Integrative Multi-Omics Approaches in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Molecular Mechanisms to Precision Medicine

This comprehensive review explores how multi-omics technologies are revolutionizing our understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) by integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and microbiome data.

Integrative Multi-Omics Approaches in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Molecular Mechanisms to Precision Medicine

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores how multi-omics technologies are revolutionizing our understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) by integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and microbiome data. We examine foundational discoveries in ASD molecular architecture, advanced methodological frameworks for data integration, statistical solutions for analytical challenges, and validation approaches across model systems and human cohorts. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights how multi-omics integration enables molecular subtyping, reveals convergent biological pathways, and identifies novel therapeutic targets, ultimately advancing precision medicine approaches for this heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder.

Unraveling ASD Complexity: Key Molecular Discoveries Through Multi-Omics Integration

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by substantial genetic heterogeneity. Once conceptualized primarily through protein-coding mutations, the genetic architecture of ASD now encompasses a broad spectrum of variation spanning coding regions, regulatory elements, and epigenetic modifications framed within a multi-omics context [1] [2]. The integration of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and microbiome datasets has revealed that ASD pathophysiology operates through cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms and interacting biological systems, particularly along the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis [1]. This technical overview examines the evolving understanding of ASD genetic architecture, from early findings of coding variants to the emerging role of non-coding regulatory elements and their interplay within multi-omics frameworks.

Historically, genetic research focused on protein-coding regions, identifying numerous rare and de novo mutations with large effect sizes [3]. However, gene sequences constitute merely 2% of the human genome [4] [2]. Recent investigations have established that inherited variations in non-coding sections of DNA, particularly cis-regulatory elements (CREs), contribute significantly to ASD risk [4] [2]. These regulatory elements control gene expression without altering protein sequences and exhibit distinct inheritance patterns, being transmitted predominantly from fathers rather than mothers [4] [2].

Advances in computational frameworks and large-scale data integration have further revealed that ASD comprises biologically distinct subtypes with discrete genetic profiles and developmental trajectories [5] [6] [7]. These findings underscore that ASD does not represent a single entity with unitary genetic etiology, but rather a spectrum of conditions with diverse underlying biological mechanisms that can be systematically classified and understood through integrated multi-omics approaches.

Coding Variants in ASD: Spectrum and Impact

Variant Classes and Functional Consequences

Protein-coding variants in ASD risk genes span several functional categories with differing effect sizes and inheritance patterns. De novo mutations—genetic changes appearing for the first time in affected individuals—contribute to approximately one-third of ASD cases [2]. These typically exhibit large effect sizes and occur predominantly in genes involved in neuronal communication, synaptic function, and chromatin remodeling [3]. Current genetic testing identifies pathogenic coding variants in approximately 20% of ASD cases, with no single mutation accounting for more than 1% of cases [1] [6].

Table 1: Major Classes of Coding Variants in ASD

| Variant Class | Population Frequency | Biological Impact | Associated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo LoF Variants | 5.1% of ASD cases [4] | Protein truncation or complete loss of function | CHD8, SCN2A, ADNP [3] |

| Inherited Coding SVs | 1.21% of ASD cases [4] | Altered gene dosage through deletions/duplications | DLG3, KAT6A, MECP2 [3] |

| Inherited Pathogenic Variants | 1.9% of ASD cases [4] | Disrupted protein function through missense changes | BCORL1, CDKL5, SETD1B [3] |

| X-Linked Variants | Variable, male-biased | Hemizygous disruption in males | AR, SLC6A8 [3] |

Gene Functional Convergence and Expression Patterns

Despite genetic heterogeneity, ASD risk genes converge on specific biological pathways and developmental processes. Nervous system development and neurogenesis represent primary domains enriched for ASD-associated coding variants [3]. Signal transduction pathways, particularly those regulating synaptic function and neuronal connectivity, also show significant enrichment [3].

Spatial and temporal expression patterns further refine our understanding of ASD pathogenesis. Genes harboring damaging variants show selective enrichment in specific brain regions, particularly the thalamus [3]. The developmental timing of gene expression also varies across ASD subtypes, with some genetic influences predominantly affecting prenatal brain development while others impact postnatal neural circuit refinement [6]. In the Social and Behavioral Challenges ASD subtype, impacted genes are primarily active after birth, aligning with the later diagnosis and absence of developmental delays in this group [6]. Conversely, genes associated with the Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay subtype show predominantly prenatal activity [6].

Non-Coding Regulatory Elements in ASD

Cis-Regulatory Elements and Their Characteristics

Cis-regulatory elements (CREs) encompass promoter regions, enhancers, silencers, and insulators that collectively regulate gene expression without altering protein sequence. Structural variants in non-coding regions containing CREs (CRE-SVs) contribute to approximately 0.77% of ASD cases [4]. These regulatory variants exert their effects by disrupting the binding sites for transcription factors, thereby modulating the expression of target genes, sometimes over considerable genomic distances.

CRE-SVs differ from coding variants in ASD in two fundamental aspects: their inheritance patterns and their mechanisms of action. Unlike de novo coding mutations, CRE-SVs associated with ASD are typically inherited rather than spontaneously arising [2]. Furthermore, they exhibit a paternal origin effect, being transmitted predominantly from fathers to affected offspring [4] [2]. This contrasts with the maternal origin effect observed for some protein-coding variants and suggests distinct selective pressures on regulatory versus coding regions [2].

Table 2: Regulatory Element Classes in ASD Pathogenesis

| Element Type | Genomic Features | Functional Role | ASD Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancers | Distal to promoters (>2kb from TSS), H3K27ac marked | Enhance transcription of target genes | Midbrain GABAergic neuron enhancers [8] |

| Promoters | Proximal to TSS, H3K4me3 marked | Initiate transcription | ESRRB in Purkinje cells [8] |

| Insulators | CTCF binding sites, often methylated | Establish chromatin boundaries | CTCF/cohesin loop domains [9] |

| Silencers | Repressive marks (H3K9me3) | Repress gene expression | B compartment regions [9] |

3D Chromatin Architecture in Neurodevelopment

The three-dimensional organization of chromatin in the nucleus provides a critical framework for gene regulation, with particular relevance for neurodevelopment. Chromatin is organized into compartments (A: active, B: inactive), topologically associated domains (TADs), and CTCF/cohesin-mediated loops that bring distant regulatory elements into proximity with their target genes [9].

During human first-trimester neurodevelopment, the number of accessible chromatin regions increases both with age and along neuronal differentiation trajectories [8]. This dynamic accessibility reflects the unfolding regulatory landscape that guides brain patterning and cellular differentiation. The functional architecture of the genome is exceptionally fluid during this period, with transcription factor binding and regulatory element activity being both cell-type-specific and transient [8].

Disruptions to this elaborate chromatin tapestry represent a key mechanism in ASD pathogenesis. Genetic lesions affecting chromatin remodelers, histone modifiers, or architectural proteins can create ripple effects across the entire epigenome [9]. For example, defects in the high-risk ASD gene CHD8, which encodes a chromatin remodeling factor, can induce abnormal microglial activation in the brain while simultaneously disrupting intestinal immune homeostasis—illustrating how chromatin-level disturbances can mediate cross-system pathology in ASD [1].

