2].

How Much Missing Data is Too Much for Reliable Integration?

There's no universal threshold, but these guidelines apply:

- <5% missingness: Most methods perform well; simple imputation (mean, median) may suffice [25].

- 5-20% missingness: Requires more sophisticated methods (KNN, RF, SVD); careful validation needed [30].

- >20% missingness: Advanced methods essential (VAE, Bayesian networks, QRILC); results require extensive validation [30] [32].

- >30% missingness: Consider imputation-free methods or acknowledge significant limitations in interpretation [30].

Critical factors include whether missingness is balanced across sample groups and whether the mechanism is consistent across omics types [30] [3].

Can I Simply Remove Samples or Features with Missing Values?

Removing incomplete samples or features is generally discouraged in multi-omics studies because:

- Data Loss: Removing samples with any missing values across multi-omics datasets can drastically reduce sample size and statistical power [3].

- Bias Introduction: Complete-case analysis assumes data is MCAR, which is rarely true in omics studies, potentially introducing selection bias [3] [2].

- Biological Insight Loss: Removing features with missing values may eliminate biologically important molecules that are differentially present across conditions [25].

Exception: Features with >80% missingness are often removed before imputation, following the "modified 80% rule" [29].

How Do I Validate My Chosen Imputation Method?

Implement a multi-faceted validation approach:

- Statistical Metrics: Calculate NRMSE (Normalized Root Mean Square Error) for imputation accuracy and PCC (Pearson Correlation Coefficient) for relationship preservation [25].

- Structural Preservation: Use PCA to compare data structure before and after imputation, evaluating metrics like explained variance changes and sample displacement [25] [29].

- Biological Plausibility: Check whether imputation results in biologically consistent patterns rather than artifactual clusters or associations [17].

- Downstream Analysis Robustness: Test whether your primary conclusions (e.g., differential expression) remain consistent across different imputation approaches [30].

What Tools Are Available for Multi-Omics Imputation?

Table: Software Tools for Multi-Omics Data Imputation

| Tool Name | Primary Method | omics Types | Missing Data Handling | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BayesNetty | Bayesian Networks | Multi-omics | MNAR/MAR/MCAR | [32] |

| NAguideR | 23 Method Comparison | Proteomics, Metabolomics | MNAR/MAR/MCAR | [25] |

| MetImp | Multiple Methods | Metabolomics | MNAR/MAR/MCAR | [29] |

| VIPCCA/VIMCCA | Variational Autoencoders | Single-cell multi-omics | Unpaired/Paired data | [31] |

| MOFA+ | Factor Analysis | Multi-omics | Missing entire views | [31] |

Performance Evaluation of Imputation Methods

Table: Comparative Performance of Common Imputation Methods Across Omics Types

| Method | MCAR Performance | MNAR Performance | Data Types | Computational Demand | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Good (NRMSE: 0.2-0.4) | Poor (NRMSE: >0.8) | All omics types | Moderate | Preserves local data structure | Fails with high missingness [30] |

| Random Forest (RF) | Excellent (NRMSE: 0.1-0.3) | Fair (NRMSE: 0.5-0.7) | All omics types | High | Handles complex interactions | Computationally intensive [29] |

| QRILC | Fair (NRMSE: 0.4-0.6) | Excellent (NRMSE: 0.1-0.3) | Proteomics, Metabolomics | Low | Specifically for left-censored MNAR | Assumes log-normal distribution [25] [29] |

| Bayesian PCA | Good (NRMSE: 0.2-0.4) | Good (NRMSE: 0.3-0.5) | All omics types | Moderate | Provides uncertainty estimates | Complex implementation [30] |

| Mean/Median | Fair (NRMSE: 0.4-0.6) | Poor (NRMSE: >0.8) | All omics types | Low | Simple, fast | Underestimates variance [25] |

| VAE (Deep Learning) | Excellent (NRMSE: 0.1-0.3) | Good (NRMSE: 0.3-0.5) | All omics types | Very High | Captures complex non-linear patterns | Requires large sample sizes [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluation Framework for Imputation Methods

Purpose: Systematically compare and validate imputation methods for your specific multi-omics dataset.

Materials:

- Multi-omics dataset with known missing value patterns

- Computing environment with sufficient RAM and processing power

- Software tools (R, Python, or specialized imputation packages)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Filter out features with >80% missingness across samples [29].

