From Single-Omics to Multi-Omics: A Comprehensive Guide to High-Resolution Biological Insights and Clinical Translation

This article provides a thorough comparison of single-omics and multi-omics approaches, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

From Single-Omics to Multi-Omics: A Comprehensive Guide to High-Resolution Biological Insights and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a thorough comparison of single-omics and multi-omics approaches, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It begins by exploring the fundamental limitations of single-omics methods in capturing cellular heterogeneity and the paradigm shift towards integrated analysis. The content then delves into the advanced methodologies and real-world applications of multi-omics in drug discovery and clinical diagnostics, highlighting its power to uncover complex disease mechanisms. Subsequently, it addresses the significant computational challenges and emerging solutions for robust data integration. Finally, the article offers a critical evaluation of multi-omics performance through benchmarking studies and validation frameworks, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for precision medicine.

The Single-Omics Limitation: Why Multi-Layered Analysis is Revolutionizing Biology

Bulk omics technologies have long been the workhorse of molecular profiling, providing population-averaged data across entire tissue samples or cell populations. However, this averaging effect obscures a fundamental biological truth: cells within a population are individuals. Cellular heterogeneity drives critical biological processes in development, disease progression, and treatment response, yet remains invisible to conventional bulk approaches [1]. The emergence of single-cell and multi-omics technologies has revolutionized our capacity to resolve this heterogeneity, revealing complex cellular landscapes where rare but influential cell populations dictate disease outcomes and therapeutic efficacy. This comparison guide examines how bulk omics masks cellular heterogeneity and how single-cell resolution technologies provide the necessary lens to observe the true complexity of biological systems.

Bulk vs. Single-Cell Omics: Fundamental Technical Differences

Core Principles and Workflows

Bulk omics analyzes nucleic acids or proteins extracted from thousands to millions of cells simultaneously, yielding averaged measurements that represent the dominant signals while concealing cell-to-cell variations [2]. In contrast, single-cell omics maintains cell identity throughout the analytical process, enabling individual cellular profiling within heterogeneous populations [3].

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between these approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Bulk and Single-Cell Omics Approaches

| Feature | Bulk Omics | Single-Cell Omics |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-level average | Individual cell level |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Masked | Revealed |

| Rare Cell Detection | Limited (>1% typically) | Excellent (down to 0.1% or lower) |

| Required Input Material | High | Low (single cells) |

| Primary Workflow | Tissue → RNA/DNA extraction → Library prep → Sequencing | Tissue → Single-cell suspension → Cell partitioning & barcoding → Library prep → Sequencing |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher (dimensionality, technical noise) |

| Cost Per Sample | Lower | Higher |

| Key Applications | Differential expression, biomarker discovery, pathway analysis | Cell type identification, rare population detection, developmental trajectories, tumor heterogeneity |

The Single-Cell Revolution: Technical Foundations

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies employ sophisticated cell partitioning systems to isolate individual cells. Platforms like 10X Genomics Chromium use microfluidic chips to create Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs), where each droplet contains a single cell, a barcoded gel bead, and reaction reagents [2]. Each bead contains oligonucleotides with unique cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that enable precise tracking of transcript origin and quantification while mitigating PCR amplification biases [3].

This cell barcoding strategy forms the technological foundation for high-throughput single-cell analysis, allowing thousands of cells to be processed simultaneously while maintaining each cell's unique molecular identity throughout sequencing and analysis.

The Heterogeneity Masking Effect: Evidence from Direct Comparisons

Experimental Evidence of Masked Heterogeneity

A compelling demonstration of bulk omics limitations comes from cancer cell line studies. When 42 human cancer cell lines were analyzed using scRNA-seq, researchers discovered significant transcriptomic heterogeneity within individual cell lines, with 57% showing discrete subpopulations and 43% exhibiting continuous variation patterns [4]. This intra-cell-line heterogeneity, driven by copy number variation, epigenetic diversity, and extrachromosomal DNA distribution, would be entirely undetectable using bulk approaches [4].

In therapeutic contexts, bulk sequencing often misses rare subpopulations that drive treatment resistance. Single-cell multi-omics can detect these rare clones at frequencies as low as 0.1% of the population, enabling researchers to identify drug-resistant subclones early and understand their molecular characteristics [5].

Quantifying the Averaging Problem

The "averaging problem" can be visualized through a comparative analysis of how each technology interprets a heterogeneous sample:

This conceptual diagram illustrates how bulk approaches merge signals from distinct cell types, while single-cell technologies preserve and resolve this biological complexity.

Single-Omics vs. Multi-Omics: Expanding the Analytical Dimensions

From Correlation to Causation

While single-cell transcriptomics reveals cellular heterogeneity, it cannot establish causal relationships between molecular layers. Multi-omics approaches simultaneously measure multiple molecular dimensions within the same cell—such as genome, transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome—enabling direct observation of how genetic variations influence gene expression and protein translation [1] [6].

The experimental workflow for generating multi-omics data integrates complementary technologies:

Multi-Omics Applications in Oncology

In cancer research, multi-omics approaches have demonstrated particular value for:

- Clonal Evolution Mapping: Tracking how different subclones emerge and evolve under therapeutic selective pressures [5]

- Therapeutic Resistance Mechanisms: Identifying specific genetic and phenotypic changes in individual cells that confer drug resistance [4]

- Tumor Microenvironment Characterization: Simultaneously profiling cancer, immune, and stromal cells to understand cellular crosstalk [6]

Experimental Protocols and Data Generation

Representative Single-Cell RNA-seq Protocol

The following table outlines key methodologies for single-cell transcriptomic profiling:

Table 2: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Methodologies and Applications

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Chromium [2] [3] | Microfluidic droplet-based | High (10,000+ cells) | Cell atlas construction, heterogeneity analysis | High cell throughput, user-friendly workflow | 3' bias, limited full-length transcript recovery |

| SMART-seq3 [1] | Plate-based, full-length | Low-medium (hundreds of cells) | Alternative splicing, isoform detection | Full-length transcript coverage, high sensitivity | Lower throughput, higher cost per cell |

| MARS-seq [1] | Combinatorial indexing | High (thousands of cells) | Large-scale studies, developmental biology | Cost-effective for large cell numbers, minimal batch effects | Lower sequencing depth per cell |

| SPLiT-seq [1] | Combinatorial barcoding | High (thousands of cells) | Fixed tissue samples, archived specimens | Compatible with fixed cells, low equipment requirements | Lower mRNA recovery efficiency |

Multi-Omics Integration and Analysis Workflow

The analytical pipeline for single-cell multi-omics data involves several critical stages:

- Quality Control: Filtering cells based on detected genes, mitochondrial content, and other quality metrics [6]

- Normalization and Batch Correction: Addressing technical variations between experiments using methods like Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) or Harmony [6]

- Dimension Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) followed by visualization with UMAP or t-SNE [4]

- Cluster Identification and Annotation: Cell clustering based on transcriptional similarity and cell type identification using marker genes [7]

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Computational alignment of different molecular modalities from the same cells [6]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines key reagents and tools essential for implementing single-cell and multi-omics studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Single-Cell and Multi-Omics Research

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Chromium [2] [3] | Microfluidic cell partitioning | Single-cell RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, multi-ome applications |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies [6] | Sample multiplexing | Pooling multiple samples in one run, reducing batch effects |

| Template Switching Oligos (TSO) [1] | cDNA synthesis | Full-length transcript capture in SMART-seq protocols |

| Feature Barcoding Oligos | Surface protein detection | Simultaneous RNA and protein measurement (CITE-seq) |

| Chromatin Accessibility Kits | Epigenomic profiling | scATAC-seq for mapping open chromatin regions |

| V(D)J Enrichment Reagents | Immune receptor sequencing | T-cell and B-cell receptor repertoire analysis |

| Gel Beads with Barcodes [3] | Cell and molecule labeling | Cell identity preservation in droplet-based methods |

| Cell Preservation Media | Sample integrity maintenance | Viable cell suspension preparation for sensitive assays |

The averaging problem inherent to bulk omics approaches has profound implications for biological discovery and therapeutic development. Single-cell technologies resolve this limitation by exposing the cellular heterogeneity that drives development, disease progression, and treatment outcomes. Multi-omics approaches further enhance this resolution by enabling causal inferences across molecular layers within individual cells.