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches and Methodologies

Experimental Workflows for Multi-Omics Integration

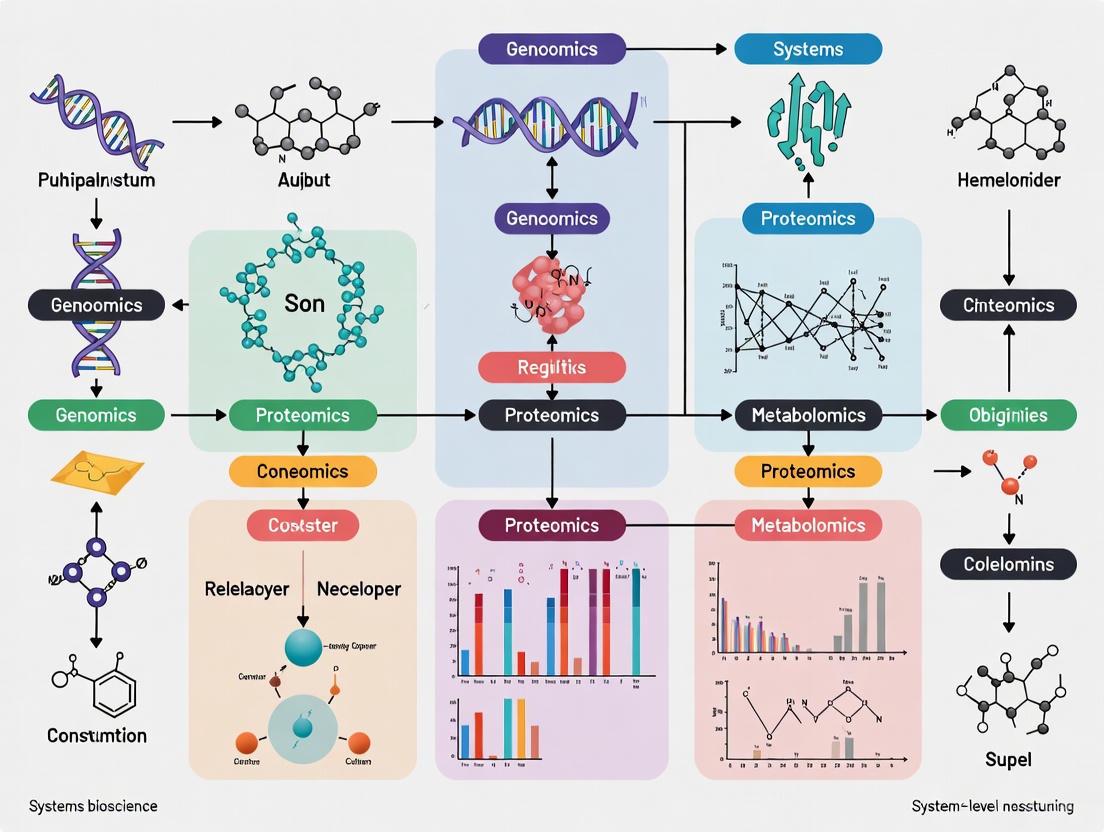

Advanced methodologies enabling the integration of multiple data modalities have been instrumental in elucidating the complex genetic architecture of ASD. The following diagram illustrates a representative multi-omics workflow for identifying cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms in ASD:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Experimental Platforms for ASD Multi-Omics Research

| Platform/Reagent | Specific Application | Technical Function | Representative Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Single-Cell Multiome | Parallel scATAC-seq + scRNA-seq | Links chromatin accessibility to gene expression | First-trimester neurodevelopment atlas [8] |

| Illumina Whole Genome Sequencing | Genome-wide variant discovery | Identifies coding and non-coding variants | SPARK cohort analysis [5] [6] |

| Hi-C/Micro-C | 3D chromatin architecture | Maps long-range chromatin interactions | Compartment and loop identification [9] |

| METAL | GWAS meta-analysis | Fixed-effects model integration | Combining multiple ASD datasets [1] |

| LD Score Regression | Genetic correlation estimation | Quantifies trait genetic overlap | ASD-FSS genetic correlations [10] |

| Growth Mixture Modeling | Developmental trajectory analysis | Identifies latent longitudinal classes | SDQ trajectory and age at diagnosis [7] |

| Cicero | Enhancer-gene linkage | Predicts cis-regulatory interactions | Candidate CRE identification [8] |

Methodological Protocols for Key Analyses

GWAS Meta-Analysis Protocol: Large-scale genetic association studies employ meta-analysis to boost statistical power. The standard protocol involves: (1) Dataset harmonization using CrossMap (v0.6.5) for genomic coordinate conversion between assemblies and PLINK (v1.9) for allele alignment; (2) Fixed-effects meta-analysis in METAL with SCHEME STDERR and STDERR SE weighting strategies; (3) Heterogeneity assessment using Cochran's Q and I² indices, with random-effects models applied when significant heterogeneity is detected (Q test P < 0.1, I² > 50%); (4) Novel locus identification by excluding SNPs within 500kb of known associated regions [1].

Single-Cell Chromatin Accessibility (scATAC-seq) Protocol: Mapping the regulatory landscape during neurodevelopment involves: (1) Nuclei isolation from fresh-frozen brain tissue specimens (6-13 post-conception weeks); (2) Tagmentation using Tn5 transposase to fragment accessible DNA; (3) Barcoding and sequencing on 10x Genomics platform; (4) Quality control by removing low-quality nuclei based on fragment count, transcription start site enrichment, and nucleosome signal; (5) Stratified peak calling using temporary 20kb genomic bins; (6) Dimensionality reduction with latent semantic indexing and Harmony batch correction; (7) Cluster identification via Louvain clustering, resulting in 135 distinct cell clusters from first-trimester human brain [8].

Mendelian Randomization for Causal Inference: Assessing causal relationships between ASD and comorbid conditions involves: (1) Instrument variable selection - genetic variants strongly associated with exposure; (2) Causal effect estimation using inverse-variance weighted, MR-Egger, or weighted median methods; (3) Sensitivity analyses to detect pleiotropy and heterogeneity; (4) Reverse MR to test bidirectional effects. This approach has revealed shared genetic architecture between ASD and functional somatic syndromes like IBS, multisite pain, and fatigue, though definitive causal relationships remain elusive [10].

Subtype Classification and Developmental Trajectories

Data-Driven ASD Subtypes with Distinct Genetic Profiles

Recent advances in machine learning and computational biology have enabled the identification of biologically meaningful ASD subtypes through integrated analysis of phenotypic and genotypic data. Using general finite mixture modeling on data from over 5,000 participants in the SPARK cohort, researchers have defined four clinically and biologically distinct ASD subgroups [5] [6]:

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between ASD subtypes, their genetic correlates, and developmental trajectories:

Developmental Timing and Genetic Influences Across the Lifespan

The developmental trajectories of ASD are intimately connected to genetic influences that vary across the lifespan. Research has demonstrated that the polygenic architecture of ASD can be decomposed into two modestly correlated genetic factors (r_g = 0.38) associated with different developmental profiles and diagnostic timing [7]:

- Early-Diagnosis Genetic Factor: Associated with lower social and communication abilities in early childhood, showing only moderate genetic correlations with ADHD and mental health conditions.

- Late-Diagnosis Genetic Factor: Associated with increased socioemotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence, demonstrating moderate to high positive genetic correlations with ADHD and mental health conditions [7].

These distinct genetic factors align with different developmental trajectories observed in longitudinal birth cohorts. The early childhood emergent latent trajectory is characterized by difficulties in early childhood that remain stable or modestly attenuate in adolescence. In contrast, the late childhood emergent latent trajectory shows fewer difficulties in early childhood that increase in late childhood and adolescence [7]. These trajectories are strongly associated with age at diagnosis, with the early childhood emergent trajectory predicting earlier diagnosis across multiple independent cohorts [7].

Cross-Tissue Regulatory Networks and Systems-Level Integration

The Gut-Microbiota-Immune-Brain Axis

Multi-omics approaches have revealed that ASD genetic risk factors operate through cross-tissue regulatory networks that integrate signals across biological systems. SNPs such as rs2735307 and rs989134 exhibit multi-dimensional associations, participating in gut microbiota regulation while simultaneously involving immune pathways such as T cell receptor signaling and neutrophil extracellular trap formation [1]. These loci appear to cis-regulate neurodevelopmental genes like HMGN1 and H3C9P, while also influencing epigenetic methylation modifications to regulate expression of genes such as BRWD1 and ABT1 [1].

This integrative model explains how genetic variation can coordinate dynamic balance between brain development, immune responses, and gut microbiome interactions. For instance, neuroactive metabolites produced by gut microbiota (e.g., 5-aminovaleric acid and taurine) can regulate alternative splicing of neuronal genes in the brain, leading to abnormalities in ASD risk genes like FMR1, Nrxn2, and Ank2, ultimately affecting neuronal development and synaptic plasticity [1].

Genetic Correlations with Functional Somatic Syndromes

The multi-system nature of ASD genetics is further evidenced by significant genetic correlations with functional somatic syndromes (FSS). LD score regression analyses reveal positive genetic correlations between ASD and irritable bowel syndrome (rg = 0.27), multisite pain (rg = 0.13), and fatigue (r_g = 0.33) [10]. These shared genetic architectures may partly explain the frequent co-occurrence of ASD with these somatic conditions, suggesting overlapping biological pathways that extend beyond the central nervous system.

