Benchmarking Network Inference Algorithms: A Practical Guide for Disease Mechanism Research and Drug Discovery

Accurately inferring biological networks from high-throughput data is crucial for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets.

Benchmarking Network Inference Algorithms: A Practical Guide for Disease Mechanism Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Accurately inferring biological networks from high-throughput data is crucial for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets. This article provides a comprehensive benchmarking framework for network inference algorithms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational challenges in metabolomic and gene regulatory network inference, evaluate a suite of state-of-the-art methodological approaches from correlation-based to causal inference models, and address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world data. Finally, we present rigorous validation paradigms and comparative analyses, including insights from large-scale benchmarks like CausalBench, to guide the selection and application of these algorithms for robust and biologically meaningful discoveries in biomedical research.

The Core Challenge: Why Inferring Accurate Biological Networks from Disease Data is Inherently Difficult

The accurate inference of biological networks—whether gene regulatory or metabolic—is fundamental to advancing our understanding of disease mechanisms and accelerating drug discovery. However, the reliability of these inferred networks is often compromised by several persistent obstacles. This guide objectively compares the performance of various network inference algorithms, with a specific focus on how they contend with the trio of key challenges: small sample sizes, the presence of confounding factors, and the difficulty in distinguishing direct from indirect interactions. By synthesizing evidence from recent, rigorous benchmarks, we provide a clear-eyed view of the current state of the art, equipping researchers with the data needed to select and develop more robust methods for disease data research.

The Core Obstacles in Network Inference

The process of deducing network connections from biological data is inherently challenging. Three major obstacles consistently limit the accuracy and reliability of the inferred networks:

- Small Sample Sizes: High-dimensional biological data, where the number of features (e.g., genes, metabolites) far exceeds the number of samples, remains a principal hurdle. One study noted that this issue is compounded by the difficulty in distinguishing direct interactions from spurious correlations, a problem not solved simply by increasing sample numbers but rather by a fundamental limitation of some inference methods [1].

- Confounding Factors: Biological systems are dynamic and subject to numerous unmeasured variables. Network inference algorithms often rely on simplifying assumptions, such as linear relationships and steady-state conditions, to make computations tractable. However, these assumptions frequently fail to capture the true complexity of biological systems, which are nonlinear and affected by experimental noise [1].

- Indirect Interactions: A critical task in network inference is to identify direct regulatory or metabolic relationships. The prevalence of indirect interactions—where two molecules correlate not because of a direct link but through a shared connection to a third—poses a significant challenge. Inferred connections often reflect these correlations rather than true causal relationships, necessitating careful interpretation and experimental validation [1].

Benchmarking Methodologies: A Guide to Experimental Protocols

To objectively evaluate how algorithms perform under these obstacles, researchers have developed sophisticated benchmarking suites and simulation models. The following protocols represent the current gold standard for assessment.

The CausalBench Framework for Gene Regulatory Networks

CausalBench is a benchmark suite designed to revolutionize network inference evaluation by using real-world, large-scale single-cell perturbation data, moving beyond traditional synthetic datasets [2].

- Data Curation: The benchmark is built on two large-scale perturbational single-cell RNA sequencing datasets (RPE1 and K562 cell lines), comprising over 200,000 interventional data points. These datasets involve knocking down specific genes using CRISPRi technology and measuring whole transcriptome expression in individual cells under both control and perturbed states [2].

- Evaluation Metrics: Since the true causal graph is unknown in real-world data, CausalBench employs a dual evaluation strategy [2]:

- Biology-driven Evaluation: Uses an approximation of ground truth based on known biology to calculate precision and recall of the inferred networks.

- Statistical Evaluation: Leverages causal effect estimation to compute the Mean Wasserstein distance (measuring the strength of predicted causal effects) and the False Omission Rate (FOR, measuring the rate at which true interactions are omitted). These metrics complement each other in a precision-recall trade-off.

- Algorithms Tested: The suite evaluates a wide range of methods, including observational approaches (PC, GES, NOTEARS, GRNBoost2, SCENIC) and interventional methods (GIES, DCDI, and top performers from the CausalBench challenge like Mean Difference and Guanlab) [2].

The Simulated Metabolic Network for Metabolomics

A separate benchmark addresses the challenges specific to metabolomic network inference by using a generative computational model with a known ground truth [1] [3].

- Network Simulation: The benchmark uses a simulated model of Arachidonic Acid (AA) metabolism, comprising 83 metabolites and 131 reactions. Reactions are formulated as ordinary differential equations using Michaelis-Menten kinetics and mass action laws. The model generates in-silico samples by randomizing initial reaction parameters and running simulations to steady state, producing vectors of metabolite concentrations [1].

- Evaluation Metrics: Performance is assessed at two levels [1]:

- Pairwise Interaction Measures: Includes Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), which are more informative than AUROC for imbalanced, sparse networks.

- Network-Scale Analysis: Uses graph-theoretic centrality measures to compare the overall connectivity structure of the inferred network against the ground-truth network.

- Algorithms Tested: The study benchmarks a range of correlation- and regression-based network inference algorithms (NIAs) [1].

Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods

The following tables summarize the quantitative performance of various network inference methods as reported in recent, large-scale benchmarks.

Performance on Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) Inference

Table 1: Performance of GRN inference methods on the CausalBench suite (K562 and RPE1 cell lines). Performance is a summary of trends reported in the benchmark [2].

| Method Class | Specific Method | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational | PC, GES, NOTEARS | Established theoretical foundations | Limited information extraction from data; poor scalability |

| Tree-based | GRNBoost2 | High recall on biological evaluation | Achieves high recall at the cost of low precision |

| Interventional | GIES, DCDI variants | Designed for perturbation data | Does not consistently outperform observational methods on real-world data |

| Challenge Winners | Mean Difference, Guanlab | Top performance on statistical and biological evaluations | Performance represents a trade-off between precision and recall |

Performance on Metabolic Network Inference

Table 2: Ability of network inference algorithms (NIAs) to recover a simulated metabolic network across different sample sizes. Performance trends are based on [1].

| Algorithm Type | Sample Size Sensitivity | Accuracy in Recovering True Network | Utility for State Discrimination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | High sensitivity to small sample sizes | Fails to converge to the true underlying network, even with large samples | Can discriminate between different overarching metabolic states |

| Regression-based | High sensitivity to small sample sizes | Fails to converge to the true underlying network, even with large samples | Limited in identifying direct pathway changes |

A consistent finding across benchmarks is the inherent trade-off between precision and recall. Methods that successfully capture a high percentage of true interactions (high recall) often do so at the expense of including many false positives (low precision). Conversely, methods with high precision may miss many true interactions. This trade-off was explicitly highlighted in the CausalBench evaluation, where, for example, GRNBoost2 achieved high recall but low precision, while other methods traded these metrics differently [2].

Furthermore, contrary to theoretical expectations, the inclusion of interventional data does not guarantee superior performance. In the CausalBench evaluation, methods using interventional information did not consistently outperform those using only observational data, a finding that stands in stark contrast to results obtained on fully synthetic benchmarks [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, datasets, and software tools for benchmarking network inference methods.

| Item | Type | Function in Benchmarking | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| CausalBench Suite | Software & Dataset | Provides a standardized framework with real-world single-cell perturbation data and biologically-motivated metrics to evaluate GRN inference methods. | GitHub: causalbench/causalbench [2] |

| Simulated Arachidonic Acid (AA) Metabolic Model | In-silico Model | Serves as a known ground-truth network with 83 metabolites and 131 reactions to assess the accuracy of metabolic NIAs. | GitHub: TheCOBRALab/metabolicRelationships [1] [3] |

| Perturbational scRNA-seq Datasets (RPE1, K562) | Biological Dataset | Provides large-scale, real-world interventional data (CRISPRi perturbations) for benchmarking in a biologically relevant context. | Integrated into the CausalBench suite [2] |

| BEELINE Framework | Software | A previously established benchmark for evaluating GRN inference methods from single-cell data. | GitHub: Murali-group/Beeline [4] |

Analysis of Findings and Future Directions

The collective evidence from these benchmarks indicates that current network inference methods, while useful, are not yet "fit for purpose" for robustly and accurately reconstructing biological networks from experimental data alone. The obstacles of small sample sizes, confounding factors, and indirect interactions remain significant.

