Beyond Linear Relationships: A Practical Guide to Analyzing Nonlinear Gene Expression Correlations

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of nonlinear gene expression data.

Beyond Linear Relationships: A Practical Guide to Analyzing Nonlinear Gene Expression Correlations

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of nonlinear gene expression data. We cover the foundational principles explaining why nonlinearity is pervasive in biological systems, from circadian rhythms to cell cycle regulation. The guide details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including Kernelized Correlation, the Maximal Information Coefficient, and Gaussian Process models, for detecting and quantifying these relationships. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, such as correcting for technical biases and managing noise, and offers a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of different methods. By synthesizing these concepts, we empower scientists to move beyond traditional linear models, unlocking deeper biological insights from their transcriptomic data for applications in biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

Why Linearity Fails: Uncovering the Pervasive Nature of Nonlinearity in Gene Expression

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: Why do I observe different cell cycle arrest outcomes in my HeLa cell cultures when using etoposide?

Answer: The response to etoposide is highly dependent on concentration. In HeLa cells, etoposide concentrations greater than 0.1 μM typically induce a sustained arrest at the G2/M checkpoint. You will observe an accumulation of cells with a DNA content greater than 2C (yellowish green nuclei if using Fucci2). If you see cells bypassing arrest or entering other cycles like endoreplication, it may indicate sub-optimal drug concentration, issues with cell line health, or the presence of resistant cell subpopulations. Always confirm drug activity and use a fresh stock solution [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Inconsistent G2/M arrest.

- Solution 1: Perform a dose-response curve (e.g., 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM) to establish the optimal concentration for your specific experimental conditions.

- Solution 2: Verify the DNA content of arrested cells via FACS analysis with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI staining to confirm the accumulation of non-diploid (>2C) cells [1].

FAQ 2: My Th17 cell differentiation assays show high variability between experiments conducted at different times of the day. What could be the cause?

Answer: Th17 cell differentiation is directly regulated by the circadian clock. The lineage specification of these cells varies diurnally. The core mechanism involves the circadian clock protein REV-ERBα, which regulates the transcription factor NFIL3. NFIL3, in turn, suppresses Th17 development by binding and repressing the Rorγt promoter. Experiments conducted without controlling for the light-cycle may yield inconsistent results due to this intrinsic biological rhythm [3].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: High variability in Th17 cell frequencies.

- Solution 1: Synchronize your animal facility's light-dark cycles and conduct experiments at a consistent, recorded time of day.

- Solution 2: Analyze key regulatory proteins (e.g., NFIL3, RORγt) via Western blot to confirm the circadian influence on your molecular pathway of interest [3].

FAQ 3: How can I better predict gene expression levels from sequence data in my single-cell research?

- Answer: For predicting cell-type-specific gene expression from DNA sequences, leverage modern computational frameworks like UNICORN. This multi-task learning framework uses embeddings from biological sequences and external knowledge from pre-trained foundation models. It has demonstrated superior performance for gene expression prediction at the cellular and cell-type level compared to earlier models like Enformer or seq2cells. Ensure your training data is aggregated into pseudo-bulk format from single-cell data to mitigate noise, as recommended by recent methodologies [4].

Data derived from population and time-lapse imaging analyses of HeLa and NMuMG cells expressing Fucci2 [1] [2].

| Cell Line | Drug Concentration | Primary Outcome | Key Observational Feature (Fucci2) | DNA Content (FACS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | > 0.1 μM | Sustained G2/M arrest | Nuclei exhibit bright yellowish green fluorescence | >2C (non-diploid) |

| NMuMG | 1 μM | Transient G2 arrest → Nuclear mis-segregation | Accumulation of cells with fragmented, red nuclei | Mixed (fragmented) |

| NMuMG | 10 μM | Transition to endoreplication cycle | Large, clear red nuclei | 4C (tetraploid) |

Protocol 1: Monitoring Dynamic Cell Cycle Modulation with Fucci2

Application: Real-time visualization of drug effects on the cell cycle.

Key Reagents:

- Cell Lines: HeLa or NMuMG cells stably expressing Fucci2 (mCherry-hCdt1(30/120) and mVenus-hGem(1/110)) [1] [2].

- Drug: Etoposide, dissolved in DMSO.

- Imaging Equipment: Computer-assisted fluorescence microscopy system (e.g., Olympus LCV100) or a fully automated image acquisition platform (e.g., Olympus CELAVIEW RS100).

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Plate Fucci2-expressing cells on glass-bottom dishes and allow them to adhere.

- Drug Treatment: Treat cells with the desired concentration of etoposide (e.g., 1 μM, 10 μM). Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Place dishes on the microscope system maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Perform time-lapse imaging every 20-30 minutes over an extended period (e.g., 24-48 hours).

- Data Analysis: Track individual cells to monitor fluorescence color changes. A transition from yellowish green to red without cell division indicates endoreplication. Nuclear envelope breakdown followed by fragmentation indicates mis-segregation [1] [2].

Protocol 2: Investigating Circadian Regulation of Th17 Differentiation

Application: Assessing the diurnal variation in T helper cell lineage specification.

Key Reagents:

- Mice: Rev-erbα⁻⁻ mice and wild-type controls [3].

- Cell Isolation: CD4+ T cells from murine spleen or lymph nodes.

- Differentiation Media: Cytokines for in vitro Th17 polarization (e.g., TGF-β, IL-6).

- Analysis Tools: Flow cytometry antibodies for IL-17A and RORγt.

Methodology:

- In Vivo Context: House mice under a strict 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. Sacrifice and isolate cells at specific zeitgeber times (e.g., ZT0 for lights on, ZT12 for lights off) [3].

- Cell Differentiation: Isolate naive CD4+ T cells and activate them under Th17-polarizing conditions in vitro.

- Analysis: After several days, analyze cells via flow cytometry for IL-17A production and RORγt expression. Intracellular staining for NFIL3 can further confirm the circadian mechanism.

- Model Verification: Compare Th17 differentiation efficiency between Rev-erbα⁻⁻ mice and wild-type controls to establish the role of the circadian clock [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cell Cycle and Differentiation Studies

A toolkit of key materials referenced in the featured research.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fucci2 Probe | Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for real-time, live-cell visualization of cell cycle progression (G1: red, S/G2/M: green) [1] [2]. | mCherry-hCdt1(30/120) and mVenus-hGem(1/110). |

| Etoposide | DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor; used to induce DNA damage and study G2/M checkpoint arrest and subsequent cell fate decisions [1] [2]. | Working concentration >0.1 μM; perform dose-response. |

| NFIL3 Antibody | Transcription factor that suppresses Th17 cell development; key for investigating circadian regulation of immune cell differentiation [3]. | Used in Western blot or ChIP to study repression of Rorγt. |

| REV-ERBα Agonist/Antagonist | Pharmacological tools to manipulate the circadian clock pathway, allowing direct testing of its role in Th17 differentiation [3]. | Useful for probing the REV-ERBα → NFIL3 → RORγt axis. |

| UNICORN Framework | Computational framework for predicting cell-type-specific gene expression and multi-omic phenotypes from biological sequences [4]. | Integrates sequence embeddings from foundation models for enhanced prediction. |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Circadian Regulation of Th17 Differentiation

UNICORN Gene Expression Prediction Workflow

Cell Fate Decisions After Etoposide Treatment

Technical Support Center

Context: This support center is framed within a broader thesis on advancing gene expression correlation research beyond linear assumptions. It addresses common analytical pitfalls and provides methodologies for detecting complex, nonlinear relationships.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My gene co-expression network analysis (e.g., WGCNA) seems to miss important functional modules. Could my correlation metric be the problem?

A: Yes, this is a common issue. Traditional WGCNA primarily relies on linear correlation coefficients (like Pearson's r or Spearman's ρ) to construct gene networks [5]. However, biological relationships, such as those in signaling pathways or feedback loops, are often nonlinear. Relying solely on linear metrics can fail to capture these essential relationships, leading to incomplete or misleading modules [6]. For example, a study on Alzheimer's disease found that using Hellinger correlation within WGCNA uncovered novel links between inflammation and mitochondrial function that were missed by linear methods [5].

- Solution: Integrate a "not-only-linear" correlation coefficient into your WGCNA pipeline. Options include:

- Hellinger Correlation: Effective for capturing nonlinear dependence in gene expression data [5].