While bulk omics remains valuable for population-level studies and differential expression analysis in homogeneous samples, single-cell approaches are indispensable for characterizing complex tissues, identifying rare cell populations, and understanding cellular dynamics. The integration of these complementary perspectives—bulk and single-cell, single-omics and multi-omics—provides the most comprehensive understanding of biological systems, ultimately accelerating biomarker discovery, therapeutic target identification, and precision medicine implementation.

The completion of the human genome project marked a pivotal moment in biological research, yet it quickly became clear that the genetic blueprint alone cannot fully explain the complexity of life. This realization has propelled the rise of omics technologies that probe molecular events downstream of the genome. Transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have emerged as powerful disciplines that provide distinct yet complementary insights into biological systems. While transcriptomics measures RNA expression patterns, proteomics identifies and quantifies proteins, and metabolomics focuses on small-molecule metabolites. Individually, each approach offers a unique perspective on cellular function; together, they form a comprehensive framework for understanding biological complexity. This guide examines the distinct roles of these three omics technologies, their experimental methodologies, and how their integration in multi-omics approaches is transforming biological research and drug development.

Single-Omics Approaches: Core Principles and Applications

Transcriptomics: Mapping the Blueprint's Expression

Transcriptomics involves the systematic study of an organism's complete set of RNA transcripts, known as the transcriptome. This approach captures dynamic gene expression patterns, revealing which genes are actively being transcribed under specific conditions.

Key Technologies and Workflows:

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq): The dominant technology uses high-throughput sequencing to catalogue and quantify RNA populations. The standard workflow begins with RNA extraction, followed by cDNA library preparation, sequencing on platforms like Illumina NovaSeq, and computational analysis for alignment and differential expression detection [8].

- Data Output: Identifies differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with statistical significance, typically using thresholds like log2 fold change ≥2 and adjusted p-value ≤0.05 [9].

Strengths and Limitations: Transcriptomics provides a comprehensive view of gene regulation and can detect novel transcripts and splicing variants. However, it represents a intermediate layer between genotype and phenotype, with mRNA levels often correlating poorly with protein abundance due to post-transcriptional regulation [10].

Proteomics: From Genetic Instruction to Functional Effectors

Proteomics characterizes the entire protein complement of a biological system, including expression levels, post-translational modifications, and protein-protein interactions.

Key Technologies and Workflows:

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): The cornerstone technology, typically coupled with liquid chromatography (LC-MS/MS). Proteins are extracted, digested into peptides, separated by LC, and analyzed by MS. Tandem MS fragments peptides to determine amino acid sequences [10] [11].

- Data Output: Identifies and quantifies thousands of proteins, revealing differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) and their modifications.

Strengths and Limitations: Proteomics directly analyzes functional effectors, capturing post-translational modifications that profoundly regulate protein activity. Challenges include the technical difficulty of analyzing low-abundance proteins, the dynamic complexity of the proteome, and the high cost of instrumentation [11].

Metabolomics: The Dynamic Metabolic Phenotype

Metabolomics focuses on the comprehensive analysis of small-molecule metabolites (<1,500 Da) that represent the end products of cellular processes.

Key Technologies and Workflows:

- Mass Spectrometry and NMR: LC-MS and GC-MS are widely used for their sensitivity and broad metabolite coverage. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers structural elucidation and absolute quantification but lower sensitivity [12].

- Spatial Metabolomics: Emerging mass spectrometry imaging technologies like MALDI-MS and DESI-MS enable spatial resolution of metabolite distribution within tissues [12].

- Metabolic Flux Analysis: Uses stable isotope tracers (e.g., ¹³C-glucose) to track metabolic pathway activities dynamically [12].

Strengths and Limitations: Metabolomics most closely reflects phenotypic status and can detect rapid biochemical changes. However, metabolite coverage is challenged by extreme chemical diversity and dynamic range limitations [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Single-Omics Technologies

| Feature | Transcriptomics | Proteomics | Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | RNA transcripts | Proteins and peptides | Small-molecule metabolites |

| Key Technologies | RNA-Seq, microarrays | LC-MS/MS, protein arrays | LC/GC-MS, NMR |

| Temporal Resolution | Medium (minutes-hours) | Medium-hours (minutes for modifications) | High (seconds-minutes) |

| Coverage Depth | ~20,000 coding genes in humans | >10,000 proteins in deep profiling | 100s-1,000s of metabolites |

| Biological Insight | Regulatory potential | Functional effectors & modifications | Functional phenotype & pathway activity |

| Primary Limitations | Poor correlation with protein levels | Analytical complexity, dynamic range | Chemical diversity, annotation challenges |

Multi-Omics Integration: A Systems Biology Perspective

While single-omics analyses provide valuable insights, they offer fragmented views of biological systems. Multi-omics integration simultaneously analyzes multiple molecular layers, revealing interconnected networks and providing mechanistic understanding.

Integration Methodologies and Workflows

Successful multi-omics studies require careful experimental design and computational integration:

Experimental Design:

- Sample Collection: Matched samples from the same biological source processed in parallel [13] [8].

- Data Generation: Separate omics data generation followed by computational integration.

Computational Integration:

- Concatenation-Based Integration: Combines features from different omics layers into a single dataset for multivariate analysis [14].

- Network-Based Integration: Maps multiple omics datasets onto shared biochemical networks to identify dysregulated pathways [15].

- BERT Algorithm: A recently developed method for batch-effect reduction in incomplete multi-omics datasets, addressing technical variations across studies [16].

Revealing Biological Mechanisms Through Integration

Multi-omics approaches have uncovered novel biological insights across diverse fields:

Plant Biology Applications: In tomato plants exposed to salt stress, integrated transcriptomics and proteomics revealed that carbon-based nanomaterials restored expression of 358 proteins and 144 molecular features across both omics levels, identifying activation of MAPK and inositol signaling pathways as key protective mechanisms [10].

In Brasenia schreberi, triple-omics integration (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) revealed only moderate correlation between transcript and protein levels (r=0.50), highlighting the importance of post-transcriptional regulation in mucilage disappearance and identifying specific metabolites (epicatechin, catechin) and genes (MYB5, MUCI70) as key regulators [13].

Medical Research Applications: In radiation research, integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics of irradiated mice identified coordinated dysregulation of 2,837 genes and multiple metabolite classes (amino acids, phospholipids, carnitines), revealing disruptions in amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism that would be missed by single-omics approaches [9].

In gastric cancer classification, the MASE-GC framework integrated exon expression, mRNA expression, miRNA expression, and DNA methylation data using autoencoders and ensemble learning, achieving superior classification accuracy (0.981) compared to single-omics models [14].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Approaches and Applications

| Integration Strategy | Key Methodology | Advantages | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concatenation-Based | Feature merging before analysis | Simple implementation, works with standard classifiers | MASE-GC for gastric cancer classification [14] |

| Network-Based | Mapping omics data onto biochemical networks | Reveals pathway-level dysregulation | Radiation response mechanisms in mice [9] |

| Tree-Based Algorithms | Batch-effect reduction trees (BERT) | Handles missing data, improves cross-study integration | Large-scale proteomics and transcriptomics integration [16] |

| Autoencoder Fusion | Dimension reduction before integration | Handles high dimensionality, reduces noise | Multi-omics cancer subtyping [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Cutting-edge omics research requires specialized reagents and platforms for accurate molecular profiling:

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Omics Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TriZol Reagent | Simultaneous RNA/protein extraction from same sample | Transcriptomic & proteomic pairing in rice studies [8] |

| Illumina Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput RNA/DNA sequencing | RNA-Seq for transcriptome profiling [8] |

| Q-Exactive Mass Spectrometer | High-resolution LC-MS/MS analysis | Proteomic and metabolomic profiling [10] [12] |

| HILIC/RP Chromatography Columns | Metabolite separation prior to MS analysis | Comprehensive polar/non-polar metabolite coverage [12] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Metabolic flux analysis | [1-¹³C]-glucose for tracing glycolytic flux [12] |

| HarmonizR/BERT Algorithms | Batch-effect correction for data integration | Multi-study omics data integration [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Studies

Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics Protocol

This protocol is adapted from studies on plant salt tolerance [10] and rice carbohydrate metabolism [8]:

Sample Preparation:

- Grow biological replicates under controlled conditions (e.g., n=3-5 per group)

- Apply experimental treatment and collect matched samples

- Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C

RNA Extraction and Transcriptomics:

- Homogenize tissue in TriZol reagent

- Extract total RNA and assess quality (RIN >8.0)

- Prepare cDNA library using Illumina TruSeq kit

- Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (PE150)

- Align reads to reference genome (HISAT2) and identify DEGs (log2FC ≥2, adj. p-value ≤0.05)

Protein Extraction and Proteomics:

- Extract proteins from same starting material

- Digest with trypsin and desalt peptides

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS using Q-Exactive instrument

- Identify proteins against reference database

- Quantify differential expression (≥1.5-fold change, p-value ≤0.05)

Data Integration:

- Map DEGs and DEPs to KEGG pathways

- Identify concordant and discordant features

- Perform joint pathway enrichment analysis

Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Protocol

This protocol is adapted from radiation research in murine models [9]:

Sample Collection:

- Collect plasma/serum at multiple time points post-treatment

- Process samples immediately or store at -80°C

Metabolite Profiling:

- Extract metabolites using methanol:acetonitrile:water

- Analyze by LC-MS in both positive and negative ionization modes

- Identify metabolites against standard libraries (HMDB, METLIN)

- Perform multivariate analysis (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify DAMs

Transcriptome Profiling:

- Extract RNA from same animals' blood or tissues

- Perform RNA-Seq as described above

- Identify DEGs and perform GO enrichment

Multi-Omics Integration:

- Use Joint-Pathway Analysis to integrate metabolite and gene changes

- Construct interaction networks (STITCH, BioPAN)

- Identify key regulatory nodes and metabolic enzymes

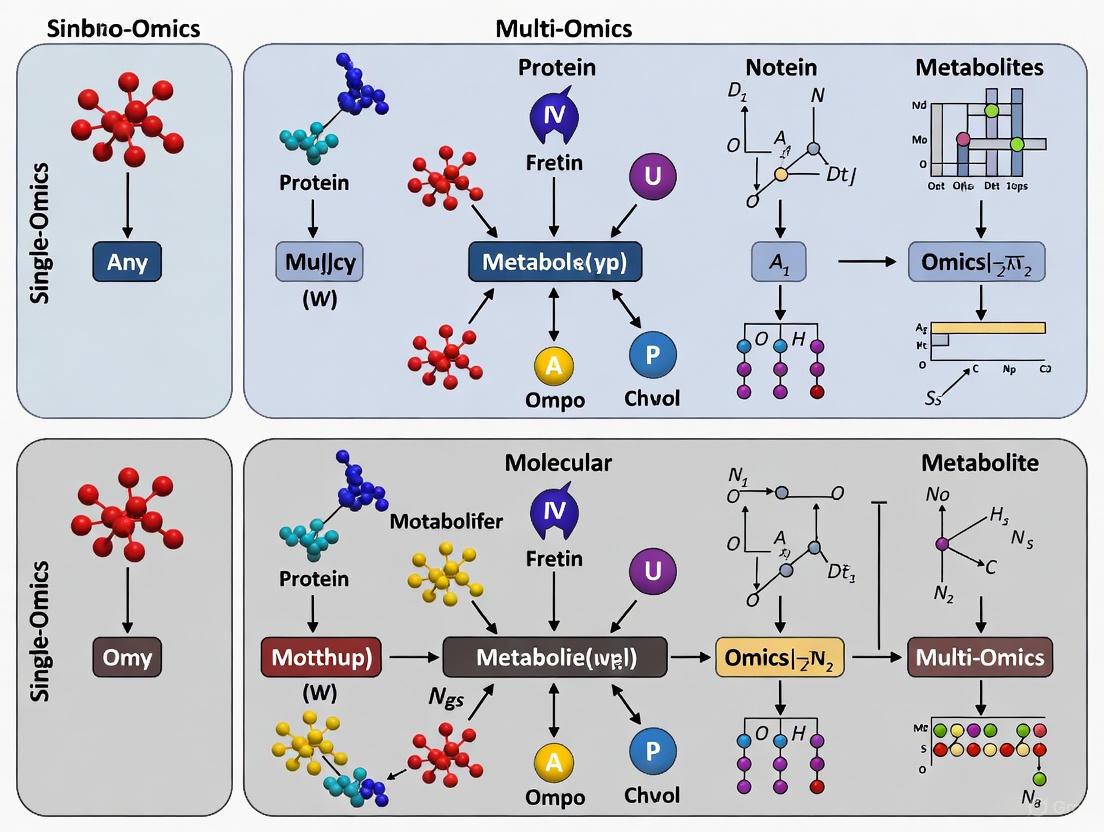

Visualizing Multi-Omics Workflows and Relationships

Multi-Omics Data Relationships and Workflow

The field of omics technologies is rapidly evolving, with several trends shaping its future. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing multi-omics data analysis, enabling pattern recognition in complex datasets that exceeds human capability [17] [15]. Single-cell multi-omics is revealing cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution, while spatial omics technologies are mapping molecular distributions within tissue architectures [15]. Liquid biopsy approaches are expanding beyond oncology to integrate cell-free DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites for non-invasive disease monitoring [17] [15].

The distinction between transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics remains fundamental to understanding biological systems, as each provides unique and non-redundant information. Transcriptomics reveals regulatory potential, proteomics identifies functional effectors, and metabolomics captures dynamic phenotypic status. While single-omics approaches continue to offer valuable insights, their integration through multi-omics frameworks provides the most comprehensive understanding of biological complexity. As these technologies become more accessible and computational integration methods more sophisticated, multi-omics approaches will increasingly drive discoveries in basic research, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic development, ultimately fulfilling the promise of systems biology and personalized medicine.

The fundamental premise of multi-omics is that biological complexity cannot be fully captured by studying a single molecular layer in isolation [18]. Traditional single-omics approaches, such as genomics or transcriptomics alone, provide a deep but narrow view, often described as "what could happen" (genetic potential) [19]. In contrast, multi-omics seeks to integrate this with data from transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics to reveal "how it is happening" – the dynamic, functional state of the cell or tissue [1] [20]. This guide objectively compares the performance and value of single-omics versus multi-omics approaches within biomedical research and drug discovery, supported by experimental data and benchmarking studies.

Comparative Analysis: Single-Omics vs. Multi-Omics Approaches

The following table summarizes the core differences in capabilities and outputs between single-omics and integrated multi-omics strategies, highlighting the transformative shift in biological insight.

Table 1: Core Capabilities and Limitations of Single-Omics vs. Multi-Omics Approaches

| Aspect | Single-Omics Approach | Multi-Omics Integrated Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Deep profiling of one molecular layer (e.g., genome, transcriptome) [18]. | Simultaneous or integrated profiling of multiple molecular layers (e.g., genome, transcriptome, proteome, epigenome) [1] [20]. |

| Resolution of Heterogeneity | Can reveal cellular heterogeneity but only within one dimension (e.g., transcriptomic cell types) [1]. | Reveals multi-dimensional heterogeneity, linking genetic variation to functional states across omics layers within the same cell or sample [1] [21]. |

| Biological Insight | Identifies associations (e.g., gene expression changes with disease) but cannot establish causality or mechanism [18]. | Elucidates causal relationships and regulatory networks (e.g., how a genetic variant influences chromatin accessibility, gene expression, and protein function) [1] [20]. |

| Key Limitation | Averages signals across cell populations, obscuring rare cells and nuanced states; provides a fragmented view of biology [1] [19]. | Technical and computational complexity in data generation, integration, and interpretation [22] [20] [19]. |

| Primary Output | Lists of differentially expressed genes, genetic variants, or metabolites [18]. | Unified models of disease mechanisms, predictive biomarkers from combined layers, and prioritized therapeutic targets [20] [19] [23]. |

Benchmarking Multi-Omics Integration Methods: Performance Data

The utility of multi-omics data hinges on effective computational integration. A 2025 benchmark study evaluated 40 methods across tasks like dimension reduction, clustering, and feature selection [22]. Furthermore, direct comparisons of statistical versus deep learning-based integration for specific diseases provide concrete performance metrics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MOFA+ (Statistical) vs. MoGCN (Deep Learning) for Breast Cancer Subtype Classification [23]

| Evaluation Metric | MOFA+ (Statistical Integration) | MoGCN (Deep Learning Integration) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best F1 Score (Nonlinear Model) | 0.75 | 0.70 | MOFA+ selected features yielded superior subtype classification accuracy. |

| Number of Relevant Pathways Identified | 121 | 100 | MOFA+ uncovered a broader range of biologically relevant pathways. |

| Key Pathways Implicated | Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis; SNARE pathway | – | Highlights potential immune response and tumor progression mechanisms. |

| Clustering Quality (Calinski-Harabasz Index) | Higher score indicates better separation. | Lower score compared to MOFA+. | MOFA+ generated latent factors that more effectively distinguished subtypes. |

| Feature Selection Basis | Loadings from latent factors explaining shared variance across omics. | Importance scores from autoencoder weights combined with feature variance. | Statistical method prioritized stable, interpretable cross-omics signals. |

The broader benchmark confirms that method performance is highly dataset- and modality-dependent, with tools like Seurat WNN, Multigrate, and Matilda also performing well for specific integration tasks [22].