Multi-trait analysis of GWAS (MTAG) leveraging these genetic correlations has identified novel genome-wide significant loci for ASD, including variants mapped to NEDD4L, MFHAS1, and RP11-10A14.4 [10]. Polygenic risk scores derived from these integrated analyses show stronger associations with ASD and FSS phenotypes than those derived from standard GWAS, demonstrating the enhanced discovery power of cross-trait genetic approaches [10].

The genetic architecture of ASD encompasses a complex interplay of coding variants, regulatory elements, and epigenetic factors that operate within a multi-omics framework. The field has evolved from a focus on protein-coding mutations to embrace the substantial contribution of non-coding regulatory variation, particularly in cis-regulatory elements with distinctive inheritance patterns. Advanced integrative approaches have revealed biologically distinct ASD subtypes with discrete genetic profiles and developmental trajectories, explaining part of the condition's profound heterogeneity.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: (1) Enhanced functional validation of non-coding variants using CRISPR-based screening approaches; (2) Expanded diverse ancestral representation in genetic studies to improve generalizability and discovery; (3) Longitudinal multi-omics profiling to capture dynamic developmental changes; (4) Advanced modeling of cross-tissue communication networks; and (5) Translation of genetic findings into personalized intervention strategies based on an individual's specific genetic subtype and developmental trajectory.

The integration of multi-omics data represents a paradigm shift in ASD research, moving from a fragmented view of genetic risk factors toward a systems-level understanding of interacting molecular networks. This comprehensive framework not only advances our fundamental knowledge of ASD pathogenesis but also paves the way for precision medicine approaches that account for the unique genetic architecture and developmental profile of each individual.

The microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) represents a critical bidirectional communication network integrating neural, immune, endocrine, and metabolic pathways between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. Within autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a complex neurodevelopmental condition, research increasingly implicates gut microbiota dysbiosis and altered microbial metabolomic profiles as key modulators of neurodevelopment and behavior. This whitepaper synthesizes current multi-omics evidence, detailing characteristic microbial and metabolomic signatures in ASD, their pathophysiological consequences on host neurobiology, and the emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the MGBA. The integration of genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics is providing unprecedented insights into the cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms underlying ASD heterogeneity, offering a roadmap for precision medicine and novel intervention development.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a multifactorial neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests. Its etiology involves a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, environmental influences, and biological factors [11] [12]. The global prevalence of ASD has been steadily increasing, establishing it as a significant public health priority [13] [14]. Multi-omics approaches—integrating data from genomics, metabolomics, proteomics, and microbiomics—are essential for unraveling the complex, systemic nature of ASD [1] [15]. These methodologies move beyond single-layer analysis to construct a holistic picture of the interacting molecular networks that contribute to the disease's marked heterogeneity. This whitepaper examines how multi-omics studies are elucidating the role of the MGBA, providing a mechanistic link between gut microbial ecology, host metabolism, and brain function in ASD.

Microbial Signatures: Dysbiosis in the ASD Gut

Individuals with ASD frequently exhibit significant alterations in their gut microbiota composition, a state known as dysbiosis. Metagenomic studies consistently report distinct microbial profiles compared to neurotypical individuals, though population heterogeneity can lead to variations in specific findings [11] [13] [16].

Characteristic Taxonomic Alterations

The gut microbiota in ASD is often characterized by a reduction in beneficial bacteria and an enrichment of potentially pathogenic taxa. Key changes reported across multiple studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristic Gut Microbiota Alterations in Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Taxonomic Level | Direction of Change | Specific Taxa | Potential Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Decreased | Firmicutes [13] | Reduced SCFA production |

| Phylum Ratio | Decreased | Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio [13] | Altered metabolic capacity |

| Genus | Decreased | Bifidobacterium [11] [14], Prevotella [14] | Impaired gut barrier fortification, reduced folate/B12 synthesis [13] |

| Genus | Increased | Clostridium [11] [13], Desulfovibrio [11] [13], Sutterella [13] | Increased intestinal permeability, inflammation, hydrogen sulfide production [13] |

Functional Consequences of Dysbiosis

This dysbiosis is not merely a compositional shift but has direct functional consequences. The reduction in SCFA-producing bacteria (e.g., Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae) compromises energy supply for colonocytes and weakens the intestinal barrier [13]. Conversely, an increase in bacteria like Desulfovibrio, which produces hydrogen sulfide, can exacerbate intestinal inflammation and is associated with more pronounced stereotyped behaviors [13]. Furthermore, the observed reduction in Bifidobacterium has been linked to lower serum levels of folate and vitamin B12, highlighting the microbiota's role in vitamin metabolism essential for neurological function [13].

Metabolomic Signatures: Key Microbial Metabolites in ASD

The functional output of the gut microbiota is reflected in the metabolome. Metabolomic profiling of individuals with ASD has identified distinct alterations in several classes of neuroactive and immunomodulatory microbial metabolites.

Table 2: Altered Microbial Metabolites in ASD and Their Proposed Neurophysiological Roles

| Metabolite Class | Direction of Change in ASD | Proposed Mechanism in ASD Pathophysiology | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Mixed / Altered [11] | Influence microglial maturation, synaptic plasticity, and neuroimmune responses; may disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [11] [13] | Animal models show SCFAs can induce ASD-like behaviors; human studies show altered profiles [11] |

| Tryptophan Metabolites (Kynurenate) | Significantly Lower [17] | Loss of neuroprotective signaling; associated with altered insular and cingulate cortex activity, linked to ASD symptom severity and sensory sensitivities [17] | Human fMRI-metabolomics study found correlations with brain activity and behavior [17] |

| Other Tryptophan Derivatives (e.g., Indolelactate, Indolepropionate) | Lower (sensitivity analysis) [17] | Associated with increased activity in brain regions for interoceptive and disgust processing; may influence ASD severity via brain mediation [17] | Mediation analysis showed brain activity mediates metabolite-behavior relationships [17] |

Integrated Multi-Omics and Pathophysiological Mechanisms

The integration of omics data reveals how microbial and metabolomic signatures converge to drive core pathophysiological mechanisms in ASD through the MGBA.

Communication Pathways of the MGBA

The MGBA facilitates gut-brain communication through several interconnected modules [11] [12]:

- Neural Pathway: The vagus nerve serves as a direct, rapid conduit for afferent signals from the gut to the brain. Evidence from animal models indicates that the behavioral benefits of microbiota-targeted therapies are abolished after vagotomy [13].

- Immune Pathway: Dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut") allow bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to translocate, triggering systemic inflammation. This can compromise the blood-brain barrier, leading to microglial activation and neuroinflammation, a well-documented feature in ASD [11] [12] [14].

- Neuroendocrine Pathway: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is influenced by microbial metabolites. Dysregulation of this stress axis is common in ASD and can further alter gut permeability and microbiota composition, creating a vicious cycle [11] [13].

- Metabolic Pathway: Microbial metabolites like SCFAs, tryptophan derivatives, and bile acids act as signaling molecules that can enter circulation, cross the BBB, and directly influence brain function, gene expression, and synaptic plasticity [11] [17].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and their interconnections within the MGBA in the context of ASD.

Figure 1. MGBA signaling pathways in ASD pathophysiology.

Cross-Tissue Genetic Regulation

Multi-omics studies are uncovering how genetic risk factors in ASD exert cross-tissue effects, coordinating the dynamic balance between brain neural development, peripheral immune responses, and gut microbiota interactions. A 2025 multi-omics meta-analysis identified specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (e.g., rs2735307, rs989134) that participate in gut microbiota regulation while simultaneously cis-regulating neurodevelopmental genes (HMGN1, H3C9P) and influencing immune pathways such as T cell receptor signaling [1]. This provides genetic evidence for a "gut microbiota-immune-brain axis," where genetic variants act as core drivers of a systemic pathological network in ASD.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for MGBA-ASD Research

To investigate the MGBA in ASD, researchers employ a combination of clinical assessment, multi-omics profiling, and mechanistic studies. Below is a detailed workflow for an integrated human study linking gut metabolites to brain function.

Integrated Human fMRI and Fecal Metabolomics Protocol

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that identified associations between tryptophan metabolites, brain activity, and ASD symptomatology [17].

Objective: To determine associations between fecal levels of specific tryptophan-related gut metabolites, task-based brain activity, and behavioral scores in children with ASD.

Participant Cohort: - Groups: ASD children (n=43) and neurotypical (NT) controls (n=41), aged 8-17 years. - Key Considerations: Groups should be matched for age and sex. Comprehensive characterization includes ADOS scores for ASD severity, IQ testing, and assessments for GI symptoms, sensory sensitivities, and disgust propensity. Diet should be recorded and controlled for in analyses [17].

