Ensuring Data Integrity: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control Standards in Systems Biology

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control (QC) standards for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with systems biology data.

Ensuring Data Integrity: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control Standards in Systems Biology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control (QC) standards for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with systems biology data. It explores the foundational principles and critical need for robust QC frameworks to ensure data reproducibility and reliability. The content details practical, cross-platform methodologies for implementing QC in multi-omics workflows, including metabolomics and proteomics. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical stages. Finally, the guide covers validation techniques, comparative performance assessment, and the establishment of community standards for longitudinal data quality, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Role of Quality Control in Reproducible Systems Biology

Understanding the Reproducibility Challenge in Multi-Omics Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core reproducibility problem in multi-omics research? The core problem stems from the heterogeneity of data sources. Multi-omics studies combine data from various technologies (e.g., genomics, proteomics, metabolomics), each with its own unique data structure, statistical distribution, noise profile, and batch effects. Integrating these disparate data types without standardized pre-processing protocols introduces variability that challenges the reproducibility of results [1].

Why is sample quality so crucial for reproducibility? The quality of the starting biological sample directly determines the fitness-for-purpose of all downstream omics data. Variations in sample collection, processing, and storage can introduce significant technical artifacts that obscure the true biological signal. Participating in Proficiency Testing (PT) programs is a critical step to ensure sample processing methods yield accurate, reliable, and trustworthy data [2].

How can I choose the right data integration method? There is no universal framework, and the choice depends on your data and biological question [1]. The table below summarizes key methods:

| Method Name | Type | Key Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA [1] | Unsupervised | Identifies latent factors that capture shared and specific sources of variation across omics layers. | Exploring hidden structures without prior knowledge of sample groups. |

| DIABLO [1] | Supervised | Integrates datasets in relation to a known phenotype or category to identify biomarker panels. | Classifying patient groups or predicting clinical outcomes. |

| SNF [1] | Unsupervised | Fuses sample-similarity networks from each omics dataset into a single network. | Identifying disease subtypes based on multiple data types. |

| MCIA [1] | Unsupervised | Simultaneously projects multiple datasets into a shared dimensional space to find correlated patterns. | Jointly analyzing many omics datasets from the same samples. |

What are the key quality metrics for normalized multi-omics data? While standards are under development, quality control for normalized multi-omics profiles should assess the aggregated normalized data. This involves checking for batch effects, ensuring proper normalization across datasets, and confirming that the data quality reflects the overall proficiency of the study. The international standard ISO/TC 215/SC 1 is being developed to specify these procedures [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Findings Between Omics Layers

Symptoms: A strong signal is detected at the RNA level (transcriptomics) but is absent or weak at the protein level (proteomics), leading to conflicting biological interpretations [1].

Solutions:

- Understand Biological Hierarchy and Timing: Recognize that different omics layers have distinct dynamics.

- The genome is largely static and foundational [4].

- The transcriptome is highly dynamic and can change rapidly in response to stimuli, sometimes requiring frequent assessment [4].

- The proteome is more stable due to longer protein half-lives and often requires a lower testing frequency [4].

- The metabolome provides a real-time snapshot of metabolic activity and can be highly variable [4].

- Implement Longitudinal Sampling: For dynamic processes, design experiments with multiple time points to capture the temporal relationship between molecular events (e.g., gene expression changes followed by protein abundance changes) [4].

- Use Vertical Integration Methods: Apply integration algorithms like DIABLO or MCIA that are designed for matched multi-omics data (data from the same samples). These methods are powerful for finding associations between non-linear molecular modalities [1].

Problem: Poor Technical Reproducibility Across Batches or Labs

Symptoms: The same analysis yields different results when performed at different times, by different personnel, or in different laboratories.

Solutions:

- Utilize Reference Materials: Incorporate well-characterized reference materials into every experimental run to monitor data quality over time and detect batch effects. The table below lists key resources:

- Participate in Proficiency Testing (PT): Engage in external quality assessment (EQA) schemes, such as those established by the Integrated BioBank of Luxembourg (IBBL), to compare your lab's sample processing performance against peers and drive continuous improvement [2].

- Adopt Standardized Pre-Processing: Develop and adhere to Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for each omics data type, from raw data processing to normalization, to minimize variability introduced by analytical choices [1] [2].

Problem: Difficulty Interpreting Integrated Results

Symptoms: Statistical models successfully integrate data and identify patterns, but translating these patterns into biologically meaningful insights is challenging.

Solutions:

- Conduct Multi-Omics Pathway and Network Analysis: Move beyond individual molecule lists. Use network-based approaches to visualize how genes, proteins, and metabolites from your integrated results interact within known biological pathways. This provides a systems-level context [5].

- Validate Findings with Functional Assays: Treat computational predictions as hypotheses. Use targeted experiments (e.g., siRNA knockdown, ELISA, or targeted mass spectrometry) to confirm the biological role of key molecules or pathways identified through integration.

- Leverage Multiple Integration Methods: Confirm the robustness of your findings by running your data through more than one integration algorithm (e.g., both MOFA and SNF). Consistent results across methods increase confidence in your conclusions [1].

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Protocol: External Quality Assessment via Proficiency Testing

Purpose: To ensure the fitness-for-purpose of biospecimen processing methods for downstream omics analysis and to benchmark laboratory performance against reference labs [2].

Methodology:

- Enrollment: Enroll the laboratory in a relevant PT program (e.g., the biospecimen processing scheme by IBBL).

- Sample Processing: Process the provided PT samples according to the laboratory's standard SOPs.

- Result Submission: Submit the processing results to the PT program organizers.

- Performance Analysis: Receive a z-score, which quantifies how much your lab's results deviate from the expected value or consensus of other laboratories.

- Corrective Action: If z-scores indicate significant deviation, implement corrective measures (e.g., refine SOPs, retrain staff, calibrate equipment) to improve performance in subsequent PT rounds.

The following workflow visualizes this cyclical process of continuous quality improvement:

Protocol: Intra-Laboratory Quality Control Using Reference Materials

Purpose: To monitor and control the quality of data generated from a specific omics platform over time, detecting batch effects and technical drift [2].

Methodology:

- Selection: Choose a commercially available or community-accepted reference material (see "Research Reagent Solutions" table above) relevant to your omics platform.

- Integration: Include the reference material in every batch of sample processing and data generation.

- Data Extraction: For each batch, analyze the reference material data and extract key quality metrics (e.g., number of features identified, accuracy of quantitation for known amounts, detection of expected variants).

- Trend Monitoring: Track these metrics over time using control charts. Gradual deterioration or sudden shifts in the metrics indicate that corrective measures are needed.

- Benchmarking: Compare the metrics obtained from your reference material data against established benchmarks or values from other labs to ensure inter-laboratory consistency.