- Missingness Characterization: Visualize missing value patterns using heatmaps and quantify missingness per sample and per feature.

- Method Application: Apply 3-5 candidate imputation methods appropriate for your suspected missing data mechanism.

- Validation: Implement the following evaluation pipeline:

Evaluation Metrics:

- NRMSE: Calculate using known values artificially set to missing [25] [29].

- PCA Stability: Assess sample clustering consistency before and after imputation [25].

- Correlation Structure: Compare correlation patterns between complete and imputed datasets [29].

Protocol 2: Handling MNAR Data in Proteomics/Matabolomics

Purpose: Specifically address left-censored missing data common in mass spectrometry-based proteomics and metabolomics.

Materials:

- MS-based quantification data

- R environment with

imputeLCMDandNAguideRpackages [25]

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Perform normalization and log-transformation of your intensity data.

- MNAR Diagnosis: Confirm left-censored mechanism by analyzing missingness vs. abundance relationships.

- QRILC Implementation:

- MinProb Alternative: Apply probabilistic minimum imputation for comparison:

- Distribution Validation: Compare distributions of imputed vs. observed values using quantile-quantile plots.

Troubleshooting: If imputation creates outliers or distorts distributions, adjust tuning parameters or consider a hybrid approach combining QRILC with KNN.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Imputation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Packages | imputeLCMD, missForest, VIM |

MNAR imputation, Random Forest imputation | General multi-omics imputation |

| Python Libraries | scikit-learn, Autoimpute, DataWig |

KNN, MICE, Deep learning imputation | Large-scale multi-omics data |

| Specialized Software | NAguideR, MetImp, BayesNetty |

Method comparison, Metabolomics imputation, Bayesian networks | Method selection, Targeted analysis |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch |

Variational Autoencoders, GANs | Complex multi-omics integration |

| Workflow Managers | Nextflow, Snakemake |

Pipeline reproducibility | Production-scale imputation |

Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram provides a systematic approach for selecting the appropriate imputation method based on your data characteristics and research goals:

From Simple Replacement to AI: A Practical Catalog of Imputation Techniques

Single-value imputation refers to a family of techniques where each missing value in a dataset is replaced with one specific, estimated value. This approach transforms an incomplete dataset into a complete matrix that can be analyzed using standard statistical methods. These procedures do not define an explicit model for the partially missing data but instead fill gaps using algorithms ranging from simple value substitution to more sophisticated predictive methods [33].

In omics research, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, missing values routinely occur due to various technical and biological factors. In mass spectrometry-based proteomics, for instance, missing values may arise from proteins existing at abundances below instrument detection limits, sample loss during preparation, or poor ionization efficiency. These missingness mechanisms are broadly categorized as Missing at Random (MAR) or Missing Not at Random (MNAR), with MNAR being particularly prevalent in proteomic data where values are missing due to abundance-dependent detection limitations [24]. Single-value replacement methods provide a practical solution to enable downstream statistical analyses that require complete datasets.

FAQ: Understanding Single-Value Replacement

1. What is the fundamental difference between single and multiple imputation?

Single imputation fills each missing value with one specific estimate, creating a single complete dataset that can be analyzed with standard methods. However, it does not account for the uncertainty inherent in the estimation process. In contrast, multiple imputation generates several different plausible values for each missing data point, creating multiple complete datasets. Analyses are performed across all datasets, and results are pooled, providing standard errors that reflect both sampling variability and uncertainty about the missing values [33].

2. When is single-value replacement most appropriate for omics data?

Single-value replacement is particularly suitable when:

- The proportion of missing data is relatively low (e.g., <10-20%)

- The analysis method requires a complete data matrix and is robust to minor estimation errors

- Computational efficiency is a priority for large-scale datasets

- The data structure suggests a clear imputation model (e.g., MNAR mechanisms in proteomics where left-censored methods are appropriate) [24] [33]

3. What are the primary limitations of single-value replacement methods?

The main limitations include:

- Distortion of variance: Treated as actual observations, imputed values don't reflect estimation uncertainty

- Biased estimates: Variances and covariances are often biased toward zero when using mean imputation

- Distorted data structure: The filled-in values may not preserve the original joint distribution of variables