Experimental Protocols for Key Multi-Omics Integration Studies

The following detailed methodology is synthesized from a representative study comparing integration methods for breast cancer subtyping [23] and general principles from benchmarking protocols [22].

Protocol: Multi-Omics Integration for Disease Subtype Classification

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Source: Download multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, epigenomics/methylation, microbiomics) from public repositories like cBioPortal (TCGA) [23].

- Batch Effect Correction: Apply appropriate batch correction methods for each data type (e.g., ComBat for transcriptomics, Harman for methylation data) using packages like

svain R [23]. - Filtering: Remove features with excessive zeros (e.g., expression in <50% of samples) to reduce noise [23].

2. Data Integration Using Comparative Methods:

- Statistical Integration (MOFA+):

- Use the

MOFA+R package. - Train the model on normalized multi-omics matrices to infer Latent Factors (LFs).

- Set convergence criteria (e.g., 400,000 iterations) and select LFs that explain >5% variance in at least one data type [23].

- Perform feature selection by extracting the top N features (e.g., 100 per omics layer) based on absolute loadings from the most explanatory LF [23].

- Use the

- Deep Learning Integration (MoGCN):

- Implement the MoGCN framework, which uses separate autoencoders for each omics layer for dimensionality reduction.

- Configure autoencoder architecture (e.g., hidden layers with 100 neurons, learning rate of 0.001).

- Train the model and calculate feature importance scores by multiplying absolute encoder weights by the feature's standard deviation.

- Select the top N features per omics layer based on this importance score [23].

3. Downstream Evaluation:

- Clustering Assessment: Generate embeddings from integrated features or factors. Apply t-SNE for visualization and calculate internal validation metrics like the Calinski-Harabasz Index (higher is better) and Davies-Bouldin Index (lower is better) [23].

- Supervised Classification: Use the selected features to train supervised classifiers (e.g., Support Vector Classifier with linear kernel, Logistic Regression) with 5-fold cross-validation. Use the F1 score to evaluate subtype prediction performance, especially for imbalanced classes [23].

- Biological Validation: Perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., using IntAct database via OmicsNet 2.0) on selected transcriptomic features to assess biological relevance (P-value < 0.05) [23].

Visualizing the Workflow and Hypothesis

Diagram 1: The Central Hypothesis of Multi-Omics Integration

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Multi-Omics Comparison Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential platforms, reagents, and software tools critical for executing single and multi-omics research, as derived from the search results.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Single-Cell and Multi-Omics Research

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Platform | Enables high-throughput single-cell RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and multiome (RNA+ATAC) profiling using droplet-based microfluidics. | [1] [21] |

| CITE-seq / REAP-seq | Assay/Reagent | Allows simultaneous measurement of single-cell transcriptomes and surface protein abundance (via antibody-derived tags - ADTs). | [22] |

| Primary Template-directed Amplification (PTA) | Reagent/Method | A whole-genome amplification method for single cells offering higher accuracy and uniformity for genomic analysis. | [1] |

| Smart-seq3 | Assay/Reagent | A plate-based scRNA-seq method for full-length transcript coverage, enabling isoform and splicing analysis. | [1] |

| MOFA+ | Software | A statistical, unsupervised tool for integrating multi-omics data by inferring latent factors that capture shared and specific variations. | [22] [23] [24] |

| Single-cell analyst | Software Platform | A user-friendly, web-based platform for comprehensive analysis of six single-cell omics types and spatial data without coding. | [25] |

| Seurat WNN | Software Algorithm | A method for vertical integration of multi-modal data (e.g., RNA + ADT) to construct weighted nearest neighbor graphs for joint analysis. | [22] |

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) | Platform/Technique | Enables spatial metabolomic and proteomic profiling within intact tissue sections, crucial for spatial multi-omics. | [26] |

The field of biomedical research is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a reductionist approach that studies biological components in isolation to a holistic, systems-based methodology. This shift is characterized by the transition from single-omics investigations to integrated multi-omics analyses, enabled by technological advances that allow researchers to simultaneously measure multiple molecular layers within the same biological sample [15]. Where traditional "bulk" analysis averaged signals across millions of cells, effectively masking critical cell-to-cell variations, modern single-cell multi-omics now enables direct measurement of individual signals from each cell, significantly enhancing our ability to unveil biological heterogeneity [5] [27].

This paradigm shift is revolutionizing how researchers investigate complex biological systems, moving beyond observational correlations toward understanding causal relationships between different molecular layers. By integrating data from genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics, researchers can now achieve a comprehensive understanding of how genetic variations influence gene expression and protein function within individual cells [5]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for understanding complex diseases like cancer, where different subclones can drive resistance or metastasis, and for advancing cell and gene therapies, where the single cell is the drug product itself [5].

The Multi-Omics Landscape: Key Technologies and Methodologies

Fundamental Omics Layers and Their Roles

Multi-omics integration combines data from multiple biological "omes" to provide a more complete picture of cellular function and dysfunction. Each biological layer offers distinct but complementary information [5]:

- Genomics: Focuses on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of an organism's DNA, revealing genetic variations such as single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variants (CNVs), insertions-deletions (INDELs), and translocations.

- Transcriptomics: Involves the study of the complete set of RNA transcripts produced by the genome, reflecting gene expression and cellular activity at a given time.

- Proteomics: Evaluates protein expression for better understanding of cellular function and prediction of therapeutic responses.

- Epigenomics: Examines heritable changes in gene expression activity caused by factors other than DNA changes, such as DNA methylation or chromatin accessibility.

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies

Recent advances in single-cell technologies have revolutionized cellular analysis, enabling comprehensive exploration of cellular heterogeneity, developmental trajectories, and disease mechanisms at unprecedented resolution [28]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has evolved from sequencing a single mouse blastomere in 2009 to currently profiling tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment [21] [27].

The key technological innovation enabling this progress has been the development of microfluidic-based systems for single-cell isolation and library preparation. Droplet-based microfluidics, such as 10X Genomics' Chromium system, significantly improved cell capture rates and throughput to thousands of cells per sample [27]. A crucial technical advancement has been the incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), which enable accurate quantification of original molecule abundance before amplification by detecting and correcting artifacts introduced during the aggressive amplification process required for single-cell sequencing [27].