- Clustermatch Correlation Coefficient (CCC): A computationally efficient, clustering-based coefficient designed for genome-scale data that detects both linear and nonlinear patterns [7].

- Maximum Local Correlation (M): A nonparametric method that quantifies nonlinear association by reporting local correlation patterns, suitable for noisy biological data [6].

Q2: I am building a predictive model from transcriptomic data (e.g., for disease diagnosis), but my model validation using correlation metrics seems overly optimistic. How can I get a more reliable assessment?

A: This is a critical limitation highlighted in connectome-based predictive modeling, which is analogous to gene-expression-based predictive modeling. The Pearson correlation coefficient between predicted and observed values is widely used but has key flaws: it inadequately reflects model errors (especially systematic bias), lacks comparability across studies, and is highly sensitive to outliers [8]. A high correlation can mask significant prediction inaccuracies.

- Solution: Adopt a multi-metric validation framework. Do not rely on correlation alone.

- Incorporate Difference Metrics: Always report Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). These metrics directly quantify prediction error magnitude and are more informative about model accuracy [8].

- Implement Baseline Comparisons: Compare your complex model's performance (e.g., a LASSO or SVM model) against a simple baseline, such as predicting the mean value of the target or using a simple linear regression. This evaluates the added value of your model [8].

- Perform External Validation: Validate your model on a completely independent dataset to test its generalizability [8].

Q3: How can I systematically identify genes involved in nonlinear relationships for further experimental validation?

A: Feature selection based solely on linear correlation with a phenotype may overlook key nonlinear drivers.

- Solution: Employ a multi-stage analytical protocol that integrates nonlinear detection.

- Differential Expression & Network Analysis: Start with standard differential expression analysis (using

limmawith criteria like \|log2FC\|>1.5 and adj. p < 0.05) to find candidate genes [9] [10]. In parallel, perform WGCNA using a nonlinear correlation metric (see Q1) to identify co-expression modules associated with your phenotype [9] [5]. - Intersection and Prioritization: Intersect genes from the differential expression list with those in significant WGCNA modules to narrow down candidates [9].

- Nonlinear Relationship Screening: Apply a nonlinear correlation measure (like CCC [7] or Maximum Local Correlation [6]) between the shortlisted genes and the phenotype of interest across all samples. Rank genes by the strength of this nonlinear association.

- Predictive Modeling for Final Selection: Use machine learning models like LASSO regression or Support Vector Machine (SVM) with cross-validation on the prioritized gene set to finalize a robust, parsimonious signature [9] [10] [11].

- Differential Expression & Network Analysis: Start with standard differential expression analysis (using

Supporting Data & Protocols

Table 1: Usage of Model Evaluation Metrics in Predictive Modeling Studies (2022-2024) Data adapted from a review of connectome-based predictive modeling studies, relevant to biomarker prediction studies [8].

| Evaluation Metric Category | Frequency (%) | Purpose & Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman/Kendall Correlation | 30.09% | Captures monotonic but not general nonlinear relationships. |

| Difference Metrics (MAE, RMSE) | 38.94% | Crucial. Directly quantifies prediction error. |

| External Validation | 30.09% | Best practice. Tests model generalizability on independent data. |

Table 2: Key Nonlinear Correlation Coefficients for Gene Expression Analysis

| Coefficient | Key Principle | Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clustermatch (CCC) | Uses clustering of binned data to detect associations. | Computationally efficient for genome-scale data; detects linear and nonlinear patterns. | [7] |

| Maximum Local Correlation (M) | Nonparametric; based on local neighbor density vs. a null distribution. | Distribution-free; detects transient/local correlations; robust to noise. | [6] |

| Hellinger Correlation | Derived from Hellinger distance between probability distributions. | Sensitive to various dependency structures; useful in WGCNA. | [5] |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing Maximum Local Correlation Analysis

Objective: To detect and quantify nonlinear correlations between gene expression profiles or between a gene and a clinical phenotype.

- Data Preprocessing: Transform the expression data for each variable (gene) to a uniform marginal distribution. This is typically done by rank transformation followed by normalization to the [0,1] interval [6].

- Calculate Neighbor Density: For the pair of variables (x, y), compute the Euclidean distances between all sample points. Generate the correlation integral Î(r), which is the cumulative distribution of these distances. The neighbor density D̂(r) is the derivative (estimated discrete change) of Î(r) [6].

- Generate Null Distribution: Create a permuted null distribution (D̂₀(r)) by randomly shuffling one variable relative to the other many times (e.g., B=1000 permutations) and recalculating D̂(r) for each permutation [6].

- Compute Local Correlation: The local correlation ℓ(r) at a distance scale r is defined as ℓ(r) = D̂(r) - D̂₀(r). Statistical significance at each r can be assessed via permutation p-values [6].

- Compute Maximal Correlation: The overall nonlinear association is summarized by the Maximum Local Correlation M, defined as M = maxᵣ \|ℓ(r)\|. The significance of M is assessed by comparing the observed M to the distribution of M values from the permutations [6].

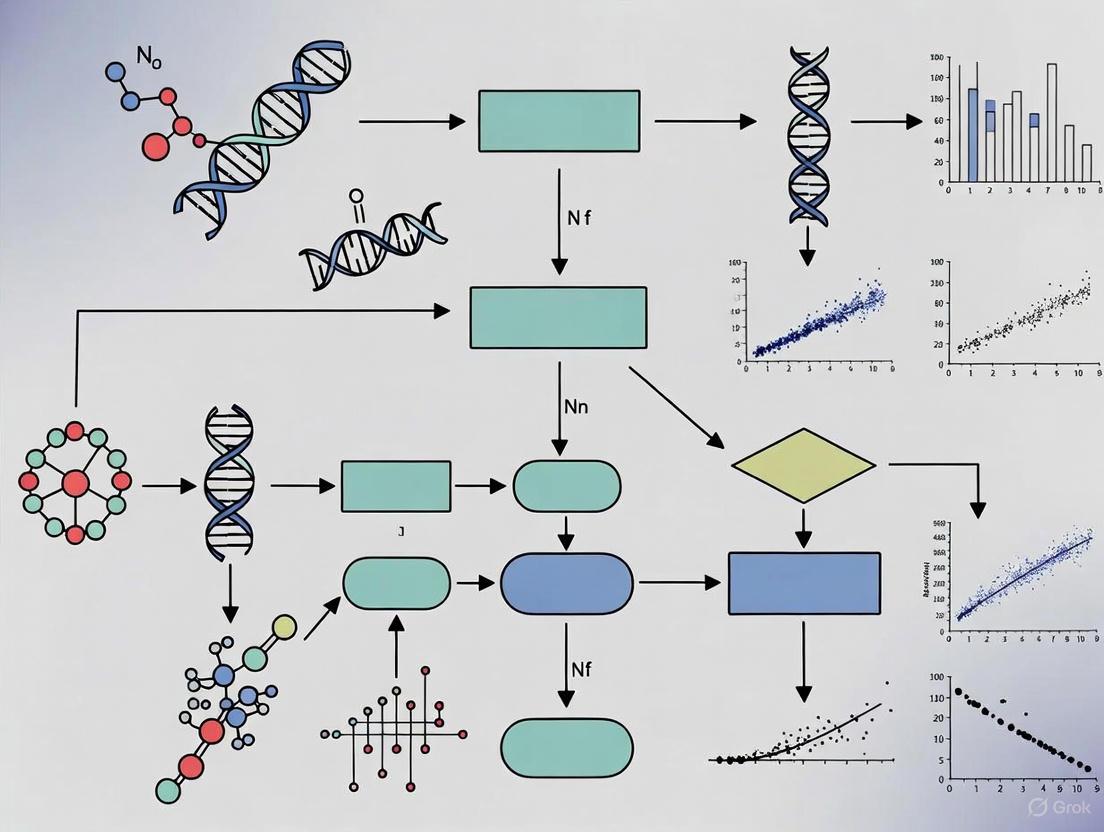

Visualizing Analytical Workflows

Diagram 1: Linear vs Nonlinear-Aware Gene Analysis Workflow (89 chars)