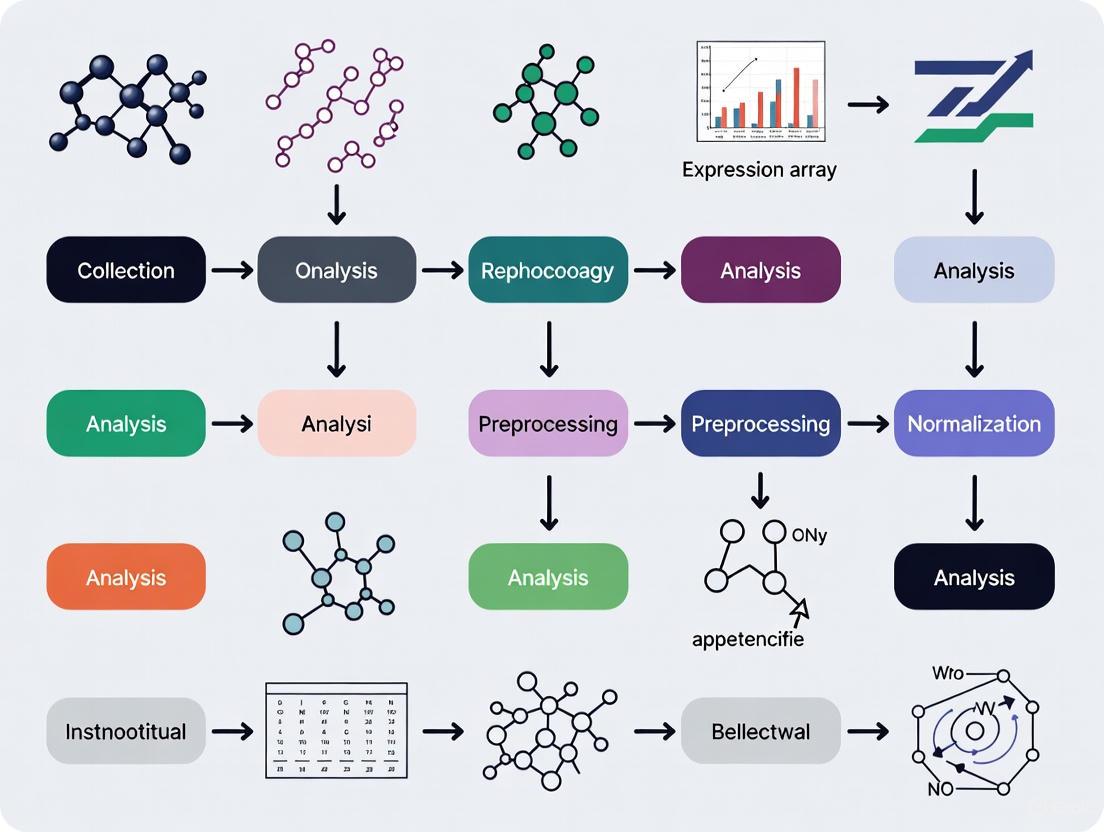

The Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for a reproducible multi-omics study, integrating the quality control measures and integration methods discussed. This workflow operates within the context of systems biology, aiming to understand the whole system rather than isolated parts [6].

Defining Quality Assurance (QA) vs. Quality Control (QC) in a Systems Context

In the data-intensive field of systems biology, where research relies on the integration of multiple heterogeneous datasets to model complex biological processes, a robust quality management system is not optional—it is essential for producing reliable, reproducible scientific insights [7]. Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC) are two fundamental components of this system. Though often used interchangeably, they represent distinct concepts with different focuses and applications. Quality Assurance (QA) is a proactive, process-oriented approach focused on preventing defects by building quality into the entire research data lifecycle, from experimental design to data analysis. In contrast, Quality Control (QC) is a reactive, product-oriented process focused on identifying defects in specific data outputs, models, or results through testing and inspection [8] [9] [10]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and implementing both QA and QC is critical for ensuring data integrity, research reproducibility, and regulatory compliance in systems biology.

Core Concepts: Distinguishing QA from QC

The table below summarizes the key distinctions between Quality Assurance and Quality Control in the context of systems biology research.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC)

| Feature | Quality Assurance (QA) | Quality Control (QC) |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Processes and systems | Final products and outputs |

| Goal | Defect prevention | Defect identification and correction |

| Nature | Proactive | Reactive |

| Approach | Process-oriented | Product-oriented |

| Primary Activity | Planning, auditing, documentation, training | Inspection, testing, validation |

| Timeline | Throughout the entire data lifecycle | At specific checkpoints on raw or processed data |

The relationship between these functions can be visualized as a continuous cycle ensuring data quality from start to finish.

Figure 1: The Integrated QA/QC Workflow. This diagram illustrates how proactive Quality Assurance and reactive Quality Control function together within a research data lifecycle, forming a cycle of continuous quality improvement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of systems biology experiments and subsequent quality control hinges on the use of specific reagents and materials. The following table details key resources and their functions in typical workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Experiments

| Item | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Cultrex Basement Membrane Extract | Provides a 3D scaffold for culturing organoids (e.g., human intestinal, liver, lung) to better mimic in vivo conditions [11]. |

| Methylcellulose-based Media | A semi-solid medium used in Colony Forming Cell (CFC) assays to support the growth and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells [11]. |

| DuoSet/Quantikine ELISA Kits | Tools for quantifying specific protein biomarkers (e.g., cytokines) in cell culture supernatants or patient samples with high specificity [11]. |

| Fluorogenic Peptide Substrates | Used in enzyme activity assays (e.g., for caspases or sulfotransferases); emission of fluorescence upon cleavage allows for kinetic measurement of enzyme activity [11]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Antibody cocktails for immunophenotyping, allowing simultaneous characterization of multiple cell surface and intracellular markers (e.g., for T-cell subsets) [11]. |

| Luminex xMAP Assay Kits | Enable multiplexed quantification of dozens of analytes (e.g., cytokines, phosphorylated receptors) from a single small-volume sample [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Data Quality Issues

Guide: Troubleshooting Poor Data Reproducibility

Problem: Inability to reproduce results from the same or similar datasets.

Question Flowchart:

Figure 2: Troubleshooting Poor Data Reproducibility

Guide: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Model Performance

Problem: Computational models yield inconsistent or unreliable predictions when applied to new data.

Question Flowchart:

Figure 3: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Model Performance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most significant challenge in bioinformatics QA today, and how can it be addressed? One of the most significant challenges is the volume and complexity of data, combined with the rapid evolution of technologies and methods [9]. High-throughput technologies can generate terabytes of data in a single experiment, making comprehensive QA time-consuming and computationally intensive. Furthermore, QA standards must continuously evolve to keep pace with new sequencing platforms and bioinformatics algorithms. Addressing this requires a focus on standardization and automation. Implementing standardized protocols and automated quality checks can significantly improve data reliability and reduce human error. The community is also moving toward AI-driven quality assessment and community-driven standards through initiatives like the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) to establish common frameworks [9].

Q2: How can I convince my team to invest more time in documentation, a key QA activity? Emphasize that documentation is not bureaucratic, but a crucial tool for efficiency and reproducibility. Well-documented workflows [12]:

- Save time in the long run by preventing the need to reverse-engineer past analyses.

- Enable collaboration by allowing team members to understand and build upon each other's work.

- Are essential for regulatory compliance in drug development, providing the evidence required by bodies like the FDA [9].

- Directly address the "reproducibility crisis," where studies show over 50% of researchers have failed to reproduce their own experiments [9].

Q3: Our QC checks sometimes fail after a "successful" experiment. Is our QA process failing? Not necessarily. A robust QA process is designed to minimize the rate of QC failures, but it cannot eliminate them entirely. A QC failure provides critical feedback. This is when your QA system for investigation kicks in. A key QA activity is managing a Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) system [13]. When QC fails, the QA process should guide you to investigate the root cause of the deviation and implement actions to prevent its recurrence. Thus, a QC failure is a valuable opportunity for continuous improvement, triggered by QC but addressed by QA.

Q4: What are the minimum QA/QC steps I should implement for a new sequencing-based project? At a minimum, your workflow should include:

- Raw Data QA: Assess base call quality scores (e.g., Phred scores), read length distributions, GC content, and adapter contamination using tools like FastQC [9].

- Processing Validation: Check alignment rates, mapping quality, and coverage depth/uniformity after alignment [9].

- Metadata & Provenance Tracking: Ensure complete and accurate metadata describing experimental conditions, using community standards where possible (e.g., MIAME for microarray data) [7]. Document all data transformation steps.

- Analysis Verification: Apply statistical measures (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals) and validate results with independent methods or replicates where feasible [9].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a QA/QC Workflow for Sequencing Data

Objective: To provide a detailed methodology for implementing a standardized Quality Assurance and Quality Control workflow for next-generation sequencing data within a systems biology project.

Background: Ensuring data integrity at the outset of a bioinformatics pipeline is critical for the validity of all downstream analyses and model building. This protocol outlines the key steps for QA and QC of raw and processed sequencing data.