- Risk of artifactual findings: Spurious patterns may be introduced if the imputation model is inappropriate [33]

4. How does the missingness mechanism (MNAR vs. MAR) affect method selection?

The missingness mechanism significantly impacts method performance:

- For MNAR data (common in proteomics), left-censored methods like LOD or random drawing from a left-censored normal distribution are often appropriate as they replace missing values with small values near the detection limit

- For MAR data, methods that leverage correlations between variables (e.g., kNN, regression imputation) typically perform better as they use observed data to predict missing values [24]

5. What validation approaches are recommended after imputation?

Performance validation should include:

- Assessing impact on downstream analyses (e.g., differential expression results)

- Comparing known spike-in values with imputed values when available

- Evaluating the preservation of biological signatures and pathways

- Using normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) to quantify imputation accuracy when true values are known [24]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Distorted Variance After Imputation

Issue: After applying single-value replacement, variance estimates and covariances are biased toward zero, affecting downstream statistical tests.

Solution: Apply statistical adjustments to correct for bias:

- For unconditional mean imputation, multiply the sample variance from filled-in data by (n-1)/(n(j)-1), where n is total sample size and n(j) is the number of observed values for variable j [33]

- Consider stochastic regression imputation instead of deterministic methods, as it preserves more natural variability by adding random noise to predictions [33]

Prevention: Use methods that preserve data structure better, such as stochastic regression imputation or maximum likelihood approaches, particularly when variance estimation is critical to your analysis.

Problem: Poor Performance with High Missingness Rates

Issue: When missing value rates exceed 20-30%, single-value replacement methods produce unreliable estimates and distort data structure.

Solution:

- Consider multiple imputation methods for high missingness rates (>20%)

- Implement methods specifically designed for high missingness scenarios in omics data (e.g., random forest-based imputation)

- Evaluate whether the analysis can be restricted to features with lower missingness rates [24]

Prevention: Optimize experimental design to minimize missing values through technical replicates, adequate sample quality control, and using platforms with demonstrated low missing value rates.

Problem: Inconsistent Biological Results After Imputation

Issue: Downstream analyses (pathway analysis, clustering) yield different biological interpretations depending on the imputation method used.

Solution:

- Compare multiple imputation methods using validation metrics when possible

- Apply method consistency checks using known biological positives (e.g., spike-in proteins, established pathway alterations)

- Use ensemble approaches or select methods that demonstrate better performance in benchmarking studies for your data type [24]

Prevention: Document and report the imputation method and parameters as part of your analysis pipeline to ensure reproducibility.

Performance Comparison of Single-Value Replacement Methods

Table 1: Comparison of single-value imputation methods for omics data

| Method | Mechanism | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Mean | Replaces with column mean | Simple, preserves mean | Severely underestimates variance, distorts distributions | Initial data exploration only [33] |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | Uses similar samples/features | Captures local structure, handles MAR | Sensitive to k choice, computational cost for large datasets [24] | Gene expression data with moderate missingness [5] |

| Left-Censored (LOD, ND) | Replaces with low values near detection limit | Biologically plausible for MNAR | May introduce bias if MNAR assumption incorrect [24] | Proteomics data with abundance-dependent missingness [24] |

| Regression Imputation | Predicts using observed variables | Uses correlation structure, efficient | Overfits with many variables, inflates correlations [33] | Datasets with strong variable correlations |

| Random Forest (RF) | Machine learning prediction | Handles complex interactions, robust | Computationally intensive, complex implementation [24] | Various omics data, shown to outperform other methods [24] |

| Stochastic Regression | Regression with added random noise | Preserves variance better than deterministic | Requires appropriate error distribution specification [33] | When variance preservation is important |

Table 2: Performance metrics of imputation methods from proteomics benchmarking study [24]

| Method | NRMSE (20% MNAR) | NRMSE (50% MNAR) | NRMSE (80% MNAR) | True Positives | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Lowest | Lowest | Lowest | High | <5% |

| kNN | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Medium | 5-15% |

| LOD | Higher | Higher | Lower | Low | Variable |

| SVD | Intermediate | Intermediate | Higher | Medium | 5-15% |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Benchmarking Protocol for Imputation Methods

Objective: Systematically evaluate the performance of single-value replacement methods using a ground-truth dataset.