Diagram 2: Nonlinear Gene Signature Discovery Protocol (88 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents & Materials for Gene Expression Correlation Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Public Repository Access (GEO) | Source of high-throughput gene expression datasets (microarray, RNA-seq) for analysis and validation. | Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) is a primary public archive [9] [12] [10]. |

| Batch Effect Removal Tool | Corrects for non-biological technical variation when integrating multiple datasets, crucial for robust analysis. | R package sva (Surrogate Variable Analysis) is commonly used [9] [10]. |

| Differential Expression Analysis Software | Statistically identifies genes with significant expression changes between conditions. | R package limma is a standard for microarray/RNA-seq data [9] [10]. |

| WGCNA Package | Constructs gene co-expression networks to identify modules of highly correlated genes. | R package WGCNA is the standard implementation [9] [5]. |

| Nonlinear Correlation Software/Library | Enables calculation of advanced correlation metrics beyond Pearson/Spearman. | NNC library (Matlab) [6], or custom R/Python scripts for CCC [7] or Hellinger corr. [5]. |

| Machine Learning Package (glmnet, e1071) | For building and validating predictive models with feature selection. | R glmnet for LASSO [9] [11]; e1071 for SVM [8]. |

| High-Quality RNA & cDNA Synthesis Kits | Foundational wet-lab step. Poor RNA quality or inefficient cDNA synthesis leads to low yield and noisy data, confounding correlation analysis. | Use of optimized purification and reverse transcription kits is critical [13]. |

| Validated qPCR Assays & Automation | For experimental validation of identified gene signatures. Automated liquid handlers improve precision and reduce Ct value variation [13]. | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays; automated dispensers like I.DOT [14] [13]. |

| Multiple Internal Control Genes | Essential for reliable normalization in qPCR validation, correcting for sample-to-sample variation. | Selected based on stability across samples; geometric mean of multiple controls is recommended [14]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the visual hallmarks of oscillatory and complementary gene expression patterns in my data?

Oscillatory and complementary patterns are key nonlinear relationships in time-course gene expression data. You can identify them through the following characteristics:

| Pattern Type | Visual Hallmark | Description | Common Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillatory | Looping structures in PCA/UMAP space [15] | Cells organize into a circular pattern when projected into dimensionality reduction spaces like PCA, corresponding to a cyclic program of gene expression [15]. | Larval development cycles, circadian rhythms, cell cycle regulation [15]. |

| Complementary | Mirror-image or out-of-phase expression [16] | As the expression of one gene increases, the expression of its partner decreases in a nonlinear, often inverse, relationship [16]. | Yeast cell cycle regulation (e.g., RAD51-HST3 pair) [16]. |

FAQ 2: My data shows clear nonlinear patterns, but standard Pearson correlation fails to detect them. What analytical tools should I use?

Pearson's correlation (r) only measures linear relationships. For nonlinear data, you should use metrics designed for this purpose [16].

| Method | Description | Best For | Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernelized Correlation (Kc) | Transforms data via a kernel to a high-dimensional space before calculating correlation [16]. | Detecting complex, nonlinear correlations (both positive and negative) in time-course data [16]. | Outperforms Pearson's r and distance correlation (dCor) in detecting known nonlinear gene pairs, especially with moderate noise [16]. |

| Distance Correlation (dCor) | Measures dependence based on distance covariance [16]. | Detecting nonlinear associations. | Cannot return negative values, limiting its ability to characterize complementary patterns [16]. |

| Advanced Perceptual Contrast Algorithm (APCA) | An alternative method for calculating contrast that better aligns with human perception [17]. | Evaluating visual contrast in data visualization. | Likely to be part of the future WCAG3 guidelines [17]. |

FAQ 3: How can I effectively visualize these patterns to make them clear and accessible for publication?

Effective visualization ensures your findings are understood by all readers, including those with color vision deficiencies.

| Strategy | Implementation | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Use High-Contrast Colors | Ensure a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text against the background [17]. | Crucial for legibility, aiding users with low vision or in suboptimal lighting conditions [17]. |

| Incorporate Shapes & Patterns | Use distinct node shapes (e.g., circle, triangle, square) or fill patterns (e.g., dots, stripes, crosshatch) to encode categories [18]. | Allows differentiation between data series without relying on color alone, essential for colorblind accessibility [18]. |

| Leverage Lightness | Build color gradients using significant variations in lightness, not just hue. The gradient should be interpretable in grayscale [19]. | Makes gradients decipherable for colorblind users and creates a more intuitive representation of value magnitude [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Failure to Detect Biologically Relevant Oscillatory Gene Expression

- Symptoms:

- Known oscillatory genes do not form a looping structure in your PCA/UMAP projection.

- RNA velocity analysis does not show a coherent directional flow indicative of a cycle.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Sampling Resolution | Increase the density of time points across the biological cycle. | 1. Design: Plan experiments to capture at least 8-12 time points per anticipated cycle (e.g., per larval stage or circadian period).2. Sampling: Collect samples at regular, closely-spaced intervals.3. ScRNA-Seq: Follow a protocol similar to [15]: * Use fluorescent reporters (e.g., grl-18pro::GFP) to enrich for specific cell types via FACS. * Sequence a sufficient number of cells (e.g., 24,000+ cells over multiple replicates) to ensure coverage.4. Computational Analysis: Calculate a weighted circular average of peak phases for each cell using known oscillatory genes as a reference to assign a phase angle [15]. |

| High Noise Obscuring Signal | Apply a nonlinear correlation measure like Kernelized Correlation (Kc) which is more robust to moderate noise. | 1. Data Processing: Normalize your time-course gene expression data (e.g., RNA-seq read counts).2. Kc Calculation: Use the published R code for Kernelized Correlation. * Transform the paired gene expression data using a kernel (e.g., Radial Basis Function). * Compute the Pearson's correlation of the transformed data in the high-dimensional space [16].3. Validation: Compare Kc results against positive and negative control gene pairs with known relationships. |

Problem: Inability to Statistically Validate Complementary Gene Pairs

- Symptoms:

- Two genes visually appear to have a mirror-image expression pattern, but standard correlation tests are non-significant.

- PARE score indicates a negative relationship, but Pearson's r is not significant [16].

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Purely Nonlinear Relationship | Replace Pearson's r with a method designed for nonlinear correlation. | 1. Data Extraction: Compile time-course expression profiles for the gene pair of interest.2. Analysis with Kc: * Input the data into the Kc algorithm with an appropriate kernel. * A significant negative Kc value confirms a complementary relationship. The value ranges between -105 and 105 [16].3. Benchmarking: Validate your findings by checking if the pair is known to be involved in a related biological process (e.g., cell cycle). |

| Inadequate Model for Phase Shift | Model the expression curves directly to account for potential time lags. | 1. Curve Fitting: Fit the expression of each gene to a sinusoidal wave or a Gaussian process to model their dynamics across time [20].2. Phase Calculation: Derive the phase angle at which each gene peaks.3. Phase Difference: Calculate the difference in phase angles. A difference approaching 180° (π radians) is characteristic of a complementary pair. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and computational tools for investigating nonlinear gene expression patterns.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

Fluorescent Reporter Strains (e.g., grl-18pro::GFP for glia) |

Enables enrichment of specific, often rare, cell types via Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) for scRNA-seq, crucial for identifying cell-type-specific oscillations [15]. |

| Kernelized Correlation (Kc) R Code | The primary computational tool for quantifying pairwise nonlinear (oscillatory and complementary) correlations in time-course gene expression data [16]. |

| Distinct Node Shapes & Patterns | A library of visual markers (circles, triangles, squares, stripes, dots) used in charts and graphs to ensure data is distinguishable for all users, including those with color vision deficiencies [18]. |

| Accessible Color Palettes (e.g., Okabe-Ito, Viridis) | Pre-defined color sets that are perceptually uniform and decipherable by individuals with various forms of color blindness, ensuring the clarity and accessibility of data visualizations [21]. |

| RNA Velocity Algorithms | A computational method that uses the ratio of unspliced to spliced mRNA to infer the future state of individual cells, providing independent validation of a cyclic transcriptional program [15]. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

ScRNA-seq Workflow for Oscillatory Analysis

Nonlinear Correlation Detection Pathway

Complementary Gene Relationship

A Toolkit for Discovery: Key Methods to Detect and Measure Nonlinear Correlations

Kernelized Correlation (Kc) is an advanced computational procedure designed to measure nonlinear relationships between variables, with significant applications in gene expression analysis. Traditional correlation coefficients like Pearson's r can only identify linear relationships, leaving potentially important nonlinear associations undetected in biological data. Kc addresses this limitation by first transforming nonlinear data via a kernel function (usually nonlinear) to a high-dimensional space, then applying a classical correlation coefficient to the transformed data. This approach effectively captures complex nonlinear patterns prevalent in time-course gene expression studies and other biomedical data types [16].