Materials and Equipment:

- Raw sequencing data files (e.g., FASTQ format)

- High-performance computing (HPC) environment or server

- QA/QC software tools (e.g., FastQC, MultiQC)

- Reference genomes or transcripts (as required for the project)

- Data processing software (e.g., aligners like STAR or HISAT2)

Procedure:

Part A: Pre-analysis Quality Assurance (Proactive)

Define Quality Standards:

- Action: Prior to data generation, establish acceptance criteria for raw data. This includes minimum Phred quality scores (e.g., Q30), minimum read depth, maximum allowable adapter content, and maximum sequence duplication levels. Document these criteria in a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP).

- QA Rationale: This proactive step sets clear, objective benchmarks for data quality, preventing ambiguous judgments later [10].

Standardize Metadata:

- Action: Create a metadata spreadsheet using a structured format or controlled vocabulary (e.g., from the ISA-Tab framework or relevant minimum information checklist). Capture all experimental variables, sample information, and library preparation details.

- QA Rationale: Comprehensive and harmonized metadata is critical for data reuse, integration, and reproducibility, allowing others to understand the context of the data [7] [9].

Part B: Post-processing Quality Control (Reactive)

Assess Raw Data Quality:

- Action: Run FastQC on the raw FASTQ files from the sequencing run. Use MultiQC to aggregate and visualize results across all samples. Compare the results (e.g., per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination) against the pre-defined acceptance criteria from Part A.

- QC Rationale: This inspection identifies potential issues with the sequencing run or sample preparation that could compromise downstream analyses [9]. Data failing these criteria may need to be re-sequenced.

Validate Data Processing:

- Action: After alignment, collect and review key metrics. These include the overall alignment rate, the distribution of read mappings across genes/genome, and coverage uniformity. Compare these metrics across samples to identify outliers or batch effects.

- QC Rationale: These metrics verify the reliability of the alignment process and can reveal technical biases that need to be accounted for in the analysis [9].

Analysis and Interpretation:

- Any sample or dataset that fails to meet the pre-established quality thresholds must be flagged.

- The investigation into the root cause of the failure (e.g., sample degradation, library construction artifact) is a QA activity, often managed through a formal deviation or CAPA process [8].

- The final decision on whether to include, exclude, or re-process the data should be documented, providing an audit trail for the integrity of the research process.

The Impact of Pre-analytical Variables on Data Integrity

Troubleshooting Guides

A Systematic Approach to Pre-analytical Troubleshooting

Effective troubleshooting follows a logical progression from problem identification to solution implementation. This systematic approach minimizes experimental delays and preserves valuable samples [14].

Troubleshooting Steps Overview

| Step | Action | Key Questions to Ask |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the problem | What exactly is going wrong? Is the problem consistent? |

| 2 | List possible explanations | What are all potential causes? |

| 3 | Collect data | What do controls show? Were protocols followed? |

| 4 | Eliminate explanations | Which causes can be ruled out? |

| 5 | Experiment | How can remaining causes be tested? |

| 6 | Identify root cause | What is the definitive cause? |

Common Pre-analytical Scenarios and Solutions

Scenario 1: Inconsistent Biomarker Results in Multi-Site Trials

Problem: Variable results for the same analyte across different collection sites.

Troubleshooting Table

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Different tourniquet application times | Review phlebotomy procedures | Standardize to <1 minute application [15] |

| Variable centrifugation speeds | Audit equipment calibration | Implement calibrated centrifuges with logs |

| Inconsistent sample processing delays | Track sample processing times | Establish ≤2 hour processing window |

| Improper storage temperatures | Monitor storage equipment | Use continuous temperature monitoring |

Scenario 2: Degraded Nucleic Acids in Biobanked Samples

Problem: Poor RNA/DNA quality despite proper freezing.

Troubleshooting Table

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple freeze-thaw cycles | Review sample access logs | Create single-use aliquots [16] |

| Slow freezing rate | Monitor freezing protocols | Implement controlled-rate freezing |

| Improper storage temperature | Validate freezer performance | Maintain consistent -80°C with backups |

| Contamination during handling | Review aseptic techniques | Implement UV workstation sanitation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Sample Collection & Handling

Q1: How does tourniquet application time affect potassium measurements?

Prolonged tourniquet application with fist clenching can cause pseudohyperkalemia, increasing potassium levels by 1-2 mmol/L. Case studies show values as high as 6.9 mmol/L in outpatient settings dropping to 3.9-4.5 mmol/L when blood was drawn via indwelling catheter without tourniquet [15].

Q2: What is the minimum blood volume required for common testing panels?

| Test Type | Recommended Volume | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Chemistry (20 analytes) | 3-4 mL (heparin) 4-5 mL (serum) | Requires heparinized plasma or clotted blood [15] |

| Hematology | 2-3 mL (EDTA) | Adequate for complete blood count [15] |

| Coagulation | 2-3 mL (citrated) | Sufficient for standard coagulation tests [15] |

| Immunoassays | 1 mL | Can perform 3-4 different immunoassays [15] |

| Blood Gases (capillary) | 50 μL | Arterial blood for capillary sampling [15] |

Q3: Why do platelet counts affect potassium results?

During centrifugation and clotting, platelets can release potassium, causing falsely elevated serum levels. Whole blood potassium measurements provide accurate results, as demonstrated in a case where serum potassium was 8.0 mmol/L but whole blood was 2.7 mmol/L in a patient with thrombocytosis [15].

Sample Processing & Storage

Q4: How do multiple freeze-thaw cycles impact sample integrity?

Repeated freezing and thawing degrades proteins, nucleic acids, and labile metabolites. Each cycle causes:

- Protein denaturation and aggregation

- RNA fragmentation

- Loss of enzymatic activity

- Metabolic profile changes

Best practice: Create single-use aliquots during initial processing [16].

Q5: What quality indicators detect pre-analytical errors?

| Indicator | Target | Acceptable Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Sample hemolysis | <2% of samples | Varies by analyte [15] |

| Incorrect sample volume | <1% of samples | Per collection protocol [15] |

| Processing delays | <5% of samples | Within established windows [16] |

| Mislabeled samples | <0.1% of samples | Zero tolerance ideal [17] |

Data Integrity & Documentation

Q6: What documentation ensures pre-analytical data integrity?

The ALCOA+ framework provides comprehensive standards:

- Attributable: Who collected and processed the sample

- Legible: Permanent, readable records

- Contemporaneous: Recorded at time of activity

- Original: Primary records preserved

- Accurate: Error-free documentation

- Complete: All data including metadata

- Consistent: Sequential, dated records

- Enduring: Long-term preservation

- Available: Accessible for review [18]

Q7: How can I validate my pre-analytical workflow?

Implement these verification steps:

- Process Mapping: Document each step from collection to analysis

- Control Samples: Use standardized controls at each stage

- Periodic Audits: Review documentation and sample quality

- Equipment Monitoring: Log storage conditions and centrifuge calibration

- Staff Training: Regular competency assessments [19] [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Pre-analytical Quality Control

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA Tubes | Preserves cell morphology for hematology | 2-3 mL volume adequate for hematology tests [15] |

| Sodium Citrate Tubes | Maintains coagulation factors | 2-3 mL sufficient for coagulation tests [15] |

| Heparin Tubes | Inhibits clotting for chemistry tests | 3-4 mL needed for 20 chemistry analytes [15] |

| Serum Separator Tubes | Provides clean serum for testing | 4-5 mL of clotted blood required [15] |

| PAXgene Tubes | Stabilizes RNA for molecular studies | Prevents RNA degradation during storage [16] |

| Temperature Loggers | Monitors storage conditions | Continuous monitoring with alarms [16] |

| Hemolysis Index Controls | Detects sample hemolysis | Visual assessment insufficient; quantitative needed [15] |

Data Integrity Framework Diagram

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary goals of the mQACC and the Metabolomics Society's Data Quality Task Group?