Procedure:

- Biospecimen Collection and Metabolomic Profiling:

- Collect fecal samples from participants and immediately freeze at -80°C.

- Perform targeted metabolomic profiling (e.g., using LC-MS) focused on the tryptophan/serotonin pathway, quantifying metabolites such as kynurenate (KA), indolelactate, tryptophan betaine, and indolepropionate.

- Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI):

- Acquire task-based fMRI data using paradigms that probe socio-emotional and sensory processing. Examples include: - Facial Expression Processing: Viewing and identifying emotions from faces. - Disgust Processing: Viewing images of disgusting foods or facial expressions of disgust. - Somatosensory Processing: Experiencing social and non-social touch.

- Preprocess fMRI data (realignment, normalization, smoothing).

- Define Regions of Interest (ROIs) based on prior ASD literature, focusing on regions like the insular subregions (anterior, mid, posterior), mid-cingulate cortex (MCC), pregenual anterior cingulate, and primary somatosensory cortex (S1).

- Statistical Integration and Mediation Analysis:

- Use general linear models (GLMs) to assess between-group (ASD vs. NT) differences in metabolite levels, controlling for covariates like age, sex, and BMI.

- Within the ASD group, use GLMs to test for correlations between metabolite abundance and evoked brain activity in the pre-defined ROIs during each task.

- Perform mediation analysis to test the hypothesis that brain activity in specific ROIs (e.g., mid-insula) statistically mediates the relationship between metabolite levels (e.g., indolelactate) and ASD behavioral scores (e.g., disgust sensitivity) [17].

The workflow for this multi-modal experiment is summarized in the following diagram.

Figure 2. Integrated fMRI-metabolomics workflow.

Animal Model Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics Protocol

This protocol outlines a multi-omics approach to investigate molecular mechanisms in ASD mouse models, focusing on global proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiling of brain tissue [18].

Objective: To identify shared differentially expressed proteins and phosphorylation sites in the cortex of validated ASD mouse models (Shank3Δ4–22 and Cntnap2-/-) to uncover convergent molecular pathways.

Animals: - Models: Shank3Δ4–22 and Cntnap2-/- mice and their wild-type littermate controls. - Housing: Standard conditions, with all procedures approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection and Protein Extraction:

- Sacrifice mice and dissect cortical brain regions. Snap-freeze tissue in liquid nitrogen.

- Homogenize tissue in lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Extract total protein and determine concentration.

- Global Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics:

- Protein Digestion: Digest proteins with trypsin.

- Phosphopeptide Enrichment: For phosphoproteomics, enrich phosphopeptides from the digested peptide mixture using TiO2 or IMAC beads.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze both global peptides and enriched phosphopeptides via liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Data Processing: Identify and quantify proteins and phosphopeptides using bioinformatic software (e.g., MaxQuant). For phosphoproteomics, localize phosphorylation sites to specific serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues.

- Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis:

- Perform differential expression analysis to identify proteins and phosphosites that are significantly altered in each mouse model compared to its control.

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., KEGG, GO) on the differentially expressed proteins and phosphorylated proteins to identify affected biological processes (e.g., autophagy, mTOR signaling) [18].

- Focus on shared molecular changes between the two different ASD models to highlight core pathophysiological mechanisms.

The following table details essential reagents, tools, and databases critical for conducting multi-omics research on the MGBA in ASD.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MGBA and Multi-Omics ASD Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ASD Animal Models(e.g., Shank3Δ4–22, Cntnap2-/-) | Genetically engineered models to study specific ASD-risk gene pathways and perform mechanistic experiments, including proteomics and intervention studies [18]. | Investigating convergent autophagy-related protein phosphorylation in the cortex [18]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | High-sensitivity analytical platform for untargeted and targeted metabolomic and proteomic profiling from biological samples (feces, blood, brain tissue) [17] [18]. | Quantifying fecal tryptophan metabolites [17] or cortical phosphopeptides [18]. |

| fMRI Scanners & Task Paradigms | Non-invasive in vivo imaging to link metabolic findings with functional brain activity in regions like the insula and cingulate cortex [17]. | Associating kynurenate levels with altered brain activity during disgust processing [17]. |

| Bioinformatic Databases & Tools(e.g., SFARI Gene database, BERTopic, HunFlair) | For genetic data integration, literature mining, and named entity recognition from scientific texts to identify trends and biomarkers [15]. | Mining PubMed for multi-omics trends in ASD; extracting gene and disease entities from abstracts [15]. |

| Mendelian Randomization (MR) & SMR | Statistical genetic methods to infer causality between exposure (e.g., gut microbiota) and outcome (e.g., ASD risk) using GWAS data [12] [1]. | Testing for causal effects of gut microbial abundance on ASD and identifying pleiotropic genetic loci [1]. |

Emerging Microbiome-Targeted Therapeutic Interventions

Targeting the MGBA presents a promising avenue for adjunctive therapies in ASD. Current interventions aim to restore eubiosis, correct metabolomic imbalances, and alleviate both GI and behavioral symptoms.

Table 4: Microbiome-Targeted Interventions in ASD

| Intervention | Proposed Mechanism | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Probiotics & Prebiotics | Restore beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus), fortify gut barrier, reduce inflammation [11] [16]. | Modest improvements in GI symptoms (constipation, diarrhea) and secondary behavioral benefits [11] [14]. |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | Comprehensively reshape the gut microbial community by introducing a diverse, healthy donor microbiota [11]. | Open-label trials report long-term improvements in both GI dysfunction and core ASD symptoms [11] [16]. |

| Dietary Modulation(e.g., high-fiber, gluten-free/casein-free) | Alter substrate availability for gut microbes, thereby modulating microbial composition and metabolite production [11] [13]. | May improve GI and behavioral outcomes, though evidence is variable and influenced by dietary selectivity common in ASD [11] [13]. |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Vancomycin) | Target specific bacterial overgrowth, such as Clostridia [11]. | Can lead to temporary alleviation of ASD symptoms, but effects are often not sustained post-treatment [11]. |

Multi-omics research has firmly established that gut-brain axis dysregulation, characterized by distinct microbial and metabolomic signatures, is a core component of ASD pathophysiology. The integration of genomic, metabolomic, and proteomic data is illuminating the complex, cross-tissue networks that connect genetic risk, gut dysbiosis, immune activation, and altered brain development and function. Future research must prioritize large-scale, longitudinal studies that can establish causality and account for the profound heterogeneity of ASD. Furthermore, the development of standardized protocols for multi-omics integration and the application of advanced computational models will be crucial for translating these findings into clinically actionable insights. Targeting the MGBA through precision microbiome interventions holds significant promise for developing novel, adjunctive therapies to improve the quality of life for individuals with ASD.

Abstract Recent multi-omics studies have fundamentally advanced our understanding of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by revealing specific immune dysregulation pathways. This whitepaper synthesizes cutting-edge research demonstrating that dysregulated TNF-related signaling pathways in peripheral immune cells are a key feature of ASD pathophysiology. Through integrative transcriptomic, proteomic, and single-cell RNA-seq analyses, studies have identified distinct immune signatures, including upregulated TNF superfamily members and altered T cell subsets, offering novel insights for biomarker discovery and targeted immunomodulatory therapies.

Multi-Omics Evidence of Immune Dysregulation in ASD

The application of multi-omics approaches has provided unprecedented resolution of the peripheral immune landscape in ASD, moving beyond simple cytokine profiling to reveal complex, cell-type-specific dysregulation.

Table 1: Key Immune Alterations in ASD Identified via Multi-Omics Studies

| Omics Layer | Key Finding | Biological Material | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | Differential expression of 50 immune-related genes; JAK3, CUL2, CARD11 correlated with symptom severity [19]. | PBMCs | Identifies potential genetic regulators of immune dysfunction linked to clinical outcomes. |

| Proteomics | Upregulated plasma levels of TNFSF10 (TRAIL), TNFSF11 (RANKL), and TNFSF12 (TWEAK) [19]. | Plasma | Confirms activation of TNF-related pathways at the protein level, suggesting accessible biomarkers. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | B cells, CD4+ T cells, and NK cells identified as primary sources of upregulated TNFSF signaling [19]. | PBMCs | Pinpoints specific cellular contributors to immune dysregulation. |

| Metaproteomics & Metabolomics | Altered gut microbiota; identified microbial metaproteins and host proteins (e.g., KLK1, TTR) linked to neuroinflammation [20]. | Stool microbiota & host proteome | Connects gut-immune-brain axis to neurodevelopmental deficits in ASD. |

| Neuroimaging | Elevated TSPO protein in frontal and temporal skull, correlated with peripheral C-reactive protein [21]. | In vivo PET-MRI | Provides in vivo evidence of neuroimmune involvement, linking peripheral and central immunity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Multi-Omic Profiling of Peripheral Blood

This integrated protocol, derived from a cohort of young Arab children with ASD, details how to identify dysregulated immune pathways from blood samples [19].