A critical insight is that poor scalability is a major limiting factor for many classical algorithms. The CausalBench evaluation highlighted how the scalability of a method directly impacts its performance on large-scale, real-world datasets. Methods that perform well on smaller, synthetic datasets often fail to maintain this performance when applied to the complexity and scale of real biological data [2].

Another key takeaway is the divergence between synthetic and real-world benchmark results. The finding that interventional methods do not reliably outperform observational methods on real data underscores the critical importance of benchmarking with real-world or highly realistic simulated data [2]. Similarly, the metabolic network study concluded that correlation-based inference fails to recover the true network even with large sample sizes, suggesting a fundamental limitation of the approach rather than a simple data scarcity issue [1].

Future progress will likely depend on the development of methods that are both computationally scalable and capable of better integrating diverse data types, such as prior knowledge of known interactions, to constrain the inference problem. Furthermore, the community-wide adoption of rigorous, standardized benchmarks like CausalBench is essential for tracking genuine progress and avoiding over-optimism based on synthetic performance [2].

In computational biology, particularly for disease data research and early-stage drug discovery, the paramount goal is to map causal gene-gene interaction networks. These networks, or "wiring diagrams," of cellular biology are fundamental for identifying disease-relevant molecular targets [5]. However, evaluating the performance of network inference algorithms designed to reconstruct these graphs faces a profound epistemological and practical challenge: the ground truth problem. In real-world biological systems, the true causal graph is unknown due to the immense complexity of cellular processes [5]. For years, the field has relied on synthetic datasets—algorithmically generated networks with known structure—for method development and evaluation. This practice, while convenient, has created a dangerous reality gap, where methods that excel on idealized synthetic benchmarks falter when applied to real, messy biological data [5] [6].

This guide objectively compares the performance of network inference algorithms trained and evaluated on synthetic data versus those validated on real-world interventional data. We frame this within the critical context of benchmarking for disease research, synthesizing evidence from large-scale studies to illustrate how an over-reliance on synthetic data can distort progress and obscure methodological limitations.

The Synthetic vs. Real-World Data Dichotomy in Network Inference

The limitations of synthetic data are not merely a matter of imperfect simulation; they strike at the core of what makes biological inference uniquely challenging.

| Aspect | Synthetic Data (Algorithmic Benchmarks) | Real-World Biological Data (e.g., Single-Cell Perturbation) |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth | Known and perfectly defined by the generator. | Fundamentally unknown; must be approximated through biological metrics [5]. |

| Complexity & Noise | Contains simplified, controlled noise models. | Carries natural, unstructured noise, technical artifacts, and unscripted biological variability [7] [5]. |

| Causal Relationships | Relationships are programmed, often linear or with simple dependencies. | Involves non-linear, context-dependent, and emergent interactions within complex systems [8] [5]. |

| Edge Cases & Rare Patterns | Can be generated on demand but may lack authentic biological plausibility. | Rare patterns appear organically but are scarce and costly to capture [7] [9]. |

| Evaluation Basis | Direct comparison to a known graph (Precision, Recall, F1). | Indirect evaluation via biologically-motivated metrics and statistical causal effect estimates [5]. |

| Primary Risk | Models may learn to exploit the simplifying assumptions of the generator, leading to poor generalization—the reality gap [5] [9]. | Data scarcity, cost, and the absence of a clear "answer key" complicate validation [5]. |

A pivotal finding from recent research underscores this gap: methods that leverage interventional data do not consistently outperform those using only observational data on real-world benchmarks, contrary to expectations set by synthetic evaluations [5]. This indicates that theoretical advantages may not translate, and synthetic benchmarks fail to capture the challenges of utilizing interventional signals in real biological systems.

Benchmarking Performance: Quantitative Results from CausalBench

The introduction of benchmarks like CausalBench, which uses large-scale, real-world single-cell perturbation data from CRISPRi experiments, has enabled a direct performance comparison [5]. The table below summarizes key findings from an evaluation of state-of-the-art network inference methods, highlighting the trade-offs inherent in the absence of clear ground truth.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Network Inference Methods on CausalBench Real-World Data [5]

| Method Category | Example Methods | Key Strength on Real-World Data | Key Limitation on Real-World Data | Note on Synthetic Benchmark Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Causal | PC, GES, NOTEARS variants | Foundational constraints-based or score-based approaches. | Often extract very little signal; poor scalability limits performance on large datasets. | Traditionally evaluated on synthetic graphs; performance metrics not predictive of real-world utility. |

| Interventional Causal | GIES, DCDI variants | Extensions designed to incorporate interventional data. | Did not outperform observational counterparts on CausalBench, highlighting a scalability and utilization gap. | Theoretical superiority on synthetic interventional data does not translate. |

| Tree-Based GRN Inference | GRNBoost, SCENIC | Can achieve high recall of biological interactions. | Low precision; SCENIC's restriction to TF-regulon interactions misses many causal links. | Less commonly featured in purely synthetic causal discovery benchmarks. |

| Challenge-Derived (Interventional) | Mean Difference, Guanlab, Catran | Top performers on CausalBench; effectively balance precision and recall in biological/statistical metrics. | Developed specifically for the real-world benchmark, emphasizing scalability and interventional data use. | N/A: Methods developed in response to the limitations of synthetic benchmarks. |

| Other Challenge Methods | Betterboost, SparseRC | Good performance on statistical evaluation metrics. | Poorer performance on biologically-motivated evaluation, underscoring the need for dual evaluation. | Demonstrates that optimizing for one metric type (statistical) can come at the cost of biological relevance. |

The results demonstrate a critical point: performance rankings shift dramatically when moving from synthetic to real-world evaluation. Simple, scalable methods like Mean Difference can outperform sophisticated causal models in this realistic setting [5]. This inversion challenges the "garbage in, garbage out" axiom, suggesting that for generalization, the "variability in the simulator" may be more important than pure representational accuracy [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Benchmark Validation

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear toolkit for researchers, we detail the core methodologies underpinning the conclusive benchmark findings cited above.

Protocol 1: The CausalBench Evaluation Framework [5]

- Data Curation: Utilize two large-scale perturbational single-cell RNA-seq datasets (RPE1 and K562 cell lines). Data consists of gene expression measurements from individual cells under control (observational) and CRISPRi-mediated knockdown (interventional) conditions.

- Ground Truth Approximation: Acknowledge the true causal graph is unknown. Implement two complementary evaluation strategies:

- Biology-Driven Evaluation: Compare predicted gene-gene interactions against prior biological knowledge from curated databases to compute precision and recall.

- Statistical Causal Evaluation: Use interventional data as a gold standard for estimating causal effects. Compute:

- Mean Wasserstein Distance: Measures if predicted interactions correspond to strong empirical causal effects.

- False Omission Rate (FOR): Measures the rate at which true causal interactions are omitted by the model.

- Method Training & Evaluation: Train each network inference method on the full dataset across multiple random seeds. Generate a ranked list of predicted edges for each method.

- Performance Aggregation: Calculate evaluation metrics (Precision, Recall, F1 for biological; Mean Wasserstein and FOR for statistical) for each method. Analyze the inherent trade-off between precision and recall, and between identifying strong effects (high Mean Wasserstein) and missing few true effects (low FOR).