In the context of gene expression research, Kc has demonstrated particular value for identifying genes involved in specific biological processes. For instance, when applied to early human T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, Kc successfully detected nonlinear correlations of four genes with IL17A (a known marker gene), while distance correlation detected only two pairs, and DESeq failed in all these pairs. Similarly, Kc outperformed both Pearson's correlation and distance correlation in estimating nonlinear correlations of negatively correlated gene pairs in yeast cell cycle regulation [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What types of biological relationships can Kc detect that linear correlations cannot? Kc can identify various nonlinear relationships including periodic expressions, complementary patterns (where one gene's expression increases as another decreases in complex patterns), and other non-linear dependencies. These are common in gene regulatory networks where linear methods often fail to detect significant biological interactions [16].

How does Kc handle negative correlations? Unlike some nonlinear correlation measures like distance correlation (dCor) that range only between 0 and 1, Kc can quantify both positive and negative correlations through negative values. This is particularly important for detecting complementary expression patterns like those between RAD51 and HST3 in yeast cell cycle regulation [16].

What are the computational requirements for implementing Kc? Kc implementation requires consideration of kernel selection, regularization parameters, and efficient computation strategies. The R code for computing Kc is publicly available online and can handle the calculation of [n(n-1)]/2 pairwise correlations in a dataset containing n variables (e.g., 20,000 genes in a microarray) [16].

Which kernel functions are most effective for gene expression data? The Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel has shown strong performance with gene expression data, particularly when noise levels are moderate. In simulated cases with moderate noise, Kc with RBF kernel outperformed both Pearson's r and distance correlation [16].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent correlation values across different runs Solution: This inconsistency may stem from improper kernel parameter selection. For the RBF kernel, ensure the bandwidth parameter (σ) is optimized for your specific data characteristics. Conduct sensitivity analyses across a range of parameter values to establish stable results [16] [22].

Problem: High computational demands with large gene sets Solution: Utilize the circulant matrix properties and Fourier domain operations inherent in Kc methodology. These computational shortcuts allow efficient processing of large datasets by transforming operations to the frequency domain where they can be computed more rapidly [22].

Problem: Difficulty interpreting biological significance of results Solution: Implement rigorous false discovery rate controls specifically designed for kernel methods. For comprehensive gene-gene interaction testing, apply Efron's empirical null method to estimate local false discovery rates, which accounts for multiple testing and test statistic correlation [23].

Problem: Poor performance with low-noise data Solution: When data noise is minimal, traditional linear methods may occasionally outperform Kc. In such cases, consider running both linear and nonlinear correlation analyses simultaneously, as Kc performs equivalently to Pearson's r and dCor in low-noise conditions while significantly outperforming them in moderate-noise scenarios [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Nonlinear Gene Correlations in Time-Course Data

Purpose: To detect and quantify nonlinear correlations between gene pairs across time-course expression data [16].

Materials:

- Normalized gene expression data (RNA-seq or microarray)

- Computational environment with Kc implementation

- R statistical software with necessary packages

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Format expression data as matrices with genes as variables and time points as observations.

- Kernel Selection: Choose an appropriate kernel (typically RBF Gaussian kernel) and set parameters.

- Transformation: Map original gene expression data to high-dimensional feature space using the kernel function.

- Correlation Calculation: Compute correlation coefficients in the transformed space using standard correlation measures.

- Significance Testing: Apply statistical tests to identify significant correlations.

- Biological Validation: Compare results with known pathway information or conduct experimental validation.

Expected Results: Identification of significantly correlated gene pairs exhibiting nonlinear relationships across time, potentially revealing novel regulatory relationships.

Protocol 2: Identifying Genes Associated with Cell Differentiation

Purpose: To discover novel genes involved in specific cell differentiation processes through nonlinear correlation with known marker genes [16].

Materials:

- Time-course RNA-seq data during differentiation process

- Known marker genes (e.g., IL17A for Th17 cell differentiation)

- Kc algorithm implementation

Procedure:

- Target Selection: Identify established marker genes for the differentiation process of interest.

- Correlation Screening: Compute Kc values between the marker gene and all other genes across the time series.

- Ranking: Sort genes by absolute Kc values to identify top candidates.

- Threshold Application: Establish significance thresholds based on false discovery rates.

- Pathway Analysis: Conduct enrichment analysis on identified genes to validate biological relevance.

Expected Results: Discovery of potential novel genes involved in the differentiation process based on their nonlinear correlation patterns with established markers.

Comparative Analysis of Correlation Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of correlation methods on different data types

| Method | Nonlinear Detection | Negative Values | Noise Robustness | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson's r | No | Yes | Low | Linear relationships |

| Spearman's rank | Limited | Yes | Medium | Monotonic relationships |

| Distance correlation | Yes | No | Medium | General dependence |

| Kendall's tau | Limited | Yes | Low | Rank-based analysis |

| Kernelized Correlation | Yes | Yes | High | Complex nonlinear patterns |

Table 2: Kc performance in specific biological applications

| Application | Kc Detections | Comparison Method Results | Biological Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Th17 cell differentiation | 4 genes with IL17A | dCor: 2 genes; DESeq: 0 genes | Verified known biology |

| Yeast cell cycle | RAD51-HST3 correlation | Pearson's r: -0.50 (p=0.203) | Supported by PARE score |

| Simulated data (moderate noise) | Outperformed alternatives | Better than Pearson's r and dCor | Controlled conditions |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and computational tools for Kc experiments

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RBF Gaussian kernel | Nonlinearly transforms data to high-dimensional space | Default kernel for most Kc applications |

| Regularization parameter (λ) | Prevents overfitting in ridge regression | Typically set to 1e-4 in KCF implementations |

| Circulant matrix | Enables efficient dense sampling | Foundation for fast Fourier domain computations |

| Fourier transform | Accelerates computational operations | Critical for real-time performance |

| Cosine window function | Mitigates boundary artifacts | Applied to input patches in tracking applications |

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Kc Analysis Workflow: From raw data to nonlinear correlation measurement

Gene Discovery via Kc: Identifying Th17-associated genes through nonlinear correlation with IL17A

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of using MIC over traditional linear methods like Pearson correlation in gene expression analysis? MIC's primary advantage is its generality; it can capture a wide range of linear and non-linear associations (e.g., cubic, exponential, sinusoidal) without assuming a specific functional form or data distribution. This is crucial for gene expression data, where underlying relationships are often complex and non-linear. In contrast, Pearson correlation can only detect linear dependencies [24].

Q2: My analysis with MIC still prioritizes linearly expressed genes. How can I specifically highlight genes with non-linear expression patterns? This is a known limitation of MIC, as the genes with the strongest support are often linearly expressed [25]. To overcome this, use the Normalized Differential Correlation (NDC) measure. NDC is specifically designed to elevate the ranking of non-linearly expressed genes by normalizing the difference between the nonlinear score (MIC) and the linear score (R²) [25] [26].

Q3: Why is my MIC computation so slow, and how can I speed it up? The standard MIC algorithm is computationally expensive because it searches for optimal binning across many possible grids for each variable pair [27] [28]. To improve speed:

- Use optimized implementations like RapidMic, which uses parallel computing [28].

- Employ the ChiMIC algorithm, an improved method that provides a more efficient calculation of MIC [25] [26].

Q4: What does a high NDC score signify in a practical sense? A high NDC score indicates a strong nonlinear association between a gene's expression and the phenotype, coupled with a weak linear correlation [25] [26]. This means the gene's expression pattern (e.g., high and low levels in both control and disease groups) is uniquely useful for classification, a pattern that linear methods would typically overlook.

Q5: Are there methods to go beyond pairwise analysis and understand multi-gene interactions? Yes, Partial Information Decomposition (PID) is a refined information-theoretic approach that decomposes the information multiple source genes provide about a target into unique, redundant, and synergistic contributions. This helps uncover higher-order behaviors where information about a phenotype is only available through the combination of specific genes [29] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inability to Detect Biologically Relevant Non-Linear Genes

- Symptoms: Your analysis fails to identify genes with clear, non-linear patterns (e.g., a U-shaped or inverted U-shaped relationship with the phenotype) that are biologically plausible.

- Causes: Over-reliance on linear methods (t-test, edgeR, DESeq2) or using MIC alone, which may rank linearly expressed genes higher.