2.1.1. Sample Collection and Processing

- Blood Draw: Collect blood into EDTA-containing anti-coagulant tubes.

- PBMC Isolation: Within 2 hours of draw, layer blood over Histopaque-1077 and centrifuge at 400 × g for 30 minutes (acceleration 3, zero brake). Collect PBMCs from the middle fraction and plasma from the upper layer.

- Cell Wash & Storage: Wash PBMCs twice with 1x PBS, centrifuge at 400 × g for 10 minutes, and cryopreserve at -150°C. Aliquot plasma after a 1800 × g centrifugation for 15 minutes and store at -80°C.

2.1.2. Transcriptomic Profiling (NanoString nCounter)

- RNA Isolation: Use the Invitrogen Purelink RNA kit to extract RNA from PBMCs. Verify RNA quality via NanoDrop (260/280 ratio ~1.7-2.0).

- Hybridization: Use the nCounter Human Immune Exhaustion panel (785 genes). For each reaction, use 100 ng of RNA and hybridize for 16 hours.

- Data Acquisition & Analysis: Run samples on the nCounter PrepStation (high-sensitivity mode) and Digital Analyzer. Perform QC, normalization, and differential expression analysis (absolute fold change >1.25, FDR-adjusted p < 0.05) on the Rosalind platform.

2.1.3. Proteomic Analysis (Plasma)

- While the specific proteomic platform is not detailed in the results, the study's findings of disrupted TNF signaling and upregulated TNFSF members (TRAIL, RANKL, TWEAK) in plasma would typically be validated using technologies like multiplex immunoassays (Luminex) or mass spectrometry-based proteomics.

2.1.4. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq)

- Cell Preparation: Generate single-cell suspensions from PBMCs.

- Library Construction: Use the 10x Genomics Chromium Single-cell 3' Reagent v3 kit for barcoding and library preparation according to manufacturer specifications.

- Sequencing & Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence libraries on an Illumina HiSeq system. Process raw data with Cell Ranger for alignment. Subsequent analysis in R (Seurat package v5.0.1) includes: quality control (filtering doublets, low-UMI cells, high mitochondrial gene percentage), normalization, PCA, clustering (

FindNeighborsandFindClusters), and cell type annotation using canonical markers.

Low-Dose IL-2 (LdIL-2) Immunotherapy in BTBR Mice

This protocol outlines a novel immunotherapeutic approach targeting T cell imbalances, demonstrating a causal link between immune modulation and ASD-like behavior improvement [22].

2.2.1. Animal Model and Treatment

- Subjects: Use male BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice, aged 6-8 weeks, as an ASD model. Use C57BL/6 mice as controls.

- LdIL-2 Administration: Reconstitute recombinant human IL-2 in sterile normal saline. Administer via subcutaneous injection at a dose of 30,000 IU per course. Treat for four courses (7 days per course) with a one-day interval between courses. Control groups receive saline.

- Treg Depletion (For Mechanistic Study): To deplete Treg cells, intraperitoneally inject 200 μg of anti-mouse CD25 antibody (PC61) one day before and on days 14 and 28 after starting LdIL-2 treatment.

2.2.2. Behavioral Assessments

- Three-Chamber Social Test: Assess sociability and preference for social novelty. Calculate a Social Approach Preference Index and a Social Novelty Preference Index.

- Self-Grooming Test: Record cumulative grooming time over 10 minutes after a 10-minute habituation as a measure of repetitive behavior.

- Marble-Burying Test: Place a mouse in a cage with 20 marbles for 10 minutes; count marbles buried (>2/3 covered) as another measure of repetitive/digging behavior.

- Open Field Test: Record total distance moved and time spent in the center area over 10 minutes to assess general locomotion and anxiety-like behavior.

2.2.3. Immune Phenotyping

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze peripheral blood for T helper (Th) cell and regulatory T (Treg) cell populations to determine Th/Treg ratios. In the central nervous system, analyze microglia for M1/M2 polarization states.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflow

The following diagrams visualize the core signaling pathways implicated in ASD and the integrated workflow of multi-omics analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for Investigating Immune Pathways in ASD

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Catalog Number / Source |

|---|---|---|

| nCounter Human Immune Exhaustion Panel | Targeted transcriptomic profiling of 785 immune-related genes from PBMC RNA. | #XT-H-EXHAUST-12 (NanoString) [19] |

| Histopaque-1077 | Density gradient medium for the isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). | #10771 (Sigma-Aldrich) [19] |

| Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits | Library preparation for single-cell RNA sequencing to resolve cellular heterogeneity. | (10x Genomics) [19] |

| Recombinant Human IL-2 | For investigating the therapeutic effects of low-dose IL-2 on Treg cell populations in vivo. | (Various, e.g., Shandong Quangang Pharm.) [22] |

| Anti-Mouse CD25 Antibody (PC61) | Depletion of CD25+ Treg cells for mechanistic validation studies in mouse models. | (BioLegend) [22] |

| BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J Mice | A commonly used murine model exhibiting core ASD-like behaviors and immune dysregulation. | The Jackson Laboratory [22] |

| Seurat R Package | A comprehensive open-source software platform for single-cell genomics data analysis and visualization. | [19] |

| CellChat R Package | Tool for inference and analysis of cell-cell communication networks from scRNA-seq data. | [23] |

The convergence of evidence from multiple omics layers solidifies the role of TNF-related signaling pathways as a core component of peripheral immune dysregulation in ASD. The identification of specific cell subsets (NK, T cells) and molecules (TRAIL, RANKL, TWEAK) provides a new level of precision for understanding ASD pathophysiology. Future research must focus on longitudinal studies to determine if these immune signatures are stable over time and to clarify their causal relationship with core ASD symptoms. The promising results from LdIL-2 therapy in preclinical models [22] highlight the potential of immunomodulation and pave the way for targeted clinical interventions aimed at restoring immune homeostasis in ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a complex group of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by deficits in social communication and restrictive, repetitive behaviors. The intricate molecular pathogenesis of ASD has remained poorly understood due to etiological heterogeneity and the predominance of idiopathic cases. Recent advances in multi-omics technologies have enabled unprecedented investigation of the proteomic and phosphoproteomic landscapes underlying ASD pathophysiology. This whitepaper synthesizes current research revealing how coordinated dysregulation of synaptic machinery and autophagy pathways contributes to ASD pathogenesis. Evidence from global proteomic, phosphoproteomic, and synaptomic analyses across multiple model systems and human postmortem brains consistently identifies disruption in postsynaptic density proteins, glutamate receptor signaling, and autophagic flux. Particularly compelling are findings that altered phosphorylation patterns in autophagy-related proteins impair degradative pathways, while synaptic proteomic signatures reveal attenuated maturation of postsynaptic complexes. Integration of these datasets within a multi-omics framework provides novel insights into convergent molecular pathways and identifies potential therapeutic targets for modulating the synaptopathy and impaired proteostasis characteristic of ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder affects approximately 1 in 36 children, imposing substantial personal, family, and societal challenges [18]. The genetic architecture of ASD is extraordinarily complex, with common inherited variants and rare de novo mutations working together to confer genetic risk [24]. Despite significant advances in identifying genetic risk factors, the vast majority of ASD cases remain idiopathic without definitive etiological diagnosis [25]. This heterogeneity has complicated efforts to unravel the underlying pathobiology, necessitating approaches that can identify convergent molecular pathways across diverse ASD forms.

Multi-omics approaches integrating genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and phosphoproteomics have emerged as powerful strategies for understanding complex neurodevelopmental disorders [26] [27]. Proteomic analyses are particularly valuable as they reflect the functional effectors of cellular processes and are "closer" to phenotypic expression than genomic or transcriptomic analyses [25]. The integration of phosphoproteomic data further enhances understanding of post-translational regulation mechanisms that rapidly modulate protein function in response to signaling events.