Protocol 2: Validating Synthetic Data Fidelity (For Hybrid Approaches) [10] When synthetic data is generated to augment real datasets, its quality must be rigorously validated before integration.

- Distribution Similarity:

- For continuous features, apply the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. A score closer to 1 indicates higher similarity between synthetic and real distributions.

- For categorical features, calculate the Total Variation Distance (TVD). Similarly, a score near 1 indicates close replication.

- Coverage Validation:

- Range Coverage: Verify that synthetic continuous values remain within the min/max range of the original data.

- Category Coverage: Ensure all categorical values from the original data are represented in the synthetic set.

- Missing Data Replication: Assess Missing Values Similarity to ensure the synthetic data replicates the pattern of missingness (e.g., Missing Not At Random patterns) present in the original dataset.

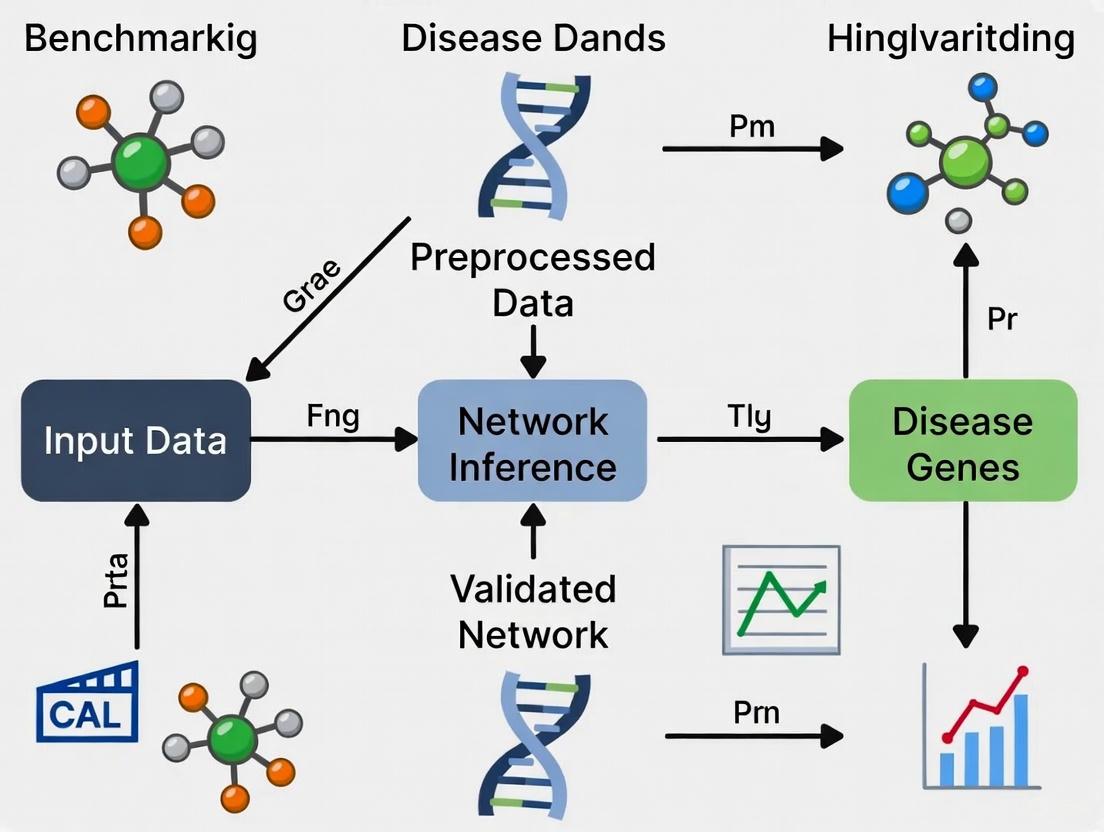

Visualizing the Benchmarking Workflow and Reality Gap

The following diagrams, created with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core conceptual and experimental frameworks discussed.

Diagram 1: The Reality Gap Between Synthetic and Real-World Evaluation Paradigms

Diagram 2: CausalBench Experimental Workflow for Real-World Network Inference

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The transition to robust, real-world benchmarking requires specific data and analytical "reagents." The table below details essential components for research in this domain.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Benchmarking Network Inference

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Perturbational scRNA-seq Data | Real-World Dataset | Provides the foundational real-world interventional data lacking a known graph, enabling realistic benchmarking. | RPE1 and K562 cell line data from Replogle et al. (2022), integrated into CausalBench [5]. |

| CausalBench Benchmark Suite | Software Framework | Provides the infrastructure, curated data, baseline method implementations, and biologically-motivated metrics to standardize evaluation. | Open-source suite available at github.com/causalbench/causalbench [5]. |

| Biologically-Curated Interaction Databases | Prior Knowledge Gold Standard | Serves as a proxy for ground truth to compute precision/recall in biological evaluations (e.g., for transcription factor targets). | Databases like TRRUST, Dorothea, or cell-type specific pathway databases. |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Algorithmic Tool | Generates networks with known ground truth for initial method development, stress-testing, and understanding fundamental limits. | Network models: Erdős-Rényi (ER), Barabási-Albert (BA), Stochastic Block Model (SBM) [11]. |

| Statistical Similarity Metrics | Analytical Tool | Quantifies the fidelity of synthetic data generated to augment real datasets, ensuring safe integration. | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Total Variation Distance, Coverage Metrics [10]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | Essential for scaling methods to large real-world datasets (10^5+ cells, 1000s of genes) and running extensive benchmarks. | GPU/CPU clusters for training scalable models like those in the CausalBench challenge [5]. |

Network inference, the process of reconstructing regulatory interactions between molecular components from data, is fundamental to understanding complex biological systems and developing new therapeutic strategies for diseases. The performance of inference algorithms is heavily influenced by their underlying mathematical assumptions. This guide provides an objective comparison of how three common assumptions—linearity, steady-state, and sparsity—impact algorithm performance, based on recent benchmarking studies and experimental data.

Core Concepts and Algorithmic Trade-Offs

Biological networks are intrinsically non-linear and dynamic. However, many inference methods rely on simplifying assumptions to make the complex problem of network reconstruction tractable. The choice of assumption involves a trade-off between biological realism, computational feasibility, and the type of experimental data available.

- Linearity: Assumes relationships between nodes can be modeled with linear functions. This simplifies computation but fails to capture essential non-linear behaviors like ultrasensitivity or saturation, common in biochemical reactions [12].

- Steady-State: Assumes data are collected after a system has reached equilibrium, ignoring transitional dynamics. This reduces experimental complexity but can obscure the directionality of causal interactions [13].

- Sparsity: Assumes that each network node is connected to only a few others. This reflects the biological reality that most genes or proteins have limited regulators, which helps to constrain the inference problem and improve accuracy [12] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the type of data used, the core assumptions, and the resulting algorithmic strengths and limitations.

Performance Comparison Across Assumptions

Quantitative benchmarking is essential for understanding how algorithms perform under different assumptions. The table below synthesizes data from multiple studies that evaluated inference methods using performance metrics like the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) and the Edge Score (ES), which measures confidence in inferred edges against null models [15] [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Algorithm Classes Based on Key Assumptions

| Algorithm Class / Representative Example | Core Assumption(s) | Reported Performance (AUPR / F1 Score) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression-based (e.g., TIGRESS) | Linearity, Sparsity | F1: 0.21-0.38 (K562 cell line) [5] | Computationally efficient; works well with weak perturbations [13]. | Struggles with ubiquitous non-linear biology; can infer spurious edges [12]. |

| Non-linear/Kinetic (e.g., Goldbeter-Koshland) | Non-linearity, Sparsity | Superior topology estimation vs. linear [12] | Captures saturation, ultrasensitivity; more biologically plausible [12]. | Requires more parameters; computationally intensive. |

| Steady-State MRA | Steady-State, Sparsity | N/A (Theoretical framework) [13] | Handles cycles and directionality; infers signed edges [13]. | Requires specific perturbation for each node; sensitive to noise [13]. |

| Dynamic (e.g., DL-MRA) | Dynamics, Sparsity | High accuracy for 2 & 3-node networks [13] | Infers directionality, cycles, and external stimuli; uses temporal information [13]. | Data requirements scale with network size; requires carefully timed measurements [13]. |

| Tree-Based (e.g., GENIE3) | Non-linearity, Sparsity | ES: Varies by context [15] | Top performer in DREAM challenges; robust to non-linearity. | Performance is highly dependent on data resolution and noise [15]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

Understanding the experimental setups that generate benchmarking data is crucial for interpreting performance claims.