Materials:

- Complete omics dataset with known values (e.g., spike-in proteins in proteomics)

- Computing environment with imputation algorithms implemented

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Start with a complete dataset (no missing values) where true values are known

- Missing Value Introduction: Artificially introduce missing values with specified rates (e.g., 10%, 20%, 30%) and MNAR mechanisms (e.g., 20%, 50%, 80% MNAR)

- Method Application: Apply each imputation method to the dataset with introduced missingness

- Performance Calculation:

- Compute Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) between imputed and true values

- Compare protein ratios between groups after imputation

- Calculate true positives and false discovery rates for differential expression analysis

- Biological Validation: Assess whether relevant biological pathways are detected after imputation [24]

Expected Outcomes: Quantitative metrics enabling objective comparison of method accuracy and impact on downstream analyses.

Parameter Optimization Protocol

Objective: Determine optimal parameters for each imputation method to maximize performance.

Materials: Dataset with representative missingness patterns for your omics platform

Procedure:

- kNN: Test k-values (number of neighbors) from 5-20, select value minimizing NRMSE

- SVD/BPCA: Test number of principal components (1-10), select optimal based on NRMSE

- Random Forest: Test number of trees (50-500), though method is generally robust to this parameter [24]

- Validation: Use cross-validation or holdout dataset to prevent overfitting

Expected Outcomes: Method-specific parameter settings optimized for your data type and missingness patterns.

Workflow Visualization

Imputation Method Evaluation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key platforms and reagents for single-cell omics studies involving missing data

| Platform/Reagent | Function | Application Context | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Chromium | High-throughput scRNA-seq | Large-scale single-cell studies | Higher multiplet rates, requires high cell input [34] |

| BD Rhapsody | Microwell-based single-cell analysis | Targeted transcriptomics | Lower recovery rates, fixed panel design [34] |

| cellenONE | Image-based single-cell dispenser | Rare cell analysis, high accuracy | Lower throughput but superior cell selection [34] |

| IonStar MS Workflow | Label-free quantitative proteomics | Proteomics with low missing values | High-quality data for benchmarking [24] |

| CITE-seq/REAP-seq | Multimodal protein and RNA measurement | Cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes | Limited by antibody availability [35] |

| SPLIT-seq | Low-cost scRNA-seq method | Cost-effective large-scale studies | Higher technical noise and missing values |

Core Concepts: kNN Imputation

What is kNN imputation and how does it work?

k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) imputation is a data preprocessing technique used to fill missing values by leveraging the similarity between data points [36]. It operates on a simple principle: for any sample with a missing value, find the 'k' most similar samples (neighbors) in the dataset that have the value present, and use their values to estimate the missing one [37] [38].

The process involves three key steps [37]:

- Identifying Missing Values: The algorithm first locates all missing values (typically encoded as NaN) in the dataset.

- Finding Nearest Neighbors: For each data point with a missing value, it calculates distances to all other samples using a specified distance metric (like Euclidean distance), considering only the features where both points have observed values.

- Imputing Missing Values: The missing value is then imputed using the mean (for continuous data) or mode (for categorical data) of the corresponding values from the k-nearest neighbors.

What are the advantages of kNN imputation over simpler methods for omics data?

kNN imputation offers several advantages that make it particularly valuable for omics data analysis [36] [38]:

- Preserves Data Relationships: Unlike mean/median imputation which can distort variance and relationships, kNN retains the local structure and correlations within the dataset, which is crucial for maintaining biological signals in omics data.

- Non-Parametric: kNN does not make strong assumptions about data distribution, providing flexibility for various omics data types that may not follow standard distributions.

- Handles Multivariate Patterns: Uses multiple features simultaneously to predict missing values, capturing complex biological relationships that univariate methods miss.

- Adapts to Local Patterns: By finding similar samples, it can accommodate subgroup-specific patterns that might exist in heterogeneous omics datasets.

What are the main limitations of kNN imputation in omics research?

Despite its advantages, kNN imputation has several limitations that researchers should consider [36] [38]:

- Computational Intensity: The algorithm requires calculating pairwise distances between all samples, which becomes computationally expensive for large omics datasets with thousands of samples.