- Solutions:

- Implement the NDC Method: Integrate the NDC measure into your pipeline to re-rank genes. A higher NDC score specifically flags genes with strong nonlinear associations [25].

- Visual Inspection: For top-ranked genes by NDC, create scatter plots of gene expression versus the phenotype to visually confirm the non-linear relationship.

Problem 2: Long Computation Times for MIC on Large Datasets

- Symptoms: The calculation of MIC for all gene-pairs takes an impractically long time or runs out of memory.

- Causes: The heuristic search over many possible grids is inherently computationally intensive [28].

- Solutions:

- Use Parallel Computing Tools: Employ software like RapidMic, which is designed for the rapid, parallel computation of MIC, significantly reducing processing time [28].

- Leverage Optimized Algorithms: Use the ChiMIC algorithm, which provides a more robust calculation and may be more efficient than the original ApproxMaxMI algorithm [25] [26].

Problem 3: Low Statistical Power or Unreliable MIC Estimates

- Symptoms: MIC detects spurious correlations in random data or fails to detect known relationships, especially with small sample sizes.

- Causes: Finite-sample effects can inflate MIC scores, and the statistic may have reduced power in some settings compared to other methods [27] [25].

- Solutions:

- Calculate a Significance Threshold: Establish a confidence limit (e.g., ThreMIC) by shuffering your phenotype labels and recalculating MIC many times (e.g., 1,000). Use the 95th percentile of these shuffled scores as a threshold to filter out potentially insignificant associations [25] [26].

- Consider Sample Size: Be aware of the method's limitations in low-sample-size settings and interpret results with caution.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Identifying Non-linearly Expressed Genes with NDC

This protocol outlines how to apply the NDC measure to RNA-seq data to find genes with non-linear correlations to a binary phenotype (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) [25] [26].

- Data Preparation: Format your gene expression matrix (genes as rows, samples as columns) and a corresponding phenotype label vector.

- Calculate MIC: For each gene, compute the MIC value between its expression and the phenotype labels. The use of the ChiMIC algorithm is recommended [25].

- Calculate Linear Statistics: For each gene, compute the coefficient of determination (R²) and the absolute value of the correlation coefficient |R| with the phenotype.

- Establish ThreMIC:

- Randomly shuffle the phenotype labels.

- Calculate the MIC between the shuffled labels and each gene's expression.

- Repeat this process 1,000 times.

- For each gene, the ThreMIC value is the 95th percentile of its 1,000 shuffled MIC values.

- Compute NDC Score: Apply the formula for each gene:

NDC = [MIC(x,y) - ThreMIC] - R²(x,y) / |R(x,y)|[26] - Rank and Select Genes: Rank all genes in descending order of their NDC score. The top-ranked genes have a strong nonlinear association but a weak linear correlation.

The following workflow diagram summarizes this protocol:

Quantitative Data Comparison

The table below summarizes a comparison of different methods on real-world cancer RNA-seq datasets (e.g., LUSC), demonstrating NDC's unique value [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Gene Selection Methods on a Cancer Dataset (e.g., LUSC)

| Method | Primary Association Type Detected | Overlap with Top 100 Genes from t-test | Ability to Rank Non-linear Genes Highly |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-test | Linear | Full (Benchmark) | No |

| edgeR | Linear | Very High | No |

| DESeq2 | Linear | Very High | No |

| MIC | Linear & Non-linear | High | Limited |

| NDC | Non-linear | No Overlap | Yes |

Table 2: Example Rankings of a Top NDC Gene (PSAT1 in BRCA)

| Gene | NDC Rank | t-test Rank | DESeq2 Rank | edgeR Rank | MIC Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSAT1 | 1 | 8,583 | 4,642 | 4,292 | 947 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|

| ChiMIC Algorithm | An improved algorithm for calculating MIC, designed to be more robust than the original ApproxMaxMI method. | [25] [26] |

| RapidMic Tool | A cross-platform tool for rapid computation of MIC using parallel computing, essential for large-scale datasets. | [28] |

| Gaussian Copula Mutual Information (GCMI) | A method for reliable estimation of mutual information, addressing challenges with histogram-based estimators. | [29] |

| Partial Information Decomposition (PID) | A framework for decomposing information shared by multiple source genes about a target into unique, redundant, and synergistic components. | [29] [30] |

| TCGA RNA-seq Datasets | Publicly available cancer gene expression datasets (e.g., from UCSC Xena platform) used for method validation. | [25] |

Conceptual Diagram of NDC Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of how the NDC score is derived from other statistical measures to isolate non-linearity.

This technical support center is framed within a broader thesis investigating the handling of nonlinear correlations in gene expression research. Gaussian Processes (GPs) provide a powerful, non-parametric Bayesian framework for modeling these complex, dynamic interactions, particularly in single-cell genomics and genetic association studies [31] [32]. This resource is designed to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in implementing and troubleshooting GP-based models in their experimental workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of using Gaussian Processes over traditional linear models for gene expression analysis?

- Answer: Traditional linear models assume conditional independence between observations and fixed, linear effect sizes, which often fails to capture the nonlinear dynamics inherent in biological systems like cellular state transitions or dose-response relationships [32]. GPs overcome this by defining a probability distribution over possible nonlinear functions. They inherently provide uncertainty estimates for predictions, which is crucial for interpreting noisy biological data, and can model complex covariance structures through kernel functions [33]. For instance, in perturbation screens, GPs can separate basal expression from sparse perturbation effects while quantifying uncertainty [31].

FAQ 2: My single-cell perturbation data is extremely sparse and high-dimensional. Can GP models handle this?

- Answer: Yes, this is a key application. Methods like GPerturb are specifically designed for the high dimensionality and sparsity of single-cell CRISPR screening data (e.g., Perturb-seq) [31]. They employ sparse, additive structures where a perturbation effect is only "switched on" for genes it meaningfully affects, which regularizes the model and improves interpretability. To handle computational complexity with large cell numbers, sparse GP approximations using inducing points can be implemented, reducing cost from ({{{{{{{\mathcal{O}}}}}}}}({N}^{3})) to ({{{{{{{\mathcal{O}}}}}}}}(N{M}^{2})) where M ≪ N [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Prediction Performance or Model Instability.

- Symptom: Low correlation between predicted and observed gene expression values post-perturbation, or inconsistent directionality of effects (e.g., predicted up-regulation vs. observed down-regulation).

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Inappropriate Data Preprocessing: GP model performance is sensitive to input data type. Confirm you are using the correct variant of the model for your data format.

- Solution: For raw UMI count data, use a model with a Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) likelihood (e.g., GPerturb-ZIP). For log-normalized or otherwise continuous data, use a Gaussian likelihood model (e.g., GPerturb-Gaussian) [31].

- Kernel Mis-specification: The kernel function defines the smoothness and structure of the functions the GP can learn.

- Solution: For modeling continuous cellular states (e.g., pseudotime, dose), use the Automatic Relevance Determination Squared Exponential (ARD-SE) kernel, which can learn relevant length scales for different input dimensions [32]. Experiment with different kernels (e.g., Matérn, linear combination) based on your assumptions about the data.

- Unaccounted for Confounding Variation: In genetic association mapping, correlations between samples (e.g., from the same donor) can inflate false positive rates if not modeled [32].

- Solution: Include a correction term in your GP model that accounts for between-donor variation using a kinship matrix or donor design matrix, as shown in Eq. (1) of the genetic association model [32].

- Inappropriate Data Preprocessing: GP model performance is sensitive to input data type. Confirm you are using the correct variant of the model for your data format.

FAQ 3: How can I model dynamic genetic effects, such as eQTLs that change across a continuous cellular state?

- Answer: A GP regression framework is ideal for this. You can extend the linear model (y = α + βg + ε) by modeling the genetic effect (β) itself as a function of a continuous covariate (x) (e.g., time, drug concentration) using a GP: (β \sim {{{{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}}}}(0, δg K)), where (K) is the kernel matrix over (x) [32]. This allows the effect size to vary nonlinearly along (x). Hypothesis testing involves assessing whether (δg > 0).

FAQ 4: Can GPs be used for inferring gene regulatory networks (GRNs) beyond simple correlation?

- Answer: Absolutely. Assuming a multivariate normal distribution for gene expression limits GRN inference to linear correlations. GPs relax this constraint by using kernels to model complex, nonlinear relationships between genes. A GP emulator can be used to learn the joint distribution of gene expressions, after which a precision matrix (inverse covariance) estimated via methods like graphical LASSO can reveal the conditional dependencies that define the network structure [34].