Benchmarking with In Silico Networks and Steady-State Data

Objective: To compare the accuracy of network topology inference between linear models and non-linear, kinetics-based models using steady-state data [12].

- Synthetic Data Generation: A known ground-truth network topology is defined. For non-linear benchmarks, data is simulated using ODEs based on chemical kinetics like Goldbeter–Koshland kinetics, which model highly non-linear behaviors such as ultrasensitivity in protein phosphorylation [12].

- Linear Model Inference: Statistical linear models are applied to the synthetic data to infer the network edges.

- Kinetics-Based Inference: A Bayesian statistical model is used, where the functional relationships between nodes are derived from the equilibrium analysis of the non-linear kinetics. Inference over potential parent sets (network topology) is often performed using methods like Reversible-Jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo (RJMCMC) [12].

- Performance Assessment: The inferred network from each method is compared against the known ground-truth topology. The kinetics-based approach has been shown to be more effective at estimating network topology than linear methods, which can be biased by model misspecification [12].

Evaluating Algorithm Performance with Confidence Metrics

Objective: To systematically evaluate how factors like regulatory kinetics, noise, and data sampling affect diverse inference algorithms, using metrics that do not require a gold-standard network [15].

- In Silico Testbed: A concise, well-defined network (e.g., 5-node) is simulated, incorporating various regulatory logic gates (AND, OR), kinetic parameters, and dynamic stimulus profiles [15].

- Algorithm Panel: A panel of algorithms spanning different statistical methods is selected (e.g., Random Forests/GENIE3, regression/TIGRESS, dynamic Bayesian/BANJO, mutual information/MIDER) [15].

- Null Model Generation: The original data is shuffled across specific dimensions (e.g., gate/motif, nodes, stimulus conditions) to generate multiple null datasets where true correlations are broken [15].

- Metric Calculation: For each potential edge, the inferred weight (IW) from the true data is compared to the distribution of null weights (NW) from the permuted datasets.

Large-Scale Benchmarking with Real-World Perturbation Data

Objective: To assess the performance of network inference methods on large-scale, real-world single-cell perturbation data, where the true causal graph is unknown [5].

- Dataset Curation: Large-scale perturbational single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets are curated (e.g., from CRISPRi screens in RPE1 and K562 cell lines). These contain thousands of gene expression measurements from both control (observational) and genetically perturbed (interventional) cells [5].

- Method Evaluation: A suite of state-of-the-art methods, including both observational (PC, GES, NOTEARS) and interventional (GIES, DCDI), are evaluated [5].

- Performance Metrics:

- Biology-Driven Evaluation: The precision and recall of predicted edges are assessed against a community-accepted, biologically-motivated approximation of a ground-truth network [5].

- Statistical Evaluation: Causal effects are empirically estimated from the interventional data.

The workflow for this large-scale, real-world benchmarking is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful network inference relies on a combination of computational tools and carefully designed experimental reagents.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Resources for Network Inference Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Network Inference | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi/a Screening Libraries | Enables large-scale genetic perturbations (knockdown/activation) to generate interventional data for causal inference. | Used in benchmarks like CausalBench to perturb genes in cell lines (e.g., RPE1, K562) [5]. |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Measures genome-wide gene expression at single-cell resolution, capturing heterogeneity essential for inferring regulatory relationships. | The primary data source for modern benchmarks; platforms like 10x Genomics are standard [14] [5]. |

| Gold-Standard Reference Networks | Provides a "ground truth" for objective performance evaluation of algorithms on synthetic data. | Tools like GeneNetWeaver and Biomodelling.jl simulate realistic expression data from a known network [15] [14]. |

| Kinetic Model Simulators | Generates synthetic time-course data based on biochemical kinetics to test dynamic and non-linear inference methods. | ODE modeling of Goldbeter–Koshland kinetics or other signaling models [12] [13]. |

| Imputation Software | Addresses technical zeros (drop-outs) in scRNA-seq data, which can distort gene-gene correlation and hinder inference. | Methods like MAGIC, SAVER; performance varies and should be benchmarked [14]. |

Discussion and Strategic Recommendations

The benchmarking data reveals that no single algorithm or assumption is universally superior. The choice depends on the biological context, data type, and research goal.

- For Causal Discovery with Large-Scale Data: Methods that leverage interventional data (e.g., from CRISPR screens) are indispensable. Surprisingly, on real-world data, interventional methods do not always outperform high-quality observational methods, highlighting a gap between theory and practice [5]. Scalability is a major limiting factor for many classical methods [5].

- For Capturing Biological Realism: When studying systems with known strong non-linearities (e.g., signaling pathways), kinetics-based or non-linear models (like those using Goldbeter–Koshland kinetics) are more accurate than linear models, which can produce biased and inconsistent estimates [12].

- For Dynamic Systems: Time-course inference methods (e.g., DL-MRA) are necessary to uncover the directionality of edges, feedback loops, and the effects of external stimuli, which are invisible to steady-state analyses [13]. The trade-off is a more complex and costly experimental design.

- The Critical Role of Sparsity: The sparsity assumption is a powerful regularizer that is empirically valid for most biological networks and is leveraged by nearly all high-performing methods to constrain the inference problem and improve accuracy [12] [14].

In conclusion, benchmarking studies consistently show that aligning an algorithm's core assumptions with the properties of the biological system and the available data is paramount. Researchers should prioritize methods whose strengths match their specific experimental data and inference goals, whether that involves leveraging large-scale interventional datasets for causal discovery or employing dynamic, non-linear models for mechanistic insight into disease pathways.

In the field of computational biology, accurately mapping gene regulatory networks is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets. The advent of large-scale single-cell perturbation technologies has generated vast datasets capable of illuminating these complex causal interactions. However, the true challenge lies not in data generation, but in rigorously evaluating the computational methods designed to infer these networks. Establishing a clear, standardized framework for assessment is critical for progress. This guide provides an objective overview of the current landscape of network inference evaluation metrics, focusing on their application to real-world biological data in disease research. It introduces key benchmarking suites, details their constituent metrics and experimental protocols, and compares the performance of state-of-the-art methods to equip researchers with the tools needed to define and achieve success.

The Benchmarking Landscape: Moving Beyond Synthetic Data

Evaluating network inference methods in real-world environments is challenging due to the lack of a fully known, ground-truth biological network. Traditional evaluations relying on synthetic data have proven inadequate, as they do not reflect method performance on complex, real-world systems [5]. This gap has led to the development of benchmarks that use real large-scale perturbation data with biologically-motivated and statistical metrics to provide a more realistic and reliable evaluation [5].

A transformative tool in this space is CausalBench, the largest openly available benchmark suite for evaluating network inference methods on real-world interventional single-cell data [5]. It builds on two large-scale perturbation datasets (RPE1 and K562 cell lines) containing over 200,000 interventional data points where specific genes are knocked down using CRISPRi technology [5]. Since the true causal graph is unknown, CausalBench employs a dual evaluation strategy:

- Biology-Driven Evaluation: Uses biologically approximated ground truth to assess how well the predicted network represents underlying complex processes.