This whitepaper examines how integrated proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses have illuminated the interconnected roles of synaptic and autophagy mechanisms in ASD pathophysiology. We focus specifically on findings from global proteomic surveys of brain regions, synaptosomal preparations, phosphoproteomic investigations of signaling networks, and the emerging evidence implicating impaired autophagic flux in ASD pathogenesis.

Synaptic Proteomic Alterations in ASD

Postsynaptic Density Proteomic Signatures

Analyses of the synaptic proteome have revealed consistent alterations in postsynaptic density (PSD) proteins across multiple ASD models and human brain tissues. A quantitative proteomic study of synaptosomes from dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 9) demonstrated significant downregulation of PSD-related proteins in children with idiopathic ASD compared to age-matched controls [28]. The affected proteins included key glutamatergic receptors (AMPA and NMDA receptors), scaffolding proteins (SHANK1-3, HOMER1, DLG4/PSD-95), and signaling molecules (CaMK2α) essential for synaptic maturation and function (Table 1).

Table 1: Synaptic Proteomic Alterations in ASD Brain Tissues

| Protein Category | Specific Proteins Altered | Direction of Change | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate Receptors | AMPA receptors, NMDA receptors, GRM3 | Downregulated | Impaired excitatory synaptic transmission |

| Scaffolding Proteins | SHANK1-3, DLG4, HOMER1 | Downregulated | Disrupted PSD organization & signaling |

| Cell Adhesion | NRXN1, NLGN2 | Downregulated | Impaired trans-synaptic signaling |

| Cytoskeletal | Drebrin1, ARHGAP32, Dock9 | Downregulated | Altered spine morphology & dynamics |

| Presynaptic | SYP, VAMP2, BSN | Upregulated | Compensatory presynaptic changes |

Notably, these PSD-related alterations were more pronounced in children with ASD than in adults, suggesting a developmental component to synaptic abnormalities in ASD [28]. Network analyses of these proteomic changes highlighted abnormalities in glutamate receptor signaling and Rho GTPase pathways, both critical for synaptic plasticity and cytoskeletal reorganization in developing neurons.

Regional Proteomic Patterns in ASD Brain

Comparative proteomic profiling of different brain regions has revealed both shared and region-specific alterations in ASD. Analysis of Brodmann area 19 (occipital cortex) and posterior inferior cerebellum demonstrated distinctive protein expression profiles between ASD and controls for both regions [25]. While the two brain regions maintained their proteomic differentiation in ASD, pathway analyses revealed shared dysregulation of glutamate receptor signaling and glutathione-mediated detoxification in both regions.

Regional specificity was also evident, with BA19 showing particular enrichment in Sertoli cell signaling pathways (involved in neurodevelopmental processes), while cerebellum exhibited disruptions in fatty acid oxidation and branched-chain amino acid metabolism [25]. Protein interaction network analyses identified DLG4 (PSD-95) as a major hub protein in BA19, while MAPT (tau) served as a central hub in cerebellar networks, indicating region-specific vulnerabilities in ASD pathophysiology.

Multi-Model Comparative Synaptic Proteomics

A comparative analysis of hippocampal synaptic proteomes across five distinct ASD mouse models—Fmr1 knockout ( Fragile X syndrome), Cntnap2 knockout (cortical dysplasia focal epilepsy syndrome), Pten haploinsufficiency (PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome), Anks1b haploinsufficiency (ANKS1B syndrome), and BTBR+ (idiopathic autism)—revealed several common altered molecular pathways at the synapse [24]. These included consistent changes in oxidative phosphorylation and Rho family small GTPase signaling, suggesting convergent pathogenic mechanisms despite diverse genetic origins.

Similarity analyses revealed that the models could be clustered according to their synaptic proteomic profiles, potentially forming the basis for molecular subtypes that explain genetic heterogeneity in ASD despite common clinical presentations [24]. This approach demonstrates how proteomic convergence across models can identify central pathways for therapeutic targeting.

Autophagy Dysregulation in ASD

Autophagy-Related Protein Expression and Phosphorylation

A multi-omics investigation using Shank3Δ4-22 and Cntnap2-/- mouse models revealed significant dysregulation of autophagy pathways in ASD [18] [29]. Global proteomic analyses identified differential expression of proteins impacting postsynaptic components and synaptic function, including key pathways such as mTOR signaling, a critical regulator of autophagy. Phosphoproteomic approaches further revealed unique phosphorylation sites in several autophagy-related proteins, including ULK2, RB1CC1, ATG16L1, and ATG9, suggesting that altered phosphorylation patterns contribute to impaired autophagic flux in ASD.

Table 2: Autophagy-Related Molecular Changes in ASD Models

| Molecule | Change in ASD | Functional Role in Autophagy | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC3-II | Elevated | Autophagosome membrane marker | SH-SY5Y SHANK3 KO [18] |

| p62/SQSTM1 | Elevated | Autophagy substrate receptor | SH-SY5Y SHANK3 KO [18] |

| LAMP1 | Reduced | Lysosomal membrane protein | SH-SY5Y SHANK3 KO [18] |

| ULK2 | Altered phosphorylation | Autophagy initiation kinase | Cortical proteomics [18] |

| ATG16L1 | Altered phosphorylation | Autophagosome elongation | Cortical proteomics [18] |

| nitric oxide | Elevated | Impairs autophagosome-lysosome fusion | Shank3Δ4-22, Cntnap2-/- [18] |

Functional validation in SH-SY5Y cells with SHANK3 deletion showed elevated levels of LC3-II and p62, indicating autophagosome accumulation alongside reduced LAMP1, suggesting impaired autophagosome-lysosome fusion rather than defective autophagy initiation [18]. This pattern points specifically to disrupted autophagic flux in ASD models, where the autophagy process initiates but cannot reach completion.

Nitric Oxide Signaling and Autophagy Disruption

The multi-omics study highlighted the involvement of reactive nitrogen species and nitric oxide (NO) in autophagy disruption [18]. Importantly, inhibition of neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) by 7-nitroindazole (7-NI) normalized autophagy marker levels in both SH-SY5Y cells and primary cultured neurons. This finding connected previously observed elevated NO levels in ASD mouse models with the impaired autophagy mechanisms, suggesting a potential signaling pathway through which synaptic dysfunction might impair cellular homeostasis.

The therapeutic relevance of these findings was strengthened by previous observations that nNOS inhibition improved synaptic and behavioral phenotypes in Shank3Δ4-22 and Cntnap2-/- mouse models [18], suggesting a mechanistic link between NO signaling, autophagy disruption, and behavioral manifestations of ASD.

mTOR Signaling and Autophagy Regulation

Beyond the direct evidence from multi-omics studies, considerable research has implicated mTOR signaling in autophagy dysregulation in ASD [30]. The mTOR pathway serves as a critical regulator of autophagy initiation, with hyperactive mTOR signaling suppressing autophagic activity. In several ASD models, including Pten and Tsc2 mutants, constitutive mTOR activation associates with autophagy deficiency, suggesting this pathway may represent a convergent node integrating various ASD-related genetic insults.

The relationship between mTOR and autophagy appears particularly relevant for synaptic development and function, as mTOR regulates protein synthesis at synapses and autophagy helps maintain synaptic protein homeostasis by degrading damaged organelles and proteins [30]. Dysregulation of this balance could contribute to the synaptic abnormalities observed in ASD.

Experimental Methodologies

Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Workflows

Current proteomic investigations of ASD typically employ sophisticated mass spectrometry-based approaches. For global proteomic profiling, label-free HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry has been successfully used to characterize proteomes of brain regions from idiopathic ASD cases and matched controls [25]. This approach enables unbiased relative quantification of thousands of proteins across multiple samples.

More recently, isobaric tandem mass tagging (TMT) with HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry has been applied to compare synaptic proteomes across multiple ASD models [24]. This method allows multiplexed analysis of up to 16 samples simultaneously, improving quantification accuracy and throughput. For synaptosomal studies, subcellular fractionation techniques are employed to isolate synaptic fractions before proteomic analysis [28].

Phosphoproteomic analyses build upon these approaches by incorporating phosphopeptide enrichment steps, typically using titanium dioxide or immobilized metal affinity chromatography, prior to LC-MS/MS analysis [18]. This enables identification and quantification of phosphorylation sites across the proteome, revealing signaling network alterations in ASD.