- Sensitivity to Data Sparsity: Struggles when too many missing values exist, as there may not be enough complete cases to find reliable neighbors.

- Dependence on Parameter Tuning: Performance heavily depends on appropriate selection of k (number of neighbors) and the distance metric.

- Requires Complete Features for Neighbors: Cannot impute values when all samples have missing values for a particular feature.

- Assumes Similarity Implies Similar Values: May perform poorly when the missingness mechanism is non-random (NMAR) and related to the missing values themselves.

Implementation and Experimental Protocols

How do I implement basic kNN imputation in Python?

Here's a basic implementation using scikit-learn's KNNImputer [37] [14]:

What is the detailed experimental protocol for kNN imputation in omics studies?

A robust experimental protocol for kNN imputation in omics research should include these key steps [37] [36]:

Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize/normalize numerical features to ensure equal weighting in distance calculations

- Encode categorical variables numerically if present

- Identify and document missing value patterns

Parameter Optimization:

- Use cross-validation to determine optimal k (typically 3-10)

- Test different distance metrics (Euclidean, Manhattan, cosine)

- Evaluate weighting schemes (uniform vs. distance-based)

Model Training and Validation:

- Split data into training and validation sets

- For validation, artificially introduce missing values into complete cases

- Compare imputed values to ground truth using appropriate metrics

Downstream Analysis:

- Assess impact on downstream analyses (differential expression, clustering)

- Compare with alternative imputation methods

- Perform sensitivity analysis to evaluate robustness

How can I handle mixed data types (numerical and categorical) with kNN imputation?

Handling mixed data types requires preprocessing to make categorical variables compatible with kNN distance calculations [37]:

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Why is my kNN imputation producing poor results, and how can I improve them?

Poor kNN imputation performance can stem from several sources. Here are common issues and solutions [36] [38]:

Problem: Suboptimal choice of k

- Solution: Use cross-validation to find the optimal k. Start with k=3-5 and test increasing values. Smaller k captures local structure but may be noisy; larger k provides smoothing but may overlook important local patterns.

Problem: Improper feature scaling

- Solution: Always standardize (z-score normalize) or normalize (scale to [0,1]) numerical features before imputation to prevent features with larger scales from dominating distance calculations.

Problem: High percentage of missing data

- Solution: kNN works best with ≤30% missingness. For higher percentages, consider alternative methods or use rowmaxmissing parameter to exclude samples with excessive missing values.

Problem: Inappropriate distance metric

- Solution: Test different metrics: Euclidean (standard), Manhattan (more robust to outliers), or cosine similarity (for high-dimensional data).

How do I assess whether kNN imputation is working correctly for my omics data?

Use these validation strategies to evaluate kNN imputation quality [36]:

Statistical Consistency Checks:

- Compare distributions before and after imputation using histograms and Q-Q plots

- Check that imputed values fall within biologically plausible ranges

- Verify that correlation structures between variables are preserved

Validation Using Artificial Missingness:

- Artifically remove known values (5-10%) from complete cases

- Impute these artificial missing values and compare to actual values

- Calculate RMSE, MAE, or other accuracy metrics

Downstream Task Performance:

- Compare performance of classification or clustering models using imputed vs. complete-case data

- Assess whether biological conclusions remain consistent

Comparison with Alternative Methods:

- Benchmark against mean/median imputation, MICE, or other methods

- Evaluate if kNN provides substantive improvement for your specific analysis

Why is kNN imputation so slow with my large omics dataset, and how can I speed it up?

kNN imputation has computational complexity that scales quadratically with sample size, making it slow for large datasets. Consider these optimizations [36] [38]:

Algorithmic Optimizations:

- Reduce dataset dimensionality using PCA or feature selection before imputation

- Use approximate nearest neighbor algorithms instead of exact search

- Implement data sampling techniques for parameter tuning

Implementation Strategies:

- Set

copy=Falsein KNNImputer for in-place operations to reduce memory usage - Use efficient data structures and sparse matrix representations where possible

- Leverage GPU acceleration if available

- Set

Practical Workarounds:

- For very large datasets, consider alternative methods like Random Forest imputation

- Process data in batches or subsets when feasible

- Use the

col_max_missingparameter to exclude features with excessive missingness

Performance and Benchmarking

How does kNN imputation performance compare across different missingness mechanisms?