- Quantitative Statistical Evaluation: Leverages comparisons between control and treated cells to compute inherently causal statistical metrics.

Core Evaluation Metrics and Methodologies

The performance of network inference methods is measured through a set of complementary metrics that capture different aspects of accuracy and reliability.

Key Statistical Metrics in CausalBench

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Wasserstein Distance | Measures the extent to which a method's predicted interactions correspond to strong causal effects [5]. | A lower distance indicates the method is better at identifying interactions with strong causal effects. |

| False Omission Rate (FOR) | Measures the rate at which truly existing causal interactions are omitted (missed) by the model's predicted network [5]. | A lower FOR indicates the method misses fewer real interactions (higher recall of true positives). |

There is an inherent trade-off between maximizing the mean Wasserstein distance and minimizing the FOR, similar to the precision-recall trade-off [5].

Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking

A rigorous benchmarking experiment using a suite like CausalBench involves several critical steps to ensure fair and meaningful comparisons.

The workflow for a comprehensive benchmark, as conducted with CausalBench, involves selecting real-world perturbation datasets and a representative set of network inference methods [5]. Models are trained on the full dataset, and their predicted networks are evaluated against the benchmark's curated metrics. This process is typically repeated multiple times with different random seeds to ensure statistical robustness [5]. The final, crucial step is to analyze the results, paying particular attention to the trade-offs between metrics like precision and recall or FOR and mean Wasserstein distance [5].

Comparative Analysis of Network Inference Methods

Systematic evaluations using benchmarks like CausalBench reveal the relative strengths and weaknesses of different algorithmic approaches. The table below summarizes the performance of various methods, categorized as observational, interventional, or those developed through community challenges.

Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods on CausalBench

| Method Category | Method Name | Key Characteristics | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational | PC [5] | Constraint-based method [5]. | Limited information extraction from data [5]. |

| GES [5] | Score-based method, greedily maximizes graph score [5]. | Limited information extraction from data [5]. | |

| NOTEARS [5] | Continuous optimization with differentiable acyclicity constraint [5]. | Limited information extraction from data [5]. | |

| GRNBoost [5] | Tree-based Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) inference [5]. | High recall on biological evaluation, but with low precision [5]. | |

| Interventional | GIES [5] | Extension of GES for interventional data [5]. | Does not outperform its observational counterpart (GES) [5]. |

| DCDI [5] | Continuous optimization-based for interventional data [5]. | Limited information extraction from data [5]. | |

| Challenge Methods | Mean Difference [5] | Top-performing method from CausalBench challenge [5]. | Best performance on statistical evaluation (e.g., Mean Wasserstein, FOR) [5]. |

| Guanlab [5] | Top-performing method from CausalBench challenge [5]. | Best performance on biological evaluation (e.g., precision, recall) [5]. | |

| Betterboost, SparseRC [5] | Methods from CausalBench challenge [5]. | Perform well on statistical evaluation but not on biological evaluation [5]. |

Performance Trade-offs and Key Insights

The comparative data reveals several critical trends. First, there is a consistent trade-off between precision and recall across most methods; no single algorithm excels at both simultaneously [5]. Second, contrary to theoretical expectations, traditional interventional methods often fail to outperform observational methods, highlighting a significant area for methodological improvement [5]. Finally, community-driven efforts like the CausalBench challenge have spurred the development of new methods, such as Mean Difference and Guanlab, which set a new state-of-the-art, demonstrating the power of rigorous benchmarking in accelerating progress [5].

The relationship between key evaluation metrics can be visualized as a conceptual scatter plot, illustrating the performance landscape and trade-offs.

Conceptual Metric Trade-off: This diagram illustrates the common precision-recall trade-off, with the ideal position being the top-right corner. The placement of methods like Guanlab and GRNBoost reflects their performance profile as identified in benchmark studies [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental workflows underpinning network inference benchmarks rely on several key biological and computational reagents.

Essential Research Reagents for Network Inference Benchmarking

| Item | Function in the Context of Network Inference |

|---|---|

| CRISPRi Knockdown System | Technology used in CausalBench datasets to perform targeted genetic perturbations (gene knockdowns) and generate the interventional data required for causal inference [5]. |

| Single-cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Method for measuring the whole transcriptome (gene expression) of individual cells under both control and perturbed states. This provides the high-dimensional readout for network analysis [5]. |

| Curated Perturbation Datasets (e.g., RPE1, K562) | Large-scale, openly available datasets that serve as the empirical foundation for benchmarks. They include measurements from hundreds of thousands of individual cells and are essential for realistic evaluation [5]. |

| Benchmarking Suite (e.g., CausalBench) | Integrated software suite that provides the data, baseline method implementations, and standardized evaluation metrics necessary for consistent and reproducible comparison of network inference algorithms [5]. |

The field of network inference is moving toward a more mature and rigorous phase, driven by benchmarks grounded in real-world biological data. For researchers in disease data and drug development, success is no longer just about developing a new algorithm, but about demonstrating its value through comprehensive evaluation against defined metrics and state-of-the-art methods. Benchmarks like CausalBench provide the necessary framework for this, offering biologically-motivated metrics and large-scale perturbation data to bridge the gap between theoretical innovation and practical application. The insights from such benchmarks are clear: scalability and the effective use of interventional data are current limitations, while community-driven challenges hold great promise for unlocking the next generation of high-performing methods. By leveraging these tools and understanding the associated metrics and trade-offs, scientists can more reliably reconstruct the causal wiring of diseases, ultimately accelerating the discovery of new therapeutic targets.

A Toolkit for Discovery: Categories of Network Inference Algorithms and Their Applications in Disease Research

In the field of computational biology, accurately inferring networks from complex data is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets. Correlation and regression-based methods form the backbone of many network inference algorithms, enabling researchers to model relationships between biological variables such as genes, proteins, and metabolites. While correlation analysis measures the strength and direction of associations between variables, regression analysis goes a step further by modeling the relationship between dependent and independent variables, allowing for prediction and causal inference [16] [17].

The selection between these methodological approaches carries significant implications for the reliability and interpretability of research findings in drug discovery and development. This guide provides an objective comparison of these foundational techniques, framed within the context of benchmarking network inference algorithms for disease research, to equip scientists with the knowledge needed to select appropriate methods for their specific research questions and data characteristics.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Distinctions

Fundamental Concepts

Correlation is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables, without distinguishing between independent and dependent variables. The most common measure, Pearson correlation coefficient (r), ranges from -1 to +1, where +1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, -1 represents a perfect negative correlation, and 0 indicates no linear relationship [16] [17].

Regression analysis models the relationship between a dependent variable (outcome) and one or more independent variables (predictors). Unlike correlation, regression can predict outcomes and quantify how changes in independent variables affect the dependent variable. The simple linear regression equation is expressed as Y = a + bX + e, where Y is the dependent variable, X is the independent variable, a is the intercept, b is the slope, and e is the error term [17].

Comparative Analysis: Purpose and Application

Table 1: Core Differences Between Correlation and Regression

| Aspect | Correlation | Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Measures strength and direction of relationship [16] | Predicts outcomes and models relationships [16] |

| Variable Treatment | Treats variables equally [16] | Distinguishes independent and dependent variables [16] |

| Output | Single coefficient (r) between -1 and +1 [16] [17] | Mathematical equation (e.g., Y = a + bX) [16] [17] |

| Causation | Does not imply causation [16] [17] | Can suggest causation if properly tested [16] |

| Application Context | Preliminary analysis, identifying associations [16] [17] | Prediction, modeling, understanding impact [16] [17] |

| Data Representation | Single value summarizing relationship [16] | Equation representing the relationship [16] |

Use Cases in Network Inference and Drug Discovery

Correlation-Based Applications

In network inference, correlation methods are widely used for initial exploratory analysis to identify potential relationships between biological entities. In neuroscience research, Pearson correlation coefficients are extensively used to define functional connectivity by measuring BOLD signals between brain regions [18]. Similarly, in gene regulatory network (GRN) inference, methods such as PPCOR and LEAP utilize Pearson's correlation to identify potential regulatory relationships between genes [19].