Experimental Protocols

Application: Analyzing single-cell CRISPR screening data (e.g., Perturb-seq) to quantify the effect of genetic perturbations on gene expression. Detailed Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Format your data into a cells (N) x genes (G) expression matrix. Prepare two annotation vectors: (i) a perturbation label for each cell, (ii) cell-specific covariates (e.g., cell type, batch, sequencing depth).

- Model Specification: For each gene (g), specify a generative model. For continuous data (GPerturb-Gaussian): (y{i,g} \sim \mathcal{N}(μ{i,g}, σ^2)) (μ{i,g} = f{basal,g}(ci) + z{g,p} * f{pert,g}(pi)) where for cell (i), (ci) are cell covariates, (pi) is the perturbation label, (f{basal,g}) and (f{pert,g}) are independent Gaussian Processes, and (z_{g,p}) is a binary spike-and-slab variable determining if perturbation (p) affects gene (g).

- Model Inference: Use variational inference or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to approximate the posterior distributions of all model parameters, including the GP functions and the binary switches (z_{g,p}).

- Output Interpretation: The mean of (f{pert,g}(p)) estimates the perturbation effect size. The posterior probability of (z{g,p}=1) indicates the confidence that a perturbation effect exists. Sparse effects are induced through the prior on (z).

Application: Identifying expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) whose effect size varies along a continuous gradient (e.g., time, cellular state). Detailed Methodology:

- Model Definition: Implement the following hierarchical GP model:

(y = α + β \odot g + γ + ε)

where:

- (α \sim {{{{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}}}}(0, K)), models the baseline expression trend over continuous covariate (X).

- (β \sim {{{{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}}}}(0, δg K)), models the dynamic genetic effect over (X). (K = k(X, X)) is the kernel matrix (e.g., ARD-SE).

- (γ \sim {{{{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}}}}(0, δd K \odot R)), accounts for correlated sample structure using kinship matrix (R).

- (ε \sim {{{{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}}}}(0, σ^2 I)).

- Kinship Matrix Calculation: If using unrelated donors, approximate (R = ZZ^⊤), where (Z) is a donor design matrix. For related samples, estimate (R) from genome-wide genotype data.

- Statistical Testing: Test the null hypothesis (δ_g = 0) (no dynamic genetic effect) using likelihood-ratio or score tests.

- Sparse GP Implementation (for large N): Use an inducing point approximation to reduce computational cost. Represent the GP using (M) inducing points (u), with (p(f|u)) being Gaussian, and optimize a variational lower bound (Titsias bound) [32].

| Method | Input Data Type | Pearson Correlation (r) vs. Observed Expression | Key Assumption/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPerturb-ZIP | Raw Counts | 0.972 | Uses Zero-Inflated Poisson likelihood. |

| SAMS-VAE | Raw Counts | 0.944 | Cannot incorporate cell-level covariates (e.g., cell type). |

| GPerturb-Gaussian | Continuous | 0.981 | Uses Gaussian likelihood. |

| CPA-mlp | Continuous | 0.984 | Requires categorical cell information. |

| GEARS | Continuous | 0.977 | Only handles discrete perturbations; uses external gene graph. |

Analysis of whether different models agree on the sign (up/down-regulation) of gene-perturbation effects.

| Comparison Pair | Input Data Type | Directionality Agreement Note |

|---|---|---|

| GPerturb-Gaussian vs. CPA vs. GEARS | Continuous | Notable discrepancies observed, especially for exosome-related perturbation effects. |

| GPerturb-ZIP vs. SAMS-VAE | Raw Counts | Showed greater consistency, suggesting data pre-processing choice significantly impacts inferred effects. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: GPerturb Model Workflow for Single-Cell Perturbation Analysis

Diagram 2: Hierarchical GP Model for Dynamic Genetic Association Mapping

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in GP Modeling of Gene Expression | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Data | The primary experimental input. Provides high-resolution, perturbed gene expression profiles. | Data from technologies like Perturb-seq or CROP-seq [31]. |

| Cell Covariate Annotations | Used to model basal expression (f_basal). Critical for controlling for biological and technical variation. | Cell type labels, batch information, sequencing depth, cell cycle score. |

| Kernel Function | The core mathematical object defining covariance and smoothness in the GP prior. Choice dictates model flexibility. | ARD-SE Kernel for continuous states [32], Linear kernel for additive effects. |

| (Sparse) Variational Inference Engine | Computational tool for approximate Bayesian inference. Essential for scaling to large datasets. | Implementations using inducing points to handle >10,000 cells [32]. |

| Precision Matrix Estimation Tool | For GRN inference post-GP emulation. Identifies conditional dependencies between genes. | Graphical LASSO (GLASSO) applied to the GP-learned covariance structure [34]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Metrics | Outputs of the Bayesian model that inform confidence in predictions. Key for biological interpretation. | Posterior standard deviation of f_pert, probability of binary effect switch (z) [31]. |

Within the field of genomics, particularly in the analysis of gene expression data, researchers are often confronted with the challenge of visualizing high-dimensional data to uncover biological insights. Traditional linear methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) have been widely used, but their limitations in capturing complex, nonlinear relationships have become increasingly apparent. This technical guide explores the advantages of Isomap, a nonlinear dimensionality reduction technique, over PCA for visualizing data where the underlying structure forms a nonlinear manifold, such as in gene expression correlations.

FAQs: Isomap vs. PCA for Nonlinear Data

1. Why should I consider Isomap over PCA for my gene expression data?

PCA is a linear technique that identifies axes of maximum variance in the data but often fails to capture complex, nonlinear relationships. Gene expression data frequently represents nonlinear interactions between genes and environmental factors [35]. Isomap addresses this by preserving the geodesic distances (the shortest path along the manifold's surface) between data points, rather than straight-line Euclidean distances. This allows it to "unfold" curved surfaces like the famous "Swiss Roll" dataset and reveal the true, lower-dimensional structure of the data [36]. Studies have shown that Isomap can produce better visualization and reveal clearer cluster structures of cancer tissue samples than PCA [35].

2. What are the typical computational requirements for Isomap and when might it be unsuitable?

Isomap's main computational burden arises from two steps: constructing the k-nearest neighbor graph and computing the shortest-path (geodesic) distances between all pairs of points in that graph. For very large datasets (e.g., containing hundreds of thousands of cells), this process can become slow and memory-intensive [36]. Furthermore, Isomap can be sensitive to its parameters, particularly the number of neighbors (n_neighbors) used to build the graph. If this parameter is not chosen properly, it can lead to erroneous connections (called "short-circuit errors") or an inaccurate representation of the manifold [36] [37]. It may also struggle with manifolds that have complex topological structures, such as holes [36].

3. How do I know if the low-dimensional embedding from Isomap is trustworthy?

Evaluating the quality of an embedding is crucial. Quantitative metrics can be used to assess performance [38] [39]:

- Local Structure Preservation: Measure how well the k-nearest neighbors of each point in the original high-dimensional space are preserved in the low-dimensional embedding. Isomap typically outperforms PCA on this metric [38].

- Global Structure Preservation: Evaluate the correlation between pairwise distances in the high-dimensional space and the low-dimensional embedding. PCA, which emphasizes large pairwise distances, may have a lower reconstruction error by this metric [38].

- Cluster Quality: Use metrics like the Silhouette Score to validate whether the embedding leads to well-separated clusters that correspond to known biological labels (e.g., cell types) [39].

4. My data has multiple experimental conditions. How can I integrate them for visualization?

For complex multi-condition experiments (e.g., treated vs. control samples), simple embedding of all data together may not be sufficient. Advanced methods like Latent Embedding Multivariate Regression (LEMUR) have been developed to integrate data from different conditions into a common latent space. This approach explicitly accounts for known covariates while estimating a shared low-dimensional manifold, allowing for counterfactual predictions and cluster-free differential expression analysis [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Cluster Separation in Low-Dimensional Visualization

Problem: After applying Isomap to your gene expression data, the resulting 2D/3D plot shows poor separation between known biological groups (e.g., healthy vs. diseased samples).