Recent benchmarking studies reveal important performance patterns across missing data mechanisms [39]:

Table 1: kNN Imputation Performance Across Missingness Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Description | kNN Performance | Considerations for Omics Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCAR (Missing Completely at Random) | Missingness independent of any variables | Best performance | Works well for technical missingness in omics |

| MAR (Missing at Random) | Missingness depends on observed variables | Good performance | Common in omics; requires relevant variables are observed |

| MNAR (Not Missing at Random) | Missingness depends on unobserved factors or the value itself | Poorest performance | Problematic for biological missingness (e.g., low-abundance molecules) |

How does kNN imputation compare to other methods for omics data?

Table 2: Method Comparison for Omics Data Imputation

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best Suited for Omics Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| kNN Imputation | Preserves local structure, non-parametric, intuitive | Computationally intensive, sensitive to k choice, struggles with high missingness | Medium-sized datasets (<10,000 samples), when biological subgroups exist |

| Mean/Median Imputation | Simple, fast | Distorts distributions, underestimates variance, biases downstream analysis | Not recommended except for quick exploratory analysis |

| MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations) | Accounts for uncertainty, flexible model specification | Complex implementation, computationally intensive, difficult with high dimensions | When uncertainty quantification is crucial, smaller datasets with complex relationships |

| Matrix Factorization | Handles high sparsity, captures global patterns | Requires tuning of rank parameter, may oversmooth local patterns | Very large datasets, collaborative filtering scenarios |

| Deep Learning Methods (Autoencoders, VAEs, GANs) | Captures complex non-linear relationships, handles high-dimensional patterns | Complex implementation, requires large datasets, computationally intensive | Large-scale multi-omics integration, complex biological patterns |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for kNN Imputation in Omics Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn KNNImputer | Primary implementation of kNN imputation | Native in scikit-learn ≥0.22; most accessible and well-documented option [37] [14] |

| missingpy | Alternative implementation with additional features | Supports both kNN and MissForest (Random Forest imputation) [40] |

| fancyimpute | Comprehensive imputation package | Multiple advanced algorithms but may have compatibility issues with newer Python versions [41] |

| Scikit-learn preprocessing tools (StandardScaler, OrdinalEncoder) | Data preprocessing for kNN | Essential for normalizing features and encoding categorical variables [37] |

| PCA and feature selection tools | Dimensionality reduction | Critical for improving performance with high-dimensional omics data [36] |

Workflow and Algorithm Visualization

kNN Imputation Workflow

kNN Parameter Relationships

Frequently Asked Questions

What are global structure methods, and why are they used for imputation? Global structure methods, such as SVD, leverage the overall correlation structure of the entire dataset to estimate missing values. Unlike methods that only use similar rows or columns, they can provide more accurate imputation for datasets where many variables are interrelated, which is common in omics data [42].

My data has values Missing Not at Random (MNAR). Can I still use SVD? Yes. While it was once thought model-based methods were only for MAR data, studies show that SVD and other matrix factorization methods can effectively model both MAR and MNAR missingness by identifying underlying patterns in the data [42].

How do I choose the rank (number of components) for SVD imputation? The choice of rank (

k) is a trade-off between capturing signal and avoiding noise. A common method is to examine the scree plot of singular values and choosekwhere the values plateau. You can also use theirlbapackage in R for fast computation of a partial SVD, which is efficient for large omics matrices [42] [43].Should I impute before or after normalizing my data? The sequence can impact results. Some research suggests imputation of normalized data might be beneficial, but this is often context-dependent. A systematic, benchmarking analysis on your specific data type is recommended to determine the optimal workflow [42].

What are the main advantages of SVD over other imputation methods? SVD provides an optimal low-rank approximation of your data, effectively denoising while imputing. It is also a highly robust and scalable algorithm, offering a good balance of accuracy and computational speed, especially for large datasets where methods like Random Forest (RF) become very slow [42] [43].

Is there a method related to SVD that can handle missing data iteratively? Yes, the Non-linear Iterative Partial Least Squares (NIPALS) algorithm is a classical method that can compute the principal components of a dataset with missing values, thereby enabling an SVD-like decomposition and imputation without requiring a complete matrix to start.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: SVD Algorithm Fails on Incomplete Matrix

- Symptoms: Your software returns an error such as "Matrix contains NA/NaN/Inf" or "SVD does not support missing values."