The Metabolomics Quality Assurance and Quality Control Consortium (mQACC) is a collaborative international effort dedicated to promoting the development, dissemination, and harmonization of best quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) practices in untargeted metabolomics. Its mission is to engage the metabolomics community to ensure data quality and reproducibility [20]. Key aims include identifying and cataloging QA/QC best practices, establishing mechanisms for the community to adopt them, promoting systematic training, and encouraging the development of applicable reference materials [20]. While the search results do not explicitly list a "Data Quality Task Group" (DQTG), the Metabolomics Society hosts several relevant Scientific Task Groups, such as the Data Standards Task Group and the Metabolite Identification Task Group, which focus on enabling efficient data formats, storage, and consensus on reporting standards to improve data quality and verification [21].

Q2: I am designing a large-scale LC-MS metabolomics study. What are the critical QA/QC steps I should integrate into my workflow?

For large-scale LC-MS studies, robust QA/QC is essential to manage technical variability and ensure data integrity. Key steps and considerations are detailed below.

- Pooled Quality Control (QC) Samples: Incorporate pooled QC samples throughout your analytical sequence. These are typically prepared by combining a small aliquot of all study samples and are injected repeatedly at the beginning for system conditioning and at regular intervals during the run. They are crucial for monitoring instrument stability, correcting for analytical drift, and assessing data quality [22] [23].

- Comprehensive Internal Standards (IS): Use a mixture of stable, isotopically labeled internal standards that cover a wide range of chemical classes and retention times. This helps monitor instrument performance and extraction efficiency. Note that in untargeted metabolomics, their use for direct signal correction may be limited due to potential matrix effects [22].

- Batch Design and Normalization: When analyzing hundreds of samples across multiple batches, careful batch design with randomized sample injection is critical. Systematic errors between batches must be corrected using post-acquisition normalization algorithms that rely on data from the pooled QC samples [22].

- Reference Materials (RMs): Utilize available reference materials (RMs) for process verification. These can include certified reference materials (CRMs), synthetic mixtures, or other standardized materials to help validate your analytical pipeline and enable cross-laboratory comparisons [23].

Q3: A reviewer has asked for evidence that our metabolomics data is of high quality. What should we report in our publication?

Engaging with journals to define reporting standards is a core objective of mQACC [24]. You should provide a detailed description of the QA/QC practices and procedures applied throughout your study. The Reporting Standards Working Group of mQACC is actively developing guidelines for this purpose. Key items to report include [24]:

- A clear description of the QC samples used (e.g., pooled QC, process blanks) and their preparation.

- The frequency and pattern of QC sample injection throughout the analytical sequence.

- The type and number of internal standards used.

- How the data derived from QC samples were analyzed, assessed, and interpreted to ensure acceptance criteria were met (e.g., intensity drift, retention time stability, missing data).

- The normalization and correction procedures applied to the data based on QC information.

Q4: Our laboratory is new to metabolomics. Where can we find established best practices for quality management?

The mQACC consortium is an excellent central resource. Its Best Practices Working Group is specifically tasked with identifying, cataloging, harmonizing, and disseminating QA/QC best practices for untargeted metabolomics [24]. This group conducts community workshops and literature surveys to define areas of common agreement and publishes living guidance documents [24]. Furthermore, the Metabolomics Society provides a hub for education and collaboration, with task groups focused on specific data quality challenges, such as metabolite identification and data standards [25] [21].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Signal drift or drop in instrument response during a large-scale LC-MS sequence.

- Potential Causes: Gradual contamination of the ionization source, depletion of mobile phases, or column degradation over many injections [22].

- Solutions:

- Pre-sequence Preparation: Prepare large, single batches of mobile phase (e.g., 5L) to avoid variability during the run [22].

- Regular QC Monitoring: Use a sequence design that interlaces pooled QC samples every 5-10 experimental samples. Plot the feature intensities or total signal from these QCs to visualize and quantify drift [22] [26].

- Data Normalization: Apply post-acquisition correction algorithms (e.g., QC-SVRC, LOESS signal correction) using the data from the pooled QC samples to mathematically compensate for the observed signal drift [22].

Problem: High variability or failure of results in inter-laboratory comparisons.

- Potential Cause: A lack of standardized protocols and common reference materials leads to inconsistencies between platforms and laboratories [23].

- Solutions:

- Adopt Reference Materials (RMs): Integrate commercially available or community-developed RMs into your workflow. These materials act as a common benchmark to validate performance across different laboratories and instruments [23].

- Implement SOPs: Develop and adhere to detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for sample preparation, instrumentation, and data processing to ensure consistency [9] [23].

- Community Engagement: Participate in interlaboratory studies and follow the guidelines being established by groups like the mQACC Reference Materials Working Group, which is actively working to define best-use practices for these materials [24] [23].

Problem: Difficulty in confidently identifying metabolites detected in an untargeted analysis.

- Potential Cause: Insufficient data or context provided in public repositories and publications to support metabolite annotation claims.

- Solutions:

- Follow Reporting Standards: Adhere to the metabolite identification reporting standards being developed by the Metabolite Identification Task Group of the Metabolomics Society. This ensures you report the necessary evidence (e.g., MS/MS spectrum, retention time) for different levels of confidence [21].

- Use Controlled Vocabularies: Engage with the MetFAIR Task Group, which focuses on improving the reproducible reporting of metabolite annotations using controlled vocabularies and structural identifiers, facilitating better data sharing and integration [21].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a QC Framework for an LC-MS Metabolomics Study

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for integrating a robust QA/QC system into a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) based untargeted metabolomics study, based on community best practices [24] [22] [23].

Sample Preparation and Experimental Design

- Sample Randomization: Randomize the injection order of all study samples to avoid confounding biological effects with batch effects.

- Pooled QC (PQC) Preparation: Create a pooled quality control sample by combining a small, equal volume from every individual sample in the study. If the cohort is extremely large, a representative subset of samples can be used to create the PQC [22].

- Internal Standard (IS) Mixture: Add a mixture of isotopically labeled internal standards to every sample (including blanks and QCs) prior to protein precipitation or extraction. Select standards to cover a broad range of chemical classes and retention times (e.g., labeled amino acids, carnitines, lipids, fatty acids) [22].

Instrumental Sequence Setup and Data Acquisition

- Sequence Structure: Structure the LC-MS sequence as follows:

- Conditioning: Start with several injections of the PQC to condition the system.

- Blank: Run a solvent blank to identify background signals.

- Balancing: Use a block-randomized design to balance sample groups across the sequence.

- QC Frequency: Inject the PQC sample repeatedly after every 5-10 experimental samples throughout the entire sequence to monitor performance [22].

- Reference Material: Include a well-characterized reference material (RM) at the beginning and end of the sequence, or in a separate quality audit run, to assess overall method and instrument performance against a known standard [23].

Data Processing and Quality Assessment

- Quality Metrics Calculation: After processing raw data, calculate the following metrics from the PQC samples:

- Feature-wise Relative Standard Deviation (RSD): Determine the percentage of metabolic features in the PQC with an RSD below 20% or 30%. A high number of low-RSD features indicates good analytical precision.

- Retention Time Drift: Measure the stability of retention times for internal standards and endogenous features in the PQC.

- Total Signal Intensity: Track the overall signal response in the PQC over the sequence to identify global drift.

- Data Normalization: Apply a quality control-based normalization method (e.g., using the

pqnmethod in R, or LOESS regression based on PQC samples) to correct for systematic signal drift identified in the sequence [22].

The logical workflow for this protocol, from preparation to assessment, is designed to systematically control for technical variability.