Solutions:

- Adjust the

n_neighborsparameter: This is the most critical hyperparameter. A value too low will make the embedding sensitive to noise, while a value too high may blur the fine-grained local structure. Test a range of values (e.g., from 5 to 50) and evaluate the results with the metrics mentioned above [36] [37]. - Preprocess your data appropriately: Ensure your gene expression data is properly normalized and log-transformed before applying Isomap. High variance in a few genes can dominate the distance calculation. Consider feature selection to remove non-informative genes [39].

- Try an alternative nonlinear method: If Isomap continues to perform poorly, the manifold assumption might not hold, or its sensitivity to parameters is a bottleneck. Consider other nonlinear methods like UMAP, which is often faster and can better preserve both local and global structure [41] [42] [43].

Issue 2: Long Computation Times with Large Datasets

Problem: Running Isomap on your single-cell RNA-seq dataset (with 100,000+ cells) is prohibitively slow.

Solutions:

- Subsample your data: For an initial exploratory analysis, run Isomap on a randomly selected subset of your cells (e.g., 10,000 points). This can help you quickly tune parameters and get a sense of the data structure [38].

- Leverage specialized tools for large data: The field of single-cell analysis is rapidly evolving. For very large datasets, consider using tools that are specifically designed for scalability, such as UMAP or PaCMAP [43].

- Check your implementation: Use efficient libraries like

scikit-learnwhich implement optimized algorithms for graph construction and shortest-path calculations [36] [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comparative Visualization of Gene Expression Data using PCA and Isomap

Objective: To compare the performance of PCA and Isomap in visualizing the cluster structure of a gene expression dataset (e.g., a cancer tissue sample dataset).

Materials:

- Dataset: A normalized gene expression matrix (e.g., from TCGA), often with shape

n_samples x n_genes. - Software/Libraries: Python with

scikit-learn,matplotlib,numpy, andpandas.

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Load the gene expression matrix and any associated sample metadata (e.g., cancer subtype labels).

- Apply standard preprocessing: normalize for sequencing depth and log-transform (e.g., log1p) to stabilize variance.

- (Optional) Perform feature selection to retain highly variable genes.

Dimensionality Reduction:

- PCA: Use

sklearn.decomposition.PCAwithn_components=2to fit and transform the data. - Isomap: Use

sklearn.manifold.Isomapwithn_components=2and a chosenn_neighbors(start with 10-30) to fit and transform the same data.

- PCA: Use

Visualization & Evaluation:

- Plot the 2D embeddings from both methods, coloring the points by their known labels from the metadata.

- Qualitatively assess the cluster separation and continuity.

- Quantitatively compare the embeddings using metrics like Silhouette Score and neighbor preservation (e.g., using

sklearn.metrics.silhouette_score).

The workflow for this comparative analysis is summarized in the following diagram:

Key Differences in Algorithmic Approach

The fundamental difference between PCA and Isomap lies in how they measure distances between data points, which is visualized in the logic below:

The following table summarizes findings from studies that quantitatively compared Isomap and PCA on biological data.

| Dataset / Context | Evaluation Metric | PCA Performance | Isomap Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray Data (10k points) [38] | Reconstruction Error (Global) | 9.3 | 616.1 | PCA better preserves large pairwise distances. |

| Microarray Data (10k points) [38] | k-NN Preservation (Local, k=5) | 0.0124 | 0.0190 | Isomap better preserves local neighborhood structure. |

| Cancer Tissue Samples [35] | Clustering Quality & Visualization | Moderate | Superior | Isomap provided clearer visualization and revealed more distinct cluster structures. |

| General Microarray Data [37] | Classification & Cluster Validation | Good (with many dimensions/genes) | Better in low dimensions | Isomap and LLE favorable for 2D/3D visualization with few differentially expressed genes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

scikit-learn (Python) |

Provides robust, easy-to-use implementations of both PCA (decomposition.PCA) and Isomap (manifold.Isomap), facilitating direct comparison [36]. |

| Normalized Gene Expression Matrix | The fundamental input data. Requires preprocessing (log transformation, normalization) to ensure technical artifacts do not dominate the dimensional reduction. |

| Cell Type / Condition Labels | Metadata (e.g., from pathologist annotation) crucial for the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the embedding quality [39]. |

| Jupyter Notebook / RStudio | An interactive computational environment ideal for exploratory data analysis, iterative parameter tuning, and visualization. |

Visualization Libraries (matplotlib, seaborn) |

Essential for creating static 2D and 3D scatter plots of the embeddings to visually assess cluster separation and data structure. |

Navigating Pitfalls: Strategies to Overcome Noise, Bias, and Confounding Factors

Technical Support Center & FAQs

Q1: What is the mean-correlation relationship bias in gene co-expression analysis, and why is it problematic?

A1: In RNA-seq data (both bulk and single-cell), a technical bias exists where the estimated correlation between pairs of genes depends on their observed expression levels. This creates a mean-correlation relationship, making highly expressed genes more likely to appear highly correlated [44]. This is problematic because it obscures biologically relevant correlations, especially among lowly expressed genes like transcription factors, potentially causing them to be missed in network analyses [44]. The relationship is not observed in protein-protein interaction data, confirming it's a technical artifact rather than true biology [44].

Q2: How can I detect if my dataset suffers from this bias?

A2: A straightforward diagnostic is to visualize the relationship between gene mean expression (e.g., median log2(RPKM)) and a summary of its correlation profile (e.g., the mean absolute correlation with all other genes). A positive trend indicates the presence of the bias. The bias is commonly observed across diverse tissues and technologies [44].

Q3: What is Spatial Quantile Normalization (SpQN), and how does it correct this bias?

A3: SpQN is a method developed to normalize local distributions within a gene-gene correlation matrix [44]. It addresses the binning challenge by:

- Sorting genes by their average expression level across samples.

- Grouping genes into a series of disjoint bins (e.g., 10 bins) from low to high expression.

- Applying a quantile normalization procedure across these bins for the correlation values associated with each gene, thereby removing the dependency of the correlation distribution on expression level [44]. After applying SpQN, the mean-correlation relationship is eliminated, allowing for unbiased network reconstruction [44].

Q4: What are the key steps in implementing SpQN for my co-expression analysis?

A4: Follow this experimental protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Start with your normalized expression matrix (e.g., log2(RPKM+0.5)). Filter out genes with very low median expression (e.g., median log2(RPKM) ≤ 0) [44].

- Confounder Removal: Regress out major sources of unwanted variation, such as batch effects, using principal component analysis (PCA). Scale the expression matrix so each gene has mean 0 and variance 1 across samples, then regress out the top

kPCs (e.g., 4 or a number determined bysva::num.sv()) to obtain a residual matrix [44]. - Correlation Matrix Calculation: Compute the Pearson correlation matrix from the residual expression matrix.

- Apply SpQN: Implement the SpQN algorithm on the correlation matrix as described in Q3. The genes must be sorted by their mean expression from the original preprocessed matrix (Step 1).

- Downstream Analysis: Use the normalized correlation matrix for network inference (e.g., using graphical lasso or WGCNA).

Q5: Are there alternative methods to handle nonlinear correlations in gene expression data?

A5: Yes. For cases where the biological relationship itself is nonlinear (not just a technical mean-correlation bias), other correlation measures can be employed. Kernelized Correlation (Kc) is a notable method that first transforms data via a kernel (e.g., Radial Basis Function) to a high-dimensional space before calculating classical correlation, effectively capturing nonlinear patterns [45]. Distance correlation (dCor) is another measure of dependence that can detect nonlinear associations, though it does not indicate the direction (positive/negative) of the relationship [45].

Q6: What common pitfalls should I avoid when applying normalization for co-expression?

A6:

- Ignoring Confounders: Always remove major technical and biological confounders (e.g., batch, cell cycle, top PCs) before calculating correlations. SpQN corrects the mean-bias in the correlation matrix but is not a substitute for this initial data cleaning [44].

- Incorrect Gene Ordering for SpQN: SpQN requires genes to be ordered by their mean expression. Using a different order (e.g., after PCA removal) will break the method's logic.

- Misinterpreting Nonlinearity: Distinguish between technical bias (addressed by SpQN) and true biological nonlinear correlation (which may require methods like Kc). Investigate top gene pairs visually.