Background: Standard SVD implementations in libraries (e.g., NumPy, base R) require a complete numeric matrix. Your omics data matrix contains missing values, which must be handled before the decomposition.

Solution 1: Use an SVD-based imputation algorithm

- Concept: These methods iteratively perform SVD while updating the missing values, converging to a complete matrix.

- Protocol:

- Initialization: Replace all missing values with initial estimates (e.g., column means).

- Decomposition: Perform a low-rank SVD on the current complete matrix.

- Reconstruction: Reconstruct the matrix using the top

kcomponents: ( X{\text{reconstructed}} = Uk \Sigmak Vk^T ). - Imputation: Replace the previously missing values in your original matrix with the corresponding values from ( X_{\text{reconstructed}} ).

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until the values in the missing positions converge (i.e., the change between iterations falls below a set tolerance).

Solution 2: Use a dedicated software function

- Concept: Many bioinformatics packages have built-in functions that implement the iterative SVD process.

- Protocol:

- In R, you can use the

impute.svd()function from thebcvpackage or thepcaMethodssuite [42]. - In Python, the

fancyimputelibrary provides anIterativeSVDcompleter.

- In R, you can use the

Problem: Poor Imputation Accuracy After SVD

- Symptoms: After imputation, downstream analyses (e.g., clustering, differential expression) yield poor or nonsensical results.

Background: Accuracy can be compromised by an incorrect number of components, the nature of the missing data, or the data's scaling.

Solution 1: Optimize the number of components (

k)- Protocol:

- Artificially introduce missing values into a complete subset of your data (e.g., 10%) where the true values are known. This is a "holdout" test.

- Run the SVD imputation algorithm with different values of

k. - For each

k, calculate the error (e.g., Root Mean Square Error) between the imputed and the known true values for the holdout set. - Select the

kthat minimizes this error.

- Protocol:

Solution 2: Re-evaluate the missing data mechanism

- Protocol:

- Assess Missingness Pattern: Plot the missing value heatmap and the distribution of missingness against intensity (log2) [42]. A concentration of missing values at low intensities suggests MNAR.

- Choose Method Accordingly: If MNAR is dominant, consider combining SVD with a method tailored for left-censored data, or ensure your SVD implementation is robust to such patterns, as some studies indicate it can be effective [42].

- Protocol:

Solution 3: Check data pre-processing

- Protocol: Ensure the data is properly transformed and normalized before imputation, as the performance of SVD can be sensitive to the data distribution [42].

Problem: SVD is Computationally Slow on Large Omics Dataset

- Symptoms: The imputation process takes an extremely long time or runs out of memory.

Background: The computational complexity of a full SVD is high for large matrices (e.g., thousands of genes and samples).

Solution 1: Use a partial SVD

- Concept: Instead of computing all components, calculate only the top

kthat explain most of the variance. - Protocol:

- In R, use the

irlba()function for fast partial SVD [42]. - In Python, use

scipy.sparse.linalg.svds.

- In R, use the

- Concept: Instead of computing all components, calculate only the top

Solution 2: Improve the algorithm implementation

- Concept: Some SVD implementations are more optimized than others.

- Protocol: Benchmark different packages. For instance, the

bigomics/playbasesource code offers a modifiedsvdImpute2()function reported to be 40% faster than the originalpcaMethodsimplementation [42].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Benchmarking Imputation Methods Using a Holdout Set

Purpose: To empirically evaluate and compare the accuracy of different imputation methods (e.g., SVD, KNN, BPCA) on your specific omics dataset.

- Preparation: Start with a complete or nearly complete dataset (X_original).

- Introduction of Missing Values: Randomly remove a known percentage (e.g., 10-20%) of values from Xoriginal to create an incomplete matrix (Xincomplete). Keep a record of the removed values and their positions (Mask_matrix).

- Imputation: Apply each imputation method (SVD, KNN, etc.) to Xincomplete to generate an imputed matrix (Ximputed).

- Accuracy Calculation: For each method, calculate the error between the imputed values and the original values in the holdout set. Common metrics include:

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): Measures the magnitude of the average error.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Less sensitive to large outliers than RMSE.