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomics QC

The table below details key materials essential for implementing a robust quality control system in metabolomics, as championed by mQACC and related initiatives.

| Item | Function & Application in QA/QC |

|---|---|

| Pooled Quality Control (PQC) Sample | A pooled aliquot of all study samples. Injected repeatedly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument stability, correct for signal drift, and assess the precision of metabolic feature measurements [22] [23]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled compounds (e.g., with ²H, ¹³C) not naturally found in the sample. Added to all samples to monitor instrument performance, extraction efficiency, and matrix effects. They should cover a wide range of the metabolome [22]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Highly characterized materials with a certificate of analysis. Used to validate analytical methods, assess accuracy, and enable cross-laboratory comparability of results [23]. |

| Long-Term Reference (LTR) QC | A stable, study-independent QC material (e.g., a commercial surrogate or a large pooled sample) analyzed over long periods across multiple studies to track laboratory performance and ensure consistency over time [23]. |

| Process Blanks | Samples containing only the extraction solvents and reagents. Used to identify and filter out background signals and contaminants originating from the sample preparation process or solvents [22]. |

The 'FAIR' Guiding Principles for Systems Biology Data Management

The FAIR Guiding Principles are a set of four foundational principles—Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability—designed to improve the management and stewardship of scientific data and other digital research objects, including algorithms, tools, and workflows [27]. Originally published in 2016 by a diverse group of stakeholders from academia, industry, funding agencies, and scholarly publishers, these principles provide a concise and measurable framework to enhance the reuse of data holdings [27] [28].

A key differentiator of the FAIR principles is their specific emphasis on enhancing the ability of machines to automatically find and use data, in addition to supporting its reuse by human researchers [27] [29]. This machine-actionability is critical in data-rich fields like systems biology, where the volume, complexity, and speed of data creation exceed human capacity for manual processing.

The following table summarizes the core objectives of each FAIR principle.

| FAIR Principle | Core Objective | Key Significance for Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | Data and metadata are easy to find for both humans and computers. | Enables discovery of datasets across departments and collaborators, laying the groundwork for efficient knowledge reuse [29] [28]. |

| Accessible | Data can be retrieved by users using standard protocols, with clear authentication and authorization where necessary. | Supports implementing infrastructure for controlled data access at scale, ensuring security and compliance [29] [28]. |

| Interoperable | Data can be integrated with other data and used with applications or workflows for analysis. | Vital for multi-modal research, allowing integration of diverse datasets (e.g., genomic, imaging, clinical) [29] [28]. |

| Reusable | Data and metadata are well-described so they can be replicated or combined in different settings. | Maximizes the utility and impact of datasets for future research, ensuring reproducibility [29] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing FAIR in a Systems Biology Workflow

This section provides a detailed methodology for applying the FAIR principles to a typical systems biology experiment involving multi-omics data integration.

Protocol: FAIRification of a Multi-Omics Dataset

Aim: To manage a dataset comprising transcriptomic and proteomic profiles from a drug perturbation study in a FAIR manner to ensure its future discoverability and utility.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: HEK293 (or other relevant model system)

- Perturbation Agent: Small molecule drug candidate (e.g., a kinase inhibitor)

- RNA Extraction Kit: (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy Kit)

- Protein Lysis Buffer: RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Next-Generation Sequencing Platform: (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) for RNA-seq

- Mass Spectrometer: (e.g., Thermo Fisher Orbitrap Exploris) for quantitative proteomics

Methodology:

- Experimental Design and Metadata Planning:

- Before data generation, define the minimum reporting standards required for your data types (e.g., MIAME for transcriptomics, MIAPE for proteomics).

- Create a data dictionary using community-standard ontologies (e.g., EDAM for data types, UO for units, NCBI Taxonomy for organisms).

Data Generation and Curation:

- Generate raw data (e.g., FASTQ files for RNA-seq, .raw files for proteomics).

- Process raw data through established pipelines (e.g., RNA-seq alignment with STAR, proteomics identification with MaxQuant). Record all software versions and parameters.

- Derive processed data (e.g., gene count matrices, protein abundance values).

Assignment of Persistent Identifiers:

- Obtain a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) for the overall dataset from a repository like Zenodo or your institutional repository.

- For individual data files and components, use universally unique identifiers (UUIDs).

Metadata Annotation and Rich Description:

- Describe the dataset with rich metadata, including:

- Project Title, Description, and Funding Source.

- Creator and ORCID IDs.

- Keywords from ontologies like MeSH or EDAM.

- Detailed methodology linking to this protocol.

- Data Access and License Information (e.g., CCO 1.0 Universal for public domain, or a custom license for restricted access).

- Describe the dataset with rich metadata, including:

Data Deposition in a Public Repository:

- Deposit the data in a recognized, community-accepted repository.

- Recommended Repositories:

- Omics Discovery Index (OmicsDI): A cross-domain resource.

- ArrayExpress or GEO for transcriptomics data.

- PRIDE for proteomics data.

Provenance Tracking:

- Use a workflow management system (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake) that automatically captures the provenance of all data transformations, from raw data to final results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and their functions in the context of generating and managing FAIR systems biology data.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Role in FAIR Data Management |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Barcoding Kits | Enables multiplexing of samples during high-throughput sequencing or mass spectrometry. | Provides a traceable link between a physical sample and its digital data file, supporting Reusability through clear sample provenance [27]. |

| Stable Cell Lines | Provides a consistent and reproducible biological model for perturbation studies. | Reduces experimental variability, ensuring data is Reusable and reproducible by other researchers [28]. |

| Standardized Buffers & Kits | Ensures consistency in sample preparation (e.g., lysis, nucleic acid extraction) across experiments and labs. | Promotes Interoperability by minimizing technical artifacts that would prevent data integration from different batches or studies [28]. |

| Controlled Vocabularies & Ontologies | A set of standardized terms (e.g., Gene Ontology, Cell Ontology) for annotating data. | Critical for Findability and Interoperability, as it allows machines to accurately understand and link related data concepts [27] [28]. |

| Persistent Identifier Services | A service (e.g., DataCite, DOI) that assigns a permanent, globally unique identifier to a dataset. | The cornerstone of Findability, ensuring the dataset can always be located and cited, even if its web URL changes [29] [28]. |

FAIR Data Management: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Our data is confidential. Can it still be FAIR? Answer: Yes. FAIR is not synonymous with "open." Data can be Accessible only under specific conditions, such as behind a secure authentication and authorization layer [28]. The key is that the metadata should be openly findable, describing the data's existence and how to request access. The path to access should be clear, even if the data itself is restricted.

FAQ 2: We have legacy data from past projects that lacks rich metadata. Is it too late to make it FAIR? Answer: It is not too late, but it can be a challenge. A practical approach is to perform a "FAIRification" process [28]:

- Inventory: Catalog all existing datasets.

- Annotate: Manually or semi-automatically enrich the data with as much metadata as possible using current standards.

- Identify: Assign persistent identifiers (e.g., DOIs) to the curated datasets.

- Deposit: Store the enhanced datasets and metadata in a suitable repository. While time-consuming, this process maximizes the return on investment from past research [28].

FAQ 3: What is the most common mistake in trying to be FAIR? Answer: A common mistake is focusing only on the human-readable aspects of data and neglecting machine-actionability. This includes using PDFs for data tables (which are difficult for machines to parse), free-text fields without controlled vocabulary, or failing to use resolvable, persistent identifiers. The FAIR principles require data to be not just human-understandable, but also machine-processable [27] [29].

FAQ 4: How do FAIR principles support AI and machine learning in drug discovery? Answer: FAIR data provides the foundational layer required for effective AI. AI and ML models require large volumes of well-structured, high-quality data. By making data Interoperable and Reusable, FAIR principles allow for the harmonization of diverse data types (genomics, imaging, EHRs), creating the large, integrated datasets needed to train robust models. This accelerates target identification and biomarker discovery [28].