The appeal of correlation analysis lies in its simplicity and computational efficiency, making it particularly valuable for initial hypothesis generation when dealing with high-dimensional biological data. For example, correlation networks can help identify co-expressed genes that may participate in common biological pathways or processes, providing starting points for more detailed experimental investigations [19].

Regression-Based Applications

Regression methods offer more sophisticated approaches for modeling complex relationships in biological systems. Multiple linear regression enables researchers to simultaneously assess the impact of multiple factors on biological outcomes, such as modeling how various genetic and environmental factors collectively influence disease progression [20].

In computer-aided drug design (CADD), regression methods are fundamental to Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, which predicts compound activity based on structural characteristics. Both linear and nonlinear regression techniques are employed to model the relationship between molecular features and biological activity, facilitating drug discovery and optimization [21].

More advanced regression implementations include regularized regression methods (such as Ridge, LASSO, or elastic nets) that add penalties to parameters as model complexity increases, preventing overfitting—a common challenge when working with high-dimensional omics data [22].

Limitations and Methodological Challenges

Limitations of Correlation Analysis

Despite its widespread use, correlation analysis presents several significant limitations in network inference contexts:

Inability to Capture Nonlinear Relationships: Correlation coefficients, particularly Pearson's r, primarily measure linear relationships. Biological systems frequently exhibit nonlinear dynamics that correlation may fail to detect [18]. For instance, in connectome-based predictive modeling, Pearson correlation struggles to capture the complexity of brain network connections, potentially overlooking critical nonlinear characteristics [18].

No Causation Implication: A fundamental limitation is that correlation does not imply causation. Strong correlation between two variables does not mean that changes in one variable cause changes in the other [16] [17]. This is particularly problematic in drug discovery where understanding causal relationships is essential for identifying valid therapeutic targets.

Sensitivity to Data Variability and Outliers: Correlation lacks comparability across different datasets and is highly sensitive to data variability. Outliers can significantly distort correlation coefficients, potentially leading to inaccurate network inference [18].

Limitations of Regression Analysis

Regression methods, while more powerful than simple correlation, also present important limitations:

Model Assumptions: Regression typically assumes a linear relationship between variables, which may not always reflect biological reality. While nonlinear regression techniques exist, they require more data and computational resources [17] [21].

Overfitting and Underfitting: Regression models are susceptible to overfitting (modeling noise rather than signal) or underfitting (failing to capture underlying patterns), particularly with complex biological data [22]. This is especially challenging in single-cell RNA sequencing data where the number of features (genes) often far exceeds the number of observations (cells) [19] [4].

Data Quality Dependencies: The predictive power of any regression approach is highly dependent on data quality. Regression requires accurate, curated, and relatively complete data to maximize predictability [22]. This presents challenges in biological contexts where data may be noisy, sparse, or contain numerous missing values.

Experimental Benchmarking and Performance Evaluation

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent benchmarking efforts provide empirical data on the performance of various network inference methods. The CausalBench suite, designed for evaluating network inference methods on real-world large-scale single-cell perturbation data, offers insights into the performance of different algorithmic approaches [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods on CausalBench

| Method Category | Example Methods | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | PPCOR, LEAP [19] | Computational efficiency, simplicity | Limited to linear associations, lower precision |

| Observational Causal | PC, GES, NOTEARS [2] | Causal framework, no interventional data required | Poor scalability, limited performance in real-world systems |

| Interventional Causal | GIES, DCDI variants [2] | Leverages perturbation data for causal inference | Computational complexity, limited scalability |

| Challenge Methods | Mean Difference, Guanlab [2] | Superior performance on statistical and biological metrics | Method-specific limitations requiring further investigation |

The benchmarking results reveal several important patterns. Methods using interventional information do not consistently outperform those using only observational data, contrary to what might be theoretically expected [2]. This highlights the significant challenge of effectively utilizing perturbation data in network inference. Additionally, poor scalability of existing methods emerges as a major limitation, with many methods struggling with the dimensionality of real-world biological data [2].

Comprehensive Evaluation Metrics

Relying solely on correlation coefficients for model evaluation presents significant limitations. In connectome-based predictive modeling, Pearson correlation inadequately reflects model errors, particularly in the presence of systematic biases or nonlinear error [18]. To address these limitations, researchers recommend combining multiple evaluation metrics:

Error Metrics: Mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) provide insights into the predictive accuracy of models by capturing the error distribution [18].

Baseline Comparisons: Comparing complex models against simple baselines (e.g., mean value or simple linear regression) helps evaluate the added value of sophisticated approaches [18].

Biological Validation: Beyond statistical measures, biological validation using known pathways or experimental follow-up remains essential for verifying network inferences [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Network Inference Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Datasets | Provides single-cell resolution gene expression data for network inference | CausalBench datasets (RPE1 and K562 cell lines) [2] |

| Perturbation Technologies | Enables causal inference through targeted interventions | CRISPRi for gene knockdowns [2] |

| Benchmark Suites | Standardized framework for method evaluation | CausalBench [2], BEELINE [4] |

| Software Libraries | Programmatic frameworks for implementing methods | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn [22] |

| Prior Network Knowledge | Existing biological networks for validation | Literature-curated reference networks [19] |

Experimental Workflow and Methodological Considerations

Standardized Experimental Protocol

A typical workflow for benchmarking network inference methods involves several key stages:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing: This includes quality control, normalization, and handling of missing values or dropouts, which are particularly prevalent in single-cell data [19] [4].

Feature Selection: Identifying relevant features (e.g., genes, connections) for inclusion in the model. In connectome-based predictive modeling, Pearson correlation is often used with a threshold (e.g., p < 0.01) to remove noisy edges and retain only those with significant correlations [18].

Model Training: Implementing the selected algorithms with appropriate validation strategies such as cross-validation [18] [22].

Performance Evaluation: Assessing methods using multiple metrics from both statistical and biological perspectives [2].

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for benchmarking network inference methods:

Addressing Technical Challenges

Several technical challenges require specific methodological approaches:

Zero-Inflation in Single-Cell Data: The prevalence of false zeros ("dropout") in single-cell RNA sequencing data significantly impacts network inference. Novel approaches like Dropout Augmentation (DA) intentionally add synthetic dropout events during training to improve model robustness against this noise [4].

Scalability Issues: Many network inference methods struggle with the dimensionality of biological data. Methods must be selected or developed with scalability in mind, particularly for large-scale single-cell datasets containing measurements for thousands of genes across hundreds of thousands of cells [2].

Ground Truth Limitations: Evaluating inferred networks is challenging due to the lack of definitive ground truth knowledge in biological systems. Combining biology-driven approximations of ground truth with quantitative statistical evaluations provides a more comprehensive assessment framework [2].

Correlation and regression-based methods offer complementary approaches for network inference in disease research and drug discovery. Correlation provides a valuable tool for initial exploratory analysis and hypothesis generation, while regression enables more sophisticated modeling and prediction capabilities. Both approaches, however, present significant limitations that researchers must acknowledge and address through rigorous experimental design, comprehensive evaluation metrics, and appropriate method selection.

The ongoing development of benchmark suites like CausalBench represents important progress in standardizing the evaluation of network inference methods. Future methodological advances should focus on improving scalability, better utilization of interventional data, and enhanced robustness to the specific challenges of biological data, particularly the noise and sparsity characteristics of single-cell measurements. By understanding the use cases and limitations of correlation and regression-based methods, researchers can make more informed decisions in selecting and implementing network inference approaches most appropriate for their specific research contexts.