Computational Integration Approaches

The technological revolution in measurement capabilities has necessitated parallel advances in computational methods for integrating multi-omics datasets. Current integration strategies can be categorized into four prototypical approaches based on input data structure and modality combination [22]:

- Vertical Integration: Combining different modalities (e.g., RNA, ADT, ATAC) measured on the same set of cells

- Diagonal Integration: Integrating datasets with partial feature overlap

- Mosaic Integration: Aligning datasets that do not measure the same features by leveraging shared cell neighborhoods

- Cross Integration: Transferring information across different experimental batches or conditions

Table 1: Computational Methods for Multi-Omics Integration

| Integration Category | Representative Methods | Primary Applications | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Integration | Seurat WNN, sciPENN, Multigrate, Matilda | Dimension reduction, clustering, feature selection | Generally better biological variation preservation; top-performing for RNA+ADT and RNA+ATAC datasets [22] |

| Foundation Models | scGPT, scPlantFormer, Nicheformer | Cross-species annotation, perturbation modeling, spatial context prediction | scGPT pretrained on 33M+ cells demonstrates zero-shot cell type annotation; scPlantFormer achieves 92% cross-species accuracy [28] |

| Multimodal Alignment | PathOmCLIP, StabMap, GIST | Histology-gene mapping, non-overlapping feature alignment | Robust integration under feature mismatch; enables 3D tissue modeling [28] |

Experimental Comparison: Single-Omics vs. Multi-Omics Performance

Benchmarking Study Design and Metrics

A comprehensive registered report published in Nature Methods (2025) systematically categorized and benchmarked 40 integration methods across 64 real datasets and 22 simulated datasets [22]. The study evaluated methods across seven common computational tasks: dimension reduction, batch correction, clustering, classification, feature selection, imputation, and spatial registration. Performance was assessed using tailored evaluation metrics for each task, with methods ranked based on their overall grand rank scores across different modality combinations [22].

For survival prediction benchmarking, a large-scale study evaluated all 31 possible combinations of five genomic data types (mRNA, miRNA, methylation, DNAseq, and copy number variation) using 14 cancer datasets from TCGA [29]. Predictive performance was measured using Harrell's C-index and integrated Brier Score, with statistical testing conducted for key results to ensure robustness [29].

Performance Across Biological Applications

The benchmarking results reveal that multi-omics integration consistently outperforms single-omics approaches for most biological discovery tasks, though with important nuances:

Table 2: Multi-Omics vs. Single-Omics Performance Comparison

| Application Domain | Single-Omics Limitations | Multi-Omics Advantages | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Identification | Limited resolution of heterogeneous populations; averaging effects | Precise cell state characterization; identification of rare subpopulations | Vertical integration methods (e.g., Seurat WNN, Multigrate) effectively preserve biological variation of cell types across modalities [22] |

| Survival Prediction | mRNA alone often sufficient but incomplete for some cancers | mRNA + miRNA ± methylation optimal for most cancers; more types hinder performance | For most cancer types, using only mRNA data or combining mRNA and miRNA was sufficient; adding more data types often decreased performance [29] |

| Clinical Impact | Assisting physicians with diagnoses only | Comprehensive health profiling; targeted treatments for rare diseases | Integration enables medical geneticists to direct patients with rare diseases to physicians who can offer targeted treatments [15] |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Inferred clonal architecture from bulk sequencing | Direct measurement of clonal heterogeneity; detection of rare subclones down to 0.1% | Identifies subtle differences in gene expression and responses to stimuli critical for understanding cancer and other diseases [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Vertical Integration Protocol for Dimension Reduction and Clustering

The benchmarked vertical integration workflow involves [22]:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize each modality separately using standard approaches (e.g., log transformation for RNA, centered log-ratio for ADT)

- Feature Selection: Identify highly variable features for each modality

- Method Application: Implement integration methods (e.g., Seurat WNN, Multigrate) following author specifications

- Embedding Generation: Create low-dimensional representations for downstream analyses

- Evaluation: Assess performance using metrics including iF1, NMIcellType, ASWcellType, and iASW

Foundation Model Pretraining Protocol

Advanced foundation models like scGPT employ a multi-stage training approach [28]:

- Self-Supervised Pretraining: Train on large-scale datasets (33+ million cells) using masked gene modeling objectives

- Multitask Finetuning: Adapt model to specific downstream tasks (cell type annotation, perturbation response prediction)

- Zero-Shot Evaluation: Assess cross-dataset generalization without task-specific training

- Biological Validation: Confirm that model outputs align with established biological knowledge

Visualization of Multi-Omics Workflows and Relationships

Conceptual Shift from Single-Omics to Multi-Omics Research

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of single-cell multi-omics research requires specialized reagents, platforms, and computational resources. The following toolkit outlines essential components for designing and executing multi-omics studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Single-Cell Multi-Omics

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Isolation Platforms | 10X Genomics Chromium, Fluidigm C1, Mission Bio Tapestri | High-throughput cell capture and barcoding | Throughput (hundreds to thousands of cells), multiplet rates, cell capture efficiency [21] [27] |

| Library Preparation Kits | CITE-seq, SHARE-seq, TEA-seq | Simultaneous profiling of multiple molecular layers | Compatibility with downstream sequencing platforms, coverage (3'/5' vs full-length), UMI incorporation [22] [27] |

| Computational Platforms | Galaxy single-cell & spatial omics (SPOC), BioLLM, DISCO, CZ CELLxGENE | Data analysis, integration, and visualization | User accessibility, reproducibility, tool diversity (175+ tools in Galaxy), training resources [28] [30] |

| Foundation Models | scGPT, scPlantFormer, Nicheformer | Cross-task generalization, zero-shot annotation | Pretraining corpus size, model architecture, interpretability features [28] |

| Integration Methods | Seurat WNN, Multigrate, Matilda, MOFA+ | Vertical integration of multiple modalities | Performance in dimension reduction, feature selection, batch correction [22] |

The transition from siloed single-omics data to holistic multi-omics integration represents more than just a technical advancement—it constitutes a fundamental shift in how we approach biological research. This paradigm shift enables researchers to move beyond observational correlations to understanding causal relationships between different molecular layers within individual cells [5]. The evidence from comprehensive benchmarking studies indicates that while multi-omics approaches generally provide superior biological insights, the strategic selection of modalities is crucial, as adding more data types does not automatically improve performance and may even hinder it in predictive applications [29].

As the field continues to evolve, several emerging trends are shaping the future of multi-omics research. Foundation models pretrained on millions of cells are enabling zero-shot cell type annotation and perturbation response prediction [28]. Spatial multi-omics technologies are adding geographical context to molecular measurements, providing insights into cellular organization and communication [30]. Federated computational platforms are facilitating global collaboration while addressing data privacy concerns [28]. Most importantly, the clinical translation of multi-omics approaches is accelerating, with applications in diagnostics, patient stratification, and personalized treatment showing significant promise [15] [5].

To fully realize the potential of this conceptual shift, researchers must continue to develop standardized protocols, robust computational infrastructure, and analytical frameworks that can handle the complexity and scale of multi-omics data. By embracing this holistic approach to biological systems, the scientific community can unravel the intricate networks underlying health and disease, ultimately leading to more effective therapies and improved patient outcomes.

Multi-Omics in Action: Methodologies Driving Discoveries in Drug Development and Disease Research

The evolution of single-cell technologies has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, transitioning research from bulk tissue analysis to single-cell resolution and more recently, to multi-modal characterization. While single-omics approaches like scRNA-seq have been instrumental in revealing cellular diversity, they fundamentally lack the ability to simultaneously profile multiple molecular layers from the same cell. This limitation has driven the development of integrated multi-omics technologies that can co-profile different molecular types within individual cells while preserving crucial spatial context.

Multi-omics technologies represent a paradigm shift in biological research by enabling the correlated analysis of different molecular modalities from the same biological sample. CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing) allows for simultaneous measurement of transcriptome and surface protein expression in single cells. SHARE-seq (Simultaneous Hybridization and Release by Elution sequencing) enables coupled profiling of transcriptome and chromatin accessibility. Spatial transcriptomics technologies capture gene expression patterns within the context of tissue architecture, preserving the spatial relationships between cells that are lost in dissociated single-cell approaches. This comparative guide examines the technical capabilities, performance characteristics, and experimental considerations of these core multi-omics platforms to inform researchers' technology selection.