Model Systems and Validation

ASD research employs diverse model systems, each with distinct advantages. Genetic mouse models including Shank3Δ4-22, Cntnap2-/-, Fmr1 knockout, and Pten haploinsufficiency recapitulate various aspects of ASD pathophysiology and allow proteomic investigation of specific genetic alterations [18] [24]. Human postmortem brain studies provide direct evidence of proteomic changes in ASD but face challenges regarding sample availability, postmortem intervals, and comorbid conditions [25] [28].

Cellular models, such as SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells with SHANK3 deletion, enable mechanistic studies and pharmacological interventions [18]. Primary neuronal cultures further facilitate investigation of cell-autonomous mechanisms in a relevant cellular context.

Functional validation of proteomic findings typically includes western blotting for specific proteins of interest, immunohistochemical localization, and behavioral assessment in model systems following pharmacological or genetic interventions targeting identified pathways [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Synaptic and Autophagy Studies in ASD

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | LC-3A/B, p62, LAMP1, β-actin | Autophagy flux assessment | Western blot, IHC [18] |

| Mouse Models | Shank3Δ4-22, Cntnap2-/-, Fmr1 KO, Pten+/- | Pathway analysis & therapeutic testing | Multimodel comparisons [18] [24] |

| Proteomic Reagents | TMTpro 16plex Label Reagent, Triton X-100 | Protein quantification & fractionation | Synaptosomal preparation [28] |

| Signaling Inhibitors | 7-Nitroindazole (7-NI), rapamycin | Pathway modulation | nNOS & mTOR inhibition [18] [30] |

| Cell Lines | SH-SY5Y SHANK3 KO | Mechanistic studies | Autophagy flux assays [18] |

Integrated Pathway Analysis

Integrated Pathway in ASD Pathophysiology

The integrated pathway diagram illustrates how diverse ASD genetic risk factors converge on synaptic dysfunction and mTOR signaling dysregulation, which collectively contribute to autophagy disruption through elevated nitric oxide and direct signaling impacts. These alterations in cellular homeostasis pathways, particularly reflected in phosphoproteomic changes to autophagy machinery, ultimately contribute to behavioral phenotypes characteristic of ASD.

Proteomic and phosphoproteomic investigations have substantially advanced our understanding of synaptic and autophagy mechanisms in ASD pathophysiology. The consistent observation of postsynaptic density protein alterations across multiple models and human brain tissues supports the concept of ASD as a synaptopathy characterized by impaired maturation of excitatory synapses. Simultaneously, multi-omics approaches have revealed extensive dysregulation of autophagy pathways, particularly through altered phosphorylation of autophagy-related proteins that disrupt autophagic flux.

The integration of these findings within a multi-omics framework highlights the interconnectedness of synaptic and autophagy mechanisms, with synaptic activity modulating autophagy through NO signaling and mTOR pathways, while autophagy in turn regulates synaptic protein homeostasis. These advances not only provide insights into ASD pathogenesis but also identify potential therapeutic targets, including nNOS inhibition and mTOR modulation, that may address core biological processes in ASD beyond symptomatic treatment.

Future research directions should include longitudinal proteomic studies to track developmental changes, cell-type-specific proteomic analyses to resolve cellular heterogeneity, and integration of proteomic findings with genomic and transcriptomic datasets to establish complete molecular pathways from genetic risk to functional impairment. Such approaches promise to further elucidate the complex interplay between synaptic and autophagy mechanisms in ASD, ultimately facilitating targeted therapeutic development for this heterogeneous disorder.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a paradigm for complex, heterogeneous neurodevelopmental conditions affecting millions worldwide. This heterogeneity manifests through vast differences in symptom presentation, developmental trajectories, co-occurring conditions, and treatment responses, creating significant challenges for diagnosis, mechanistic understanding, and therapeutic development [31] [6]. The inherent limitations of purely behavior-based diagnostic schemas have driven the emergence of molecular subtyping as an essential precision medicine approach. By integrating multi-omics technologies—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics—with deep phenotypic data, researchers can deconvolve this heterogeneity into biologically distinct subtypes [31]. This transition from phenomenological to biological classification represents a transformative shift in neurodevelopmental disorder research, enabling the mapping of diverse clinical presentations to distinct genetic architectures, molecular pathways, and cellular mechanisms. The resulting subtypes provide a powerful framework for elucidating disease etiology, identifying biomarkers, and ultimately guiding targeted therapeutic interventions [32] [6].

Core Methodological Frameworks for Molecular Subtyping

Molecular subtyping employs sophisticated computational and statistical frameworks to identify coherent subgroups within seemingly heterogeneous populations. The fundamental challenge lies in the "large p, small n" scenario, where the number of molecular features vastly exceeds the number of samples, increasing the risk of overfitting and spurious associations [31]. Several core methodologies have been developed to address this challenge.

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Robust preprocessing is critical for distinguishing biological signal from technical noise. Platform-specific normalization methods are essential: RNA-seq data often utilizes DESeq2's median-of-ratios or edgeR's TMM methods, while proteomics data typically relies on quantile normalization or variance-stabilizing transformations [31]. Batch effect correction methods such as ComBat, Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA), and mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) are crucial for mitigating technical artifacts introduced by different sample handling, reagents, or instrumentation [31]. Failure to appropriately address these technical covariates can confound downstream subtype identification.

Subtyping Algorithms and Integration Techniques

Table 1: Core Computational Methods for Molecular Subtyping

| Method Category | Specific Algorithms | Key Principles | Applications in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based Integration | Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) | Constructs patient similarity networks from multiple data modalities and fuses them to identify clusters | Used to integrate clinical and transcriptomic data, identifying clusters of toddlers with distinct ASD severity [32] |

| Matrix Factorization | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA) | Discovers latent factors that capture shared and specific sources of variability across multiple omics layers | Identifies convergent molecular signatures across transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data [31] |

| Centroid-Based Classification | PAM50 (with subgroup-specific centering) | Classifies samples based on correlation to predefined subtype centroids; requires careful normalization | Originally for breast cancer; demonstrates importance of cohort-aware normalization for accurate subtyping [33] |

| Unsupervised Clustering | Consensus Clustering | Determines stable clusters through resampling and aggregation; validates cluster robustness | Applied to proteomics data for identifying molecular prognosis subtypes of IgAN; generalizable to ASD [34] |

Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting complex molecular subtypes. Tools such as t-SNE and UMAP provide dimensionality reduction for visualizing high-dimensional data in two or three dimensions. For network-based visualization, platforms like Cytoscape enable the mapping of molecular interaction networks and biological pathways, while Gephi offers powerful graph visualization capabilities [35]. These tools facilitate the exploration of relationships between identified subtypes and their underlying molecular features.

Molecular Subtyping in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Key Findings

Recent large-scale studies have demonstrated the power of molecular subtyping to dissect heterogeneity in ASD, revealing biologically distinct subgroups with different clinical presentations and genetic architectures.

Clinico-Biological Subtypes of ASD

A landmark study analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism using a "person-centered" approach that considered over 230 traits [6]. These subtypes exhibit distinct developmental trajectories, co-occurring conditions, and genetic profiles.

Table 2: Clinico-Biological ASD Subtypes Identified Through Integrated Analysis

| Subtype | Prevalence | Clinical Characteristics | Genetic Features | Developmental Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | ~37% | Core autism traits with co-occurring ADHD, anxiety, depression | Damaging de novo mutations in genes active later in childhood | Typical milestone achievement; later diagnosis |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | ~19% | Developmental delays (walking, talking) without significant psychiatric comorbidities | Elevated rare inherited genetic variants | Delayed early milestone achievement |

| Moderate Challenges | ~34% | Milder core autism symptoms, few co-occurring conditions | — | Typical milestone achievement |

| Broadly Affected | ~10% | Severe, wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays and multiple psychiatric conditions | Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations | Delayed milestones with significant ongoing impairments |

Biological Pathways Underlying ASD Subtypes

Transcriptomic analyses have revealed distinct dysregulated pathways across ASD subtypes. A study of 363 toddlers identified seven subtype-specific dysregulated gene pathways in profound autism controlling embryonic proliferation, differentiation, neurogenesis, and DNA repair [32]. Additionally, seventeen ASD subtype-common dysregulated pathways showed a severity gradient, with the greatest dysregulation in profound autism and least in mild forms [32]. Key pathways include:

- PI3K-AKT signaling: Regulates cell growth, proliferation, and survival

- RAS-ERK signaling: Controls multiple prenatal neurodevelopmental processes

- Wnt signaling: Influences cell fate determination and patterning

- Mitochondrial and immune pathways: Emerging as convergent mechanisms across subtypes [31] [32]

Figure 1: Logical flow from genetic variation through molecular pathways to ASD clinical subtypes. Pathway dysregulation mediates the relationship between genetic risk and phenotypic presentation.