This guide objectively compares the performance of various network inference methods evaluated using the CausalBench framework, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers and professionals in disease data research.

Experimental Framework and Key Metrics

CausalBench is a comprehensive benchmark suite designed to evaluate the performance of network inference methods using real-world, large-scale single-cell perturbation data, moving beyond traditional synthetic datasets [5] [23]. Its core objective is to provide a biologically grounded and principled way to track progress in causal network inference for computational biology and drug discovery [5].

The benchmark utilizes two large-scale perturbational single-cell RNA sequencing datasets from specific cell lines: RPE1 and K562 [5]. These datasets contain over 200,000 interventional data points generated by knocking down specific genes using CRISPRi technology, providing both observational (control) and interventional (perturbed) data [5].

Unlike benchmarks with known ground-truth graphs, CausalBench employs a dual evaluation strategy to overcome the challenge of unknown true causal graphs in complex biological systems [5]:

- Biology-driven evaluation: Uses biologically-motivated performance metrics to approximate ground truth.

- Statistical evaluation: Employs quantitative, distribution-based interventional metrics, including:

- Mean Wasserstein distance: Measures the extent to which a method's predicted interactions correspond to strong causal effects.

- False Omission Rate (FOR): Measures the rate at which truly existing causal interactions are missed by a model.

These metrics complement each other, as there is an inherent trade-off between maximizing the mean Wasserstein distance (prioritizing strong effects) and minimizing the FOR (avoiding missing true interactions) [5].

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the core experimental workflow of the CausalBench benchmarking framework.

Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods

CausalBench systematically evaluates a wide range of state-of-the-art causal inference methods, including both established baselines and methods developed during a community challenge [5]. The tables below summarize their performance.

Method Classifications and Key Findings

Table 1: Categories of Network Inference Methods Evaluated in CausalBench

| Category | Description | Representative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Observational Methods | Infer networks using only control (non-perturbed) data. | PC [5], GES [5], NOTEARS (Linear/MLP) [5], Sortnregress [5], GRNBoost2/SCENIC [5] |

| Traditional Interventional Methods | Leverage both observational and perturbation data. | GIES [5], DCDI variants (DCDI-G, DCDI-DSF) [5] |

| Challenge-Driven Interventional Methods | Newer methods developed for the CausalBench challenge. | Mean Difference [5], Guanlab [5], Catran [5], Betterboost [5], SparseRC [5] |

A key finding from CausalBench is that, contrary to theoretical expectations and performance on synthetic benchmarks, methods using interventional information often do not outperform those using only observational data in real-world environments [5] [23]. Furthermore, the scalability of methods was identified as a major limiting factor for performance [5].

Quantitative Performance Results

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Methods on CausalBench Metrics

| Method | Type | Biological Evaluation (F1 Score) | Statistical Evaluation (FOR) | Statistical Evaluation (Mean Wasserstein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference | Interventional (Challenge) | High [5] | Top Performer [5] | Top Performer [5] |

| Guanlab | Interventional (Challenge) | Top Performer [5] | High [5] | High [5] |

| GRNBoost | Observational | High Recall / Low Precision [5] | Low on K562 [5] | Not Specified |

| Betterboost | Interventional (Challenge) | Lower [5] | High [5] | High [5] |

| SparseRC | Interventional (Challenge) | Lower [5] | High [5] | High [5] |

| NOTEARS, PC, GES, GIES | Observational / Interventional | Low / Varying Precision [5] | Lower [5] | Lower [5] |

The results highlight a clear trade-off between precision and recall across most methods [5]. Challenge methods like Mean Difference and Guanlab consistently emerged as top performers, indicating significant advances in scalability and the effective use of interventional data [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Data Curation and Preprocessing

The benchmark is built upon two openly available single-cell CRISPRi perturbation datasets for the RPE1 and K562 cell lines [5]. The data is curated into a standardized format for causal learning, containing thousands of measurements of gene expression in individual cells under both control and perturbed states [5]. The curation process involves quality control, normalization, and formatting to ensure consistency for evaluating different algorithms.

Model Training and Evaluation Protocol

The standard experimental procedure within CausalBench involves the following steps [5]:

- Training: Models are trained on the full dataset, which includes both observational and interventional data points.

- Multiple Runs: Each model is typically trained multiple times (e.g., five runs) with different random seeds to ensure the robustness of the results.

- Inference: The trained models output a predicted gene-gene interaction network.

- Scoring: The predicted network is evaluated using the two complementary evaluation types: the biology-driven approximation and the quantitative statistical metrics (Mean Wasserstein distance and FOR).

Performance Trade-off Analysis

The following diagram visualizes the core performance trade-off identified by CausalBench evaluations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Datasets for Causal Network Inference

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Source / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPE1 & K562 scCRISPRi Dataset | Biological Dataset | Provides large-scale, real-world single-cell gene expression data under genetic perturbations for training and evaluating models. [5] | CausalBench Framework [5] |

| CausalBench Software Suite | Computational Framework | Provides the integrated benchmarking environment, including data loaders, baseline method implementations, and evaluation metrics. [5] | https://github.com/causalbench/causalbench [5] |

| CRISPRi Technology | Experimental Tool | Enables precise knock-down of specific genes to create the interventional data essential for causal discovery. [5] | CausalBench Framework [5] |

| Mean Wasserstein Distance | Evaluation Metric | Quantifies the strength of causal effects captured by a predicted network, favoring methods that identify strong directional links. [5] | CausalBench Framework [5] |

| False Omission Rate (FOR) | Evaluation Metric | Measures a model's tendency to miss true causal interactions, thus evaluating the completeness of the inferred network. [5] | CausalBench Framework [5] |

The study of human health and disease has undergone a profound transformation with the advent of high-throughput technologies, shifting from single-layer analyses to integrative multi-omics approaches. Multi-omics involves the combined application of various "omes" - including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics - to build comprehensive molecular portraits of biological systems [24]. This paradigm recognizes that complex diseases cannot be fully understood by examining any single molecular layer in isolation, as cellular processes emerge from intricate interactions across these different biological levels [25]. The primary strength of multi-omics integration lies in its ability to uncover causal relationships and regulatory networks that remain invisible when examining individual omics layers separately [26].

The relevance of multi-omics approaches is particularly significant in the context of benchmarking network inference algorithms, which aim to reconstruct biological networks from molecular data. Accurate network inference is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets [5]. As noted in recent large-scale evaluations, "accurately mapping biological networks is crucial for understanding complex cellular mechanisms and advancing drug discovery" [5]. However, the performance of these algorithms varies considerably when applied to different types of omics data, necessitating rigorous benchmarking frameworks to guide methodological development and application.

Categories of Omics Technologies and Their Applications

Core Omics Layers

Multi-omics research incorporates several distinct but complementary technologies, each capturing a different aspect of cellular organization and function:

Genomics: The study of an organism's complete set of DNA, including genes and non-coding sequences. Genomics focuses on identifying variations such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs) that may influence disease susceptibility [24]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) represent a primary application of genomics in disease research [25].

Transcriptomics: The global analysis of RNA expression patterns, providing a snapshot of gene activity at a specific time point. Transcriptomics reveals which genes are actively being transcribed and can identify differentially expressed genes associated with disease states [25]. Modern transcriptomics increasingly utilizes single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to resolve cellular heterogeneity within tissues [27].

Proteomics: The large-scale study of proteins, including their expression levels, post-translational modifications, and interactions. Since proteins directly execute most biological functions, proteomics provides crucial functional information that cannot be inferred from genomic or transcriptomic data alone [25]. Mass spectrometry-based methods are widely used for proteomic profiling [25].