Technical Specifications and Data Output

Table 1: Core Multi-Omics Technologies Comparison

| Technology | Molecular Modalities | Spatial Resolution | Throughput (Cells) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CITE-seq | Transcriptome + Surface Proteins (10-500 markers) | Not spatially resolved | 10,000-100,000+ | Immune profiling, cell type validation, surface marker identification |

| SHARE-seq | Transcriptome + Chromatin Accessibility | Not spatially resolved | 10,000-100,000+ | Gene regulation studies, lineage tracing, epigenetic dynamics |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Genome-wide transcriptome | 0.5 μm - 100 μm (platform-dependent) | Tissue area-based | Tissue architecture analysis, cellular neighborhoods, spatial gene expression |

Table 2: Spatial Transcriptomics Platform Performance Comparison

| Platform | Technology Type | Spatial Resolution | Genes Detected | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Visium | Sequencing-based (SISB) | 55 μm spots | Whole transcriptome | High correlation with scRNA-seq; robust for tissue domain identification |

| Stereo-seq | Sequencing-based (SISB) | 0.5 μm bins | Whole transcriptome | Highest capturing capability; regular array size up to 13.2 cm [31] |

| 10X Xenium | Imaging-based (SISS) | Subcellular | 5001 genes (Xenium 5K) | Superior sensitivity for marker genes; higher transcript counts without sacrificing specificity [32] [33] |

| Nanostring CosMx | Imaging-based (SISH) | Subcellular | 6175 genes (CosMx 6K) | High-plex protein and RNA detection; detects higher total transcripts than Xenium but with lower correlation to scRNA-seq [33] |

| Vizgen MERSCOPE | Imaging-based (SISH) | Subcellular | Custom panels (~1000 genes) | Direct probe hybridization with signal amplification via transcript tiling [32] |

Performance Benchmarking Insights

Recent systematic benchmarking studies reveal critical performance differences across platforms. In a comprehensive evaluation of imaging-based spatial transcriptomics (iST) platforms on FFPE tissues, Xenium consistently generated higher transcript counts per gene without sacrificing specificity, while both Xenium and CosMx demonstrated strong concordance with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics data [32]. All commercial iST platforms could perform spatially resolved cell typing with varying sub-clustering capabilities, with Xenium and CosMx identifying slightly more clusters than MERSCOPE, though with different false discovery rates and cell segmentation error frequencies [32].

For sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics (sST) platforms, comparative analysis of 11 methods revealed significant variability in molecule-capture efficiency and effective resolution across different tissues [31]. Stereo-seq demonstrated the highest capturing capability, while Slide-seq V2 showed higher sensitivity than other platforms in mouse eye tissue when sequencing depth was controlled [31]. Probe-based Visium and DynaSpatial also exhibited high sensitivity in hippocampal tissue [31].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CITE-seq Workflow and Protocol

CITE-seq Experimental Workflow

The CITE-seq protocol begins with preparation of a single-cell suspension from fresh tissue or cultured cells. Cells are stained with a cocktail of DNA-barcoded antibodies targeting surface proteins of interest. These antibodies contain a unique DNA barcode sequence that serves as a proxy for protein abundance. After staining and washing, cells are loaded into a microfluidic device for single-cell partitioning, typically using droplet-based systems. Within each droplet, individual cells are co-encapsulated with barcoded beads that capture both mRNA transcripts and antibody-derived tags (ADTs). Following reverse transcription and library preparation, separate sequencing libraries are generated for transcriptome and protein markers, which are subsequently sequenced and computationally integrated.

Key to successful CITE-seq experiments is antibody validation and titration to ensure specific binding and optimal signal-to-noise ratio. A typical experiment can profile 10,000-100,000+ cells simultaneously with panels ranging from 10-500 surface protein markers. The methodology has been successfully applied to immune cell characterization, where surface protein expression complements transcriptional profiles for precise cell type identification [34].

Spatial Transcriptomics Experimental Approaches

Spatial Transcriptomics Method Categories

Spatial transcriptomics methodologies fall into four main categories based on their underlying technical approaches [35]:

Spatial In Situ Hybridization (SISH): Representative technologies include seqFISH, MERFISH, and STARmap. These methods use labeled probes applied directly to tissue sections to capture spatial positions of specific RNA molecules along with sequence information through multiple rounds of hybridization and imaging.

Spatial In Situ Sequencing (SISS): Representative technologies include FISSEQ and 10X Xenium. These approaches perform sequencing directly on fixed tissue sections, typically using padlock probes and rolling circle amplification for signal generation.

Spatial Barcoding (SISB): Representative technologies include Slide-seq, DBiT-seq, 10X Visium, and Stereo-seq. These methods use arrays of DNA oligonucleotide capture probes with poly(T) sequences to bind mRNA, which then receive spatial barcodes for subsequent localization and quantification after bulk sequencing.

Spatial Isolation or Microdissection: Representative technologies include Tomo-seq, DSP, and GEO-seq. These approaches physically isolate or label specific tissue regions for subsequent DNA or RNA extraction and analysis.

Recent advancements have enabled multi-omi cs integration in spatial contexts. Spatial-CITE-seq, for example, extends the CITE-seq principle to spatial applications by using a cocktail of 200-300 antibody-derived tags (ADTs) stained on a tissue slide followed by deterministic in-tissue barcoding of both DNA tags and mRNAs for spatially resolved high-plex protein and transcriptome co-profiling [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Technologies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technology Applications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-barcoded Antibodies (ADTs) | Convert protein detection to DNA sequencing signal; contain poly-A tail, UMI, and antibody-specific sequence | CITE-seq, REAP-seq, Spatial-CITE-seq |

| Barcoded Beads | Capture mRNA and ADTs with cell-specific barcodes during single-cell partitioning | CITE-seq, SHARE-seq, droplet-based single-cell methods |

| Padlock Probes | Circularizable probes for targeted in situ amplification; enable spatial transcript detection | ISS-based methods, 10X Xenium, STARmap |

| Spatial Barcode Arrays | Oligonucleotide arrays with spatial coordinates for capturing mRNA from tissue sections | 10X Visium, Stereo-seq, Slide-seq |

| Permeabilization Reagents | Control tissue accessibility for mRNA capture; critical for data quality optimization | All spatial transcriptomics methods |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Prevent RNA degradation during sample preparation and processing | All RNA-based multi-omics technologies |

| Indexing PCR Primers | Add sample indices and sequencing adapters during library preparation | All sequencing-based multi-omics methods |

Applications and Biological Insights

Multi-omics technologies have enabled significant advances across diverse biological domains. In immunology research, CITE-seq has proven particularly valuable for comprehensive immune cell profiling. The technology's ability to simultaneously measure transcriptomic states and surface protein expression enables precise identification of immune cell subsets that might be indistinguishable using transcriptomics alone [34]. Supervised machine learning frameworks like MMoCHi have been developed specifically to leverage this multimodal data for accurate cell-type classification across lineages and tissues [34].

In clinical and translational research, spatial multi-omics approaches have revealed novel biological insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses. A study of ulcerative colitis patients undergoing vedolizumab therapy employed single-cell transcriptomic and proteomic analyses alongside spatial multi-omics to identify previously unappreciated effects on mononuclear phagocyte subsets and fibroblast populations [37]. Spatial transcriptomics of archived clinical specimens identified epithelial-, mononuclear phagocyte-, and fibroblast-enriched genes related to treatment responsiveness, highlighting the power of these approaches to uncover spatial biomarkers [37].

Spatial-CITE-seq applications in human tissues have demonstrated the value of high-plex protein mapping, revealing spatially distinct patterns of immune organization in tonsil tissue and early immune activation at COVID-19 mRNA vaccine injection sites [36]. The technology's capacity to map 273 proteins alongside the whole transcriptome enabled identification of spatially restricted germinal center reactions and previously uncharacterized protein localization patterns, such as CD171 restriction to the dark zone of germinal centers [36].

The rapid evolution of multi-omics technologies continues to transform biological research by enabling increasingly comprehensive molecular profiling with enhanced spatial context. CITE-seq, SHARE-seq, and spatial transcriptomics each offer unique strengths for specific research applications, with choice of technology dependent on the biological questions, required resolution, and molecular features of interest.

Future developments in the field are likely to focus on several key areas. Throughput and multiplexing capacity continue to expand, with newer spatial platforms now offering whole transcriptome coverage at subcellular resolution. Multi-omics integration will become increasingly sophisticated, enabling simultaneous profiling of transcriptome, proteome, epigenome, and other molecular layers within the same spatial context. Computational methods development will be crucial for extracting maximal biological insight from these complex multimodal datasets. Finally, efforts to reduce costs and simplify workflows will be essential for broader adoption across the research community.

As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they will continue to drive fundamental discoveries in basic biology while enabling new approaches in translational research and clinical diagnostics. The complementary nature of these platforms underscores the importance of selecting appropriate technologies based on specific research goals, with multi-omics integration providing a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems than any single modality alone.