Visualization of FAIR Workflows and Relationships

Implementing Robust QC Frameworks Across Omics Technologies

In systems biology research, ensuring the integrity and reliability of data is paramount. Quality Control (QC) samples are essential tools that provide confidence in analytical results, from untargeted metabolomics to genomic studies. These samples help researchers distinguish true biological variation from technical noise, a critical consideration for drug development professionals who rely on this data for decision-making. The overarching goal of implementing a robust QC protocol is to ensure research reproducibility, a fundamental challenge in modern science where a significant percentage of researchers have reported difficulties in reproducing experiments [9].

Quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) represent complementary components of quality management. According to accepted definitions, quality assurance comprises the proactive processes and practices implemented before and during data acquisition to provide confidence that quality requirements will be fulfilled. In contrast, quality control refers to the specific measures applied during and after data acquisition to confirm that these quality requirements have been met [30]. For systems biology data research, this distinction is crucial in building a comprehensive framework for data quality.

Core QC Sample Types and Their Applications

Defining the Fundamental QC Samples

Effective QC strategies in systems biology incorporate several types of reference samples, each serving a distinct purpose in monitoring and validating analytical performance.

Pooled QC Samples: Created by combining equal aliquots from all study samples, pooled QCs represent the "average" sample composition in a study. When analyzed repeatedly throughout the analytical sequence, they monitor system stability and performance over time, helping to identify technical drift, batch effects, and variance among replicates [30] [9].

Blank Samples: These samples contain all components except the analyte of interest, typically using the same solvent as the sample reconstitution solution. Blanks are essential for identifying carryover from previous injections, contaminants in solvents or reagents, and system artifacts such as column bleed or plasticizer leaching [30] [31].

Standard Reference Materials (SRMs): These are well-characterized samples with known properties and concentrations, often obtained from certified sources like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). SRMs serve as validation tools for bioinformatics pipelines, allowing researchers to identify systematic errors or biases in data processing and analysis workflows [9].

Quantitative Metrics for QC Sample Assessment

Table 1: Key Quality Metrics for Different Analytical Platforms in Systems Biology

| Analytical Platform | QC Sample Type | Key Metrics | Acceptance Criteria Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Pooled QC, SRMs | Base call quality scores (Phred), read length distributions, alignment rates, coverage depth and uniformity | Phred score > Q30, alignment rates > 90%, coverage uniformity across targets |

| Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics | Pooled QC, Blanks, SRMs | Retention time stability, peak intensity variance, mass accuracy, signal-to-noise ratio | <30% RSD for peak intensities in pooled QCs, mass accuracy < 5 ppm |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Pooled QC, SRMs | Spectral line width, signal-to-noise ratio, chemical shift stability, resolution | Line width consistency, chemical shift deviation < 0.01 ppm |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common QC Sample Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Investigation Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deteriorating Signal in Pooled QCs | Column degradation, source contamination, reagent instability | Check system suitability tests, analyze SRMs, review QC charts | Clean ion source, replace column, refresh mobile phases |

| Contamination in Blank Samples | Carryover, solvent impurities, vial contaminants | Run blank injections, check autosampler cleaning protocol, test different solvent batches | Implement rigorous wash protocols, use high-purity solvents, replace vial types |

| Shift in Reference Material Values | Calibration drift, method modification, instrumental variance | Compare with historical data, run independent validation, check calibration standards | Recalibrate system, verify method parameters, service instrument |

Implementation and Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions on QC Sample Implementation

Q1: How should pooled QC samples be prepared and implemented throughout an analytical sequence?

Pooled QC samples should be prepared by combining equal aliquots from a representative subset of all study samples (typically 10-50μL from each) to create a homogeneous pool that reflects the average composition of your sample set. This pooled QC should be analyzed at regular intervals throughout the analytical sequence—typically at the beginning, after every 4-10 experimental samples, and at the end of the batch. The frequency should be increased for less stable analytical platforms or longer sequences. The results from these repeated injections are used to monitor system stability and performance over time [30].

Q2: What is the most effective approach when QC results indicate an out-of-control situation?

The worst habits when encountering QC failures are automatically repeating the control or testing a new vial of control material without systematic investigation. These approaches often resolve the problem temporarily without identifying the root cause. Instead, implement a structured troubleshooting approach: first, clearly define the deviation by comparing current results with established acceptance criteria and historical data. Then, systematically investigate potential sources—check sample preparation steps, mobile phase composition, instrument performance, and column integrity. Make one change at a time while testing to identify the true cause. Frequent recalibration should also be avoided as it can introduce new systematic errors without addressing underlying issues [32] [31].

Q3: How can ghost peaks or unexpected signals in blank samples be resolved?

Ghost peaks in blanks typically originate from several sources: carryover from previous injections, contaminants in mobile phases or solvents, column bleed, or system hardware contamination. To resolve these issues: run blank injections to characterize the ghost peaks; perform intensive autosampler cleaning including the injection needle and loop; prepare fresh mobile phases with high-purity solvents; and consider replacing or cleaning the column if bleed is suspected. Using a guard column or in-line filter can help capture contaminants early and protect the analytical column [31].

Q4: What are the key considerations for incorporating Standard Reference Materials into QC protocols?

Standard Reference Materials should be selected to match the analytes of interest and matrix composition as closely as possible. They should be analyzed at the beginning of a study to validate analytical methods and periodically throughout to monitor long-term performance. When using SRMs, it's critical to: document the source and lot numbers; prepare SRMs according to certificate instructions; track performance against established tolerance limits; and investigate any deviations from expected values. SRMs are particularly valuable for technology transfer between laboratories and for verifying method performance when implementing new protocols [9].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Comprehensive QC Strategy for Untargeted Metabolomics

Objective: To establish a robust QC system for an untargeted metabolomics study using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Materials Needed:

- Test samples for analysis

- Appropriate solvents for extraction and reconstitution

- Vials for sample collection and storage

- Internal standards

- Certified reference materials for key metabolites

- Quality control materials

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare experimental samples using standardized extraction protocols.

- Create a pooled QC sample by combining equal aliquots (e.g., 10-20 μL) from each experimental sample.

- Prepare blank samples using the same solvent as for sample reconstitution.

- Prepare standard reference materials according to certificate instructions.

Sequence Design:

- Begin sequence with system equilibration injections (4-6 injections of pooled QC).

- Analyze blank samples to establish background signals.

- Analyze standard reference materials to validate method performance.

- Implement a randomized sample sequence with pooled QC samples inserted every 4-8 experimental samples.

- Include procedural blanks at regular intervals to monitor contamination.

- Conclude sequence with additional pooled QC and reference material analyses.

Data Acquisition and Monitoring:

- Monitor retention time stability for internal standards and reference materials.

- Track peak intensity variance in pooled QC samples (typically <20-30% RSD).

- Assess mass accuracy against theoretical values for reference compounds.

- Evaluate chromatographic peak shape and symmetry.

Quality Assessment:

- Calculate coefficient of variation for features detected in pooled QC samples.

- Perform principal component analysis on pooled QC samples to identify outliers.

- Compare measured values for reference materials against certified ranges.

- Document all quality metrics and any deviations from acceptance criteria.

Troubleshooting Note: If pooled QC samples show progressive deterioration in signal intensity or retention time shifts, consider column aging, source contamination, or mobile phase degradation as potential causes. Implement appropriate maintenance procedures before continuing with sample analysis [30] [31].