Epigenomics: The analysis of chemical modifications to DNA and histone proteins that regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. Epigenomic markers include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility, which collectively influence how genes are packaged and accessed by the transcriptional machinery [24].

Metabolomics: The comprehensive study of small-molecule metabolites that represent the end products of cellular processes. Metabolites provide a direct readout of cellular activity and physiological status, making metabolomics particularly valuable for understanding functional changes in disease [24]. Related fields include lipidomics (study of lipids) and glycomics (study of carbohydrates) [24].

Emerging Omics Technologies

Recent technological advances have spawned several specialized omics fields that enhance spatial and single-cell resolution:

Single-cell multi-omics: Technologies that simultaneously measure multiple molecular layers (e.g., genome, epigenome, transcriptome) from individual cells, enabling the study of cellular heterogeneity and lineage relationships [25].

Spatial omics: Methods that preserve spatial information about molecular distributions within tissues, providing crucial context for understanding cellular interactions and tissue organization [25]. Spatial transcriptomics has been particularly valuable for resolving spatially organized immune-malignant cell networks in cancers such as colorectal cancer [25].

Benchmarking Network Inference Algorithms: The CausalBench Framework

The Challenge of Network Inference Evaluation

A fundamental challenge in evaluating network inference methods has been the absence of reliable ground-truth data from real biological systems. Traditional evaluations conducted on synthetic datasets do not reflect performance in real-world environments, creating a significant gap between theoretical innovation and practical application [5]. As noted by developers of the CausalBench benchmark suite, "establishing a causal ground truth for evaluating and comparing graphical network inference methods is difficult" in biological contexts characterized by enormous complexity [5].

To address this challenge, researchers have developed CausalBench, a comprehensive benchmark suite specifically designed for evaluating network inference methods using real-world, large-scale single-cell perturbation data [5]. Unlike synthetic benchmarks, CausalBench utilizes data from genetic perturbation experiments employing CRISPRi technology to knock down specific genes in cell lines, generating over 200,000 interventional datapoints that provide a more realistic foundation for algorithm evaluation [5].

Performance Metrics and Evaluation Methodology

CausalBench employs multiple complementary evaluation strategies to assess algorithm performance:

Biology-driven evaluation: Uses biologically-motivated performance metrics that approximate ground truth through known biological relationships [5].

Statistical evaluation: Leverages distribution-based interventional measures, including mean Wasserstein distance and false omission rate (FOR), which are inherently causal as they compare control and treated cells [5].

The benchmark systematically evaluates both observational methods (which use only unperturbed data) and interventional methods (which incorporate perturbation data). This distinction is crucial because, contrary to theoretical expectations, methods using interventional information have not consistently outperformed those using only observational data in real-world applications [5].

Comparative Performance of Network Inference Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods on CausalBench

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Strengths | Performance Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Methods | PC, GES, NOTEARS, GRNBoost | Established methodology, No perturbation data required | Limited accuracy in inferring causal direction |

| Interventional Methods | GIES, DCDI variants | Theoretical advantage from perturbation data | Poor scalability limits real-world performance |

| Challenge Methods | Mean Difference, Guanlab, Catran | Better utilization of interventional data | Varying performance across evaluation metrics |

Recent benchmarking using CausalBench revealed several important insights. First, scalability emerged as a critical factor limiting performance, with many methods struggling to handle the complexity of real-world datasets [5]. Second, a clear trade-off between precision and recall was observed across methods, necessitating context-dependent algorithm selection [5]. Notably, only a few methods, including Mean Difference and Guanlab, demonstrated strong performance across both biological and statistical evaluations [5].

Multi-Omics in Disease Research: Key Applications and Findings

Predictive Performance Across Omics Layers

Large-scale comparative studies have quantified the relative predictive value of different omics layers for complex diseases. A comprehensive analysis of UK Biobank data encompassing 90 million genetic variants, 1,453 proteins, and 325 metabolites from 500,000 individuals revealed striking differences in predictive performance [28].

Table 2: Predictive Performance of Different Omics Layers for Complex Diseases

| Omics Layer | Median AUC for Incidence | Median AUC for Prevalence | Optimal Number of Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | 0.57 (0.53-0.67) | 0.60 (0.49-0.70) | N/A (PRS-based) |

| Proteomics | 0.79 (0.65-0.86) | 0.84 (0.70-0.91) | 5 proteins |

| Metabolomics | 0.70 (0.62-0.80) | 0.86 (0.65-0.90) | 5 metabolites |

This systematic comparison demonstrated that proteins consistently outperformed other molecular types for both predicting incident cases and diagnosing prevalent disease [28]. Remarkably, just five proteins sufficed to achieve areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs) of 0.8 or more for most diseases, representing substantial dimensionality reduction from the thousands of molecules typically involved in complex diseases [28].

Disease-Specific Applications

Multi-omics approaches have demonstrated particular utility across various disease domains:

Cancer Research: Integration of single-cell transcriptomics and spatial transcriptomics has resolved spatially organized immune-malignant cell networks in human colorectal cancer, providing insights into tumor microenvironment organization [25].

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Multi-omics has helped unravel the complex mechanisms underlying Alzheimer's disease, where single-omics approaches could only identify correlations rather than causal relationships [25].

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases: Proteomic analyses have identified specific protein biomarkers for atherosclerotic vascular disease, including matrix metalloproteinase 12 (MMP12), TNF Receptor Superfamily Member 10b (TNFRSF10B), and Hepatitis A Virus Cellular Receptor 1 (HAVCR1), consistent with known roles of inflammation and matrix degradation in atherogenesis [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Omics Data Generation Workflow

Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow

CausalBench Evaluation Protocol

The CausalBench framework implements a standardized protocol for benchmarking network inference methods:

Data Preparation: Utilizes two large-scale perturbation datasets from RPE1 and K562 cell lines containing thousands of measurements of gene expression in individual cells under both control and perturbed conditions [5].

Method Implementation: Includes a representative set of state-of-the-art methods spanning different algorithmic approaches:

- Constraint-based methods (PC)

- Score-based methods (GES, GIES)

- Continuous optimization-based methods (NOTEARS, DCDI)

- Tree-based methods (GRNBoost)

- Challenge methods (Mean Difference, Guanlab, Catran) [5]

Evaluation Metrics: Computes both biology-driven approximations of ground truth and quantitative statistical evaluations, including mean Wasserstein distance and false omission rate (FOR) [5].

Validation: Conducts multiple runs with different random seeds to ensure robustness of findings [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Laboratory Reagents for Multi-Omics Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Perturbation Systems | CRISPRi | Targeted gene knockdown for causal network inference [5] |

| Single-Cell Isolation Kits | 10x Genomics kits | Single-cell transcriptomics and multi-omics profiling |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | TMT/SILAC labels | Quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics [25] |

| Epigenomic Profiling Kits | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq kits | Mapping chromatin accessibility and histone modifications [24] |

| Metabolomic Extraction Kits | Methanol:chloroform kits | Comprehensive metabolite extraction for LC-MS analysis |

Computational Tools and Databases

The multi-omics research ecosystem includes numerous specialized computational tools and databases:

Data Integration Tools: Multiple methods have been developed for integrating diverse omics datasets, including correlation-based, network-based, and machine learning approaches [25]. Particularly promising are machine learning and deep learning methods for multi-omics data integration [25].

Benchmarking Suites: CausalBench provides an open-source framework for evaluating network inference methods on real-world interventional data [5].

Public Data Resources: The UK Biobank offers extensive phenotypic and multi-omics data from 500,000 individuals, enabling large-scale comparative studies [28]. The Multi-Omics for Health and Disease Consortium (MOHD) is generating standardized multi-dimensional datasets for broader research use [29].

Signaling Pathways and Biological Networks Revealed by Multi-Omics

Inflammatory Response Networks