Linking Cellular Heterogeneity to Drug Response and Resistance Mechanisms

Cellular heterogeneity is a fundamental characteristic of cancer, driving diverse patient responses to therapy and the eventual emergence of treatment resistance [38] [39]. For decades, research relied on single-omics approaches—analyzing genomics, transcriptomics, or proteomics in isolation. While these methods identified key driver mutations and expression signatures, they often failed to capture the complex, multilayer interactions within the tumor ecosystem [38]. The advent of multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift, enabling a systems-level view that links genetic alterations to downstream functional consequences across molecular layers [40] [38]. This guide compares these two research frameworks, evaluating their methodologies, experimental outputs, and utility in elucidating drug response and resistance mechanisms.

Comparative Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Data Integration

Single-Omics Approaches: Targeted but Limited

Traditional single-omics studies focus on one molecular layer. A typical genomics protocol involves:

- Sample Processing: Extraction of DNA from tumor tissue or cell lines.

- Sequencing: Whole-exome sequencing (WES) or targeted panel sequencing (e.g., Tempus xT assay) to identify somatic mutations, copy number variations, and fusions [38] [41].

- Analysis: Variant calling, annotation, and association with drug response phenotypes (e.g., progression-free survival). For instance, identifying ESR1 or RB1 mutations in breast cancer resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors [41]. The primary limitation is the inability to connect a genomic alteration to its functional transcriptional, proteomic, or metabolic outcome, offering a correlative but not mechanistic insight [38].

Multi-Omomics Integration: A Holistic Workflow

Multi-omics studies require coordinated profiling and sophisticated computational integration. A representative protocol from a recent real-world study on CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance includes [41]:

- Sample Cohort: Collection of paired pre-treatment and post-progression tumor biopsies from a defined patient population (e.g., HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer).

- Multi-Modal Profiling:

- DNA Sequencing: Targeted DNA sequencing (e.g., Tempus xT) on all samples to derive genomic alteration frequencies.

- RNA Sequencing: Whole-transcriptome sequencing (e.g., Tempus RS) to calculate gene expression signatures, pathway scores, and molecular subtypes.

- Bioinformatics Pipeline:

- Feature Extraction: Generation of three feature types: genomic alterations, gene expression signatures (e.g., Hallmark pathways), and analytically derived features (e.g., proliferation indices).

- Integrative Clustering: Application of machine learning (e.g., non-negative matrix factorization) on combined genomic and transcriptomic data to identify molecular subgroups.

- Trajectory Inference: Use of algorithms (e.g., pseudotime analysis) on multi-omics data to model the evolution of resistance.

- Validation: In vitro or in vivo experimental validation of predicted therapeutic dependencies (e.g., CDK2 inhibition in ER-independent resistant models) [41].

Advanced computational models like PASO and HGACL-DRP further exemplify this integrative approach. PASO processes multi-omics data (gene expression, mutation, copy number) to compute pathway-based difference features, combines them with drug SMILES sequences, and uses a deep learning architecture (transformer encoder, multi-scale CNN, attention) to predict drug response [42]. HGACL-DRP constructs a heterogeneous graph from multi-omics features and drug data, employing graph attention networks and contrastive learning for prediction [43].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

The superiority of multi-omics integration is demonstrated through quantitative gains in prediction accuracy and biological discovery.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Omics Approaches in Key Studies

| Study / Model | Approach | Primary Data Types | Key Performance Metric | Key Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PASO Model [42] | Multi-omics Integration | Gene expression, mutation, CNV pathways; Drug SMILES | Higher accuracy vs. state-of-the-art methods (Precily, PathDSP, HiDRA) | Identified PARP inhibitors as sensitive in SCLC; Highlights relevant pathways & drug substructures. |

| Real-World CDK4/6i Resistance [41] | Multi-omics Integration | Targeted DNA-seq, RNA-seq (Pre/Post biopsies) | Identified 3 resistance subgroups; ER-independent prevalence increased from 5% (Pre) to 21% (Post). | Revealed bifurcated evolution: ER-dependent (ESR1 mut) vs. ER-independent (TP53 mut, CCNE1 amp). |

| scDEAL Model [42] | Multi-omics Transfer Learning | Bulk & single-cell RNA-seq | Enables drug response prediction at single-cell resolution. | Addresses intra-tumor heterogeneity by leveraging single-cell data. |

| Traditional Genomics Study (Implied) [38] [41] | Single-Omics (Genomics) | DNA sequencing only | Can identify mutation frequency changes (e.g., ESR1: 15%→41.9%). | Lacks functional context; cannot define integrative subgroups or evolutionary trajectories. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Datasets and Model Performance

| Dataset / Resource | Use Case | Key Metric from Multi-Omics Studies | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDSC / CCLE | Drug response prediction benchmarking | HGACL-DRP achieved mean AUC of 98.99% (GDSC) and 95.48% (CCLE). [43] | [42] [43] |

| Tempus Real-World Database | Profiling clinical resistance | Pre/Post analysis of 427 samples identified significant increase in RB1 alterations (3%→13.2%). [41] | [41] |

| TCGA Clinical Data | Model validation | PASO model predictions correlated significantly with patient survival outcomes. [42] | [42] |

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Tempus xT & xR Assays | Integrated targeted DNA and whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples for real-world evidence studies. | Tempus Labs [41] |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Platform | Enables high-throughput single-cell multi-omics profiling (scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq) for dissecting tumor heterogeneity. | 10x Genomics [39] |

| CCLE & GDSC Databases | Public repositories providing harmonized multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics) and drug sensitivity measurements for hundreds of cancer cell lines. | Broad Institute, Sanger Institute [42] [43] |

| Pathway Databases (e.g., KEGG, Reactome) | Provide curated biological pathway knowledge used to compute pathway-level features from raw omics data. | Kanehisa Labs, EMBL-EBI [42] |

| Graph Neural Network Frameworks (e.g., PyTorch Geometric) | Software libraries essential for building and training advanced integration models like HGACL-DRP that use heterogeneous graph structures. | PyTorch [43] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short nucleotide barcodes used in single-cell sequencing to accurately label and quantify individual RNA molecules, reducing technical noise. | Integrated in platforms like 10x Genomics [39] |

In the evolving landscape of biological research, a fundamental thesis contrasts single-omics approaches with multi-omics strategies. Single-omics studies, focusing on isolated molecular layers like the genome or transcriptome, offer a partial view of biological systems and often fail to capture the complex, cross-layer regulatory mechanisms that define cellular function and disease [44] [5]. Multi-omics integration emerges as a transformative paradigm, seeking a holistic understanding by simultaneously analyzing multiple biological data layers [15] [45]. A critical frontier within multi-omics is network integration, where diverse molecular entities (genes, proteins, metabolites) are mapped onto shared biochemical pathways and interaction networks [15] [45]. This guide compares methodologies that enable this mapping, evaluates their performance against single-omics and alternative multi-omics tools, and details the experimental protocols that empower researchers to move from correlation to causation.