Workflow Visualization and Reagent Solutions

QC Sample Implementation Workflow

QC Troubleshooting Pathway

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QC Protocols

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Quality Control Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in QC Protocol | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides ground truth for method validation and calibration | NIST Standard Reference Materials, certified metabolite standards |

| Internal Standard Mix | Corrects for instrument variability and sample preparation losses | Stable isotope-labeled analogs of target analytes |

| High-Purity Solvents | Minimize background interference and contamination | LC-MS grade water, acetonitrile, methanol |

| Quality Control Pooled Plasma | Assesses analytical performance across multiple batches | Commercially available human pooled plasma from certified vendors |

| System Suitability Test Mix | Verifies instrument performance before sample analysis | Compounds with known retention and response characteristics |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Maintains consistent chromatographic performance | Mass spectrometry-grade acids, buffers, and ion-pairing reagents |

Implementing robust QC samples aligns with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) that are increasingly important in systems biology research [33]. Proper documentation of QC protocols, including preparation methods, acceptance criteria, and results, ensures that data meets quality standards for regulatory submissions and collaborative research. As bioinformatics continues to evolve with AI-driven quality assessment and community-driven standards, the fundamental role of pooled QCs, blanks, and standard reference materials remains critical for producing trustworthy scientific insights in drug development and biological research [9]. By adhering to these best practices for QC sample design and implementation, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their systems biology data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My RNA-seq data fails the "sequence quality" check in the quality control report. The per-base sequence quality is low at the 3' end of the reads. What does this mean, and what should I do?

A1: Low quality at the 3' end of reads is a common issue often caused by degradation of RNA samples or issues with the sequencing chemistry. You should:

- Check RNA Integrity: Verify the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of your original sample. A RIN below 7 may indicate degradation.

- Trimming: Use a quality control tool like FastQC to generate the report and a trimming tool like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases from the ends of the sequences. This prevents errors in downstream analysis like alignment or transcript assembly [34].

Q2: After aligning my sequencing data to a reference genome, the alignment rate is unexpectedly low. What are the potential causes and solutions?

A2: A low alignment rate can stem from several factors. Follow this structured approach to isolate the issue [35] [36]:

- Verify Reference Genome: Ensure you are using the correct reference genome build and that it is not contaminated.

- Check Sample Identity: Confirm that your sequencing data is from the same species as the reference genome. Cross-species contamination can cause low alignment.

- Inspect Quality Scores: Re-examine your initial quality control metrics. High levels of adapter contamination or poor sequence quality will lower alignment rates. Trim the data if necessary.

- Try a Different Aligner: Test with a different alignment tool (e.g., if using STAR, try HISAT2) to rule out tool-specific issues [34].

Q3: During the variant calling workflow, my tool outputs an error about "incorrect file format." How can I troubleshoot this?

A3: Bioinformatics tools are often specific about their input file formats and versions.

- Validate File Format: Use a tool like SAMtools to check the integrity and format of your input file (e.g., BAM file) [34].

- Check File Versions: Ensure all files in your pipeline are from compatible versions. For example, an older version of a BAM file might not be compatible with a newer variant caller.

- Consult Documentation: Refer to the documentation of the specific tool generating the error. It will often list exact format requirements. Reproducible workflow platforms like nf-core provide version-controlled pipelines that help avoid these compatibility issues [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Data Quality in Sequencing Experiments

Problem: Quality control tools (e.g., FastQC) report poor per-base sequence quality, high adapter contamination, or overrepresented sequences.

Resolution Process:

- Understand the Problem: Run FastQC on your raw FASTQ files to identify the specific quality issues [34].

- Isolate the Issue [35] [36]:

- Poor Quality Scores: If quality drops at the ends, it is likely a sequencing chemistry issue. If the drop is uniform, the sample may be degraded.

- Adapter Contamination: This indicates that the library preparation did not efficiently remove adapter sequences.

- Overrepresented Sequences: This can point to contamination (e.g., ribosomal RNA, vector sequence) or a low-diversity library.

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

- For poor quality and adapter contamination, use a trimming tool. The table below summarizes common QC metrics and their implications [34].

- For overrepresented sequences, you may need to remove the contaminated reads or, if the issue is severe, re-prepare the library.

Table 1: Common Sequencing Data Quality Issues and Solutions

| QC Metric | Problematic Output | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per-base Sequence Quality | Low scores (Q<20) at read ends | Sequencing chemistry; degraded RNA | Trim reads using Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [34] |

| Adapter Content | High adapter sequence percentage | Inefficient adapter removal during library prep | Trim adapter sequences [34] |

| Overrepresented Sequences | A few sequences make up a large fraction of data | Sample contamination or low library complexity | Identify sequences via BLAST; redesign experiment if severe |

| Per-sequence GC Content | Abnormal distribution compared to reference | General contamination or PCR bias | Investigate sample purity and library preparation steps |

Guide 2: Resolving Workflow and Code Generation Errors

Problem: A bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., a Snakemake or Nextflow script) fails to execute, or a custom script for analysis does not produce the expected output.

Resolution Process:

- Understand the Problem [36]:

- Read the Error Message: Copy the exact error message from the terminal or log file.

- Check the Logs: Most workflow tools and scripts generate detailed logs. Look for warnings or errors that precede the final failure.

- Isolate the Issue [35]:

- Reproduce the Issue: Run the failing command or script in a minimal, clean environment (e.g., a new container) to rule out environment-specific problems.

- Simplify the Problem: If a complex script is failing, comment out sections and run it step-by-step to identify the exact failing command.

- Check Dependencies: Verify that all required software, packages, and libraries are installed and are the correct versions. Using containerized environments like Biocontainers can prevent dependency conflicts [34].

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

- Search for Similar Issues: Look up the error message in bioinformatics forums like Biostars or the software's GitHub repository [34].

- Consult Reproducible Workflows: Refer to established, version-controlled workflows from repositories like nf-core for examples of correctly implemented steps [34].

- Implement a Fix: Based on your research, apply the fix, which could involve updating a tool, changing a file path, or correcting a syntax error in your code.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quality Control and Trimming of Raw Sequencing Reads

Objective: To assess the quality of raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) and remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences to ensure robust downstream analysis.

Methodology:

- Quality Assessment:

- Run FastQC on your raw FASTQ files to generate a comprehensive quality report.

- Examine the HTML output for issues detailed in Table 1.

- Trimming and Cleaning:

- Use Trimmomatic (for Illumina data) to perform the following:

- Remove Illumina adapter sequences.

- Trim leading and trailing low-quality bases (below quality score 3).

- Scan the read with a 4-base wide sliding window and cut when the average quality per base drops below 20.

- Drop reads that are shorter than 36 bases after trimming.

- Example command:

java -jar trimmomatic.jar PE -phred33 input_forward.fq.gz input_reverse.fq.gz output_forward_paired.fq.gz output_forward_unpaired.fq.gz output_reverse_paired.fq.gz output_reverse_unpaired.fq.gz ILLUMINACLIP:adapters.fa:2:30:10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20 MINLEN:36

- Use Trimmomatic (for Illumina data) to perform the following:

- Post-Trimming Quality Assessment:

- Run FastQC again on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm that quality issues have been resolved.

Protocol 2: Alignment of RNA-seq Data to a Reference Genome

Objective: To accurately map high-quality, trimmed RNA-seq reads to a reference genome for subsequent transcript assembly and quantification.

Methodology:

- Tool Selection: Select an appropriate aligner. For RNA-seq data, splice-aware aligners are required. STAR is recommended for its high accuracy and speed [34].

- Generate Genome Index:

- First, the reference genome must be indexed. This is a one-time step for each genome/annotation combination.

- Example STAR command for genome indexing:

STAR --runMode genomeGenerate --genomeDir /path/to/genomeDir --genomeFastaFiles reference_genome.fa --sjdbGTFfile annotation.gtf --sjdbOverhang 99

- Align Reads:

- Run the alignment using the indexed genome and the trimmed FASTQ files.

- Example STAR command for alignment:

STAR --genomeDir /path/to/genomeDir --readFilesIn output_forward_paired.fq.gz output_reverse_paired.fq.gz --readFilesCommand zcat --outFileNamePrefix aligned_output --outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate --quantMode GeneCounts

- Post-Alignment QC:

- Use tools like SAMtools to index the resulting BAM file and generate alignment statistics.

- Use Qualimap to perform a more detailed RNA-seq QC on the BAM file, checking for genomic coverage and bias.