Summary of Key Datasets and Performance

| Dataset Type | Example Source | Key Use in SpQN Development | Evidence of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq | GTEx (9 tissues) [44] | Primary benchmark for quantifying mean-correlation relationship and testing SpQN efficacy. | Strong positive relationship observed between gene mean expression and correlation strength. |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Mouse midblast cells [44] | Demonstrated the bias persists in single-cell data. | Relationship confirmed, making SpQN relevant for scRNA-seq co-expression. |

| Reference Data (PPI) | HuRI database [44] | Served as a biological negative control (no mean-expression relationship). | Used to argue the bias is technical, not biological. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SpQN Application

This protocol is based on the methodology described in the SpQN publication [44].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Bulk Data: Download read counts from a source like GTEx. Filter for protein-coding and long non-coding genes. Normalize to log2(RPKM) using the formula:

log2( (number of reads + 0.5) / (library size * gene length * 10^9) ). Filter genes with median log2(RPKM) > 0 [44]. - Single-cell Data: Use an RPKM or CPM normalized count matrix. Transform with

log2(RPKM + 0.5)orlog2(CPM + 1). Apply similar median expression filtering.

2. Removal of Unwanted Variation:

- Scale the expression matrix (genes as rows, samples as columns) so that each gene has a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

- Perform PCA on the scaled matrix. Determine the number of significant principal components (

k) to remove using a statistical method (e.g.,num.svfrom thesvaR package) [44]. - Regress out the top

kPCs. The resulting residual matrix is used for all correlation calculations.

3. Construction and Normalization of Correlation Matrix:

- Calculate the Pearson correlation matrix (

C) from the residual matrix. - Compute the mean expression vector (

M) for all genes from the original filtered, log-normalized matrix (Step 1). - Implement SpQN Algorithm:

- Sort the gene order (rows/columns of

C) based onM, from lowest to highest mean expression. - Partition the sorted genes into

Bcontiguous bins (e.g., B=10). - For each gene

i, its correlation vector (rowiofC) contains correlations with all other genes. The values in this vector are split according to the bin membership of the target genes. - For each bin

b, collect the corresponding correlation sub-vectors from all genes. Perform quantile normalization across these sub-vectors. This replaces the correlation values in each gene's sub-vector for binbwith the normalized values. - Reassemble the fully normalized correlation vector for each gene from the normalized sub-vectors. This results in the SpQN-normalized correlation matrix.

- Sort the gene order (rows/columns of

4. Downstream Network Analysis:

- Use the SpQN-normalized matrix for network inference tools like graphical lasso (e.g., using the

QUICR package) [44] or WGCNA [44].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Workflow for Applying SpQN to Co-expression Analysis

Core Logic of Spatial Quantile Normalization (SpQN)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose in Analysis |

|---|---|

| GTEx Bulk RNA-seq Data | A foundational resource for benchmarking co-expression methods in human tissues, used to initially characterize the mean-correlation bias [44]. |

| Single-cell RNA-seq Dataset (e.g., Mouse midblast) | Used to validate the presence and correction of the mean-correlation bias in single-cell resolution data [44]. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Data (e.g., HuRI database) | Serves as a biological "ground truth" control. The absence of a mean-expression relationship in PPI networks helps confirm the technical nature of the observed bias in correlation networks [44]. |

R Packages: WGCNA, sva, QUIC |

WGCNA for network construction and PCA-based confounder removal [44]; sva for determining the number of confounding factors [44]; QUIC for implementing the graphical lasso for network inference [44]. |

| Spatial Quantile Normalization (SpQN) Algorithm | The core computational tool to remove the expression-level-dependent bias from gene-gene correlation matrices, enabling fairer network analysis [44]. |

| Kernelized Correlation (Kc) Measure | An alternative tool for quantifying true biological nonlinear correlations between gene pairs, useful when investigating specific nonlinear dynamic relationships [45]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Handling Technical Noise in Data

Q: My gene expression data has high technical noise. What are the primary engineering and computational solutions to mitigate this?

Technical noise from laboratory equipment, HVAC systems, and other mechanical sources can significantly corrupt sensitive gene expression measurements. The table below summarizes established and emerging noise control technologies.

Table 1: Solutions for Mitigating Technical Noise

| Technology | Principle | Best For | Noise Reduction Efficacy | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Noise Control (ANC) [46] | Uses microphones and speakers to generate "anti-noise" sound waves that cancel out low-frequency noise. | Low-frequency hum from incubators, freezers, and HVAC systems. | Highly effective for predictable, low-frequency sounds. | Performance can be environment-dependent. |

| Acoustic Metamaterials [46] [47] | Engineered structures with patterned elements that block specific sound frequencies while allowing air flow. | Noise from ventilation fans and air handling units in equipment rooms. | Can block 94% of incoming sound in specific frequency bands [46]. | Often customized for target frequencies. |

| Nanotechnology Insulation [46] | Uses nanofibers to create materials with a high sound-absorbing surface area. | General lab ambient noise; can be integrated into equipment panels and enclosures. | Can double the noise efficiency of standard acoustic insulation [46]. | Higher cost than traditional insulation. |

| Periodic Noise Barriers [47] | Arrays of scatterers (e.g., nested structures) that create bandgaps where sound waves cannot propagate. | Traffic or industrial noise affecting lab environments. | A peak noise reduction of 16 dB has been demonstrated without sound-absorbing materials [47]. | Can be optimized with porous materials or micro-perforated panels. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Low-Noise Laboratory Environment

- Baseline Measurement: Use a calibrated sound level meter to map acoustic levels across the lab, particularly near sensitive equipment like PCR machines and sequencers [48].

- Identify Sources: Correlate noise spikes with specific equipment operational states (e.g., compressor cycles, fan speeds).

- Select and Implement Controls: Based on frequency analysis, deploy solutions from Table 1. For low-frequency hum, consider ANC panels; for broadband noise, consider nanostructured acoustic insulation.

- Post-Implementation Validation: Re-measure sound levels to confirm noise reduction and ensure no new vibrational or acoustic artifacts have been introduced.

Addressing Low Sample Sizes

Q: I am working with a rare cell type and have a very small sample size. What statistical and experimental strategies can I use to maintain power?

Small sample sizes are a common challenge in specialized research areas. The goal is to maximize information extraction from every data point.

Table 2: Strategies for Research with Low Sample Sizes

| Strategy | Methodology | Potential Sample Size Reduction | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stratification [49] | Dividing the sample into homogeneous subgroups (strata) before analysis to reduce variability. | 0 - 20% | Requires prior knowledge of key covariates. |

| Enrichment [49] | Selecting a patient/subject population that is more homogeneous or more likely to show a response. | 0 - 20% | Improves power but may reduce generalizability of findings. |

| Pairwise Comparisons [49] | Using each subject as their own control (e.g., analyzing change from baseline). | 0 - 30% | Reduces variability from inter-subject differences. |

| Sustained Response [49] | Requiring that a response be confirmed over multiple observations or time points. | 0 - 25% | Filters out transient, noisy responses. |

| Adaptive Sample Size Re-Estimation [50] | A pre-planned interim analysis calculates conditional power, and the sample size can be increased if results are in a "promising zone." | Variable | Requires complex trial design but protects against underpowering when the initial treatment effect estimate is uncertain. |

Experimental Protocol: Designing a Study with Anticipated Low N

- Pre-Experimental Optimization:

- Enrichment: Define inclusion criteria to select subjects most likely to exhibit a clear biological signal (e.g., specific disease subtype, high baseline severity) [49].

- Stratification: Identify key covariates (e.g., age, sex, genetic background) and plan to stratify randomization and/or include them in the final model.

- Assay Selection:

- Statistical Analysis Plan:

- Pre-specify the use of correlation coefficients capable of capturing nonlinear relationships, such as the Clustermatch Correlation Coefficient (CCC), to maximize the chance of detecting complex gene-gene interactions [7].

- Plan for covariate adjustment in the final model to account for residual imbalances and reduce unexplained variance [49].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Nonlinear Gene Expression Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ARCHS4 Database [51] | A repository of standardized RNA-Seq data from thousands of studies, used for validating co-expression findings or as a background dataset. |

| Correlation AnalyzeR Tool [51] | A web-based platform for exploring tissue- and disease-specific gene co-expression correlations to predict gene function and relationships. |

| Clustermatch Correlation Coefficient (CCC) [7] | A "not-only-linear" correlation coefficient that uses clustering to efficiently detect both linear and nonlinear associations in genome-scale data. |

| scGPT / scFoundation Models [52] | Deep-learning foundation models trained on single-cell transcriptomics data that can be fine-tuned to predict the effects of genetic perturbations. |