Methodological Comparison: From Single-Layer Inference to Multi-Layer Integration

The core challenge lies in transitioning from analyzing static correlations within one data type to inferring dynamic, causal interactions across omics layers. The following table summarizes and compares key approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Network Inference and Integration Methods

| Method Name | Approach Type | Omic Layers Integrated | Key Innovation | Primary Output | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional GRN Inference (e.g., ARACNe) [45] | Single-Omic, Data-Driven | Transcriptomics only (bulk or single-cell) | Uses mutual information or correlation to infer gene-gene regulatory interactions. | Gene Regulatory Network (GRN). | Limited to intra-layer (gene-gene) interactions; overlooks regulation from other molecular layers. |

| Knowledge-Driven Integration [45] | Multi-Omic, Prior Knowledge-Based | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics | Maps measured molecules onto curated interaction databases (e.g., KEGG, BioGRID). | Hybrid network combining data with known interactions. | Reliant on existing, often incomplete, knowledge; cannot discover novel, context-specific interactions. |

| MINIE [44] | Multi-Omic, Dynamical Model-Based | Transcriptomics (single-cell) & Metabolomics (bulk) | Uses Differential-Algebraic Equations (DAEs) to model timescale separation; Bayesian regression for causal inference. | Causal regulatory network with intra- and inter-layer interactions (e.g., gene-metabolite). | Currently validated on transcriptome-metabolome pairs; requires time-series data. |

| netOmics Framework [45] | Multi-Omic, Hybrid & Longitudinal | Flexible (e.g., Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics) | Integrates data-driven inference, prior knowledge, and longitudinal modeling (clustering of time profiles). | Time-aware, hybrid multi-omics networks and functional modules. | Complexity in interpreting large, multi-layered networks. |

| Vertical Integration Methods (e.g., Seurat WNN, MOFA+) [22] | Multi-Modal, Alignment-Based | Paired modalities from same cells (e.g., RNA+ADT, RNA+ATAC) | Aligns different data types to create a unified cell embedding for clustering and visualization. | Integrated cell embeddings, cell type clusters, and correlated features. | Focuses on cell state rather than mechanistic biochemical pathways; infers correlations, not causality. |

Supporting Performance Data: Benchmarking studies highlight the advantages of purpose-built multi-omics integration. The MINIE method demonstrated "accurate and robust predictive performance across and within omic layers" and outperformed state-of-the-art single-omic methods in network inference tasks [44]. In comprehensive benchmarks of single-cell multimodal integration, methods like Seurat WNN and Multigrate performed well on tasks like dimension reduction and clustering for paired RNA and protein (ADT) data [22]. However, these vertical integration tools are optimized for cell typing, not for reconstructing inter-omic biochemical pathways. The netOmics approach, through case studies, identified "new multi-layer interactions involved in key biological functions that could not be revealed with single omics analysis" [45], directly supporting the thesis that multi-omics network integration provides superior mechanistic insight.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Successful network integration requires rigorous, multi-step analytical workflows. Below are detailed protocols for two representative methodologies.

Objective: To build and interpret a multi-layer interaction network from longitudinal multi-omics data.

- Sample Preparation & Data Generation: Collect biological samples (e.g., tissue, cell culture) across multiple time points. For each sample, perform parallel extraction and sequencing/assaying for at least two omics layers (e.g., RNA-seq, Proteomics via Mass Spectrometry, Metabolomics).

- Pre-processing & Normalization: Process raw data per standard pipelines for each omic type. Filter out low-abundance molecules. Normalize counts to account for technical variation within each dataset (block).

- Longitudinal Modeling & Clustering: For each molecule across time points, fit a Linear Mixed Model Spline to capture its expression/abundance trajectory. Cluster molecules (within and across omics layers) based on similar longitudinal profiles using multi-block Projection on Latent Structures (PLS). This results in kinetic clusters of co-behaving molecules.

- Network Reconstruction:

- Data-Driven Layer: Apply inference algorithms specific to each data type. For gene expression, use GRN inference (e.g., ARACNe) on time-course data to predict transcription factor-target interactions [45].

- Knowledge-Driven Layer: For each measured molecule, query curated databases to retrieve known interactions:

- Network Integration & Propagation: Merge the data-driven and knowledge-driven interactions into a single, heterogeneous multi-omics network. Optionally, create sub-networks for each kinetic cluster. Apply a random walk with restart algorithm from a set of seed nodes (e.g., known disease-associated genes) to propagate signals through this hybrid network and identify novel, high-proximity candidate genes or metabolites associated with the phenotype.

- Validation & Interpretation: Perform enrichment analysis on network modules. Validate top predictions using orthogonal experimental methods (e.g., CRISPR knockdown followed by metabolomics).

Objective: To infer a causal regulatory network integrating single-cell transcriptomics and bulk metabolomics.

- Experimental Design: Conduct a time-course experiment, perturbing the system if desired. At each time point, collect samples for both single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and bulk metabolomic profiling.

- Data Input Preparation: Process scRNA-seq data to obtain a gene expression matrix (cells x genes) per time point. Process metabolomics data to obtain a concentration matrix (samples x metabolites) per time point.

- Transcriptome-Metabolome Mapping (Step 1): Model the fast metabolic dynamics at quasi-steady state using the algebraic equation:

0 ≈ A_mg * g + A_mm * m + b_m. Employ sparse regression constrained by a curated database of human metabolic reactions [44] to infer the interaction matricesA_mg(gene→metabolite) andA_mm(metabolite→metabolite). - Regulatory Network Inference via Bayesian Regression (Step 2): Model the slow transcriptomic dynamics using the differential equation:

dg/dt = f(g, m, b_g; θ) + ρ(g, m)w. Use the mapped metabolite datamfrom Step 1. Within a Bayesian regression framework, infer the parametersθthat define the regulatory network, identifying causal interactions from genes and metabolites to target genes. - Network Evaluation: Validate the inferred network using simulated data with known ground truth. Apply to experimental data (e.g., Parkinson's disease model) and triangulate high-confidence interactions with existing literature [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Resources for Multi-Omics Network Integration

| Item Name | Type | Function in Network Integration | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Interaction Databases | Knowledge Base | Provide the scaffold of known biochemical relationships (PPI, metabolic pathways, regulatory interactions) for mapping and constraining models. | KEGG Pathway [45], BioGRID [45], Reactome. |

| Multi-Omic Time-Series Datasets | Primary Data | The essential input for inferring dynamic, causal relationships. Requires coordinated sampling across layers. | Public repositories (GEO, PRIDE, Metabolomics Workbench) or custom experiments. |

| Network Inference & Modeling Software | Computational Tool | Implements algorithms for data-driven interaction prediction and integration. | MINIE (DAE/Bayesian framework) [44], netOmics R package [45], ARACNe [45]. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omic Platforms | Experimental Technology | Generates intrinsically linked multi-layer data (e.g., genome, transcriptome, proteome) from the same cell, reducing inference ambiguity. | CITE-seq, SHARE-seq, TEA-seq [22]. |

| Benchmarking Datasets & Pipelines | Validation Resource | Enables objective comparison of method performance on tasks like clustering, feature selection, and network recovery. | Simulated networks, curated gold-standard interactions (e.g., lac operon) [44], benchmark studies [22]. |

Visualizations: Workflows and Logical Relationships

Multi-Omics Network Integration Workflow

MINIE: Inferring Causal Cross-Omic Interactions

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative, minimally invasive tool in oncology, capable of detecting circulating biomarkers such as cell-free DNA (cfDNA), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and proteins. The evolution from analyzing single-omics biomarkers to integrating multi-omics data represents a paradigm shift, aiming to overcome the inherent limitations of any single analyte [46] [47]. This guide objectively compares the performance of single-omics versus multi-omics liquid biopsy approaches, framed within the broader thesis that integrated models provide superior clinical utility for early cancer detection and precise patient stratification [15] [48].

Performance Comparison of Single-Omics vs. Multi-Omics Approaches

The clinical performance of liquid biopsy biomarkers varies significantly based on the analyte type and the cancer stage. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, highlighting the complementary nature of different omics layers.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Single and Multi-Omics Liquid Biopsy Models

| Omics Approach | Biomarker Class | Study / Model | Sensitivity (Range/Overall) | Specificity | Key Application & Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Omics | ctDNA Mutations | DETECT-A Study | 27.5% (low in early stage) | 95.3% | Multi-cancer detection; Limited sensitivity for early-stage gynecological cancers. | [46] |

| Single-Omics | cfDNA Methylation | CCGA3 Study (Validation) | Ovary: 83.1%; Uterus: 80%; Cervix: 28% | 99.5% | Multi-cancer early detection (MCED); Tissue of Origin (TOO) accuracy varied (35%-91%). | [46] |

| Single-Omics | cfDNA Methylation | OvaPrint Classifier | 84.2% | 96% | Differentiating high-grade serous ovarian cancer from benign pelvic masses. | [46] |

| Single-Omics | Protein Markers | PERCEIVE-I (Protein Model) | Not explicitly stated; lower than methylation | Similar to methylation | Used eight serum tumor protein markers (e.g., CA125, HE4). | [46] |

| Single-Omics | cfDNA Methylation | PERCEIVE-I (Methylation Model) | 77.2% | 96.9% (similar to protein) | Gynecological cancer detection; outperformed protein and mutation models. | [46] |