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Subtyping

Implementing robust molecular subtyping requires meticulous experimental design and execution. The following protocols outline key methodologies for successful subtype identification and validation.

Protocol for Multi-Omics Subtype Identification

This protocol adapts established workflows for identifying molecular subtypes using multi-omics data [31] [34].

Step 1: Cohort Selection and Sample Preparation

- Recruit well-characterized cohort with deep phenotyping (clinical, developmental, behavioral measures)

- Collect appropriate biospecimens (blood, brain tissue, iPSC-derived neurons) based on research question

- For transcriptomics: extract high-quality RNA (RIN > 8), prepare sequencing libraries

- For proteomics: perform protein extraction, digestion, and labeling if using multiplexed approaches

Step 2: Data Generation and Quality Control

- RNA-seq: Sequence with minimum 30M reads per sample, assess quality metrics (Q scores, GC content)

- Proteomics: Use LC-MS/MS with appropriate replication, monitor retention time stability

- QC Steps: Identify outliers via PCA, assess sample integrity metrics, verify expected relationships (e.g., sex chromosomes)

Step 3: Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Perform platform-specific normalization: DESeq2 for RNA-seq, variance-stabilizing normalization for proteomics

- Apply batch correction using ComBat or SVA when multiple batches are present

- Address known confounders (age, sex, ancestry) through regression or inclusion in models

Step 4: Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

- Filter lowly expressed genes/proteins (e.g., >10 counts in >10% samples for RNA-seq)

- Select highly variable features using mean-variance relationships

- Apply UMAP or t-SNE for visualization and initial cluster assessment

Step 5: Subtype Identification

- Employ consensus clustering to determine stable clusters

- Use SNF to integrate multiple data types (clinical and molecular)

- Validate clusters using internal metrics (silhouette width, within-cluster sum of squares)

Step 6: Subtype Characterization and Validation

- Identify differentially expressed features between subtypes (DESeq2, limma)

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (GSEA, GSVA) on subtype-specific markers

- Validate subtypes in independent cohort using classifier transfer approaches

Protocol for Bioinformatics Analysis of Subtypes

This protocol details the computational analysis of molecular subtypes once identified [34] [15].

Step 1: Differential Expression Analysis

- Use DESeq2 for RNA-seq data or limma for microarray/proteomics data

- Apply multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg FDR < 0.05)

- Contrast each subtype against others and against controls

Step 2: Pathway and Network Analysis

- Perform Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) on ranked gene lists

- Calculate Hallmark pathway activities from MSigDB using GSVA

- Construct protein-protein interaction networks using STRING database

- Visualize networks in Cytoscape, identify network communities

Step 3: Functional Interpretation

- Annotate subtypes with enriched Gene Ontology terms, biological processes

- Identify master transcriptional regulators using TRRUST or DoRothEA

- Integrate with publicly available datasets (GTEx, BrainSpan) for context

Step 4: Validation with External Modalities

- Correlate molecular subtypes with neuroimaging findings (fMRI, DTI)

- Assess correspondence with in vitro models (cortical organoid phenotypes)

- Validate with cognitive testing, eye-tracking, or other behavioral measures

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for molecular subtyping, from sample preparation through subtype validation.

Successful implementation of molecular subtyping requires carefully selected reagents, computational tools, and analytical resources. The following table details essential components of the molecular subtyping toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Subtyping Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Considerations for ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Library Prep | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA | Transcriptome profiling from tissue or blood | Assess RNA quality (RIN) especially for postmortem brain samples |

| Proteomics Platforms | TMT/Isobaric Labeling (Thermo) | Multiplexed protein quantification | Normalize for batch effects across multiple MS runs |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | 10x Genomics Chromium | Cell-type-specific expression profiling | Essential for deconvolving brain heterogeneity; requires fresh/frozen tissue |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | BERTopic, BERTopic Library | Topic modeling for literature mining | Identify trends in ASD literature; classify articles into thematic clusters [15] |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape, Gephi | Visualization of molecular interaction networks | Map subtype-specific protein-protein interactions; customize visual styles [35] |

| Gene Set Analysis | MSigDB Hallmark Gene Sets | Pathway activity quantification | Calculate pathway scores for subtypes; identify dysregulated biological processes [32] |

| Cohort Management | R/Bioconductor, Python | Statistical analysis and visualization | Manage confounders (age, sex, batch effects); implement SNF, MOFA [31] |

Molecular subtyping represents a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize and investigate complex heterogeneous disorders like autism spectrum disorder. By moving beyond behavior-based classifications to biologically defined subgroups, researchers can begin to unravel the distinct etiological pathways that converge on similar phenotypic presentations. The integration of multi-omics technologies with sophisticated computational methods has enabled the identification of subtypes with distinct genetic architectures, developmental trajectories, and clinical outcomes [6].

The future of molecular subtyping in ASD research lies in several promising directions: the incorporation of temporal dynamics through longitudinal multi-omics analyses; the resolution of cellular heterogeneity through single-cell and spatially resolved omics technologies; and the application of advanced machine learning methods for pattern recognition in high-dimensional data [31]. Furthermore, the translation of these research findings into clinical practice requires developing accessible diagnostic classifiers and identifying subtype-specific therapeutic targets.

As these approaches mature, molecular subtyping will increasingly inform precision medicine approaches for ASD, enabling earlier identification, more accurate prognosis, and targeted interventions tailored to an individual's specific biological subtype. This transition from generic diagnoses to biologically informed classifications marks a fundamental advancement in our approach to neurodevelopmental disorders, offering new hope for understanding and treating these complex conditions.

Advanced Multi-Omics Integration Frameworks: Methods and Workflows

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by highly heterogeneous abnormalities in functional brain connectivity affecting social behavior. The research landscape has witnessed significant progress in understanding the molecular and genetic basis of ASD in the last decade, particularly through multi-omics approaches that integrate data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics [15]. This interdisciplinary focus has generated a vast and rapidly expanding body of scientific literature that presents both unprecedented opportunities and formidable challenges for researchers. PubMed alone contains approximately 5,000 scientific publications on ASD in just the last year, creating substantial bottlenecks in knowledge synthesis through traditional manual curation methods [15]. The heterogeneity of ASD manifestations and the interdisciplinary nature of contemporary research further complicate comprehensive literature analysis, necessitating advanced computational approaches to extract meaningful insights from this data deluge.

Within this context, literature mining pipelines have emerged as transformative tools that leverage artificial intelligence to accelerate the journey from raw data to actionable knowledge. These systems address critical limitations in traditional literature review by automating the classification of scientific publications into thematic clusters, extracting key biological entities, and enabling interactive exploration of research findings [15] [36]. For researchers focused on multi-omics studies in ASD, these pipelines offer particularly valuable capabilities for identifying molecular interplay underlying the autistic brain, discovering potential biomarkers, and understanding complex gene-environment interactions that contribute to disease etiology [37]. This technical guide examines the architecture, implementation, and applications of AI-driven literature mining pipelines specifically within the context of multi-omics ASD research, providing researchers with practical methodologies for enhancing their investigative workflows.

Pipeline Architecture: Components and Computational Framework

Literature mining pipelines for ASD research incorporate a sophisticated multi-stage architecture that transforms unstructured text into structured knowledge. The foundational framework typically consists of four interconnected modules: data acquisition, natural language processing, knowledge extraction, and application interfaces [15]. Each component addresses specific challenges in processing biomedical literature while maintaining computational efficiency and scientific accuracy.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: The initial stage involves gathering relevant scientific literature from databases such as PubMed using specialized search queries. For comprehensive ASD multi-omics analysis, effective queries might include "(Autism Spectrum Disorder AND Homo sapiens) AND (('2013/01/01'[Date - Completion]: '3000'[Date - Completion]))" which yielded 28,304 abstracts over a 10-year period in one implementation [15]. The retrieved abstracts undergo preprocessing including lemmatization and filtration of pronouns, determiners, and conjunctions using tools like WordNetLemmatizer implemented in NLTK (3.8.1) to standardize the text for subsequent analysis [15].