Workflow Visualization

Multi-Step QC Protocol

Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for a Sequencing QC Workflow

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA Sample | The starting material; its integrity (RIN > 7) is critical for generating high-quality sequencing libraries and avoiding 3' bias. |

| Library Preparation Kit | A commercial kit (e.g., Illumina TruSeq) containing enzymes and buffers to convert RNA into a sequenceable library, including adapter ligation. |

| Trimmomatic | A flexible software tool used to trim adapters and remove low-quality bases from raw FASTQ files, cleaning the data for downstream analysis [34]. |

| STAR Aligner | A splice-aware alignment software designed specifically for RNA-seq data that accurately maps reads to a reference genome, allowing for transcript discovery and quantification [34]. |

| Reference Genome FASTA | The canonical DNA sequence of the organism being studied, against which sequencing reads are aligned to determine their genomic origin. |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | A file that describes the locations and structures of genomic features (genes, exons, etc.), used during alignment and for quantifying gene counts. |

| Biocontainer | A containerized version of a bioinformatics tool (e.g., as a Docker or Singularity image) that ensures a reproducible and conflict-free software environment [34]. |

Robust Quality Control (QC) is the foundation of reliable, reproducible data in systems biology. For metabolomics and proteomics, platform-specific QC strategies are essential to manage the complexity of the data and mitigate technical variability, ensuring that observed differences reflect true biology rather than analytical artifacts. This guide details best-practice QC protocols for both fields, providing researchers and drug development professionals with actionable troubleshooting frameworks to enhance data quality.

Metabolomics Quality Control (QC) Best Practices

The QComics Protocol

QComics is a robust, sequential workflow for monitoring and controlling data quality in metabolomics studies. Its multi-step process addresses common pitfalls, from background noise to preanalytical errors [37].

Core Steps of the QComics Workflow:

- Initial Data Exploration: Detect contaminants, batch drifts, and "out-of-control" observations.

- Handling Missing Data: Differentiate between missing values and truly absent biological signals to prevent loss of information.

- Outlier Removal: Identify and remove outlying samples that can skew results.

- Monitoring Quality Markers: Use specific chemical descriptors to address preanalytical errors from sample collection or storage.

- Final Data Quality Assessment: Evaluate overall data quality in terms of precision and accuracy.

Experimental Protocol for QComics Implementation:

Sample Preparation:

- Procedural Blanks: Prepare by replacing the biological sample with water during extraction, using the same chemicals and SOPs. Analyze five blanks at the start and end of the sequence to assess background noise and carryover [37].

- QC Samples: Prepare a pooled QC sample by mixing equal aliquots of all study samples. If pooling is not viable, use a surrogate bulk representative sample [37].

LC-MS Analysis Sequence:

- Inject five consecutive procedural blanks for system stabilization [37].

- Inject at least five consecutive QC samples to condition the system for the study matrix [37].

- Analyze real samples in a randomized order. Intercalate a QC sample after every 10 study samples (increase frequency for smaller studies) [37].

- Inject five procedural blanks at the end to assess carryover [37].

Chemical Descriptors for Quality Assessment: Select a set of metabolites that are reliably detected in the QC samples. These should represent diverse chemical classes, molecular weights, and chromatographic retention times to monitor method reproducibility comprehensively [37].

Real-Time QC Monitoring with QC4Metabolomics

For real-time monitoring, QC4Metabolomics is a software tool that tracks user-defined compounds during data acquisition. It extracts diagnostic information such as observed m/z, retention time, intensity, and peak shape, presenting results on a web dashboard. This allows for the immediate detection of issues like retention time drift or severe ion suppression, enabling corrective action during the analysis rather than after its completion [38].

Post-Acquisition Correction with PARSEC

For improving the comparability of separately acquired metabolomics datasets, the PARSEC (Post-Acquisition Standardization to Enhance Comparability) strategy offers a three-step workflow. This method involves data extraction, standardization, and filtering to correct for analytical bias without long-term quality controls, enhancing data interoperability across studies [39].

Proteomics Quality Control (QC) Best Practices

Addressing Core Proteomics Challenges

Proteomics faces unique hurdles, including the vast dynamic range of protein abundance and the introduction of batch effects. The following table summarizes common challenges and their mitigation strategies [40].

Table 1: Common Proteomics Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge Area | Technical Issue | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | High dynamic range, ion suppression | Depletion of high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin); multi-step peptide fractionation (e.g., high-pH reverse phase) [40]. |

| Batch Effects | Confounding technical variance | Employ randomized block design; inject pooled QC reference samples frequently (e.g., every 10-15 injections) across all batches [40]. |

| Data Quality | Missing values, undersampling | Utilize Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA); apply sophisticated imputation algorithms based on the nature of the missingness (MAR vs. MNAR) [40]. |

Automated QC in High-Throughput Proteomics

The π-Station represents an advanced, fully automated sample-to-data system designed for unmanned proteomics data generation. Its integrated QC framework, π-ProteomicInfo, is key to maintaining data quality [41].

The π-ProteomicInfo Automated QC Workflow:

- Monitor Module: A standalone program tracks instrument status and automatically transfers raw data files upon run completion [41].

- Analyzer Module: Triggered after data transfer, it generates qualitative and quantitative profiles for each run [41].

- QC Module: Extracts QC metrics for data quality assessments. If QC data is unqualified, it triggers the Controller Module [41].

- Controller Module: Immediately stops data acquisition to prevent the loss of precious samples and sends text notifications to specialists for maintenance [41].

Benchmarking Performance: In a long-term stability assessment over 63 days, the π-Station platform demonstrated a variation in protein identification below 3% (intra-day) and 6% (inter-day), with a maximum median CV of protein abundance under 8%, showcasing exceptional robustness [41].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Metabolomics Troubleshooting

Q: My QC samples do not cluster tightly in a PCA scores plot. What could be the cause? A: Poor clustering of QCs indicates high analytical variability. Potential causes include instrument sensitivity drift, column degradation, inconsistent sample preparation, or issues with the pooling of the QC sample itself. Check the reproducibility of your chemical descriptors' retention times and peak areas. Implementing a real-time monitor like QC4Metabolomics can help identify such issues as they occur [38].

Q: How should I handle missing values in my metabolomics dataset? A: QComics emphasizes the need to separately handle missing values (e.g., due to low abundance) from truly absent biological data. For values missing due to being below the limit of detection, imputation with a small value (e.g., drawn from the lower end of the detectable distribution) may be appropriate. Values missing at random might be addressed with more advanced imputation methods, but the strategy should be carefully chosen to avoid introducing bias [37].

Proteomics Troubleshooting

Q: What are the signs that sample preparation failed in a proteomics run? A: Key indicators include very low peptide yield after digestion, poor chromatographic peak shape, excessive baseline noise in the mass spectrometer (suggesting detergent or salt contamination), or a high coefficient of variation (CV > 20%) in protein quantification across technical replicates [40].

Q: How can I prevent batch effects from confounding my study during the experimental design phase? A: The most effective strategy is a randomized block design. This ensures that samples from all biological comparison groups (e.g., control vs. treated) are evenly and randomly distributed across all processing and analysis batches. This prevents a technical batch from being perfectly correlated with a biological group, which is a primary source of confounding [40].

Q: What is the best way to handle missing values in quantitative proteomics data? A: The best approach is to first determine if data is Missing at Random (MAR) or Missing Not at Random (MNAR). If MNAR (a protein is missing because its abundance is too low to detect), imputation should use small, low-intensity values drawn from the bottom of the quantitative distribution. If MAR, more robust methods like k-nearest neighbor or singular value decomposition are appropriate [40].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for implementing robust QC in metabolomics and proteomics workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for QC

| Item | Function | Application Field |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled QC Sample | A quality control sample made by pooling aliquots of all study samples; used to monitor analytical stability and performance over the sequence run. | Metabolomics [37], Proteomics [40] |